Abstract

Objectives

The aim of this study was to analyse retrospectively cats diagnosed with otitis media (OM) not due to nasopharyngeal polyp, and to review the clinical outcome with surgical and medical management.

Methods

Patient records were searched for cats diagnosed with OM. The diagnosis of OM was based on the presence of clinical signs, including neurological signs, respiratory signs and signs of otitis externa, and on the basis of evidence of thickened or irregular bullae walls, or the presence of fluid within the tympanic cavity in those that had diagnostic imaging. In those that did not have imaging, the diagnosis was made on the basis of the presence of fluid in the bulla or organisms cultured using myringotomy. These records were analysed retrospectively.

Results

Of 16 cats, one had a total ear canal ablation, five had ventral bulla osteotomy surgery and 11 were medically managed. Of the cats that were medically managed, using either topical products, systemic antimicrobials or a combination of both, eight had complete resolution of clinical signs.

Conclusions and relevance

This small cohort shows that some cats with OM can be successfully managed medically. Surgery is invasive and may not necessarily be required if appropriate medical management is undertaken. This is the first study of OM treatment in cats and provides the basis for further studies, which should aim to establish specific infectious causes of OM and how they can potentially be managed with medical therapies.

Introduction

Otitis media (OM) is defined as inflammation of the middle ear; the tympanic bulla (TB), up to and including the tympanic membrane (TM). It is less common than otitis externa (OE; inflammation of the external ear canal and pinna) and is less common in cats than in dogs. 1 Owing to the inaccessibility of the middle ear, OM can be challenging to diagnose and treat.

The feline middle ear consists of the TB; the bony shell, the tympanic cavity (TC) within, and the TM, which separates the middle ear from the external ear. Unlike in dogs, the TC is divided by a septum of bone, creating two compartments. The septum runs from mid-rostral to mid-lateral and has a small gap dorsally, allowing communication between the two compartments.2,3 In one review of OM, both compartments were affected more commonly (94%) than either the ventromedial or dorsolateral compartments alone (6%). 4 This structural difference to dogs may potentially make treatment more challenging in cats.

A variety of clinical signs are associated with OM in cats. OE and signs of upper airway obstruction (inspiratory noise, nasal discharge and dyspnoea) are common, along with signs of vestibular disease, including head tilt, circling, nystagmus and ataxia.5–7 Cats presenting with ipsilateral Horner’s syndrome are common, owing to damage to the palpebral branch of the facial nerve.8–10 Non-neurological, non-specific clinical signs may include head shaking, pruritus, pain and altered ear carriage. 7 Hearing deficits have also been reported in cats, owing to fluid in the TB or damage to the ossicles of the middle ear.5,11

There are several methods for diagnosing OM in cats. Because of their relatively short external ear canal, visualising the TM using otoscopy is relatively easy. Radiography, CT and MRI are commonly used, with CT and MRI being considered more sensitive. 12 Myringotomy can also be useful to collect diagnostic samples from the TB. 13 OM in cats most commonly presents as a result of a nasopharyngeal polyp (NPP) or pharyngeal or upper respiratory infection, which has extended up through the Eustachian tube. Less commonly, OM occurs as an extension of OE and it has also been suggested that a potential cause could be haematogenous spread.14,15

OM can either be managed medically or surgically. 16 In cats there is little, if any, information regarding medical management of OM not caused by an NPP. It has been suggested that there is an increased risk of ototoxicity in cats compared with dogs when using topical medications.5,17 The aim of this study was to analyse retrospectively cats diagnosed with OM not due to NPP, and look at the clinical outcome with surgical and medical management. The authors hoped to provide some recommendations for treating OM in cats not caused by an NPP.

Materials and methods

A search was performed in the practice management computer record system, using the keywords ‘CT bullae’ and ‘otitis media’, for cats. The results were then analysed to check that they fit the criteria; namely, cats of any age that had been referred with or diagnosed at the hospital with OM. Cats with only a presumed diagnosis were excluded, as were those that had CT scans of their bullae for reasons other than OM, such as traumatically avulsed ear canals. Any cat with mention of a middle ear polyp, NPP or ‘soft tissue-attenuating material’ in the bulla was also excluded.

The diagnosis of OM was based on the presence of clinical signs, including neurological signs, respiratory signs and signs of OE, and on the basis of evidence of thickened or irregular bullae walls, or the presence of fluid within the tympanic cavity, in those that had diagnostic imaging. In those that did not have imaging, the diagnosis was made on the basis of the presence of fluid in the bulla or organisms cultured using myringotomy.

The case files were then analysed and data entered onto an Excel spread sheet. Clinical signs at first presentation were noted, diagnostic techniques employed at the referring practice and the referral hospital, and treatments prescribed. Descriptive statistics were derived from these data using simple percentages. The referring veterinary practice was contacted by telephone to request an up-to-date clinical history for each cat, since its referral.

Results

Signalment

A total of 16 cats were diagnosed with OM between 2011 and 2016, of which 50% were unilaterally affected and 50% had bilateral OM.

The majority were under 10 years of age (5/16 [31.3%] under 5 and 7/16 [43.8%] aged 6–10 years; 12/16 were less than 10 years old). An equal number were male and female, most of which were neutered. The most commonly seen breed was the domestic shorthair (11/16 [68.8%]). Other breeds seen were domestic longhair, Siamese, Maine Coon, British Shorthair and Burmese.

Presentation

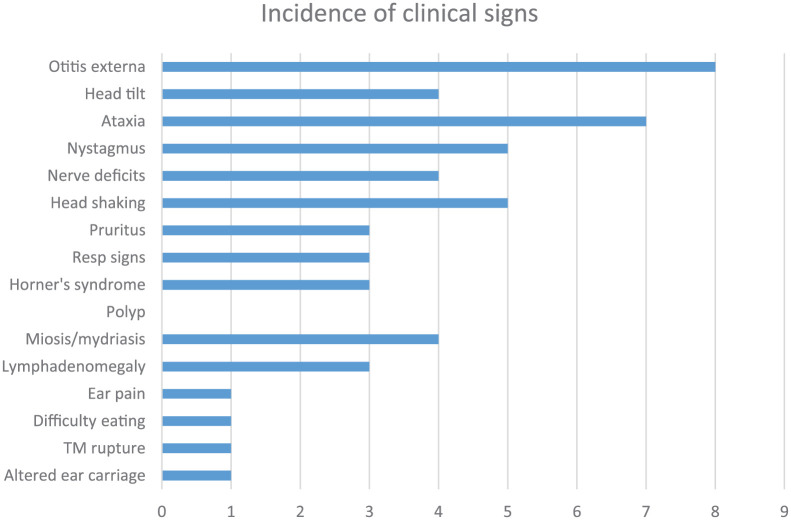

Half of the cats seen at the referral hospital had shown signs of OE either at the referring veterinary surgery or on presentation at the hospital, of which four had concurrent neurological signs. Figure 1 shows the clinical signs observed in the cats included in the study. A high proportion of cases (11/16 [68.8%]) presented with neurological signs, of which four had OE and neurological signs concurrently.

Figure 1.

Summary of the clinical signs recorded for 16 cats with a diagnosis of otitis media. Resp = respiratory; TM = tympanic membrane

Diagnostic investigations/tests at the referral hospital

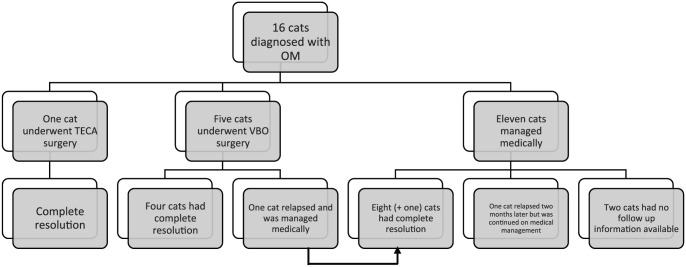

Eleven of 16 cats (68.8%) had a CT scan of their bullae, all of which had evidence of fluid in the bullae and four had bulla wall thickening. Four had MRI scans rather than CT (18.8%), of which 100% showed enhancing material in the bullae (see Figure 2). Two cats had evidence of otitis interna (one showing enhancement of inner-ear structures on postcontrast images; one having a large and distorted inner ear and enhancement of the semi-circular canals) and one of the two had concurrent meningitis.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram for 16 cats diagnosed with otitis media (OM) with a summary of the diagnostic methods

Of the four cats that showed evidence of bulla wall thickening, one was treated medically with systemic itraconazole and a topical preparation containing polymyxin B, prednisolone and miconazole (Surolan; Elanco), one underwent a ventral bulla osteotomy (VBO), one was recommended a VBO and one underwent total ear canal ablation (TECA). No recurrence was noted in the three cats that received treatment; no follow-up information was available for the cat that was recommended for VBO surgery.

Five cats had myringotomy procedures. Nine had cytology performed on the aural exudate (n = 4) or material obtained by myringotomy (n = 5). Samples from 9/16 cases (56.3%) were sent for culture and sensitivity testing; a variety of organisms were cultured, including Staphylococcus epidermidis and Staphylococcus aureus (with no significant antimicrobial resistance reported), Escherichia coli, anaerobes, Pasteurella multocida, Mycoplasma species and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Table 1) The specific organism did not appear to influence the treatment modality or outcome.

Table 1.

Bacterial culture and cytological findings

| Microorganism cultured | Aural exudate | Myringotomy | Cytological findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Not cultured | 1 | 0 | Rods and cocci |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | 1 | 0 | Malassezia species |

| Pasteurella multocida | 0 | 1 | No bacteria |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterococcus faecalis | 0 | 1 | Malassezia species |

| Escherichia coli and mixed anaerobes | 0 | 1 | Rods |

| Mycoplasma species | 1 | 0 | No bacteria |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 1 | 0 | Not performed |

| Culture negative | 0 | 1 | No bacteria |

| Mycoplasma species (cultured from nose) | 0 | 0 | Not performed |

Treatment

Of the 16 cats with OM, six were treated surgically and 10 were managed solely medically. Seven of the cats managed medically were treated with systemic antibiotics (cefovecin [n = 1], marbofloxacin [n = 1], clavulanate-potentiated amoxicillin [n = 4, with one switched to clindamycin], pradofloxacin [n = 1] and cefalexin [n = 1]), based on the results of culture and sensitivity testing. Two were treated with systemic itraconazole and one also treated topically because Malassezia species were seen on aural exudate cytology. The duration of treatment ranged from 10 days to 8 weeks. See supplementary table for a summary of treatments received by each cat.

Outcomes

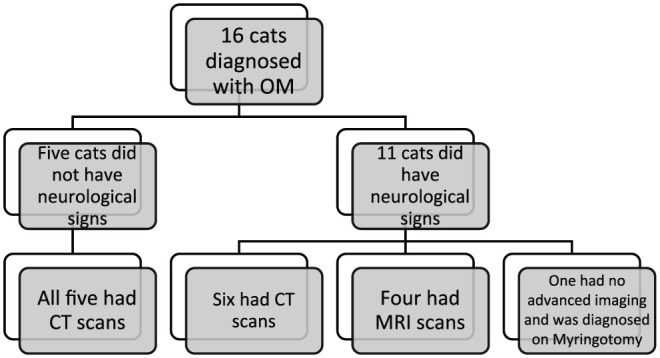

One cat had a follow-up CT scan 5 weeks later and one had radiographs after 1 year; both these cats were successfully managed medically, with no signs of bulla effusion seen on the images, which had been present previously. Two cats had continual signs of OE after being medically managed but no signs of OM. Six cats have had no signs of ear disease, either OE or OM, as far as follow-up allows. Of the two cats with concurrent otitis interna, one had continued ataxia and both had head tilt, although these signs were less pronounced than on initial presentation. Follow-up available ranged from 3 months to 2 years. Four cats were euthanased, all for unrelated problems. For two cats, there was no available follow-up information (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Flow diagram summarising the treatment outcomes for 16 cats diagnosed with otitis media (OM). TECA = total ear canal ablation; VBO = ventral bulla osteotomy

Discussion

Managing OM in cats with surgical intervention has been well described; 10 to the best of our knowledge there is very little information on medical management. This small, retrospective study shows some evidence that medical management with systemic antibiotics can be successful in treating cats with OM. The nine cats that were managed medically, for which follow-up was available, all appear to have been successfully treated. These results are potentially valuable for making clinical decisions when managing similar cases in future.

Although there were no specific selection criteria in this study, it should be noted that diagnosis of OM in these cats was not solely based on imaging findings; the cats also had to have presented with compatible clinical signs. Previous studies have found that 34 cats out of a cohort of 100 had signs of OM on CT scans of the head yet presented with no signs consistent with ear disease. 14

Studies show that CT and MRI are the most sensitive diagnostic imaging methods of diagnosing OM; 12 it is not, however, known if they are the gold-standard method for monitoring for relapse. Resolution in these cases was based on resolution of clinical signs. Future prospective studies may wish to definitively measure resolution with a combination of advanced imaging techniques.

There is a lack of evidence regarding the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in OM cases, whether for analgesia or to reduce inflammation. Although in these cases, it was used mainly for postoperative cases, there were some medically managed cats that also received NSAIDs. Each case was managed by clinicians from different specialities/disciplines so no standardised medical modality was used.

It is stated in some review articles that antimicrobial medication is a valid treatment option in both dogs and cats, whereas others state that topical or systemic antimicrobials are far from ideal in the treatment of OM.5,7,17 These conflicting stances suggest that there is limited good-quality evidence on how to use systemic antimicrobials to treat OM and in which situations they are more likely to succeed, with particularly limited evidence for cats, especially as most of the available evidence is anecdotal or opinion-based, rather than being based on clinical trials. In this study, the duration of antimicrobial therapy did not correlate with outcome, although some cats had shorter durations of treatment than a proposed length of 4–6 weeks. 18

Some authors have stated that systemic antimicrobial therapies may not be able to reach a sufficient concentration in feline and canine bullae, even when given at the maximum oral dose. 5

When planning to use systemic treatment in cats with OM, the results of bacterial culture are vital because this can influence which medication is prescribed. 18 Topical treatment may be effective even if culture indicates a resistant organism, owing to the higher concentrations of drugs that can be applied topically to the ear, in comparison with systemic concentrations. In two cases described, infection with Mycoplasma species was reported. Mycoplasma species infection has also been reported as a cause for OM and Mycoplasma felis is an increasingly recognised cause of disease in cats.19,20

This study is limited in that it was retrospective and not prospective; furthermore, the study population was very small. Even so, we hope that it will help to form the basis for further studies evaluating the success or otherwise of managing OM in cats with systemic antimicrobial treatment.

Conclusions

This small cohort shows that some cats with OM can be successfully managed medically. VBO and TECA are invasive surgical procedures that may not necessarily be required in these cases if appropriate medical management is undertaken.

Supplemental Material

Summary of treatments received by 16 cats with otitismedia

Footnotes

Supplementary material: Table: Summary of treatments received by 16 cats with otitis media.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCiD: Nicola Swales  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2500-3246.

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2500-3246.

Accepted: 10 November 2017

References

- 1. Hill PB, Lo A, Eden CA, et al. Survey or the prevalence, diagnosis and treatment of dermatological conditions in small animals in general practice. Vet Rec 2006; 158: 533–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. King A, Weinrauch S, Doust R, et al. Comparison of ultrasonography, radiography and a single computed tomography slice for fluid identification within the feline tympanic bulla. Vet J 2007; 173: 638–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. MacPhail C, Innocenti C, Kudnig S, et al. Atypical manifestations of feline inflammatory polyps in three cats. J Feline Med Surg 2007; 9: 219–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shell L. Otitis media and otitis interna. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 1988; 18: 885–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gotthelf L. Diagnosis and treatment of otitis media in dogs and cats. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2004; 34: 469–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McKeever P, Torres S. Ear disease and its management. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 1997; 27: 1523–1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rosychuk RAW, Bloom P. Otitis media: how common and how important? In: DeBoer DJ, Affolter VK, Hill PB. (eds). Advances in veterinary dermatology. Vol 6. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010, pp 345–353. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bacmeister C. Dyspnea in a cat with otitis media. Feline Pract 1991; 19: 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bruyette D, Lorenz M. Otitis externa and media: diagnostic and medical aspects. Semin Vet Med Surg Small Anim 1993; 8: 3–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Trevor P, Martin R. Tympanic bulla osteotomy for treatment of middle-ear disease in cats: 19 cases (1984–1991). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1993; 202: 123–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Anders B, Hoelzler M, Scavelli T, et al. Analysis of auditory and neurologic effects associated with ventral bulla osteotomy for removal of inflammatory polyps or nasopharyngeal masses in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2008; 233: 580–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Garosi L, Dennis R, Schwarz T. Review of diagnostic imaging of ear disease in the dog and cat. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 2003; 44: 137–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rhossmeisl J. Vestibular disease in dogs and cats. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2010; 40: 81–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shanaman M, Seiler G, Holt D. Prevalence of clinical and subclinical middle ear disease in cats undergoing computed tomographic scans of the head. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 2011; 53: 76–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Murphy K. A review of techniques for the investigation of otitis externa and otitis media. Clin Tech Small Anim Pract 2001; 16: 236–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Donnelly K, Tillson D. Feline inflammatory polyps and ventral bulla osteotomy. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet 2004; 26: 446–453. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kennis R. Feline otitis: diagnosis and treatment. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2013; 43: 51–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rosychuk RAW. Otitis media in cats (feline otitis media). Proceedings of the ESVD Otitis Workshop; 2017 June 1–3; Vienna, Austria. June, 2017, pp 79–84. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Le Boedec K. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between Mycoplasma spp and upper and lower respiratory tract disease in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2017; 250: 397–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ackerman AL, Lenz JA, May ER, et al. Mycoplasma infection of the middle ear of three cats. Vet Dermatol 2017; 28: 417–e102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Summary of treatments received by 16 cats with otitismedia