Abstract

Emerging evidence shows that palmitic acid (PA), a common fatty acid in the human diet, serves as a signaling molecule regulating the progression and development of many diseases at the molecular level. In this review, we focus on its regulatory roles in the development of five pathological conditions, namely, metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular diseases, cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and inflammation. We summarize the clinical and epidemiological studies; and also the mechanistic studies which have identified the molecular targets for PA in these pathological conditions. Activation or inactivation of these molecular targets by PA controls disease development. Therefore, identifying the specific targets and signaling pathways that are regulated by PA can give us a better understanding of how these diseases develop for the design of effective targeted therapeutics.

Keywords: Palmitic acid, Metabolic syndrome, Cardiovascular diseases, Cancer, Neurodegenerative diseases, Inflammation

Introduction

Palmitic acid (PA) is a 16-carbon long-chain saturated fatty acid with the molecular formula C16H32O2. It is the principle saturated fatty acid in palm oil [1, 2], accounting for 44–52% of its total fatty acid content [3]. PA is also a common saturated fatty acid in many common dietary fats, accounting for about 13% of the total fatty acid content in peanut oil, 65% in butter, 42% in lard, 53% in tallow, 15% in soybean, 13% in corn oil, and 17% in olive oil [4].

PA is the most common saturated fatty acid in the human body [5], accounting for ~ 65% of the saturated fatty acids in the body and 28–32% of the total fatty acids in serum [6, 7]. On average, a healthy 70-kg man is made up of 3.5 kg PA [5]. PA in our body is provided in the diet or synthesized endogenously from carbohydrates, amino acids, and other fatty acids. The plasma PA levels in healthy subjects have been reported, but most of the data are presented as the percentages of total fatty acid composition [8] and the total numbers of fatty acids measured in these different studies are different. Some other studies have measured the plasma PA concentration in healthy subjects, showing that it ranges from ~ 110–180 µmol/L (Table 1). The plasma PA levels do not show significant difference between healthy people and those who are obese or having chronic inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (Table 1). However, the plasma PA level is elevated in diabetic subjects (Table 1). Nevertheless, it seems that the plasma PA level can have a wide range in the same cohort of healthy subjects. In two studies with 826 and 26 healthy subjects, the reported average plasma PA concentrations were 300 and 4100 µmol/L, respectively, which results in a big standard derivation (Table 1). Excess lipids or fatty acids can accumulate in non-adipose tissues and are toxic to these tissues, because, when long-chain non-esterified fatty acids such as palmitic acid are metabolized in peroxisomes, the hydrogen peroxide formed by acyl-coenzyme A oxidases harms cells lacking catalase [9].

Table 1.

Plasma palmitic acid (PA) levels

| Study cohort (number of subjects) | Plasma palmitic acid level (µmol/L) | References |

|---|---|---|

| Normal subjects (n = 8) | 111 ± 12 | [10] |

| Young healthy adults (n = 826) | 1631.1 ± 459.3 | [11] |

| Normal subjects (n = 26) | 1905 ± 537 | [12] |

| Normal subjects (n = 12) | 183.3 ± 96.47 | [13] |

| Diabetic patients | > 300 | [14] |

| Rheumatoid arthritis patients (n = 9) | 149 ± 14 | [15] |

| Upper body obese patients (n = 10) | 128 ± 8 | [10] |

| Lower body obese patients (n = 9) | 106 ± 14 | [10] |

Since many studies suggest that PA is involved in the development of diseases, this review will summarize the clinical, epidemiological, and, most importantly, the mechanistic studies at the molecular level. Overall, results of these studies indicate that PA not only serves as an energy source but also is a signaling molecule involved in the development and progression of many diseases.

PA post-translationally modifies proteins

PA can post-translationally modify proteins in a process called palmitoylation in which PA is covalently linked to the proteins through a thioester bond. This covalent linkage is reversible when the thioester bond is cleaved by thio-esterase. Therefore, palmitoylation serves as a switch that regulates the protein’s function. The types of proteins that undergo palmitoylation are quite diverse including mitochondrial proteins, and intrinsic and peripherally associated membrane proteins. For example, palmitoylation increases the hydrophobicity of membrane protein and directs the protein to specific microdomains within the plasma membrane [16]. Palmitoylation of soluble proteins allows them to interact with membranes and target-specific vesicles. Palmitoylation also facilitates subcellular trafficking of proteins between membrane organelles and within microdomains of individual membrane compartments, and, hence, modulates protein–protein interaction. Many soluble proteins do not remain where palmitoylation takes place, but are delivered to other cellular compartments via vesicular transport [17].

Palmitoylation acts as a switch to “turn on” and “turn off” many physiological processes by maintaining or regulating the functions of these proteins in the healthy physiological state. For example, palmitoylation affects the G protein-coupled receptor functions which are wide ranging and implicated in many agonist-induced physiological processes [18]. Palmitoylation also regulates the functions of glutamate receptor [16] and vasopressin receptor-2, facilitating the interaction of beta-arrestin with the receptor to initiate beta-arrestin-dependent downstream events such as endocytosis [18].

However, dysregulation of the protein activity by palmitoylation leads to disease development [19]. For example, Ras proteins are well-known drivers of many cancers, and palmitoylation may disrupt the membrane interaction of specific Ras isoforms and, hence, regulate Ras tumorigenesis [20]. In prostate cancer, palmitoylation is important in trafficking of protease-activated receptor-2 [21]. Palmitoylation of metastasis suppressor protein KAI1/CD82 affects motility-related subcellular events such as lamellipodia formation and actin cytoskeleton organization [22]. Many reviews have discussed the roles of palmitoylation in the development of cancers [23, 24], neuronal diseases [25–27], and metabolic dysregulation [28, 29].

PA serves as an intracellular signaling molecule in disease development

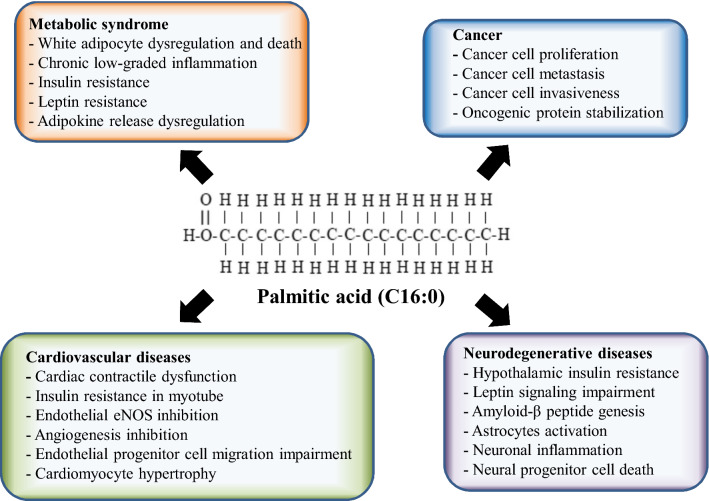

This review highlights the roles of PA in the development of four of the most prevalent life-threatening diseases, including metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular diseases, cancers, and neurodegenerative diseases (Fig. 1), and in inflammation, an important condition increasingly suspected to underlie or be associated with all of these diseases.

Fig. 1.

Palmitic acid is involved in disease development

Metabolic syndrome

Metabolic syndrome is defined as a cluster of at least three out of five clinical risk factors including abdominal (visceral) obesity, elevated serum triglycerides, low serum high-density lipoprotein (HDL), insulin resistance, and hypertension. Abdominal or visceral obesity and insulin resistance are considered to be the predominant risk factors for metabolic syndrome [30, 31].

Clinical and epidemiological studies show that an elevated level of plasma PA, but not other saturated fatty acids, is associated with metabolic syndrome [6, 32], although findings are controversial [33, 34]. The plasma PA level in diabetic patients is at least threefold that in normal subjects (Table 1). In vivo and in vitro mechanistic studies demonstrate that high level of plasma PA results in increased cellular uptake of PA [35]. The excess PA in the cells enters non-oxidative metabolic pathways; more specifically, it increases diacylglycerol that activates protein kinase C and, subsequently, increases the serine phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1) [35]. The serine phosphorylation then reduces IRS-1 activation, inhibits phosphatidyl-inositol-3 kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (AKT) signaling pathway, and promotes both PTEN activity and transcription through p38 and its downstream transcription factor ATF-2 [35]. All these PA-mediated effects inhibit insulin signaling and lead to the development of insulin resistance. Furthermore, in pancreatic islets, PA inhibits glucose-induced insulin secretion by impairing exocytosis evoked by action potential-like depolarization [36]. PA also increases the production of interleukin-1β that not only promotes the development of insulin resistance in tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-dependent and TNF-independent pathways [37], but also activates autophagy by inducing endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress [38]. Nevertheless, PA at physiological concentration preserves pancreatic β-cell machinery and function by increasing the Tyr phosphorylation of IRS-2 and activity of phosphoinositide 3-kinases (PI3K), while reducing the phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated protein kinases 1 and 2 (ERK1/2) (Thr202/Tyr204), and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 STAT3 (Ser 727) in the pancreatic islets [39].

Interestingly, plasma PA levels in obese patients are not significantly different from those of non-obese subjects (Table 1). Instead, obese patients have excess accumulation of fatty acids, including PA, in the adipocytes, because obesity is characterized by an excess accumulation of white adipose tissues that are the primary organs storing triglycerides. In vitro and in vivo mechanistic studies show that excess PA accumulation in white adipocytes leads to chronic low-grade inflammation [40] and dysregulation [41] of the adipocytes, such as reduced adiponectin secretion [42, 43]. These hypertrophied adipocytes will also secrete pro-inflammatory agents that promote systemic inflammation [44]. Furthermore, the PA-filled adipocytes activate macrophages but not the adipocytes enriched in unsaturated fatty acids [40]. Studies also suggest that PA activates protein kinase C, nuclear factor-κB (NFκB) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways in the adipocytes and, hence, leads to production of cytokines including TNF and interleukin-10 (IL-10) [45, 46]. An ex vivo study also shows that even a short-term post-prandial increase in PA can significantly increase NFκB release and activate the Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-mediated inflammatory response in adipocytes [47]. Besides, dying adipocytes elicit inflammation in which PA induces cell death by activating oxidative pathways [40]. In addition, PA induces ER stress by increasing CCAAT/enhancer-binding (C/EBP) homologous protein and glucose regulatory protein 78 (GRP78/BiP). It also increases splicing of X-box-binding protein-1 (sXBP-1), resulting in enhanced phosphorylation of eIF2alpha, c-jun-NH2-terminal kinase (JNK), and ERK [41, 48–50]. In addition, PA has multiple impacts on cellular stress that induces apoptosis in pre-adipocytes [48]. PA increases ER stress in pre-adipocytes as evidenced by the increased levels of CCAAT-enhancer-binding protein homologous protein (CHOP), GRP78/BiP, sXBP-1, and also the phosphorylation of eIF2-α, JNK, and ERK1/2 [48]. It is worth noting that clinical studies have demonstrated that the adipocyte cell death is 300% higher in obese than in lean individuals [51, 52]. These mechanistic studies on the pathological effects of PA in adipocytes suggest novel therapeutic strategies to combat inflammation in obese individuals, thereby helping to reverse metabolic syndrome.

Leptin is an important hormone released by adipocytes. Leptin resistance is associated with plasma PA level, and it may lead to metabolic syndrome. Specifically, obesity is closely associated with leptin resistance, although it is still debatable whether leptin resistance is the cause or the outcome of diet-induced obesity [53]. One school of thought maintains that obesity causes leptin resistance [54]; however, animal study shows that pre-existing reduction in leptin sensitivity determines the susceptibility to developing diet-induced obesity [55]. Many studies suggest that PA induces leptin resistance. Diets high in saturated fats such as PA impair insulin-induced and leptin-induced anorexia and hypothalamic insulin signaling [56]. Increased PA in the central nervous system with intragastric administration of PA-enriched emulsion induces translocation of PKC-θ to cell membranes in the hypothalamus, which is associated with impaired hypothalamic insulin and leptin signaling [56]. Exposure of hypothalamic neuronal cells in culture to PA (100 µM) attenuates insulin-induced AKT phosphorylation and inhibits insulin signaling [56].

In many animal studies, intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) infusions of PA are used to study the effects of PA on the brain. For example, a study found that i.c.v. infusions of PA, but not oleic acid or vehicle alone, attenuate insulin-induced suppression of hepatic glucose production [56]. Another study found that i.c.v. administration of PA leads to central leptin resistance, evidenced by the inhibition of central leptin’s suppression of food intake [37]. The i.c.v. PA administration also blunts the effect of leptin-induced reduction in mRNA expression of glucose 6-phosphatase (G6Pase), phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK), glucose transporter 2 (GLUT2), fatty acid synthase (FAS), and stearoyl-coenzyme A desaturase 1 (SCD1) in liver [37]. Although intragastric administration may be a preferable and physiological approach to examining the in vivo effects of PA in the brain, these in vivo findings are all supported by in vitro data, suggesting the pathological effect of PA in the brain.

Cardiovascular diseases (CVD)

CVD, metabolic syndrome, and diabetes are closely linked [31, 57–60]. The plasma PA levels in diabetic subjects are higher than those of healthy subjects (Table 1), and it is known that elevated plasma PA is associated with increased incidence of type 2 diabetes [61]. In a cross-sectional study, it was found that elevated plasma PA and myristic acid are associated with CVD mortality [62]. The notion of lowering dietary saturated fatty acids to reduce CVD risk is strongly recommended in the 2013 American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology Guideline on Lifestyle Management to Reduce Cardiovascular Risk, and also the National Lipid Association Expert Panel [63]. Indeed, “lipid theory” states that excess saturated fatty acid consumption will lead to hypercholesterolemia that causes pre-disposition to a higher CVD risk [3].

The mechanistic investigations of the effects of PA on CVD used diabetic plasma PA concentrations of 300 µM or above in their experiments. In cardiomyocytes, PA at the diabetic concentration induces loss of caveolin-3, resulting in cardiac contractile dysfunction by interrupting Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release in the cardiomyocytes [64]. In endothelial cells, PA treatment activates a stimulator of the STING-IRF3 (interferon genes–interferon regulatory factor-3) pathway and induces endothelial inflammation [65]. Furthermore, it inhibits the insulin signaling pathway and eNOS activation by activating phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) activity and its transcription through p38 and its downstream cyclic AMP-dependent transcription factor (ATF-2) [66]. Besides, PA also inhibits angiogenesis by inhibiting endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and tube formation mediated by the increase in mammalian Ste20-like kinase 1 (MST1) and Hippo-Yes-associated protein (YAP) phosphorylation [67]. PA is a natural ligand of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) [68]. Although the net balance of favorable and unfavorable effects of PPARγ activation on cardiovascular outcomes remains uncertain [64, 69, 70], it has been established that diabetic PA concentration impairs endothelial progenitor cell migration and proliferation through a PPARγ-mediated STAT5 transcription inhibition [68]. In myotubes, PA causes mitochondrial membrane potential loss and, hence, cell death [71]. Furthermore, PA also reduces insulin-stimulated glucose uptake by 30%, and the phosphorylation of PI3K and AKT by 40% [72], thereby promoting the degradation of κBα inhibitors and the nuclear translocation of NFκB that results in insulin resistance in myotubes [72].

These mechanistic studies suggest that elevated plasma PA has pathological roles in the CVD development. At the same time, plasma PA at physiological levels (near 150 µM) has a protective role in the cardiovascular system. It increases the activity of 5′ AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) [73] contributing to cardiomyocyte health and survival [74]; it increases glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) expression [73] which is protective against myocardial infarction [75]; it increases phosphorylation of PCKζ [73] which interacts with STAT3; and it promotes STAT3-mediated cardiomyocyte hypertrophy [76].

Cancer

As reported by the World Health Organization, cancer is the second leading cause of death globally; nearly 1 in 6 deaths is due to cancer. Around one-third of cancer deaths are due to five leading behavioral risks and dietary risks. They are: high body mass index, low intake of fruits and vegetables, lack of exercise, intake of tobacco, and alcohol consumption. Indeed, many studies have suggested that high dietary fat intake is directly associated with the incidence and development of many cancers [77]. PA is the most common saturated fatty acid in the human diet [1]; hence, the role of PA in cancer development deserves attention.

PA for cancer cells can come from endogenous synthesis and exogenous uptake. Under normal physiological condition, the human body can synthesize PA from acetyl-CoA via a lipogenesis pathway catalyzed by the enzymes acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) and fatty acid synthase (FAS) in the cytoplasm. ACC catalyzes the first committed step in fatty acid synthesis which is the carboxylation of acetyl-CoA to malonyl-CoA. ACC activity can be activated by citrate and inhibited by long-chain acyl-CoA molecules or phosphorylation of the enzyme. ACC activity can also be regulated by hormones such as glucagon, epinephrine and insulin. FAS plays a central role in de novo lipogenesis using acetyl-CoA as a primer, malonyl-CoA as a two-carbon donor, and NADPH as reducing equivalent in a series of condensation reactions to synthesize PA. Under normal conditions, FAS converts excess carbohydrate into PA and, subsequently, other fatty acids, which provide energy through β-oxidation when needed. FAS level is under dietary influence in that its transcription can be regulated by nutrient-sensing transcription factors [78, 79]. Up to 20-fold difference of the FAS level is observed when comparing the livers of animals that have been starved with those that have been fed with carbohydrate after starving.

Cancer cells have altered metabolism that includes fundamental changes in glucose, lipid, and amino acid metabolism, all of which affect cellular PA levels. In cancer cells, fatty acids come from the diet or are synthesized from citrate which is exported out of mitochondria to provide acetyl-CoA for lipogenesis [80]. In the lipogenic pathway, cancer cells have an enhanced level of FAS [81, 82] even under a sufficient dietary lipid supply [83]. PA is the immediate end-product of the enzyme FAS. Many studies have reported that inhibition of FAS induces apoptosis in cancer cells [84, 85], most likely by reducing PA availability, because addition of PA restores cancer cell viability [83]. Besides, inhibition of the enzyme FAS also disrupts lipid raft architecture, inhibits PI3K-AKT-mTOR and β-catenin signal transduction, and reduces the expression of oncogenic effectors such as c-Myc [85]. In aggressive cancers, if endogenous lipogenesis is suppressed under conditions such as hypoxia, the cancer cells will switch to the uptake of extracellular fatty acids by increasing the expression of fatty acid-binding proteins 3 (FABP3), FABP7, and adipophilin [86]. Alternatively, liposarcoma, breast and prostate cancer cells will induce expression of lipoprotein lipase that processes chylomicrons, triglycerides, and phospholipids, and facilitates the uptake of exogenous fatty acids via the fatty acid translocase CD36 [87].

Other than from diet and endogenous synthesis, cancer cells can uptake fatty acids from adipocytes in the tumor microenvironment. Adipocytes have been reported to interact directly with cancer cells at the invasive front of the tumor [88], where adipocytes undergo lipolysis to release fatty acids that are transferred to the cancer cells. Indeed, increase in fatty acid release from adipocytes has been linked to the invasiveness of pancreatic, prostate, and breast cancers [89, 90]. In a study with co-cultured melanoma cells and adipocytes, the triglyceride level and PA level in the co-cultured melanoma cells were elevated [77]. In another study with breast cancer cells, the triglyceride level in co-cultured breast cancer cells was increased fivefold, which is in accordance with the lipid droplet accumulation [91]. Interestingly, in these co-cultured cancer cells, no changes were observed in unsaturated fatty acids, diglyceride, cholesterol, and cholesteryl-ester levels, and monoglycerides were undetectable [91].

In general, fatty acids including PA serve as energy sources for cancer growth through β-oxidation [92]; or they are used for membrane synthesis and incorporation into structural and oncogenic signaling lipids such as glycerol-phospholipids, sphingolipids, and ether lipids in the cancer cells [93, 94].

However, there is growing evidence that differentiates PA from other saturated fatty acids in promoting cancer growth, because PA has specific tumorigenic properties. It was recently reported that PA specifically boosts the metastatic potential of CD36+ metastasis-initiating cells in a CD36-dependent manner [95]. PA increases the metastatic potential of cancer cells [95]. Other fatty acids such as oleate and linoleic acid [96] only contribute to the cellular lipid pool and increase fatty acid oxidation [97].

We speculate that PA serves as a signaling molecule in cancer cells to promote cancer growth and increase metastatic potential. In melanoma, PA increases the phosphorylation of Akt at Ser-473 and Thr-450 and, hence, increases melanoma cell proliferation. Inhibition of Akt with LY294002 or knockdown endogenous Akt significantly reduces PA-enhanced proliferation in melanoma [83], suggesting that PA targets Akt and, hence, increases melanoma cell proliferation. In pancreatic cancer cells, PA activates the TLR4/ROS/NFκB/MMP9 signaling pathway and, hence, increases cancer invasiveness [98]. In prostate cancer, PA increases STAT3 phosphorylation that leads to increased cancer growth both in vitro and in vivo (unpublished data). Interestingly, in hepatocellular carcinoma, PA attenuates mTOR and STAT3 expressions and reduces cancer cell proliferation, impairs cell invasiveness, and suppresses tumor growth in xenograft mouse models. PA also decreases cell membrane fluidity and limits glucose metabolism in hepatocellular carcinoma cells [99]. In breast cancer, PA induces a functionally distinct transcriptional program which reduces HER2 and HER3 levels [100]. PA also activates an ER stress response network via X-box-binding protein-1 (XBP-1) and activating transcription factor-6 (ATF6) in breast cancer cells; it also induces G2-phase cell cycle delay and C-EBP homologous protein CHOP-dependent apoptosis [100]. The effects of PA on carcinogenesis vary between cancer types, which may be because different cancers have different metabolic reprogramming; this possibility deserves further investigation.

Other than directly activating molecular targets, PA also stabilizes oncogenic proteins in cancer cells. PA is involved in the palmitoylation of Wnt-1 [101]. The PA moiety on Wnt is critical for proper secretion from cells and the transduction of the activation signal to β-catenin following its binding to the receptors [100]. Study shows that PA is involved in the cytoplasmic stabilization of β-catenin in prostate cancer, leading to membranous and cytoplasmic β-catenin protein accumulation and activation [101].

PA was the first lipid to be detected in the COOH-terminal of Ras [102, 103]. The H-, N-, and K4A-Ras proteins have palmitate attached to cysteine residues just at the NH2-terminal of the CXXX motif and to the prenyl group [104, 105]. H-Ras protein has three COOH-terminal lipid—palmitates at cysteines 181 and 184, and a farnesyl at cysteine 186. Attachment of palmate to Ras enhances Ras membrane association and activation. For H-Ras, membrane binding of mutant H-Ras protein that lacks palmate attachment is only 5–10% of the fully modified H-Ras protein, which leads to reduced H-Ras activity [104, 105].

Neurodegenerative diseases

Neurodegenerative diseases are, so far, incurable. Progressive degeneration and nerve cell death result in debilitating conditions which are involved in the debilitating conditions of movement (ataxias) and/or mental functioning (dementia). Among all the neurodegenerative diseases, Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most prevalent, representing 60–70% of dementia cases.

Epidemiological studies have found that diets rich in saturated fatty acids and high plasma PA levels are inversely correlated with strong cognitive function [106–108]. PA, either from diet or from de novo lipogenesis in the liver, can cross the blood–brain barrier and thereby increase the fatty acid pool in the brain [109].

Studies show that PA induces ER stress in neuroblastoma cells which involves the activation of CHOP and the associated increase of the β-site AβPP cleaving enzyme-1 (BACE-1) expression and activity [106]. These conditions are followed by enhanced amyloidogenic processing of amyloid-β protein precursor that culminates in a substantial increase in Aβ genesis [106] that leads to AD pathogenesis. The increase of BACE-1 induced by PA can also be mediated by STAT3 activity in the neurons [110] and by accumulation of beta-amyloid precursor protein [111]. PA has also been reported to induce an AD-like pathological pattern in primary cortical neurons by elevating oxidative stress and altering free fatty acid metabolism in the astrocytes [112]; the activated astrocytes lead to neuronal inflammation and demyelination. PA-induced astrocyte cell death is unrelated to ER stress and perturbation in cytosolic Ca2+ signaling, but it is a result of reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and subsequent collapse of mitochondrial membrane potential [113]. PA also causes neural progenitor cell death by elevating the level of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [114]. Interestingly, oleic acid and lauric acid fail to induce cell death in neurons and astrocytes [115].

Inflammation

Inflammation interrelates with many diseases. For example, metabolic syndrome with its associated inflammation favors cancer development [116]. Complications in CVD and metabolic syndromes are related to common pro-inflammatory cytokines [117]. Inflammation serves as the linkage between these diseases, and interestingly, PA induces inflammation. It does so in various cell types with different mechanisms of action.

Mechanistic studies show that PA concentrations in the range of 50–500 µM induce activation of NLRP3-PYCARD-inflammasomes which releases caspase 1, IL-1β, and IL-18 in macrophages. The activation of inflammasomes involves the AMPK and unc-51-like autophagy activating kinase (ULK1) signaling cascade and ROS production [118]. However, unsaturated fatty acids fail to activate NLRP3-PYCARD-inflammasomes [118]. PA also increases expressions of inflammatory genes such as TNF and IL-6 [119, 120] in the macrophages via TLR4-dependent and NFκB-dependent mechanisms [121–124]. In other cell types such as astrocytes, PA—but not unsaturated fatty acids—triggers release of TNFα and IL-6 from astrocytes in a TLR-4-dependent manner, suggesting that high levels of circulating PA cause reactive gliosis and brain inflammation, and could potentially participate in the reported adverse neurologic consequences of obesity and metabolic syndrome [125]. In the cardiovascular system, PA reduces endothelial nitric synthase (eNOS) activity and induces inflammation in endothelial cells and causes endothelial dysfunction [126]. PA also increases epidermal growth factor receptor activation mediated by TLR4 in cardiomyocytes and results in the pathogenesis of obesity-induced cardiac inflammatory injuries [127]. Although PA activates TLR4 in many cell types, it fails to activate TLR4 in adipocytes to elicit inflammation [128]. Recently, the mechanism by which PA activates TLR4 has been reported [129]. Studies of cell surface binding, cell-free protein–protein interactions, and molecular docking simulations indicate that PA directly binds to TLR4 accessory protein MD2, and, hence, activates TLR4 and downstream inflammatory responses [129]. Studies have also demonstrated that impaired TLR4 signaling can protect against PA- and high-fat diet-induced inflammation [119, 129].

Conclusion

Palmitic acid (PA) is the most common saturated fatty acid in the human body as well as in the diet. PA serves as energy source and building block for lipid metabolism. It is also unique among saturated acids for its pathogenic roles in metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and inflammation. Evidence further suggests that PA functions in these diseases by affecting molecular signaling. Table 2 summarizes the signaling molecules and signaling pathways that are regulated by PA.

Table 2.

Molecular targets of palmitic acid

| Molecular target and signaling pathway | Regulation | Tissue/organ | Pathology | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) | Activation | Adipocytes | Inflammation | [47] |

| Activation | Macrophages | Inflammation | [124] | |

| Activation | Astrocytes | Inflammation | [126] | |

| Activation | Cardiomyocytes | Inflammation | [128] | |

| Activation | Pancreatic cancer | Increases invasiveness | [98] | |

| Nuclear factor-κB (NFκB) | Activation | Adipocytes | Cytokine production | [45, 47] |

| Activation | Pancreatic cancer | Increases invasiveness | [105] | |

| Activation | Myotubes | Insulin resistance | [72] | |

| Endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) | Inhibition | Endothelial cells | Insulin resistance | [66] |

| Downregulation | Endothelial cells | Endothelial dysfunction | [127] | |

| Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) | Downregulation | Adipocytes | Reduces adiponectin synthesis | [49] |

| Downregulation | Macrophages | Inflammation | [50] | |

| Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) | Inhibition (Ser727) | Pancreatic islet | Insulin resistance | [39] |

| Downregulation | Hepatocellular carcinoma | Reduces cell proliferation, impairs cell invasiveness | [83] | |

| Activation | Prostate cancer | Increases cell proliferation and invasiveness | Unpublished data | |

| Activation | Neurons | Generation of the amyloid peptide in Alzheimer’s disease | [114] | |

| Signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 (STAT5) | Inhibition | Endothelial progenitor cells | Endothelial progenitor cell dysfunction | [68] |

| Insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS-1) | Activation (Ser307) | Adipocytes | Insulin resistance | [42] |

| Insulin receptor substrate-2 (IRS-2) | Activation | Pancreatic islet | Insulin resistance | [39] |

| Insulin receptor | Inhibition | Pancreatic islet | Insulin resistance | [75] |

| Phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN) | Upregulation | Endothelial cells | Insulin resistance | [66] |

| Phosphatidyl-inositol 3 kinase (PI3K) | Activation | Pancreatic islet | Insulin resistance | [39] |

| Inhibition | Myotubes | Insulin resistance | [72] | |

| C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP) | Upregulation | Pre-adipocytes | ER stress | [48] |

| Glucose regulatory protein 78 (GRP78) | Upregulation | Pre-adipocytes | ER stress | [48] |

| c-jun-NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) | Upregulation | Pre-adipocytes | ER stress | [48] |

| Protein kinase B (PKB) | Inhibition | Myotubes | Insulin resistance | [72] |

| Akt | Activation (Ser472) | Adipocytes | Insulin resistance | [50] |

| Activation (Ser472 & Thr450) | Melanoma | Increase cell proliferation | [77] | |

| Protein kinase (PKC-θ) | Activation | Hypothalamus | Impair hypothalamic insulin and leptin signaling | [113] |

| Extracellular signal–regulated kinases1/2 (ERK1/2) | Inhibition (phosphorylation site Thr202/Tyr204) | Pancreatic islet | Insulin resistance | [39] |

| Mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) | Activation | Adipocytes | Production of cytokines | [45] |

| Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) | Downregulation | Hepatocellular carcinoma | Reduces cell proliferation, impairs cell invasiveness | [99] |

| Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARγ) | Activation | Endothelial progenitor cells | Endothelial progenitor cell dysfunction | [69] |

| X-Box-Binding Protein 1 (XBP-1) | Upregulation | Breast cancer | ER stress | [100] |

| Activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6) | Downregulation | Breast cancer | ER stress | [100] |

| NLRP3 | Activation | Macrophages | Inflammasome production | [123] |

| Eukaryotic Initiation Factor 2 (eIF2alpha) | Upregulation | Pre-adipocytes | ER stress | [48] |

| C-EBP homologous protein (CHOP) | Activation | Neuroblastoma cells | ER stress | [112] |

| Cyclic guanosine monophosphate (GMP)–adenosine monophosphate (AMP) synthase (cGAS) | Activation | Endothelial cells | Mitochondrial damage and activation of stimulator of interferon genes (STING) | [67, 71] |

| Leptin signaling | Inhibition | Mediobasal hypothalamus and hypothalamic nuclei | Leptin resistance | [37] |

| Autophagic vacuole | Upregulation | Pancreatic islet | Autophagy | [38] |

Up to the present, the mechanisms underlying how PA activates the various signaling molecules are not fully understood. Identifying the specific targets and signaling pathways that are regulated by PA will not only give us a better understanding of disease development, but will also facilitate the development of effective targeted therapeutics.

Acknowledgements

We thank for Dr Martha for her professional editing of the manuscript.

Author contributions

Conception and design: HYK and ZXB. Acquisition of information: SF, HYK, XJH, RHG, CHH, MTC, and HLXW. Writing and review of the manuscript: SF, HYK, and ZXB. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partially supported by the Research Grant Council of HKSAR HKBU-22103017-ECS, Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province #2018A0303130122, and the Hong Kong Baptist University Grant FRG2/16-17/010 and FRG2/17-18/002.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Zhaoxiang Bian, Phone: (+852) 34112016, Email: bzxiang@hkbu.edu.hk.

Hiu Yee Kwan, Phone: (+852) 34112905, Email: hykwan@hkbu.edu.hk.

References

- 1.Gunstone FD, Harwood JL, Dijkstra AJ. The lipid handbook with CD-ROM. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bier DM. Saturated fats and cardiovascular disease: interpretations not as simple as they once were. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2016;56:1943–1946. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2014.998332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mancini A, et al. Biological and nutritional properties of palm oil and palmitic acid: effects on health. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) 2015;20:17339–17361. doi: 10.3390/molecules200917339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hermann JR (2017) Diet and heart disease Oklahoma cooperative extension service T3160. http://factsheets.okstate.edu/documents/t-3160-diet-and-heart-disease. Accessed 18 June 2018

- 5.Carta G, et al. Palmitic acid: physiological role, metabolism and nutritional implications. Front Physiol. 2017;8:902. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.00902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu Y, et al. Serum levels of polyunsaturated fatty acids are low in Chinese men with metabolic syndrome, whereas serum levels of saturated fatty acids, zinc, and magnesium are high. Nutr Res (New York, N.Y.) 2012;32:71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klein S, Wolfe RR. Carbohydrate restriction regulates the adaptive response to fasting. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:E631–E636. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1992.262.5.E631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abdelmagid SA, et al. Comprehensive profiling of plasma fatty acid concentrations in young healthy Canadian adults. PLoS One. 2015;10(2):e0116195. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gehrmann W, et al. Role of metabolically generated reactive oxygen species for lipotoxicity in pancreatic beta-cells. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2010;12(Suppl 2):149–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2010.01265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jensen MD, et al. Influence of body fat distribution on free fatty acid metabolism in obesity. J Clin Invest. 1989;83:1168–1173. doi: 10.1172/JCI113997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abdelmagid SA, et al. Comprehensive profiling of plasma fatty acid concentration in young healthy Canadian adults. PLoS One. 2015;10(2):e0116195. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El-Ansary Afaf K, et al. Plasma fatty acids as diagnostic markers in autistic patients from Saudi Arabia. Lipids Health Dis. 2011;10:62. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-10-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cunnane SC, et al. Plasma and brain fatty acid profiles in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;29(3):691–697. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-110629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trombetta A, et al. Increase of palmitic acid concentration impairs endothelial progenitor cells and bone marrow-derived progenitor cell bioavailability. Diabetes. 2013;62:1245. doi: 10.2337/db12-0646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fraser DA, et al. Changes in plasma free fatty acid concentrations in rheumatoid arthritis patients during fasting and their effects upon T-lymphocyte proliferation. Rheumatology. 1999;38:948–952. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/38.10.948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thomas GM, Huganir RL. Palmitoylation-dependent regulation of glutamate receptors and their PDZ domain-containing partners. Biochem Soc Trans. 2013;41:72–78. doi: 10.1042/BST20120223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chamberlain LH, et al. Palmitoylation and the trafficking of peripheral membrane proteins. Biochem Soc Trans. 2013;41:62–66. doi: 10.1042/BST20120243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Charest PG, Bouvier M. Palmitoylation of the V2 vasopressin receptor carboxyl tail enhances beta-arrestin recruitment leading to efficient receptor endocytosis and ERK1/2 activation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:41541–41551. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306589200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen B, et al. protein lipidation in cell signaling and diseases: function, regulation, and therapeutic opportunities. Cell Chem Biol. 2018;25(7):817–831. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2018.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin DTS, Davis NG, Conibear E. Targeting the Ras palmitoylation/depalmitoylation cycle in cancer. Biochem Soc Trans. 2017;45:913–921. doi: 10.1042/BST20160303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adams MN, et al. The role of palmitoylation in signalling, cellular trafficking and plasma membrane localization of protease-activated receptor-2. PLoS One. 2011;6:e28018. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou B, et al. The palmitoylation of metastasis suppressor KAI1/CD82 is important for its motility- and invasiveness-inhibitory activity. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7455–7463. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Resh MG. Palmitoylation of proteins in cancer. Biochem Soc Trans. 2017;45:409–416. doi: 10.1042/BST20160233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderson AM, Ragan MA. Palmitoylation: a protein S-acylation with implications for breast cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2016;2:16028. doi: 10.1038/npjbcancer.2016.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sambataro F, Pennuto M. Post-translational modifications and protein quality control in motor neuron and polyglutamine diseases. Front Mol Neurosci. 2017;10:82. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2017.00082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holland SM, Thomas GM. Roles of palmitoylation in axon growth, degeneration and regeneration. J Neurosci Res. 2017;95:1528–1539. doi: 10.1002/jnr.24003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cho E, Park M. Palmitoylation in Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative diseases. Pharmacol Res. 2016;111:133–151. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mohammed AM, Chen F, Kowluru A. The two faces of protein palmitoylation in islet beta-cell function: potential implications in the pathophysiology of islet metabolic dysregulation and diabetes. Recent Pat Endocr Metab Immune Drug Discov. 2013;7:203–212. doi: 10.2174/18722148113079990008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao L, et al. CD36 palmitoylation disrupts free fatty acid metabolism and promotes tissue inflammation in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Hepatol. 2018;693:705–717. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paley CA, Johnson MI. Abdominal obesity and metabolic syndrome: exercise as medicine? BMC Sports Sci Med Rehab. 2018;10:7. doi: 10.1186/s13102-018-0097-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cooper-DeHoff RM, Pepine CJ. Metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease: challenges and opportunities. Clin Cardiol. 2007;30:593–597. doi: 10.1002/clc.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kabagambe EK, et al. Erythrocyte fatty acid composition and the metabolic syndrome: a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute GOLDN study. Clin Chem. 2008;54:154–162. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.095059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cook SL, et al. Palmitic acid effect on lipoprotein profiles and endogenous cholesterol synthesis or clearance in humans. Asia Pacific J Clin Nutr. 1997;6:6–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kien CL, Bunn JY, Ugrasbul F. Increasing dietary palmitic acid decreases fat oxidation and daily energy expenditure. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:320–326. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.2.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Palomer X, et al. Palmitic and oleic acid: the yin and yang of fatty acids in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Trends Endo Metab. 2018;29(3):178. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2017.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoppa MB, et al. Chronic palmitate exposure inhibits insulin secretion by dissociation of Ca2+ channels from secretory granules. Cell Metab. 2009;10:455–465. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheng L, et al. Palmitic acid induces central leptin resistance and impairs hepatic glucose and lipid metabolism in male mice. J Biochem Nutr. 2015;26:541–548. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2014.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martino L, et al. Palmitate activates autophagy in INS-1E beta-cells and in isolated rat and human pancreatic islets. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36188. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Graciano MF, et al. Palmitate activates insulin signaling pathway in pancreatic rat islets. Pancreas. 2009;38:578–584. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31819e65d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kennedy A, et al. Saturated fatty acid-mediated inflammation and insulin resistance in adipose tissue: mechanisms of action and implications. J Nutr. 2009;139:1–4. doi: 10.3945/jn.108.098269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takahashi K, et al. JNK- and IkappaB-dependent pathways regulate MCP-1 but not adiponectin release from artificially hypertrophied 3T3-L1 adipocytes preloaded with palmitate in vitro. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;294:E898–E909. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00131.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xi L, et al. Crocetin attenuates palmitate-induced insulin insensitivity and disordered tumor necrosis factor-alpha and adiponectin expression in rat adipocytes. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;151:610–617. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim JY, et al. Obesity-associated improvements in metabolic profile through expansion of adipose tissue. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2621–2637. doi: 10.1172/JCI31021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bays HE, et al. Pathogenic potential of adipose tissue and metabolic consequences of adipocyte hypertrophy and increased visceral adiposity. Expert Rev Cardio Ther. 2008;6:343–368. doi: 10.1586/14779072.6.3.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ajuwon KM, Spurlock ME. Palmitate activates the NF-kappaB transcription factor and induces IL-6 and TNFalpha expression in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J Nutr. 2005;135:1841–1846. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.8.1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bradley RL, Fisher FF, Maratos-Flier E. Dietary fatty acids differentially regulate production of TNF-alpha and IL-10 by murine 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.) 2008;16:938–944. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Youssef-Elabd EM, et al. Acute and chronic saturated fatty acid treatment as a key instigator of the TLR-mediated inflammatory response in human adipose tissue, in vitro. J Nutr Biochem. 2012;23:39–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guo W, et al. Palmitate modulates intracellular signaling, induces endoplasmic reticulum stress, and causes apoptosis in mouse 3T3-L1 and rat primary preadipocytes. Am J Physiol Endo Metab. 2007;293:E576–E586. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00523.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jeon MJ, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction and activation of iNOS are responsible for the palmitate-induced decrease in adiponectin synthesis in 3T3L1 adipocytes. Exp Mol Med. 2012;44:562–570. doi: 10.3858/emm.2012.44.9.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McCall KD, et al. Phenylmethimazole blocks palmitate-mediated induction of inflammatory cytokine pathways in 3T3L1 adipocytes and RAW 264.7 macrophages. J Endocrinol. 2010;207:343–353. doi: 10.1677/JOE-09-0370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Strissel KJ, et al. Adipocyte death, adipose tissue remodeling, and obesity complications. Diabetes. 2007;56:2910–2918. doi: 10.2337/db07-0767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cinti S, et al. Adipocyte death defines macrophage localization and function in adipose tissue of obese mice and humans. J Lipid Res. 2005;46:2347–2355. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500294-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Myers MG, et al. Obesity and leptin resistance: distinguishing cause from effect. Trends Endocrinol Metabol. 2010;21:643–651. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Crujeiras AB, et al. Leptin resistance in obesity: an epigenetic landscape. Life Sci. 2015;140:57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.de Git KCG, et al. Is leptin resistance the cause or the consequence of diet-induced obesity? Int J Obesit. 2018;42(8):1445–1457. doi: 10.1038/s41366-018-0111-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Benoit SC, et al. Palmitic acid mediates hypothalamic insulin resistance by altering PKC-theta subcellular localization in rodents. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(9):2577–2589. doi: 10.1172/JCI36714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Qiao Q, et al. Metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease. Ann Clin Biochem. 2007;44:232–263. doi: 10.1258/000456307780480963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wilson PW, et al. Metabolic syndrome as a precursor of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2005;112:3066–3072. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.539528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dokken BB, et al. The Pathophysiology of cardiovascular disease and diabetes: beyond blood pressure and lipids. Diabetes Spectr. 2008;21(3):160–165. doi: 10.2337/diaspect.21.3.160. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Leon BM, Maddox TM. Diabetes and cardiovascular disease: epidemiology, biological mechanisms, treatment recommendations and future research. World J Diabetes. 2015;6(13):1246–1258. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v6.i13.1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mozaffarian D. Saturated fatty acids and type 2 diabetes: more evidence to re-invent dietary guidelines. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2(10):770–772. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(14)70166-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ebbesson SO, et al. Fatty acids linked to cardiovascular mortality are associated with risk factors. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2015;74:28055. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v74.28055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Briggs MA, Petersen KS, Kris-Etherton PM. Saturated fatty acids and cardiovascular disease: replacements for saturated fat to reduce cardiovascular risk. Healthcare. 2017;5(2):29. doi: 10.3390/healthcare5020029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Knowles CJ, et al. Palmitate diet-induced loss of cardiac caveolin-3: a novel mechanism for lipid-induced contractile dysfunction. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61369. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mao Y, et al. STING-IRF3 triggers endothelial inflammation in response to free fatty acid-induced mitochondrial damage in diet-induced obesity. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2017;37:920–929. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.117.309017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang XL, et al. Free fatty acids inhibit insulin signaling-stimulated endothelial nitric oxide synthase activation through upregulating PTEN or inhibiting Akt kinase. Diabetes. 2006;55:2301–2310. doi: 10.2337/db05-1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yuan L, et al. Palmitic acid dysregulates the Hippo-YAP pathway and inhibits angiogenesis by inducing mitochondrial damage and activating the cytosolic DNA sensor cGAS-STING-IRF3 signaling mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:15002–15015. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.804005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Trombetta A, et al. Increase of palmitic acid concentration impairs endothelial progenitor cell and bone marrow-derived progenitor cell bioavailability: role of the STAT5/PPARgamma transcriptional complex. Diabetes. 2013;62:1245–1257. doi: 10.2337/db12-0646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Huang JV, et al. PPAR-gamma as a therapeutic target in cardiovascular disease: evidence and uncertainty. J Lipid Res. 2012;53:1738–1754. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R024505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kvandova M, Majzunova M, Dovinova I. The role of PPARgamma in cardiovascular diseases. Physiol Res. 2016;65:S343–S363. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.933439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cheon HG, Cho YS. Protection of palmitic acid-mediated lipotoxicity by arachidonic acid via channeling of palmitic acid into triglycerides in C2C12. J Biomed Sci. 2014;21:13. doi: 10.1186/1423-0127-21-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sinha S, et al. Fatty acid-induced insulin resistance in L6 myotubes is prevented by inhibition of activation and nuclear localization of nuclear factor kappa B. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:41294–41301. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406514200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chen YP, et al. Acute hypoxic preconditioning prevents palmitic acid-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis via switching metabolic GLUT4-glucose pathway back to CD36-fatty acid dependent. J Cell Biol. 2018;119:3363–3372. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bairwa SC, Parajuli N, Dyck JR. The role of AMPK in cardiomyocyte health and survival. Biochimica Biophysica Acta. 2016;1862:2199–2210. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2016.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Huang JP, et al. Impairment of insulin-stimulated Akt/GLUT4 signaling is associated with cardiac contractile dysfunction and aggravates I/R injury in STZ-diabetic rats. J Biochem Sci. 2009;16:77. doi: 10.1186/1423-0127-16-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Li J, et al. PKC-zeta interacts with STAT3 and promotes its activation in cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. J Pharma Sci. 2016;132:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jphs.2016.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kwan HY, et al. Subcutaneous adipocytes promote melanoma cell growth by activating the Akt signaling pathway: role of palmitic acid. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:30525–30537. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.593210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wong RH, et al. A role of DNA-PK for the metabolic gene regulation in response to insulin. Cell. 2009;136:1056–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wang Y, et al. Transcriptional regulation of hepatic lipogenesis. Nature reviews. Mol Cell Biol. 2015;16:678–689. doi: 10.1038/nrm4074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.DeBerardinis RJ, et al. Beyond aerobic glycolysis: transformed cells can engage in glutamine metabolism that exceeds the requirement for protein and nucleotide synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:19345–19350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709747104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kwan HY, et al. Dietary lipids and adipocytes: potential therapeutic targets in cancers. J Nutr Biochem. 2015;26:303–311. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Little JL, Kridel SJ. Fatty acid synthase activity in tumor cells. Subcell Biochem. 2008;49:169–194. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-8831-5_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rohrig F, Schulze A. The multifaceted roles of fatty acid synthesis in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:732–749. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kwan HY, et al. The anticancer effect of oridonin is mediated by fatty acid synthase suppression in human colorectal cancer cells. J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:182–192. doi: 10.1007/s00535-012-0612-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ventura R, et al. Inhibition of de novo palmitate synthesis by fatty acid synthase induces apoptosis in tumor cells by remodeling cell membranes, inhibiting signaling pathways, and reprogramming gene expression. EBioMedicine. 2015;2:808–824. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bensaad K, et al. Fatty acid uptake and lipid storage induced by HIF-1alpha contribute to cell growth and survival after hypoxia-reoxygenation. Cell Rep. 2014;9:349–365. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.08.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kuemmerle NB, et al. Lipoprotein lipase links dietary fat to solid tumor cell proliferation. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10:427–436. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Laurent V, et al. Periprostatic adipocytes act as a driving force for prostate cancer progression in obesity. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10230. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dirat B, et al. Cancer-associated adipocytes exhibit an activated phenotype and contribute to breast cancer invasion. Cancer Res. 2011;71:2455–2465. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Okumura T, et al. Extra-pancreatic invasion induces lipolytic and fibrotic changes in the adipose microenvironment, with released fatty acids enhancing the invasiveness of pancreatic cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2017;8:18280–18295. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wang YY, et al. Mammary adipocytes stimulate breast cancer invasion through metabolic remodeling of tumor cells. JCI Insight. 2017;2:e87489. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.87489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Beloribi-Djefaflia S, Vasseur S, Guillaumond F. Lipid metabolic reprogramming in cancer cells. Oncogenesis. 2016;5:e189. doi: 10.1038/oncsis.2015.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Louie SM, et al. Cancer cells incorporate and remodel exogenous palmitate into structural and oncogenic signaling lipids. Biochimica Biophysica Acta. 2013;1831:1566–1572. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2013.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Benjamin DI, Cravatt BF, Nomura DK. Global profiling strategies for mapping dysregulated metabolic pathways in cancer. Cell Metab. 2012;16:565–577. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Pascual G, et al. Targeting metastasis-initiating cells through the fatty acid receptor CD36. Nature. 2017;541:41–45. doi: 10.1038/nature20791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Nath A, et al. Elevated free fatty acid uptake via CD36 promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition in hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci Reps. 2015;5:14752. doi: 10.1038/srep14752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Balaban S, et al. Adipocyte lipolysis links obesity to breast cancer growth: adipocyte-derived fatty acids drive breast cancer cell proliferation and migration. Cancer Metab. 2017;5:1. doi: 10.1186/s40170-016-0163-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Binker-Cosen MJ, et al. Palmitic acid increases invasiveness of pancreatic cancer cells AsPC-1 through TLR4/ROS/NF-kappaB/MMP-9 signaling pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;484:52–158. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lin L, et al. Functional lipidomics: palmitic acid impairs hepatocellular carcinoma development by modulating membrane fluidity and glucose metabolism. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.) 2017;66:432–448. doi: 10.1002/hep.29033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Baumann J, et al. Palmitate-induced ER stress increases trastuzumab sensitivity in HER2/neu-positive breast cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:55. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2611-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Fiorentino M, et al. verexpression of fatty acid synthase is associated with palmitoylation of Wnt1 and cytoplasmic stabilization of beta-catenin in prostate cancer. Lab Investig Tech Methods Pathol. 2008;88:1340–1348. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2008.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sefton BM, et al. The transforming proteins of Rous sarcoma virus, Harvey sarcoma virus and Abelson virus contain tightly bound lipid. Cell. 1982;31:465–474. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90139-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Buss JE, Sefton BM. Direct identification of palmitic acid as the lipid attached to p21ras. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:116–122. doi: 10.1128/MCB.6.1.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hancock JF, et al. All ras proteins are polyisoprenylated but only some are palmitoylated. Cell. 1989;57:1167–1177. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90054-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kato K, Der CJ, Buss JE. Prenoids and palmitate: lipids that control the biological activity of Ras proteins. Semin Cancer Biol. 1992;3:179–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Marwarha G, et al. Palmitate increases beta-site a betaPP-cleavage enzyme 1 activity and amyloid-beta genesis by evoking endoplasmic reticulum stress and subsequent C/EBP homologous protein activation. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;57:907–925. doi: 10.3233/JAD-161130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Greenwood CE, Winocur G. High-fat diets, insulin resistance and declining cognitive function. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26(Suppl 1):42–45. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Baierle M, et al. Fatty acid status and its relationship to cognitive decline and homocysteine levels in the elderly. Nutrients. 1973;6(9):3624–3640. doi: 10.3390/nu6093624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Dhopeshwarkar GA, Mead JF. Uptake and transport of fatty acids into the brain and the role of the blood-brain barrier system. Adv Lipid Res. 1973;11:109–142. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-024911-4.50010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Liu L, et al. Palmitate induces transcriptional regulation of BACE1 and presenilin by STAT3 in neurons mediated by astrocytes. Exp Neurol. 2013;248:482–490. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Patil S, et al. Palmitic acid-treated astrocytes induce BACE1 upregulation and accumulation of C-terminal fragment of APP in primary cortical neurons. Neurosci Lett. 2006;406:55–59. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Patil S, Melrose J, Chan C. Involvement of astroglial ceramide in palmitic acid-induced Alzheimer-like changes in primary neurons. Eur Neurosci. 2007;26:2131–2141. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05797.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Wong KL, et al. Palmitic acid-induced lipotoxicity and protection by (+)-catechin in rat cortical astrocytes. Pharmacol Rep. 2014;66:1106–1113. doi: 10.1016/j.pharep.2014.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Park HR, et al. Lipotoxicity of palmitic acid on neural progenitor cells and hippocampal neurogenesis. Toxicol Res. 2011;27:103–110. doi: 10.5487/TR.2011.27.2.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Ng YW, Say YH. Palmitic acid induces neurotoxicity and gliatoxicity in SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma and T98G human glioblastoma cells. Peer J. 2018;6:e4696. doi: 10.7717/peerj.4696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Conteduca V, et al. Association among metabolic syndrome, inflammation, and survival in prostate cancer. Urol Oncol. 2018;36:240.e241-240. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2018.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Lopez-Candales A, et al. Linking chronic inflammation with cardiovascular disease: from normal aging to the metabolic syndrome. J Nat Sci. 2017;3(4):pii:e341. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Wen H, et al. Fatty acid-induced NLRP3-ASC inflammasome activation interferes with insulin signaling. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:408–415. doi: 10.1038/ni.2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Shi H, et al. TLR4 links innate immunity and fatty acid-induced insulin resistance. The J Clin Invest. 2006;116:3015–3025. doi: 10.1172/JCI28898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Nguyen MT, et al. A subpopulation of macrophages infiltrates hypertrophic adipose tissue and is activated by free fatty acids via Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 and JNK-dependent pathways. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:35279–35292. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706762200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Laine PS, et al. Palmitic acid induces IP-10 expression in human macrophages via NF-kappaB activation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;358:150–155. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.04.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Suganami T, et al. Role of the Toll-like receptor 4/NF-kappaB pathway in saturated fatty acid-induced inflammatory changes in the interaction between adipocytes and macrophages. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:84–91. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000251608.09329.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Suganami T, et al. Attenuation of obesity-induced adipose tissue inflammation in C3H/HeJ mice carrying a Toll-like receptor 4 mutation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;354:45–49. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.12.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Song MJ, et al. Activation of Toll-like receptor 4 is associated with insulin resistance in adipocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;346:739–745. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.05.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Gupta S, et al. Saturated long-chain fatty acids activate inflammatory signaling in astrocytes. J Nutr Biochem. 2012;120:1060–1071. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2012.07660.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Tian D, et al. Overexpression of steroidogenic acute regulatory protein in rat aortic endothelial cells attenuates palmitic acid-induced inflammation and reduction in nitric oxide bioavailability. Cardiovas Diabetol. 2012;11:144. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-11-144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Li W, et al. EGFR inhibition blocks palmitic acid-induced inflammation in cardiomyocytes and prevents hyperlipidemia-induced cardiac injury in mice. Sci Rep. 2016;6:24580. doi: 10.1038/srep24580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Murumalla RK, et al. Fatty acids do not pay the toll: effect of SFA and PUFA on human adipose tissue and mature adipocytes inflammation. Lipids Health Dis. 2012;11:175. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-11-175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Wang Y, et al. Saturated palmitic acid induces myocardial inflammatory injuries through direct binding to TLR4 accessory protein MD2. Nat Comm. 2017;8:13997. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]