Abstract

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a degenerative movement disorder resulting from the loss of specific neuron types in the midbrain. Early environmental and pathophysiological studies implicated mitochondrial damage and protein aggregation as the main causes of PD. These findings are now vindicated by the characterization of more than 20 genes implicated in rare familial forms of the disease. In particular, two proteins encoded by the Parkin and PINK1 genes, whose mutations cause early-onset autosomal recessive PD, function together in a mitochondrial quality control pathway. In this review, we will describe recent development in our understanding of their mechanisms of action, structure, and function. We explain how PINK1 acts as a mitochondrial damage sensor via the regulated proteolysis of its N-terminus and the phosphorylation of ubiquitin tethered to outer mitochondrial membrane proteins. In turn, phospho-ubiquitin recruits and activates Parkin via conformational changes that increase its ubiquitin ligase activity. We then describe how the formation of polyubiquitin chains on mitochondria triggers the recruitment of the autophagy machinery or the formation of mitochondria-derived vesicles. Finally, we discuss the evidence for the involvement of these mechanisms in physiological processes such as immunity and inflammation, as well as the links to other PD genes.

Keywords: Parkinson, Ubiquitin, Kinase, Parkin, PINK1, Mitochondria

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is one of the most common and devastating neurodegenerative diseases, characterized by severe motor impairments, as well as non-motor symptoms such as sleep and mood disorders. These symptoms are caused by the loss of specific subtypes of neurons including, but not exclusively, dopamine neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) that project to the striatum. In affected neurons, there are intracellular protein aggregates called Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites, which are composed mainly of the protein α-synuclein [1]. PD affects about 2% of the population over 65 years old, and thus impinges strongly on our aging societies. While symptomatic therapies are available (mostly dopamine replacement therapy), there are still no disease-modifying treatments. The challenge is to identify the molecular events that lead to such selective neurodegeneration.

A key early observation came from patients who developed Parkinson-like symptoms following exposure to 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,5,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP), a by-product of clandestine desmethylprodine synthesis [2, 3]. MPTP is a potent inhibitor of complex I in the mitochondrial respiratory chain (RC). Furthermore, complex I activity is reduced in the brain of sporadic PD patients, and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) deletions are increased, implicating mitochondrial damage in the etiology of PD [4, 5]. Genetics studies emerging in the late 1990s then provided important clues towards identifying the molecular pathways of neurodegeneration in PD [6]. Among the first genes identified were SNCA, which encodes α-synuclein [7], and PARK2, which encodes the E3 ubiquitin ligase Parkin [8–10]. While PD caused by Parkin mutations are rare (less than 1% of all PD cases), they account for the majority of autosomal recessive juvenile Parkinsonism (ARJPD), with a mean age of onset as early as 25 years old for some mutations. Since then, over twenty genes have been implicated either in ARJPD (for example, PINK1 [11]), autosomal dominant PD (e.g., LRRK2 [12, 13]) or as risk factors (reviewed in [14]). Given the historical importance of Parkin in our understanding of PD, the vivid interest it generates in the ubiquitin field, and its rising profile as a pharmacological target, this review will concentrate on the function of Parkin and its activator, PINK1.

Since its discovery in 1998, Parkin has been implicated in many biological processes, such as mitochondrial quality control [15–17], synaptic excitability [18], vesicle endocytosis [19, 20], lipid uptake [21], inflammation and immunity [22–26]. While these processes are likely related through some fundamental processes involving mitochondria and endolysosomal trafficking, the jury is still out as to which of these functions are critical to its neuroprotective function. However, the past 10 years have seen mitochondrial quality control emerge as a central process controlled by Parkin. What distinguishes this process from others is its exclusive dependence on PINK1, a mitochondrial kinase that phosphorylates ubiquitin (Ub). The role of Parkin in mitochondrial quality control was initially ascribed in Drosophila models, where Parkin deletion induces muscle degeneration caused by mitochondrial dysfunction [27]. Deletion of PINK1 in Drosophila induces a highly similar phenotype, which can be rescued by Parkin overexpression [28, 29]. In mammalian cells following mitochondrial damage with respiratory chain inhibitors or depolarizing chemicals such as carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazine (CCCP), Parkin strikingly shifts from the cytosol to the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM) in response to PINK1 accumulation and Ub phosphorylation. On mitochondria, Parkin becomes active and ubiquitinates outer membrane proteins such as VDAC1/2/3 and Mfn1/2, a GTPase-mediating mitochondrial membrane fusion [30, 31]. Parkin-dependent ubiquitination leads to proteasomal degradation of substrates and triggers either selective autophagy of whole or subsets of mitochondria [17] or the generation of mitochondria-derived vesicles (MDVs) that carry damaged proteins to lysosomes for degradation [32]. Thus, while Parkin has little activity in the basal state, PINK1 can massively stimulate its activity in response to damage, leading to localized substrate ubiquitination.

In this review, we will describe recent advances in our understanding of Parkin/PINK1-dependent mitochondrial quality control, with an emphasis on the molecular and structural mechanisms underlying this process. We then put forward various hypotheses regarding the physiological function of this pathway in mitochondrial quality control and immunity.

PINK1 as a sensor of mitochondrial damage

Even though mitochondria have evolved to maintain their own genome and translational machinery, the majority of mitochondrial proteins remain encoded in the nucleus. To this end, most mitochondrial proteins are synthesized in the cytosol and must be imported into their correct mitochondrial compartment. The most common of these import pathways, seen in nearly 60% of all mitochondrial proteins, is driven by a cleavable stretch of N-terminal amino acids, coined mitochondrial targeting signals (MTS) [33]. These terminal MTS interact with specific translocases of the outer (TOM) and inner membranes (TIM), guiding the precursor protein across the mitochondrial membranes, before being cleaved off by the mitochondrial processing peptidase (MPP) in the mitochondrial matrix. More distal regions to the MTS are removed by other mitochondrial proteases, permitting proper folding and sorting of the mature protein. This intimate link between import and proteolysis is a tightly regulated process that is essential for proper mitochondrial function and consequently for neuronal health [34].

PINK1 is one substrate whose unique import and processing define its health sensing function. While the mitochondrial localization of PINK1 has been studied for over a decade [11, 35–37], recent work has highlighted the non-canonical import pathway which gates its accumulation on mitochondria. This was catalyzed by a few key observations: namely, PINK11–34, originally predicted to contain its MTS, is not required for PINK1’s localization, yet a PINK11–34-GFP chimera can still be imported into the matrix [38, 39]. Second, the PINK1 transmembrane domain (TMD) is flanked on both sides by critical regulatory elements: N-terminal to the TMD is a unique OMM localization signal [38], and C-terminal to the TMD is a triad of glutamic acid residues [40]. Taken together, these two features allow FL PINK1 to tether on the OMM and accumulate in response to damage.

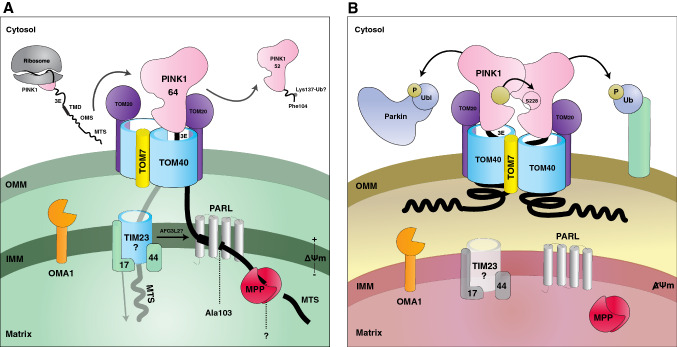

The current model for PINK1 damage sensing implicates numerous proteases and translocases: in healthy mitochondria, PINK1 is constitutively imported through the TOM complex, interacting with surface receptors (TOM20, TOM22, TOM70), and passing through the TOM40 pore [41]. At this stage, most MTS-containing proteins pass through the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM) TIM23 complex, requiring a mitochondrial membrane potential ΔΨm (reviewed in [42]). These proteins are then threaded into the matrix by the presequence translocase-associated motor (PAM) complex, including mtHSP70, where their MTS is removed by MPP and the rest of the protein primed for subsequent cleavage and/or sorting.

PINK1 undergoes multiple proteolytic steps (Fig. 1a): first, MPP in the matrix removes the MTS of PINK1 at an unknown residue, and second, PARL (presenilin-associated rhomboid-like protein) in the IMM cleaves PINK1 within its TMD after Ala103 [43–46]. In healthy mitochondria, this proteolytic cycle coordinates PINK1 release to the cytosol for degradation. Phe104 is a destabilizing N-terminal amino acid and the 52 kDa form of PINK1 builds up as cytosolic aggregates in cells lacking E3 ubiquitin ligases of the N-recognin family [47]. This model implies that Phe104 is retro-translocated to the cytosol following its cleavage in the IMM. However, Liu et al. showed that Phe104 is not exposed to the cytosol and further showed that PINK1 is ubiquitinated at Lys137, via an unknown E3 ubiquitin ligase [48]. Greene et al. showed that knockdown of AFG3L2 abrogates PARL maturation of PINK1, resulting instead in the accumulation of an MPP-cleaved PINK1 intermediate [43]. AFG3L2 is a matrix-facing, IMM-resident AAA + protease that may play a cooperative role in the second cleavage of PINK1, potentially by regulating its lateral translocation in the IMM to form a PARL-accessible intermediate, or through direct interaction with PARL itself. The molecular details of this cooperativity still remain to be explored, as detailed in a recent review [49].

Fig. 1.

Schematic of PINK1 import and processing. a PINK1 import and its proteolytic cycle in healthy, polarized mitochondria. PINK1 is translated on cytosolic ribosomes and threaded through TOM/TIM into the matrix, where it is subjected to its proteolytic cascade. After being cleaved by MPP, then PARL, it is retro-translocated and degraded. OMA1 serves as a surveillance mechanism for PINK1 that may escape TOM arrest. 3E glutamic acid triad E112/E113/E117 which gate its TOM7 arrest, TMD the transmembrane domain in which lies the PARL cleavage site, OMS the outer mitochondrial localization signal, MTS mitochondrial targeting signal. b PINK1 accumulation on depolarized mitochondria. Following mitochondrial damage, PINK1 is arrested in the TOM complex. MTS passage into the matrix is disrupted, as represented by the transparent TIM complex. Due to this, the PINK1 N-terminus is unable to be cleaved by MPP or PARL, and its N-terminus is left unprocessed. PINK1 oligomerizes and phosphorylates its dimeric partner in trans. Phosphorylation is depicted by the gold circles. Arrows coming from PINK1 depict phosphorylation of the Parkin Ubl domain (left), Ub tethered to an OMM protein (right), or itself (center)

In response to mitochondrial damage (most commonly via CCCP-induced depolarization), full-length PINK1 accumulates on the OMM [45, 50], where it forms a 720 kDa complex with the TOM complex (Fig. 1b) [41, 51]. In its OMM-stabilized form, PINK1 oligomerizes and recruits Parkin to initiate mitophagy, as discussed in later sections. Recently, it was shown that PINK1 OMM accumulation in response to mitochondrial depolarization requires TOM7, a small α-helical subunit associated on the outside of the TOM40 pore [52, 53]. This interaction with TOM7 may also be important in dictating PINK1 release for re-import, retro-translocation, or dimerization, according to local health status. While disruption of ΔΨm serves as a reporter of perturbed mitochondrial health, PINK1 has also been shown to respond to other ΔΨm-independent damage signals. For example, overexpression of mutant ornithine transcarbamoylase (∆OTC) or knockdown of LONP (a housekeeping AAA + protease) cause proteotoxic stress in the matrix and induce PINK1 accumulation [54, 55]. The TOM7 dependency in response to this proteotoxic stress has not been defined yet; it is unknown if the PINK1–TOM7 complex forms in the same fashion as CCCP-induced depolarization, as well as how these ΔΨm-independent signals (originating from the matrix) coordinate the selective arrest of PINK1. Other damage signals have also been suggested, including aberrant reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and mtDNA mutations, though their direct structural and functional consequences on PINK1 import are less clear [56, 57].

Recent work from the Youle lab characterized a triad of charged residues just after the TMD (Glu112, Glu113, Glu117) which are critical for PINK1–TOM7 arrest in depolarized mitochondria [40]. In the same study, OMA1 was also identified as a novel protease regulating PINK1 levels. The current model poises OMA1 as a safety net to degrade free or “mis-imported” PINK1 in the IMS, either caused by TOM7 deficiency or certain PD mutants. Strikingly, the import of PINK1 (as measured by the production of its PARL-cleaved form) was uniquely resilient to knockdowns of TIM23 and mtHSP70, while other matrix-destined precursors accumulated [40]. Consequently, it is not clear whether there is an alternative mode of import for the PINK1 N-terminus and how MPP and/or PARL might access the PINK1 MTS and TMD in these cases. Even though the MPP–PARL axis is now widely accepted, the interactions driving PINK1 retro-translocation also remain elusive. Moreover, it will be important to investigate which internal tethers, whether in the IMS, IMM, or matrix, may bind the PINK1 N-terminus (a.a. 1–90) while it is arrested by TOM7 with its kinase domain in the cytosol.

This highlights many unanswered questions about the orchestration of PINK1 import, sorting, and accumulation: how might OMA1 exert its IMS quality control on endogenous, WT PINK1, and where exactly is the OMA1 cleavage site? What is the structure and stoichiometry of the oligomeric PINK1–TOM assembly? Since PINK1 import is not dependent on mtHSP70, what other matrix-localized or IMM machinery might ensure its sorting? What are the mechanisms gating lateral PINK1 release in both the OMM and IMM? PD mutations located after the TMD (I111S, C125G, Q126P) are unable to accumulate on the OMM in response to CCCP and are instead degraded by OMA1 within the IMS, which hint at components on the OMM regulating lateral transfer. However, the molecular consequences of more N-terminal PINK1 mutants (e.g., G32R, P52L, R67F, R68P) have not yet been elucidated. Characterizing these mutants may shed light on the interactions taking place during the sorting and proteolysis of PINK1 and reveal novel modes of import in mitochondria.

PINK1 is an ubiquitin kinase

If the N-terminus of PINK1 surveys damage within mitochondria and tethers FL PINK1 to local sites of repair, this status is ultimately relayed to the cytosol through PINK1’s kinase activity. The importance of this relay is reflected in PD genetics, as the majority of PD-linked PINK1 mutations are clustered within its kinase domain, many of which are loss of function [58]. As the structure and function of kinases have been extensively reviewed over the years, this review will focus only on the distinguishing features of PINK1 and those needed to contextualize certain mutations [59]. While all kinases share a conserved bilobal architecture (N- and C-lobes), PINK1 contains divergent features, including three inserts within its N-lobe and a C-terminal extension (CTE), which are critical for its biological activity [60, 61].

In 2010, it was first shown that PINK1’s kinase activity is essential for mitophagy, as a kinase-dead (i.e., catalytically inactive) mutant of PINK1 localized to mitochondria but was unable to recruit Parkin [50, 62, 63]. Shortly after, PINK1 was found to phosphorylate both Ub and the Ubl domain of Parkin to initiate mitophagy, thus making PINK1 the first ubiquitin kinase [64–68]. PINK1 activation requires autophosphorylation at Ser228, which takes place as PINK1 stalls on the OMM [51, 69–71]. While Ser402 was initially proposed as a second autophosphorylation site, it was dispelled by two key observations: the S402A mutant was thermally unstable at 37 °C and the S402N mutant was still active, suggesting that Ser402 acts primarily to stabilize PINK1 independent of its phosphorylation [72].

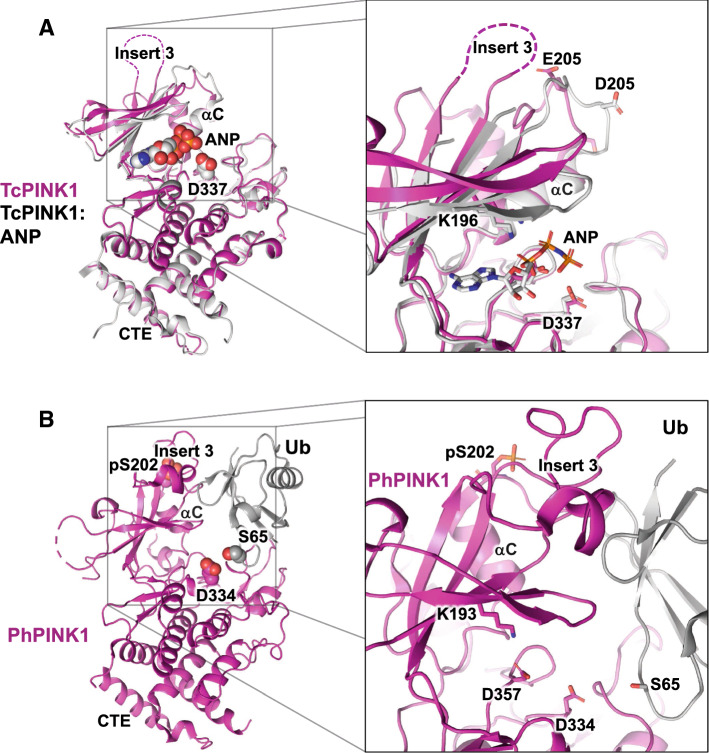

Within the last 2 years, crystal structures of insect orthologs of PINK1, along with NMR and mass spectrometry studies have rapidly advanced our understanding of PINK1 autophosphorylation and have revealed the conformational changes that PINK1 undergoes upon substrate binding (Fig. 2). Specifically, three crystal structures have been reported: flour beetle PINK1 (Tribolium castaneum, TcPINK1), both apo- and in complex with the non-hydrolysable ATP analogue AMP-PNP [73, 74], as well as body louse PINK1 (Pediculus humanus corporis, PhPINK1) in complex with Ub and a nanobody [75]. The precise structural changes have been recently reviewed by our group [76], and thus, we will focus on the broader implications of this regulation, and what we have learned from the recent PINK1 structure bound to AMP-PNP [73].

Fig. 2.

Structures of PINK1 in the apo-, nucleotide-, and Ub-bound forms. a Structures of TcPINK1 (pdb 5OAT, chain A, magenta) and TcPINK1 bound to AMP-PNP (pdb 5YJ9, white). The inset on the right shows the nucleotide-binding site. The invariant Lys196 interacts with the α, β-phosphate groups of AMP-PNP and the catalytic base (Asp337) is in proximity to the γ-phosphate group. Both proteins had phosphomimetic mutations at the main phosphorylation site (S205E and S205D). Insert 3 is disordered in both structures. b Structure of PhPINK1 (pdb 6EQI, chain C, magenta) in complex with the Ub T66V-L71N mutant (chain A, gray), which adopts the minor extended conformation. The structure was determined in complex with a single-chain antibody (chain B, not shown). The inset shows the features of the Ub-binding site. The phosphate group on Ser202 stabilizes insert 3, which is then primed to make interactions with Ub. The structure also reveals a dramatic 90° rotation of the αC helix. The extended conformation of Ub exposes the side chain of Ser65, making it available for deprotonation by the catalytic base Asp334

The first key observation is that phosphorylation at Ser228 in human PINK1 (Ser202/Ser205 in Ph/TcPINK1, respectively) drives conformational changes that enable it to bind and phosphorylate Ub and Parkin Ubl [70, 73–75]. In the structure of both apo- and AMP-PNP-bound TcPINK1, insert 3 is unstructured (Fig. 2a). Both structures are remarkably similar, except for two β-strands in the N-lobe that “clamp” on the nucleotide [73, 74]. The nucleotide-binding mode is very typical of protein Ser/Thr kinases, and implicates the invariant Lys196. It is also worth noting that in both structures, Ser205 was mutated to acidic residues, along with other mutations introduced to reduce heterogenous auto-phosphorylation. In the PhPINK1–Ub complex, insert 3 is folded and stabilized by phospho-Ser202 (Fig. 2b). Insert 3 interacts with Ub via a surface centered around Ile44, Gly47, and His68. Furthermore, the αC helix, a critical element of kinases’ active site that follows Ser202, undergoes a dramatic 90° rotation, which creates a new network of interactions that enables Ub binding. In addition, we have determined that PINK1 auto-phosphorylates exclusively in trans, which implies that at least two PINK1 molecules must first interact to phosphorylate Ser228 and enable Ub phosphorylation [70]. This is consistent with previous observations showing that PINK1 dimerizes and auto-phosphorylates as it builds on the OMM [51, 69]. S228A PINK1 thus emulates other kinase-dead mutants in cells, as it still localizes to mitochondria but cannot generate the pUb needed to recruit Parkin following CCCP treatment.

While these crystal structures have revealed important structural elements of PINK1 activity, many questions remain regarding PINK1 regulation. Notably, the structure and topology of PINK1 dimerization on the OMM still need to be reconciled. All insect PINK1 structures thus far truncate the N-terminus (i.e., removing the MTS, TMD and OMS) for heterologous purification, even though human PINK1 dimerizes and activates while its N-terminus is arrested in the TOM complex [51, 69]. All the crystallized PINK1 constructs thus far attach “back-to-back” via their CTE in an orientation that would not enable trans-autophosphorylation. As such, it remains to be seen how OMM-arrested PINK1 oligomerizes, along with how these missing N-terminal residues may regulate human PINK1 activation in the presence of TOM7. Another remaining question involves the binding of Parkin Ubl to PINK1. The Ub–PINK1 complex utilized a mutant Ub to stabilize its minor extended conformation, in which the side chain of Ser65 is exposed for phosphorylation. It remains to be seen whether Parkin Ubl will exhibit a similar conformation in the complex with PINK1, or whether it will bind through a different mechanism altogether.

Beyond its role as a ubiquitin kinase, PINK1 also has recently been suggested to phosphorylate proteins inside mitochondria, including NDUFA10 of RC complex I, as well as Mic60 of the MICOS complex [77, 78]. The topology of these potential interactions remains poorly understood: if the kinase domain of PINK1 is cytosolic [79], does pre-accumulated PINK1 phosphorylate these substrates as they are being imported, or is PINK1 capable of phosphorylating substrates within the IMS, or are these phosphorylation events somehow indirect? Recent work also suggests that PINK1 phosphorylates Larp in Drosophila to inhibit local protein translation in response to deleterious mtDNA mutations [80]. While this is an intriguing possibility, it has not yet been shown how PINK1 can engage physically with non-Ub substrates. It also emphasizes the ongoing shift in studying PINK1; as we better understand the molecular signals that control PINK1 import on the OMM and the subsequent activation, the spotlight will inevitably shift onto physiological substrates controlling wider aspects of mitochondrial quality control.

Mechanism of Parkin activation by PINK1

Soon after the discovery of Parkin, the protein was shown to bind E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes and catalyze Ub transfer to substrate proteins [10]. Ub conjugation confers a specific fate to the modified substrate and takes place via a cascade of enzymatic reactions. Ub is first activated by an E1 enzyme using ATP hydrolysis. Ub is then transferred to a cysteine acceptor group on an E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme, linked via a thioester bond to the C-terminal Gly76 of Ub. Finally, Ub is transferred to a primary amino group (lysine ε-amino or N-terminus) through the action of an E3 Ub ligase, which confers substrate specificity to the cascade. E3 ligases come in multiple flavors based on their domain structure and their biochemical mechanisms: (1) RING- or UBOX domain-containing ligases that facilitate transfer of Ub directly from the E2 to the substrate; (2) HECT domain-containing ligases that bear a cysteine acceptor site on which Ub is transferred prior to substrate ubiquitination; (3) RING-in-Between-RING (RBR) ligases, such as Parkin and HOIP, that have an E2-binding RING1 domain, an In-Between-RING (IBR), and a catalytic RING2 domain with a cysteine acceptor site for Ub [81]. In Parkin, the Ub acceptor site in RING2 (Cys431) is required for its ligase activity, and is also the site of a mutation (C431F) associated with one of the earliest onset forms of ARJPD [82], thus underlying the critical importance of Parkin’s ligase activity in PD pathogenesis.

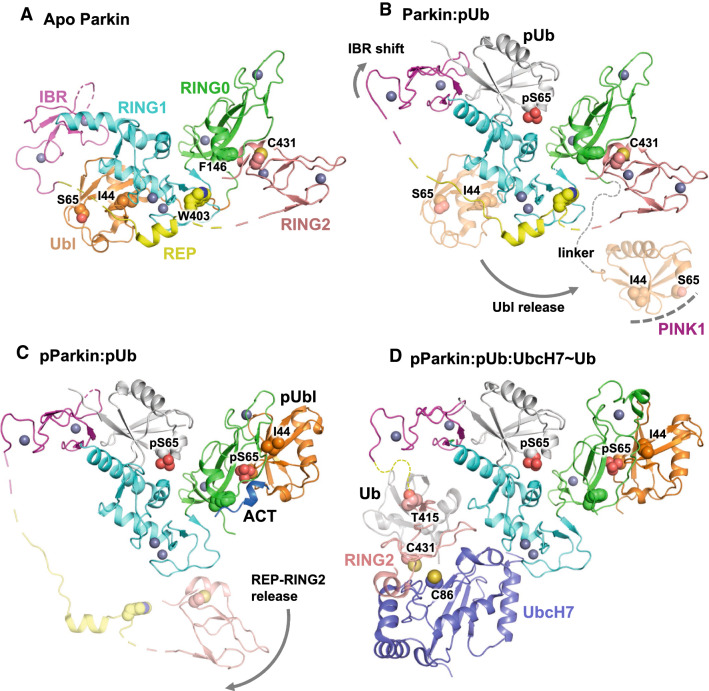

While Parkin demonstrates E3 ligase activity in vitro, its basal activity is low compared to other E3 ligases. Furthermore, it was observed that deletion of the Ubl domain leads to an increase in activity, suggesting that the Ubl plays a regulatory role [83]. The crystal structures of rat and human Parkin revealed three features that maintain autoinhibition [84–86]: (1) the linker between the IBR and RING2, which we named the repressor element of Parkin (REP), adopts a helical conformation that binds to RING1 and competes with E2 binding (Fig. 3a). (2) The Ubl domain also binds to RING1 at a site adjacent to the REP [85], which prevents E2 binding and does not allow PINK1 to engage the Ubl for phosphorylation [70, 87–89]. (3) Furthermore, a zinc finger domain unique to Parkin called RING0 or UPD binds to RING2 and occludes the active site Cys431, thus preventing thioester transfer. We and others have shown that Parkin can be activated by mutating residues in the REP motif (Trp403) as well as in at the RING0:RING2 interface (Phe146, Phe463) [84–86, 90]. Parkin is thus basally autoinhibited.

Fig. 3.

Structural model of Parkin activation by PINK1. a Structure of human Parkin in the apo, autoinhibited conformation (pdb 5C1Z, chain A). The domains colors are defined and maintained throughout the figure. Key residues such as the sites of activation by mutagenesis (Phe146, Trp403) are shown as spheres. Zinc atoms are shown as gray spheres. b Structure of human Parkin bound to pUb (pdb 5N2W). The binding of pUb induces a straightening of the last helix in RING1 and a movement of the IBR domain. This leads to the release of the Ubl domain (transparent cartoon), which exposes residues such as Ile44 that are essential for Ubl phosphorylation at Ser65 by PINK1. c Structure of human phospho-Parkin bound to pUb (pdb 6GLC). The structure shows pUbl and the ACT element bound to RING0 and competing with RING2, which is released along with the REP (transparent cartoon). d Structure of fly phospho-Parkin bound to pUb and UbcH7 (pdb 6DJW). The position of Ub tethered to UbcH7 (transparent gray) was modeled on the NMR-based model of Parkin bound to UbcH7~Ub (pdb 6N13). The RING2 domain was positioned such that the acceptor cysteine Cys431 is located near Cys86 in UbcH7, to which Ub is conjugated

PINK1 activates Parkin via two distinct steps. The first one is through its product pUb, which acts as a receptor for Parkin by binding with high affinity, with a equilibrium constant Kd around 400 nM for apo Parkin, and around 40 nM for phospho-Parkin or apo ΔUbl-Parkin [87–90]. The structures of insect and human Parkin bound to pUb showed that it binds to RING1 on the opposite side of the Ubl, while also making significant interactions with the IBR and RING0 domains [87, 88, 91–93]. In doing so, the last helix in RING1 goes from a kinked to a straight conformation, which leads to a significant shift in the position of the IBR (Fig. 3b). pUb binding then induces the dissociation of the Ubl [87, 94]; since the Ubl binds Parkin–RING1 and PINK1 via the same Ile44-centered surface, this pUb-induced dissociation is required for efficient Ubl phosphorylation [70, 95]. Antagonistic pUb and Ubl binding occur through subtle conformational changes at the RING1–IBR interface. Indeed, isothermal calorimetry titrations clearly shows that the IBR is required for binding to the Ubl domain [91], and thus repositioning of the IBR domain upon pUb binding would decrease the affinity for the Ubl. Furthermore, the Ubl-binding helix in RING1 is immediately followed by Arg275, which forms a salt bridge with Glu321 in the pUb-binding helix and may act as the allosteric linchpin. The R275W mutation is one of the most common ARJPD-associated variants and is impaired in mitophagy [50, 63], yet the mutation R275A does not abrogate pUb-binding [87]. Instead, this hints at an impairment downstream of pUb binding. Therefore, the function of pUb is to recruit Parkin to mitochondria and induce the dissociation and phosphorylation of the Ubl.

The second step of PINK1 activation of Parkin is the phosphorylation of Ser65 in the Ubl, which increases dramatically its ligase activity by enabling robust binding to E2 enzymes [87, 88, 90]. In 2018, two crystal structures of phospho-Parkin in complex with pUb revealed the conformational changes that enable activation [96, 97]. The structures showed that the phosphorylated Ubl domain (pUbl) binds to RING0 at a site that overlaps with the RING2-binding site in the inactive conformation (Fig. 3c, d). The phosphate group on Ubl–Ser65 notably interacts with Lys161 and Lys211, two sites that are mutated in ARJPD. In doing so, the pUbl domain favors a conformation where the RING2 domain dissociates, which concurrently leads to the dissociation of the REP motif. The structure of fly phospho-Parkin was determined in complex with both pUb and the E2 enzyme UbcH7 and confirmed that the E2 enzyme binds to RING1 at the Ubl and REP-binding site [96]. The structure is consistent with in vitro- and cell-based assays showing that Parkin can work with a subset of E2 enzymes that include UbcH7, Rad6 and UbcH5B [90, 98–100]. The structure of the human phospho-Parkin:pUb complex revealed a novel feature named the Activation element (ACT), which is located in the linker between the Ubl and RING0 and binds to a patch on RING0 adjacent to pUbl [97]. The ACT is unique to vertebrate Parkin, as opposed to the REP and all other domains that are conserved across metazoans. Thus, the ACT element does not appear to be essential for activation, but in vertebrates it may play an important role in stabilizing the active conformation. The function of the remaining part of the long (60 a.a.) Ubl–RING0 linker is less clear, but it may act as flexible arm that allows the Ubl to “reach out” to PINK1 following binding to pUb on mitochondria.

The current molecular model of Parkin activation by PINK1 is consistent with a number of observations in cells. The first one is the depletion of cytosolic Parkin following mitochondrial depolarization [17]. As PINK1 builds up on mitochondria, it phosphorylates Ub chains on OMM proteins, and these pUb chains recruit and activate Parkin, which then makes more Ub chains that are phosphorylated by PINK1, which recruit more Parkin, and so forth [90]. Thus, Parkin massively stimulates the formation of pUb on mitochondria. The model implies that the Ubl domain dissociates upon pUb binding, which suggests that pUb chains are present prior to Parkin activation. Indeed, pUb chains accumulate in HeLa cells without Parkin [101], and binding to these pre-existing pUb chains is required for Parkin phosphorylation [95]. The model is also consistent with data showing that TOM70–Ub4–PINK1 chimera can recruit catalytically dead C431S Parkin [102], that PINK1 targeted to the peroxisome can drive Parkin-dependent pexophagy [41], and that wild-type Parkin can induce the recruitment of C431S to mitochondria [103]. Finally, the activating mutations W403A and F146A rescue the activity of Parkin-S65A in mitophagy, in agreement with Ubl phosphorylation inducing the dissociation of the REP and RING2 [95]. Furthermore, these activating mutations can rescue a number of ARJPD mutations such as R42P, K211N, and R275W, which impair Ubl phosphorylation or pUbl binding, but not mutations such as G284R that impair pUb binding [104].

PINK1-independent regulation of Parkin’s ligase activity

One pending question is whether Parkin activity can be modulated independently of PINK1. Two groups reported that the c-Abl tyrosine kinase phosphorylates Parkin at Tyr143 [105, 106]. These studies reported that Tyr143 phosphorylation inhibited Parkin auto-ubiquitination, and that the c-Abl inhibitor imatinib thus increased Parkin’s activity. Intriguingly, Tyr143 is located at the interface of RING0, RING1, and RING2 in the autoinhibited conformation (Fig. 3a). A phosphate group on the side-chain hydroxyl of Tyr143 would create an electrostatic repulsion with the C-terminus of RING2, which would lead to its dissociation and potentially increase its activity. Furthermore, it is not known how c-Abl specifically phosphorylates Tyr143 or how it would inactivate Parkin. Another group reported that Polo-like kinase 1 (Plk1) phosphorylates Parkin at Ser378, which increases its activity and enables Parkin to ubiquitinate Cdh1 and Cdc20, which are coactivators of the anaphase-promoting complex involved in mitosis [107]. Ser378 is located at the end of the IBR domain, in the linker preceding the REP motif. It is unclear by which structural mechanism Ser378 phosphorylation would activate Parkin. Finally, Parkin was shown to protect neurons from apoptosis by stimulating linear polyUb chain formation on NEMO by HOIL/HOIP [108]. This causes activation of NF-κB and upregulation of OPA1, a mitochondrial GTPase that maintains cristae structure through membrane fusion. The effect is PINK1 independent, but how Parkin cooperates with the HOIL/HOIP complex remains unknown.

Mechanism of ubiquitin transfer by Parkin

Like other RBR E3 ligases, Parkin transfers Ub from an E2 to a substrate lysine in two distinct steps: (1) thioester Ub transfers from an E2 to a acceptor cysteine in the E3, and (2) acyl transfers to form a lysine–Ub isopeptide bond [81]. As evidence for this model, the C431S mutant of Parkin forms an oxyester intermediate with ubiquitin in cells and in vitro [86, 109]. Formation of this intermediate requires PINK1 activation, which infers that thioester transfer is the rate-limiting step. The double mutant W403A–C431S is also incapable of discharging an UbcH7~Ub conjugate, even though it binds the E2 well [85]. While there is no crystal structure of phospho-Parkin bound to a E2~Ub conjugate, NMR and HDX studies combined with docking show that the charged Ub moiety bind at the interface of the RING1 and IBR domains [110]. This is consistent with the crystal packing observed in the structure of the human Parkin:pUb complex, which revealed a cryptic Ub-binding site at this interface, involving notably Glu321 [91]. However, this does not imply that thioester transfer occurs in trans. Indeed, a complementation assay with rat Parkin mutants C431S and A240R, an E2-binding deficient mutant, disproves this hypothesis [96]. Furthermore, the ternary complex pParkin:pUb:UbcH7~Ub migrates as a single heterotrimer on size-exclusion chromatography [111], which is consistent with the thioester transfer taking place in cis. Comparison with other RBR E3 ligases strongly supports a model where RING2 directly interact with both the E2 and the charged Ub moiety. In the crystal structure of the HOIP-RBR:UbcH5B~Ub complex, the RING2 domain makes contact with both the E2 and Ub, which is itself also interacting with the RING1 and IBR domains [112]. NMR studies of the RING2 domain from HHARI shows that it binds to the Ile44-centered patch in Ub, using residues that are conserved in RBR ligases such as Thr341, which corresponds to the position of the ARJPD mutation T415N in Parkin [113, 114]. Thus, the structure of a pParkin:pUb:E2~Ub complex will likely reveal a conformation in which RING2 binds to E2~Ub, with the latter at the RING1–IBR interface, and Cys431 within a short distance of the active site Cys in the E2 to enable thioester transfer of Ub (Fig. 3d).

After Parkin has formed a thioester intermediate with Ub, it transfers the Ub carboxy terminus to the side chain ε-amino group of a lysine to form an isopeptide bond. Lysine side-chain amino groups typically have a pKa equal or greater than 9, which implies that they are protonated at neutral pH. As such, they are intrinsically poor nucleophiles and must be deprotonated to catalyze the formation of the isopeptide bond. In 2013, we thus hypothesized that this second step was catalyzed by His433, whose side chain would act as a general base towards an incoming lysine side chain [85]. The mutation H433A indeed reduces Parkin’s activity [84, 85]. In contrast, Riley et al. also showed that this mutant affects the nucleophilicity of Cys431, which should affect thioester transfer [86]. However, mutation of the equivalent residue in HOIP (H887A) leads to the accumulation of the thioester HOIP~Ub intermediate, which demonstrates unequivocally that this residue catalyzes acyl transfer by acting as a general base [115]. However, it remains unclear how Parkin positions a substrate lysine on RING2 to catalyze the formation of the isopeptide bond. This may vary according to the substrate.

Substrates of Parkin and downstream consequences

Defining the substrate(s) of Parkin in the context of PINK1 activation has proved to be difficult, in part because their identification depends on the model system under scrutiny and also because there is no strong evidence supporting a direct interaction between the ligase and its target(s). Nonetheless, some substrates prevail. In 2010, three studies reported that Parkin ubiquitinates mitofusin in Drosophila and its orthologs Mfn1/Mfn2 in mammalian cells [116–118]. Mitofusins are membrane-bound guanosine triphosphatase (GTPase) that promote mitochondrial membrane fusion by tethering two membranes [119]. The lab of Richard Youle reported that Mfn1/2 ubiquitination by Parkin leads to its degradation by the proteasome, following its extraction by the p97 segregase [116]. The loss of both Mfn1/2 leads to the loss of membrane fusion activity, which induces mitochondrial fission by other GTPases such Drp1. In mammals, Mfn2 also interacts with the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and through dimerization forms a tether at ER–mitochondria contact sites [120]. Recently, McLelland et al. showed that p97-dependent Mfn2 degradation by Parkin leads to the dissociation of ER–mitochondria contact sites [121]. In 2010, Geisler et al. found that Parkin ubiquitinates the voltage-dependent anion channel-1 (VDAC1), an abundant mitochondrial OMM ion channel that facilitates the exchange of ions and small molecules between the intermembrane space and the cytosol [63]. Thus, at the very least, Parkin targets Mfn1/2 and VDACs on the OMM.

The advent of proteomics studies revealed that Parkin ubiquitinates a very broad range of substrates on the OMM. Chan et al. used stable isotope labeling of amino acids in cell culture (SILAC) to measure changes in protein abundance on mitochondria following depolarization [122]. In addition to Mfn1/2, which show a marked decrease in abundance, the study also identified Miro1 as well as subunits of the TOM complex as substrates of Parkin. Miro1 is a GTPase that regulate mitochondrial transport by binding to the kinesin-binding protein Milton, and degradation of Miro1 by Parkin/PINK1 indeed causes mitochondrial arrest in neurons [123]. However, one caveat of monitoring protein abundance is that ubiquitination does not necessarily lead to degradation. In 2013, the group of Wade Harper performed proteomics on affinity-captured peptides with diglycine (diGly) motifs that remain following trypsin digest of Ub conjugates [124]. The method identified thousands of ubiquitination sites in various cell lines expressing endogenous Parkin. Sites common to all cell lines were found predominantly on OMM proteins such as VDAC1, Mfn1/2, CSID1 and HK1. It was later shown that efficient ubiquitination of those substrates requires Ub-Ser65 phosphorylation [111]. More recently, the same group used heavy isotope-labeled peptide derived from Parkin substrates to quantify dynamic changes in substrate ubiquitination and abundance. These changes were monitored in HeLa cells expressing endogenous levels of Parkin as well as two different types of neurons including dopaminergic neurons [31]. The study showed notably that overall levels of Parkin substrates do not change within the first hours following mitochondrial depolarization, which suggests that proteasomal degradation of Mfn1/2 may only take place when Parkin is overexpressed. One hour after depolarization with oligomycin A/antimycin A (OA), the most abundant Ub sites were found on the three VDAC isoforms, followed by Mfn2, CISD1, Miro1, HK1 and TOM20. However, if we consider the relative abundance of these proteins, two sites in Mfn2 and VDAC3 are by far the most targeted. Indeed, Mfn2 and VDAC3 are 100 and 4 times less abundant than VDAC1. Furthermore, 15 min after OA treatment, the abundance of Mfn2 ubiquitination at Lys416 is on par with the most targeted site on VDAC3 (Lys53), which implies that Mfn2 is a preferred substrate of Parkin.

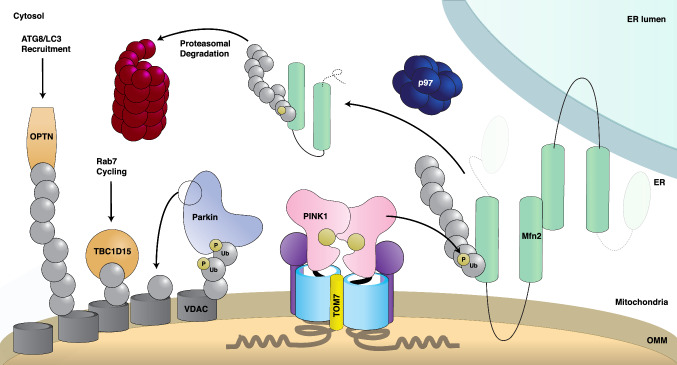

The structural basis for Parkin’s substrate recognition remains unclear, but the disparate nature of its substrates suggests that the ligase does not recognize a specific motif within the substrate itself. The group of Gerald Dorn reported that phosphorylated Mfn2 is the receptor for Parkin [125], but since Parkin can be recruited to mitochondria in Mfn1/2-double knockout (KO) mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) [17], Mfn2 is unlikely to be the direct receptor. Rather, Parkin would ubiquitinate any lysine in its proximity following activation, which would be conferred by binding to pUb tethered to OMM proteins including Mfn2. In support of this hypothesis, we find pUb in immuno-precipitated Mfn2 and conversely, we detect Mfn2 when we pull down pUb in U2OS cells expressing Parkin and treated with CCCP [121]. Since Mfn2 is located at the ER–mitochondria contact sites, it appears that PINK1 itself would build at these sites, which leads to the ubiquitination of the total pool of Mfn2, as observed [31, 95, 116, 121, 126]. Since proteins such as CISD1, TOM subunits, and VDACs are very abundant on the OMM, some will inevitably be found near PINK1, yet only a small fraction of the entire pool of each of those proteins are ubiquitinated by Parkin. Consistent with this model, native gel electrophoresis shows that PINK1 only binds to a fraction of the TOM import complexes [41]. Furthermore, FRET studies show that Parkin interacts with PINK1 and the TOM machinery, as well as 17-beta hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 10 (HSD17B10), a metabolic enzyme that regulates mitochondrial morphology [127]. Intriguingly, no interaction was detected between Parkin and VDAC1 by FRET, and the interaction of Parkin with HSD17B10 is Ub chain-dependent. Fractionation experiments show that PINK1 is enriched in mitochondria-associated membrane (MAM) fractions following 6 h of depolarization with CCCP, and Parkin colocalizes with HSPA9/GRP75, a protein found at MAM/ER–mitochondria contact sites [128]. Therefore, evidence is mounting for a model where Parkin targets proteins at ER–mitochondria contact sites, via PINK1/pUb-induced recruitment (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Schematic of Parkin activation and substrate ubiquitination on mitochondria. Representation of an ER–mitochondria contact site summarizing Parkin activation, ubiquitination of substrates, and its downstream consequences. TOM-arrested PINK1 oligomerizes, then phosphorylates ubiquitin on the OMM-localized proteins Mfn2 (right) and VDAC (left). These pUb chains recruit cytosolic Parkin (left), which continues to amplify this signal by transferring Ub from its active site Cys431 (shown as a circle on Parkin), onto substrate lysines. Ubiquitinated Mfn2 (right) recruits p97, which extracts Mfn2 from the OMM and permits its proteasomal degradation. PolyUb-VDAC (left) recruits the autophagy receptor OPTN, which in turn will catalyze autophagosome formation via recruitment of ATG8/LC3 and initiate subsequent mitophagy. DiUb-VDAC (left) is shown to recruit TBC1D15 to initiate Rab7 cycling

Polyubiquitin chain linkages, the proteasome and autophagy receptors

In addition to the ubiquitination of substrate proteins on the OMM, Parkin is also capable of synthesizing polyubiquitin (polyUb) chains. Ub has seven lysines (Lys6, 11, 27, 29, 33, 48 and 63) and an amino terminus (Met1), which can be conjugated to the C-terminus of another Ub moiety to form a polyUb chain. Early studies used Ub variants with lysine mutations to characterize polyUb linkages and found that Lys27- and Lys63-only Ub variants support PINK1-dependent mitophagy [63]. Using linkage-specific antibodies, Narendra et al. reported that Lys63–polyUb accumulates on depolarized mitochondria [129]. Early studies showed that Lys48 and Lys63-linked polyUb chains were enriched on mitochondria following depolarization, which leads to the recruitment of the 26S proteasome to mitochondria [122, 130]. Using absolute quantification (AQUA) of Ub peptides, Durcan et al. showed that Parkin makes mostly Lys6-linked polyUb in vitro (60%), as well as Lys11-, Lys48- and Lys63-linked polyUb [131]. AQUA Ub peptide quantification in cells show that Lys6 and Lys11-linked polyUb chains increase following OA treatment in a Parkin-dependent manner, but Lys48 and Lys63-linked polyUb chains increase a lot more [90], in agreement with previous findings [122]. Thus, Parkin can make almost any type of polyUb chains, which reinforces the notion that Parkin does not have substrate specificity and can modify any lysine depending on their accessibility following Parkin activation. However, only the complete replacement of Ub with K6R or K63R variants show a significant impairment in mitochondrial clearance, implying that not all chains made by Parkin have the same functional impact [111].

Given that different polyUb linkages impart different fates to their conjugated substrates, what is the outcome from the mix of linkage types made by Parkin? Lys48-linked polyUb binds strongly to receptors of the 26S proteasome such as Rpn10 and Rpn13, as well as ubiquitin-associated (UBA) shuttle proteins like HHR23 [132–134]. Since Parkin makes predominantly Lys48-linked polyUb in cells, the proteasome is recruited to mitochondria, which leads to the p97-dependent degradation of Mfn1/2 [116, 121, 122]. The loss of mitochondrial fusion activity leads to the isolation of damaged mitochondria and prevents their refusion with polarized (“healthy”) mitochondria [116]. Moreover, the loss of ER–mitochondria contacts caused by Mfn2 degradation facilitates the induction of mitophagy, and Parkin is recruited more rapidly in Mfn2-KO cells [121]. Experiments performed in ATG5-KO cells, or in cells lacking five autophagy receptors, show that Mfn1/2 degradation is independent of autophagy [122, 135]. Furthermore, Rpn13 binds to the Parkin Ubl domain, and knockdown of Rpn13 causes a delay in the clearance of mitochondria by autophagy, but yet does not affect Mfn1/2 degradation [136]. However, quantitative proteomics show that Mfn1/2 (as well as other OMM substrates) levels remain unchanged up to 4 h following OA treatment in HeLa cells or neurons expressing endogenous levels of Parkin [31]. This is consistent with previous observations showing that levels of OMM proteins do not change in cell lines with endogenous Parkin [126]. Since all studies that reported Mfn1/2 proteasome degradation were carried out in systems with Parkin overexpression, it suggests that this is an artifact, although we cannot exclude the possibility that degradation occurs locally and thus does not affect the bulk pool of Mfn1/2.

Another consequence of polyUb chain formation by Parkin is the recruitment of autophagy receptors. A number of groups reported that the protein p62 is recruited to depolarized mitochondria [63, 129, 137, 138]. p62, also known as sequestome-1 (SQSTM1), is a multidomain adaptor protein that contains a UBA domain that binds Lys63–polyUb chains, as well as a LC3-interacting region (LIR) that bind to members of the LC3/ATG8 family of ubiquitin-like modifiers that drive autophagy. However, p62 is not essential for mitophagy [129, 138]. Wong and Holzbaur also identified Optineurin (OPTN) as an autophagy receptor that is recruited to mitochondria through its Ub-binding UBAN domain [137]. OPTN recruits LC3 through its LIR motif and is required for mitochondrial clearance. Lazarou et al. conducted a systematic KO of five autophagy receptors (alone or in combination) and found that while no single KO affected mitophagy, the double KO of OPTN and NDP52 had the strongest effect, with the additional deletion of TAX1BP1 abolishing mitochondrial clearance completely [135]. Intriguingly, these receptors are also implicated in bacterial autophagy, which point to the common origin of bacteria and mitochondria [139]. Disruption of the Ub-binding UBAN and ZnF domains in OPTN and NDP52, respectively, could not rescue mitophagy, implying that Ub binding is required for the recruitment of the autophagy machinery. Furthermore, the OPTN mutant S177A, the main site of phosphorylation by TBK1, could not rescue mitophagy, implicating that TBK1 and OPTN cooperate to mediate Parkin/PINK1-dependent mitophagy. Heo et al. discovered that TBK1 was phosphorylated following OPTN binding to polyUb chains generated by Parkin, and conversely OPTN phosphorylation of the UBAN domain by TBK1 enhances polyUb binding [140]. The same group found that OPTN binds Lys63–polyUb, but not Lys48–polyUb nor monoUb [111]. Moreover, hyperphosphorylation of Lys63–polyUb by PINK1 decreases the affinity of those chains for OPTN [111] and delays mitophagy [31]. Indeed, only about 20% of Ub moieties in polyUb made by Parkin in HeLa cells are phosphorylated by endogenous PINK1. This most likely originates from its low abundance, and also because of its preference to phosphorylate the distal end of Ub chains, as the results of steric hindrance by the isopeptide bond on the proximal moieties [70, 141].

In parallel, polyUb chains synthesized by Parkin on mitochondria can also recruit RABGEF1, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor with a Ub-binding domain [142]. RABGEF1 then recruits and catalyze GDP/GTP exchange in Rab5, an endosomal Rab GTPase. In turn, Rab5 activates MON1/CCZ1, a Rab GEF for Rab7a, which is also recruited to mitochondria and anchors the OMM via its prenylation group. The mitochondrial Rab GTPase-activating proteins TBC1D15/D17 bind and cycle Rab7a, and initiate autophagosome formation through its interactions with LC3 family members [143]. RABGEF1, Rab5, Rab7a and TBC1D15/D17 are therefore required for mitophagy.

Regulation of Parkin by deubiquitinating enzymes and autoubiquitination

Like many E3 ubiquitin ligases, Parkin’s activity is also regulated by deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs). Ataxin-3, a DUB carrying a Josephin domain and whose mutations causes Machado–Joseph disease, was among the first Parkin DUB to be described, but the protein does not appear to regulate PINK1-dependent mitophagy [144, 145]. By contrast, at least five members of the Ub-specific cysteine protease (USP) family modulate Parkin/PINK1 activity. The best characterized is USP30, a mitochondrial DUB that antagonizes Parkin/PINK1 mitophagy in mammalian cells by deubiquitinating OMM substrates [146, 147]. The knockdown of USP30 can partially rescue the mitochondrial phenotype of PINK1 deletion in Drosophila, strongly suggesting the two proteins are functionally coupled. USP30 has a preference for Lys6–polyUb chains, and the structure of USP30 bound to Lys6–Ub2 revealed how the catalytic domain specifically engages both the proximal and distal Ub moieties to cleave the isopeptide bond [141, 148]. Since USP30 counteracts mitophagy, its specificity demonstrates that Lys6–polyUb chains are required to drive mitophagy [111]. In addition, the activity of USP30 is reduced when the distal Ub moiety is phosphorylated at Ser65, and thus it likely plays a predominant role in the early phase of Parkin activation. Depletion of USP30 has also been shown to increase basal PINK1-dependent mitophagy as well as pexophagy [149]. Like USP30, USP15 and USP35 also antagonize Parkin-dependent mitophagy. Intriguingly, USP35 resides on polarized mitochondria and dissociates upon depolarization [147]. In contrast with USP30, USP35 does not affect the rate of Parkin recruitment, and thus likely affects mitophagy through a distinct, yet unknown mechanism. USP15 is recruited to mitochondria following depolarization and removes both Lys48– and Lys63–polyUb chains from OMM substrates such as Mfn2 [150]. In Drosophila, knockdown of USP15 rescues the mitochondrial phenotype of Parkin deletion to a greater extent than the knockdown of USP30 [151].

On the other hand, knockdown of USP8 delays Parkin-dependent mitophagy in mammalian cells [131]. In vitro and in cells overexpressing Parkin, USP8 removes Lys6-linked polyUb chains on Parkin itself. Thus, removal of Lys6–polyUb on Parkin may be required for Parkin–PINK1 mitophagy. Using isotope-labeled peptides, the study also revealed that Parkin autoubiquitinates primarily in the Ubl domain on Lys48. Ubiquitination of Ubl–Lys48 would disrupt both binding to PINK1 and binding to the RING0 domain in the activated structure [70, 96]; therefore, by reducing Parkin’s autoubiquitination, USP8 would indeed increase Parkin’s activity. However, it is not known whether USP8 affects Parkin/PINK1 function through autoubiquitination in vivo. USP13 has also been reported to counteract Parkin’s E3 ligase activity, but it has not been studied in the context of PINK1-dependent mitophagy [152].

How Parkin autoubiquitination regulates its function in a physiological setting remains to be established. So far, Parkin autoubiquitination has only been observed in heterologous systems and depends on Parkin expression levels. Indeed, Rakovic et al. noted that in cell lines expressing low levels of Parkin, depolarization with valinomycin would lead to the ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of Parkin, which prevents induction of mitophagy [126]. However, this was not observed in neurons expressing endogenous levels of Parkin, which remain stable throughout depolarization-induced mitophagy [31]. Thus, even though structural work would predict that autoubiquitination might disrupt Parkin’s activity, this may be of no relevance if the protein does not self-modify under physiological conditions.

Physiological roles of Parkin/PINK1 in mitochondrial quality control, endolysosomal trafficking, and inflammation

While CCCP-induced depolarization was instrumental to discover the biochemical reactions carried out by Parkin and PINK1, this paradigm may only explain a narrow subset of the pair’s cellular roles. As an experimental model, the “brute force” depolarization caused by CCCP can also obscure more subtle functions of endogenous Parkin and PINK1, making it easy to overlook their involvement in physiological contexts. For instance, a study using Mito-KillerRed (Mito-KR), a light-excitable ROS-producing fluorescent protein, demonstrated that mitophagy can degrade “bits” of a mitochondrial network, depending on the proteasomal degradation of Mfn2 at ER–mitochondria contact sites [153]. Furthermore, Mito-KR was used to show that selective mitophagy can take place distally in the axon of neurons [154]. However, there are indications that suggest autophagy may not be a significant mechanism in vivo. Using pH-sensitive fluorescent reporters, a recent study showed that basal levels of mitophagy are largely unaffected in PINK1 KO mice [155], which bring forth two possibilities: first, there are other compensatory regulators of mitophagy, and second, the physiological roles of Parkin/PINK1 are more nuanced and context dependent than the mitophagy paradigm has led us to believe.

Puzzlingly, animal models with Parkin and PINK1 deletion lack nigrostriatal degeneration—the most prominent hallmark of PD in humans. Parkin and PINK1 KO mice exhibit mild deficits in dopamine release and striatal electrophysiology, yet their SNc DA neurons remain intact [18, 156]. Moreover, Parkin/PINK1-null Drosophila also exhibit motor defects without neurodegeneration [27–29]. This discrepancy between human PD pathology and Parkin/PINK1 animal models has been specifically reinforced by McWilliams et al., where Parkin S65A knock-in mice were devoid of PD nigrostriatal pathology, while human S65N homozygotes suffered from early-onset PD [157]. How do these KO animals avoid SNc neuron loss if Parkin and PINK1 mutations cause PD in humans? One consideration is that the accumulation of mitochondrial damage in aging humans may not be accurately represented by animals of a considerably shorter lifespan. A more relevant parameter might be the balance between mitochondrial burden and the rate of its clearance. To corroborate this, it has been shown that you can induce SNc DA neurodegeneration in Parkin KO mice subjected to a chronic mitochondrial stress, via a deleterious mutation of the mitochondrial DNA polymerase POLG that induces accumulation of mtDNA mutations [57]. This work suggests a “two-hit” model, where neuronal mitochondria may contain redundant lines of protection to compensate for PINK1 and Parkin at baseline or low levels of stress. In the presence of a second stressor, Parkin and PINK1 may then become indispensable for nigrostriatal survival.

These observations should not devalue or invalidate the molecular mechanisms of Parkin/PINK1 and their role in PD. The Springer lab demonstrated the presence of α-syn aggregates decorated with pUb spots in the brain of Lewy body disease patients, along with a general increase in pUb corresponding to age and disease progression [158]. This highlights that PINK1-dependent pUb is still a marker of processes associated with neurodegeneration. Furthermore, PINK1 KO (but not Parkin KO) rats do exhibit nigrostriatal degeneration [159], and thus there may be important differences in the neurophysiology of the SNc neurons between species that confer this phenotype. In the following sections, we highlight how different stress signals converge on Parkin and PINK1 to regulate their function, and reframe these consequences under the lens of DA neuron loss.

An important question is whether Parkin/PINK1-mediated mitochondrial protein turnover requires autophagy. In Drosophila, the turnover of a pool of mitochondrial proteins depended on parkin and pink1, but not on ATG7 (the E1 enzyme needed for autophagosome formation and activation of LC3) to be degraded. This pool of proteins was also found to be enriched with subunits of RC complexes [152]. These observations were among the first hints that Parkin and PINK1 mediate the selective turnover of mitochondrial proteins independently of autophagy [160]. One potential mechanism is through the formation of MDVs, which bud from mitochondria independently of the fission GTPase Drp1, and are produced in response to oxidative stress [161]. A subset of those MDVs is Parkin/PINK1 dependent and target cargo directly to lysosomes, using a machinery that includes the SNARE protein syntaxin-17 [32, 162]. In one sense, these MDVs serve as a defense mechanism to curtail mitochondrial damage at a “sub-mitophagy” threshold. Instead of irreversibly removing an entire mitochondrion, local Parkin and PINK1 rapidly respond to ROS levels and export damaged proteins directly to the lysosome. Consistent with this hypothesis, parkin and pink1 null flies accumulate unfolded RC complexes [163], which may have been prevented through the early removal of damaged RC subunits via MDVs.

Beyond mitochondrial quality control, the phenotypes of parkin and pink1 null flies have guided numerous other mechanistic and physiological studies. For instance, both parkin and/or pink1 null flies exhibited spermatid formation defects and muscle degeneration, along with a striking upregulation of genes involved in the innate immune response [27–29, 164]. Still, the mechanisms underlying the regulation of immunity have only recently emerged: PINK1 and Parkin were shown to inhibit the formation of MDVs required for mitochondrial antigen presentation (MitAP) in immune cells—a process in which major histocompatibility (MHC) class I peptides are sent to the cell surface to be recognized by T cells [26]. Parkin and PINK1 were proposed to suppress MitAP-containing MDVs by ubiquitinating and degrading Snx9, a trafficking protein involved in clathrin-mediated endocytosis, as well as Rab9, an important GTPase implicated in late endosome fusion. With this report, distinct pools of Parkin/PINK1 agonistic and antagonistic MDVs have emerged—future work will need to reconcile the mechanisms differentiating their production. An important hypothesis derived from this study is that PD caused by Parkin/PINK1 mutations would be an autoimmune disease. Intriguingly, PD shares common genomic risk loci with a number of autoimmune disorders, such as LRRK2, which has also been implicated in Crohn’s disease [165]. LRRK2 phosphorylates a number of Rab GTPases that are involved in the endolysosomal pathway [166]. Further work is required to understand the crosstalk between the Parkin/PINK1 and LRRK2 proteins in MitAP.

Parkin and PINK1 were also shown to mitigate inflammation—an important aspect of the innate immune response. Parkin/PINK1 KO mice subjected to exhaustive exercise or excessive mtDNA mutations produce inflammatory cytokines [24]. Human serum taken from mono and bi-allelic Parkin carriers also displayed elevated cytokine levels, including IL-6 and IL-1B. Moreover, cytokine production and SNc DA neuron loss was mitigated in Parkin/STING double KO mice, suggesting that STING-mediated inflammation is downstream of Parkin. The STING protein stimulates NF-κB transcription activity, following activation by cyclic-GAMP (cGAMP) [167]. Since the cGAMP synthase (cGAS) is activated by double-stranded DNA, one appealing hypothesis is that mtDNA from damaged mitochondria leaks into the cytosol and stimulates cGAMP production and NF-κB activation. Parkin deficiency has also been shown to down-regulate A20, an attenuator of the NF-κB and NLRP3 inflammasome [25]. The potential interplay between mitochondrial turnover and the NF-κB pathway needs to be explored, as well as the role of mtDNA leakage in generating the immune response.

Beyond autoimmunity, Parkin also has been shown to protect organisms from infection by intracellular bacterial pathogens, such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis. In macrophages, Parkin ubiquitinates bacterial machinery, targeting pathogens to the autophagosome through a process called xenophagy [22]. Indeed, Parkin levels in human macrophages, mice, and Drosophila directly affected the hosts’ susceptibility to M. tuberculosis infection. Notably, all Parkin KO mice died 85 days after infection, while WT mice remained completely healthy. This Parkin-mediated immunity may occur through conventional autophagy pathways, as Drosophila that harbored defective Atg8 processing and Atg5 knockdown in macrophages phenocopied Parkin-null animals. It remains unclear whether MDVs play a role in these routes of infection, but nonetheless, the effect of Parkin on immune surveillance has become unarguable. Given the genetic association between leprosy and the LRRK2 locus [168], there is evidently a strong association between pathogen susceptibility and biological processes involved in PD.

Some of the first clues hinting to this relationship came in 2004, when single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with a high risk of leprosy (caused by a Mycobacterium leprae infection) mapped to the 5′ promoter region of Parkin [23]. Intriguingly, Parkin shares this bidirectional promoter with PACRG (Parkin co-regulated gene), suggesting that their functions are coupled [169]. PACRG is a 30 kDa protein that is essential for the formation of a doublet microtubule structure called axoneme, which is an essential component of motile cilia and flagella [170, 171]. Primary cilia play an important role as a hub of cellular signaling [172, 173]. Mice lacking PACRG display hydrocephalus and defective spermatid maturation, caused by the loss of ventricular cilia and sperm flagella [174, 175]. While the potential function of PACRG in immunity remains uncharacterized, it is intriguing to find that Rab8 and Rab10, two Rab GTPases that are phosphorylated by the kinase domain of LRRK2, are implicated in the assembly of primary cilia [176]. PD mutations in LRRK2 increase its kinase activity towards Rab8/Rab10, which result in disrupted cilia formation and impaired Sonic Hedgehog signaling [177]. Coincidentally, the group of Miratul Muqit found that Rab8 is phosphorylated in a PINK1-dependent manner in response to CCCP-induced depolarization [178]. Given that Rab7 is required for the formation of mitochondria-lysosome contacts that regulate mitochondrial fission and recruitment of TBC1D15 [142, 179], these observations place Rab GTPases at the heart of pathways involved in PD and mitochondrial quality control.

Finally, we have shown 10 years ago that the Parkin Ubl binds to the endophilin-A1 SH3 domain, and that Parkin ubiquitinates proteins in complex with endophilin-A1 upon stimulation of kinase activity in synaptosomes [20]. Endophilin-A1 is a protein that regulates synaptic vesicle sorting to endosomes through its BAR domain, which binds curved lipid membranes, and its SH3 domain, which binds proline-rich motifs in proteins such as the phosphatidyl-inositol-phosphatase synaptojanin-1 [180–182]. Intriguingly, mutations in synaptojanin-1 cause ARJPD with seizures [183, 184], and the SH3GL2 gene, which encodes endophilin-A1, is a risk locus for PD [185, 186]. Parkin protein levels are elevated in the brain or fibroblast from endophilin-A1/2/3 KO mice, although the effect is mediated through transcription [187]. Fascinatingly, LRRK2 phosphorylates endophilin-A in the BAR domain, an event that regulates formation of autophagic membranes in synaptic boutons [188, 189]. Thus, by ubiquitinating endophilin-A1-associated proteins, Parkin may also regulate formation of autophagic membranes, which would affect mitochondrial autophagy as well. This is clearly an area that requires further investigation.

Future perspectives on Parkin/PINK1 involvement in Parkinson’s disease

Cellular studies clearly demonstrate that Parkin and PINK1 function together in response to some form of mitochondrial damage, be it mtDNA mutations, ROS, or depolarization. Biochemical and structural studies reinforced this functional link by showing how PINK1 builds up on damaged mitochondria and activates Parkin through Ub phosphorylation. At the physiological level, while animals lacking Parkin do not undergo nigrostriatal degeneration [18], they display defects in energy and lipid metabolism [21, 190], as well as impaired immunity [22, 24, 26], all of which are linked to mitochondrial dysfunction. Furthermore, several studies have shown that the DJ-1 protein, whose mutations also cause ARJPD [191], modulates the Parkin/PINK1 pathway through the regulation of mitochondrial ROS and glycolysis [192–194]. While the biochemical function of DJ-1 is still debated, its active site cysteine appears to be involved in scavenging oxidizing chemicals such as ROS, aldehydes, and glyoxals [195–197]. Therefore, mitochondrial dysfunction is strongly associated with PD.

Given that mitochondria are found in almost every one of our cells, why are mutations in Parkin/PINK1/DJ-1, as well as other PD genes, causing the loss of a selective subset of neurons? The Surmeier group proposed that the susceptibility of SNc DA neurons originates from their autonomous pacemaker activity and broad action potentials, which cause elevated cytosolic calcium levels and mitochondrial oxidative stress [198]. SNc DA and other susceptible neurons express L-type CaV1.3 channels, which give rise to calcium transients that are rapidly absorbed by mitochondria and cause ROS. In addition, these neurons display higher mitochondrial activity compared to other neurons, as well as increased axonal arborization, which further increase their vulnerability [199]. L-type channel blockers such as isradipine abrogate calcium entry, reduce basal mitochondrial oxidative stress, and rescue elevated mitochondrial stress in DJ-1 KO neurons [198]. Isradipine, which was developed as a treatment for high-blood pressure, is currently evaluated as a PD disease-modifying treatment in a Phase III clinical trial [200]. It is not known whether Parkin/PINK1-deficient neurons can also be rescued by isradipine. However, it is interesting to note that calcium is transferred from the mitochondria to the ER via contact sites, which are impaired in Parkin KO neurons and MEFs [201, 202]. Loss of Parkin thus impairs cytosolic calcium transients in a Mfn2-dependent manner. It is important to note here that this vulnerability model explains which neurons are affected in PD, but does not provide a mechanism for cell death. This is still subject to debate, but activation of immune cells in response to cytokines and MitAP may mediate the loss of those neurons in PD [26].

Future therapeutic strategies aimed at stimulating the Parkin/PINK1 pathway would quell mitochondrial dysfunction, attenuate the consequent immune response, and ultimately reduce the progressive neuron loss. We have shown that it is possible to rescue loss-of-function mutations in Parkin through synthetic activating mutations [104], which could be recapitulated by small molecules. Alternatively, it has been shown that PINK1 activity can be stimulated by kinetin triphosphate, a nucleotide that specifically binds to PINK1 and acts as a neo-substrate [203]. Because USP30 antagonizes Parkin/PINK1 mitophagy, there has also been considerable effort towards developing selective USP30 inhibitors as a potential treatment for PD [204]. Likewise, USP15 also antagonizes Parkin and is an important mediator of neuroinflammation, and thus, USP15 inhibitors should also be explored as PD drug candidates [205, 206]. Alternatively, immune cells could be targeted directly to reduce inflammation, either by targeting MitAP antigens or by inhibiting the cGAS/STING pathway [207]. Finally, we would like to point out that Parkin has also been implicated in cancers as a tumor suppressor [208, 209], and therefore treatments that stimulate this pathway may also be repurposed as cancer therapeutics.

An important point of contention in the field of PD is whether α-synuclein contributes to neuron loss via mitochondrial damage or other mechanisms. α-synuclein fibrils propagate in a stereotypical fashion through the PD brain, starting in the periphery and eventually reaching the cortex through the midbrain [210]. Gene triplication or missense dominant mutations in α-synuclein cause PD, clearly establishing a causal link between the two [7, 211]. However, it is unclear why synucleinopathy in PD specifically affects the same subset of vulnerable neurons as in Parkin/PINK1-caused ARJPD, whereas other neurons are affected in synucleinopathies such as dementia with Lewy bodies. This may be resolved by understanding the impact of α-synuclein on mitochondrial function, and the route through which Lewy bodies propagate. A number of studies have shown that α-synuclein oligomers/aggregates impair mitochondrial function by binding to the OMM and disrupting fusion/fission and protein import [212–214]. However, α-synuclein oligomers have also been shown to disrupt endolysosomal functions [215–217], which are essential for the turnover of damaged mitochondria. α-synuclein oligomers may therefore increase mitochondrial dysfunction by reducing the flux of damaged mitochondrial proteins through the lysosomes. In support of this hypothesis, genome-wide association studies and analysis of risk variants identified a number of genes implicated in endolysosomal and vesicle trafficking, such as GBA, LRRK2, VPS13C, VPS35, TMEM175, SH3GL2, and SMPD1 [185, 186, 218, 219]. Future work should continue to probe how α-synuclein aggregates modulate these pathways, as well as how mutations in PD genes affecting endolysosomal trafficking contribute to the disruption of mitochondrial protein turnover and the induction of an adverse immune response.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the members of the Trempe, Gehring, Fon and Durcan labs for stimulating discussions that forged our understanding of the Parkin/PINK1 pathway. A.B. is supported by a Healthy Brain for Healthy Lives—Canada First Research Excellence Fund (HBHL-CFREF) (No. 1c-II-5) studentship at McGill University. J.-F.T. is supported by a Tier 2 Canada Research Chair (No. 950-229792) and research grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (No. PJT-153274), Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (No. RGPIN-06497), Parkinson Canada (No. 2017-1277), the Michael J. Fox Foundation (No. 14681), and the HBHL-CFREF.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

ANB declares no conflicts of interest. J-FT is a consultant for Mitokinin Inc. and a founding member of M4ND Pharma Inc.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Spillantini MG, Schmidt ML, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ, Jakes R, Goedert M. Alpha-synuclein in Lewy bodies. Nature. 1997;388:839–840. doi: 10.1038/42166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Langston JW, Ballard PA., Jr Parkinson’s disease in a chemist working with 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,5,6-tetrahydropyridine. N Engl J Med. 1983;309:310. doi: 10.1056/nejm198308043090511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Langston JW, Ballard P, Tetrud JW, Irwin I. Chronic Parkinsonism in humans due to a product of meperidine-analog synthesis. Science. 1983;219:979–980. doi: 10.1126/science.6823561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schapira AH, Cooper JM, Dexter D, Jenner P, Clark JB, Marsden CD. Mitochondrial complex I deficiency in Parkinson’s disease. Lancet. 1989;1:1269. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)92366-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bender A, Krishnan KJ, Morris CM, Taylor GA, Reeve AK, Perry RH, Jaros E, Hersheson JS, Betts J, Klopstock T, Taylor RW, Turnbull DM. High levels of mitochondrial DNA deletions in substantia nigra neurons in aging and Parkinson disease. Nat Genet. 2006;38:515–517. doi: 10.1038/ng1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin I, Dawson VL, Dawson TM. Recent advances in the genetics of Parkinson’s disease. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2011;12:301–325. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-082410-101440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Polymeropoulos MH, Lavedan C, Leroy E, Ide SE, Dehejia A, Dutra A, Pike B, Root H, Rubenstein J, Boyer R, Stenroos ES, Chandrasekharappa S, Athanassiadou A, Papapetropoulos T, Johnson WG, Lazzarini AM, Duvoisin RC, Di Iorio G, Golbe LI, Nussbaum RL. Mutation in the alpha-synuclein gene identified in families with Parkinson’s disease. Science. 1997;276:2045–2047. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5321.2045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kitada T, Asakawa S, Hattori N, Matsumine H, Yamamura Y, Minoshima S, Yokochi M, Mizuno Y, Shimizu N. Mutations in the parkin gene cause autosomal recessive juvenile parkinsonism. Nature. 1998;392:605–608. doi: 10.1038/33416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang Y, Gao J, Chung KK, Huang H, Dawson VL, Dawson TM. Parkin functions as an E2-dependent ubiquitin- protein ligase and promotes the degradation of the synaptic vesicle-associated protein, CDCrel-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:13354–13359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.240347797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shimura H, Hattori N, Kubo S, Mizuno Y, Asakawa S, Minoshima S, Shimizu N, Iwai K, Chiba T, Tanaka K, Suzuki T. Familial Parkinson disease gene product, parkin, is a ubiquitin-protein ligase. Nat Genet. 2000;25:302–305. doi: 10.1038/77060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Valente EM, Abou-Sleiman PM, Caputo V, Muqit MM, Harvey K, Gispert S, Ali Z, Del Turco D, Bentivoglio AR, Healy DG, Albanese A, Nussbaum R, Gonzalez-Maldonado R, Deller T, Salvi S, Cortelli P, Gilks WP, Latchman DS, Harvey RJ, Dallapiccola B, Auburger G, Wood NW. Hereditary early-onset Parkinson’s disease caused by mutations in PINK1. Science. 2004;304:1158–1160. doi: 10.1126/science.1096284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paisan-Ruiz C, Jain S, Evans EW, Gilks WP, Simon J, van der Brug M, Lopez de Munain A, Aparicio S, Gil AM, Khan N, Johnson J, Martinez JR, Nicholl D, Carrera IM, Pena AS, de Silva R, Lees A, Marti-Masso JF, Perez-Tur J, Wood NW, Singleton AB. Cloning of the gene containing mutations that cause PARK8-linked Parkinson’s disease. Neuron. 2004;44:595–600. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zimprich A, Biskup S, Leitner P, Lichtner P, Farrer M, Lincoln S, Kachergus J, Hulihan M, Uitti RJ, Calne DB, Stoessl AJ, Pfeiffer RF, Patenge N, Carbajal IC, Vieregge P, Asmus F, Muller-Myhsok B, Dickson DW, Meitinger T, Strom TM, Wszolek ZK, Gasser T. Mutations in LRRK2 cause autosomal-dominant parkinsonism with pleomorphic pathology. Neuron. 2004;44:601–607. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Billingsley KJ, Bandres-Ciga S, Saez-Atienzar S, Singleton AB. Genetic risk factors in Parkinson’s disease. Cell Tissue Res. 2018;373:9–20. doi: 10.1007/s00441-018-2817-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Winklhofer KF. Parkin and mitochondrial quality control: toward assembling the puzzle. Trends Cell Biol. 2014;24:332–341. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Narendra D, Walker JE, Youle R. Mitochondrial quality control mediated by PINK1 and Parkin: links to Parkinsonism. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012;4:a011338. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a011338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Narendra D, Tanaka A, Suen DF, Youle RJ. Parkin is recruited selectively to impaired mitochondria and promotes their autophagy. J Cell Biol. 2008;183:795–803. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200809125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldberg MS, Fleming SM, Palacino JJ, Cepeda C, Lam HA, Bhatnagar A, Meloni EG, Wu N, Ackerson LC, Klapstein GJ, Gajendiran M, Roth BL, Chesselet MF, Maidment NT, Levine MS, Shen J. Parkin-deficient mice exhibit nigrostriatal deficits but not loss of dopaminergic neurons. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:43628–43635. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308947200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Esposito G, Ana Clara F, Verstreken P. Synaptic vesicle trafficking and Parkinson’s disease. Dev Neurobiol. 2012;72:134–144. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trempe JF, Chen CX, Grenier K, Camacho EM, Kozlov G, McPherson PS, Gehring K, Fon EA. SH3 domains from a subset of BAR proteins define a Ubl-binding domain and implicate parkin in synaptic ubiquitination. Mol Cell. 2009;36:1034–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim KY, Stevens MV, Akter MH, Rusk SE, Huang RJ, Cohen A, Noguchi A, Springer D, Bocharov AV, Eggerman TL, Suen DF, Youle RJ, Amar M, Remaley AT, Sack MN. Parkin is a lipid-responsive regulator of fat uptake in mice and mutant human cells. J Clin Investig. 2011;121:3701–3712. doi: 10.1172/JCI44736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]