Summary

Nucleic acid therapeutics offer tremendous promise for addressing a wide range of common public health conditions. However, the in vivo nucleic acids delivery faces significant biological challenges. Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) possess several advantages, such as simple preparation, high stability, efficient cellular uptake, endosome escape capabilities, etc., making them suitable for delivery vectors. However, the extensive hepatic accumulation of LNPs poses a challenge for successful development of LNPs-based nucleic acid therapeutics for extrahepatic diseases. To overcome this hurdle, researchers have been focusing on modifying the surface properties of LNPs to achieve precise delivery. The review aims to provide current insights into strategies for LNPs-based organ-selective nucleic acid delivery. In addition, it delves into the general design principles, targeting mechanisms, and clinical development of organ-selective LNPs. In conclusion, this review provides a comprehensive overview to provide guidance and valuable insights for further research and development of organ-selective nucleic acid delivery systems.

Subject areas: Drug delivery system, Nanoparticles, Nucleic acids

Graphical abstract

Drug delivery system; Nanoparticles; Nucleic acids

Introduction

Nucleic acid therapeutics, such as messenger RNA (mRNA) and small interfering RNA (siRNA), play a critical role in in vivo nucleic acid transfection, by increasing or suppressing target protein expression for disease treatment. These approaches hold significant promise for addressing a wide range of common public health conditions.1 However, due to its inherent characteristics, in vivo delivery of nucleic acids faces significant biological barriers.2 The dense extracellular matrix (ECM), as the initial barrier, inhibits the transport of nucleic acids from the extracellular environment to the target cells.3 Moreover, during circulation in the bloodstream, nucleic acids may be engulfed by the mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS), leading to their accumulation in the spleen and liver.4 Furthermore, only a few nucleic acids that successfully pass through the extracellular barrier face subsequent obstacles, such as cell membrane blockage and endocytic entrapment, due to their substantial molecular size and negative charge. These hindrances prevent their release into the cytoplasm as only 1–4% of nucleic acids can effectively escape from endosomes to fully perform their biological functions.5,6 Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop ideal delivery strategies that not only shield nucleic acids from ribozyme interference but also enable them to overcome various biological barriers efficiently, maximizing their vital biological functions with minimal toxicity and high organ selectivity.7

LNPs are nano-sized, spherical particles normally used as carriers for encapsulating RNA for delivery purposes.8 LNPs possess distinctive advantages, such as simple formulation, high stability, high encapsulation efficiency, efficient cellular internalization, endosomal escape capabilities, and low immunogenicity.9 Their efficiency as RNA delivery systems has been well-documented in numerous reports, garnering widespread attention.10,11 Typically, LNPs formulation consists of phospholipids, cholesterol, PEGylated lipids, and key lipids. Phospholipids enhance the cellular uptake of LNPs, while cholesterol, a natural component of the cell membrane, improves LNPs stability by filling intervals between lipids and promoting fusion with endosomal membranes upon uptake.12 PEGylated lipid components prevent LNPs aggregation, boost stability, provide a stealth effect, and prolong systemic circulation.13 In addition, the proportion of PEGylated lipids may determine the size of LNPs, with approximately 1.5% PEGylated lipids being considered ideal.14 Key lipids, including ionizable lipids (ILs) and cationic lipids (CLs), are essential for maintaining the structural integrity of LNPs, ensuring efficient intracellular delivery, and promoting cytoplasmic release of RNA.15,16 One key difference between ILs and CLs lies in the presence of secondary or tertiary amine heads in the hydrophilic head group of ILs. This feature renders ILs positively charged under acidic conditions while remaining neutral at physiological pH 7.4.17 Hence, ionizable LNPs are relatively non-toxic and non-immunogenic, surpassing other nanoparticles in these aspects.18

Although LNPs have been clinically approved for the treatment of human diseases, the predominant accumulation of LNPs in the liver poses a challenge to the successful development of nucleic acid therapeutics for extrahepatic diseases. This challenge is largely attributed to the interaction of apolipoprotein E (ApoE) and low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR).19 Additionally, due to their nanoscale size, LNPs are unable to be filtered by the kidneys, and 30–90% of intravenously administered LNPs become entrapped in the liver’s sinusoid lumen and Disse’s space.20 Therefore, it is crucial to achieve precise nucleic acids delivery with LNPs to target specific organs, tissues, or even individual cells to treat extrahepatic diseases.21 Furthermore, ensuring mRNA expression in targeted cells or organs is critical for therapeutic efficacy and a prerequisite for clinical translation. Encouragingly, extensive research indicates that, by rational design and high-throughput screening, LNPs hold substantial promise for improving delivery efficiency and targeting precision.22,23 This opens new possibilities for treating a wide range of diseases.24

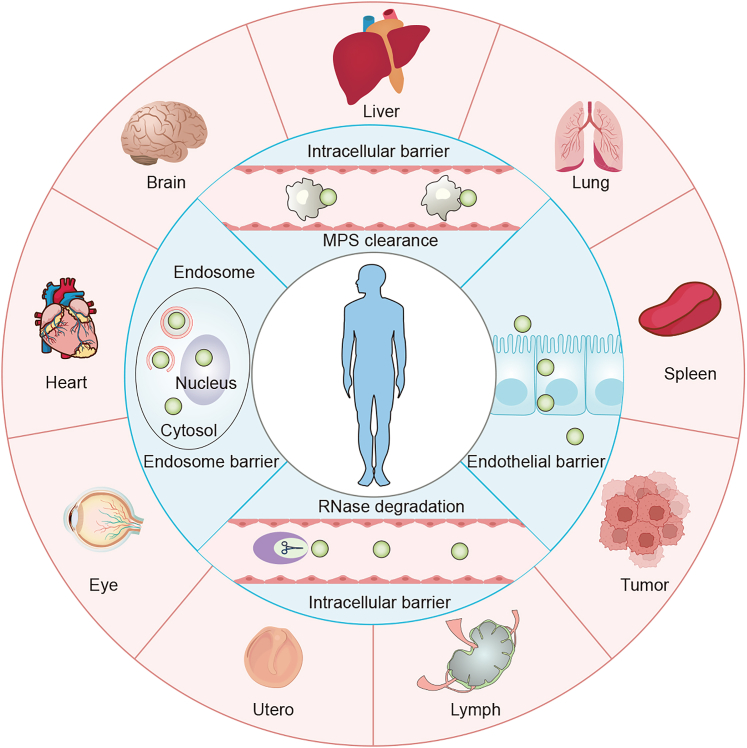

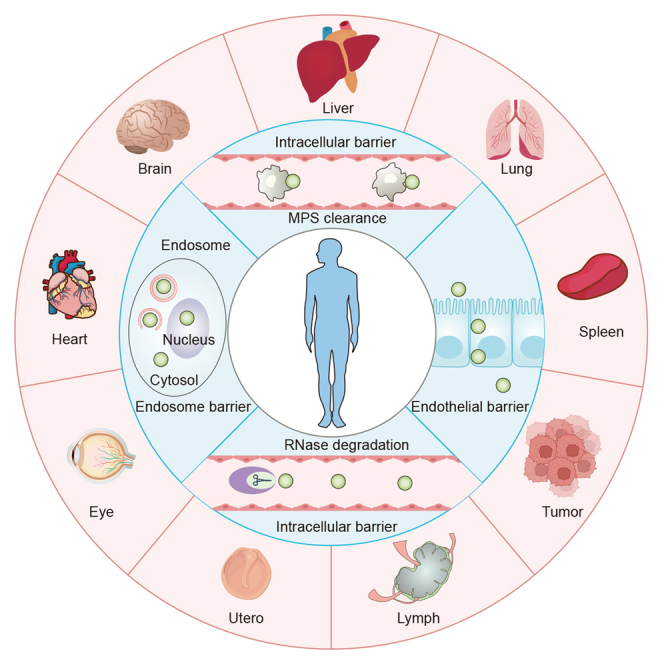

This review focuses on strategies for achieving organ-selective delivery of nucleic acid-based therapeutics using LNPs (Scheme 1). We introduce present research on specific in vivo delivery tactics for LNPs and highlight certain LNPs designed for organ-selective targeting. In addition, we discuss the general principles behind the design of organ-selective LNPs and delve into their delivery mechanisms. We hope to provide the latest progress in nucleic acid drugs-loaded organ-selective LNPs tactics and offer insights for researchers. We hope that this review will contribute to the understanding of nucleic acid-based therapeutics and inspire future directions in the field.

Scheme 1.

Nucleic acids delivery barriers and various LNPs-mediated organ-selective delivery strategies, including liver, lung, spleen, lymph, brain, heart, and others

MPS refers to the mononuclear phagocyte system.

Organ-selective LNPs as delivery platforms for nucleic acids

In recent years, nucleic acid drugs have shown a unique potential to convert previously “undruggable” targets into “druggable” ones for disease treatment. To overcome the challenges of poor in vivo stability and susceptibility to endogenous nucleases, LNPs are widely considered to be an ideal nucleic acid delivery system. However, the primary challenge associated with LNPs is their lack of targeting capabilities, leading to weak bioavailability of nucleic acid drugs and the potential for off-target effects, as well as in vivo toxicity. Therefore, developing strategies for enhancing LNPs’ ability to target diverse organs is of great clinical significance. On one hand, following systemic administration, LNPs interact with specific proteins and biomolecules in the bloodstream, forming a layer of adsorbed “protein corona” on their surface.25 The composition of this protein corona varies based on the type and properties of LNPs, including factors, such as composition, charge, size, surface chemistry, etc., predominantly affecting cellular uptake and biodistribution.26 On the other hand, LNPs modified with ligands (small molecules, peptides, antibodies, etc.) are widely employed as active targeting strategies. In this section, we summarize organ-targeted LNPs developed for nucleic acid delivery and discuss specific targeting strategies, providing readers with a contemporary overview of the development of targeted LNPs.

Liver-selective LNPs

As the largest digestive organ in the body, the liver plays a central role in metabolism, mainly performed by hepatocytes, one type of parenchymal cells, in which lesion of hepatocytes often causes serious metabolic diseases, such as Wilson disease, Gilben syndrome, etc. In addition, some hepatic non-parenchymal cells, such as liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSECs) and hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) also trigger serious hepatic diseases. For instance, LSECs play a key role in the initiation and progression of chronic liver diseases, cirrhosis, and even hepatocellular carcinoma development.27

Nucleic acid drugs offer unique advantages over conventional chemical and protein-based drugs and represent a new approach to treating liver diseases. Targeting hepatocytes is relatively straightforward because LNPs are naturally taken up by hepatocytes through the interaction of serum ApoE adsorbed on the LNPs’ surface and LDLR on the hepatocyte surfaces, facilitating cellular endocytosis.28 Consistent with the theory, unmodified LNPs have been found to be widely distributed in the liver after systemic administration.29 In addition, the hepatocellular targeting ability of LNPs can be significantly enhanced by optimizing lipid composition and LNPs formulation. For instance, a study by H. Lee and colleagues found that LNPs containing 1.5% PEGylated lipids exhibited approximately 80% transfection efficiency, the highest hepatocyte uptake, among LNPs formulations containing PEGylated lipids ranging from 1 to 3%.30 Also, it has been reported that by constructing helper lipids31 and ILs libraries, it was possible to identify mRNA/siRNA-LNPs with superior liver targeting and enrichment properties. James E. Dahlman’s group reported that LNPs containing stereopure 20α-hydroxycholesterol (20α) showed a more robust capacity to deliver mRNA to hepatocytes than control at a low dose.32 However, passive targeting mechanisms via LNPs may not be efficient for patients lacking LDLR. Given this, Andrew M. Bellinger utilized multivalent N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) to interact with highly expressed asialoglycoprotein receptor (ASGPR) on the hepatocytes, mediating an endogenous entry mechanism.33 An optimized GalNAc-modified LNPs formulated by ionizable lipid GL6 based on the lysine-based scaffold and covalently linked to the sugar moiety and scaffold exhibited significant adenine base editing capability targeting ANGPTL3 in the liver in a somatic LDLR-deficient nonhuman primates (NHP) model. The GalNAc-LNPs increased liver editing from 5% to 61% in the NHP model and resulted in an 89% reduction in ANGPTL3 protein in the blood for 6 months after administration.34 Besides, O-series LNPs (ILs containing an ester bond in the tail) have shown a preference for accomplishing liver-selective mRNA delivery.35 Qiaobing Xu’s team developed a novel O-series LNPs, 306-O12B LNPs, to perform a specific hepatocyte delivery of Cas9 (CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced palindromic repeats)-associated protein 9) mRNA and single guide RNA (sgRNA) targeting ANGPTL3 (sgAngptl3).36

In spite of the fact that the ability of LNPs to target hepatocytes has been widely explored, the targeted delivery of LNPs to other liver cells, such as HSCs, hepatic macrophages, Kupffer cells (KCs), and LSECs, remains a challenge. Fortunately, several studies have shown that strategies for targeting other hepatic cells with LNPs are possible. In the recent past, one approach, and also the most common one, has been the use of lipid library screening, which allows for the identification of structurally analogous targeting lipid candidates or the discovery of new structure-activity relationships. For example, a platform for mRNA delivery to activated hepatic stellate cells (aHSCs) was reported, from which a promising lipid candidate CL15A6 with high affinity to aHSCs was identified, and the biosafety with an in vivo dose up to 2 mg/kg was proven.37 In addition, Frederick Campbell and colleagues rationally designed an anionic LNP that switched neutral LNPs surface charge into anionic based on the formulation of Onpattro,38 which preferentially targeted mRNA delivery to the hepatic reticuloendothelial system (RES) made up of LSECs and KCs through scavenger receptors stabilin-1 and -2 mediating anionic recognition of LNPs with LSECs.39

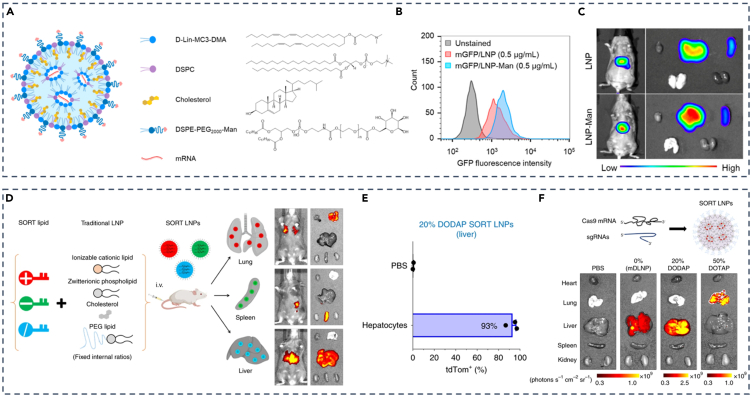

Selective targeting of liver cells by using ligand-modified LNPs is another potential strategy. Mannose-modified LNPs can achieve selective delivery of nucleic acids to LSECs through the mannose receptor, which is specifically expressed on LSECs.30,40 This strategy was employed by Andre E. Nel and his team, where they used mannose-modified DSPE-PEG2000 as the PEGylated lipid moiety of LNPs (Figure 1A), enabling LSEC-specific delivery of GFP mRNA at the cellular level (Figure 1B), and also enhancing in vivo lung gathering of man-LNPs with the dose of 1 mg/kg (Figure 1C).41

Figure 1.

Strategies for targeting LNPs to the liver

(A) Composition of LNPs, including mannose-modified lipid DSPE-PEG2000-Man.

(B) Assessment of GFP fluorescence intensity in LSECs following LNPs with/without mannose.

(C) In vivo and ex vivo GFP expression utilizing LNPs with/without mannose.

(D) SORT technology enables systematic and predictable engineering of LNPs for precise mRNA delivery into specific organs.

(E) Flow cytometry analysis (FACS) quantifying the percentage of tdTom+ cells within hepatocytes in the liver.

(F) Both mDLNP and SORT LNPs (20% DODAP) elicited specific fluorescence in the liver. (A–C) Adapted from permission.41 Copyright 2023, American Chemical Society. (D–F) Adapted from permission.42 Copyright 2020. Springer Nature.

Conventional LNPs mostly enrich the liver due to natural characteristics, making it difficult and necessary to target extra-hepatic tissue. Inspired by the four-component formula of classical LNPs, the selective organ-targeting (SORT) strategy, first reported by Daniel J. Siegwart’s group, has been reported, which involves the incorporation of a complementary component, known as the SORT molecule, in classical four-composition LNPs (Figure 1D).42 By fine-tuning the proportion and biophysical properties of this molecule, precise RNA-targeted delivery, tissue-specific gene delivery, and gene editing can be achieved. Using the SORT strategy, they developed liver-specific SORT LNPs (containing 20% 1,2-dioleoyloxy-3-(dimethylamino) propane (DODAP)) for both Cre recombinase mRNA (Cre mRNA) delivery to hepatocytes, which allowed activation of tdTom, a type of fluorescin, via Cre-mediated genetic deletion of the stop cassette in tdTom transgenic mice in approximately 93% hepatocytes (Figure 1E) and more enrichment of Cas9 mRNA and sgRNA in the liver at 0.1 mg/kg dose (Figure 1F).

Lung-selective LNPs

The human lung, a pivotal respiratory organ, is central to respiratory control, pulmonary circulation, and immune function. Lung diseases are a leading cause of mortality worldwide as well as a severe global public health issue, especially severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). According to a previous study, the population of patients with chronic respiratory diseases such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD), cystic fibrosis (CF), and lung cancer has been increasing rapidly.43 The delivery of nucleic acids with LNPs as ideal vectors for gene therapy offers the promise of a long-term cure for genetic diseases affecting the lung, such as CF and alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency.44 However, in contrast to the passive targeting of LNPs in the liver for disease cure, the development of lung-targeting LNPs confronts unique challenges such as low bioavailability and poor targeting.37 Fortunately, cationic helper lipids, typically (2,3-Dioleyl-propyl)-trimethylamine (DOTAP), have been identified as the preferred fifth lipid choice for specific pulmonary delivery of plasmid DNA (pDNA), siRNA, and antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs).42 Kevin V. Morris and colleagues simultaneously developed and screened two novel “stealth” LNPs (sLNPs), which were formulated to be steady in serum, circulate for a long time, and to protect siRNA payloads from nucleases unlike liposomes.45 One of them, called sLNP, containing 50% DOTAP and the other, dmLNP, containing 40% DOTAP and MC3, aimed to reducing biotoxicity, were both tailored for lung-specific siRNA therapy delivery as expected.

Similar to the liver-targeting strategy, numerous optimized lung-targeting LNPs have been identified by meticulously screening the lipids/LNPs libraries.46,47 It’s worth noting that, in contrast to liver-specific delivery with O-series LNPs, N-series LNPs (containing an amide bond in ionizable lipid tail) exhibit a tendency to preferentially deliver mRNA to the lungs via regulation of protein corona adsorbed on the surface of LNPs, followed by the observation that manifold types of pulmonary cells would be targeted by simply tuning head group structure of N-series LNPs. For example, 306-N16B LNP showed excellent pulmonary endothelium transfection ability, and 113-N16B LNP performed better pulmonary macrophages and epithelium delivery than the former. From the previous discussion, optimizing novel ionizable lipids is feasible for designing liver-targeting LNPs. Also, the SORT LNPs technology can achieve lung targeting. LNPs containing diverse classes of SORT molecules facilitate organ-specific targeting of SORT LNPs by binding to different subsets of plasma proteins.25 When Daniel J. Siegwart’s group first characterized SORT LNPs, they found that a modest increase in 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-ethylphosphocholine (EPC) or dimethyldioctadecylammonium (DDAB) in LNPs resulted in a gradual shift in luminescent activity from the liver to the lungs.42 Furthermore, they further identified 18:1RI (the trimethylammonium propane series) and 18:0 EPC (the ethylphosphocholine series), both purchased quaternary ammonium lipids, as the lead SORT molecules, from which 18:1 RI substitute one of the methyl groups found in the head group of 18:1 TAP (the quaternary ammonium lipid 1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane) as a SORT molecule, also referred to as DOTAP, with an ethanol group, for lung-specific mRNA delivery in their respective LNPs, selectively penetrating pulmonary endothelial cells and epithelial cells in deep lung tissues.48

Due to the direct connection between the lungs and the external environment through the airways, nebulized or inhaled LNPs present an exceptional and promising lung-targeted delivery strategy.46 The feasibility of this strategy primarily relies on several factors: (1) The low toxicity of LNPs to the respiratory tract49; (2) the nanoscale size of LNPs enables encapsulation in aerosolized droplets and deposition in the lungs50; and (3) the respiratory mucosal surface adhesion of LNPs.50 Experimental studies have revealed that intratracheal administration (i.t.) is an effective method for delivering LNPs to the lungs.51 In view of the potential of inhaled therapeutic LNPs for lung delivery, adopting leveraging lipid library screening tactics, Debadyuti Ghosh and colleagues employed a design of experiments (DOE) to screen LNPs with efficient mRNA lung delivery and identified F2, F8, F11, and F17 formulations as four leading LNPs for nebulized mRNA delivery to lungs at 1.5 μg mRNA dose.44 Then, they further screened and optimized ILs from the synthesized core lipids library to identify a key candidate named B-1, in which the novel LNPs with the core lipid B-1 was stably inhaled, readily expressed mRNA in the animal airways under a dose of only 750 ng mRNA which was lower than before, and, in details, showed in vivo selective transfection of lung epithelial cells compared to endothelial cells and immune cells.52

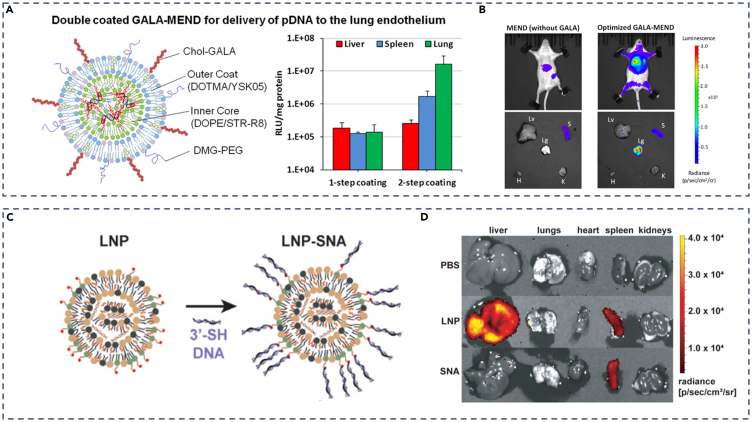

Apart from the aforementioned strategies, using specific binding between ligand and receptor to enhance targeting capacity is also crucial for developing lung-targeting LNPs. For example, as a synthetic peptide, GALA peptide can be used as a specific lung-targeting ligand by specifically binding to lectin receptors on the surface of pulmonary endothelial cells.53 Hideyoshi Harashima’s team modified LNPs with GALA peptide linked to cholesterol and applied a double-coating strategy, in which the outer coat and inner coat of LNPs are composed of (2,3-Dioleyl-propyl)-trimethylamine (DOTAM)/YSK05 which is newly synthesized in their laboratory and dioleoylphsophoethanolamine (DOPE)/stearyl-octaarginine (STR-R8), respectively, for pDNA package (Figure 2A). Results showed that 2-step coating tactics performed better in targeting lung endothelium cells than 1-step coating (Figure 2A) and that active targeting strategy with LNPs containing GALA peptide caused stronger luminescence in lungs than LNPs without that (Figure 2B).54 In addition, Jose Luis Santos and his team utilized monovalent αPV1 antibody-modified LNPs via Diels-Alder reaction, a robust conjugation method using a cyclopentadiene unnatural amino acid and maleimide chemistry, to create mRNA-delivered, lung-targeted LNPs by specifically binding to plasma membrane vesicle-associated protein (PV1) found in endothelial caveolae of lungs and kidneys using the antibody.55,56 This method of mRNA delivery by caveolae-associated proteins might have potential in treating diverse respiratory diseases such as CF.

Figure 2.

Strategies for lung and spleen-targeted LNPs delivery

(A) Double-coated GALA-MEND for pDNA delivery to lung endothelium.

(B) In vivo imaging of mice injected with MENDs (without GALA) or optimized GALA-MENDs (double-coated).

(C) Schematic representation of the transition from LNP to LNP-SNA.

(D) Spleen-specific mRNA expression comparison between LNP and LNP-SNA. (A and B) Adapted from permission.54 Copyright 2021, American Chemical Society.

(C and D) Adapted from permission.57 Copyright 2021, American Chemical Society.

Spleen-selective LNPs

The spleen, the largest secondary lymphoid organ, plays a crucial role in blood storage, hematopoiesis, clearance of senescent red blood cells, and immune response, which is particularly significant for vaccines. The spleen has a high density of antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and lymphocytes, such as B cells and T cells, making it an emerging target organ for vaccinations in the body.58 Also, the spleen has been considered to be an ideal targeting organ for immunotherapy owing to its role as the main organ for systemic immunomodulation.59 When it comes to LNPs-mediated nucleic acids delivery, their primary accumulation sites include the liver and spleen, with the spleen being the second most prominent site following intravenous (i.v.) administration,35 making spleen-targeting delivery of LNPs convenient, feasible, and of clinical transformation value. Fortunately, various strategies for developing spleen-targeted LNPs have been widely published, encompassing but not limited to.

-

(1)

Rational selection and optimization of helper lipids. A study showed that LNPs incorporating DSPC as helper lipids exhibited a pronounced propensity for spleen accumulation.60 LNPs with a high molar proportion of the helper lipid N-(hexadecanoyl)-sphing-4-enine-1-phosphocholine (egg sphingomyelin, ESM) significantly enhanced gene expression in the spleen, compared to mRNA-LNPs with a lower proportion of DSPC.61 Furthermore, the combination of DODAP and DOPE in LNPs has shown spleen specificity for successful pDNA delivery, targeting complement C3 receptors62

-

(2)

Synthesis and optimization of ILs. A report showed that the optimal LNPs formulation was identified through orthogonal optimization with the rational design and combinatorial synthesis of esterase-triggered decationizable quaternium lipid-like molecules (lipidoids).63 LNPs consisting of OF-Deg-Lin, an IL with a degradable bond, demonstrated competence in transfecting B lymphocytes, successfully delivering mRNA to the spleen at a dose of 0.75 mg/kg, which caused more than 85% protein expression of total protein.64 A novel IL, C4S18A, reported by Peng George Wang and colleagues, featuring bioreducible disulfide bonds, exhibited potent mRNA spleen targeting using intramuscular (i.m.) injection when preparing LNPs at a lower dose of 0.5 mg/kg.65 Additionally, LNPs containing F-L319, a novel IL with fluorinated alkyl chains, in combination with hydrocarbon L319 appropriately, displayed spleen-specific mRNA expression through intravenous (i.v.) injection66

-

(3)

Reasonable optimization of physicochemical properties of LNPs. For instance, Hideyoshi Harashima’s team utilized the DOE screening strategy for controlling particle size and eventually found that LNPs with a size range from 200 to 500 nm were appropriate for usage in targeting splenic dendritic cells (DCs).67 Likewise, Stefaan De Koker’s group also employed statistical DOE methodology to address the influence of lipid molar ratio and PEG-lipid chemistry on the T cell response and confirmed that LNP36 showed a shifted distribution toward the spleen compared with liver upon repeated injection in NHP68

-

(4)

Introduction of additional ingredients into LNPs. Incorporation of glycinate (GA) derivatives in the LNPs (GA-LNPs) rather than the strategy of targeting ligands resulted in preferential delivery of mRNA to immune cells such as antigen-presenting cells (APCs) in the spleen.69 Furthermore, mRNA-LNPs containing stearic acid as an additive, a well-studied compound in the realm of drug delivery,70 were found to selectively express mRNA in the spleen following intravenous injections.71 In addition, Daniel J. Siegwart and colleagues proved by SORT technology that anionic SORT lipids, specifically 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphate (sodium salt) (14PA) and sn-(3-oleoyl-2-hydroxy)-glycerol-1-phospho-sn-3’-(1′,2′-dioleoyl)-glycerol (ammonium salt) (18BMP), promoted the selective delivery of LNPs to the spleen, with 30% 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphate (18PA) SORT LNPs demonstrating spleen-targeting potential during trials42

Spleen targeting strategies by ligand-modified LNPs have also been reported. Studies have shown that modifying LNPs with CD3, CD4, and CD163 antibodies can lead to the accumulation of LNPs in the spleen.72 In addition, the development of spherical nucleic acids (SNAs) provides a novel concept for spleen-targeted LNPs. SNAs consist of spherical nanoparticles as the core, surrounded by oligonucleotides in a three-dimensional radial orientation. SNAs rely on scavenger receptors for enhanced DNA and RNA delivery.73,74 Chad A. Mirkin’s team took advantage of SNAs and utilized D-Lin-MC3-DMA as a core lipid to screen and optimize LNPs-SNA using DOE methodologies. SNA was formed by mixing LNPs containing PEG-maleimides with 3′-sulfhydryl-terminated DNA of 45 base pairs (bp) (Figure 2C). From in vivo experiments, it was found that intravenous injection of mRNA-loaded LNPs-SNAs with the dose of only 0.1 mg/kg mRNA, low-down concentration for animal administrations, resulted in a predominant expression of mRNA in the spleen, effectively bypassing the natural liver accumulation pattern observed with traditional LNPs (Figure 2D).57

Lymph node-selective LNPs

Lymph nodes (LNs), crucial components in tumor immunotherapy, are oval or bean-shaped lymphoid organs mainly consisting of lymphoid tissue and lymphatic sinuses for inducing immune responses, along with the spleen.75 Also, LNs are places where matured DCs process and present antigens to T cells with the assistance of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) Ⅰ and Ⅱ, migrate, and function in the LNs for immune response. Research reported that vaccines designed to target spleen-specific mRNA-LNPs have been found to induce mRNA expression in T cells within LNs.72 This implies a potential link between the spleen and LNs in immune responses, suggesting the importance of developing LNs-targeting LNPs as a significant approach to elicit immune responses, fortify defense against pathogen invasion, and treat certain diseases. LNPs for targeted nucleic acids delivery have thus far offered a versatile technological foundation for vaccine and immunotherapy development.76

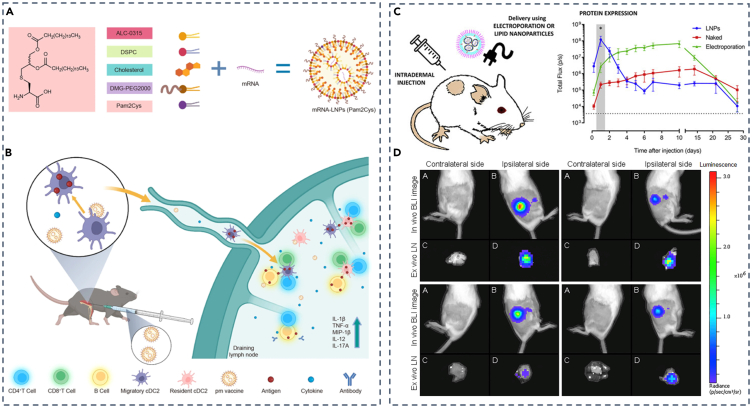

Studies have shown that LNPs’ targeting efficiency for LNs was influenced by factors such as particle size and charge.75 Also, the innovation of novel lipids held promise for enhancing the LNs-specific delivery of LNPs.77 Furthermore, the addition of adjuvant for LN-targeting tactics of LNPs has been demonstrated. For instance, Nghia P. Truong et al. reported that LNPs utilizing MC3 lipid incorporated with 3% Tween 20, a surfactant with a branched PEG chain linked to a short lipid tail, performed much stronger and specific transfection of pDNA at the LNs than those mixed with Tween 80.76 Also, Pam2Cys, a simple synthetic metabolizable lipoamino acid that signals through the Toll-like receptor (TLR) 2/6 pathway as a candidate adjuvant capable of eliciting an adaptive immune response,78,79 was incorporated by Huashan Shi and colleagues into the mRNA-LNPs vaccine (Figure 3A). Utilizing intramuscular administration, their findings demonstrated that Pam2Cys-LNPs (pm vaccine) resulted in an effective immune milieu in the draining lymph nodes (dLNs) through antigen presentation accomplished primarily by migratory and dLN-resident conventional type 2 DCs (cDC2s), which triggered both CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses, and induction of IL-12 and IL-17, among other cytokines in the mice model (Figure 3B).79

Figure 3.

Strategies for lymph node-targeted LNPs

(A) Preparation of Pam2Cys-incorporated mRNA vaccines.

(B) Mechanism of action for Pam2Cys-incorporated mRNA vaccines.

(C) Scheme of intradermal injection and protein expression of lipid nanoparticle.

(D) Intradermal injection of saRNA-LNP induces immune responses in the dLNs. (A and B) Adapted from permission.79 Copyright 2023, Springer Nature.

(C and D) Adapted from permission.80 Copyright 2019, Elsevier.

Apart from intramuscular injection of LNPs as a vaccine for targeting LNs, intradermal and subcutaneous injections also facilitate specific LNs delivery of LNPs. Niek N. Sanders and colleagues developed self-amplifying RNA (saRNA) that encodes nonstructural proteins (nsPs) of the Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus (VEEV).80 Unlike intramuscular administration, they adopted intradermal injection and found high and sustainable protein expression of LNPs (Figure 3C). Also, in vivo and ex vivo experiments indicated significantly high luciferase expression of positive LNs compared to the negative under the condition of a 5 μg dose (Figure 3D), underscoring the potential utility of saRNA-LNPs as a vaccine. Yasuo Yoshioka’s team developed CpG ODN-LNPs, in which CpG ODNs are short single-stranded synthetic DNA fragments containing immune-stimulating CpG motifs, known to play a pivotal role in viral immunity and various autoimmune diseases.81 After subcutaneous administration to mice, LNPs-CpGs constructed with different amounts of PEG-linked lipids displayed enhanced co-stimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86 expression on plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) in dLNs, promoting antiviral immune responses necessary for a vaccine against the virus.82

Brain-selective LNPs

The brain is the main part of the central nervous system in animals, performing motor, sensory, language, and emotional functions. Owing to the brain as the fundamental part of nervous system, the consequence will generally be serious if cerebral diseases occur. At present, the treatment of brain-related diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease (PD), brain cancer, stroke, and others faces substantial challenges.83 Although the emergence of nucleic acid drugs offers a promising avenue for addressing brain-related disorders, the existence of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) with the characteristic of high impermeability and selectivity of the many drugs and other therapeutic molecules poses a formidable challenge in nucleic acid drugs delivery of LNPs to the brain.84 Therefore, strategies for developing brain-targeting LNPs will be of great significance.

Fortunately, ligand-modified LNPs have shown potential for brain-targeted delivery via crossing of BBB. Angiopep, for instance, can interact with low-density lipoprotein receptor-associated protein-1 (LRP-1), which is extensively expressed on brain endothelial cells and potential glioblastomas (GBMs).85 Based on this, Thomas L Andresen’s team constructed PEGylated cleavable lipopeptide (PCL) and matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-sensitive LNPs, which were modified with angiopep as two-stage vectors for siRNA delivery to brain tumors.86 In the initial phase, angiopep facilitated efficient LNPs penetration into the BBB and uptake by GBMs through interaction with LRP-1.87 In the second phase, intracellular or extracellular cleavage of PCL dePEGylated LNPs and altered their surface charge from negative to positive, increasing uptake and endosomal escape. The successful uptake of LNPs by brain endothelial cells mediated by angiopep implies its potential to traverse the BBB. In addition to angiopep, T7 peptides have been reported to increase LNPs transport across the BBB,88,89 and Tat peptides could facilitate the transport of molecules across the BBB and increase cellular uptake.90 Moreover, Francisco Monroy’s research group employed mannosylated LNPs to target ASOs to brain border-associated macrophages (BAMs) by specifically binding to CD206 mannose receptors on the surface of macrophages.91,92

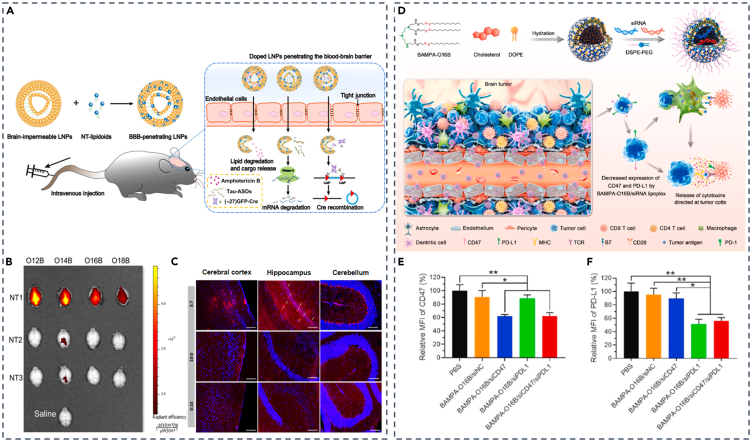

In response to the impermeable BBB, tactics with screening newly designed lipids and optimization of physicochemical properties, such as pKa, of LNPs have been demonstrated to be feasible. For instance, Qiaobing Xu and colleagues introduced a novel class of neurotransmitter (NT)-derived lipidoids (NT-lipidoids) to enhance brain-specific delivery.93 They synthesized a series of NT-lipidoids through Michael addition reaction between amines in NTs and alkyl acrylate, incorporating them into LNPs, transforming BBB-impermeable LNPs into BBB-penetrating LNPs (Figure 4A). The ex vivo experiments of fluorescence-labeled NT-LNPs showed that NT1-derived lipidoids exclusively could cross BBB (Figure 4B). By engineering NT1-LNPs, they observed substantial fluorescence signals of LNPs with the weight ratio of NT1-O14B and PBA-Q76-O16B fixed at 3:7 in various brain regions, including the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, and cerebellum in animal models (Figure 4C). Also, targeted delivery of LNP-siRNA for BBB crossing has been frequently reported.94,95 Liu and colleagues reported a novel quantitative LNP that identified the lipid BAMPA-O16B with the optimal pKa value around 6.5 and employed it as a carrier for delivering siRNA targeting CD47 and PD-L1 (Figure 4D). This approach efficiently delivered these two siRNAs across the BBB, resulting in the downregulation of CD47 and PD-L1 expression on the surface of GL261 tumor cells (Figures 4E and 4F).94 In addition, Huricha Baigude’s group employed a previously designed novel biocompatible peptide mimetic (DoGo) for systematic siRNA delivery.96 They used DoGo lipids to create DoGo LNPs and validated the efficiency of DOGO310 LNP for central nervous system (CNS)-targeted siRNA delivery.97

Figure 4.

Brain-targeting LNP strategies

(A) Schematic illustration of formulating NT-lipidoid-doped LNPs for cargo delivery into the brain.

(B) Representative ex vivo fluorescence images of the dissected brain 1 h after a single intravenous injection of DiR-labeled NT-LNPs (1 mg/kg).

(C) Fluorescence image of brain slices from Ai14 mice treated with (−27) GFP-Cre in various LNP formulations. Dual-modified LNPs for BBB penetration and GBM targeting.

(D) Schematic illustration of brain tumor immunotherapy mediated by BAMPA-O16B/siRNA lipoplex.

(E and F) Relative mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of CD47 and PD-L1 expression on the surface of GL261 tumor cells harvested from tumor-bearing mice. (A–C) Adapted from permission.93 Copyright 2020, American Association for the Advancement of Science. (D–F) Adapted from permission.94 Copyright 2022, Elsevier.

Heart-selective LNPs

As the central organ of vertebrates, the heart plays an essential role in the circulation of blood within the circulatory system of human beings. It promotes blood flow and supplies oxygen and various nutrients to organs, from which cells maintain normal metabolism and function. Cardiomyocytes, accounting for a large proportion of all cardiac cells, perform the function of not only contractile but also controlling the rhythmic activity of the heart. The abnormality of cardiomyocytes generally contributes to myocardiopathy and cardiopathy. Besides cardiomyocytes, there is still a large variety of cardiac cells, including fibroblasts, smooth muscle cells (SMC), endothelial cells, and immune cells, etc. Regrettably, LNPs have shown a limited cardiac targeting capability following systematic administration,98 and as of now, there are no cardiac-targeting SORT molecules reported using the current SORT LNPs technique. Therefore, there is a dire need to develop improved heart-targeting LNPs for nucleic acids therapies.

Cardiomyocyte is a crucial cell type that is considered hard to transfect and built on the dilemma of highly transfecting cardiomyocytes. Raymond Schiffelers’s team demonstrated the feasibility of LNPs in delivering highly stable and minimally immunogenic modified mRNA (modRNA) to the infarct area following myocardial infarction using an ischemia-reperfusion injury (IR) model.99 Based on previous studies, they employed the key lipid DLin-MC3-DMA and the Onpattro formulation,100 and carried out intravenous administration of LNPs encapsulating modRNA (Figure 5A). It was confirmed that the reperfusion of LNPs enabled high cellular modRNA uptake in the infarcted myocardium, particularly αSMA+ cardiac fibroblasts, in the IR model. Accordingly, accumulation of LNPs was observed in the ischemic regions of the heart after intravenous administration in the IR model, proved by high-performance expression of luciferase in the heart given a 50 μg luciferase mRNA dose (Figure 5B). In addition, Pedro Pires and colleagues demonstrated the potential of LNPs in delivering pDNA to cardiomyocytes through screening and optimizing lipid libraries.101 They created a mini-library of engineered LNPs and optimized the lipid ratio to eventually select LNP4, which exhibited the highest green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression in cardiomyocytes in vitro, superior heart transfection efficacy in vivo and reduced toxicity. They proposed that the formulation’s high DOPE and low cholesterol molar ratio in LNP4 may enhance nucleic acids delivery to myocardial cells both in vitro and in vivo.

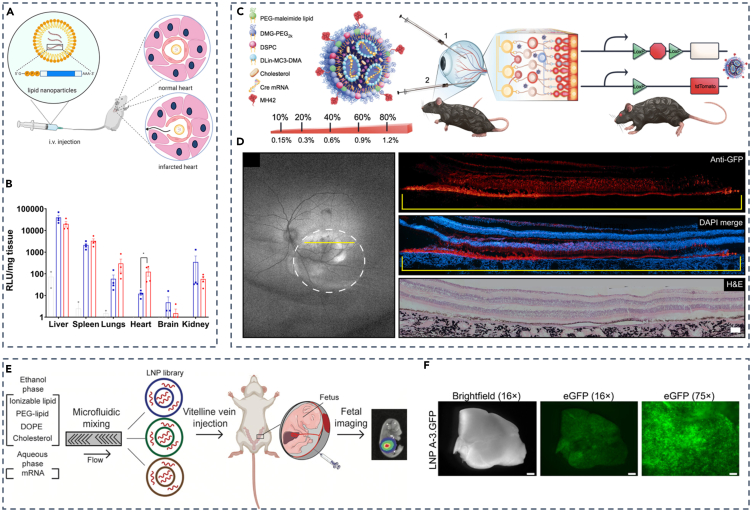

Figure 5.

Strategies for targeting LNPs to various organs, including the heart, eye, and utero

(A) Schematic of LNP Delivery of modified mRNA to damaged myocardium.

(B) Luciferase activity in various organ lysates 4 h after LNP-mRNA administration.

(C) Schematic of LNP and Cre mouse model, depicting both tested routes of administration.

(D) Expression of MH42-conjugated LNPs in the neural retina.

(E) Overview of LNPs for fetal delivery.

(F) GFP expression in fetal livers 24 h after injection with LNPs A-3.GFP. (A and B) Reproduced from permission.99 Copyright 2022, Elsevier.

(C and D) Reproduced from permission.102 Copyright 2023, American Association for the Advancement of Science.

(E and F) Reproduced from permission.103 Copyright 2021, American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Other organ-selective LNPs

In addition to the LNPs described previously, various other organ-selective LNPs have also been reported. As for the eyes, the visual organ of human beings, in which lesions of the eye such as glaucoma and cataracts may cause diminution of vision, blurred vision, or even blindness, nucleic acids-encapsulated LNPs may have difficulty overcoming ocular barriers to achieve a high transfection of neuronal cells critical for visual phototransduction, the photoreceptors (PRs).102,104 Gaurav Sahay and colleagues developed peptide-guided LNPs for targeted mRNA delivery to PRs in neural retina in rodents and NHP.102 Leveraging the ability of peptides to penetrate biological barriers and enhance LNPs targeting,105 they screened and optimized a diverse heptamer peptide library based on phage M13. Subsequently, these peptides were modified on the surface of LNPs, creating LNPs with varying peptide densities (Figure 5C). The optimized LNPs modified with MH42 peptide showed GFP expression within the margins of the bleb after subretinal delivery of 50 μg GFP mRNA, leading to a significant enhancement of GFP in PRs and RPE throughout the bleb (Figure 5D). Consequently, this approach exhibited substantial potential for clinical applications, particularly in the context of research related to hereditary retinal degeneration (IRDs).

Prenatal therapy, different from postnatal therapy, enables disease treatment in the early stages of irreversible pathology, significantly reducing disease morbidity and even mortality,106 which may indicate an important role in the future. So far, LNPs for in utero mRNA delivery have also been reported.103,107 For example, Michael J. Mitchell and his team screened libraries of ILs for LNPs preparation (Figure 5E). They found several LNPs from created libraries could be administered to the fetal liver, lung, and even intestines through a vitelline vein and then screened LNP A-3 as the top LNP for the highest eGFP mRNA delivery to the fetal liver among all candidates (Figure 5F). This strategy illustrates the feasibility of developing mRNA therapeutics via constant expression of target protein for prenatal disease treatment. Furthermore, based on their previous work, a novel LNP library was further screened, and then, a lead LNP A4 that effectively delivers mRNA selectively to placental trophoblast cells, endothelial cells, and immune cells was identified in vivo.

In addition, some representative cases indicating the type of disease, corresponding organ or cell, modification of IL, or targeting moiety are summarized in Table 1, and the specific cells present in different organs are beneficial for targeting through rational design.

Table 1.

Representative applications of LNPs-based nucleic acids organ-selective delivery

| Disease | Targeting Organ or Cell | Targeting Moiety | Overexpressed receptors | Chemical modification on LNPs | Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuropathy/Cardiomyopathy | Liver hepatocytes | GalNAc | Asialoglycoprotein receptor (ASGPR) | GalNAc-modified LNP formulated by ionizable lipid GL6 | The effect of GalNAc-LNP was even durable when assessed six months following dosing in wild-type NHPs in vivo.34 |

| Liver fibrosis | Liver hepatic stellate cells (aHSCs) | Ligand-free | Clathrin-mediated endocytosis through PDGFRβ receptors | Lipid CL15A6 | Transfected >80% of the aHSCs in vivo; a high degree of biosafety at doses as high as 2 mg/kg37 |

| / | Hepatic reticuloendothelial system (RES) | Ligand-free | Scavenger receptors stabilin-1 and -2 | DSPG-containing LNPs (srLNPs) | srLNPs yielded an approximately five-fold and an approximately three-fold targeting enhancement to murine LSECs and KCs, respectively39 |

| Peanut-induced anaphylaxis | LSECs | Mannose | Mannose receptor | Mannose-modified DSPE-PEG2000 | A promising approach for therapeutic intervention on allergic disorders and autoimmune disease41 |

| / | Lung endothelium | GALA peptide | Lectin receptors | GALA peptide linked on cholesterol; (2,3-Dioleyl-propyl)-trimethylamine (DOTAM)/YSK05 | Double-coated GALA-MEND shows selective pDNA delivery in the lungs54 |

| Cystic fibrosis/Lung cancer | Lung | PV1 antibody (Fab-C4) | Plasma membrane vesicle-associated protein (PV1) | Maleimide-bearing Dlin-MC3-DMA ionizable lipid | 40-fold improvement in protein expression in lungs compared with control LNPs55 |

| Cancers | Spleen | Oligonucleotides | Scavenger receptors | LNPs containing PEG-maleimides and D-Lin-MC3-DMA | Spleen-specific mRNA expression only in the G-rich (GGT × 7 -SH) LNP-SNA structures57 |

| Glioblastomas (GBMs) | GBMs, brain endothelial cells | Angiopep | Low-density lipoprotein receptor-associated protein-1 (LRP-1) | PEGylated cleavable lipopeptide (PCL) and matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-sensitive LNPs | Successful across of BBB and transfection of GBMs87 |

| Hereditary retinal degeneration (IRDs) | PRs | MH42 peptide | / | DSPE-PEG2000-maleimide–and DSPE-PEG2000-carboxy-NHS–functionalized LNPs | Robust protein expression was observed in the PRs, Müller glia, and retinal pigment epithelium (RPE)105 |

/, not available; MEND, multifunctional envelope-type nanodevice.

General principles for designing organ-selective LNPs

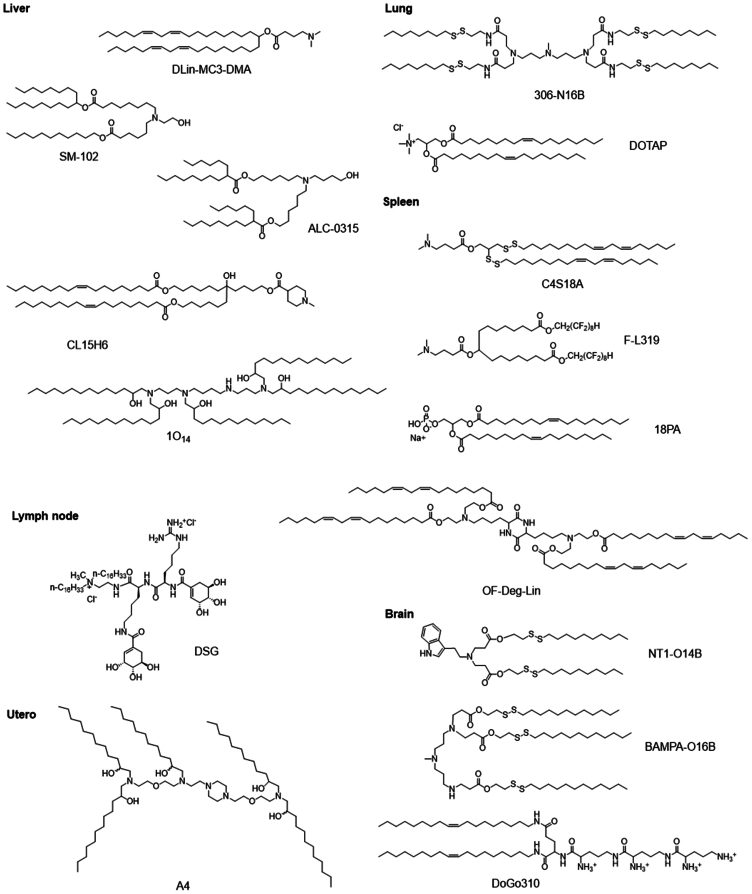

Chemical structures of key lipids

The design and selection of organ-targeted LNPs should primarily prioritize effectiveness, stability, and safety. This is achieved by adjusting their physicochemical properties, including charge, size, pKa, etc. Besides, fine variations in the IL structure within LNPs, rather than relying on charge or ligand modifications, alter the overall delivery characteristics and facilitate precise targeting of specific organs and cells.108 The structure of IL can be divided into three key components: head group, linker, and hydrophobic tail.

The head group of ILs typically carries a positive charge, which enhances the encapsulation of nucleic acids and promotes intracellular escape by improving interactions with negatively charged endosome membranes. Typical head groups include amines, ranging from primary to quaternary, guanidine, and various heterocyclic groups.109 It is worth noting that ILs with different head group structures often exhibit varying pKa values. These pKa values determine the surface charge of LNPs and subsequently impact their ability to interact with diverse types of serum proteins, leading to discrepancies in distribution within the body. Notably, studies by Moderna have claimed that LNPs with a pKa range of 6.6-6.9 contribute to the induction of adaptive immune responses in the context of mRNA vaccines. Additionally, an optimal pKa range of 6.2–6.8 has been identified for achieving effective protein expression in the liver following intravenous delivery of LNPs.110 Regarding organ-selective targeting, LNPs with a pKa range of 6–7 mainly accumulate in the liver. When the pKa exceeds 9, LNPs primarily reach the lungs, while LNPs with a pKa within 2–6 tend to accumulate in the spleen.42 A study by Dan Peer and colleagues demonstrated that LNPs with piperazine head key lipids exhibited a greater tendency to accumulate in the spleen than in the liver, whereas LNPs with tertiary amine head key lipids displayed a stronger preference for liver accumulation over the spleen.111 These results underscore the significant impact of headgroups on the biological distribution of LNPs, regardless of differences in surface potential. Furthermore, natural products also served as suitable delivery vehicles owing to their excellent biocompatibility. Dong’s group synthesized a series of vitamin lipids and, through meticulous screening and orthogonal optimization, obtained the optimal composition of vitamin C-based LNPs (VcLNPs) for efficient delivery of mRNA into macrophages.112

Linkers serve as intermediate bridges, enhancing the stability and degradation of LNPs. Their deliberate design reduces bio-related toxicity and improves transfection efficiency. Common types of linker groups include ether and ester, phosphoric acid or phosphonate ester, glycerol-type fragments, and peptides.113 It is highly desirable for the linker to be biodegradable while exhibiting robust circulatory stability in the biological environment. Dan Peer’s team utilized amino lipids containing hydrazine, hydroxylamine, or ethanolamine as the connecting main chain. Through a combination of different hydrophobic tails and linkers, they successfully generated a novel library of ILs, enabling the identification of macrophage-specific lipids.111

The choice of hydrophobic tail plays a critical role in determining the pKa, flowability, and lipophilicity of LNPs, which, in turn, impacts their stability and delivery efficacy.114 Studies have shown a correlation between various unsaturated and hydrophobic tail symmetries and the effectiveness and stability of LNPs.110 The typical range for tail lengths falls between 8 and 18 carbon units. Furthermore, incorporating multiple tails increases the cross-sectional area of the tail region, potentially forming a more conical structure and enhancing intracellular disruption (e.g., 98N12–5, C12-200, and cKK-E12).107 Notably, increasing tail unsaturation from 0 to 2 cis double bonds leads to a transition from a bilayer to a non-bilayer structure, causing membrane disruption and drug release (e.g., MC3 and OF-02).115 For instance, Siegwart and his team developed a library of 91 amino lipids by chemically synthesizing unsaturated mercaptans. Within this library, they identified a specific lipid known as 4A3-Cit, which showed superior endosomal escape capabilities compared to saturated lipids. In addition, the introduction of 4A3-Cit significantly improved mRNA delivery efficiency in vivo using the SORT technique, resulting in an 18-fold increase in protein expression in the liver compared to parental LNP.116

To decrease accumulation and potential side effects, tails containing ester or disulfide bonds improve the pharmacokinetic properties of ILs and reduce toxicity (e.g., L319304O13, OF-02, and OF-Deg-LIN).117 Qiaobing Xu’s group synthesized lipid libraries containing ester or amide bonds (O or N series) in tails and found that N-series LNPs were able to selectively deliver mRNA into mouse lungs. Furthermore, they discovered that simply adjusting the head group structure of N-series LNPs could target different lung cell types.35 It was found that N-series LNPs (with amide bonds at the tail) can selectively deliver mRNA to mouse lungs, while O-series LNPs (with ester bonds at the tail) tend to deliver mRNA to the liver via the library screening method.36 And the imidazole-based LNPs preferentially target mRNA to the spleen.118 By simply adjusting the head structure of N-series LNPs, different subpopulations of lung cells can be targeted. The doping LNPs with lipids containing quaternary ammonium groups can selectively deliver mRNA or CRISPR-Cas9 for specific lung diseases in the lungs.47 Similarly, both zwitterionic amino lipids and cationic quaternary sulfonamide amino lipids have permanent cationic quaternary ammonium functional groups and can also be used to design lung-targeted LNPs.25 The more detailed LNPs compositions for extrahepatic delivery are summarized by Dilliard S.A. and Siegwart D.J. 20 Furthermore, the length of the alkyl chain on the phosphate side determines organ selectivity. The iPhos with 9–12 and 13–16 carbon chain lengths deliver mRNA to the liver and the spleen, respectively.47 The possible underlying mechanism for only small difference in structure to cause such astonishing organ specificity may be the result of a specific protein or the synergistic action of several proteins, but further research is still needed. Once injected into the bloodstream, LNPs can selectively control the adsorption of specific plasma proteins, acting as targeted ligands to direct LNPs to selected organs. Taking O-series and N-series LNPs as an example, the first three proteins in the coronoid of 306-N16B LNPs are serum albumin, fibrinogen β chain, and fibrinogen gamma chain, among which fibrinogen encapsulation can improve endothelial cell adhesion and endothelalization, which may be the main reason for lung targeting. However, the highest enriched protein in 306-O12B LNPs corona is apolipoprotein E (ApoE), which is involved in lipid and cholesterol metabolism and mediates LNPs delivery to the liver. In addition, the zeta potential of the two LNPS did not differ significantly, and both showed a slightly negative surface charge, suggesting that surface charge may not be the only factor influencing the interaction between NPs and proteins in biological fluids.35

Overall, the ionization of lipid structure can be driven by the type of organs and cells. For example, the piperazine structure of lipids is used in a wide variety of immune cell groups to target mRNA transfer.119 Furthermore, organ-selective mRNA delivery is driven by tail structures containing ester or amide bonds (“O” or “ N” series).36 Macrophage cell type-specific lipids (Lipid 16) and high-quality lipids for liver targeting (Lipid 23) prove that the structure module can drive cell specificity.120 These studies hint at the possibility of ionized lipid structure-driven, more precise cell-type-specific mRNA delivery. However, it is difficult to predict lipid function based solely on lipid structure data.120 Usually relying on a large number of in vitro and in vivo screening tests, the current mainstream screening strategy is the use of high-throughput DNA barcoding developed by James Dahlman and his collaborators, which can simultaneously screen different customized LNPs quickly.121

The molecular chemical structure and SORT percentage can be customized to achieve organ-specific delivery by intravenous administration. Different chemical structures of SORT molecules may result in SORT LNPs with different surface chemical properties under the PEG layer. This may then affect the adsorption of protein corona to drive tissue-specific mRNA delivery.25 Related studies have shown that changes in the chemical structure of lipid alkyl tail and head groups affect the potency and specificity of mRNA delivery to the lungs. In addition, changes in chemical structure altered the amount and variety of protein corona components, transfected cell populations, and even tissue specificity in ways that correlated with organ-targeting outcomes. For example, liver SORT most avidly bound apolipoprotein E (ApoE), spleen SORT was most highly enriched in β2-glycoprotein I (β2-GPI), and lung SORT was most highly enriched in vitronectin (Vtn). ApoE, Vtn, and β2-GPI can drive endogenous targeting in the liver, lung, and spleen, respectively, with the receptor LDL-R highly expressed in the liver, the receptor αvβ3 integrin highly expressed in lung endothelial cells, and phosphatidyl serine, an anionic lipid found in aging red blood cells.25,48

In addition, SORT LNPs formulation also affects organ-specific mRNA delivery. For example, quaternium lipids, 1, 2-Dioleoyl-3-trimethylam-monium propane (DOTAP), with an increase in the molar percentage of DOTAP, promote the expression of luciferase proteins gradually from the liver (mDLNPs, 0% DOTAP) to the spleen (10–15% DOTAP) and then to the lungs (50% DOTAP).25 However, differences in the biological distribution of different formulations, as well as the general relationship between lipid structure and activity, remain to be fully understood.122 Targeting strategies designed using formulation optimization are often preferentially taken up by certain organs but rarely achieve high levels of target cell-specific expression.48 The representative chemical structures of key lipids or SORT molecules in LNPs, designed for organ-selective nucleic acids delivery, are illustrated in Figure 6. Representative examples indicating SORT LNPs with corresponding target organ or cell, key lipid, SORT molecules, formulation, and efficiency are shown in Table 2.

Figure 6.

Representative chemical structures of key lipids designed for organ-selective nucleic acids delivery

Table 2.

Targeting properties and other major characteristics of representative SORT-LNPs

| Target organ | Cell types | Key lipid/SORT molecular | Formulation: the active lipid/helper lipid/cholesterol/DMG-PEG/SORT molecular (mol %) | Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liver | Sinusoidal endothelial cell (SEC) | 5A2-SC8/DODAP | 5A2-SC8/DOPE/cholesterol/C14-PEG2K/DODAP = 19/19/38/4/20 | Liver-targeted SORT LNPs (20% DODAP) delivered Cre mRNA to ∼93% of all hepatocytes42 |

| Lung | Epithelial cells, endothelial cells, immune cells | 5A2-SC8/DOTAP | 5A2-SC8/DOPE/cholesterol/C14-PEG2K/DOTAP = 16.7:16.7:33.3:3.3: 30 | Lung-targeted SORT LNPs (50% DOTAP) transfected ∼40% of all epithelial cells, ∼65% of all endothelial cells and ∼20% of immune cells in the lungs42 |

| Lung | Basal cell | DOTAP40/DOTAP | 5A2-SC8/DOPE/cholesterol/PEG-DMG/DOTAP = 36/20/40/4/40 | Transfected ∼60% of NGFR+ basal cell populations after treatment123 |

| Lung | Endothelial cells; epithelial cells, immune cells | 5A2-SC8/18:1 TAP, 18:1 RI, or 18:0 EPC | 5A2-SC8/DOPE/cholesterol/C14-PEG2K/SORT molecules = 11.9/11.9/23.8/2.4/50 | 83% of the total luminescent flux produced in the lungs; endothelial cells were most efficiently transfected, followed by epithelial cells, then immune cells48 |

| Spleen | B cells, T cells, macrophages | 5A2-SC8/18PA | 5A2-SC8/DOPE/cholesterol/C14-PEG2K/18PA = 16.7:16.7:33.3:3.3: 30 | Spleen-targeted SORT LNPs (30% 18PA) transfected ∼12% of all B cells, ∼10% of all T cells, and ∼20% of all macrophages42 |

| Spleen | T cells | 5A2-SC8/18 : 1 PA LNPs | 5A2-SC8/DOPE/cholesterol/PEG-DMG/18:1PA = 15/15/30/3/7 | 5.8% of CD8+ T cells and 5.5% of CD4+ T cells were transfected124 |

| Spleen | / | 4A3-SC8/BMP | 4A3SC8/DOPE/cholesterol/DMG-PEG/BMP = 15: 15: 30: 3: 20 | LNP contained anionic BMP exhibited preference for spleen delivery over liver delivery125 |

| Lymph node | Antigen-presenting cells (APCs), including macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs) | 113-O12B | 113-O12B/cholesterol/helper lipid/DMG-PEG = 16: 4.8: 3: 2.4 | Positive mRNA expression in ∼27% DCs and ∼34% macrophages126 |

DODAP, ionizable cationic lipid 1,2-dioleoyl-3-dimethylammonium-propane; DOTAP (18:1 TAP), the permanently cationic SORT molecule 1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane; 18PA, negatively charged 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphate; 18:1 RI, the trimethylammonium propane (TAP) lipid series, which nearly shares the same chemical structure as 18:1 TAP but substitutes one of the methyl groups in the head group with an ethanol motif; 18:0 EPC, the ethylphosphocholine (EPC) series lipid; BMP: bis(monoacylglycerol)phosphate.

Optimizing components and modification of LNPs

In addition to altering the chemical structure of ILs, RNA-targeted delivery can also be controlled by adjusting the LNPs formulation and the proportion of lipid components.127 With variations in LNPs formulations, their size also undergoes corresponding changes. Efficient mRNA selective delivery can be achieved by rationally adjusting the size of LNPs. Studies have demonstrated that smaller LNPs are more likely to pass through the capillary walls than larger ones.128 Decreasing the size of LNPs for selective cell uptake can be achieved by increasing the concentration of PEGylated lipids or adjusting the flow rate.64 For mRNA vaccines, the typical size of LNPs is between 80 and 100 nm to induce uptake by APCs and promote antigen expression.129 Brito and colleagues reported a stronger positive correlation between LNPs smaller than 85 nm and the immunogenicity induced by mRNA vaccines in a mouse model, highlighting the importance of optimizing LNPs size for efficient mRNA delivery and vaccine efficacy.130 Moreover, adjusting lipid components and the proportion of RNA has enabled the successful delivery of intravenous vaccine nanoparticles to the spleen and lymphoid tissues containing DCs.131,132

Specific organ selection can also be achieved by attaching ligands (small molecules, peptides, antibodies, etc.) to the surface of LNPs, which can recognize and bind to specific receptors on the cell.51 The most common targeting method involves covalently linking antibodies to LNPs using various chemical methods. This includes amide crosslinking between carboxyl on LNPs and amino groups on the antibodies or connecting sulfhydryl groups on antibodies to maleimide groups on LNPs. These methods are employed to achieve the specific delivery of RNA to desired tissues and cell subpopulations. Unfortunately, the chemical coupling of antibodies can be inefficient, leading to LNPs heterogeneity and impaired antibody function.133 To address this issue, Li and colleagues covalently attached αPV1 antibody to the key lipid DLin-MC3-DMA, which specifically binds to plasma vesicle-associated protein (PV1) to achieve lung targeting. This system preferentially delivered mRNA to the lung and induced a 40-fold increase in protein expression.55

Delivery mechanisms of organ-selective LNPs in vivo

Controlling the distribution of LNPs is critical for the treatment of diseases occurring in specific organs. Apart from optimizing the intrinsic properties of LNPs, targeted delivery to extrahepatic areas can be regulated through various strategies, including the choice of administration routes, active targeting and passive targeting associated with the surface protein corona of LNPs.122

Local administrations, such as intradermal, intramuscular, intratracheal injections etc., prolong protein expression at the injection site. Intramuscular and subcutaneous injections of RNA-LNPs, the most common vaccination routes, effectively migrate to LNs through lymphatic vessels and induce stronger immune responses.134 Pulmonary deliveries, mainly including intratracheal, intranasal, and inhalation routes, allow LNPs to bypass pre-exposure to the systemic circulation before reaching the lung, thus avoiding liver metabolism and enhancing LNPs selective delivery to the lungs and LNs. Additionally, intraperitoneal administration, intravitreal, or subretinal injection provide personalized treatment options for pancreatic diseases such as cancer and diabetes, as well as genetic retinal degeneration.135 Overall, local drug delivery generally offers highly selective delivery of therapeutic agents to the disease site while minimizing systemic side effects. Notably, local administration is only suitable for diseases with known and accessible pathological sites, such as tumors or traumatic injuries.127

Commonly, active targeting of LNPs is achieved through specific recognition and binding between ligands modified on the surface of LNPs and receptors on the surface of the target cell. Similar to the challenges mentioned earlier in this review, while active targeting tactics enhance delivery efficiency and residence time of nucleic acids, progress in targeted delivery has been limited due to the personalized nature of this process, which is influenced by the heterogeneity of diseases.133

The passive targeting of LNPs can be mediated by the protein corona formed by non-specific adsorption on their outer surface.136 The adsorption of proteins is influenced by various physical properties of LNPs, including charge, composition, and size, among others. Changes in the surface properties of LNPs may compromise the stability of RNA-LNPs through corona.25 It has been demonstrated that by designing novel ionizable lipids (ILs) and optimizing LNPs formulations, the type of proteins adsorbed onto the LNPs surface can be influenced, thereby achieving organ-specific delivery.137 However, although targeting strategies designed via formulation optimization often result in preferential uptake by certain organs, achieving a high level of target cell specificity is rarely realized. Moreover, the roles of different formulations in differential biological distribution, as well as the general relationship between lipid structure, formulation, and activity, are areas that require further exploration.122

Proteins from plasma are adsorbed onto the LNPs surface to form a protein corona in the blood circulation. The protein corona formed on LNPs after intravenous injection contains hundreds of biomolecules (mainly proteins and lipids). LNPs are cleared and extravasated from the circulation, and ultimately function intracellularly via cellular uptake and undergo organ, cellular, and molecular biological processes.138 The composition of the protein corona is influenced by the chemical and molecular components of the surface of the LNPs, as well as its charge. This formation of protein coronas allows the fate of LNPs in vivo to be predicted, and even the targeting ligands can be shielded so that LNPs can be delivered less efficiently. Thus, understanding protein corona can help in the design of novel targeted LNPs.20

Usually, the formation of protein corona reduces the delivery efficiency of LNPs, and encapsulation of LNPs on the surface with PEG or other materials usually inhibits the formation of protein corona and prolongs the blood circulation of LNPs.139 Recent studies have shown that apolipoproteins can be incorporated into protein corona, exerting endogenous targeting properties and playing an important role in organ- and cell-specific targeting of LNPs.140 Understanding the components of LNPs and the nature of the protein coronas will be more useful in understanding the subsequent fate of LNPs in vivo and in designing organ-targeted LNPs for treating specific diseases.122

Since apolipoprotein E (ApoE) is involved in endogenous cholesterol transport, it binds to the low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDL-R) overexpressed in hepatocytes and enters the cell via receptor-mediated endocytosis. Thus, ApoE-rich protein corona can be used to target hepatocytes.141,142 Lung targeting of LNPs can be achieved by introducing sequences of lipid molecules that can alter the composition of the protein corona, and the unique protein corona formed promotes the interaction of LNPs with specific cellular receptors that are highly expressed in the lung.47 It has been shown that LNPs containing lipid molecules with quaternary ammonium head groups (SORT) can be applied to gene editing of endothelial, epithelial, and immune cells in the lung.47,48 In addition, lipid molecules characterized by cationic quaternary sulfonamide-amino lipids, amphoteric amino lipids, and doped amide bonds are also capable of delivering nucleic acids to the lungs in a better way.35,143 Targeting of lymphoid tissues can be achieved by adjusting the ratio of lipid molecules to form protein corona. Protein corona formation by LNPs combined with anionic phospholipids such as β2-glycoprotein I enables gene editing of B and T cells in the splenic region.42

For endogenous targeting, various novel technologies can be used to characterize the formation of protein coronas, identify the organ targeting results required for protein corona combinations, and associate them with nanoparticles, which is crucial for fully utilizing this targeting mechanism.144,145

Current clinical translation of organ-selective LNPs

Presently, RNA-LNPs therapies have received authorization from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), National Medical Products Administration of China, and the European Medicines Agency for the treatment of various conditions, such as hATTR-mediated amyloidosis, mRNA-LNPs based COVID-19 vaccines, namely SYS6006, BNT162b2, and mRNA-1273.122 Alnylam’s Patisiran (Onpattro), the first FDA-approved siRNA-LNPs, is composed of the IL DLin-MC3-DMA blended with DSPC, cholesterol, and DMG-PEG. It is employed to efficiently deliver hTTR siRNA to hepatocytes to treat hereditary thyroid transprotein amyloidosis.12 These four lipid components now serve as benchmarks for delivering siRNA141 and mRNA110 LNPs. DLin-MC3-DMA, the first FDA-approved IL for RNA-LNPs preparation, possesses a long liver tissue half-life,117 and demonstrates liver targeting following intravenous administration of MC3 LNPs. At present, clinical studies involving Patisiran are being widely conducted across the world, with some in the clinical observation phase (NCT04201418, NCT05040373 etc.), others in clinical phase I/II (NCT01617967, NCT05023889, NCT01617967, NCT05023889, etc.), and some having advanced to clinical phase III (NCT03862807, NCT02510261, NCT03997383 etc.). Besides, another liver-targeted lipid, LP-01, developed by Intellia, is also under clinical trials (NCT04601051, NCT05697861, and NCT05120830).

In addition to liver-selective LNPs for clinical development, there is growing interest in clinical interventions based on extrahepatic tissue-targeted LNPs. ReCode Therapeutics, a startup company utilizing SORT-LNPs technology, aims to break through the limitations of classical extrahepatic LNPs delivery and realize targeted delivery to specific organs.42 An inhaled mRNA therapeutic developed by ReCode Therapeutics for the treatment of CF is currently undergoing preclinical assessment. Additionally, another inhaled mRNA therapy for primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) is in phase I/II clinical trials (NCT05685186). Furthermore, ReCode Therapeutics is advancing drug development based on SORT LNPs technology for applications in CNS, liver, spleen, and oncology, and we provided the representative LNP-involved nucleic acids under clinical trials in Table 3.

Table 3.

Representative LNP formulated nucleic acids under the clinical trial stage

| Drug Name | NCT Number (Phase) | Sponsor | Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| RCT1100 | NCT05737485(1) | ReCode Therapeutics | Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia |

| RCT2100 | NCT06237335(1) | ReCode Therapeutics | Cystic Fibrosis (CF) |

| Patisiran |

NCT04201418(−) NCT05040373(−) NCT01617967(2) NCT05023889(1) NCT03862807(3) NCT02510261(3) NCT03997383(3) |

Alnylam Pharmaceuticals | Hereditary Transthyretin-mediated (ATTRv) Amyloidosis/Polyneuropathy Transthyretin (TTR)-mediated Amyloidosis Amyloidosis, Familial ATTR With Cardiomyopathy |

| CL-0059/CL-013 LNP | NCT05639894(1/2) | Sanofi Pasteur | Respiratory Syncytial Virus Immunization |

| DCR-MYC |

NCT02314052(1/2) NCT02110563(1) |

Dicerna Pharmaceuticals | Hepatocellular Carcinoma Multiple Myeloma Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma (NHL) Non-Hodgkins Lymphoma Primitive Neurotodermal Tumor (PNET) Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors Solid Tumor |

| MT-302 | NCT05969041(1) | Myeloid Therapeutics | Epithelial Tumors, Malignant |

| BNT111 | NCT04526899(2) | BioNTech SE | Melanoma Stage III/IV |

| BNT116 | NCT05142189(1) | BioNTech SE | Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) |

| BNT211 | NCT04503278(1/2) | BioNTech SE | Solid Tumor |

| BNT142 | NCT05262530(1/2) | BioNTech SE | Solid Tumor |

| mRNA-4359 | NCT05533697(1/2) | ModernaTX, Inc. | Advanced Solid Tumors |

| mRNA-4157 |

NCT03313778(1) NCT03897881(2) |

ModernaTX, Inc. | Solid Tumors |

| mRNA-2752 | NCT03739931(1/2) | ModernaTX, Inc. | Relapsed/Refractory Solid Tumor Malignancies or Lymphoma |

| TriMix | NCT03788083(1) | Universitair Ziekenhuis Brussel | Breast Cancer |

| OTX-2002 | NCT05497453(1/2) | Omega Therapeutics | Hepatocellular Cancer |

| mRNA-1944 | NCT03829384(1) | ModernaTX, Inc. | Prevention of Chikungunya Virus Infection |

| CV7202 | NCT03713086(1) | CureVac | Rabies |

| mRNA-1345 | NCT05127434(2/3) | ModernaTX, Inc. | Respiratory Syncytial Virus |

| mRNA-1647 | NCT05085366(3) | ModernaTX, Inc. | Cytomegalovirus Infection |

| mRNA-2752 | NCT03739931(1) | ModernaTX, Inc. | Relapsed/Refractory Solid Tumor Malignancies or Lymphoma |

| mRNA-5671/V941 | NCT03948763(1) | Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC | Carcinoma |

| MEDI1191 | NCT03946800(1) | MedImmune LLC | Solid Tumors |

| mRNA-2416 | NCT03323398(1/2) | ModernaTX, Inc. | Ovarian Cancer |

| Lipo-MERIT | NCT02410733(1) | BioNTech SE | Melanoma |

| BNT111 | NCT04526899(2) | BioNTech SE | Melanoma |

| BNT112 | NCT04382898(1/2) | BioNTech SE | Prostate Cancer |

| BNT113 | NCT04534205(2) | BioNTech SE | Metastatic Head and Neck Cancer |

| HARE-40 | NCT03418480(1/2) | University of Southampton | Neoplasm |

| RO7198457 | NCT03815058(2) | Genentech, Inc. | Advanced Melanoma |

| SAR441000 | NCT03871348(1) | Sanofi | Metastatic Neoplasm |

| NTLA-2001 |

NCT03688178(2) NCT05697861(−) |

Intellia Therapeutics | ATTR |

| NTLA-2002 |

NCT05120830(1/2) NCT06262399(−) |

Intellia Therapeutics | Hereditary Angioedema |

| ARCT-810 | NCT04442347(1) | Arcturus Therapeutics, Inc. | Ornithine Transcarbamylase Deficiency |

| mRNA-3705 | NCT04899310(1/2) | ModernaTX, Inc. | Methylmalonic Acidemia |

| mRNA-3927 | NCT04159103(1/2) | ModernaTX, Inc. | Propionic Acidemia |

| MRT5005 | NCT03375047(1/2) | Translate Bio, Inc. | CF |

“–” means status unknown.

Perspectives and conclusion

Perspectives

Currently, nucleic acids-based therapies are of immense clinical value due to their vast potential. LNPs have made significant progress in the field of targeted delivery of nucleic acids, but they also face certain challenges. Therefore, reasonable design of LNPs in the future will help overcome these difficulties.

-

(1)

Although LNP therapies generally exhibit lower immunogenicity compared to conventional chemotherapy and protein therapy, they are not immune to potential toxicity arising from the accumulation of LNPs in the liver and spleen. The presence of PEG chains in LNPs is beneficial in reducing toxic side effects and increasing their circulation time in vivo. Keeping a reasonable balance between the proportion of PEGylated lipids and PEG chain length in LNPs may mitigate their toxicity.

-

(2)

Traditional LNPs possess inherent passive targeting properties that predominantly guide them to hepatocytes, leading to accumulation in the liver and spleen. There is an urgent need to develop LNPs tailored to deliver nucleic acids to other organs. Screening and optimizing selective ILs or implementing chemical and biological modifications will enhance the targeting of specific organs. In addition, by exploring structure-activity relationships and chemical synthesis, more ILs for extrahepatic and extrasplenic targeting could be obtained.

-

(3)

The relationship between LNPs components and the types of protein corona formed on their surface needs to be further studied. Constructing and screening a predictable library is essential, validating the structure-activity relationship of lipids, and proteomics is anticipated to provide insights for the design of organ-selective LNPs.

-

(4)

The organ-selective delivery of LNPs faces the common challenge of being time-consuming and labor-intensive. The emerging use of DNA or mRNA barcodes holds the potential to enable high-throughput in vivo screening to address this issue.

-

(5)

The current pharmacokinetic studies of LNPs are not without flaws, and the use of LNPs may induce immune responses, which can limit their long-term usage. Continuous drug safety assessment and optimization are necessary to ensure the reliability and safety of LNPs in clinical applications.

Conclusion

Overall, this review extensively covers the contemporary developments of organ-selective LNPs for nucleic acids delivery. It encompasses recent advancements in targeted LNPs, the corresponding targeting strategies, mechanisms, and more. In addition, we highlight existing shortcomings in organ-targeted LNPs, including concerns related to immunogenicity, toxicity, suboptimal targeting tactics, and in vivo safety in clinical applications. We also offer suggestions to address these issues. In short, this review provides the latest insights into organ-selective LNPs for researchers in the field of nucleic acids pharmaceuticals. These insights lay a solid foundation for future research and innovation, opening up new possibilities for nucleic acids therapies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFA1201000, 2021YFE0106900, and 2021YFC2302400), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32001008, 32171394, 31901053, 32101157, 32101148, and 82202338), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2022CX01013, China), Beijing Nova Program from Beijing Municipal Science & Technology Commission (20220484207, China), and the project from China Biomedicine Park (Daxing Biomedical Industrial Base of Zhongguancun Science and Technology Park), and the project from Suzhou Biomedical Industrial Park (BioBAY). We thank the Biological and Medical Engineering Core Facilities, and Analysis & Testing Center, Beijing Institute of Technology, for supporting experimental equipment and staff for valuable technical help.

Author contributions

T.Z. and H.Y. wrote the manuscript and contributed equally. Y.L. and H.Y. play a pivotal role in the literature review. K.G. and N.A. aided in crafting the manuscript. Q.Y. contributed with his subject matter knowledge. X.D. assisted in figure preparation. J.Z. provided valuable insights into the discussion section. Y.W. reviewed and polished the manuscript. Y.H., Y.W., and X.-J.L. supervised the project, reviewed the manuscript, and provided financial support. Lead contact: Yuhua Weng (e-mail: wengyh@bit.edu.cn).

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Yuhua Weng, Email: wengyh@bit.edu.cn.

Yuanyu Huang, Email: yyhuang@bit.edu.cn.

Xing-Jie Liang, Email: liangxj@nanoctr.cn.

References

- 1.Sahin U., Karikó K., Türeci Ö. mRNA-based therapeutics — developing a new class of drugs. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2014;13:759–780. doi: 10.1038/nrd4278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu C., Shi Q., Huang X., Koo S., Kong N., Tao W. mRNA-based cancer therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2023;23:526–543. doi: 10.1038/s41568-023-00586-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang D., Wang G., Yu X., Wei T., Farbiak L., Johnson L.T., Taylor A.M., Xu J., Hong Y., Zhu H., Siegwart D.J. Enhancing CRISPR/Cas gene editing through modulating cellular mechanical properties for cancer therapy. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2022;17:777–787. doi: 10.1038/s41565-022-01122-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lampi M.C., Reinhart-King C.A. Targeting extracellular matrix stiffness to attenuate disease: From molecular mechanisms to clinical trials. Sci. Transl. Med. 2018;10 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aao0475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang X., Kong N., Zhang X., Cao Y., Langer R., Tao W. The landscape of mRNA nanomedicine. Nat. Med. 2022;28:2273–2287. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-02061-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guo S., Li K., Hu B., Li C., Zhang M., Hussain A., Wang X., Cheng Q., Yang F., Ge K., et al. Membrane-destabilizing ionizable lipid empowered imaging-guided siRNA delivery and cancer treatment. Explorations. 2021;1:35–49. doi: 10.1002/EXP.20210008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]