Abstract

Background

Social media with real-time content and a wide-reaching user network opens up more possibilities for palliative and end-of-life care (PEoLC) researchers who have begun to embrace it as a complementary research tool. This review aims to identify the uses of social media in PEoLC studies and to examine the ethical considerations and data collection approaches raised by this research approach.

Methods

Nine online databases were searched for PEoLC research using social media published before December 2022. Thematic analysis and narrative synthesis approach were used to categorise social media applications.

Results

21 studies were included. 16 studies used social media to conduct secondary analysis and five studies used social media as a platform for information sharing. Ethical considerations relevant to social media studies varied while 15 studies discussed ethical considerations, only 6 studies obtained ethical approval and 5 studies confirmed participant consent. Among studies that used social media data, most of them manually collected social media data, and other studies relied on Twitter application programming interface or third-party analytical tools. A total of 1 520 329 posts, 325 videos and 33 articles related to PEoLC from 2008 to 2022 were collected and analysed.

Conclusions

Social media has emerged as a promising complementary research tool with demonstrated feasibility in various applications. However, we identified the absence of standardised ethical handling and data collection approaches which pose an ongoing challenge. We provided practical recommendations to bridge these pressing gaps for researchers wishing to use social media in future PEoLC-related studies.

Keywords: Ethics, Terminal care, Education and training, Communication, Supportive care

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN

Social media is widely used in healthcare research and most recently during COVID-19. Its uses in healthcare research have been summarised and criticised. Palliative and end-of-life care researchers have gradually applied social media in their research. However, concerns were raised around ethical issues (eg, privacy and anonymity) and data quality when using social media as a research tool. It is necessary to systematically review its uses in this research field and examine its ethical handling and data collection to inform future researchers.

WHAT ARE THE NEW FINDINGS

This review identified the increasing use of social media data to conduct secondary analysis for palliative and end-of-life care research. However, we identified inconsistent consideration of ethical issues relevant to its use and non-standardised approaches to data collection. This highlighted concerns regarding the ethical principles associated with this method of data collection and analysis as well as its quality.

WHAT IS THEIR SIGNIFICANCE

This review highlighted social media’s value in contributing to palliative and end-of-life care-related studies both as a means of data collection and promoting research. Based on our findings, we developed practical recommendations on the use of social medial research in palliative and end-of-life care studies, including flexible ethical review criteria, ethical risk mitigation strategies, data validation and non-English platform research. Our pragmatic recommendations serve as a reference for future researchers to help them conduct more robust and rigorous palliative social media research.

Introduction

Social media is defined as a collection of internet-based applications to facilitate the creation and exchange of user-generated content.1 A classification scheme has been developed to delineate the different types of social media,1 which includes collaborative projects, for example, Wiki; blogs or microblogs, for example, Twitter; content communities, for example, YouTube; social networking sites that include Facebook; and virtual worlds, for example, Second Life. Globally, the number of social media users has increased dramatically since its inception to approximately 4.74 billion in January 2022.2 This represents 58.4% of the world’s population.2 The healthcare field has embraced social media as a useful tool to access and share information. In 2018, 67% of American healthcare information seekers reported accessing information on social media.3 Social media has also increasingly been used in healthcare research to provide health information, answer health questions, facilitate health dialogue, collect patient data, reduce stigma, and provide online education and consultations.4

Palliative and end-of-life care is an essential component of a healthcare system.5 The increasing engagement in social media of palliative and end-of-life care stakeholders creates a ready platform for its application in palliative and end-of-life care research.6 Eng et al’s study7 identified that among 371 cancer survivors, 74% used the internet and 39% specifically used social media for accessing cancer care information. Other studies have observed that social media is frequently used by patients with cancer to connect with peers and develop stronger bonds with family members.8 In the 2018 National Cancer Institute’s Health Information National Trend survey, respondents ranked online sources, including the internet and social media, as their second choice for seeking palliative care knowledge, after that from healthcare providers.9

A growing body of literature has used social media in palliative and end-of-life care research.10–13 A recent study showed that social media platforms provided a time-efficient and cost-effective method for recruiting paediatric oncology patients for palliative care research.10 In addition, social media platforms have been increasingly used to conduct secondary data analysis to understand barriers to patients accessing palliative care,11 evaluate educational online resources for the public12 and examine determinants of social behaviours and beliefs towards palliative and end-of-life care.13 Advances in natural language processing technologies have enabled researchers to extract useful information from unstructured social media data such as demographic features, views and emotional sentiment of participants which provide valuable insights.13–15

Despite promising benefits, when used as a tool for research, social media is open to criticism. While there is an increasing number of studies that have focused on how to conduct social media research, few studies have examined what constitutes high-quality and ethically responsible social media research. Roland et al 16 and Teague et al 17 attempted to develop guidelines for social media studies, however, they only focused on specific domains, for example, mental health and emergency care. Kaushal et al 18 are currently attempting to construct a more general guideline, but it is still ongoing. Standardised guidelines for social media research are therefore still scarce. Despite this, common concerns have been identified and included in existing social media research guidelines, for example, ethical issues and data quality within the healthcare domain.17 19–21 Although standardised criteria are currently absent, it is suggested that healthcare researchers should adopt a cautious approach to ethical issues and ensure data accuracy and reliability when using social media.19–21 Therefore, there is a clear imperative to review and examine these two centrals concerns when conducting palliative and end-life care studies using social media.

It has been claimed that the introduction of social media to palliative and end-of-life care research presents ethical challenges to researchers that include privacy, anonymity and content ownership.6 When it comes to the context of palliative and end-of-life care, ethical considerations may be amplified due to the potential vulnerability of participants22 23 and the personal and sensitive information shared on social media. This has potential legal implications and ramifications for General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), a European Union regulation on information privacy in the European Union and the European Economic Area. An ethical guidance20 to inform the use of potentially sensitive social media data suggests researchers must either (a) paraphrase all data which is republished in research outputs; (b) seek informed consent from each person or (c) consider using a more traditional research approach. However, the extent to which ethical considerations have been addressed in existing palliative care research remains ambiguous.

Furthermore, if we are to develop a robust evidence base to inform the delivery of palliative and end-of-life care, high-quality data are critical.24 However, the quality of social media data has been criticised because of apparent inaccuracies and biases.21 Consequently, a focus on data collection and verification specific to social media in palliative and end-of-life care research is essential. A complete social media data collection and verification should contain three steps: develop, apply and validate.25 This systematic review, therefore, aimed to (1) identify and appraise different applications of social media in palliative and end-of-life care studies, (2) examine the ethical considerations when using this research approach, (3) examine data collection and verification approaches when using this research approach and (4) make recommendations for researchers who wish to integrate social media in their future research.

Methods

Study design

This systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses 2020 guidelines.26 The study protocol was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD42021262026).27

Search strategy

A two-stage search strategy was applied including a preliminary search to identify search terms and a full search to identify related literature. First, a preliminary search was conducted to explore search terms related to the review questions. The selection of search terms was informed by key terms and associated controlled terms used in relevant palliative and end-of-life care28–30 or social media review papers.31–34 Palliative care research experts were also consulted to further identify appropriate search terms. The final search terms are presented in table 1.

Table 1.

Search terms

| Concept | Search terms |

| Social media | “social media” OR “social web” OR “social network” OR “web 2.0” OR “web2” OR “web-based |

| “Twitter” OR “tweet*” OR “YouTube” OR “LinkedIn” OR “Instagram” OR “Reddit” OR “Weibo” OR “WeChat” OR “online forum*” OR “online community” OR “Pinterest” OR “Tumblr” OR “TikTok” OR “PatientsLikeMe” OR “blog” | |

| Palliative and end-of-life care | “palliative*” OR “hospice” OR “end of life” OR “EoL*” OR “PEoL*” OR “terminal care” OR “terminal ill*” OR “advance care” OR “Marie Curie nurse” OR “Macmillan nurse” OR “comfort care” OR “supportive care” OR “bereavement care” OR “respite care” OR “pain management” OR “pain control” OR “symptom management” |

In the second stage, a full search was conducted to identify related papers among seven health-related electronic databases: Medline, Embase, PsycINFO, Global Health, Health Management Information Consortium, Web of Science (Core Collection), Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) and two grey literature databases: OpenGrey and CareSearch. The detailed search strategy for each database was listed in online supplemental file 1. The search was initiated on 9 June 2020, with the most recent update conducted on 30 December 2022.

spcare-2023-004579supp001.pdf (112.2KB, pdf)

Eligibility criteria

Palliative and end-of-life care research can broadly be defined as studies that attempt to investigate the physical, psychosocial, spiritual and existential needs of patients living with a life-threatening illness and their families, and the evaluation of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of interventions, across all settings, to address specific patient-centred concerns and maximise the quality of life for these individuals and their families.35 Social media was defined as platforms encompassing collaborative projects, blogs or microblogs, content communities, social networking sites, and virtual worlds according to Kaplan and Haenlein’s classification scheme.1 Studies meeting the following inclusion criteria were included: (1) peer-reviewed journal articles with a focus on ‘palliative and end-of-life care research’ and ‘social media’; (2) where methodology and results were provided and (3) where social media was used to obtain at least one part of the results. Since our review aimed to have a comprehensive and up-to-date understanding of social media applications in palliative and end-of-life care research, there were no restrictions on population, language, study design and publication year to ensure the comprehensiveness of the review. Literature reviews, conference abstracts and letters were eventually excluded since they provided limited information about ethical and methodological issues. This is deviated from the original protocol because we found that during the course of the review, researchers have major concerns about ethical issues and data quality when using social media.

Data selection

Papers from different databases were merged and imported into the EndNote V.X9 to facilitate the identification of duplicates and to screen publications. Two reviewers (YW and EC) independently applied inclusion and exclusion criteria to screen titles and abstracts of all papers and then the full text of the remaining papers. Discrepancies were resolved by a third reviewer (WG) through discussion until a consensus was reached.

Quality assessment

Since we included qualitative, quantitative and mixed-method studies in this review we have adopted the QualSyst tool36 to evaluate the quality of the included studies. This tool is a good fit when evaluating research papers encompassing a variety of different research approaches.37 Furthermore, it has been used in previous systematic reviews examining emerging research tools.38 39 For assessing the quality of qualitative studies, 10 standard criteria (research question, study design, context, theoretical framework, sampling strategy, data collection method, data analysis, verification procedure, conclusion and reflexivity of the account) were scored; while for quantitative studies, 14 criteria (research question, study design, method of subject selection, subject characteristics, outcome measures, sample size, analytical methods, estimate of variance, confounding, results, conclusions and, in cases of intervention studies, to the allocation and blinding) were scrutinised. For mixed-method studies, we applied QualSyst tools to their qualitative and quantitative components, respectively, and then calculated the mean score. The quality score does not state anything about the quality of social media uses in included studies since social media research has its own checklist (although not standardised yet), but only indicates the extent to which the design, conduct and analyses attempted to minimise errors and biases. Based on previous studies using QualSyst,40 a summary score was used to assess quality where scores of >80% were judged as ‘strong’, 71%–80% as ‘good’, 51%–70% as ‘adequate’ and <51% as ‘limited’. Two reviewers (YW and EC) performed the quality assessment independently. Any discrepancy was resolved by a third reviewer (JK) through discussion until a consensus was reached.

Data extraction

Data from studies that met the inclusion criteria were extracted to an Excel spreadsheet. Information extracted included basic information (title, authors, publication year, publication type, country) and information related to our review questions (study design, study objectives, social media platform, main application, ethical considerations). To further characterise data collection approaches, specified metrics were extracted from empirical studies using social media data including data extraction method, searching keywords, start and end date, and number of posts/videos collected. YW performed the data extraction independently.

Data analysis and data synthesis

We adopted thematic and narrative synthesis methods to categorise social media applications.41 This comprised three stages: ‘line-by-line’ coding, developing descriptive themes by grouping the coded results into a hierarchical tree structure and generating analytical themes by answering review questions.41 Analytical themes represent a stage of interpretation from the review question’s perspective and reviewers have to go beyond the original content and generate reasonable and logical hypotheses.41 In our review, social media applications were categorised according to this process and analytical themes were inferred by considering how social media supported palliative and end-of-life care research.

We categorised social media applications under two distinct social media approaches: social media as a secondary data source and social media as a platform for sharing information.42 These two approaches were proposed for scrutinising the use of social media in health research.42 Secondary data refers to social media data that was already available on platforms before a study was conducted and provides a starting point for research or helps support findings.43

We synthesised data collection and verification approaches based on a widely used social media data collection framework,25 where social media data collection approaches are defined as approaches for (1) developing a search filter, (2) applying the search filter to retrieve and collect data and (3) assessing the search filter. A search filter is necessary to obtain relevant data for the research topic when searching on social media platforms, which includes a set of keywords integrated with search rules. Data collection approaches were summarised from these three steps.

Results

Search results and study characteristics

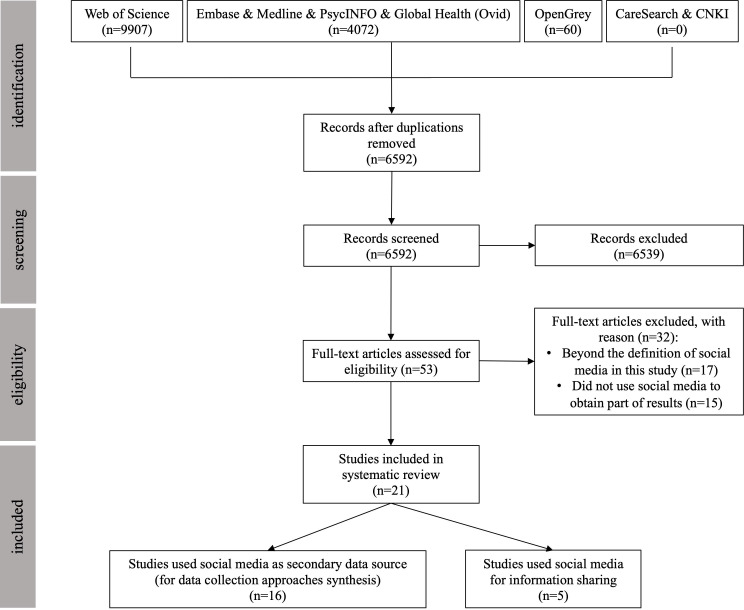

As of 30 December 2022, 6592 papers were screened of which 53 papers went to full screening leading to 21 papers that were included in this review (figure 1). The quality of the articles was appraised as ‘strong’,15 44–48 ‘good’,10 12 49–56 ‘adequate’13 57–59 or ‘limited’.60 Quality scores and other characteristics of the included studies are presented in table 2. Overall, there was an increasing trend over time in the number of published papers using social media for palliative and end-of-life care research. From 2017, the average annual number of publications was higher than in previous years. 76% (n=16) of included studies were from the USA followed by the UK contributing to 14% (n=3) of included studies. The remaining studies were from Australia (n=1) and Bangladesh (n=1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study selection based on the guidelines of PRISMA. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies

| Reference | Study design (quality assessment, %) | Platform | Social media approach | Social media application | Ethical considerations | Data collection | ||

| Data extraction tool | Searching key terms | Number of posts/videos/articles | ||||||

| Salmi et al (2020)44 | Qualitative study (85) | As a secondary data source | To engage stakeholders to understand their experiences or thoughts | ‘Non-Human Subjects Research’ determined by the Institution Review Board. | Symplur | #BTSM, #HPM | 772 tweets | |

| Padmanabhan et al (2021)45 | Cross-sectional study (85) | As a secondary data source | To engage stakeholders to understand their experiences or thoughts and and to investigate surveillance on the frequency, trend and features of public conversation | Exempt from ethical review determined by the Institution Review Board. | Symplur Signals | #palliativeCare | 182 661 tweets | |

| Cutshall et al (2020)57 | Qualitative methods (65) | As a secondary data source | To engage stakeholders to understand their experiences or thoughts | Not Human Subjects Research determined by the institutional review board. | Manually collected | #BTSM | 536 tweets | |

| Taylor and Pagliari (2018)49 | Qualitative study (80) | As a secondary data source | To engage stakeholders to understand their experiences or thoughts | Ethics approval was provided by the Institutional Review Board. Written agreement was sought and obtained. | Manually collected | @GrangerKate | 550 tweets | |

| Claudio et al (2018)50 | Cross-sectional study (75) | YouTube, Facebook and Twitter | As a secondary data source | To explore the quality and features of online resources | Exempt from ethical review determined by the institutional review board. | Manually collected | “palliative care” (YouTube), “#palliativecare”, “#pallcare”, and “#palcare” (Twitter) | 25 tweets, 25 Facebook, 10 videos |

| Mitchell et al (2017)58 | Mix-method study (70) | YouTube | As a secondary data source | To explore the quality and features of online resources | Not reported | Manually collected | ‘Advance Care Directive’ OR ‘ACP’ OR ‘Advance Care Plan’ | 42 videos |

| Nwosu et al (2015)15 | Retrospective analysis (quantitative study) (83) | As a secondary data source | To investigate surveillance on the frequency, trend and features of public conversation | Non-human subjects, therefore ethics committee approval was not deemed to be necessary. | TopsyPro | #hpm #hpmglobal #eolc #Hospice care Liverpool care pathway | 683 500 tweets | |

| Zhao et al (2020)13 | Quantitative study (64) | As a secondary data source | To investigate surveillance on the frequency, trend and features of public conversation | Not reported | Twitter API | “palliative care” and “palliative medicine” etc. | 371 880 tweets | |

| Buis (2008)46 | Qualitative content analysis (90) | Yahoo! | As a secondary data source | To explore the quality and features of online resources | Was approved by a university institutional review board and adhered to guidelines for ethical research. | Manually collected | hospice | 443 posts |

| Singh et al (2021)51 | Qualitative content analysis (75) | As a secondary data source | To engage stakeholders to understand their experiences or thoughts | Ethical approval was obtained from the institutional ethics committee. Consent was waived. | Manually collected | #pallicovid and #COVID-19, palliative care OR COVID-19 OR death OR dying | 33 online articles and blogs | |

| Guidry and Benotsch (2019)52 | Mix-method study (80) | As a secondary data source | To investigate surveillance on the frequency, trend and features of public conversation | Institutional review board approval was not required. | Manually collected | Chronic Pain | 502 pins | |

| Patel et al (2022)53 | Mixed-method study (75) | As a secondary data source | To investigate surveillance on the frequency, trend and features of public conversation | Institutional review board approval was not required. | Twitter API | “DNR”, “DNI”,“advance directives,” “ECMO,” “CPR,” “dialysis,” and “ventilation,” “advance directives” etc. | 202 585 tweets about LSIs and 67 162 tweets about ACP | |

| Easwar et al (2022)54 | Mixed-method study (74) | TikTok | As a secondary data source | To explore the quality and features of online resources | Not reported | Manually collected | ‘palliative.’ | 146 videos |

| Lattimer et al (2022)59 | Mixed-method study (65) | As a secondary data source | To investigate surveillance on the frequency, trend and features of public conversation | Not reported | Twitter API | #nhdd, #advancecareplan, and #goalsofcare, healthcare decision day, advance care plan, goals of care. | 9713 tweets | |

| Liu et al (2019)12 | Review (73) | YouTube | As a secondary data source | To explore the quality and features of online resources | Institutional review board approval was not required. | Manually collected | palliative care | 84 videos |

| Wittenberg-Lyle et al (2014)55 | Review (75) | YouTube | As a secondary data source | To explore the quality and features of online resources | Not reported | Manually collected | pain and cancer; pain and hospice; pain and PC palliative care | 43 videos |

| Levy et al (2019)47 | Experimental study (82) | Pixstori | As an information sharing platform | To deliver intervention | Was approved by the institutional review board. Written consent and media waiver were obtained. | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Taubert et al (2018)48 | Mixed-method design (88) | YouTube, Facebook and Twitter | As an information sharing platform | For promotion, education and training | No ethics approval was required. Consent and agreement were obtained. | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Akard et al (2015)10 | Survey (quantitative study) (79) | As an information sharing platform | To enhance recruitment opportunities | Was approved by the institutional review board. Consent was obtained online. | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable | |

| Biswas et al (2021)61 | Cross-sectional study (75) | Not reported | As an information sharing platform | To enhance recruitment opportunities | Was approved by the ethical review committee. Informed consent was obtained. | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Beringer et al (2017)60 | Qualitative methodology (45) | Self-built platform | As an information sharing platform | For promotion, education and training | Not reported | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable |

API, application programming interface.

The proportion of publications using different social media platforms is presented in table 2. From 2015 to 2022, Twitter was the most commonly used (n=11) social media platform. The second most frequently used platform was YouTube (n=5) followed by Facebook (n=3). The oldest (2008) platform identified was Yahoo! (n=1) and the newest was TikTok (n=1). Picture-sharing platforms such as Pinterest (n=1) were also represented. While most studies made use of popular social media platforms, one study60 made use of its dedicated online community serving older LGBTQ+ individuals regarding end-of-life planning. One paper used more than one platform in their studies.50

Social media applications in palliative and end-of-life care research

Based on the taxonomy,42 we identified three applications using social media as a secondary source of data which included (1) exploring the quality and features of online resources; (2) engaging with stakeholders to understand their experiences and thoughts; (3) investigating surveillance of the frequency, trends and features of public conversations. In addition, we identified three applications using social media as a platform for sharing information which included (1) delivering intervention; (2) enhancing recruitment opportunities and (3) for promotion, education and training. The number of studies in each classification scheme is presented in table 3.

Table 3.

Social media application in palliative and end-of-life care research

| Social media approaches | Application | No of studies |

| As a secondary data source (n=16) | To explore the quality and features of online resources | 612 46 50 54 55 58 |

| To engage stakeholders to understand their experiences or thoughts | 544 45 49 51 57 | |

| To investigate surveillance on the frequency, trend and features of public conversation | 613 15 45 52 53 59 | |

| As a platform for information sharing (n=5) | To deliver intervention | 147 |

| To enhance recruitment opportunities | 210 61 | |

| For promotion, education and training | 248 60 |

Social media as a secondary data source (n=16)

16 studies were characterised as secondary data analysis studies. Specifically, these studies have been categorised into three groups. Six studies12 46 50 54 55 58 explored the quality and features of online resources using social media. Three of them12 55 58 summarised video resources on YouTube and one research study54 explored short-form videos on TikTok. One study50 compared the resources available on YouTube, Facebook and Twitter and identified that YouTube was able to provide valuable insights into examining palliative care resources. Some of these studies12 50 attempted to identify how palliative care was portrayed in social media videos and they found most resources were consistent with the current definition of palliative care. Two studies54 58 attempted to explore the relationship between resource features, for example, author characteristics and content type and public engagement (eg, the number of views, ‘likes’ and ‘forwards’) to inform the future development of online resources. One study46 described the different types of social support in a hospice online community and found emotional support was higher than informational support.

Five studies44 45 49 51 57 used social media to engage stakeholders to understand their experiences or insights about palliative and end-of-life care. One study45 focused on self-identified informal caregivers and summarised their tweets to explore their experiences of palliative care. Most recently, Singh et al 51 explored health professionals’ Twitter articles and blogs to ascertain their views on the role of palliative care during the COVID-19 pandemic. One study49 collected 550 tweets from a single cancer patient to provide a detailed perspective of her end-of-life experiences. Two studies used Twitter chatter data to understand the quality of life needs44 and advance care planning experiences57 of patients living with brain tumours, and the perspectives of their caregivers, healthcare professionals and organisations.

Last, six studies13 15 45 52 53 59 investigated surveillance of public conversation about the frequency, trend and features on social media. These studies traced public discussion on Twitter or Pinterest from 2011 to 2021 on a range of palliative and end-of-life care topics including palliative care,13 15 45 chronic pain,52 life-sustaining interventions53 and advance directives.59 Frequency surveillance,15 45 content analysis,13 45 52 53 59 user demographic feature prediction,13 53 network analysis45 and sentiment analysis15 45 53 were applied in these studies to understand the discussion frequency, popular topics, user’s gender or age, information dissemination network and public sentiment (eg, positive or negative sentiment) towards palliative and end-of-life care social media discussion.

Social media as a platform for information sharing (n=5)

Five studies10 47 48 60 61 were identified as using social media as a platform for information dissemination. The applications of social media as a platform have been categorised into the following three groups. First, one study47 used social media to deliver palliative care intervention. This study47 used social media to deliver an intervention for paediatric palliative caregivers via the ‘Photographs of Meaning Programme’. Specifically, participants were asked to post photo narratives on social media. Second, social media was used to enhance recruitment opportunities in two studies.10 61 Akard et al’s empirical studies tried to validate the cost efficiency of social media in recruitment which used Facebook to recruit paediatric cancer patients.10 Biswas et al 61 recruited clinicians through social media to understand their knowledge about palliative care. Last, two studies48 60 examined the place of social media for promotion, education and training for palliative and end-of-life care. Twitter and YouTube were used in one study48 to raise public awareness of palliative and end-of-life care by disseminating self-made videos to improve communication for do not attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation decision. This study reported more than 100 000 hits over 6 months. Another study60 shared end-of-life information for older LGBTQ+ adults through a self-developed supportive online community. However, the decreasing engagement of this forum was reported, possibly attributed to the lack of security and privacy in the online environment.

Ethical considerations

A total of 15 out of 21 studies discussed ethical considerations associated with the use of social media in palliative and end-of-life care research. Specifically, we identified that when using social media as a platform for information sharing researchers generally considered that ethical approval and participant consent were warranted. All five social media studies10 47 48 56 61 using social media as a platform reported ethical considerations, with four10 47 48 56 obtaining informed consent and three10 47 61 obtaining ethical approval. In contrast, our findings revealed that when using social media as a secondary data source, researchers often perceived that seeking ethical approval and participant consent was sometimes unnecessary. 11 out of 16 studies12 15 44–46 49–53 57 reported their ethical considerations for using social media data. Specifically, eight studies12 15 44 45 50 52 53 57 stated ethical approval was exempt because of the public availability of social media data, and therefore, no consent was obtained. Two studies46 51 obtained ethical approval but the need to obtain consent was waived. One study49 obtained both ethical approval with associated consent from the participant and her family. The results indicated that the distribution of ethical considerations of two social media applications was highly variable (see table 4).

Table 4.

Ethical considerations status among two social media applications

| Ethical considerations | The number of studies using social media as a secondary data source | The number of studies using social media as a platform for information sharing |

| No discussion | 5 | 1 |

| Exempt from ethical approval | 8 | 1 |

| Obtained ethical approval | 3 | 3 |

| Obtained informed consent | 1 | 4 |

| Total | 16 | 5 |

Social media data collection approaches

A total of 16 studies12 13 15 44–46 49–55 57–59 used secondary social media data. Here, we synthesised the data collection approaches of these studies.

When developing a search filter, identified studies used various keywords related to their research topics. Six studies12 13 45 50 51 54 focused on palliative and hospice-care-related topics on social media and used keywords including #PalliativeCare, #hpm, #eolc, #Hospice care, palliative medicine, #pallicovid to retrieve related content. Two studies58 59 retrieved advance-directives-related information by employing keywords for example #living will, #medical directive, #advancecareplan and #goals of care. The other keywords used in developing search filters are listed in table 2.

When applying the search filter to retrieve and collect data we identified three tools among existing studies: official data collection channels (eg, Twitter application programming interface (API)), third-party data collection tools (eg, Symplur Signals and TopsyPro), and manual collection. Three studies13 53 59 used the official data collection channel—Twitter API to collect Twitter data. Twitter API is designed for programmatic access to Twitter’s real-time and historical data. To use Twitter API, academic researchers have to apply for access permission. Three studies15 44 45 used third-party data collection tools like Symplur Signals44 45 and TopsyPro15 to access Twitter data. They are commercial social media analytics platforms to extract data from Twitter. Ten studies12 46 49–52 54 55 57 58 manually downloaded data from social media platforms.

Assessing the search filter is defined as validating the relevance of collected social media data to the research topic. Although the search filter was applied to screen out the collected data it did contain some irrelevant information. For instance, when we used the term ‘comfort care’ as a search term or synonym to retrieve tweets related to palliative and end-of-life care on Twitter we inadvertently identified a tweet describing the ‘Comfort Care’ brand of toilet paper which was irrelevant to our study. Therefore, it was necessary to assess the relevance of the collected data before analysis. A total of 1 520 329 posts, 325 videos and 33 online articles related to palliative and end-of-life care from 2008 to 2022 were collected in secondary analysis studies. Among them, 2056 tweets, 325 videos and 33 online articles, represented in 10 studies,12 46 49–52 54 55 57 58 were included for analysis after manually assessing whether it is related to palliative and end-of-life care or not. One study 13 employed a machine learning algorithm to identify and remove irrelevant tweets from the collected tweets but did not report further assessment for the rest of tweets. The remaining data in another five studies15 44 45 53 59 were included for analysis without reporting data assessment in their studies.

Discussion

This systematic review aimed to identify and examine the use of social media in palliative and end-of-life care research by appraising the ethical and data collection issues associated with its uses and applications. Our review identified an increasing academic interest in using social media as a research tool in palliative and end-of-life care research. Specifically, our review highlighted three applications of social media as a secondary data source in palliative and end-of-life care research which included exploring the quality and features of online resources, engaging stakeholders to understand their experiences or thoughts and investigating surveillance on the frequency, trends and features of public conversation. We also identified that social media has been used as a platform for information sharing in palliative and end-of-life care research specifically to deliver the intervention, enhance recruitment opportunities and for promotion, education and training.

Of note, we identified how ethical issues that were considered and managed in social media studies were inconsistent. Most researchers reported research using social media data to be retrospective so ethical approval was often ignored or waived. However, when researchers attempted to obtain primary data through social media platforms, for example, by recruitment, ethical approval and participant consent were commonly required. The summary of data collection approaches revealed that a wide range of social media content related to palliative and end-of-life care was retrieved and analysed, however, data quality of completeness and accuracy still lacks validation.

The use of social media in palliative and end-of-life care research

Casañas i Comabella and Wanat ’s review in 2015 emphasised the potential of social media in palliative care research recruitment to collect primary data.6 However, our review identified that social media use also extended to secondary data analysis (16 out of 21 included studies) to understand online discussion and resources. Given the data collection difficulties in palliative and end-of-life care research,62 it is not surprising that social media data have often acted as one complementary data resource in palliative care research. Social media data could also be seen as a new vehicle that provides agency for potentially vulnerable palliative care research participants with fragile physical and mental issues22 to share their views on their terms, in their time and when they feel able to do so.

The growing use of social media secondary data in palliative and end-of-life care may also be partly explained by rapid advancements in natural language processing technologies.63 These technologies allow researchers to extract more valuable information from unstructured social media data with higher efficiency. They have enabled palliative and end-of-life care researchers to identify different palliative and end-of-life care stakeholders,45 understand public sentiment,15 extract demographic features13 and conduct large-scale content analysis.14 Additionally, more research tasks can be addressed by using natural language processing techniques. For example, several studies have made use of natural language processing technologies as applied to social media data to examine healthcare performance,64 predict mental health states65 and identify patient-reported symptoms.66 These examples may offer those working in palliative care ways to examine the quality and satisfaction associated with palliative and end-of-life care services performance or identify issues associated with patients’ mental or physical symptoms. However, opportunities also come with challenges and the computer-assisted natural language processing technology poses new concerns about the accuracy and robustness of the results due to the ‘black-box’ analysis process.67

Ethical implications for using social media in palliative and end-of-life care research

Attempts have been made in 2014 to construct ethical guidelines relevant to the use of social media in palliative care research.68 The ethical guidelines suggested (1) Internet discussions should be considered private and consent should be obtained for those who shared in for subsequent research; (2) A text-based analytical approach to social media data is not considered an appropriate method in the palliative research; (3) The use of historical text is problematic and not encouraged.68 Our review identified that in a number of instances, the way social media is currently being employed in palliative care research is not consistent with this guidance. Only 5 out of 2110 47–49 61 studies obtained participants’ consent when using social media. When it comes to using social media historical data, the situation has the potential to become complex; only 1 out of 16 studies49 obtained consent before collecting posts or other types of social media data. Moreover, most qualitative or mixed-methods studies used historical text-based data analysis. This was not to denigrate how social media was being used in palliative and end-of-life care research, but it suggests the field of inquiry has progressed since this guidance was first conceived.68

It is not explicitly stated in Twitter and Facebook’s privacy policies69 70 that access to historical data for research purposes requires additional consent from the users. However, implied consent should not be considered a default solution when it comes to public health research,71 especially for palliative and end-of-life care research.68 General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) declares that the protection of natural persons in relation to the processing of personal data is a fundamental right.72 Social media data collection should be compliant with this regulation since it retrieves large amount of personal data. Some patients may share negative feelings at the end of life on social media, and may not want this to be known by their families or friends.73 Previous studies reviewing patients’ views indicated fears that patients may have when their sensitive, personal health data are used for the secondary purpose of research.74 75 Patients may worry about the confidentiality and anonymity of their personal data if it is used for research, adding more burden to their already fragile psychological condition. Therefore, obtaining consent from participants should be actively encouraged when appropriate. Nevertheless, big data research based on social media makes obtaining consent from every participant manifestly impracticable. Even so, it is necessary to assure public privacy and anonymity in all possible ways. Some possible mitigation strategies including data minimisation (ie, only collecting and storing data necessary to accomplish research objectives) and pseudonymisation have been suggested.76 77 Pseudonymisation is not yet available in the big data studies included in this literature review. General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) states in recital 26 that, ‘The principles of data protection should therefore not apply to anonymous information, namely information which does not relate to an identified or identifiable natural person or to personal data rendered anonymous in such a manner that the data subject is not or no longer identifiable’. Therefore, it is especially important for text-based qualitative or mix-method studies where there is greater potential for processing identifiable information but it may also apply to quantitative studies.

Given our review identified ethical considerations associated with the use of social media varied, we suggest more flexible and proportionate ethical review criteria should be adopted depending on the application scenario. If palliative care researchers want to collect primary data through social media, including using social media to recruit, promote or deliver interventions, then obtaining ethical approval and participant consent must be required. If researchers want to access historical social media data to conduct secondary analysis, implied consent represents a challenge. This is the case where researchers are attempting to understand individual patient end-of-life trajectories or preferences or caregiver experiences where consent for their views is preferable. As a consequence of the evolving nature of social media, it is currently difficult to insist on a single ethical prescription for the application of social media in palliative and end-of-life care research. As the British Psychological Society Ethics Guidelines for Internet-Mediated Research pointed out, ‘Certain ethics principles may be more or less salient in different types of research design, and the procedures researchers put in place should be proportional to the likely risk to participants and researchers’.78

Social media data collection and verification in palliative and end-of-life care research

Data collection and verification play a vital role in enhancing data accuracy and completeness. This is particularly important given the potentially large volume of social media data that can be interrogated since vagaries or idiosyncrasies in data collection can become magnified at scale.79

We identified among our included studies that developing and accessing search filters during the data collection process were sometimes not present or standardised. Specifically, we identified that only some studies (11 out of 16 studies) reported the step of assessing the search filter. This means some studies may not validate the retrieved data before analysis, especially for big data studies.15 45 53 59 It is risky to conduct research using data obtained solely through keywords on social media platforms without additional validation. Due to the complexity of the social media context, the search keywords are likely to retrieve irrelevant information. A commonly employed social media data collection framework25 has incorporated data validation as an essential element. In our review, we also emphatically recommend incorporating data validation into the data collection process in palliative and end-of-life care social media research. Even for big data studies, data validation should be conducted in a sample subset.

In addition, we also observed that when developing the search filter, it may be challenging to include all variants of one concept as search keywords. Sometimes the selected search keywords may be too technical that they are rarely used when describing palliative and end-of-life care by the public. Individuals tend to communicate more informally and colloquially on social media than they do in academic contexts.25 Snowball sampling may be a possible solution to combat the real-time updating of the internet which starts with retrieving a sample of tweets with ‘seed’ keywords and then identifying new keywords until no new keywords are found when repeating this process.13

We found the existing studies focused principally on English platforms with little attention being paid to non-English-speaking countries and regions. Access to palliative care is currently grossly inequitable between high-income and low-income counties.80 Moreover, the provision of palliative and end-of-life care services has distinct characteristics in different regions. Future studies should therefore attempt to use and explore palliative and end-of-life care content on non-English platforms.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first review to conduct a thorough systematic search of the available literature concerning social media uses in palliative and end-of-life care research. However, several limitations must be acknowledged. While we endeavoured to minimise language bias by conducting searches across various databases without imposing language restrictions, it is plausible that some non-English studies may have been inadvertently excluded due to their sole publication in local academic databases. Although we incorporated the Chinese academic database CNKI to encompass Chinese studies, some studies conducted in other non-English languages (eg, Japanese) and using local social media platforms (eg, LINE) may have been overlooked. Despite employing an extensive search strategy encompassing terms associated with social media, some studies that may have employed social media platforms might not have captured using our search terms. Given the rapid evolution of social media, it is challenging to enumerate the names of all social media platforms. A further limitation is our use of the QualSyst tool for quality assessment, which is not tailored for social media research. The absence of dedicated quality assessment tools for social media research highlights the need for future development in this field.

Conclusion

Social media with real-time user-generated content and active user interaction opens up more possibilities for healthcare research. Researchers in palliative and end-of-life care have begun to explore the use of social media as an effective research tool to increase public knowledge and improve patients’ and caregivers’ quality of life. Our review identified an increasing interest in this field and summarised six applications of social media in palliative and end-of-life care research. To inform palliative and end-of-life care researchers who want to engage social media in their research, we also noticed and synthesised ethical considerations and data collection approaches of social media research. We identified inconsistent ethical handling and non-standardised data collection approaches among existing studies indicating potential risks in ethics and data quality. We have developed evidence-based recommendations to ensure the best possible ethical and data quality assurance of palliative social media research, including flexible ethical review criteria, ethical risk mitigation strategies, data validation and non-English platform research. Overall, this is a promising and fast-growing field, but continued efforts from the cross-discipline field (computer science, palliative care, media and communication) are needed to make further standardisation in terms of ethics and data quality.

Acknowledgments

YW is funded by the Chinese Scholarship Council (CSC). VC is supported by EPSRC-funded King’s Health Partners Digital Health Hub (EP/X030628/1).

Footnotes

Contributors: YW conducted search, screen, quality assessment, data extraction and wrote the manuscript.

VC involved in thematic and narrative synthesis and revised the manuscript. JK contributed to the conceptualisation, involved in thematic and narrative synthesis and revised the manuscript. EC conducted screen, quality assessment and revised the manuscript. WG contributed to the conceptualisation, conducted screen and revised the manuscript. YZ involved in thematic and narrative synthesis and provided insights into the contextualisation of the study findings. YW is responsible for the overall content as the guarantor.

Funding: YW is funded by the Chinese Scholarship Council (CSC). VC is supported by EPSRC-funded King’s Health Partners Digital Health Hub (EP/X030628/1).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1. Kaplan AM, Haenlein M. Users of the world, unite! the challenges and opportunities of social media. Business Horizons 2010;53:59–68. 10.1016/j.bushor.2009.09.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tankovska HS. Social media - Statistics & Facts: Statista, 2022. Available: https://www.statista.com/topics/1164/social-networks [Accessed 4 Jun 2023].

- 3. Shandwick W, Research K. The Great American Search for Healthcare Information, 2018. Available: https://cms.webershandwick.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Healthcare-Info-Search-Report.pdf [Accessed 2 Dec 2023].

- 4. Moorhead SA, Hazlett DE, Harrison L, et al. A new dimension of health care: systematic review of the uses, benefits, and limitations of social media for health communication. J Med Internet Res 2013;15:e85. 10.2196/jmir.1933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Radbruch L, De Lima L, Knaul F, et al. Redefining palliative care —a new consensus-based definition. J Pain Symptom Manage 2020;60:754–64. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Casañas i Comabella C, Wanat M. Using social media in supportive and palliative care research. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2015;5:138–45. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2014-000708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Eng L, Bender J, Hueniken K, et al. Age differences in patterns and confidence of using Internet and social media for cancer-care among cancer survivors. J Geriatr Oncol 2020;11:1011–9. 10.1016/j.jgo.2020.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Braun LA, Zomorodbakhsch B, Keinki C, et al. Information needs, communication and usage of social media by cancer patients and their relatives. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2019;145:1865–75. 10.1007/s00432-019-02929-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Huo J, Hong Y-R, Grewal R, et al. Knowledge of palliative care among American adults: 2018 health information national trends survey. J Pain Symptom Manage 2019;58:39–47. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Akard TF, Wray S, Gilmer MJ. Facebook ads recruit parents of children with cancer for an online survey of web-based research preferences. Cancer Nurs 2015;38:155–61. 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hudson S, Bailey C, Hewison A. A Twitter exploration of the barriers and Enablers to palliative care for people with COPD. Palliat Med 2016;30:4. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Liu M, Cardenas V, Zhu Y, et al. Youtube videos as a source of palliative care education: a review. J Palliat Med 2019;22:1568–73. 10.1089/jpm.2019.0047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhao Y, Zhang H, Huo J, et al. Mining Twitter to assess the determinants of health behavior towards palliative care in the United States. Health Informatics 2020. 10.1101/2020.03.26.20038372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wang Y, Chukwusa E, Koffman J, et al. Public opinions about palliative and end-of-life care during the COVID-19 pandemic: Twitter-based content analysis. JMIR Form Res 2023;7:e44774. 10.2196/44774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nwosu AC, Debattista M, Rooney C, et al. Social media and palliative medicine: a retrospective 2-year analysis of global Twitter data to evaluate the use of technology to communicate about issues at the end of life. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2015;5:207–12. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2014-000701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Roland D, Spurr J, Cabrera D. Initial standardized framework for reporting social media Analytics in emergency care research. West J Emerg Med 2018;19:701–6. 10.5811/westjem.2018.3.36489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Teague SJ, Shatte ABR, Weller E, et al. Methods and applications of social media monitoring of mental health during disasters: Scoping review. JMIR Ment Health 2022;9:e33058. 10.2196/33058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kaushal A, Bravo C, Duffy S, et al. Developing reporting guidelines for social media research (RESOME) by using a modified Delphi method: protocol for guideline development. JMIR Res Protoc 2022;11:e31739. 10.2196/31739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Salganik MJ. Bit by Bit: Social Research in the Digital Age. Princeton University Press, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Townsend L, Wallace C. Social media research: a guide to ethics. University of Aberdeen 2016;1:16. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stieglitz S, Mirbabaie M, Ross B, et al. Social media Analytics–challenges in topic discovery, data collection, and data preparation. J Inf Manag 2018;39:156–68. 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2017.12.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Koffman J, Morgan M, Edmonds P, et al. Vulnerability in palliative care research: findings from a qualitative study of black Caribbean and white British patients with advanced cancer. J Med Ethics 2009;35:440–4. 10.1136/jme.2008.027839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Evans CJ, Yorganci E, Lewis P, et al. Processes of consent in research for adults with impaired mental capacity nearing the end of life: systematic review and transparent expert consultation (Morecare_Capacity statement). BMC Med 2020;18:221:221. 10.1186/s12916-020-01654-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kamal AH, Bausewein C, Casarett DJ, et al. Standards, guidelines, and quality measures for successful specialty palliative care integration into oncology: Current approaches and future directions. J Clin Oncol 2020;38:987–94. 10.1200/JCO.18.02440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kim Y, Huang J, Emery S. Garbage in, garbage out: data collection, quality assessment and reporting standards for social media data use in health research, Infodemiology and Digital disease detection. J Med Internet Res 2016;18:e41. 10.2196/jmir.4738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg 2021;88:105906. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang Y, Gao W, Chukwusa E. Use of social media for palliative and end-of-life care (Peolc) research: a systematic review. PROSPERO; 2021. Available: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42021262026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Abu-Odah H, Molassiotis A, Liu JYW. Global palliative care research (2002-2020): Bibliometric review and mapping analysis. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2022;12:376–87. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2021-002982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. De Roo ML, Leemans K, Claessen SJJ, et al. Quality indicators for palliative care: update of a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage 2013;46:556–72. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Smith S, Brick A, O’Hara S, et al. Evidence on the cost and cost-effectiveness of palliative care: a literature review. Palliat Med 2014;28:130–50. 10.1177/0269216313493466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bardus M, El Rassi R, Chahrour M, et al. The use of social media to increase the impact of health research: systematic review. J Med Internet Res 2020;22:e15607. 10.2196/15607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Robinson J, Cox G, Bailey E, et al. Social media and suicide prevention: a systematic review. Early Interv Psychiatry 2016;10:103–21. 10.1111/eip.12229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Smailhodzic E, Hooijsma W, Boonstra A, et al. Social media use in Healthcare: A systematic review of effects on patients and on their relationship with Healthcare professionals. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16:442:442. 10.1186/s12913-016-1691-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cheston CC, Flickinger TE, Chisolm MS. Social media use in medical education: a systematic review. Acad Med 2013;88:893–901. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31828ffc23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sepúlveda C, Marlin A, Yoshida T, et al. Palliative care: the world health organization’s global perspective. J Pain Symptom Manage 2002;24:91–6. 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00440-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kmet LM, Cook LS, Lee RC. Standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research papers from a variety of fields. 2004.

- 37. Harrison JK, Reid J, Quinn TJ, et al. Using quality assessment tools to critically appraise ageing research: a guide for Clinicians. Age Ageing 2017;46:359–65. 10.1093/ageing/afw223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Scherrens A-L, Beernaert K, Robijn L, et al. The use of behavioural theories in end-of-life care research: a systematic review. Palliat Med 2018;32:1055–77. 10.1177/0269216318758212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Labarrière F, Thomas E, Calistri L, et al. Machine learning approaches for activity recognition and/or activity prediction in locomotion Assistive devices - a systematic review. Sensors 2020;20:21:6345. 10.3390/s20216345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wong WCW, Cheung CSK, Hart GJ. Development of a quality assessment tool for systematic reviews of observational studies (QATSO) of HIV prevalence in men having sex with men and associated risk Behaviours. Emerg Themes Epidemiol 2008;5:1–4:23. 10.1186/1742-7622-5-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008;8:1–10:45. 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sinnenberg L, Buttenheim AM, Padrez K, et al. Twitter as a tool for health research: a systematic review. Am J Public Health 2017;107:e1–8. 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. van de Sandt S, Dallmeier-Tiessen S, Lavasa A, et al. The definition of Reuse. Data Sci J 2019;18:1–19. 10.5334/dsj-2019-022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Salmi L, Lum HD, Hayden A, et al. Stakeholder engagement in research on quality of life and palliative care for brain tumors: a qualitative analysis of# BTSM and# HPM Tweet chats. Neurooncol Pract 2020;7:676–84. 10.1093/nop/npaa043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Padmanabhan DL, Ayyaswami V, Prabhu AV, et al. The# Palliativecare conversation on Twitter: an analysis of trends, content, and Caregiver perspectives. J Pain Symptom Manage 2021;61:495–503. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.08.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Buis LR. Emotional and informational support messages in an online Hospice support community. CIN 2008;26:358–67. 10.1097/01.NCN.0000336461.94939.97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Levy K, Grant PC, Depner RM, et al. The photographs of meaning program for pediatric palliative Caregivers: feasibility of a novel meaning-making intervention. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2019;36:557–63. 10.1177/1049909118824560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Taubert M, Norris J, Edwards S, et al. Talk CPR-a technology project to improve communication in do not attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation decisions in palliative illness. BMC Palliat Care 2018;17:118:118. 10.1186/s12904-018-0370-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Taylor J, Pagliari C. Deathbedlive: the end-of-life trajectory, reflected in a cancer patient’s Tweets. BMC Palliat Care 2018;17:17:17. 10.1186/s12904-018-0273-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Claudio CH, Dizon ZB, October TW. Evaluating palliative care resources available to the public using the Internet and social media. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2018;35:1174–80. 10.1177/1049909118763800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Singh GK, Rego J, Chambers S, et al. Health professionals’ perspectives of the role of palliative care during COVID-19: content analysis of articles and Blogs posted on Twitter. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2022;39:487–93. 10.1177/10499091211024202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Guidry JPD, Benotsch EG. Pinning to cope: using Pinterest for chronic pain management. Health Educ Behav 2019;46:700–9. 10.1177/1090198118824399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Patel VR, Gereta S, Blanton CJ, et al. Perceptions of life support and advance care planning during the COVID-19 pandemic: a global study of Twitter users. Chest 2022;161:1609–19. 10.1016/j.chest.2022.01.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Easwar S, Alonzi S, Hirsch J, et al. Palliative care Tiktok: describing the landscape and explaining social media engagement. J Palliat Med 2023;26:360–5. 10.1089/jpm.2022.0250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wittenberg-Lyles E, Parker Oliver D, Demiris G, et al. Youtube as a tool for pain management with informal Caregivers of cancer patients: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014;48:1200–10. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.02.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Biswas J, Banik PC, Ahmad N. Physicians' knowledge about palliative care in Bangladesh: A cross-sectional study using Digital social media platforms. PLoS One 2021;16:e0256927. 10.1371/journal.pone.0256927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Cutshall NR, Kwan BM, Salmi L, et al. It makes people uneasy, but it’s necessary.# BTSM”: using Twitter to explore advance care planning among brain tumor Stakeholders. J Palliat Med 2020;23:121–4. 10.1089/jpm.2019.0077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Mitchell IA, Schuster ALR, Lynch T, et al. Why don't end-of-life conversations go viral? A review of videos on Youtube. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2017;7:197–204. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2014-000805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lattimer TA, Tenzek KE, Ophir Y, et al. Exploring web-based Twitter conversations surrounding national Healthcare decisions day and advance care planning from a Sociocultural perspective: computational mixed methods analysis. JMIR Form Res 2022;6:e35795. 10.2196/35795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. de B. Developing a web-based platform to foster end-of-life planning among LGBT older adults.

- 61. Biswas J, Banik PC, Ahmad N. Physicians’ knowledge about palliative care in Bangladesh: A cross-sectional study using Digital social media platforms. PLoS One 2021;16:e0256927. 10.1371/journal.pone.0256927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Higginson IJ. Research challenges in palliative and end of life care. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2016;6:2–4. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2015-001091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hirschberg J, Manning CD. Advances in natural language processing. Science 2015;349:261–6. 10.1126/science.aaa8685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Greaves F, Ramirez-Cano D, Millett C, et al. Harnessing the cloud of patient experience: using social media to detect poor quality Healthcare. BMJ Qual Saf 2013;22:251–5. 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Naslund JA, Bondre A, Torous J, et al. Social media and mental health: benefits, risks, and opportunities for research and practice. J Technol Behav Sci 2020;5:245–57. 10.1007/s41347-020-00134-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Banda JM, Singh GV, Alser OH, et al. Long-term patient-reported symptoms of COVID-19: an analysis of social media data. Infectious Diseases (except HIV/AIDS) [Preprint]. 10.1101/2020.07.29.20164418 [DOI]

- 67. Nadkarni PM, Ohno-Machado L, Chapman WW. Natural language processing: an introduction. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2011;18:544–51. 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Hopewell-Kelly N, Baillie J, Sivell S, et al. Palliative care research centre’s move into social media: constructing a framework for ethical research, a consensus paper. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2019;9:219–24. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2015-000889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Twitter . Twitter privacy policy. 2023. Available: https://twitter.com/en/privacy#twitter-privacy-3.1 [Accessed 17 Jan 2023].

- 70. Meta . How do we use your information? 2023. Available: https://www.facebook.com/privacy/policy?section_id=2-HowDoWeUse [Accessed 26 Apr 2023].

- 71. Hunter RF, Gough A, O’Kane N, et al. Ethical issues in social media research for public health. Am J Public Health 2018;108:343–8. 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Regulation P. Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council regulation (EU). 2016.

- 73. Smith B. Dying in the social media: when palliative care meets Facebook. Pall Supp Care 2011;9:429–30. 10.1017/S1478951511000460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Aitken M, de St Jorre J, Pagliari C, et al. Public responses to the sharing and linkage of health data for research purposes: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. BMC Med Ethics 2016;17:73:73. 10.1186/s12910-016-0153-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Stockdale J, Cassell J, Ford E. Giving something back”: a systematic review and ethical enquiry into public views on the use of patient data for research in the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland. Wellcome Open Res 2018;3:6. 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.13531.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Di Minin E, Fink C, Hausmann A, et al. How to address data privacy concerns when using social media data in conservation science. Conserv Biol 2021;35:437–46. 10.1111/cobi.13708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Zimmer M. But the data is already public”: on the ethics of research in Facebook. The Ethics of Information Technologies: Routledge 2020;229–41. 10.4324/9781003075011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Hewson C, Buchanan T, eds. Ethics Guidelines for Internet-Mediated Research. The British Psychological Society, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 79. Lazer D, Kennedy R, King G, et al. The parable of Google flu: traps in big data analysis. Science 2014;343:1203–5. 10.1126/science.1248506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Knaul FM, Farmer PE, Bhadelia A, et al. Closing the divide: the Harvard global equity initiative–lancet Commission on global access to pain control and palliative care. The Lancet 2015;386:722–4. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60289-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

spcare-2023-004579supp001.pdf (112.2KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information.