Abstract

Introduction

Hip and knee osteoarthritis (OA) are increasingly common with a significant impact on individuals and society. Non-pharmacological treatments are considered essential to reduce pain and improve function and quality of life. EULAR recommendations for the non-pharmacological core management of hip and knee OA were published in 2013. Given the large number of subsequent studies, an update is needed.

Methods

The Standardised Operating Procedures for EULAR recommendations were followed. A multidisciplinary Task Force with 25 members representing 14 European countries was established. The Task Force agreed on an updated search strategy of 11 research questions. The systematic literature review encompassed dates from 1 January 2012 to 27 May 2022. Retrieved evidence was discussed, updated recommendations were formulated, and research and educational agendas were developed.

Results

The revised recommendations include two overarching principles and eight evidence-based recommendations including (1) an individualised, multicomponent management plan; (2) information, education and self-management; (3) exercise with adequate tailoring of dosage and progression; (4) mode of exercise delivery; (5) maintenance of healthy weight and weight loss; (6) footwear, walking aids and assistive devices; (7) work-related advice and (8) behaviour change techniques to improve lifestyle. The mean level of agreement on the recommendations ranged between 9.2 and 9.8 (0–10 scale, 10=total agreement). The research agenda highlighted areas related to these interventions including adherence, uptake and impact on work.

Conclusions

The 2023 updated recommendations were formulated based on research evidence and expert opinion to guide the optimal management of hip and knee OA.

Keywords: Osteoarthritis, Knee; Osteoarthritis; Rehabilitation; Physical Therapy Modalities; Therapeutics

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common joint disease worldwide,1 with an increasing global burden of disability and healthcare utilisation.2 The number of people with OA globally rose by 28% from 2010 to 2019, affecting over 500 million people, and about 6%, worldwide.3 Due to an ageing population, increasing obesity and sport-related joint injuries, the disease will become even more prevalent in the forthcoming years.2 In 2019, OA was the 15th highest-ranked cause of years lived with disability (YLDs) worldwide and was responsible for 2% of the total global YLDs.3 OA is regarded as a severe disease, and serious condition and people with OA commonly experience pain, stiffness and associated functional loss.4 Optimal management of hip and knee OA has important implications for the individual and society through the potential for improving individual health, work participation and utilisation of healthcare services. However, most people with OA do not receive optimal management.5 6 In order to reduce the evidence-to-practice gap and the future burden7 of this disease, the healthcare services’, policy-makers’ and the population awareness of the importance and benefits of evidence-based management of OA must be improved.

EULAR recommendations, including priorities for implementation and future research, can play a role in increasing awareness and uptake of best evidence care. In 2013, an EULAR Task Force (TF) developed recommendations for the non-pharmacological core management of hip and knee OA.8 Since then there remains no cure in sight for OA, and effective disease-modifying drugs are lacking.2 Therefore, non-pharmacological approaches are still considered a core treatment for people with hip and knee OA, aiming to alleviate symptoms and improve or maintain physical function. Since the publication of the 2013 recommendations, a large number of studies on the effectiveness of core non-pharmacological treatment modalities and new methods for delivery and follow-up of such treatments have been published. An update of these recommendations would potentially have implications for the level of evidence (LoE) categories and could lead to revisions of the recommendations and formulation of new recommendations with important implications for OA management.

The main aim of this TF process was to update the 2013 evidence-based recommendations for non-pharmacological core management, provide additional details on effectiveness, safety and cost-effectiveness, and formulate research and educational agendas and priorities for implementation activities. The target groups for the updated recommendations are people with hip or knee OA, all healthcare providers involved in the delivery of non-pharmacological interventions in OA care, researchers in the field of OA, officials in healthcare governance and reimbursement agencies and policy-makers.

Methods

The Standardised Operating Procedures for EULAR-endorsed Recommendations9 were used as a framework for this project. The structure of the manuscript is guided by the Appraisal of Guidelines, Research and Evaluation instrument.10

To pursue the task of updating the 2013 recommendations, a multidisciplinary TF with in-depth knowledge of non-pharmacological OA care was established. The TF consisted of 25 members from 14 European countries and included 9 physiotherapists, 6 rheumatologists, 2 orthopaedic surgeons, 2 psychologists, 2 patient research partners, 1 occupational therapist, 1 nurse, 1 general practitioner and 1 nutrition expert. A steering group, including a convenor (NØ), a methodologist (TPMVV) and a research fellow (TM), managed the process.

During the first digital TF meeting, the rationale for the update of the recommendations was presented, and the definition of core non-pharmacological management was clarified. The TF agreed on 11 research questions based on the research propositions from the 2013 recommendation. For the subsequent systematic literature review (SLR), the research questions were organised according to the population, intervention, control and outcome (PICO) format with associated search terms (online supplemental file 1). The new search terms added to the previous search strategy were related to the following topics: remote care, shared decision-making, psychological interventions/cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT)-based interventions and specific exercise modalities (eg, strength training and aerobic exercise). Due to the expected large body of published literature since the previous literature review from 2012, combined with the available resources and strict timeline for this update, it was decided that this SLR should primarily focus on evidence from systematic reviews (SRs) and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and secondarily on evidence from single RCTs. As this SLR was an update of a previously unpublished SLR, along with its pragmatic approach, it was decided that the details were best presented as online supplemental file 1 rather than a publication of its own.

ard-2023-225041supp001.pdf (2.8MB, pdf)

The SLR was conducted by the fellow and convenor in close collaboration with an experienced librarian (HIF) and with support from the methodologist. Three main literature searches were conducted in the databases Medline (Ovid), Embase (Ovid), AMED (Ovid), Cochrane Library (Cochrane TRIALS), CINAHL (Ebsco) and Epistemonikos (SR search only).

The primary literature search aimed at identifying relevant SRs of RCTs investigating the effectiveness of core non-pharmacological management strategies as specified in the PICOs. The search was conducted from 2012 (the end year of the previous search) until 17 February 2022 and later updated until 27 May 2022 (online supplemental file 1). Based on the PICOs, two authors (TM and NØ) independently screened titles and abstracts. Potentially relevant studies were read and evaluated in full text. Studies were included if they were SRs, including a meta-analysis of two or more RCTs on people diagnosed with hip or knee OA or with persisting knee pain in people 45 years or older and investigating non-pharmacological core management strategies. Relevant comparisons were no intervention, usual care or any other intervention. Relevant outcomes were pain, physical function, quality of life (QoL), patient global assessment of target joint, adverse effects or cost-effectiveness. The included studies were categorised under the 11 research questions. If relevant, one study could inform multiple research questions. The quality of the included SRs was evaluated with A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews (AMSTAR II).11 The assessments were conducted independently by three assessors (GS, EAB and IS), working in pairs independent of the TF, with experience in quality assessment of SRs and RCTs. Disagreements between the assessors were resolved through discussion.

A second literature search with a comparable search strategy was conducted to identify newer RCTs not included in the latest published SR on the same topic, or relevant RCTs not included in any SRs, or RCTs on research questions for which no relevant SRs were identified. To identify such RCTs published in the past four to 5 years, the search was conducted from 1 January 2018 to 27 May 2022.

A third literature search was conducted with a similar search strategy from 1 January 2012 to 31 December 2017, aiming to identify relevant RCTs specifically on the research questions for which no relevant SRs had been identified. The two last searches were screened independently by the same two authors, and relevant studies were read and evaluated in full text. Studies were included if they were RCTs relevant to the PICOs. The quality of the included RCTs was assessed with the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool 2 (RoB2)12 independently by two researchers (EAB and IS) independent of the TF. Disagreements between the assessors were resolved through discussion.

In the period before the second TF meeting, five digital subgroup meetings were arranged. Groups of 4–5 TF members and the steering group participated in each meeting. The purpose of the subgroup meetings was to go through the relevant results from the SLR and to discuss and prepare preliminary suggestions for revisions and updates of the recommendations to guide the discussion at the second TF meeting. The group discussed between 1 and 3 of the previous 11 recommendations in each subgroup meeting. This method was implemented to allow all TF members to express their opinions in smaller forums and potentially to reduce the workload of the second TF meeting.

During the second digital TF meeting, the results from the SLR, along with the proposed updates from the subgroups, were presented to the whole TF. The previous recommendations and the proposed updates were then discussed in light of the SLR and the expertise of the group. After the discussions and revisions, the TF members voted for consensus on each revised overarching principle and recommendation (defined as 75% or more in favour of the suggested updates). After the meeting, the updated list of recommendations was collated and emailed to the TF members in a digital survey to rate the level of agreement (LoA) on a 0–10 point scale (0=totally disagree, 10=totally agree). Further, the TF voted on the prioritised order of the recommendations for implementation activities. The TF also formulated a research agenda based on identified gaps in the evidence. The steering group defined the LoE and strength of each recommendation in accordance with the Oxford Levels of Evidence.13 The steering group also formulated the educational agenda on behalf of the TF.

Results

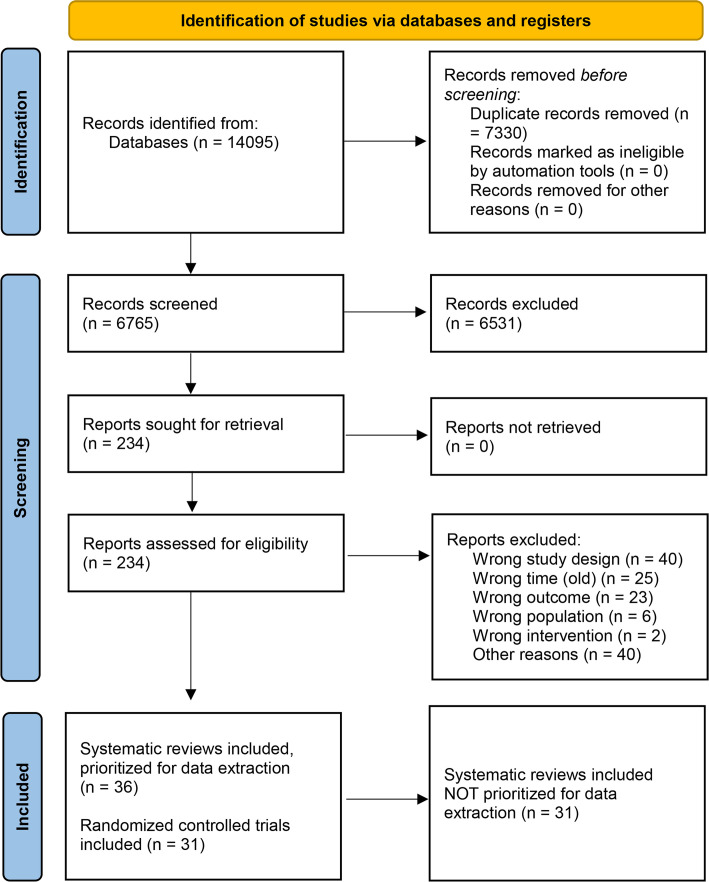

The three systematic literature searches yielded a total of 6816 references after the removal of duplicates (figure 1). From these, 67 SRs and 31 RCTs were initially considered relevant for the SLR. However, we chose to extract data from 36 of the SRs due to reasons elaborated in online supplemental file 1, p.49,. The most frequent reason was that the interventions under study were not considered relevant for this review. The quality of the included SRs was generally poor, with 35 of 36 studies being rated with an overall low or critically low quality by the AMSTAR II tool (online supplemental file 1). The critical items that most often contributed to the overall low quality of the studies were: the lack of an explicit statement that the review methods were established prior to the conduct of the review; the lack of the use of a comprehensive literature search strategy; and lack of a list of excluded studies with reasons for exclusion. There was large variation in the overall quality of the included RCTs as assessed by the RoB2 tool (online supplemental file 1). Most studies with a low risk of bias were on exercise interventions and delivery, whereas there were higher concerns related to the studies on, for example, lifestyle-related interventions. Most commonly, these concerns were related to the elements of measurement of the outcome (eg, the lack of a blinded outcome assessor).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

The main updates to the recommendations are summarised in box 1. The TF agreed to rephrase and change two previous recommendations into overarching principles. These were the recommendations on: (1) the use of a biopsychosocial approach in the initial assessment and (2) the recommendation on individualisation of treatment. It was decided that these were generic statements used to inform the basis for management rather than specific treatment recommendations. Inherent to the nature of these statements, relevant studies were absent from the SLR.14

Box 1. What is new?

The updated recommendations have been reorganised into two overarching principles and eight treatment recommendations.

The wording of each recommendation is condensed.

The level of agreement is above 9 for all recommendations.

The level of evidence is 1a/1b for seven of the eight recommendations.

It was further decided to revise the nine previous recommendations into eight updated recommendations by merging the recommendations on footwear and walking aids, other assistive devices and adaptations. Moreover, to improve readability the previous recommendations were shortened, and subsections were rewritten and moved to the explanatory text. In addition, the TF also discussed the order for the presentation of the recommendations and decided to change this into a more logical sequence.

High LoAs were achieved for all eight recommendations, and seven recommendations were graded with LoE 1a/1b and strength level A. Recommendation 2—on delivery of information, patient education and self-management—was ranked by the TF as having the highest priority for implementation. Table 1 summarises the updated overarching principles, recommendations, LoA, LoE, strength of recommendation and priority for implementation.

Table 1.

Overarching principles and specific recommendations for the non-pharmacological core management of hip and knee osteoarthritis

| Overarching principles (A–B) and recommendations (1–8) | Level of agreement, mean (SD), median (range) | Level of evidence | Strength of recommendation | Prioritised order of implementation, rank | |

| A | In people with hip or knee OA, initial assessment should use a biopsychosocial approach to consider physical and psychological status, activities of daily living, participation including work, social determinants and environmental factors. | 9.8 (0.5), 10 (8–10) | – | – | – |

| B | Treatment of people with hip or knee OA should be based on shared decision-making considering the needs, preferences and capabilities of the individual. | 9.8 (0.5), 10 (8–10) | – | – | – |

| 1 | People with hip or knee OA should be offered an individualised, multicomponent management plan that includes the recommended core non-pharmacological approaches. | 9.8 (0.7), 10 (7–10) | 1a | A | 2 |

| 2 | People with hip or knee OA should be offered information, education and advice on self-management strategies (considering available modes of delivery) and these should be included and reinforced at subsequent clinical encounters. | 9.6 (0.7), 10 (7–10) | 1a | A | 1 |

| 3 | All people with hip or knee OA should be offered an exercise programme (eg, strength, aerobic, flexibility or neuromotor*) of adequate dosage with progression tailored to their physical function, preferences and available services. | 9.6 (0.8), 10 (7–10) | 1a | A | 3 |

| 4 | The mode of delivery of exercises (eg, individual or group sessions, supervised or unsupervised, face to face or by using digital technology, land-based or aquatic exercise) should be selected according to local availability and patient preferences. The exercises preferably should be embedded in an individual plan for physical activity. | 9.6 (0.6), 10 (8–10) | 1a | A | 4 |

| 5 | People with hip or knee OA should be offered education on the importance of maintaining a healthy weight. Those overweight or obese should be offered support to achieve and maintain weight loss. | 9.2 (1.4), 10 (4–10) | 1a | A | 5 |

| 6 | For people with hip or knee OA, consider walking aids, appropriate footwear, assistive devices and adaptations at home and at work to reduce pain and increase participation. | 9.3 (1.0), 10 (6–10) | 1b | A | 8 |

| 7 | People with hip or knee OA with or at risk of work disability should be offered timely advice on modifiable work-related factors and, where appropriate, referral for expert advice. | 9.4 (1.0), 10 (6–10) | 5 | D | 7 |

| 8 | Consider employing elements of behaviour change techniques when lifestyle modifications are needed (eg, physical activity, weight loss) for people with hip or knee OA. | 9.2 (0.8), 9 (8–10) | 1b | A | 6 |

*Neuromotor exercise includes various motor skills, including balance, coordination, gait, agility, proprioceptive training and activities combining neuromotor exercise, resistance exercise and flexibility (eg, tai chi, yoga).

OA, osteoarthritis.

Recommendation 1

People with hip or knee OA should be offered an individualised, multicomponent management plan that includes the recommended core non-pharmacological approaches.

This recommendation deals with the provision of an integrated package of care rather than single treatments alone or in succession. The majority of new, relevant SRs and RCTs informing this recommendation investigated the effectiveness of the combination of patient education and exercise or the combination of patient education, exercise and diet or the combination of behaviour change techniques/pain-coping skills training and exercise, compared with information or one of the treatments alone.15–18 The updated evidence shows that combining treatments leads to larger effects on pain and function compared with providing the treatments separately, thereby providing a rationale for combining different treatment modalities. The combination of education, exercise and dietary weight management was also considered cost-effective compared with physician-delivered usual care investigated in five healthcare systems.19 The TF discussed that, although not all potential combinations of treatments are investigated in meta-analyses or newer RCTs, the results of available studies are likely to be generalisable to different combinations. Thus, the TF agreed on the general consideration of multicomponent treatments from a broader spectrum of potential combinations based on an assessment of a patient’s individual needs and preferences.

Through the SLR, no specific evidence was retrieved with regard to the effects of pacing and maintenance of activity. This specific element was therefore removed from the recommendation.

Recommendation 2

People with hip or knee OA should be offered information, education and advice on self-management strategies (considering available modes of delivery) and these should be included and reinforced at subsequent clinical encounters.

Recommendation 2 concerns the delivery of information, education and advice on self-management strategies. New evidence from the SLR showed zero to small significant effects on pain and function from patient education as a single intervention in the short term, which is in line with the previous recommendation.15 20 In 2013, this recommendation focused on how education and information should be delivered in terms of being individualised, being included in every aspect of management, and specifically addressing the nature, causes, consequences and prognosis of OA. Moreover, it was stated that this should be reinforced and developed, supported by written or other types of material, including partners or carers of the individual, if relevant. The current TF acknowledged the importance of these aspects to ensure the effective delivery of information and education for people with hip and knee OA. However, none of the studies from the SLR could provide specific evidence for any of these aspects, except with regard to delivery method. One SR reported the effects of patient education delivered through telephone when compared with usual care, but the results were not significant for pain or disability.20 The TF further chose to add self-management to the updated recommendation. Evidence from two SRs, including seven RCTs, compared structured self-management programmes against a large range of control interventions. Zero to small favourable effects were found for self-management, delivered face to face or digitally, compared with routine/usual care.21 22 Despite the limited effects reported in the literature, the TF agreed that self-management is a concept closely related both to the delivery of information and education in a clinical setting and to the uptake of other relevant treatment modalities.

Recommendation 3

All people with hip or knee OA should be offered an exercise programme (eg, strength, aerobic, flexibility or neuromotor) of adequate dosage with progression tailored to their physical function, preferences and available services.

The body of literature investigating the effects of different types of exercise regimes was already large when the 2013 recommendations were published. Aiming to progress the knowledge on the effects of exercise for hip and knee OA, the current SLR did not focus on studies investigating the effects of general exercise on hip and knee OA as these effects were well established previously.23 24 The aim was rather to identify studies investigating the effects of well-defined exercise modalities, as well as studies looking more specifically into exercise dosage.

For hip OA, one SR summarised the effects of supervised, progressive resistance training, which reported beneficial effects on pain, function and QoL. The effect sizes, however, were small with large CIs.25

For knee OA, four SRs and five additional RCTs were identified on the exercise26–28 modalities Tai Chi, yoga, stationary cycling, proprioceptive training, weight-bearing and non-weight bearing exercise, and neuromuscular exercise combined with strength training.29–33 Overall, the results showed small to moderate positive effects on pain and function for all these exercise modalities compared with no-exercise control (no intervention, waiting list or non-exercise interventions). Still, the results were less clear in head-to-head comparisons of different exercise types, modalities or doses.

In summary, results showed that a variety of exercise modalities might lead to improved pain and function for people with hip or knee OA, making it difficult to recommend one type of exercise over another. The optimal exercise dosage is also difficult to establish, with evidence from 1 SR on hip OA (including 12 RCTs) and 1 SR on knee OA (including 45 RCTs) providing some evidence that exercise in line with dose recommendations from the American College of Sports Medicine provided larger improvements in pain compared with non-compliant exercise programmes.34–36 The differences, however, were small, and the clinical relevance is debatable. Two newer RCTs on knee OA, comparing high-intensity to low-intensity resistance training or no-exercise control, found no or only small between-group differences with regard to pain and function,37 38 thus making it difficult to make explicit recommendations on exercise dosage.

With respect to safety, adverse events in exercise studies for hip and knee OA were investigated in two SRs.39 40 The two studies concluded that, although the report of adverse events in exercise studies was inconsistent and some patient drop-outs were potentially misclassified, adverse events were generally uncommon and non-serious, and that exercise seemed to be associated with minimal risk of harm. Concerning the economic aspects of exercise, one SR on cost-effectiveness found that in the majority of the 12 included studies, exercise for hip and knee OA showed cost-effectiveness at conventional willingness-to-pay thresholds.19

The TF chose to update this recommendation, highlighting that the choice of exercise should be based on individual function, patient preferences and available services.41 Overall, exercise is by far the most studied and strongly recognised non-pharmacological core management treatment option and this recommendation has the strongest evidence base. The TF also expressed the importance of maintaining exercise over time for the positive effects to persist.

Recommendation 4

The mode of delivery of exercises (eg, individual or group sessions, supervised or unsupervised, face to face or by using digital technology, land-based or aquatic exercise) should be selected according to local availability and patient preferences. The exercises preferably should be embedded in an individual plan for physical activity.

As established in the description of recommendation 3, there is convincing evidence for the effectiveness of various exercise modalities on pain and function in hip and knee OA. However, the delivery method of exercise programmes varies largely across studies and may influence study outcomes.

One SR found superior effects from technology-supported exercise compared with control with non-technological or no care services on pain, function and QoL,42 whereas another SR found superior effects from telehealth-based exercise compared with no-telehealth exercise control for pain but not for function or QoL.43 The reported effect sizes were small. One additional RCT found a small, significant effect on function at 6 months follow-up for an education combined with strengthening exercise follow-up through telephone calls compared with education alone, but no other between-group differences in pain and function were detected after 6 and 12 months.44 Another RCT comparing access to an educational website combined with exercise supported by automated behaviour change text messages to access to the educational website alone found significant superior effects of the combined first intervention on pain and function after 24 weeks.45 For aquatic exercise, one SR reported small short-term beneficial effects for pain and function compared with no intervention or usual care. However, another SR comparing aquatic exercise to land-based exercise did not find any of these modes superior to the other.46 47 One RCT of a three-stage stepped care exercise programme compared with educational materials found beneficial, although not clinically relevant, effects of the stepped care programme on pain and function at 3 and 9 months, but not at 6 months.48 Analyses of the cost-effectiveness of the same stepped-care intervention concluded that there is a high probability of short-term cost-effectiveness.49

The new evidence adds information on technology-supported delivery of exercise, aquatic exercise and a stepped care strategy for exercise delivery. The results from these studies show a wide variety of potentially effective delivery methods for exercise, which in clinical practice should be aligned with patient preferences and the availability of local services. The TF also underlined the importance of the exercise programme being embedded in an individual plan for physical activity. Such plans should be set up in accordance with well-recognised recommendations for physical activity, such as from the WHO or EULAR.41 50 General physical activity has multiple health benefits and is also important for the management of common comorbidities associated with OA, such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes.51 52

Recommendation 5

People with hip or knee OA should be offered education on the importance of maintaining a healthy weight. Those overweight or obese should be offered support to achieve and maintain weight loss.

In the updated SLR, three SRs were identified, including one network meta-analysis investigating the effects of weight loss interventions. Two were on studies of knee OA,19 53 whereas the third included studies of both hip and knee OA, although only 2 of the 19 trials included in that study were conducted on a mixed hip and knee OA population.54 The results from this SR showed beneficial effects, compared with minimal care, of both diet and multifocused weight-loss interventions (combining diets, telephone coaching, psychological pain-coping interventions/CBT, specialist referral education and exercise) on pain and disability, with the largest effect size on pain for multifocused interventions. Further, it was reported that when comparing weight-loss-focused interventions (diets) to exercise, no between-group differences were detected for pain or disability. When comparing combined interventions of dietary weight loss and exercise to dietary weight loss or exercise alone, small effects were found in favour of the combined intervention.

In the network meta-analysis, bariatric surgery was the most effective pain-reducing intervention, followed by a low-calorie diet combined with exercise intervention.53 The last SR on knee OA used cost-effectiveness as an outcome and reported that an intensive 18-month diet and exercise intervention with the goal of 5% weigth loss was likely to be an efficient use of healthcare resources compared with a healthy lifestyle control.19

The above-mentioned studies made it clear that there is increasing evidence supporting multifocused weight loss interventions as beneficial for OA pain and disability. Therefore, the TF recommended that people with overweight or obesity and OA should be offered support to achieve and maintain weight loss. The TF notes that the amount of evidence mainly stems from studies on knee OA. As overweight and obesity are strong risk factors for the development and progression of OA, and in particular knee OA,2 the TF also wanted to add to the recommendation the importance of education on the benefits of maintaining a healthy weight.

Recommendation 6

For people with hip or knee OA, consider walking aids, appropriate footwear, assistive devices and adaptations at home and at work to reduce pain and increase participation.

Through the SLR, four SRs investigating the effects on knee OA of lateral wedge insoles compared with other types of insoles, including flat/neutral insoles or knee braces, were retrieved. These studies did not report any between-group differences for any comparisons on pain or function.55–58 On the other hand, one RCT reported a small between-group difference in favour of lateral wedge insoles compared with neutral insoles on a single pain scale in people prescreened to knee adduction moment improvements (but not on other pain scales, function or QoL).59 For footwear, one RCT found positive effects of biomechanical footwear with individually adjustable external convex pods attached to the outsole compared with control footwear.60 Another RCT found small effects after 6 months on pain, but not on function, from wearing stable, supportive shoes over flat flexible shoes for at least 6 hours per day.61

Summarised, most evidence did not support the use of any lateral wedged or other insoles to affect pain or function in knee OA. The results from one RCT provided some support for the use of stable, supportive shoes. The TF wanted to add that from a clinical perspective, the use of comfortable shoes, big enough to give ample space for the toes when weight-bearing, is still a general recommendation for people with hip and knee OA.

For other types of assistive aids and devices, two RCTs comparing the use of canes to the non-use of auxiliary gait devices were identified. The results were contradictory, and conclusions on the effect of cane were difficult to draw from the available evidence.62 63 No studies were retrieved for other types of assistive devices or home adaptations. Based on the expert knowledge of the group, it was argued that such devices could still be useful to some people with hip or knee OA in terms of reducing pain, undertaking daily activities and improving participation. The TF wanted to emphasise that improving participation is an important aspect underpinning this specific recommendation. Assistive devices may serve as means to reduce pain and improve participation both at home and at work and should, therefore, be considered in that context. Examples of such devices might be devices to aid dressing, height-adjustable chairs, raised toilet seats, handrails in staircases or the use of appropriate walking aids.

Recommendation 7

People with hip or knee OA with or at risk of work disability should be offered timely advice on modifiable work-related factors and, where appropriate, referral for expert advice.

OA is one of the leading causes of reduced work participation, and the disease may critically affect the number of sick days and, ultimately, the extension of a person’s work career.64 Although there are well-known occupational risk factors, such as heavy lifting and knee straining activities associated with the development of knee OA,65 it was noted that there is a lack of studies on vocational rehabilitation for people with hip or knee OA. In the current update, only one relevant RCT was retrieved. This study used workability as an outcome, whereas the study intervention in both groups focused on self-management with the addition of an activity tracker in the intervention group. In this study, no between-group differences were reported for workability.66

Although little research has been conducted, the TF considered that appropriate interventions to increase work participation for people with hip and knee OA are highly relevant. A proper assessment of the individual work situation may have a large impact and should receive attention during consultations.67 Health professionals, in cooperation with the employer, should be able to offer timely advice on modifiable work-related factors such as working from home, the use of height-adjustable desks and office chairs, the possibility of changing work tasks, commuting to/from work, use of assistive technology, and receiving support from management, colleagues and family towards employment. The TF also noted that adaptations to improve workability might be considered and applied not only at the workplace but also in the home.

Recommendation 8

Consider employing elements of behaviour change techniques when lifestyle modifications are needed (eg, physical activity, weight loss) for people with hip or knee OA.

This recommendation concerns the potential need for lifestyle change in people with hip and knee OA. It focuses specifically on physical activity and weight loss as part of a healthy lifestyle since these aspects are specifically relevant for people with hip or knee OA. One SR and eight additional RCTs were identified on various interventions to enhance a healthy lifestyle, mainly through maintaining physical activity over time. The SR reported small to moderate effects of adding booster sessions to exercise programmes to improve mid-term to long-term adherence to exercise.68 Furthermore, one RCT reported statistically significant improvements in pain and function from a combined programme of pain coping skills training and lifestyle behavioural weight management lasting 24 weeks compared with these interventions alone or standard care.69 Interventions from the other RCTs aiming to support people with OA to improve their lifestyle and sustain such changes over time, included interventions of behaviour-graded activity, improving exercise adherence with telephone counselling, an app to enhance a healthy lifestyle, physical activity with telephone follow-up and a self-management lifestyle intervention.70–72 However, when the effects on pain and function of these interventions were compared with standard care or other minimal interventions, none to very small between-group differences were observed for the comparisons. The TF wanted to enhance the importance of long-term follow-up on health behaviour change and not just recommend lifestyle change as a single intervention. The TF also discussed that the EULAR recommendation on core competencies for health professionals in rheumatology underlines that health professionals should be able to provide the principles of behaviour change techniques in the management of people with rheumatic and musculoskeletal disorders.73

Research and educational agendas

The proposed research agenda (table 2) was based on gaps identified in the literature and on topics which emerged during discussions among the TF members.

Table 2.

Research agenda for the non-pharmacological core management of people with hip and knee osteoarthritis

| Theme | Research questions |

| Hip OA | What are the benefits and harms of non-pharmacological treatment modalities for people with hip OA? |

| Weight | What are the benefits and harms of weight loss for people with hip OA? |

| What are the long-term effects of weight loss for people with hip or knee OA? | |

| Exercise | What are the mechanisms for beneficial effects of exercise on hip or knee OA? |

| What is the optimal exercise dosage/how to prescribe an optimal exercise dosage for people with hip or knee OA? | |

| What is the minimum exercise dosage in order to achieve beneficial effects in people with hip or knee OA? | |

| Adherence | How can we improve long-term adherence to non-pharmacological treatment in people with hip or knee OA? |

| Uptake | How can we improve the uptake of core management strategies from treatment recommendations in people with hip or knee OA? |

| Work | What are the benefits and harms of interventions to improve or maintain work ability in people with hip or knee OA? |

OA, osteoarthritis.

The education agenda (table 3) highlights activities relevant to promote appropriate management of people with hip and knee OA.

Table 3.

Educational agenda for the non-pharmacological core management of people with hip and knee OA

| 1 | Increase the knowledge about hip and knee OA among health professionals and people living with OA |

| 2 | Increase the knowledge about recommended hip and knee OA management among health professionals and people living with OA |

| 3 | Contribute to regular updates and training for health professionals to ensure delivery of high-quality OA care |

| 4 | Collaborate with the authors of the EULAR online course for health professionals to ensure that the educational content aligns with the current recommendations |

OA, osteoarthritis.

Discussion

Through this update, the recommendations for the non-pharmacological core management of hip and knee OA have been revised into two overarching principles and eight treatment recommendations. The revisions are based on research evidence, expert discussions and consensus. Since the publication of the 2013 recommendations, a number of new studies have been published on non-pharmacological treatment modalities and their methods of delivery. The updates to the recommendations are thus well anchored in evidence from research and the perspectives of the TF members, representing different professional, cultural and personal backgrounds, including the perspective of people with OA. The process led to a broad consensus within the TF on the updated principles and recommendations, reflected by the high LoA for all the revised recommendations. Such strong consensus gives reason to believe that the recommendations are suitable for use and implementation across European healthcare systems. These recommendations are also in line with recently published treatment recommendations for hip and knee OA by other societies.74–76

The number of relevant SRs and RCTs retrieved through the SLR was high, especially for the research questions concerning exercise and delivery of exercise, with data drawn from a total of 15 SRs and 11 additional RCTs. The number of new studies led to an upgrade of the LoE for most of the recommendations, and seven of eight recommendations are now supported by level 1a or 1b evidence. However, it should be noted that the stated LoE does not necessarily involve all aspects of every recommendation and does not distinguish between hip and knee OA. The number of studies on hip OA was markedly lower than those on knee OA for all the treatment modalities. Therefore, the recommendations are generally weaker for hip OA than knee OA. There is an increasing recognition of differences between hip and knee OA, which heightens the need for more hip OA-specific studies to improve outcomes for this group specifically.77 This is also highlighted in the proposed research agenda (table 2). Further, as the aim was to address relevant non-pharmacological core management strategies, the recommendations do not specifically advise the management of subgroups of the OA population, for instance, younger adults or adults with a high burden of comorbidities. The authors are also aware of a number of ongoing studies addressing a range of innovative digital programmes in OA care. Such approaches will likely receive further attention in future updates of these recommendations.78–81

With regard to outcomes, most of the included studies reported effects primarily on pain and physical function. To follow the recommendations on prioritised outcomes in OA research,82 more studies investigating the effects of interventions on QoL and patients’ global assessment of the target joint may have provided additional relevant information. Workability and cost-effectiveness are two other outcomes of increasing interest when investigating the effect of interventions from a broader perspective. This SLR identified some studies including these outcomes, thus adding new and important knowledge to the recommendations. Nevertheless, additional studies with a focus on interventions to prevent the decline in workability and studies examining cost-effectiveness are still needed as such knowledge is important for healthcare governance and policy-makers when planning and prioritising effective OA care. Another relevant aspect of this update is the inclusion of studies investigating potential harm or adverse events from the interventions under study. Only two SRs specifically looking into this subject were identified. Still, the results add new knowledge to this important, although understudied, aspect of non-pharmacological interventions.83

The challenges of implementing recommended care for people with hip and knee OA are well documented.84 It is also apparent that developing recommendations is not sufficient on its own to influence practice.85 Therefore, efforts have been made to address the impact and to develop strategies for the implementation of treatment recommendations. For future implementation, collaboration with other organisations focusing on OA care, such as The Osteoarthritis Research Society International, must be considered. EULAR highlights that implementing all recommendations at once is probably not feasible in practice.86 The TF voted that the recommendation on information, education and self-management was ranked as the recommendation with the highest priority for implementation. This recommendation may play an important role as a basis for all other management and may improve people’s ability to live a good life with OA, as well as being an enabler of, aspects such as physical activity.87 The prioritisation of the recommendations for implementation activities is also important with respect to the effective utilisation of healthcare services. As the OA population is growing, the need for effective healthcare utilisation and sustainable management strategies to improve outcomes will be vital to minimising the burden of OA at an individual and a societal level.88

To conclude, the TF reached a broad consensus on the updated recommendation for non-pharmacological core OA management as well as on a research agenda highlighting the current evidence gaps, on an educational agenda and on the priority of the recommendations to support implementation activities.

Acknowledgments

We thank the librarian Hilde Iren Flaatten, University of Oslo, Norway, for supporting the literature searches and Emilie Andrea Bakke, Ingrid Skaalvik and Geir Smedslund, Diakonhjemmet Hospital, Center for treatment of Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Diseases (REMEDY), Norwegian National Advisory Unit on Rehabilitation in Rheumatology, Oslo, Norway, for their thorough work in the AMSTAR II and Cochrane risk of bias assessments of the included studies.

PGC is funded in part by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) through the Leeds Biomedical Research Centre.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Josef S Smolen

@DrS_Battista

Contributors: TM was the research fellow for the project, undertaking the SLR in cooperation with NØ. The fellow was supervised by the steering group consisting of NØ (convenor) and TPMVV (methodologist). NØ and TPMVV supervised the process of the SLR. NØ organised and chaired the TF meetings. TM drafted the manuscript with advice from NØ and TPMVV. All authors have contributed to the recommendations by participating in the TF meetings; during discussion and agreement on the recommendations; revising and approving the manuscript for publication.

Funding: This study was funded by European League Against Rheumatism (HPR055).

Disclaimer: The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Competing interests: TPMVV was the Vice president EULAR health professionals 2020–2022 and is part of the EULAR Advocacy Committee 2020–present. MG holds a leadership position in OpenReuma/Spanish Association of Health Professionals in Rheumatology (unpaid). CDM received Grants from Versus Arthritis, MRC, NIHR (paid to Keele University) and is the director of the NIHR School for Primary Care Research. SL received payment as scientific consultant from Arthro Therapeutics AB and received payment from AstraZeneca as a member of DSMB. DC received grants from Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia SFRH/BD/148420/2019 and Pfizer (ID 64165707). GZ received payment for expert testimony from Casa di Cura San Francesco, Verona and Support for attending meetings and/or travel from Orthotech and Jtech, payment for participation on a Data Safety Monitoring Board or Advisory Board from VIVENKO for Gruenenthal and Ethos for Angelini and holds other financial interests related to clinical practice as an orthopedic surgeon (performing total joint replacement, arthroscopies and other types of surgeries), either directly from private patients or indirectly from the health system or insurances acting as a private consultant. JEV has received payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from Lilly Netherlands BV. TG has received paid honoraria for lectures by Abbvie, Novartis, Boehringer Ingelheim, UCB, Berlin-Chemie/A. Menarini Bulgaria, Sandoz and received support for attending meetings by Abbvie, Pfizer and UCB. DW is an International Advisory Board Member of DRFZ (Germany) 2019–current and was the EULAR PARE Chair 2015–2017and an EULAR Vice President representing PARE 2017–2021.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1. EULAR RheumaMap . A research roadmap to transform the lives of people with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases; 2019.

- 2. Hunter DJ, Bierma-Zeinstra S. Osteoarthritis. Lancet 2019;393:1745–59. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30417-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network . Global burden of disease study. 2019. Available: http://www.healthdata.org/results/gbd_summaries/2019/osteoarthritis-level-3-cause

- 4. Hawker GA. Osteoarthritis is a serious disease. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2019;37 Suppl 120:3–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Basedow M, Esterman A. Assessing appropriateness of osteoarthritis care using quality indicators: a systematic review. J Eval Clin Pract 2015;21:782–9. 10.1111/jep.12402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hagen KB, Smedslund G, Østerås N, et al. Quality of community-based osteoarthritis care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2016;68:1443–52. 10.1002/acr.22891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Safiri S, Kolahi A-A, Smith E, et al. Global, regional and national burden of osteoarthritis 1990-2017: a systematic analysis of the global burden of disease study 2017. Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79:819–28. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-216515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fernandes L, Hagen KB, Bijlsma JW, et al. EULAR recommendations for the non-pharmacological core management of hip and knee osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:1125–35. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. van der Heijde D, Aletaha D, Carmona L, et al. Update of the EULAR standardised operating procedures for EULAR-endorsed recommendations. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:8–13. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ 2010;182:E839–42. 10.1503/cmaj.090449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ 2017;358. 10.1136/bmj.j4008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Higgins JPT SJ, Page MJ, Elbers RG, et al. Cochrane Handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version; 2022. 6–3.

- 13. OCEBM Levels of Evidence Working Group* . The Oxford levels of evidence 2. Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine; 2011. Available: https://www.cebm.ox.ac.uk/resources/levels-of-evidence/ocebm-levels-of-evidence [Google Scholar]

- 14. de Rooij M, van der Leeden M, Cheung J, et al. Efficacy of tailored exercise therapy on physical functioning in patients with knee osteoarthritis and comorbidity: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2017;69:807–16. 10.1002/acr.23013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Goff AJ, De Oliveira Silva D, Merolli M, et al. Patient education improves pain and function in people with knee osteoarthritis with better effects when combined with exercise therapy: a systematic review. J Physiother 2021;67:177–89. 10.1016/j.jphys.2021.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Alrushud AS, Rushton AB, Kanavaki AM, et al. Effect of physical activity and dietary restriction interventions on weight loss and the musculoskeletal function of overweight and obese older adults with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and mixed method data synthesis. BMJ Open 2017;7:e014537. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hall M, Castelein B, Wittoek R, et al. Diet-induced weight loss alone or combined with exercise in overweight or obese people with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2019;48:765–77. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2018.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pitsillides A, Stasinopoulos D, Giannakou K. The effects of cognitive behavioural therapy delivered by physical therapists in knee osteoarthritis pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Bodyw Mov Ther 2021;25:157–64. 10.1016/j.jbmt.2020.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mazzei DR, Ademola A, Abbott JH, et al. Are education, exercise and diet interventions a cost-effective treatment to manage hip and knee osteoarthritis? A systematic review. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2021;29:456–70. 10.1016/j.joca.2020.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. O’Brien KM, Hodder RK, Wiggers J, et al. Effectiveness of telephone-based interventions for managing osteoarthritis and spinal pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PeerJ 2018;6:e5846. 10.7717/peerj.5846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wu Z, Zhou R, Zhu Y, et al. Self-management for knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pain Res Manag 2022. 10.1155/2022/2681240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Safari R, Jackson J, Sheffield D. Digital self-management interventions for people with osteoarthritis: systematic review with meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res 2020;22:e15365. 10.2196/15365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Uthman OA, van der Windt DA, Jordan JL, et al. Exercise for lower limb osteoarthritis: systematic review incorporating trial sequential analysis and network meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 2014;48:1579. 10.1136/bjsports-2014-5555rep [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Verhagen AP, Ferreira M, Reijneveld-van de Vendel EAE, et al. Do we need another trial on exercise in patients with knee osteoarthritis?: no new trials on exercise in knee OA Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 2019;27:1266–9. 10.1016/j.joca.2019.04.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hansen S, Mikkelsen LR, Overgaard S, et al. Effectiveness of supervised resistance training for patients with hip osteoarthritis - a systematic review. Dan Med J 2020;67:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bennell KL, Nelligan RK, Kimp AJ, et al. What type of exercise is most effective for people with knee osteoarthritis and Co-morbid obesity?: the TARGET randomized controlled trial. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 2020;28:755–65. 10.1016/j.joca.2020.02.838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chen P-Y, Song C-Y, Yen H-Y, et al. Impacts of Tai Chi exercise on functional fitness in community-dwelling older adults with mild degenerative knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled clinical trial. BMC Geriatr 2021;21. 10.1186/s12877-021-02390-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Holm PM, Schrøder HM, Wernbom M, et al. Low-dose strength training in addition to neuromuscular exercise and education in patients with knee osteoarthritis in secondary care - a randomized controlled trial. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 2020;28:744–54. 10.1016/j.joca.2020.02.839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hu L, Wang Y, Liu X, et al. Tai Chi exercise can ameliorate physical and mental health of patients with knee osteoarthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rehabil 2021;35:64–79. 10.1177/0269215520954343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Luan L, Bousie J, Pranata A, et al. Stationary cycling exercise for knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rehabil 2021;35:522–33. 10.1177/0269215520971795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Luan L, El-Ansary D, Adams R, et al. Knee osteoarthritis pain and stretching exercises: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Physiotherapy 2022;114:16–29. 10.1016/j.physio.2021.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wang Y, Wu Z, Chen Z, et al. Proprioceptive training for knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Med 2021;8:699921. 10.3389/fmed.2021.699921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Joshi S, Kolke S. Effects of progressive neuromuscular training on pain, function, and balance in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Physiother 2023;25:179–86. 10.1080/21679169.2022.2052178 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Garber CE, Blissmer B, Deschenes MR, et al. American college of sports medicine position stand. quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and Neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: guidance for prescribing exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2011;43:1334–59. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318213fefb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Moseng T, Dagfinrud H, Smedslund G, et al. The importance of dose in land-based supervised exercise for people with hip osteoarthritis. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 2017;25:1563–76. 10.1016/j.joca.2017.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bartholdy C, Juhl C, Christensen R, et al. The role of muscle strengthening in exercise therapy for knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis of randomized trials. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2017;47:9–21. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2017.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. de Zwart AH, Dekker J, Roorda LD, et al. High-intensity versus low-intensity resistance training in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil 2022;36:952–67. 10.1177/02692155211073039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Messier SP, Mihalko SL, Beavers DP, et al. Effect of high-intensity strength training on knee pain and knee joint compressive forces among adults with knee osteoarthritis: the START randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2021;325:646–57. 10.1001/jama.2021.0411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. James KA, von Heideken J, Iversen MD. Reporting of adverse events in randomized controlled trials of therapeutic exercise for hip osteoarthritis: A systematic review. Phys Ther 2021;101:pzab195. 10.1093/ptj/pzab195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. von Heideken J, Chowdhry S, Borg J, et al. Reporting of harm in randomized controlled trials of therapeutic exercise for knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Phys Ther 2021;101:10. 10.1093/ptj/pzab161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rausch Osthoff A-K, Niedermann K, Braun J, et al. EULAR recommendations for physical activity in people with inflammatory arthritis and osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2018;77:1251–60. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chen T, Or CK, Chen J. Effects of technology-supported exercise programs on the knee pain, physical function, and quality of life of individuals with knee osteoarthritis and/or chronic knee pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2021;28:414–23. 10.1093/jamia/ocaa282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yang Y, Li S, Cai Y, et al. Effectiveness of Telehealth-based exercise interventions on pain, physical function and quality of life in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis. J Clin Nurs 2023;32:2505–20. 10.1111/jocn.16388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hinman RS, Campbell PK, Lawford BJ, et al. Does telephone-delivered exercise advice and support by physiotherapists improve pain and/or function in people with knee osteoarthritis? Telecare randomised controlled trial. Br J Sports Med 2020;54:790–7. 10.1136/bjsports-2019-101183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Nelligan RK, Hinman RS, Kasza J, et al. Effects of a self-directed web-based strengthening exercise and physical activity program supported by automated text messages for people with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2021;181:776–85. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.0991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Dong R, Wu Y, Xu S, et al. Is aquatic exercise more effective than land-based exercise for knee osteoarthritis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97:e13823. 10.1097/MD.0000000000013823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Duan X, Wei W, Zhou P, et al. Effectiveness of aquatic exercise in lower limb osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Rehabil Res 2022;45:126–36. 10.1097/MRR.0000000000000527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Allen KD, Woolson S, Hoenig HM, et al. Stepped exercise program for patients with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 2021;174:298–307. 10.7326/M20-4447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kaufman BG, Allen KD, Coffman CJ, et al. Cost and quality of life outcomes of the stepped exercise program for patients with knee osteoarthritis trial. Value Health 2022;25:614–21. 10.1016/j.jval.2021.09.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. World Health Organization . WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour; 2020. [PubMed]

- 51. Williams MF, London DA, Husni EM, et al. Type 2 diabetes and osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Diabetes Complications 2016;30:944–50. 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2016.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hall AJ, Stubbs B, Mamas MA, et al. Association between osteoarthritis and cardiovascular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2016;23:938–46. 10.1177/2047487315610663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Panunzi S, Maltese S, De Gaetano A, et al. Comparative efficacy of different weight loss treatments on knee osteoarthritis: a network meta-analysis. Obes Rev 2021;22:e13230. 10.1111/obr.13230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Robson EK, Hodder RK, Kamper SJ, et al. Effectiveness of weight-loss interventions for reducing pain and disability in people with common musculoskeletal disorders: A systematic review with meta-analysis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2020;50:319–33. 10.2519/jospt.2020.9041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Khosravi M, Babaee T, Daryabor A, et al. Effect of knee braces and Insoles on clinical outcomes of individuals with medial knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Assist Technol 2022;34:501–17. 10.1080/10400435.2021.1880495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Yu L, Wang Y, Yang J, et al. Effects of orthopedic Insoles on patients with knee osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis and systematic review. J Rehabil Med 2021;53:2793. 10.2340/16501977-2836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zhang J, Wang Q, Zhang C. Ineffectiveness of lateral-wedge Insoles on the improvement of pain and function for medial knee osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis of controlled randomized trials. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2018;138:1453–62. 10.1007/s00402-018-3004-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Zhang B, Yu X, Liang L, et al. Is the wedged Insole an effective treatment option when compared with a flat (placebo) Insole: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2018. 10.1155/2018/8654107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Felson DT, Parkes M, Carter S, et al. The efficacy of a lateral wedge Insole for painful medial knee osteoarthritis after prescreening: a randomized clinical trial. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019;71:908–15. 10.1002/art.40808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Reichenbach S, Felson DT, Hincapié CA, et al. Effect of biomechanical footwear on knee pain in people with knee osteoarthritis: the BIOTOK randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2020;323:1802–12. 10.1001/jama.2020.3565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Paterson KL, Bennell KL, Campbell PK, et al. The effect of flat flexible versus stable supportive shoes on knee osteoarthritis symptoms: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2021;174:462–71. 10.7326/M20-6321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Jones A, Silva PG, Silva AC, et al. Impact of cane use on pain, function, general health and energy expenditure during gait in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:172–9. 10.1136/ard.2010.140178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Van Ginckel A, Hinman RS, Wrigley TV, et al. Impact of cane use on bone marrow lesion volume in people with medial knee osteoarthritis (CUBA trial). Phys Ther 2017;97:537–49. 10.1093/ptj/pzx015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kontio T, Viikari-Juntura E, Solovieva S. Effect of osteoarthritis on work participation and loss of working life–years. J Rheumatol 2020;47:597–604. 10.3899/jrheum.181284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. McWilliams DF, Leeb BF, Muthuri SG, et al. Occupational risk factors for osteoarthritis of the knee: a meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 2011;19:829–39. 10.1016/j.joca.2011.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Östlind E, Eek F, Stigmar K, et al. Promoting work ability with a wearable activity tracker in working age individuals with hip and/or knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2022;23:112. 10.1186/s12891-022-05041-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Gwinnutt JM, Wieczorek M, Balanescu A, et al. EULAR recommendations regarding lifestyle Behaviours and work participation to prevent progression of rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases. Ann Rheum Dis 2023;82:48–56. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-222020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Nicolson PJA, Bennell KL, Dobson FL, et al. Interventions to increase adherence to therapeutic exercise in older adults with low back pain and/or hip/knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 2017;51:791–9. 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Somers TJ, Blumenthal JA, Guilak F, et al. Pain coping skills training and lifestyle behavioral weight management in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled study. Pain 2012;153:1199–209. 10.1016/j.pain.2012.02.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Bendrik R, Kallings LV, Bröms K, et al. Physical activity on prescription in patients with hip or knee osteoarthritis: A randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil 2021;35:1465–77. 10.1177/02692155211008807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Baker K, LaValley MP, Brown C, et al. Efficacy of computer-based telephone counseling on long-term adherence to strength training in elderly patients with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized trial. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2020;72:982–90. 10.1002/acr.23921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Wang Y, Lombard C, Hussain SM, et al. Effect of a low-intensity, self-management lifestyle intervention on knee pain in community-based young to middle-aged rural women: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Arthritis Res Ther 2018;20. 10.1186/s13075-018-1572-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Edelaar L, Nikiphorou E, Fragoulis GE, et al. EULAR recommendations for the generic core competences of health professionals in rheumatology. Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79:53–60. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: Guidelines . Osteoarthritis in over 16s: diagnosis and management. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Copyright © NICE 2022, 2022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Kolasinski SL, Neogi T, Hochberg MC, et al. American college of rheumatology/arthritis foundation guideline for the management of osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care & Research 2019;72:149–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Bannuru RR, Osani MC, Vaysbrot EE, et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee, hip, and polyarticular osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2019;27:1578–89. 10.1016/j.joca.2019.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Hall M, van der Esch M, Hinman RS, et al. How does hip osteoarthritis differ from knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2022;30:32–41. 10.1016/j.joca.2021.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Hall M, Hinman RS, Knox G, et al. Effects of adding a diet intervention to exercise on hip osteoarthritis pain: protocol for the ECHO randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2022;23:215. 10.1186/s12891-022-05128-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Aily JB, de Almeida AC, de Noronha M, et al. Effects of a periodized circuit training protocol delivered by telerehabilitation compared to face-to-face method for knee osteoarthritis: a protocol for a non-inferiority randomized controlled trial. Trials 2021;22:887. 10.1186/s13063-021-05856-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Groves-Williams D, McHugh GA, Bennell KL, et al. Evaluation of two electronic-rehabilitation programmes for persistent knee pain: protocol for a randomised feasibility trial. BMJ Open 2022;12:e063608. 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-063608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Hinman RS, Nelligan RK, Campbell PK, et al. Exercise adherence mobile App for knee osteoarthritis: protocol for the Mappko randomised controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2022;23:874. 10.1186/s12891-022-05816-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Smith TO, Hawker GA, Hunter DJ, et al. The OMERACT-OARSI core domain set for measurement in clinical trials of hip and/or knee osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol 2019;46:981–9. 10.3899/jrheum.181194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Ethgen M, Boutron I, Baron G, et al. Reporting of harm in randomized, controlled trials of Nonpharmacologic treatment for rheumatic disease. Ann Intern Med 2005;143:20–5. 10.7326/0003-4819-143-1-200507050-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Allen KD, Golightly YM, White DK. Gaps in appropriate use of treatment strategies in osteoarthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2017;31:746–59. 10.1016/j.berh.2018.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Dziedzic KS, Allen KD. Challenges and controversies of complex interventions in osteoarthritis management: recognizing inappropriate and discordant care. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2018;57:iv88–98. 10.1093/rheumatology/key062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. EULAR European alliance of Associatons for rheumatology . EULAR Sops standard operating procedures for task forces;

- 87. Kanavaki AM, Rushton A, Efstathiou N, et al. Barriers and facilitators of physical activity in knee and hip osteoarthritis: a systematic review of qualitative evidence. BMJ Open 2017;7:e017042. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Turkiewicz A, Petersson IF, Björk J, et al. Current and future impact of osteoarthritis on health care: a population-based study with projections to year 2032. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2014;22:1826–32. 10.1016/j.joca.2014.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

ard-2023-225041supp001.pdf (2.8MB, pdf)