Abstract

The accurate potential energy function of magnesium monohydride in its X2Σ+ state has been determined from ab initio calculations. The vibration–rotation energy levels of the main isotopologue 24MgH were predicted to near the “spectroscopic” accuracy. The scalar relativistic, adiabatic, and nonadiabatic effects were discussed.

Introduction

Magnesium monohydride, MgH, is the only metal hydride known for which all of the vibration–rotation energy levels of the ground electronic state X2Σ+, up to the dissociation limit, were characterized by high-resolution spectroscopy. For perhaps the most complete review of numerous experimental spectroscopic studies on magnesium monohydride, the reader is referred to the recent work by Owens et al.1 The exhaustive experimental studies on the vibration–rotation energy levels of the isotopologues 24MgH and 24MgD were reported by Shayesteh et al.2,3 Those studies were further extended by Henderson et al.4 to include the species with magnesium minor isotopes 25Mg and 26Mg. The potential energy function of MgH in the X2Σ+ state was determined in a multi-isotopologue direct-potential-fit analysis. In particular, the binding energy De and equilibrium internuclear distance re of the main isotopologue 24MgH were derived to be 11,104.25 ± 0.8 cm–1 and 1.7296854 ± 0.0000007 Å, respectively.

The MgH radical was also the subject of numerous theoretical studies,5−19 and its electronic structure in the ground and excited electronic states was characterized at various levels of theory. In the most extensive studies to date,15−19 the potential energy functions for various electronic states of MgH were determined using the multireference configuration interaction (MRCI) method with correlation-consistent basis sets up to quintuple-zeta quality. Despite the high level of theory applied in those studies, the binding energy De and equilibrium internuclear distance re of MgH in the X2Σ+ state were found to span rather wide ranges 11,000–11,600 cm–1 and 1.729–1.744 Å, respectively. The experimental vibrational fundamental wavenumber ν of 1432 cm–1 (ref (2)) was also poorly reproduced, with the predicted values spanning the range of 1427–1438 cm–1. Given the progress in theoretical spectroscopy, such a situation is somewhat disappointing at present.

The aim of this work is to provide the accurate state-of-the-art potential energy function for the ground electronic state of MgH and to discuss the effects which should be taken into account in order to predict the vibration–rotation energy levels of MgH to near the “spectroscopic” accuracy.

Method of Calculation

The molecular parameters of MgH in the X2Σ+ state were determined using the multireference averaged coupled-pair functional (MR-ACPF) method20,21 in conjunction with the augmented correlation-consistent core–valence basis sets up to octuple-zeta quality, aug-cc-pCVnZ (n = 5–8). The calculations consisted of two steps: the complete-active-space self-consistent-field (CASSCF) step, followed by the internally contracted22 MR-ACPF step. The usual full-valence active space, including the 3s- and 3p-like orbitals of the magnesium atom and the 1s-like orbital of the hydrogen atom, was extended with the 4s-, 4p-, and 3d-like orbitals of the magnesium atom. The CASSCF wave function of MgH included thus all excitations of three valence electrons in 14 molecular orbitals. In the vicinity of the equilibrium configuration of MgH, the occupancy of highest-energy active natural orbitals of the CASSCF wave function was about 0.0003e. In the generation of the CASSCF wave functions, the 1s-, 2s-, and 2p-like core orbitals of the magnesium atom were optimized, but they were kept doubly occupied. The reference function for the MR-ACPF step consisted of 263 configuration state functions. In this step, all but magnesium 1s electrons (11 electrons) were correlated with single and double excitations. The dynamical correlation effects of deep-core magnesium 1s electrons were thus neglected. The calculations were performed using the MOLPRO package of ab initio programs23 unless otherwise noted.

The core–valence basis sets cc-pCVnZ for magnesium were developed, up to quintuple-zeta quality, by Prascher et al.24 The larger basis sets of sextuple- through octuple-zeta quality were developed for the previous study on magnesium monohydroxide.25 For the sake of consistency, the quintuple-zeta quality basis set for magnesium was reoptimized. The cc-pCV5Z basis set for magnesium consists of a (20s, 14p, 8d, 6f, 4g, 2h) set contracted to a [11s, 10p, 8d, 6f, 4g, 2h] set. The cc-pCV6Z basis set consists of a (23s, 16p, 10d, 8f, 6g, 4h, 2i) set contracted to a [13s, 12p, 10d, 8f, 6g, 4h, 2i] set. The cc-pCV7Z basis set consists of a (26s, 18p, 12d, 10f, 8g, 6h, 4i, 2k) set contracted to a [15s, 14p, 12d, 10f, 8g, 6h, 4i, 2k] set. Also, the cc-pCV8Z basis set consists of a (29s, 20p, 14d, 12f, 10g, 8h, 6i, 4k, 2l) set contracted to a [17s, 16p, 14d, 12f, 10g, 8h, 6i, 4k, 2l] set. The diffuse functions (aug) were taken as the customary even-tempered functions with a multiplicative factor of 0.4. Further details of these new core–valence basis sets for magnesium will be reported elsewhere. The valence basis sets aug-cc-pVnZ for hydrogen were taken from the literature.26,27 Because the MOLPRO package cannot handle functions higher than i, the k and l polarization functions were omitted in the multireference calculations.

The vibration–rotation energy levels of magnesium monohydride were calculated using the Numerov–Cooley method.28 The energy levels were calculated using the nuclear masses of magnesium and hydrogen.

Results and Discussion

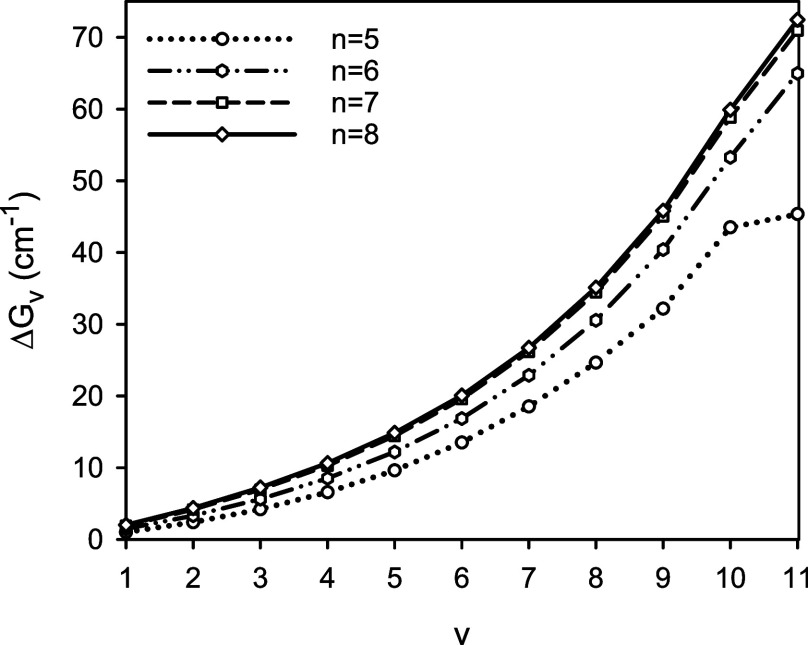

To determine the potential energy function of MgH in the X2Σ+ state, the total energies were calculated at the MR-ACPF/aug-cc-pCVnZ (n = 5–8) level of theory at 66 internuclear distances ranging from 0.9 to 50 Å. The vibration–rotation energy levels of the main isotopologue 24MgH were then calculated for the rotational quantum number N ranging from 0 to 3. The equilibrium internuclear distance re was determined by fitting the predicted total energies, in the close vicinity of the minimum, with a polynomial expansion. For a given vibrational state, the effective rotational constant Bv and quartic centrifugal distortion constant Dv were determined by fitting the predicted rotational energies with a power series in N(N + 1). The predicted molecular parameters are given in Table 1. The predicted values tend clearly to converge with enlargement of the one-particle basis set. The total energy at a minimum E is converged to better than 0.6 mEh. Concerning the basis set size, the best predicted binding energy De and the equilibrium distance re are estimated to be accurate to about ±2 cm–1 and ±0.0001 Å, respectively. The analogous error bars for the vibrational fundamental wavenumber ν and the effective ground-state rotational constant B0 are estimated to be about ±0.1 and ±0.0006 cm–1, respectively. Figure 1 illustrates the basis set convergence of the calculated vibrational term values Gv. Differences between the calculated and experimental values ΔGv are plotted for all of the observed3 bound vibrational levels of 24MgH, v = 1–11. For the highest-energy level, the calculated term values overestimate the experimental counterparts by as much as 45.4 through 72.5 cm–1 for the aug-cc-pCV5Z through aug-cc-pCV8Z(i) basis sets, respectively. Note that, somewhat surprisingly, the molecular parameters of MgH obtained with the largest basis set are in worst agreement with the experimental data. This suggests that some other effects should be considered, namely, enlargement of the basis set beyond the i polarization functions and of electron correlation beyond the MR-ACPF level of approximation, as well as the scalar relativistic, adiabatic, and nonadiabatic effects.

Table 1. Molecular Parameters for the X2Σ+ State of 24MgH Determined at the MR-ACPF/aug-cc-pCVnZ Level of Theory.

| n = 5 | n = 6 | n = 7 | n = 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rea (Å) | 1.73034 | 1.72977 | 1.72957 | 1.72948 |

| E + 200b (hartree) | –0.518218 | –0.522530 | –0.524054 | –0.524613 |

| Dec (cm–1) | 11,149 | 11,173 | 11,180 | 11,182 |

| νd(cm–1) | 1432.96 | 1433.44 | 1433.87 | 1433.99 |

| B0e (cm–1) | 5.73589 | 5.73942 | 5.74072 | 5.74128 |

The equilibrium internuclear distance.

The total energy at a minimum.

The binding energy.

The vibrational fundamental wavenumber.

The ground-state effective rotational constant.

Figure 1.

Differences between the calculated [MR-ACPF/aug-cc-pCVnZ (n = 5–8)] and experimental3 vibrational term values ΔGv for the X2Σ+ state of 24MgH.

Effects of the k and l polarization functions were investigated using the partially spin-restricted coupled-cluster method RCCSD(T),29 as implemented in the OpenMolcas package of ab initio programs.30 In the vicinity of the equilibrium configuration of MgH, enlargement of the truncated basis set aug-cc-pCV8Z(i) to the complete basis set aug-cc-pCV8Z decreases the total energy by only 1.2 mEh. Changes in the molecular parameters of MgH listed in Table 1 were found to be also very small, being just about 0.000002 Å for re, 1.4 cm–1 for De, −0.01 cm–1 for ν, and 0.00003 cm–1 for B0.

Changes due to electron correlation beyond the MR-ACPF level of approximation were estimated in the full-configuration-interaction (FCI) calculations. The FCI calculations accounting for the correlation effects of all 11 outer-core and valence electrons of MgH appeared to be not feasible. Even the modest basis set of double-ζ quality was applied, the FCI wave function consisted of nearly 2 × 1012 determinants for each symmetry class. Thus, only three valence electrons of MgH were considered. In calculations with the aug-cc-pCVQZ basis set, differences between the FCI and MR-ACPF total energies of MgH were found to be smaller than 1 μEh for all of the internuclear distances under consideration. The valence CASSCF/MR-ACPF treatment based on the extended active space described above is thus close to the valence FCI treatment. However, note that in these correlation treatments, the core–valence and core–core correlation effects of eight outer-core electrons of magnesium were neglected. Changes in the total energy of MgH beyond the MR-ACPF level of approximation were considered negligible.

The scalar relativistic effects were investigated using the exact-2-component (X2C) approach.31 The scalar relativistic correction was determined as a difference in the total energy of MgH calculated at the MR-ACPF/aug-cc-pCV5Z(uncontracted) level of theory using either the X2C or nonrelativistic Hamiltonian. The extended active space was used, and all 11 outer-core and valence electrons of MgH were considered in the dynamical correlation treatment. In the vicinity of the equilibrium configuration of MgH, the scalar relativistic correction was determined to be −307.6 mEh.

The adiabatic effects were investigated for the main isotopologue 24MgH as well as for the minor isotopologues including 25Mg, 26Mg, D, and T. The diagonal Born–Oppenheimer correction (DBOC)32,33 was determined using the restricted-active-space configuration interaction (RAS CI)34 method with the aug-cc-pCVTZ basis set. The extended active space described above was taken as the active space (RAS2) of the RAS CI wave function of MgH. The calculations were performed using the PSI3 package of ab initio programs.35

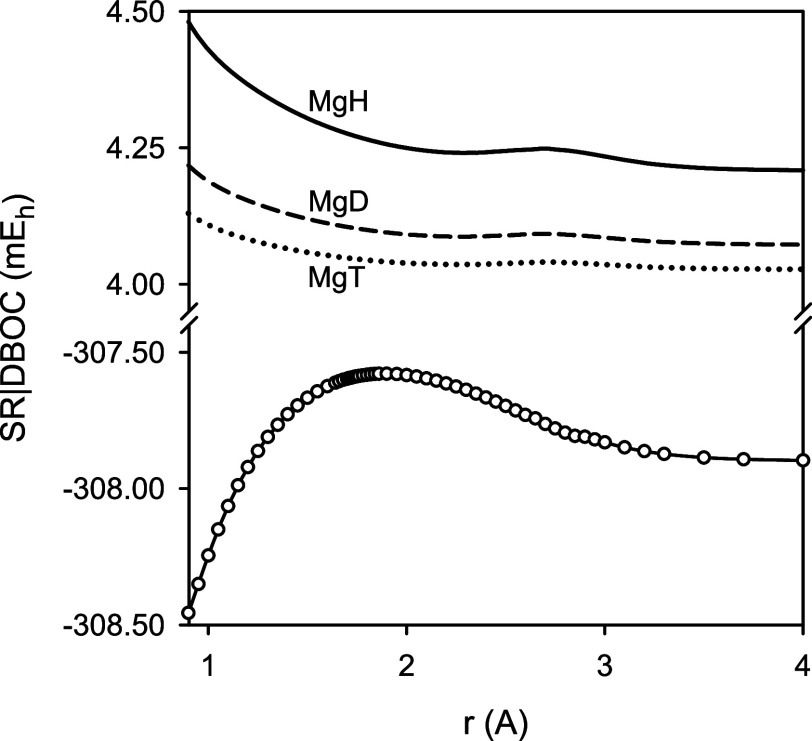

Figure 2 illustrates contributions to the total energy of MgH due to the scalar relativistic and adiabatic effects as functions of the internuclear distance r. The presented functions DBOC(r) were calculated for the 24MgH, 24MgD, and 24MgT isotopologues. In the vicinity of the equilibrium configuration of these isotopologues, the corresponding DBOC values were predicted to be 4.27, 4.10, and 4.05 mEh, respectively.

Figure 2.

Predicted scalar relativistic (SR, the lower part) and diagonal Born–Oppenheimer corrections (DBOC, the upper part) to the total energy for the X2Σ+ state of MgH as a function of the internuclear distance r. Note that the upper-part energy scale is stretched by a factor of 2.

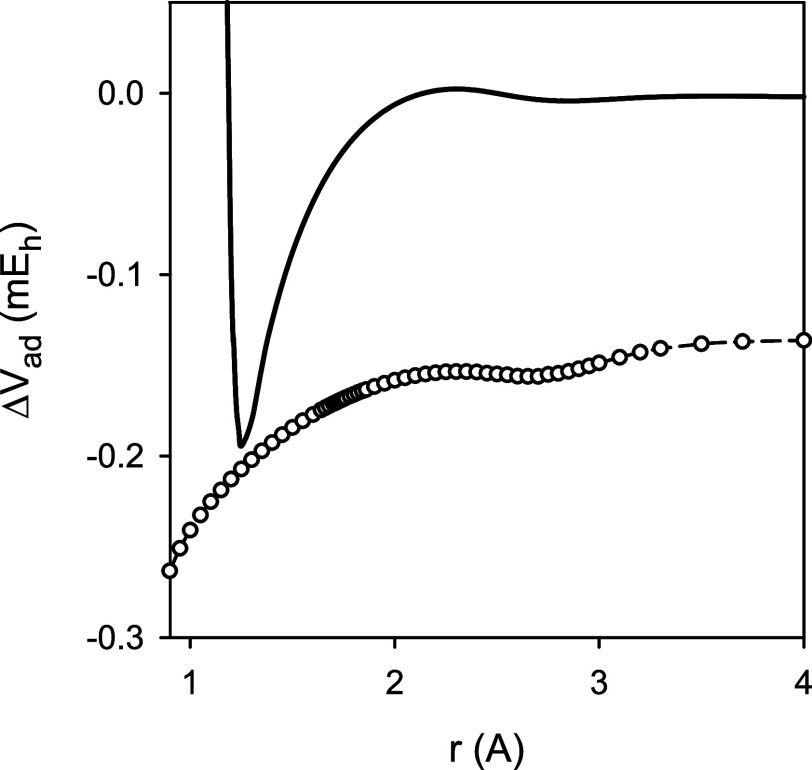

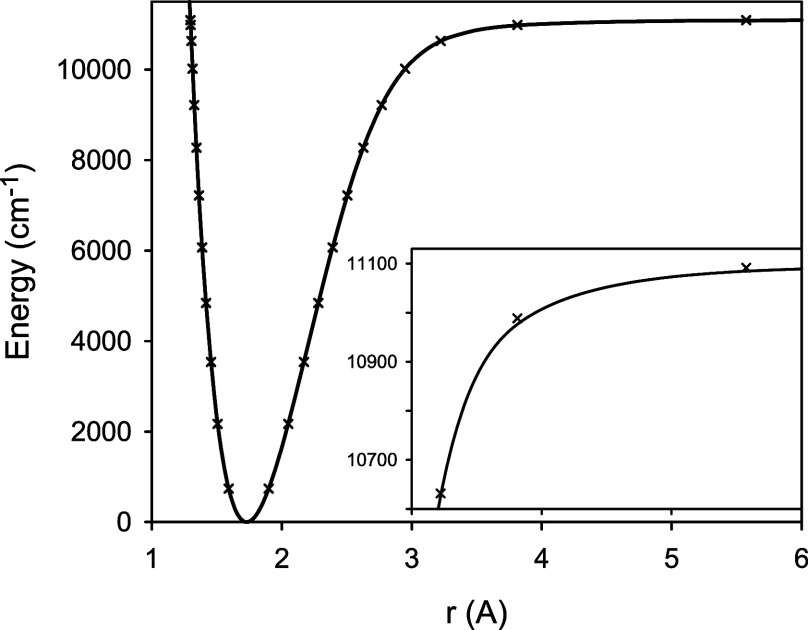

The energy corrections due to enlargement of the basis set and to the scalar relativistic and adiabatic effects were calculated at the same set of points as the MR-ACPF/aug-cc-pCV8Z(i) potential energy function discussed above. The molecular parameters for 24MgH in its X2Σ+ state obtained with the corrected potential energy functions are given in Table 2. These are compared with the corresponding values derived by Henderson et al.4 in the analysis of high-resolution vibration–rotation spectra of 24MgH and its minor isotopologues. The predicted adiabatic equilibrium internuclear distance re underestimates its experimental counterpart by 0.0004 Å. Accordingly, the predicted effective ground-state rotational constant B0 overestimates its experimental counterpart by 0.0057 cm–1. Somewhat surprisingly, this difference is another magnitude larger than the estimated uncertainty of the theoretical B0 value. For the 24MgH, 24MgD, and 24MgT isotopologues, the adiabatic equilibrium internuclear distance re is predicted to be longer than the Born–Oppenheimer counterpart by 0.00038, 0.00020, and 0.00014 Å, respectively. In the analysis of the experimental spectra of various MgH isotopologues,4 only a difference between the adiabatic potential energy functions ΔVad of 24MgD and 24MgH could be determined. Figure 3 illustrates the experimental difference ΔVad as a function of the internuclear distance r, compared with a difference of the corresponding diagonal Born–Oppenheimer corrections predicted in this work. Concerning the equilibrium internuclear distance re, the experimental difference for 24MgD and 24MgH was derived4 to be −0.00024 Å, as compared to the theoretical value of −0.00018 Å. For the 24MgH, 24MgD, and 24MgT isotopologues, the adiabatic corrections to the Born–Oppenheimer binding energy De were predicted to be −14.1, −6.8, and −4.3 cm–1, respectively. From the experimental data,4 only the isotopic shifts in De could be derived. Relative to the main isotopologue 24MgH, the D-, T-, 25Mg-, and 26Mg-isotopic shifts in De were obtained4 to be 7.59, 10.11, −0.05, and −0.10 cm–1, respectively. The corresponding theoretical adiabatic values were predicted in this work to be 7.35, 9.80, −0.03, and −0.05 cm–1, respectively. The predicted adiabatic vibrational fundamental wavenumber ν and the binding energy De of 24MgH differ from their experimental counterparts by 0.2 and 3 cm–1, respectively. The predicted Born–Oppenheimer and adiabatic potential energy functions of 24MgH are given in Table S1 of the Supporting Information. The latter function is also shown in Figure 4 along with the superimposed experimental3 classical turning points for the vibrational levels v = 0–11. All of the experimental classical turning points coincide (in the scale of the figure) with the theoretical ones. Differences between the calculated and experimental vibrational term values ΔGv of 24MgH are depicted in Figure 5. A comparison with Figure 1 shows that upon accounting for the scalar relativistic and adiabatic effects, these differences decrease by the order of magnitude. The calculated adiabatic vibrational term values Gv and the effective rotational constants Bv and quartic centrifugal distortion constants Dv of all bound vibrational states for the X2Σ+ state of 24MgH are given in Table 3. The predicted values are compared with the empirical band constants reported by Shayesteh et al.3 As shown in Table 3 and Figure 5, differences between the predicted and experimental spectroscopic constants of 24MgH change regularly with the increasing quantum number v up to v = 9. The analogous differences for v = 10 and 11 clearly do not follow that pattern.

Table 2. Molecular Parametersa for the X2Σ+ State of 24MgH Determined using Various Potential Energy Functions and Derived from the Experimental Data.

| CVb | CV + Rc | CV + R + Dc | Exp.d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| re (Å) | 1.72948 | 1.72890 | 1.72928 | 1.729685 |

| E + 200 (hartree) | –0.525839 | –0.833431 | –0.829159 | |

| De (cm–1) | 11,183 | 11,115 | 11,101 | 11,104.3 |

| ν (cm–1) | 1433.98 | 1432.33 | 1431.76 | 1431.978 |

| B0 (cm–1) | 5.74130 | 5.74476 | 5.74223 | 5.736507 |

The potential energy function was calculated at the MR-ACPF/aug-cc-pCV8Z level of theory, including the correction for enlargement of the basis set (see the text).

Including additional corrections for the scalar relativistic (R) and adiabatic (D) effects.

Derived from the experimental data in ref (4).

Figure 3.

Experimental4 adiabatic correction function ΔVad(r) for 24MgD vs 24MgH (solid line) in comparison to a difference of the corresponding diagonal Born–Oppenheimer corrections (circles) predicted in this work.

Figure 4.

Predicted adiabatic potential energy function for the X2Σ+ state of 24MgH in comparison to the experimental3 classical turning points for the vibrational levels v = 0–11 (x marks). The inset shows the region of the outer turning points for the vibrational levels v = 9–11.

Figure 5.

Differences between the calculated (see Table 2: CV circles, CV + R squares, and CV + R + D diamonds) and experimental3 vibrational term values ΔGv for the X2Σ+ state of 24MgH. The plot “CV” extends far beyond the figure scale; compare Figure 1. The values marked by stars were predicted taking into account the nonadiabatic effects.

Table 3. Adiabatic Vibrational Term Values (Gv) and the Effective Rotational (Bv) and Quartic Centrifugal Distortion (Dv) Constants (All in Inverse Centimeters) for the X2Σ+ State of 24MgH.

|

Gv |

Bv |

Dv × 104 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| v | Exp.a | Calc.b | Δc | Exp. | Calc. | Δ | Exp. | Calc. | Δ |

| 0 | 0.000 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 5.73651 | 5.7422 | 0.0057 | 3.5431 | 3.560 | 0.017 |

| 1 | 1431.978 | 1431.76 | –0.22 | 5.55529 | 5.5608 | 0.0056 | 3.5569 | 3.573 | 0.016 |

| 2 | 2800.678 | 2800.37 | –0.31 | 5.36751 | 5.3730 | 0.0055 | 3.5928 | 3.616 | 0.023 |

| 3 | 4102.330 | 4102.12 | –0.21 | 5.16973 | 5.1753 | 0.0056 | 3.6753 | 3.704 | 0.029 |

| 4 | 5331.389 | 5331.51 | 0.12 | 4.95654 | 4.9623 | 0.0057 | 3.8273 | 3.868 | 0.041 |

| 5 | 6479.656 | 6480.36 | 0.70 | 4.71964 | 4.7254 | 0.0058 | 4.0954 | 4.161 | 0.066 |

| 6 | 7534.814 | 7536.34 | 1.52 | 4.44431 | 4.4504 | 0.0061 | 4.5742 | 4.694 | 0.120 |

| 7 | 8478.000 | 8480.34 | 2.34 | 4.10720 | 4.1116 | 0.0044 | 5.8007 | 5.710 | –0.091 |

| 8 | 9279.653 | 9282.06 | 2.40 | 3.65877 | 3.6609 | 0.0022 | 7.3349 | 7.800 | 0.465 |

| 9 | 9892.724 | 9893.30 | 0.58 | 3.00781 | 2.9990 | –0.0088 | 13.052 | 12.92 | –0.13 |

| 10 | 10,249.407 | 10,244.46 | –4.95 | 1.96873 | 1.9466 | –0.0221 | 27.642 | 26.55 | –1.10 |

| 11 | 10,352.250 | 10,347.82 | –4.43 | 0.88390 | 0.9103 | 0.0264 | 45.349 | 42.02 | –3.33 |

The empirical band constants from ref (3).

The values calculated using the adiabatic potential energy function; the zero-point energy is 738.96 cm–1.

A difference between the calculated and experimental values.

The effects beyond the adiabatic approximation36−39 were investigated by applying second-order perturbational corrections to the vibrational and rotational terms of the effective vibration–rotation Hamiltonian of a diatomic molecule. The reduced nuclear mass μ in the vibrational term was replaced by the effective vibrational reduced mass μv defined as μv = μ/(1 + β) whereas that in the rotational term was replaced by the effective rotational reduced mass μr defined as μr = μ/(1 + α). The parameters β and α as a function of the internuclear distance r are given as37,40

| 1 |

and

| 2 |

ΨX and Ψn are the Born–Oppenheimer electronic

wave functions of the ground and excited states, respectively, calculated

at various r. EX and En are the

corresponding electronic total energies.  and

and  are the total angular momentum operators

(for the Mg and H nuclei located at the z axis).

The parameters β and α are related to the electronic contributions

to the vibrational and rotational g-factors: gelv and gelr, respectively. These relations are β = (me/mp)gelv and α =

(me/mp)gelr, where me/mp is the electron–proton mass ratio. The vibrational and rotational g-factors for the main isotopologue 24MgH were

calculated at various internuclear distances using the CASSCF method

with the aug-cc-pV5Z basis set and the extended active space consisting

of 14 molecular orbitals (described above). For general theoretical

details of such calculations, the reader is referred to refs (40–42). The calculations were performed using the DALTON

package of ab initio programs.43

are the total angular momentum operators

(for the Mg and H nuclei located at the z axis).

The parameters β and α are related to the electronic contributions

to the vibrational and rotational g-factors: gelv and gelr, respectively. These relations are β = (me/mp)gelv and α =

(me/mp)gelr, where me/mp is the electron–proton mass ratio. The vibrational and rotational g-factors for the main isotopologue 24MgH were

calculated at various internuclear distances using the CASSCF method

with the aug-cc-pV5Z basis set and the extended active space consisting

of 14 molecular orbitals (described above). For general theoretical

details of such calculations, the reader is referred to refs (40–42). The calculations were performed using the DALTON

package of ab initio programs.43

In the vicinity of the equilibrium configuration of 24MgH, the nonadiabatic parameters β and α were calculated

to be about −0.67 × 10–3 and −1.40

× 10–3, respectively. Changes in the parameters

β and α with the internuclear distance r are illustrated in Figure 6. The dependence of the parameter α on r is close to 1/r2, as might be expected

from eq 2. This indirectly

implies that the sum over excited electronic states, including matrix

elements of the operators  and

and  and excitation energies, is nearly constant

over a wide range about the ground-state equilibrium configuration

of MgH. On a similar basis, see eq 1, the parameter β might be expected to vary only

insignificantly with r. Somewhat surprisingly, this

was found not to be the case for the ground electronic state of MgH.

As shown in Figure 6, the parameter β (its absolute value) increases substantially

with the increasing internuclear distance, reaching an extremum at r ≈ 2.7 Å. Then, the parameter β decreases

uniformly, reaching asymptotically the value of −(me/mp)gnu. The term gnu is the (constant)

nuclear contribution to the vibrational and rotational g-factors. Therefore, it was interesting to analyze individual second-order

perturbational contributions to the parameter β. The transition

matrix elements between the ground and excited electronic states of

MgH were determined using the finite-difference three-point algorithm

as implemented in the MOLPRO package of ab initio programs.23,44 The CASSCF/MRCI wave functions and energies for eight lowest doublet

states of Σ+ symmetry were calculated using the aug-cc-pV5Z

basis set and the extended active space described above. In the vicinity

of the equilibrium configuration of MgH, the largest contributions

to the parameter β arise from the first-to-third and fifth excited 2Σ+ electronic states. Contributions from

the other excited 2Σ+ electronic states

are by at least the order of magnitude smaller. However, at internuclear

distances of about 2.7 Å, the contribution from the first excited

state, B′2Σ+,

predominates; it amounts to 98% of the parameter β value. Following eq 1, this contribution arises

from the perturbational term P = M2/(EX – EB), where M = |⟨ΨX| – iℏ∂/∂r|ΨB⟩| is calculated

with the electronic wave functions Ψ of the X2Σ+ and B′2Σ+ states and EX and EB are the corresponding electronic total energies. Figure 7 illustrates the perturbational

term P and its components, M and D = EX – EB, as a function of the internuclear

distance r. The difference of the electronic total

energies D is fairly constant along the distance

range shown. The shape of the perturbational term P as a function of r is thus determined by the square

of the transition matrix element M. Consequently,

a comparison of Figures 6 and 7 indicates that the shape of the nonadiabatic

parameter β as a function of r is largely determined

by the interaction between the X2Σ+ and B′2Σ+ states of MgH. Note that the location of an extremum of β

as a function of r is fairly close to a minimum of

the potential energy function for the B′2Σ+ state of MgH, being derived from the emission

spectra of MgH to occur at r = 2.5940 Å.45

and excitation energies, is nearly constant

over a wide range about the ground-state equilibrium configuration

of MgH. On a similar basis, see eq 1, the parameter β might be expected to vary only

insignificantly with r. Somewhat surprisingly, this

was found not to be the case for the ground electronic state of MgH.

As shown in Figure 6, the parameter β (its absolute value) increases substantially

with the increasing internuclear distance, reaching an extremum at r ≈ 2.7 Å. Then, the parameter β decreases

uniformly, reaching asymptotically the value of −(me/mp)gnu. The term gnu is the (constant)

nuclear contribution to the vibrational and rotational g-factors. Therefore, it was interesting to analyze individual second-order

perturbational contributions to the parameter β. The transition

matrix elements between the ground and excited electronic states of

MgH were determined using the finite-difference three-point algorithm

as implemented in the MOLPRO package of ab initio programs.23,44 The CASSCF/MRCI wave functions and energies for eight lowest doublet

states of Σ+ symmetry were calculated using the aug-cc-pV5Z

basis set and the extended active space described above. In the vicinity

of the equilibrium configuration of MgH, the largest contributions

to the parameter β arise from the first-to-third and fifth excited 2Σ+ electronic states. Contributions from

the other excited 2Σ+ electronic states

are by at least the order of magnitude smaller. However, at internuclear

distances of about 2.7 Å, the contribution from the first excited

state, B′2Σ+,

predominates; it amounts to 98% of the parameter β value. Following eq 1, this contribution arises

from the perturbational term P = M2/(EX – EB), where M = |⟨ΨX| – iℏ∂/∂r|ΨB⟩| is calculated

with the electronic wave functions Ψ of the X2Σ+ and B′2Σ+ states and EX and EB are the corresponding electronic total energies. Figure 7 illustrates the perturbational

term P and its components, M and D = EX – EB, as a function of the internuclear

distance r. The difference of the electronic total

energies D is fairly constant along the distance

range shown. The shape of the perturbational term P as a function of r is thus determined by the square

of the transition matrix element M. Consequently,

a comparison of Figures 6 and 7 indicates that the shape of the nonadiabatic

parameter β as a function of r is largely determined

by the interaction between the X2Σ+ and B′2Σ+ states of MgH. Note that the location of an extremum of β

as a function of r is fairly close to a minimum of

the potential energy function for the B′2Σ+ state of MgH, being derived from the emission

spectra of MgH to occur at r = 2.5940 Å.45

Figure 6.

Nonadiabatic parameters α (circles) and β (diamonds) for the X2Σ+ state of 24MgH as a function of the internuclear distance r.

Figure 7.

Perturbational term P (solid line) and its components, M and D (dotted and dashed lines, respectively; see the text), arising from the nonadiabatic interaction between the X2Σ+ and B′2Σ+ states of 24MgH, as a function of the internuclear distance r.

Changes in the vibrational term values Gv of 24MgH upon accounting for the nonadiabatic parameter β are given in Table 4, the column headed “VRM”. The changes ΔGnav are calculated relative to the adiabatic vibrational term values listed in Table 3. These changes were also estimated by investigating the nonadiabatic interaction only between the X2Σ+ and B′2Σ+ states of MgH. In this case, the sum over excited electronic states defining the parameter β was truncated to the first term, i.e., the perturbational term P discussed above. Changes in the vibrational term values predicted in this way are listed in the column headed “TSO”. Last, the vibrational term values Gv of 24MgH were determined using the reduced mass μ calculated with the atomic masses of magnesium and hydrogen, μat. In a spirit of the adiabatic approximation, the use of atomic (instead of nuclear) masses means that all electrons pertinent to a given atom follow very closely its nucleus during vibration. In terms of the nonadiabatic interaction, this corresponds to the parameter β being kept fixed at −(me/mp)gnu. Changes in the vibrational term values predicted in this way are given in the column headed “ARM”. The changes ΔGnav were found to be quite sizable, decreasing the vibrational term values of 24MgH by as much as 3 cm–1. As expected, the changes VRM and TSO look very much alike, concerning both the magnitude and the dependence on the vibrational quantum number v. Note that this dependence reflects the shape of the nonadiabatic parameter β as a function of the internuclear distance r; see Figures 6 and 7. As shown in Figure 4, the outer classical turning points for the highly excited vibrational levels v = 7–11 of 24MgH lie beyond the location of an extremum of β. All the changes ΔGnav were predicted to be similar for low-lying vibrational levels. However, for the highly excited vibrational levels, the changes VRM and TSO were found to be larger (by a factor of 2) than the changes ARM.

Table 4. Changes in the Vibrational Term Values (ΔGnav, in Inverse Centimeters) for the X2Σ+ State of 24MgH Calculated Taking into Account the Nonadiabatic Effects.

| v | VRMa | TSOb | ARMc |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | –0.25 | –0.22 | –0.20 |

| 1 | –0.72 | –0.63 | –0.56 |

| 2 | –1.19 | –1.03 | –0.89 |

| 3 | –1.64 | –1.43 | –1.18 |

| 4 | –2.10 | –1.84 | –1.43 |

| 5 | –2.56 | –2.26 | –1.62 |

| 6 | –2.98 | –2.66 | –1.74 |

| 7 | –3.30 | –2.97 | –1.76 |

| 8 | –3.37 | –3.06 | –1.62 |

| 9 | –2.83 | –2.60 | –1.25 |

| 10 | –1.32 | –1.23 | –0.57 |

| 11 | –0.29 | –0.27 | –0.13 |

Predicted using the effective vibrational reduced mass μv = μ/(1 + β).

Predicted using the parameter β modified to account only for the interaction between two states X2Σ+ and B′2Σ+; see the text.

Predicted using the atomic reduced mass μat.

In analyses of the infrared spectra of MgH,2−4 the effective Hamiltonian of a diatomic molecule was applied. Following the theoretical work of Watson,38,46 the nonadiabatic terms associated with the kinetic energy operator were incorporated into the rotational part of the potential energy operator as the effective centrifugal-potential correction function [1 + g(r)].47 In general, the nonadiabatic correction g(r) can be expressed in terms of the nonadiabatic parameters β(r) and α(r) discussed above. The reduced mass μ was taken as the (constant) atomic reduced mass μat and, in the zeroth-order approximation, the correction g(r) was identical to α(r). In the first-order approximation, the correction g(r) became [α(r) – β(r)]; see eq 7 of ref (47). The shape of the correction function g(r) derived by Henderson et al.4 from the infrared spectra of 24MgH is shown in Figure 8 and compared with the functions α(r) and [α(r) – β(r)] predicted in this work.

Figure 8.

Experimental4 radial correction function g(r) for the nonadiabatic effects of 24MgH (solid line), in comparison to the predicted nonadiabatic functions α(r) (circles) and [α(r) – β(r)] (squares); see the text.

The vibrational term values Gv and the effective rotational constants Bv and quartic centrifugal distortion constants Dv calculated for 24MgH taking into account the nonadiabatic effects are given in Table 5. Except for the v = 10 and 11 vibrational levels, the experimental vibrational term values of 24MgH are reproduced to within 1.4 cm–1, whereas the effective rotational constants are reproduced to within 0.0029 cm–1 (the root-mean-square deviation). The corresponding accuracy limits for these spectroscopic constants obtained within the adiabatic approximation, see Table 3, are 1.3 and 0.0057 cm–1, respectively. Differences between the calculated and experimental vibrational term values ΔGv of 24MgH are illustrated in Figure 5. The remaining errors in the predicted spectroscopic constants of 24MgH are likely due to approximations inherent to the MR-ACPF method.

Table 5. Vibrational Term Values (Gv) and the Effective Rotational (Bv) and Quartic Centrifugal Distortion (Dv) Constants (All in Inverse Centimeters) for the X2Σ+ State of 24MgH.

|

Gv |

Bv |

Dv × 104 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| v | Exp.a | Calc.b | Δc | Exp. | Calc. | Δ | Exp. | Calc. | Δ |

| 0 | 0.000 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 5.73651 | 5.7341 | –0.0024 | 3.5431 | 3.543 | –0.001 |

| 1 | 1431.978 | 1431.28 | –0.69 | 5.55529 | 5.5530 | –0.0023 | 3.5569 | 3.555 | –0.002 |

| 2 | 2800.678 | 2799.43 | –1.25 | 5.36751 | 5.3655 | –0.0020 | 3.5928 | 3.598 | 0.005 |

| 3 | 4102.330 | 4100.72 | –1.61 | 5.16973 | 5.1681 | –0.0016 | 3.6753 | 3.686 | 0.011 |

| 4 | 5331.389 | 5329.65 | –1.74 | 4.95654 | 4.9554 | –0.0011 | 3.8273 | 3.849 | 0.021 |

| 5 | 6479.656 | 6478.05 | –1.61 | 4.71964 | 4.7190 | –0.0006 | 4.0954 | 4.141 | 0.045 |

| 6 | 7534.814 | 7533.60 | –1.21 | 4.44431 | 4.4446 | 0.0003 | 4.5742 | 4.670 | 0.095 |

| 7 | 8478.000 | 8477.28 | –0.72 | 4.10720 | 4.1068 | –0.0004 | 5.8007 | 5.677 | –0.124 |

| 8 | 9279.653 | 9278.93 | –0.72 | 3.65877 | 3.6579 | –0.0009 | 7.3349 | 7.748 | 0.413 |

| 9 | 9892.724 | 9890.72 | –2.01 | 3.00781 | 2.9997 | –0.0081 | 13.052 | 12.81 | –0.24 |

| 10 | 10,249.407 | 10,243.39 | –6.02 | 1.96873 | 1.9529 | –0.0158 | 27.644 | 26.36 | –1.28 |

| 11 | 10,352.250 | 10,347.78 | –4.47 | 0.88390 | 0.9157 | 0.0318 | 45.349 | 41.68 | –3.67 |

The empirical band constants from ref (3).

The values predicted taking into account the nonadiabatic effects; the zero-point energy is 738.72 cm–1.

A difference between the calculated and experimental values.

The dissociation energy D0 of the main isotopologue 24MgH in its X2Σ+ state is determined in this work to be 10,362 cm–1, compared with the experimental value4 of 10,365.14 cm–1. The vibrationally averaged internuclear distance ⟨r⟩ is calculated for the ground vibrational state to be 1.7530 Å. The vibrationally averaged rotational and vibrational g-factors are predicted to be ⟨gr⟩ = −1.578 and ⟨gv⟩ = −0.248, respectively.

To summarize, descriptors of the molecular dynamics and structure—the vibrational fundamental wavenumbers ν and the effective ground-state rotational constants B0—for the X2Σ+ state of the most-abundant MgH isotopologues are given in Table 6. The values predicted in this study using the adiabatic and nonadiabatic approaches are compared with those obtained by Henderson et al.4 from the experimentally adjusted Morse/Long-Range potential energy function of MgH and the Born–Oppenheimer breakdown functions.

Table 6. Vibrational Fundamental Wavenumbers (ν) and the Effective Ground-State Rotational Constants (B0, All in Inverse Centimeters) for the X2Σ+ State of Various MgH Isotopologues.

| ν |

B0 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| isotopologue | Exp.a | Calc.b | Δc | Exp. | Calc. | Δ |

| Adiabatic | ||||||

| 24MgH | 1431.978 | 1431.76 | –0.22 | 5.73651 | 5.7422 | 0.0057 |

| 24MgD | 1045.844 | 1045.50 | –0.34 | 3.00095 | 3.0019 | 0.0010 |

| 24MgT | 875.481 | 875.15 | –0.33 | 2.08558 | 2.0858 | 0.0002 |

| 25MgH | 1430.871 | 1430.65 | –0.22 | 5.72732 | 5.7330 | 0.0057 |

| 26MgH | 1429.851 | 1429.63 | –0.22 | 5.71888 | 5.7246 | 0.0057 |

| Nonadiabatic | ||||||

| 24MgH | 1431.978 | 1431.28 | –0.69 | 5.73651 | 5.7341 | –0.0024 |

| 24MgD | 1045.844 | 1045.33 | –0.51 | 3.00095 | 2.9997 | –0.0012 |

| 24MgT | 875.481 | 875.05 | –0.43 | 2.08558 | 2.0847 | –0.0008 |

| 25MgH | 1430.871 | 1430.18 | –0.69 | 5.72732 | 5.7249 | –0.0024 |

| 26MgH | 1429.851 | 1429.16 | –0.69 | 5.71888 | 5.7165 | –0.0024 |

The experimental spectroscopic constants from ref (4).

The values predicted using the adiabatic and nonadiabatic approaches.

A difference between the calculated and experimental values.

The electric dipole moment of MgH in its X2Σ+ state was determined as an expectation value for the electronic wave function calculated at the MR-ACPF/aug-cc-pCV8Z(i) level of theory, with the extended active space described above. The predicted dipole moment as a function of the internuclear distance is given in Table S2 of the Supporting Information The vibrationally averaged electric dipole moment of 24MgH was predicted for the ground vibrational state to be 1.386 D. The natural-bond-orbital atomic net charges in the X2Σ+ state of MgH were determined at the MR-ACPF/aug-cc-pCVQZ level of theory to be 0.73e and −0.73e on the magnesium and hydrogen atoms, respectively. To our knowledge, the electric dipole moment of MgH was not determined experimentally so far.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the accurate potential energy function of magnesium monhydride in the ground electronic state X2Σ+ was determined in the state-of-the-art ab initio calculations. The vibration–rotation energy levels of the main isotopologue 24MgH were predicted to near the “spectroscopic” accuracy. The scalar relativistic, adiabatic, and nonadiabatic effects were taken into account. For the vibrational energy levels up to v = 9, the remaining differences between the experimentally observed and theoretically predicted spectroscopic constants of 24MgH are likely due to approximations inherent to the MR-ACPF method, applied in this work to determine the electronic wave function and properties. The analogous differences for v = 10 and 11 clearly do not follow that accuracy pattern. It is an open question whether this discrepancy results also from the theoretical method applied or from a misassignment of the experimental data. The nonadiabatic interaction between the X2Σ+ and B′2Σ+ states of MgH should be explicitly accounted for in a future analysis of the high-resolution vibration–rotation spectra.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jpca.4c01757.

The predicted Born–Oppenheimer (CV + R) and adiabatic (CV + R + D) potential energy functions for 24MgH in its X2Σ+ state and electric dipole moment of MgH as a function of the internuclear distance (PDF)

The author declares no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Owens A.; Dooley S.; McLaughlin L.; Tan B.; Zhang G.; Yurchenko S. N.; Tennyson J. ExoMol line lists – XLV. Rovibronic molecular line lists of calcium monohydride (CaH) and magnesium monohydride (MgH). Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2022, 511, 5448–5461. 10.1093/mnras/stac371. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shayesteh A.; Appadoo D. R. T.; Gordon I.; Le Roy R. J.; Bernath P. F. Fourier transform infrared emission spectra of MgH and MgD. J. Chem. Phys. 2004, 120, 10002–10008. 10.1063/1.1724821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shayesteh A.; Henderson R. D. E.; Le Roy R. J.; Bernath P. F. Ground state potential energy curve and dissociation energy of MgH. J. Phys. Chem. A 2007, 111, 12495–12505. 10.1021/jp075704a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson R. D. E.; Shayesteh A.; Tao J.; Haugen C. C.; Bernath P. F.; Le Roy R. J. Accurate analytic potential and Born-Oppenheimer breakdown functions for MgH and MgD from a direct-potential-fit data analysis. J. Phys. Chem. A 2013, 117, 13373–13387. 10.1021/jp406680r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan A. C. H.; Davidson E. R. Theoretical study of the MgH molecule. J. Chem. Phys. 1970, 52, 4108–4121. 10.1063/1.1673619. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer W.; Rosmus P. PNO–CI and CEPA studies of electron correlation effects. III. Spectroscopic constants and dipole moment functions for the ground states of the first-row and second-row diatomic hydrides. J. Chem. Phys. 1975, 63, 2356–2375. 10.1063/1.431665. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sink M. L.; Bandrauk A. D.; Henneker W. H.; Lefebvre-Brion H.; Raseev G. Theoretical study of the low-lying electronic states of MgH. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1976, 39, 505–510. 10.1016/0009-2614(76)80316-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sink M. L.; Bandrauk A. D. A theoretical study of the B′2Σ+ – X2Σ+ band system in MgH and MgD. Can. J. Phys. 1979, 57, 1178–1184. 10.1139/p79-165. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saxon R. P.; Kirby K.; Liu B. Ab initio configuration interaction study of the low-lying electronic states of MgH. J. Chem. Phys. 1978, 69, 5301–5309. 10.1063/1.436556. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby K.; Saxon R. P.; Liu B. Oscillator strengths and photodissociation cross sections in the X → A and X → B′ band systems in MgH. Astrophys. J. 1979, 231, 637–644. 10.1086/157226. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bruna P. J.; Grein F. Hyperfine coupling constants, electron-spin g-factors and vertical spectra of the X2Σ+ radicals BeH, MgH, CaH and BZ+, AlZ+, GaZ+ (Z = H, Li, Na, K). A theoretical study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2003, 5, 3140–3153. 10.1039/B303698G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mestdagh J. M.; de Pujo P.; Soep B.; Spiegelman F. Ab-initio calculation of the ground and excited states of MgH using a pseudopotential approach. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2009, 471, 22–28. 10.1016/j.cplett.2009.01.078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guitou M.; Spielfiedel A.; Feautrier N. Accurate potential energy functions and non-adiabatic couplings in the Mg + H system. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2010, 488, 145–152. 10.1016/j.cplett.2010.02.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mostafanejad M.; Shayesteh A. Ab initio potential energy curves and transition dipole moments for the X2Σ+, A2Π and B′2Σ+ states of MgH. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2012, 551, 13–18. 10.1016/j.cplett.2012.08.056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D. L.; Tan B.; Xie A. D.; Yan B.; Ding D. J. Accurate calculation of the potential energy curve and spectroscopic parameters of X2Σ+ state of 12Mg1H. Chin. Phys. B 2015, 24, 043401. 10.1088/1674-1056/24/4/043401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyaya S. Electronic states and spectroscopic properties of MgH in absence and presence of spin–orbit coupling – a configuration interaction study. Mol. Phys. 2016, 114, 3026–3039. 10.1080/00268976.2016.1213911. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D.; Tan B.; Zeng X.; Wan H.; Xie A.; Yan B.; Ding D. Theoretical study on the spectroscopic parameters and transition properties of MgH radical including spin-orbit coupling. Chin. Phys. Lett. 2016, 33, 063102. 10.1088/0256-307X/33/6/063102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- González-Sánchez L.; Gómez-Carrasco S.; Santadaría A. M.; Gianturco F. A.; Wester R. Investigating the electronic properties and structural features of MgH and of MgH– anions. Phys. Rev. A 2017, 96, 042501. 10.1103/PhysRevA.96.042501. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y. Electronic and hyperfine structures of 24MgH with relevance to laser cooling. Phys. Rev. A 2020, 102, 042821. 10.1103/PhysRevA.102.042821. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gdanitz R. J.; Ahlrichs R. The averaged coupled-pair functional (ACPF): A size-extensive modification of MR CI(SD). Chem. Phys. Lett. 1988, 143, 413–420. 10.1016/0009-2614(88)87388-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gdanitz R. J. A new version of the multireference averaged coupled-pair functional. (MR-ACPF-2). Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2001, 85, 281–300. 10.1002/qua.10019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Werner H.-J.; Knowles P. J. An efficient internally contracted multiconfiguration–reference configuration interaction method. J. Chem. Phys. 1988, 89, 5803–5814. 10.1063/1.455556. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Werner H.-J.; Knowles P. J.; et al. MOLPRO, a package of ab initio programs, Version 2022.1, 2022. https://www.molpro.net (accessed April 1, 2022).

- Prascher B. P.; Woon D. E.; Peterson K. A.; Dunning T. H. Jr.; Wilson A. K. Gaussian basis sets for use in correlated molecular calculations. VII. Valence, core-valence, and scalar relativistic basis sets for Li, Be, Na, and Mg. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2011, 128, 69–82. 10.1007/s00214-010-0764-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koput J. Ab initio potential energy surface and vibration-rotation energy levels of magnesium monohydroxide revisited. J. Mol. Spectrosc. 2023, 395, 111805. 10.1016/j.jms.2023.111805. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dunning T. H. Jr. Gaussian basis sets for use in correlated molecular calculations. I. The atoms boron through neon and hydrogen. J. Chem. Phys. 1989, 90, 1007–1023. 10.1063/1.456153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard B. P.; Altarawy D.; Didier B.; Gibson T. D.; Windus T. L. New basis set exchange: An open, up-to-date resource for the molecular sciences community. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2019, 59, 4814–4820. 10.1021/acs.jcim.9b00725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooley J. W. An improved eigenvalue corrector formula for solving the Schrödinger equation for central fields. Math. Comput. 1961, 15, 363–374. 10.2307/2003025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watts J. D.; Gauss J.; Bartlett R. J. Coupled-cluster methods with noniterative triple excitations for restricted open-shell Hartree–Fock and other general single determinant reference functions. Energies and analytical gradients. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 8718–8733. 10.1063/1.464480. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aquilante F.; Autschbach J.; Baiardi A.; Battaglia S.; Borin V. A.; Chibotaru L. F.; Conti I.; De Vico L.; Delcey M.; Fdez Galván I.; et al. Modern quantum chemistry with [Open]Molcas. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 152, 214117. 10.1063/5.0004835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng D.; Reiher M. Exact decoupling of the relativistic Fock operator. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2012, 131, 1081. 10.1007/s00214-011-1081-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Handy N. C.; Lee A. M. The adiabatic approximation. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1996, 252, 425–430. 10.1016/0009-2614(96)00171-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Valeev E. F.; Sherrill C. D. The diagonal Born–Oppenheimer correction beyond the Hartree–Fock approximation. J. Chem. Phys. 2003, 118, 3921–3927. 10.1063/1.1540626. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen J.; Roos B. O.; Jo/rgensen P.; Jensen H. J. Aa. Determinant based configuration interaction algorithms for complete and restricted configuration interaction spaces. J. Chem. Phys. 1988, 89, 2185–2192. 10.1063/1.455063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford T. D.; Sherrill C. D.; Valeev E. F.; Fermann J. T.; King R. A.; Leininger M. L.; Brown S. T.; Janssen C. L.; Seidl E. T.; Kenny J. P.; et al. PSI3: An open-source ab initio electronic structure package. J. Comput. Chem. 2007, 28, 1610–1616. 10.1002/jcc.20573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman R. M.; Asgharian A. Theory of energy shifts associated with deviations from Born-Oppenheimer behavior in 1Σ-state diatomic molecules. J. Mol. Spectrosc. 1966, 19, 305–324. 10.1016/0022-2852(66)90254-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bunker P. R.; Moss R. E. The breakdown of the Born-Oppenheimer approximation: the effective vibration-rotation hamiltonian for a diatomic molecule. Mol. Phys. 1977, 33, 417–424. 10.1080/00268977700100351. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watson J. K. G. The isotope dependence of diatomic Dunham coefficients. J. Mol. Spectrosc. 1980, 80, 411–421. 10.1016/0022-2852(80)90152-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Herman R. M.; Ogilvie J. F. An effective Hamiltonian to treat adiabatic and nonadiabatic effects in the rotational and vibrational spectra of diatomic molecules. Adv. Chem. Phys. 1998, 103, 187–215. 10.1002/9780470141625.ch2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bak K. L.; Sauer S. P. A.; Oddershede J.; Ogilvie J. F. The vibrational g-factor of dihydrogen from theoretical calculation and analysis of vibration-rotational spectra. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7, 1747–1758. 10.1039/b500992h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauss J.; Ruud K.; Helgaker T. Perturbation-dependent atomic orbitals for the calculation of spin-rotation constants and rotational g tensors. J. Chem. Phys. 1996, 105, 2804–2812. 10.1063/1.472143. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kjær H.; Sauer S. P. A. On the relation between the non-adiabatic vibrational reduced mass and the electric dipole moment gradient of a diatomic molecule. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2009, 122, 137–143. 10.1007/s00214-008-0493-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aidas K.; Angeli C.; Bak K. L.; Bakken V.; Bast R.; Boman L.; Christiansen O.; Cimiraglia R.; Coriani S.; Dahle P.; et al. The Dalton quantum chemistry program system. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Comput. Mol. Sci. 2014, 4, 269–284. 10.1002/wcms.1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner H.-J.; Meyer W. MCSCF study of the avoided curve crossing of the two lowest 1Σ+ states of LiF. J. Chem. Phys. 1981, 74, 5802–5807. 10.1063/1.440893. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shayesteh A.; Bernath P. F. Rotational analysis and deperturbation of the A2Π → X2Σ+ and B′2Σ+ → X2Σ+ emission spectra of MgH. J. Chem. Phys. 2011, 135, 094308. 10.1063/1.3631341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson J. K. G. The inversion of diatomic Born–Oppenheimer-breakdown corrections. J. Mol. Spectrosc. 2004, 223, 39–50. 10.1016/j.jms.2003.09.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Le Roy R. J. Algebraic vs. numerical methods for analysing diatomic spectral data: a resolution of discrepancies. J. Mol. Spectrosc. 2004, 228, 92–104. 10.1016/j.jms.2004.03.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.