Abstract

Cell-to-cell communication through secreted Wnt ligands that bind to members of the Frizzled (Fzd) family of transmembrane receptors is critical for development and homeostasis. Although Wnts and Fzds exhibit substantial promiscuity, sometimes specific ligand-receptor pairings are required for their physiological functions. Wnt9a signals through Fzd9b, the coreceptor LRP5 or LRP6 (LRP5/6), and the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) to promote early proliferation of zebrafish and human hematopoietic stem cells during development. Our understanding of how Wnt9a-Fzd9b elicit specific physiological functions beyond the membrane are completely lacking. Here, we used fluorescently labeled, biologically active Wnt9a and Fzd9b fusion proteins to demonstrate that EGFR-dependent endocytosis of the Wnt9a-Fzd9b receptor complex was required for signaling. In human cells, the complex was rapidly endocytosed and trafficked through early and late endosomes, lysosomes, and the endoplasmic reticulum. Using small molecule inhibitors and genetic and knockdown approaches, we identified that Wnt9a-Fzd9b endocytosis required EGFR-mediated phosphorylation of the Fzd9b tail and depended on caveolin and the scaffolding protein EGFR protein substrate 15 (EPS15). LRP5/6 and the downstream signaling component AXIN were required for Wnt9a-Fzd9b signaling but not for endocytosis. Knockdown or loss of EPS15 impaired hematopoietic stem cell development in zebrafish. Specific modes of endocytosis and trafficking may represent one of the ways in which Wnt-Fzd specificity is established, because other Wnt ligands do not require endocytosis for signaling activity.

Introduction

Intercellular signaling is essential for the normal development and homeostasis of organismal life. Secreted signaling molecules direct neighboring cells to adopt different cellular fates, maintain pluripotency, and/or stimulate cellular behaviors. One vital class of cell signaling molecules are the highly conserved Wnt proteins, which elicit cellular signals that orchestrate a plethora of key biological processes, including cellular asymmetry, proliferation, tissue polarity and stem cell maintenance (1, 2).

Wnt signaling is generally separated into “canonical” and “noncanonical” pathways (1, 2); this study focuses on the canonical pathway, which is dependent upon the nuclear translocation of the transcriptional activator β−catenin. At the cell membrane, Wnt signals are generally initiated when one of many Wnt ligands interacts with one of several cell surface receptors. The Frizzled (Fzd) gene family encodes a class of seven-pass transmembrane receptors that can bind Wnt ligands through a C-terminal extracellular cysteine-rich domain (CRD) (3), as well as coreceptors such as those from the lipoprotein-rich protein (LRP) gene family. A large number of Wnt ligands (≥19) and Fzd receptors (≥10) are encoded in vertebrate genomes; however, the specificity of signaling interactions between Wnts and Fzds has only begun to be elucidated (4-7).

We previously identified an exquisitely specific pairing between Wnt9a and Fzd9b in zebrafish hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell (HSPC) development (8, 9). This pairing is also conserved in human cells (8-10). Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) is a required cofactor for this signal (8); however, we do not yet understand the molecular mechanisms downstream of this requirement.

One mechanism for differentially deciphering and propagating cell signals is through endocytosis and sorting. Generally, cargoes at the cell membrane are endocytosed through different pathways including those mediated by clathrin or caveolin, among others (11, 12). These nascent endosomes will fuse together and recruit endosomal proteins to become early endosomes. Following this, cargoes are either (1) sorted to late endosomes and late endosome multivesicular bodies (late endosome/MVB), or (2) exported to recycling endosomes to be transported back to the plasma membrane. From the late endosome/MVB, cargoes can be sorted to the lysosome for degradation, or to the Golgi apparatus for reuse at the membrane (13, 14). There is now a substantial body of evidence supporting a requirement for different endocytosis pathways for signal activation, sustaining a signal, or for differential signaling for many receptors (15-25). There are conflicting studies on the requirement(s) for endocytosis in Wnt signaling, possibly due to cell- and receptor/ligand- dependent contexts for downstream signals (26-38).

We developed fluorescently tagged Wnt and Fzd molecules expressed in CHO and HEK293T cells, respectively. These tagged proteins were expressed, properly trafficked, and biologically active. Using this platform, we observed that complexes containing both Wnt9a and Fzd9b (hereafter Wnt9a-Fzd9b) were internalized within one minute of treatment with Wnt9a. Small molecule inhibition of endosome scission abrogated the Wnt9a-Fzd9b–dependent β-catenin signal, whereas inhibition of lysosomal degradation increased this signal, suggesting that Wnt9a-Fzd9b signals from endosomes. Mechanistically, this internalization event required EGFR tyrosine phosphorylation of Fzd9b; mutation of Fzd9b to eliminate the EGFR phosphorylation site that we previously identified (8) also eliminated internalization of the Wnt9a-Fzd9b complex. Internalization of the receptor complex required caveolin-mediated endocytosis and the scaffolding protein EGFR protein substrate 15 (EPS15) (39-43). We also observed that Wnt9a-Fzd9b signaling depended on EPS15, which we also confirmed in the physiological context of HSPC development. Finally, we found that the EH (Eps homology) domains of EPS15 as well as the EGFR phosphorylation site at Tyr850 are all required for Wnt9a-Fzd9b signaling (41, 44).

Results

Fluorescently tagged Wnt9a and Fzd9b proteins retain signaling activity

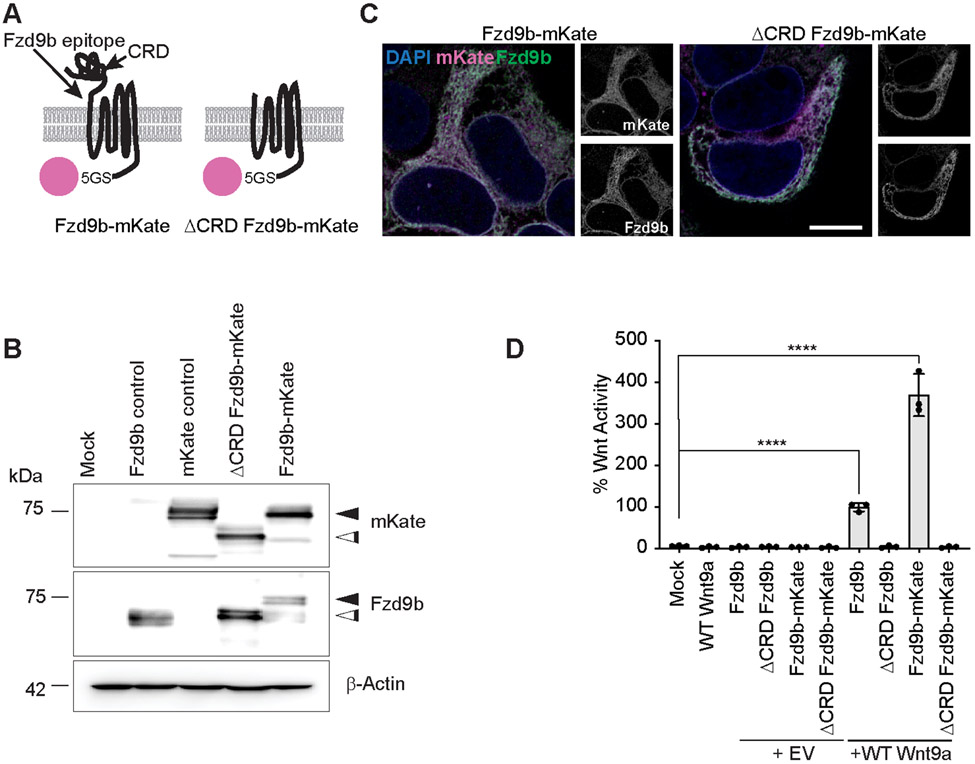

There are conflicting reports on the importance of endocytosis for Wnt signaling for various Wnt-Fzd pairings (26-38). To investigate how Fzd9b responds to its cognate ligand, Wnt9a, we generated constructs expressing either Fzd9b or Fzd9b lacking the ligand-binding cysteine rich domain (CRD), fused to a 5(GS) linker sequence and either the red fluorescent protein mKate2, or a V5 tag, (hereafter Fzd9b-mKate, Fzd9b-V5, ΔCRD Fzd9b-mKate or ΔCRD Fzd9b-V5, Fig. 1A, Supplementary Fig. 1A). The mKate fusion proteins were stably expressed under regulatory control of a cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter in HEK293 cells, and were detected by immunoblotting at the anticipated sizes using either our previously described Fzd9b antibody (8) or an mKate antibody (Fig. 1B). Using confocal microscopy and immunofluorescence, we saw strong overlap between the N-terminal Fzd9b antibody staining, and the C-terminal mKate fluorescent reporter (Fig. 1C). Results were the same with a V5 antibody (Supplementary Fig. 1B), indicating that mKate or V5 can be used as a surrogate reporter of Fzd9b localization in the cell. Wnt signaling through β-catenin can be measured using a luciferase-based reporter assay called Super TOP (TCF-optimal promoter) Flash (45). We found that tagging Fzd9b with either mKate or V5 did not impair its signaling ability, and that as anticipated, ΔCRD Fzd9b fusion proteins did not display any signaling ability (Fig. 1D, Supplementary Fig. 1C). Finally, we tested that these fusion proteins were correctly trafficked to the cell membrane using non-permeabilized immunofluorescence with our extracellular Fzd9b antibody and found that Fzd9b fusion proteins were correctly trafficked to the cell surface (Supplementary Fig. 1D-E).

Fig. 1. Fluorescently tagged Fzd receptors retain signaling capacity.

(A) Schematic of Fzd9b-mKate and ΔCRD Fzd9b-mKate constructs. (B) Representative immunoblotting for mKate and Fzd9b in transgenic HEK293T cell lines mock-transfected or stably expressing Fzd9b, mKate, or the indicated Fzd9b-mKate constructs. White arrowhead indicates the predicted size of WT Fzd9b; black arrowhead indicates the expected size of the mKate fusion protein. β-Actin is a loading control. Blots are representative of N = 3 independent experiments. (C) Representative confocal z-stacks of transgenic lines as indicated. Scale bar is 10 μm. Images are representative of N = 3 independent experiments. (D) Super TOP Flash assays to measure Wnt responses in HEK293 cells transfected with Fzd9b, Fzd9b-mKate fusion proteins, and Wnt9a as indicated. All data presented are from N=3 biological replicates, with different experiments conducted on different days a total of 3 times with similar results. EV- empty vector, ****P<0.0001 by ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc comparison compared to mock.

A Gamillus-tagged Wnt9a protein retains biological activity

There are only a handful of previously successful instances of generating functional Wnt proteins tagged with fluorescent proteins (46-51), likely due to their hydrophobic nature, which is a requirement for their signaling activity. We began by generating versions of Wnt9a tagged with a 5(GS) linker fused to either FLAG or Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) at the N-terminus between L58 and C59, or at the C-terminus, just before the stop codon (hereafter FLAG-Wnt9a, GFP-Wnt9a or Wnt9a-GFP, Supplementary Fig. 2A), under regulatory control of a doxycycline inducible promoter system. We generated stable transgenic cell lines in CHO cells and found that all three of these fusion proteins were expressed and secreted; however, both GFP-tagged Wnt9a proteins showed some degree of presumed cleavage (Supplementary Fig. 2B). Conditioned medium from FLAG-Wnt9a or Wnt9a-GFP were able to induce Super TOP Flash activity with Fzd9b, suggesting that these tagged versions of Wnt9a were biologically active (Supplementary Fig. 2C). On the other hand, GFP-Wnt9a did not induce Super TOP Flash reporter activity (Supplementary Fig. 2C), indicating that the N-terminal GFP fusion protein was not able to induce a β-catenin dependent Wnt signal.

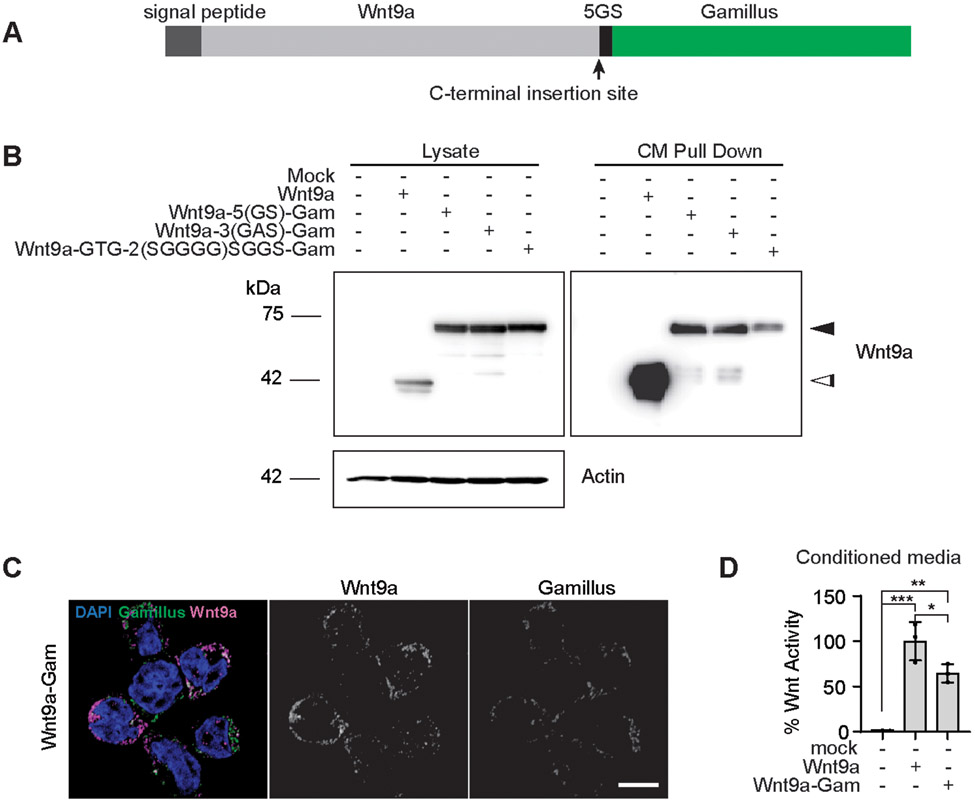

As cargoes are endocytosed, they are acidified through the endosome-lysosome pathway, which abolishes the fluorescent output of some fluorophores like GFP, but not Gamillus, another fluorescent protein in the green range (52). To monitor Wnt9a as it is endocytosed, we derived C-terminally tagged Wnt9a constructs fused with either 5(GS), 3(GAS) or GTG-2(SGGGG)SGGS linker sequences and Gamillus (Fig. 2A). Although all three of these fusions were expressed and secreted from CHO cells, we observed putative cleavage of the 5(GS) and 3(GAS) fusion proteins (Fig. 2B). The Wnt9a-GTG-2(SGGGG)SGGS-Gamillus (hereafter Wnt9a-Gam) remained intact (Fig. 2B), and so we chose to pursue this as our reporter of Wnt9a localization. Immunofluorescent staining of Wnt9a-Gam CHO cells showed colocalization of the Wnt9a antibody that we previously derived (10) and the Gamillus fluorescent signal (Fig. 2C). We also observed overlapping labeling of FLAG and Wnt9a in FLAG-Wnt9a CHO cells (Supplementary Fig. 2D). Treating Fzd9b-mKate Super TOP Flash reporter cells with Wnt9a-Gam conditioned medium showed nearly wild-type amounts of Super TOP Flash activity, indicating that this fusion protein was biologically active (Fig. 2D). Taken altogether, these data indicated that Wnt9a-Gam can be used to visualize Wnt9a.

Fig. 2. A Wnt9a fusion protein is biologically active.

(A) Schematic of Wnt9a-Gam construct. (B) Representative immunoblots for Wnt9a and β-Actin; cell lysates and conditioned media (CM) before and after Wnt9a pulldown are shown for transgenic CHO cell lines as indicated. Black arrowhead indicated anticipated size for Wnt9a fused to Gam; white arrowhead indicates anticipated size of untagged Wnt9a. Data are representative of N = 3 independent experiments. (C) Representative confocal z-stacks of immunofluorescence on transgenic lines as shown. Scale bar is 10 μm. Data are representative of N = 3 independent experiments. (D) Super TOP Flash assays conducted in HEK293 cells stably expressing Fzd9b-mKate and Super TOP Flash and induced with CM from transgenic CHO lines expressing Wnt9a or Wnt9a-Gam. All data presented are from N=3 biological replicates, with different experiments conducted on different days a total of 3 times with similar results. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 by ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison post-hoc test.

The Wnt9a-Fzd9b complex is rapidly endocytosed

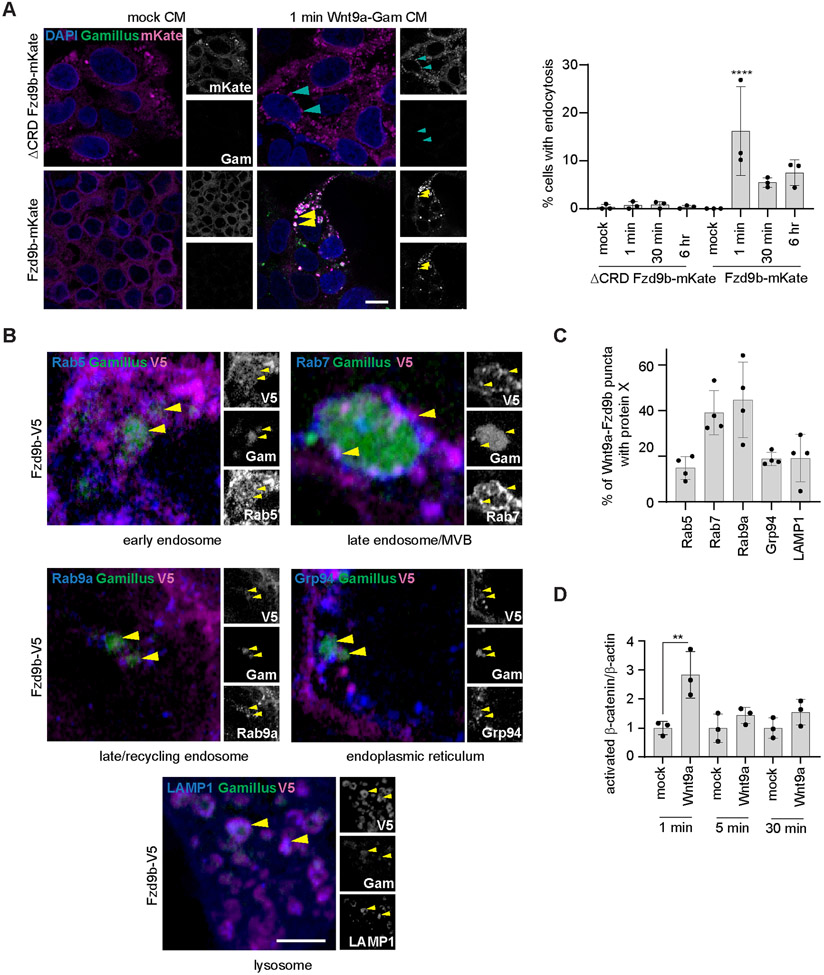

Endocytosis is a common mechanism of signal regulation for a variety of cell signaling cascades, and some receptor complexes require endocytosis to initiate different downstream signals (53-58). To assess if the Wnt9a-Fzd9b complex underwent endocytosis, we treated Fzd9b-mKate or ΔCRD Fzd9b-mKate cells with conditioned medium collected from either naïve CHO (mock CM) or Wnt9a-Gam CHO (Wnt9a-Gam CM) cells and fixed the cells after several timepoints for analysis by confocal microscopy. A small slice through the center of the Fzd9b-mKate cells indicated that, in response to Wnt9a-Gam CM treatment, there was rapid internalization (as early as 15 seconds and most robustly at 1 minute) of colocalized Wnt9a and Fzd9b (Fig. 3A), a finding we recapitulated using Wnt9a-GFP (Supplementary Fig. 3A). We occasionally detected very small Wnt9a-Fzd9b complexes in later timepoints such as 6 hours post treatment (Fig. 3A). On the other hand, although ΔCRD Fzd9b-mKate cells had multiple Fzd9b puncta on the inside of the cell, none of these we colocalized with Wnt9a (Fig. 3A), indicating that the Fzd9b CRD was required for Wnt9a internalization.

Fig. 3. The Wnt9a-Fzd9b complex is rapidly endocytosed.

(A) Representative confocal z-stacks of ΔCRD Fzd9b-mKate or Fzd9b-mKate cell lines treated with either mock CM or Wnt9a-Gam CM and fixed at timepoints indicated. Quantification of cells with internalized Wnt9a-Gam events on the right. Yellow arrows indicate Wnt9a-Fzd9b complexes; cyan arrows indicate Fzd9b without Wnt9a. Scale bar is 10 μm. Images are representative of N = 3 independent experiments. Data presented are from N=3 biological replicates. (B) Representative confocal z-stacks of immunofluorescence on Fzd9b-V5 cells treated for one minute with Wnt9a-Gam CM. Scale bars are 2.5 μm. Images are representative of N = 3 independent experiments. (C) Quantification of co-occurrences of markers denoted in Wnt9a-Fzd9b puncta. Data are representative of N = 4 independent experiments. (D). Quantification of immunoblots for active β-catenin (using an antibody targeted to non-phosphorylated β-catenin) in HEK293 Fzd9b-mKate cells treated with mock CM or Wnt9a-Gam CM for 1, 5 or 30 minutes. Data is from N=3 biological replicates; data was reproduced with similar results on 3 different days. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 by ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc comparison.

Passage through the endosomal trafficking pathway leads to the interaction of cargoes with various Rab GTPases that mark subcellular structures throughout the cell. By co-staining Fzd9b-V5 cells treated with Wnt9a-Gam CM, we were able to detect Wnt9a-Fzd9b complexes in the early endosome (Rab5), late endosome/multi-vesicular body (Rab7), late or recycling endosome (Rab9a), endoplasmic reticulum (Grp94), and lysosome (LAMP1) (Fig. 3B-C), indicating that Wnt9a-Fzd9b complexes were rapidly endocytosed and trafficked throughout the cell.

There are many mechanisms through which cells uptake cargoes, including clathrin- and caveolin-mediated endocytosis (59). To determine if endocytosis was required for Wnt9a-Fzd9b signaling, we used the small molecule inhibitors, PitStop2 and Dynasore, which inhibit both clathrin-dependent and clathrin-independent endocytosis (60, 61). We found that these inhibited Wnt9a-Fzd9b-dependent Super TOP Flash reporter activity in a concentration- and Wnt-dependent manner (Supplementary Fig. 3B-C), suggesting that Wnt9a-Fzd9b endocytosis was required for Wnt signaling. Once cargoes are endocytosed, they are sorted to various intracellular destinations, including to the lysosome (Fig. 3B). Using Bafilomycin A1, an inhibitor of the V-ATPases critical for lysosomal degradation, we observed a concentration-dependent increase in Wnt9a-Fzd9b Super TOP Flash activity (Supplementary Fig. 3D). These data were supported by knocking down ATP6V1C2, one of the V-ATPases required for lysosomal degradation, using siRNA in Fzd9b Super TOP Flash cells, which leads to an increase in Wnt9a-Fzd9b-driven Super TOP Flash activity (Supplementary Fig. 3E-F). Taken together with the observation that internalization is required for signaling activity, these results suggested that the Wnt9a-Fzd9b receptor complex signaled from endosomes.

In β-catenin dependent signaling, once a Wnt ligand interacts with its cognate receptor, Fzd, the β-catenin destruction complex is dissociated, allowing non-phosphorylated (active) β-catenin to enter the nucleus and activate target gene expression (62, 63). The observation of rapid endocytosis of the Wnt9a-Fzd9b complex, paired with the requirement for endocytosis in initiating signaling suggested that there should be very early activation of β-catenin in response to Wnt9a, which we observed within 1-5 minutes of Wnt9a treatment (Fig. 3D, Supplementary Fig. 3G). Altogether, these results indicated that Wnt9a-Fzd9b was rapidly endocytosed, and that this was a prerequisite for β-catenin dependent signaling.

Caveolin-dependent endocytosis is required for Wnt9a-Fzd9b signaling

We had previously observed that key components of the AP-2 complex, which is essential for clathrin-mediated endocytosis, are recruited to Fzd9b in response to Wnt9a (8). To test the requirement of clathrin-mediated endocytosis in Wnt9a-Fzd9b signaling, we used siRNA targeting the clathrin heavy chain (CLTC) in Fzd9b Super TOP Flash cells, and tested Super TOP Flash activity in response to Wnt9a. Whereas we observed approximately 92% knockdown of CLTC protein (Supplementary Fig. 4A), there was no effect on Wnt9a-Fzd9b Super TOP Flash activity (Supplementary Fig. 4B). This was not due to residual CLTC protein, because the prototypical clathrin cargo Transferrin was not endocytosed under knockdown conditions (Supplementary Fig. 4C), and we verified this finding with a second siRNA (Supplementary Fig. 4D), altogether indicating that clathrin heavy chain was not required for Wnt9a-Fzd9b signaling.

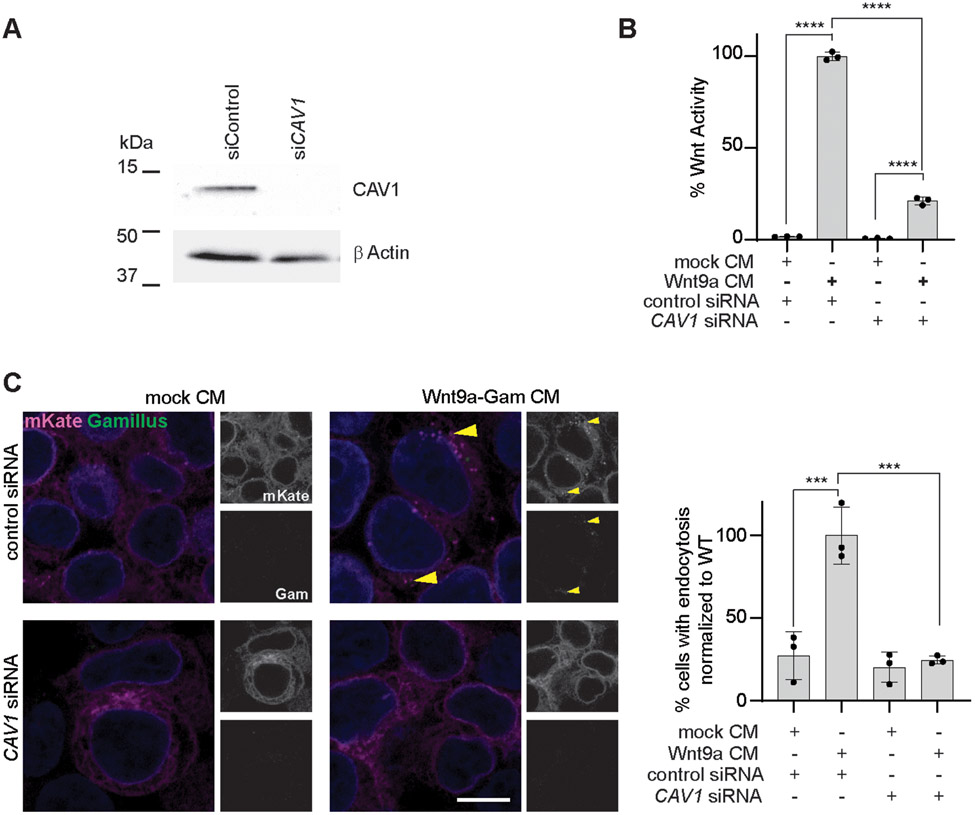

To determine if caveolin-mediated endocytosis may mediate Wnt9a-Fzd9b endocytosis, we used an siRNA targeting Caveolin (CAV1), an essential component of caveolin pits, and found that in the context of undetectable amounts of CAV1 protein (Fig. 4A), the Wnt9a-Fzd9b signal was severely compromised (Fig. 4B, Supplementary Fig. 4D). To determine if CAV1 impacts Wnt9a-Fzd9b endocytosis, we treated Fzd9b-mKate cells with either mock CM or Wnt9a-Gam CM in the context of either control or CAV1 siRNAs and examined cells at 1 minute post CM treatment. Using this approach, we found that in the absence of CAV1, Wnt9a-Fzd9b endocytosis was severely compromised (Fig. 4C), indicating that the Wnt9a-Fzd9b complex was internalized through caveolin-mediated endocytosis.

Fig. 4. Caveolin-dependent endocytosis is required for Wnt9a-Fzd9b signaling.

(A) Representative immunoblot of Fzd9b-mKate cells treated with either control or CAV1 siRNAs. Blots are representative of N = 3 independent experiments. (B) Super TOP Flash assays conducted in HEK293 cells stably expressing Fzd9b-mKate and Super TOP Flash, treated with either control or CAV1 siRNA, and induced with either mock or Wnt9a CM. Data presented are from N=3 biological replicates, with different experiments conducted on different days a total of 3 times with similar results. (C) Representative confocal z-stacks of Fzd9b-mKate cells treated with either control or CAV1 siRNA, induced with either mock CM or Wnt9a-Gam CM, and fixed after one minute. Data presented are from N=3 biological replicates, with different experiments conducted on different days a total of 3 times with similar results. Scale bar is 10 μm, endocytosis events are quantified on the right. ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001 by ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc comparison.

LRP and AXIN are required for Wnt9a-Fzd9b signaling, but not for Wnt9a-Fzd9b endocytosis

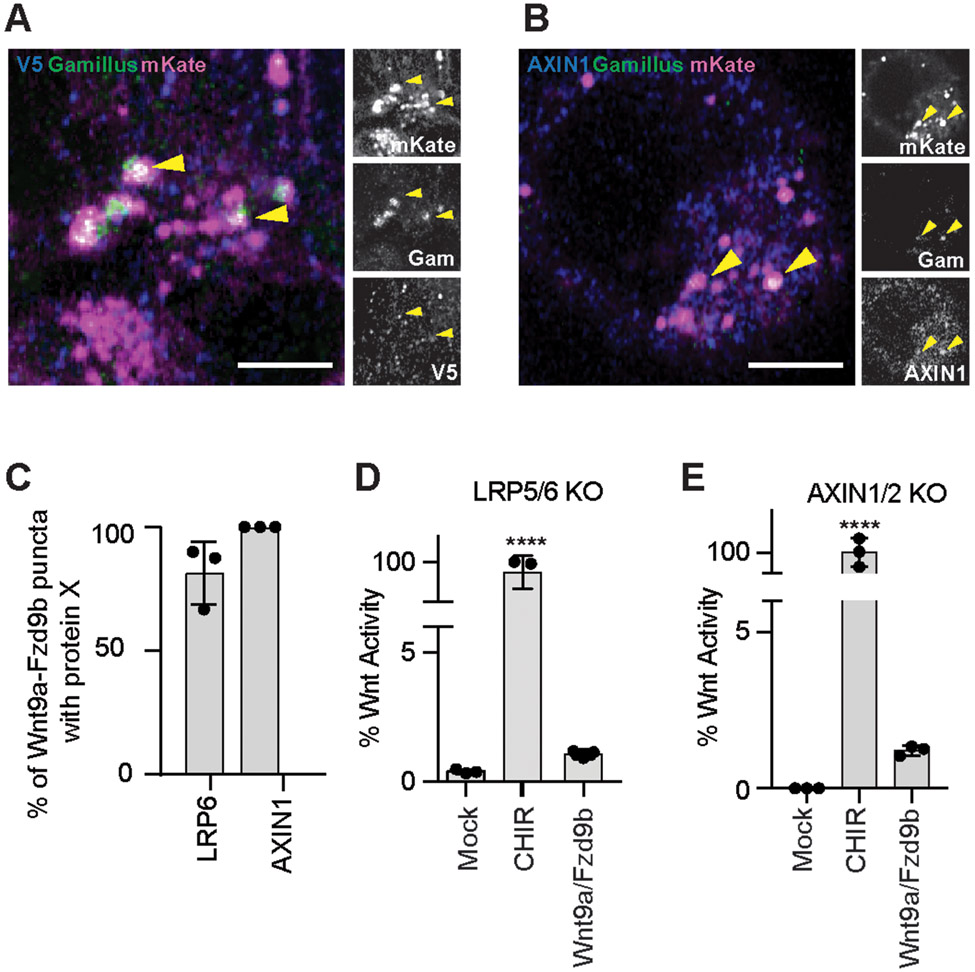

We next sought to identify the mechanism through which endocytosis of Wnt9a-Fzd9b is initiated at the membrane. The co-receptors Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5 and 6 (LRP5 and LRP6) are required for the Wnt9a-Fzd9b signal (8), and it is thought that dissociation of the destruction complex is initiated when the key destruction complex scaffold protein AXIN is recruited to LRP 5 or LRP6 (LRP5/6) (64-66). To determine if LRP6 is found in the Wnt9a-Fzd9b receptor complex, we transiently transfected LRP6-V5 and we were able to visualize LRP6 co-staining with Wnt9a-Fzd9b endosomes (Fig. 5A). Similarly, we were able to find AXIN1 colocalized with Wnt9a-Fzd9b puncta (Fig. 5B, C), supporting a putative requirement for both LRP and AXIN in Wnt9a-Fzd9b signaling.

Fig. 5. LRP5/6 and AXIN1/2 are required for Wnt9a-Fzd9b signaling.

(A) Representative confocal z-stacks of immunofluorescence on Fzd9b-mKate cells treated for one minute with Wnt9a-Gam CM. Scale bar represents 2.5 μm. Images are representative of N = 3 independent experiments. (B) Representative confocal z-stacks of immunofluorescence on Fzd9b-mKate cells treated for one minute with Wnt9a-Gam CM. Scale bar represents 5 μm. Images are representative of N = 3 independent experiments. (C) Quantification of co-occurrences of markers denoted in Wnt9a-Fzd9b puncta in (A-B). Data are presented from N=3 biological replicates. Super TOP Flash assays in Fzd9b-mKate LRP5/6 DKO Super TOP Flash HEK293 cells (D), or AXIN1/2 DKO Super TOP Flash HEK293 cells (E), induced with mock or Wnt9a CM, or the Wnt agonist CHIR. Data presented are from N=3 biological replicates, with different experiments conducted on different days a total of 3 times with similar results. ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001 by ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc comparison.

To determine if LRP5 and LRP6 are required for Wnt9a-Fzd9b endocytosis, we generated LRP5/6 double knockout (DKO) HEK293 Super TOP Flash cells using CRISPR with Cas9 (CRISPR/Cas9) in our previously established LRP6 knockout cells (8). We isolated a clone with 10 bp deletion and 1 bp insertion alleles, which were both predicted to cause frameshift mutations and loss of LRP5 function (Supplementary Fig. 5A); we did not detect any LRP5 or LRP6 protein in these LRP5/6 DKO cells (Supplementary Fig. 5B). As expected, these cells maintained their ability to respond to the Wnt agonist CHIR, which operates downstream of the receptor complex, but we could not detect and Wnt9a-Fzd9b signaling in the absence of LRP5/6 (Fig. 5D), indicating that LRP5/6 are required for signal transduction. In the absence of LRP5/6, Wnt9a-Fzd9b complexes were readily endocytosed (Supplementary Fig. 5C), indicating that LRP5/6 was not required for endocytosis.

To determine if AXIN1 and AXIN2 are required for Wnt9a-Fzd9b endocytosis, we used a previously established HEK293 AXIN1 and 2 (AXIN1/2) DKO line (67) and stably integrated Super TOP Flash and Fzd9b-mKate transgenes. As expected, these cells maintained their response to CHIR, but did not transduce the Wnt9a-Fzd9b signal (Fig. 5E). Wnt9a-Fzd9b complexes were still endocytosed in the absence of AXIN1/2 (Supplementary Fig. 5D). Taken together, these data suggest that endocytosis occured upstream of recruitment of key signaling components.

Wnt9a-Fzd9b endocytosis requires EGFR-mediated phosphorylation of the Fzd9b tail

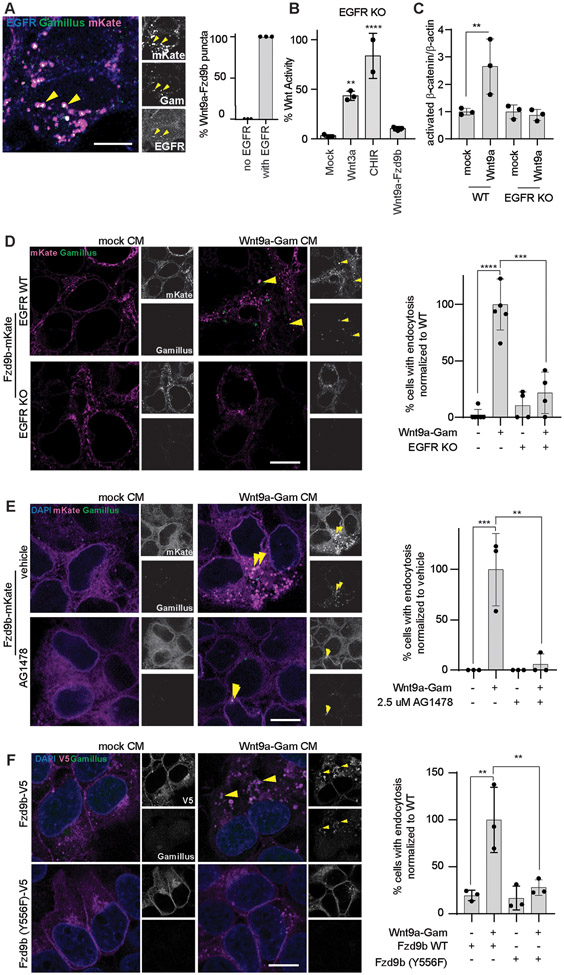

We previously determined that EGFR is an obligate co-factor for the Wnt9a-Fzd9b signal: in response to Wnt9a, EGFR is required to phosphorylate tyrosine 556 (TYR556) on the Fzd9b cytoplasmic tail for signal initiation, independent of the canonical EGFR signaling pathway (8). To test if EGFR was internalized with Wnt9a and Fzd9b, we treated Fzd9b-mKate cells with Wnt9a-Gam CM and stained for EGFR and found that EGFR was colocalized with Wnt9a-Fzd9b endosomes (Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6. Wnt9a-Fzd9b trafficking requires EGFR-initiated phosphorylation of the Fzd9b tail at Tyr556.

(A) Representative confocal z-stacks of immunofluorescence on Fzd9b-mKate cells treated for one minute with Wnt9a-Gam CM. Images are representative of N = 3 independent experiments. Scale bar is 2.5 μm; quantification of co-occurrences on the right. (B) Super TOP Flash assays in EGFR KO HEK293 cells, induced with CM, or CHIR. Data presented are from N=3 biological replicates, with different experiments conducted on different days a total of 3 times with similar results. C. Quantification of immunoblots for active β-catenin (see Supplementary Fig. 6D) in Fzd9b-mKate WT or EGFR KO HEK293 cells treated with CM for 1 minute. Data are representative of N = 3 independent experiments. (D-F). Representative confocal z-stacks of indicated cell lines induced with CM, and fixed after one minute, quantified on the right. Scale bars 10 μm. Data presented are from N=3 biological replicates, with different experiments conducted on different days a total of 3 times with similar results. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001 by ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc comparison.

To study the function of EGFR in Wnt9a-Fzd9b endocytosis, we generated EGFR knockout (KO) HEK293 cells using CRISPR/Cas9. We identified a clone with several early mutations in the EGFR coding sequence (Supplementary Fig. 6A). These cells had undetectable amounts of EGFR protein (Supplementary Fig. 6B) and lacked tyrosine phosphorylation activity (Supplementary Fig. 6C). EGFR is a specific co-factor for the Wnt9a-Fzd9b signal and as expected, EGFR KO cells were able to respond to the prototypical ligand Wnt3a and the agonist CHIR, but not to Wnt9a (Fig. 6B-C, Supplementary Fig. 6D).

To determine if EGFR is required for Wnt9a-Fzd9b endocytosis, we generated transgenic Fzd9b-mKate cells in the EGFR KO background, and treated these or control EGFR wild-type cells with either mock CM or Wnt9a-Gam CM. In the absence of EGFR, Wnt9a-Fzd9b endocytosis was nearly completely absent (Fig. 6D). To test if the enzymatic function of EGFR is required for this endocytic event, we used EGFR wild-type Fzd9b-mKate cells treated with Wnt9a-Gam CM or mock CM in the presence of the EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor AG-1478 or vehicle and found that AG-1478 also compromised Wnt9a-Fzd9b endocytosis (Fig. 6E). We next compared the capacity for Fzd9b Tyr556Phe, which lacks the ability to be phosphorylated by EGFR in response to Wnt9a (8), to be endocytosed in response to Wnt9a. We found that in the absence of this key tyrosine phosphorylation site, Wnt9a-Fzd9b endocytosis was severely hampered (Fig. 6F), even though Fzd9b Tyr556Phe-V5 can make it to the cell surface (Supplementary Fig. 1E). Altogether, these results indicate that EGFR-mediated phosphorylation of the Fzd9b tail at Tyr556 was required for Wnt9a-Fzd9b endocytosis.

EPS15 is required for Wnt9a-Fzd9b endocytosis and signaling

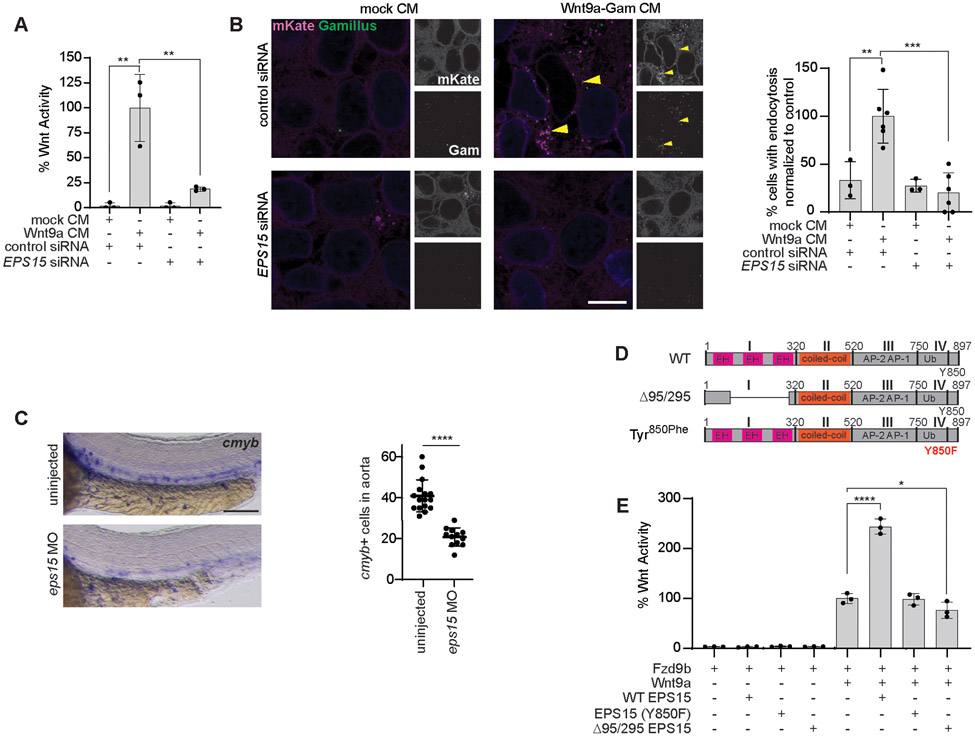

During EGFR signaling events, the EGFR receptor can be endocytosed through multiple mechanisms, and these lead to distinct transcriptional responses (53, 54, 57, 58). One of the key mediators of EGFR endocytosis is the adaptor protein EPS15, which also has roles in endocytosis of other receptors (39, 41, 68-70). To identify proteins that are localized to the Fzd9b tail, we had previously conducted an APEX2-mediated proximity ligation screen (8), whereas we found that EPS15 is enriched to nearly the same degree as EGFR (Supplementary Fig. 7A). We used Wnt9a treatment of Fzd9b Super TOP Flash cells in the context of either control or EPS15 siRNA sequences and found that under conditions of undetectable EPS15 protein (Supplementary Fig. 7B), Wnt9a-Fzd9b signaling was severely compromised (Fig. 7A, Supplementary Fig. 4D).

Fig. 7. EPS15 is required for Wnt9a-Fzd9b endocytosis and signaling.

(A) Super TOP Flash assays in HEK293 cells stably expressing Fzd9b-mKate and the Super TOP Flash reporter, treated with the indicated siRNA, and induced with conditioned medium (CM). Data presented are from N=3 independent experiments conducted on different days, each with 3 biological replicates. (B) Representative confocal z-stacks showing mKate and Gamillus in Fzd9b-mKate cells, treated with siRNAs as indicated, and induced with CM containing Wnt9a-Gam for one minute. Scale bar, 10 μm. The percentage of cells showing endocytosis of Fzd9b-mKate was quantified on the right; N=3-6, biological replicates, as indicated by dots. (C) Zebrafish at 40 hpf stained for the hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell maker cmyb by in situ hybridization. Scale bar, 100 μm. The number of cmyb+ cells in the aorta was quantified on the right. Data presented are from N=15 biological replicates, with experiments conducted on 3 different days with similar results. (D) EPS15 construct schematics. (E) Super TOP Flash assays conducted in HEK293 cells stably expressing Fzd9b-mKate and Super TOP Flash, transfected with EPS15 constructs, and induced with Wnt9a-Gam CM. Data presented are from N=3 biological replicates, with different experiments conducted on different days a total of 3 times with similar results. ****P<0.0001 by Two-tailed student’s t-test in (C). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 by ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc comparison for all other panels.

To determine if EPS15 plays a role in Wnt9a-Fzd9b receptor complex internalization, we examined Wnt9a-Fzd9b internalization after 1 minute of Wnt9a-Gam CM treatment in the context of control or EPS15 siRNA sequences and found a loss of endocytosis of Wnt9a-Fzd9b without EPS15 (Fig. 7B), indicating that EPS15 was required for Wnt9a-Fzd9b endocytosis.

We have previously shown that the Wnt9a-Fzd9b signal is required in vivo for HSPC proliferation; defects in this process can be visualized using in situ hybridization for the HSPC marker cmyb at 40 hours post fertilization (hpf) in zebrafish (8, 9). To identify if Eps15 plays a role in HSPC proliferation, we injected an antisense morpholino (MO) targeting the translational start site of eps15 into wild-type zebrafish zygotes and analyzed the cmyb+ cells in the floor of the dorsal aorta at 40 hpf, whereas we found a loss of cmyb+ cells in eps15 MO animals (Fig. 7C), supporting a role for Eps15 in HSPC ontogeny. We observed similar losses of cmyb+ cells using increased concentrations of eps15 MO (Supplementary Fig. 7C). These losses were not due to injection of nucleotides, because comparison to an identical concentration of standard MO also displayed a loss of cmyb+ cells (Supplementary Fig. 7D). The translation-blocking MO was able to be rescued with eps15 mRNA injection (Supplementary Fig. 7E), and we observed identical results using a splice-blocking MO (Supplementary Fig. 7F-G), and indicating that loss of HSPCs was not due to off-target effects. Finally, we used CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutagenesis to generate chimeric F0 mutants with a deletion in the proximal promoter, encompassing the transcriptional and translational start sites of the eps15 genomic locus, which would be predicted to cause a total loss of Eps15 protein (Supplementary Fig. 7H); these animals also exhibited a loss of cmyb+ cells in the aorta (Supplementary Fig. 7I). PCR amplification at the Eps15 genomic locus showed smaller bands, indicating successful deletion; these were sequence validated (Supplementary Fig. 7J). Altogether, these results indicate that Eps15 was required for HSPC development and support its function in the Wnt9a-Fzd9b pathway.

EPS15 has been subdivided into four main domains (I-IV, Fig. 7D). Residues 95-295 (Δ95/295, most of domain I encoding the EH domains) has been reported to be required for transferrin receptor and EGFR endocytosis (44); the Tyr850 residue has been reported as a substrate for EGFR required for endocytosis (41). To test if EPS15 impacted on the Wnt9a-Fzd9b Super TOP Flash signal, we transfected either WT, Tyr850Phe or Δ95/295 into our Wnt9a-Fzd9b Super TOP Flash reporter assay. Whereas we observed approximately 2.5x enhanced Wnt9a-Fzd9b activity in the context of wild-type EPS15, the signal was not enhanced by either Tyr850Phe or Δ95/295 EPS15 (Fig. 7E); we observed very slight dominant-negative activity with Δ95/295 EPS15 (Fig. 7E). Differences in signaling were not due to differences in EPS15 expression (Supplementary Fig. 7K). Taken altogether, these data indicate that EPS15 was a key component of Wnt9a-Fzd9b endocytosis and signaling, and that both domains previously described to impact on EGFR endocytosis are required for this function.

Discussion

The Wnt pathway regulates a plethora of downstream biological events, likely through a medley of diverse transcriptional and non-transcriptional outputs driving changes in a panoply of cell types and tissues. At least part of the complexity of this system lies in the multitude of ligands (at least 19 in vertebrates) and receptors (at least 10 in vertebrates). One of the bigger mysteries in Wnt biology is deciphering how the different Wnt ligands choose their cognate receptors and co-receptors, and how these lead to the diverse outputs seen in development, homeostasis, and disease. One way to begin deciphering these mechanisms of specific Wnt-Fzd interactions is to visualize cell biological events involving known cognate pairings, which we have done here using the pairing of Wnt9a and Fzd9b that we previously demonstrated are required for HSPC proliferation in developing zebrafish and human cells (8, 9).

The ability to monitor functional Wnt ligands has been challenging because Wnt fusion proteins often lose functionality. There are a small handful of examples of successfully tagging Wnt proteins with fluorophores; these have proven to be valuable in understanding cell signaling biology. For example, GFP-tagged mouse Wnt3a was used to visualize differences in binding of the promiscuous Wnt3a ligand to different Fzd proteins (46), as well as to monitor how diffusion of Wnt3a is regulated (47). Xenopus wnt2b-GFP provided insights into how Wnts can move along cellular protrusions (48). Chick WNT1-GFP was used to show how Wntless is involved in changing the distribution of WNT1 (49). Imaging Xenopus wnt5a-GFP suggests receptor clustering at the membrane is important for signaling (50), and zebrafish GFP-Wnt8 can be seen traveling from one cell to another in early neural plate development (51). The field has therefore only begun to exploit visualizing Wnt ligands.

Here, we demonstrated that the location of the tag, as well as the fluorophore and linker sequence are all important to consider when deriving Wnt fusion proteins. Related to this, mouse Wnt3a and xenopus Wnt8 tolerate GFP tagging at the N-terminus (46, 47, 51), whereas we found that C-terminal tagging of Wnt9a was better tolerated (Supplementary Fig. 2C), as has also been reported for Xenopus wnt2b (48), chick WNT1 (48) and Xenopus Wnt5a (50). These differences may be because of differences in location, or linker sequence and/or length, and they likely need to be determined empirically for each Wnt.

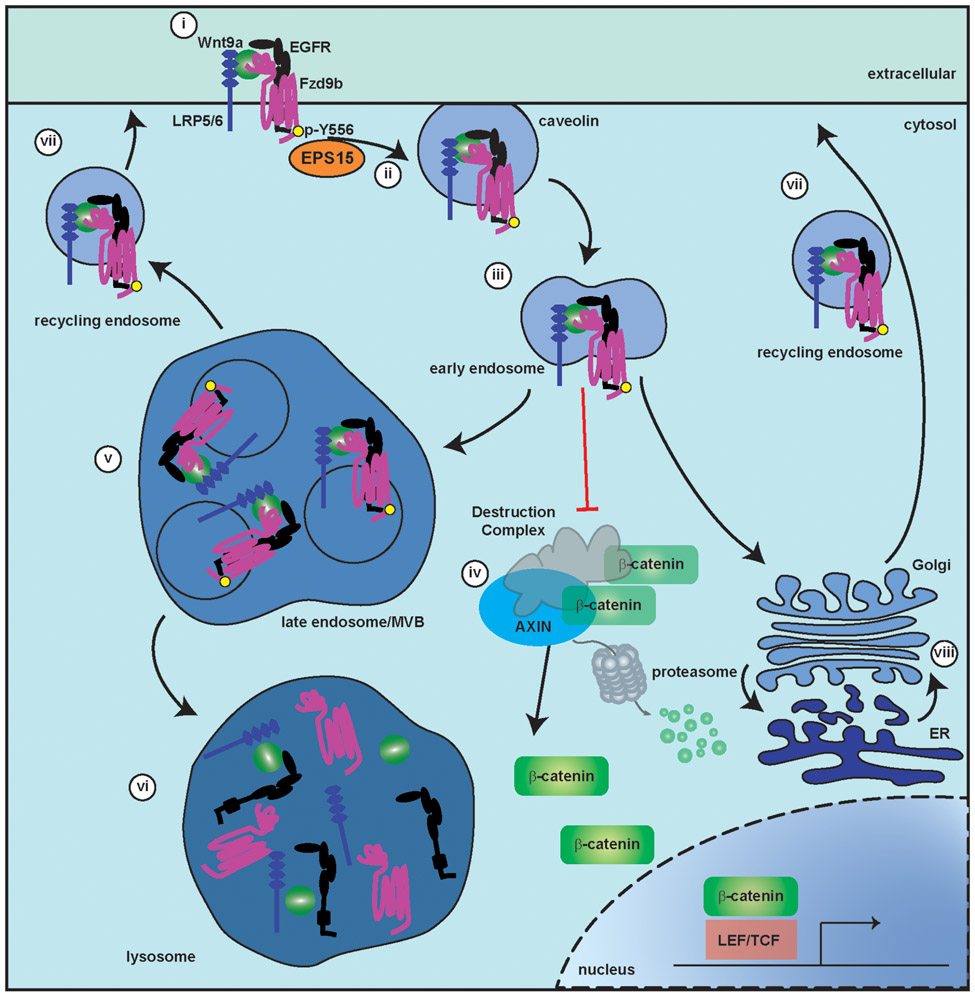

By administering our biologically functional Wnt9a-Gam protein to Fzd9b-mKate cells, we were able to visualize endocytosis and trafficking of the Wnt9a-Fzd9b complex (Fig. 3). Our data indicate that this endocytosis event destines the complex for either degradation or recycling (Fig. 8). Non-specific small molecule inhibition of endocytosis leads to a loss of the nuclear β-catenin mediated Wnt signal (Supplementary Fig. 3B-C), which also occurs in response to loss of CAV1 (Fig. 4B). These data are very interesting in the landscape of previous data from the Wnt field. For instance, neither clathrin, nor caveolin-mediated endocytosis are required for Wnt3a signaling in mouse embryonic stem cells (38). However, a previous report from the same group suggests that mouse Wnt3a signaling is sensitive to some chemical inhibitors of endocytosis such as chlorpromazine, hypertonic sucrose or monodansylcadaverine (37). As the authors suggest, the differences between the two systems examining mouse Wnt3a likely lies in the now well documented off-target effects of these chemical modulators (38, 71). Indeed, we have observed these off-target effects in our own system, as we previously reported that chlorpromazine has an impact on Wnt9a-Fzd9b signaling (8). These findings do not negate our previous data, but clarify the requirement for an CAV1 and EPS15–dependent pathway in Wnt9a-Fzd9b signaling. In HeLaS3 cells, the co-receptor LRP6 is internalized through caveolin in response to mouse Wnt3a, and this is required for Super TOP Flash activity; however, it is not clear if the Wnt3a ligand is also endocytosed (35). In addition, further studies indicate that the observed differences in downstream signaling may actually be related to the importance of clathrin and AP2 for forming LRP6 signalosomes at the membrane (72), or trafficking of the LRP6 receptor (73, 74), rather than for endocytosis of the receptor complex itself. In contrast to mouse Wnt3a, the Drosophila ligand, Wingless (Wg), has been shown to require Rab5-mediated endocytosis (31), and Vacuolar H+-ATPase-mediated acidification has been shown to be required for Wnt3a signaling (75), suggesting that at least some Wnt ligands need to be internalized for function. Taken altogether, and in context of our findings, it stands to reason that one mechanism of the context-dependent specificity required downstream of different Wnt-Fzd pairings lies within endocytosis.

Fig. 8. A model for Wnt9a-Fzd9b endocytosis, trafficking and signaling.

i. When Wnt9a binds to the cell surface receptor complex including Fzd9b, EGFR and LRP5/6, EGFR phosphorylates the Fzd9b tail at Tyr556. ii. EPS15 and Caveolin are required for endocytosis of the complex into early endosomes (iii), where the receptor complex inhibits the destruction complex, allowing β-catenin release and translocation to the nucleus for target gene expression (iv). The Wnt9a-Fzd9b complex is further trafficked to the late endosome/multi-vesicular body (MVB, v), the lysosome (vi), the recycling endosome (vii), and the endoplasmic reticulum (ER, viii).

We observed that although CAV1 and EPS15 siRNA knockdown both seem to eliminate Wnt9a-Fzd9b endocytosis (Fig. 4C, D and Fig. 7B, C), these do not ablate the Super TOP Flash signal, but suppress it (Fig. 4B and Fig 7A). Taken together, these data suggest that Wnt9a-Fzd9b may be able to signal from both the plasma membrane and the early endosome. This observation is especially interesting in the landscape of EGFR signaling through its canonical pathway, whereas reports indicate that different downstream transcriptional signal can be elicited from EGFR at the plasma membrane or from endosomes (76).

Mechanistically, we have demonstrated that Wnt9a-Fzd9b endocytosis requires EGFR-phosphorylation of the Fzd9b tail at Tyr556 (Fig. 6D-F), and phosphorylation of Tyr850 of the adaptor protein EPS15 (Fig. 7E), as well as the N-terminal EH domains of EPS15 (Fig. 7E), to initiate caveolin-mediated endocytosis. EPS15 is also required for EGFR and Transferrin Receptor endocytosis (53, 70); Wnt9a-Fzd9b endocytosis may proceed through similar or overlapping pathways. The requirement for Tyr556 phosphorylation and our previously observed requirement for Wnt9a to initiate this phosphorylation event also invoke a model in which Wnt9a bridges together Fzd9b, LRP, AXIN and EGFR at the earliest stage of signaling (Fig. 8). We have also demonstrated that AXIN1/2 and LRP5/6 are dispensable for Wnt9a-Fzd9b endocytosis; however, these are still critical to signaling, likely through LRP5/6 interaction with the destruction complex through AXIN. This observation, paired with the requirement for AXIN in signaling, but not endocytosis, suggest that the complex containing Wnt9a, Fzd9b, EGFR and LRP5/6 is endocytosed, and that AXIN is recruited downstream of this event.

The requirement for co-receptors in specific Wnt signals is starting to be better appreciated as a mechanism of regulating downstream signaling specificity (77-81). These observations support the overall notion that co-receptors with enzymatic activity may be recruited to various Wnt-Fzd pairings, resulting in different types of endocytosis. These endocytic events may then either activate, or inhibit the Wnt signal, likely depending on the cellular and molecular context.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

We had previously established HEK293 cells with a stably integrated Super-TOP-Flash reporter (Super TOP Flash) (45), which were used for all luciferase assays, or to further derive stably integrated transgenic lines. AXIN1/2 double knockout cells were a generous gift from Vítězslav Bryja (Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic). HEK293 and HEK293T were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Fisher Scientific), supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS, Peak Serum) and 1% penicillin and streptomycin under standard conditions.; Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells were grown in a 50:50 mix of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) and F12 (Fisher Scientific), supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin under standard conditions. Cells were routinely tested for mycoplasma contamination, which was always negative.

Generation of transgenic and knockout cell lines and conditioned medium

LRP6 knockout HEK293 Super TOP Flash cells were previously generated (8); LRP5/6 double knockout (DKO) cells were generated by transfecting a confluent 100mm plate of LRP6 knockout HEK293T Super TOP Flash cells with 3 mg each of plasmids harboring either Cas9 (82) and two guide RNAs under regulatory control of a U6 promoter targeting beta-propeller 1 of LRP5 (See Supplementary Table 1 for sequences). Single cell clones were validated for loss of LRP5 coding sequence by sequencing the genomic locus (See Supplementary Table 2 for primer sequences), and immunoblotting using a rabbit monoclonal antibody (D80F2, Cell Signaling Technologies, 5731S). EGFR knockout cells were generated in a similar fashion using two guide RNAs which target early coding sequences in the second exon. Single cell clones were validated by sequencing the genomic locus, and immunoblotting with rabbit monoclonal antibody (EP38Y, Abcam, ab52894). EGFR knockout cells were also validated by testing for loss of tyrosine phosphorylation in response to a one-minute treatment with 50 ng/mL mouse EGF by immunoblotting with mouse monoclonal antibody (PY20, BioLegend, 309301).

Transgenic cell lines were generated using the PiggyBAC transposase system (83). Briefly, 100mm plates of parental cell lines were transfected using polyethyleneimine (PEI), with 5 ug of hyperactive PiggyBAC transposase, and 5 ug of plasmid harboring the cargo (including antibiotic resistance cassettes) flanked by PiggyBAC recombination sites. Individual clonal lines were generated using antibiotic selection and standard methods. Clonal lines were validated using immunoblotting and luciferase reporter assays, compared with untagged sequences.

Stable transgenic CHO cell lines harboring doxycycline inducible Wnt proteins were grown to confluence in 150 mm plates, supplemented with 500 ng/mL doxycycline, and cultured for 10 days further, with additional doxycycline spiked in at 500 ng/mL every 3 days. Conditioned medium was collected from parental (mock CM), or transgenic (Wnt CM) lines, filtered sterilized with a 0.22 μm filter and validated for Wnt activity using Super TOP Flash assays. CM was considered active if Wnt CM was at least 40X more active than mock CM. Active CM was stored aliquoted at −80°C and diluted 1:2 with fresh medium prior to use on cells.

Luciferase reporter Super TOP Flash assays

Luciferase reporter assays were performed with either transient transfection, or stable lines, as indicated in the figures. For transient transfection, 293 Super TOP Flash cells were seeded into twelve-well plates and transfected using polyethyleneimine (PEI), 50 ng of renilla reporter vector, 200 ng of Wnt or Fzd expression vector, with a total of 1 ug of DNA/well. When stable lines and conditioned medium were used, cells were seeded into twelve-well plates and after 24 hours were treated with a 1:1 mixture of fresh and conditioned medium. For siRNA experiments, a 6 well plate was treated with 30 pmol of siRNA using RNAiMax transfection reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. (See Supplementary Table 3 for siRNA sequences). All transfected cells were harvested or treated 48 hours post-transfection and all conditioned medium or co-cultured cells were harvested 24 hours post-treatment; the lysates processed and analyzed using the Dual Luciferase Assay System (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In small molecule treatments, Fzd9b Super TOP Flash cells were treated with small molecule or vehicle for time described in the figure legend, and treated with Wnt9a or mock conditioned medium for 24 hours prior to being processed as above for Luciferase assays. Each experiment was performed with at minimum biological triplicate samples and reproduced at least once with a similar trend. Wnt activity was calculated by normalizing Firefly Luciferase output to Renilla Luciferase; Wnt9a-Fzd9b fold induction was set to 100.

Wnt protein enrichment and immunoblotting

Enrichment of Wnt proteins was accomplished using a Blue Sepharose pulldown, based on previously established Wnt purification methods (84). Briefly, 2.5 mL of CM was supplemented with 1% Triton X-100, 20 mM Tris-Cl, and 0.1% NaN3, and filtered through a 0.22 μm syringe filter. Blue Sepharose 6 Fast Flow Agarose beads (GE, 17-0948-01) were washed with PBS and resuspended in a 50:50 PBS:beads slurry. A mixture of 2 mL of Wnt CM and 20 μL of Blue Sepharose were incubated for 90 minutes, rocking end over end at room temperature. Beads were collected by centrifugation at 400 g for 5 minutes and washed three times with 1 mL cold Wnt wash buffer (1% CHAPS, 150 mM KCl, 50 mM Tris-Cl in PBS). Wnt proteins were dissociated from the beads by heating to 95°C in Laemmli buffer (85) for 5 minutes.

For cell lysate immunoblots, cells were harvested 48 hours after transfection in TNT buffer (1% Triton X-100, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris, pH8.0), with protease inhibitors. Immunoblots were performed according to standard procedures (lysates subjected to blotting for Fzds were not boiled), using antibodies for: antibodies against tRFP, [1:1,000, mKate antibody, Evrogen, AB233], FLAG, [1:1,000, Sigma, F1804], α-V5, [1:5,000, Cell Signaling Technologies, 13202S], β−actin, [1:10,000, Sigma, A2228], 1:500, Fzd9b (8), 1:500, Wnt9a (10), CAV1, [Cell Signaling Technologies, 3267], Clathrin, [Invitrogen, MA1-065], EPS15, [R&D Systems, AF8480], LRP6, [Cell Signaling Technologies, 2560S], LRP5, [Cell Signaling Technologies, 5731S], EGFR, [Abcam, ab52894], pTyr, [BioLegend, 309301], β-catenin (total) [Cell Signaling Technologies, 8480S], activated-β-catenin [Cell Signaling Technologies, 8814S], rabbit-HRP, [1:20,000, Southern Biotech, 4050-05], mouse-HRP, [1:20,000, Southern Biotech, 1013-05].

Plasmids

Expression constructs for fusion proteins were generated by standard means using PCR from plasmids harboring a CMV promoter, or a doxycycline inducible promoter system. Addgene provided expression vectors for Eps15-mCherry (27696), Cas9 (47929) and guide RNAs (46759).

Confocal imaging and analysis

Glass coverslips (#1.5, 12mm diameter) were coated with Cultrex Poly-L-Lysine (R&D systems, 34-382-0001) for 1 hour at 37°C, washed 3 times with water and air dried. Cells were plated on coated coverslips for 24 hours prior to addition of CM in an equal volume to the culture medium already present. Cells were fixed by removing medium, washing three times with ice cold PBS++ (containing Mg++ and Ca++) and incubating with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 20 minutes at room temperature. For direct imaging of fluorescently labeled transgenic cells, slides were mounted using vectashield mounting medium and imaged within one week.

For immunofluorescence, cells were prepared and fixed as above, and incubated in blocking buffer (2% BSA in PBS++) for 60 minutes at room temperature, and in primary antibodies targeting (tRFP, [mKate antibody, Evrogen, AB233], FLAG, [Sigma, F1804], V5, [Cell Signaling Technologies, 13202S], Fzd9b (8),-Wnt9a (10), α-Rab5, [Cell Signaling Technologies, 3547S], Rab7, [Cell Signaling Technologies, 9367S], Rab9a, [Proteintech, 11420-1-AP], Grp94, [Cell Signaling Technologies, 20292], LAMP1, [Invitrogen, MA5-29385]), AXIN1, [Cell Signaling Technologies, 2087T]), EGFR, [Invitrogen, cat#MA5-13070, lot#WJ3413155]) diluted 1:50-1:250 in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C. Cells were washed three times in PBS++, incubated in secondary antibody (1:500 for each, Goat-α-mouse Alexa 488 [cat# A11001, lot# 2189178], goat-α-rabbit Alexa 488 [cat# 4050-30, lot# e1317 NC39], goat-α-mouse Alexa 555 [cat# 1030-32, lot# E2518 ZA08E], goat-α-rabbit Alexa 647 [cat# 4050-31, lot# E1519 S109Z], Southern Biotech) diluted in blocking buffer for 60 minutes at room temperature, washed three times in PBS++, and mounted in vectashield mounting medium (with or without DAPI). Transferrin-488 (Fisher, T13342) internalization was performed essentially as previously described (38), 48 hours post siRNA transfection. Slides were imaged within one week.

Confocal z-slices were collected using a Zeiss LSM 880 with Airyscan, equipped with 405, 458, 488, 514, 561 and 633 nm laser lines and 5x air, 10x air, 20x air, 40x water, 63x oil and 100x oil objectives. Scanning was sequential and images were collected at a minimum of 1900 x 1900 resolution; images were processed using Airyscan Fast mode. Representative images were produced by combining 1-10 z-slices. Calculation of % events was performed by examining z-stacks through the entire cell and identifying cells that had internalized green puncta and dividing by the total number of cells in the field of view.

Zebrafish husbandry, in situ hybridization, and qPCR analysis

Zebrafish were maintained and propagated according to Van Andel Institute and local Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee policies. AB* zebrafish were used in all experiments. The MOs for eps15 were targeted to block the ATG start codon or to block splicing from GeneTools. Morpholino sequences can be found in Supplementary Table 4. Morpholinos were resuspended in UltraPure water at 25mg/mL and stored at −80°C between uses. 1-cell stage zygotes were injected with ATG-blocking eps15 MO or splice-blocking eps15 MO at concentrations indicated in figures. RNA and cDNA were synthesized by standard means and qPCR was performed using FastStart Universal SYBR Green Master Mix (Roche) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations and analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCt method (86). Primers used in qPCR analyses are found in Supplementary Table 5.

CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mosaic knockout of Eps15 was conducted using guide RNAs about 250 bp upstream and 40 bp downstream of the translational start site of the eps15 genomic locus. F0 AB* zygotes were injected with 28.5 fmol of Cas9 protein (IDT, 10007807) and 7.1 fmol of each sgRNA in the center of the yolk. Resultant F0 “crispant” animals were screened for an approximately 300 bp genomic deletion using primers in Supplementary Table 2.

RNA probe synthesis was carried out according to the manufacturer’s recommendations using the DIG-RNA labeling kit, or the fluorescein labeling kit for FISH (Roche). Probe for cmyb and WISH protocols have been previously described (87-89).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The authors thank Hannah Morris-Little and Jordan Setayesh for technical assistance in generating EGFR and LRP5/6 DKO cells, respectively. AXIN1/2 DKO cells were a generous gift from Vita Bryja (Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic). Imaging, analysis, and quantification was performed in part by the Van Andel Institute Optical Imaging Core (RRID:SCR_021968); Lorna Cohen is thanked for image acquisition.

Funding:

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R00HL133458, and by the National Institute of General Medical Science under Award Number R35GM142779. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper or the Supplementary Materials. All materials are available upon reasonable request and execution of an MTA. Requests for materials should be addressed to SG at stephanie.grainger@vai.org.

References and Notes

- 1.Clevers H, Nusse R, Wnt/beta-catenin signaling and disease. Cell 149, 1192–1205 (2012); published online EpubJun 8 ( 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nusse R, Clevers H, Wnt/beta-Catenin Signaling, Disease, and Emerging Therapeutic Modalities. Cell 169, 985–999 (2017); published online EpubJun 1 ( 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhanot P, Brink M, Samos CH, Hsieh JC, Wang Y, Macke JP, Andrew D, Nathans J, Nusse R, A new member of the frizzled family from Drosophila functions as a Wingless receptor. Nature 382, 225–230 (1996); published online EpubJul 18 ( 10.1038/382225a0). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ring L, Neth P, Weber C, Steffens S, Faussner A, beta-Catenin-dependent pathway activation by both promiscuous "canonical" WNT3a-, and specific "noncanonical" WNT4- and WNT5a-FZD receptor combinations with strong differences in LRP5 and LRP6 dependency. Cell Signal 26, 260–267 (2014); published online EpubFeb ( 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.11.021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Voloshanenko O, Gmach P, Winter J, Kranz D, Boutros M, Mapping of Wnt-Frizzled interactions by multiplex CRISPR targeting of receptor gene families. Faseb J 31, 4832–4844 (2017); published online EpubNov ( 10.1096/fj.201700144R). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dijksterhuis JP, Baljinnyam B, Stanger K, Sercan HO, Ji Y, Andres O, Rubin JS, Hannoush RN, Schulte G, Systematic mapping of WNT-FZD protein interactions reveals functional selectivity by distinct WNT-FZD pairs. J Biol Chem 290, 6789–6798 (2015); published online EpubMar 13 ( 10.1074/jbc.M114.612648). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu H, Ye X, Guo N, Nathans J, Frizzled 2 and frizzled 7 function redundantly in convergent extension and closure of the ventricular septum and palate: evidence for a network of interacting genes. Development 139, 4383–4394 (2012); published online EpubDec 1 ( 10.1242/dev.083352). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grainger S, Nguyen N, Richter J, Setayesh J, Lonquich B, Oon CH, Wozniak JM, Barahona R, Kamei CN, Houston J, Carrillo-Terrazas M, Drummond IA, Gonzalez D, Willert K, Traver D, EGFR is required for Wnt9a-Fzd9b signalling specificity in haematopoietic stem cells. Nat Cell Biol 21, 721–730 (2019); published online EpubJun ( 10.1038/s41556-019-0330-5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grainger S, Richter J, Palazon RE, Pouget C, Lonquich B, Wirth S, Grassme KS, Herzog W, Swift MR, Weinstein BM, Traver D, Willert K, Wnt9a Is Required for the Aortic Amplification of Nascent Hematopoietic Stem Cells. Cell Rep 17, 1595–1606 (2016); published online EpubNov 1 ( 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.10.027). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richter J, Stanley EG, Ng ES, Elefanty AG, Traver D, Willert K, WNT9A Is a Conserved Regulator of Hematopoietic Stem and Progenitor Cell Development. Genes (Basel) 9, (2018); published online EpubJan 29 ( 10.3390/genes9020066). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaksonen M, Roux A, Mechanisms of clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 19, 313–326 (2018); published online EpubMay ( 10.1038/nrm.2017.132). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mayor S, Parton RG, Donaldson JG, Clathrin-independent pathways of endocytosis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 6, (2014); published online EpubJun 2 ( 10.1101/cshperspect.a016758). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seaman MNJ, Retromer and Its Role in Regulating Signaling at Endosomes. Prog Mol Subcell Biol 57, 137–149 (2018) 10.1007/978-3-319-96704-2_5). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burd C, Cullen PJ, Retromer: a master conductor of endosome sorting. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 6, (2014); published online EpubFeb 1 ( 10.1101/cshperspect.a016774). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferrandon S, Feinstein TN, Castro M, Wang B, Bouley R, Potts JT, Gardella TJ, Vilardaga JP, Sustained cyclic AMP production by parathyroid hormone receptor endocytosis. Nat Chem Biol 5, 734–742 (2009); published online EpubOct ( 10.1038/nchembio.206). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Calebiro D, Nikolaev VO, Gagliani MC, de Filippis T, Dees C, Tacchetti C, Persani L, Lohse MJ, Persistent cAMP-signals triggered by internalized G-protein-coupled receptors. PLoS Biol 7, e1000172 (2009); published online EpubAug ( 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000172). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuna RS, Girada SB, Asalla S, Vallentyne J, Maddika S, Patterson JT, Smiley DL, DiMarchi RD, Mitra P, Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor-mediated endosomal cAMP generation promotes glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in pancreatic beta-cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 305, E161–170 (2013); published online EpubJul 15 ( 10.1152/ajpendo.00551.2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merriam LA, Baran CN, Girard BM, Hardwick JC, May V, Parsons RL, Pituitary adenylate cyclase 1 receptor internalization and endosomal signaling mediate the pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide-induced increase in guinea pig cardiac neuron excitability. J Neurosci 33, 4614–4622 (2013); published online EpubMar 6 ( 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4999-12.2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feinstein TN, Yui N, Webber MJ, Wehbi VL, Stevenson HP, King JD Jr., Hallows KR, Brown D, Bouley R, Vilardaga JP, Noncanonical control of vasopressin receptor type 2 signaling by retromer and arrestin. J Biol Chem 288, 27849–27860 (2013); published online EpubSep 27 ( 10.1074/jbc.M112.445098). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inda C, Dos Santos Claro PA, Bonfiglio JJ, Senin SA, Maccarrone G, Turck CW, Silberstein S, Different cAMP sources are critically involved in G protein-coupled receptor CRHR1 signaling. J Cell Biol 214, 181–195 (2016); published online EpubJul 18 ( 10.1083/jcb.201512075). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kotowski SJ, Hopf FW, Seif T, Bonci A, von Zastrow M, Endocytosis promotes rapid dopaminergic signaling. Neuron 71, 278–290 (2011); published online EpubJul 28 ( 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.036). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mullershausen F, Zecri F, Cetin C, Billich A, Guerini D, Seuwen K, Persistent signaling induced by FTY720-phosphate is mediated by internalized S1P1 receptors. Nat Chem Biol 5, 428–434 (2009); published online EpubJun ( 10.1038/nchembio.173). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feinstein TN, Wehbi VL, Ardura JA, Wheeler DS, Ferrandon S, Gardella TJ, Vilardaga JP, Retromer terminates the generation of cAMP by internalized PTH receptors. Nat Chem Biol 7, 278–284 (2011); published online EpubMay ( 10.1038/nchembio.545). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wehbi VL, Stevenson HP, Feinstein TN, Calero G, Romero G, Vilardaga JP, Noncanonical GPCR signaling arising from a PTH receptor-arrestin-Gbetagamma complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110, 1530–1535 (2013); published online EpubJan 22 ( 10.1073/pnas.1205756110). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steinberg F, Gallon M, Winfield M, Thomas EC, Bell AJ, Heesom KJ, Tavare JM, Cullen PJ, A global analysis of SNX27-retromer assembly and cargo specificity reveals a function in glucose and metal ion transport. Nat Cell Biol 15, 461–471 (2013); published online EpubMay ( 10.1038/ncb2721). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strigini M, Cohen SM, Wingless gradient formation in the Drosophila wing. Curr Biol 10, 293–300 (2000); published online EpubMar 23 ( 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00378-x). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van den Heuvel M, Nusse R, Johnston P, Lawrence PA, Distribution of the wingless gene product in Drosophila embryos: a protein involved in cell-cell communication. Cell 59, 739–749 (1989); published online EpubNov 17 ( 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90020-2). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nusse R, A versatile transcriptional effector of Wingless signaling. Cell 89, 321–323 (1997); published online EpubMay 2 ( 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80210-x). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rives AF, Rochlin KM, Wehrli M, Schwartz SL, DiNardo S, Endocytic trafficking of Wingless and its receptors, Arrow and DFrizzled-2, in the Drosophila wing. Dev Biol 293, 268–283 (2006); published online EpubMay 1 ( 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.02.006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dubois L, Lecourtois M, Alexandre C, Hirst E, Vincent JP, Regulated endocytic routing modulates wingless signaling in Drosophila embryos. Cell 105, 613–624 (2001); published online EpubJun 1 ( 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00375-0). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seto ES, Bellen HJ, Internalization is required for proper Wingless signaling in Drosophila melanogaster. J Cell Biol 173, 95–106 (2006); published online EpubApr 10 ( 10.1083/jcb.200510123). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li J, Hassan GS, Williams TM, Minetti C, Pestell RG, Tanowitz HB, Frank PG, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP, Loss of caveolin-1 causes the hyper-proliferation of intestinal crypt stem cells, with increased sensitivity to whole body gamma-radiation. Cell Cycle 4, 1817–1825 (2005); published online EpubDec ( 10.4161/cc.4.12.2199). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sotgia F, Williams TM, Cohen AW, Minetti C, Pestell RG, Lisanti MP, Caveolin-1-deficient mice have an increased mammary stem cell population with upregulation of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. Cell Cycle 4, 1808–1816 (2005); published online EpubDec ( 10.4161/cc.4.12.2198). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.MacDonald BT, He X, Frizzled and LRP5/6 receptors for Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 4, (2012); published online EpubDec 1 ( 10.1101/cshperspect.a007880). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yamamoto H, Komekado H, Kikuchi A, Caveolin is necessary for Wnt-3a-dependent internalization of LRP6 and accumulation of beta-catenin. Dev Cell 11, 213–223 (2006); published online EpubAug ( 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.07.003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yamamoto H, Sakane H, Yamamoto H, Michiue T, Kikuchi A, Wnt3a and Dkk1 regulate distinct internalization pathways of LRP6 to tune the activation of beta-catenin signaling. Dev Cell 15, 37–48 (2008); published online EpubJul ( 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.04.015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blitzer JT, Nusse R, A critical role for endocytosis in Wnt signaling. BMC Cell Biol 7, 28 (2006); published online EpubJul 6 ( 10.1186/1471-2121-7-28). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rim EY, Kinney LK, Nusse R, beta-catenin-mediated Wnt signal transduction proceeds through an endocytosis-independent mechanism. Mol Biol Cell 31, 1425–1436 (2020); published online EpubJun 15 ( 10.1091/mbc.E20-02-0114). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Benmerah A, Lamaze C, Begue B, Schmid SL, Dautry-Varsat A, Cerf-Bensussan N, AP-2/Eps15 interaction is required for receptor-mediated endocytosis. J Cell Biol 140, 1055–1062 (1998); published online EpubMar 9 ( 10.1083/jcb.140.5.1055). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Confalonieri S, Di Fiore PP, The Eps15 homology (EH) domain. FEBS Letters 513, 24–29 (2002) 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)03241-0). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Confalonieri S, Salcini AE, Puri C, Tacchetti C, Di Fiore PP, Tyrosine phosphorylation of Eps15 is required for ligand-regulated, but not constitutive, endocytosis. J Cell Biol 150, 905–912 (2000); published online EpubAug 21 ( 10.1083/jcb.150.4.905). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suzuki R, Toshima JY, Toshima J, Regulation of clathrin coat assembly by Eps15 homology domain–mediated interactions during endocytosis. Molecular Biology of the Cell 23, 687–700 (2012) 10.1091/mbc.e11-04-0380). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van PM Bergen En Henegouwen, Eps15: a multifunctional adaptor protein regulating intracellular trafficking. Cell Communication and Signaling 7, 24 (2009) 10.1186/1478-811x-7-24). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Benmerah A, Bayrou M, Cerf-Bensussan N, Dautry-Varsat A, Inhibition of clathrin-coated pit assembly by an Eps15 mutant. J Cell Sci 112 (Pt 9), 1303–1311 (1999); published online EpubMay ( 10.1242/jcs.112.9.1303). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fernandez A, Huggins IJ, Perna L, Brafman D, Lu D, Yao S, Gaasterland T, Carson DA, Willert K, The WNT receptor FZD7 is required for maintenance of the pluripotent state in human embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111, 1409–1414 (2014); published online EpubJan 28 ( 10.1073/pnas.1323697111). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wesslowski J, Kozielewicz P, Wang X, Cui H, Schihada H, Kranz D, Karuna MP, Levkin P, Gross JC, Boutros M, Schulte G, Davidson G, eGFP-tagged Wnt-3a enables functional analysis of Wnt trafficking and signaling and kinetic assessment of Wnt binding to full-length Frizzled. J Biol Chem 295, 8759–8774 (2020); published online EpubJun 26 ( 10.1074/jbc.RA120.012892). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Takada R, Mii Y, Krayukhina E, Maruyama Y, Mio K, Sasaki Y, Shinkawa T, Pack CG, Sako Y, Sato C, Uchiyama S, Takada S, Assembly of protein complexes restricts diffusion of Wnt3a proteins. Commun Biol 1, 165 (2018) 10.1038/s42003-018-0172-x). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Holzer T, Liffers K, Rahm K, Trageser B, Ozbek S, Gradl D, Live imaging of active fluorophore labelled Wnt proteins. FEBS Lett 586, 1638–1644 (2012); published online EpubJun 4 ( 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.04.035). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Galli LM, Santana F, Apollon C, Szabo LA, Ngo K, Burrus LW, Direct visualization of the Wntless-induced redistribution of WNT1 in developing chick embryos. Dev Biol 439, 53–64 (2018); published online EpubJul 15 ( 10.1016/j.ydbio.2018.04.025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wallkamm V, Dorlich R, Rahm K, Klessing T, Nienhaus GU, Wedlich D, Gradl D, Live imaging of Xwnt5A-ROR2 complexes. PLOS ONE 9, e109428 (2014) 10.1371/journal.pone.0109428). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rhinn M, Lun K, Luz M, Werner M, Brand M, Positioning of the midbrain-hindbrain boundary organizer through global posteriorization of the neuroectoderm mediated by Wnt8 signaling. Development 132, 1261–1272 (2005); published online EpubMar ( 10.1242/dev.01685). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shinoda H, Ma Y, Nakashima R, Sakurai K, Matsuda T, Nagai T, Acid-Tolerant Monomeric GFP from Olindias formosa. Cell Chem Biol 25, 330–338 e337 (2018); published online EpubMar 15 ( 10.1016/j.chembiol.2017.12.005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huang F, Khvorova A, Marshall W, Sorkin A, Analysis of clathrin-mediated endocytosis of epidermal growth factor receptor by RNA interference. J Biol Chem 279, 16657–16661 (2004); published online EpubApr 16 ( 10.1074/jbc.C400046200). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sigismund S, Argenzio E, Tosoni D, Cavallaro E, Polo S, Di Fiore PP, Clathrin-mediated internalization is essential for sustained EGFR signaling but dispensable for degradation. Dev Cell 15, 209–219 (2008); published online EpubAug ( 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.06.012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pascolutti R, Algisi V, Conte A, Raimondi A, Pasham M, Upadhyayula S, Gaudin R, Maritzen T, Barbieri E, Caldieri G, Tordonato C, Confalonieri S, Freddi S, Malabarba MG, Maspero E, Polo S, Tacchetti C, Haucke V, Kirchhausen T, Di Fiore PP, Sigismund S, Molecularly Distinct Clathrin-Coated Pits Differentially Impact EGFR Fate and Signaling. Cell Rep 27, 3049–3061 e3046 (2019); published online EpubJun 4 ( 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.05.017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Villasenor R, Nonaka H, Del Conte-Zerial P, Kalaidzidis Y, Zerial M, Regulation of EGFR signal transduction by analogue-to-digital conversion in endosomes. Elife 4, (2015); published online EpubFeb 4 ( 10.7554/eLife.06156). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brankatschk B, Wichert SP, Johnson SD, Schaad O, Rossner MJ, Gruenberg J, Regulation of the EGF transcriptional response by endocytic sorting. Sci Signal 5, ra21 (2012); published online EpubMar 13 ( 10.1126/scisignal.2002351). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sigismund S, Algisi V, Nappo G, Conte A, Pascolutti R, Cuomo A, Bonaldi T, Argenzio E, Verhoef LG, Maspero E, Bianchi F, Capuani F, Ciliberto A, Polo S, Di Fiore PP, Threshold-controlled ubiquitination of the EGFR directs receptor fate. EMBO J 32, 2140–2157 (2013); published online EpubJul 31 ( 10.1038/emboj.2013.149). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rennick JJ, Johnston APR, Parton RG, Key principles and methods for studying the endocytosis of biological and nanoparticle therapeutics. Nat Nanotechnol 16, 266–276 (2021); published online EpubMar ( 10.1038/s41565-021-00858-8). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dutta D, Williamson CD, Cole NB, Donaldson JG, Pitstop 2 is a potent inhibitor of clathrin-independent endocytosis. PLOS ONE 7, e45799 (2012) 10.1371/journal.pone.0045799). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nichols B, Caveosomes and endocytosis of lipid rafts. J Cell Sci 116, 4707–4714 (2003); published online EpubDec 1 ( 10.1242/jcs.00840). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.van Noort M, Meeldijk J, van der Zee R, Destree O, Clevers H, Wnt signaling controls the phosphorylation status of beta-catenin. J Biol Chem 277, 17901–17905 (2002); published online EpubMay 17 ( 10.1074/jbc.M111635200). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Staal FJ, van Noort M, Strous GJ, Clevers HC, Wnt signals are transmitted through N-terminally dephosphorylated beta-catenin. EMBO Rep 3, 63–68 (2002); published online EpubJan ( 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pinson KI, Brennan J, Monkley S, Avery BJ, Skarnes WC, An LDL-receptor-related protein mediates Wnt signalling in mice. Nature 407, 535–538 (2000); published online EpubSep 28 ( 10.1038/35035124). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tamai K, Semenov M, Kato Y, Spokony R, Liu C, Katsuyama Y, Hess F, Saint-Jeannet JP, He X, LDL-receptor-related proteins in Wnt signal transduction. Nature 407, 530–535 (2000); published online EpubSep 28 ( 10.1038/35035117). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Davidson G, Wu W, Shen J, Bilic J, Fenger U, Stannek P, Glinka A, Niehrs C, Casein kinase 1 gamma couples Wnt receptor activation to cytoplasmic signal transduction. Nature 438, 867–872 (2005); published online EpubDec 8 ( 10.1038/nature04170). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bernatik O, Paclikova P, Kotrbova A, Bryja V, Cajanek L, Primary Cilia Formation Does Not Rely on WNT/beta-Catenin Signaling. Front Cell Dev Biol 9, 623753 (2021) 10.3389/fcell.2021.623753). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Benmerah A, Gagnon J, Begue B, Megarbane B, Dautry-Varsat A, Cerf-Bensussan N, The tyrosine kinase substrate eps15 is constitutively associated with the plasma membrane adaptor AP-2. J Cell Biol 131, 1831–1838 (1995); published online EpubDec ( 10.1083/jcb.131.6.1831). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Parachoniak CA, Park M, Distinct Recruitment of Eps15 via Its Coiled-coil Domain Is Required For Efficient Down-regulation of the Met Receptor Tyrosine Kinase. Journal of Biological Chemistry 284, 8382–8394 (2009) 10.1074/jbc.m807607200). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Carbone R, Fre S, Iannolo G, Belleudi F, Mancini P, Pelicci PG, Torrisi MR, Di Fiore PP, eps15 and eps15R are essential components of the endocytic pathway. Cancer Res 57, 5498–5504 (1997); published online EpubDec 15 ( [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vercauteren D, Vandenbroucke RE, Jones AT, Rejman J, Demeester J, De Smedt SC, Sanders NN, Braeckmans K, The use of inhibitors to study endocytic pathways of gene carriers: optimization and pitfalls. Mol Ther 18, 561–569 (2010); published online EpubMar ( 10.1038/mt.2009.281). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kim I, Pan W, Jones SA, Zhang Y, Zhuang X, Wu D, Clathrin and AP2 are required for PtdIns(4,5)P2-mediated formation of LRP6 signalosomes. J Cell Biol 200, 419–428 (2013); published online EpubFeb 18 ( 10.1083/jcb.201206096). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Liu CC, Kanekiyo T, Roth B, Bu G, Tyrosine-based signal mediates LRP6 receptor endocytosis and desensitization of Wnt/beta-catenin pathway signaling. J Biol Chem 289, 27562–27570 (2014); published online EpubOct 3 ( 10.1074/jbc.M113.533927). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Agajanian MJ, Walker MP, Axtman AD, Ruela-de-Sousa RR, Serafin DS, Rabinowitz AD, Graham DM, Ryan MB, Tamir T, Nakamichi Y, Gammons MV, Bennett JM, Counago RM, Drewry DH, Elkins JM, Gileadi C, Gileadi O, Godoi PH, Kapadia N, Muller S, Santiago AS, Sorrell FJ, Wells CI, Fedorov O, Willson TM, Zuercher WJ, Major MB, WNT Activates the AAK1 Kinase to Promote Clathrin-Mediated Endocytosis of LRP6 and Establish a Negative Feedback Loop. Cell Rep 26, 79–93 e78 (2019); published online EpubJan 2 ( 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.12.023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cruciat CM, Ohkawara B, Acebron SP, Karaulanov E, Reinhard C, Ingelfinger D, Boutros M, Niehrs C, Requirement of prorenin receptor and vacuolar H+-ATPase-mediated acidification for Wnt signaling. Science 327, 459–463 (2010); published online EpubJan 22 ( 10.1126/science.1179802). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tomas A, Futter CE, Eden ER, EGF receptor trafficking: consequences for signaling and cancer. Trends Cell Biol 24, 26–34 (2014); published online EpubJan ( 10.1016/j.tcb.2013.11.002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhou Y, Nathans J, Gpr124 controls CNS angiogenesis and blood-brain barrier integrity by promoting ligand-specific canonical wnt signaling. Dev Cell 31, 248–256 (2014); published online EpubOct 27 ( 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.08.018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Vanhollebeke B, Stone OA, Bostaille N, Cho C, Zhou Y, Maquet E, Gauquier A, Cabochette P, Fukuhara S, Mochizuki N, Nathans J, Stainier DY, Tip cell-specific requirement for an atypical Gpr124- and Reck-dependent Wnt/beta-catenin pathway during brain angiogenesis. Elife 4, (2015); published online EpubJun 8 ( 10.7554/eLife.06489). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cho C, Smallwood PM, Nathans J, Reck and Gpr124 Are Essential Receptor Cofactors for Wnt7a/Wnt7b-Specific Signaling in Mammalian CNS Angiogenesis and Blood-Brain Barrier Regulation. Neuron 95, 1221–1225 (2017); published online EpubAug 30 ( 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.08.032). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Martin M, Vermeiren S, Bostaille N, Eubelen M, Spitzer D, Vermeersch M, Profaci CP, Pozuelo E, Toussay X, Raman-Nair J, Tebabi P, America M, De Groote A, Sanderson LE, Cabochette P, Germano RFV, Torres D, Boutry S, de Kerchove d'Exaerde A, Bellefroid EJ, Phoenix TN, Devraj K, Lacoste B, Daneman R, Liebner S, Vanhollebeke B, Engineered Wnt ligands enable blood-brain barrier repair in neurological disorders. Science 375, eabm4459 (2022); published online EpubFeb 18 ( 10.1126/science.abm4459). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Eubelen M, Bostaille N, Cabochette P, Gauquier A, Tebabi P, Dumitru AC, Koehler M, Gut P, Alsteens D, Stainier DYR, Garcia-Pino A, Vanhollebeke B, A molecular mechanism for Wnt ligand-specific signaling. Science 361, (2018); published online EpubAug 17 ( 10.1126/science.aat1178). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jao LE, Wente SR, Chen W, Efficient multiplex biallelic zebrafish genome editing using a CRISPR nuclease system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110, 13904–13909 (2013); published online EpubAug 20 ( 10.1073/pnas.1308335110). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yusa K, Zhou L, Li MA, Bradley A, Craig NL, A hyperactive piggyBac transposase for mammalian applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108, 1531–1536 (2011); published online EpubJan 25 ( 10.1073/pnas.1008322108). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Willert K, Brown JD, Danenberg E, Duncan AW, Weissman IL, Reya T, Yates JR 3rd, Nusse R, Wnt proteins are lipid-modified and can act as stem cell growth factors. Nature 423, 448–452 (2003); published online EpubMay 22 ( 10.1038/nature01611). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Laemmli UK, Beguin F, Gujer-Kellenberger G, A factor preventing the major head protein of bacteriophage T4 from random aggregation. J Mol Biol 47, 69–85 (1970); published online EpubJan 14 ( 10.1016/0022-2836(70)90402-x). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Schefe JH, Lehmann KE, Buschmann IR, Unger T, Funke-Kaiser H, Quantitative real-time RT-PCR data analysis: current concepts and the novel "gene expression's CT difference" formula. J Mol Med (Berl) 84, 901–910 (2006); published online EpubNov ( 10.1007/s00109-006-0097-6). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Clements WK, Kim AD, Ong KG, Moore JC, Lawson ND, Traver D, A somitic Wnt16/Notch pathway specifies haematopoietic stem cells. Nature 474, 220–224 (2011); published online EpubJun 8 ( 10.1038/nature10107). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kobayashi I, Kobayashi-Sun J, Kim AD, Pouget C, Fujita N, Suda T, Traver D, Jam1a-Jam2a interactions regulate haematopoietic stem cell fate through Notch signalling. Nature 512, 319–323 (2014); published online EpubAug 21 ( 10.1038/nature13623). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]