Abstract

The Voltage-Dependent Anion-selective Channel (VDAC) is the pore-forming protein of mitochondrial outer membrane, allowing metabolites and ions exchanges. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, inactivation of POR1, encoding VDAC1, produces defective growth in the presence of non-fermentable carbon source. Here, we characterized the whole-genome expression pattern of a VDAC1-null strain (Δpor1) by microarray analysis, discovering that the expression of mitochondrial genes was completely abolished, as consequence of the dramatic reduction of mtDNA. To overcome organelle dysfunction, Δpor1 cells do not activate the rescue signaling retrograde response, as ρ0 cells, and rather carry out complete metabolic rewiring. The TCA cycle works in a “branched” fashion, shunting intermediates towards mitochondrial pyruvate generation via malic enzyme, and the glycolysis-derived pyruvate is pushed towards cytosolic utilization by PDH bypass rather than the canonical mitochondrial uptake. Overall, Δpor1 cells enhance phospholipid biosynthesis, accumulate lipid droplets, increase vacuoles and cell size, overproduce and excrete inositol. Such unexpected re-arrangement of whole metabolism suggests a regulatory role of VDAC1 in cell bioenergetics.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00018-019-03342-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Warburg effect, Inositol, Fatty acids, Porin, Retrograde signaling, PDH bypass, Mitochondrial DNA

Introduction

Inactivation of genes in yeast provides important information about the function of individual genes. It has been extensively used to understand the pathways in which genes are involved and, in the end, it can be a useful tool to study heterologous proteins of similar function upon ectopic expression. The pivotal location of VDAC (Voltage Dependent Anion-selective Channel) in the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM), where it is the molecular interface between cytosolic molecules and metabolism and the organelle functions, made this protein a preferred target for such a genetic-molecular strategy in yeast, where the gene coding for VDAC was called POR1, as a tribute to bacterial porins, formerly considered close relatives. VDACs are a small family of pore-forming proteins, ubiquitously present in eukaryotes, 280–290 amino acid residues long, with high sequence homology and undistinguishable pore-forming properties among them [1, 2]. The primary function of VDAC proteins is to allow the traffic of small hydrophilic metabolites and ions through the OMM, a function supported by its structure, solved as a transmembrane barrel made of amphipathic β-strands [3–6]. In higher eukaryotes, VDAC proteins have been involved in many other cellular processes or biochemical interactions [7–10]. Recently, it was robustly asserted that, in yeast, VDAC1 is also a coupling factor for protein translocation into the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM), in particular for the group of inner membrane metabolite carriers [11].

In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, POR1 inactivation has been obtained a few years after the isolation of the cDNA and the gene itself, with the aim to establish the role of VDAC1 in cell metabolism regulation. The mutant obtained, por1Δ or Δpor1 (as it was informally called), grew normally in glucose but not on the non-fermentable carbon source (i.e., glycerol) even though it could slowly adapt to this substrate [12]. Anyway, the unforeseen result that POR1 deletion was not lethal in yeast raised the quest for other channel-forming proteins in the mitochondrion. At that time, however, no protein was discovered despite the conductance in artificial membranes produced by a detergent extract of Δpor1 OMM claimed for the presence of a smaller pore [13]. Afterward, Blachly-Dyson and colleagues discovered the second yeast VDAC isoform [14]. VDAC2 protein has been recently characterized [15, 16] and despite it shows similar electrophysiological activity to the main isoform, its contribution to the general permeability of the membrane does not look very relevant, since its copy number per mitochondrion is extremely low [17]. On the contrary, the abundance of VDAC1 is nowadays estimated in the astonishing number of about 16,000 copies per mitochondrion, which makes VDAC1 the most abundant membrane protein in yeast [17].

Interested in the metabolic adaptation of yeast to the lack of such an abundant and relevant protein as VDAC1 is, we performed a whole-genome transcription analysis by microarray. The most unexpected and astonishing result is that when POR1 is deleted, there is a large derangement of the mitochondrial functions, due to the depletion of its genetic material. This, surprisingly, does not result in the activation of the retrograde response, as instead expected in case of ρ0 cells, but rather it involves a complete rewiring of the entire metabolism: Δpor1 enhances bypass pathways to target the substrates usually deployed to the mitochondria and the cell experiences changes in the shape and in the organelle contents. Thus, VDAC1 is responsible for the health of mitochondria and, consequently, of its impact in the overall metabolic asset of the cell. Interestingly, the changes in the metabolism of this mutant strain largely overlap the modifications happening in cancer cells and known as Warburg effect.

Materials and methods

Yeast strains and growth conditions

The Δpor1 mutant (por1::KanMX4) was a derivative of BY4742 (MATα, his3Δ1, leu2Δ0, lys2Δ0, ura3Δ0), both from EUROSCARF (www.euroscarf.de). Ino− strains used were ire1Δ (ire1::KanMX4) and hac1Δ (hac1::KanMX4) both derivatives of BY4741 (EUROSCARF). Cells were grown in batches at 28 °C in minimal medium (Yeast Nitrogen Base without amino acids, 6.7 g/L, Difco) with 2% w/v glucose and the required supplements added in excess as previously described [18, 19]. Where indicated, L-carnitine (Sigma-Aldrich) was supplemented to a concentration of 10 mg/ml. Duplication time (Td) was obtained by linear regression of the cell number increase over time on a semi-logarithmic plot. Yeast growth was assayed on YP plates (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% agar) supplemented with 2% glucose, glycerol, ethanol, succinate, acetate or citrate by plating drop-serial dilution starting from 106 cells. Plates were incubated at 28 °C from 1 to 2 days.

Microarray

Total RNA was extracted from cells grown up to log phase (OD600 0.4) using PureLink RNA Mini Kit (Life Technologies) according to manufacturer instruction. RNA integrity was confirmed by automated electrophoresis using 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies). Gene expression profiles were investigated by Yeast (V2) Gene Expression 8 × 15 K Microarray (Agilent Technologies), according to the One-Color Microarray-Based Gene Expression Analysis kit protocol (Version 6.9.1). Raw signal values were thresholded to 1, log2 transformed, normalized to the 75th percentile and baselined to the median of all samples using GeneSpringGX v.14.9 (Agilent Technologies). To assess the statistical significance of gene expression changes, statistical analysis was performed using GeneSpring GX software package (version 14.9; Agilent Technologies), using a moderate t test. Differentially expressed genes with a P value ≤ 0.05 were deemed as significant. Genes with deregulated expression changes (probes with a GeneID and a Moderated-t test P value < 0.05) were screened for Gene Ontology (GO) biological process enrichment analysis (where Fisher’s Exact with the Bonferroni multiple test correction P < 0.005, was applied) using the specialized GO Ontology Consortium database (www.geneontology.org).

Real-Time PCR

To confirm microarray data, Real-Time PCR was performed on the following subset of genes: ADH1, ALD4, CIT1, CYC1, CYT1, HAP4, MDH1 and PDC1. ACT1 was used as internal control for normalization. cDNAs were synthesized using the QuantiTec Reverse Transcription Kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacture’s protocol. For mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) quantification, Real-Time PCR was performed on total DNA by analyzing the COX3 locus [20]. For each experiment, three independent Real-Time PCR runs were performed in triplicate using the QuantiTec SYBR Green PCR Kit (QIAGEN). Analysis was performed in the Mastercycler ep realplex (Eppendorf) in 96-well plates. Thermocycling program consisted in a first activation at 95 °C for 15 min, followed by 40 cycles at 95 °C for 15 s, annealing at 54 °C for 15 s, extension at 68 °C for 15 s and a final step at 72 °C for 10 min. Relative quantification was performed using the comparative ΔΔCt method [21]. Data were statistically analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. All primer sequences are available upon request.

Fluorescence microscopy

MitoTraker Green FM (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used for mitochondrial visualization. Mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) was assessed by 3,3″-dihexyloxacarbocyanine iodide (DiOC6, Molecular Probes) staining [22]; cells were also counterstained with propidium iodide to discriminate between live and dead cells. Nile Red staining of lipid droplets was performed by adding to unfixed cells (2 × 107 in 500 µl PBS), 5 µl of Nile Red (Sigma-Aldrich) solution (1 mg/ml stock solution in DMSO). After 5 min at room temperature in the dark, cells were washed twice with PBS before fluorescent microscopic analysis. Vacuoles were stained with 5(6)-carboxy-2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (carboxy-DCFDA, Molecular Probes) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) were detected with dihydroethidium (DHE, Sigma-Aldrich) as previously described [18]. A Nikon Eclipse E600 fluorescence microscope equipped with a Nikon Digital Sight DS Qi1 camera was used. Digital images were acquired and processed using Nikon software NIS-Elements.

Flow cytometry

For mitochondrial mass determination, yeast cultures were treated with 5-μM MitoTracker Green FM (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 30 min under constant shaking at 28 °C. Intracellular total ROS content was instead measured using the fluorescent probe dihydrorhodamine 123 (DHR 123, Sigma-Aldrich). Yeast samples were grown up to the exponential phase, then treated for 2 h with DHR 123 (5 μg/mL of culture), under constant shaking at 30 °C. Cells were washed twice and analyzed by CyFlow ML flow cytometer (SysmexPartec, Görlitz, Germany). 50,000 cells per sample were analyzed; data obtained were acquired, gated, compensated, and analyzed using the FlowMax software accordingly with previous report [23]. Experiments were repeated at least twice in triplicate. Data were statistically analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test.

Estimation of oxygen consumption rates and cytochrome spectra

The basal oxygen consumption of intact cells was measured using a “Clark-type” oxygen electrode (Oxygraph System, Hansatech Instruments) [24]. The maximal/uncoupled respiratory capacity was measured in the presence of 10 µM of the uncoupler carbonyl cyanide 3-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP, Sigma-Aldrich) [25]. Respiratory rates for the basal oxygen consumption (JR) and the maximal/uncoupled oxygen consumption (JMAX) were determined from the slope of a plot of O2 concentration against time, divided by the cellular concentration. Mitochondria prepared as previously described [26] were resuspended at a final protein concentration of 10 mg/ml in 10 mM Tris-maleate, pH 6.8, 0.6 M Mannitol, 2 mM EGTA. Then, the mitochondrial suspension was equally divided: one sample was reduced with sodium dithionite and the other oxidized with potassium ferricyanide. Redox difference spectra were recorded from 500 to 650 nm and cytochrome contents were quantified by the OD differences [27].

Chronological life span (CLS)

Cell number was monitored during yeast growth and samples were collected at different time-points to define the growth profile (exponential phase, diauxic shift (Day 0), post-diauxic phase and stationary phase) of the culture [24]. CLS was measured according by counting colony-forming units (CFU) starting with 72 h (Day 3, first age-point) after Day 0. The number of CFU on Day 3 was considered the initial survival (100%).

Dosage of metabolites and enzymatic activities

At designated time-points, aliquots of the yeast cultures were centrifuged, and both pellets (washed twice) and supernatants were collected and frozen at − 80 °C until used. Rapid sampling for intracellular metabolite measurements was performed as previously described [24]. The concentrations of glucose, ethanol, citrate, malate, myo-inositol, pyruvate, and succinate were determined using enzymatic assays (K-HKGLU, K-ETOH, K-CITR, K-LMALR, K-INOSL, K-PYRUV and K-SUCC kits from Megazyme). Cell-free extracts were prepared as previously reported [24]; immediately after, the activity of cytosolic and mitochondrial acetaldehyde dehydrogenases (Alds) was assayed accordingly to [28], of alcohol dehydrogenases (Adhs) as detailed in [29], of pyruvate decarboxylase (Pdc1) as described in [30] and of malic enzyme as reported in [18]. The pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) activity was assayed according to [31] on fresh crude mitochondrial preparations. Protein contents were estimated using the BCATM Protein Assay Kit (Pierce).

Lipid analysis

Lipid extraction was performed as previously described on pellets (5 × 108 cells) frozen at − 80 °C [32]. Lipid films were dissolved in 500 µl of chloroform and stored at − 20 °C. Samples were separated by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) on silica gel plates with fluorescent indicator 254 nm (Sigma-Aldrich) using as developing solvent for neutral lipids, petroleum ether/diethyl ether/acetic acid (70:30:2, v/v/v) and for polar ones, chloroform/methanol/25% (w/v) ammonia solution (50:25:6, v/v/v). Visualized spots were identified using lipid standards (Sigma-Aldrich) and quantified, after scanning the plates, with the Image J free software (http://rsb.inf.nih.gov/ij/). Mitochondria fresh crude fractions were used for cardiolipin (CL) measurements. CL quantification was performed using the fluorescent dye 10-N-nonyl-acridine orange (NAO) [33]. Green fluorescence was measured at 525 nm with a Cary Eclipse fluorescence spectrophotometer (Varian) and correlated with a calibration curve of NAO (0–5 µM) in ethanol.

Plate assays

To determine soraphen A (SorA) sensitivity, exponentially growing cells were spotted (5 µl from a concentrated suspension of 108 or 107 cells/ml and from serial tenfold dilutions) onto glucose medium plates supplemented with 1 µg/ml SorA. Plates were incubated at 28 °C for 2 days. Cells were also dropped onto plates without SorA to monitor cell growth. To determine overproduction and excretion of inositol (Opi− phenotype), a sensitive assay was used [34]. Briefly, WT and Δpor1 cells were spotted on minimal medium without inositol/2% glucose agar plates and incubated at 28 °C for 2 days. Then, a cell suspension of the inositol auxotrophic (Ino−) strain was sprayed on the plates, incubated for further 2 days at 28 °C and scored for halos. Indeed, Ino− strain only grows as a halo around strains excreting inositol. The same assay was also performed by dropping the Ino− cells (5 µl from a concentrated suspension of 107/ml) on the plates instead of spraying them. After 2 days at 28 °C, Ino− cells grow as spots near the strain excreting inositol. The assay was also performed on inositol-containing agar plates to monitor cell growth. Cell number and cellular volumes were determined using a Coulter Counter-Particle Count and Size Analyser [35].

Statistics

All values are presented as the mean of three independent experiments ± Standard Deviation (SD). Three technical replicates were analyzed in each independent experiment. Statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA test. The level of statistical significance was set at a P value of ≤ 0.05. In particular, * indicates a P < 0.05, ** indicates a P < 0.01, *** indicates a P < 0.001. Histograms were prepared using GraphPad Prism version 7.00 (GraphPad Software).

Results

Deletion of POR1 strongly affects OXPHOS complexes expression

According to the literature, Δpor1 mutant grows normally in glucose but hardly in the presence of any different non-fermentable carbon sources (Fig. S1). Due to the presence of such a dramatic impairment, the transcriptomic profiling of the Δpor1 mutant was performed by microarray after growth on glucose. Overall, our analysis highlighted striking differences between Δpor1 and wild-type (WT) transcripts, with almost the totality of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) found activated or inactivated in opposite way between the two strains (Fig. 1a). In particular, 3501 genes (3729 probes out of a total of 6314 probes present on the microarray) showed significant expression changes of which 1849 genes (2017 probes) were down-regulated, while 1652 genes (1712 probes) showed an up-regulated expression in Δpor1 (Fig. 1b). Quality of microarray data was validated by qPCR on a subset of genes (Fig. S2) and the complete list of DEGs, including fold change value and nomenclature, is detailed in Dataset 1 in Supplementary material. Moreover, Gene Ontology enrichment of biological pathways revealed distribution of DEGs in several biological processes (Fig. S3; Dataset 2 in Supplementary material). In accordance with the central metabolic role of VDAC1, we found DEGs associated with the main cellular metabolism and energy homeostasis pathways, including glycolysis, alcoholic fermentation, TCA cycle, oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) and lipid synthesis (Fig. 1c). Among them, however, we noticed that mitochondrial genes, including those encoding OXPHOS subunits, were completely switched off. OXPHOS complexes are embedded in the IMM where, together with cytochrome c and ubiquinone (the mobile electron carriers), produce most of ATP for eukaryotes needs. In mammals, the OXPHOS chain consists of four electron transport chain complexes (complexes I–IV) and the F1F0-ATP synthase (complex V). Unlike mammals, S. cerevisiae does not have a canonical rotenone-sensitive complex I but rather different types of NADH–ubiquinone oxidoreductases, namely Ndi1, and the isoenzymes Nde1 and Nde2 (referred herein as complex I equivalent); the last ones are distributed on the external surface of the IMM and are responsible for the transfer of electrons from NADH to ubiquinone [36]. As reported in Fig. 1d, the expressions of COB, encoding the cytochrome b and forming the catalytic core of the cytochrome bc1 complex [37], COX1, COX2 and COX3, encoding the core subunits of cytochrome c oxidase, ATP6, ATP8 and ATP9, encoding the three mitochondrial subunits of the transmembrane F0 unit of the F1F0-ATP synthase, were found reduced of about two or three orders of magnitude in comparison to the WT. In addition, a similar down-regulation was detected for other mtDNA intron-related open reading frames, encoding enzymes involved in the expression/maturation of mitochondria-encoded genes [38], i.e., AI2 and AI5alpha. Such a remarkable change of expression was not instead observed for OXPHOS subunits encoded by the nuclear genome, whose mRNA levels were found mostly unchanged or, in few cases, slightly varied (i.e., Nde1, Nde2 and F1 subunits). Overall, these results indicate that, during yeast growth on glucose, the lack of VDAC1 correlates with a general gene deregulation and a specific down-regulation of mtDNA expression. Furthermore, since OXPHOS components are codified in two spatially separate genomes (mtDNA and nuclear DNA), a coordinate expression of mitochondrial-targeted proteins of both origins is required. Notably, in the Δpor1 mutant, such a coordination does not look to be in place, since the nucleus-encoded mitochondrial proteins did not show a similar dramatic down-regulation as mitochondria-encoded ones.

Fig. 1.

Lack of POR1 promotes a general deregulation of genes involved in the main metabolic pathways. a General heat map showing differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in the two strains. b Quantification of up- and down-regulated genes in Δpor1 cells compared with WT. c Bar plots presenting biological processes associated with metabolic and energetic regulatory mechanisms significantly enriched for DEGs in Δpor1. d Microarray heat maps of the subunits of respiratory complex and accessory proteins as obtained by microarray analysis. Data are shown as fold change

Mitochondrial DNA, mass, organization and respiration are strongly affected in Δpor1 cells

To understand the consequences of this finding and the mechanism(s) involved in these different outcomes, we analyzed the overall levels of mtDNA in Δpor1 cells by qPCR of COX3 locus. The results shown in Fig. 2a revealed a reduction of mtDNA of about three orders of magnitude in comparison with the WT. However, the ectopic expression of POR1 in the mutant completely restored the mtDNA, suggesting that VDAC1 is specifically involved in the physiological mtDNA maintenance, a role possibly ascribed to the protein participation in mediating OMM permeability to nucleotides. Next, the influence of VDAC1 lack on the mitochondrial mass was investigated. The overall amount of mitochondria was assayed using MitoTraker Green, a fluorescent probe able to enter into mitochondria independently from the MMP. Fluorescence microscopy and relative flow cytometric quantification (Fig. 2b) showed a noteworthy reduction of about 65% of mitochondrial mass in the Δpor1 strain in comparison with WT. Consistently, the total content of mitochondrial proteins was significantly reduced in Δpor1 mitochondria (Fig. 2c), confirming that the lack of VDAC1 also elicits the decrease of the mitochondrial mass. In addition, we carried out cytochrome spectral analyses of mitochondria isolated from the Δpor1. Quantification of the spectra showed that the most significant effect was a marked reduction of the cytochrome c oxidase (heme aa3) content of about 50% compared with the WT (Fig. 2d and Table S1). Therefore, these results suggest that, during growth on glucose, the lack of VDAC1 negatively affects mitochondrial biogenesis, functionality and structure, a finding correlating with the impossibility to import carrier proteins, the second function that has been recently linked to VDAC1 (11). Accordingly, Δpor1 cells exhibited a respiration rate lower than the WT one (Fig. 2e). Furthermore, in the presence of the uncoupler CCCP, which allows the measurement of the maximal respiratory capacity by dissipating the proton gradient across the mitochondrial membrane, the respiration rate of Δpor1 was always lower than that of the WT (Fig. 2f). This is indicative of a depletion/limitation of reducing equivalents, in line with a reduction of MMP in the mutant previously observed [39]. Consistently, fluorescent staining with DiOC6, which accumulates at mitochondrial membranes depending on their MMP [22], revealed a very low level of fluorescence in Δpor1 cells compared with WT ones, as well as, a decrease in tubular mitochondrial morphologies (Fig. 2g). In keeping with the reduced mitochondrial functionality, Δpor1 cells also displayed a reduced growth on non-fermentable substrates [12], which requires a respiration-based metabolism. The last also occurs in a standard chronological lifespan (CLS) experimental set-up [40], when glucose becomes limiting and after the diauxic shift cells utilize the extracellular by-product of glucose fermentation, ethanol, as carbon/energy source. In Δpor1, the respiration was always lower than in WT and the extracellular ethanol decreased more slowly (Fig. S4A), indicating an impairment in ethanol utilization in line with the reduced growth on non-fermentable substrates [12]. According to the reduced mitochondrial functionality, Δpor1 showed a remarkable decrease of the CLS (Fig. S4B).

Fig. 2.

Mitochondrial DNA amount and organelle features are profoundly changed in Δpor1. a Quantification of mtDNA performed by Real-Time PCR of the COX3 locus in the indicated strains. Δpor1 + POR1 indicates Δpor1 cells expressing ectopically POR1. Data are expressed in log scale as COX3 copy number relative to the WT. b Representative microscopy pictures of mitochondria in WT and Δpor1 cells after incubation with the MitoTracker green probe (scale bar indicates 10 µm) and relative analysis of mitochondrial mass performed by flow cytometry. Data are expressed as relative fluorescence of the WT. c Quantification of total mitochondrial proteins by BCA assay extracted from WT and Δpor1 cells at different cellular densities during growth. d Quantification of cytochrome c oxidase deduced by heme aa3 spectra obtained from WT and Δpor1 cells at different cellular densities during growth. e, f Respiration parameters of the indicated strains at different cellular densities during growth; e indicates the basal respiration rate, while f indicates the uncoupled respiration rate. Substrates and inhibitors used in the measurements are detailed in the text. g Representative microscopy images showing changes in the organelles’ organization. Yeast cells in exponential phase were stained with DiOC6 to visualize mitochondrial membranes. Cells were also viewed under bright field. The right panels show an overlay of images of cellular and mitochondrial morphologies. In histograms, data are expressed as mean (SD) of n = 3 independent experiments, where ** indicates a P < 0.01 and *** indicates a P < 0.001

Δpor1 mutant shows an impoverishment of the TCA cycle

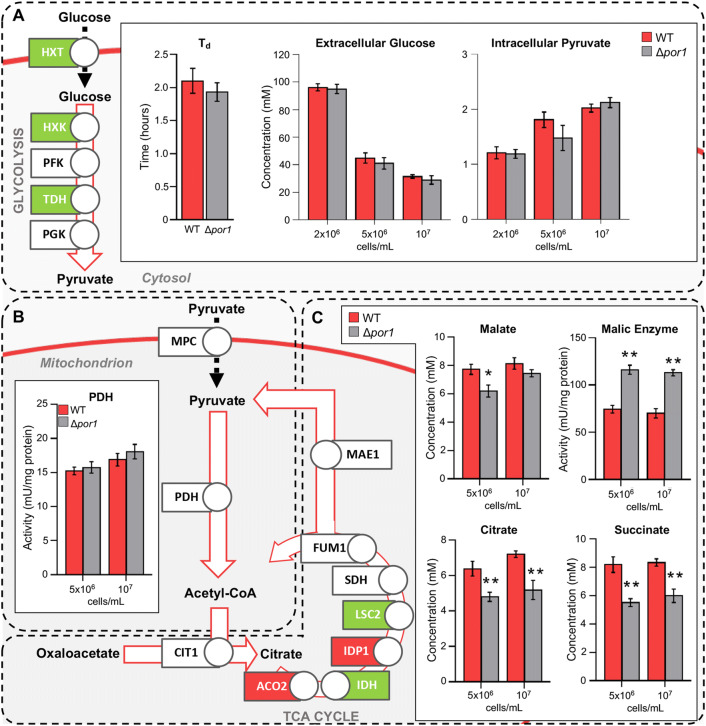

Keeping in mind the effects on mitochondrial functionality observed in Δpor1, we decided to analyze in more detail the transcription levels of genes involved in glucose utilization, as well as the amount of intermediates and the activity of specific enzymes during Δpor1 growth on glucose. As reported in Fig. 3a and detailed in Fig. S5, the expression of some genes encoding high-affinity hexose transporters across plasma membrane was increased, with HXT2 and HXT4 the most up-regulated genes. Furthermore, some genes encoding glycolytic enzymes, such as hexokinases (i.e., HXK2) and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenases (TDH1 and TDH2), were also up-regulated in comparison with the WT. Nevertheless, the duplication time (Td) measured for both strains was similar, as well as glucose consumption and the intracellular amount of the glycolysis-derived pyruvate (Fig. 3a), suggesting that the glycolysis occurs similarly in WT and Δpor1.

Fig. 3.

Analysis of pyruvate synthesis and mitochondrial utilization in dependence of gene expression changes, metabolite synthesis and enzymatic activity. a Scheme of the expression analysis of some genes involved in glucose uptake and glycolysis; quantification of extracellular glucose and intracellular pyruvate (respectively, the substrate and the final product of glycolysis) determined for the indicated strains at different cell densities and their duplication time (Td) measured during growth. b Scheme of the expression analysis of genes involved in mitochondrial uptake of pyruvate and its utilization; quantification of the pyruvate dehydrogenases complex (PDH) activity at the indicated cellular densities. c Scheme of the expression analysis of some genes involved in the TCA cycle; quantification of the TCA intermediates malate, citrate and succinate and of malic enzyme activity determined at the indicated cellular densities. Green and red colors indicate, respectively, up- and down-regulated genes in Δpor1 cells compared with WT, while white indicates unchanged expression. Only fold change values ≥ 2 or≤ − 2 were included. Data in bar charts are expressed as mean (SD) of n = 3 independent experiments where * indicates a P < 0.05 and ** indicates a P < 0.01

Pyruvate is the end-product of glycolysis and, once produced, it can undergo two major metabolic fates: (1) cytosolic decarboxylation by pyruvate decarboxylase (Pdc) to acetaldehyde, the majority of which is then reduced to ethanol due to the Crabtree effect; (2) oxidative decarboxylation to acetyl-CoA in mitochondria, by the pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) complex [41]. In the latter case, pyruvate undergoes mitochondrial uptake, using VDAC1 to cross OMM and the pyruvate mitochondrial carrier (MPC) to cross the IMM. The MPC is a heterodimer formed by Mpc1 and Mpc2 or Mpc3, the latter endowed with a higher capacity for pyruvate import [42]. In front of an increase in MPC1 expression, we found that MPC3 was down-regulated in the Δpor1 (Fig. S5). Since Mpc proteins normally display low level of endogenous expression and Mpc1 is barely detectable when no other subunit is present [42], we can speculate that lack of VDAC1 might bring about an impairment in mitochondrial pyruvate uptake. Furthermore, no significant change in the expression of genes encoding the PDH complex subunits, as well as in PDH enzymatic activity, was observed in Δpor1 (Fig. 3b) similarly to what detected for Δmpc1 mutant, which displays almost no mitochondrial uptake of pyruvate [43]. In this context, when the MCP function is compromised, cells rely on a TCA cycle that operates in a “branched” fashion to provide a mitochondrial pyruvate pool from malate via the malic enzyme, depleting the cycle itself of intermediates [18]. As reported in Fig. 3c, in Δpor1, the levels of TCA cycle intermediates, such as citrate, succinate and malate, were decreased compared with the WT counterparts; furthermore, the malic enzyme activity was strongly increased, indicating the propensity to shunt TCA intermediates towards pyruvate formation. Moreover, TCA cycle provides the electron transport chain (ETC) of reducing equivalents. Electrons enter at the level of complex II as FADH2, which is produced following succinate oxidation to fumarate. This reaction is catalyzed by succinate dehydrogenase (complex II), which is part of both the ETC and TCA cycle. Thus, a TCA cycle with reduced intermediates might influence negatively the respiration, in line with the reduced respiration of Δpor1.

Overall, the reduction of the TCA cycle products suggests the failure of the retrograde response activation, a mitochondrial rescue signalling to the nucleus aimed at promoting the expression of genes involved in restoring some organelle functions [44]. The overexpression of CIT2, encoding a peroxisomal citrate synthase of the glyoxylate shunt (an anaplerotic device of the TCA cycle), is a marker of the retrograde signalling activation [44]. For instance, this occurs in yeast cells devoid of mtDNA (ρ0 or petite) in concert with the overexpression of other genes encoding enzymes that provide support to a defective TCA cycle [45]. Surprisingly, in Δpor1 cells, no up-regulation was observed and, conversely CIT2 was found significantly down-regulated (Fig. S5), indicating that the absence of VDAC1 negatively affects the retrograde signalling activation, completely depleting mitochondria of their functions.

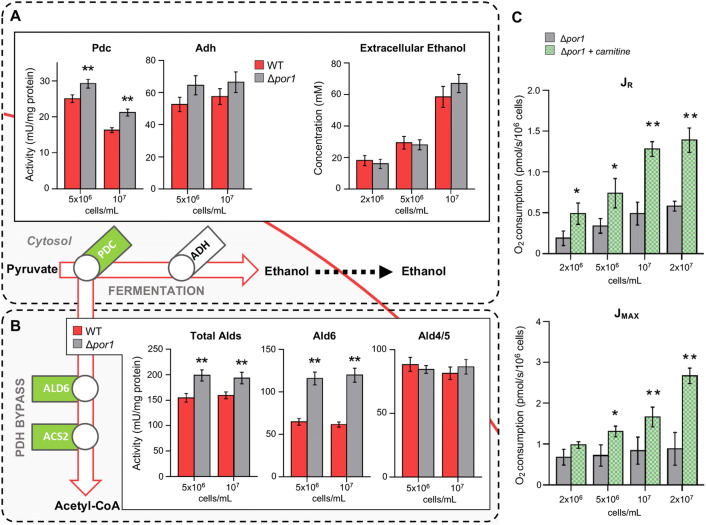

In Δpor1 cell pyruvate preferentially undergoes cytosolic acetyl-CoA transformation by the PDH bypass

Starting from the above results, we analyzed the alternative metabolic fate of the cytosolic pyruvate such as its decarboxylation to acetaldehyde by Pdc followed by ethanol formation. In this occurrence, Pdc activity is mainly due to two Pdc isoenzymes encoded by PDC1 and PDC5; in Δpor1, we found a strong up-regulation of PDC5 in concert with an increase in the Pdc enzymatic activity compared with the WT one (Figs. 4a, S5), suggesting a consequent increase in acetaldehyde formation. In S. cerevisiae, several genes encode alcohol dehydrogenases (Adhs) that catalyze the interconversion of acetaldehyde and ethanol [46]. During growth on glucose, the Adh activity, chiefly responsible for ethanol formation from cytosolic acetaldehyde, is encoded by ADH1. No significant difference was detected between WT and Δpor1 mutant in ADH1 expression as well as in Adh activity, consistent with the same amounts of extracellular ethanol measured in both cultures (Fig. 4a). This indicates that, in front of the increase of Pdc activity, no significant increase in the flux toward ethanol formation was observed, suggesting that Δpor1 utilizes acetaldehyde in another way.

Fig. 4.

Analysis of cytosolic pyruvate utilization in concert with changes in gene expression, enzymatic activities and metabolite amounts in Δpor1 cells compared with WT. a Scheme of the expression analysis of some genes involved in the fermentative pathway and quantification of pyruvate decarboxylase (Pdc) and alcohol dehydrogenase (Adh) enzymatic activities. The bar chart of extracellular ethanol, the final product of fermentation, is also reported. Quantifications were performed at the indicated cellular densities. b Scheme of the expression analysis of some genes of the PDH bypass pathway and quantification of the enzymatic activity of total acetaldehyde dehydrogenases (Alds), of mitochondrial (Ald4/5) and cytosolic (Ald6) isoforms. Quantifications were performed at the indicated cellular densities. c Respiration parameters of the Δpor1 cells measured at different cellular densities during growth in presence and absence of carnitine in the medium. JR is the basal respiration rate, while JMAX represents the uncoupled respiration rate. Substrates and inhibitors used in the measurements are detailed in the text. Color symbolism as in Fig. 3. Data in bar charts are expressed as mean (SD) of n = 3 independent experiments where * indicates a P < 0.05 and ** indicates a P < 0.01

Cytosolic acetaldehyde can be oxidized to acetate that, as an intermediate of the PDH bypass, is activated to acetyl-CoA. Among the different acetaldehyde dehydrogenase (Ald) isoenzymes, Ald6 is the major cytosolic isoform that oxidizes acetaldehyde, whereas the mitochondrial counterparts are Ald4 and Ald5 [47]. In Δpor1, ALD6 was up-regulated together with a significant increase of Ald6 enzymatic activity, while Ald4/5 activity was unaffected despite ALD4 up-regulation (Figs. 4b, S5). Since the expression of the latter is induced under acetaldehyde stress [28], ALD4 increase could be ascribed to a stress response due to cytosolic acetaldehyde that can diffuse freely into the mitochondria. However, given the reduction of pyruvate mitochondrial uptake, the increase of Pdc activity and the unchanged flux towards ethanol production in the Δpor1, the increase in Ald6 activity points to an enhanced flux of cytosolic pyruvate channeled towards cytosolic acetyl-CoA formation. Accordingly, ACS2, encoding the acetyl-CoA synthetase (Acs2) responsible in the cytosol for the activation of acetate to acetyl-CoA [48], was up-regulated in the mutant, whereas the mitochondrial counterpart (ACS1) was unaffected (Fig. S5).

Once produced, the cytosolic acetyl-CoA can be imported into mitochondria as acetyl-carnitine by means of the carnitine shuttle system. Here, the shuttle function of carnitine is assisted by carnitine acetyl-transferases, which catalyze the reversible transfer of the acetyl moiety of acetyl-CoA to carnitine, and by the carnitine/acetyl-carnitine translocase Crc1. In the mitochondria, the carnitine acetyl-transferase Cat2 catalyzes the reverse reaction, thereby regenerating carnitine and acetyl-CoA, which enters the TCA cycle [49]. Since S. cerevisiae is unable to synthesize carnitine endogenously, the shuttle requires carnitine supplementation in the growth medium [50]. Surprisingly, in Δpor1 the genes encoding the three carnitine acetyl-transferases (Yat1/Yat2 and Cat2) and Crc1 were strongly down-regulated compared with the WT (Fig. S6A). Anyway, when carnitine was supplied to the growth medium, no difference was observed in glucose consumption and intracellular pyruvate (Fig. S6B) between the WT and the mutant. On the contrary, the presence of carnitine ameliorated both the respiratory rate and the maximal respiratory capacity of the mutant (Fig. 4c), while no effect on respiration was observed in the WT (Fig. S7). This finding suggests, on the one hand, that a compensative feeding from the cytosol provided by the carnitine shuttle can partially rescue the mitochondrial deficits of Δpor1 mutant linked to a TCA cycle not properly supplied and, on the other hand, that more cytosolic acetyl-CoA is available in the mutant.

Lipid biosynthesis is enhanced in the absence of VDAC1

Cytosolic acetyl-CoA is a precursor in de novo synthesis of fatty acids (FAs). The first and rate-limiting step in FA synthesis is the carboxylation of acetyl-CoA to malonyl-CoA by the acetyl-CoA carboxylase encoded by ACC1. Then, malonyl-CoA undergoes a cyclic series of reactions catalyzed by a multifunctional fatty acid synthase (FAS) complex, producing FAs containing 16–18 carbon atoms. The subunits of the FAS complex are encoded by FAS1 and FAS2 [51]. Both these genes, as well as ACC1, were up-regulated in Δpor1 (Figs. 5a, S8). In addition, malonyl-CoA produced by Acc1 is also required as a two-carbon donor for FA elongation that takes place in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) producing very long-chain FAs (up to C26). In the mutant, an up-regulation was observed for ELO2 and ELO3, encoding components of the FA elongation system and also for OLE1, encoding the Δ9-FA desaturase (Fig. 5a). This enzyme forms mono-unsaturated FAs, which are the only type of unsaturated FAs present in S. cerevisiae [51].

Fig. 5.

Analysis of lipids biosynthesis in concert with changes in gene expression and cellular changes. a Scheme of the expression analysis of genes involved in lipids biosynthesis in the cytosol and in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). PA phosphatidic acid, CDP-DAG cytidine diphosphate diacylglycerol, TAG triacylglycerol, PE phosphatidylethanolamine, PC phosphatidylcholine, PS phosphatidylserine. b Effect of Soraphen A (SorA) on yeast growth monitored by drop-serial dilutions. 5 µl of a concentrated suspension (108 cell/ml on the left and 107 cell/ml on the right) and serial dilutions of the indicated strains were spotted onto glucose medium plates with or without SorA. Growth was recorded after 2 days. c Quantification of the main phospholipid precursors: fatty acids (FAs), PA, diacylglycerols (DAGs) and TAGs. d Representative microscopy pictures of lipid droplets detected in yeast cells by Nile Red staining and relative quantification measured at the indicated time-points. Exp exponential phase, Diaux diauxic shift. Evaluation of about 500 cells for each sample in n = 3 independent experiments was performed. e Representative microscopy picture of vacuole detected in yeast cells by carboxy-DCFDA staining and analysis of vacuole diameter. Evaluation performed as in (d). f Analysis of cellular volume in yeast cells at the indicated time-points. Exp exponential phase, Diaux diauxic shift. g Cardiolipin (CL) quantification performed at the indicated cellular densities. Color symbolism as in Fig. 3. Data in histograms are expressed as mean (SD) of n = 3 independent experiments where ** indicates a P < 0.01

Soraphen A (SorA) is a specific inhibitor of Acc1 [52] and is used for indirectly measuring the enzyme activity [53]. As shown in Fig. 5b, Δpor1 grew like the WT on standard glucose media, but it was less sensitive to the presence of SorA in the medium, indicating a higher Acc1 activity. All this correlated with a higher content of FA in Δpor1 (Fig. 5c). FAs are building blocks for phosphatidic acid (PA), which, in turn, functions as a central lipid intermediate and precursor of phospholipids (PLs), diacylglycerols (DAGs) and triacylglycerols (TAGs) [54]. Quantifications of PA, DAGs and TAGs showed that the content of these lipid species was significantly higher in Δpor1 compared with that of the WT (Fig. 5c). Notably, Acc1 hyperactivity leads to elevated FA production, TAG increase and accumulation of lipid droplets (LDs) [53], specialized organelles dedicated to the dynamic storage of neutral lipids, which, according to nutritional requirements provide cells with membrane and energy sources to support cellular functions and protection against lipotoxicity [55]. As shown in Fig. 5d, Δpor1 displayed a higher number of LDs, which localized especially at the cytosolic periphery due to the presence of an enlarged vacuole (Fig. 5e). A change of vacuolar size/morphology is not so unexpected in the light of modifications in lipid metabolism, since this organelle undergoes cycles of fission and fusion events that allow adapting its size and number to environmental and intracellular changes. Furthermore, the increased amount of LDs and the presence of an enlarged vacuole in the Δpor1 correlate with a cell-size dimensional increase of about 30% in comparison with the WT (Fig. 5f), despite a general decrease of the mitochondrial mass due to VDAC1 lack. Finally, PA also supplies cells with the mitochondrion-specific dimeric PL cardiolipin (CL) [56]. No significant difference was detected between Δpor1 and WT in the CL level referred to mitochondrial protein content (Fig. 5g) as well as in the regulation of genes involved in this pathway (Fig. S8), in agreement with the previous report [11].

Synthesis of inositol is significantly increased in Δpor1 yeast

Analysis of microarray data highlighted the upregulation of specific genes encoding the first glycolysis reactions, but without any correspondent increase of this pathway. In particular, HKX2, coding for the second hexokinase isoform, was found overexpressed. Beyond a glycolysis substrate, the product of Hxt2 reaction, glucose-6-phosphate, is an important precursor of inositol (Ins). Focusing on this aspect, we found that other genes encoding enzymes involved in Ins synthesis, such as INO1 and INM1, resulted equally up-regulated in the mutant (Figs. 6a, S8). INO1 encodes inositol-3-phosphate synthase, the pathway rate-limiting enzyme that converts glucose-6-phosphate to inositol-3-phosphate, which is then dephosphorylated to Ins by the INM1-encoded inositol-3-phosphate phosphatase. Ins is also the precursor for phosphatidylinositol (PI) [57]. Measurements of intracellular Ins indicated that the Δpor1 has higher levels compared with the WT ones (Fig. 6b). INO1 undergoes a tight transcriptional regulation, which in turn affects PL metabolism: INO1 transcription is regulated by Ins availability in the medium and requires cis- and trans-acting elements, such as the inositol-sensitive UASINO and the corresponding trans-acting positive Ino2/Ino4 heterodimer, and the Opi1 (OverProducer of Inositol) repressor. Derepressed expression (or upregulation) of INO1 correlates with the Opi− phenotype characterized by Ins overproduction and excretion [57, 58]. Notably, measurements of extracellular Ins showed that Δpor1 had high level of Ins in the growth medium (Fig. 6b). In line with this, the plate assay used for detecting the Opi− phenotype [59] revealed that the mutant excreted enough Ins to support growth of Ins-auxotrophic strains (Fig. 6c) indicating that VDAC1 deficiency correlates with an Opi− phenotype. Opi1 activity as a repressor is regulated by its cellular localization, which strictly depends on PA amount in the ER [60]. Indeed, Opi1 is a PA-binding protein: in the presence of Ins, PA levels are low and Opi1 is in the nucleus repressing transcription of INO1 and other UASINO-containing genes. On the contrary, in the absence of exogenous Ins, PA levels are high and Opi1 is sequestered in the ER by binding PA. Consequently, Ino2/Ino4-mediated transcriptional activation is allowed [59]. Consistent with the role of PA as a regulatory signal, conditions that increase PA levels also yield an Opi− phenotype [61]. Thus, we hypothesize that the elevated cellular PA content present in Δpor1 could be responsible for the INO1 derepression leading to the Opi− phenotype. Interestingly, some other genes of lipid biosynthesis that were up-regulated in the mutant (i.e. CDS1, CHO1, OPI3) are Opi1-regulated genes [58]. This further supports the notion that in the mutant, the Opi1-mediated repression is relieved.

Fig. 6.

Analysis of production and excretion of inositol. a Scheme of the expression analysis of genes involved in inositol biosynthesis. G-6-P glucose-6-phosphate, Ins-3-P inositol-3-phosphate, Ins inositol, PI phosphatidylinositol. Color symbolism as in Fig. 3. b Quantification of intracellular and extracellular Ins in yeast cells determined at the indicated cellular densities. Data are expressed as mean (SD) of n = 3 independent experiments where ** indicates a P < 0.01. c Left: WT and Δpor1 cells were spotted on agar plates without inositol. After 2 days of growth, plates were sprayed with a suspension of inositol auxotrophic (Ino−) cells (ire1Δ, see Materials and Methods) and incubated for growth for further 2 days. The Ino− strain only grows as a halo around the spotted strain excreting inositol. Right: WT and Δpor1 cells were spotted on agar plates with and without inositol. After 2 days of growth, Ino− cells (hac1Δ, see Materials and Methods) were dropped (5 µl from a suspension of 107 cells/ml) close to the WT and Δpor1-grown spots and further incubated for growth. On agar plates without inositol, Ino− cells only grow as spots close to the strain excreting inositol

Discussion

VDAC1 is the irreplaceable responsible of outer membrane permeability in yeast

The extraordinary abundance of VDAC1 in the yeast OMM confers to this protein a fundamental role in the regulation of mitochondrial permeability and of the overall cellular metabolism. As claimed in the last years, there are other members of the transmembrane β-barrel family proteins allowing, in principle, the permeation of the OMM. However, only the recent determination at high confidence of S. cerevisiae mitochondrial proteome [17] allowed understanding the actual impact of the other(s) channels for the overall OMM permeability. In Table 1, the available information is compared with the expression data obtained in this work. Theoretically, VDAC2 is the best candidate to replace VDAC1 function: both homology modeling and electrophysiological characterization indicate a strong similarity between the two isoforms [15, 16]. Accordingly, the overexpression of POR2 in Δpor1 cells was able to restore yeast growth during growth on glycerol, suggesting that the two proteins are interchangeable. Anyway, POR2 is extremely poorly expressed in physiological condition [17] and its overexpression in Δpor1 was achieved only in the presence of external stimuli [39]. Beyond VDAC isoforms, OMM contains others β-barrel proteins. Tom40, the channel for the protein precursors and member of the TOM complex, and Sam50, the analogous of omp85 and component of the SAM complex, showed a smaller conductance compared to VDAC1 (about 1/10) and positive ion selectivity [62, 63]. Their abundance in the mitochondrion is, respectively, about 1/10 and 1/100 of VDAC1 and their transcription is not stimulated either by a fermentative metabolism or by the absence of VDAC1. This result suggests that, if they have a pore-forming activity and any sort of metabolic function [64], it must be accessory to their main role in the protein import and sorting. Similar findings came out from the analysis of the other OMM proteins listed in Table 1, such as Mdm10 [65], OMC7, OMC8, Mim1 and Ayr1 [66]. By summing the number of pore-forming proteins times their own conductance, as estimated in symmetrical buffer conditions with the same concentration (i.e., 1 M KCl), we roughly calculated the global conductance of the OMM in a single mitochondrion. From this calculation, it results that, at least in yeast, OMM has an overall conductance of less than 30 µS, but about 27 µS is developed by VDAC1. On these bases, we can conclude that the other pore-forming proteins have a negligible impact on the global conductance of the mitochondrial outer membrane, i.e., in Δpor1 cells only one tenth of the potential permeability was left to mitochondria by the alternative pore-forming proteins. Thus, if small ions can still permeate the OMM, bigger molecules as pyruvate or nucleotides are hindered to do, because only VDAC has a sufficient diameter to allow such a transport. As a consequence, mtDNA maintenance is hampered and the transcription of mitochondrial genes encoding OXPHOS subunits is inactivated, triggering to an impairment of the respiratory chain, according with what observed in the current work and previously [14, 39]. Therefore, it is not surprising that the absence of VDAC1 strongly affects mitochondrial mass, organization and functionality, as well as the organelle biogenesis, a feature in line with the function recently ascribed to VDAC1 as a component of the carrier protein import machinery [11].

Table 1.

Summary of the present knowledge concerning the pore-forming proteins detected in the S. cerevisiae outer mitochondrial membrane

| Glucose | Glycerol | Glucose | Electrophysiological features | Tot. conductance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Copy/mito according to [17] | FC in Δpor1 (this work) | Channel conductance | Voltage dependence | Ref. | |||

| Por1 | 6800 | 19,000 | – | 4–4.5 nS (1 M KCl) | > ± 30 mV | [15] | 27.2 µS |

| Por2 | 1–2 | 1–2 | NM | 3.6–3.8 nS (1 M KCl) | > ± 40–50 mV | [15, 16] | |

| Tom40 | 550 | 590 | + 1,70 | 0.36–0.37 nS (0.25 M KCl) | > ± 70 mV | [63] | 0.8 µS |

| Sam50 | 35 | 45 | + 1,51 | 0.64 nS (0.25 M KCl) | > ± 80 mV | [63] | 0.1 µS |

| Mim1 | ND | ND | NM | 0.58 nS (0.25 M KCl) | > ± 80 mV | [66] | |

| Mim2 | 4 | 5 | NM | ||||

| Mdm10 | 3 | 5 | − 1,43 | 0.48 nS (0.25 M KCl) | > ± 100 mV | [66] | |

| Ayr1 | 250 | 470 | − 1,95 | 1.47 nS (0.25 M KCl) | > ± 100 mV | [66] | 1.5 µS |

| OMC7 | ND | ND | ND | 0.57 nS (0.25 M KCl) | > − 60 mV | [66] | |

| OMC8 | ND | ND | ND | 0.55 nS (0.25 M KCl) | > + 100 mV | [66] | |

| 29.6 µS | |||||||

Copy number of each protein per mitochondrion, fold change (FC) of the expression in Δpor1 cells compared with WT, main electrophysiological features and the estimated contribution of each protein to the overall permeability of mitochondria are reported. Por1 and Por2 are the two VDAC isoform. Tom40 is the channel for the protein precursors and member of the TOM complex. Sam50 is the analogous of omp85 and component of the SAM (also termed TOB) complex. Mdm10 is a predicted 19 β-strands barrel and the receptor of the ERMES complex, tethering mitochondria and ER. OMC7 and OMC8 are two previously unknown pore-forming proteins, both with a similar conductance, lower than VDAC1. Mim1 and Mim2 are two 13 kDa protein that localizes in the OMM by a single transmembrane α-helix but are still badly definite. Ayr1 is a 32 kDa protein localized in OMM and ER whose function is still unclear, but claimed to be involved in the lipid metabolism, that, upon reconstitution, shows channel-forming activity. The calculation of the global conductance of a single mitochondrion was obtained by summing the number of pore-forming proteins times their own conductance, as estimated in the symmetrical buffer 1-M KCl

ND not detected, NM not measurable

Deletion of VDAC1 turns off the mitochondrion and forces the cell to change the metabolic map

Overall, the deletion of VDAC1 in yeast cell strongly reduces the accessibility of the mitochondrial bioenergetics machinery, leading to the mitochondrial dysfunction, whose results are depicted by the microarray results. In principle, one could expect that such defect would be signaled to the nucleus, as it happens in ρ0 cells by the retrograde signalling [45]. Our results, instead, indicate that this signalling does not happen since no up-regulation of genes that characterized the retrograde response activation takes place. Even the VDAC2 isoform expression is not enhanced in this occurrence [39]. Thus, the mutant re-organizes the metabolism to cope with the severe mitochondrial impairment. Accordingly, the residual TCA cycle works in a “branched” fashion shunting intermediates toward mitochondrial pyruvate generation via the malic enzyme to face with the impairment of pyruvate import into mitochondria and the TCA cycle products are significantly reduced, depleting mitochondria and the rest of the cell of important intermediates. The latter is strictly related to the lack of retrograde response, as instead it takes place in the mutant ρ0 [45], in which both mtDNA maintenance and oxidative phosphorylation are abolished. Thus, it is clear that VDAC1 must play a direct or indirect role also in the activation of this rescue pathway, even if the precise mechanism is unknown. It is commonly accepted that the retrograde response can be stimulated by a decrease of ATP production, MMP drops and/or increase of reactive oxygen species (ROS), all hallmarks of mitochondrial dysfunction. Anyway, only the first two parameters were found similar in Δpor1 and ρ0, as detected by previous works [39, 67], while striking differences appeared in terms of ROS content. While Δpor1 cells show a substantial and unexpected ROS reduction in comparison to WT ([39] and Fig. S9), a significant increase of ROS was detected in ρ0 cells, linked to the raised activity of the ER-localized NADPH oxidase Yno1 [68]. At high levels, indeed, ROS are able to stimulate the oxidative stress response, a mechanism that involves the retrograde genes RTG1 and RTG2 [69]. Therefore, based on this evidence, we can speculate that the failure of retrograde signalling activation observed in Δpor1 might be attributed to the low ROS levels detected into the mutant.

Hence, in the absence of an adequate response to the mitochondrial dysfunction and of any rescue system working in case of VDAC1 failure, how the yeast can survive when the porin is lacking? The deficient yeast is indeed unable to properly grow on non-fermentable substrates. Even though it can utilize glucose as carbon source, a profound metabolic re-organization is set up, to compensate not only the lack of chemical energy produced in the organelle, but also the number of metabolic important intermediates coming from the mitochondria. Combining the analysis of the whole-genome expression and the biochemical assays, here we demonstrated and characterized for the first time the complete metabolic rewiring implemented in Δpor1 cells, which is schematized in Fig. 7. To overcome the absence of VDAC1, pyruvate metabolism is shifted from mitochondria to the cytosol, via the PDH bypass, and the flux towards fatty acids and phospholipids biosynthesis is enhanced. Concomitantly, in the mutant, the amount of storage compartments (lipid droplets) increases and yeast experience changes in the vacuole and cell size. Distinct lipid species have been identified to differentially contribute to these cycles, among which DAGs and PA are critical for vacuolar fusion. In particular, DAG is a fusogenic lipid and an increase in its levels raises the fusogenicity of vacuoles [70, 71]. Whilst, the increase of cell volume must coincide with an increase of the plasma membrane surface: to obtain better access to environmental glucose, yeast raises its surface, increasing Hxt proteins on plasma membrane, as supported by transcriptional data. Furthermore, the increase of PA cellular content relieves the Opi1-mediated repression and the mutant overproduces and excretes inositol. Overall, such a metabolic rewiring allows cells to cope with the absence of VDAC1 during growth in a fermentative condition (glucose), but restricts survival during chronological aging, as well as, growth on non-fermentable substrate (glycerol).

Fig. 7.

Comparison between wild-type and Δpor1 cell metabolism upon growth on glucose. a In WT cells, glucose is imported through hexose transporters (HXT) and converted by glycolysis in pyruvate. The latter undergoes ethanolic fermentation or, alternatively, is imported into functional mitochondria, where it is decarboxylated to acetyl-CoA and enters into TCA cycle. In these conditions, only a small fraction of pyruvate is converted into cytosolic acetyl-CoA and used as a substrate for lipid biosynthesis. b In mutant yeast, VDAC1 deletion promotes the impairment of nucleotides entering into the mitochondria, affecting both mtDNA replication and expression; as a consequence, the respiration of Δpor1 cell is strongly compromised, as well as the overall organelle structure and function. Since no retrograde signalling is activated in Δpor1 cells, the TCA cycle results impoverished. In front of a general impairment of mitochondrial functionality, yeast cells improve the most important cytosolic pathways. The import and utilization of glucose via glycolysis and fermentation is not affected; rather, due to the overexpression of hexokinase 2 (Hxk2), the phosphorylation of glucose to glucose-6-phosphate (G-6-P) is enhanced and the latter is used as substrate for inositol synthesis and excretion. The pyruvate import through specific mitochondrial carriers (MPC) is hampered and the molecule is pushed towards cytosolic utilization via PDH bypass by the increased activity of cytosolic acetaldehyde dehydrogenase (Ald6) and acetyl-CoA synthetase (Acs2). Overall, these changes increase the cytosolic rate of acetyl-CoA, which is used by mutant yeast as substrate for the fatty acids biosynthesis; once produced, lipids are stored into lipid drops (increased in size and number) and used to build new plasma membrane

The result of VDAC1 deletion in yeast recapitulates the Warburg metabolic adaptation in cancer cells

The metabolic rewiring summarized above reminds the changes happening in mammalian cells during the Warburg effect [72]. The Warburg effect was discovered about one century ago and essentially states that cancer cells utilize preferentially aerobic glycolysis instead of oxidative phosphorylation as a mean to quickly produce ATP. The Warburg effect, its origin and its consequences are still a matter of warm debate, and despite it is now considered certain, by genetic and pharmacological studies, that it is required for tumor growth [73, 74], the origin of its triggering remains unknown even today [75]. Similarity between S. cerevisiae as a model system and proliferating cancer cells has been already outlined [76], since these two cell systems show parallel metabolic fluxes. In the normal yeast, the Crabtree effect takes place in conjunction with the transition from respiration to fermentation: but the Crabtree effect is reversible and genetically determined since it is part of the innate adaptive mechanisms of the yeast. The Warburg effect in cancer cells is not genetically determined and its profound origin is not yet known. What happens in our Δpor1 model largely corresponds to the results of the long-term, not genetically determined and, thus, irreversible metabolic reprogramming that is the hallmark of the Warburg effect.

In brief, the high-affinity glucose transporters are over-expressed, as in several cancer cell lines [77]. Pyruvate cannot be efficiently metabolized by mitochondria since its transport is affected by gene down-regulation and depressed import of the carrier to the IMM: consequently, pyruvate is channeled to cytosol toward acetaldehyde (lactic acid in cancer cell) [78]. In both cases, the fate of pyruvate catabolite is to improve the biomass or to be exported outside the cell. In addition, also tumor cells, as our mutant yeast, are characterized by elevated FA synthesis; both cancer cells and Δpor1 yeast rely on up-regulation of FA synthesis and their incorporation in complex lipids for membrane genesis, a requisite for rapidly proliferating cells [79]. The description of these metabolic features overlaps what happens in the proliferating cancer cells upon Warburg effect and the changes found in Δpor1 cells.

VDAC1 has several important roles whose deletion would mimic the blast of Warburg effect: it allows the flow of pyruvate and many metabolites towards the inner membrane, it is involved in the import of carrier protein targeting the inner membrane, and it is the docking site of hexokinase, the first enzyme of glycolysis. It is, thus, very attractive the hypothesis that the VDAC1 deletion in yeast acts as the unknown mutation that triggers the Warburg effect in proliferating cancer cells.

In higher eukaryotes, the analysis of VDAC1 deletion is more difficult because three VDAC isoforms are present

The comparison of S. cerevisiae metabolism with that of multicellular eukaryotes is, unfortunately, only apparently straightforward: for example, the evolution conferred to them three isoforms of VDAC to maintain mitochondria perfectly active [1]. This means that Δpor1 yeast is a very convenient model, since the complication of multiple VDAC isoforms is absent.

In mammalian, indeed, there are emerging isoform-dependent features that, as of now, cannot be just correlated with a sequence discrepancy [80]; i.e., VDAC3 knockout mice are infertile [81]; the lack of VDAC1 in mice gives specific alterations in mitochondrial respiration and structural aberrations in isolated mitochondria [82]. Additionally, VDAC3 knockdown experiments modulate mitochondrial membrane potential and ATP cell levels in response to drugs treatment in HepG2 cells [83]. Thus, although a common transport function may be attributed to all VDAC isoforms, there appears to be unique roles as well. Unfortunately, there is not a high confidence mitochondrial proteome of eukaryotic mitochondria that could be utilized for quantitative considerations, also because the mitochondrial proteome is highly dynamic depending, among others, on the tissue, development, and age. Nevertheless, the most intriguing result comes from VDAC2: this isoform cannot be deleted at all in mouse, since this gives a lethal phenotype. The role of VDAC2 in mammalian has been associated with apoptosis and thus with one of the main hallmarks of cancer cells [84].

Despite this more complicate situation in multicellular organisms, our results in yeast, that have developed initial observations [85], show that VDAC(s) in eukaryotic cells have a pivotal function in the basic organization of the cellular metabolism since it contributes to the overall regulation of mitochondria. In the light of these results, we can conclude that VDAC1 is much more than a simple channel but rather, it has a key role in the coordination of the entire cellular metabolism.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

VDP acknowledges the financial support by MIUR (PRIN 2015795S5W_005) and University of Catania (Piano Triennale Ricerca). MV acknowledges the financial support by Cariplo Foundation 2015-0641. The authors acknowledge the support of Dr. Giulia Gentile for the initial experimental design of microarray analysis.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Marina Vai, Email: marina.vai@unimib.it.

Vito De Pinto, Email: vdpbiofa@unict.it.

References

- 1.Messina A, Reina S, Guarino F, De Pinto V. VDAC isoforms in mammals. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr. 2012;1818:1466–1476. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shoshan-Barmatz V, De Pinto V, Zweckstetter M, Raviv Z, Keinan N, Arbel N. VDAC, a multi-functional mitochondrial protein regulating cell life and death. Mol Asp Med. 2010;31:227–285. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bayrhuber M, Menis T, Habeck M, Becker S, Giller K, Villinger S, Vonrhein C, Griesinger C, Zweckstetter M, Zeth K. Structure of the human voltage-dependent anion channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:15370–15375. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808115105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hiller S, Graces RG, Malia TJ, Orekhov VY, Colombini M, Wagner G. Solution structure of the integral human membrane protein VDAC-1 in detergent micelles. Science. 2008;321:1206–1210. doi: 10.1126/science.1161302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ujwal R, Cascio D, Colletier JP, Fahama S, Zhanga J, Torod L, Pinga P, Abramson J. The crystal structure of mouse VDAC1 at 2.3 Å resolution reveals mechanistic insights into metabolite gating. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:17742–17747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809634105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schredelseker J, Paz A, López CJ, Altenbach C, Leung CS, Drexler MK, Chen JN, Hubbell WL, Abramson J. High resolution structure and double electron-electron resonance of the zebrafish voltage-dependent anion channel 2 reveal an oligomeric population. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:12566–12577. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.497438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Magrì A, Messina A. Interactions of VDAC with proteins involved in neurodegenerative aggregation: an opportunity for advancement on therapeutic molecules. Curr Med Chem. 2017;24:4470–4487. doi: 10.2174/0929867324666170601073920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Magrì A, Reina S, De Pinto V. VDAC1 as pharmacological target in cancer and neurodegeneration: focus on its role in apoptosis. Front Chem. 2018;6:108. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2018.00108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reina S, Guarino F, Magrì A, De Pinto V. VDAC3 as a potential marker of mitochondrial status is involved in cancer and pathology. Front Oncol. 2016;6:264. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2016.00264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reina S, De Pinto V. Anti-cancer compound targeted to VDAC: potential and perspectives. Curr Med Chem. 2017;24:4447–4469. doi: 10.2174/0929867324666170530074039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ellenrieder L, Dieterle MP, Nguyen Doan K, Mårtensson CU, Floerchinger A, Campo ML, Pfanner N, Becker T. Dual role of mitochondrial porin in metabolite transport across the outer membrane and protein transfer to the inner membrane. Mol Cell. 2019;73:1056–1065. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dihanich M, Suda K, Schatz G. A yeast mutant lacking mitochondrial porin is respiratory-deficient, but can recover respiration with simultaneous accumulation of an 86-kd extramitochondrial protein. EMBO J. 1987;6:723–728. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb04813.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dihanich M, Schmid A, Oppliger W, Benz R. Identification of a new pore in the mitochondrial outer membrane of a porin-deficient yeast mutant. Eur J Biochem. 1989;182:703–708. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1989.tb14780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blachly-Dyson E, Song J, Wolfgang WJ, Colombini M, Forte M. Multicopy suppressors of phenotypes resulting from the absence of yeast VDAC encode a VDAC-like protein. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:5727–5738. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.10.5727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guardiani C, Magrì A, Karachitos A, Di Rosa MC, Reina S, Bodrenko I, Messina A, Kmita H, Ceccarelli M, De Pinto V. yVDAC2, the second mitochondrial porin isoform of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg. 2018;1859:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2018.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Magrì A, Karachitos A, Di Rosa MC, Reina S, Conti Nibali S, Messina A, Kmita H, De Pinto V. Recombinant yeast VDAC2: a comparison of electrophysiological features with the native form. FEBS Open Bio. 2019;9:1184–1193. doi: 10.1002/2211-5463.12574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morgenstern M, Stiller SB, Lübbert P, Peikert CD, Dannenmaier S, Drepper F, Weill U, Höß P, Feuerstein R, Gebert M, Bohnert M, van der Laan M, Schuldiner M, Schütze C, Oeljeklaus S, Pfanner N, Wiedemann N, Warscheid B. Definition of a high-confidence mitochondrial proteome at quantitative scale. Cell Rep. 2017;19:2836–2852. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Orlandi I, Pellegrino Coppola D, Vai M. Rewiring yeast acetate metabolism through MPC1 loss of function leads to mitochondrial damage and decreases chronological lifespan. Microbial Cell. 2014;1:393–405. doi: 10.15698/mic2014.12.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leggio L, Guarino F, Magrì A, Accardi-Gheit R, Reina S, Specchia V, Damiano F, Tomasello MF, Tommasino M, Messina A. Mechanism of translation control of the alternative Drosophila melanogaster voltage dependent anion channel 1 mRNAs. Sci Rep. 2018;8:5347. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-23730-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Löke M, Kristjuhan K, Kristjuhan A. Extraction of genomic DNA from yeasts for PCR-based applications. Biotechniques. 2011;50:325–328. doi: 10.2144/000113672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCt method. Methods. 2011;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koning AJ, Lum PY, Williams JM, Wright R. DiOC6 staining reveals organelle structure and dynamics in living yeast cells. Cell Motil Cytoskelet. 1993;25:111–128. doi: 10.1002/cm.970250202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Magrì A, Belfiore R, Reina S, Tomasello MF, Di Rosa MC, Guarino F, Leggio L, De Pinto V, Messina A. Hexokinase I N-terminal based peptide prevents the VDAC1-SOD1 G93A interaction and re-establishes ALS cell viability. Sci Rep. 2016;6:34802. doi: 10.1038/srep34802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Orlandi I, Ronzulli R, Casatta N, Vai M. Ethanol and acetate acting as carbon/energy sources negatively affect yeast chronological aging. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2013;2013:802870. doi: 10.1155/2013/802870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Orlandi I, Pellegrino Coppola D, Strippoli M, Ronzulli R, Vai M. Nicotinamide supplementation phenocopies SIR2 inactivation by modulating carbon metabolism and respiration during yeast chronological aging. Mech Ageing Dev. 2017;161:277–287. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2016.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orlandi I, Stamerra G, Vai M. Altered expression of mitochondrial NAD+ carriers influences yeast chronological lifespan by modulating cytosolic and mitochondrial metabolism. Front Genet. 2018;9:676. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2018.00676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trindade D, Pereira C, Chaves SR, Manon S, Côrte-Real M, Sousa MJ. VDAC regulates AAC-mediated apoptosis and cytochrome c release in yeast. Microb Cell. 2016;3:500–510. doi: 10.15698/mic2016.10.533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aranda A, del Olmo M. Response to acetaldehyde stress in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae involves a strain-dependent regulation of several ALD genes and is mediated by the general stress response pathway. Yeast. 2003;20:747–759. doi: 10.1002/yea.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Postma E, Verduyn C, Scheffers WA, Van Dijken JP. Enzymic analysis of the crabtree effect in glucose-limited chemostat cultures of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:468–477. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.2.468-477.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Assis LJ, Zingali RB, Masuda CA, Rodrigues SP, Montero-Lomelí M. Pyruvate decarboxylase activity is regulated by the Ser/Thr protein phosphatase Sit4p in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Yeast Res. 2013;13:518–528. doi: 10.1111/1567-1364.12052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steensma HY, Tomaska L, Reuven P, Nosek J, Brandt R. Disruption of genes encoding pyruvate dehydrogenase kinases leads to retarded growth on acetate and ethanol in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 2008;25:9–19. doi: 10.1002/yea.1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bourque SD, Titorenko VI. A quantitative assessment of the yeast lipidome using electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. J Vis Exp. 2009;30:1513. doi: 10.3791/1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gallet PF, Maftah A, Petit JM, Denis-Gay M, Julien R. Direct cardiolipin assay in yeast using the red fluorescence emission of 10-N-nonyl acridine orange. Eur J Biochem. 1995;228:113–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Greenberg ML, Reiner B, Henry SA. Regulatory mutations of inositol biosynthesis in yeast: isolation of inositol-excreting mutants. Genetics. 1982;100:19–33. doi: 10.1093/genetics/100.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vanoni M, Vai M, Popolo L, Alberghina L. Structural heterogeneity in populations of the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Bacteriol. 1983;156:1282–1291. doi: 10.1128/jb.156.3.1282-1291.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stuart RA. Supercomplex organization of the oxidative phosphorylation enzymes in yeast mitochondria. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2008;40:411–417. doi: 10.1007/s10863-008-9168-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mileykovskaya E, Penczek PA, Fang J, Mallampalli VK, Sparagna GC, Dowhan W. Arrangement of the respiratory chain complexes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae supercomplex III2IV2 revealed by single particle cryo-electron microscopy. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:23095–23103. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.367888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moran JV, Mecklenburg KL, Sass P, Belcher SM, Mahnke D, Lewin A, Perlman P. Splicing defective mutants of the COXI gene of yeast mitochondrial DNA: initial definition of the maturase domain of the group II intron aI2. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:2057–2064. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.11.2057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Magrì A, Di Rosa MC, Tomasello MF, Guarino F, Reina S, Messina A, De Pinto V. Overexpression of human SOD1 in VDAC1-less yeast restores mitochondrial functionality modulating beta-barrel outer membrane protein genes. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg. 2016;1857:789–798. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2016.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fabrizio P, Gattazzo C, Battistella L, Wei M, Cheng C, McGrew K, Longo VD. Sir2 blocks extreme life-span extension. Cell. 2005;123:655–667. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pronk JT, Yde Steensma H, Van Dijken JP. Pyruvate metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1996;12:1607–1633. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0061(199612)12:16<1607::aid-yea70>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bender T, Pena G, Martinou JC. Regulation of mitochondrial pyruvate uptake by alternative pyruvate carrier complexes. EMBO J. 2015;34:911–924. doi: 10.15252/embj.201490197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bricker DK, Taylor EB, Schell JC, Orsak T, Boutron A, Chen YC, Cox JE, Cardon CM, Van Vranken JG, Dephoure N, Redin C, Boudina S, Gygi SP, Brivet M, Thummel CS, Rutter J. A mitochondrial pyruvate carrier required for pyruvate uptake in yeast, Drosophila, and humans. Science. 2012;337:96–100. doi: 10.1126/science.1218099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Butow RA, Avadhani NG. Mitochondrial signaling: the retrograde response. Mol Cell. 2004;14:1–15. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00179-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Epstein CB, Waddle JA, Hale W, 4th, Davé V, Thornton J, Macatee TL, Garner HR, Butow RA. Genome-wide responses to mitochondrial dysfunction. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:297–308. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.2.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.de Smidt O, du Preez JC, Albertyn J. The alcohol dehydrogenases of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: a comprehensive review. FEMS Yeast Res. 2008;8:967–978. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2008.00387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saint-Prix F, Bönquist L, Dequin S. Functional analysis of the ALD gene family of Saccharomyces cerevisiae during anaerobic growth on glucose: the NADP+-dependent Ald6p and Ald5p isoforms play a major role in acetate formation. Microbiology. 2004;150:2209–2220. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26999-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van den Berg MA, de Jong-Gubbels P, Kortland CJ, van Dijken JP, Pronk JT, Steensma HY. The two acetyl-coenzyme A synthetases of Saccharomyces cerevisiae differ with respect to kinetic properties and transcriptional regulation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:28953–28959. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.46.28953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Franken J, Kroppenstedt S, Swiegers JH, Bauer FF. Carnitine and carnitine acetyltransferases in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae: a role for carnitine in stress protection. Curr Genet. 2008;53:347–360. doi: 10.1007/s00294-008-0191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van Roermund CW, Hettema EH, van den Berg M, Tabak HF, Wanders RJ. Molecular characterization of carnitine-dependent transport of acetyl-CoA from peroxisomes to mitochondria in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and identification of a plasma membrane carnitine transporter, Agp2p. EMBO J. 1999;18:5843–5852. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.21.5843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tehlivets O, Scheuringer K, Kohlwein SD. Fatty acid synthesis and elongation in yeast. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 2007;1771:255–270. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vahlensieck HF, Pridzun L, Reichenbach H, Hinnen A. Identification of the yeast ACC1 gene product (acetyl-CoA carboxylase) as the target of the polyketide fungicide soraphen A. Curr Genet. 1994;25:95–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00309532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hofbauer HF, Schopf FH, Schleifer H, Knittelfelder OL, Pieber B, Rechberger GN, Wolinski H, Gaspar ML, Kappe CO, Stadlmann J, Mechtler K, Zenz A, Lohner K, Tehlivets O, Henry SA, Kohlwein SD. Regulation of gene expression through a transcriptional repressor that senses acyl-chain length in membrane phospholipids. Dev Cell. 2014;29:729–739. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Koch B, Schmidt C, Daum G. Storage lipids of yeasts: a survey of nonpolar lipid metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Pichia pastoris, and Yarrowia lipolytica. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2014;38:892–915. doi: 10.1111/1574-6976.12069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Graef M. Lipid droplet-mediated lipid and protein homeostasis in budding yeast. FEBS Lett. 2018;592:1291–1303. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.12996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ren M, Phoon CK, Schlame M. Metabolism and function of mitochondrial cardiolipin. Prog Lipid Res. 2014;55:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Carman GM, Han GS. Regulation of phospholipid synthesis in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Ann Rev Biochem. 2011;80:859–883. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060409-092229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Henry SA, Kohlwein SD, Carman GM. Metabolism and regulation of glycerolipids in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2012;190:317–349. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.130286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]