Abstract

Abstract

Functionally selective ligands to address specific cellular responses downstream of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCR) open up new possibilities for therapeutics. We designed and characterized novel subtype- and pathway-selective ligands. Substitution of position Q34 of neuropeptide Y to glycine (G34-NPY) results in unprecedented selectivity over all other YR subtypes. Moreover, this ligand displays a significant bias towards activation of the Gi/o pathway over recruitment of arrestin-3. Notably, no bias is observed for an established Y1R versus Y2R selective ligand carrying a proline at position 34 (F7,P34-NPY). Next, we investigated the spatio-temporal signaling at the Y1R and demonstrated that G protein-biased ligands promote a prolonged localization at the cell membrane, which leads to enhanced G protein signaling, while endosomal receptors do not contribute to cAMP signaling. Thus, spatial components are critical for the signaling of the Y1R that can be modulated by tailored ligands and represent a novel mode for biased pathways.

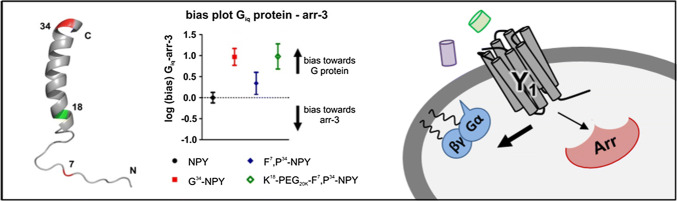

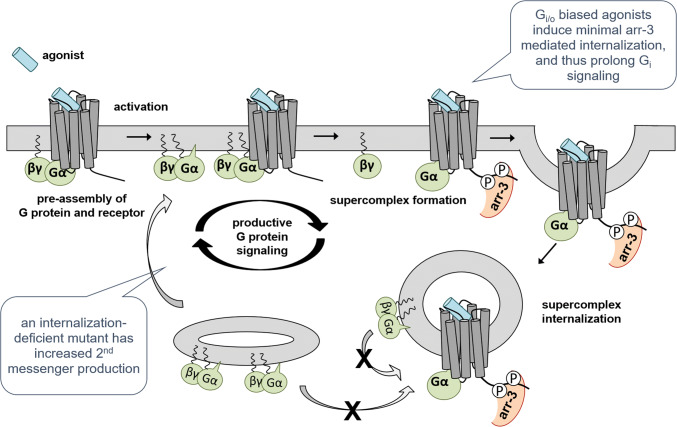

Graphic abstract

Keywords: GPCR, NPY, Signaling bias, Arrestin, G Protein

Introduction

Within the past years our knowledge on receptor activation and signaling has rapidly increased. To date, we know that the classical two-state receptor model is insufficient to describe the mechanism of receptor activation [1]. A multi-state model has evolved, which supports the existence of different inactive and active states of a receptor. Ligands as well as effector proteins may shift the conformational equilibria by conformational selection and/or induced fit [2, 3]. Thus, a specific ligand can favour distinct signaling pathways. In a clinical context, this may be used to optimize efficacy or reduce side effects of new pharmaceuticals. One of the first examples was TRV027, an arrestin-biased agonist of the angiotensin II type 1 receptor considered for the treatment of high blood pressure in patients with acute heart failure [4, 5]. While this particular compound did not reach the market [6, 7], this concept has gained a lot of interest and may be applied to any GPCR. However, functionally selective ligands have been reported so far for only a small subset of potentially clinically interesting receptors. Moreover, in multi-ligand/multi-receptor systems, the requirements for subtype specificity add another layer of complexity to the design of functionally selective ligands.

The neuropeptide Y1 receptor (Y1R), which is part of the neuropeptide Y (NPY) multi-ligand/multi-receptor system, is of high therapeutic interest [8]. NPY is a highly abundant neuropeptide in the brain [9], and orchestrates a number of partially opposing physiological functions through its receptors. While hypothalamic activation of the Y1R (together with the Y5R) stimulates food intake, Y2R conveys satiety signals [10, 11]. In the periphery, Y4R are highly expressed in the gastrointestinal tract and sense circulating levels of pancreatic polypeptide (PP) released in proportion to caloric intake [10–12].

In addition to its involvement in energy homeostasis and feeding, the Y1R is overexpressed in different cancer types like breast [13], prostate [14] and cortical tumors [15], making this receptor an interesting target for cancer targeting and treatment of obesity, respectively. In line with its physiologic relevance, a number of Y1R-specific antagonists have been identified [16–20], and recently the crystal structure of the antagonist-bound receptor has been determined [21]. Nonetheless, we still lack a mechanistic understanding of agonist recognition, receptor activation, and effector coupling.

The Y1R natively couples to the Gi/o family, and was also found to potently recruit arrestin-3 (arr-3) after ligand stimulation [22], which may act as a scaffolding protein or activator of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades [23]. However, the relative contribution of the G protein signal and potential arrestin-mediated effects to the observed physiological effects remain unclear. Thus, pathway-selective ligands are required to unravel the distinct pathways and design efficient therapeutics. Guided by our recent model of the native 36-amino acid peptide agonist bound to its receptor [21], we designed and characterized novel subtype- and pathway-selective ligands. Single amino acid substitutions at position 34 within the peptide and PEGylation resulted in agonists strongly favouring G protein signaling over arr-3 recruitment. We used different BRET assay set-ups to investigate the coupling to inhibitory G proteins as well as arr-3 recruitment and identified the novel NPY variants G34-NPY and K18-PEG20K-F7-P34-NPY as G protein-biased agonists for the Y1R. Furthermore, by studying the membrane residence and G protein receptor interaction, we demonstrate that increased duration at the membrane is a novel mechanism to induce G protein bias over arrestin-mediated signaling.

Experimental procedures

Peptide synthesis

NPY and the analogues G34-NPY and F7-P34-NPY were synthesized by 9-fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl/tert-butyl automated solid-phase peptide synthesis on Rink amide resin as reported before [24, 25]. The polyethylene glycol (PEG) modified NPY variant (K18-PEG20K-F7-P34-NPY) was also generated by automated solid-phase peptide synthesis with a modified sequence containing an orthogonally protected lysine residue (Fmoc-Lys(Dde)-OH) at position 18 (A18K), along with the N7F and Q34P exchanges that convey Y1R over Y2R preference. The selective PEGylation of this peptide with PEG of 20 kDa (PEG20K) was performed as described by Mäde et al. [26]. Briefly, the N-terminus of the peptide was protected with a photolabile Nvoc protecting group on resin, and the Dde protecting group on K18 was cleaved by repeated treatment with 2% hydrazine in dimethylformamide. The peptide was then cleaved from the resin in trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), and coupled to PEG20k-N-hydroxysuccinimide ester in solution. Finally, the free amino group at the N-terminus of the peptide is recovered by UV-irradiation. All peptides were purified to > 95% by reversed-phase HPLC using linear gradients of solvent B (acetonitrile + 0.08% trifluoroacetic acid) in A (H2O + 0.01% trifluoroacetic acid), and peptide identity was confirmed by MALDI-ToF mass spectrometry (Ultraflex III MALDI ToF/ToF, Bruker, Billerica, USA). Analytical data are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Functional characterization of different ligands at the Y1 receptor

| at Y1R | Analytical data | Binding | GαqΔ6i4myr | Gi/o | arr-3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peptide | Mcalc/Da | Mobs [M+H]+ /Da | Purity/%a,b | Ki (nM) (pKi ± SEM) | EC50 (nM) (pEC50 ± SEM) | EC50 (nM) (pEC50 ± SEM) | EC50 (nM) (pEC50 ± SEM) |

| NPY | 4251.1 | 4252.1 | > 95a2,b2 | 0.6 (9.20 ± 0.20) | 0.6 (9.24 ± 0.05) | 0.1 (10.00 ± 0.08) | 2.9 (8.54 ± 0.07) |

| G34-NPY | 4180.1 | 4181.1 | > 95a1, b1 | 9.3 (8.03 ± 0.08) | 3.7 (8.43 ± 0.07) | 0.3 (9.56 ± 0.11) | 186 (6.73 ± 0.17) |

| F7,P34-NPY | 4253.1 | 4254.1 | > 95b1,b3 | 0.2 (9.62 ± 0.09) | 0.5 (9.33 ± 0.13) | 0.1 (9.88 ± 0.09) | 4.7 (8.33 ± 0.15) |

| K18-PEG20K-F7,P34-NPY | 25,326 | 25,347 | > 95b2,b3 | 3.3 (8.48 ± 0.07) | 2.0 (8.69 ± 0.07) | 0.2 (9.69 ± 0.14) | 107 (6.97 ± 0.22) |

Peptide identities were confirmed by MALDI-ToF mass spectrometry and purity of > 95% by RP-HPLC. Binding affinities were measured by competition of 75 pM 125I-PYY at membrane preparations of stably transfected HEK293-Y1R-eYFP cells, and the Ki was fit incorporating the Cheng-Prusoff-correction with a Kd of 203 ± 32 pM determined under the same experimental conditions. Functional data were obtained in transiently transfected HEK293 cells: G protein activation was determined downstream of a chimeric GαqΔ6i4myr by accumulation of inositol phosphates, and downstream of the native Gi/o proteins using a CRE-reporter gene system, respectively. Arr-3 recruitment was measured by BRET to an RLuc8-Arr3 fusion protein. Functional data (Ki/EC50) represent global fit of n ≥ 3 independent experiments conducted in technical triplicate, calculated molecular weight refers to the monoisotopic mass

aGradients: (a) 10–60% B in 30 min, (b) 20–70% B in 40 min

bRP-HPLC columns: (1) Phenomenex Proteo C18, 90 Å; (2) GraceVydac C18, 300 Å; (3) Phenomenex Aeris XB-C18

Plasmid construction

The Y1R within the eYFP_N1 expression vector (Clontech) was used for fluorescence microscopy, arrestin BRET experiments, IP-one assays and binding assays [27]. The Renilla luciferase 8 tagged Y1R in pcDNA3 vector [28] and the Y1R in pVitro2-hygro-mcs vector (Cayla-Invivogen) without fluorescence tag [29] were used for G protein BRET experiments or supercomplex formation BRET studies, respectively. For control experiments, we used an internalization deficient variant of the Y1R [29, 30], designated Y1-NC. This variant contains seven amino acid mutations in its C-terminus (S353A, T354A, T357A, D358A, S360A, T362A, S363A) that were introduced into the parent expression vectors Y1R-eYFP_N1; Y1R_Rluc8_pcDNA3 and Y1R_pVitro2 by site-directed mutagenesis.

Bovine arr-3 was C-terminally fused to mCherry for fluorescence microscopy. For BRET assays, it was N-terminally fused to Renilla luciferase 8 [31]. The untagged chimeric GαΔ6qi4myr protein was used for signal transduction studies to re-route cellular signaling towards the phospholipase C pathway and production of inositol phosphates (kindly provided by E. Kostenis, Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität, Bonn, Germany) [32]. The BRET experiments were performed with chimeric GαΔ6qi4myr, Gαi and Gα0 protein bearing a monomeric Venus fluorophore within the helical domain after F120 (Gα0A), M119 (Gαi1) or P127 (GαΔ6qi4myr) spaced by a poly-Ser/Gly-linker as described previously [25]. The identity of all plasmid constructs were verified by Sanger dideoxy sequencing.

Cell culture

HEK293 cells (DSMZ) were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) with 4.5 g/l glucose and l-glutamine and Ham’s F12 (1:1, v/v; Lonza) supplied with 15% (v/v) heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS; Lonza). To the media of stably transfected HEK293 cells 100 µg/ml hygromycin was added. SK-N-MC cells (ATCC) were cultivated in Eagle’s Minimal Medium (EMEM; Lonza) supplemented with 10% FCS, 4 mM L-glutamine (Lonza), 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Lonza), and 0.2 × MEM nonessential amino acids (Lonza). All cells were kept in a humidified atmosphere at 37 °C and 5% CO2. The cells were routinely tested negative for mycoplasma.

Fluorescence microscopy

For visualization of receptor internalization and arrestin recruitment, HEK293 cells were seeded onto µ-slide 8 wells (ibidi), and at 70–80% confluence co-transfected with 900 ng Y1R-eYFP-N1 plasmid and 100 ng P3-Arr-3-mCherry using Lipofectamine® 2000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. 24 h post transfection, the cells were serum-deprived with Opti-MEM® reduced serum medium (Gibco®) containing 2.5 µg/ml Hoechst33342 (Sigma) for 30 min at 37 °C. Fluorescence microscopic studies were performed with a Zeiss Axio Observer.Z1 inverted microscope (filters 46 for YFP, 31 for mCherry, and 02 for Hoechst33342 stain) equipped with an ApoTome Imaging System and a Heating Insert P Lab-Tek S1 unit. After documentation of the unstimulated cells, cells were stimulated with 10–7 M peptide solution for indicated time periods.

Binding assay

Binding assays were performed with membrane preparations of HEK293 cells. Generation of membrane preparations and procedure of binding assay were described previously [25] and were adapted with minor modifications. Membranes containing 2 µg of total protein (wild-type Y1R-eYFP; obtained from stably transfected Y1R-eYFP-HEK293) or 3.5 µg total protein (Y1-NC; from transiently transfected HEK293 cells) were incubated with 80 pM 125I-PYY (NEX240; Perkin Elmer, Waltham/MA, USA) and increasing concentrations of cold competitor in Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) containing 1% (w/v) BSA and 5 mM Pefabloc protease inhibitor in a total volume of 100 µl. The incubation was terminated after 4 h at room temperature under gentle agitation.

Inositol phosphate accumulation assay

HEK293 cells were seeded into 6-well plates. At 70% confluency, the cells were co-transfected with 1400 ng plasmid encoding the GαΔ6qi4myr protein and 5600 ng Y1-eYFP-N1 plasmid using Metafectene® Pro (Biontex) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. 24 h post transfection, cells were re-seeded into white 384-well plates (Greiner Bio-one) at a density of 20,000 cells per well. One day later, the medium was discarded and the cells were stimulated with peptide diluted in HBSS containing 20 mM LiCl (15 μl/well) for 90 min at 37 °C. The amount of produced inositol phosphates was quantified using the IP-one Gq assay kit (Cis-Bio) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. It was verified that signals fall within the linear range of HTRF detection, and the results was normalized to the minimum/maximum signal of NPY at the Y1R.

cAMP reporter gene assay

HEK293 cells were seeded into 6-well plates and grown to 70% confluency. The cells were then co-transfected with 2500 ng of the Y1R-eYFP-N1 plasmid and 1500 ng of the commercial reporter gene vector pGL4.29[luc2P/CRE/Hygro] using Metafectene® Pro (Biontex) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. SK-N-MC cells endogenously expressing the Y1R [33, 34] were transfected with 1500 ng pGL4.29 or empty vector as a control. The pGL4.29 vector expresses a synthetic hPEST-destabilized luciferase protein under the control of a cAMP response element, allowing for more dynamic measurements of gene induction. 24 h after transfection, the cells were re-seeded into white 384-well plate at a density of 20,000 cells/well. The following day, the medium was discarded and the cells were stimulated with peptide dilutions in DMEM containing 1 μM forskolin for 2.5 h at 37 °C (20 μl/well). The plate was then re-equilibrated to room temperature for 15 min and the stimulation was terminated by adding 20 μl of OneGlo substrate (Promega) in lysis buffer. Five minutes after substrate addition, luminescence was measured in a plate reader (Tecan Infinite M200 or Spark; Tecan) with a signal integration time 1000 ms, and the results were normalized to the minimum/maximum signal of NPY at the Y1R.

BRET-assay

All BRET experiments were performed with transiently transfected HEK293 cells. For the investigation of arr-3 recruitment, cells were seeded in 75 cm2 flasks and co-transfected with 47.100 ng Y1-eYFP plasmid and 900 ng RLuc8-Arr-3 plasmid. To examine the formation of a supercomplex, HEK293 cells were seeded in 25 cm2 flasks and co-transfected with 2000 ng Y1R DNA, 200 ng RLuc8-Arr-3 plasmid and 7800 ng Gα0-Venus plasmid. For the G protein BRET saturation curves, cells were seeded into 6-well plates and co-transfected with a gradient of Venus-tagged G protein (0–1900 ng) and 100 ng Y1-RLuc8 DNA. The total DNA amount of 2000 ng was balanced with empty pcDNA3 vector. The kinetic G protein BRET studies were conducted at saturating F/L ratio using the maximal excess of Gα-Venus. The transfections were performed using 3 μl MetafectenePro (Biontex) per μg DNA according to manufacturer`s protocol. 24 h post transfection, cells were re-seeded into poly-D-lysine coated white (for BRET measurements) or black 96-well plates (Greiner Bio-one) for quantification of acceptor expression levels. 48 h post transfection, BRET assays were measured as described previously [25, 29]. Briefly, the experiments were carried out in HBSS buffer containing 25 mM HEPES and 4.2 μM Coelenterazine h (Nanolights) in a total volume of 200 μl with the indicated peptide concentrations. The BRET signal was recorded in a Tecan infinite M200 or Tecan Spark reader using filter set Blue1 (luminescence 370–480 nm) and Green1 (fluorescence 520–570 nm). The BRET ratio was calculated as the ratio of fluorescence to luminescence values, and the netBRET signal was determined by subtracting BRET signals of unstimulated cells from stimulated samples. To quantify the expression levels of the BRET acceptor (Venus) in saturation BRET assays, the fluorescence (F) was measured by direct excitation [Exc 488(9), Em 530(20)] in black plates and was divided by the basal luminescence (L) of donor-only transfected cells to calculate the F/L ratio (x axis).

Statistical analysis and generation of bias plots

Nonlinear regression and calculation of means, SEM. and statistical analysis were determined using PRISM 5.0 (GraphPad Software). Significances were calculated by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post test. Saturation BRET experiments were fit for one site total binding to account for a nonspecific component by random collision (bystander BRET), and BRET50 as well as max. BRET were calculated.

The generation of the bias plot was performed as described [35, 36]. Essentially, the peptide response was first internally referenced to the native agonist NPY for every readout to obtain ΔlogEC50, and correct for potential differences in assay sensitivity. In a second step, the between-pathway differences were calculated (ΔΔlogEC50). By definition, the ΔΔlogEC50 for the reference agonist NPY is 0. All calculations were performed on log scale and errors were propagated [√((SEMi)2 + SEMj)2)].

Results

Synthesis and binding affinity of chemically diverse Y1R agonists

Large efforts have been made in the past to develop agonists with high subtype specificity for the Y1R. Substitutions at positions Q34 to proline (as found in the related pancreatic polypeptide) provided peptide variants with very high Y1R versus Y2R specificity [37] and are the basis for the most widely used Y1R specific agonists L31,P34-NPY and F7,P34-NPY. The recent structural model of neuropeptide Y bound to the Y1R based on the crystal structure of the receptor bound to an antagonist [21] rationalized these findings, as Q34 is located in a solvent-exposed, turn-like structure. Thus, we reasoned that alternative substitutions at this position might lead to Y1R specific agonists with potentially altered signaling profile. We decided to introduce a glycine residue at this position because it is small and allows for unique backbone torsion angles. The set of peptides was complemented by addition of a large polyethylene glycol moiety (PEG20K) to the established Y1R-preferring agonist F7,P34-NPY at position 18 within the amphipathic helix of NPY, which has been shown to well tolerate addition of large boron clusters [38]. For agonists of the related Y2R and Y4R, PEGylation impaired arr-3 recruitment while retaining activity towards the G protein pathway [26]. The amino acid sequences and the substituted positions within NPY are displayed in Fig. 1a, b and their analytical data are given in Table 1.

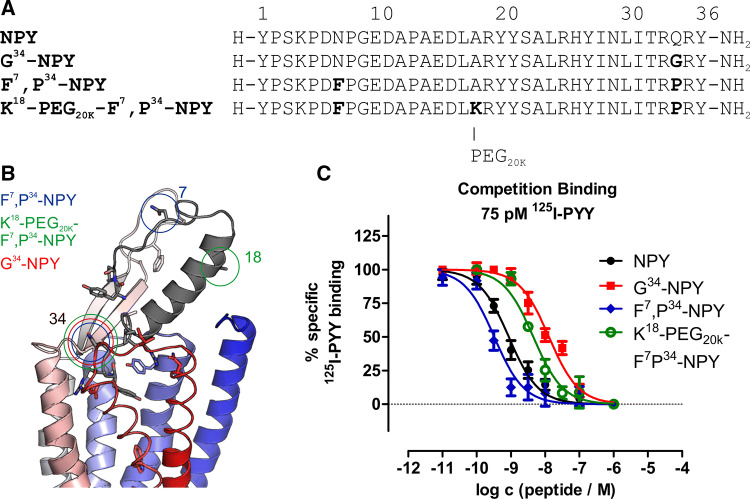

Fig. 1.

NPY and NPY derivates binding to the Y1R. a Amino acid sequences of porcine NPY, G34-NPY, F7,P34-NPY and K18-PEG20K-F7,P34-NPY with altered amino acids in bold letters. b Model of NPY bound to the Y1R,

modified from Yang et al. [21]. Positions 7, 18 and 34 used for modification are highlighted in circles. c Binding of peptides to the Y1R was measured by competition binding experiments with 125I-PYY (75 pM) of membrane preparations of stably transfected HEK293-Y1R cells and is displayed as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments performed in technical triplicate

First, we determined receptor binding affinities in competition binding experiments against 125I-labelled PYY (Fig. 1c). All ligands were potent binders at the Y1R with IC50 values in the low nanomolar range. Interestingly, F7,P34-NPY displayed an even higher affinity than the native ligand NPY (0.4 nM vs 1.5 nM), while the PEGylated variant and G34-NPY were slightly less affine with IC50 values of 4.5 nM and 16 nM, respectively (Table 1).

Comparison of G protein activation and arr-3 recruitment reveals ligand bias

We have identified G34-NPY and K18-PEG20K-F7,P34-NPY as novel Y1-binding peptides. Thus, we next screened for activity and selectivity of these analogues towards all human Y receptors (Fig. 2, Table 2). To facilitate the analysis, we co-transfected a chimeric Gαiq protein (GαqΔ6i4myr) that re-routes the native Gi pathway to the phospholipase pathway [32] and measured accumulation of cellular inositol phosphates. At the Y1R, G34-NPY and K18-PEG20K-F7,P34-NPY were slightly less active compared to NPY and F7,P34-NPY (4- and sixfold, respectively). However, they displayed great selectivity of Y1R over Y2R activation. Similar to F7,P34-NPY [37, 39], G34-NPY was > 400fold less potent than NPY at the Y2R, and the PEGylated variant K18-PEG20K-F7,P34-NPY was even more selective (> 10,000 fold). This leads to a switch towards Y1R over Y2R preference, and the relative rate of Y1R activation is increased by at least sevenfold (G34-NPY) up to > 4000-fold for K18-PEG20K-F7,P34-NPY compared to the native agonist NPY.

Fig. 2.

Selectivity profile of NPY derivatives at human Y receptors. Receptor activation was measured by accumulation of cellular inositol phosphates downstream of a chimeric Gαiq protein (GαqΔ6i4myr) that re-routes the native Gi/o pathway to the phospholipase pathway. Shown is mean ± SEM of n ≥ 3 independent experiments conducted in triplicate. Numerical values can be found in Table 2

Table 2.

Selectivity profile of NPY derivatives at human Y receptors

| Y1R | Y2R | Y4R | Y5R | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| peptide | EC50/nM (pEC50 ± SEM) | fold NPY | EC50/nM (pEC50 ± SEM) | fold NPY | gain selec. Y1Ra | EC50/nM (pEC50 ± SEM) | fold NPY | gain selec. Y1Ra | EC50/nM (pEC50 ± SEM) | fold NPY* | gain selec. Y1Ra |

| NPY | 0.6 (9.24 ± 0.05) | (1) | 0.05 (10.31 ± 0.07) | (1) | − | 27 (7.57 ± 0.17) | (1) | – | 0.3 (9.46 ± 0.05) | (1) | − |

| G34-NPY | 3.7 (8.43 ± 0.07) | 6 | 23.4 (7.63 ± 0.10) | 479 | 74 | > 300 (< 6.5) | > 12 | > 2 | 4.7 (8.33 ± 0.06) | 13 | 2 |

| F7,P34-NPY | 0.5 (9.33 ± 0.13) | 1 | 15 (7.82 ± 0.10) | 309 | 380 | 0.6 (9.25 ± 0.13) | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.2 (9.61 ± 0.07) | 1 | 1 |

| K18-PEG20k-F7,P34-NPY | 2.0 (8.69 ± 0.07) | 4 | 724 (6.14 ± 0.30) | > 10.000 | > 4000 | 60 (7.22 ± 0.08) | 2 | 0.6 | 18 (7.74 ± 0.05) | 52 | 15 |

Receptor activation was measured by accumulation of cellular inositol phosphates downstream of a chimeric Gαiq protein (GαqΔ6i4myr) that re-routes the native Gi/o pathway to the phospholipase pathway. Related to Fig. 2

aGain of selectivity for the Y1R compared to the native agonist NPY, calculated from the normalized shifts relative to NPY at the receptors. Values > 1 reflect increased selectivity for the Y1R compared to NPY, while values < 1 indicate loss of preference for the Y1R compared to NPY. We chose not to present the direct potency ratios of a particular peptide at different receptors, as this depends on the assay sensitivity, and is therefore not transferable to other assay systems

At the Y4R, the novel Y1-binding peptides behaved drastically different from the previous P34-based analogues. F7,P34-NPY significantly gained activity at this receptor and was about fivefold more potent than NPY, which is equivalent to a reduction in the Y1R/Y4R activity ratio (relative to NPY) to 1/33 and hence, severe loss of the natural selectivity against the Y4R. PEGylation at position 18 abolished this effect and had potencies similar to NPY. Thus, the natural selectivity of NPY against the Y4R is largely preserved for this analogue. (The native ligand hPP has sub-nanomolar potencies at this receptor [40, 41]). Strikingly, G34-NPY displayed an even weaker activation of the Y4R (EC50 > 300 nM), which further increases the natural Y1R/Y4R selectivity of NPY by twofold. Moreover, the novel peptides also improved Y1/Y5 receptor selectivity. G34-NPY was about onefold, K18-PEG20K-F7,P34-NPY fivefold less potent at the Y5R compared to NPY and F7,P34-NPY, which increases the Y1R/Y5R activity ratio compared to NPY by 2- and 15-fold, respectively. Thus, these two peptides display the best Y1R selectivity described for peptidic agonists so far.

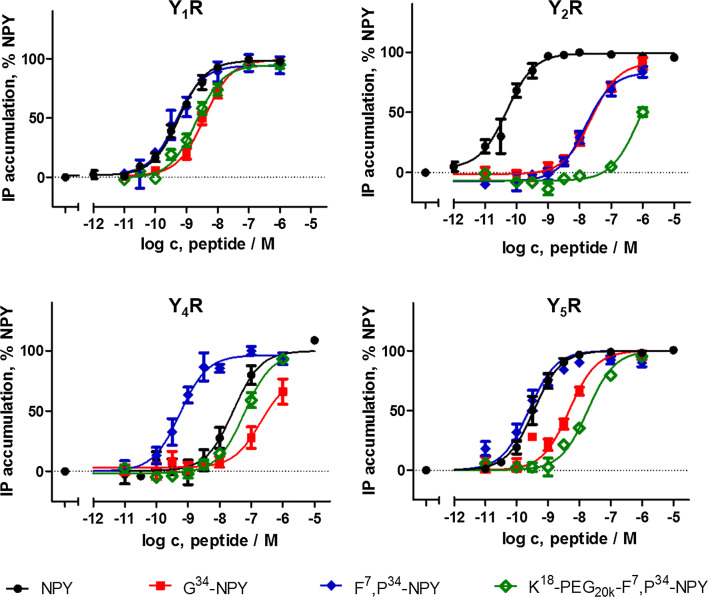

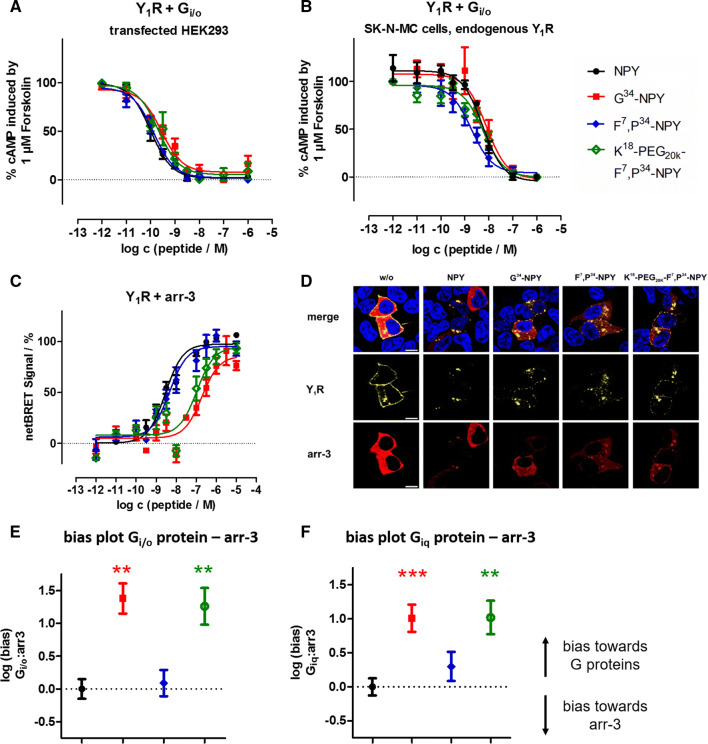

Next, we characterized the functional activity of the ligands at the Y1R in more detail and also determined activity in the native Gi/o pathway by a cAMP reporter gene assay (Table 1, Fig. 3a, b) and arr-3 recruitment (Table 1, Fig. 3c, d). In agreement with the data obtained with the unnatural, chimeric Gαiq protein, NPY and F7,P34-NPY were essentially equipotent in the Gi/o pathway, and G34-NPY and K18-PEG20K-F7,P34-NPY had a ~ threefold decreased potency compared to NPY, with all peptides eliciting the full response. We further measured Gi/o activation in SK-N-MC cells, which endogenously express the Y1R [33, 34]. Also in this more endogenous situation, the novel peptides activate the receptor and the potency differences to NPY are negligible.

Fig. 3.

Novel Y1R agonists display impaired arr-3 recruitment and receptor internalization, leading to a net bias towards the G protein pathway. a, b CRE reporter gene assay to determine the activity of the peptides at the Y1R in the endogenous Gi/o pathway in transiently transfected HEK293 (a) and SK-N-MC cells endogenously expressing the Y1R (b). c BRET experiments with Y1R fused to eYFP and RLuc8-arr-3 in transiently transfected HEK293 cells. Cells were stimulated with peptide variants for 5 min. d Internalization and arr-3 recruitment was detected by fluorescence microscopy prior to (w/o) and after stimulation with 100 nM of Y1R ligands. Y1R is C-terminally fused to eYFP (yellow) and arr-3 is C-terminally tagged with mCherry (red). Nuclei were stained with Hoechst33342 (blue), n ≥ 2. (scale bar = 10 µm). e, f Ligand bias plot generated from arr-3 recruitment versus G protein activation downstream of the native Gi/o or chimeric Giq pathway in transfected HEK293 cells (cf. Table 1). Shown are the mean between-pathway differences (ΔΔlogEC50 ± SEM), and the statistical significance was tested by one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s post test compared to NPY, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

The ability of the ligands to induce arr-3 recruitment at the Y1R was tested by means of a bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) assay, using the eYFP tagged Y1R as in binding and G protein activation studies, and an arr-3 variant N-terminally fused to Renilla luciferase 8. Arr-3 recruitment to the Y1R is maximal after 5 min of peptide stimulation [29], and all concentration–response-curves were recorded at this time point. NPY and F7,P34-NPY most efficiently induced arr-3 recruitment to the receptor. Introduction of the PEG20K moiety at position 18 reduced the potency to recruit arr-3 by more than threefold compared to the parent peptide, and G34-NPY was almost sevenfold less potent than NPY (Table 1; Fig. 3c).

Calculation of the signaling bias ΔΔ Giq – arr-3 and ΔΔ Gi/o – arr-3, referenced to the native agonist NPY and thus corrected for the different assay sensitivities, illustrates that arr-3 recruitment is affected more drastically by the variants compared to G protein activation. This led to a significant onefold bias for G34-NPY and K18-PEG20K-F7,P34-NPY towards the G protein pathway (Fig. 3e, f).

The ability of the different ligands to induce arr-3 recruitment was also qualitatively studied by fluorescence microscopy in living HEK293 cells, using an arr-3 variant fused to mCherry. After stimulation with 100 nM peptide solution for 10 min, arr-3 recruitment was weaker for cells stimulated with G34-NPY and K18-PEG20K-F7,P34-NPY compared to cells treated with NPY or F7,P34-NPY, respectively (Fig. 3d, bottom). In agreement with recent studies on the molecular interaction of the Y1R with arr-3 [29], the receptor-arr-3 complexes are bound tightly, and arr-3 is co-internalized and, therefore, predominantly located in intracellular vesicles. Inspection of the receptor fluorescence in the same experiment further indicates that the impaired arr-3 recruitment also translated into reduced receptor internalization (Fig. 3d, middle), with some residual receptor still present at the cell membrane.

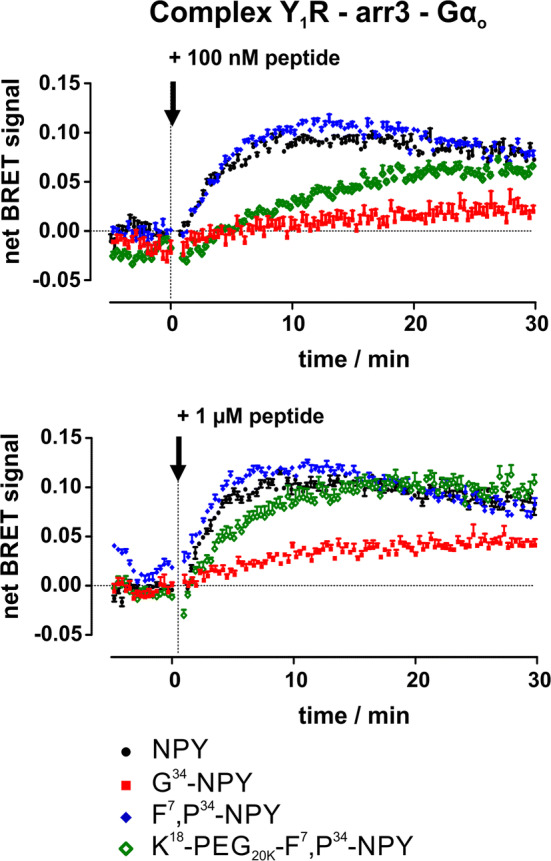

Reduced recruitment of arrestin impairs supercomplex formation

The formation of a supercomplex consisting of Gα0 protein and arr-3 bound simultaneously to the Y1R after stimulation with NPY was described recently using unlabelled receptor, Venus-labelled Gα0 protein and arr-3 N-terminally fused to Rluc8 [29]. Here, we tested whether a supercomplex can be formed by stimulation with G protein-biased ligands (Fig. 4). After incubation with 100 nM of NPY or F7,P34-NPY a rapidly increasing netBRET signal of Gα0 protein and arr-3 was detected, whereas stimulation with 100 nM G34-NPY or K18-PEG20K-F7,P34-NPY resulted in a slower and decreased netBRET signal, respectively. For K18-PEG20K-F7,P34-NPY, the netBRET signal was increased to the NPY level with higher peptide concentration (1 µM). The netBRET signal also increased after stimulation with 1 µM G34-NPY, albeit not reaching the level of the native agonist NPY. Thus, these data demonstrate that a supercomplex may also be formed after stimulation with moderately G protein-biased ligands but to a significantly lower extent.

Fig. 4.

Formation of a supercomplex after stimulation with biased ligands. The formation of a supercomplex between Y1 receptor, G0-Venus and RLuc8-arr-3 was studied in kinetic BRET experiments. Transiently transfected HEK293 cells were stimulated with 100 nM or 1 µM of different ligands for 30 min (technical lag time after stimulation 30 s). Shown are buffer-corrected representative examples of n = 3 independent experiments conducted in technical triplicate

Pre-assembly and dissociation of inhibitory G proteins to the Y1R

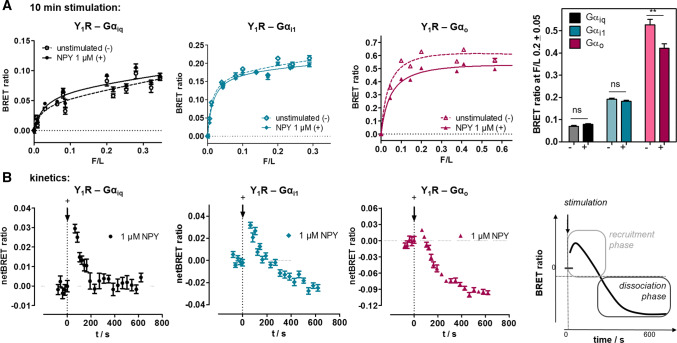

To characterize the molecular details of the observed signaling bias, we investigated next the interaction between the Y1R and its cognate G proteins (Fig. 5). We used BRET pairs consisting of the Y1R C-terminally fused to RLuc8 [29], and the alpha subunits of either the chimeric Giq, or the native Gi1 or G0 protein, respectively, fused to Venus fluorophores within their helical domain [25]. Saturation BRET experiments showed a saturable basal BRET signal in unstimulated cells in particular for Gαi1 and Gαio, and to a lesser extent also for Gαiq, indicating that these G proteins are pre-assembled at the Y1R (Fig. 5a, dashed line). Although all three G proteins display the same trend, the amount of pre-assembly appeared most pronounced for Gαo. Likely, an improved orientation of the BRET pair contributed to this effect, while the apparent affinity constants (BRET50, F/L ratio at half maximal BRET signal) are in the same range, indicating similar protein/protein affinities. After stimulation with saturating concentrations of the native ligand NPY, the BRET signal showed a biphasic behaviour in kinetic measurements (Fig. 5b). First, the BRET signal was increased (seconds), followed by a decrease that reached equilibrium after 10 min. The differences between the basal and the net BRET signals after 10 min are summarized in Fig. 5a (right panel) displaying a significantly decreased BRET signal for the G0 protein after NPY stimulation.

Fig. 5.

Pre-assembly and dissociation of Y1 receptor to inhibitory G proteins studied by saturation and kinetic BRET experiments. a Saturation BRET experiments of Y1-RLuc8 with different concentrations of chimeric Gα∆6qi4myr(Gαiq)-Venus, Gαi1-Venus or Gαo-Venus in transiently transfected HEK293 cells. BRET signal in the basal state in particular for Gαi1 and Gαio is saturable and indicates pre-assembly of the complex. Stimulation with 1 µM NPY for 10 min hardly changes BRET ratios for Gαiq but decreases BRET for Gαi1 and Gαio. Right panel: Comparison of BRET signal at a F/L ratio of 0.2 prior to stimulation (−) and after agonist stimulation for 10 min ( +). Columns are compared by two-tailed t-test. Shown is mean ± SEM of n ≥ 3 experiments conducted in technical quadruplicate. b Kinetic BRET experiments of the same constructs at saturating F/L ratio (F/L > 0.2) to resolve ligand effects on Y1R- Gα interactions. The BRET signal prior to stimulation was recorded for 2 min and the baseline was set to 0. After ligand stimulation (technical lag time 30 s), there was a short increase of the BRET signal, interpreted as recruitment, followed by a decrease of the BRET signal to (Gαiq) and below the baseline (Gαi1 and Gαio), interpreted as complex dissociation. Shown are buffer-corrected representative examples of n = 3 independent experiments conducted in technical quadruplicate

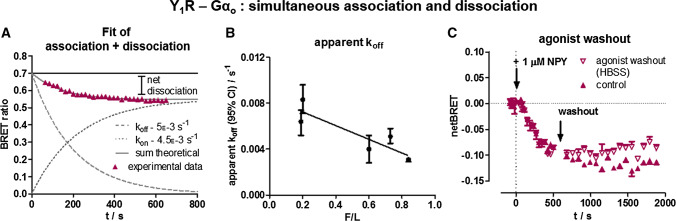

We suggest the biphasic behaviour as a first phase of G protein recruitment, followed by dissociation of the complex. Interestingly, the dissociation plateau only amounts to about 20% of the basal BRET observed. While it is conceivable that part of the receptor-G protein complexes do not respond to ligand stimulation because they reside in inaccessible intracellular vesicular structures (cf. Fig. 3d in the basal state), we suspected re-association of Go to the receptor as a contributing factor, in line with the significant pre-assembly (and hence, affinity) of the complex. To resolve these issues, we looked more closely into the kinetics of dissociation and performed agonist-washout experiments utilizing the Y1R-Go complex that displayed the best signal window (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

The kinetic BRET profile of the Y1R-Go complex contains an association component. a The limited experimentally observed net dissociation can be explained by an additional re-association component of Go to available receptors. The observed net dissociation accordingly corresponds to receptors that are not available by internalization. b In line with this hypothesis, a slower apparent dissociation is observed when higher amounts of Gαo-Venus are expressed, which would accelerate kon. c After agonist washout the signal approaches the baseline only very slowly, likely due to re-association of Go to recycled Y1 receptors. Shown is a buffer-corrected representative example of n = 3 independent experiments conducted in technical quadruplicate

Interestingly, we found that the dissociation kinetics differ with the amount of G protein present. At higher F/L ratio (more Gαo-Venus), koff-rate was slowed, indicating that this is an apparent rate constant, which is in fact a sum of dissociation (koff) and re-association (kon). As the amount of G protein increases, the association reaction becomes faster (kobs = kon × [c]), thus decreasing the apparent koff. It is obvious that the plateau of the association must be equal to the observed plateau of the apparent complex dissociation to fit the experimental data, and a ratio of kon/koff = 0.9 for the single components reflects the experimental kinetics best. The data suggest that receptors that are internalized in the endosomal compartment, do not associate with Go. This is also supported by washout experiments. Agonist washout did not change the BRET signal immediately, and the signal approached the baseline only very slowly, suggested to be due to re-association of Go to recycled Y1 receptors.

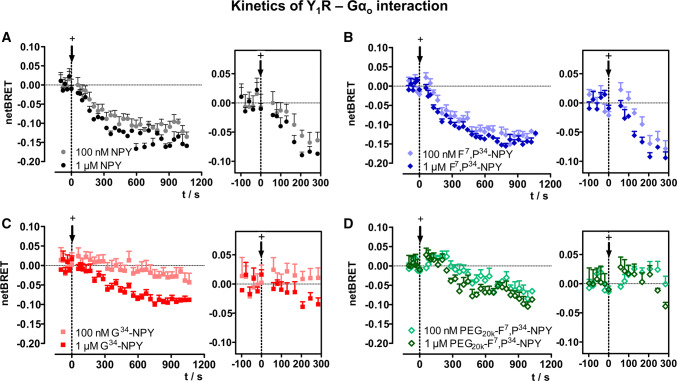

G protein-biased agonists prolong the interaction between Y1R and Gαo

We next performed kinetic analyses in response to the biased Y1R agonists to clarify whether and how they alter receptor—G protein interactions (Fig. 7). For this purpose, we chose the interaction between Y1R and Gαo as this provides the most robust signal window in BRET, but is qualitatively similar to the Gαi(1) protein which is the other endogenous signaling relay. Similar to the endogenous ligand NPY, the unbiased Y1R-preferring ligand F7,P34-NPY led to a brief transient increase, followed by a strong decrease of the BRET signal after stimulation with 100 nM and 1 µM ligand concentration (Fig. 7a, b) that reaches an equilibrium after ~ 15 min. In contrast, stimulation with 100 nM G34-NPY showed a weak, but prolonged recruitment phase up to 5 min and only a minimal decrease of the BRET signal below control in the later stage. Increasing the concentration of G34-NPY to 1 µM, however, elicits a reduction of the BRET signal after approximately 5 min which amounts to 55% of the ΔBRET seen for NPY after 15 min (ΔBRET 0.09 versus 0.16 at 900 s; Fig. 7a, c). Similarly, after stimulation with the PEGylated agonist K18-PEG20K-F7,P34-NPY, the increase of the BRET signal directly after stimulation was prolonged, and the dissociation phase was slowed and reduced, both, at 100 nM and 1 µM agonist concentration (Fig. 7d).

Fig. 7.

Biased ligands prolong the Y1R-Gαo interaction. Kinetic BRET between Y1-RLuc8 and Gαo-Venus at saturating F/L ratio (F/L > 0.2) is shown in response to the different ligands. The BRET signal prior to stimulation was recorded for 2 min, and the baseline was set to 0. Insets (right panel) show the first 5 min after ligand addition ( +). While the BRET decreases by ~ 0.15 for NPY (a) and F7,P34-NPY (b) over 1000 s, this is significantly reduced for the G protein-biased agonists G34-NPY (c) and K18-PEG20K-F7,P34-NPY (d). Shown are buffer-corrected representative examples of n = 3 independent experiments conducted in technical quadruplicate

Productive G protein signaling only occurs at the plasma membrane, not from internalized Y1R

This prolonged interaction between receptor and G protein in the kinetic BRET experiments along with the delayed internalization and supercomplex formation suggest that alterations in the spatiotemporal profile of receptor–effector interactions contribute to the observed G protein bias of G34-NPY and K18-PEG20K-F7,P34-NPY. As the biased ligands reduce arr-3-interactions, the residence time at the plasma membrane in a ligand-bound, active (towards G protein) state is prolonged, which promotes increased/prolonged G protein signaling. In turn, however, this implies that G protein signaling from endosomal compartments including the ‘supercomplex’ is limited, allowing the G protein-biased ligands to compensate their lower affinities/potencies relative to the native agonist NPY over time.

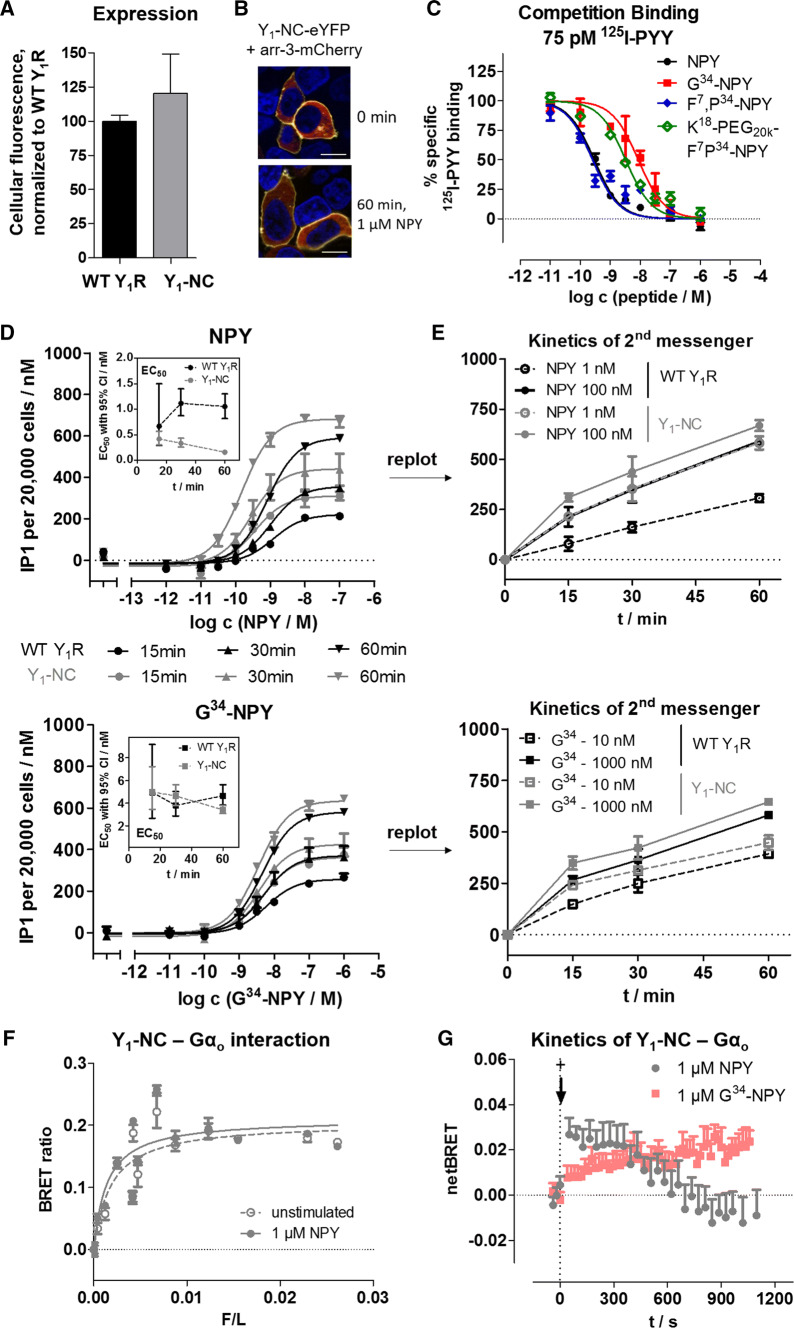

To confirm this hypothesis, we performed a series of experiments comparing the wild-type Y1R with a C-terminally mutated variant that does not recruit arr-3 or internalize, designated Y1-NC [29, 30], which contains seven amino acid exchanges in its C-terminal tail. This receptor variant is expressed at similar levels compared to the wild type (Fig. 8a), and we also confirmed lack of arr-3 recruitment (Fig. 8b, Table 3) in our setting and wild type-like binding affinities (Fig. 8c, Table 3). Interestingly, however, the EC50 in a second messenger accumulation set-up is about fivefold left-shifted (Fig. 8d, Table 3) compared to the wild type after a stimulation time of 60 min. Time-resolved analysis revealed that the Y1-NC variant accumulates inositol phosphates much faster and has a constant to slightly decreasing EC50 over time. In contrast, the EC50 of the wild-type receptor increased over time, consistent with a reduction of the receptor reserve at the cell membrane by receptor internalization (Fig. 8d, e). Strikingly, these differences are ameliorated when the receptors are stimulated with G34-NPY that is less potent in inducing internalization of the wild-type receptor, corroborating our hypothesis (Fig. 8d, e, bottom; Table 3).

Fig. 8.

An internalization deficient Y1R variant (Y1-NC) shows enhanced G protein signaling. a Y1-NC is expressed similar to the wild-type receptor under the conditions used for signal transduction studies (d, e). b This receptor variant does not recruit arr-3 and internalize following NPY stimulation. Arr3-mCherry is depicted in red, the receptor-eYFP fusion protein in yellow, cell nuclei stained with Hoechst33342 and depicted in blue; bar equals 10 μm. c Ligand affinities at the Y1 -NC were determined in competition binding experiments using 125I-PYY (75 pM) and membrane preparations of transiently transfected HEK293 cells. d, e Kinetic analysis of cellular inositol phosphates produced downstream of the Y1R variants. d displays the concentration response curves after 15, 30 and 60 min of stimulation, which is re-plotted on a time-axis in e. f Saturation BRET experiments of Y1-NC-RLuc8 with different concentrations of Gαo-Venus in transiently transfected HEK293 cells. As seen for the wild-type receptor, there is a saturable BRET signal in the basal state indicative of pre-assembly. g Kinetic BRET experiments of the same constructs at saturating F/L ratio (F/L > 0.02) to resolve ligand effects on Y1-NC-Gαo interactions. The BRET signal prior to stimulation was recorded for 2 min and the baseline was set to 0. Compared to the wild-type receptor, the BRET increase was substantially prolonged for both, the native NPY and the G protein-biased G34-NPY after addition of ligand (+). b, g display representative examples of three independent experiments; a, c, d, e, f display mean ± SEM of three independent experiments conducted in technical triplicate

Table 3.

Functional characterization of the Y1-NC-eYFP variant

| at Y1-NC | Binding | GαqΔ6i4myr | Gi/o | arr-3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peptide | Ki (nM) (pKi ± SEM) | EC50 (nM) (pEC50 ± SEM) | EC50 (nM) (pEC50 ± SEM) | EC50 (nM) (pEC50 ± SEM) |

| NPY | 0.2 (9.65 ± 0.04) | 0.1 (9.95 ± 0.06) | 0.04 (10.37 ± 0.16) | n.d |

| G34-NPY | 6.6 (8.18 ± 0.1) | 4.3 (8.37 ± 0.09) | 0.3 (9.60 ± 0.20) | n.d |

| F7,P34-NPY | 0.2 (9.70 ± 0.11) | 0.1 (10.09 ± 0.07) | 0.02 (10.66 ± 0.08) | / |

| K18-PEG20K-F7,P34-NPY | 2.5 (8.60 ± 0.07) | 0.6 (9.19 ± 0.09) | 0.3 (9.49 ± 0.16) | / |

Binding affinities were measured by competition of 75 pM 125I-PYY at membrane preparations of transiently transfected HEK293 cells, and the Ki was fit incorporating the Cheng-Prusoff-correction with a Kd of 220 ± 60 pM determined under the same experimental conditions. Functional data were obtained in transiently transfected HEK293 cells: G protein activation was determined downstream of a chimeric GαqΔ6i4myr by accumulation of inositol phosphates, and downstream of the native Gi/o proteins using a CRE-reporter gene system, respectively. All peptides elicit the full response relative to NPY. Arr-3 recruitment was measured by BRET to an RLuc8-Arr3 fusion protein. Functional data (Ki/EC50) represent global fit of n ≥ 3 independent experiments performed in technical triplicate. n.d., not detectable up to 10 μM peptide concentration. /, not tested

Finally, we also performed BRET analyses between Y1-NC fused to RLuc8 and Gαo-Venus to endorse a prolonged recruitment phase at the plasma membrane in response to ligand stimulation. First, saturation BRET experiments confirmed pre-assembly of the receptor-G protein complex also for the Y1-NC (Fig. 8f), although the raw BRET values were lower compared to the wild type due to changes in donor/acceptor orientation caused by the mutations. As expected, in kinetic experiments (Fig. 8g) we found a prolonged recruitment phase for up to 10 min. Moreover, there was virtually no apparent dissociation until 20 min after stimulation, corroborating re-association of novel G protein heterotrimer to the receptors residing in the plasma-membrane, while only a minimal fraction of receptors became inavailable for G protein re-association.

Discussion

The concept of functional selectivity or biased agonism has gained a lot of interest within the past years. The possibility to regulate the signaling pattern of a receptor by a specific ligand is an elegant method to favour distinct signaling pathways and thus to improve the therapeutical targeting of GPCRs for pathophysiological processes. Hereby, the link between the biased agonist and specific active receptor conformations was already shown for different GPCRs such as the β2 adrenergic receptor [42, 43], the arginine-vasopressin type 2 receptor [44] or the angiotensin type 1 receptor [45]. Moreover, also the cellular system and spatiotemporal regulation can affect signaling bias and induce distinct signaling ‘waves’ [46, 47]. While G protein signaling was long assumed to occur from the plasma membrane only, Gs signaling from endosomes has been shown recently [46, 48]. Additionally, GPCRs may also form ‘megaplexes’ or’supercomplexes’ in vitro [49] and in vivo [29, 49] by simultaneously interacting with Gα subunits and tail-engaged arrestin, possibly adding unique signaling properties to the system.

Also for the Y1R, activation of different signaling pathways such as inhibitory G proteins or arrestin recruitment is seen after stimulation with its endogenous and balanced agonist NPY [29, 30, 50]. Based on the involvement of the Y1R in various physiological and pathophysiological processes, the design of peptide drugs targeting the Y1R is a promising research field. In this regard, the recent structure of the Y1R bound to a non-peptidic antagonist and a model for the NPY-Y1R complex derived from a large and complementary set of experimental data [21] may build a structural framework for targeted ligand design in the future. Interestingly, the C-terminus of the peptide, which is of utmost importance for its activity, displays a turn-like structure from residues R33 to Y36. The turn is centered around Q34, and the side chain is not involved in major receptor interactions (Fig. 1). This is in contrast to the conformation of NPY bound to the Y2R [24]. This positioning explains the tolerance of the exchange of Q34 for example to P34, which is the basis for the widely used Y1R-preferring agonist F7,P34-NPY [37]. In addition, a short NPY-derived Y1R-agonist [Pro30, Nle31,Bpa32,Leu34]NPY(28–36) has been described [51], and later studies identified derivatives of this lead structure that were full agonists for the G protein pathway but failed to induce Y1R internalization [52], indicating that signaling bias might occur at the Y1R.

Here, we aimed at identifying and characterizing functionally selective agonists at the Y1R. Further exploring ligand position 34, we identified G34-NPY as a highly specific Y1R agonist with very little residual activity at the Y2R, Y4R and Y5R. This novel ligand displayed a slightly decreased receptor affinity and capability to activate the G protein pathway. However, recruitment of arr-3 and receptor internalization were compromised to a much larger degree, resulting in a onefold net bias towards the G protein pathway. Interestingly, the well-known Y1R-preferring agonist F7,P34-NPY is just as efficient as the native ligand NPY in recruiting arr-3, despite having a higher affinity towards the receptor. This underlines that the potency to recruit arr-3 does not simply scale with ligand affinity, but involves specific and distinct receptor conformations. We complemented the set of ligands by synthesizing a F7,P34-NPY variant bearing a large polyethylene glycol moiety attached to the helical part of the peptide. In contrast to the parent peptide F7,P34-NPY, the PEGylated variant displayed excellent selectivity for the Y1R, also against the Y4R and Y5R subtypes, indicating that the modification and/or large hydration shell around the PEG20k unit is not tolerated at these receptors. Peptide modifications with PEG were originally introduced to overcome some limitations of peptide therapeutics such as the short half-life time within the body due to fast degradation or renal clearance [53] and later has been suggested as a general strategy to induce bias towards the G protein pathway and reduce arrestin recruitment and receptor internalization due to the large hydration shell [26]. Consistent with this hypothesis, this peptide also displayed a significant onefold bias towards the G protein pathway. As for G34-NPY, this net bias originated from a tenfold reduced potency to recruit arrestin while G protein activation was only slightly reduced compared to NPY. Thus, all ligands displayed some net bias towards the canonical G protein pathway, which was not caused by an increased potency towards G protein activation but by losing potency to recruit arrestin. This went along with delayed receptor internalization (Fig. 3), suggesting that not only preferred coupling to G proteins (in terms of conformational selection) but also altered spatiotemporal properties might importantly contribute to the observed bias.

We probed this hypothesis, and investigated the receptor-G protein interaction in more detail by BRET. Interestingly, we found robust and saturable pre-assembly already in the absence of ligand as recently described for the Y2R [25]. Upon stimulation with the native and balanced agonist NPY, the BRET ratio was first increased, interpreted as additional recruitment of G protein, followed by a second phase with decreasing BRET ratio reflecting the dissociation of the complex after nucleotide exchange, which is partly compensated by re-association of G protein (Gα(GDP)βγ) to available receptors at the plasma membrane, as supported by agonist washout-experiments and the dependency of the apparent rate constant of dissociation from the Gα-expression level. However, there is no re-association of G protein to internalized receptors residing in endosomes, leading to a net decrease of receptor-G protein complexes (Fig. 6). Pre-assembly and dissociation were apparently most pronounced for the native Gαi1 and Gαo. This may be explained not only by an improved geometry of the BRET pair for the energy transfer, but also by the slightly different cellular distribution of the chimeric GαqΔ6i4myr, which is only partially targeted to the plasma membrane [25]. Nonetheless, the general mechanism after NPY stimulation was preserved in all instances. Stimulation with the G protein-biased ligands G34-NPY and K18-PEG20K-F7,P34-NPY, however, changed this pattern, and delayed the dissociation phase significantly, even at very high concentration of 100 nM or 1 µM.

Moreover, the kinetics of supercomplex formation of the Y1R was altered for these ligands as demonstrated in kinetic BRET experiments (Fig. 4). Recently, we showed that the Y1R is able to form a supercomplex with G0 protein and arr-3 bound simultaneously in endosomes [29]. While NPY and F7,P34-NPY are able to induce this supercomplex formation quickly and already at low concentration, the peptides K18-PEG20K-F7,P34-NPY and G34-NPY showed slowed and decreased supercomplex formation at 100 nM concentration. The BRET signal was recovered with increasing concentration of the peptides, indicating that properties of the receptor decide whether supercomplex formation is possible. The amount of supercomplex formation, however, is apparently determined by the ability of the ligands to recruit arr-3.

Based on our data, we suggest the following mechanism (Fig. 9): Y1R and their cognate inhibitory G proteins are pre-assembled to an appreciable extent at the plasma membrane. Upon ligand stimulation, even more G protein is recruited to the receptors. After nucleotide exchange (G protein activation) the G protein subunits dissociate from the receptor. In the early phase, a large number of activated receptors is present at the plasma membrane, leading to a strong initial recruitment, and even additional rounds of G proteins that can be recruited from the membrane bound state. However, arr-3 recruitment and internalization quickly reduce the available receptors at the surface. At least in part, the Y1R, arr-3 (bound in tail conformation [29]) and G(α) protein remain bound in a ‘supercomplex’ in endosomes.

Fig. 9.

Scheme of the proposed mechanism of productive G protein signaling. The Y1R has a high basal affinity to inhibitory G proteins and G protein/receptor complexes are pre-assembled. Receptor activation leads to G protein activation, dissociation of activated Gα(GTP) and βγ-subunits and recruitment of a novel G protein heterotrimer (GDP-bound). Thus, as long as the Y1R is located at the cell membrane, productive G protein signaling occurs. After arr-3 recruitment, supercomplex formation and receptor internalization, the recruitment of new G protein is hindered and a net dissociation of G protein can be measured. Ligands or receptor mutants with reduced arr-3 interaction and internalization thus have a prolonged signaling phase

G protein-biased ligands of the Y1R do not change this cascade in principle. However, by reducing the arr-3 recruitment, the effective interactions with the G protein at the cellular membrane are prolonged by further rounds of G protein association, leading to a (relative) G protein bias. Endosomally bound G protein does not contribute significantly to G protein signaling; thus, internalization of the Y1R leads to a ‘classic’ desensitization of the receptor with respect to the G protein pathway. This contrasts the recent findings for several Gs-coupled receptors that G protein signaling can occur from endosomes reviewed in [46, 48], underlining that subcellular location of G protein signaling is distinctly regulated for individual receptors.

This mechanism was further corroborated by second messenger data of the wild-type receptor versus an internalization-deficient variant (Y1-NC) [29, 30]. Consistent with our model, we found a prolonged membrane localization with decreased net dissociation of the Y1-NC variant, which led to an increased IP accumulation and an apparently increased affinity/potency due to the preservation of the receptor reserve over time.

In the endogenous cellular context, the receptor number will become the limiting factor, in particular given that Gi/o proteins are highly abundant [54] and arr-3 is also present ubiquitously [55]. Thus, G protein-biased agonists which induce limited receptor internalization are particularly valuable in the endogenous context when aiming at efficient receptor activation. The observed bias might become even more distinct with reduced receptor number or increasing stimulation time, even if the receptor is (partly) recycled to the cell membrane. This is corroborated by the Gi/o activation in the Y1R-expressing neuroepithelioma SK-N-MC cell line (Fig. 3b). There was no detectable difference in the cAMP signal between NPY and the nominally less affine G protein-biased agonists. This underlines that the G protein bias also translates into this endogenous situation, and leads to a relative increase of G protein-mediated signaling over time, which is very useful for therapeutic purposes.

Conclusion

Here, we describe novel G protein-biased agonists at the human neuropeptide Y1 receptor. We synthesized the peptides F7,P34-NPY, K18-PEG20K-F7,P34-NPY and G34-NPY and characterized their signaling at the Y1R. We suggest that the observed bias towards the G protein pathway is system-related where a reduced arr-3 recruitment enables prolonged G protein signaling at the plasma membrane, while the signaling of balanced agonists is quickly terminated by receptor internalization to endosomes. Thus, G protein-biased ligands might be very valuable for therapeutic targeting in the endogenous context. Still, also for biased ligands, arr-3 recruitment occurs at high ligand concentrations and a supercomplex may be formed. The specific role of that complex in cellular signaling needs to be further elucidated.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Prof. Dr. D. Huster for fruitful discussions on the binding mode and conformational freedom of NPY when bound to its receptors, which further motivated exploration of ligand position 34. Moreover, they would like to thank Dr. K. Bellmann-Sickert for help with synthesis of the PEGylated peptide. The authors gratefully acknowledge the expert technical assistance of C. Dammann, K. Löbner, R. Müller, R. Reppich-Sacher and J. Schwesinger.

Funding

This work was supported by the German Science Foundation project number 209933838, SFB1052 TP A3 to A. G. B.-S., project number 421152132, SFB 1423 TP B1 to A. G. B.-S. and B3 to A. K., the European Union, the Federal State of Saxony (SMWK, grant 100316655 to A.K.) and the “European Regional Development Fund”.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Anette Kaiser and Lizzy Wanka contributed equally.

References

- 1.Leff P. The two-state model of receptor activation. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1995;16:89–97. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)88989-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith JS, Lefkowitz RJ, Rajagopal S. Biased signalling: from simple switches to allosteric microprocessors. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2018;17:243–260. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vaidehi N, Kenakin T. The role of conformational ensembles of seven transmembrane receptors in functional selectivity. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2010;10:775–781. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Violin JD, DeWire SM, Yamashita D, Rominger DH, Nguyen L, Schiller K, Whalen EJ, Gowen M, Lark MW. Selectively engaging β-arrestins at the angiotensin II type 1 receptor reduces blood pressure and increases cardiac performance. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;335:572–579. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.173005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cotter G, Davison BA, Butler J, Collins SP, Ezekowitz JA, Felker GM, Filippatos G, Levy PD, Metra M, Ponikowski P, Teerlink JR, Voors AA, Senger S, Bharucha D, Goin K, Soergel DG, Pang PS. Relationship between baseline systolic blood pressure and long-term outcomes in acute heart failure patients treated with TRV027: an exploratory subgroup analysis of BLAST-AHF. Clin Res Cardiol Off J Ger Card Soc. 2018;107:170–181. doi: 10.1007/s00392-017-1168-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pang PS, Butler J, Collins SP, Cotter G, Davison BA, Ezekowitz JA, Filippatos G, Levy PD, Metra M, Ponikowski P, Teerlink JR, Voors AA, Bharucha D, Goin K, Soergel DG, Felker GM. Biased ligand of the angiotensin II type 1 receptor in patients with acute heart failure: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase IIB, dose ranging trial (BLAST-AHF) Eur Heart J. 2017;38:2364–2373. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li T, Jiang S, Ni B, Cui Q, Liu Q, Zhao H. Discontinued drugs for the treatment of cardiovascular disease from 2016 to 2018. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:4513. doi: 10.3390/ijms20184513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Michel MC, Beck-Sickinger A, Cox H, Doods HN, Herzog H, Larhammar D, Quirion R, Schwartz T, Westfall T. XVI. International Union of Pharmacology recommendations for the nomenclature of neuropeptide Y, peptide YY, and pancreatic polypeptide receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 1998;50:143–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tatemoto K, Carlquist M, Mutt V. Neuropeptide Y—a novel brain peptide with structural similarities to peptide YY and pancreatic polypeptide. Nature. 1982;296:659–660. doi: 10.1038/296659a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murphy KG, Bloom SR. Gut hormones and the regulation of energy homeostasis. Nature. 2006;444:854–859. doi: 10.1038/nature05484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yulyaningsih E, Zhang L, Herzog H, Sainsbury A. NPY receptors as potential targets for anti-obesity drug development: anti-obesity drug development. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;163:1170–1202. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01363.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bard JA, Walker MW, Branchek TA, Weinshank RL. Cloning and functional expression of a human Y4 subtype receptor for pancreatic polypeptide, neuropeptide Y, and peptide YY. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:26762–26765. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.26762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reubi JC, Gugger M, Waser B, Schaer JC. Y(1)-mediated effect of neuropeptide Y in cancer: breast carcinomas as targets. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4636–4641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruscica M, Dozio E, Boghossian S, Bovo G, Martos Riaño V, Motta M, Magni P. Activation of the Y1 receptor by neuropeptide Y regulates the growth of prostate cancer cells. Endocrinology. 2006;147:1466–1473. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Korner M. High expression of neuropeptide Y receptors in tumors of the human adrenal gland and extra-adrenal paraganglia. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:8426–8433. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Antal-Zimanyi I, Bruce MA, LeBoulluec KL, Iben LG, Mattson GK, McGovern RT, Hogan JB, Leahy CL, Flowers SC, Stanley JA, Ortiz AA, Poindexter GS. Pharmacological characterization and appetite suppressive properties of BMS-193885, a novel and selective neuropeptide Y1 receptor antagonist. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;590:224–232. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keller M, Pop N, Hutzler C, Beck-Sickinger AG, Bernhardt G, Buschauer A. Guanidine−acylguanidine bioisosteric approach in the design of radioligands: synthesis of a tritium-labeled N G-propionylargininamide ([3 H]-UR-MK114) as a highly potent and selective neuropeptide Y Y1 receptor antagonist. J Med Chem. 2008;51:8168–8172. doi: 10.1021/jm801018u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keller M, Weiss S, Hutzler C, Kuhn KK, Mollereau C, Dukorn S, Schindler L, Bernhardt G, König B, Buschauer A. N ω -carbamoylation of the argininamide moiety: an avenue to insurmountable NPY Y1 receptor antagonists and a radiolabeled selective high-affinity molecular tool ([3 H]UR-MK299) with extended residence time. J Med Chem. 2015;58:8834–8849. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rudolf K, Eberlein W, Engel W, Wieland HA, Willim KD, Entzeroth M, Wienen W, Beck-Sickinger AG, Doods HN. The first highly potent and selective non-peptide neuropeptide Y Y1 receptor antagonist: BIBP3226. Eur J Pharmacol. 1994;271:R11–R13. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)90822-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wieland HA, Engel W, Eberlein W, Rudolf K, Doods HN. Subtype selectivity of the novel nonpeptide neuropeptide Y Y1 receptor antagonist BIBO 3304 and its effect on feeding in rodents. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;125:549–555. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang Z, Han S, Keller M, Kaiser A, Bender BJ, Bosse M, Burkert K, Kögler LM, Wifling D, Bernhardt G, Plank N, Littmann T, Schmidt P, Yi C, Li B, Ye S, Zhang R, Xu B, Larhammar D, Stevens RC, Huster D, Meiler J, Zhao Q, Beck-Sickinger AG, Buschauer A, Wu B. Structural basis of ligand binding modes at the neuropeptide Y Y1 receptor. Nature. 2018;556:520–524. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0046-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Babilon S, Mörl K, Beck-Sickinger AG. Towards improved receptor targeting: anterograde transport, internalization and postendocytic trafficking of neuropeptide Y receptors. Biol Chem. 2013;394:921–936. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2013-0123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luttrell LM, Ferguson SSG, Daaka Y, Miller WE, Maudsley S, Della Rocca GJ, Lin F-T, Kawakatsu H, Owada K, Luttrell DK, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ. β-arrestin-dependent formation of β2 adrenergic receptor-Src protein kinase complexes. Science. 1999;283:655–661. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5402.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaiser A, Müller P, Zellmann T, Scheidt HA, Thomas L, Bosse M, Meier R, Meiler J, Huster D, Beck-Sickinger AG, Schmidt P. Unwinding of the C-terminal residues of neuropeptide Y is critical for Y2 receptor binding and activation. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2015;54:7446–7449. doi: 10.1002/anie.201411688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaiser A, Hempel C, Wanka L, Schubert M, Hamm HE, Beck-Sickinger AG. G protein preassembly rescues efficacy of W6.48 toggle mutations in neuropeptide Y2 receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2018;93:387–401. doi: 10.1124/mol.117.110544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mäde V, Babilon S, Jolly N, Wanka L, Bellmann-Sickert K, Diaz Gimenez LE, Mörl K, Cox HM, Gurevich VV, Beck-Sickinger AG. Peptide modifications differentially alter G protein-coupled receptor internalization and signaling bias. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53:10067–10071. doi: 10.1002/anie.201403750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dinger MC, Bader JE, Kobor AD, Kretzschmar AK, Beck-Sickinger AG. Homodimerization of neuropeptide Y receptors investigated by fluorescence resonance energy transfer in living cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:10562–10571. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205747200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gimenez LE, Babilon S, Wanka L, Beck-Sickinger AG, Gurevich VV. Mutations in arrestin-3 differentially affect binding to neuropeptide Y receptor subtypes. Cell Signal. 2014;26:1523–1531. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2014.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wanka L, Babilon S, Kaiser A, Mörl K, Beck-Sickinger AG. Different mode of arrestin-3 binding at the human Y1 and Y2 receptor. Cell Signal. 2018;50:58–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2018.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kilpatrick L, Briddon S, Hill S, Holliday N. Quantitative analysis of neuropeptide Y receptor association with β-arrestin2 measured by bimolecular fluorescence complementation: BiFC measures NPY receptor-β-arrestin interaction. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:892–906. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00676.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vishnivetskiy SA, Gimenez LE, Francis DJ, Hanson SM, Hubbell WL, Klug CS, Gurevich VV. Few residues within an extensive binding interface drive receptor interaction and determine the specificity of arrestin proteins. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:24288–24299. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.213835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kostenis E. Potentiation of GPCR-signaling via membrane targeting of G protein alpha subunits. J Recept Signal Transduct. 2002;22:267–281. doi: 10.1081/rrs-120014601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wahlestedt C, Grundemar L, Håkanson R, Heilig M, Shen GH, Zukowska-Grojec Z, Reis DJ. Neuropeptide Y receptor subtypes, Y1 and Y2. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1990;611:7–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb48918.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gordon EA, Kohout TA, Fishman PH. Characterization of functional neuropeptide Y receptors in a human neuroblastoma cell line. J Neurochem. 1990;55:506–513. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb04164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gregory KJ, Sexton PM, Tobin AB, Christopoulos A. Stimulus bias provides evidence for conformational constraints in the structure of a G protein-coupled receptor. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:37066–37077. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.408534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kenakin T, Watson C, Muniz-Medina V, Christopoulos A, Novick S. A simple method for quantifying functional selectivity and agonist bias. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2012;3:193–203. doi: 10.1021/cn200111m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Söll RM, Dinger MC, Lundell I, Larhammer D, Beck-Sickinger AG. Novel analogues of neuropeptide Y with a preference for the Y1 -receptor: Novel NPY analogues with Y1 -receptor preference. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:2828–2837. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ahrens VM, Frank R, Boehnke S, Schütz CL, Hampel G, Iffland DS, Bings NH, Hey-Hawkins E, Beck-Sickinger AG. Receptor-mediated uptake of boron-rich neuropeptide Y analogues for boron neutron capture therapy. ChemMedChem. 2015;10:164–172. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201402368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ahrens VM, Frank R, Stadlbauer S, Beck-Sickinger AG, Hey-Hawkins E. Incorporation of ortho-carbaboranyl-Nε-modified l-lysine into neuropeptide Y receptor Y1- and Y2-selective analogues. J Med Chem. 2011;54:2368–2377. doi: 10.1021/jm101514m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schubert M, Stichel J, Du Y, Tough IR, Sliwoski G, Meiler J, Cox HM, Weaver CD, Beck-Sickinger AG. Identification and characterization of the first selective Y4 receptor positive allosteric modulator. J Med Chem. 2017;60:7605–7612. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b00976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shebanits K, Vasile S, Xu B, Gutiérrez-de-Terán H, Larhammar D. Functional characterization in vitro of twelve naturally occurring variants of the human pancreatic polypeptide receptor NPY4R. Neuropeptides. 2019;76:101933. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2019.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kahsai AW, Xiao K, Rajagopal S, Ahn S, Shukla AK, Sun J, Oas TG, Lefkowitz RJ. Multiple ligand-specific conformations of the β2-adrenergic receptor. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:692–700. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu JJ, Horst R, Katritch V, Stevens RC, Wuthrich K. Biased signaling pathways in 2-adrenergic receptor characterized by 19F-NMR. Science. 2012;335:1106–1110. doi: 10.1126/science.1215802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rahmeh R, Damian M, Cottet M, Orcel H, Mendre C, Durroux T, Sharma KS, Durand G, Pucci B, Trinquet E, Zwier JM, Deupi X, Bron P, Baneres J-L, Mouillac B, Granier S. Structural insights into biased G protein-coupled receptor signaling revealed by fluorescence spectroscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109:6733–6738. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201093109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wingler LM, Elgeti M, Hilger D, Latorraca NR, Lerch MT, Staus DP, Dror RO, Kobilka BK, Hubbell WL, Lefkowitz RJ. Angiotensin analogs with divergent bias stabilize distinct receptor conformations. Cell. 2019;176:468–478.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eichel K, von Zastrow M. Subcellular organization of GPCR signaling. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2018;39:200–208. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2017.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grundmann M, Kostenis E. Temporal bias: time-encoded dynamic GPCR signaling. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2017;38:1110–1124. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2017.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thomsen ARB, Jensen DD, Hicks GA, Bunnett NW. Therapeutic targeting of endosomal G-protein-coupled receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2018;39:879–891. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2018.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thomsen ARB, Plouffe B, Cahill TJ, Shukla AK, Tarrasch JT, Dosey AM, Kahsai AW, Strachan RT, Pani B, Mahoney JP, Huang L, Breton B, Heydenreich FM, Sunahara RK, Skiniotis G, Bouvier M, Lefkowitz RJ. GPCR-G protein-β-Arrestin super-complex mediates sustained G protein signaling. Cell. 2016;166:907–919. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Böhme I, Stichel J, Walther C, Mörl K, Beck-Sickinger AG. Agonist induced receptor internalization of neuropeptide Y receptor subtypes depends on third intracellular loop and C-terminus. Cell Signal. 2008;20:1740–1749. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2008.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zwanziger D, Böhme I, Lindner D, Beck-Sickinger AG. First selective agonist of the neuropeptide Y1 -receptor with reduced size. J Pept Sci. 2009;15:856–866. doi: 10.1002/psc.1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hofmann S, Frank R, Hey-Hawkins E, Beck-Sickinger AG, Schmidt P. Manipulating Y receptor subtype activation of short neuropeptide Y analogs by introducing carbaboranes. Neuropeptides. 2013;47:59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fosgerau K, Hoffmann T. Peptide therapeutics: current status and future directions. Drug Discov Today. 2015;20:122–128. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jiang M, Bajpayee NS. Molecular mechanisms of Go signaling. Neurosignals. 2009;17:23–41. doi: 10.1159/000186688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gurevich EV, Gurevich VV. Arrestins: ubiquitous regulators of cellular signaling pathways. Genome Biol. 2006;7:236. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-9-236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]