Abstract

The actin-related protein complex 2/3 (Arp2/3) generates branched actin networks important for many cellular processes such as motility, vesicular trafficking, cytokinesis, and intercellular junction formation and stabilization. Activation of Arp2/3 requires interaction with actin nucleation-promoting factors (NPFs). Regulation of Arp2/3 activity is achieved by endogenous inhibitory proteins through direct binding to Arp2/3 and competition with NPFs or by binding to Arp2/3-induced actin filaments and disassembly of branched actin networks. Arp2/3 inhibition has recently garnered more attention as it has been associated with attenuation of cancer progression, neurotoxic effects during drug abuse, and pathogen invasion of host cells. In this review, we summarize current knowledge on expression, inhibitory mechanisms and function of endogenous proteins able to inhibit Arp2/3 such as coronins, GMFs, PICK1, gadkin, and arpin. Moreover, we discuss cellular consequences of pharmacological Arp2/3 inhibition.

Keywords: Actin cytoskeleton, Adhesion, Migration, Cortactin, Vesicle trafficking, Endosome, Cofilin, CK666

Introduction

All cells have the capacity to respond quickly to environmental stimuli, and such responses in most cases require actin cytoskeletal remodeling. The machinery of actin-binding proteins and signaling molecules that control actin dynamics is vast, diverse and regulates processes such as actin filament growth, severing, cross-linking and branching [1]. The formation of branched actin networks is critical for many cell functions including adhesion, migration, and vesicular transport. Actin branching is regulated by a heptameric protein complex termed Arp2/3 due to its two main components actin-related proteins (Arp) 2 and 3 that serve as nucleus to establish growth of daughter filaments on existing actin filaments in a typical ~ 70° angle [2]. The Arp2/3 complex was the first actin nucleator identified in eukaryotic cells and is highly conserved among species [3]. Recently, alternative Arp2/3 complexes have been identified that are composed of different subunits and mediate distinct cell functions [4, 5]. The importance of Arp2/3 is highlighted by the fact that deficiency of subunits is lethal [6, 7]. Arp2/3 has an intrinsically low activity with a conformation in which the Arp2 and Arp3 subunits are separated from each other. Activation is achieved via nucleation-promoting factors (NPFs) that induce a conformational change bringing Arp2 and Arp3 into close proximity. NPFs functions have been excellently reviewed elsewhere [8]. Many NPFs share a consensus acidic WCA (W, WASP-homology-2; C, Connector; A, Acidic) domain in their C-terminus enabling them to bind monomeric, globular (G)-actin and Arp2/3. Binding of NPFs to Arp2/3 thus also provides G-actin for the growth of the daughter filament. Arp2/3 activity is regulated by many inhibitory proteins to guarantee spatiotemporal control of branched actin formation. Of note, some of these inhibitory proteins also have a C-terminal acidic domain similar to NPFs that allows for competition with NPFs for Arp2/3 binding sites. An emerging concept is that certain NPFs in given subcellular structures have their inhibitory counterpart to establish strict control of Arp2/3 activity in a compartmentalized fashion [9]. Whereas NPFs have been studied extensively, proteins inhibiting Arp2/3 (PIA) are now drawing more attention, and their cell functions have recently been investigated in more detail. Strict regulation of Arp2/3 activity is of utmost physiological importance as uncontrolled overactivation, for example, has been related to the progression of many cancer types [9]. In this review, we summarize current knowledge on PIA and how they affect cell biological and pathophysiological processes. Moreover, we discuss pharmacological Arp2/3 inhibitors, their effects on Arp2/3-mediated cell functions, and their therapeutic potential.

Endogenous inhibition of Arp2/3

Endogenous Arp2/3 inhibition is achieved by different classes of proteins: (1) proteins that indirectly inhibit Arp2/3 by binding to actin filaments, thus preventing the binding of Arp2/3 to F-actin as part of the physiological cycle of Arp2/3 activation; (2) proteins that sequester Arp2/3; and (3) proteins that directly inhibit Arp2/3 via binding to Arp2/3 and preventing NPF-induced Arp2/3 activation to correctly balance Arp2/3 activity. Of note, some PIA such as glia maturation factors (GMFs) can compete with NPFs and induce debranching. We will discuss each of these proteins separately below, and the information is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of PIA: expression profiles, cell functions and inhibitory mechanisms

| PIA | Cell type and tissue expression | Function | Inhibiting mechanism | Antagonism of NPFs | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coronin 1A | Hematopoietic cells | Cell migration and activation | Binding to subunits Arp2 and Arp3 | No | [10–13, 18, 19] |

|

Coronin 1B Coronin 1C Coronin 2A |

Ubiquitous | Lamellipodial dynamics, motility, migration, adhesion | |||

| Coronin 2B | Nervous system | ? | |||

| GMFβ | Ubiquitous, enriched in brain | Chemotaxis, endocytosis, migration, cell adhesion and lamellipodial dynamics |

Binding to subunits Arp2 and ArpC1 Cofilin-like debranching mechanism |

Yes, VCA-WASP domain | [24–28, 31–33, 36] |

| GMFγ | Immune cells and microvascular endothelium | ||||

| Gadkin | Ovary, testes, adrenal gland, brain, spleen, pancreas, lung, liver, fat, stomach, kidney | Cell spreading, cell shape, size, migration, trafficking of clathrin- coated vesicles, transport of vesicles and mitochondria toward the cell periphery, lysosomal enzyme secretion | Intracellular Arp2/3 sequestration | Yes, VCA-N-WASP domain | [44–46] |

| PICK1 | Heart, lung, liver, skeletal muscle, kidney, enriched in brain and testes | Membrane invagination, neuronal morphology, glutamate AMPA receptor-endocytosis, dendritic spine size and spine shrinkage plasticity, insulin granule trafficking, spermiogenesis | Binding to actin and Arp2/3 | Yes, VCA-N-WASP domain | [50, 53, 55, 67, 68, 85] |

| Arpin | Brain, lung, kidney, spleen, liver, mucosa, jejunum, colon | Directional persistence and speed of migration, cell turning, cell cycle progression | Binding to Arp2 and Arp3 subunits, stabilizing the inactive state | Yes, VCA-WAVE and VCA-N-WASP domains | [89, 90, 92, 94, 95, 104] |

Indirect inhibitors

Coronins

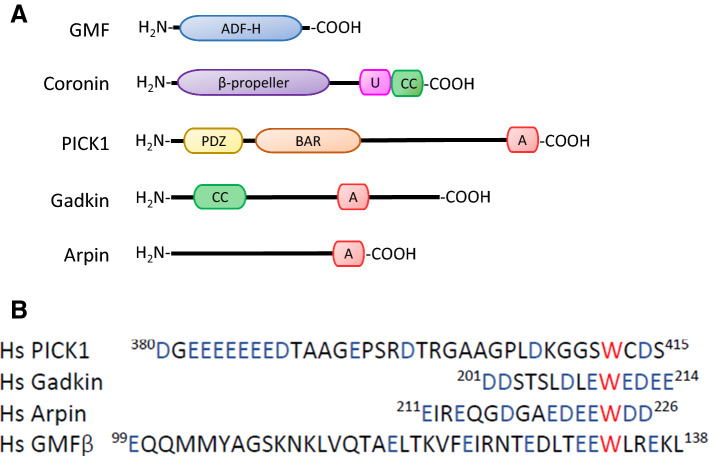

Members of the coronin family are conserved actin cytoskeleton regulators. In mammals, seven coronin genes exist that are classified into three types: I, II and III. Type I and II coronins have a similar structural organization. Both have a WD40 repeat, which is a short structural motif of ~ 40 amino acids often terminating in a Trp–Asp dipeptide, a β-propeller domain that allows scaffolding of protein–protein interactions; highly conserved N-terminal and C-terminal motifs that regulate interactions with other proteins and stabilize the β-propeller: a coiled-coil (CC) domain at the C-terminal end, which is involved in oligomerization; and a highly variable unique region that links the β-propeller with the CC-domain at the C-terminus (Fig. 1). The type III coronin lacks the CC, and has two β-propellers with N- and C-terminal extensions, and an acidic region at the C-terminal end [10].

Fig. 1.

Domain structures of PIA. a Coronins of type I and II have a similar structural organization: a β-propeller, a unique region (U) and a coiled-coil (CC) domain, which binds to Arp2/3. PICK1 possesses a PDZ, a BAR, and an acidic domain. Gadkin contains a CC and an acidic domain. For arpin, only an acidic domain has been described so far. The acidic domains of PICK1, gadkin, and arpin mediate binding to Arp2/3. b Alignment of the acidic domains of human PICK1, gadkin, and arpin, and the acidic-like domain in GMF. Acidic residues are shown in blue, the conserved tryptophan residue is in red (PICK1 protein ID: BAA89294.1; the human gadkin ortholog is called AP1AR ID: NP_061039.3; arpin: NP_872422.1; GMF: NP_004115.1)

Four proteins belong to type I coronins: coronin 1A, coronin 1B, coronin 1C and coronin 6; two proteins belong to type II: coronin 2A and coronin 2B; and coronin 7 is the only type III protein. Type I coronins are the most investigated to date, except for coronin 6 whose gene has only recently been identified. Coronin 1A is predominantly expressed in hematopoietic cells, whereas coronin 1B, coronin 1C and coronin 2A are ubiquitously expressed. Coronin 2B is enriched in the nervous system, and coronin 7 is thought to be ubiquitously expressed and localizes to the Golgi complex [10].

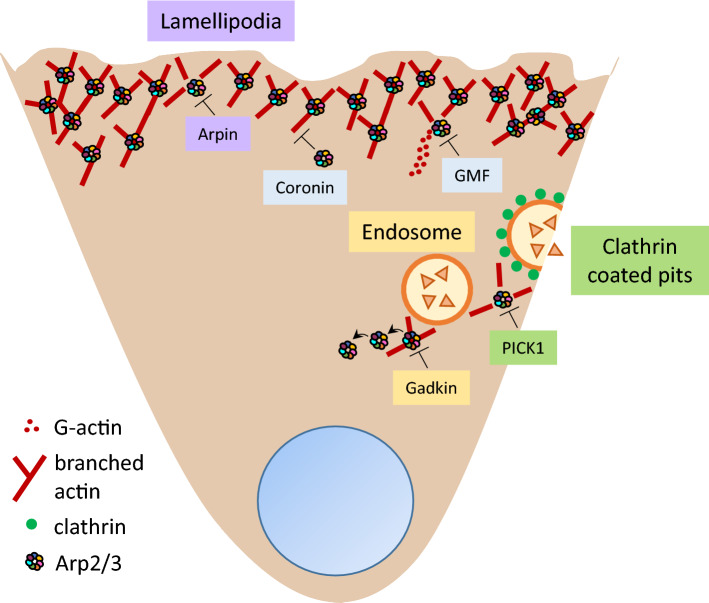

It is well known that type I and II coronins bind to Arp2/3 and inhibit its activity (Fig. 2) [11]. Coronins can inhibit Arp2/3 in yeast by preventing its binding to F-actin [12]. Interestingly, yeast coronin Crn1 not only inhibits Arp2/3 but can also activate it in a concentration-dependent fashion. At low concentrations, Crn1 can activate Arp2/3 likely through a central-acidic (CA) domain localized in the unique region, which is highly homologous to the acidic domain of the NPF Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome protein (WASP) and may establish an amphipathic helix that interacts with Arp2/3 and promotes activating conformational changes [12]. Of note, the CA sequence of Crn1 is not conserved in metazoan type I and II coronins [12], suggesting different functions of coronins in different species.

Fig. 2.

Negative regulation of Arp2/3 by PIA. The Arp2/3 complex can be regulated in a compartmentalized manner: PICK1 inhibits Arp2/3 activity at clathrin-coated pits, gadkin at endosomes, and arpin at lamellipodia. PICK1 and arpin compete with NPFs, whereas gadkin sequesters Arp2/3 at intracellular sites. Coronins inhibit Arp2/3 by blocking the Arp2 and Arp3 subunits and preventing NPFs from activating it. GMFs inhibit activation of Arp2/3 by competing with the VCA domain of the NPF WASP and by debranching induction. However, recent studies suggest that the inhibitors may also have redundant functions, and that they may act synergistically in different subcellular compartments

Besides directly regulating the activity of Arp2/3, coronin 1B enhances the activity of cofilin by binding and recruiting the phosphatase SSH, a necessary cofactor for cofilin activation, to F-actin. Thus, coronin 1B can regulate motility and lamellipodial dynamics in fibroblasts [13]. Furthermore, coronin 1B antagonizes the activity of cortactin, a well-known actin branch stabilizer, in lamellipodia. In this model, the competition between coronin 1B and cortactin for binding both F-actin and Arp2/3 is necessary for correct lamellipodial dynamics [14]. The activity of coronin 1B is regulated by a CK2-dependent phosphorylation at residue Ser463 within the CC leading to loss of affinity for Arp2/3 [15]. Coronin 1B also gets phosphorylated at Ser2 in response to methamphetamine via MAPK-signaling in the blood–brain barrier [16]; and VEGF via p38α in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) [17] to inhibit coronin 1B interaction with Arp2/3.

There are several reports about the implications of coronin 1A in numerous diseases and pathologies. Mutated Coronin1AE26K has been identified in mice carrying the locus of peripheral T cell deficiency. This mutation enhances Arp2/3 binding activity causing increased Arp2/3 inhibition, translocation of coronin 1A away from the leading edge of migrating T cells and, consequently, reduced thymic egress of T cells [18]. The function-impairing non-sense mutation Q262X that disrupts the β-propeller structure in coronin 1A leads to T cell dysfunction including disturbed migration in a systemic lupus erythematosus mouse model [19]. Importantly, coronin 1A KO mice are resistant to the development of experimental autoimmune encephalitis [20]. During aplastic anemia and hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, coronin 1A is overexpressed causing an overactivation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells [21]. Thus, coronin 1A plays important roles in autoimmune diseases by regulating T cell functions. Coronin 1A deficiency also decreases the numbers of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and increases the susceptibility to viral infections [22]. Of note, in HUVEC, depletion of coronin 1A reduces apoptosis induced by tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) [23]. More studies are needed to unravel whether the observed effects are a direct cause of coronin-mediated Arp2/3 inhibition in these pathologies.

GMFs

The glia maturation factors (GMFs) are conserved proteins, from yeast to mammals. Yeasts have just one GMF protein, whereas mammals have two GMF proteins, GMFβ and GMFγ [24]. Both have a similar structure, but they are expressed in different tissues: GMFβ is ubiquitously expressed but enriched in the brain, and GMFγ is expressed in immune cells and microvascular endothelium [25]. Of note, studies on GMF structure revealed that it has an actin-depolymerizing factor homology (ADF-H) domain (Fig. 1), thus belonging to the ADF-H family including ADF/Cofilin, Twinfilin, actin-binding protein-1 and coactosin [24].

GMFs bind with high affinity to the Arp2 and Arp3 subunits of the Arp2/3 complex through a broad surface termed “site 1” in its ADF-H domain, which is in sequence and structure similar to the G/F-binding site of cofilin in its ADF-H domain. In vitro, GMFs can inhibit activation of Arp2/3 by competing with the VCA domain of the NPFs WASP for Arp2/3 binding [26–29]. Additionally, GMFs have another surface termed “site 2” in its ADF-H domain, which binds specifically to the first actin subunit of daughter actin filaments. This domain is homologous to the cofilin surface that binds specifically to F-actin, in its ADF-H domain. Thus, GMFs also destabilize Arp2/3-actin branch junctions leading to debranching by a mechanism similar to cofilin (Fig. 2) [24, 26, 27]. Interestingly, a recent report showed that Arp2/3-mediated branches can be protected by actin-binding protein-1 from GMF-mediated debranching [30], suggesting that the branch junction is subject to fine-tuned regulation by different actin-binding proteins.

GMFγ functions in hematopoietic cells are related to chemotaxis, endocytosis, migration and cell adhesion [31–33], and are supposed to be related to GMF-mediated Arp2/3 inhibition, although direct experimental evidence for such a causal effect is still lacking. Of note, expression of GMFγ in epithelial ovarian cancer has been reported, which was related to cell migration and invasion [34]. Phosphorylation at Ser-2 diminishes GMFγ affinity for Arp2/3 in vitro [29]. Phosphorylation at Tyr-104 in the C-terminus promotes dissociation of GMFγ from Arp2/3 due to possible conformational changes leading to increased actin network assembly and force development in smooth muscle [35]. On the other hand, in mouse embryonic fibroblasts, GMFβ can destabilize Arp2/3-actin branch junctions and weakly inhibit N-WASP-mediated Arp2/3 activation suggesting that GMFβ is relevant for migration and lamellipodial dynamics [36].

GMFβ expression has been associated with neuro degenerative disorders. In Alzheimer’s disease mouse models, high GMF expression is correlated with high levels of inflammatory cytokines/chemokines and neuronal damage [37]. Furthermore, brain tissue biopsies from Alzheimer’s disease patients showed overexpression of GMFβ in the cerebral cortex and the hippocampus [38, 39]. In all these cases, GMFβ is mostly localized in astrocytes and colocalized with neurofibrillary tangles. Another disease related to GMFβ overexpression in the brain is experimental autoimmune encephalitis [40]. Transgenic mice that overexpress GMFs are more susceptible to experimental autoimmune encephalitis and express high levels of proinflammatory cytokines [40], suggesting a remarkable pathological role of GMFβ in this disease model. Overexpression of GMFβ in mouse tissues other than brain has been linked to premature aging due to increased oxidative stress [41]. Overexpression of GMFβ is correlated with poor prognosis and overall poor survival of serous ovarian cancer as well as malignant glioma [42, 43].

Sequestering Arp2/3: Gadkin

Gadkin (γ-1 and kinesin interactor), also called AP1AR, is an S-palmitoylated protein that binds to the clathrin adaptor AP-1, membranes of TGN-derived endosomal vesicles, early endosomes, and mainly late endosomes [44, 45]. Gadkin harbors a coiled-coil domain and an acidic domain (Fig. 1) [44, 46]. Gadkin directly interacts with Arp2/3 as revealed by proteomic analysis of gadkin recombinant protein incubated with rat brain extracts and co-immunoprecipitation assays [46]. Gadkin binds to the Arp2/3 complex through its acidic domain, and this interaction is blocked by the N-WASP-VCA domain in competition assays. However, gadkin does not prevent actin polymerization triggered by the WASP-VCA domain and Arp2/3 [46]. Instead, gadkin prevents Arp2/3 activation by sequestering it at intracellular sites in the absence of migratory stimuli (Fig. 2). For example, in B16F1 cells grown on Matrigel, where cells do not form lamellipodia, gadkin partially colocalizes with some pools of intracellular Arp2/3. By contrast, in cells grown on laminin, which activates GTPases upstream of NPFs leading to lamellipodia formation, colocalization with gadkin at intracellular sites is lost and relocalization of Arp2/3 to the plasma membrane can be observed. In agreement with this, blocking Rac1 activation causes gadkin and Arp2/3 colocalization in structures resembling endosomes [46].

Gadkin is expressed in ovary, testes, adrenal gland, brain, spleen, pancreas, lung, liver, stomach, and kidney [46]. It is distributed in a punctate pattern in the cytosol, and enriched at the perinuclear region where it colocalizes with AP-1 [44, 45]. Gadkin also interacts with kinesin-related protein 5 (KIF5) and colocalizes with transferrin receptor, Rab 11 and Rab4, proteins involved in trafficking of recycling endosomes and early endosomes, suggesting a regulatory role of gadkin in the endocytic pathway [45]. siRNA-mediated depletion of gadkin in A431 cells diminishes the release of hexosaminidase and cathepsin D indicating a role of gadkin in secretory processes [47]. Depletion of gadkin in mouse melanoma B16F1 cells increases cell spreading, size, shape, and migration [46]. Furthermore, isolated mouse embryonic fibroblasts from gadkin KO mice have increased cell size and show Arp2/3 enrichment at the plasma membrane [46]. Bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDC) isolated from gadkin KO mice show normal differentiation, maturation, macropinocytosis and cell spreading [48]. However, chemotaxis is reduced in vitro, but not in vivo, suggesting a compensatory process in the more complex in vivo environment, but details explaining this discrepancy remain unknown. Gadkin deficiency in BMDC cells does not affect expression or intracellular distribution of Arp2/3, which is intriguing because gadkin can sequester Arp2/3 in absence of pro-migratory signaling; however, increased F-actin content in gadkin KO BDMC supports the idea that gadkin negatively regulates Arp2/3 also in these cells [48]. Interestingly, LPS treatment increases gadkin expression in gadkin WT BMDC [48], and in gadkin KO BMDC LPS decreases mRNA levels of the proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-12β, and TNFα [49]. Although, at present, no disease has been reported in which gadkin plays a role, these findings open a new path for studying gadkin functions in inflammatory diseases.

Competitive Arp2/3 inhibitors

PICK1

PICK1 was found to be associated with the protein C-kinase α-subunit, hence its name [50]. PICK1 contains a PDZ domain at the N-terminus, and a BAR domain and an acidic domain at the C-terminus (Fig. 1) [51–53]. PICK1 binds to F-actin and Arp2/3 through its BAR and acidic domain, respectively [53]. PICK1 is expressed in heart, brain, lung, liver, skeletal muscle, kidney and testes, with the highest levels in brain and testes [50]. PICK1 competes with the N-WASP-VCA domain for the binding site on Arp2/3, and also inhibits actin polymerization stimulated by this activator [53]. In hippocampal neurons, PICK1 is important for correct neuronal morphology during development, glutamate AMPA receptor-endocytosis, dendritic spine size and spine shrinkage plasticity [53–55]. PICK1–Arp2/3 interaction is required for this shrinkage plasticity because in cultured hippocampal neurons expressing a mutation in the PICK1-binding site for Arp2/3 this reduction of spine size is blocked [54]. PICK1 is important for vesicle trafficking [56–58]. Also in hippocampal neurons, PICK1 colocalizes with clathrin at clathrin-coated pits, where it participates in the trafficking of AMPA receptors, and the authors proposed that PICK1–Arp2/3 interaction limits F-actin density at clathrin-coated pits establishing a dynamic actin environment for their subsequent cleavage (Fig. 2) [59, 60].

In cortical cultured neurons, the GTPase Arf1 binds to PICK1 to prevent its interaction with Arp2/3 and actin, leading to inhibition of trafficking of the AMPA receptor GluA2 [61]. In cortical astrocytes isolated from brains of postnatal rats, N-WASP-induced Arp2/3 activation contributes to the development of the typical astrocyte morphology [62]. In these cells, depletion of PICK1 opposes the phenotypic effects of those observed in Arp3 and N-WASP-depleted cells. Thus, PICK1 blocks N-WASP-Arp2/3-mediated actin polymerization and together they fine-tune astrocyte morphology [53, 62]. In adrenal chromaffin cells, PICK1 deficiency causes reduced exocytosis and decreases the number and size of large, dense-core vesicles [58]. However, PICK1 may also regulate vesicle motility in an Arp2/3-independent fashion without detectable PICK1–Arp2/3 interaction or PICK1-mediated Arp2/3 inhibition [63]. However, in another study PICK1 and Arp2/3 could be co-immunoprecipitated from extracts of primary hippocampal cultures [53], and colocalization of PICK1 and Arp2/3 could be detected in human gastric carcinoma AGS cells coexpressing GFP-PICK1 and mCherry-Arp3 [64].

PICK1 is also expressed in the epithelial cell lines MDCK and Caco-2. In MDCK cells, localization of PICK1-GFP suggests an interaction with β-catenin and the adherens junction protein AF-6. In COS cells, PICK1 interacts with junctional adhesion molecule-A and -C and nectin-2α [65]. In Xenopus, PICK1 interacts with the ligand of ephrinB1, which plays a role in cell adhesion. In Xenopus embryos, PICK1 deficiency leads to defects in ventral trunk formation and epidermal cell dissociation [66].

PICK1 is highly expressed in testes, and PICK1 KO mice have smaller testes, increased apoptosis in the seminiferous tubules, decreased sperm number, globozoospermia, abnormal spermiogenesis, and acrosome malformation [67, 68]. In fact, a homozygous mutation has been found in the C-terminus of PICK1 in a patient with globozoospermia, and heterozygous mutations have been found in two of his relatives [69]. It will be interesting to analyze if PICK1-mediated Arp2/3 inhibition is relevant for the pathogenesis of globozoospermia.

PICK1 is overexpressed in cancerous tissues of patients with breast, lung, gastric, colorectal, and ovarian cancer compared to non-cancerous tissues. This upregulation is associated with poor prognosis, thus establishing PICK1 as a tumor-promoting factor [70]. This apparently contradicts the also observed overactivation of Arp2/3 in many tumor tissues [71–74]. A possible explanation for this discrepancy could be the involvement of PICK1 in transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) signaling, which is also critical in tumor cells [75]. PICK1 binds to the TGF-β type I receptor (TβRI) through its PDZ domain, thus acting as a scaffold protein that mediates interaction of TβRI and caveolin-1, and promotes TβRI endocytosis and degradation [76]. In human breast tumor tissues, negative correlations have been observed between PICK1 and TβRI expression; and between PICK1 and phosphorylation of Smad2, which is an important signaling molecule downstream of TGFβ-TβRI signaling [76]. On the other hand, depletion of PICK1 in breast cancer cells causes less proliferation and diminishes the tumor size in mice injected with these cells [70]. By contrast, in the human astrocyte tumor cell line U251, PICK1 expression is reduced, as well as in samples of human astrocytic tumors. Overexpressing PICK1 in U251 cells limits cell migration, invasion and the formation of colonies in soft agar [77]. Cell migration is unaffected in cells expressing a PICK1 mutated in its tryptophan residue 413 (W413A), which is suggested to be indispensable for binding to the Arp2/3 complex [77].

PICK1 polymorphisms are associated with psychiatric schizophrenia in a Japanese population (rs2076369), and in different Japanese and Chinese populations (rs3952) [78, 79]. However, a different study reported that there is no susceptibility for this disease in another Japanese population carrying the above-mentioned polymorphisms [80]. Moreover, synapses weakening caused by amyloid beta in Alzheimer’s disease requires interaction of the AMPA receptor GluA2 with PICK1 [81]. PICK1 might also be involved in Parkinson’s disease, as it binds parkin via its BAR domain, thus restricting the activity of parkin E3 ligase, which is important for its neuroprotective properties. Interestingly, PICK1 KO mice are resistant to the neurotoxin 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridin [82]. PICK1 has also been related to epilepsy because it interacts with metabotropic glutamate receptor 7 [83]. Besides, PICK1 expression is triggered in activated astrocytes during amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in rats [84]. Thus, inhibiting the activity of PICK1 might be a promising treatment strategy for neurodegenerative diseases.

PICK1 has also been involved in diseases other than cancer, for example sepsis and diabetes [85, 86]. Analysis of metabolic parameters in PICK1 KO mice indicates that they are diabetic due to less insulin secretion by β-pancreatic cells. Also, PICK1 interacts with ICA69, an autoantigen from type I diabetes patients [24]. The absence of PICK1 in mice worsens the severity of sepsis in a cecal ligation and puncture mouse model. However, PICK1 is overexpressed in CLP-induced sepsis in mice and in septic patients, which was correlated with increased oxidative stress [4].

All these studies highlight the pathophysiological relevance of PICK1. However, it remains elusive whether the described effects are a consequence of disturbed PICK1-dependent regulation of Arp2/3 activity. To solve this question, new small molecules have been identified that inhibit PICK1 activity [81, 87, 88]. Such molecules will be useful to further characterize PICK1 functions and may pave the way for new treatment strategies for neurological and metabolic disorders.

Arpin

Arpin is the most recently described Arp2/3 complex inhibitor. It is expressed in brain, lung, kidney, spleen, liver, mucosa, jejunum, and colon [89]. Arpin contains an elongated globular core with an extended, linear carboxy-terminal end that harbors an acidic domain (Fig. 1), which is able to compete with NPFs for binding to Arp2/3, as has been shown for the N-WASP-VCA domain, leading to inhibition of actin branching [90, 91]. Single-particle electron microscopy analysis has shown that arpin stabilizes the inactive state (open conformation) of the Arp2/3 complex [92]. In contrast to NPFs that require activators to induce a conformational change providing exposure of their acidic domain, the acidic domain of arpin is always accessible [91, 93]. Thus, arpin activity is rather regulated in a spatio-temporal manner via recruitment to sites where antagonism with NPFs is required.

Arpin is located at the lamellipodial tip of spreading mouse embryonic fibroblasts (Fig. 2), colocalizing with Arp2/3 and Brk1, a subunit of the WAVE complex suggesting the coexistence of two molecules with antagonistic functions in lamellipodia that is spatio-temporally regulated [90]. According to its lamellipodial location, arpin modulates the speed and persistence of random migration [90]. In retinal pigmented epithelial RPE1 cells, arpin depletion causes higher speed and persistence of random migration [94]. Overexpressing arpin in fish keratinocytes decreases the active phase of migration due to frequent migration pauses that allow the cells to turn. By contrast, depleting expression of arpin in breast cancer cells and amoebas increased the duration of active migration, and pauses are less frequent [95]. Of note, arpin was not required for chemotaxis of breast cancer cells stimulated with fetal calf serum and epidermal growth factor (EGF), and of Dictyostelium amoeba stimulated with cAMP [96]. Loss of the ArpC3 subunit in fibroblasts results in a substantial reduction of chemotaxis toward an EGF gradient [7]. However, in another study using microfluidic devices, Arp2/3-depleted fibroblasts that lack lamellipodia showed a normal chemotactic response to PDGF [97]. The discrepancy was later resolved when it was shown that Arp2/3-depleted fibroblasts changed their expression profile and secreted many factors such as chemokines and growth factors that were able to block EGF-induced chemotaxis. Thus, Arp2/3-depletion causes non-autonomous effects on chemotaxis [98]. These results indicate that arpin and Arp2/3 are dispensable for chemotaxis.

A proposal has been suggested that Arp2/3 is regulated in a compartmentalized way, i.e., specific Arp2/3 activators at specific subcellular structures are antagonized by certain PIA in the very same subcellular structures. According to this proposal, N-WASP and PICK1 control Arp2/3 activity at clathrin-coated pits, WASH and gadkin at endosomes, and WAVE and arpin at lamellipodia (Fig. 2) [9, 99]. However, experimental evidence is required to validate this proposal.

Arpin protein levels are increased in colonic mucosal tissues from patients with severe acute pancreatitis compared to control groups. The authors speculate that arpin upregulation contributes to bacterial translocation through tight junction disruption due to higher claudin-2 and lower ZO-1 and occludin expression [100].

As arpin is important for migration, an immediate interest was to study its expression in cancer where enhanced migratory capacity is characteristic for invasion and metastasis. Arpin is downregulated in breast cancer biopsies compared with paratumour control tissue, with arpin expression being lowest when the disease is most advanced [101]. Downregulation of arpin in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells causes increased migration and proliferation [102]. Vice versa, overexpression of arpin in MDA-MB-231 cells causes less proliferation and an arrest in the G0/G1 cell cycle accompanied by suppression of the cell cycle molecules p27, cyclin D1, CDK4, and phosphorylation of Akt. Moreover, cancer cells that overexpress arpin decrease invasiveness, and tumor size in xenotransplanted mice compared with control cells [103]. Very recently, a new mechanism controlling cell cycle progression has been identified, in which cortical actin branches nucleated by ArpC1B-containing Arp2/3 via a Rac1/WAVE/arpin pathway control G1/S cell cycle transition [104]. These cortical branched actin networks, which are increased in arpin-depleted or ArpC1B-overexpressing cells, transmit the signals provided by extracellular matrix anchorage or growth factors. Coronin-1B is enriched at these cortical branches where it serves as sensor and specifically decorates ARPC1B-containing branches to prevent them from debranching. Of note, ArpC1B overexpression in breast cancer cells is strongly associated with poor prognosis and potentiated cell cycle progression. Moreover, tumor cells characterized by activating Rac1 mutations proliferate significantly less upon Arp2/3 inhibition with CK666. The authors suggest that specific inhibition of ARPC1B-containing Arp2/3 via small molecule inhibitors to prevent cell cycle progression of tumor cells could be a new treatment strategy for metastatic cancers that are characterized by uncontrolled proliferation and migration. All these data suggest that arpin, in contrast to PICK1, may be a tumor suppressor molecule.

Downregulation of arpin has also been observed in other types of cancers such as colorectal and gastric cancer, and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma [102, 105, 106]. For example, in gastric cancer, high Arp2/3 expression is accompanied with less arpin expression [105]. In neck squamous cell carcinoma, lower levels of the anti-migratory microRNA miR-198 lead to upregulation of diaphanous homolog 1, which sequesters arpin as part of a pro-migratory mechanism to promote metastasis formation [107]. Downregulation of arpin seems to be a conserved effect in different types of cancer. Current data at least imply that low arpin levels in cancer cells contribute to invasion by uncontrolled Arp2/3-driven invadopodia formation. More studies are required to better understand how arpin downregulation affects Arp2/3-dependent cancer cell functions before establishing low arpin levels as diagnostic biomarker for poor prognosis.

Recently, a single nucleotide polymorphism (rs2028299) in the 3’ UTR of arpin was identified in visceral human fat samples that was associated with type 2 diabetes [108], suggesting that arpin may also play an important role in the pathogenesis of diseases other than cancer.

Pharmacological inhibition of the Arp2/3 complex

CK666

CK666 is a small molecule with a fluorobenzene ring that binds specifically to the Arp2/3 complex between the subunits Arp2 and Arp3, thus preventing the conformational change required for Arp2/3 activation. However, this compound does not block the binding of NPFs to Arp2/3 [109, 110]. Of note, treatment of mouse embryonic fibroblasts deficient for both ArpC2 and Arp2 with CK666 does not cause additional phenotypic effects [97], suggesting that CK666 is a specific inhibitor of Arp2/3.

CK666 reduces lamellipodia formation and migration in murine epithelial duct cells, coelomycetes, and in the neutrophil-like cell line HL60 [111–113]. In neurons of the sea slug Aplysia, CK666 increases actin flow rate resulting in veil retraction [114]. In epithelial alveolar progenitor cells isolated from mouse lungs, CK666 diminishes the number of membrane projections [115]. Moreover, CK666 weakens intercellular adhesion in MDCK cell monolayers [116] and increases permeability to 3 kDa dextran indicating that active Arp2/3 is critical for maintenance of epithelial barrier functions [117]. Treatment of HUVEC monolayers with CK666 leads to gap formation [118, 119]. In human lung endothelial cells, CK666 decreases transendothelial electrical resistance and increases permeability to 70 kDa FITC-avidin [120]. By contrast, CK666 attenuates the increase in blood–brain barrier permeability induced by methamphetamine [121] in vitro and in vivo due to inhibition of occludin internalization. Additionally, CK666 prevents monocyte transmigration across a brain microvascular endothelial cell line [16]. These data strongly suggest that Arp2/3 inhibition by CK666 in vivo regulates vascular barrier function. The discrepancies between the data from endothelial cells and MDCK cells are currently unclear but might be explained by the different cell type, different exposure times, and also different cell confluencies given that at nascent adhesions Arp2/3 activity is high, but decreases during cell–cell contact maturation [122].

In mice, loss-of-function of the subunit ArpC3 is lethal due to impaired trophoblast outgrowth [6]. Similarly, inhibition of Arp2/3 activity with CK666 in mouse oocytes results in disruption of asymmetric division and impaired cytokinesis [123], confirming that Arp2/3 is critical for differentiation and development of different cell types [124–126].

Migration and invasion of cancer cells required for metastasis are also inhibited by CK666. For example, in human glioma cell lines CK666 suppresses migration and increases cofilin-1 expression [74, 125].

Effects of CK666 have also been studied in infection models, where pathogens hijack host Arp2/3 to induce actin cytoskeleton rearrangement and to facilitate invasion of host cells. In the ovarian cancer cell line SKOV3, CK666 prevents the formation of actin filament comet tails by Listeria monocytogenes [109]. In polarized Caco-2 cells, Arp2/3 inhibition by CK666 restricts infection with the enteropathogenic E. coli strain KC12 by interfering with pedestal formation and limiting actin-based motility [127]. CK666 treatment in Vero cells prevents CCV formation to sustain growth of Coxiella burnetii [128].

Inhibition of Arp2/3 might favor increased activity of other actin nucleators such as formins [111] and result in the formation of formin-mediated actin structures due to increased availability of G-actin monomers after Arp2/3 inhibition that are then available for the formins [129]. Indeed, fission yeast expressing Life-Act increases formin-mediated actin assembly after CK666 treatment [129]. In coelomycetes, CK666 favored G-actin binding to barbed ends of preexisting actin filaments resulting in the formation of elongated filopodia-like structures, which are usually triggered by formins [111].

Little is known about the signaling pathways regulated by CK666. Treatment of HS68, WM2664 and MDCK cells with CK666 activates the canonical NF-κB pathway [98], and in mouse mesenchymal stromal cells it leads to adipogenesis by increasing mRNA and protein levels of the adipogenic markers Pparg, Fabp4, and Adipoq [130].

Taken together, inhibition of Arp2/3 with CK666 shows mostly detrimental effects in most cell types with some exceptions observed during drug abuse and infections. Also, CK666-mediated inhibition of cancer cell migration could certainly prove beneficial. It will be interesting to further analyze the signaling pathways regulated by CK666 in order to determine if it could be used as treatment approach for many devastating diseases.

CK869

CK869 is a cell-permeable thiazolidinone compound with methoxy groups in the ortho and para positions. This small molecule inhibitor binds to the Arp2/3 complex in a hydrophobic pocket on the Arp3 subunit, which allosterically causes structural changes in the Arp2–Arp3 dimer short pitch and thus destabilizes the active conformation of Arp2/3 [109, 110], in contrast to CK666 that stabilizes the inactive conformation of the Arp2/3 complex [110]. CK869 only inhibits the mammalian Arp2/3 complex. A change of methionine to tryptophan in position 93 of the Arp3 subunit in other species prevents CK869 from inhibiting their Arp2/3 complex [109]. Thus, CK869 is not as well studied as CK666.

CK869 decreases cell motility and inhibits lamellipodia formation in mouse kidney cells [112]. In the epithelial cell line MCF-10A, inhibition of Arp2/3 with CK869 also disrupts lamellipodia formation [131]. Moreover, in rat fibroblast, CK869 inhibits microtubule assembly due to suppression of microtubule elongation from the plus-ends in an Arp2/3-independent manner suggesting that CK869 is not as specific as CK666. It will be interesting to unravel a potential crosstalk between Arp2/3-dependent actin branches and microtubules [132], and the molecular mechanisms by which CK869 regulates such cell functions.

Conclusions

Tight regulation of Arp2/3 is of utmost importance for any cell type to function correctly. Uncontrolled activation is correlated with the onset and progression of many diseases. Therefore, further study and understanding of endogenous and pharmacological Arp2/3 inhibitors are warranted. Recent advances include for example the identification of arpin and the proposal of a compartmentalized regulation of Arp2/3, with a given NPF being counter-regulated by a certain PIA. In addition to the PIA described in this review, other proteins such as cofilin and tropomyosins can also have an indirect inhibitory effect on Arp2/3 via modulating the presence of binding sites on actin filaments [121, 133–135]. Certainly, more research is needed to better understand the (competitive) mechanisms by which PIA fine-tune Arp2/3 activity. We are confident that many exciting discoveries regarding Arp2/3 inhibitors are still ahead of us, and hope that our review will stimulate many research groups to contribute to this fascinating and expanding field.

Acknowledgements

Work in the laboratory of Michael Schnoor regarding Arp2/3 inhibition is funded by Grant 284292 of the Mexican National Council for Science and Technology (Conacyt).

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Garcia-Ponce A, Citalan-Madrid AF, Velazquez-Avila M, Vargas-Robles H, Schnoor M. The role of actin-binding proteins in the control of endothelial barrier integrity. Thromb Haemost. 2015;113:20–36. doi: 10.1160/TH14-04-0298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rouiller I, Xu XP, Amann KJ, Egile C, Nickell S, Nicastro D, Li R, Pollard TD, Volkmann N, Hanein D. The structural basis of actin filament branching by the Arp2/3 complex. J Cell Biol. 2008;180:887–895. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200709092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pizarro-Cerda J, Chorev DS, Geiger B, Cossart P. The diverse family of Arp2/3 complexes. Trends Cell Biol. 2017;27:93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2016.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abella JV, Galloni C, Pernier J, Barry DJ, Kjaer S, Carlier MF, Way M. Isoform diversity in the Arp2/3 complex determines actin filament dynamics. Nat Cell Biol. 2016;18:76–86. doi: 10.1038/ncb3286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chorev DS, Moscovitz O, Geiger B, Sharon M. Regulation of focal adhesion formation by a vinculin-Arp2/3 hybrid complex. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3758. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yae K, Keng VW, Koike M, Yusa K, Kouno M, Uno Y, Kondoh G, Gotow T, Uchiyama Y, Horie K, Takeda J. Sleeping beauty transposon-based phenotypic analysis of mice: lack of Arpc3 results in defective trophoblast outgrowth. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:6185–6196. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00018-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suraneni P, Rubinstein B, Unruh JR, Durnin M, Hanein D, Li R. The Arp2/3 complex is required for lamellipodia extension and directional fibroblast cell migration. J Cell Biol. 2012;197:239–251. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201112113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rotty JD, Wu C, Bear JE. New insights into the regulation and cellular functions of the ARP2/3 complex. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:7–12. doi: 10.1038/nrm3492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Molinie N, Gautreau A. The Arp2/3 regulatory system and its deregulation in cancer. Physiol Rev. 2018;98:215–238. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00006.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan KT, Creed SJ, Bear JE. Unraveling the enigma: progress towards understanding the coronin family of actin regulators. Trends Cell Biol. 2011;21:481–488. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Humphries CL, Balcer HI, D’Agostino JL, Winsor B, Drubin DG, Barnes G, Andrews BJ, Goode BL. Direct regulation of Arp2/3 complex activity and function by the actin binding protein coronin. J Cell Biol. 2002;159:993–1004. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200206113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu SL, Needham KM, May JR, Nolen BJ. Mechanism of a concentration-dependent switch between activation and inhibition of Arp2/3 complex by coronin. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:17039–17046. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.219964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cai L, Marshall TW, Uetrecht AC, Schafer DA, Bear JE. Coronin 1B coordinates Arp2/3 complex and cofilin activities at the leading edge. Cell. 2007;128:915–929. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cai L, Makhov AM, Schafer DA, Bear JE. Coronin 1B antagonizes cortactin and remodels Arp2/3-containing actin branches in lamellipodia. Cell. 2008;134:828–842. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xavier CP, Rastetter RH, Blomacher M, Stumpf M, Himmel M, Morgan RO, Fernandez MP, Wang C, Osman A, Miyata Y, Gjerset RA, Eichinger L, Hofmann A, Linder S, Noegel AA, Clemen CS. Phosphorylation of CRN2 by CK2 regulates F-actin and Arp2/3 interaction and inhibits cell migration. Sci Rep. 2012;2:241. doi: 10.1038/srep00241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park M, Kim HJ, Lim B, Wylegala A, Toborek M. Methamphetamine-induced occludin endocytosis is mediated by the Arp2/3 complex-regulated actin rearrangement. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:33324–33334. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.483487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim GY, Park JH, Kim H, Lim HJ, Park HY. Coronin 1B serine 2 phosphorylation by p38alpha is critical for vascular endothelial growth factor-induced migration of human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Cell Signal. 2016;28:1817–1825. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2016.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shiow LR, Roadcap DW, Paris K, Watson SR, Grigorova IL, Lebet T, An J, Xu Y, Jenne CN, Foger N, Sorensen RU, Goodnow CC, Bear JE, Puck JM, Cyster JG. The actin regulator coronin 1A is mutant in a thymic egress-deficient mouse strain and in a patient with severe combined immunodeficiency. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:1307–1315. doi: 10.1038/ni.1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haraldsson MK, Louis-Dit-Sully CA, Lawson BR, Sternik G, Santiago-Raber ML, Gascoigne NR, Theofilopoulos AN, Kono DH. The lupus-related Lmb3 locus contains a disease-suppressing Coronin-1A gene mutation. Immunity. 2008;28:40–51. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Siegmund K, Zeis T, Kunz G, Rolink T, Schaeren-Wiemers N, Pieters J. Coronin 1-mediated naive T cell survival is essential for the development of autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2011;186:3452–3461. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu XJ, Tang YM. Coronin-1a is a potential therapeutic target for activated T cell-related immune disorders. APMIS. 2015;123:89–91. doi: 10.1111/apm.12277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tchang VS, Mekker A, Siegmund K, Karrer U, Pieters J. Diverging role for coronin 1 in antiviral CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses. Mol Immunol. 2013;56:683–692. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim GY, Kim H, Lim HJ, Park HY. Coronin 1A depletion protects endothelial cells from TNFalpha-induced apoptosis by modulating p38beta expression and activation. Cell Signal. 2015;27:1688–1693. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2015.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goode BL, Sweeney MO, Eskin JA. GMF as an actin network remodeling factor. Trends Cell Biol. 2018;28:749–760. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2018.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ikeda K, Kundu RK, Ikeda S, Kobara M, Matsubara H, Quertermous T. Glia maturation factor-gamma is preferentially expressed in microvascular endothelial and inflammatory cells and modulates actin cytoskeleton reorganization. Circ Res. 2006;99:424–433. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000237662.23539.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gandhi M, Smith BA, Bovellan M, Paavilainen V, Daugherty-Clarke K, Gelles J, Lappalainen P, Goode BL. GMF is a cofilin homolog that binds Arp2/3 complex to stimulate filament debranching and inhibit actin nucleation. Curr Biol. 2010;20:861–867. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ydenberg CA, Padrick SB, Sweeney MO, Gandhi M, Sokolova O, Goode BL. GMF severs actin-Arp2/3 complex branch junctions by a cofilin-like mechanism. Curr Biol. 2013;23:1037–1045. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.04.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luan Q, Nolen BJ. Structural basis for regulation of Arp2/3 complex by GMF. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20:1062–1068. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boczkowska M, Rebowski G, Dominguez R. Glia maturation factor (GMF) interacts with Arp2/3 complex in a nucleotide state-dependent manner. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:25683–25688. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C113.493338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guo S, Sokolova OS, Chung J, Padrick S, Gelles J, Goode BL. Abp1 promotes Arp2/3 complex-dependent actin nucleation and stabilizes branch junctions by antagonizing GMF. Nat Commun. 2018;9:2895. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05260-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aerbajinai W, Liu L, Chin K, Zhu J, Parent CA, Rodgers GP. Glia maturation factor-gamma mediates neutrophil chemotaxis. J Leukoc Biol. 2011;90:529–538. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0710424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lippert DN, Wilkins JA. Glia maturation factor gamma regulates the migration and adherence of human T lymphocytes. BMC Immunol. 2012;13:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-13-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aerbajinai W, Liu L, Zhu J, Kumkhaek C, Chin K, Rodgers GP. Glia maturation factor-gamma regulates monocyte migration through modulation of beta1-integrin. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:8549–8564. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.674200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zuo P, Fu Z, Tao T, Ye F, Chen L, Wang X, Lu W, Xie X. The expression of glia maturation factors and the effect of glia maturation factor-gamma on angiogenic sprouting in zebrafish. Exp Cell Res. 2013;319:707–717. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang T, Cleary RA, Wang R, Tang DD. Glia maturation factor-gamma phosphorylation at Tyr-104 regulates actin dynamics and contraction in human airway smooth muscle. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2014;51:652–659. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2014-0125OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haynes EM, Asokan SB, King SJ, Johnson HE, Haugh JM, Bear JE. GMFbeta controls branched actin content and lamellipodial retraction in fibroblasts. J Cell Biol. 2015;209:803–812. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201501094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zaheer A, Zaheer S, Thangavel R, Wu Y, Sahu SK, Yang B. Glia maturation factor modulates beta-amyloid-induced glial activation, inflammatory cytokine/chemokine production and neuronal damage. Brain Res. 2008;1208:192–203. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.02.093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thangavel R, Kempuraj D, Stolmeier D, Anantharam P, Khan M, Zaheer A. Glia maturation factor expression in entorhinal cortex of Alzheimer’s disease brain. Neurochem Res. 2013;38:1777–1784. doi: 10.1007/s11064-013-1080-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stolmeier D, Thangavel R, Anantharam P, Khan MM, Kempuraj D, Zaheer A. Glia maturation factor expression in hippocampus of human Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem Res. 2013;38:1580–1589. doi: 10.1007/s11064-013-1059-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zaheer S, Wu Y, Sahu SK, Zaheer A. Overexpression of glia maturation factor reinstates susceptibility to myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein-induced experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in glia maturation factor deficient mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2010;40:593–598. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Imai R, Asai K, Hanai J, Takenaka M. Transgenic mice overexpressing glia maturation factor-beta, an oxidative stress inducible gene, show premature aging due to Zmpste24 down-regulation. Aging (Albany NY) 2015;7:486–499. doi: 10.18632/aging.100779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li YL, Ye F, Cheng XD, Hu Y, Zhou CY, Lu WG, Xie X. Identification of glia maturation factor beta as an independent prognostic predictor for serous ovarian cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:2104–2118. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kuang XY, Jiang XF, Chen C, Su XR, Shi Y, Wu JR, Zhang P, Zhang XL, Cui YH, Ping YF, Bian XW. Expressions of glia maturation factor-beta by tumor cells and endothelia correlate with neovascularization and poor prognosis in human glioma. Oncotarget. 2016;7:85750–85763. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Neubrand VE, Will RD, Mobius W, Poustka A, Wiemann S, Schu P, Dotti CG, Pepperkok R, Simpson JC. Gamma-BAR, a novel AP-1-interacting protein involved in post-Golgi trafficking. EMBO J. 2005;24:1122–1133. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schmidt MR, Maritzen T, Kukhtina V, Higman VA, Doglio L, Barak NN, Strauss H, Oschkinat H, Dotti CG, Haucke V. Regulation of endosomal membrane traffic by a Gadkin/AP-1/kinesin KIF5 complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:15344–15349. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904268106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maritzen T, Zech T, Schmidt MR, Krause E, Machesky LM, Haucke V. Gadkin negatively regulates cell spreading and motility via sequestration of the actin-nucleating ARP2/3 complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:10382–10387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206468109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Laulagnier K, Schieber NL, Maritzen T, Haucke V, Parton RG, Gruenberg J. Role of AP1 and Gadkin in the traffic of secretory endo-lysosomes. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22:2068–2082. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e11-03-0193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schachtner H, Weimershaus M, Stache V, Plewa N, Legler DF, Hopken UE, Maritzen T. Loss of Gadkin affects dendritic cell migration in vitro. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0143883. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mertins P, Przybylski D, Yosef N, Qiao J, Clauser K, Raychowdhury R, Eisenhaure TM, Maritzen T, Haucke V, Satoh T, Akira S, Carr SA, Regev A, Hacohen N, Chevrier N. An integrative framework reveals signaling-to-transcription events in Toll-like receptor signaling. Cell Rep. 2017;19:2853–2866. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Staudinger J, Zhou J, Burgess R, Elledge SJ, Olson EN. PICK1: a perinuclear binding protein and substrate for protein kinase C isolated by the yeast two-hybrid system. J Cell Biol. 1995;128:263–271. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.3.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Staudinger J, Lu J, Olson EN. Specific interaction of the PDZ domain protein PICK1 with the COOH terminus of protein kinase C-alpha. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:32019–32024. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.51.32019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Peter BJ, Kent HM, Mills IG, Vallis Y, Butler PJ, Evans PR, McMahon HT. BAR domains as sensors of membrane curvature: the amphiphysin BAR structure. Science. 2004;303:495–499. doi: 10.1126/science.1092586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rocca DL, Martin S, Jenkins EL, Hanley JG. Inhibition of Arp2/3-mediated actin polymerization by PICK1 regulates neuronal morphology and AMPA receptor endocytosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:259–271. doi: 10.1038/ncb1688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nakamura Y, Wood CL, Patton AP, Jaafari N, Henley JM, Mellor JR, Hanley JG. PICK1 inhibition of the Arp2/3 complex controls dendritic spine size and synaptic plasticity. EMBO J. 2011;30:719–730. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Anggono V, Clem RL, Huganir RL. PICK1 loss of function occludes homeostatic synaptic scaling. J Neurosci. 2011;31:2188–2196. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5633-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Haglerod C, Kapic A, Boulland JL, Hussain S, Holen T, Skare O, Laake P, Ottersen OP, Haug FM, Davanger S. Protein interacting with C kinase 1 (PICK1) and GluR2 are associated with presynaptic plasma membrane and vesicles in hippocampal excitatory synapses. Neuroscience. 2009;158:242–252. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mignogna ML, Giannandrea M, Gurgone A, Fanelli F, Raimondi F, Mapelli L, Bassani S, Fang H, Van Anken E, Alessio M, Passafaro M, Gatti S, Esteban JA, Huganir R, D’Adamo P. The intellectual disability protein RAB39B selectively regulates GluA2 trafficking to determine synaptic AMPAR composition. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6504. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pinheiro PS, Jansen AM, de Wit H, Tawfik B, Madsen KL, Verhage M, Gether U, Sorensen JB. The BAR domain protein PICK1 controls vesicle number and size in adrenal chromaffin cells. J Neurosci. 2014;34:10688–10700. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5132-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fiuza M, Rostosky CM, Parkinson GT, Bygrave AM, Halemani N, Baptista M, Milosevic I, Hanley JG. PICK1 regulates AMPA receptor endocytosis via direct interactions with AP2 alpha-appendage and dynamin. J Cell Biol. 2017;216:3323–3338. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201701034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hanley JG. The regulation of AMPA receptor endocytosis by dynamic protein–protein interactions. Front Cell Neurosci. 2018;12:362. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2018.00362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rocca DL, Amici M, Antoniou A, Blanco Suarez E, Halemani N, Murk K, McGarvey J, Jaafari N, Mellor JR, Collingridge GL, Hanley JG. The small GTPase Arf1 modulates Arp2/3-mediated actin polymerization via PICK1 to regulate synaptic plasticity. Neuron. 2013;79:293–307. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Murk K, Blanco Suarez EM, Cockbill LM, Banks P, Hanley JG. The antagonistic modulation of Arp2/3 activity by N-WASP, WAVE2 and PICK1 defines dynamic changes in astrocyte morphology. J Cell Sci. 2013;126:3873–3883. doi: 10.1242/jcs.125146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Madasu Y, Yang C, Boczkowska M, Bethoney KA, Zwolak A, Rebowski G, Svitkina T, Dominguez R. PICK1 is implicated in organelle motility in an Arp2/3 complex-independent manner. Mol Biol Cell. 2015;26:1308–1322. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E14-10-1448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sathe M, Muthukrishnan G, Rae J, Disanza A, Thattai M, Scita G, Parton RG, Mayor S. Small GTPases and BAR domain proteins regulate branched actin polymerisation for clathrin and dynamin-independent endocytosis. Nat Commun. 2018;9:1835. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03955-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Reymond N, Garrido-Urbani S, Borg JP, Dubreuil P, Lopez M. PICK-1: a scaffold protein that interacts with Nectins and JAMs at cell junctions. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:2243–2249. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Son J, Park MS, Park I, Lee HK, Lee SH, Kang B, Min BH, Ryoo J, Lee S, Bae JS, Kim SH, Park MJ, Lee HS. Pick1 modulates ephrinB1-induced junctional disassembly through an association with ephrinB1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;450:659–665. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Xiao N, Kam C, Shen C, Jin W, Wang J, Lee KM, Jiang L, Xia J. PICK1 deficiency causes male infertility in mice by disrupting acrosome formation. J Clin Investig. 2009;119:802–812. doi: 10.1172/JCI36230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.He J, Xia M, Tsang WH, Chow KL, Xia J. ICA1L forms BAR-domain complexes with PICK1 and is crucial for acrosome formation in spermiogenesis. J Cell Sci. 2015;128:3822–3836. doi: 10.1242/jcs.173534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Liu G, Shi QW, Lu GX. A newly discovered mutation in PICK1 in a human with globozoospermia. Asian J Androl. 2010;12:556–560. doi: 10.1038/aja.2010.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhang B, Cao W, Zhang F, Zhang L, Niu R, Niu Y, Fu L, Hao X, Cao X. Protein interacting with C alpha kinase 1 (PICK1) is involved in promoting tumor growth and correlates with poor prognosis of human breast cancer. Cancer Sci. 2010;101:1536–1542. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01566.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang W, Wyckoff JB, Frohlich VC, Oleynikov Y, Huttelmaier S, Zavadil J, Cermak L, Bottinger EP, Singer RH, White JG, Segall JE, Condeelis JS. Single cell behavior in metastatic primary mammary tumors correlated with gene expression patterns revealed by molecular profiling. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6278–6288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zheng HC, Zheng YS, Li XH, Takahashi H, Hara T, Masuda S, Yang XH, Guan YF, Takano Y. Arp2/3 overexpression contributed to pathogenesis, growth and invasion of gastric carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2008;28:2225–2232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rauhala HE, Teppo S, Niemela S, Kallioniemi A. Silencing of the ARP2/3 complex disturbs pancreatic cancer cell migration. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:45–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Liu Z, Yang X, Chen C, Liu B, Ren B, Wang L, Zhao K, Yu S, Ming H. Expression of the Arp2/3 complex in human gliomas and its role in the migration and invasion of glioma cells. Oncol Rep. 2013;30:2127–2136. doi: 10.3892/or.2013.2669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Massague J. TGFbeta in cancer. Cell. 2008;134:215–230. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhao B, Wang Q, Du J, Luo S, Xia J, Chen YG. PICK1 promotes caveolin-dependent degradation of TGF-beta type I receptor. Cell Res. 2012;22:1467–1478. doi: 10.1038/cr.2012.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cockbill LM, Murk K, Love S, Hanley JG. Protein interacting with C kinase 1 suppresses invasion and anchorage-independent growth of astrocytic tumor cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2015;26:4552–4561. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E15-05-0270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hong CJ, Liao DL, Shih HL, Tsai SJ. Association study of PICK1 rs3952 polymorphism and schizophrenia. NeuroReport. 2004;15:1965–1967. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200408260-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fujii K, Maeda K, Hikida T, Mustafa AK, Balkissoon R, Xia J, Yamada T, Ozeki Y, Kawahara R, Okawa M, Huganir RL, Ujike H, Snyder SH, Sawa A. Serine racemase binds to PICK1: potential relevance to schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;11:150–157. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ishiguro H, Koga M, Horiuchi Y, Inada T, Iwata N, Ozaki N, Ujike H, Muratake T, Someya T, Arinami T. PICK1 is not a susceptibility gene for schizophrenia in a Japanese population: association study in a large case-control population. Neurosci Res. 2007;58:145–148. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2007.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Alfonso S, Kessels HW, Banos CC, Chan TR, Lin ET, Kumaravel G, Scannevin RH, Rhodes KJ, Huganir R, Guckian KM, Dunah AW, Malinow R. Synapto-depressive effects of amyloid beta require PICK1. Eur J Neurosci. 2014;39:1225–1233. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.He J, Xia M, Yeung PKK, Li J, Li Z, Chung KK, Chung SK, Xia J. PICK1 inhibits the E3 ubiquitin ligase activity of Parkin and reduces its neuronal protective effect. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:E7193–E7201. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1716506115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bertaso F, Zhang C, Scheschonka A, de Bock F, Fontanaud P, Marin P, Huganir RL, Betz H, Bockaert J, Fagni L, Lerner-Natoli M. PICK1 uncoupling from mGluR7a causes absence-like seizures. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:940–948. doi: 10.1038/nn.2142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Focant MC, Goursaud S, Boucherie C, Dumont AO, Hermans E. PICK1 expression in reactive astrocytes within the spinal cord of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) rats. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2013;39:231–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2012.01282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cao M, Mao Z, Kam C, Xiao N, Cao X, Shen C, Cheng KK, Xu A, Lee KM, Jiang L, Xia J. PICK1 and ICA69 control insulin granule trafficking and their deficiencies lead to impaired glucose tolerance. PLoS Biol. 2013;11:e1001541. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Qian M, Lou Y, Wang Y, Zhang M, Jiang Q, Mo Y, Han K, Jin S, Dai Q, Yu Y, Wang Z, Wang J. PICK1 deficiency exacerbates sepsis-associated acute lung injury and impairs glutathione synthesis via reduction of xCT. Free Radic Biol Med. 2018;118:23–34. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lin EYS, Silvian LF, Marcotte DJ, Banos CC, Jow F, Chan TR, Arduini RM, Qian F, Baker DP, Bergeron C, Hession CA, Huganir RL, Borenstein CF, Enyedy I, Zou J, Rohde E, Wittmann M, Kumaravel G, Rhodes KJ, Scannevin RH, Dunah AW, Guckian KM. Potent PDZ-domain PICK1 inhibitors that modulate amyloid beta-mediated synaptic dysfunction. Sci Rep. 2018;8:13438. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-31680-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Thorsen TS, Madsen KL, Rebola N, Rathje M, Anggono V, Bach A, Moreira IS, Stuhr-Hansen N, Dyhring T, Peters D, Beuming T, Huganir R, Weinstein H, Mulle C, Stromgaard K, Ronn LC, Gether U. Identification of a small-molecule inhibitor of the PICK1 PDZ domain that inhibits hippocampal LTP and LTD. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:413–418. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902225107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gautreau A, Vacher S, Sousa-Blin C, Derivery E, Gorelik R (2014) Use of arpin a new inhibitor of the Arp2/3 complex for the diagnosis and treatment of diseases. Patent# US20160199445A1

- 90.Dang I, Gorelik R, Sousa-Blin C, Derivery E, Guerin C, Linkner J, Nemethova M, Dumortier JG, Giger FA, Chipysheva TA, Ermilova VD, Vacher S, Campanacci V, Herrada I, Planson AG, Fetics S, Henriot V, David V, Oguievetskaia K, Lakisic G, Pierre F, Steffen A, Boyreau A, Peyrieras N, Rottner K, Zinn-Justin S, Cherfils J, Bieche I, Alexandrova AY, David NB, Small JV, Faix J, Blanchoin L, Gautreau A. Inhibitory signalling to the Arp2/3 complex steers cell migration. Nature. 2013;503:281–284. doi: 10.1038/nature12611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Fetics S, Thureau A, Campanacci V, Aumont-Nicaise M, Dang I, Gautreau A, Perez J, Cherfils J. Hybrid structural analysis of the Arp2/3 regulator arpin identifies its acidic tail as a primary binding epitope. Structure. 2016;24:252–260. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sokolova OS, Chemeris A, Guo S, Alioto SL, Gandhi M, Padrick S, Pechnikova E, David V, Gautreau A, Goode BL. Structural basis of Arp2/3 complex inhibition by GMF, Coronin, and Arpin. J Mol Biol. 2017;429:237–248. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2016.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Jia D, Gomez TS, Metlagel Z, Umetani J, Otwinowski Z, Rosen MK, Billadeau DD. WASH and WAVE actin regulators of the Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome protein (WASP) family are controlled by analogous structurally related complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:10442–10447. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913293107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Maiuri P, Rupprecht JF, Wieser S, Ruprecht V, Benichou O, Carpi N, Coppey M, De Beco S, Gov N, Heisenberg CP, Lage Crespo C, Lautenschlaeger F, Le Berre M, Lennon-Dumenil AM, Raab M, Thiam HR, Piel M, Sixt M, Voituriez R. Actin flows mediate a universal coupling between cell speed and cell persistence. Cell. 2015;161:374–386. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.01.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gorelik R, Gautreau A. The Arp2/3 inhibitory protein arpin induces cell turning by pausing cell migration. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 2015;72:362–371. doi: 10.1002/cm.21233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Dang I, Linkner J, Yan J, Irimia D, Faix J, Gautreau A. The Arp2/3 inhibitory protein Arpin is dispensable for chemotaxis. Biol Cell. 2017;109:162–166. doi: 10.1111/boc.201600064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wu C, Asokan SB, Berginski ME, Haynes EM, Sharpless NE, Griffith JD, Gomez SM, Bear JE. Arp2/3 is critical for lamellipodia and response to extracellular matrix cues but is dispensable for chemotaxis. Cell. 2012;148:973–987. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wu C, Haynes EM, Asokan SB, Simon JM, Sharpless NE, Baldwin AS, Davis IJ, Johnson GL, Bear JE. Loss of Arp2/3 induces an NF-kappaB-dependent, nonautonomous effect on chemotactic signaling. J Cell Biol. 2013;203:907–916. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201306032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Krause M, Gautreau A. Steering cell migration: lamellipodium dynamics and the regulation of directional persistence. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:577–590. doi: 10.1038/nrm3861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Deng WS, Zhang J, Ju H, Zheng HM, Wang J, Wang S, Zhang DL. Arpin contributes to bacterial translocation and development of severe acute pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:4293–4301. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i14.4293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Liu X, Zhao B, Wang H, Wang Y, Niu M, Sun M, Zhao Y, Yao R, Qu Z. Aberrant expression of Arpin in human breast cancer and its clinical significance. J Cell Mol Med. 2016;20:450–458. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lomakina ME, Lallemand F, Vacher S, Molinie N, Dang I, Cacheux W, Chipysheva TA, Ermilova VD, de Koning L, Dubois T, Bieche I, Alexandrova AY, Gautreau A. Arpin downregulation in breast cancer is associated with poor prognosis. Br J Cancer. 2016;114:545–553. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2016.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Li Y, Qiu J, Pang T, Guo Z, Su Y, Zeng Q, Zhang X. Restoration of Arpin suppresses aggressive phenotype of breast cancer cells. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;92:116–121. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.05.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Molinie N, Rubtsova SN, Fokin A, Visweshwaran SP, Rocques N, Polesskaya A, Schnitzler A, Vacher S, Denisov EV, Tashireva LA, Perelmuter VM, Cherdyntseva NV, Bieche I, Gautreau AM. Cortical branched actin determines cell cycle progression. Cell Res. 2019 doi: 10.1038/s41422-019-0168-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Li T, Zheng HM, Deng NM, Jiang YJ, Wang J, Zhang DL. Clinicopathological and prognostic significance of aberrant Arpin expression in gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:1450–1457. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i8.1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Zhang SR, Li H, Wang WQ, Jin W, Xu JZ, Xu HX, Wu CT, Gao HL, Li S, Li TJ, Zhang WH, Xu SS, Ni QX, Yu XJ, Liu L. Arpin downregulation is associated with poor prognosis in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2018;45:769–775. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2018.10.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Sundaram GM, Ismail HM, Bashir M, Muhuri M, Vaz C, Nama S, Ow GS, Vladimirovna IA, Ramalingam R, Burke B, Tanavde V, Kuznetsov V, Lane EB, Sampath P. EGF hijacks miR-198/FSTL1 wound-healing switch and steers a two-pronged pathway toward metastasis. J Exp Med. 2017;214:2889–2900. doi: 10.1084/jem.20170354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Franzen O, Ermel R, Sukhavasi K, Jain R, Jain A, Betsholtz C, Giannarelli C, Kovacic JC, Ruusalepp A, Skogsberg J, Hao K, Schadt EE, Bjorkegren JLM. Global analysis of A-to-I RNA editing reveals association with common disease variants. PeerJ. 2018;6:e4466. doi: 10.7717/peerj.4466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Nolen BJ, Tomasevic N, Russell A, Pierce DW, Jia Z, McCormick CD, Hartman J, Sakowicz R, Pollard TD. Characterization of two classes of small molecule inhibitors of Arp2/3 complex. Nature. 2009;460:1031–1034. doi: 10.1038/nature08231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Hetrick B, Han MS, Helgeson LA, Nolen BJ. Small molecules CK-666 and CK-869 inhibit actin-related protein 2/3 complex by blocking an activating conformational change. Chem Biol. 2013;20:701–712. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2013.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Henson JH, Yeterian M, Weeks RM, Medrano AE, Brown BL, Geist HL, Pais MD, Oldenbourg R, Shuster CB. Arp2/3 complex inhibition radically alters lamellipodial actin architecture, suspended cell shape, and the cell spreading process. Mol Biol Cell. 2015;26:887–900. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E14-07-1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ilatovskaya DV, Chubinskiy-Nadezhdin V, Pavlov TS, Shuyskiy LS, Tomilin V, Palygin O, Staruschenko A, Negulyaev YA. Arp2/3 complex inhibitors adversely affect actin cytoskeleton remodeling in the cultured murine kidney collecting duct M-1 cells. Cell Tissue Res. 2013;354:783–792. doi: 10.1007/s00441-013-1710-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Wilson K, Lewalle A, Fritzsche M, Thorogate R, Duke T, Charras G. Mechanisms of leading edge protrusion in interstitial migration. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2896. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Yang Q, Zhang XF, Pollard TD, Forscher P. Arp2/3 complex-dependent actin networks constrain myosin II function in driving retrograde actin flow. J Cell Biol. 2012;197:939–956. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201111052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Li J, Wang Z, Chu Q, Jiang K, Li J, Tang N. The strength of mechanical forces determines the differentiation of alveolar epithelial cells. Dev Cell. 2018;44(297–312):e5. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2018.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Harris AR, Daeden A, Charras GT. Formation of adherens junctions leads to the emergence of a tissue-level tension in epithelial monolayers. J Cell Sci. 2014;127:2507–2517. doi: 10.1242/jcs.142349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Van Itallie CM, Tietgens AJ, Krystofiak E, Kachar B, Anderson JM. A complex of ZO-1 and the BAR-domain protein TOCA-1 regulates actin assembly at the tight junction. Mol Biol Cell. 2015;26:2769–2787. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E15-04-0232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Abu Taha A, Taha M, Seebach J, Schnittler HJ. ARP2/3-mediated junction-associated lamellipodia control VE-cadherin-based cell junction dynamics and maintain monolayer integrity. Mol Biol Cell. 2014;25:245–256. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e13-07-0404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Efimova N, Svitkina TM. Branched actin networks push against each other at adherens junctions to maintain cell–cell adhesion. J Cell Biol. 2018;217:1827–1845. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201708103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Belvitch P, Brown ME, Brinley BN, Letsiou E, Rizzo AN, Garcia JGN, Dudek SM. The ARP 2/3 complex mediates endothelial barrier function and recovery. Pulm Circ. 2017;7:200–210. doi: 10.1086/690307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Goley ED, Rammohan A, Znameroski EA, Firat-Karalar EN, Sept D, Welch MD. An actin-filament-binding interface on the Arp2/3 complex is critical for nucleation and branch stability. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:8159–8164. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911668107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Sumida GM, Yamada S. Rho GTPases and the downstream effectors actin-related protein 2/3 (Arp2/3) complex and myosin II induce membrane fusion at self-contacts. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:3238–3247. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.612168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Sun SC, Wang ZB, Xu YN, Lee SE, Cui XS, Kim NH. Arp2/3 complex regulates asymmetric division and cytokinesis in mouse oocytes. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18392. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Zhou K, Muroyama A, Underwood J, Leylek R, Ray S, Soderling SH, Lechler T. Actin-related protein2/3 complex regulates tight junctions and terminal differentiation to promote epidermal barrier formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:E3820–E3829. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1308419110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Zhou T, Wang CH, Yan H, Zhang R, Zhao JB, Qian CF, Xiao H, Liu HY. Inhibition of the Rac1-WAVE2-Arp2/3 signaling pathway promotes radiosensitivity via downregulation of cofilin-1 in U251 human glioma cells. Mol Med Rep. 2016;13:4414–4420. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.5088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Wang F, An GY, Zhang Y, Liu HL, Cui XS, Kim NH, Sun SC. Arp2/3 complex inhibition prevents meiotic maturation in porcine oocytes. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87700. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Velle KB, Campellone KG. Extracellular motility and cell-to-cell transmission of enterohemorrhagic E. coli is driven by EspFU-mediated actin assembly. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13:e1006501. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Miller HE, Larson CL, Heinzen RA. Actin polymerization in the endosomal pathway, but not on the Coxiella-containing vacuole, is essential for pathogen growth. PLoS Pathog. 2018;14:e1007005. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Burke TA, Christensen JR, Barone E, Suarez C, Sirotkin V, Kovar DR. Homeostatic actin cytoskeleton networks are regulated by assembly factor competition for monomers. Curr Biol. 2014;24:579–585. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.01.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Sen B, Uzer G, Samsonraj RM, Xie Z, McGrath C, Styner M, Dudakovic A, van Wijnen AJ, Rubin J. Intranuclear actin structure modulates mesenchymal stem cell differentiation. Stem Cells. 2017;35:1624–1635. doi: 10.1002/stem.2617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Beckham Y, Vasquez RJ, Stricker J, Sayegh K, Campillo C, Gardel ML. Arp2/3 inhibition induces amoeboid-like protrusions in MCF10A epithelial cells by reduced cytoskeletal-membrane coupling and focal adhesion assembly. PLoS One. 2014;9:e100943. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Yamagishi Y, Oya K, Matsuura A, Abe H. Use of CK-548 and CK-869 as Arp2/3 complex inhibitors directly suppresses microtubule assembly both in vitro and in vivo. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;496:834–839. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.01.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]