Abstract

Adipose tissue was once known as a reservoir for energy storage but is now considered a crucial organ for hormone and energy flux with important effects on health and disease. Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) is an incretin hormone secreted from the small intestinal K cells, responsible for augmenting insulin release, and has gained attention for its independent and amicable effects with glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1), another incretin hormone secreted from the small intestinal L cells. The GIP receptor (GIPR) is found in whole adipose tissue, whereas the GLP-1 receptor (GLP-1R) is not, and some studies suggest that GIPR action lowers body weight and plays a role in lipolysis, glucose/lipid uptake/disposal, adipose tissue blood flow, lipid oxidation, and free-fatty acid (FFA) re-esterification, which may or may not be influenced by other hormones such as insulin. This review summarizes the research on the effects of GIP in adipose tissue (distinct depots of white and brown) using cellular, rodent, and human models. In doing so, we explore the mechanisms of GIPR-based medications for treating metabolic disorders, such as type 2 diabetes and obesity, and how GIPR agonism and antagonism contribute to improvements in metabolic health outcomes, potentially through actions in adipose tissues.

Keywords: brown adipose tissue, energy expenditure, energy metabolism, glucagon-like peptide 1, glucose control, glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide, insulin sensitivity, lipid metabolism obesity, resting energy expenditure, type 2 diabetes mellitus, white adipose tissue

Introduction

Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) is secreted as a 42-amino acid peptide from the K cells of the upper small intestine in response to meal ingestion (Ugleholdt et al. 2006). Initially identified as gastric inhibitory polypeptide because high dose administration reduced gastric motility (Brown & Pederson 1970), GIP was renamed because its leading mode of action after a glucose bolus is to potentiate pancreatic β-cell insulin secretion through downstream signaling of the GIP receptor (GIPR) (Dupre et al. 1973) (reviewed in Finan et al. (2016)). Transcripts and translated proteins of GIP have also been detected in the brain and pancreatic α cells in mouse and human islets. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) degrades GIP in rodents (Kieffer et al. 1995) and humans (Mentlein et al. 1993), yielding a truncated and inactive version of the peptide.

The function of GIP is now known to extend beyond its role in the pancreas. The GIPR is found in the pancreas, bone, cardiomyocytes, brain, gastrointestinal (GI) tract, endothelial and neuronal cells, and adipose tissue (AT) (Seino et al. 2010) but not in the whole skeletal muscle or liver (Beaudry et al. 2019) (reviewed in Hammoud & Drucker (2022)). Recently, techniques using in situ hybridization detect mRNA transcripts in isolated fibro-adipogenic progenitors in mouse tibialis anterior muscle (Takahashi et al. 2023), but the GIPR protein remains to be confirmed in this tissue with the lack of a validated antibody. GIP increases whole-body lipid oxidation, increases AT blood flow and lipid uptake, reduces food consumption via signaling actions in the brain, and reduces body weight. Altogether, GIPR agonists have become an attractive pharmacotherapy agent for treating type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and potentially inducing weight loss in obese patients, like glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor (GLP-1R) agonists (Finan et al. 2016, Samms et al. 2020). In addition, GIPR agonists may reduce gastrointestinal issues often observed with the intake of medicines containing GLP-1R (Borner et al. 2021). As GLP-1R is expressed in the same tissues listed for GIPR, except for bone and AT (McLean et al. 2021), the link between improvements in metabolic outcomes and GIP may be driven through AT.

Humans have different types of AT responsible for regulating whole-body glucose and fatty acid (FA) metabolism, including white adipose tissues and brown adipose tissues (WAT and BAT, respectively) (Choe et al. 2016). WAT is responsible for storing energy in the form of intracellular triglycerides (TGs) and releasing energy in the form of FAs to other tissues in the body, while BAT is responsible for oxidizing metabolic substrates to generate heat (Cannon & Nedergaard 2004). Increased BAT recruitment and activity protect rodents from body weight gain, and when BAT is present in adult humans, it has been linked with a lower risk of visceral WAT accumulation, T2DM, cardiovascular disease, and dyslipidemia (Becher et al. 2021, Wibmer et al. 2021). However, we still do not know whether BAT is a protective organ in humans against chronic metabolic disease. Dysfunctional AT may cause metabolic health impairments and lipid spillover in the body, which may lead to lipid accumulation in non-AT, leading to obesity-related insulin resistance (Goossens & Blaak 2015) and low-grade chronic inflammation (Hu et al. 2018). The role of AT in regulating whole-body energy homeostasis makes understanding how therapeutic treatments impact AT function imperative for drug design.

Revisiting the physiological role of GIP in energy metabolism exposes unresolved questions regarding GIP and its self-governing physiological function apart from GLP-1. There are now several studies investigating the independent effects of GIP on obesity models in rodents and humans and how it appears to modulate glucose and lipid metabolism, as well as insulin signaling at the level of the AT. Future research may also allow the possibility of determining any sex-specific differences. This review presents current knowledge on the actions of GIP in both WAT and BAT, in cellular, rodent, and human studies. As it remains unclear whether GIPR agonism or antagonism promotes healthy AT function, this review also discusses what is known about activation and inhibition of GIPR at the AT level and its potential benefits for whole-body energy metabolism, affecting both health and disease.

White adipose tissue

In vitro effect of GIP

Previous studies have demonstrated that GIP administration contributes to changes in WAT lipid metabolism (Fig. 1), although more information is needed on GIPR expression in non-adipocyte fractions of WAT (Campbell et al. 2022). Previous work highlights GIP’s role in lipid uptake and storage in differentiated white adipocytes. For example, GIP treatment (100 nM) in the presence of insulin (1 nM) increases lipoprotein lipase (LPL) activity in both differentiated murine-derived WAT (3T3-L1) cells and subcutaneous human adipocytes (Kim et al. 2007), leading to increases in TG stores. The increase in LPL-mediated TG uptake was attributed to the upregulation of the protein kinase B activity, which mediates downstream proteins such as liver kinase B1 and AMP-activated protein kinase. These findings indicate that, in the presence of insulin, GIP increases LPL activity, likely aiding with exogenous TG uptake and storage in WAT. However, it has also been shown that GIP dose dependently increases LPL activity in differentiated 3T3-L1 adipocytes in the absence of insulin (Miyawaki et al. 2002). Therefore, there are opposing findings on whether GIP, in the presence or absence of insulin, improves LPL activity.

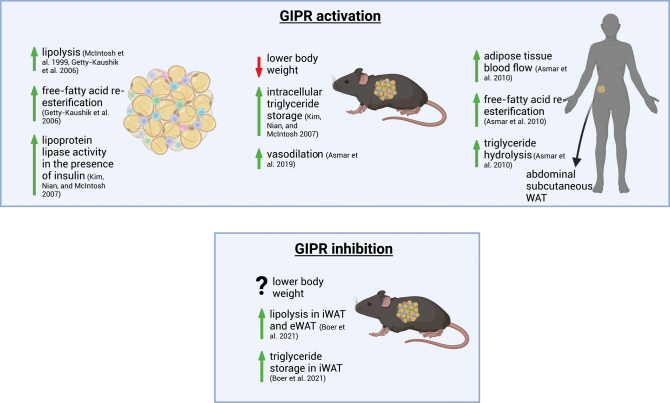

Figure 1.

Effects of GIPR activation and inhibition in cells, and WAT from rodents and humans. GIP receptor (GIPR) is expressed in pericytes, endothelial cells, macrophages, and mesothelial cells in white adipose tissue (WAT) (Hammoud & Drucker 2022). GIPR agonism has shown an increase in lipolysis, free-fatty acid re-esterification, and lipoprotein activity in vitro (Kim et al. 2007, McIntosh et al. 1999, Getty-Kaushik et al. 2006). Adipose tissue blood flow, triglyceride lipolysis, and free-fatty acid re-esterification have increased in humans with GIP treatment (Asmar et al. 2010). Both GIPR activation and inhibition show a reduction in body weight in vivo, but reducing GIPR signaling in the whole animal increases lipolysis in iWAT and eWAT and TG storage in iWAT (Boer et al. 2021). Created in BioRender.

GIP also plays a role in lipid breakdown in WAT. Exposure to GIP concentrations over the range of 0.1 and 1000 nM, for 4 h in 3T3-L1 adipocytes (McIntosh et al. 1999), and 1, 10, and 100 nM of GIP for 1 h in isolated primary rat adipocytes (Getty-Kaushik et al. 2006), produced higher lipolytic rates compared to basal levels, leading to increased free-fatty acid (FFA) re-esterification (Getty-Kaushik et al. 2006). In addition, 3T3-L1 cells treated with GIP concentrations of 1, 10, and 100 nM increased cyclic AMP (cAMP) levels, indicating that GIP-stimulated lipolysis is due to changes in cAMP activity (McIntosh et al. 1999), which may be contributing to the stimulation of lipolysis. The cAMP pathway plays a crucial role in GIP-induced lipolysis, as demonstrated by the use of an adenylyl cyclase inhibitor MDL 12330A (10−4 M), which reduced cAMP and glycerol levels in the presence of GIP (0−100 nM) (McIntosh et al. 1999). When 3T3-L1 cells are pre-incubated with insulin, followed by GIP exposure, the lipolytic effect of GIP is completely inhibited. The pre-incubation addition of wortmannin (a potent inhibitor of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, PI3K, 10−7 M) to insulin restores GIP’s lipolytic effects. These findings suggest that insulin is dependent on the PI3K mechanism to inhibit GIP-induced lipolysis (Fig. 2). On the contrary, while GIP (10 nM) or insulin alone (10 µU/mL) increased lipolysis and FFA re-esterification compared to basal levels (Getty-Kaushik et al. 2006), concurrent administration of GIP (10 nM) and insulin (10 µU/mL) to 3T3-L1 cells (i.e. no pre-incubation) did not change rates of glycerol and FFA release. The regulatory role of GIP for white adipocyte lipolysis and FFA re-esterification appears to be dictated by the presence of insulin, requiring further investigation into how GIP and insulin impact signaling mechanisms in WAT.

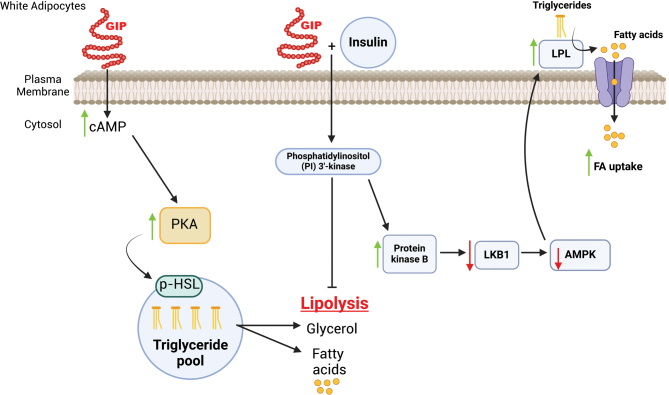

Figure 2.

GIP-induced lipolysis and insulin signaling in white adipocytes. Exogenous administration of GIP to 3T3-L1 cells increases lipolysis through the cAMP pathway (Getty-Kaushik et al. 2006, McIntosh et al. 1999). Pre-incubation with insulin in differentiated 3T3-L1 cells followed by GIP exposure inhibits the lipolytic effect of GIP. Evidence suggests that GIP treatment in the presence of insulin increases the phosphorylation of protein kinase B (PKB) and decreases the phosphorylation of LKB1 and AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), causing LPL activation and TG accumulation in differentiated 3T3-L1 cells (Kim et al. 2007). The primary role of AMPK is to stimulate the pathway which increases lipid oxidation and suppresses lipogenesis and lipolysis, while LKB1 is responsible for phosphorylating AMPK (Daval et al. 2006). Created in BioRender.

Research also shows that GIP has anti-lipolytic actions in adipocytes. Isoproterenol (β1,2-adrenergic receptor agonist; 1 μM) increased lipolysis in isolated rat adipocytes (Getty-Kaushik et al. 2006), but the addition of GIP to isoproterenol significantly decreased lipolysis. Moreover, the addition of a GIPR antagonist (ANTGIP) to GIP and isoproterenol resulted in a restoration of the lipolytic response, suggesting that GIPR agonism may play an inhibitory role in stimulated lipolysis in white adipocytes.

Dose and media conditions play important roles in understanding the effects of GIP on lipid metabolism in AT, where GIP at concentrations of 1–10 nM has a strong lipolytic effect on adipocytes under low insulin conditions in the context of in vitro murine-derived cell culture models. Moreover, dosing typically conducted in cell culture models that report changes in lipid flux within the adipocytes would be defined in the pharmacological range, as post prandial GIP levels are found to be ~400–600 pg/mL in rodents (Campbell et al. 2016) and ~1000–1500 pg/mL in humans (Nauck et al. 1986).

In addition to its impact on WAT and lipid uptake, GIP has also been shown to promote an increase in the translation of glucose transporter type 4 (GLUT4: a protein that aids in glucose uptake in AT in response to insulin) in 3T3-L1 adipocytes wild-type (WT) GIPR, or expressing E354Q GIPR, a mutation in the GIPR gene, a variant associated with insulin resistance, T2DM, and cardiovascular risk in humans. This effect suggests that the downstream signaling pathways activated by GIP are not altered in the presence of the E354Q variant (Mohammad et al. 2014), although the variant has been shown to result in the downregulation of GIPR from the plasma membrane after GIP stimulation.

In vivo effect of GIP in rodents

Although the presence of the GIPR within the whole AT implies that GIP may be exerting specific effects on WAT function, the exact mechanisms remain unknown. Gain-of-function studies with GIP treatment demonstrate increased WAT vasodilation and lipid clearance (Asmar et al. 2019), while reducing body weight, food intake, and fat mass, but not lean mass (Zhang et al. 2021, Liskiewicz et al. 2023). Furthermore, elevated LPL activity and intracellular TG storage in epididymal WAT (eWAT) were observed in obese Vancouver diabetic fatty (VDF) rats compared to controls after 2 weeks of treatment with GIP (10 pmol/kg/min) (Kim et al. 2007). These findings suggest that fat storage in rodents is affected by LPL activity, but it is unclear if insulin or other hormones are necessary facilitators.

Whole-body overexpression of GIP levels (using GIP-transgenic, heterozygous mice) has been used to evaluate fat development (Kim et al. 2012). GIP-transgenic mice gained less body weight than WT littermate control mice fed a high-fat diet (HFD) and were more insulin-sensitive compared to WT littermates, independent of adipocyte epididymal size. GIP-transgenic mice also exhibited a lower overall fat percentage and adiposity index compared to WT mice. The reduced adiposity observed in GIP-transgenic mice was associated with decreased food intake independent of lower energy expenditure. However, these mice did exhibit reduced physical activity, possibly related to the overexpression of hypothalamic GIP levels. On the contrary, GIPR-deficient mice have shown increased energy expenditure associated with increases in locomotor activity (Hansotia et al. 2007), trends to exhibit lower anxiety-like behavior, improved exploration, spatial learning, and memory ability (Takahashi et al. 2023). These findings suggest a complex interplay between GIP signaling and behavioral and cognitive functions and their effects on whole-body metabolism. GIP-transgenic mouse eWAT also exhibited reduced mRNA levels of genes related to FA synthesis, mitochondrial biogenesis and function, and gene expression levels relating to inflammation and insulin responses. Protein expression for insulin receptor 1 decreased, while that for insulin receptor 2 increased in the eWAT of GIP-transgenic mice, maintaining insulin sensitivity. Recent studies show that long-acting GIPR (LA-GIPR) agonism signaling pathways in the central nervous system regulate food intake, body weight, fat mass, and glucose homeostasis (Zhang et al. 2021). These results appear to be regulated by the hypothalamic expression of GIPR, which has recently been reported to be a contribution of the inhibitory GABAergic neuronal population (Liskiewicz et al. 2023). GIPR has also been found to be expressed in brain regions such as the olfactory bulb, cerebral cortex, and hippocampus, and is responsible for regulating appetite and satiety (Usdin et al. 1993). GLP-1R is co-expressed in some neuronal areas with GIPR such as the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus, nucleus tractus solitarius, and area postrema of the dorsal vagal complex (reviewed in Hammoud & Drucker (2022)). Therefore, the overexpression of GIP may be driven by the central effects on WAT and is less likely because of WAT’s regulation of GIP in the brain. However, it is important to consider that since WAT Gipr mRNA expression levels are relatively higher than those detected in the hypothalamic regions of the brain (Zhang et al. 2021), there may be potential cross talk between the central nervous system and WAT.

Moreover, advancements in the development of GIP agonists have enhanced our understanding of GIP’s effect on body weight and appetite regulation. GIPFA-085, GIP-D-Ala2, and LA-GIPR agonists have a modified amino acid sequence or N-terminus compared to the native GIP, which protects against DPP-4 cleavage (Irwin & Flatt 2009), extending the circulating half-life of GIP from 4 to 7 min (Vilsboll et al. 2006) to several hours in mice (i.e. 06:29 h (Samms et al. 2021)). The increased half-life allows more time for administered GIP to interact and exert its influence on peripheral tissues. One study demonstrated that GIPFA-085 (300 nmol/kg; half-life 6.55 h) administered to diet-induced obese (DIO) mice, decreased daily food intake on days 1–3 and significantly reduced body weight gain on days 3–12 (Han et al. 2023). Another study found that LA-GIPR treatment showed increased insulin sensitivity in the AT, and increased glucose uptake into WAT, but no changes in gene expression regulatory pathways were observed (Samms et al. 2021). On the contrary, HFD-fed mice given daily intraperitoneal injections of GIP-D-Ala2 (0.12 µg/g) in the last 8 weeks of a 14-week HFD showed no differences in body weight, food intake, or visceral fat weight compared to vehicle controls (Varol et al. 2014). However, GIP-D-Ala2-treated DIO mice more than doubled epididymal adipocyte size (Varol et al. 2014), indicating greater lipid storage capacity. Increased gene expression in plin1, cidea, cidec, and pparγ in lipid droplets in male mice epididymal fat was also observed, allowing for greater lipid deposition in AT (Varol et al. 2014). Overall, these findings suggest that exogenous GIP administration improves whole-body substrate deposition in WAT; however, differences in agonist structure, dose, timing of administration, and agonist half-life may all impact food intake and body weight loss. Future work should carefully consider dosage conditions when assessing the effects of GIP on AT tissue function in vivo.

In vivo effect of GIP in humans

Studies have investigated the effects of GIP on WAT lipid metabolism in rodents but have not revealed the role of GIP action on human WAT. Researchers employing intravenous clamps to control circulating glucose and insulin levels in human subjects (Asmar et al. 2010, Asmar et al. 2014, Asmar et al. 2016b) have found that, in lean, healthy human subjects under hyperinsulinemic–hyperglycemic conditions, GIP infusion increased abdominal subcutaneous white adipose tissue blood flow (ATBF), FFA re-esterification, glucose uptake, LPL activity, and TG hydrolysis, leading to increased TG storage in the anterior, abdominal subcutaneous WAT compared to vehicle controls (Asmar et al. 2010). Another study found that in lean humans under hyperinsulinemic–euglycemic conditions, lipid uptake increased, and lipid breakdown decreased in the presence of GIP (Asmar et al. 2016b). These findings demonstrate that insulin facilitates GIP-mediated TG uptake into WAT and inhibits lipid breakdown through decreases in WAT lipolysis (Asmar et al. 2016b).

In contrast, under high glucose and insulin conditions, there were no differences in subcutaneous AT lipid storage among obese individuals with higher glucose excursions compared to subjects who were classified as responsive to a glucose bolus (Asmar et al. 2014). Additionally, FFA/glycerol ratios were higher in the impaired versus normal glucose-tolerant obese group (Asmar et al. 2014), indicating reduced FFA re-esterification. This likely resulted from impaired glucose uptake and inhibition of lipolysis mechanisms directly at the level of the WAT. Therefore, it may be that in the presence of insulin, GIP promotes the storage of FFAs in subcutaneous WAT instead of remaining in the circulation of healthy individuals.

Many studies suggest that GIP’s effects in vivo on AT glucose uptake, TG hydrolysis, and FFA re-esterification may result from GIP stimulation and elevation of circulating insulin levels (Asmar et al. 2017). Insulin drives nutrient storage into organs such as AT; however, GIP’s effect on energy metabolism and homeostasis is complicated and may act independently of insulin. For example, studies in healthy lean human subjects have shown a decrease in non-esterified fatty acids (NEFA) after exogenous GIP administration, with hyperinsulinemia and slight hyperglycemia (Asmar et al. 2017). However, when type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) patients (with low insulin production) were provided a subcutaneous GIP infusion, they showed an increase in NEFA levels during the first 3 h, without changes in fasting plasma levels of C-peptide or insulin (Heimburger et al. 2022). GIP infusions initially lowered the respiratory exchange ratio (RER) in T1DM subjects within the first 150 min, possibly indicating changes in fuel selection, favoring lipids versus glucose (Heimburger et al. 2022). However, liver fat accumulation increased in GIP-treated T1DM individuals following 6 days of GIP administration. More work is needed to assess the interplay between insulin and GIP on lipid deposition. In the absence of insulin, exogenous GIP may increase circulating NEFAs (indicative of higher rates of lipolysis), but the presence of insulin with exogenous GIP promotes healthy lipid deposition into AT. Clinical trials are currently exploring LA-GIPR agonists (Muller et al. 2022) to determine their effects on body weight loss, T2DM, and energy metabolism, and whether GIP actions are dependent or independent of insulin levels and/or insulin sensitivity.

In the fasted state, GIP treatment plays no role in WAT lipid metabolism (Asmar et al. 2010), suggesting that glucose or insulin levels may be required for GIP to regulate lipid metabolism in humans. These impairments in GIP-induced WAT metabolism are more revealing in obese subjects who have reduced insulin sensitivity and reduced capacities to convert glucose into glycerol (Asmar et al. 2016a). Individuals who lose weight and reinstate insulin sensitivity may also improve GIP signaling at the level of the subcutaneous AT (Asmar et al. 2016a). However, it is unclear whether there are differences between subcutaneous and visceral AT and GIP sensitivity. These conclusions are confirmed where GIP infusions alone increased TG uptake and decreased FFA output and FFA/glycerol ratios compared to the effects of GIPR antagonist (GIP (3–30)NH2), which decreased TG uptake and increased white ATBF in lean subjects (Asmar et al. 2017). These findings indicate that GIP can contribute to lower circulating lipid levels by increasing TG offloading and reducing lipolysis in healthy human WAT. Adipogenic effects of GIP have also been assessed in T2DM obese individuals under fasting conditions, where plasma NEFA concentrations decreased with GIP infusion while increasing subcutaneous AT TGs (Thondam et al. 2017). This effect was linked to insulin sensitivity of the individual. GIP-induced TG uptake into AT may be dependent on the level of AT insulin resistance, which can enhance obesity and T2DM conditions.

Whether GIP sensitivity changes in WAT under hyperglycemic conditions, similar to pancreatic beta cells (Vilsboll et al. 2002), remains an area of investigation. However, it is important to note that disruption in GIP signaling observed in individuals with T2DM is linked with increasing measurements of body mass index (reviewed in Finan et al. (2016)). Thus, GIP sensitivity in WAT may diminish under conditions of insulin resistance or hyperglycemia, leading to impaired fat metabolism. However, the exact mechanisms underlying this phenomenon are not clearly understood.

Besides GIP’s effects on glucose and lipid metabolism, GIP may provide additional benefits to WAT function via ATBF. GIP administration to lean, healthy humans during hyperinsulinemia causes a four-fold increase in blood flow and TG clearance in subcutaneous abdominal AT when compared to saline controls (Asmar et al. 2019). This suggests that GIP may enhance capillary recruitment in WAT, increasing blood flow and substrate transport into WAT (Tobin et al. 2010). Increased ATBF may result in increased interactions between circulating lipoproteins and AT LPL (Asmar et al. 2019), which likely promotes TG hydrolysis and TG uptake in AT. ATBF increased three-fold after 30 min during GIP infusion when subjects were exposed to hyperinsulinemic–euglycemic conditions (Asmar et al. 2016b). However, under fasted conditions, GIP has no effect on ATBF in subcutaneous abdominal WAT (Asmar et al. 2010), further suggesting the importance of the presence of insulin for increasing ATBF. Overall, these studies have helped gain a better understanding of the direct effects of GIP on AT in humans.

In addition to the effects of GIP on ATBF, GIP exerts several other effects on vascular functions, including antiatherogenic actions that help prevent the formation of plaques in the arteries and nitric oxide production (reviewed in Heimburger et al. (2020)), which regulates blood flow and vascular tone (Chen et al. 2008). GIP suppresses the inflammatory responses to monocytes, macrophages, and adipocytes; however, these effects have mainly been demonstrated in rodent models (Varol et al. 2014). There are multifaceted effects of GIP on ATBF and vascular function; however, further investigation on rodents with obesity and T2DM will help understand whether the effects of GIP are consistent across different pathological conditions.

GIPR-based therapies and their effects on WAT

Gut-hormone therapies have become prevalent in the treatment of obesity and T2DM (Tschop et al. 2023). GLP-1R agonists induce satiety (Naslund et al. 1999), but they also can cause nausea and vomiting (Bettge et al. 2017) that appear to escalate with higher dose concentrations or during medication titrations (Aroda & Ratner 2011). Co-agonists combine GLP-1R agonists to lower food intake and increase satiety, and GIPR agonists to reduce incidences of adverse gastrointestinal effects, improve insulin sensitivity, and increase energy metabolism in AT.

Histological analysis of eWAT in DIO mice chronically treated with a GIPR–GLP-1R agonist showed reduced adipocyte size when compared to the use of liraglutide (GLP-1R agonist) and vehicle control (Finan et al. 2013). In addition, treatment with the GIPR–GLP-1R co-agonist reduced overall fat mass and body weight in a dose-dependent manner (3–30 nmol/kg) in DIO mice compared to treatment with exendin-4 (GLP-1R agonist, dosed at 10 nmol/kg and 30 nmol/kg). Adding a polyethylene glycol tail to enhance bioavailability and half-life (PEGylated GIPR–GLP-1R co-agonist) of GIPR/GLP-1R dual agonism lowered body weight by 26.9%, whereas the acylated co-agonist lowered it by 31.4%, and liraglutide by 15.6%, with all three agonists similarly lowering food intake and improving dyslipidemia and hyperglycemia (Finan et al. 2013). Both the PEGylated co-agonist and acylated co-agonist similarly decreased plasma leptin and TG levels compared to liraglutide and vehicle control-treated DIO mice, but this is likely driven by greater body weight loss with treatments (Finan et al. 2013). Liraglutide treatment increased plasma FFA levels, whereas the GIPR–GLP-1R co-agonist did not affect circulating free lipid levels. Therefore, including GIPR agonists in medications may counteract the effects of a GLP-1R-induced rise in FFA levels, but these mechanisms of action are unclear as GLP-1R is not expressed in AT. Overall, the effectiveness of GLP-1R agonists may be higher in the presence of GIPR agonists (Samms et al. 2020), with GIPR–GLP-1R co-agonists inducing much greater reductions in fat mass and weight loss than GLP-1R agonists alone (Frías et al. 2021). It is likely that combining these two peptides allows each to provide direct signaling in the respective tissue that expresses their receptor. Given the dramatic effects these peptide therapies have on reductions in body weight and fat mass, more work assessing specific actions on AT function and whole-body energy metabolism independent of lower body weight will help guide the dramatic effects of peptide therapies on reductions in body weight loss and fat mass.

Work has demonstrated that 14 days of treatment with a GIPR–GLP-1R-co-agonist (tirzepatide, 10 nmol/kg) lowered FFA, TG levels, and hepatic lipid content in obese insulin-resistant (IR) mice compared to those treated with vehicle control (Samms et al. 2021). Tirzepatide improved insulin-stimulated glucose disposal in several tissues, including soleus skeletal muscle, eWAT, and iWAT, more than in pair-fed mice, indicating weight-independent improvements in whole-body insulin sensitivity in obese IR mice. In addition, WT and obese IR whole-body Glp-1r−/− mice given vehicle or tirzepatide for 14 days were found to have no effect on insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in subcutaneous WAT but did show an enhancement in overall glucose infusion rates and glucose uptake in eWAT. These results indicate that tirzepatide may induce an effect of glucose uptake in WAT mediated through the GIPR. Samms et al. (2021) also showed that a LA-GIPR agonist (300 nmol/kg; half-life 06:29 h) administered daily for 14 days increased glucose uptake and insulin sensitivity in visceral and subcutaneous WAT in HFD-fed obese IR mice. However, these changes were insufficient to change gene expression related to glucose FA metabolism in WAT. We can conclude that GIPR agonism may enhance insulin sensitivity and act within the AT, independent of the actions of GLP-1R agonism.

Combining GIPR–GLP-1R agonists results in weight loss and lower glycemic levels in rodents and obese humans with T2DM. The use of tri-agonists, which include GIPR–GLP-1R and glucagon receptor (Gcgr) agonists, shows additional substantial effects, including the prevention of body weight gain, decreased food intake, and improvements in glucose and lipid profiles that exceed those of dual or mono-agonists (Finan & Douros 2022, Bailey et al. 2023) in both rodents and humans (Knerr et al. 2022, Jastreboff et al. 2023, Rosenstock et al. 2023). Teasing apart GIP’s independent effects in experiments using tri-agonist therapy has been challenging, but it has been found that GIPR agonism alone reduced body fat by 6.4% and reduced cumulative food intake in DIO mice compared to vehicle control (Finan et al. 2015). After 20 days in male DIO mice, the tri-agonist (3 nmol/kg) showed itself to be more potent in decreasing body weight by 26.6%, as opposed to the GIPR–GLP-1R co-agonist (3 nmol/kg) at 15.7%. Both WT and Gipr−/− HFD-fed mice treated with the tri-agonist showed similar reductions in fat mass, food intake, and body weight (Finan et al. 2015). However, the exact role of GIPR agonism separated from the actions of GLP-1R and Gcgr is still uncertain. Central actions of GIP may be responsible for the reduced body weight in DIO mice treated with co- and tri-agonist therapy (Samms et al. 2021). Moreover, the exact tissue and cell type of GIP signaling in WAT (identified as pericytes (Campbell et al. 2022)) responsible for changes in white fat mass or adipocyte size remains to be fully characterized, but it is likely that the contributions of GIPR may work independently of GLP-1R and Gcgr actions. Lastly, the independent effects of GIP signaling with dual and/or tri-agonism is yet to be fully determined in humans. However, clinical trials are currently being conducted to determine GIP’s effect on body weight loss and glucose control.

In vivo inhibition of GIPR in WAT

There have been extensive studies on the loss of function of GIPR and the effect on WAT. As GIP was classified as an obesogenic hormone (Goralska et al. 2018), these ideas are complemented by demonstrating that reducing Gipr content in the whole animal leads to a reduction in white adipocyte size and mass and overall WAT depot. However, this is only found in male mice being fed a HFD for an extended period of time of more than 20 weeks (Miyawaki et al. 2002). This led to the thought that perhaps the GIPR in WAT is a key component to overall body weight gain in mice. More recent research suggests that the GIPR is not expressed in white adipocytes (Campbell et al. 2022), posing an interesting interpretation of the data summarized below.

AT-specific GIPR knockout mice (Gipradipo−/−) fed a HFD have greater lean mass and lower body weight loss compared to floxed GIPR (Giprfl/fl) mice; however, no differences in subcutaneous and visceral fat masses are observed between groups, but liver volume, weight, and fat content were lower in male Gipradipo−/− HFD-fed mice (Joo et al. 2017). Furthermore, HFD-fed Gipradipo−/− mice showed significantly lower C-peptide and insulin levels, and body weight, with no changes in food intake, total GIP levels, and fed blood glucose levels compared to control mice (Joo et al. 2017). There were lower glucose excursions during glucose, insulin, and pyruvate tolerance tests in Gipradipo−/− compared to WT HFD-fed mice (Joo et al. 2017). These findings indicate that GIPR signaling in AT is independent of food intake regulation, but insulin and tissue response to glucose appear to be lower in mice without the GIPR in WAT. However, it is still not known if this effect is driven by lower body weight or circulating insulin levels. It is also important to note an important caveat of the model used to generate Gipradipo−/− mice was the Ap2/Fabp4-Cre promoter, which is known to drive unspecific effects in non-adipocyte tissues (Martens et al. 2010). Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that the insulin secretory response to GIP does increase food intake in WT mice fed a HFD, whereas this response is absent in WT mice fed a high-carbohydrate diet (Maekawa et al. 2018). However, these effects are not seen in whole-body GIPR-deficient mice, which show resistance to body weight gain. It remains unclear if the mechanism behind reducing GIPR action at the pancreas results in lower insulin levels that indirectly act to regulate WAT function, or if it is GIPR inhibition at the level of the whole WAT that regulates energy metabolism and insulin signaling. Moreover, the feeding centers of the brain may play a role in these effects. It has been reported that the increase in physiological GIP secretion due to overnutrition attenuates the suppressive effect on feeding by leptin in the hypothalamus (Kaneko et al. 2019). Thus, this may contribute to weight gain as there will be a diminished effect by the hypothalamus in controlling for food intake. As such, there may be complex mechanisms governing food intake in the hypothalamus through the interactions between leptin and GIPR, as both seem to play a role in regulating appetite and satiety. These findings suggest that GIP sensitivity in AT and pancreas, in addition to its direct effect on fat accumulation, plays a role in regulating body weight gain and food intake by GIP action in the hypothalamus (reviewed in Seino & Yamazaki (2022)).

Impaired AT function can significantly impact AT lipid metabolism, insulin sensitivity, and, ultimately, regulation of body weight (Chouchani & Kajimura 2019). Interrogation of the specific effects of AT GIPR was further demonstrated by Boer et al. 2021, where no differences were detected in FA oxidation and uptake in inguinal WAT (iWAT) isolated from male Gipr−/− and wild-type littermates on a 45% HFD. There was, however, an increase in iWAT and eWAT lipolysis in male Gipr−/− HFD-fed mice that were more exaggerated after β-adrenergic stimulation (Boer et al. 2021). Measurements of TG storage analyzed by 3H-labeled triolein in Gipr-/- mice were higher in iWAT, whereas there were no differences in TG storage in BAT and eWAT. The removal of GIPR in WAT may have depot-specific effects on the regulation of AT lipolysis and lipid storage but, again, it is difficult to determine if these are due to weight loss or insulin level differences detected between WT and Gipr−/− genotypes.

Similar to removing GIPR action in AT with the use of AT GIPR knockout mice models, studies have shown that GIPR antagonism lowers body weight in the face of HFD feeding (Lu et al. 2021). Paradoxically, both LA-GIPR agonist and muGIPR-Ab independently reduced weight gain in male DIO mice (Killion et al. 2018, 2020). Blocking GIPR using muGIPR-Ab did not affect food intake or FA uptake into primary mouse white adipocytes, while the LA-GIPR agonist decreased food intake from days 1 to 3 (Killion et al. 2020). Treatment with either LA-GIPR or muGIPR-Ab, in combination with liraglutide, a GLP-1R agonist, was better at reducing weight gain than muGIPR-Ab treatment alone in male DIO mice. Therefore, different mechanisms of action of GIPR agonist and antagonists may work independently to reduce body weight, but paired with a GLP-1R agonist, both provide integration at the level of the GIPR. It does appear that GIPR agonism results in increased levels of insulin secretion, whereas GIPR antagonism results in reduced levels of insulin (Killion et al. 2020), thereby suggesting a difference in plausible mechanisms of action, at least in the pancreatic beta cells. GIPR agonists have also been found to act as GIPR antagonists in WAT (lower GIPR expression than pancreatic islets), whereby GIPR agonism results in desensitization of GIPR activity (Killion et al. 2020). Moreover, when GIPR β-cell knockout mice (GiprβCell−/−) were compared to Giprfl/fl control mice, there were no differences in weight loss effects when treated with a HFD or when administered muGIPR-Ab alone, GLP-1R agonist, or in the combination (Killion et al. 2018), complementing data that GIPR in WAT may be partially responsible for lower body weight, independent of insulin signaling.

In humans, the use of the GIPR antagonist, GIP(3–30)NH2, alone or in combination with GIP, decreases AT TG uptake (Asmar et al. 2017). GIP(3–30)NH2 (800 pmol/kg/min) was assessed in healthy individuals and showed no changes in plasma TGs, glycerol, cholesterol, and NEFA content with GIP(3–30)NH2 alone or with a GIPR agonist (Gasbjerg et al. 2018). These data coincide with findings in lean subjects, where GIP infusion increases ATBF five-fold compared to vehicle control; however, when GIP was combined with GIP(3–30)NH2, the increase in ATBF was attenuated (Asmar et al. 2017). These studies support the hypothesis that WAT GIPR agonism is responsible for ATBF and lipid uptake. While most studies have assessed GIPR antagonism in rodent models, more work is needed to further elucidate the impact of GIPR antagonists in patients with T2D and obesity.

Altogether, these studies demonstrate the ambiguity surrounding the inhibition of GIPR and promoting GIP action to treat obesity and T2DM (these topics have been extensively reviewed by Killion et al. (2019), Campbell (2021), and Samms et al. (2020)). It remains unclear how to reduce fat mass in the most effective way while providing metabolic improvements. Recent advancements suggest that combining either GIPR agonism or antagonism with a GLP-1R agonist results in significant metabolic benefits that are superior to the mono-agonism of the incretin receptors (Tschop et al. 2023).

Brown adipose tissue

In vitro/in vivo effects of GIP

GipR mRNA levels are detected in immortalized cell lines and whole tissue explants of BAT, although they have low expression (cycle threshold levels around 29–31) (Adriaenssens et al. 2019, Beaudry et al. 2019). GIP treatment (4 h at a dose of 100 nM) in differentiated BAT cells increased gene markers of thermogenesis and inflammation, and lowered lipid storage expression levels (Beaudry et al. 2019). These findings indicate that GIP may regulate energy metabolism and thermogenic programming directly in BAT (Fig. 3). Acute and chronic administration of acyl-GIP (30 nmol/kg) to DIO mice showed no changes in whole-animal energy expenditure and had no effect on oxygen consumption in individual brown adipocytes (Zhang et al. 2021). However, acute administration of acyl-GIP (30 nmol/kg) decreased RER and increased FA oxidation, suggesting a preferential increase in whole-body lipid oxidation. Chronic acyl-GIP treatment (7 days) decreased both energy absorption and energy use, measured as ratios of food to fecal energy content (KJ/g of food), indicating reduced metabolizable energy stores in DIO mice. It remains unknown how and which tissues contribute to the GIP-induced rise in FA oxidation pathways detected in HFD obese rodents treated with exogenous GIP, but these appear to be independent of food intake and body weight lowering mechanisms of the brain (Zhang et al. 2021).

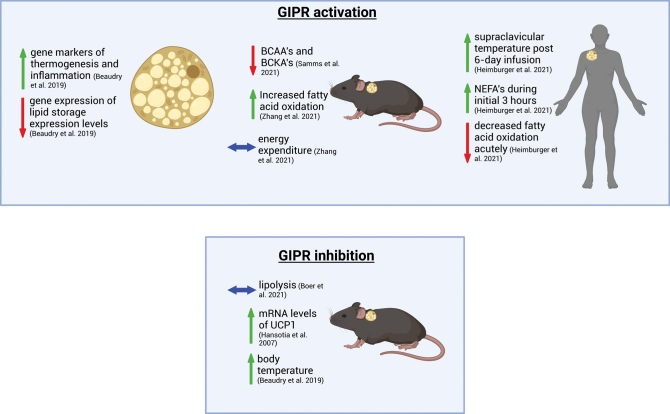

Figure 3.

Effects of GIPR activation and inhibition in cells, and BAT from rodents and humans. GIP treatment increases gene expression in thermogenic and inflammatory pathways, whereas genes related to lipid storage are reduced in BAT cells in vitro (Beaudry et al. 2019). Activation of the GIPR results in lower BCAA/BCKA ratios (Samms et al. 2022), decreased RER or increased FA oxidation, and no change in overall energy expenditure in vivo in mice (Zhang et al. 2021). GIP administration in humans increased supraclavicular temperature after 6 days of GIP infusion and NEFAs during the initial 3 h of treatment while acutely lowering fatty acid oxidation (Boer et al. 2021). GIPR BAT knock-out mice show an increase in mRNA UCP1 levels (Hansotia et al. 2007), decreased body weight when housed in chronic cold temperatures with no change in lipolysis. Fasted BAT GIPR knock-out mice increased body temperature in an acute cold challenge in vivo (Beaudry et al. 2019). Created in BioRender.

LA-GIPR agonist administration (300 nmol/kg; once daily for 14 days) changed regulatory genes in BAT of obese IR male mice with no changes in genes from skeletal muscle or WAT (Samms et al. 2021). The upregulated genes were associated with glucose oxidation, lipid, and branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) metabolism (Samms et al. 2021). Contributions of LA-GIPR agonists with GLP-1R may increase insulin sensitivity by improving energy metabolic pathways in BAT through upregulated gene expression. This increase in sensitivity may also be due to increased glucose uptake in visceral and subcutaneous AT independent of decreases in body weight and food intake. Moreover, treatment with tirzepatide or a LA-GIPR agonist in obese and IR mice decreased branched-chain amino acids/branched-chain keto acids (BCAAs/BCKAs) and greatly increased the expression of genes related to BCAA catabolism (Samms et al. 2021). Interestingly, tirzepatide appears to enhance insulin sensitivity much greater than a GLP-1R agonist alone and increases amino acid pools in BAT that phenotypically mimic thermogenically active BAT (Samms et al. 2022). Furthermore, obese mice given tirzepatide for 2 weeks at 10 nmol/kg stimulated the catabolism of BCAA/BCKA in BAT and increased the breakdown of BCAA by-products compared to controls and pair-feeding controls (Samms et al. 2022). This suggests that BAT is directly affected by tirzepatide independent of body weight loss. This work presents novel findings showing that tirzepatide improves insulin sensitivity in male DIO mice potentially through BAT-mediated mechanisms. Moreover, in recent literature, using chronic dosing of a LA-GIPR at 10 nmol/kg for 14 days showed increased glucose disposal in BAT and gene expression levels of markers in browning of WAT, lower TCA cycle flux, and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation pathways in BAT. This was further demonstrated by LA-GIPR treatment that provides protection against rosiglitazone-induced weight gain and systemic insulin resistance (Furber et al. 2023). It remains unclear if the effects of GIP in vivo modulate BAT energy substrate usage in humans, as no studies, at least to our knowledge, have examined GIPR expression or performed direct experiments in vitro/ex vivo experiments with GIP treatment in human BAT cells.

There is a study that has focused on the GIPR and BAT activity in men with T1DM. They were administered a 6-day subcutaneous GIP infusion (6 pmol/kg/min) and found no increase in BAT activity (supraclavicular skin temperature) after acute (120 min) treatment compared to the placebo (Heimburger et al. 2022). However, there was an increase in supraclavicular skin temperature post-6-day infusion, suggesting that GIP may be playing a role in regulating BAT thermogenesis in humans (Heimburger et al. 2022). There was a decrease in RER at 150 min, suggesting that GIP infusion increases FA oxidation, at least for a short period after administration as this effect was not sustained (Heimburger et al. 2022). Moreover, no changes were observed in TG and glycerol concentrations, fasting plasma levels of C-peptide or insulin, while NEFAs increased during the initial 3 h post-acute subcutaneous GIP infusion (two to three times the normal physiological postprandial levels), possibly indicating increased AT lipolysis. Therefore, GIP appears to be playing a role in BAT thermogenic activity, which may have implications for the treatment of metabolic disorders. More work needs to be done to assess whether the observed increase in BAT activity post 6-day GIP infusion is sustained and whether GIP can induce lasting changes in thermogenesis of BAT.

In vitro/in vivo inhibition of GIP

In 2002, the whole-body Gipr−/− mouse model suggested that GIP is involved in obesogenic signaling pathways, as mice were found to be resistant to DIO when fed a HFD for >20 weeks (Miyawaki et al. 2002). Moreover, as previously discussed in the above sections, insulin receptor substrate-1 and GIPR appear to be reflective of insulin sensitivity. For example, under impaired insulin signaling, GIP increased fat uptake into adipocytes, and inhibiting insulin and GIP signaling reduced fat accumulation into adipocytes and promoted fat oxidation in the liver and skeletal muscle (Zhou et al. 2005). Nonetheless, these results remain unclear as the actions of GIP in the liver and skeletal muscle are known to be an indirect result of GIPR expression. Moreover, only subcutaneous and visceral WATs were examined in the Gipr−/− mice until one study found a significant decrease in BAT weight and increase in BAT UCP1 mRNA levels in Gipr−/− mice compared to WT mice fed a HFD (Hansotia et al. 2007). Interestingly, Gipr−/− mice gain weight similar to WT mice when fed a HFD while being housed at thermal neutrality, indicating the effects of thermal stress in these mice (Furber et al. 2023). These findings suggest that inhibition of the GIPR in BAT may be important for regulating weight gain or systemic insulin sensitivity.

Surprisingly, male HFD-induced obese mice housed at room temperature lacking GIPR in their BAT (GiprBAT−/−) showed no differences in fat and lean mass, body weight, food intake, basal energy expenditure, AT or organ weights compared to littermate controls (Beaudry et al. 2019). These findings suggest that BAT GIPR does not contribute to the lowering of body weight as observed in Gipr−/− HFD-fed mice. However, fasted GiprBAT−/− mice exhibited elevated body temperature and maintained their temperature during an acute cold challenge, suggesting that these mice can still regulate their body temperature during cold exposure (Beaudry et al. 2019). Administering CL316, 243 (1 mg/kg), a β-3-adrenergic receptor agonist twice daily to GiprBAT−/− mice for 3 days showed no differences in energy expenditure, RER, or activity levels in mice, but increased lipid excursions during a lipid challenge, indicating impaired lipid tolerance when housed at room temperature. These mice lost body weight, increased BAT oxygen consumption, lowered BAT weight and adipocyte size, and improved lipid tolerance when housed in the cold for 12 weeks. From this work, it appears that inhibition of BAT GIPR in the cold is linked to fuel utilization, oxygen consumption, and thermogenic gene expression, rather than the regulation of body weight, fat, and/or lean mass. Furthermore, it is unknown if increases in endogenous GIP production impairs thermogenic function; however, this would appear to be unlikely as GIPR agonism promotes BAT thermogenic signatures (Samms et al. 2021).

When DIO mice were pre-treated with vehicle or mu-GIPR-Ab (25 mg/kg) for 24 h, and then with saline or GIP (D-Ala2-GIP; shorter-acting GIPR agonist compared to acyl-GIP), no changes in FA uptake in BAT were observed (Killion et al. 2020). Furthermore, [3H]triolein storage and lipolysis did not differ between Gipr−/− and WT littermates in BAT when fed a HFD (Boer et al. 2021), suggesting that the absence of GIPR had no effect on fat storage or breakdown in BAT. Lastly, follow-up experiments showed no changes in stimulated or basal lipolysis in BAT in ex vivo experiments from HFD WT mice given GIP (200 and 1000 pM).

Together, these data suggest that the inhibition of GIPR in BAT is an interplay between various AT depots regulating energy utilization. They may explain changes in overall body weight when mice are provided excessive calories, i.e. HFD feeding or access to cold stimulation. GIPR activation and inhibition of GIPR signaling appears to act through different mechanisms in the BAT than in WAT, depending on housing and metabolic conditions; therefore, interpretation of the data needs to be carefully considered when assessing the effects on whole-body energy metabolism.

Conclusion

The relationship between GIP and AT in metabolism, health, and disease is an important one that remains complex and is a rapidly evolving field of study, with future work further exploring the interplay of agonists and antagonists and examining potential sex-specific differences. The exact mechanisms of GIP on AT are not totally understood, as distinct depots present different actions of GIP and the adipogenic actions of GIP appear to differ based on the presence or absence of insulin, metabolic status of the individual (lean vs obese), and housing environments. More work is needed to determine the role of GIP at the level of the WAT and BAT to differentiate the metabolic actions of GIP from GLP-1 and glucagon. However, as co-agonist and tri-agonist GIPR-based therapies have shown reductions in body weight and improvement in lipid profiles in cellular, mouse, and human models, ongoing research opens many doors for understanding the underlying metabolic processes and developing therapies to address the health concerns of obesity and T2DM.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of this review.

Funding

This work was supported in part by various funds, including CIHR Project Grant 486421, Banting & Best Diabetes Centre; Novo Nordisk-BBDC Pilot and Feasibility Grant 2022-23, Novo Nordisk-BBDC New Investigator Award 2023-25, and Drucker Family Innovation Fund Grant 2023-24. SK has received a fellowship from the Banting & Best Diabetes Centre-Novo Nordisk Graduate Studentship 2023-24. SL has received a fellowship from the Banting & Best Diabetes Centre, DH Gales Family Charitable Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship 2022-23.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Negar Mir who also contributed to the editing of the manuscript and figure preparation.

References

- Adriaenssens AE, Biggs EK, Darwish T, Tadross J, Sukthankar T, Girish M, Polex-Wolf J, Lam BY, Zvetkova I, Pan W, et al.2019Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide receptor-expressing cells in the hypothalamus regulate food intake. Cell Metabolism 30987–996.e6. ( 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.07.013) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aroda VR & Ratner R. 2011The safety and tolerability of GLP-1 receptor agonists in the treatment of type 2 diabetes: a review. Diabetes/Metabolism Research and Reviews 27528–542. ( 10.1002/dmrr.1202) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asmar M Simonsen L Madsbad S Stallknecht B Holst JJ & Bulow J. 2010Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide may enhance fatty acid re-esterification in subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissue in lean humans. Diabetes 592160–2163. ( 10.2337/db10-0098) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asmar M Simonsen L Arngrim N Holst JJ Dela F & Bulow J. 2014Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide has impaired effect on abdominal, subcutaneous adipose tissue metabolism in obese subjects. International Journal of Obesity 38259–265. ( 10.1038/ijo.2013.73) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asmar M Arngrim N Simonsen L Asmar A Nordby P Holst JJ & Bulow J. 2016aThe blunted effect of glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide in subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissue in obese subjects is partly reversed by weight loss. Nutrition and Diabetes 6e208. ( 10.1038/nutd.2016.15) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asmar M Simonsen L Asmar A Holst JJ Dela F & Bulow J. 2016bInsulin plays a permissive role for the vasoactive effect of GIP regulating adipose tissue metabolism in humans. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 1013155–3162. ( 10.1210/jc.2016-1933) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asmar M Asmar A Simonsen L Gasbjerg LS Sparre-Ulrich AH Rosenkilde MM Hartmann B Dela F Holst JJ & Bulow J. 2017The gluco- and liporegulatory and vasodilatory effects of glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) are abolished by an antagonist of the human GIP receptor. Diabetes 662363–2371. ( 10.2337/db17-0480) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asmar M Asmar A Simonsen L Dela F Holst JJ & Bulow J. 2019GIP-induced vasodilation in human adipose tissue involves capillary recruitment. Endocrine Connections 8806–813. ( 10.1530/EC-19-0144) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey CJ Flatt PR & Conlon JM. 2023An update on peptide-based therapies for type 2 diabetes and obesity. Peptides 161170939. ( 10.1016/j.peptides.2023.170939) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaudry JL Kaur KD Varin EM Baggio LL Cao X Mulvihill EE Bates HE Campbell JE & Drucker DJ. 2019Physiological roles of the GIP receptor in murine brown adipose tissue. Molecular Metabolism 2814–25. ( 10.1016/j.molmet.2019.08.006) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becher T, Palanisamy S, Kramer DJ, Eljalby M, Marx SJ, Wibmer AG, Butler SD, Jiang CS, Vaughan R, Schoder H, et al.2021Brown adipose tissue is associated with cardiometabolic health. Nature Medicine 2758–65. ( 10.1038/s41591-020-1126-7) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettge K Kahle M Abd El Aziz MS Meier JJ & Nauck MA. 2017Occurrence of nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea reported as adverse events in clinical trials studying glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists: a systematic analysis of published clinical trials. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism 19336–347. ( 10.1111/dom.12824) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boer GA Keenan SN Miotto PM Holst JJ & Watt MJ. 2021GIP receptor deletion in mice confers resistance to HFD-induced obesity via alterations in energy expenditure and adipose tissue lipid metabolism. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism 320E835–E845. ( 10.1152/ajpendo.00646.2020) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borner T, Geisler CE, Fortin SM, Cosgrove R, Alsina-Fernandez J, Dogra M, Doebley S, Sanchez-Navarro MJ, Leon RM, Gaisinsky J, et al., et al.2021GIP receptor agonism attenuates GLP-1 receptor agonist-induced nausea and emesis in preclinical models. Diabetes 702545–2553. ( 10.2337/db21-0459) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JC & Pederson RA. 1970A multiparameter study on the action of preparations containing cholecystokinin-pancreozymin. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology 5537–541. ( 10.1080/00365521.1970.12096632) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JE.2021Targeting the GIPR for obesity: to agonize or antagonize? Potential mechanisms. Molecular Metabolism 46101139. ( 10.1016/j.molmet.2020.101139) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JE, Ussher JR, Mulvihill EE, Kolic J, Baggio LL, Cao X, Liu Y, Lamont BJ, Morii T, Streutker CJ, et al.2016TCF1 links GIPR signaling to the control of beta cell function and survival. Nature Medicine 2284–90. ( 10.1038/nm.3997) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JE, Beaudry JL, Svendsen B, Baggio LL, Gordon AN, Ussher JR, Wong CK, Gribble FM, D'Alessio DA, Reimann F, et al.2022The GIPR is predominantly localized to non-adipocyte cell types within white adipose tissue. Diabetes 711115–1127. ( 10.2337/db21-1166) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon B & Nedergaard J. 2004Brown adipose tissue: function and physiological significance. Physiological Reviews 84277–359. ( 10.1152/physrev.00015.2003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K Pittman RN & Popel AS. 2008Nitric oxide in the vasculature: where does it come from and where does it go? A quantitative perspective. Antioxidants and Redox Signaling 101185–1198. ( 10.1089/ars.2007.1959) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe SS Huh JY Hwang IJ Kim JI & Kim JB. 2016Adipose tissue remodeling: its role in energy metabolism and metabolic disorders. Frontiers in Endocrinology (Lausanne) 730. ( 10.3389/fendo.2016.00030) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chouchani ET & Kajimura S. 2019Metabolic adaptation and maladaptation in adipose tissue. Nature Metabolism 1189–200. ( 10.1038/s42255-018-0021-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daval M Foufelle F & Ferre P. 2006Functions of AMP-activated protein kinase in adipose tissue. Journal of Physiology 57455–62. ( 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.111484) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupre J Ross SA Watson D & Brown JC. 1973Stimulation of insulin secretion by gastric inhibitory polypeptide in man. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 37826–828. ( 10.1210/jcem-37-5-826) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finan B & Douros JD. 2022GLP-1/GIP/glucagon receptor triagonism gets its try in humans. Cell Metabolism 343–4. ( 10.1016/j.cmet.2021.12.010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finan B, Ma T, Ottaway N, Muller TD, Habegger KM, Heppner KM, Kirchner H, Holland J, Hembree J, Raver C, et al.2013Unimolecular dual incretins maximize metabolic benefits in rodents, monkeys, and humans. Science Translational Medicine 5209ra151. ( 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007218) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finan B, Yang B, Ottaway N, Smiley DL, Ma T, Clemmensen C, Chabenne J, Zhang L, Habegger KM, Fischer K, et al.2015A rationally designed monomeric peptide triagonist corrects obesity and diabetes in rodents. Nature Medicine 2127–36. ( 10.1038/nm.3761) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finan B Muller TD Clemmensen C Perez-Tilve D DiMarchi RD & Tschop MH. 2016Reappraisal of GIP pharmacology for metabolic diseases. Trends in Molecular Medicine 22359–376. ( 10.1016/j.molmed.2016.03.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frías JP, Davies MJ, Rosenstock J, Pérez Manghi FC, Fernández Landó L, Bergman BK, Liu B, Cui X, Brown K. & SURPASS-2 Investigators 2021Tirzepatide versus semaglutide once weekly in patients with type 2 diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine 385503–515. ( 10.1056/NEJMoa2107519) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furber EC, Hyatt K, Collins K, Yu X, Droz BA, Holland A, Friedrich JL, Wojnicki S, Konkol DL, O'Farrell LS, et al.2023GIPR agonism enhances TZD-induced insulin sensitivity in obese IR mice. Diabetes 73292–305. ( 10.2337/db23-0172) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasbjerg LS, Christensen MB, Hartmann B, Lanng AR, Sparre-Ulrich AH, Gabe MBN, Dela F, Vilsboll T, Holst JJ, Rosenkilde MM, et al.2018GIP(3-30)NH(2) is an efficacious GIP receptor antagonist in humans: a randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Diabetologia 61413–423. ( 10.1007/s00125-017-4447-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getty-Kaushik L Song DH Boylan MO Corkey BE & Wolfe MM. 2006Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide modulates adipocyte lipolysis and reesterification. Obesity 141124–1131. ( 10.1038/oby.2006.129) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goossens GH & Blaak EE. 2015Adipose tissue dysfunction and impaired metabolic health in human obesity: a matter of oxygen? Frontiers in Endocrinology (Lausanne) 655. ( 10.3389/fendo.2015.00055) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goralska J, Razny U, Polus A, Stancel-Mozwillo J, Chojnacka M, Gruca A, Zdzienicka A, Dembinska-Kiec A, Kiec-Wilk B, Solnica B, et al.2018Pro-inflammatory gene expression profile in obese adults with high plasma GIP levels. International Journal of Obesity 42826–834. ( 10.1038/ijo.2017.305) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammoud R & Drucker DJ. 2022Beyond the pancreas: contrasting cardiometabolic actions of GIP and GLP1. Nature Reviews. Endocrinology 19201–216. ( 10.1038/s41574-022-00783-3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han W, Wang L, Ohbayashi K, Takeuchi M, O'Farrell L, Coskun T, Rakhat Y, Yabe D, Iwasaki Y, Seino Y, et al.2023Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide counteracts diet-induced obesity along with reduced feeding, elevated plasma leptin and activation of leptin-responsive and proopiomelanocortin neurons in the arcuate nucleus. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism 251534–1546. ( 10.1111/dom.15001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansotia T Maida A Flock G Yamada Y Tsukiyama K Seino Y & Drucker DJ. 2007Extrapancreatic incretin receptors modulate glucose homeostasis, body weight, and energy expenditure. Journal of Clinical Investigation 117143–152. ( 10.1172/JCI25483) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimburger SM Bergmann NC Augustin R Gasbjerg LS Christensen MB & Knop FK. 2020Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) and cardiovascular disease. Peptides 125170174. ( 10.1016/j.peptides.2019.170174) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimburger SMN, Hoe B, Nielsen CN, Bergman NC, Skov-Jeppesen K, Hartmann B, Holst JJ, Dela F, Overgaard J, Storling J, et al.2022GIP affects hepatic fat and brown adipose tissue thermogenesis, but not white adipose tissue transcriptome in T1D. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 1073261–3274. ( 10.1210/clinem/dgac542) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu D Remash D Russell RD Greenaway T Rattigan S Squibb KA Jones G Premilovac D Richards SM & Keske MA. 2018Impairments in adipose tissue microcirculation in type 2 diabetes mellitus assessed by real-time contrast-enhanced ultrasound. Circulation. Cardiovascular Imaging 11e007074. ( 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.117.007074) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin N & Flatt PR. 2009Therapeutic potential for GIP receptor agonists and antagonists. Best Practice and Research. Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 23499–512. ( 10.1016/j.beem.2009.03.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jastreboff AM, Kaplan LM, Frías JP, Wu Q, Du Y, Gurbuz S, Coskun T, Haupt A, Milicevic Z, Hartman ML, et al.2023Triple-hormone-receptor agonist Retatrutide for obesity - A Phase 2 trial. New England Journal of Medicine 389514–526. ( 10.1056/NEJMoa2301972) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joo E, Harada N, Yamane S, Fukushima T, Taura D, Iwasaki K, Sankoda A, Shibue K, Harada T, Suzuki K, et al.2017Inhibition of gastric inhibitory polypeptide receptor signaling in adipose tissue reduces insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis in high-fat diet-fed mice. Diabetes 66868–879. ( 10.2337/db16-0758) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko K, Fu Y, Lin HY, Cordonier EL, Mo Q, Gao Y, Yao T, Naylor J, Howard V, Saito K, et al.2019Gut-derived GIP activates central Rap1 to impair neural leptin sensitivity during overnutrition. Journal of Clinical Investigation 1293786–3791. ( 10.1172/JCI126107) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieffer TJ McIntosh CH & Pederson RA. 1995Degradation of glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide and truncated glucagon-like peptide 1 in vitro and in vivo by dipeptidyl peptidase IV. Endocrinology 1363585–3596. ( 10.1210/endo.136.8.7628397) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killion EA, Wang J, Yie J, Shi SD, Bates D, Min X, Komorowski R, Hager T, Deng L, Atangan L, et al.2018Anti-obesity effects of GIPR antagonists alone and in combination with GLP-1R agonists in preclinical models. Science Translational Medicine 10. ( 10.1126/scitranslmed.aat3392) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killion EA Lu SC Fort M Yamada Y Veniant MM & Lloyd DJ. 2019Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide receptor therapies for the treatment of obesity, do agonists = antagonists? Endocrine Reviews 41. ( 10.1210/endrev/bnz002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killion EA, Chen M, Falsey JR, Sivits G, Hager T, Atangan L, Helmering J, Lee J, Li H, Wu B, et al.2020Chronic glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide receptor (GIPR) agonism desensitizes adipocyte GIPR activity mimicking functional GIPR antagonism. Nature Communications 114981. ( 10.1038/s41467-020-18751-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SJ Nian C & McIntosh CH. 2007Activation of lipoprotein lipase by glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide in adipocytes. A role for a protein kinase B, LKB1, and AMP-activated protein kinase cascade. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2828557–8567. ( 10.1074/jbc.M609088200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SJ Nian C Karunakaran S Clee SM Isales CM & McIntosh CH. 2012GIP-overexpressing mice demonstrate reduced diet-induced obesity and steatosis, and improved glucose homeostasis. PLoS One 7e40156. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0040156) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knerr PJ, Mowery SA, Douros JD, Premdjee B, Hjollund KR, He Y, Kruse Hansen AM, Olsen AK, Perez-Tilve D, DiMarchi RD, et al.2022Next generation GLP-1/GIP/glucagon triple agonists normalize body weight in obese mice. Molecular Metabolism 63101533. ( 10.1016/j.molmet.2022.101533) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liskiewicz A, Khalil A, Liskiewicz D, Novikoff A, Grandl G, Maity-Kumar G, Gutgesell RM, Bakhti M, Bastidas-Ponce A, Czarnecki O, et al.2023Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide regulates body weight and food intake via GABAergic neurons in mice. Nature Metabolism 52075–2085. ( 10.1038/s42255-023-00931-7) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu SC, Chen M, Atangan L, Killion EA, Komorowski R, Cheng Y, Netirojjanakul C, Falsey JR, Stolina M, Dwyer D, et al.2021GIPR antagonist antibodies conjugated to GLP-1 peptide are bispecific molecules that decrease weight in obese mice and monkeys. Cell Reports. Medicine 2100263. ( 10.1016/j.xcrm.2021.100263) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maekawa R, Ogata H, Murase M, Harada N, Suzuki K, Joo E, Sankoda A, Iida A, Izumoto T, Tsunekawa S, et al.2018Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide is required for moderate high-fat diet- but not high-carbohydrate diet-induced weight gain. American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism 314E572–E583. ( 10.1152/ajpendo.00352.2017) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens K Bottelbergs A & Baes M. 2010Ectopic recombination in the central and peripheral nervous system by aP2/FABP4-Cre mice: implications for metabolism research. FEBS Letters 5841054–1058. ( 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.01.061) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh CH Bremsak I Lynn FC Gill R Hinke SA Gelling R Nian C McKnight G Jaspers S & Pederson RA. 1999Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide stimulation of lipolysis in differentiated 3T3-L1 cells: wortmannin-sensitive inhibition by insulin. Endocrinology 140398–404. ( 10.1210/endo.140.1.6464) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean BA Wong CK Kaur KD Seeley RJ & Drucker DJ. 2021Differential importance of endothelial and hematopoietic cell GLP-1Rs for cardiometabolic versus hepatic actions of semaglutide. JCI Insight 6. ( 10.1172/jci.insight.153732) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mentlein R Gallwitz B & Schmidt WE. 1993Dipeptidyl-peptidase IV hydrolyses gastric inhibitory polypeptide, glucagon-like peptide-1(7-36)amide, peptide histidine methionine and is responsible for their degradation in human serum. European Journal of Biochemistry 214829–835. ( 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17986.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyawaki K, Yamada Y, Ban N, Ihara Y, Tsukiyama K, Zhou H, Fujimoto S, Oku A, Tsuda K, Toyokuni S, et al.2002Inhibition of gastric inhibitory polypeptide signaling prevents obesity. Nature Medicine 8738–742. ( 10.1038/nm727) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammad S Patel RT Bruno J Panhwar MS Wen J & McGraw TE. 2014A naturally occurring GIP receptor variant undergoes enhanced agonist-induced desensitization, which impairs GIP control of adipose insulin sensitivity. Molecular and Cellular Biology 343618–3629. ( 10.1128/MCB.00256-14) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller TD Bluher M Tschop MH & DiMarchi RD. 2022Anti-obesity drug discovery: advances and challenges. Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery 21201–223. ( 10.1038/s41573-021-00337-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naslund E Barkeling B King N Gutniak M Blundell JE Holst JJ Rossner S & Hellstrom PM. 1999Energy intake and appetite are suppressed by glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) in obese men. International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders 23304–311. ( 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800818) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nauck M Stockmann F Ebert R & Creutzfeldt W. 1986Reduced incretin effect in type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes. Diabetologia 2946–52. ( 10.1007/BF02427280) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstock J, Frias J, Jastreboff AM, Du Y, Lou J, Gurbuz S, Thomas MK, Hartman ML, Haupt A, Milicevic Z, et al.2023Retatrutide, a GIP, GLP-1 and glucagon receptor agonist, for people with type 2 diabetes: a randomised, double-blind, placebo and active-controlled, parallel-group, phase 2 trial conducted in the USA. Lancet 402529–544. ( 10.1016/S0140-6736(2301053-X) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samms RJ Coghlan MP & Sloop KW. 2020How may GIP enhance the therapeutic efficacy of GLP-1? Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism 31410–421. ( 10.1016/j.tem.2020.02.006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samms RJ, Christe ME, Collins KA, Pirro V, Droz BA, Holland AK, Friedrich JL, Wojnicki S, Konkol DL, Cosgrove R, et al.2021GIPR agonism mediates weight-independent insulin sensitization by tirzepatide in obese mice. Journal of Clinical Investigation 131. ( 10.1172/JCI146353) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samms RJ, Zhang G, He W, Ilkayeva O, Droz BA, Bauer SM, Stutsman C, Pirro V, Collins KA, Furber EC, et al.2022Tirzepatide induces a thermogenic-like amino acid signature in brown adipose tissue. Molecular Metabolism 64101550. ( 10.1016/j.molmet.2022.101550) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seino Y Fukushima M & Yabe D. 2010GIP and GLP-1, the two incretin hormones: similarities and differences. Journal of Diabetes Investigation 18–23. ( 10.1111/j.2040-1124.2010.00022.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seino Y & Yamazaki Y. 2022Roles of glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide in diet-induced obesity. Journal of Diabetes Investigation 131122–1128. ( 10.1111/jdi.13816) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi Y, Fujita H, Seino Y, Hattori S, Hidaka S, Miyakawa T, Suzuki A, Waki H, Yabe D, Seino Y, et al.2023Gastric inhibitory polypeptide receptor antagonism suppresses intramuscular adipose tissue accumulation and ameliorates sarcopenia. Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle 142703–2718. ( 10.1002/jcsm.13346) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thondam SK Daousi C Wilding JP Holst JJ Ameen GI Yang C Whitmore C Mora S & Cuthbertson DJ. 2017Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide promotes lipid deposition in subcutaneous adipocytes in obese type 2 diabetes patients: a maladaptive response. American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism 312E224–E233. ( 10.1152/ajpendo.00347.2016) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobin L Simonsen L & Bulow J. 2010Real-time contrast-enhanced ultrasound determination of microvascular blood volume in abdominal subcutaneous adipose tissue in man. Evidence for adipose tissue capillary recruitment. Clinical Physiology and Functional Imaging 30447–452. ( 10.1111/j.1475-097X.2010.00964.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschop M Nogueiras R & Ahren B. 2023Gut hormone-based pharmacology: novel formulations and future possibilities for metabolic disease therapy. Diabetologia 661796–1808. ( 10.1007/s00125-023-05929-0) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ugleholdt R Poulsen ML Holst PJ Irminger JC Orskov C Pedersen J Rosenkilde MM Zhu X Steiner DF & Holst JJ. 2006Prohormone convertase 1/3 is essential for processing of the glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide precursor. Journal of Biological Chemistry 28111050–11057. ( 10.1074/jbc.M601203200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usdin TB Mezey E Button DC Brownstein MJ & Bonner TI. 1993Gastric inhibitory polypeptide receptor, a member of the secretin-vasoactive intestinal peptide receptor family, is widely distributed in peripheral organs and the brain. Endocrinology 1332861–2870. ( 10.1210/endo.133.6.8243312) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varol C Zvibel I Spektor L Mantelmacher FD Vugman M Thurm T Khatib M Elmaliah E Halpern Z & Fishman S. 2014Long-acting glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide ameliorates obesity-induced adipose tissue inflammation. Journal of Immunology 1934002–4009. ( 10.4049/jimmunol.1401149) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilsboll T Krarup T Madsbad S & Holst JJ. 2002Defective amplification of the late phase insulin response to glucose by GIP in obese type II diabetic patients. Diabetologia 451111–1119. ( 10.1007/s00125-002-0878-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilsboll T Agerso H Lauritsen T Deacon CF Aaboe K Madsbad S Krarup T & Holst JJ. 2006The elimination rates of intact GIP as well as its primary metabolite, GIP 3–42, are similar in type 2 diabetic patients and healthy subjects. Regulatory Peptides 137168–172. ( 10.1016/j.regpep.2006.07.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wibmer AG Becher T Eljalby M Crane A Andrieu PC Jiang CS Vaughan R Schoder H & Cohen P. 2021Brown adipose tissue is associated with healthier body fat distribution and metabolic benefits independent of regional adiposity. Cell Reports. Medicine 2100332. ( 10.1016/j.xcrm.2021.100332) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Delessa CT, Augustin R, Bakhti M, Collden G, Drucker DJ, Feuchtinger A, Caceres CG, Grandl G, Harger A, et al.2021The glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) regulates body weight and food intake via CNS-GIPR signaling. Cell Metabolism 33833–844.e5. ( 10.1016/j.cmet.2021.01.015) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H, Yamada Y, Tsukiyama K, Miyawaki K, Hosokawa M, Nagashima K, Toyoda K, Naitoh R, Mizunoya W, Fushiki T, et al.2005Gastric inhibitory polypeptide modulates adiposity and fat oxidation under diminished insulin action. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 335937–942. ( 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.07.164) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a