Abstract

Signal recognition particle (SRP) takes part in protein targeting and secretion in all organisms. Searches for components of archaeal SRP in primary databases and completed genomes indicated that archaea possess only homologs of SRP RNA, and proteins SRP19 and SRP54. A recombinant SRP was assembled from cloned, expressed and purified components of the hyperthermophilic archaeon Archaeoglobus fulgidus. Recombinant Af-SRP54 associated with the signal peptide of bovine pre-prolactin translated in vitro. As in mammalian SRP, Af-SRP54 binding to Af-SRP RNA required protein Af-SRP19, although notable amounts bound in absence of Af-SRP19. Archaeoglobus fulgidus SRP proteins also bound to full-length SRP RNA of the archaeon Methanococcus jannaschii, to eukaryotic human SRP RNA, and to truncated versions which corresponded to the large domain of SRP. Dependence on SRP19 was most pronounced with components from the same species. Reconstitutions with heterologous components revealed a significant potential of human SRP proteins to bind to archaeal SRP RNAs. Surprisingly, M.jannaschii SRP RNA bound to human SRP54M quantitatively in the absence of SRP19. This is the first report of reconstitution of an archaeal SRP from recombinantly expressed purified components. The results highlight structural and functional conservation of SRP assembly between archaea and eucarya.

INTRODUCTION

Signal recognition particle (SRP) is a ribonucleoprotein complex which serves to translocate secretory proteins across cellular membranes by recognizing signal sequences as they appear on the surface of translating ribosomes (for reviews see 1,2). SRP-directed protein targeting was elucidated first in eucarya (3–5) where the particle consisted of one SRP RNA molecule (∼300 nucleotides) and six proteins, named SRP9, SRP14, SRP19, SRP54, SRP68 and SRP72 according to their approximate molecular weights (6). Assembly of eucaryotic SRP occurred by binding of the SRP9/14 heterodimer to the small domain (7), whereas the other four SRP polypeptides were constituents of the large SRP domain (8,9). Protein SRP19 bound to helix 6 of SRP RNA which directed the association of SRP54 with helix 8 (10–13). SRP68 also interacted with SRP RNA and promoted binding of SRP72 (8). Only two molecules, 4.5S RNA and protein Ffh, a homolog of eucaryotic SRP54, were identified in bacterial SRP (14). However, recently, protein Hbsu was shown to be part of the Alu-like domain of Bacillus subtilis SRP (15).

Significant progress has been made in the detailed structural and functional characterization of bacterial and eucaryotic SRPs. Low-resolution models of SRP RNA were proposed based on chemical and enzymatic probing, site-directed mutagenesis and comparative sequence analysis (16,17). Crystal structures have been solved for the SRP9/14 heterodimer (18), the GTP-binding (NG)-domain of Escherichia coli SRP receptor (FtsY) (19), Thermus aquaticus Ffh (20,21) and the human methionine-rich domain of SRP54 (SRP54m) (22), thus enhancing our understanding of protein–SRP RNA and protein–signal peptide interactions on the molecular level.

In contrast, in archaea, relatively little is known about the role of SRP in protein targeting and secretion. All three domains of life (23) appear to contain proteins with signal sequences designed according to common principles (24) to indicate shared recognition mechanisms. In agreement with this assertion, archaeal SRP RNA secondary structures are similar to those of eucarya (14,25). Furthermore, genetic studies demonstrate the ability of archaeal SRP RNA genes to complement a deletion of the E.coli 4.5S RNA gene in vivo (26). The involvement of archaeal SRP-like particles in translation of membrane-associated proteins was demonstrated by co-sedimentation of Halobacterium halobium SRP RNA with polysomes programmed with bacterio-opsin mRNA (27). Moreover, SRP receptor (FtsY) homologs have been characterized in the archaea Thermococcus species AN1 (28) and Acidianus ambivalens (29,30).

Entire genome sequences of Methanococcus jannaschii, Pyrococcus horikoshii, Archaeoglobus fulgidus and Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum (31–34) provide inroads into the study of archaeal SRP. Here we describe cloning, expression, purification and assembly of A.fulgidus SRP from recombinant components. To address functional differences between A.fulgidus and mammalian SRP, we measured interactions of A.fulgidus SRP19 and SRP54 proteins with SRP RNAs of M.jannaschii and Homo sapiens, as well as binding of human SRP19 and SRP54M polypeptides to various SRP RNAs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning and in vitro synthesis of A.fulgidus SRP RNA

A plasmid with A.fulgidus SRP RNA gene under T7 promoter control was derived from a portion of the completed genome (33). The appropriate clone, distributed by the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), was obtained from The Institute for Genomic Research (TIGR). Two oligonucleotides for amplification were 5′-CGAATTCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGTGGGCTAGGCCGGGGG-3′ (the EcoRI restriction site and first transcribed guanosine are underlined) and 5′-CCTGGATCCTTTAAAGGTGGGCACGCCTCGGGTC-3′ to introduce DraI and BamHI restriction sites (underlined) for run-off transcription with T7 RNA polymerase. Amplifications were carried out in a Rapidcycler (Idaho Technology, Inc.) for 30 cycles with steps of 95, 65 and 72°C at each cycle and re-amplification of a 320 bp segment. The amplified DNA was separated by electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel, visualized with ethidium bromide and cut from the gel with a razor blade. DNA extraction was carried out by centrifugation through Whatman 3MM paper. The DNA was cleaved with EcoRI and BamHI, extracted with phenol–chloroform, ethanol precipitated and ligated to EcoRI and BamHI-digested pΔ35 DNA (35). Competent E.coli DH5α cells (Life Technologies) were transformed with ligated DNA, and transformants were selected on LB plates containing 100 µg/ml ampicillin by growth at 37°C. The correct pAfSR clone was chosen by screening plasmid DNAs from individual colonies prepared on small scale, characterized by restriction mapping and verified using Sequenase Version 2.0 (United States Biochemicals).

Run-off transcriptions were carried out in a volume of 20 µl for 2 h at 37°C with components of the T7-MEGAshortscript (Ambion) using DraI-restricted DNA. Transcription was terminated by adding 115 µl water, 15 µl of 5 M ammonium acetate and 2 vol ethanol. The sample was incubated at –20°C for 20 min, RNA was collected by centrifugation, washed with 80% ethanol and dissolved in 50 µl water. RNA concentrations were determined from a standard curve obtained with known amounts of E.coli 5S ribosomal RNA (Boehringer) by electrophoresis of sample aliquots on 2% agarose gels followed by staining with ethidium bromide. Approximate yields were 100 µg Af-SRP RNA (313 residues, 101 756 mol wt) per 1 µg DNA template.

Cloning, expression and purification of A.fulgidus SRP19

The gene for A.fulgidus SRP19 protein (Af-SRP19) was derived from a suitable genomic TIGR clone distributed by the ATCC. The SRP19 coding region was amplified with primers 5′-GGGGTGAGCATATGAAGGAGTGCGTTG-3′ and 5′-TCCGTAAGCTTCGGCAAGAACAAGAAC-3′ which contained NdeI and HindIII restriction sites (underlined). The expected fragment of ∼400 bp was obtained in 40 cycles with steps of 95°C for 30 s, 37°C for 2 min and 72°C for 2 min at each cycle in a Perkin Elmer-Cetus DNA thermocycler. The amplified DNA was digested with restriction enzymes NdeI and HindIII and ligated to plasmid pET23c (Novagen). Competent E.coli DH5α cells were transformed, plasmid DNAs from individual colonies were prepared on small scale, screened by restriction mapping and sequenced to confirm the pET-Af19 construct.

For protein expression, competent E.coli BL21(DE3-pLysE) cells (Novagen) were transformed with pET-Af19 DNA and colonies were selected at 37°C on LB agar plates containing ampicillin and chloramphenicol. Two 2 l Erlenmeyer flasks, 400 ml medium each, were inoculated with the colonies and incubated in a 37°C shaker until the A600 reached 0.9. A 20 l fermenter (Bioflow IV, New Brunswick Scientific), set to 37°C with aeration, was seeded. Protein expression was induced after 2.5 h by addition of IPTG (Gold Biotechnologies). Incubation was continued for 2 h, cells were harvested by centrifugation and the pellet (∼34 g wet packed cells) was frozen at –70°C. Expression of Af-SRP19 (104 residues, 12 405 mol wt) was confirmed by SDS–PAGE and staining with Coomassie blue G250.

For protein purification, 17 g of E.coli cells were resuspended in 110 ml of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 2 M urea, 300 mM NaCl, 5 mM DTT, 1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol). The suspension was frozen at –70°C, thawed slowly on ice and sonicated (Sonic Model 300, Fisher) five times for 15 s using 35% maximum output with 15 s between each pulse. The lysate was subjected to centrifugation at 10 000 r.p.m. for 10 min, and the resulting supernatant was spun at 30 000 r.p.m. for 4 h. The supernatant of the high-speed centrifugation was diluted with an equal volume of lysis buffer and loaded onto a Biorex 70 cation exchange column equilibrated in lysis buffer and connected to an FPLC system at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. The column was washed until the bulk of contaminating proteins appeared in the flowthrough. The urea was removed slowly by applying a linear gradient with a final buffer of 100 mM KPO4, pH 6.8, 300 mM NaCl, 5 mM DTT, 1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. The protein was eluted at ∼1.9 M salt using a gradient from 300 mM to 2.5 M NaCl in phosphate buffer. Aliquots of gradient fractions were analyzed by SDS–PAGE and staining with Coomassie blue G250. Fractions containing pure protein were pooled (a total volume of 40 ml), concentrated to 1.5 ml by centrifugation (3500 g; Centricon 10, Amicon). Finally, the protein was dialyzed against 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM DTT, 50% glycerol and stored at –20°C. The protein concentration was determined by SDS–PAGE on 15% gels of appropriately diluted aliquots followed by staining with Coomassie blue G250 in comparison with known amounts of lysozyme (Sigma). Yields were ∼2 mg of protein/g wet cells. As determined by SDS–PAGE, the purity of the protein preparation was ∼95%.

Cloning, expression and purification of A.fulgidus SRP54

A TIGR clone with the Af-SRP54 coding region was amplified using oligonucleotides 5′-GTTATATCCATGGCTCTTGAA-TCTC-3′ and 5′-GTCTTTCACACCAAGCTTTCTCAG-3′ in a Rapidcycler for 30 cycles with steps of 94, 45 and 72°C at each cycle. The 1420 bp fragment included NcoI and HindIII restriction sites (underlined) and was purified by electrophoresis in 1% agarose gels, followed by centrifugation through a 3MM paper filter. The extracted DNA was digested with NcoI and HindIII, recovered by phenol–chloroform treatment and ethanol precipitation and ligated to restricted vector pET19X (36). Colonies from transformed DH5α cells were grown on LB and ampicillin and used to prepare plasmid DNAs on a small scale. One pAfSRP54 clone was selected and verified using Sequenase Version 2.0.

For expression of A.fulgidus SRP54, competent BL21 (DE3) cells were transformed first with pSBETa, a plasmid which provides tRNA for rare arginine codons in E.coli (37). Transformants were selected on LB agar plates with 50 µg/ml kanamycin. Competent BL21 (DE3)-pSBETa cells were prepared by growth in LB with kanamycin followed by treatment with CaCl2 (38). The cells were transformed with pAfSRP54 DNA and selected overnight at 37°C on LB plates containing ampicillin and kanamycin. Four 2 l Erlenmeyer flasks, 200 ml medium each, were inoculated with fresh colonies at an A600 of ~0.1, and incubated in a 37°C shaker until the A600 reached ~0.5. For induction, IPTG (Diagnostic Chemicals Ltd, Oxford) was added to a final concentration of 1 mM. After 4 h of shaking at 37°C, the cultures were chilled on ice, cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4°C for 15 min at 6000 g, and the pellet (∼6 g wet cells) was frozen at –70°C. An aliquot of the sample was analyzed by SDS–PAGE to confirm the expression of A.fulgidus SRP54 (433 residues, 48 196 mol wt).

Cells were thawed on ice, resuspended in 80 ml phosphate buffer (50 mM NaPO4, 300 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 5 mM DTT, 10% glycerol) and sonicated (Sonic Model 300, Fisher Scientific) five times for 15 s using 35% maximum output with 15 s between each pulse. The lysate was subjected to centrifugation at 17 200 g for 10 min (Sorvall SS-34 rotor at 12 000 r.p.m.). The supernatant (∼80 ml) was collected and 2 vol lysis buffer lacking NaCl were added to reduce the salt concentration to 100 mM. The protein mixture was loaded onto a Biorex 70 column (total bed volume 138 ml) connected to an FPLC system (Pharmacia) equilibrated in phosphate buffer with 100 mM NaCl at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. The column was washed with 500 ml phosphate buffer (containing 100 mM salt) followed by a linear gradient from 100 mM to 2 M NaCl in phosphate buffer. Af-SRP54 eluted at a salt concentration of ∼1.5 M. Aliquots of gradient fractions were analyzed by SDS–PAGE followed by staining with Coomassie blue G250. Fractions containing pure Af-SRP54 were pooled (total volume of 9 ml) and concentrated by centrifugation (3500 g; Centricon 10, Amicon). Protein concentrations were determined by SDS–PAGE on 15% gels in comparison with known amounts of lysozyme. Yields were ∼1 mg Af-SRP54/g wet packed cells. The protein was ∼93% pure as determined by SDS–PAGE. For long-term storage at –20°C, the preparation was adjusted to 50% glycerol.

Isolation and purification of human SRP components

Human SRP RNA (301 nucleotides) was synthesized by run-off transcription of DraI-digested plasmid phR (35) using the T7-MEGAshortscript, essentially as described above for A.fulgidus SRP RNA. To obtain human Δ35-RNA, phΔ35 DNA (35) was digested with BamHI. Expression and purification of human SRP19 (hSRP19; 144 amino acids, 16 158 mol. wt) and hSRP54M (23 253 mol wt), the methionine-rich domain of protein SRP54 corresponding to residue position 297–504 of human SRP54, was as described (13,39).

Cloning and in vitro synthesis of M.jannaschii SRP RNA

The M.jannaschii SRP RNA gene was cloned under control of the T7 RNA polymerase promoter by amplification from a plasmid obtained from TIGR. Oligonucleotides were 5′-CGA-ATTCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGTGTGCATGGCTAG-GCC-3′ (the EcoRI restriction site and the first transcribed guanosine residue of the RNA are underlined) and 5′-CCTGG-ATCCTTTAAAGTGGTGTGCATGGC-3′ (DraI and BamHI restriction sites for run-off transcription with T7 RNA polymerase underlined). Amplifications were carried out in a Perkin Elmer thermocycler for 30 cycles with steps of 95, 65 and 72°C at each cycle. The amplified fragment was digested with appropriate restriction enzymes, cloned and the resulting plasmid pMjSR was confirmed by sequencing.

Plasmid pMjΔ35 containing the gene for the large domain of M.jannaschii SRP RNA was constructed in two steps. First, the 5′-portion of pMjSR was deleted using site-directed mutagenesis with mutagenic oligonucleotide 5′-CACGGGACGAGACCT-ATAGTGAGTCGTA-3′ and amplification conditions described previously for mutations in human SRP RNA (11). The resulting DNA (pMjΔ5) was used in a second step as a template with mutagenic oligonucleotide 5′-CTCTAGAGGATCCGTCCCGCACCCCCG-3′ to obtain pMjΔ35. After digestion with BamHI and run-off transcription with T7 RNA polymerase, pMjΔ35 produced the expected 140 nucleotide RNA (Mj-Δ35 RNA).

To increase RNA yields in the transcriptions, a derivative of pMjΔ35, designated as pMjΔ35A, with guanosine at the second position changed to an adenosine, was constructed using 5′-CGGGACGAGATCTATAGTGAGTC-3′ as mutagenic primer. pMjΔ35A was confirmed by sequencing and yielded an RNA (Mj-Δ35A RNA) of expected size.

Formation of SRP RNA–protein complexes

Archaeoglobus fulgidus, M.jannaschii or human SRP RNAs were incubated in 50 µl binding buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.9, 300 mM KOAc, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 10% glycerol) at appropriate concentrations (see Results) at 65°C for 10 min followed by gradual cooling to room temperature during ∼30 min. This renaturing step was omitted with human and M.jannaschii Δ35-RNAs. Small volumes of appropriately-diluted Af-SRP19, Af-SRP54, h-SRP19 or h-SRP54M proteins were added by gently mixing with a pipette tip followed by incubation at 37°C for 10 min.

RNA–protein complexes were bound to small DEAE columns or studied by mobility shift assay essentially as described (13,40). The assay was modified such that samples were loaded onto a 80 µl bed volume DEAE–Sepharose column (Fast flow, Pharmacia) equilibrated in 300 mM KOAc, 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.9, 5 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM DTT. Flowthrough and 50 µl of 300 mM KOAc-buffer wash were combined (flowthrough, F). Bound material was eluted with 100 µl buffer containing 1 M KOAc, 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.9, 5 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM DTT to yield 100 µl eluate (E). Polypeptides were precipitated with TCA, collected by centrifugation and analyzed on 15% SDS–polyacrylamide gels. Proteins were stained with Coomassie blue G250, the gels were destained and pictures were taken with a digital camera. The number of pixels in areas enclosing individual peaks were measured without image enhancements using NIH Image software (available on the Internet at http://rsb.info.nih.gov/nih-image/index.html ).

Formation of RNA–protein complexes was monitored by mobility shift on native gels. Reactions (10 µl) containing 200 ng SRP RNA were prepared in binding buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.9, 300 mM KOAc, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 10% glycerol) and 2 µl proteins, diluted appropriately in binding buffer, were added by gentle mixing with the pipette tip, followed by incubation at 37°C for 5 min. Samples were loaded without tracking dye onto 6% polyacrylamide gels containing 20 mM HEPES, 0.1 mM EDTA, pH 8.3 (41). Electrophoresis was carried out at 10 mA until the bromophenol blue (loaded in separate slot) had traveled ∼15 cm. The RNAs were stained with 1 µg/ml ethidium bromide for 10 min and the picture, taken on a UV transilluminator, was used for quantitative analysis using NIH-Image software.

Cross-link to mammalian signal peptide

In vitro transcription and translation of bovine pre-prolactin mRNAs were carried out essentially as described (42). Truncated mRNAs were translated in rabbit reticulocyte lysates, and ribosome/nascent chain complexes were recovered by centrifugation as described (43). To strip endogenous ribosome-associated components, the translation solution was mixed with 2 vol of 950 mM KOAc in buffer A (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 5 mM MgOAc, 1 mM DTT, 0.4 U/µl placental RNase inhibitor, 0.1 µg/ml antipain, 10 U/ml aprotinin, 0.1 µg/ml chymostatin, 0.1 µg/ml leupeptin, 0.1 µg/ml pepstatin and 0.5 mM cycloheximide) and loaded on top of 2 vol of a high-salt sucrose cushion (0.5 M sucrose and 700 mM KOAc in buffer A) and spun at 100 000 r.p.m. for 20 min (Beckman rotor TLA100). Photocrosslinking using photoactivatable TDBA [4-(3-trifluoromethyl-diazirino)benzoic acid]-modified lys-tRNA was carried out according to Görlich et al. (44).

RESULTS

Search for archaeal SRP components

Archaeal SRP RNAs were found in the primary databases (45,46) using BLAST (47) with known representative sequences obtained from the SRP database (14). In addition, common secondary structure motifs which corresponded to SRP RNA helix 8 were used as input to PatScan (http://www-unix.mcs.anl.gov/compbio/PatScan/ ). The results from both searches identified a total of 12 archaeal SRP RNA sequences. In BLAST searches for archaeal SRP proteins new homologs of proteins SRP19 and SRP54 were identified in Pyrococcus abysii and Aeropyrum pernix. At present, six archaeal SRP19- and eight SRP54-related protein sequences are known.

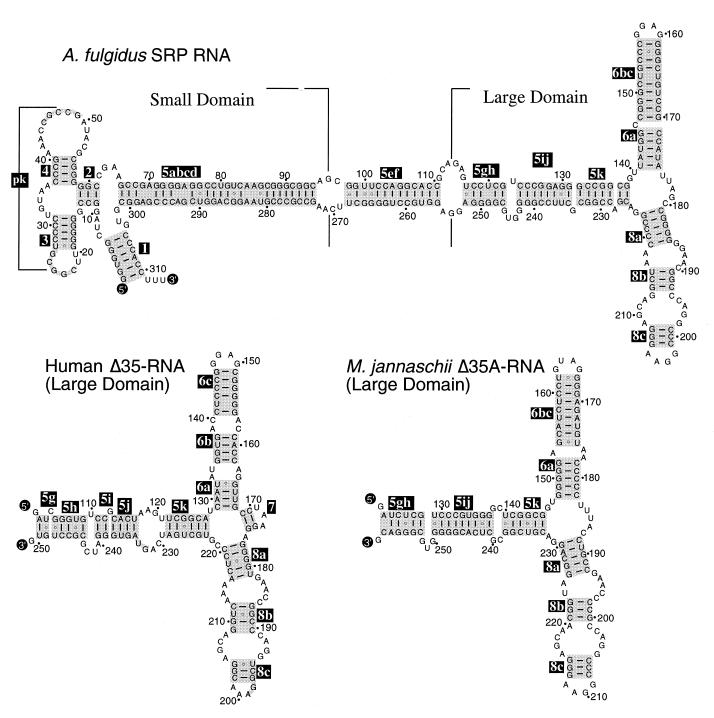

SRP RNA secondary structures of archaea and eucarya were similar (2,14) (Fig. 1) and contained RNA binding sites for SRP9/14, SRP19, SRP54 and SRP68. However, comprehensive searches failed to identify archaeal homologs to proteins SRP9/14, SRP68 and SRP72. Furthermore, close inspection of four completed archaeal genome sequences (31–34), suggested that the SRPs of these archaeal species consist only of one SRP RNA molecule and two proteins, SRP19 and SRP54.

Figure 1.

Secondary structures of A.fulgidus SRP RNA and Δ35 RNAs of H.sapiens and M.jannaschii. Secondary structures are shown with base pairings supported by comparative sequence analysis of SRP RNA sequences in the SRP database (14). 5′- and 3′-ends of RNA molecules are labeled as such; helices are numbered 2–8 according to the nomenclature of Larsen and Zwieb (25). Base paired sections of helices 5, 6 and 8, including regions of coaxial stacking (48), are highlighted in gray and labeled in reverse print with suffices a–k in helix 5, and a–c in helices 6 and 8. Residues are numbered in 10-nucleotide increments and marked with dots in 10-nucleotide increments in reference to full-length molecules.

SRP RNA secondary structures

The secondary structure of A.fulgidus SRP RNA (Fig. 1, top), was derived by comparative sequence analysis to include phylogenetically supported base pairs (25). As in SRP RNAs of other archaea, helices 2–6 and helix 8 of Af-SRP RNA were shared with eucaryotic SRP RNAs, there was an added helix 1, and helix 7 was absent. Some of these features of Af-SRP RNA secondary structure and the Δ35 RNAs of H.sapiens and M.jannaschii are compared in Figure 1.

Synthesis of A.fulgidus SRP RNA

To obtain A.fulgidus SRP RNA, the gene was cloned under control of the T7 RNA polymerase promoter as described in Materials and Methods. An RNA of expected size was transcribed in vitro as judged by electrophoresis on native polyacrylamide gels. A homogeneous population of conformers (see Fig. 5) was obtained by heating Af-SRP RNA to 65°C followed by gradual cooling to room temperature.

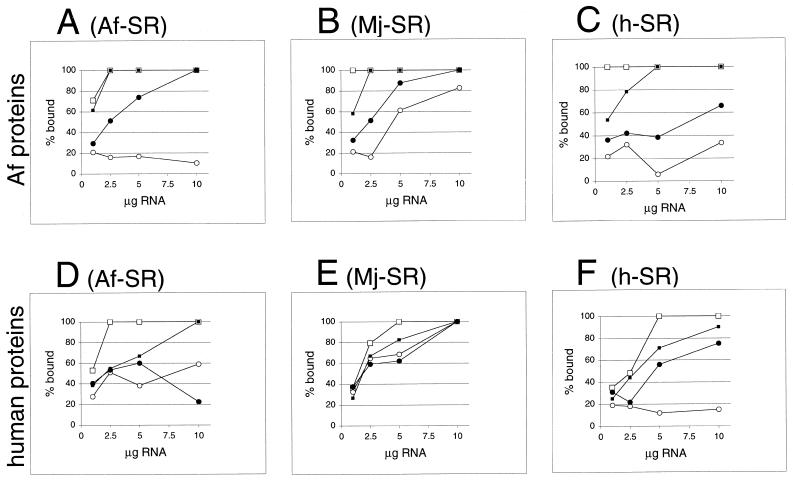

Figure 5.

Formation of A.fulgidus SRP by mobility shift. Electrophoresis of SRP RNA–protein complexes on 6% native polyacrylamide gels. The nucleic acids were stained with ethidium bromide. (A) Binding of purified Af-SRP19 to Af-SRP RNA. Each reaction contained 200 ng RNA. Protein was added at RNA/protein molar ratios of 0.082 (lane 2), 0.21 (lane 3), 0.41 (lane 4), 0.61 (lane 5), 0.82 (lane 6) and 1.6 (lane 7). The sizes of double-stranded DNA fragments (HaeIII-digested ΦX174 DNA) used for reference (lanes M) are indicated in base pairs on the left. (B) Quantitative analysis of Af-SRP19 binding to Af-SRP RNA by mobility shift as shown in (A). (C) Binding of Af-SRP19 and Af-SRP54 to various SRP RNAs. Lane 1, 200 ng Δ35-SRP RNA of M.jannaschii (Mj-Δ35); lane 2, 200 ng human Δ35-SRP RNA (h-Δ35); lane 3, 200 ng full-length A.fulgidus SRP RNA (Af-SRP); lane 4, 200 ng Af-SRP with 60 ng Af-SRP19 protein; lane 5, 200 ng Af-SRP with 700 ng Af-SRP54; lane 6, mixture of Mj-Δ35, h-Δ35 and Af-SRP RNA with amounts identical to those used in lanes 1–3; lane 7, RNA mixture as in lane 6 with the addition of 60 ng Af-SRP19; lane 8, RNA mixture as in lane 6 with the addition of 700 ng Af-SRP54; lane 9, RNA mixture as in lane 6 with addition of 60 ng Af-SRP19 and 700 ng Af-SRP54. Sizes of double-stranded DNA fragments used for reference (lanes M) are indicated in base pairs on the left.

Cloning, expression and purification of A.fulgidus SRP19 and SRP54

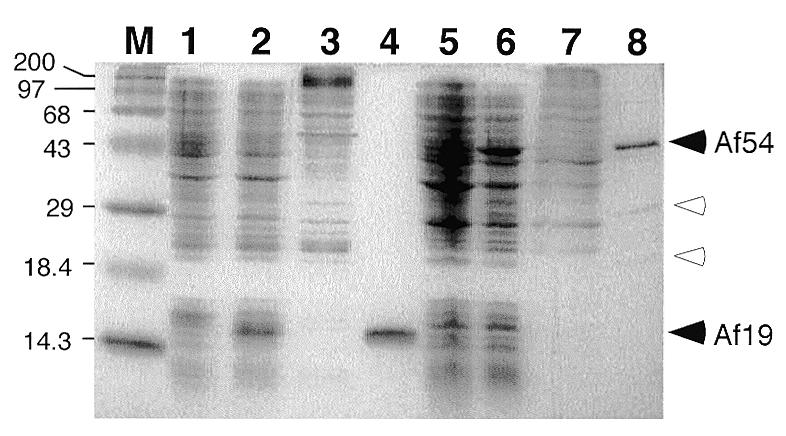

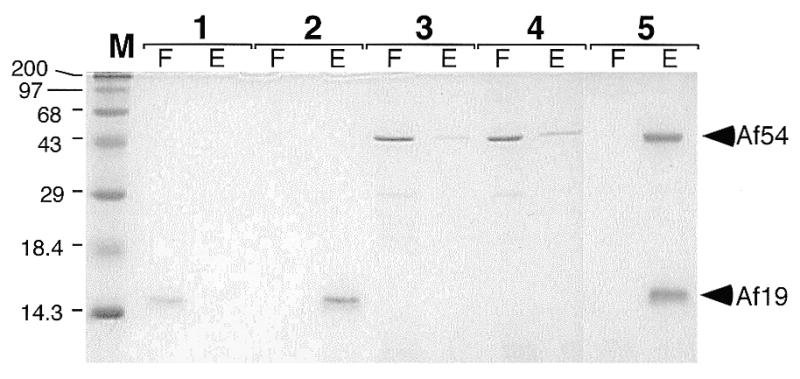

The gene for A.fulgidus SRP19 protein (Af-SRP19) was inserted into a vector for expression in E.coli (see Materials and Methods). Figure 2, lane 2, demonstrates expression level of Af-SRP19 after induction with IPTG. The calculated molecular weight of the predicted polypeptide was 12 405 Da, but Af-SRP19 migrated at ∼15 kDa possibly due to its basic character (theoretical pKi = 11.05). After cell lysis, the over-expressed Af-SRP19 was solubilized in buffer containing 2 M urea and loaded onto a cation exchange column. Urea was removed by gradual buffer change and essentially pure protein was eluted at a salt concentration of 1.9 M (Fig. 2, lane 4). The preparation yielded only active polypeptides as indicated by their quantitative association with RNA (Fig. 3, lane 2).

Figure 2.

Expression and purification of A.fulgidus SRP19 and SRP54. Proteins were separated on 15% SDS–polyacrylamide gels and stained with Coomassie blue. M, pre-stained high molecular weight markers (Gibco BRL) with sizes indicated in kDa. Lane 1, protein extract from uninduced E.coli BL21(DE3-pLysE) cells; lane 2, proteins from cells induced with IPTG for 2 h; lane 3, flowthrough from cation exchange chromatography; lane 4, pooled high-salt eluate; lane 5, protein extract from uninduced E.coli BL21(DE3-pSBETa) cells; lane 6, protein extract after induction with IPTG for 4 h; lane 7, flowthrough of Biorex 70 column; lane 8, pooled high-salt eluate. Solid arrowheads indicate positions of proteins Af-SRP54 (Af54) and Af-SRP19 (Af19), respectively. Open arrowheads mark Af-SRP54-derived polypeptides with predicted molecular weights of 30 359 and 17 855, likely a result of proteolytic cleavage likely occurring between the G- and M-domain of Af-SRP54 (29,43).

Figure 3.

SRP RNA binding activities of Af-SRP19 and Af-SRP54 proteins. Proteins separated by electrophoresis on 15% polyacrylamide gels and stained with Coomassie blue in the flowthrough (F) and high-salt eluate (E) of DEAE-columns (see Materials and Methods). Lane 1, 1 µg Af-SRP19 in absence of Af-SRP RNA; lane 2, 1 µg Af-SRP19 mixed with 10 µg Af-SRP RNA; lane 3, 3.8 µg Af-SRP54 in absence of Af-SRP RNA; lane 4, 3.8 µg Af-SRP54 added to 10 µg Af-SRP RNA; lane 5, 1 µg Af-SRP19 and 3.8 µg Af-SRP54 with 10 µg of Af-SRP RNA. Pre-stained high molecular weight markers (Gibco BRL) with sizes indicated in kDa in lane M.

The Af-SRP54 coding region was amplified and inserted into a pET-expression vector as described in Materials and Methods. For enhanced translation of recombinant Af-SRP54, pSBET was transformed into E.coli to provide tRNA for rare arginine codons (37). Figure 2 demonstrates synthesis of an ∼45 kDa polypeptide in IPTG-treated cells, consistent with the predicted molecular weight of 48 196 Da. Purification procedures for Af-SRP54 were similar to those of Af-SRP19, but urea was omitted (see Materials and Methods). Essentially pure Af-SRP54 eluted from the cation-exchange column at ∼1.5 M (Fig. 2, lane 8). Minor amounts of two smaller polypeptides observed by SDS–PAGE were most likely derived from a hypersensitive proteolytic cleavage between the G- and M-domains of archaeal SRP54 (29). RNA binding assays (described below) indicated that only active Af-SRP54 molecules were obtained (Fig. 3, lane 5).

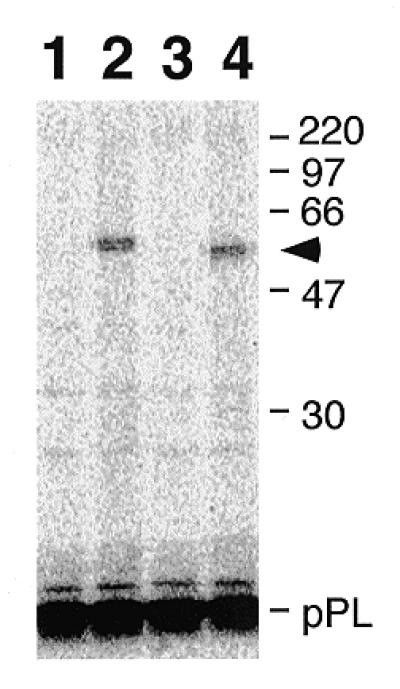

Cross-link between A.fulgidus SRP54 and mammalian signal peptide

An SRP binding assay and an established photo-crosslinking method were combined to demonstrate the functional activity of purified Af-SRP54 in a mammalian cell-free translation system. A truncated mRNA encoding the first 86 amino acids of pre-prolactin was translated in vitro to produce stable ribosome-associated nascent chain complexes. The polypeptide was labeled with [35S]methionine and modified at lysine positions with the photoactivatable crosslinker TDBA. After translation, ribosomes were reisolated to ensure that only SRP54 bound to the nascent chain complexes was investigated. Upon irradiation, nascent pre-prolactin attached covalently to Af-SRP54 as indicated by SDS–PAGE and fluorography (Fig. 4, lane 4). The protein concentration to obtain maximal crosslinking was estimated to be 0.2 µM. In titration experiments with variable amounts of protein, the minimum concentration for detection of cross-linked Af-SRP54 was 5 nM and within the range observed with canine SRP54 (not shown).

Figure 4.

Photoaffinity labeling of purified Af-SRP54 with signal peptide. TDBA-modified lysine-tRNA was incorporated into the 86 amino acid residue bovine pre-prolactin (pPL) signal by translation in vitro (54) and used for photo cross-linking. The high-salt stripped nascent polypeptide–ribosome complex was mixed with either canine SRP54 or Af-SRP54 followed by centrifugation through a sucrose cushion. The radioactively labeled polypeptides were separated by SDS–PAGE on 12% gels and subjected to fluorography. Lane 1, non-irradiated pPL in the presence of canine SRP54; lane 2, irradiated pPL in the presence of canine SRP54; lane 3, non-irradiated pPL in the presence of recombinant Af-SRP54; lane 4, irradiated pPL in the presence of Af-SRP54. The arrowhead marks the position of Af-SRP54 cross-linked to the truncated (86 amino acid residues) pPL. Marker proteins with molecular weights in kDa are shown on the right.

Assembly of A.fulgidus SRP

To form ribonucleoprotein complexes between Af-SRP and the two A.fulgidus SRP proteins, the RNA was renatured in binding buffer by heating to 65°C followed by slow cooling to room temperature. Preliminary experiments determined that an 80 µl bed-volume DEAE-column bound >90% of the applied RNA. Proteins were added individually in equimolar concentrations in the absence or presence of 10 µg Af-SRP RNA (Fig. 3, lanes 2–4), or proteins were added simultaneously (lane 5). Without Af-SRP RNA, protein Af-SRP19 appeared in the flowthrough quantitatively, and the majority of Af-SRP54 was recovered in the flowthrough. With Af-SRP RNA present, Af-SRP19 formed a complex which bound to DEAE in 300 mM KOAc buffer and eluted at 1 M KOAc (see Materials and Methods). A slight, but reproducible, enhancement above the background level of 3–10% was observed with Af-SRP54 even in the absence of Af-SRP19 to indicate a weak affinity. Identical results were obtained when tRNA was used in the control reactions, thus demonstrating the SRP RNA specificity of this reaction (not shown). Complete binding of both proteins was achieved by their simultaneous addition as indicated by their appearance in the high-salt eluate (Fig. 3, lane 5E).

For direct observation of protein–RNA complexes, samples were loaded onto native polyacrylamide gels. Figure 5A shows the formation of the complex between Af-SRP19 and Af-SRP RNA during addition of increasing amounts of protein. Because of the non-equilibrium conditions of the mobility shift assay, the ability of the polyacrylamide gel matrix to influence the stability of the complex, and the cooperative nature of the binding reaction (39), the equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd) was not determined. However, it was noticed that 21 ng protein was required to bind 200 ng SRP RNA in order to achieve 50% binding (Fig. 5B), corresponding to an RNA/protein molar ratio of 0.86.

Next, we compared interactions between Af-SRP RNA and A.fulgidus proteins with affinities to SRP RNAs of M.jannaschii (Mj-SRP RNA) and H.sapiens (h-SRP RNA) in the same reaction. We used Δ35 versions of Mj-SRP RNA and human SRP RNA (Fig. 1) (see Materials and Methods) because these smaller derivatives migrated different from each other on native 6% polyacrylamide gels and separated well from full-length Af-SRP RNA (Fig. 5C, lanes 1–3). Unlike with Af-SRP RNA, heating and slow cooling of the Δ35-RNAs was avoided, as this treatment formed significant amounts of dimers which co-migrated with Af-SR (not shown). Figure 5C shows typical results obtained in incubations of isolated Af-SRP RNA, or a mixture of three RNAs, with A.fulgidus SRP proteins, alone or in combination. Enough Af-SRP19 was added to Af-SRP RNA to predominantly form complexes (Fig. 5C, lane 4). When the same amount of Af-SRP19 was used with the mixture of RNA, slightly less complex was formed. Consistent with this finding, the amounts of free Δ35 RNAs were reduced for h-Δ35 and Mj-Δ35 RNA indicating that Af-SRP19 could interact with the three different RNA molecules.

We were unable to observe a sharp band corresponding to the complex between Af-SRP54 and Af-SR. Nevertheless, this interaction was indicated by the reduced intensity of free RNA (Fig. 5C, lane 5). A corresponding decrease in the amounts of free Mj-Δ35 and h-Δ35 RNAs (Fig. 5C, lane 8) showed that Af-SRP54 not only bound to its own SRP RNA, but also, to a lesser degree, to both Δ35 RNAs. As in the DEAE-binding experiments, binding of Af-SRP54 to Af-SRP RNA was enhanced specifically in the presence of Af-SRP19 to form A.fulgidus SRP (Fig. 5C, lane 9).

Binding of Af-SRP19 and Af-SRP54 to full-length M.jannaschii and human SRP RNAs

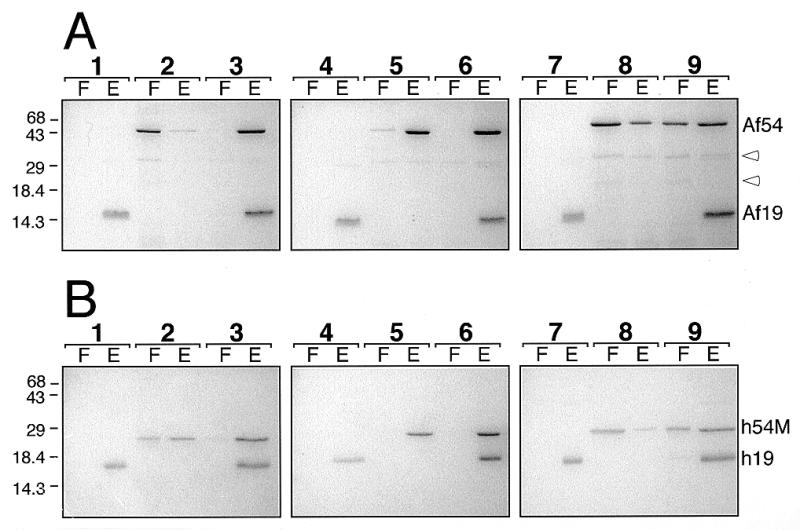

Similar to results obtained in studies of human SRP assembly (13), A.fulgidus SRP19 strongly promoted the binding of AF-SRP54. However, both DEAE assay and mobility shift analysis, described above, also indicated a direct interaction between Af-SRP and Af-SRP54. We investigated in parallel experiments if this was a unique property of the A.fulgidus SRP, or if a similar behavior was observed with other archaeal or mammalian SRP RNAs. Full-length SRP RNAs of M.jannaschii and H.sapiens were produced by run-off transcription as described in Materials and Methods and incubated with Af-SRP19 and Af-SRP54 either individually or with a mixture of both polypeptides. Complexes were loaded on DEAE columns and proteins recovered in flowthrough and 1 M KOAc buffer eluate were analyzed by SDS–PAGE. In the absence of Af-SRP19, the majority of Af-SRP54 was in the flowthrough (Fig. 6A, lane 2). Af-SRP54 bound to Af-SRP RNA quantitatively upon addition of Af-SRP19. Replacing Af-SRP RNA with Mj-SRP RNA bound most of the Af-SRP54, and, again, quantitative binding was achieved upon addition of Af-SRP19. Similar, but less pronounced, SRP19-independent binding was observed in reactions of A.fulgidus SRP proteins with human SRP RNA (Fig. 6, lane 8) but was enhanced by Af-SRP19.

Figure 6.

Assembly with proteins of A.fulgidus or human SRP. (A) Binding of 1 µg Af-SRP19 and 3.8 µg Af-SRP54 polypeptides to 10 µg Af-SRP RNA (lanes 1–3), 10 µg Mj-SRP RNA (lanes 4–6) or 10 µg human SRP RNA (lanes 7–9). (B) Binding of 1.3 µg human SRP19 and 2 µg human SRP54M polypeptides to 10 µg Af-SRP RNA (lanes 1–3), 10 µg Mj-SRP RNA (lanes 4–6) or 10 µg human SRP RNA (lanes 7–9). Each panel shows polypeptides in the flowthrough (F) and eluate (E) as determined in DEAE binding assays (see Materials and Methods) followed by electrophoresis of polypeptides on 15% polyacrylamide gels and staining with Coomassie blue. Lanes 1, 4 and 7, addition of SRP19; lanes 2, 5 and 8, addition of Af-SRP54 or human SRP54M; lanes 3, 6 and 9, addition of both Af-SRP19 and Af-SRP54 (A) or human SRP19 and human SRP54M (B). Mobilities of Af-SRP54 (Af54), Af-SRP19 (Af19), human SRP19 (h19) and human SRP54M (h54M) polypeptides are indicated on the right. Open arrowheads in (A) mark two proteolytic products of Af-SRP54. Migration distances of molecular weight markers with sizes in kDa are indicated on the left.

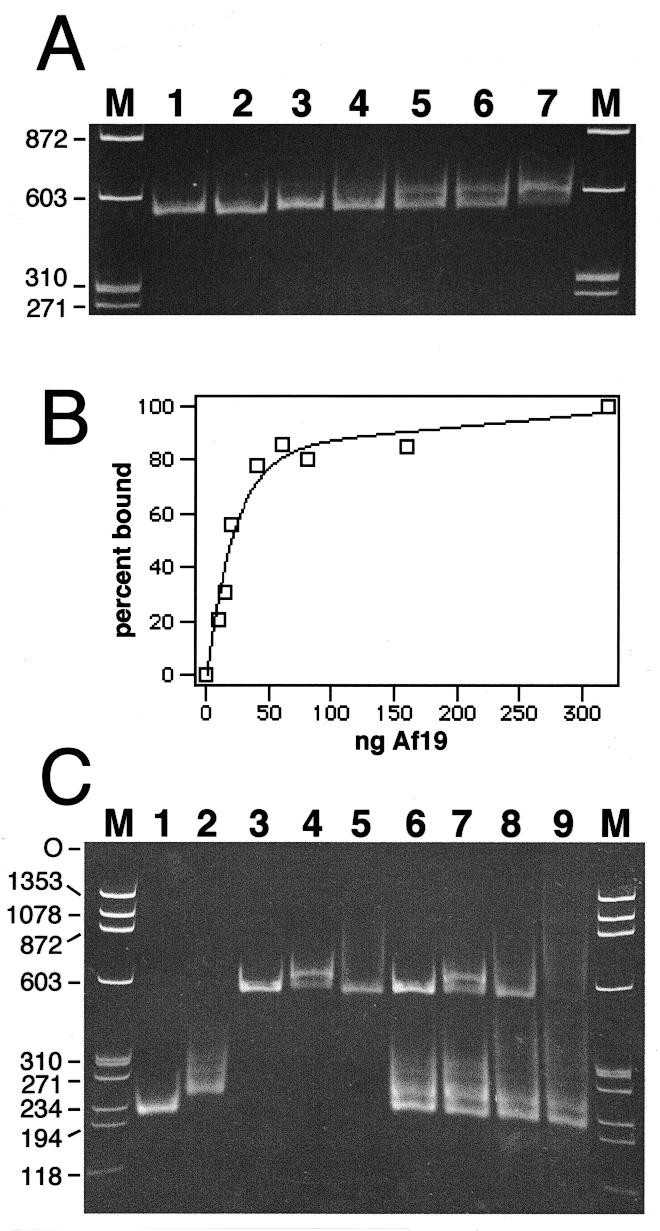

For semi-quantitative assessment of SRP-independent binding of Af-SRP54, reactions were carried out with variable amounts of Af-SRP RNA, Mj-SRP RNA or human SRP RNA as indicated in Figure 7. Protein amounts in flowthrough and eluate of DEAE columns were measured by scanning of SDS gels. Over the range of RNA concentrations used (Fig. 7A–C), Af-SRP19-independent binding of Af-SRP54 was minor with Af-SRP RNA, predominant with Mj-SRP RNA and intermediate with human SRP RNA. In all cases, binding of Af-SRP54 was enhanced by Af-SRP19. No significant differences in binding of Af-SRP19 to the various SRP RNAs were observed.

Figure 7.

Formation of ribonucleoprotein particles with A.fulgidus, M.jannaschii or human SRP RNAs. Activity of A.fulgidus SRP proteins (A–C) or human SRP proteins (D–F) with variable amounts of SRP RNAs of A.fulgidus (A) and (D), M.jannaschii (B) and (E) or H.sapiens (C) and (F) measured in the DEAE affinity assays (see Materials and Methods) from the intensity of Coomassie blue-stained polypeptides separated by SDS–PAGE as shown in Figure 6. Binding of SRP19 proteins is indicated by lines connected to open squares; open circles mark binding of Af-SRP54 (A–C) or human SRP54M (D–F). Solid squares indicate binding of SRP19 in presence of Af-SRP54 or human SRP54M; solid circles show binding of Af-SRP54 or human SRP54M in presence of SRP19. Small amounts of background binding observed without RNA or in presence of tRNA in the range of 3–10% observed with Af-SRP54 or human SRP54M (see Results) were plotted. Equimolar protein concentrations were 1 µg Af-SRP19, 3.8 µg Af-SRP54, 1.3 µg human SRP19 and 2 µg human SRP54M per 50 µl reaction volume.

Binding of human SRP19 and SRP54M proteins to M.jannaschii and A.fulgidus SRP RNAs

To investigate the possibility that a unique property of Af-SRP54 might permit independent binding to phylogentically distant SRP RNAs, we studied binding capacities of human SRP19 and SRP54M to Af-SRP RNA, Mj-SRP RNA and human SRP RNA. We used SRP54M, which corresponded to the methionine-rich M-domain of human SRP54, because this shorter polypeptide expressed well and retained its RNA binding activity (13).

Figure 6B shows that human SRP19 bound to the three different SRP RNAs quantitatively but was slightly less active than its archaeal homolog (compare panels B and C with E and F in Fig. 7). Greater than 50% of human SRP54M bound to Af-SRP RNA independently, and human SRP19 enhanced binding of SRP54M for complete binding (Fig. 7D). Surprisingly, quantitative binding was observed between human SRP54M and Mj-SRP RNA in the absence of SRP19 (Fig. 7E). As expected, SRP54M bound to its own (human) RNA weakly at background levels (13), but almost completely after addition of human SRP19. Af-SRP54 or human SRP54 bound effectively (>30%) when SRP RNAs were from another species, leading to the conclusion that the SRP19-dependence of the assembly was most pronounced when the components were from the same species.

DISCUSSION

Little is known about SRP-mediated protein secretion in archaea. The ability of A.fulgidus SRP54 to cross-link to a eucaryotic signal peptide and bind SRP RNA by a SRP19-controlled mechanism supported the assumption that protein translocation in archaea and eucarya is similar. Components identified in primary databases and completed genomes indicated that archaea SRP occupies an intermediate position between the two other domains of life because SRP RNA secondary structures of eucarya and archaea were very similar and indicated the presence of RNA binding sites for proteins SRP9/14 and SRP68. However, four out of six homologs to eucaryotic SRP proteins were undetectable in the completed archaea genomes, despite the fact that all other essential constituents of the secretion pathway (SRP RNA, SRP54, SRP receptor and ribosomal components) were present. The possibility that additional archaeal SRP proteins will be discovered could not be excluded, but these hypothetical polypeptides would be expected to deviate significantly from known primary structures of SRP9/14, SRP68 or SRP72 (14).

The need for an archaeal protein SRP19 may be linked to helix 6, which is present in all known archaeal SRP RNAs and was the predominant binding site for SRP19 in human SRP (11,35). SRP9/14 appears to stabilize a pseudoknot in the small SRP domain (2) involving the loops of helices 3 and 4 (labeled ‘pk’ in Fig. 1), but it is conceivable that this function is accomplished by RNA alone. In agreement with this possibility, an area suggested to be occupied by SRP9/14 in mammalian SRP (2) contained a portion of the M.jannaschii SRP RNA (48).

Although SRP68 and SRP72 were shown to be essential for mammalian SRP function in vitro (49), it is conceivable that signal peptide recognition is mediated by SRP RNA and SRP54 alone, as is the case in bacteria. The prominent role of these two molecules is underscored by their high degree of conservation, and close proximity of SRP54 to both SRP RNA and signal peptide (13,50,51).

Ability of Af-SRP19 to bind to M.jannaschii and human RNA, as well as binding of human SRP19 to archaeal SRP RNAs emphasized conservation of this important initial step in SRP assembly. The slightly less efficient binding of both SRP19 polypeptides to human SRP RNA was likely due to its conformational flexibility (39,52,53) which was absent in archaeal SRP RNAs.

In heterologous reconstitutions with components from species that were either closely related to A.fulgidus or more distant, SRP54 showed marked affinity to SRP RNA even in the absence of protein SRP19. This was most pronounced in combination of human SRP54M with M.jannaschii SRP RNA, and demonstrated an intrinsic ability of SRP54 to bind SRP RNA completely without SRP19. Full-length SRP RNA and Δ35 RNAs produced similar results (not shown). Thus, the protein binding capacity was probably localized within the large SRP domain (8,9). Detailed interpretation of results obtained in heterologous binding reactions was difficult because it was unclear if two proteins bound to the same RNA molecule. Furthermore, as indicated in Figure 7D, human SRP54M appeared to compete with human SRP19 in the binding to A.fulgidus SRP RNA. Using sucrose gradient centrifugation, we were unable to observe interactions between SRP19 and SRP54 in the absence of SRP RNA (not shown), indicating that these effects may be mediated by the RNA. It remains to be investigated if differences in RNA primary structure were responsible, or if conformational changes control binding of SRP54. Whatever the assembly mechanism might be, SRP19-dependence of SRP54 binding was most pronounced in systems (A.fulgidus or human) where components were from the same species. This finding indicated a requirement for tight control of SRP54 binding in assembly and/or function of SRP.

In summary, the results demonstrate that the assembly pathways of archaeal and eucaryal SRPs are similar and may follow similar conserved rules. Furthermore, the cloning, predominant expression, simple purification, and effortless reconstitution of A.fulgidus SRP is expected to facilitate development of an archaeal cell-free protein translation–translocation assay.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Kimberly Chittenden for assistance with binding assays, Jiaming Yin for critical reading of the manuscript, and Martin Wiedmann for advice on photoaffinity labeling with nascent signal peptides. S.H.B. is on research leave from the Department of Microbiology, University of Dhaka, Bangladesh. This work was supported by NIH grant GM-49034 to C.Z.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lütcke H. (1995) Eur. J. Biochem., 228, 531–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bui N. and Strub,K. (1999) Biol. Chem., 380, 135–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walter P. and Blobel,G. (1981) J. Cell Biol., 91, 551–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walter P., Ibrahimi,I. and Blobel,G. (1981) J. Cell Biol., 91, 545–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walter P. and Blobel,G. (1981) J. Cell Biol., 91, 557–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walter P. and Blobel,G. (1983) Cell, 34, 525–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strub K. and Walter,P. (1990) Mol. Cell Biol., 10, 777–784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siegel V. and Walter,P. (1988) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 85, 1801–1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Samuelsson T. (1992) Nucleic Acids Res., 20, 5763–5770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Römisch K., Webb,J., Lingelbach,K., Gausepohl,H. and Dobberstein,B. (1990) J. Cell Biol., 111, 1793–1802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zwieb C. (1992) J. Biol. Chem., 267, 15650–15656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zwieb C. (1993) Eur. J. Biochem., 222, 885–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gowda K., Chittenden,K. and Zwieb,C. (1997) Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 388–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zwieb C. and Samuelsson,T. (2000) Nucleic Acids Res., 28, 171–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakamura K., Yahagi,S., Yamazaki,T. and Yamane,K. (1999) J. Biol. Chem., 274, 13569–13576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zwieb C., Müller,F. and Larsen,N. (1996) Folding Des., 1, 315–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zwieb C. and Müller,F. (1997) Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser., 36, 69–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Birse D.E., Kapp,U., Strub,K., Cusack,S. and Aberg,A. (1997) EMBO J., 16, 3757–3766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Montoya G., Svennssom,C., Luirink,J. and Sinning,I. (1997) Nature, 385, 365–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freymann D.M., Keenan,R.J., Stroud,R.M. and Walter,P. (1997) Nature, 385, 361–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keenan R.J., Freymann,D.M., Walter,P. and Stroud,R.M. (1998) Cell, 94, 181–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clemons W.M. Jr, Gowda,K., Black,S.D., Zwieb,C. and Ramakrishnan,V. (1999) J. Mol. Biol., 292, 697–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Woese C.R., Kandler,O. and Wheelis,M.L. (1990) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 87, 4576–4579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.von Heijne G. (1990) J. Membr. Biol., 115, 195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Larsen N. and Zwieb,C. (1991) Nucleic Acids Res., 19, 209–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown S. (1991) J. Bacteriol., 173, 1835–1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gropp R., Gropp,F. and Betlach,M.C. (1992) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 89, 1204–1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ronimus R.S. and Musgrave,D.R. (1997) Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1351, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moll R., Schmidtke,S. and Schafer,G. (1999) Eur. J. Biochem., 259, 441–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moll R., Schmidtke,S., Petersen,A. and Schafer,G. (1997) Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1335, 218–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bult C.J., White,O., Olsen,G.J., Zhou,L., Fleischmann,R.D., Sutton,G.G., Blake,J.A., FitzGerald,L.M., Clayton,R.A., Gocayne,J.D., Kerlavage,A.R., Dougherty,B.A., Tomb,J.F., Adams,M.D., Reich,C.I., Overbeek,R., Kirkness,E.F., Weinstock,K.G., Merrick,J.M., Glodek,A., Scott,J.L., Geoghagen,N.S.M. and Venter,J.C. (1996) Science, 273, 1058–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kawarabayasi Y., Sawada,M., Horikawa,H., Haikawa,Y., Hino,Y., Yamamoto,S., Sekine,M., Baba,S., Kosugi,H., Hosoyama,A., Nagai,Y., Sakai,M., Ogura,K., Otsuka,R., Nakazawa,H., Takamiya,M., Ohfuku,Y., Funahashi,T., Tanaka,T., Kudoh,Y., Yamazaki,J., Kushida,N., Oguchi,A., Aoki,K. and Kikuchi,H. (1998) DNA Res., 5, 55–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klenk H.P., Clayton,R.A., Tomb,J.F., White,O., Nelson,K.E., Ketchum,K.A., Dodson,R.J., Gwinn,M., Hickey,E.K., Peterson,J.D., Richardson,D.L., Kerlavage,A.R., Graham,D.E., Kyrpides,N.C., Fleischmann,R.D., Quackenbush,J., Lee,N.H., Sutton,G.G., Gill,S., Kirkness,E.F., Dougherty,B.A., McKenney,K., Adams,M.D., Loftus,B., Venter,J.C. et al. (1997) Nature, 390, 364–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith D.R., Doucette-Stamm,L.A., Deloughery,C., Lee,H., Dubois,J., Aldredge,T., Bashirzadeh,R., Blakely,D., Cook,R., Gilbert,K., Harrison,D., Hoang,L., Keagle,P., Lumm,W., Pothier,B., Qiu,D., Spadafora,R., Vicaire,R., Wang,Y., Wierzbowski,J., Gibson,R., Jiwani,N., Caruso,A., Bush,D., Reeve,J.N. et al. (1997) J. Bacteriol., 179, 7135–7155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zwieb C. (1991) Nucleic Acids Res., 19, 2955–2960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chittenden K., Black,S. and Zwieb,C. (1994) J. Biol. Chem., 269, 20497–20502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schenk P.M., Baumann,S., Mattes,R. and Steinbiss,H.H. (1995) Biotechnology, 19, 196–200. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maniatis T., Fritsch,E. and Sambrook,J. (1982) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 39.Walker P., Black,S. and Zwieb,C. (1995) Biochemistry, 34, 11989–11997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lingelbach K., Zwieb,C., Webb,J.R., Marshallsay,C., Hoben,P.J., Walter,P. and Dobberstein,B. (1988) Nucleic Acids Res., 16, 9431–9442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wolffe A.P. (1988) EMBO J., 7, 1071–1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gilmore R., Collins,P., Johnson,J., Kellaris,K. and Raoiejko,P. (1991) Methods Cell Biol., 34, 223–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gowda K., Black,S., Moeller,I., Sakakibara,Y., Liu,M.-C. and Zwieb,C. (1998) Gene, 207, 197–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Görlich D., Kurzchalia,T., Wiedmann,M. and Rapoport,T. (1991) Methods Cell Biol., 34, 241–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Benson D.A., Boguski,M.S., Lipman,D.J., Ostell,J., Ouellette,B.F., Rapp,B.A. and Wheeler,D.L. (1999) Nucleic Acids Res., 27, 12–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stoesser G., Tuli,M.A., Lopez,R. and Sterk,P. (1999) Nucleic Acids Res., 27, 18–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Altschul S.F., Madden,T.L., Schaffer,A.A., Zhang,J., Zhang,Z., Miller,W. and Lipman,D.J. (1997) Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 3389–3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zwieb C., Gowda,K., Larsen,N. and Müller,F. (1997) In Leontis,N.B.S.J.,Jr (ed.), Molecular Modeling of Nucleic Acids. American Chemical Society, Washington, DC, Vol. 682, pp. 405–413.

- 49.Siegel V. and Walter,P. (1988) Cell, 52, 39–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kurzchalia T., Wiedman,M., Girshovich,A., Bochkareva,E., Bielka,H. and Rapoport,T. (1986) Nature, 320, 634–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lütcke H., High,S., Romisch,K., Ashford,A.J. and Dobberstein,B. (1992) EMBO J., 11, 1543–1551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zwieb C. (1985) Nucleic Acids Res., 13, 6105–6124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gowda K. and Zwieb,C. (1997) Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 2835–2840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jackson R. and Hunt,T. (1983) Methods Enzymol., 96, 50–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]