Structured Abstract

Aims:

To determine contemporary incidence rates and risk factors for major adverse events in youth-onset T1D and T2D.

Methods:

Participant interviews were conducted once during in-person visits from 2018–2019 in SEARCH (T1D: N=564; T2D: N=149) and semi-annually from 2014–2020 in TODAY (T2D: N=495). Outcomes were adjudicated using harmonized, predetermined, standardized criteria.

Results:

Incidence rates (events per 10,000 person-years) among T1D participants were: 10.9 ophthalmologic; 0 kidney; 11.1 nerve, 3.1 cardiac; 3.1 peripheral vascular; 1.6 cerebrovascular; and 15.6 gastrointestinal events. Among T2D participants, rates were: 40.0 ophthalmologic; 6.2 kidney; 21.2 nerve; 21.2 cardiac; 10.0 peripheral vascular; 5.0 cerebrovascular and 42.8 gastrointestinal events. Despite similar mean diabetes duration, complications were higher in youth with T2D than T1D: 2.5-fold higher for microvascular, 4.0-fold higher for macrovascular, and 2.7-fold higher for gastrointestinal disease. Univariate logistic regression analyses in T1D associated age at diagnosis, female sex, HbA1c and mean arterial pressure (MAP) with microvascular events. In youth-onset T2D, composite microvascular events associated positively with MAP and negatively with BMI, however composite macrovascular events associated solely with MAP.

Conclusions:

In youth-onset diabetes, end-organ events were infrequent but did occur before 15 years diabetes duration. Rates were higher and had different risk factors in T2D versus T1D.

Keywords: Youth onset, diabetes, vascular complications, TODAY Study, SEARCH Study

1. Introduction

The rising prevalence of both type 1 (T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) in youth[1] raises particular concern for increasing rates of complications at younger ages, given the longer potential time exposed to the diabetic milieu. From the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study, the prevalence of T2D in youth (10–19 years) more than doubled between 2002 and 2018 with an adjusted annual increase in cases of 2.0% and 5.3% per year, respectively for T1D and T2D.[2] Presuming that the increases in incidence of T2D in youth persist, it is estimated that the prevalence of T2D in youth will increase by 700% by the year 2060.[3] Rates of preclinical and early complications in this population have been extensively studied,[4–8] with reports indicating higher rates of early complications in T2D versus T1D[4]. Reports of advanced micro- and macrovascular complications of diabetes are well described in T1D cohorts with long duration diabetes.[9–11] In youth with T2D, reports of advanced complications focus primarily on kidney disease among Native American Youth.[8, 12–14] No study has reported comprehensive rates of major adverse events early in the course of youth-onset T1D and T2D.

Risk factors for advanced micro- and macrovascular events vary by diabetes type. Hyperglycemia is the strongest singular risk factor for advanced complications in T1D. Other risk factors include diabetes duration, elevated blood pressure, and dyslipidemia.[10, 11, 15] In adults with T2D, glycemic control also has been implicated in the development of advanced microvascular disease, but significantly less so for macrovascular complications.[16] Hypertension plays a major role in development of advanced micro- and macrovascular disease in adult-onset T2D[17], as does overweight and obesity.[18] In the Treatment Options for Type 2 Diabetes in Adolescents and Youth (TODAY) study diabetes-related complications were seen in 60% by 10 years on average in participants diagnosed with T2D in their youth with higher HbA1c and lower insulin sensitivity in addition to hypertension and dyslipidemia predicting risk for multiple microvascular complications [19]. While some predictors of preclinical and early microvascular complications in diabetes have been established, it is not clear if differences exist in the predictors of advanced complications in youth-onset T1D versus T2D.

Both the SEARCH and TODAY studies offer unique opportunities to assess rates of advanced diabetes-associated complications in youth-onset T1D and T2D. In addition to classic micro- and macrovascular complications, we sought to compare rates of medical events related to inflammation and insulin resistance, including venous thrombosis, pancreatitis, gallbladder disease, and cirrhosis. The overall objective was to compare complication rates between youth-onset T1D and T2D, to potentially elucidate differences that exist in the care and outcomes of this growing population.

2. Subjects, Materials and Methods

2.1. Populations:

The SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth longitudinal observational study population and protocol have been described previously.[20] In brief, individuals with newly-diagnosed T1D or T2D prior to age 20 years were identified via a population-based registry network encompassing 5.5 million youth from five sites in the US. Diabetes type was defined according to the clinical documentation within 6 months of diagnosis. Participants diagnosed during the years 2002–2006, 2008 and 2012 were invited to an in-person visit (mean diabetes duration 9.9 months at baseline) and follow up visits approximately every 5 years thereafter, starting when diabetes duration accrued to >5 years and participants were at least 10 years of age. The sampling strategy for T1D was adjusted to oversample minority participants during the most recent visits, which occurred between 2015–2019. Height, weight, hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), and systolic and diastolic blood pressure (SBP and DBP) were measured at in-person study visits using standardized study protocols.

The TODAY population and protocol (www.clinicaltrials.gov: NCT0008132) have been previously published.[21] Briefly, at clinical trial entry participants (N=699) at 15 centers across the US were 10 to <18 years old with <2 years duration of T2D, based on the American Diabetes Association 2002 criteria,[21] with body mass index (BMI) ≥85th percentile, fasting C-peptide > 0.6mmol/L, and negative pancreatic antibodies. Participants were randomized to metformin monotherapy, metformin plus rosiglitazone, or metformin plus an intensive lifestyle intervention and followed for an average of 3.9 (range 2 to 6) years. In 2011, 572 (82%) participants enrolled in a longitudinal observational follow-up study (TODAY2) conducted in two phases. Between 2011–2014, participants received all diabetes care from the study and were treated with metformin with or without insulin to maintain glycemic control. From 2014–2020, 518 participants transitioned to a fully observational study with annual study visits and medical management by their healthcare providers. The combined phases of TODAY provide an average length of follow-up of 10.2 years. Both studies collected self-reported race and ethnicity due to the importance of race and ethnicity in the risk for youth-onset diabetes and its complications. Categories of race and ethnicity were collapsed to non-Hispanic White, Black, Hispanic and ‘Other’ due to small sample sizes in the categories comprising ‘Other’. The studies were approved by institutional review boards at all participating centers, and all participants and parents or guardians provided written informed assent and/or consent as appropriate for age and local guidelines.

2.2. Clinical Event Collection and Adjudication:

Participants were interviewed to assess occurrence of ophthalmologic, kidney, neuropathy, cardiac, and peripheral and cerebrovascular events of interest using a harmonized questionnaire that was administered verbally using lay language by study staff (questionnaires available in Supplementary Materials). Interviewers were allowed to clarify questions if there was confusion expressed by a participant. Screening interviews were conducted initially by the TODAY Study during semi-annual visits, beginning 2014 through 2020. The SEARCH Study adopted a replica of this approach and conducted interviews at the most recent in-person visit (2018–2019). In addition to the questions posed by TODAY, the SEARCH Study included assessment of acute kidney injury (AKI), nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Participants who endorsed a potential clinical event of interest were asked to consent for release of information for medical records to be obtained. Adjudication of clinical events was conducted by at least two clinical investigators (within each study) via medical record review, using predetermined, standardized and harmonized criteria (available in supplemental materials). Discrepancy in adjudication was resolved via discussion.

2.3. Statistical Methods:

SEARCH participants who completed an in-person study visit after May 1, 2018 were included in the analysis. For TODAY, all participants who completed a final study visit and were not classified as having Maturity Onset Diabetes of the Young were included in the analysis. Descriptive statistics for both studies included data from the last observational study visit, stratifying by diabetes type and study to describe the sample being observed.. To compare the characteristics of the T2D participants between the two studies, a t-test, Kruskal-Wallis, or Chi-square test was used depending on the distributions. The number of person-years of observation is calculated from the time of diagnosis of diabetes until the date of the event of interest indicated by the medical records. For those not experiencing an event, the date of the last follow-up was used. The occurrence rate for each event was calculated as total events divided by person-years and is presented as the rate per 10,000 person-years. The total number of participants experiencing an event, number of person-years of observation, and occurrence rate, are summarized by diabetes type and event type. Kaplan-Meier plots were created for each diabetes type, stratifying by microvascular versus macrovascular events.

Cox proportional hazards models were used to identify significant associations of participant characteristics with the time to event choosing potential confounders and mediators based on the literature and clinical reasoning. Due to a limited number of events, forward selection was performed using variables felt to be of high clinical/scientific relevance, adding the most significant predictor with p-value <0.1 to create the final multivariable models. Variables assessed for entry into the models included age at diagnosis, sex (female/male), HbA1c, mean arterial pressure (MAP), LDL, BMI and log transformed triglycerides. Additionally, race (Non-Hispanic white/Other) was included for T1D and race (Non-Hispanic white/Non-Hispanic black/Other) and study (TODAY/SEARCH) were included for T2D. BMI was used as a categorical measure in the models for T2D because of an observed non-linear association with the occurrence of events.

Data and Resource Availability:

Data from the ‘SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth’ and ‘Treatment Options for Type 2 Diabetes in Adolescents & Youth Long Term Follow-Up’ are available for request at the NIDDK Central Repository (NIDDK-CR) website, Resources for Research (R4R):

https://repository.niddk.nih.gov/

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Cohorts

Clinical event screening interviews were conducted in 713 participants in SEARCH (T1D N=564; T2D N=149) and in 495 T2D participants in TODAY. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of participants are displayed in Table 1, stratifying by study and diabetes type. In general, SEARCH participants with T1D differed from T2D participants of both studies with respect to: younger age at diabetes onset, less preponderance of females and racial/ethnic minorities, but greater preponderance of private insurance and higher household income. Diabetes duration and hemoglobin A1c were similar between the SEARCH T1D and both T2D groups. In comparing the individuals with T2D from TODAY and SEARCH, participants in TODAY were younger at diagnosis (13.2±2.1 years vs 14.3±2.7 years), had longer duration of diabetes (13.3±1.8 years vs 10.0±3.8 years), and were more likely to report use of metformin, statin therapy, and ACEI/ARB. These differences are likely driven by protocol design, in that TODAY was a clinical trial with metformin designated as primary diabetes treatment along with ACEI/ARB and statins as protocolized treatments for hypertension, albuminuria and dyslipidemia.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of participants from TODAY and SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth (SEARCH 4 cohort visit) who underwent screening and adjudication of diabetes related medical events.

| SEARCH T1D N=564 | SEARCH T2D N=149 | TODAY T2D N=495 | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age at diabetes onset (years), mean(sd) | 9.7 (4.4) | 14.3 (2.7) | 13.2 (2.1)* |

|

| |||

| Age at last visit (years), mean(sd) | 21.1 (5.2) | 24.3 (4.4) | 26.5 (2.7) |

|

| |||

| Duration of Diabetes (years), mean(sd) | 11.4 (3.7) | 10.0 (3.8) | 13.3 (1.8)* |

|

| |||

| Female Sex, N(%) | 305 (54.1%) | 98 (65.8%) | 324 (65.5%) |

|

| |||

| Race/Ethnicity, N(%) | * | ||

|

| |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 334 (59.2%) | 23 (15.4%) | 94 (19.0%) |

|

| |||

| Black | 98 (17.4%) | 74 (49.7%) | 174 (35.2%) |

|

| |||

| Hispanic | 107 (19.0%) | 40 (26.8%) | 188 (38.0%) |

|

| |||

| Other | 25 (4.4%) | 12 (8.1%) | 39 (7.9%) |

|

| |||

| Insurance, N(%) | |||

|

| |||

| Private | 399 (70.7%) | 54 (36.2%) | 163 (32.9%) |

|

| |||

| Medicaid/Public | 106 (18.8%) | 53 (35.6%) | 207 (41.8%) |

|

| |||

| None | 17 (3.0%) | 23 (15.4%) | 61 (12.3%) |

|

| |||

| Other | 34 (6.0%) | 13 (8.7%) | 31 (6.3%) |

|

| |||

| Unknown | 8 (1.4%) | 6 (4.0%) | 33 (6.7%) |

|

| |||

| Household Income, N(%) | * | ||

|

| |||

| <$25K | 82 (14.5%) | 43 (28.9%) | 299 (60.4%) |

|

| |||

| $25–49K | 102 (18.1%) | 27 (18.1%) | 139 (28.1%) |

|

| |||

| $50–74K | 65 (11.5%) | 6 (4.0%) | 35 (7.1%) |

|

| |||

| $75K+ | 168 (29.8%) | 5 (3.4%) | 5 (1.0%) |

|

| |||

| DK/Ref | 147 (26.1%) | 68 (45.6%) | 17 (3.4%) |

|

| |||

| Participant Education, N(%) | * | ||

|

| |||

| Less than HS gr | 194 (34.6%) | 27 (18.4%) | 60 (12.1%) |

|

| |||

| HS graduate | 122 (21.7%) | 56 (38.1%) | 311 (62.8%) |

|

| |||

| Some College/Associates Degree | 169 (30.1%) | 54 (36.7%) | 49 (9.9%) |

|

| |||

| Bachelor degree or higher | 76 (13.5%) | 10 (6.8%) | 75 (15.2%) |

|

| |||

| Unknown | 3 | 2 | 0 |

|

| |||

| Medication Regimen, N(%) | * | ||

|

| |||

| Metformin only | 1 (0.2%) | 11 (7.9%) | 92 (18.6%) |

|

| |||

| Insulin only | 540 (95.7%) | 47 (33.8%) | 107 (21.6%) |

|

| |||

| Insulin + Something else | 19 (3.4%) | 38 (27.3%) | 154 (31.1%) |

|

| |||

| Other Oral | 1 (0.2%) | 7 (5.0%) | 23 (4.6%) |

|

| |||

| None | 3 (0.5%) | 36 (25.9%) | 119 (24.0%) |

|

| |||

| Unknown | 0 | 10 | 0 |

|

| |||

| HbA1c (%), mean(sd) | 9.1 (2.2) | 9.5 (2.9) | 9.4 (2.8) |

| Mmol/mol, mean(sd) | 76 (24) | 80 (32) | 79 (31) |

|

| |||

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2), mean(sd) | 25.6 (5.4) | 36.4 (9.3) | 36.0 (8.4) |

|

| |||

| < 25 | 302 (53.5%) | 11 (7.4%) | 25 (5.3%) |

|

| |||

| 25–30 | 161 (28.5%) | 23 (15.4%) | 85 (17.9%) |

|

| |||

| 30–40 | 90 (16.0%) | 73 (49.0%) | 235 (49.6%) |

|

| |||

| 40 + | 11 (2.0%) | 42 (28.2%) | 129 (27.2%) |

|

| |||

| Systolic Blood Pressure, mean(sd) | 110.1 (11.7) | 123.5 (18.8) | 122.3 (14.9) |

|

| |||

| Diastolic Blood Pressure, mean(sd) | 70.7 (9.2) | 79.7 (13.6) | 76.7 (11.2)* |

|

| |||

| Mean Arterial Pressure, mean(sd) | 83.9 (9.0) | 94.3 (14.5) | 91.9 (11.8) |

|

| |||

| LDL (mg/dl), mean(sd) | 105.9 (33.1) | 108.4 (31.6) | 102.7 (33.5) |

|

| |||

| Triglycerides (mg/dl), median (IQR) | 78.0 (59.0; 109.5) | 108.0 (78.0; 171.0) | 115.0 (79.0; 172.0) |

|

| |||

| ACEI/ARB | * | ||

|

| |||

| Yes | 29 (5.4%) | 14 (10.8%) | 146 (29.5%) |

|

| |||

| No | 506 (94.6%) | 116 (89.2%) | 349 (70.5%) |

|

| |||

| Unknown | 29 | 19 | 0 |

|

| |||

| Statin use | * | ||

|

| |||

| Yes | 15 (2.8%) | 8 (6.2%) | 72 (14.5%) |

|

| |||

| No | 520 (97.2%) | 122 (93.8%) | 423 (85.5%) |

|

| |||

| Unknown | 29 | 19 | 0 |

p<0.05 comparing SEARCH type 2 and TODAY type 2 (t-test, Kruskal-Wallis, or Chi-square test)

3.2. Complication Rates

All event rates were higher in individuals with youth-onset T2D than youth-onset T1D (Table 2). Microvascular events (eye, kidney, nerve) were 2.6-times higher in the youth with T2D (56.5 versus 21.9 events per 10,000 person-years for T2D and T1D, respectively). The rate of any macrovascular event was 4-times higher in the participants with T2D as compared to T1D (32.5 versus 7.8 events per 10,000 person-years, respectively). Thus, the rates of combined micro- and macrovascular complications were 2.8-times higher in the individuals with T2D versus T1D (82.3 versus 29.8 events per 10,000 person-years, respectively).

Table 2.

Prevalence of adjudicated diagnoses and procedures in participants from the TODAY and SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Studies. Rate is calculated per 10,000 person years.

| Type 1 Diabetes N=546 | Type 2 Diabetes N=644 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects with an event | Person Years | Rate | Subjects with an event | Person Years | Rate | |

| Ophthalmologic Diagnosis | ||||||

| PDR | 2 | 6428 | 3.11 | 20 | 8047 | 24.9 |

| Vitreous Hemorrhage | 1 | 6429 | 1.6 | 7 | 8071 | 8.7 |

| Macular Edema | 4 | 6425 | 6.2 | 17 | 8048 | 21.1 |

| Cataracts | 6 | 6408 | 9.4 | 10 | 8057 | 12.4 |

| Glaucoma | 2 | 6429 | 3.1 | 6 | 8062 | 7.4 |

| Blindness | 1 | 6429 | 1.6 | 1 | 8078 | 1.2 |

| Any Ophthalmologic event | 7 | 6405 | 10.9 | 32 | 8008 | 40.0 |

| Kidney Diagnosis | ||||||

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 0 | 6431 | 0.0 | 5 | 8062 | 6.2 |

| End-stage Kidney Disease | 0 | 6431 | 0.0 | 4 | 8070 | 5.0 |

| Any Kidney Diagnosis | 0 | 6431 | 0.0 | 5 | 8062 | 6.2 |

| Neuropathy Diagnosis | ||||||

| Peripheral Neuropathy | 2 | 6426 | 3.1 | 10 | 8055 | 12.4 |

| Autonomic Neuropathy | 5 | 6423 | 7.8 | 7 | 8060 | 8.7 |

| Mononeuropathy | 0 | 6431 | 0.0 | 1 | 8074 | 1.2 |

| Any Neuropathy event | 7 | 6334 | 11.1 | 17 | 8022 | 21.2 |

| Any Microvascular event | 14 | 6405 | 21.9 | 45 | 7958 | 56.5 |

| Cardiac Diagnosis | ||||||

| Arrhythmia | 1 | 6428 | 1.6 | 10 | 8038 | 12.4 |

| Myocardial Infarction | 1 | 6424 | 1.6 | 4 | 8073 | 5.0 |

| CAD without MI | 0 | 6431 | 0.0 | 3 | 8073 | 3.7 |

| CHF | 0 | 6431 | 0.0 | 6 | 8068 | 7.4 |

| LV systolic dysfunction | 0 | 6431 | 0.0 | 6 | 8067 | 7.4 |

| Any Cardiac Event | 2 | 6422 | 3.1 | 17 | 8026 | 21.2 |

| Vascular Diagnosis or Procedures | ||||||

| Peripheral Artery Disease | 0 | 6431 | 0.0 | 1 | 8077 | 1.2 |

| Renal Artery Disease | 0 | 6431 | 0.0 | 0 | 8078 | 0.0 |

| Amputation | 0 | 6431 | 0.0 | 2 | 8074 | 2.5 |

| Arterial Bypass or Stent Placement | 0 | 6431 | 0.0 | 0 | 8078 | 0.0 |

| DVT | 2 | 6410 | 3.1 | 6 | 8059 | 7.5 |

| Any Vascular Event or procedure | 2 | 6410 | 3.1 | 8 | 8054 | 9.9 |

| Cerebrovascular Diagnosis | ||||||

| Stroke | 1 | 6425 | 1.6 | 3 | 8070 | 3.7 |

| Transient Ischemic Attack | 0 | 6431 | 0.0 | 1 | 8074 | 1.2 |

| Cerebrovascular Disease without stroke or TIA | 0 | 6431 | 0.0 | 0 | 8078 | 0.0 |

| Any Cerebrovascular Event | 1 | 6425 | 1.6 | 4 | 8065 | 5.0 |

| Any Macrovascular event | 5 | 6395 | 7.8 | 26 | 7995 | 32.5 |

| Any Micro/Macrovascular event | 19 | 6370 | 29.8 | 65 | 7894 | 82.3 |

| Gastrointestinal Diagnosis | ||||||

| Pancreatitis | 4 | 6410 | 6.2 | 9 | 8046 | 11.2 |

| Gallbladder Disease | 6 | 6417 | 9.4 | 28 | 7971 | 35.1 |

| Cirrhosis | 0 | 6431 | 0.0 | 0 | 8078 | 0.0 |

| Any Gastrointestinal Event | 10 | 6396 | 15.6 | 34 | 7949 | 42.8 |

Participants with T2D not only had higher rates of total microvascular complications than T1D but also higher rates within each organ system. The overall rates of eye disease were 3.7-times higher in the participants with youth-onset T2D versus T1D (40.0 versus 10.9 events per 10,000 person-years). Rates of proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR), vitreous hemorrhage, macular edema, and glaucoma were all 2–8 times higher in T2D, while the rates of cataracts and blindness were similar between the groups. Neither chronic kidney disease (CKD) nor end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) was reported in the individuals with youth-onset T1D while the overall rate of CKD in the individuals with youth-onset T2D was 6.2 events per 10,000 person-years. Acute kidney injury, which was only assessed in the SEARCH population, was the only adverse event which was more common among T1D versus T2D (12.5 versus 6.7 per 10,000 person- years, respectively). Rates of neuropathy were higher in individuals with youth-onset T2D than T1D (21.2 versus 11.1 events per 10,000 person-years, respectively).

In comparing macrovascular disease outcomes, individuals with youth-onset T2D had markedly higher rates of cardiac, vascular, and cerebrovascular events. Composite cardiac events were 6.8-times higher in T2D than T1D. Arrhythmia rates were 7.8 times higher and myocardial infarction (MI) rates 3.1 times higher in youth-onset T2D versus T1D. Coronary artery disease without MI, congestive heart failure, and left ventricle systolic dysfunction were reported only in youth with T2D and not in T1D. Peripheral vascular events were 3.2-times higher in individuals with youth-onset T2D, with no reports of amputation or peripheral artery disease in T1D participants. Cerebrovascular events were 3-times higher in the individuals with T2D as compared to those with T1D.

Rates of gastrointestinal events were also higher among T2D versus T1D at rates of 42.8 versus 15.6 events per 10,000 person-years, respectively. These included both pancreatitis and gallbladder disease. No events of cirrhosis were identified in either diabetes type. There were also no cases of NASH or NAFLD among participants with T1D, but a single case among participants from SEARCH with T2D with neither assessed in TODAY.

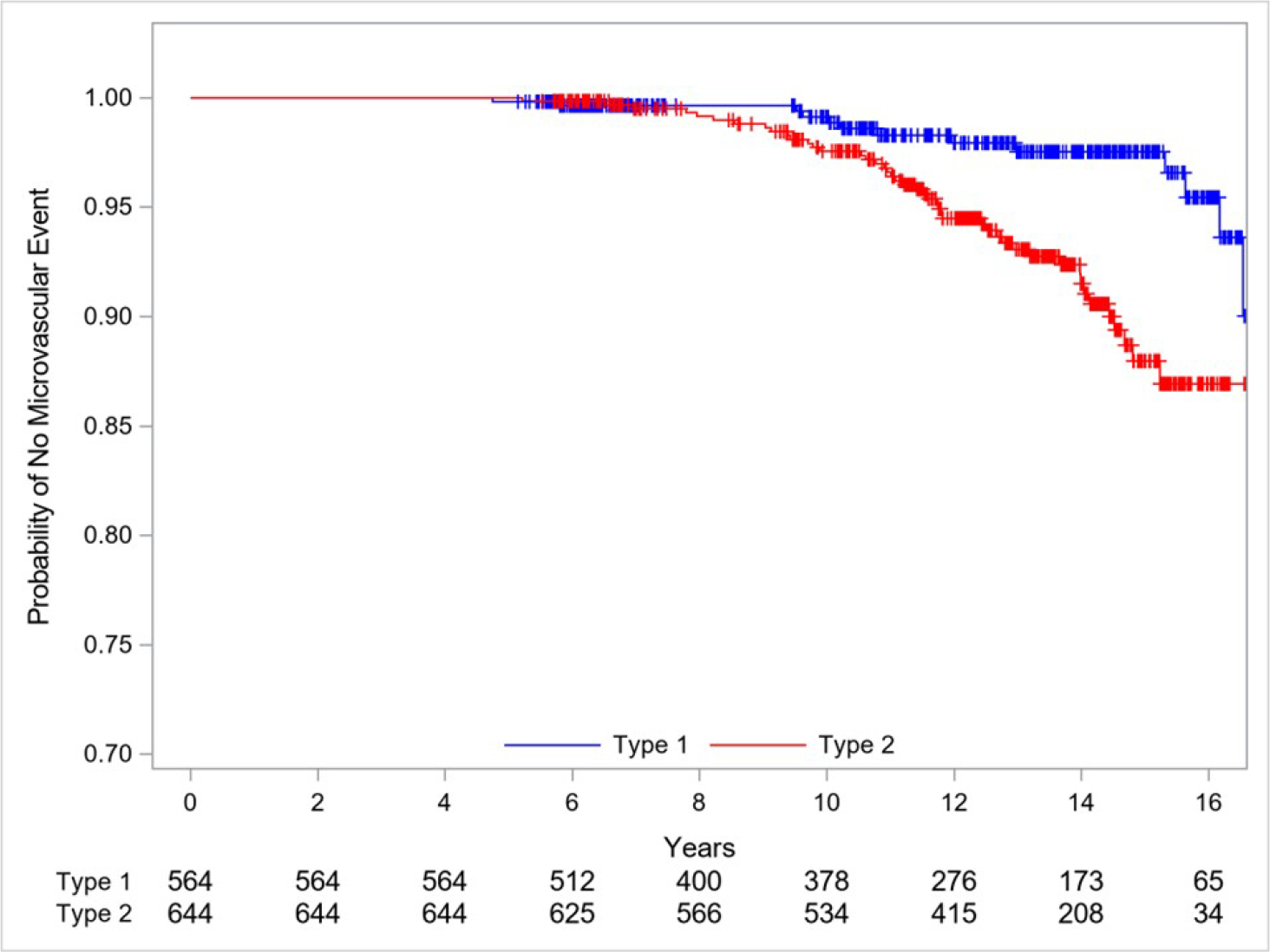

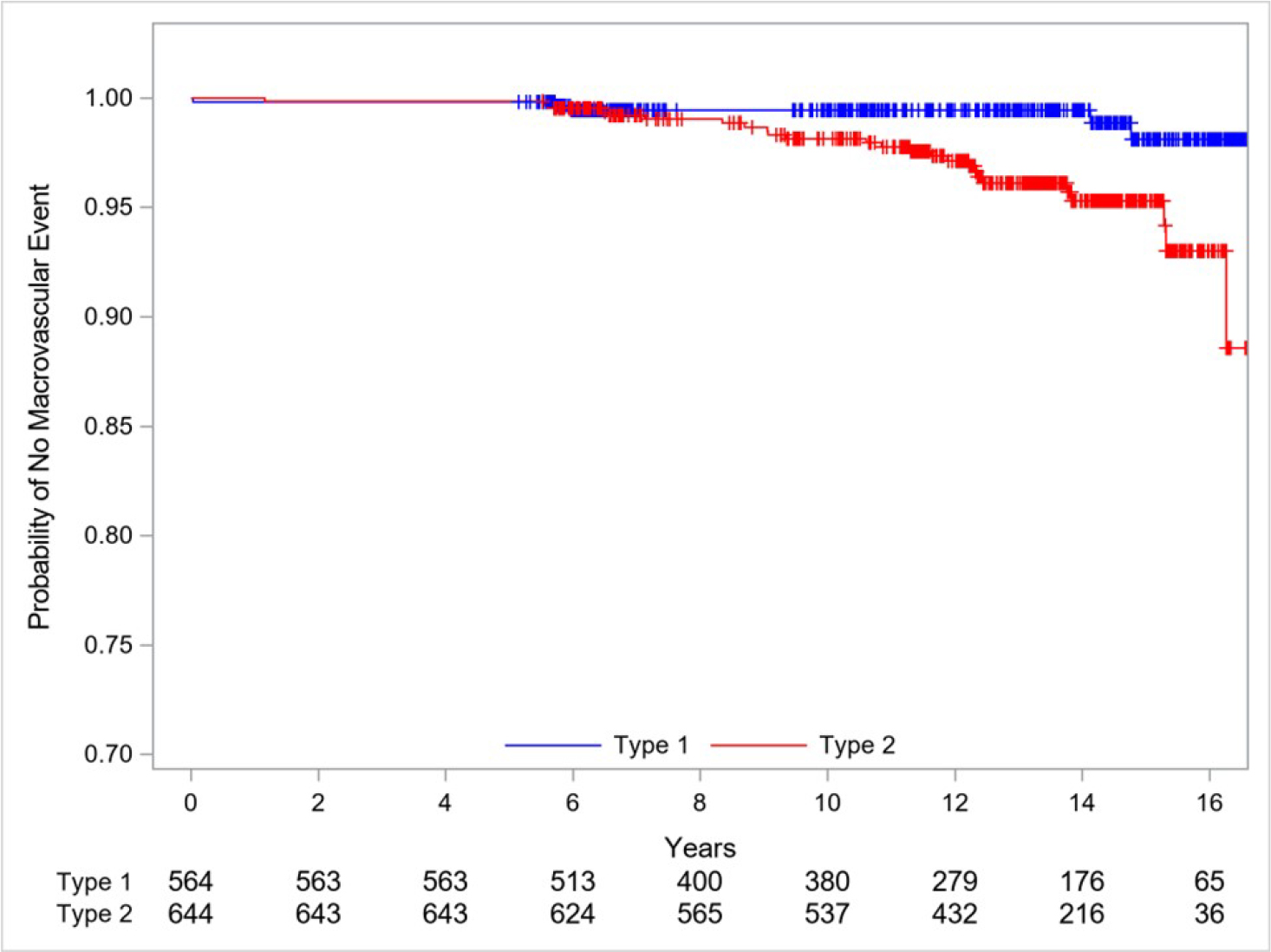

Kaplan-Meier plots assessing the duration of time between diagnosis of diabetes and vascular events demonstrated that individuals with youth-onset T2D developed complications earlier in their disease course. In Figure 1A, any micro- or macrovascular disease occurred earlier in individuals with T2D (log-rank p-value <0.0001) starting at about 8 years from diagnosis. Similar trends were seen with the individual microvascular (Figure 1B; log-rank p-value=0.001) and macrovascular endpoints (Figure 1C, log-rank p-value =0.001).

Figure 1A.

Kaplan-Meier plot showing time (years) from diabetes diagnosis to any micro- or macrovascular event (ophthalmologic, kidney, neuropathy, cardiovascular, vascular, cerebrovascular) in the SEARCH and TODAY Cohort Studies with the number at risk, stratified by diabetes type. Log-rank p-value <0.0001.

Figure 1B.

Kaplan-Meier plot showing time (years) from diabetes diagnosis to any microvascular event (ophthalmologic (excludes NPDR), kidney, neuropathy) in the SEARCH and TODAY Cohort Studies with the number at risk, stratified by diabetes type. Log-rank p-value = 0.001.

Figure 1C.

Kaplan-Meier plot showing time (years) from diabetes diagnosis to any macrovascular event (cardiovascular, vascular, cerebrovascular) in the SEARCH and TODAY Cohort Studies with the number at risk, stratified by diabetes type. Log-rank p-value = 0.001

3.3. Factors Associated with Major Adverse Events

In youth with T1D, using univariate Cox proportional hazards models, significant predictors of microvascular events included: female sex, older age at diagnosis, higher HbA1c, and higher mean arterial pressure (Table 3A). Using a multivariable, forward selection model, female sex (hazard ratio 5.23 [95% CI: 1.15–23.91] p=0.03), older age at diagnosis (hazard ratio 1.27 [95% CI: 1.10–1.48] p=0.002), and higher HbA1c (hazard ratio 1.41 [95% CI: 1.18–1.68] p=0.0001) retained significance. No significant predictors of macrovascular disease were identified.

Table 3.

Univariate Cox proportional hazards models for micro- and macrovascular clinical events in SEARCH participants with Type 1 Diabetes and Type 2 Diabetes.

| Events of Interest |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Micro-vascular Events | Macro-Vascular Events | |||||

|

| ||||||

| HR | 95% CI | p-value | HR | 95% CI | p-value | |

|

| ||||||

| Type 1 Diabetes | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Sex: Female (ref=Male) | 5.0 | (1.1, 22.4) | 0.04 | 0.6 | (0.1, 3.3) | 0.5 |

|

| ||||||

| Race: Other (ref=NHW) | 2.4 | (0.8, 7.0) | 0.14 | 1.0 | (0.2, 6.1) | 1.0 |

|

| ||||||

| Age at diagnosis (per 1 year increase) | 1.2 | (1.0, 1.3) | 0.01 | 1.1 | (0.9, 1.4) | 0.3 |

|

| ||||||

| HbA1c (per 1% increase) | 1.3 | (1.1, 1.6) | 0.001 | 1.0 | (0.7, 1.5) | 0.9 |

|

| ||||||

| MAP (per 10 mmHg increase) | 1.9 | (1.2, 2.9) | 0.01 | 0.8 | (0.3, 2.3) | 0.7 |

|

| ||||||

| Ln(Triglycerides) | 1.8 | (0.6, 5.0) | 0.3 | 0.9 | (0.2, 5.0) | 0.9 |

|

| ||||||

| LDL (per 10 mg/dL increase) | 1.1 | (0.9, 1.3) | 0.4 | 1.0 | (0.7, 1.3) | 0.8 |

|

| ||||||

| BMI (per 5 unit increase) | 0.7 | (0.4, 1.3) | 0.3 | 0.8 | (0.3, 1.9) | 0.6 |

|

| ||||||

| Number of events | 14 | 5 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Type 2 Diabetes | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Sex: Female (ref=Male) | 0.8 | (0.4, 1.5) | 0.5 | 0.6 | (0.3, 1.4) | 0.2 |

|

| ||||||

| Race (ref=NHW) | ||||||

| Black | 1.0 | (0.4, 2.3) | 0.6 | 1.7 | (0.6, 5.3) | 0.4 |

| Other | 1.4 | ((0.6, 3.1) | 1.0 | (0.3, 3.3) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Age at diagnosis (per 1 year increase) | 1.0 | (0.9, 1.2) | 0.9 | 1.1 | (0.9, 1.3) | 0.4 |

|

| ||||||

| HbA1c (per 1% increase) | 1.0 | (0.9, 1.1) | 0.7 | 1.1 | (0.9, 1.2) | 0.3 |

|

| ||||||

| MAP (per 10 mmHg increase) | 1.4 | (1.1, 1.7) | 0.0007 | 1.5 | (1.2, 1. 8) | 0.0009 |

|

| ||||||

| Ln (Triglycerides) | 0.8 | (0.5, 1.3) | 0.4 | 1.2 | (0.7, 2.1) | 0.5 |

|

| ||||||

| LDL (per 10 mg/dL increase) | 1.0 | (0.9, 1.1) | 0.7 | 0.9 | (0.8, 1.0) | 0.2 |

|

| ||||||

| BMI (per 5 unit increase) | 0.7 | (0.6, 0.9) | 0.007 | 1.1 | (0.9, 1.3) | 0.4 |

|

| ||||||

| Study: TODAY (ref=SEARCH) | 2.3 | (0.7, 7.6) | 0.2 | 1.5 | (0.4, 4.9) | 0.5 |

|

| ||||||

| Number of events | 45 | 26 | ||||

In youth with T2D, using univariate Cox proportional hazards models (Table 3B), MAP was positively associated with microvascular disease while BMI was negatively associated with microvascular disease. Macrovascular events were predicted by MAP (hazard ratio 1.46 [95% CI: 1.17–1.83], p=0.0009). Predictors of microvascular disease using the forward selection model included both MAP (hazard ratio 1.49 [95% CI: 1.23–1.79], p=<0.0001) and BMI (hazard ratio 0.72 [95% CI: 0.58–0.90], p=0.003).

4. Discussion

Prior to this study, the majority of data regarding early complications among the general diabetes population was restricted to early markers of disease including non-proliferative retinopathy, albuminuria, lipids, hypertension, and arterial stiffness.[4, 5, 22, 23] This study documents that although infrequent, severe vascular events (end-stage kidney disease (ESKD), blindness, MIs) take place in individuals less than 30 years of age and with duration of diabetes of only 10–15 years. Moreover, this analysis provides evidence that the higher rates of early disease markers in T2D versus T1D accurately convey an increased risk of advanced complications in all categories, by organ system and individual diagnosis (except for AKI).

4.1. Comparative Rates of Vascular Events in Other Cohorts of Youth-Onset T1D and T2D

Ophthalmic events were most common, with very high rates considering that most participants were in their early to mid-20’s. Reported rates of ophthalmic complications from other, smaller studies of youth-onset diabetes are variable, but generally lower than our findings.[24–26] In the UK, the rate of any site threatening diabetes-related eye disease in youth under the age of 18 has been reported at 1.21 per 10,000 person-years and the rate of sight-threating diabetic retinopathy is estimated to be 0.45 per 10,000 person-years.[24] An Australian study of youth-onset T1D and diabetes duration 8.0–9.4 years found PDR to be exceedingly rare, even in historic cases dating back to the 1990s, while diabetic macular edema was more common (0.5–1.4%).[25] The only other study identified which included both youth-onset T1D and T2D also found ophthalmic complications to be more common in T2D versus T1D, with PDR HR=1.9 (95% CI: 1.1–3.1).[26]

Notably, not only CKD, but also ESKD, emerged in the T2D stratum of our cohorts, whereas there were no cases in the T1D stratum. Given the small number of events in our study, further data are needed to determine the true difference in the epidemiology of diabetic kidney disease in youth onset T1D versus T2D. Previous studies reported a wide range of rates of ESKD in youth-onset T2D (from 4 to 250 cases per 10,000 person-years) with the highest rates in Australian Aboriginal and Pima Indian populations.[27] A recent study of ESKD in younger-onset T1D versus T2D (diagnosed 15–30 years) from a New Zealand registry found a 2-fold higher rate of ESKD in T2D versus T1D, after adjusting for sex, ethnicity and diabetes duration.[28] Unadjusted incidence rates of ESKD from the index time point (at mean diabetes duration 6.0 years), was 31 and 46 cases per 10,000 person-years; however, the follow up time extended to 25 years, possibly accounting for the higher rate than in the present study. In contrast, a study of Jewish Israeli young adults examined for military service included T1D (N=1,183) and T2D (N=196). After 30 years of follow-up there was a higher rate of ESKD in the T1D versus T2D strata (23.0 versus 13.2 per 10,000 person-years).[29] Mortality was higher in the T2D stratum, which may have partly accounted for the higher rate of ESKD in T1D, as noncompeting risk methods were employed which can inflate risk estimates.[30] However, the baseline exam occurred between 1967 and 1997, and the limited understanding of youth-onset T2D during that historic period have may also played a role.

The occurrence of major macrovascular complications in these young cohorts is perhaps even more concerning, especially in the T2D stratum, in whom rates were particularly high. A nationwide, register-based cohort study from the Swedish National Diabetes Register found cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in youth-onset T1D to be 5–10 fold higher than age and sex matched controls.[31] Overall CVD event rates among T1D diagnosed 10–20 years prior were higher than identified by the current study: MI: 4 per 10,000 person-years; stroke: 3–4 per 10,000 person-years; heart failure: 4 per 10,000 person-years.[31] A systematic review of youth-onset T2D found highly variable, yet exceedingly high rates of cardiovascular disease, ranging between 37 and 100 per 10,000 person-years.[27]

4.2. Associated Factors of Vascular Events

In youth-onset T1D, glycemic control was independently associated with microvascular complications, while in youth-onset T2D, blood pressure was the sole predictor for both micro- and macrovascular disease. These differences suggest distinct pathogenetic mechanisms of vascular complications in youth-onset T1D and T2D. Obesity, as it relates to cardiometabolic mediators, may be a major contributor to the differences in associated factors of vascular complications in youth-onset T1D and T2D. A longitudinal weight-glycemia cluster analysis in youth-onset T1D found that only those with hyperglycemia had an elevated risk of early markers of vascular complications, regardless of the presence of high BMI.[32] Moreover, metabolic consequences of obesity, namely, insulin resistance, play a major role in albuminuria in youth-onset T2D, but less so in youth-onset T1D.[33] A Chinese study of young-onset (<40yrs) T1D and T2D found the higher, unadjusted rates of major adverse cardiovascular events, peripheral vascular disease and ESKD in T2D versus T1D was no longer different, after adjusting for BMI, blood pressure and lipids.[34] Overall, data suggests that youth-onset T2D promotes vascular aging, and that higher blood pressure is an independent predictor of more rapid vascular changes.[35]

Interestingly, BMI was inversely associated with microvascular adverse events. While some studies have suggested that obesity is associated with diabetes complications,[36] others have reported what has been termed the obesity paradox with an inverse relationship between obesity and microvascular complications.[37] The inverse relationship with obesity and retinopathy was previously described in the TODAY cohort.[38] The pathophysiology explaining the relationship between an increase in fat mass and decrease in diabetes-related complications is not well understood, but one potential hypothesis is an increase in insulin-like growth factor in more obese individuals.[39]

This study has several strengths. The combination of the SEARCH and TODAY cohorts allowed for evaluation of the two largest collections of well phenotyped individuals with youth-onset T2D. Participants were followed longitudinally, and data is available over a minimum of 10 years. The study design of this ancillary study allowed for harmonized collection and adjudication of outcomes, increasing the validity and power of the study.

While TODAY was a clinical trial and SEARCH an observational cohort study, pooling of data was justified by several factors. The T2D participants in each study are quite similar, with overlapping rates of preclinical complications.[4, 5, 20, 40–42] The criteria for the diagnosis of T2D is very similar between the two studies such that all youth in TODAY would meet the inclusion criteria set forth for T2D in SEARCH. The collection of data was done prospectively within each cohort, and the methods of data collection were harmonized prior to the SEARCH data collection providing additional justification for the pooling of data from these two studies. Furthermore, the duration under randomization assignment of TODAY was limited to the first 5 years of the trail with the average duration of 3.86 years on the randomized protocol, and the impact of randomized assignment dissipated within the first 36 months after the trial ended.[43] The final phase of TODAY was an additional six years of purely observational follow-up with the participants receiving care in the community setting during the data collection for this manuscript,

Limitations of this study includes ascertainment of events relying on participant recall, potentially resulting in under-reporting of events. Adjudication was conducted via review of medical records. Some records were unavailable and others may have been missed, contributing to possible under-reporting. Some of the socioeconomic data was not available across the entire cohort limiting our ability to include these important factors in complication rates. Due to the low number of events, statistical power was limited and only variables of high clinical/scientific value were considered using forward selection, thus the factors we identified as associating with vascular events should be interpreted with caution.

In conclusion, major adverse events begin to emerge in youth-onset T1D and T2D within 10–15 years of diagnosis, impacting young adults in their twenties. Moreover, this study confirms that the greater prevalence of early markers of disease in youth-onset T2D versus youth-onset T1D, indeed forecasts a high rate of advanced complications, despite similar glycemia and duration of diabetes. These findings again underscore the aggressive nature of youth-onset T2D, and specifically the need for adequate blood pressure monitoring and treatment of hypertension to prevent vascular complications in T2D. Future work is needed to identify differences in the pathogenesis of advanced complications in youth-onset T1D versus T2D, to devise novel drug targets and treatment approaches to minimize the devastating effects of disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study and TODAY Study are indebted to the many youth and their families, and their health care providers, whose participation made this study possible.

The SEARCH authors wish to acknowledge the involvement of the Kaiser Permanente Southern California’s Marilyn Owsley Clinical Research Center (funded by Kaiser Foundation Health Plan and supported in part by the Southern California Permanente Medical Group); the South Carolina Clinical & Translational Research Institute, at the Medical University of South Carolina, NIH/National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) grant number UL1 TR000062, UL1 Tr001450; Seattle Children’s Hospital and the University of Washington, NIH/NCATS grant number UL1 TR00423; University of Colorado Pediatric Clinical and Translational Research Center, NIH/NCATS grant Number UL1 TR000154; the Barbara Davis Center at the University of Colorado at Denver (DERC NIH grant number P30 DK57516); the University of Cincinnati, NIH/NCATS grant number UL1 TR000077, UL1 TR001425; and the Children with Medical Handicaps program managed by the Ohio Department of Health. This study includes data provided by the Ohio Department of Health, which should not be considered an endorsement of this study or its conclusions.

The TODAY Study Group thanks the following companies for donations in support of the study’s efforts: Becton, Dickinson and Company; Bristol-Myers Squibb; Eli Lilly and Company; GlaxoSmithKline; LifeScan, Inc.; Pfizer; Sanofi Aventis. We also gratefully acknowledge the participation and guidance of the American Indian partners associated with the clinical center located at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, including members of the Absentee Shawnee Tribe, Cherokee Nation, Chickasaw Nation, Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, and Oklahoma City Area Indian Health Service; the opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the respective Tribes and the Indian Health Service.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The TODAY Study reports that The NIDDK project office was involved in all aspects of the study, including: design and conduct; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; review and approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Glossary of Terms:

- ACEI

Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitor

- AKI

Acute Kidney Injury

- ARB

Angiotensin Receptor Blocker

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- CKD

Chronic Kidney Disease

- DBP

Diastolic Blood Pressure

- ESKD

End Stage Kidney Disease

- HbA1c

Hemoglobin A1c

- LDL

Low Density Lipoprotein

- MAP

Mean Arterial Pressure

- MI

Myocardial Infarction

- NAFLD

NonAlcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

- NASH

NonAlcoholic Steatohepatitis

- PDR

Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy

- SBP

Systolic Blood Pressure

- T1D

Type 1 Diabetes

- T2D

Type 2 Diabetes

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

AKM reports consultancy agreements with Bayer, Chinook and ProKidney; research funding from Alexion, Bayer, Calliditas, Duke Clinical Research Institute, NIDDK, Pfizer, University of Pennsylvania, and honoraria from UpToDate; JBT and KLD report travel support from Harold Hamm Diabetes Center; SI reports funding from CDC, NCI, NIDDK and NIH; RGK reports funding support from NIDDK; LMD reports research funding from NIDDK; RD reports funding from NIDDK; NHW, KSH, LH, and NW have no COI to report.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lawrence JM, Divers J, Isom S, Saydah S, Imperatore G, Pihoker C, et al.Trends in Prevalence of Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes in Children and Adolescents in the US, 2001–2017. JAMA 2021; 326: pp717–727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wagenknecht LE, Lawrence JM, Isom S, Jensen ET, Dabelea D, Liese AD, et al.Trends in incidence of youth-onset type 1 and type 2 diabetes in the USA, 2002–18: results from the population-based SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth study. The lancet. Diabetes & endocrinology 2023; 11: pp242–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tönnies T, Brinks R, Isom S, Dabelea D, Divers J, Mayer-Davis EJ, et al.Projections of Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes Burden in the U.S. Population Aged <20 Years Through 2060: The SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study. Diabetes Care 2023; 46: pp313–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dabelea D, Stafford JM, Mayer-Davis EJ, D’Agostino R Jr., Dolan L, Imperatore G, et al.Association of Type 1 Diabetes vs Type 2 Diabetes Diagnosed During Childhood and Adolescence With Complications During Teenage Years and Young Adulthood. JAMA 2017; 317: pp825–835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bjornstad P, Drews KL, Caprio S, Gubitosi-Klug R, Nathan DM, Tesfaldet B, et al.Long-Term Complications in Youth-Onset Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med 2021; 385: pp416–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dart AB, Martens PJ, Rigatto C, Brownell MD, Dean HJ and Sellers EA Earlier onset of complications in youth with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2014; 37: pp436–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller RG, Orchard TJ and Costacou T 30-Year Cardiovascular Disease in Type 1 Diabetes: Risk and Risk Factors Differ by Long-term Patterns of Glycemic Control. Diabetes Care 2022; 45: pp142–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pavkov ME, Bennett PH, Knowler WC, Krakoff J, Sievers ML and Nelson RG Effect of youth-onset type 2 diabetes mellitus on incidence of end-stage renal disease and mortality in young and middle-aged Pima Indians. JAMA 2006; 296: pp421–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Costacou T and Orchard TJ Cumulative Kidney Complication Risk by 50 Years of Type 1 Diabetes: The Effects of Sex, Age, and Calendar Year at Onset. Diabetes Care 2018; 41: pp426–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller RG, Costacou T and Orchard TJ Risk Factor Modeling for Cardiovascular Disease in Type 1 Diabetes in the Pittsburgh Epidemiology of Diabetes Complications (EDC) Study: A Comparison With the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications Study (DCCT/EDIC). Diabetes 2019; 68: pp409–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hainsworth DP, Bebu I, Aiello LP, Sivitz W, Gubitosi-Klug R, Malone J, et al.Risk Factors for Retinopathy in Type 1 Diabetes: The DCCT/EDIC Study. Diabetes Care 2019; 42: pp875–882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Looker HC, Pyle L, Vigers T, Severn C, Saulnier PJ, Najafian B, et al.Structural Lesions on Kidney Biopsy in Youth-Onset and Adult-Onset Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2022; 45: pp436–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim NH, Pavkov ME, Knowler WC, Hanson RL, Weil EJ, Curtis JM, et al.Predictive value of albuminuria in American Indian youth with or without type 2 diabetes. Pediatrics 2010; 125: ppe844–851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krakoff J, Lindsay RS, Looker HC, Nelson RG, Hanson RL and Knowler WC Incidence of retinopathy and nephropathy in youth-onset compared with adult-onset type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2003; 26: pp76–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perkins BA, Bebu I, de Boer IH, Molitch M, Tamborlane W, Lorenzi G, et al.Risk Factors for Kidney Disease in Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2019; 42: pp883–890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stratton IM, Adler AI, Neil HA, Matthews DR, Manley SE, Cull CA, et al.Association of glycaemia with macrovascular and microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 35): prospective observational study. Bmj 2000; 321: pp405–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tight blood pressure control and risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 38. UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Bmj 1998; 317: pp703–713. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fritz J, Brozek W, Concin H, Nagel G, Kerschbaum J, Lhotta K, et al.The Association of Excess Body Weight with Risk of ESKD Is Mediated Through Insulin Resistance, Hypertension, and Hyperuricemia. J Am Soc Nephrol 2022; 33: pp1377–1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Group TS, Bjornstad P, Drews KL, Caprio S, Gubitosi-Klug R, Nathan DM, et al.Long-Term Complications in Youth-Onset Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med 2021; 385: pp416–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shah AS, Isom S, D’Agostino R, Dolan LM, Dabelea D, Imperatore G, et al.Longitudinal Changes in Arterial Stiffness and Heart Rate Variability in Youth-Onset Type 1 Versus Type 2 Diabetes: The SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study. Diabetes Care 2022; 45: pp1647–1656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Longitudinal Changes in Cardiac Structure and Function From Adolescence to Young Adulthood in Participants With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: The TODAY Follow-Up Study. Circ Heart Fail 2020; 13: ppe006685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Madsen NL, Haley JE, Moore RA, Khoury PR and Urbina EM Increased Arterial Stiffness Is Associated With Reduced Diastolic Function in Youth With Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes. Front Pediatr 2021; 9: pp781496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li X, Deng YP, Yang M, Wu YW, Sun SX and Sun JZ Low-Grade Inflammation and Increased Arterial Stiffness in Chinese Youth and Adolescents with Newly-Diagnosed Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol 2015; 7: pp268–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ibanez-Bruron MC, Solebo AL, Cumberland P and Rahi JS Epidemiology of visual impairment, sight-threatening or treatment-requiring diabetic eye disease in children and young people in the UK: findings from DECS. The British journal of ophthalmology 2021; 105: pp729–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allen DW, Liew G, Cho YH, Pryke A, Cusumano J, Hing S, et al.Thirty-Year Time Trends in Diabetic Retinopathy and Macular Edema in Youth With Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2022; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bai P, Barkmeier AJ, Hodge DO and Mohney BG Ocular Sequelae in a Population-Based Cohort of Youth Diagnosed With Diabetes During a 50-Year Period. JAMA Ophthalmol 2022; 140: pp51–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fan Y, E SHL., Wu H., Yang A., Chow E., So WY., et al.Incidence of long-term diabetes complications and mortality in youth-onset type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2022; pp110030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Middleton TL, Chadban S, Molyneaux L, D’Souza M, Constantino MI, Yue DK, et al.Young adult onset type 2 diabetes versus type 1 diabetes: Progression to and survival on renal replacement therapy. J Diabetes Complications 2021; 35: pp108023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pleniceanu O, Twig G, Tzur D, Gruber N, Stern-Zimmer M, Afek A, et al.Kidney failure risk in type 1 vs. type 2 childhood-onset diabetes mellitus. Pediatr Nephrol 2021; 36: pp333–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jiang Y, Fine JP and Mottl AK Competing Risk of Death With End-Stage Renal Disease in Diabetic Kidney Disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2018; 25: pp133–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rawshani A, Sattar N, Franzén S, Rawshani A, Hattersley AT, Svensson AM, et al.Excess mortality and cardiovascular disease in young adults with type 1 diabetes in relation to age at onset: a nationwide, register-based cohort study. Lancet 2018; 392: pp477–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kahkoska AR, Nguyen CT, Adair LA, Aiello AE, Burger KS, Buse JB, et al.Longitudinal Phenotypes of Type 1 Diabetes in Youth Based on Weight and Glycemia and Their Association With Complications. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2019; 104: pp6003–6016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mottl AK, Divers J, Dabelea D, Maahs DM, Dolan L, Pettitt D, et al.The dose-response effect of insulin sensitivity on albuminuria in children according to diabetes type. Pediatr Nephrol 2016; 31: pp933–940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luk AO, Lau ES, So WY, Ma RC, Kong AP, Ozaki R, et al.Prospective study on the incidences of cardiovascular-renal complications in Chinese patients with young-onset type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2014; 37: pp149–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ryder JR, Northrop E, Rudser KD, Kelly AS, Gao Z, Khoury PR, et al.Accelerated Early Vascular Aging Among Adolescents With Obesity and/or Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Journal of the American Heart Association 2020; 9: ppe014891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gao S, Zhang H, Long C and Xing Z Association Between Obesity and Microvascular Diseases in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2021; 12: pp719515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rooney D, Lye WK, Tan G, Lamoureux EL, Ikram MK, Cheng CY, et al.Body mass index and retinopathy in Asian populations with diabetes mellitus. Acta Diabetol. 2015; 52: pp73–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Levitsky LL, Drews KL, Haymond M, Gubitosi-Klug RA, Levitt-Katz LE, Mititelu M, Tamborlane W, Tryggestad JB, Weinstock RS The obesity paradox: Retinopathy, obesity, and circulating risk markers in youth with type 2 diabetes in the TODAY Study. J. Diabetes Complications 2022; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Biadgo B, Tamir W and Ambachew S Insulin-like Growth Factor and its Therapeutic Potential for Diabetes Complications - Mechanisms and Metabolic Links: A Review. The review of diabetic studies : RDS 2020; 16: pp24–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Development and Progression of Diabetic Retinopathy in Adolescents and Young Adults With Type 2 Diabetes: Results From the TODAY Study. Diabetes Care 2021; 45: pp1049–1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jensen ET, Rigdon J, Rezaei KA, Saaddine J, Lundeen EA, Dabelea D, et al.Prevalence, Progression, and Modifiable Risk Factors for Diabetic Retinopathy in Youth and Young Adults With Youth-Onset Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes: The SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study. Diabetes Care 2023; 46: pp1252–1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shah AS, El Ghormli L, Gidding SS, Hughan KS, Levitt Katz LE, Koren D, et al.Longitudinal changes in vascular stiffness and heart rate variability among young adults with youth-onset type 2 diabetes: results from the follow-up observational treatment options for type 2 diabetes in adolescents and youth (TODAY) study. Acta diabetologica 2022; 59: pp197–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Postintervention Effects of Varying Treatment Arms on Glycemic Failure and β-Cell Function in the TODAY Trial. Diabetes Care 2021; 44: pp75–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.