Abstract

Exosomes, a type of small extracellular vesicles (sEVs), are secreted membrane vesicles that are derived from various cell types, including cancer cells, mesenchymal stem cells, and immune cells via multivesicular bodies (MVBs). These sEVs contain RNAs (mRNA, miRNA, lncRNA, and rRNA), lipids, DNA, proteins, and metabolites, all of which mediate cell-to-cell communication. This communication is known to be implicated in a diverse set of diseases such as cancers and their metastases and degenerative diseases. The molecular mechanisms, by which proteins are modified and sorted to sEVs, are not fully understood. Various cellular processes, including degradation, transcription, DNA repair, cell cycle, signal transduction, and autophagy, are known to be associated with ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like proteins (UBLs). Recent studies have revealed that ubiquitin and UBLs also regulate MVBs and protein sorting to sEVs. Ubiquitin-like 3 (UBL3)/membrane-anchored Ub-fold protein (MUB) acts as a post-translational modification (PTM) factor to regulate efficient protein sorting to sEVs. In this review, we focus on the mechanism of PTM by ubiquitin and UBLs and the pathway of protein sorting into sEVs and discuss the potential biological significance of these processes.

Keywords: Post-translational modification, Small extracellular vesicle, Exosome, Ubiquitin, Ubiquitin-like protein, Multivesicular body

Introduction

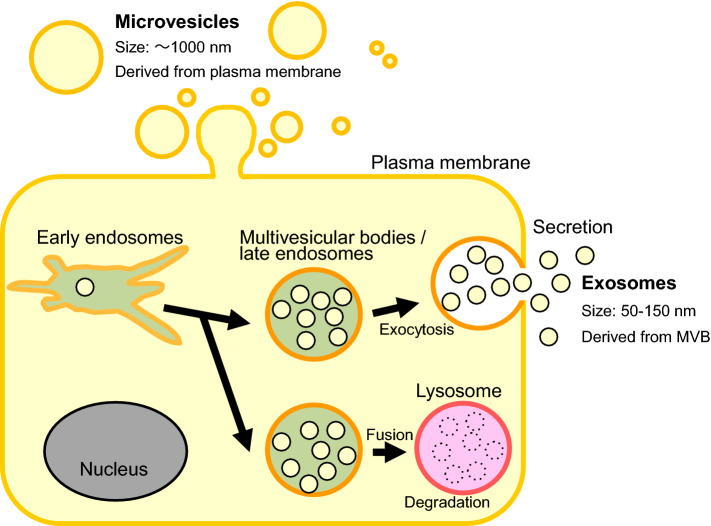

In 1987, exosomes were first described in maturing reticulocytes [1]. Via subsequent seminal analyses, secretory vesicles released into the extracellular environment were characterised and were collectively named as extracellular vesicles (EVs), which are divided into several categories. The two major EVs, those that are directly released from the plasma membrane and those that are secreted via MVBs, are called microvesicles and exosomes, respectively (Fig. 1). Microvesicles, including relatively larger EVs with a diameter of 1000 nm, are purified by 10,000×g centrifugation. Conversely, because exosomes are nanometer-sized vesicles with a diameter of ≤ 150 nm, efficient purification requires ultracentrifugation at 100,000×g [2]. Since vesicles with diameters of ≤ 150 nm are also present among microvesicles, EVs purified by ultracentrifugation at 100,000×g do not constitute the sole fraction of exosomes [2]. In this review, to avoid confusion, we refer to nanometer-sized vesicles secreted into the extracellular environment as small extracellular vesicles (sEVs).

Fig. 1.

Types of extracellular vesicles. Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are divided into two types: microvesicles that are directly secreted from the plasma membrane and exosomes that are secreted via multivesicular bodies (MVBs). Microvesicles are relatively larger EVs with a diameter of 1000 nm. In contrast, exosomes are nanometer-sized vesicles with a diameter of ≤ 150 nm [1–3]. MVBs may be released extracellularly as exosomes or fuse with lysosomes, which degrade the contents of the MVBs [3, 33]

sEVs mediate cell-to-cell communication by transporting RNAs (mRNAs, miRNAs, lncRNAs, rRNA, and tRNA), proteins, lipids, DNA, and a variety of metabolites [3–6]. The delivery of proteins between cells by sEVs is related to tumour progression [7]. Expressed in glioma cells, activated mutant epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) propagates its signaling via sEVs [8]. Receptor-type tyrosine kinase MET, present in sEVs released from melanoma, is involved in metastasis [9]. Furthermore, neurodegenerative disease-related proteins, such as amyloid beta, tau, α-Synuclein, and prions, are also packaged inside sEVs and then spread out in the brain [10–14].

These findings indicate the contribution made by the transportation of intracellular proteins via sEVs in various types of diseases. However, the mechanism underlying the sorting of proteins to sEVs remains unclear.

After proteins are synthesised in the cells, they are processed by various post-translational modifications (PTMs) including phosphorylation, acetylation, methylation, and ubiquitination that influence a variety of cellular processes. Proteins sorted to sEVs also undergo PTM by processes such as phosphorylation, acetylation, lipidation, and ubiquitination. Several excellent reviews cover PTMs such as phosphorylation, acetylation, oxidation, and citrullination [15, 16].

One of the major protein degradation systems within the cell, the ubiquitin-dependent modification system, is involved in a variety of cellular processes such as cell cycling [17], transcriptional activation [18], apoptosis [19], control of circadian rhythm [20], neurodegeneration [21], and neuronal plasticity [22–26]. Protein ubiquitination involves three classes of enzymes: E1 ubiquitin-activating enzymes, E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes, and E3 ubiquitin–protein ligases. Target proteins in these multienzyme complexes are conjugated with the polymeric forms of ubiquitin, triggering their degradation by proteasome [27], well known as ubiquitin–proteasome systems. In addition to protein degradation, various biological processes such as endocytosis, DNA modification, and signal transduction are also known to involve ubiquitination. Several proteins have been reported to have a ubiquitin-like sequence, referred to as a ‘UBL domain’ [28, 29]. Several ubiquitin-like proteins (UBLs) reportedly act as post-translational modifiers [28]; these include small ubiquitin-like modifiers (SUMOs) [30] and neuronal precursor cell-expressed, developmentally down-regulated 8 (Nedd8) [31]. UBL3 has also recently been characterised to have PTM activities [32]. It has been reported that proteins in sEV are modified by these UBLs, and there are many reports to show that UBLs are involved in the regulation of MVBs and sEVs (Table 1). In this review, we focus on the protein PTMs by ubiquitin and UBLs and introduce recent findings regarding the protein sorting pathway into sEVs.

Table 1.

Functions, related diseases, enzymes, and target proteins of ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like proteins (UBLs)

| Name | Other names | Function | Related diseases | E1 | E2 | E3 | Target proteins in sEV | Target proteins which located in MVB or related with MVB | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UBLs for which E1 and/or E2 have been identified | Ubiquitin | Proteasomal and lysosomal degradation, endocytosis, DNA repair, transcription, chromatin structure | Cancer, Parkinson’s disease, neuromuscular diseases, and others | UBA1, UBA6 | Many | Many | FasL, GW812, mycobacterial proteins, 40S ribosomal protein S7, Myosin heavy chain, Histones, Ezrin, HSP70, and more | FasL, GW812 | [69, 70, 74–78, 80–85, 88–95, 144, 159] | |

| Nedd8 | Regulation of E3 ligases, transcription, proteasomal degradation | Cancer, infection, and others | NAE1-UBA3 | UBC12 (UBE2M), UBE2F | RBX1/2, DCN1, MDM2, c-CBL, FBXO11 | N/D | p53 | [31, 95, 107, 109–111, 114–116], | ||

| SUMO | Nuclear localisation, transcriptional regulation, DNA repair, antagonizing ubiquitination, recruitment of E3 ubiquitin ligases | Parkinson’s disease, and others | SAE1-UBA2 | UBC9 | PIASs, RanBP2, CBX4, Pc2 | α-Synuclein, hnRNP2B1 | p53 | [115, 116, 128–130, 166] | ||

| ISG15 | G1P2, IP17 | IFN response, biogenesis of MVB | Inflammation, and others | UBA7 (UBE1L) | UBCH8, UBCH6 | HERC5, HHARI, EFP | N/D | TSG101 | [137, 138] | |

| ATG8 | GABARAPL2, LC3 | Autophagy | Cancer, neurodegeneration, and others | ATG7 | ATG3 | ATG12-ATG5-ATG16L1 | N/D | N/D | [140–142, 144, 155, 159] | |

| ATG12 | APG12 | Autophagy | Cancer, neurodegeneration, and others | ATG7 | ATG10 | – | N/D | ATG3, Alix | [140–142, 144, 149, 155, 156, 159] | |

| FAT10 | diubiquitin, ubiquitin D | Proteasomal degradation, apoptosis, carcinogenesis | Lymphocyte cell death, cancer | UBA6 | USE1 | N/D | N/D | p53 | [115, 117, 172–174, 176] | |

| UFM1 | BM-002, C13orf20 | Erythroid differentiation | Anemia, brain development | UBA5 | UFC1 | UFL1 | N/D | N/D | [180, 183] | |

| URM1 | C9orf74 | tRNA thiolation, nutrient sensing, oxidative stress response | N/D | UBA4 | N/D | N/D | N/D | N/D | [95, 184–186] | |

| UBLs for which E1 has not been identified | UBL3 | MUB | Sorting to MVBs and sEVs | Cancer | N/D | N/D | N/D | Tubulin, Ras | N/D | [32, 161–165] |

| Hub1 | UBL5, beacon | Pre-mRNA splicing, Fanconi anemia pathway, mitochondrial stress | Fanconi anemia | N/D | N/D | N/D | N/D | N/D | [190, 192, 193] | |

| MNSFβ | FUB1, Fubi | Anti-inflammatory, anti-proliferative effect | Inflammation | N/D | N/D | N/D | N/D | N/D | [194, 195] |

– not necessary, N/D not determined

Protein sorting to MVB and sEV

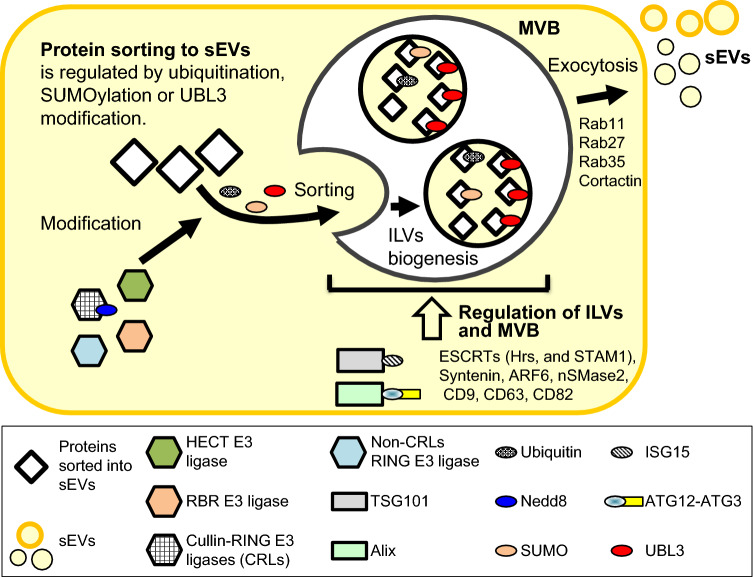

Exosomes originate from early endosomes incorporated into the cells by endocytosis. The interaction between these early endosomes and the Golgi apparatus and the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) leads to the degradation and secretion of proteins. The limiting membrane of early endosomes invaginates and buds into the lumen of the organelle to form intraluminal vesicles (ILVs). During this process, the endosomes have matured into MVB/late endosomes. MVBs may fuse with the plasma membrane, releasing their contents as exosomes, or fuse with lysosomes, which degrade the MVB contents (Fig. 1) [3, 33]. The MVBs must fuse with the plasma membrane prior to exosome secretion. To date, the essential regulators of this process have been characterised. For example, Rabs are small G proteins which belong to the Ras superfamily. These proteins act as molecular switches for membrane trafficking and regulate the sorting of various protein via vesicular transport. The Rab family is conserved across all eukaryotes and has also been identified in budding yeast, nematodes, and Drosophila. Seventy Rab isoforms have been identified in humans [34, 35], of which Rab GTPases (Rab11, Rab27, and Rab35) are involved in the transport of MVBs to the plasma membrane and secretion as sEVs [36–38]. In addition, cortactin, an actin-binding protein, is an important factor involved in cell migration, endocytosis, invasion, and metastasis [39, 40]. This protein is strongly expressed in invasive cancer cells and has been identified as a regulator of membrane trafficking. Cortactin also serves as a positive regulator of late endosomal docking and exosome secretion [41].

The components of the endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT) are known to be involved in ILV and MVB biogenesis. The ESCRT complex comprises approximately 20 proteins that assemble into four distinct complexes (ESCRT-0, -I, -II, and -III) with associated proteins [ALG-2-interacting protein X (Alix, also known as programmed cell death 6-interacting protein), vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein 4 (VPS4) and VTA1] [42, 43]. Both hepatocyte growth factor-regulated tyrosine kinase substrate (Hrs) and STAM1, components of ESCRT-0, recognise the ubiquitinated cargoes, and then Hrs recruits TSG101 of the ESCRT-I complex, which has roles in recruiting ESCRT-III via ESCRT-II or Alix for membrane deformation and abscission. Interestingly, the silencing of Hrs, STAM1, or TSG101 reduced the secretion of sEVs [44]. Syntenin, known to interact with Alix, has also been shown to regulate ILVs biogenesis [45]. Furthermore, the activity of small GTPase ADP-ribosylation factor 6 (ARF6), which interacts genetically with Syntenin [46], is also involved in this Syntenin–Alix ILV biogenesis [47].

In contrast, ESCRT-independent ILV biogenesis also exists. MVB biogenesis, even under depletion of four key subunits of ESCRTs (Hrs, TSG101, Vps22, and Vps24), is still observed [48]. In ESCRT-independent ILV biogenesis, the requirement of ceramide generation by neutral sphingomyelinase 2 (nSMase 2) was reported [49]. In addition, Pmel, β-catenin, and tetraspanin membrane proteins CD9, CD63, and CD82 are also sorted to ILVs in an ESCRT-independent manner [50–52]. Interestingly, these tetraspanin proteins, CD9, CD63, and CD82, are directly involved in the sorting of proteins to ILVs [51, 52].

In the canonical proteasomal targeting signal, target proteins conjugated with four ubiquitin chains are linked through lysine 48 and are captured by proteasomes. The ubiquitinated proteins are then degraded by proteasomes [53]. Membrane proteins such as EGFRs, however, are monoubiquitinated in the intracellular region. The monoubiquitinated receptors are sorted to the early endosome, recognised by ESCRT-0, and transported to the ILVs of MVB. The ESCRT complex, to remove ubiquitin from the ubiquitinated proteins before incorporation into ILVs, recruits deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) [33, 54]. Finally, after fusion of the MVB with the lysosome, the MVB contents are degraded.

Mechanisms of cellular uptake of sEVs by recipient cells

After release from cells, the sEVs are taken up and incorporated with recipient cells. The uptake of sEVs involved both clathrin-mediated and clathrin-independent mechanism [55, 56]. The latter category includes macropinocytosis [57], phagocytosis [58], and lipid raft-mediated endocytosis [59]. The compositions of the plasma membranes both of the sEVs and recipient cells affects the degree of sEV uptake [60]. Although CD47, known as ‘don’t eat me signal’, suppresses exosomal clearance by monocytes, this protein also facilitates the macropinocytosis of exosomes carrying oncogenic Ras [61]. The activation of EGFR and oncogenic K-Ras also increase sEV uptake by inducing macropinocytosis [57]. The finding that cholesterol depletion disrupts lipid rafts and thus reduces the incorporation of sEVs highlights the importance of the lipid composition of the recipient cell plasma membrane [55]. For the purpose of clinical application, L17E, a peptide modified from the endosomolytic M-lycotoxin of spider venom, was developed to deliver extracellular proteins to recipient cells in clinical application. The cytosolic delivery of L17E induces macropinocytosis and enhances the uptake of sEV [62]. Each sEV is recognised specifically by and incorporated into recipient cells via a variety of mechanisms in a cell-context dependent manner. Cancer metastasis and disease propagation are also affected by sEV uptake. Therefore, the elucidation of the precise mechanisms of uptake of sEVs is important for the clinical application of sEVs.

E3 ubiquitin ligases and sEVs

E3 ubiquitin ligases are involved in various biological processes, including protein sorting to sEVs via ubiquitination. Although the molecular basis underlying the ‘cargoes of sEVs’ has not been well characterised, recent studies have reported that E3 ubiquitin ligases and ubiquitination are involved in protein sorting to sEVs. More than 600 human E3 ubiquitin ligases have been identified [63]. E3 ubiquitin ligases from the conserved structural domains and the mechanism by which ubiquitin is transferred from the E2 to the substrate are classified as three families: the HECT E3 ligases, the RING E3 ligases, and the RING-between-RING (RBR) E3 ligases. Enzyme activity in HECT and RBR E3 ligases catalyses the attachment of ubiquitin to the substrate directly. In contrast, RING E3 ligases, to transfer ubiquitin to the target proteins, bind to both E2 ~ Ub thioester and substrate, catalysing an attack of the substrate lysine on the thioester [64, 65].

The ubiquitination of latent membrane protein 2A (LMP2A) is likely mediated by HECT-type Nedd4 family ubiquitin ligase [66–68]. LMP2A is an Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-encoded protein implicated in regulating viral latency and pathogenesis in EBV-infected cells. LMP2A is found to be secreted in sEVs [69], and cholesterol depletion increased the level of LMP2A in sEVs and consequently increased the ubiquitination of LMP2A in sEVs. The Nedd4 family-interacting protein 1(Ndfip1) is released as sEVs [70]. Using Brefeldin A and Exo-1, the representative inhibitors of protein transport from the ER to the Golgi apparatus, it was shown that the secretion of Ndfip1 involves the classical ER-Golgi pathway. Interestingly, while the HECT-type E3 ubiquitin ligase family (Nedd4, Nedd4-2, and Itch), the binding molecules of Ndfip1, are not found in sEVs, overexpression of Ndfip1 promotes the sorting of these Nedd4 family proteins to sEVs and an increase in the ubiquitination of Ndfip1 in sEVs by co-transfection with ubiquitin. The Nedd4 family, via its WW domain through the PY motif, binds to late (L) domain-containing proteins [71–73]. A WW-tagged form of Cre recombinase was used to demonstrate WW tag-mediated sorting to sEVs. Specifically, this tagged protein induced the ubiquitination of Cre protein by Ndfip. Furthermore, although the Cre recombinase itself is not efficiently sorted to sEV, WW-Cre is sorted to sEVs when co-transfected with Ndfip. Thus, WW tag is useful for sorting to sEVs [74].

The causative gene for an autosomal recessive type of Parkinson’s disease, Parkin, is known as an RBR E3 ubiquitin ligase dependent on phosphorylated ubiquitin. Phosphorylated ubiquitin by PINK1 recruits and activates Parkin in mitochondria. Parkin is involved in the ubiquitination of damaged mitochondria, leading to selective autophagy (mitophagy) [75, 76]. In Parkin-deficient fibroblasts, the numbers of ILVs within MVBs and sEVs were significantly increased and that the overexpression of wild type, but not mutant, Parkin led to a decrease in the secretion of sEVs [77].

In summary, the above findings exemplify the involvement of E3 ubiquitin ligases in ILV and MVB biogenesis and sEV sorting. As shown below, sEVs contain ubiquitinated proteins. Moreover, various UBLs play unique role in the control of sEV and exhibit crosstalk with the ubiquitination pathway. Therefore, ubiquitination by E3 ubiquitin ligases and UBLs likely contributes to the regulation of sEVs.

Detection of ubiquitinated proteins in sEVs

In 2004, the wide range of molecular weight forms of ubiquitin and ubiquitination in sEVs purified from human urine were identified by mass spectrometry and immunoblot [78]. This finding suggested ubiquitin modification in sEVs. A subsequent report described both mono- and polyubiquitination in sEVs purified from mouse dendritic cells and EB virus-transformed human B-cell line RN were reported [79]. Fas ligand (FasL), a type II transmembrane protein and a member of the tumour necrosis factor receptors, on binding with its receptor FAS, induces apoptosis. Previous studies have reported the sorting of FasL to MVB and its release to the extracellular environment [80–84]. However, the sorting mechanism was not fully understood. Both ubiquitination and phosphorylation have been identified as necessary for the sorting of FasL to MVBs [85]. It was noted that the disappearance of mono-ubiquitination by mutation of lysines in the proline-rich domain of FasL, a mutation that reduced MVB localisation of FasL [85]. Intriguingly, the dietary polyphenol, curcumin, increased the level of ubiquitinated proteins in TS/A breast cancer cells [86].

P bodies and GW bodies are particle structures comprising RNA–protein complexes characteristically found in the cytoplasm and are involved in miRNA-mediated posttranscriptional silencing [87]. It was shown that the GW-body component protein GW182 is localised to MVBs and enriched in the sEVs released from monocytes (mono-mac cell line). On the other hand, the P-body component did not co-localise with MVBs. Interestingly, analysis of immunoprecipitated products with anti-GW812 antibody led to the detection of ubiquitinated proteins using anti-ubiquitin antibody (FK2) [88].

Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected macrophages release exosomes containing soluble mycobacterial proteins [89, 90]. On sEVs purified from infected macrophages (RAW264.7), ubiquitination of mycobacterial proteins was detected, indicating the contents of the released sEVs as ubiquitinated mycobacterial proteins. Using ubiquitination inhibitor PYR-41 or a mutation of lysines in the mycobacterial protein, it was shown that ubiquitination is necessary for sorting mycobacterial proteins to sEVs [91].

Comprehensive proteomics analyses were performed to detect ubiquitinated proteins in sEV. Purified 30–100 nm vesicles secreted from an insulin-secreting murine cell line (NIT-1) were prepared, and after performing one-dimensional SDS gel electrophoresis, proteomics analysis identified 405 proteins [92]. Among them, 17 ubiquitin-related proteins such as ubiquitin and ubiquitin-activating enzyme E1 were identified. Subsequent mass spectrometry and tryptic digestion led to the detection of ubiquitinated peptides containing two glycine residues (GlyGly) conjugated with lysine residues of the substrate peptides (KGG). By analysing the peptides purified from the gel at a high molecular weight (≥ 175 kDa), it was demonstrated that protein polyubiquitination in sEVs by identifying the conjugation of GlyGly of ubiquitin with lysine 48 (K48) of ubiquitin [92]. Proteomics analyses on sEVs released from Drosophila melanogaster Kc167 and S2 cells were reported. Purified sEVs were in a size range of 20 nm–90 nm in diameter and did not contain apoptotic debris or other materials. In the proteomics analysis, 269 proteins, including ubiquitin, ubiquitin–protein ligase Su (dx), ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2-17, and probable ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolases E3 were identified. Furthermore, the ubiquitination of 17 proteins was detected through identification of 19 peptides comprising lysine residues modified with GlyGly as the remnants of ubiquitin–conjugation. Interestingly, GlyGly on lysine 63 (K63) of ubiquitin was also detected, indicating the occurrence of K63-linked polyubiquitination in the sEVs [93].

In 2014, to identify ubiquitinated proteins in sEVs, comprehensive proteomics analysis on the sEVs released from myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC) was performed [94]. For this purpose, immunoprecipitation on purified sEVs with anti-ubiquitin antibody, tryptic digestion, immunoprecipitation of peptides with anti-diglycyl-lysine antibody GX41, and proteomics analysis were performed. Fifty ubiquitinated proteins, including Histones (H1.0, H1.2, H1.3, H1.4, H1.5, H1t, H2A.x, and H4), Ezrin and HSP70, were identified. Proteomics analysis on sEV purified from human urine was also performed and it was shown that 15% of the over 6000 proteins identified were ubiquitinated [95]. From 866 peptides, 1084 ubiquitinated sites were identified. This analysis led to the elucidation of several motifs containing either lysine or arginine residues on the N-terminal side (within -6 positions) of the ubiquitinated lysine residue. To determine the proportion of ubiquitinated forms (mono- and polyubiquitinated) on these identified proteins, the mass difference between ubiquitinated and unmodified forms of each protein was calculated. The analysis revealed the proportions as 43% for monoubiquitinated protein, 3% for multi-mono-ubiquitination, and 54% for polyubiquitination or mono/multi-mono-ubiquitination with other PTMs or multimeric forms of protein. In that study, bioinformatics analysis of ubiquitinated proteins also revealed the presence of transcription factors with statistical significance [95]. In addition, quantification of polyubiquitin chain topologies revealed that K63-linked polyubiquitin chains (K63) were most frequently observed (51.2%), followed by K48 (29.4%), K11 (10.4%), K6 (4.3%), K29 (3.4%), K33 (1.2%), and K27 (0.2%). Various roles are played by different topologies of polyubiquitin chains [96]. In general, K48-linked chains are associated with proteasomal degradation, whereas K63-linkage is involved in a variety of other processes, including lysosomal degradation, DNA repair, and transcriptional regulation [96]. These results indicated that protein sorting to sEVs could be controlled by K63-linked chains.

Several studies have suggested that deubiquitinases are recruited to the ESCRT complex and cleave ubiquitin from cargo proteins prior to ESCRT-III-mediated ILV abscission and the incorporation of cargo proteins into the ILVs [97–100]. The observation that one subset of proteins is ubiquitinated in sEVs suggests that despite the importance of the deubiquitination in terms of protein incorporation into ILV and MVB, this factor may not be required for protein sorting to sEVs. Rather, other mechanisms may play a role in protein sorting to sEVs, or an uncharacterised cellular mechanism may enable proteins to evade deubiquitination. Moreover, proteins sorted to sEVs independently of ubiquitination may be ubiquitinated subsequently in MVBs or sEVs. Alternatively, ubiquitinated proteins may be deubiquitinated again in sEV. The latter speculation is supported by the existence of ubiquitinating and deubiquitinating enzymes in sEVs, including the E3 ubiquitin ligases including HECW1, HUWE1, ITCH, LRSAM1, NEDD4L, RNF213, UBR4, and the deubiquitinases including BRCC36 and OTUB1 [92–95]. ESCRT-independent protein sorting to MVB without deubiquitination could also be possible [95]. Regardless, the mechanisms that coordinate protein modification and transport require further investigation.

At the end of this section, we introduce examples to show that sorting of proteins to sEVs is not solely dependent on ubiquitination. In various cell types, major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC-II) is specifically sorted to sEVs and the cytoplasmic tail of the MHC-II β-chain is ubiquitinated [101–103]. Ubiquitin E3 ligase MARCH8 proteins have identified as key players in the trafficking of MHC-II [104]. Based on these reports, effects of overexpression of MARCH8 and mutation of all cytoplasmic lysine residues on human leukocyte antigens, MHC-II (HLA-DR), were studied. It was concluded that the ubiquitination of the MHC-II cytoplasmic tail is not an absolute requirement for sorting into sEVs, since mutants are still sorted into sEVs [105].

The sorting of only a subset of proteins in sEVs could be regulated by ubiquitination, indicating that ubiquitination is important, but not general for all proteins sorted to sEVs. Moreover, the localisation of several UBLs, such as Nedd8, UBL3 and Urm1, to MVBs and sEVs suggests that other UBLs might play a crucial role in the sorting of proteins to sEVs [95].

Physiological and pathological roles of Neddylation

Nedd8, known as one of UBLs, acts as a PTM factor. Cullins are scaffolding proteins for the multi-subunit Cullin–RING E3 ubiquitin ligases (CRLs) complex, which includes the SCF (Skp1–Cullin–F-box) complex. There are seven Cullins (CUL1, 2, 3, 4a, 4b, 5, and 7) and parkin-like cytoplasmic protein (Parc) in human genome [106]. The Cullins are modified by Nedd8, a modification shown to increase the ubiquitination activity of CRLs [31, 106, 107].

A recent investigation revealed physiological and pathological roles for Neddylation. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP-1) is a reversible PTM involved in DNA repair, transcriptional regulation, and apoptosis. A novel role of Nedd8 regulating the activity of PARP-1 under oxidative stress is elucidated [108]. The HECT-type ubiquitin ligase Smurf1 (Smad ubiquitylation regulatory factor 1) regulate TGF-β and BMP signaling. Smurf1 and 2 degrade Smad proteins through ubiquitination. Intriguingly, Smurf1 interacts with Nedd8 and its E2 enzyme, Ubc12, and is activated by Neddylation. It is critical for tumor-promoting role of Smurf1 [109]. The ubiquitin–proteasome system is considered as one of the targets for the treatment of human malignancies. A specific inhibitor against Nedd8-activating enzyme (NAE)—an essential component of the Nedd8 conjugation—was reported to be effective for cancer treatment [110]. Through an indirect mechanism, the inhibition of Neddylation specifically inhibits ubiquitination by CRLs, in turn inhibiting the proliferation of cancer cells. The use of this inhibitor or related compounds would clarify the relationship between protein sorting to sEVs [110]. In this context, bacterial infection was shown to inhibit Neddylation in the host cells [111]. Specifically, effector proteins from enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC) deaminated the glutamine residues of Nedd8 and thus inhibited the activity of Neddylated Cullin–RING E3 ubiquitin ligase [112, 113]. Neddylation has also been implicated in neurodegenerative diseases such as Huntington’s disease, a form of neuronal toxicity caused by expanded CAG repeats in the gene encoding Huntingtin (HTT). Overexpression of negative regulator of ubiquitin-like protein 1 (NUB1) reduced the expression of mutant HTT in neuronal models and rescued mHTT-induced death. This function of NUB1 was found to require polyubiquitination and proteasomal degradation via Nedd8-induced Cullin activity [114].

Currently, the mechanism by which Nedd8 regulates protein sorting to sEVs by Nedd8 remains unexplored (Table 1). p53 is a multifunctional protein best known for its major functions of cell-cycle arrest and tumor suppression. However, p53 is also known to regulate the expression of critical genes associated with the endosomal compartment and exosome secretion [115]. Intriguingly, p53 is regulated by modification by ubiquitin, Nedd8, SUMO, and FAT10 [116, 117]. Therefore, Neddylation, the process by which Nedd8 is conjugated to target proteins, may be associated with the sorting of sEVs. As mentioned in the previous section, a subset of proteins in sEVs could be regulated by ubiquitination. Like ubiquitin, Nedd8 has also been detected in sEV [95]. Furthermore, Neddylation is important in the activity of CRLs, and CRLs are the largest family of E3 ligases in humans [106]. Further studies are needed to elucidate the relationship between Neddylation and sEV sorting.

SUMOylation and sorting to sEVs

SUMO was first identified by four independent groups as a molecule having a ubiquitin-like structure [118–121]. SUMOylation, a PTM by SUMO, has subsequently been reported to have fundamental functions such as protein stabilisation, nuclear–cytoplasmic transport and transcriptional regulation.

In interneuronal propagation of Parkinson’s disease [122–124], extracellular α-Synuclein has been accumulated and can be isolated from extracellular vesicles in cell culture media from human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells [125–127]. SUMOylation inhibits the aggregation and toxicity of α-Synuclein [128]. Using SUMOylation-deficient α-Synuclein mutants, the siRNA of the E2 conjugating enzyme Ubc9 and the conjugation-deficient SUMO mutant (SUMO-2ΔGG), it was shown that SUMOylation regulated α-Synuclein sorting to sEVs. Intriguingly, it was also shown that fusion with the N-terminus of SUMO2 increased α-Synuclein sorting to sEVs [129].

While sEVs are known to propagate proteins as well as miRNA, the sorting mechanism of miRNA is not fully understood. To investigate the mechanism of RNA sorting to sEVs, miRNA was purified from sEVs and a microarray and multiple alignment analyses were performed. A common RNA motif sequences (EXOmotifs: such as GGAG) that controls their localisation into sEVs were identified [130]. The heterogenous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A2B1 (hnRNP2B1) specifically binds miRNA in sEVs via the motif, thereby controlling their sorting to sEVs. It is noteworthy that hnRNPA2B1 in sEVs is SUMOylated, and SUMOylation controls the binding of hnRNPA2B1 to miRNAs. Thus, miRNA sorting is indirectly controlled by SUMOylation through hnRNP, making SUMOylation an important process in the sorting of RNA-binding proteins to sEVs as well as miRNA.

As ubiquitin and SUMO covalently modify the same lysine residues in the target proteins, the processes of ubiquitination and SUMOylation converge and cross communicate [131] in an antagonistic, synergistic, or differential manner. For example, the ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis of IκB (inhibitor of NF-κB) leads to the activation of NF-κB. SUMO targets the same lysine 21 residue of IκB as ubiquitin, and protects from proteasomal degradation of IκB, resulting in blocking activation of NF-κB [132]. In contrast, SUMOylation signals the recruitment of E3 ubiquitin ligases, resulting in the E3 ubiquitination and proteasome-mediated degradation of the target protein such as RNF4 [133]. Comprehensive proteomics analyses have revealed that SUMOylated lysine residues are also targeted for modification by ubiquitination, acetylation or methylation [134]. Furthermore, hybrid SUMO–ubiquitin chains and their receptors reflect the functional connection between ubiquitination and SUMOylation [135], suggesting strongly that SUMOylation can regulate protein sorting through MVBs by controlling ubiquitination. Future studies are expected to elucidate cross communication between ubiquitination and SUMOylation and the mechanism of protein sorting to sEV.

ISG15 and the release of sEVs

In 1979, interferon (IFN)-stimulated gene 15 (ISG15) was identified as a ubiquitin-like protein induced by interferon [136]. Notably, the expression of ISG15 blocks the process of virus budding from cells via ESCRT machinery [137]. ISG15, which contains two UBL domains, plays dual roles in the processes of a secretion and PTM. Regarding the latter, ISG15-mediated modification, or ISGylation, is important for innate immunity, particularly against viral infection. ISG15, like ubiquitin, is covalently conjugated to lysine residues of target proteins. This ISG15 modification (ISGylation) utilises UBE1L(UBA7) as an E1 enzyme, UbcH8 as an E2 enzyme and several ubiquitin E3 ligases—such as EFP and HERC5—as E3 enzymes.

For the following three reasons, the relationship between ISGylation and sEVs was analysed: (1) the release of virus and exosomes shares a common molecular mechanism; (2) TSG101, a central component of ESCRT-1, is included in sEVs, and (3) TSG101 is one of targets for ISGylation. An analysis of ISG15-knockout mice and mice expressing the enzymatically inactive form of de-ISGylase USP18 revealed that the numbers of MVBs and the release of sEVs were negatively regulated by ISGylation. Moreover, the conjugation of ISG15 to TSG101 was found to be sufficient to inhibit the release of sEVs [138].

Autophagy and the release of sEVs

Macroautophagy is the cellular process by which constituents within cells—such as proteins and organelles—are degraded. This process is essential for cell survival during starvation. Seminal genetic studies using budding yeasts by Osumi et al. in the early 1990s uncovered many of the molecules involved in autophagy [139]. Autophagy influences progression of various diseases, such as cancer, neurodegeneration, heart failure, and infectious diseases [140–142]. During the processes of autophagy, cytoplasmic cargo is enveloped within a double-membrane vesicle known as an autophagosome. Autophagosomes are translocated to and fuse with lysosomes, resulting in complete degradation of the sequestered cytoplasmic components by lysosomal hydrolases [143, 144].

The formation of autophagosomes also involves UBLs. One of the UBLs, ATG12, that is required for macroautophagy, is activated by the E1-like enzyme ATG7, transferred to the E2-like conjugating enzyme ATG10 and ultimately attached to ATG5 [145–147]. Another UBL, LC3 (ATG8), is conjugated to the lipid phosphatidylethanolamine by ATG7 and the E2-like enzyme ATG3. ATG3 was recently identified as an additional target of ATG12 [148]. The physiological significance of the interaction between ATG12 and ATG3 was analysed [149]. Studies of Atg3−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts transfected with wild-type ATG3 and a K243R-mutant form which cannot be conjugated to ATG12 revealed the accumulation of enlarged MVBs in cells lacking the ATG12–ATG3 interaction. Furthermore, a decrease in total protein levels in sEVs and specific exosomal marker proteins (Alix, TSG101, and HSC70) in sEVs purified from cells transfected with the ATG3 K243R mutant was found. Interestingly, the study identified Alix as an interaction molecule for ATG12–ATG3. Alix was previously identified in the processes of MVB distribution, exosome biogenesis and viral budding [45, 150–153], and the loss of ATG12–ATG3 conjugation was shown to phenocopy a loss of Alix.

Prion protein (PRNP) is a glycoprotein that attaches to the cell membrane through a glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor. Its abnormal form (PrPSc) is associated with the generation of prions, and its infection is known to cause transmissible spongiform encephalopathies [154]. The PRNP and PrPSc are also secreted extracellularly as sEVs [13, 14]. One study demonstrated a lower level of secreted sEVs purified from primary cultured cells of prnp-null mice than from wild-type cells. Conversely, the secretion levels of sEVs purified from primary culture cells from mice overexpressing PRNP were higher than those from wild-type mice. These prnp-null astrocytes exhibited reduced MVB formation and increased autophagosome formation, confirming that macroautophagy/autophagy inhibition via BECN1 depletion re-established the release of sEVs in these cells. Using mutants of PRNP, they also demonstrated that the octapeptide repeat domain of RPNP is important both for attenuating autophagic flux and for facilitating the secretion of sEVs [155].

Another study demonstrated that the deletion of the membrane raft protein caveolin-1 (Cav-1) increased the basal and starvation-induced formation of ATG12–ATG5 and autophagy [156]. Cav-1 interacts with ATG5 and ATG12 to activate the ATG12–ATG5 complex. Since Cav-1 is reported to interact with the octapeptide repeat domain of PRNP [157, 158], the relationship between PRNP and Cav-1 was examined, and Cav-1 was found to be arrested in lipid rafts in the absence of PRNP.

Taken together, these reports suggest that autophagy formation and the release of sEVs are closely regulated by a ubiquitin-like protein ATG12.

Autophagy, which generally leads to the bulk degradation of cytoplasm, is non-selective. In contrast, different forms of autophagy—known as selective autophagy—have been identified and characterised as removing aggregation-prone protein and unnecessary organelles, including protein aggregates (aggrephagy), mitochondria (mitophagy), peroxisomes (pexophagy), ribosomes (ribophagy), and intracellular pathogens (xenophagy). Interestingly, ubiquitin is also a hallmark of selective autophagy [144, 159]. In summary, although the autophagy pathway has been well characterised as a degradation system of both cytoplasmic and extracellular pathogens, it also regulates the release of sEVs. Autophagy and autophagy-related responses have important implications for various forms of human pathology. The precise mechanism by which autophagy regulates sEV biogenesis and release remains to be determined.

Identification of a novel PTM and protein sorting by UBL3

A bioinformatics method to identify a novel and crucial PTM factor was performed. All UBL protein sequences for various species such as of yeasts, worms, flies, mice, and humans from the GenBank genome database were extracted and a phylogenetic tree to identify highly conserved UBLs was generated. In addition to ubiquitin, SUMO and Nedd8, ubiquitin-like 3(UBL3)/membrane-anchored Ub-fold protein (MUB) was found to be one of the highly conserved UBLs [32].

UBL3 mRNA was identified as one of 2064 housekeeping genes in various human tissues [160]. UBL3 gene was identified as part of a seven-gene signature predicting relapse and survival for early stage cervical carcinoma patients [161]. UBL3 is also identified as one of three novel loci associated with BRCAX, which refers to breast cancers occurring with a family history predictive of having a BRCA1/2 mutation, but in which BRCA1/2 genetic screening has failed to reveal a causal mutation, by the genome-wide association study (GWAS) [162]. UBL3 contains a UBL domain and is an evolutionarily conserved prenylated membrane-localised protein [163]. UBL3/MUB is reported to interact non-covalently with Arabidopsis group VI ubiquitin-conjugating E2 enzymes (related to HsUbe2D and ScUbc4/5) in vitro and blocks E2 activation and E2-ubiquitin formation by tethering to the plasma membrane [164, 165]. However, whether UBL3 acts as a UBL PTM factor is not known.

Our recent report showed that UBL3 acted as a novel PTM factor—different from conventional ubiquitin and other UBL proteins [32]. Two consecutive glycine residues at the carboxyl-terminus are important for modification in the ubiquitination, SUMOylation and Neddylation reactions. Modification of these proteins, covalently bound to lysine residues in target proteins through isopeptide bonding [28, 31, 166], is generally analysed in reducing conditions, since the Gly–Lys bond is resistant to reducing agents [167–169]. In the carboxyl-terminal region of UBL3, instead of GlyGly residues, CysCys (CC) residues are found. Through cysteine residues, UBL3 modified target proteins by disulfide bonding; therefore, UBL3 modification is unique and completely different from conventional ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like modifications.

To investigate the functional role of UBL3, we performed co-staining of UBL3 with various intracellular organelle markers and found that UBL3 shows strong co-localisation with CD63, which is an MVB marker, compared with other intracellular organelles [32].

MVBs either fuse with the plasma membrane for release as exosomes, or fuse with lysosomes, which degrade the MVB contents [3, 33]. UBL3 colocalised with MVBs more than with lysosomes, and was enriched in sEVs (Fig. 2). The total protein levels in serum sEVs purified from Ubl3 KO mice were 60% lower than those from wild-type mice. We also found that UBL3 modification is required for its MVB localisation and sorting to sEVs. The precise location of UBL3 modification in the cell and the mechanism, whereby UBL3 is sorted to the MVB remain to be determined. These questions will be answered by identifying and analysing the enzyme complex involved in UBL3 modification.

Fig. 2.

Protein sorting to small extracellular vesicles (sEVs) via ubiquitin-like protein 3 (UBL3) modification. UBL3 is a novel post-translational modification factor, specifically localised in MVB, and released in sEVs. Of the 1241 UBL3-interacting proteins identified through a comprehensive proteomics analysis, 29% were annotated as ‘extracellular vesicular exosomes’. The sorting of UBL3 target proteins is enhanced by UBL3 modification [32]

Comprehensive proteomics analysis for UBL3 interacting proteins

UBL3 modification is involved in protein sorting to sEVs. Therefore, it is important to identify proteins modified and sorted by UBL3. We performed comprehensive proteomics analysis to identify UBL3 binding proteins. We identified 1241 proteins as UBL3-interacting proteins depending on C-terminal cysteine residues and UBL3 modification. We then categorised the UBL3-interacting proteins based on their subcellular localisation as defined by the gene ontology cellular components. Among these proteins, 29% of them were annotated as extracellular vesicular exosomes. We also found that more than 20 disease-related molecules such as Ras, mTOR, NOTCH, and PSEN1 were included as UBL3-interacting proteins. We examined whether UBL3-interacting proteins could be sorted to sEVs via UBL3 modification. We selected tubulin and Ras proto-oncogene as model cases, since they are reported to be present in sEVs [2, 170, 171]. Both tubulin and Ras to be directly modified by UBL3 and their sorting to sEVs to be increased by UBL3 modification. Furthermore, we found that the constitutively active oncogenic RasG12V mutant was modified by UBL3 and its sorting to sEVs was enhanced by UBL3. We also found increased sorting of RasG12V to sEVs by UBL3 modification to enhance the activation of Ras signaling in the recipient cells [32]. These results suggest that, by sEVs-mediated cell-to-cell communication, increased sorting of RasG12V in sEVs maintains its enzymatic activity and increased Ras signaling in the recipient cells. The inhibition or activation of UBL3 modification could be a therapeutic target of human diseases.

Ubiquitin, SUMO, and UBL3 are useful as tags for protein delivery to sEVs

We then attempted, since UBL3 is sorted to sEVs, to determine whether UBL3 serves as a useful tag for protein delivery to sEVs. Researchers previously identified ubiquitin and SUMOs as useful tags for the delivery of proteins to exosomes [16, 74, 129]. We fused GFP with the N-terminus of either ubiquitin, SUMOs, or UBL3 and analysed their localisation. We clearly identified UBL3-tagged GFP in MVBs. We evaluated the amount of GFP in sEVs. When we compared the level of UBL3-tagged GFP with those of GFP tagged with other UBLs, the latter levels seemed fairly weak [32]. As a new third choice, we propose that UBL3 is also very useful as a sorting tag to sEVs [32]. When UBL3 was fused to other proteins such as biotinylated protein, UBL3 fusion protein was also enriched in sEVs. Since released sEVs from one cell are taken up by other cells for cell-to-cell communication, UBL3-tagging provides a novel attractive strategy as a new drug delivery vehicle.

Other UBLs and their roles

Fat10

FAT10 (HLA-F adjacent transcript 10), which is encoded in the MHC gene complex, contains two tandem UBL domains and is also known as diubiquitin or ubiquitin D. FAT10 is expressed in B cells and dendritic cells, and its expression is upregulated in response to IFNγ and TNFα [172–174]. Like ubiquitin, FAT10 contains a carboxyl-terminal GlyGly motif and modifies its target via FAT10ylation, whereby FAT10 is conjugated to its target substrate via the bispecific E1 activating enzyme ubiquitin-like modifier activating enzyme 6 (UBA6) and the similarly bispecific E2 conjugating enzyme UBA6-specific E2 enzyme 1 (USE1). The E3 ligases involved in this process have not been determined [175]. Interestingly, the conjugation of USE1 and the ubiquitin-activating enzyme UBE2 with FAT10 led to the proteasomal degradation. FAT10 gene-deleted mice exhibit a greater tendency toward lymphocytes apoptosis and enhanced sensitivity to endotoxin challenge [176]. These findings suggest that although FAT10ylation is ubiquitin-independent, FAT10 plays a regulatory role in the ubiquitin–conjugation pathway [173, 177]. Notably, p53 is regulated by modification not only by Neddylation, but also by FAT10ylation [116, 117]; the latter modification enhances the transcriptional activity of p53 [117]. p53 is also known to regulate sEV secretion [115]. Therefore, FAT10ylation may regulate sEV secretion via p53 and could regulate sorting indirectly by regulating the ubiquitin pathway.

Ufm1

Ubiquitin-fold modifier 1 (Ufm1) is responsible for a PTM known as ufmylation [178]. Although Ufm1 shows no clear overall sequence identity with ubiquitin or other modifiers, the tertiary structure of this protein shows striking similarity to ubiquitin and includes a ubiquitin-like fold [178]. Whereas ubiquitin, SUMO and Nedd8 contain GlyGly residues, Ufm1 contains a single Gly residue due to protease cleavage at its carboxyl-terminus. Ufm1 binds covalently to target proteins via E1-activating enzyme (UBA5), E2-conjugating enzyme (UFC1), and E3-ligase Ufl1 [179]. Ufmylation is indispensable for erythropoiesis and megakaryopoiesis [180], as indicated by the death of UBA5-deficient mice in utero due to severe anemia. Red blood cells and platelets derived from megakaryocytes are essential sources of sEVs/exosomes in the blood [177, 181]. Accordingly, ufmylation is important for the production for exosomes from erythrocytes and platelets via haematopoiesis. However, it remains unknown whether ufmylation is involved in the release of sEVs through MVBs from matured erythrocytes and platelets. It is also of note that blood and plasma are used for liquid biopsy for the purpose of diagnosis and evaluation of drug efficacy [182]. miRNA and DNA in blood and plasma are considered to be derived from exosomes. Finally, recent research has revealed the importance of ufmylation in human brain development [183].

Urm1

It is known that Urm1 functions as a sulphur carrier in tRNA thiolation [184]. Like ubiquitination, urmylation results in a covalent bond between carboxyl-terminal Gly of Urm1 and Lys in the target protein. However, the carboxyl-terminus of Urm1 is converted to thiocarboxylate by the addition of sulphur [185]. Urm1 protein modification increases in an oxidative environment, and the Urm1 substrate peroxiredoxin, or Ahp1, links between urm1 pathway with oxidative stress [185, 186]. Interestingly, the deubiquitinating enzyme USP15 is also urmylated in response to oxidative stress [185]. Given that sEV cargoes are influenced by various forms of stress, urmylation might be a regulator of sEVs [187]. Like ubiquitin and its enzymes, Urm1 has been detected in sEV [95], and may be similarly involved in protein modification and the sorting of proteins to sEVs.

Hub1 (UBL5)

Homologous to ubiquitin 1 (Hub1; UBL5) belongs to a novel family of UBL proteins. Notably, the carboxyl-terminal Gly of Hub1 has been replaced by di-Tyr residues instead [188]. Accordingly, Hub1 binds non-covalently to target proteins, such as spliceosome component Snu66, and plays an important role in the recognition of noncanonical 5′ splice sites [189, 190]. Hub1 is also involved in the mitochondrial unfolded protein response (UPR), chromatin structural remodelling, and transcriptional activation [191, 192]. In humans, Fanconi anemia is a genetic disorder characterised by bone-marrow failure, cancer susceptibility, and chromosomal instability. Notably, Hub1 interacts with and stabilises FANC1, a components of the Fanconi anemia pathway [193].

MNSFβ

Monoclonal nonspecific suppressor factor β (MNSFβ) is produced as a fusion protein of ubiquitin-like protein and ribosomal protein S30. The ubiquitin-like portion is cleaved in the cytoplasm and acts as both a lymphokine secreted with MNSFα and as a modification factor. MNSFβ, also known as FUB1, covalently attaches to the lysine residues of target proteins [194, 195], such as the pro-apoptotic protein Bcl-G. Like FAT10, MNSFβ is induced by INF-γ, and is closely associated with apoptosis [194]. MNSFβ contains a conjugatable carboxyl-terminal glycine and that is used to form covalent bonds with endophilin II in macrophages. Accordingly, MNSFβ has been suggested to play a role in the regulation of phagocytosis and endocytosis [194], with an anti-inflammatory and anti-proliferative effect. Given these potential roles, MNSFβ may regulate both the secretion and uptake of sEVs.

In summary, ubiquitin and various UBLs, including SUMO, Nedd8, ISG15, ATG8, ATG12, UBL3, FAT10, Ufm1, Urm1, Hub1, and MNSFβ, are regulators of PTM and potential contributors to sEV/exosome biogenesis, secretion, and uptake. As each UBL has unique functions, future studies must elucidate the mechanisms by which the various UBLs coordinate sEV biogenesis, secretion, and cellular uptake for future studies.

Conclusion

Intercellular communication by sEVs is involved in various diseases, including cancers, metastasis, and degenerative diseases [7–13]. Currently, the four major treatments for cancer are surgical removal, radiation therapy, drug chemotherapy, and immunotherapy. Combinations of two or more treatments—known as multimodality cancer treatment—are used to improve outcomes. In this regard, the inhibition of sEVs-mediated intercellular communications has drawn considerable attention as a potential new therapeutic strategy. Inhibitors of ubiquitin-like proteins with significant roles in PTM and sEV regulation, such as ubiquitin, SUMO, ISG15, ATG12, and UBL3, may provide new therapeutic options. An understanding of the regulation of sEVs’ loading and secretion under various disease conditions is important. Particularly, various stress conditions—such as hypoxia, heat, irradiation, starvation, viral ,and/or bacterial infection or oxidative stress—can influence disease progression. Under these conditions, changes are observed in PTM by ubiquitin and related proteins. It is also of note that crosstalk and inter-regulatory mechanisms between modifications by ubiquitin/UBLs and autophagy play pivotal roles in diseases. In the case of skeletal muscle atrophy, the PI3 K–Akt–FoxO pathway has been characterised as an important regulator of muscle atrophy through Murf-1 and MAFbx/atrogin-1 [196–198]. Murf-1 and MAFbx/atrogin-1, involved in protein degradation in skeletal muscle atrophy, are characterised as indispensable components of striate muscle-specific RING-type and SCF-type E3 ligase complexes, respectively [199]. Activated FoxO stimulates lysosomal proteolysis in muscle, and also controls the expression of autophagy-related genes such as LC3 and Bnip3 [200]. FoxO, therefore, serves as an essential regulator of both the ubiquitin protease system and autophagy [201, 202]. Since autophagy is an important regulator of sEV, the mechanism of the relationship between ubiquitin and autophagy requires elucidation. Precise analyses of the crosstalk between ubiquitin and UBLs in the regulation of sEVs will not only open a new research field, but also lead to a deeper understanding of pathogenesis and the discovery of novel therapeutic options for the treatment of human diseases.

In Parkinson’s disease, α-Synuclein—the major component in Lewy bodies—is ubiquitinated by HECT-type Nedd4 ubiquitin ligase and/or SUMOylated by E3 SUMO–protein ligase PIAS2 [203, 204]. In Alzheimer’s disease, pathologically fibrillary tau accumulates in amyloid plaques [205], whereas TDP-43 accumulates and aggregates in disease foci associated with frontotemporal lobar degeneration and in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) [206, 207]. In skeletal muscle regeneration, TDP-43 also acts as an RNA-binding protein and forms cytoplasmic amyloid-like myo-granules during skeletal muscle regeneration [208]. Evidence is accumulating to show that α-Synuclein, amyloid-β, tau, prions and TDP-43 undergo PTM such as ubiquitination and phosphorylation [209, 210]. More importantly, all of these proteins have been detected in sEVs [10–14, 211, 212]. Aggregation-prone proteins are incorporated into autophagosomes, which have a spherical structure with double-layered membranes. Autophagosomes then fuse with lysosomes to degrade their contents, a process known as aggrephagy [213]. These data suggest that proteins found in aggregates in neurodegenerative diseases are sorted extracellularly as sEVs and disseminated throughout the central nervous system. Therefore, PTMs mediated by ubiquitin and/or UBLs may act as essential coordinators of sEV secretion and degradation in the process of neurodegenerative disease transmission. Whether proteins either ubiquitinated or modified by other UBLs have specialised roles in cellular signaling is not clear. Detailed analyses of each protein modified either by ubiquitin or UBLs should be required in future studies. PTM by ubiquitin and UBLs could be therapeutic targets for neurodegenerative diseases. Further research in this promising field is urgently needed (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Schematic illustration of small extracellular vesicle (sEV) sorting and secretion through multivesicular bodies (MVBs) by UBLs. UBLs (Ubiquitin, Nedd8, SUMO, ISG15, ATG12, and UBL3) are depicted as small ovals. Each UBL has various functions for the regulation of MVB formation and sEV secretion. The proteins of sEV undergo post-translational modification such as ubiquitination, SUMOylation and UBL3 modification [32, 85, 92, 95, 129, 130]. Sorting of a subset of proteins is controlled by these modifications. Compared with ubiquitin and SUMO, UBL3 is more specifically localised to MVB and enriched in sEV [32]. The formation of intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) and MVBs is also regulated by a subset of UBLs. TSG101 is modified by ISG15 [138], while Alix is interacted with ATG12-ATG3 [149]. These complexes influence the biogenesis of ILVs and MVB formation [45, 150–153]. Crosstalk between these molecules plays an important role in the regulation of MVB and extracellular secretion to sEV [36–38, 41]

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (16K08599, 18K07209, 19H05299, and 19H03427), the Ichihara International Scholarship Foundation, Kobayashi Foundation for Cancer, Ohsumi Frontier Science Foundation, and an Intramural Research Grant (26-8, 29-4) for Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders of NCNP.

Abbreviations

- sEVs

Small extracellular vesicles

- PTM

Post-translational modification

- UBLs

Ubiquitin-like proteins

- MVBs

Multivesicular bodies

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Johnstone RM, Adam M, Hammond JR, Orr L, Turbide C. Vesicle formation during reticulocyte maturation. Association of plasma membrane activities with released vesicles (exosomes) J Biol Chem. 1987;262(19):9412–9420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kowal J, Arras G, Colombo M, Jouve M, Morath JP, Primdal-Bengtson B, Dingli F, Loew D, Tkach M, Thery C. Proteomic comparison defines novel markers to characterize heterogeneous populations of extracellular vesicle subtypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113(8):E968–E977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1521230113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colombo M, Raposo G, Thery C. Biogenesis, secretion, and intercellular interactions of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2014;30:255–289. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-101512-122326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valadi H, Ekstrom K, Bossios A, Sjostrand M, Lee JJ, Lotvall JO. Exosome- mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9(6):654–659. doi: 10.1038/ncb1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raposo G, Stoorvogel W. Extracellular vesicles: exosomes, microvesicles, and friends. J Cell Biol. 2013;200(4):373–383. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201211138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takahashi A, Okada R, Nagao K, Kawamata Y, Hanyu A, Yoshimoto S, Takasugi M, Watanabe S, Kanemaki MT, Obuse C, Hara E. Exosomes maintain cellular homeostasis by excreting harmful DNA from cells. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15287. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoshino A, Costa-Silva B, Shen TL, Rodrigues G, Hashimoto A, Tesic Mark M, Molina H, Kohsaka S, Di Giannatale A, Ceder S, Singh S, Williams C, Soplop N, Uryu K, Pharmer L, King T, Bojmar L, Davies AE, Ararso Y, Zhang T, Zhang H, Hernandez J, Weiss JM, Dumont-Cole VD, Kramer K, Wexler LH, Narendran A, Schwartz GK, Healey JH, Sandstrom P, Labori KJ, Kure EH, Grandgenett PM, Hollingsworth MA, de Sousa M, Kaur S, Jain M, Mallya K, Batra SK, Jarnagin WR, Brady MS, Fodstad O, Muller V, Pantel K, Minn AJ, Bissell MJ, Garcia BA, Kang Y, Rajasekhar VK, Ghajar CM, Matei I, Peinado H, Bromberg J, Lyden D. Tumour exosome integrins determine organotropic metastasis. Nature. 2015;527(7578):329–335. doi: 10.1038/nature15756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Nedawi K, Meehan B, Micallef J, Lhotak V, May L, Guha A, Rak J. Intercellular transfer of the oncogenic receptor EGFRvIII by microvesicles derived from tumour cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10(5):619–624. doi: 10.1038/ncb1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peinado H, Aleckovic M, Lavotshkin S, Matei I, Costa-Silva B, Moreno-Bueno G, Hergueta-Redondo M, Williams C, Garcia-Santos G, Ghajar C, Nitadori-Hoshino A, Hoffman C, Badal K, Garcia BA, Callahan MK, Yuan J, Martins VR, Skog J, Kaplan RN, Brady MS, Wolchok JD, Chapman PB, Kang Y, Bromberg J, Lyden D. Melanoma exosomes educate bone marrow progenitor cells toward a pro-metastatic phenotype through MET. Nat Med. 2012;18(6):883–891. doi: 10.1038/nm.2753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rajendran L, Honsho M, Zahn TR, Keller P, Geiger KD, Verkade P, Simons K. Alzheimer’s disease beta-amyloid peptides are released in association with exosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(30):11172–11177. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603838103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kanmert D, Cantlon A, Muratore CR, Jin M, O’Malley TT, Lee G, Young-Pearse TL, Selkoe DJ, Walsh DM. C-terminally truncated forms of Tau, but not full-length Tau or its C-terminal fragments, are released from neurons independently of cell death. J Neurosci. 2015;35(30):10851–10865. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0387-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee HJ, Bae EJ, Lee SJ. Extracellular alpha–synuclein-a novel and crucial factor in Lewy body diseases. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10(2):92–98. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2013.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fevrier B, Vilette D, Archer F, Loew D, Faigle W, Vidal M, Laude H, Raposo G. Cells release prions in association with exosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(26):9683–9688. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308413101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vella LJ, Sharples RA, Lawson VA, Masters CL, Cappai R, Hill AF. Packaging of prions into exosomes is associated with a novel pathway of PrP processing. J Pathol. 2007;211(5):582–590. doi: 10.1002/path.2145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Szabo-Taylor K, Ryan B, Osteikoetxea X, Szabo TG, Sodar B, Holub M, Nemeth A, Paloczi K, Pallinger E, Winyard P, Buzas EI. Oxidative and other posttranslational modifications in extracellular vesicle biology. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2015;40:8–16. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2015.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moreno-Gonzalo O, Fernandez-Delgado I, Sanchez-Madrid F. Post-translational add- ons mark the path in exosomal protein sorting. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2018;75(1):1–19. doi: 10.1007/s00018-017-2690-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pagano M. Cell cycle regulation by the ubiquitin pathway. FASEB J. 1997;11(13):1067–1075. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.11.13.9367342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Verma IM, Stevenson JK, Schwarz EM, Van Antwerp D, Miyamoto S. Rel/NF- kappa B/I kappa B family: intimate tales of association and dissociation. Genes Dev. 1995;9(22):2723–2735. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.22.2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hale AJ, Smith CA, Sutherland LC, Stoneman VE, Longthorne VL, Culhane AC, Williams GT. Apoptosis: molecular regulation of cell death. Eur J Biochem. 1996;236(1):1–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.00001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Naidoo N, Song W, Hunter-Ensor M, Sehgal A. A role for the proteasome in the light response of the timeless clock protein. Science. 1999;285(5434):1737–1741. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5434.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alves-Rodrigues A, Gregori L, Figueiredo-Pereira ME. Ubiquitin, cellular inclusions and their role in neurodegeneration. Trends Neurosci. 1998;21(12):516–520. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(98)01276-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang YH, Armstrong D, Albrecht U, Atkins CM, Noebels JL, Eichele G, Sweatt JD, Beaudet AL. Mutation of the Angelman ubiquitin ligase in mice causes increased cytoplasmic p53 and deficits of contextual learning and long-term potentiation. Neuron. 1998;21(4):799–811. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80596-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chain DG, Casadio A, Schacher S, Hegde AN, Valbrun M, Yamamoto N, Goldberg AL, Bartsch D, Kandel ER, Schwartz JH. Mechanisms for generating the autonomous cAMP-dependent protein kinase required for long-term facilitation in Aplysia. Neuron. 1999;22(1):147–156. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80686-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ageta H, Kato A, Hatakeyama S, Nakayama K, Isojima Y, Sugiyama H. Regulation of the level of Vesl-1S/Homer-1a proteins by ubiquitin-proteasome proteolytic systems. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(19):15893–15897. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011097200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ageta H, Kato A, Fukazawa Y, Inokuchi K, Sugiyama H. Effects of proteasome inhibitors on the synaptic localization of Vesl-1S/Homer-1a proteins. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2001;97(2):186–189. doi: 10.1016/S0169-328X(01)00303-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yao I, Takagi H, Ageta H, Kahyo T, Sato S, Hatanaka K, Fukuda Y, Chiba T, Morone N, Yuasa S, Inokuchi K, Ohtsuka T, Macgregor GR, Tanaka K, Setou M. SCRAPPER- dependent ubiquitination of active zone protein RIM1 regulates synaptic vesicle release. Cell. 2007;130(5):943–957. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haas AL, Siepmann TJ. Pathways of ubiquitin conjugation. FASEB J. 1997;11(14):1257–1268. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.11.14.9409544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Welchman RL, Gordon C, Mayer RJ. Ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like proteins as multifunctional signals. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6(8):599–609. doi: 10.1038/nrm1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang H, Takagi H, Konishi Y, Ageta H, Ikegami K, Yao I, Sato S, Hatanaka K, Inokuchi K, Seog DH, Setou M. Transmembrane and ubiquitin-like domain-containing protein 1 (Tmub1/HOPS) facilitates surface expression of GluR2-containing AMPA receptors. PLoS One. 2008;3(7):e2809. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson ES. Protein modification by SUMO. Annu Rev Biochem. 2004;73:355–382. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.074118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watson IR, Irwin MS, Ohh M. NEDD8 pathways in cancer, Sine Quibus Non. Cancer Cell. 2011;19(2):168–176. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ageta H, Ageta-Ishihara N, Hitachi K, Karayel O, Onouchi T, Yamaguchi H, Kahyo T, Hatanaka K, Ikegami K, Yoshioka Y, Nakamura K, Kosaka N, Nakatani M, Uezumi A, Ide T, Tsutsumi Y, Sugimura H, Kinoshita M, Ochiya T, Mann M, Setou M, Tsuchida K. UBL3 modification influences protein sorting to small extracellular vesicles. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):3936. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06197-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Katzmann DJ, Odorizzi G, Emr SD. Receptor downregulation and multivesicular- body sorting. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3(12):893–905. doi: 10.1038/nrm973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zerial M, McBride H. Rab proteins as membrane organizers. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2(2):107–117. doi: 10.1038/35052055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seabra MC, Mules EH, Hume AN. Rab GTPases, intracellular traffic and disease. Trends Mol Med. 2002;8(1):23–30. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4914(01)02227-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Savina A, Fader CM, Damiani MT, Colombo MI. Rab11 promotes docking and fusion of multivesicular bodies in a calcium-dependent manner. Traffic. 2005;6(2):131–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2004.00257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hsu C, Morohashi Y, Yoshimura S, Manrique-Hoyos N, Jung S, Lauterbach MA, Bakhti M, Gronborg M, Mobius W, Rhee J, Barr FA, Simons M. Regulation of exosome secretion by Rab35 and its GTPase-activating proteins TBC1D10A-C. J Cell Biol. 2010;189(2):223–232. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200911018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ostrowski M, Carmo NB, Krumeich S, Fanget I, Raposo G, Savina A, Moita CF, Schauer K, Hume AN, Freitas RP, Goud B, Benaroch P, Hacohen N, Fukuda M, Desnos C, Seabra MC, Darchen F, Amigorena S, Moita LF, Thery C. Rab27a and Rab27b control different steps of the exosome secretion pathway. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12(1):19–30. doi: 10.1038/ncb2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kirkbride KC, Sung BH, Sinha S, Weaver AM. Cortactin: a multifunctional regulator of cellular invasiveness. Cell Adhes Migr. 2011;5(2):187–198. doi: 10.4161/cam.5.2.14773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Daly RJ. Cortactin signalling and dynamic actin networks. Biochem J. 2004;382(Pt 1):13–25. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sinha S, Hoshino D, Hong NH, Kirkbride KC, Grega-Larson NE, Seiki M, Tyska MJ, Weaver AM. Cortactin promotes exosome secretion by controlling branched actin dynamics. J Cell Biol. 2016;214(2):197–213. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201601025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Henne WM, Buchkovich NJ, Emr SD. The ESCRT pathway. Dev Cell. 2011;21(1):77–91. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roxrud I, Stenmark H, Malerod L. ESCRT & Co. Biol Cell. 2010;102(5):293–318. doi: 10.1042/bc20090161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Colombo M, Moita C, van Niel G, Kowal J, Vigneron J, Benaroch P, Manel N, Moita LF, Thery C, Raposo G. Analysis of ESCRT functions in exosome biogenesis, composition and secretion highlights the heterogeneity of extracellular vesicles. J Cell Sci. 2013;126(Pt 24):5553–5565. doi: 10.1242/jcs.128868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baietti MF, Zhang Z, Mortier E, Melchior A, Degeest G, Geeraerts A, Ivarsson Y, Depoortere F, Coomans C, Vermeiren E, Zimmermann P, David G. Syndecan- syntenin-ALIX regulates the biogenesis of exosomes. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14(7):677–685. doi: 10.1038/ncb2502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lambaerts K, Van Dyck S, Mortier E, Ivarsson Y, Degeest G, Luyten A, Vermeiren E, Peers B, David G, Zimmermann P. Syntenin, a syndecan adaptor and an Arf6 phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate effector, is essential for epiboly and gastrulation cell movements in zebrafish. J Cell Sci. 2012;125(Pt 5):1129–1140. doi: 10.1242/jcs.089987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ghossoub R, Lembo F, Rubio A, Gaillard CB, Bouchet J, Vitale N, Slavik J, Machala M, Zimmermann P. Syntenin-ALIX exosome biogenesis and budding into multivesicular bodies are controlled by ARF6 and PLD2. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3477. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stuffers S, Sem Wegner C, Stenmark H, Brech A. Multivesicular endosome biogenesis in the absence of ESCRTs. Traffic. 2009;10(7):925–937. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.00920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Trajkovic K, Hsu C, Chiantia S, Rajendran L, Wenzel D, Wieland F, Schwille P, Brugger B, Simons M. Ceramide triggers budding of exosome vesicles into multivesicular endosomes. Science. 2008;319(5867):1244–1247. doi: 10.1126/science.1153124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Theos AC, Truschel ST, Tenza D, Hurbain I, Harper DC, Berson JF, Thomas PC, Raposo G, Marks MS. A lumenal domain-dependent pathway for sorting to intralumenal vesicles of multivesicular endosomes involved in organelle morphogenesis. Dev Cell. 2006;10(3):343–354. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.van Niel G, Charrin S, Simoes S, Romao M, Rochin L, Saftig P, Marks MS, Rubinstein E, Raposo G. The tetraspanin CD63 regulates ESCRT-independent and -dependent endosomal sorting during melanogenesis. Dev Cell. 2011;21(4):708–721. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chairoungdua A, Smith DL, Pochard P, Hull M, Caplan MJ. Exosome release of beta-catenin: a novel mechanism that antagonizes Wnt signaling. J Cell Biol. 2010;190(6):1079–1091. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201002049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yu H, Matouschek A. Recognition of client proteins by the proteasome. Annu Rev Biophys. 2017;46:149–173. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-070816-033719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Williams RL, Urbe S. The emerging shape of the ESCRT machinery. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8(5):355–368. doi: 10.1038/nrm2162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Escrevente C, Keller S, Altevogt P, Costa J. Interaction and uptake of exosomes by ovarian cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:108. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tian T, Zhu YL, Zhou YY, Liang GF, Wang YY, Hu FH, Xiao ZD. Exosome uptake through clathrin-mediated endocytosis and macropinocytosis and mediating miR-21 delivery. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(32):22258–22267. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.588046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nakase I, Kobayashi NB, Takatani-Nakase T, Yoshida T. Active macropinocytosis induction by stimulation of epidermal growth factor receptor and oncogenic Ras expression potentiates cellular uptake efficacy of exosomes. Sci Rep. 2015;5:10300. doi: 10.1038/srep10300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Feng D, Zhao WL, Ye YY, Bai XC, Liu RQ, Chang LF, Zhou Q, Sui SF. Cellular internalization of exosomes occurs through phagocytosis. Traffic. 2010;11(5):675–687. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2010.01041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Svensson KJ, Christianson HC, Wittrup A, Bourseau-Guilmain E, Lindqvist E, Svensson LM, Morgelin M, Belting M. Exosome uptake depends on ERK1/2-heat shock protein 27 signaling and lipid Raft-mediated endocytosis negatively regulated by caveolin-1. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(24):17713–17724. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.445403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Laulagnier K, Javalet C, Hemming FJ, Chivet M, Lachenal G, Blot B, Chatellard C, Sadoul R. Amyloid precursor protein products concentrate in a subset of exosomes specifically endocytosed by neurons. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2018;75(4):757–773. doi: 10.1007/s00018-017-2664-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kamerkar S, LeBleu VS, Sugimoto H, Yang S, Ruivo CF, Melo SA, Lee JJ, Kalluri R. Exosomes facilitate therapeutic targeting of oncogenic KRAS in pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2017;546(7659):498–503. doi: 10.1038/nature22341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Akishiba M, Takeuchi T, Kawaguchi Y, Sakamoto K, Yu HH, Nakase I, Takatani-Nakase T, Madani F, Graslund A, Futaki S. Cytosolic antibody delivery by lipid-sensitive endosomolytic peptide. Nat Chem. 2017;9(8):751–761. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li W, Bengtson MH, Ulbrich A, Matsuda A, Reddy VA, Orth A, Chanda SK, Batalov S, Joazeiro CA. Genome-wide and functional annotation of human E3 ubiquitin ligases identifies MULAN, a mitochondrial E3 that regulates the organelle’s dynamics and signaling. PLoS One. 2008;3(1):e1487. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Berndsen CE, Wolberger C. New insights into ubiquitin E3 ligase mechanism. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2014;21(4):301–307. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Metzger MB, Hristova VA, Weissman AM. HECT and RING finger families of E3 ubiquitin ligases at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2012;125(Pt 3):531–537. doi: 10.1242/jcs.091777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Winberg G, Matskova L, Chen F, Plant P, Rotin D, Gish G, Ingham R, Ernberg I, Pawson T. Latent membrane protein 2A of Epstein-Barr virus binds WW domain E3 protein- ubiquitin ligases that ubiquitinate B-cell tyrosine kinases. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20(22):8526–8535. doi: 10.1128/MCB.20.22.8526-8535.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ikeda M, Ikeda A, Longan LC, Longnecker R. The Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 2A PY motif recruits WW domain-containing ubiquitin-protein ligases. Virology. 2000;268(1):178–191. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.0166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ikeda M, Ikeda A, Longnecker R. PY motifs of Epstein-Barr virus LMP2A regulate protein stability and phosphorylation of LMP2A-associated proteins. J Virol. 2001;75(12):5711–5718. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.12.5711-5718.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ikeda M, Longnecker R. Cholesterol is critical for Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 2A trafficking and protein stability. Virology. 2007;360(2):461–468. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.10.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Putz U, Howitt J, Lackovic J, Foot N, Kumar S, Silke J, Tan SS. Nedd4 family- interacting protein 1 (Ndfip1) is required for the exosomal secretion of Nedd4 family proteins. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(47):32621–32627. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804120200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sette P, Jadwin JA, Dussupt V, Bello NF, Bouamr F. The ESCRT-associated protein Alix recruits the ubiquitin ligase Nedd4-1 to facilitate HIV-1 release through the LYPXnL L domain motif. J Virol. 2010;84(16):8181–8192. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00634-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kikonyogo A, Bouamr F, Vana ML, Xiang Y, Aiyar A, Carter C, Leis J. Proteins related to the Nedd4 family of ubiquitin protein ligases interact with the L domain of Rous sarcoma virus and are required for gag budding from cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(20):11199–11204. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201268998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Staub O, Dho S, Henry P, Correa J, Ishikawa T, McGlade J, Rotin D. WW domains of Nedd4 bind to the proline-rich PY motifs in the epithelial Na + channel deleted in Liddle’s syndrome. EMBO J. 1996;15(10):2371–2380. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1996.tb00593.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sterzenbach U, Putz U, Low LH, Silke J, Tan SS, Howitt J. Engineered exosomes as vehicles for biologically active proteins. Mol Ther. 2017;25(6):1269–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Okamoto K, Kondo-Okamoto N, Ohsumi Y. Mitochondria-anchored receptor Atg32 mediates degradation of mitochondria via selective autophagy. Dev Cell. 2009;17(1):87–97. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nguyen TN, Padman BS, Lazarou M. Deciphering the molecular signals of PINK1/Parkin mitophagy. Trends Cell Biol. 2016;26(10):733–744. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2016.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Song P, Trajkovic K, Tsunemi T, Krainc D. Parkin modulates endosomal organization and function of the endo-lysosomal pathway. J Neurosci. 2016;36(8):2425–2437. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2569-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pisitkun T, Shen RF, Knepper MA. Identification and proteomic profiling of exosomes in human urine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(36):13368–13373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403453101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Buschow SI, Liefhebber JM, Wubbolts R, Stoorvogel W. Exosomes contain ubiquitinated proteins. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2005;35(3):398–403. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Andreola G, Rivoltini L, Castelli C, Huber V, Perego P, Deho P, Squarcina P, Accornero P, Lozupone F, Lugini L, Stringaro A, Molinari A, Arancia G, Gentile M, Parmiani G, Fais S. Induction of lymphocyte apoptosis by tumor cell secretion of FasL-bearing microvesicles. J Exp Med. 2002;195(10):1303–1316. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]