Abstract

Estrogen is the major female hormone involved in reproductive functions, but it also exerts a variety of additional roles in non-reproductive organs. In this review, we highlight the preclinical and clinical studies that have pointed out sex differences and estrogenic influence on audition. We also describe the experimental evidences supporting a protective role of estrogen towards acquired forms of hearing loss. Although a high level of endogenous estrogen is associated with a better hearing function, hormonal treatments at menopause have provided contradictory outcomes. The various factors that are likely to explain these discrepancies include the treatment regimen as well as the hormonal status and responsiveness of the patients. The complexity of estrogen signaling is being untangled and many downstream effectors of its genomic and non-genomic actions have been identified in other systems. Based on these advances and on the common physio-pathological events that underlie age-related, drug or noise-induced hearing loss, we discuss potential mechanisms for their protective actions in the cochlea.

Keywords: Estradiol, Steroid, Cochlea, Deafness, Otoprotection, Neuroprotection, Sexual dimorphism

Introduction

Hearing loss is the most frequent sensory disorder as it affects over 5% of the worldwide population. In addition to genetic factors, the most common causes include normal aging, exposure to excessive noise and treatment with ototoxic drugs such as aminoglycosides or cisplatin [1]. Increasing noise levels associated with environmental and recreational activities are likely to cause a substantial rise in the incidence of deafness over the next decades. The economic and social consequences of disabling hearing impairment are considerable, as it causes a severe handicap by allocating the development of oral communication in childhood and induces a tendency to withdrawal into isolation, exclusion and depression in adulthood [2]. In elderly, mild hearing loss is frequently associated with cognitive decline and dementia [3, 4]. Taken together, the global burden of hearing impairment constitutes a major health issue.

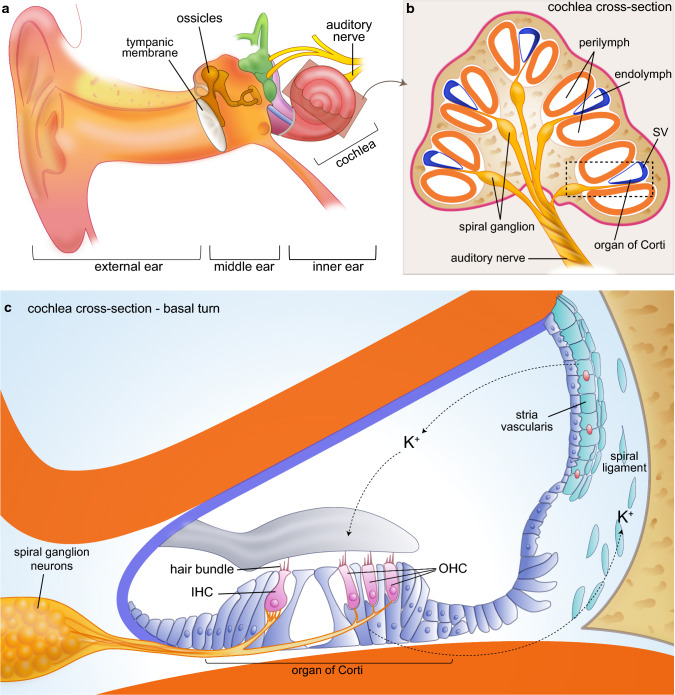

Hearing loss can be classified into conductive or sensorineural, according to the mechanisms involved. Conductive hearing loss occurs when the transmission of sound wave is reduced or blocked in the ear canal or the middle ear (Fig. 1a). In many cases, this represents a transient disability as it may be managed by pharmacological treatment or surgery. Sensorineural hearing loss is the most common form of hearing loss and is caused following damage to the cochlea—the auditory portion of the inner ear (Fig. 1b). The cochlea is a spiraled tube whose central chamber is filled with a potassium-enriched fluid (the endolymph) and is lined by a sensory epithelium called the organ of Corti and a secretory epithelium, called the stria vascularis. The organ of Corti contains four rows of sensory hair cells (HCs) that detect sound wave upon deflection of their apical hair bundle (Fig. 1c). Whereas the single row of inner HCs (IHCs) is the principal decoder of sound, the three rows of outer HCs (OHCs) play an essential role for cochlear amplification. Upon sound-evoked stimulation, glutamate is released from the IHCs and this neurotransmitter stimulates the afferent spiral ganglion neurons (SGNs) that will convey the acoustic information towards the auditory cortex through various neuronal relays. The stria vascularis, located in the lateral wall of the cochlear duct, houses cells that produce the endolymph and control its unusual ionic composition, which is critical for audition (Fig. 1c).

Fig. 1.

The peripheral auditory system. a The ear is composed of the external, the middle and the inner ear, whose ventral portion is the cochlea, dedicated to hearing. After travelling through the ear canal, the sound wave hits the tympanic membrane and the sound-induced vibration is amplified by the movement of the ossicles and transmitted to the cochlea. b The cochlea is a coiled tube composed of three chambers. The central cochlear duct (in blue) is filled with a K+-enriched fluid called the endolymph while the surrounding chambers contain perilymph. c The organ of Corti (OC) comprises one row of inner hair cells (IHCs), which are the principal decoders of sound and three rows of outer hair cells (OHCs) responsible for cochlear amplification. These cells harbor a mechano-sensitive hair bundle whose deflection induce an inward K+ current followed by a release of glutamate that activates the innervating spiral ganglion neurons (SGNs). The sound signal is then transmitted through various neuronal relays up to the auditory cortex. The lateral wall of the cochlear duct comprises the vascularized stria vascularis (SV) that secretes K+ and produces the endolymph and the spiral ligament responsible of ion recycling

In humans, damage to the sensory HCs, to their innervating SGNs or to the stria vascularis are irreversible and result in permanent sensorineural hearing loss. Currently, only sound amplification through hearing aids or electric stimulation through cochlear implants can be proposed to patients. Therefore, many efforts are dedicated to identify new therapeutic agents that would prevent or halt the progressive degeneration of those cells. Among those, estrogen is an interesting candidate.

In this review, we summarize the knowledge related to estrogen signaling and function in hearing as well as several studies supporting their otoprotective roles. In addition, we present hypotheses regarding their protective molecular mechanisms representing future avenues of research towards hearing loss treatment.

Estrogen signaling

Estrogen ligands

Estrogen is a steroid hormone synthesized from cholesterol that primarily promotes the development, maturation and function of the female reproductive tract and secondary sexual characteristics [5]. Natural estrogen consists in a group of four distinct forms that includes estrone (E1), estradiol (E2), estriol (E3) and estetrol (E4). E2 is the most potent and abundant endogenous estrogen during the premenopausal period and is, thus, considered as the reference estrogen. E1 is the predominant circulating estrogen after menopause whereas E3 and E4 are detected at high levels only during pregnancy, the latter being produced exclusively by the fetus.

Estrogen is mainly produced by the ovaries, but also comes from extra-gonadal sites such as the adipose tissue, bone, heart, skin and brain [5]. In those tissues of both males and females, E2 is produced by androgen conversion through the enzymatic activity of aromatase. This local synthesis contributes to various tissue-specific actions of estrogen, such as its beneficial effects on bone homeostasis and cardiovascular function or neuroprotection against brain injury and degenerative diseases [6]. The auditory cortex expresses the aromatase enzyme and is, thus, responsible for a local production of E2 that influences the central auditory processing [7]. This neuromodulatory effect of E2 has been extensively studied in vocal fishes and birds and we refer the reader to excellent reviews on this topic [8–10], as it will not be presented here. In the peripheral auditory organ, aromatase has been detected in the auditory nerve ganglion cells of teleost fish [11], so it should be kept in mind that peripheral sources of E2 could, in addition to systemic E2, play a role on the cochlear function.

Estrogen receptors

Estrogen actions are mediated by three specific receptors: estrogen receptor alpha (ERα), estrogen receptor beta (ERβ) and G protein-coupled estrogen receptor (GPER, also called GPR30). Moreover, estrogen signaling may be divided into two main pathways: genomic and non-genomic.

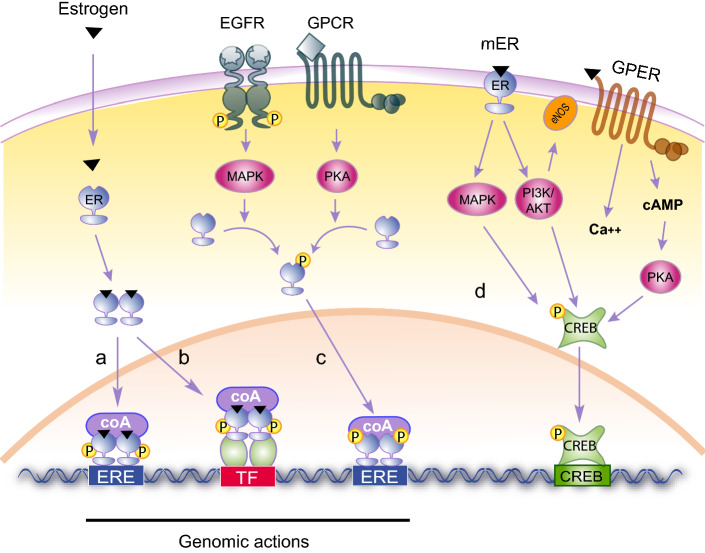

In the genomic pathway, activated ERα and ERβ act as transcription factors that regulate gene expression through specific sequences present in the promoter of target genes [12]. In the classical genomic pathway (Fig. 2a), estrogen diffuses through the plasma membrane to bind cytoplasmic ERα and ERβ that homo- or hetero-dimerize, translocate to the nucleus and recognize DNA sequences called estrogen response elements (EREs). Estrogen-bound ERs can also be indirectly recruited to DNA through their association with other transcription factors (TF) such as AP-1, SP1 or NF-kB, which are bound to their cognate response elements (ERE independent, Fig. 2b). Finally, ERE-containing genes may be regulated in the absence of estrogen (ligand independent, Fig. 2c). In this case, unbound ERs are phosphorylated downstream of tyrosine kinase or G protein-coupled receptors activation, resulting in conformational changes that allow them to bind their consensus sequences and modulate transcription. The non-genomic pathway involves membrane-anchored ERα, ERβ or GPER [13, 14] and therefore is also known as the membrane-initiated steroid signaling (MISS). This pathway leads to the rapid activation, within seconds or minutes, of cytoplasmic kinases and ion channels (Fig. 2d). This mode of action is referred as “non-genomic” since it does not rely on the modulation of gene expression but rather on the regulation of protein activity. However, the rapid modulation of signaling kinases and calcium fluxes will ultimately regulate downstream transcription factors such as CREB (c-AMP response element binding protein), and thus secondarily impact, after a few hours or days, transcriptional programs.

Fig. 2.

Estrogen signaling. a Estrogen diffuses through the plasma membrane and binds to ERα or ERβ that dimerize and translocate to the nucleus. ERs bind ERE sequences, recruit coactivators (coA) and transactivate their target genes (classical genomic action). b Estrogen-bound ERs may also interact with other transcription factors (TF) such as AP1, SP1 and NF-κB, and regulate their transactivation potential (ERE-independent genomic action). c The activation of tyrosine kinase receptors (i.e. EGFR) and G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) lead to the activation of MAPK and PKA, which phosphorylate ER and allow it to regulate ERE-containing genes in the absence of estrogen (ligand-independent genomic action). d Membrane-initiated signaling (MISS) occurs through estrogen binding to a membrane-anchored ERα, ERβ or GPER and leads to a rapid activation of various kinase cascades modulating the activity of enzymes and ion channels (non-genomic action). Amongst the phosphorylated targets, transcription factors such as CREB (c-AMP response element-binding protein) will, in a longer time frame, result in gene expression changes

Estrogen receptors in the cochlea

In the cochlea, ERα has been detected in the nucleus of HCs, SGNs and strial cells [15–17]. The pattern of expression of ERβ remains controversial. While some studies report the presence of ERβ protein in all ERα-positive cochlear cells [15–18], others did not detect it in the stria vascularis [19]. Recently, reassessment of numerous anti-ERβ antibodies previously used in the literature showed that they have been insufficiently validated and therefore questioned their specificity and the validity of previous results [20, 21]. Besides the classical ERs, the cochlear distribution of GPER protein has not been investigated by immunohistochemistry but its transcript has been detected in the adult mouse. According to mRNAs levels, GPER would even be, in the cochlea, the most abundant of all three receptors [22]. In addition, a cell type-specific RNA-sequencing performed early during mouse cochlear development suggests that GPER is enriched in cells surrounding the HCs, namely the supporting cells, which provide structural and trophic support to their neighbours [23]. Whether GPER RNA and protein levels are correlated in the cochlear tissue is not yet known.

Endogenous estrogen level and hearing

Estrogen synthesis varies according to the sex, the age and the hormonal status. While the production of estrogen is rather low and consistent in men, the level of estrogen synthesis in women reaches a peak during the reproductive years, fluctuates during the menstrual cycle and then progressively declines at menopause [24]. This hormonal fluctuation is a unique opportunity to address the role of estrogen on hearing.

The estrogenic influence on hearing function

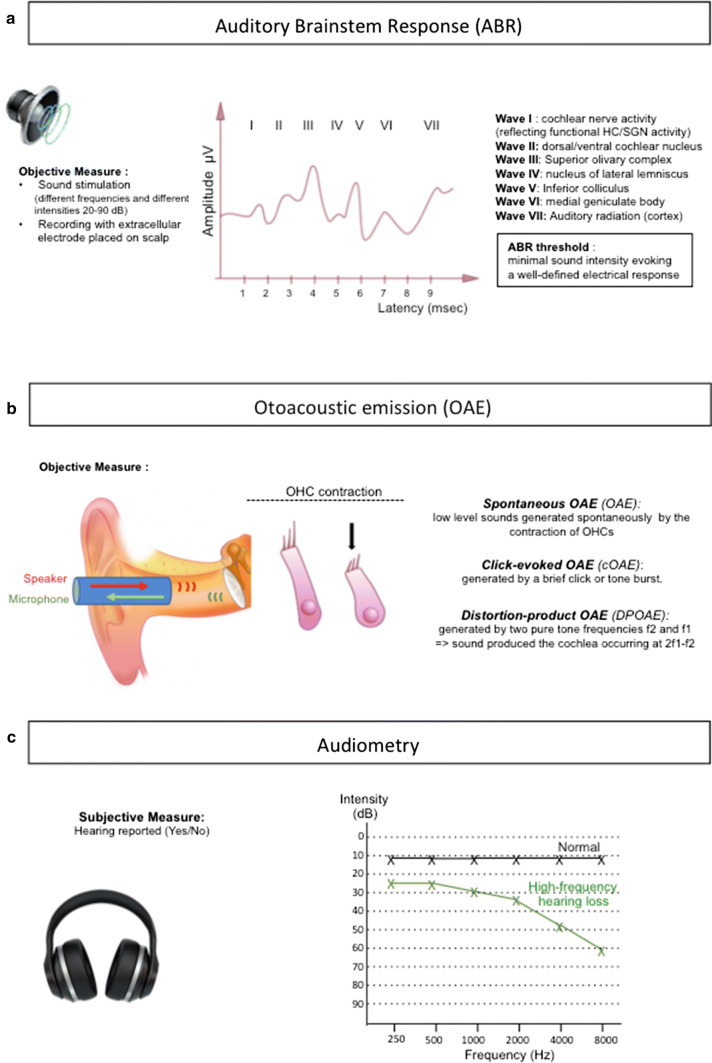

Sex differences in audition have long been reported and are consistently demonstrated in recent comparative studies (Table 1). The measure of auditory brainstem response (ABR), which records the electrical potentials issued by a group of neurons in response to sound (Fig. 3), indicates that women present increased peak amplitudes and reduced latencies compared to men, suggesting a higher sensitivity and an increased transmission speed, respectively [25–27]. The cochlear function, reflected by the capacity of OHCs to contract and emit low-intensity sounds named otoacoustic emissions (OAEs), also varies with sex. Indeed, women display elevated frequencies and amplitudes of spontaneous or click-evoked OAEs, indicating an increased cochlear sensitivity [28, 29]. Audiometric comparisons, which are based on the subjective determination of sound perception (Fig. 3) and can be conducted on larger cohorts, show that women have a lower hearing threshold and thus an increased sensitivity compared to men [30–33]. Whether these sex differences can be attributed solely to estrogen is unclear; however, fluctuating levels of estrogen in females during menstrual cycle are associated with intra-individual variabilities in the auditory function. During the peri-ovular phase, characterized by the highest estrogen level, DPOAEs amplitudes are larger [34] and ABR wave latencies are shorter than during the luteal and follicular phases [35, 36] Moreover, ABR wave latencies increase while amplitudes decrease in aging women, along with the decline of estrogen production by the ovaries [27]. Finally the hearing sensitivity, in postmenopausal women, is correlated with the level of serum E2, further emphasizing the influence of estrogen on the auditory function [37].

Table 1.

Sex differences in hearing

| Study | Subjects | Hearing test | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| [26] | 182 women | ABR | Shorter wave V latency in women |

| 137 men | Larger wave V amplitude in women at all ages (25–55 years) | ||

| [25] | 10 young women | ABR | Shorter latencies in women |

| 10 young men | Greater amplitudes in women | ||

| [27] | 19–25/50–70 year old subjects | ABR | Shorter interpeak intervals I–V in women |

| 20 women | Greater wave V amplitude in women | ||

| 20 men | Longer wave latencies in old subjects compared to young ones (for both sex) | ||

| Changes in wave V latency as a function of age is larger for women | |||

| [28] | 56 women | SOAEs | Increased prevalence of SOAEs in women compared to men |

| 75 men | |||

| [29] | 125 women | CEOAEs | Larger CEOAE waveform in women compared to men |

| 108 men | |||

| [33] | 48 women | SOAEs | More numerous and stronger SOAEs in women compared to men |

| 45 men | CEOAEs | Greater response amplitude of CEOAEs in women compared to men | |

| [40] | Longitudinal study | Audiometry | Increased hearing sensitivity at frequencies above 1 kHz in women compared to men |

| 461 women | (0.5–8 kHz) | Decreased hearing sensitivity at lower frequencies in women compared to men | |

| 681 men | Hearing threshold increases more than twice as fast in men compared to women, at most frequencies | ||

| Age of hearing loss onset is later in women than in men at most frequencies | |||

| [38] | 473 participants | Audiometry | Increased hearing sensitivity in 70 year old women compared to age-matched men in the 4–8 kHz frequency range |

| (0.25–8 kHz) | Increased hearing sensitivity in 75 year old women compared to age-matched men in the 1–8 kHz frequency range | ||

| [39] | 902 women | Audiometry | Increased hearing sensitivity in women compared to age-matched men at 4 and 8 kHz |

| 214 men | (0.25–8 kHz) | Men have faster rates of threshold increase compared to women at 4 and 8 kHz | |

| [41] | 24 epidemiological studies |

Audiometry Self-reported hearing impairment |

Above 70 years of age, men have increased prevalence of a 30 dB hearing loss compared to women |

| [31] | 18650 participants |

Audiometry (0.5–6 kHz) |

Men have increased prevalence of hearing loss compared to women |

| [32] | 9208 women |

Audiometry (0.25–8 kHz) |

Increased hearing sensitivity in women at 3 kHz, 4 kHz, and 6 kHz compared to age-matched men (12–85 years old) |

| 6398 men | |||

| [30] | 1878 women |

Audiometry (0.25–8 kHz) |

Men have increased risk of speech frequency hearing impairment (average of thresholds at 0.5, 1, 2 and 4 kHz > 25 dBs) |

| 1953 men |

ABR Auditory Brainstem Response, SOAEs Spontaneous Otoacoustic Emissions, CEOAEs Click-Evoked Otoacoustic Emissions, kHz kilo Hertz (sound frequency), dBs Decibels (sound intensity)

Fig. 3.

Hearing tests. a Auditory Brainstem Response is an objective measure of the brain electrical activity in response to sound stimulation. The recording electrodes are placed on the scalp and stimulation is performed at different intensities (20–90 decibels, dB) for different frequencies (250–8000 Hertz, Hz). A typical recording displays, in human, 7 peaks (or waves I–VII) within 10 ms. Each wave corresponds to a neuronal relay along the pathway and is characterized by its amplitude (in microVolts, µV) correlating with sensitivity and by its latency (in milliseconds, ms) correlating with the transmission speed. Wave I reflects the cochlear nerve activity and is, thus, indicative of the hair cells (HC) and/or spiral ganglion neuron (SGN) function. Waves II–VII reflect the activity of dorsal/ventral cochlear nucleus, superior olivary complex, lateral lemniscus, inferior colliculus, medial geniculate body and cortex, respectively. The ABR hearing threshold is set as the minimal intensity of sound that evokes a well-defined and reproducible electrical response. b Otoacoustic emissions (OAEs) recording is an objective measure. An insert is placed in the ear canal, it contains a speaker that emits a sound and a microphone that records the sound generated by the contraction of the outer hair cells (OHCs), OAEs can be spontaneous (OHCs contract spontaneously) or click-evoked (contraction of OHCs in response to a brief sound click). Distorsion-product OAEs (DPOAEs) are responses that are generated when the cochlea is stimulated simultaneously by two pure tone frequencies (f2 and f1). In all cases, OAEs reflect the contractile activity of OHCs and thus their functional integrity. c Audiometry is a subjective test, for which sound stimulations are pure tones emitted by an audiometer, at different intensities and different frequencies (250–8000 Hz). The patient informs the operator when a sound is heard. The hearing threshold corresponds to the lowest intensity at which a tone is perceived by the patient. The audiogram plots the hearing thresholds that have been determined for each frequency tested. The audiograms of a normal-hearing (black) and of a patient affected by a high-frequency hearing loss (green) are depicted. The high-frequency sounds are detected at the basal portion of the cochlea, while the low-frequency sounds are detected at the apical portion of the coiled cochlea

Estrogen deficiency and hearing loss

Although women experience a fast auditory decline after menopause, the onset of hearing loss is delayed compared to men and they have a better hearing function than men of the same age [30, 38–41]. A sex gap in audition has also been evidenced in aged rodents, as hearing decline appears later in female mice and rats compared to males [42–44]. The protective role of estrogen against age-related hearing loss was unambiguously evidenced through the use of knockout mice (KO). While ERαKO animals do not seem to suffer any obvious inner ear abnormalities, mice lacking ERβ are deaf at 1 year of age [18]. In these mice, deafness is associated with the degeneration of the sensory epithelium and the innervating SGNs, suggesting that estrogen signaling through ERβ is crucial to preserve the integrity of the cochlear tissue.

The consequence of a lack of estrogen on the auditory function is also manifest in Turner syndrome (TS). This genetic disease is characterized by the complete or partial absence of one X chromosome, resulting in gonadal dysgenesis and therefore loss of estrogen production. In addition to common conductive hearing loss, TS young adults suffer from definitive sensorineural hearing impairment, characterized by a progressive high-tone hearing loss that resembles presbycusis (age-related hearing loss) but which progresses much faster [45–47]. A mouse model of TS recapitulates the human hearing disorder as mice display a reduced sensitivity, prolonged ABR latencies and reduced DPOAEs [48]. Hearing loss is particularly evident for the high-frequency sounds and may correlate with the loss of OHCs located in the basal turn of the cochlea and swollen nerve endings beneath the IHCs [48].

Altogether these studies from physiological and pathological conditions strongly indicate that estrogen plays a beneficial role in the cochlear function and that high circulating levels would guarantee a protection against age-related hearing loss.

Estrogen supplementation and hearing

Estrogen is widely used in women as it is one of the main components of both contraceptive pills and menopausal hormonal treatment (MHT). Moreover, it is also used in young TS patients to substitute their lack of estrogen production. Hence, there have been many comparative studies investigating the consequences of exogenous estrogen administration on hearing function (Table 2). While some studies demonstrate a hearing improvement upon MHT [37, 49–52], others suggest that E2 administration could increase the risk of hearing loss [53, 54]. Finally, no hearing benefits of a hormonal treatment could be demonstrated in adult TS patients [55]. As suggested by animal studies, the great variability in the hearing outcome of exogenous estrogen is likely to depend on the regimen, the dose and the age of the recipients [56–58].

Table 2.

Estrogen treatments and hearing

| Study | Subjects and treatment | Hearing test | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| [37] | 1842 postmenopausal women: | Audiometry | E2 (endogenous or MHT) positively affects hearing |

| 66 MHT | Lower level of serum E2 correlates with decreased hearing sensitivity | ||

| 1774 untreated | |||

| [52] | 109 postmenopausal women: | Audiometry | E2 treatment positively affects hearing |

| 20 E2 | Mean air conduction for low frequencies (0.25, 0.5, 1, 2 kHz): E2 > E2+P and E2 > Ctl | ||

| 30 E2+P | Mean air conduction for high frequencies (4, 6, 8, 10, 14, 16 kHz): E2 > E2+P | ||

| 59 Ctl : untreated | |||

| [50] | 143 women around menopause: | Audiometry | E2 treatment positively affects hearing |

| 47 premenopausal | Postmenopausal women without MHT have decreased hearing sensitivity at 2 and 3 kHz compared to those under MHT | ||

| 32 perimenopausal | Postmenopausal women without MHT have decreased hearing sensitivity at 2 and 3 kHz compared to pre- and peri-menopausal women | ||

| 21 postmenopausal | |||

| 43 MHT | |||

| [49] | 122 postmenopausal women: | ABR | E2 treatment positively affects ABR |

| Transdermal E2 (patch) | E2, in both groups, decreases wave latencies and interpeak intervals | ||

| Transdermal E2 (gel) | |||

| [51] | 47 menopausal women: | ABR | E2 treatment positively affects ABR and MLR |

| 32 natural (E2+P) | MLR | ABR and MLR : E2 decreases wave latencies after 6 months of treatment | |

| 15 surgically (E2) | |||

| [54] | 1 female (45 years old) + E2 | Audiometry |

E2 treatment negatively affects hearing MHT induces a sudden sensorineural hearing loss at low frequencies |

| [59] | 124 menopausal women: | Audiometry | E2+P treatment negatively affects hearing and cochlear function |

| 32 (E2+P) | DPOAE | E2+P decreases hearing sensitivity compared to the E2 and untreated groups | |

| 30 (E2) | HINT | E2+P decreases DPOAEs levels compared to the E2 and untreated groups | |

| 62 (untreated) | E2+P decreases speech perception compared to the E2 and untreated groups | ||

| [53] | 80972 women aged 27-44: | Self-reported hearing loss | E2 (endogenous or MHT) negatively affects hearing |

| Naturally menopausal | No significant association between menopausal status, natural or surgical, and risk of hearing loss. | ||

| Surgically menopausal | Older age at natural menopause was associated with higher risk of hearing loss. | ||

| MHT (E2 or E2+P) | Among postmenopausal women, MHT is associated with higher risk of hearing loss | ||

| 22 years follow-up | Among postmenopausal women, longer duration of MHT is associated with higher risk of hearing loss | ||

| [55] | 138 women (aged 16-67): | Audiometry | E2 treatment has no impact on hearing |

| XO (Turner patients) | Sensorineural hearing loss in 57.2% | ||

| GH and E2 (or E2+P) | Sensorineural hearing loss is not associated with E2 or GH treatment (independent of age) |

MHT Menopausal Hormone Therapy, E2 estradiol treatment, E2+P combined hormone therapy with estradiol and progesterone, XO partial or complete loss of one X chromosome, GH Growth Hormone, ABR Auditory Brainstem Response, MLR Middle Latency Response, DPOAE Distorsion Product Otoacoustic Emission, HINT Hearing in Noise Threshold, kHz kilo Hertz (sound frequency)

Clinical discrepancies might arise from the presence of progesterone in combined hormone therapy, as it was shown that providing estrogen together with progesterone negatively affects hearing thresholds in human and mouse [52, 58, 59]. This negative effect of progesterone hormone when combined to estrogen is intriguing. However, recent experiments have demonstrated that ligand-activated progesterone receptor (PR) associates with ERα and forces it to bind a new subset of target genes [60]. Progesterone, thus, imposes a switch in ER transcriptional program and leads to a different estrogen-mediated cellular response that could be detrimental to the cochlear function. During the menstrual cycle, the ratio between the two hormones is not constant since they are fluctuating and do not reach their highest level at the same time. Moreover, the hormonal cyclicity might be of crucial importance, as estrogen was shown to induce differential effects upon continuous or pulsed administration [61, 62]. Therefore, the constant delivery of estrogen and progesterone in combined MHT does not faithfully replicate what naturally occurs during the female cycle and could, thus, lead to a different final outcome.

The conflicting results obtained in E2-treated women could also reflect the variability in circulating concentrations between patients, according to the hormone formulation and route of administration [63]. Furthermore, the hormonal status and responsiveness of each patient might impact the sensitivity of estrogenic treatment. Indeed, E2 upregulates both ERα and ERβ [64, 65], inferring that their expression could be diminished upon estrogen deficiency. This implies that a lack of endogenous estrogen at menopause or in TS could be associated with insufficient amounts of ER to mediate the beneficial estrogenic effects. In support of this, the cochlear levels of ERβ are lower in the absence of estrogen production in a mouse model of TS [17] and in the aromatase-depleted ARKO mice [19] than those of control animals.

Collectively, these data suggest that the absence of hearing preservation by exogenous estrogen could be due to its association with progesterone, to non-optimal doses and to variable estrogen sensitivities. A clear understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying the effects of estrogen on hearing sense is, thus, needed to optimize hormonal treatments and potentially adjust them according to personalized parameters.

Otoprotective role of estrogen following injury

Estrogen and noise-induced hearing loss

Although sex differences have been reported regarding noise-induced hearing loss [40, 66] it is still unclear whether it can be attributable to the circulating estrogen level. Indeed, men are highly exposed to occupational noise compared to women and this would potentially bias the interpretation of population studies. Fortunately, researchers can control the acoustic environment of animal models and those have proven very helpful in analyzing the potential of estrogen in noise-induced cochlear dysfunction. Interestingly, the susceptibility to excessive noise exposure is exacerbated by estrogen depletion following ovariectomy of female rats [67]. Similarly, the anti-estrogenic effect of Tamoxifen is able to potentiate the damaging effect of noise exposure in gerbils. Tamoxifen decreases the amplitude of DPOAE and increases the auditory threshold, suggesting a reduced electromotility of OHCs and a reduced hearing sensitivity, respectively [68]. The otoprotective effect of estrogen against acoustic trauma is mediated by ERβ receptor. Indeed, ERβKO mice show increased sensitivity to noise exposure as they exhibit a higher temporary threshold shift compared to control and ERαKO mice [19]. Furthermore, in both WT and estrogen-deficient ARKO mice, a specific ERβ agonist (2,3-bis 4-hydroxyphenyl proprionitrile, DPN) is able to reduce the threshold shift and thus to protect the cochlea from noise-induced damage [19]. While the invalidation of ERα does not affect the vulnerability to acoustic trauma, its selective agonist (propyl1H pyrazole-1,3,5-triyl trisphenol, PPT) was able to confer partial protection in ARKO mice [19]. The authors suggested it could reflect a mild agonistic action on ERβ; however, PPT is also a weak activator of GPER [69] and the potential contribution of this membrane receptor still needs to be investigated.

Estrogen and drug-induced hearing loss

Cisplatin is a mainstay of cancer treatment, even if it is one of the utmost ototoxic drugs in clinical practice. It predominantly affects the cochlear function because of its accumulation in the stria vascularis, where it persists for months-to-years following chemotherapy [70]. Studies performed in pediatric populations (less than 18 years old) pointed out that male sex is a significant risk factor for cisplatin ototoxicity [71, 72]. Whether this increased damaging effect of the anticancer drug may be attributed to reduced estrogen levels is elusive as the concentration of circulating hormone is rather low and similar between males and females before puberty. However, a link with low estrogen level was demonstrated in experimental animals as ovariectomized rats display an increased risk of auditory damage after cisplatin treatment when compared to controls [73].

Aminoglycoside antibiotics constitute the treatment of choice for severe bacterial infections despite their toxic potential to the inner ear and kidney. Typically, aminoglycosides not only induce OHC death but also cause cochlear synaptopathy by disrupting the synapses between IHC and their afferent SGNs [74]. In cultured rat cochleae, E2 reduces the extent of OHC loss induced by gentamicin [75], suggesting an otoprotective role in this context as well. Whether estrogen also acts on neuritic outgrowth and contributes to synapse recovery in the damaged otic epithelium is unknown, but a similar property was demonstrated on the olfactory epithelium [76].

Potential interference between estrogen and therapeutic agents

A very recent study confirmed a sex difference in noise-induced hearing loss in mice, but unexpectedly, also pointed out an opposite sex effect in the therapeutic efficacy of SAHA, a histone deacetylase inhibitor (HDACi) [77]. While females are less susceptible to acoustic trauma, the beneficial effect of HDACi was markedly reduced compared to that observed in noise-exposed males. The increased variability of the data collected within the female group and the reduced damage they experience upon sound exposure could provide a technical explanation for their lower benefit from SAHA administration; however, this observation could reveal biological relevance in case of interference between HDACi and estrogen-mediated pathways. Interestingly, a crosstalk between HDACi and estrogen signaling has been evidenced in breast cancer, where the inhibitor affects both positively and negatively the levels of ERs (reviewed in [78]). In ERα-negative cancer cells, HDACi causes the upregulation of ERα and/or ERβ, and thereby resensitizes the cells to tamoxifen anticancer therapy. On the contrary, in cancer cells expressing ERα, HDACi not only represses its transcription but also induces the hyperacetylation of the chaperone Hsp90, which is no longer able to protect ERα from degradation. By reducing the level of ERα, HDACi acts as an anti-estrogen and thus also exerts anticancer effects. Given that cochlear cells express ERα, it is tempting to think that HDACi could negatively modulate estrogen signalling and thereby reduce its protective effect against noise trauma in females. Whether the inhibitor is able to reduce the levels of ERβ deserves further investigations, as it seems to be the major player in otoprotection. Of note, inhibiting HDAC was also shown to protect against gentamicin-induced hearing loss in guinea pigs [79]; however, differential efficacy between males and females was not investigated. Future experiments are needed to determine if, similarly to what has been shown in noise-induced hearing loss, HDACi treatment would provide sexually dimorphic responses because of a potential interaction with estrogen signaling.

Altogether, these studies underscore the importance of estrogen in preserving the auditory system from exogenous insults, and most importantly, highlight the crucial need to discriminate between males and females when addressing the auditory function or testing the potential of therapeutic candidates against hearing loss. Although the National Institutes of Health (NIH) issued a mandate in 2015 to include sex as a biological variable in all NIH-funded research, this recommendation is still poorly followed in the audition field [80, 81].

Potential mechanisms of estrogen otoprotection

Genomic or non-genomic action?

The precise mechanism by which estrogen ameliorates the hearing function during aging, acoustic trauma or ototoxic insult has not been specifically investigated yet. However, the recent implication of estrogen-related receptors (ERRs) as well as an ER coactivator may be considered as indicators that the transcriptional effect of ER, and thus the genomic action of estrogen, is crucial.

ERRs are orphan nuclear receptors that share a high degree of homology with ERs and act as constitutively active transcriptional factors [82]. Among the three members of this subgroup, both ERRβ and ERRγ, which are particularly homologous to ERβ, display genetic variations that are associated with hearing impairments. Mutations in the ESRRB gene, encoding ERRβ protein, are responsible for an autosomal recessive form of non-syndromic hearing loss [83, 84]. Moreover, an ESRRB polymorphism is linked to increased susceptibility to noise exposure [85]. Regarding the gene encoding ERRγ, a polymorphism is associated with lower hearing status [86] and a chromosomal translocation was recently discovered in a case of congenital sensorineural hearing loss [87]. The contribution of ERRβ and ERRγ to the maintenance of hearing is further supported by genetic invalidation studies demonstrating that ERRβ knockout mice are deaf at 3 months of age [88], while ERRγ depletion leads to hearing loss as soon as 5 weeks of age [86].

ERRs share common transcription targets with ERs as they are able to bind and regulate some ERE-containing genes. It is, thus, tempting to speculate that the beneficial role of estrogen on hearing would, at least in part, be mediated through the classical genomic action. This hypothesis is further strengthened by the discovery that Wbp2, a transcriptional coactivator for ER, is essential for hearing [89]. Whether non-genomic actions of estrogen also contribute to hearing preservation is still an open question. Future experiments making use of membrane-impermeable estrogen, GPER agonists or antagonists as well as transgenic mouse expressing mutant forms of ERα or ERβ, which localize either at the membrane or exclusively in the nucleus [90], would be necessary to answer this question.

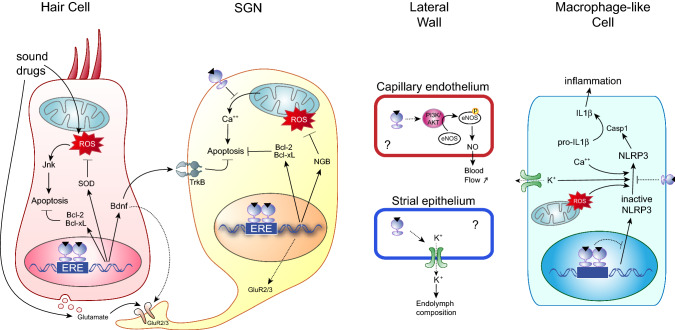

Potential mechanisms in cochlear HCs

The sensory HCs are the primary decoder of sound and their death leads to irreversible hearing loss. The increased amplitudes of ABR wave I and of OAEs in women compared to men point out for a role of estrogen on the functionality of HCs (see Estrogenic influence on hearing section). In mouse model, ERβ deficiency leads to the premature degeneration of the sensory epithelium [18] and cultured HCs were shown to be protected from gentamicin exposure by an estrogenic treatment [75]. The cochlear HCs are, thus, strong candidates to benefit from estrogen actions. The accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and consequent oxidative stress is recognized as a major contributor to the onset and progression of HC death following acoustic trauma, ototoxic insults or aging [91, 92]. Estrogen is known to protect the bone, cardiovascular and central nervous systems against aging or damage by regulating the redox balance (reviewed in [93–96]). Estrogen displays an intrinsic free-radical scavenging capacity [97, 98]; however, this antioxidant activity requires high concentrations of the steroid, suggesting that it is not the only mechanism involved in cell protection. Estrogen also enhances the expression of Superoxide Dismutases (SOD) in the heart and the brain [99, 100] and the activity of those antioxidant enzymes is increased in the blood cells of women under MHT [101, 102]. A similar increase in the antioxidant defense of HCs (Fig. 4) would clearly improve cell survival and would preserve the hearing function. Indeed, antioxidant treatment with N-acetylcysteine (NAC) protects HCs and reduces the incidence of presbycusis, drug or noise-induced hearing loss in animal models and in humans [103–105].

Fig. 4.

Potential mechanisms of hearing preservation by estrogen in different cochlear cell types. Estrogen increases the expression of the anti-oxidant genes SOD and thereby could reduce ROS-induced apoptosis in HCs, which is mediated by Jnk. Furthermore, the direct upregulation of anti-apoptotic genes such as Bcl2 and Bcl-xL could be involved HC and SGN survival. E2 enhances Bdnf expression from the HCs, which in turn promotes SGN survival through specific TrkB receptors. In addition, high concentrations of Bdnf could lower the risk of synaptic disruption upon insult. Noise trauma causes excessive release of glutamate from the sensory HCs that can lead to SGN apoptosis through the mitochondrial pathway and ROS overload. In this context, E2 improves SGN survival by reducing Ca2+ efflux. NGB could also be involved in neuroprotection as it is an E2 target and a potent ROS scavenger. The beneficial effect of estrogen in the stria vascularis and the spiral ligament has not been investigated; however, it could play a vasorelaxant action through eNOS activation in cochlear capillaries and would thereby maintain cochlear homeostasis by regulating blood flow. E2 is also known to regulate many ion channels, including K+ channels expressed in strial cells that are crucial for endolymph composition and mechanotransduction. Finally, estrogen could reduce cochlear inflammation by inhibiting NLRP3 expression or activation in cochlear resident macrophage-like cells. Through its antioxidant action or via the regulation of Ca2+ or K+ fluxes, E2 would inhibit the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL1β

Whereas low levels of ROS are crucial to many physiological functions, an excessive production of ROS triggers oxidative damage to lipids, proteins and DNA and leads to apoptosis [106]. Nakamagoe et al. demonstrated that estrogen is able to reduce gentamicin-induced apoptosis of HCs by inhibiting the JNK pro-apoptotic pathway [75]. This protective effect of estrogen is suggested to be dependent on ERα or ERβ receptors, as it is prevented by their common antagonist ICI182780 [107]. Estrogen could also inhibit ROS-induced apoptosis in cochlear HCs by upregulating anti-apoptotic factors. Among those, Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL are known to be upregulated by E2 in neurons [108, 109] and the presence of ERE sequences within these genes suggest that they could be direct targets of ERs [109, 110]. Alternatively, Bcl-2 could be induced by estrogen following the rapid activation of PI3K/AKT signaling pathway [111]. The exact mechanism by which estrogen ameliorates cochlear HC survival remains to be determined, but the existing data on ERβKO mouse demonstrate that ERβ is necessary to impede the progressive loss of HCs during aging [18].

Potential neuroprotective mechanisms in the spiral ganglion

ERβ-deficient animals display neuronal degeneration in the brain of young adults [112] as well as in the spiral ganglion of aged mice [18]. In many cases, SGN loss is secondary to HC death but, in ERβKO cochleae, signs of neuronal damage are detected before sensory cell death, as Stenberg et al. reports the presence of swollen afferent terminals beneath normal IHCs [17]. Interestingly, similar observations were made in the estrogen-deficient Turner mouse [17] and upon genetic invalidation of Wbp2 [89], suggesting that cochlear synaptopathy is a direct consequence of reduced estrogen signaling. Such morphological abnormalities of SGN peripheral endings are classically associated with glutamate excitotoxicity after acoustic trauma, even when it only causes a temporary threshold shift, and thus a reversible hearing loss (reviewed in [113]). In these cases, synaptic disruption is crucially implicated in cochlear dysfunction, as SGNs and HCs are preserved during the period of hearing threshold changes. Noteworthy, ERβKO mice show increased sensitivity to moderate sound exposure, but the density and the morphology of ribbon synapses have not been studied [19]. Nevertheless, this enhanced vulnerability to acoustic overexposure in young adults might account for deafness of ERβKO animals at later stages, as temporary threshold shifts are increasingly recognized as a risk factor for delayed SGN loss and premature age-related hearing loss [114]. The slow degeneration of auditory neurons would be consequent to the early synaptic disruption and neurite retraction, which reduces the neuronal supply in the neurotrophins that are released from the target sensory epithelium.

At the molecular level, the estrogenic regulation of Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (Bdnf) could be involved in SGN preservation (Fig. 4). Meltser et al. showed that young ERβKO mice express lower levels of Bdnf and that the ERβ agonist DPN induces its transcriptional upregulation in control mice [19]. Promoter studies have indicated the presence of an ERE upstream of the transcriptional start site of Bdnf, further suggesting that it is a direct target of ER [115]. Estrogen and ERβ would, therefore, be required to guarantee high Bdnf secretion from the sensory epithelium and ensure SGN survival. Whether endogenous Bdnf could also be involved in the maintenance of cochlear synaptic contacts at postnatal stages is less clear [116, 117], but high doses of Bdnf agonist are able to partially protect against synaptic loss and improve the hearing function following acoustic trauma [118]. Synapse deterioration in the absence of estrogen signaling could also be due to changes in the expression level of post-synaptic proteins present in afferent terminals. Most importantly, the glutamate receptor subunit GluR2/3 is downregulated in Wbp2KO cochleae and, accordingly, post-synaptic densities are disorganized [89]. In hippocampal neurons, brain-derived E2 has already been reported to modulate glutamatergic synapses [119]. Local estrogen increases post-synaptic sensitivity in both sexes, but unexpectedly its action is mediated by ERβ in males, whereas it acts through GPER in females. Such differences in E2 action modes have been referred to as latent sex differences, as they lead to the same functional endpoint [120, 121], but this raises the interesting question whether different estrogen receptor sensitivities to the local neuromodulator could in some instances underlie a sex dimorphic response.

Estrogen could also exert a direct action on neuronal survival by impeding apoptotic cascades or enhancing their antioxidant defense (Fig. 4). For instance, estrogen was shown to inhibit glutamate-induced cell death in cultured neurons and rodent models of excitotoxic injury and the underlying mechanisms include ER-dependent mitochondrial Ca2+ sequestration and Bcl2 upregulation [122, 123]. In other contexts involving oxidative stress and ischemic injury, the neuroprotective effect of estrogen relies on the strong upregulation of Neuroglobin (NGB), a potent ROS scavenger [124]. Besides its intrinsic capacity to reduce the amount of endogenous ROS, NGB inhibits the mitochondrial-dependent pathway of apoptosis. Interestingly, the neuroprotective effect of estrogen-induced NGB on H2O2-induced apoptosis was shown to be reliant on ERβ [125]. In the mammalian cochlea, NGB is expressed in SGNs and its expression seems to be reduced in post-mortem samples of human diagnosed with hearing loss [126, 127]. Whether estrogen signaling upregulates NGB in the SGNs and whether NGB is involved in its ERβ-dependent protective effects on SGN survival during aging or acoustic trauma need to be elucidated in future experiments.

Potential mechanisms in the lateral wall

The analyses of ERβKO cochleae did not include a close inspection of the cochlear lateral wall. Therefore, it is still unknown whether estrogen could exert a protective role by acting on the stria vascularis or the spiral ligament. However, these structures are crucial for cochlear homeostasis as they are involved in ion transport to generate the exquisite endocochlear potential (EP) and their functional disruption can lead to cochlear degeneration [128]. Amongst the various ion channels that are regulated by estrogen (reviewed in [129, 130]), Kcnq1 and Kcnj10/Kir4.1 are crucial for K+ secretion into the endolymph and the auditory function [131, 132]. Estrogen dose-dependently affects K+ currents in stria vascularis cell cultures, but intriguingly estrogen was responsible for a reduction of K+ secretion [133].

The maintenance of cochlear homeostasis is also reliant on the dense capillary networks present in the lateral wall [134]. In the vascular system, estrogen promotes a rapid and protective endothelial-dependent vasodilation response by enhancing nitric oxide (NO) production. Through an ER-dependent mechanism, estrogen directly stimulates PI3K and Akt signaling pathways, which in turn phosphorylate and activate the endothelial NO synthase, eNOS [135]. As eNOS is expressed in the blood vessels of the stria vascularis and the spiral ligament [136] and its activity increases the cochlear blood flow [137], it is plausible that, in the cochlea, estrogen activates eNOS and mediates a vasorelaxant effect that would offset the mechanisms leading to reduced cochlear blood flow.

Whether ERβ preserves cochlear homeostasis by fine-tuning ion transport and endolymph composition in addition to regulating cochlear blood flow should be addressed in future studies. Most importantly, ERβ expression studies in mouse and humans are still required to clarify the existence of estrogen signaling in this cochlear compartment.

Protection against cochlear inflammation

The inflammatory response is necessary to tailor the appropriate adaptive immune response upon infection and is also crucial for tissue homeostasis. In some instances, excessive or prolonged inflammation may be deleterious and there is increasing evidence that drug-, noise- or aging-induced hearing loss are closely associated with local inflammation [138]. As estrogen is well known to exert anti-inflammatory effects in the aging or injured brain and thereby contributes to neuroprotection, some of the underlying mechanisms could, thus, be of critical importance to cochlear function.

Recently, estrogen was shown to reduce neuroinflammation by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome [139, 140]. This multisubunit complex assembles in innate immune cells upon specific triggers related to cellular stress. NLRP3 activates caspase1 that induces the maturation and release of IL1β and IL18 pro-inflammatory cytokines [141]. Increased NLRP3-mediated inflammation in the hippocampus of ovariectomized mice could be prevented by E2 or DPN, suggesting an anti-inflammatory action through ERβ[140]. Inflammasome is also a key initiator of cochlear inflammation and a recent study suggests its involvement in the physiopathology of presbycusis [142]. Moreover, NLRP3 gain-of-function mutations cause syndromic and non-syndromic sensorineural hearing loss, characterized by increased vascular permeability and cochlear autoinflammation [143]. This report also reveals that NLRP3-positive cells are resident macrophage–monocyte-like cells, which are distributed throughout the cochlea, along the auditory nerve, the spiral ganglion, the stria vascularis and the spiral ligament. Importantly, IL1β blockade therapy is able to improve the hearing status of some NLRP3-affected individuals [143] as well as patients suffering from a distinct form of hearing disorder associated with exacerbated inflammation [144]. Recently, an agonist of Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) was shown to attenuate noise-induced hearing loss in rats by reducing the cochlear expression of IL1β[145]. If estrogen negatively regulates NLRP3 in the cochlea following environmental stress or aging, it would, thus, be a potent agent useful in therapeutic strategies to reduce the damaging effect of local inflammation and to protect against hearing loss.

Conclusion and perspectives

The benefits of estrogen action are not limited to the reproductive, central nervous and cardiovascular systems, as the hormone also plays a role in the inner ear. A positive influence of estrogen on hearing function has been suggested for long and continues to be experimentally evidenced in many studies. Because the hearing sensibility is correlated with the level of estrogen, there is a sex gap in audition and females are protected against hearing loss until menopause. While the use of estrogen in MHT has been shown to delay or minimize hearing loss in some studies, it has been contradicted by a number of reports. The MHT regimen, dose and administration route as well as the age, hormonal status and responsiveness of the patients are critical parameters that greatly impact the estrogen outcome on hearing.

All estrogen receptors are expressed in the cochlea at varying levels but ERβ seems to play a predominant role in the maintenance of the cochlear function during aging or following acoustic trauma. By acting in the sensory HCs, the SGNs and possibly in the stria vascularis, estrogen signaling through ERβ could enhance antioxidant, anti-apoptotic and anti-inflammatory responses that would all contribute to hearing preservation. These effects are frequently mediated through the classical genomic action of estrogen although some membrane-initiated signaling involving MAPK, PKA and PI3K probably occurs as well. These estrogen actions open obvious therapeutic doors; however, future experiments are still needed to explore the precise mechanisms of otoprotection and to clearly identify the selective estrogen receptor modulator and the therapeutic strategy that could offer hearing preservation.

Acknowledgements

We thank Bernard Minguet for the illustrations of this manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the Belgian National Funds for Scientific Research (FSR-FNRS), the fondation Léon-Frédéricq (ULiège, Belgium) and the Fonds spéciaux (University of Liège, Belgium).

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Roth TN. Aging of the auditory system. Handb Clin Neurol. 2015;129:357–373. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-62630-1.00020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davis A, McMahon CM, Pichora-Fuller KM, Russ S, Lin F, Olusanya BO, Chadha S, Tremblay KL. Aging and hearing health: the life-course approach. Gerontologist. 2016;56(Suppl 2):S256–S267. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim SY, Lim JS, Kong IG, Choi HG. Hearing impairment and the risk of neurodegenerative dementia: a longitudinal follow-up study using a national sample cohort. Sci Rep. 2018;8:15266. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-33325-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin FR, et al. Hearing loss and cognitive decline in older adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:293–299. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.1868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gruber CJ, Tschugguel W, Schneeberger C, Huber JC. Production and actions of estrogens. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:340–352. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra000471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barakat R, Oakley O, Kim H, Jin J, Ko CJ. Extra-gonadal sites of estrogen biosynthesis and function. BMB Rep. 2016;49:488–496. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2016.49.9.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tremere LA, Burrows K, Jeong JK, Pinaud R. Organization of estrogen-associated circuits in the mouse primary auditory cortex. J Exp Neurosci. 2011;2011:45–60. doi: 10.4137/JEN.S7744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caras ML. Estrogenic modulation of auditory processing: a vertebrate comparison. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2013;34:285–299. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maney DL, Pinaud R. Estradiol-dependent modulation of auditory processing and selectivity in songbirds. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2011;32:287–302. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Remage-Healey L, Saldanha CJ, Schlinger BA. Estradiol synthesis and action at the synapse: evidence for “synaptocrine” signaling. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2011;2:28. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2011.00028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forlano PM, Deitcher DL, Bass AH. Distribution of estrogen receptor alpha mRNA in the brain and inner ear of a vocal fish with comparisons to sites of aromatase expression. J Comp Neurol. 2005;483:91–113. doi: 10.1002/cne.20397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yasar P, Ayaz G, User SD, Gupur G, Muyan M. Molecular mechanism of estrogen-estrogen receptor signaling. Reprod Med Biol. 2017;16:4–20. doi: 10.1002/rmb2.12006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arnal JF, et al. Membrane and nuclear estrogen receptor alpha actions: from tissue specificity to medical implications. Physiol Rev. 2017;97:1045–1087. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00024.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levin ER, Hammes SR. Nuclear receptors outside the nucleus: extranuclear signalling by steroid receptors. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2016;17:783–797. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Motohashi R, Takumida M, Shimizu A, Konomi U, Fujita K, Hirakawa K, Suzuki M, Anniko M. Effects of age and sex on the expression of estrogen receptor alpha and beta in the mouse inner ear. Acta Otolaryngol. 2010;130:204–214. doi: 10.3109/00016480903016570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stenberg AE, Wang H, Sahlin L, Hultcrantz M. Mapping of estrogen receptors alpha and beta in the inner ear of mouse and rat. Hear Res. 1999;136:29–34. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(99)00098-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stenberg AE, Wang H, Sahlin L, Stierna P, Enmark E, Hultcrantz M. Estrogen receptors alpha and beta in the inner ear of the ‘Turner mouse’ and an estrogen receptor beta knockout mouse. Hear Res. 2002;166:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(02)00310-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simonoska R, Stenberg AE, Duan M, Yakimchuk K, Fridberger A, Sahlin L, Gustafsson JA, Hultcrantz M. Inner ear pathology and loss of hearing in estrogen receptor-beta deficient mice. J Endocrinol. 2009;201:397–406. doi: 10.1677/JOE-09-0060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meltser I, Tahera Y, Simpson E, Hultcrantz M, Charitidi K, Gustafsson JA, Canlon B. Estrogen receptor beta protects against acoustic trauma in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1563–1570. doi: 10.1172/JCI32796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andersson S, et al. Insufficient antibody validation challenges oestrogen receptor beta research. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15840. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nelson AW, et al. Comprehensive assessment of estrogen receptor beta antibodies in cancer cell line models and tissue reveals critical limitations in reagent specificity. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2017;440:138–150. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2016.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang L, Xu Y, Zhang Y, Vijayakumar S, Jones SM, Lundberg YYW. Mechanism underlying the effects of estrogen deficiency on otoconia. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2018;19:353–362. doi: 10.1007/s10162-018-0666-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scheffer DI, Shen J, Corey DP, Chen ZY. Gene expression by mouse inner ear hair cells during development. J Neurosci. 2015;35:6366–6380. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5126-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simpson ER. Sources of estrogen and their importance. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;86:225–230. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(03)00360-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dehan CP, Jerger J. Analysis of gender differences in the auditory brainstem response. Laryngoscope. 1990;100:18–24. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199001000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jerger J, Hall J. Effects of age and sex on auditory brainstem response. Arch Otolaryngol. 1980;106:387–391. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1980.00790310011003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wharton JA, Church GT. Influence of menopause on the auditory brainstem response. Audiology. 1990;29:196–201. doi: 10.3109/00206099009072850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bilger RC, Matthies ML, Hammel DR, Demorest ME. Genetic implications of gender differences in the prevalence of spontaneous otoacoustic emissions. J Speech Hear Res. 1990;33:418–432. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3303.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McFadden D, Loehlin JC, Pasanen EG. Additional findings on heritability and prenatal masculinization of cochlear mechanisms: click-evoked otoacoustic emissions. Hear Res. 1996;97:102–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoffman HJ, Dobie RA, Losonczy KG, Themann CL, Flamme GA. Declining prevalence of hearing loss in US adults aged 20 to 69 years. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;143:274–285. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2016.3527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jun HJ, Hwang SY, Lee SH, Lee JE, Song JJ, Chae S. The prevalence of hearing loss in South Korea: data from a population-based study. Laryngoscope. 2015;125:690–694. doi: 10.1002/lary.24913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park YH, Shin SH, Byun SW, Kim JY. Age- and gender-related mean hearing threshold in a highly-screened population: the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2010–2012. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0150783. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Snihur AW, Hampson E. Sex and ear differences in spontaneous and click-evoked otoacoustic emissions in young adults. Brain Cogn. 2011;77:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adriztina I, Adnan A, Adenin I, Haryuna SH, Sarumpaet S. Influence of hormonal changes on audiologic examination in normal ovarian cycle females: an analytic study. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;20:294–299. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1566305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Serra A, Maiolino L, Agnello C, Messina A, Caruso S. Auditory brain stem response throughout the menstrual cycle. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2003;112:549–553. doi: 10.1177/000348940311200612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Upadhayay N, Paudel BH, Singh PN, Bhattarai BK, Agrawal K. Pre- and postovulatory auditory brainstem response in normal women. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;66:133–137. doi: 10.1007/s12070-011-0378-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim SH, Kang BM, Chae HD, Kim CH. The association between serum estradiol level and hearing sensitivity in postmenopausal women. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:726–730. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)01963-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jönsson R, Rosenhall U, Gause-Nilsson I, Steen B. Auditory function in 70- and 75-year-olds of four age cohorts. A cross-sectional and time-lag study of presbyacusis. Scand Audiol. 1998;27:81–93. doi: 10.1080/010503998420324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim S, Lim EJ, Kim HS, Park JH, Jarng SS, Lee SH. Sex differences in a cross sectional study of age-related hearing loss in Korean. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;3:27–31. doi: 10.3342/ceo.2010.3.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pearson JD, Morrell CH, Gordon-Salant S, Brant LJ, Metter EJ, Klein LL, Fozard JL. Gender differences in a longitudinal study of age-associated hearing loss. J Acoust Soc Am. 1995;97:1196–1205. doi: 10.1121/1.412231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roth TN, Hanebuth D, Probst R. Prevalence of age-related hearing loss in Europe: a review. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;268:1101–1107. doi: 10.1007/s00405-011-1597-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Balogova Z, Popelar J, Chiumenti F, Chumak T, Burianova JS, Rybalko N, Syka J. Age-related differences in hearing function and cochlear morphology between male and female fischer 344 rats. Front Aging Neurosci. 2017;9:428. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2017.00428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guimaraes P, Zhu X, Cannon T, Kim S, Frisina RD. Sex differences in distortion product otoacoustic emissions as a function of age in CBA mice. Hear Res. 2004;192:83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2004.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Henry KR. Males lose hearing earlier in mouse models of late-onset age-related hearing loss; females lose hearing earlier in mouse models of early-onset hearing loss. Hear Res. 2004;190:141–148. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5955(03)00401-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alves C, Oliveira CS. Hearing loss among patients with Turner’s syndrome: literature review. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;80:257–263. doi: 10.1016/j.bjorl.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bonnard A, Hederstierna C, Bark R, Hultcrantz M. Audiometric features in young adults with Turner syndrome. Int J Audiol. 2017;56:650–656. doi: 10.1080/14992027.2017.1314559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kubba H, Smyth A, Wong SC, Mason A. Ear health and hearing surveillance in girls and women with Turner’s syndrome: recommendations from the Turner’s Syndrome Support Society. Clin Otolaryngol. 2017;42:503–507. doi: 10.1111/coa.12750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hultcrantz M, Stenberg AE, Fransson A, Canlon B. Characterization of hearing in an X,0 ‘Turner mouse’. Hear Res. 2000;143:182–188. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(00)00042-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Caruso S, Maiolino L, Agnello C, Garozzo A, Di Mari L, Serra A. Effects of patch or gel estrogen therapies on auditory brainstem response in surgically postmenopausal women: a prospective, randomized study. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:556–561. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)04763-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hederstierna C, Hultcrantz M, Collins A, Rosenhall U. Hearing in women at menopause. Prevalence of hearing loss, audiometric configuration and relation to hormone replacement therapy. Acta Otolaryngol. 2007;127:149–155. doi: 10.1080/00016480600794446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Khaliq F, Tandon OP, Goel N. Auditory evoked responses in postmenopausal women on hormone replacement therapy. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2003;47:393–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kilicdag EB, Yavuz H, Bagis T, Tarim E, Erkan AN, Kazanci F. Effects of estrogen therapy on hearing in postmenopausal women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:77–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2003.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Curhan SG, Eliassen AH, Eavey RD, Wang M, Lin BM, Curhan GC. Menopause and postmenopausal hormone therapy and risk of hearing loss. Menopause. 2017;24:1049–1056. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Strachan D. Sudden sensorineural deafness and hormone replacement therapy. J Laryngol Otol. 1996;110:1148–1150. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100135984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ostberg JE, Beckman A, Cadge B, Conway GS. Oestrogen deficiency and growth hormone treatment in childhood are not associated with hearing in adults with turner syndrome. Horm Res. 2004;62:182–186. doi: 10.1159/000080888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Coleman JR, Campbell D, Cooper WA, Welsh MG, Moyer J. Auditory brainstem responses after ovariectomy and estrogen replacement in rat. Hear Res. 1994;80:209–215. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(94)90112-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cooper WA, Ross KC, Coleman JR. Estrogen treatment and age effects on auditory brainstem responses in the post-breeding Long-Evans rat. Audiology. 1999;38:7–12. doi: 10.3109/00206099909072996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Price K, Zhu X, Guimaraes PF, Vasilyeva ON, Frisina RD. Hormone replacement therapy diminishes hearing in peri-menopausal mice. Hear Res. 2009;252:29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Guimaraes P, Frisina ST, Mapes F, Tadros SF, Frisina DR, Frisina RD. Progestin negatively affects hearing in aged women. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:14246–14249. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606891103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mohammed H, et al. Progesterone receptor modulates ERalpha action in breast cancer. Nature. 2015;523:313–317. doi: 10.1038/nature14583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li J, Wang H, Johnson SM, Horner-Glister E, Thompson J, White IN, Al-Azzawi F. Differing transcriptional responses to pulsed or continuous estradiol exposure in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;111:41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2007.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Marriott LK, McGann-Gramling KR, Hauss-Wegrzyniak B, Sheldahl LC, Shapiro RA, Dorsa DM, Wenk GL. Brain infusion of lipopolysaccharide increases uterine growth as a function of estrogen replacement regimen: suppression of uterine estrogen receptor-alpha by constant, but not pulsed, estrogen replacement. Endocrinology. 2007;148:232–240. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gonzalez L, Witchel SF. The patient with Turner syndrome: puberty and medical management concerns. Fertil Steril. 2012;98:780–786. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.07.1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ing NH, Tornesi MB. Estradiol up-regulates estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor gene expression in specific ovine uterine cells. Biol Reprod. 1997;56:1205–1215. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod56.5.1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Potier M, Elliot SJ, Tack I, Lenz O, Striker GE, Striker LJ, Karl M. Expression and regulation of estrogen receptors in mesangial cells: influence on matrix metalloproteinase-9. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12:241–251. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V122241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rink TL. The gender gap. Occup Health Saf. 2004;73:179–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hu X, Wang Y, Lau CC. Effects of noise exposure on the auditory function of ovariectomized rats with estrogen deficiency. J Int Adv Otol. 2016;12:261–265. doi: 10.5152/iao.2016.2842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pillai JA, Siegel JH. Interaction of tamoxifen and noise-induced damage to the cochlea. Hear Res. 2011;282:161–166. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2011.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Petrie WK, Dennis MK, Hu C, Dai D, Arterburn JB, Smith HO, Hathaway HJ, Prossnitz ER. G protein-coupled estrogen receptor-selective ligands modulate endometrial tumor growth. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2013;2013:472720. doi: 10.1155/2013/472720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Breglio AM, et al. Cisplatin is retained in the cochlea indefinitely following chemotherapy. Nat Commun. 2017;8:1654. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01837-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Olgun Y, et al. Analysis of genetic and non genetic risk factors for cisplatin ototoxicity in pediatric patients. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;90:64–69. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2016.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yancey A, Harris MS, Egbelakin A, Gilbert J, Pisoni DB, Renbarger J. Risk factors for cisplatin-associated ototoxicity in pediatric oncology patients. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;59:144–148. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hu XJ, Li FF, Wang Y, Lau CC. Effects of cisplatin on the auditory function of ovariectomized rats with estrogen deficiency. Acta Otolaryngol. 2017;137:606–610. doi: 10.1080/00016489.2016.1261409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jiang M, Karasawa T, Steyger PS. Aminoglycoside-induced cochleotoxicity: a review. Front Cell Neurosci. 2017;11:308. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2017.00308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nakamagoe M, Tabuchi K, Uemaetomari I, Nishimura B, Hara A. Estradiol protects the cochlea against gentamicin ototoxicity through inhibition of the JNK pathway. Hear Res. 2010;261:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pooley AE, Luong M, Hussain A, Nathan BP. Neurite outgrowth promoting effect of 17-beta estradiol is mediated through estrogen receptor alpha in an olfactory epithelium culture. Brain Res. 2015;1624:19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2015.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Milon B, et al. The impact of biological sex on the response to noise and otoprotective therapies against acoustic injury in mice. Biol Sex Differ. 2018;9:12. doi: 10.1186/s13293-018-0171-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Thomas S, Munster PN. Histone deacetylase inhibitor induced modulation of anti-estrogen therapy. Cancer Lett. 2009;280:184–191. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wang J, Wang Y, Chen X, Zhang PZ, Shi ZT, Wen LT, Qiu JH, Chen FQ. Histone deacetylase inhibitor sodium butyrate attenuates gentamicin-induced hearing loss in vivo. Am J Otolaryngol. 2015;36:242–248. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lauer AM, Schrode KM. Sex bias in basic and preclinical noise-induced hearing loss research. Noise Health. 2017;19:207–212. doi: 10.4103/nah.NAH_12_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Villavisanis DF, Schrode KM, Lauer AM. Sex bias in basic and preclinical age-related hearing loss research. Biol Sex Differ. 2018;9:23. doi: 10.1186/s13293-018-0185-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tremblay AM, Giguere V. The NR3B subgroup: an ovERRview. Nucl Recept Signal. 2007;5:e009. doi: 10.1621/nrs.05009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ben Said M, et al. A novel missense mutation in the ESRRB gene causes DFNB35 hearing loss in a Tunisian family. Eur J Med Genet. 2011;54:e535–e541. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Collin RW, et al. Mutations of ESRRB encoding estrogen-related receptor beta cause autosomal-recessive nonsyndromic hearing impairment DFNB35. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:125–138. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bhatt I, Phillips S, Richter S, Tucker D, Lundgren K, Morehouse R, Henrich V. A polymorphism in human estrogen-related receptor beta (ESRRbeta) predicts audiometric temporary threshold shift. Int J Audiol. 2016;55:571–579. doi: 10.1080/14992027.2016.1192693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nolan LS, et al. Estrogen-related receptor gamma and hearing function: evidence of a role in humans and mice. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34(2077):e1–e9. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Schilit SL, et al. Estrogen-related receptor gamma implicated in a phenotype including hearing loss and mild developmental delay. Eur J Hum Genet. 2016;24:1622–1626. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2016.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chen J, Nathans J. Estrogen-related receptor beta/NR3B2 controls epithelial cell fate and endolymph production by the stria vascularis. Dev Cell. 2007;13:325–337. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Buniello A, et al. Wbp2 is required for normal glutamatergic synapses in the cochlea and is crucial for hearing. EMBO Mol Med. 2016;8:191–207. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201505523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Stefkovich ML, Arao Y, Hamilton KJ, Korach KS. Experimental models for evaluating non-genomic estrogen signaling. Steroids. 2018;133:34–37. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2017.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Dinh CT, Goncalves S, Bas E, Van De Water TR, Zine A. Molecular regulation of auditory hair cell death and approaches to protect sensory receptor cells and/or stimulate repair following acoustic trauma. Front Cell Neurosci. 2015;9:96. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yang CH, Schrepfer T, Schacht J. Age-related hearing impairment and the triad of acquired hearing loss. Front Cell Neurosci. 2015;9:276. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Fiocchetti M, Ascenzi P, Marino M. Neuroprotective effects of 17beta-estradiol rely on estrogen receptor membrane initiated signals. Front Physiol. 2012;3:73. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Iorga A, Cunningham CM, Moazeni S, Ruffenach G, Umar S, Eghbali M. The protective role of estrogen and estrogen receptors in cardiovascular disease and the controversial use of estrogen therapy. Biol Sex Differ. 2017;8:33. doi: 10.1186/s13293-017-0152-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lagranha CJ, Silva TLA, Silva SCA, Braz GRF, da Silva AI, Fernandes MP, Sellitti DF. Protective effects of estrogen against cardiovascular disease mediated via oxidative stress in the brain. Life Sci. 2018;192:190–198. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2017.11.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lean JM, Davies JT, Fuller K, Jagger CJ, Kirstein B, Partington GA, Urry ZL, Chambers TJ. A crucial role for thiol antioxidants in estrogen-deficiency bone loss. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:915–923. doi: 10.1172/JCI18859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lacort M, Leal AM, Liza M, Martin C, Martinez R, Ruiz-Larrea MB. Protective effect of estrogens and catecholestrogens against peroxidative membrane damage in vitro. Lipids. 1995;30:141–146. doi: 10.1007/BF02538267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mukai K, Daifuku K, Yokoyama S, Nakano M. Stopped-flow investigation of antioxidant activity of estrogens in solution. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1990;1035:348–352. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(90)90099-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Rao AK, Dietrich AK, Ziegler YS, Nardulli AM. 17beta-Estradiol-mediated increase in Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase expression in the brain: a mechanism to protect neurons from ischemia. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2011;127:382–389. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zhu X, Tang Z, Cong B, Du J, Wang C, Wang L, Ni X, Lu J. Estrogens increase cystathionine-gamma-lyase expression and decrease inflammation and oxidative stress in the myocardium of ovariectomized rats. Menopause. 2013;20:1084–1091. doi: 10.1097/GME.0b013e3182874732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bellanti F, Matteo M, Rollo T, De Rosario F, Greco P, Vendemiale G, Serviddio G. Sex hormones modulate circulating antioxidant enzymes: impact of estrogen therapy. Redox Biol. 2013;1:340–346. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Unfer TC, Figueiredo CG, Zanchi MM, Maurer LH, Kemerich DM, Duarte MM, Konopka CK, Emanuelli T. Estrogen plus progestin increase superoxide dismutase and total antioxidant capacity in postmenopausal women. Climacteric. 2015;18:379–388. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2014.964669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ada S, Hanci D, Ulusoy S, Vejselova D, Burukoglu D, Muluk NB, Cingi C. Potential protective effect of N-acetyl cysteine in acoustic trauma: an experimental study using scanning electron microscopy. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2017;26:893–897. doi: 10.17219/acem/64332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Feldman L, Efrati S, Eviatar E, Abramsohn R, Yarovoy I, Gersch E, Averbukh Z, Weissgarten J. Gentamicin-induced ototoxicity in hemodialysis patients is ameliorated by N-acetylcysteine. Kidney Int. 2007;72(3):359–363. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Marie A, et al. N-acetylcysteine treatment reduces age-related hearing loss and memory impairment in the senescence-accelerated Prone 8 (SAMP8) mouse model. Aging Dis. 2018;9(4):664–673. doi: 10.14336/AD.2017.0930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Redza-Dutordoir M, Averill-Bates DA. Activation of apoptosis signalling pathways by reactive oxygen species. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1863:2977–2992. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2016.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]