Abstract

The tissue-specific expression of the Drosophila β2 tubulin gene (B2t) is accomplished by the action of a 14-bp activator element (β2UE1) in combination with certain regulatory elements of the TATA-less, Inr-containing B2t core promoter. We performed an in vivo analysis of the Inr element function in the B2t core promoter using a transgenic approach. Our experiments demonstrate that the Inr element acts as a functional cis-regulatory element in vivo and quantitatively regulates tissue-specific reporter expression in transgenic animals. However, our mutational analysis of the Inr element demonstrates no essential role of the Inr in mediating tissue specificity of the B2t promoter. In addition, a downstream element seems to affect promoter activity in combination with the Inr. In summary, our data show for the first time the functionality of the Inr element in an in vivo background situation in Drosophila.

INTRODUCTION

Tissue-specific gene expression in higher eukaryotes can be accomplished by the recruitment of cell type-specific transcription factors (activators) to distinct promoter/enhancer sequences. The binding of specific activators allows for the interaction with the general transcription initiation machinery at the core promoter and leads to transcriptional activation (1–3). The analysis of core promoter function within transcriptional activation and initiation has led to the identification of relevant cis-acting promoter sequences and their trans-acting counterparts (4–6). The core promoter of genes transcribed by RNA-polymerase II is defined as the minimal sequence surrounding the transcription start site that is capable of initiating accurate basal transcription in vitro. The best characterized core promoter elements are the TATA box at the –25 region and the initiator (Inr) sequence (6–8) encompassing the transcriptional initiation site (9). In addition to core promoters containing one or both of these elements, promoters that lack both elements have been identified. Recently, in Drosophila, an additional 7-bp core promoter element was found ~30 bp downstream of the transcription start site in TATA-less, but Inr-containing, core promoters, termed the DPE (downstream promoter element; 10,11). Functional analysis of these core promoter elements revealed their role in recruiting the TFIID complex for transcriptional start site selection by the binding of different components of the multisubunit TFIID complex to each of these elements. While the TATA box is recognized by the TATA box binding protein (TBP; 12), the Inr and the DPE serve as binding sites for certain TAFs (TBP associated factors; 11,13). In particular, the Inr is thought to function either as a TATA box analog in TATA-less core promoters (6) or as an enhancer of TATA box function in TATA box-containing core promoters (14). It has also been shown that the Inr element serves as a selective determinant for directing promoter accessibility and usage, resulting in differential gene expression (e.g. temporal versus spatial gene expression; 15–18). Additionally, the observation of TAF-mediated direct TFIID recognition of the Inr and sequences located further downstream of the transcription start site (10,17,19–22) stresses the importance of TFIID recruitment to the core promoter as a crucial step for transcription initiation.

Activated gene expression is conferred by the core promoter in conjunction with appropriate transcriptional activator element(s). Interestingly, concerning the mechanism of activated gene expression, it has been shown that TFIID (i.e. certain TAFs) plays a fundamental role in mediating activation of transcription (23,24). In addition, efforts to analyze the regulatory activities of core promoter structure in vivo have been undertaken (25–28). However, currently less is known about the role of core promoter function in mediating tissue-dependent promoter specificity in vivo. While intensive studies address the question of promoter specificity due to different core promoter structures in combination with different activators in vitro (29,30), we examined the properties and dependence of a distinct core promoter architecture for controlling tissue-specific gene expression using the Drosophila β2 tubulin gene promoter in vivo.

The β2 tubulin gene (B2t) encodes a tissue-specific β tubulin variant that is exclusively used during spermatogenesis. The promoter sequence responsible for tissue-specific gene activation is confined to a region of 80 bp sufficient to drive germline specific expression in the testis (31). In addition, a 14-bp activator element (β2UE1) is necessary for promoter specificity (31).

In this paper, we examine the capability of the B2t core promoter, in conjunction with the activator element, to regulate tissue-specific gene expression in vivo using a transgenic system. Reporter analysis of testes from transgenic animals haboring different core promoter constructs reveals that an Inr sequence element at the transcription start site contributes to promoter strength in vivo. However, functional knockout of the Inr sequence does not affect tissue specificity of the B2t promoter suggesting that the β2UE1 activator element is the only element crucial for directing tissue-specific gene activation, while the core promoter architecture defines the B2t promoter strength.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of B2t promoter lacZ reporter constructs

B2t promoter constructs were generated according to the description for the construction of previous B2t-lacZ reporter (31).

P-element mediated germ-line transformation and fly strains

Highly purified plasmid DNA (0.5 mg/ml), along with the presence of the helper plasmid pπ25.7wc (0.25 mg/ml), was injected into the recipient strain w1,snw. A representative β2UE1-hsp70-lacZ strain (hsp70 gene promoter sequence from the chromosomal location 87C contains a TATA-box as well as an Inr-homologous transcription start site followed by an 89-bp untranslated leader region) was compared with a representative B2t-lacZ strain (‘–511’) containing the entire B2t regulatory region. Both strains have been described and established previously (31,32). For comparative whole mount in situ hybridizations to assess β2DE1 activity in vivo (Fig. 5A and B), the transgenic line B2t(–53/+70) (β2DE1-active strain: ‘+β2DE1’) and the transgenic strain B2t(–53/+70)URN, carrying an inverted and therefore inactive β2DE1 (designated ‘–β2DE1’) were used and have already been described (33).

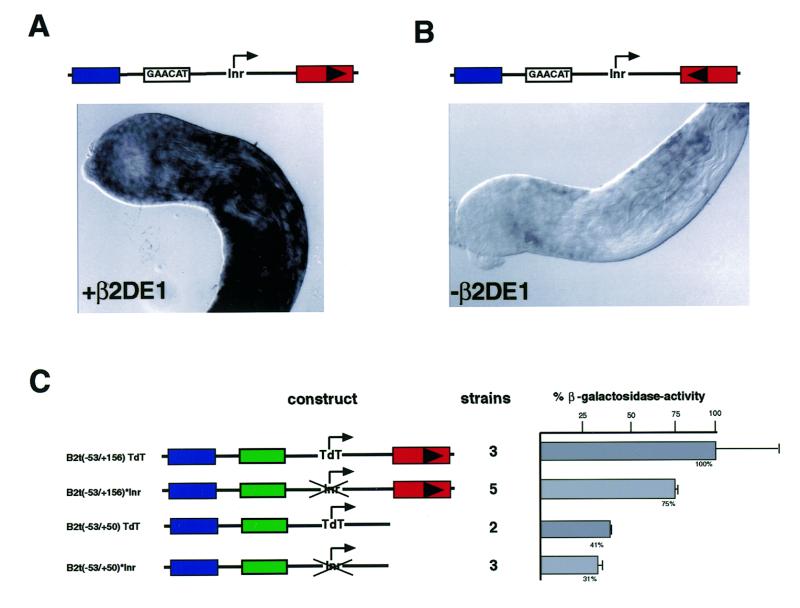

Figure 5.

Regulatory activity of the downstream element, β2DE1. (A and B) In situ hybridization experiments with testes from transgenic flies expressing B2t-lacZ reporter genes containing [(A) β2DE1 in sense orientation, black arrowhead] or lacking [(B) β2DE1 in antisense orientation, inverse black arrowhead] a functional downstream element, β2DE1, reveal differences in the premeiotic lacZ mRNA reporter expression. The apical tips of adult testes are shown, where transcriptionally active cells are located. Side-by-side staining after in situ hybridization with a DIG-labeled lacZ probe shows reduced expression in the strain lacking β2DE1 function (B). (C) The Inr acts independently in combination with the β2DE1 element. Testis-specific β-galactosidase reporter activity was analyzed from different transgenic strains carrying truncated 5′-UTR B2t promoters in combination with different Inr start sites. Removal of the β2DE1 downstream element, in combination with an Inr defective B2t promoter, results in further reduction of reporter expression. Relative reporter expression levels are shown in % β-galactosidase activity (the value of the TdT construct reporter expression was set at 100%).

Whole mount in situ hybridization

Whole mount in situ hybridization of adult testes was performed with digoxygenin-labeled DNA probes (lacZ probe) according to standard protocols (34) with minor modifications. Hybridization was carried out overnight at 45°C. Testis samples of the compared strains were processed in parallel under identical conditions.

Histochemical β-galactosidase staining

For quantitative or comparative histochemical staining analysis, testes of adult males (aged 2–4 days) and larvae from independently transformed reporter lines were stained in side-by-side reactions as previously described (34). Staining was performed at room temperature, monitored every 5 min and stopped by intensive washing with phosphate buffer. After staining, testes were mounted in 50% glycerol and photographed under a Zeiss Axiophot microscope.

Enzymatic β-galactosidase assay (CPRG assay)

Quantification of testis-specific β-galactosidase expression was performed essentially as described by Glaser and Lis (35). Briefly, individual males from lines to be analyzed were outcrossed to the injection stock to generate progeny heterozygous for the P-element. Duplicate sets of five testes from 3–5-day-old males from each outcrossed line were dissected and homogenized in homogenization buffer (35). Testis protein extracts from each transformed line were assayed. The β-galactosidase activity was monitored over a 3-h time period, during which a constant enzyme activity was measured (linear assay). The values for the duplicate samples were averaged. Values are expressed as percentages of the mean level of activity observed for the appropriate control construct. Standard errors of the mean were calculated.

DNA binding assay

For gel-shift experiments, crude testis protein extracts were prepared as follows: testes from 2-day-old healthy males were dissected in ice cold Ringer’s solution and collected in a test tube on ice. After collection, excess buffer was removed and an equal volume of 2× protein extraction buffer (40 mM HEPES pH 7.9, 200 mM KCl, 2 mM DTT, 40% glycerol, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.2% NP-40) was added. The samples were frozen at –80°C over night. After thawing on ice the tissue was homogenized and the extract sonicated for 20 min at 4°C in a sonifier bath (Sonorex TK52, Bandelin). Cell debris was spun down by centrifugation for 10 min at 8000 r.p.m. in a centrifuge (Eppendorf Centrifuge 5314 C). The supernatant was frozen in small aliquots at –80°C. Protein concentrations were determined with the BioRad assay dye. Binding reactions were carried out in a final volume of 20 µl containing 1× binding buffer (10 mM HEPES pH 7.6; 5 mM MgCl2; 50 mM KCl, 0.5 mM DTT, 2.5% glycerol), 1 mg poly-dAdT (Boehringer Mannheim), 15–20 fmol 32P end-labeled, double-stranded oligonucleotides as probe (~3000 c.p.m./fmol), and 10 µg testis protein extract at 18°C for 30 min. For competition experiments, unlabeled oligonucleotides were added to the reaction mixture prior to the addition of probe. Following the binding reaction 5 µl 50% glycerol were added to the samples, which were subsequently resolved on a 6% native polyacrylamide gel (acrylamide to bisacrylamide ratio of 39:1; running buffer: 50 mM Tris, 400 mM glycine) at 180 V and 18°C for 90 min. The gels were dried after electrophoresis and autoradiographed using Kodak X-Omat XR films.

The following DNA oligonucleotides were used (sense strand shown):

B2t(–51/–38): 5′-GGAAATCGTAGTAGCCTAT-3′

B2t(–37/+18): 5′-GATCTGAACATTCGGTGTAGTAATCCAAGCCAGGATCAGTTCCACCTCAGTATCAG-3′

B2t(+39/+86): 5′-CTAGAAAAATCTAAACCTGAAAAATTATACGTTTAAATATTCAGTCTTTTGCCGATTTTC-3′

B2t(–55/–26): 5′-GGAAATCGTAGTAGCCTATTTGTGAACATT-3′ (=comp2 in Fig. 2B)

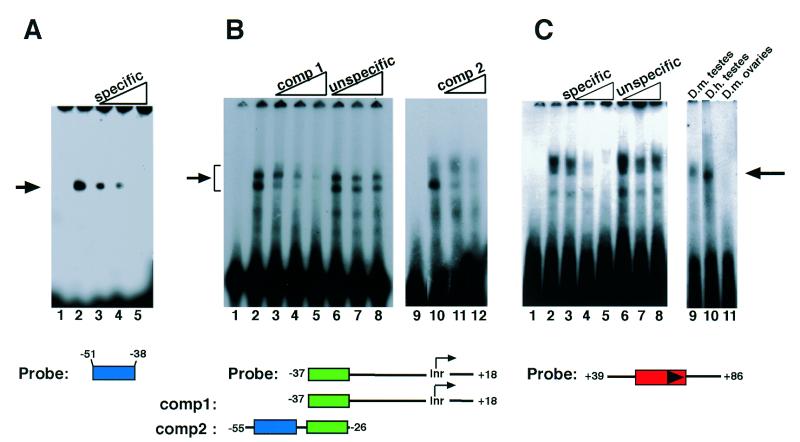

Figure 2.

Gel-shift analysis of the three different functional elements β2UE1, β2UE2 and β2DE1 in the B2t promoter. Three different regions of the B2t promoter were radiolabeled and incubated with Drosophila testis extracts. The specificity of the shifted bands is demonstrated by competition with specific and unspecific competitor sequences as indicated. (A) One specific DNA–protein complex is observed using the β2UE1 activator element as probe (lane 2, arrow; lane 1, free probe; lanes 3–5, unlabeled probe as specific competitor with 5-, 25- and 50-fold molar excess, respectively). (B) The β2UE2 serves as a specific binding site for testicular trans-acting factors. Gel-shift assays were performed with a radiolabeled double-stranded DNA probe encompassing the promoter region from –37 to +18. The binding reaction results in the formation of two prominent DNA–protein complexes (arrowhead, arrow). Competition experiments demonstrate the sequence specificity of the DNA–protein complexes (lanes 3–5, specific competitor ‘comp1’ with 3-, 11- and 30-fold excess; lanes 6–8, unspecific competitor with 26-, 52- and 87-fold excess, respectively). An unlabeled double-stranded oligonucleotide comprising the region from –55 to –26 (‘comp2’) competes out the formation of DNA–protein complex #1 (lanes 11, 12; lane 9, free probe; lane 10, without competitor). The sequence of the competitor overlaps with the sequence of the probe at the β2UE2 as shown below, indicating the presence of the formation of protein–DNA interactions at the β2UE2 element. (C) Testis proteins also interact specifically with the β2DE1 region (arrow). Testes extracts were incubated with a probe comprising the sequence from +39 to +86 (free probe lane 1); lanes 3–5 specific competitor, unlabeled probe sequence with a 2-, 7- and 70-fold molar excess, respectively; lanes 6–8, unspecific competitor (see Materials and Methods) with same molar excess of competitor as lanes 3–5. The major DNA–protein complex in the right panel seems to be specific for testis extracts (D.melanogaster lane 9, D.hydei lane 10) and is absent using ovarian extract (lane 11).

unspecific competitor: 5′-AGCTGCGACTATCGCGATCCTCAGTCGACGTCTAGACTGAAGATGA-3′ (see Fig. 2B)

unspecific competitor (derived from the B1t upstream region; see Fig. 2C): 5′- GTATGGCCACACTGCGGCCATCG-3′.

RESULTS

The TATA-less testis-specific B2t promoter of Drosophila contains a conserved initiator sequence (Inr)

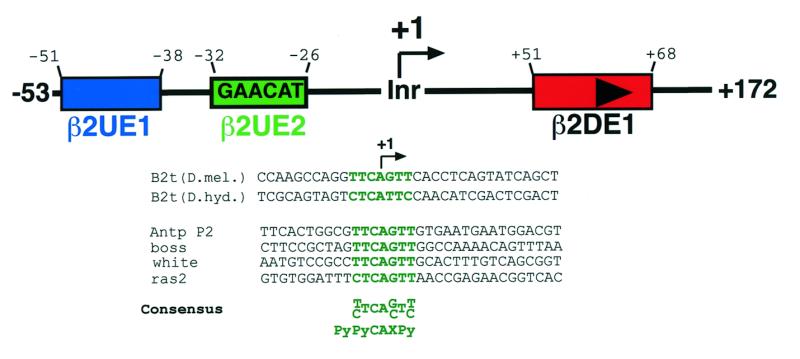

In vivo transcriptional analysis of the B2t promoter region resulted in the identification of the cis-regulatory elements responsible for driving tissue-specific B2t gene expression (31–33). Figure 1 depicts the overall structure of the B2t promoter and its associated regulatory elements. Within the promoter, three major cis elements have been identified: the 14-bp activator element, β2UE1, which is necessary for cell type-specific gene activation, and two quantitative regulatory elements called β2UE2 at the –25 region and β2DE1 in the +60 region. The B2t core promoter does not contain a TATA box in the –25 region. Instead, β2UE2(GAACAT), a sequence element that is conserved between Drosophila melanogaster and Drosophila hydei and exhibits regulatory capability, is located in that region (31). However, the transcription start site which is also involved in B2t gene regulation (32), represents a consensus Inr sequence (PyPyCAXPy) observed in many TATA-less promoters (Fig. 1, highlighted in green; 10). Therefore, we decided to use the testis-specific B2t promoter as an experimental model to elucidate the Inr function in vivo.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the structure of the Drosophila testis-specifc B2t promoter and showing a potential Inr element. The B2t promoter region consists of at least three regulatory elements (β2UE1, blue box; β2UE2, green box; β2DE1, red box with arrowhead) (31–33). A sequence comparison with known initiator-containing Drosophila core promoters and the B2t promoter of D.hydei and D.melanogaster reveals a highly conserved Inr element overlapping the start site [sequence highlighted in green; adapted from Burke and Kadonaga (10)].

All three identified regulatory elements in the B2t promoter serve as binding sites for DNA binding proteins

To further characterize the defined B2t promoter elements, we performed gel electrophoretic mobility shift experiments to prove the existence of specific DNA–protein interactions. Incubation of crude Drosophila testis extracts with radiolabeled, double-stranded oligonucleotides representing the three major regulatory elements resulted in the formation of sequence-specific DNA–protein complexes (Fig. 2A–C). Using β2UE1 as a probe, a single, sequence-specific DNA protein complex is observed (Fig. 2A). The β2UE2 element also represents a binding site for testicular DNA binding proteins as demonstrated in competition gel shift assays (Fig. 2B). Radiolabeled, double-stranded oligonucleotides representing the core promoter region from –37 to +18 are recognized by DNA binding proteins from testes extracts (Fig. 2), resulting in the formation of retarding DNA–protein complexes (Fig. 2B). Competition experiments with unlabeled competitor DNA, whose sequence of which overlaps the region of the probe at β2UE2, results in specific competition of the complex.

Finally, to determine if the downstream region of the B2t gene harboring the β2DE1 regulatory element might serve as a protein-binding site, gel-shift analysis was carried out with crude testis protein extracts in the presence of a probe containing the β2DE1 sequence. The experiment revealed the formation of one dominant retarding DNA–protein complex (Fig. 2C, left panel). Competition experiments with three different competitors (for origin and sequence see Materials and Methods) clearly demonstrate the sequence specificity of the retarding DNA–protein complex. We extended the gel shift analysis by using protein extracts derived from adult testes of D.hydei and ovaries from D.melanogaster, respectively. Figure 2C shows the result of this band shift experiment. The same probe binds also to testes proteins from D.hydei, but fails to generate any DNA–protein interactions with proteins from ovaries. Binding assays with a probe comprised solely of the sequence of the β2DE1 (+49 to +72) using testis extracts from D.melanogaster confirmed the existence of a DNA-binding protein specific for this sequence element (data not shown). Since the β2DE1 element is conserved in sequence and position in the B2t gene of both Drosophila species, we presume that the β2DE1 represents a DNA-binding site for a testis-specific DNA-binding protein, which might be involved in transcriptional regulation.

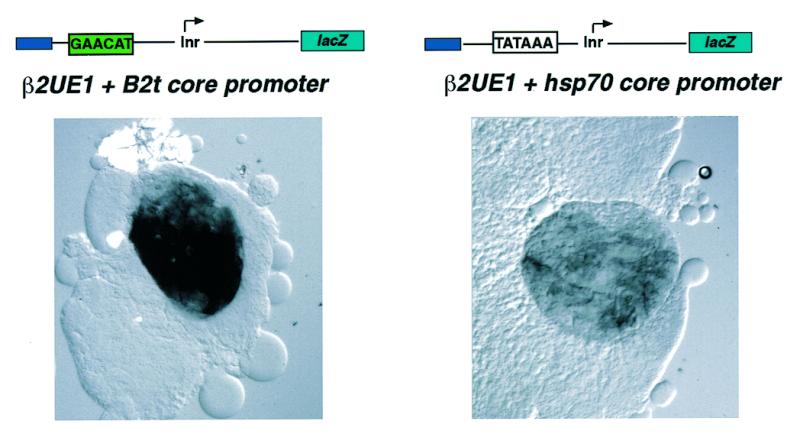

The combination of a heterologous TATA containing core promoter (hsp70) with the β2UE1 activator element decreases promoter strength but has no influence on tissue specificity in vivo

In order to investigate the influence of the core promoter on the strength of the B2t promoter we substituted the B2t core promoter for the hsp70 core promoter. As shown in Figure 3, reporter gene expression was analyzed qualitatively in larval testes (which contain only transcriptionally active germ cells) derived from transgenic animals carrying either reporter constructs containing the B2t core promoter or a reporter construct containing the hsp70 core promoter, in combination with the β2UE1 activator element. Surprisingly, the β2UE1 activator element does not work efficiently in the context of the hsp70 core promoter, which carries a TATA-box in the –25 region compared to the TATA-less B2t core promoter. Therefore, the β2UE1 activator element requires an Inr-containing, but TATA-less, core promoter to achieve its maximal activity. Taken together, these data suggest that certain transcriptional activation depends on a specific core promoter architecture to activate transcription in vivo. To address the question whether the Inr is required for activator mediated tissue-specificity, we set out to analyze a non-functional Inr element in this promoter context in vivo.

Figure 3.

Substitution of the B2t core promoter for the hsp70 core promoter decreases promoter strength but not tissue specificity in vivo. Larval testes (containing only transcriptionally active cells) of representative corresponding transgenic fly strains [see Michiels et al. (32)] were analyzed histochemically for β-galactosidase reporter expression. The presence of the TATA-containing hsp70 core promoter in combination with the β2UE1-activator element results in a decrease of reporter activity.

The Inr element is functionally active, but not necessary to confer tissue-specific gene expression

In vitro transcription analysis of synthetic promoters has revealed the relevant nucleotides within an Inr consensus element that are critical for Inr activity. Replacement of a C by a G at position –1, or a T by a G at +3, abolishes any transcriptional activity of Inr containing promoter templates in vitro (8,20,36). Thus, we examined the relevance of these two nucleotides in vivo in the context of the B2t promoter.

B2t-promoter lacZ constructs carrying mutations at these nucleotide positions were generated [Fig. 4A, construct B2t(–53/ +156): wild type; B2t(–53/+156)*Inr: mutated Inr], introduced into the Drosophila genome by P-element mediated transformation and transgenic fly lines established. As a further positive control, in addition to the B2t wild type promoter construct, a construct was generated with 10 bp of the murine TdT (terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase) transcription start site, representing a functional Inr sequence (6), in place of the endogenous B2t start (Fig. 4A, B2t-TdT). Tissue-specific promoter activity was monitored by histochemical β-galactosidase staining of testes from different transgenic lines (Fig. 4B). The stainings revealed that each tested B2t promoter variant is capable of driving reporter gene expression in the male germ line in the B2t pattern.

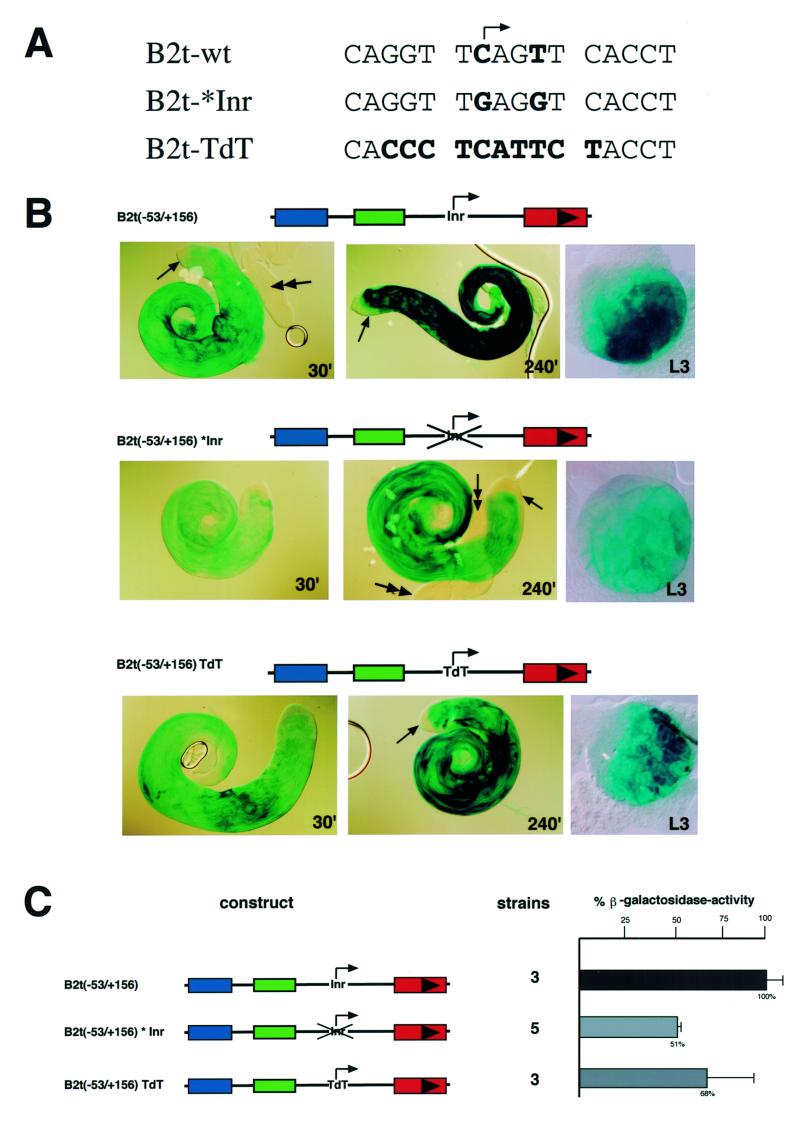

Figure 4.

In vivo analysis of Inr function in tissue-specific B2t gene regulation. (A) Inr-sequences used in the B2t promoter background for reporter expression analysis in the transgenic fly system. (B) β-galactosidase reporter expression of corresponding B2t–Inr constructs. Expression was analyzed by histochemical X-Gal staining of adult testes and monitored after 30 min (left panels) and 240 min (middle panels), respectively. In addition, stainings of corresponding larval testes which contain only premeiotic, transcriptionally active germ cells are shown (right panels). In each case the activator element is able to drive testis-specific reporter expression. However, differences in the staining intensity are evident. The construct carrying the mutated Inr (middle panels) shows a weaker staining in comparison to the wild type (upper panels) and also in comparison to the construct with the TdT–Inr region (lower panels), indicating a regulatory effect of the Inr element. (C) β-galactosidase enzyme activity assays confirm the quantitative function of the Inr element. Mutation of the relevant Inr base pairs leads to 50% reduction in reporter expression.

All constructs show correct temporal and spatial reporter expression. Consequently, β-galactosidase staining is exclusively present in male germ-cells from late spermatocytes onwards. No reporter expression is seen in early germ cells (Fig. 4B, arrows) or somatic genital tissues like paragonia (Fig. 4B, double arrow). However, differences in the staining intensity were observed between these constructs. While the B2t(–53/ +156)TdT construct shows nearly the same staining intensity as the wild type construct, the construct carrying the mutated Inr sequence clearly exhibits reduced staining intensity. Staining of corresponding larval testes containing solely transcriptionally active cells reflects the same relative reporter expression levels, indicating the influence of changed start sites on transcriptional regulation (Fig. 4B, right panels). In order to confirm these qualitative results and to consider effects of chromosomal position of the insertion sites, we attempted to analyze the expression quantitatively in multiple lines. The qualitatively observed differences in the reporter expression are underscored by the quantitative measurement of β-galactosidase activity in testis extracts derived from multiple independent strains (Fig. 4C, the number of strains are indicated).

Mutation of the Inr element at the B2t transcription start site results in a decrease of ~50% in β-galactosidase activity relative to the reporter activity for wild type constructs and ~25% relative to the observed activity in the constructs with functional TdT–Inr. However, the results with the TdT–Inr construct are difficult to interpret because of higher variability between the measured strains (see standard deviation, Fig. 4C). The difference in β-galactosidase activity between wild type and TdT–Inr suggests that the additional base pairs surrounding the Inr might participate in promoter function. In summary, this experiment demonstrates that removal of the relevant Inr base pairs within the B2t start site has no effect on the tissue-specificity of the promoter but leads to a decrease of promoter strength. The result further implies that the Inr element is functional in determining expression level of the reporter gene in vivo.

The β2DE1 downstream element supports promoter strength, but is not dependent on the presence of the Inr

Initial investigations of the B2t promoter structure reveal the presence of a conserved AT-rich regulatory element, β2DE1, located downstream of the transcription start site in the 5′-UTR (+60 region). It has been proposed that this element regulates mRNA levels during post-meiotic stages of spermatogenesis, probably by conferring stability on the B2t mRNA (33). It has become increasingly evident that downstream elements are also involved in transcriptional regulation and significantly contribute to Inr function in TATA-less promoters (10,11,37–42). To investigate this with respect to the β2DE1 we first examined the lacZ mRNA levels by in situ hybridization in adult testes of transgenic animals bearing either a B2t-wild type reporter construct containing the β2DE1 element (denoted as +β2DE1; Fig. 5A) or a promoter-lacZ construct lacking a functional β2DE1 (–β2DE1; construct carries inverted β2DE1 element; Fig. 5B; for fly strains see Materials and Methods). It has been shown previously by a comparative S1 nuclease-quantification assay that deletion of the β2DE1 element gives rise to a 3-fold reduction in the amount of lacZ mRNA (33). Comparison of the relative staining intensities after equivalent hybridization reflects the difference in the lacZ mRNA levels measured in vitro by the S1 nuclease quantification assay (Fig. 5A and B). The lacZ mRNA level seems to be reduced already in primary spermatocytes (Fig. 5B). This cell type is characterized by its high transcriptional activity. Thus, we verified the difference in mRNA levels measured in vitro by an in vivo approach, showing the reduction in lacZ mRNA directly on the cellular level. To show the regulatory activity of the β2DE1 region in combination with Inr function in vivo we generated transgenic flies carrying truncated B2t-promoter constructs (+50 instead of +156: removal of the β2DE1 region) in conjunction with either a TdT–Inr or mutated/inactivated B2t–Inr as described above [constructs B2t(–53/+50)TdT, B2t(–53/+50)*Inr]. Analysis of β-galactosidase activity in these strains revealed that each promoter is still capable of directing testis-specific gene expression; however, an additional reduction in reporter gene activity between constructs with or without β2DE1 region becomes evident (Fig. 5C). The expression level between the constructs with mutated Inr elements in comparison to the constructs bearing the TdT–Inr in the presence and absence of the β2DE1 differs in the same relative ratio to each other. The presence of a mutated Inr gives rise to an additional 25% reduction of β-galactosidase activity in comparison to the constructs carrying the TdT–Inr. Hence, the analysis of these constructs supports the described Inr activity. However both elements seem to act independently of each other in quantitatively regulating reporter gene expression.

DISCUSSION

In this report, we show the regulatory capability of an Inr element during tissue-specific gene expression in vivo using the well-characterized Drosophila β2 tubulin gene promoter (B2t). This promoter contains an indispensable activator element (β2UE1) and an Inr element, but lacks a TATA box. We tested the regulatory capacity of the Inr sequence in vivo by analyzing reporter gene expression from different B2t promoter-lacZ fusion constructs in testes of transgenic animals. We showed that the activator element, in combination with an Inr-defective core promoter, is still capable of driving testis-specific reporter expression in vivo. However, mutation of the nucleotides essential for Inr activity in vitro (19,29,36) results in a decrease of reporter expression, suggesting that the Inr serves as a quantitative regulatory element to maintain high expression levels, but seems not to be required for tissue-specific gene expression of the B2t gene. The TdT–Inr, when substituted for the B2t–Inr sequence, is not able to restore promoter activity completely. This finding is consistent with in vitro transcriptional analysis of the TdT–Inr sequence showing that mutations adjacent to the start site affect expression, but not as severely as mutation of the base pairs crucial for Inr activity (8). In summary, we conclude that the Inr element represents a regulatory element that improves promoter strength during tissue-specific B2t gene activation in vivo.

It has been shown previously that the Inr can functionally replace a TATA box and can improve gene expression in conjunction with a TATA box (6,14). However, the presence of a TATA box cannot replace the B2t core promoter function, suggesting an additional function of the Inr other than solely being a TATA analog. Consequently, our data support the idea of a distinct role of the Inr in mediating transcriptional activation, which is specific for certain core promoters. For example, it has been demonstrated that the activation domains of VP16 and Sp1 have different transcriptional effects in combination with distinct core promoters (29).

In addition, our functional in vivo analysis of Inr activity revealed that two base pairs (at positions –1 and +3) affect normal reporter gene expression levels. However, the effect of these point mutations are not as dramatic as the results reported by Smale and coworkers (8,29,36), which are based on in vitro transcription experiments using a large series of Inr mutations. The experiment using the TdT–Inr sequence in place of the B2t sequence suggests that the sequence in the vicinity of the start site also participates in this process. Interestingly, a more recent report by Chalkley and Verrijzer (43) demonstrates that it is not just the Inr sequence that is recognized by a TAFII250–TAFII150 complex, but that in addition the DNA structure is essential for the recognition process.

In summary, analysis of the B2t promoter in directing tissue-specific expression has shown that all these cis-regulatory elements are confined to a region of ~80 bp. Within that region, there is a 14-bp activator element, β2UE1, which is required for testis-specific B2t gene expression. This element is the only element necessary for tissue-specific initiation of transcription, while the other elements of the core promoter and leader are not critical for tissue-specific initiation. However, these elements are contributing to the level of gene expression. Due to the crucial role of the β2UE1 activator element, we propose a two-step model. In the initial step, a tissue/testis-specific activator opens the structure of the chromatin. In the second step the TFIID complex is recruited to the now accessible core promoter. The overall gene expression level can be modulated by the affinity of TFIID for the core promoter.

Previous analysis has implicated the downstream located β2DE1 implicated to have a functional role in post-transcriptional regulation, namely mRNA stability. Our additional characterization showed that the β2DE1 element has an influence on the premeiotic mRNA-level in highly transcriptionally active spermatocytes. Thus, we conclude that the β2DE1-downstream element might also contribute to transcriptional regulation in addition to its proposed post-transcriptional function. This conclusion is supported by the observation that the downstream promoter region represents a binding site for testis-specific factors. Interestingly, members of the Drosophila Mst(3)CGP gene family, which like the B2t gene are exclusively expressed in male germ-cells, carry a conserved regulatory element (TCE) in the 5′-UTR which confers translational control and also has been implicated to function on the transcriptional level (44). Therefore, the regulatory elements within the 5′-UTR of these genes may exhibit a dual function on the transcriptional as well as post-transcriptional level. This aspect is very conceivable, since all testis-specific promoters identified so far have an extremely short regulatory region, which is capable of driving gene expression in the complex developmental context of spermatogenesis.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Charlene Y. Kon, Matthias Kämpfer and John P. Mills are gratefully acknowledged for discussion and critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Re628/9-1 and Re628/9-2) and the Fond der Chemischen Industrie to R.R.-P.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tjian R. and Maniatis,T. (1994) Cell, 77, 5–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ranish J.A. and Hahn,S. (1996) Curr. Opin. Gen. Dev., 6, 151–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berk A.J. (1999) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol., 11, 330–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orphanides G., Lagrange,T. and Reinberg,D. (1996) Genes Dev., 10, 2657–2683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roeder R.G. (1996) Trends Biochem. Sci., 21, 327–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smale S.T. (1997) Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1351, 73–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cherbas L. and Cherbas,P. (1993) Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol., 23, 81–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lo K. and Smale,S.T. (1996) Gene, 182, 13–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smale S.T. and Baltimore,D. (1989) Cell, 57, 103–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burke T.W. and Kadonaga,J.T. (1996) Genes Dev., 10, 711–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burke T.W. and Kadonaga,J.T. (1997) Genes Dev., 11, 3020–3031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hernandez N. (1993) Genes Dev., 7, 1291–1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tansey W.P. and Herr,W. (1997) Cell, 88, 729–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Colgan J. and Manley,J.L. (1995) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 92, 1955–1959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hansen S.K. and Tjian,R. (1995) Cell, 82, 565–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwyter D.H., Huang,J.-D., Dubnicoff,T. and Courey,A.J. (1995) Mol. Cell. Biol., 15, 3960–3968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verrijzer C.P., Chen,J.-L., Yokomori,K. and Tjian,R. (1995) Cell, 81, 1115–1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Verrijzer C.P. and Tjian,R. (1996) Trends Biochem. Sci., 21, 338–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaufmann J. and Smale,S.T. (1994) Genes Dev., 8, 821–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaufmann J., Verrijzer,C.P., Shao,J. and Smale,S.T. (1996) Genes Dev., 10, 873–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Purnell B.A., Emanuel,P.A. and Gilmour,D.S. (1994) Genes Dev., 8, 830–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sypes M.A. and Gilmour,D.S. (1994) Nucleic Acids Res., 22, 807–814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sauer F., Hansen,S.K. and Tjian,R. (1995) Science, 270, 1783–1788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sauer F., Hansen,S.K. and Tjian,R. (1995) Science, 270, 1825–1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pham A.D., Müller,S. and Sauer,F. (1999) Mech. Dev., 84, 3–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shopland L.S., Hirayoshi,K., Fernandes,M. and Lis,J.T. (1995) Genes Dev., 9, 2756–2769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ohtsuki S., Levine,M. and Cai,H.N. (1998) Genes Dev., 12, 547–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ren B. and Maniatis,T. (1998) EMBO J., 17, 1076–1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Emami K.H., Navarre,W.W. and Smale,S.T. (1995) Mol. Cell. Biol., 15, 5906–5916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garraway I.P., Semple,K. and Smale,S.T. (1996) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 4336–4341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Michiels F., Gasch,A., Kaltschmidt,B. and Renkawitz-Pohl,R. (1989) EMBO J., 8, 1559–1565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Michiels F., Wolk,A. and Renkawitz-Pohl,R. (1991) Nucleic Acids Res., 19, 4515–4521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Michiels F., Buttgereit,D. and Renkawitz-Pohl,R. (1993) Eur. J. Cell Biol., 62, 66–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Santel A., Winhauer,T., Blümer,N. and Renkawitz-Pohl,R. (1997) Mech. Dev., 64, 19–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Glaser R.L. and Lis,J.T. (1990) Mol. Cell. Biol., 10, 131–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Javahery R., Khachi,K., Lo,K., Zenzie-Gregory,B. and Smale,S.T. (1994) Mol. Cell. Biol., 14, 116–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jarrell K.A. and Meselson,M. (1991) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 88, 102–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arkhipova I.R. and Ilyin,Y. (1991) EMBO J., 10, 1169–1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McLean C., Bucheton,A. and Finnegan,D.J. (1993) Mol. Cell. Biol., 13, 1042–1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fridell Y.-W.C. and Searles,L.L. (1992) Mol. Cell. Biol., 12, 4571–4577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Minchiotti G., Contursi,C. and Di Nocera,P.P. (1997) J. Mol. Biol., 267, 37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pelletier M.R., Hatada,E.N., Scholz,G. and Scheidereit,C. (1997) Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 3995–4003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chalkley G.E. and Verrijzer,C.P. (1999) EMBO J., 18, 4835–4845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kempe E., Muhs,B. and Schäfer,M. (1993) Dev. Genet., 14, 449–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]