Abstract

Programmed cell death (PCD) is a conserved phenomenon in multicellular organisms required to maintain homeostasis. Among the regulated cell death pathways, apoptosis is a well-described form of PCD in mammalian cells. One of the characteristic features of apoptosis is the change in cellular morphology, often leading to the fragmentation of the cell into smaller membrane-bound vesicles through a process called apoptotic cell disassembly. Interestingly, some of these morphological changes and cell disassembly are also noted in cells of other organisms including plants, fungi and protists while undergoing ‘apoptosis-like PCD’. This review will describe morphologic features leading to apoptotic cell disassembly, as well as its regulation and function in mammalian cells. The occurrence of cell disassembly during cell death in other organisms namely zebrafish, fly and worm, as well as in other eukaryotic cells will also be discussed.

Keywords: Apoptotic bodies, Extracellular vesicles, Apoptosis, Apoptosis-like PCD, Blebbing, Membrane protrusions

Cell disassembly in mammalian cells

Morphological changes for cell disassembly

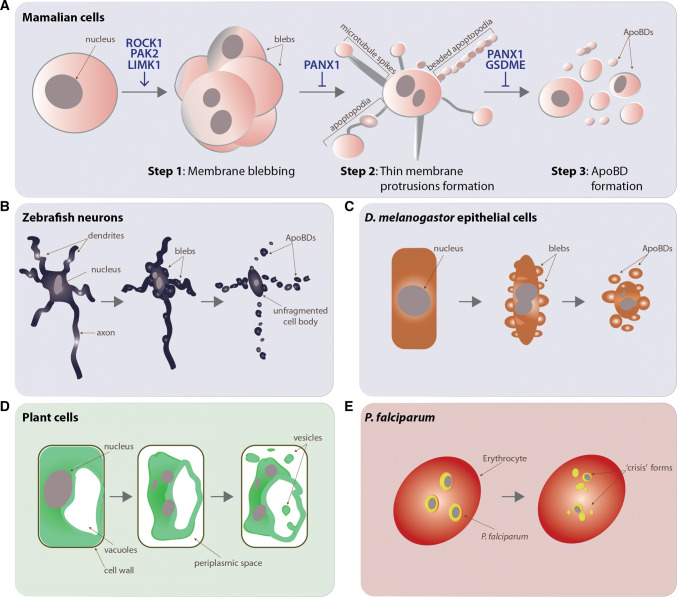

The cell exhibits an active display of morphological changes from the onset of apoptosis to its final removal by phagocytes through efferocytosis. The biochemical pathways controlling the apoptotic process are well described, but the factors driving the physical dismantling of the cell are still being characterized. While cell death was first described in the mid-nineteenth century [1], the term ‘apoptosis’ and disassembly of apoptotic cells forming smaller membrane-bound vesicles called apoptotic bodies (ApoBDs) was first coined by Kerr et al. [2]. While initially thought to be unregulated, we now understand that apoptotic cell disassembly is an ordered and regulated process orchestrated by caspase proteases and rearrangement of the cytoskeletal framework [3]. The progression of apoptotic cell disassembly is divided into three distinct morphological steps namely apoptotic membrane blebbing, thin membrane protrusion formation and ApoBD formation [3–5] (Fig. 1a). Membrane blebbing is observed as the circular bulging and retraction of the plasma membrane. This step initiates with smaller blebs occurring on the plasma membrane, also termed as surface blebs, followed by larger dynamic blebs that involve the entire volume of the cell [5]. The plasma membrane of apoptotic cells can further extend forming thin membrane protrusions [4, 6, 7]. There are three distinct apoptotic membrane protrusions described in literature namely microtubule spikes [7], apoptopodia [6] and beaded apoptopodia [4]. Microtubule spikes were noted by Moss et al. as tubulin-rich rigid spikes in human epithelial cells [7]. Apoptotic cells can also form string-like membrane protrusions termed apoptopodia. Often apoptopodia have a bleb-like structure at the distal end away from the cell body and are observed in cell types including human T cells, primary mouse thymocytes and mouse fibroblasts [6]. Furthermore, beaded apoptopodia were observed in both human monocytic cell lines and CD14+ primary monocytes. The term ‘beaded’ was used to describe these protrusions as they resemble ‘beads-on-a-string’ and can extend up to eight times the length of the dying cell [4]. The last step of disassembly is the fragmentation of the apoptotic cell forming discrete ApoBDs. The size of ApoBDs generally ranges from 1 to 5 μm, representing one of the largest types of extracellular vesicles [4]. Numerous types of cells including T cells [6], thymocytes [6, 8] monocytes [4], endothelial cells [9, 10], smooth muscle cells [5] as well as basal epithelial cells [11] can undergo disassembly during apoptosis to generate ApoBDs in vitro and/or in vivo [3]. In particular, recent use of intravital multiphoton microscopy has captured mouse germinal centre B cells undergoing apoptotic cell disassembly, with apoptotic B cells progressing from blebbing to ApoBD formation in vivo [12].

Fig. 1.

Cell death-associated disassembly features noted in cells from different organisms. a Apoptotic mammalian cells undergo a stepwise apoptotic cell disassembly process initiated by membrane blebbing (step 1), followed by thin membrane protrusion formation (step 2) leading to the fragmentation of the cell forming ApoBDs (step 3). Positive and negative regulators of apoptotic cell disassembly are noted for each step. b Developmental apoptosis in embryonic zebrafish neurons exhibit cell disassembly morphologies. c Morphogenesis-driven apoptosis of epithelial cells show cell disassembly during leg development in D. melanogaster. d Apoptotic-like PCD in plant cells show vesicle formation within the cell vacuole and into the periplasmic space. eP. falciparum undergo apoptotic-like PCD-associated fragmentation, forming membrane-bound vesicles called ‘crisis’ forms in red blood cells

Regulation of apoptotic cell disassembly

Apoptotic membrane blebbing is thought to be driven by a number of protein kinases, in particular rho associated kinase 1 (ROCK1), a serine threonine kinase activated by caspase 3 cleavage of its autoinhibitory domain [13, 14]. Upon activation during apoptosis, ROCK1 phosphorylates myosin light chain (MLC), driving actinomyosin contraction and membrane blebbing [13–15]. The role of ROCK1 in this process was demonstrated by pharmacological studies [13, 14, 16] and overexpression of active ROCK1 fragment [14]. Additionally, p21 kinase 2 (PAK2) has also been reported as a positive regulator of apoptotic membrane blebbing downstream of caspase activation [17, 18]. However, expression of the reported active PAK2 domain did not induce or affect blebbing [14]. Caspase 3 activation during apoptosis can further facilitate membrane blebbing by proteolytic processing and deactivating MYPT1, an MLC-binding subunit of myosin phosphatase that functions to dephosphorylate MLC [16]. Furthermore, LIM-kinase 1 (LIMK1) has also been shown to regulate blebbing by blocking the activity of cofilin, an actin depolymeriser [19]. Whether all these molecular factors are required to work in concert (or certain factors are redundant) to mediate apoptotic membrane blebbing remains to be defined. It is interesting to note that anucleate erythrocytes undergoing eryptosis (apoptotic-like cell death) also exhibit membrane blebbing driven by calcium-dependent proteolysis of the cytoskeleton network [20–23]. However, as eryptosis-associated membrane blebbing was shown to proceed with or without activation of caspase 3 [20, 24, 25], it would be of interest to examine if the above kinases driving apoptotic membrane blebbing in nucleated cells are also involved in membrane blebbing during eryptosis.

Thin apoptotic membrane protrusions are formed during or after membrane blebbing and a number of subtypes have been described [4, 6, 7]. First, rigid microtubule spikes were shown to be tubulin-rich structures that could form subsequent to blebbing in apoptotic human epithelial cells [7]. Tubulin filaments were observed to be disassembled early in apoptosis [26], however reorganization of tubulin forming an apoptotic microtubule network was noted at later stages of apoptosis [27, 28], which could aid membrane integrity by limiting caspase access to the cellular cortex [29]. Whether microtubule spikes are an extension of the apoptotic microtubule network or are independently formed structures remains to be defined. The other subtypes of apoptotic membrane protrusions, namely apoptopodia and beaded apoptopodia, were shown to be negatively regulated by pannexin 1 (PANX1) [4, 6]. PANX1 is a membrane channel that could become activated during apoptosis following caspase-mediated cleavage at its C-terminus. Interestingly, PANX1 also functions to release various molecules like ATP, which could act as a ‘find-me’ signal to mediate recruitment of macrophages for cell clearance [30, 31]. Although PANX1 can negatively regulate the generation of apoptopodia during apoptosis in a number of different cell types [4, 6], how PANX1 regulates apoptopodia formation and whether this is linked to the release of certain molecules via this channel is still unclear. Nevertheless, it should be noted that the formation of apoptopodia can be regulated by vesicular trafficking as determined by inhibitor studies [4], yet precisely which molecular components are involved and how this process is regulated requires further determination.

As described above, disassembly of apoptotic cells into ApoBDs involves the formation of plasma membrane blebs and thin membrane protrusions like apoptopodia. Thus, molecular regulators of these apoptotic morphologies, namely ROCK1 and PANX1, are also key regulators of ApoBD formation. In particular, the formation of ApoBD is negatively regulated by PANX1, whereby either inhibition of the channel pharmacologically, expression of a dominant negative mutant, or targeting PANX1 expression genetically, enhanced cell disassembly during apoptosis [4, 6]. Interestingly, gasdermin E (GSDME, also known as DFNA5) was also shown recently to negatively regulate ApoBD formation in human embryonic kidney cells and mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages [32]. During apoptosis, GSDME is activated by caspase 3-mediated cleavage and can subsequently localize to the plasma membrane to initiate secondary necrosis [32, 33]. As a consequence of secondary necrosis, intracellular contents including danger-associated molecular patterns such as double-stranded DNA can be released from cells [34]. Loss of GSDME expression in macrophages promoted the formation of ApoBDs, suggesting the early onset of secondary necrosis driven by GSDME limits the cell to undergo morphological changes necessary for apoptotic cell disassembly [32]. However, these studies on GSDME present an enigmatic process, as it does not align with the non-inflammatory nature of apoptotic cell death. Furthermore, given that ApoBD formation is noted in many in vitro and in vivo settings, what limits the function of GSDME in cells undergoing apoptotic cell disassembly is unclear. Therefore, while some of the regulators of apoptotic cell disassembly have been identified, the molecular mechanism underpinning the generation of ApoBDs, in particular the final separation of ApoBDs from the apoptotic cell body or other ApoBDs remains largely undetermined (Table 1).

Table 1.

Cell disassembly in different cell types undergoing cell death

| Organism | Cell type (tissue) | Cell death stimulus | Disassembly description | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human | T cells | Anti-Fas treatment or UV irradiation | Apoptotic cells first underwent cell rounding followed by dynamic membrane blebbing leading to ApoBD formation. Apoptopodia (thin string-like protrusion) were noted with inhibition of PANX1 function | [6] |

| Monocytes | UV irradiation or serum starvation | Apoptotic cells displayed dynamic blebbing with small bleb structures, followed by the formation of thin membrane extensions (apoptopodia) that exhibited a ‘beaded’ morphology. Two types of beaded apoptopodia were noted with uniform sized and non-uniform-sized vesicles along the length of the membrane protrusion. Detachment of these vesicles from the cell/protrusions generated ApoBDs | [4] | |

| Endothelial cells | UV irradiation or serum starvation and tumour necrosis factor-alpha treatment | ApoBDs expressing same surface markers as viable endothelial cells were noted | [9, 10] | |

| Epithelial cells | UV irradiation | Apoptotic cells displayed dynamic membrane blebbing followed by the formation of rigid microtubule-rich membrane protrusions or ‘spikes’ with a vesicle-like structure at the distal end. Detachment of these vesicles from microtubule spikes to form ApoBDs was observed | [7] | |

| Mouse | Thymocytes | Dexamethasone treatment | Apoptotic cells showed dynamic membrane | [6] |

| B cells (lymph nodes) | Immunization with NP15-OVA and HIV envelope antigen | Bleb formation and cell fragmentation was noted in apoptotic cells | [12] | |

| Rat | Thymocytes | X-irradiation (whole body) | Apoptotic cells and apoptotic cell fragments (ApoBDs) with round morphology and smooth surfaces were noted | [8] |

| Zebrafish | Embryonic cells (cell type and tissue unknown) | Camptothecin treatment | Apoptotic cells showed transient blebbing prior to nuclear fragmentation | [65] |

| Endothelial cells | Embryonic development | Apoptotic cells showed membrane blebbing and ApoBD formation | [66] | |

| Lens retinal cells | Embryonic development | Apoptotic cells showed large membrane blebs and fragmentation | [67] | |

| Neurons | Embryonic development or UV ablation |

Apoptotic cells showed cell body rounding with fragmentation of axon and dendrites Anterograde blebbing followed by axonal fragmentation was noted in apoptotic cells |

[67, 68] | |

| D. melanogaster | Embryonic cells (epidermal layer) | Embryonic development or X-irradiation | Apoptotic cells exhibited extensive membrane blebbing and fragmentation into ApoBDs | [80] |

| Embryonic cells (cell type and tissue unknown) | DAKT mutation | Ectopic apoptotic cells displayed membrane blebbing | [82] | |

| Epithelial cells (leg) | Morphogenesis | Apoptotic cells exhibited membrane blebbing and ApoBD formation | [84, 85] | |

| Squamous cells (imaginal discs) | Morphogenesis | ApoBD generated from apoptotic cells were noted to accumulate in the columnar epithelium | [86] | |

| Nurse cells (ovaries) | Oogenesis, etoposide or staurosporine treatment |

Single membrane-bound vesicles containing fragmented DNA were noted Small vesicles containing chromatin from apoptotic cells were detected in egg chambers |

[88] | |

| C. elegans | Neurons | Developmental | Apoptotic cells showed membrane vesicularization and fragmentation | [99] |

| Tomato | Cells from seedlings (cell type and tissue unknown) | Fumonisin B1 treatment | ApoBD-like vesicles were noted from protoplasts of cells undergoing apoptotic-like PCD | [110] |

| Tobacco | Suspension cells (cell type and tissue unknown) | Heat (55 °C) treatment | ApoBD-like vesicles were noted 24 h post heat treatment | [112] |

| Wheat | Parenchymal cells (coleoptile) | Ageing | Cytoplasmic bodies were noted budding into the vacuole region of dying cells containing mitochondria and plastids | [118] |

| Cells unknown (leaf apical area) | Ageing | Vesicles containing mitochondria were noted in the vacuole region of cells undergoing apoptotic-like PCD | [118] | |

| Pepper | Mesophyll cells (leaf) | Bacterial race 2 infection | Spherical membranous bodies noted in vacuoles of cells undergoing apoptotic-like PCD | [119] |

| T. brucei | n/a | Con A treatment | Membrane vesicularization (blebbing) noted 3 h post-cell death stimulus | [140] |

| T. cruzi | n/a | Treatment with geneticin (G418), staurosporine or sera (containing complement), and nutrient deficiency (non-renewal of growth media) driven differentiation | Dying organisms examined by electron microscopy show extensive membrane blebbing | [135] |

| P. berghei | n/a | Life cycle driven | Membrane blebbing and bodies (ApoBD-like) noted in organisms undergoing apoptotic-like PCD | [147] |

| P. falciparum | n/a | Treated with sera from individuals living in malarial infected regions, chloroquine or etoposide treatment |

Fragmentation of the organism, generating ‘crisis forms’ noted Formation of membrane-bound fragments or ‘crisis forms’ can be blocked by pan caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMD |

[146, 150] |

Function of apoptotic cell disassembly

Apoptotic cells are removed from the tissue via efferocytosis by either neighbouring or immune cells. Defects in the timely clearance of apoptotic cells allow them to proceed to secondary necrosis, which is linked to the development of a number of diseases [3, 34–37]. For example, impaired apoptotic cell clearance in mouse models presented with lupus-like autoimmune features [38]. In humans, sera of a subset of patients with the autoimmune disorder systemic lupus erythematosus contained elevated levels of apoptotic debris and autoantibodies to intracellular moieties [39–41]. Moreover, studies in mouse models linked impaired cell clearance to inflammation associated with colitis [42]. Uncleared apoptotic debris accumulation in atherosclerotic plaques has also been shown to drive inflammation via macrophage and T cell recruitment [43, 44]. Thus, efficient clearance of apoptotic cells is imperative to maintain tissue homeostasis. To ensure rapid removal of apoptotic debris, the dying cell can promote phagocyte recruitment and recognition by the release/exposure of ‘find-me’ and ‘eat-me’ signals, respectively [36, 37]. In addition to these mechanisms, the disassembly of apoptotic cells can also aid cell clearance. For instance, apoptotic membrane blebs are known to harbour endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membranes. The active shuttling of ER was observed in membrane bleb regions [40] and ER membranes were also noted on the outer bleb surfaces that can expose molecules capable of mediating phagocyte recognition [45]. In particular, the exposure of calreticulin (an ER membrane protein) facilitated the binding of C1q and mannose-binding lectin to apoptotic cells and promoted macrophage recognition [46, 47]. Furthermore, pharmacological inhibition of membrane blebbing in apoptotic T cells reduced their uptake by monocyte-derived macrophages [48], supporting the concept that morphological changes during apoptosis could aid the cell clearance process. However, this latter study did not address the mechanism of how apoptotic membrane blebbing is linked to engulfment. Interestingly, ApoBD formation was shown to facilitate efferocytosis, whereby blocking apoptotic neuronal cell fragmentation pharmacologically decreased the engulfment of apoptotic materials by monocyte-derived macrophages [49]. Additionally, the formation of apoptotic membrane protrusions like microtubule spikes in epithelial cells were shown to provide extended surfaces to facilitate their interaction with phagocytes and further aiding cell clearance [7]. Whether the generation of other types of thin apoptotic membrane protrusions like apoptopodia and beaded apoptopodia may also promote phagocyte interaction remains to be defined.

In addition to cell clearance, disassembly of apoptotic cells can also facilitate intercellular communication via ApoBDs harbouring biomolecules like DNA and protein [3, 4, 50]. The DNA contained in ApoBDs has been shown to facilitate horizontal gene transfer, whereby Epstein–Barr virus DNA carrying lymphoid cells were able to distribute viral DNA into ApoBDs and their uptake by foetal fibroblasts resulted in the integration and expression of Epstein–Barr viral proteins in the recipient cell [51]. Similarly, oncogenes were also shown to be transferred via ApoBDs from H-rasV12 and human c-myc transfected rat fibroblasts to recipient mouse embryonic fibroblasts to propagate tumorigenicity in the latter [52]. Endothelial cell-derived ApoBD were also noted to harbour the proinflammatory cytokine interleukin 1 alpha, which when added to viable endothelial cells induced secretion of interleukin 18 and monocyte chemotactic protein-1 [10]. Additionally, ApoBDs generated from epithelial cells carrying alpha-fodrin and Sjögren’s syndrome-related antigen A were shown to induce secretion of proinflammatory cytokines tumour necrosis factor alpha and interleukin 8 from recipient dendritic cells [53]. Together, these examples show that biomolecules carried by ApoBDs can play a number of roles in both physiological and disease settings.

Cell disassembly in zebrafish

The use of zebrafish as a model organisms has numerous advantages especially the ease of genetic manipulation and in vivo imaging in the transparent embryos (reviewed in [54]), providing an unparalleled system to study both physiological and pathological processes [55–58]. The study of apoptosis is of particular interest as the zebrafish has a conserved canonical apoptotic pathway to mammals (reviewed in [59]). Notably, zebrafish pro-apoptotic proteins were functional in mammalian cells whereby expression of zebrafish Bcl-2-associated death promoter (bad) induced DNA fragmentation and chromatin condensation in monkey kidney fibroblast-like cells [60]. Additionally, BH3-only peptides from zebrafish bim, noxa and puma promoted cytochrome c release from mitochondria isolated from mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) but not from mitochondria isolated from Bax and Bak double-knockout MEFs, indicating zebrafish BH3-only peptides interact with murine pro-apoptotic proteins [61]. More importantly, zebrafish executioner caspases have conserved protein substrates to their mammalian homologs [62, 63] whereby recombinant zebrafish caspase 3a showed high cleavage activity toward the DEVD peptide sequence, similar to caspase 3 and 7 in mammals [64].

The apoptotic cell disassembly process can be observed in a variety of cell types in zebrafish. For example, camptothecin-induced apoptosis in deep cell layer of zebrafish embryos revealed cells undergoing surface membrane blebbing [65]. Furthermore, endothelial cells undergoing apoptosis during pruning of brain blood vessels showed blebbing and cell fragmentation, which were subsequently cleared by microglial cells [66]. Additionally, in vivo imaging of apoptotic cells in the anterior brain of the zebrafish during embryonic development revealed apoptotic lens retina and transganglion cells undergoing blebbing and cell fragmentation forming ApoBD-like vesicles [67]. Zebrafish neurons undergoing apoptosis during embryogenesis also displayed certain cell disassembly morphologies, in which spinal cord interneuron cell body exhibited rounding while the dendrites and axon simultaneously fragmented and readily disappeared (perhaps through clearance), leaving the cell body behind [67] (Fig. 1b). A similar process of apoptotic cell disassembly was observed in UV-ablated neurons in zebrafish embryos at 2–4 days post-fertilization, where the cell showed anterograde (from cell body to axons and dendrites) blebbing and axonal fragmentation. Additionally, the cell body (soma) was cleared by microglia-mediated engulfment over several hours [68].

Similar to mammalian cells, ROCK1 is essential for apoptotic membrane blebbing in zebrafish cells, in which pharmacological inhibition of ROCK1 in whole embryos using Y-27632 reduced blebbing in apoptotic neural tube cells [69]. Notably, zebrafish ROCK1 protein has a conserved caspase 3 cleavage site as mammalian ROCK1, suggesting that zebrafish ROCK1 may also be activated during apoptosis via caspase-mediated cleavage in a similar manner to its mammalian homolog. Interestingly, ROCK1-mediated membrane blebbing in apoptotic neural tube cells during embryonic development promoted directional migration of these cells from the apical region to the central nervous system periphery (basolateral side), which assisted their clearance by microglia [69]. While the mechanism underlying the fragmentation of apoptotic cells in zebrafish is not well defined, a number of cell types in zebrafish also express PANX1 [70], a negative regulator of ApoBD formation in mammalian cells as described above [4, 6]. Furthermore, the caspase cleavage site characterized in mammalian PANX1 [31], is also conserved in zebrafish. Thus, it would be of interest to examine if zebrafish PANX1 functions in a conserved role in apoptotic cell disassembly. Overall, zebrafish cells show many conserved morphological, regulatory and functional aspects of apoptotic cell disassembly to mammalian cells and would be a useful model to further study this process.

Cell disassembly in D. melanogaster

D. melanogaster is a commonly used model to study the cell death process as apoptosis is important throughout the fly life cycle from embryogenesis to the adult form [71], and the role of caspases in apoptosis of metazoans is conserved [72]. In D. melanogaster, seven caspases orchestrate apoptotic cell death (reviewed in [71, 73]). Among these caspases, drICE is the key executioner caspase and is functionally similar to mammalian caspase 3 [71, 74]. Multiple other apoptotic signalling molecules are also conserved between D. melanogaster and mammals (reviewed in [75]), including Dronc (homolog of caspase 9) [76] and Ark (homolog of Apaf-1) [77]. Moreover, D. melanogaster Bok expression in human embryonic kidney cells induced cytochrome c release and apoptosis similar to mammalian pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family members [78].

While the disassembly of apoptotic cells is typically not studied using the D. melanogaster model, cellular morphologies associated with cell disassembly were observed in various studies and often used as a hallmark of apoptotic cell death [79]. During embryogenesis, apoptotic cells in the epidermal layer showed fragmentation into ApoBDs as observed by confocal and electron microscopy [80], and these ApoBDs were also observed within phagocytic vesicles of hemocytes and neighbouring cells [80, 81]. Furthermore, embryo expressing mutants of D. melanogaster AKT (protein kinase B, a pro-survival protein) showed increase in apoptosis and dying cells exhibited apoptotic membrane blebbing [82]. Another phase of large turnover of cells in D. melanogaster by various cell death pathways including apoptosis is morphogenesis [71, 83, 84]. Time-lapse imaging of apoptotic epithelial cells in the developing leg during morphogenesis showed membrane blebbing and subsequent cell fragmentation forming distinct ApoBDs [84, 85] (Fig. 1c). Likewise, ApoBDs were also observed from squamous cell apoptosis in imaginal wing disc during morphogenesis [86]. Furthermore, during oogenesis in the adult fly, ex vivo examination of ovaries showed apoptotic nurse cells undergoing blebbing and fragmentation into ApoBDs [87, 88].

The cytoskeletal machinery is important for apoptotic cell disassembly in mammalian cells [13, 14, 89]. In D. melanogaster, cytoskeletal rearrangements forming actin bundling is noted in apoptotic nurse cells during oogenesis, but its function is not defined [87]. Ectopic induction of apoptosis in the wing disc also showed stabilization of filamentous actin in dying cells [84]. It is also interesting to note that one of the key drivers of apoptotic membrane blebbing in mammalian cells, myosin II [13, 14, 89], is also activated downstream of the pro-apoptotic protein reaper in D. melanogaster [84]. While the role of myosin II is described during morphogenesis in D. melanogaster [84, 86, 90], its activation is also noted in non-morphogenetic apoptosis [79] and may potentially drive apoptotic membrane blebbing. Although it is unclear if the disassembly of apoptotic cells aids cell clearance in D. melanogaster, injured and degenerated neurons were fragmented by filamentous actin structures in neighbouring epidermal epithelial cells prior to their engulfment by the latter [91]. Interestingly, this process is also observed in mammalian tissue where adipocytes are fragmented and cleared by multiple macrophages in mice [92], yet the role of phagocytes in assisting the apoptotic cell disassembly process to aid cell clearance is not well understood. Multiple questions remain undefined regarding the disassembly of apoptotic cells in D. melanogaster, in particular the underpinning molecular mechanism and the function of this process throughout the life cycle.

Cell disassembly in C. elegans

Pioneering work using C. elegans as a model organism uncovered many molecular mechanisms and regulation of apoptotic cell death [93], including genes that control the execution of apoptosis (ced-3, ced-4, ced-9, and egl-1) as well as recognition and removal of apoptotic cells (ced-1, ced-2, ced-5, ced-6, ced-7, ced-10 and ced-12) (reviewed in [94]). During development in C. elegans, apoptosis is pre-programmed where invariably 131 cells out of a total 1090 cells will die by this process [95–97]. Morphologically, these apoptotic cells became refractive as determined by Nomarski (differential interference confocal) microscopy [98]. Detailed examination of an apoptotic nerve cell in the ventral nerve cord showed whirling of internal and external membranes, followed by loss of cell shape and formation of membrane-bound remains [99]. Fragmentation of late apoptotic cells were also noted when genes namely ced-5, ced-6, ced-7 and ced-10 involved in cell clearance were mutated [100]. Thus, while fragmentation of dying cells is evident in C. elegans, the morphological steps of apoptotic cell disassembly including membrane blebbing and thin protrusion formation were not observed. Interestingly, the lack of clear morphological features during apoptosis may be linked to how apoptotic cells are cleared in C. elegans. Cell engulfment in C. elegans has been shown to actively promote apoptosis, whereby worms harbouring mutations in any engulfment gene reduced the number of cells proceeding to apoptosis [101, 102]. Furthermore, apoptotic cells can be cleared prior to any observable morphological features [101]. Thus, it is likely that apoptotic cell disassembly is not needed in C. elegans as the cell clearance process is efficient and/or early engulfment of the apoptotic cell does not leave sufficient time for most cells to disassemble.

Cell disassembly in other organisms

While apoptotic pathways are well described in metazoans, similar pathways termed apoptosis-like PCD are also characterized in plants, fungi and Protista. This section will discuss the cellular morphology associated with apoptosis-like PCD and drawing parallels to the mammalian apoptotic cell disassembly process.

Cell disassembly in plants?

Programmed cell death in plants is characterized into three categories, namely apoptotic-like PCD, senescence and, vacuole-mediated cell death [103]. In metazoans, apoptosis is a caspase-dependent process, whereas no caspases have been identified in plants. However, other caspase-like proteases and metacaspases are shown to drive apoptotic-like PCD in plants [103]. The terminology ‘apoptotic-like’ to describe this process including the functional similarity of metacaspases to caspases is still a topic of debate [103–105]. Interestingly, expression of anti-apoptotic proteins such as human Bcl-2, chicken Bcl-xL and C. elegans CED-9 in tobacco plants conferred resistance to herbicide-induced cell death [106], and expression of pro-apoptotic murine Bax in tobacco plants was able to induce hypersensitive response (apoptosis-like PCD surrounding viral-infected cells) [107]. While these suggest some conservation, however, as the molecular machinery driving apoptosis-like PCD in plants is not fully defined [103, 108, 109], it is uncertain how these overexpression studies relate to apoptosis described in metazoans.

Interestingly, plants including tomato (root, stem, cotyledon tissues and suspension cell cultures) [110], carrot (embryonic cells from hypocotyl explants) [111], tobacco (leaf disc and suspension cell culture) [110, 112], mustard (suspension cell culture) [113] and sunflower (anther) [114] showed cells undergoing apoptotic-like PCD exhibited features similar to apoptosis when induced in culture, but also during development and in response to pathogens (reviewed in [103, 115]). These features include shrinking of the cell away from the cell wall and membrane blebbing [111], DNA condensation and laddering [110–112], cytochrome c release [113, 114] and, loss of membrane asymmetry and exposure of phosphatidylserine [116, 117]. The fragmentation of the dying plant cell into membrane-bound vesicles akin to ApoBDs have been observed in tomato seedlings treated with mycotoxin and in heat (55 °C) treated tobacco cell cultures [110, 112]. However, these observations have not been reported in whole plant tissue [103]. Additionally, vesicles containing organelles including the mitochondria are seen budding into the vacuole space of wheat leaf and coleoptile cells undergoing ageing-driven apoptotic-like PCD when examined by electron microscopy [118] (Fig. 1d). Similar vesicles were also observed in pepper leaf cells infected with bacterial race 2 to cause hypersensitive cell death [119]. As to how and why these cells undergo fragmentation in plants is uncertain given that the cell clearance process is not evident and probably not necessary in plant tissue. Moreover, the presence of the cell wall hinders interaction with neighbouring cells, thus limiting the possibility of these plant-derived vesicles mediating intercellular communication. However, plant cells have been reported to secrete and deliver exosome-like extracellular vesicles containing small RNA to invading fungal pathogen cells [120], thus the cell wall may not be completely impermeable to the trafficking of extracellular vesicles. A number of questions including the regulation of apoptotic-like PCD still need to be characterized before we begin to unfold the role of these associated morphological features in plants.

Cell disassembly in fungi?

Apoptosis has been described in a number of fungal species, with the majority of studies focussing on yeast models including S. cerevisiae and the pathogenic C. albicans [121, 122]. Apoptosis in yeast is dependent on a number of regulators including metacaspase yCa1p, an ortholog of mammalian caspases [123, 124]. Moreover, study of apoptosis in yeast has served as a model to study human diseases including neurodegeneration, cardiovascular disease and cancer [124–127].

Apoptosis in yeast shows a number of features that are similar to mammalian cells undergoing apoptosis. These include the condensation of chromatin, DNA fragmentation, externalization of phosphatidylserine, and depolarization of the mitochondrial matrix [128, 129]. However, morphological changes associated with mammalian apoptotic cell disassembly are absent. Notably, apoptotic yeast cells displayed enlargement rather than cell shrinkage as observed in mammalian apoptosis [128]. Interestingly, tiny buds containing chromatin have been noted on the apoptotic cell plasma membrane, which were suggested to be precursors of vesicles like ApoBDs [129]. However, it should be noted that these tiny buds on the plasma membrane did not separate from the dying cell [129]. It is also worth noting that yeast undergoing cell death can release factors such as nutrients that can promote survival of other cells in the colony [130, 131], but unlike multicellular organisms there may be no need for these factors to be packaged into membrane-bound vesicles.

Cell disassembly in Protista (Protozoa)

A number of protozoans have been reported to exhibit apoptosis-like PCD [132–134] and much of our understanding of this process comes from the studies of parasitic protozoans including Trypanosoma [135–140], Leishmania [141–144], Plasmodium [145–147] and Toxoplasma [148, 149]. Factors that could promote apoptotic-like PCD in these organisms including density control, immune silencing, differentiation and stress response [133]. The molecular mechanism underpinning apoptosis-like PCD in protozoans involves metacaspases and has been suggested to have divergently evolved to apoptosis in mammals [132]. Interestingly, apoptotic features such as cell shrinkage, chromatin condensation, DNA fragmentation, loss of mitochondrial membrane potential and externalization of phosphatidylserine are noted in protozoans undergoing apoptotic-like PCD [132–134].

In addition to apoptotic features mentioned above, morphological changes similar to certain stages of mammalian apoptotic cell disassembly are also observed in protozoans. T. brucei treated with Con A to induce apoptotic-like PCD showed surface membrane vesicularization (resembling blebbing) [140]. T. cruzi undergoing cell death in vitro during differentiation and induction by treatments including complement containing sera also showed membrane blebbing when examined by electron microscopy [135]. Additionally, electron micrographs of P. berghei ookinetes undergoing apoptosis-like PCD in vivo (midgut of A. stephensi) or in vitro cultures showed membrane blebs and the presence of ApoBD-like vesicles [147]. Furthermore, when examining immune sera-induced apoptosis-like PCD in P. falciparum within erythrocytes (ex vivo), ‘crisis form’ characterized by disintegration of the parasite were noted [150]. These disintegrated fragments or ‘crisis forms’ were also observed with etoposide- and chloroquine-induced P. falciparum cell death, and were suggested to be related to ApoBDs generated from mammalian cells [146, 151] (Fig. 1e). Notably, the generation of these ‘crisis forms’ by P. falciparum undergoing apoptotic-like PCD could be blocked by the pan caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK [146]. Although the function of this cell disassembly process in protozoans is not well defined, it is suggested—that packaging of pathogen cell contents by vesicle formation may prevent direct presentation of antigen to the host cell [151]. Thus, understanding how and why these parasitic protozoans disassemble during apoptosis-like PCD may provide novel therapeutic targets to treat parasitic infections.

Concluding remarks

It is evident that features of cell disassembly are noted in cells from various organisms undergoing apoptosis or apoptotic-like PCD. These observations however raise several intriguing questions including how the disassembly of dying cells is regulated and whether this is a conserved phenomenon or if this process is independently developed through convergent evolution. Moreover, the formation of ApoBDs and similar vesicles has been shown to play physiologically relevant roles in mammals. Thus, it would be of interest to further study the role of dying cell disassembly in processes such as cell clearance and intercellular communication in other organisms.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Poon Laboratory for discussion. This work was supported by Grants from the National Health & Medical Research Council of Australia (GNT1125033 and GNT1140187) to I.K.H.P.

Contributor Information

Rochelle Tixeira, Email: rtixeira@students.latrobe.edu.au.

Ivan K. H. Poon, Email: i.poon@latrobe.edu.au

References

- 1.Clarke PGH, Clarke S. Nineteenth century research on cell death. Exp Oncol. 2012;34(3):139–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kerr JF, Wyllie AH, Currie AR. Apoptosis: a basic biological phenomenon with wide-ranging implications in tissue kinetics. Br J Cancer. 1972;26(4):239–257. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1972.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atkin-Smith GK, Poon IKH. Disassembly of the dying: mechanisms and functions. Trends Cell Biol. 2017;27(2):151–162. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2016.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atkin-Smith GK, Tixeira R, Paone S, Mathivanan S, Collins C, Liem M, et al. A novel mechanism of generating extracellular vesicles during apoptosis via a beads-on-a-string membrane structure. Nat Commun. 2015;6(1):7439. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tixeira R, Caruso S, Paone S, Baxter AA, Atkin-Smith GK, Hulett MD, et al. Defining the morphologic features and products of cell disassembly during apoptosis. Apoptosis. 2017;22(3):475–477. doi: 10.1007/s10495-017-1345-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poon IKH, Chiu Y-H, Armstrong AJ, Kinchen JM, Juncadella IJ, Bayliss DA, et al. Unexpected link between an antibiotic, pannexin channels and apoptosis. Nature. 2014;507(7492):329–334. doi: 10.1038/nature13147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moss DK, Betin VM, Malesinski SD, Lane JD. A novel role for microtubules in apoptotic chromatin dynamics and cellular fragmentation. J Cell Sci. 2006;119(11):2362–2374. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohyama H, Yamada T, Ohkawa A, Watanabe I. Radiation-induced formation of apoptotic bodies in rat thymus. Radiat Res. 1985;101(1):123. doi: 10.2307/3576309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiang L, Paone S, Caruso S, Atkin-Smith GK, Phan TK, Hulett MD, et al. Determining the contents and cell origins of apoptotic bodies by flow cytometry. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):14444. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-14305-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berda-Haddad Y, Robert S, Salers P, Zekraoui L, Farnarier C, Dinarello CA, et al. Sterile inflammation of endothelial cell-derived apoptotic bodies is mediated by interleukin-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011;108(51):20684–20689. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116848108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mesa KR, Rompolas P, Zito G, Myung P, Sun TY, Brown S, et al. Niche-induced cell death and epithelial phagocytosis regulate hair follicle stem cell pool. Nature. 2015;522(7554):94–97. doi: 10.1038/nature14306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mayer CT, Gazumyan A, Kara EE, Gitlin AD, Golijanin J, Viant C, et al. The microanatomic segregation of selection by apoptosis in the germinal center. Science. 2017;358(6360):eaao2602. doi: 10.1126/science.aao2602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sebbagh M, Renvoizé C, Hamelin J, Riché N, Bertoglio J, Bréard J. Caspase-3-mediated cleavage of ROCK I induces MLC phosphorylation and apoptotic membrane blebbing. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:346. doi: 10.1038/35070019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coleman ML, Sahai EA, Yeo M, Bosch M, Dewar A, Olson MF. Membrane blebbing during apoptosis results from caspase-mediated activation of ROCK I. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3(4):339–345. doi: 10.1038/35070009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amano M, Ito M, Kimura K, Fukata Y, Chihara K, Nakano T, et al. Phosphorylation and activation of myosin by Rho-associated kinase (Rho-kinase) J Biol Chem. 1996;271(34):20246–20249. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.34.20246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Croft DR, Coleman ML, Li S, Robertson D, Sullivan T, Stewart CL, et al. Actin-myosin-based contraction is responsible for apoptotic nuclear disintegration. J Cell Biol. 2005;168(2):245–255. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200409049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rudel T, Bokoch GM. Membrane and morphological changes in apoptotic cells regulated by caspase-mediated activation of PAK2. Science. 1997;276(5318):1571–1574. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5318.1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee N, MacDonald H, Reinhard C, Halenbeck R, Roulston A, Shi T, et al. Activation of hPAK65 by caspase cleavage induces some of the morphological and biochemical changes of apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1997;94(25):13642–13647. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tomiyoshi G, Horita Y, Nishita M, Ohashi K, Mizuno K. Caspase-mediated cleavage and activation of LIM-kinase 1 and its role in apoptotic membrane blebbing. Genes Cells. 2004;9(6):591–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1356-9597.2004.00745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bratosin D, Estaquier J, Petit F, Arnoult D, Quatannens B, Tissier J-P, et al. Programmed cell death in mature erythrocytes: a model for investigating death effector pathways operating in the absence of mitochondria. Cell Death Differ. 2001;8(12):1143–1156. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lang E, Qadri SM, Lang F. Killing me softly—suicidal erythrocyte death. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2012;44(8):1236–1243. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2012.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lang F, Gulbins E, Lang PA, Zappulla D, Föller M. Ceramide in suicidal death of erythrocytes. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2010;26(1):21–28. doi: 10.1159/000315102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qadri SM, Bissinger R, Solh Z, Oldenborg P-A. Eryptosis in health and disease: a paradigm shift towards understanding the (patho)physiological implications of programmed cell death of erythrocytes. Blood Rev. 2017;31(6):349–361. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2017.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lang F, Qadri SM. Mechanisms and significance of eryptosis, the suicidal death of erythrocytes. Blood Purif. 2012;33(1–3):125–130. doi: 10.1159/000334163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mandal D, Moitra PK, Saha S, Basu J. Caspase 3 regulates phosphatidylserine externalization and phagocytosis of oxidatively stressed erythrocytes. FEBS Lett. 2002;513(2–3):184–188. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(02)02294-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mills JC, Lee VM, Pittman RN. Activation of a PP2A-like phosphatase and dephosphorylation of tau protein characterize onset of the execution phase of apoptosis. J Cell Sci. 1998;111:625–636. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.5.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sánchez-Alcázar JA, Rodríguez-Hernández Á, Cordero MD, Fernández-Ayala DJM, Brea-Calvo G, Garcia K, et al. The apoptotic microtubule network preserves plasma membrane integrity during the execution phase of apoptosis. Apoptosis. 2007;12(7):1195–1208. doi: 10.1007/s10495-006-0044-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oropesa-Ávila M, de la Cruz-Ojeda P, Porcuna J, Villanueva-Paz M, Fernández-Vega A, de la Mata M, et al. Two coffins and a funeral: early or late caspase activation determines two types of apoptosis induced by DNA damaging agents. Apoptosis. 2017;22(3):421–436. doi: 10.1007/s10495-016-1337-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oropesa-Ávila M, Fernández-Vega A, de la Mata M, Maraver JG, Cordero MD, Cotán D, et al. Apoptotic microtubules delimit an active caspase free area in the cellular cortex during the execution phase of apoptosis. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4(3):e527. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elliott MR, Chekeni FB, Trampont PC, Lazarowski ER, Kadl A, Walk SF, et al. Nucleotides released by apoptotic cells act as a find-me signal to promote phagocytic clearance. Nature. 2009;461(7261):282–286. doi: 10.1038/nature08296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chekeni FB, Elliott MR, Sandilos JK, Walk SF, Kinchen JM, Lazarowski ER, et al. Pannexin 1 channels mediate “find-me” signal release and membrane permeability during apoptosis. Nature. 2010;467(7317):863–867. doi: 10.1038/nature09413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rogers C, Fernandes-Alnemri T, Mayes L, Alnemri D, Cingolani G, Alnemri ES. Cleavage of DFNA5 by caspase-3 during apoptosis mediates progression to secondary necrotic/pyroptotic cell death. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14128. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Y, Gao W, Shi X, Ding J, Liu W, He H, et al. Chemotherapy drugs induce pyroptosis through caspase-3 cleavage of a gasdermin. Nature. 2017;547(7661):99–103. doi: 10.1038/nature22393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muñoz LE, Lauber K, Schiller M, Manfredi AA, Herrmann M. The role of defective clearance of apoptotic cells in systemic autoimmunity. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010;6(5):280–289. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shao W-H, Cohen PL. Disturbances of apoptotic cell clearance in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13(1):202. doi: 10.1186/ar3206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nagata S. Apoptosis and clearance of apoptotic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2018;36(1):489–517. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-042617-053010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Poon IKH, Lucas CD, Rossi AG, Ravichandran KS. Apoptotic cell clearance: basic biology and therapeutic potential. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14(3):166–180. doi: 10.1038/nri3607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Potter PK, Cortes-Hernandez J, Quartier P, Botto M, Walport MJ. Lupus-prone mice have an abnormal response to thioglycolate and an impaired clearance of apoptotic cells. J Immunol. 2003;170(6):3223–3232. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.6.3223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baumann I, Kolowos W, Voll RE, Manger B, Gaipl U, Neuhuber WL, et al. Impaired uptake of apoptotic cells into tingible body macrophages in germinal centers of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(1):191–201. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200201)46:1<191::AID-ART10027>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Casciola-Rosen LA, Anhalt G, Rosen A. Autoantigens targeted in systemic lupus erythematosus are clustered in two populations of surface structures on apoptotic keratinocytes. J Exp Med. 1994;179(4):1317–1330. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.4.1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Williams RC, Malone CC, Meyers C, Decker P, Muller S. Detection of nucleosome particles in serum and plasma from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus using monoclonal antibody 4H7. J Rheumatol. 2001;28(1):81–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee CS, Penberthy KK, Wheeler KM, Juncadella IJ, Vandenabeele P, Lysiak JJ, et al. Boosting apoptotic cell clearance by colonic epithelial cells attenuates inflammation in vivo. Immunity. 2016;44(4):807–820. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Björkerud S, Björkerud B. Apoptosis is abundant in human atherosclerotic lesions, especially in inflammatory cells (macrophages and T cells), and may contribute to the accumulation of gruel and plaque instability. Am J Pathol. 1996;149(2):367–380. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shah PK, Falk E, Badimon JJ, Fernandez-Ortiz A, Mailhac A, Villareal-Levy G, et al. Human monocyte-derived macrophages induce collagen breakdown in fibrous caps of atherosclerotic plaques. Potential role of matrix-degrading metalloproteinases and implications for plaque rupture. Circulation. 1995;92(6):1565–1569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lane JD, Allan VJ, Woodman PG, Rodriguez-Boulan E, Kreibich G. Active relocation of chromatin and endoplasmic reticulum into blebs in late apoptotic cells. J Cell Sci. 2005;118(Pt 17):4059–4071. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ogden CA, deCathelineau A, Hoffmann PR, Bratton D, Ghebrehiwet B, Fadok VA, et al. C1q and mannose binding lectin engagement of cell surface calreticulin and CD91 initiates macropinocytosis and uptake of apoptotic cells. J Exp Med. 2001;194(6):781–795. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.6.781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Korb LC, Ahearn JM. C1q binds directly and specifically to surface blebs of apoptotic human keratinocytes: complement deficiency and systemic lupus erythematosus revisited. J Immunol. 1997;158(10):4525–4528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Witasp E, Uthaisang W, Elenström-Magnusson C, Hanayama R, Tanaka M, Nagata S, et al. Bridge over troubled water: milk fat globule epidermal growth factor 8 promotes human monocyte-derived macrophage clearance of non-blebbing phosphatidylserine-positive target cells. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14(5):1063. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Orlando KA, Stone NL, Pittman RN. Rho kinase regulates fragmentation and phagocytosis of apoptotic cells. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312(1):5–15. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lynch C, Panagopoulou M, Gregory CD. Extracellular vesicles arising from apoptotic cells in tumors: roles in cancer pathogenesis and potential clinical applications. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1174. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Holmgren L, Szeles A, Rajnavölgyi E, Folkman J, Klein G, Ernberg I, et al. Horizontal transfer of DNA by the uptake of apoptotic bodies. Blood. 1999;93(11):3956–3963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bergsmedh A, Szeles A, Henriksson M, Bratt A, Folkman MJ, Spetz AL, et al. Horizontal transfer of oncogenes by uptake of apoptotic bodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(11):6407–6411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.101129998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ainola M, Porola P, Takakubo Y, Przybyla B, Kouri VP, Tolvanen TA, et al. Activation of plasmacytoid dendritic cells by apoptotic particles—mechanism for the loss of immunological tolerance in Sjögren’s syndrome. Clin Exp Immunol. 2018;191(3):301–310. doi: 10.1111/cei.13077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pyati UJ, Look AT, Hammerschmidt M. Zebrafish as a powerful vertebrate model system for in vivo studies of cell death. Semin Cancer Biol. 2007;17(2):154–165. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dai Y-J, Jia Y-F, Chen N, Bian W-P, Li Q-K, Ma Y-B, et al. Zebrafish as a model system to study toxicology. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2014;33(1):11–17. doi: 10.1002/etc.2406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Norton W, Bally-Cuif L. Adult zebrafish as a model organism for behavioural genetics. BMC Neurosci. 2010;11(1):90. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-11-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dooley K, Zon LI. Zebrafish: a model system for the study of human disease. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2000;10(3):252–256. doi: 10.1016/S0959-437X(00)00074-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bakkers J. Zebrafish as a model to study cardiac development and human cardiac disease. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;91(2):279–288. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Eimon PM, Ashkenazi A. The zebrafish as a model organism for the study of apoptosis. Apoptosis. 2010;15(3):331–349. doi: 10.1007/s10495-009-0432-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hsieh Y-C, Chang M-S, Chen J-Y, Jong-Young Yen J, Lu I-C, Chou C-M, et al. Cloning of zebrafish BAD, a BH3-only proapoptotic protein, whose overexpression leads to apoptosis in COS-1 cells and zebrafish embryos. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;304(4):667–675. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(03)00646-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jette CA, Flanagan AM, Ryan J, Pyati UJ, Carbonneau S, Stewart RA, et al. BIM and other BCL-2 family proteins exhibit cross-species conservation of function between zebrafish and mammals. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15(6):1063–1072. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Negron JF, Lockshin RA. Activation of apoptosis and caspase-3 in zebrafish early gastrulae. Dev Dyn. 2004;231(1):161–170. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Alexander Valencia C, Bailey C, Liu R. Novel zebrafish caspase-3 substrates. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;361(2):311–316. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.06.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yabu T, Kishi S, Okazaki T, Yamashita M. Characterization of zebrafish caspase-3 and induction of apoptosis through ceramide generation in fish fathead minnow tailbud cells and zebrafish embryo. Biochem J. 2001;360(Pt 1):39–47. doi: 10.1042/bj3600039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ikegami R, Hunter P, Yager TD. Developmental activation of the capability to undergo checkpoint-induced apoptosis in the early zebrafish embryo. Dev Biol. 1999;209(2):409–433. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang Y, Xu B, Chen Q, Yan Y, Du J, Du X. Apoptosis of endothelial cells contributes to brain vessel pruning of zebrafish during development. Front Mol Neurosci. 2018;11:222. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.van Ham TJ, Mapes J, Kokel D, Peterson RT. Live imaging of apoptotic cells in zebrafish. FASEB J. 2010;24(11):4336–4342. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-161018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Morsch M, Radford R, Lee A, Don EK, Badrock AP, Hall TE, et al. In vivo characterization of microglial engulfment of dying neurons in the zebrafish spinal cord. Front Cell Neurosci. 2015;9:321. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.van Ham TJ, Kokel D, Peterson RT. Apoptotic cells are cleared by directional migration and elmo1—dependent macrophage engulfment. Curr Biol. 2012;22(9):830–836. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kurtenbach S, Prochnow N, Kurtenbach S, Klooster J, Zoidl C, Dermietzel R, et al. Pannexin1 channel proteins in the zebrafish retina have shared and unique properties. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e77722. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Denton D, Aung-Htut MT, Kumar S. Developmentally programmed cell death in Drosophila. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. 2013;1833(12):3499–3506. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Degterev A, Boyce M, Yuan J. A decade of caspases. Oncogene. 2003;22(53):8543–8567. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.White K, Grether ME, Abrams JM, Young L, Farrell K, Steller H. Genetic control of programmed cell death in Drosophila. Science. 1994;264(5159):677–683. doi: 10.1126/science.8171319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fraser AG, Evan GI. Identification of a Drosophila melanogaster ICE/CED-3-related protease, drICE. EMBO J. 1997;16(10):2805–2813. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.10.2805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fuchs Y, Steller H. Programmed cell death in animal development and disease. Cell. 2011;147(4):742–758. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dorstyn L, Colussi PA, Quinn LM, Richardson H, Kumar S. DRONC, an ecdysone-inducible Drosophila caspase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(8):4307–4312. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rodriguez A, Oliver H, Zou H, Chen P, Wang X, Abrams JM. Dark is a Drosophila homologue of Apaf-1/CED-4 and functions in an evolutionarily conserved death pathway. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1(5):272–279. doi: 10.1038/12984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhang H, Huang Q, Ke N, Matsuyama S, Hammock B, Godzik A, et al. Drosophila pro-apoptotic Bcl-2/Bax homologue reveals evolutionary conservation of cell death mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(35):27303–27306. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002846200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Monier B, Suzanne M. The morphogenetic role of apoptosis. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2015;114:335–362. doi: 10.1016/bs.ctdb.2015.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Abrams JM, White K, Fessler LI, Steller H. Programmed cell death during Drosophila embryogenesis. Development. 1993;117(1):29–43. doi: 10.1242/dev.117.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tepass U, Fessler LI, Aziz A, Hartenstein V. Embryonic origin of hemocytes and their relationship to cell death in Drosophila. Development. 1994;120(7):1829–1837. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.7.1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Staveley BE, Ruel L, Jin J, Stambolic V, Mastronardi FG, Heitzler P, et al. Genetic analysis of protein kinase B (AKT) in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 1998;8(10):599–603. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(98)70231-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Domsch K, Papagiannouli F, Lohmann I. The HOX—apoptosis regulatory interplay in development and disease. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2015;114:121–158. doi: 10.1016/bs.ctdb.2015.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Monier B, Gettings M, Gay G, Mangeat T, Schott S, Guarner A, et al. Apico-basal forces exerted by apoptotic cells drive epithelium folding. Nature. 2015;518(7538):245–248. doi: 10.1038/nature14152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Schott S, Ambrosini A, Barbaste A, Benassayag C, Gracia M, Proag A, et al. A fluorescent toolkit for spatiotemporal tracking of apoptotic cells in living Drosophila tissues. Development. 2017;144(20):3840–3846. doi: 10.1242/dev.149807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Aldaz S, Escudero LM, Freeman M. Live imaging of Drosophila imaginal disc development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(32):14217–14222. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008623107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nezis IP, Stravopodis DJ, Papassideri I, Robert-Nicoud M, Margaritis LH. Stage-specific apoptotic patterns during Drosophila oogenesis. Eur J Cell Biol. 2000;79(9):610–620. doi: 10.1078/0171-9335-00088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Foley K, Cooley L. Apoptosis in late stage Drosophila nurse cells does not require genes within the H99 deficiency. Development. 1998;125(6):1075–1082. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.6.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mills JC, Stone NL, Erhardt J, Pittman RN. Apoptotic membrane blebbing is regulated by myosin light chain phosphorylation. J Cell Biol. 1998;140(3):627–636. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.3.627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sherrard K, Robin F, Lemaire P, Munro E. Sequential activation of apical and basolateral contractility drives ascidian endoderm invagination. Curr Biol. 2010;20(17):1499–1510. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.06.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Han C, Song Y, Xiao H, Wang D, Franc NC, Jan LY, et al. Epidermal cells are the primary phagocytes in the fragmentation and clearance of degenerating dendrites in Drosophila. Neuron. 2014;81(3):544–560. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Murano I, Barbatelli G, Parisani V, Latini C, Muzzonigro G, Castellucci M, et al. Dead adipocytes, detected as crown-like structures, are prevalent in visceral fat depots of genetically obese mice. J Lipid Res. 2008;49(7):1562–1568. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M800019-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Arvanitis M, Li D-D, Lee K, Mylonakis E. Apoptosis in C. elegans: lessons for cancer and immunity. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2013;3:67. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2013.00067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lettre G, Hengartner MO. Developmental apoptosis in C. elegans: a complex CEDnario. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7(2):97–108. doi: 10.1038/nrm1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sulston JE, Horvitz HR. Post-embryonic cell lineages of the nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1977;56(1):110–156. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(77)90158-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sulston JE, Schierenberg E, White JG, Thomson JN. The embryonic cell lineage of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1983;100(1):64–119. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(83)90201-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kimble J, Hirsh D. The postembryonic cell lineages of the hermaphrodite and male gonads in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1979;70(2):396–417. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(79)90035-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hedgecock EM, Sulston JE, Thomson JN. Mutations affecting programmed cell deaths in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 1983;220(4603):1277–1279. doi: 10.1126/science.6857247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Robertson AMG, Thomson JN. Morphology of programmed cell death in the ventral nerve cord of Caenorhabditis elegans larvae. Development. 1982;67(1):89–100. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ellis RE, Jacobson DM, Horvitz HR. Genes required for the engulfment of cell corpses during programmed cell death in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1991;129(1):79–94. doi: 10.1093/genetics/129.1.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hoeppner DJ, Hengartner MO, Schnabel R. Engulfment genes cooperate with ced-3 to promote cell death in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2001;412(6843):202–206. doi: 10.1038/35084103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Reddien PW, Cameron S, Horvitz HR. Phagocytosis promotes programmed cell death in C. elegans. Nature. 2001;412(6843):198–202. doi: 10.1038/35084096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Dickman M, Williams B, Li Y, de Figueiredo P, Wolpert T. Reassessing apoptosis in plants. Nat Plants. 2017;3(10):773–779. doi: 10.1038/s41477-017-0020-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Carmona-Gutierrez D, Fröhlich K-U, Kroemer G, Madeo F. Metacaspases are caspases. Doubt no more. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17(3):377–378. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Enoksson M, Salvesen GS. Metacaspases are not caspases—always doubt. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17(8):1221. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Chen S, Dickman MB. Bcl-2 family members localize to tobacco chloroplasts and inhibit programmed cell death induced by chloroplast-targeted herbicides. J Exp Bot. 2004;55(408):2617–2623. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erh275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Lacomme C, Santa Cruz S. Bax-induced cell death in tobacco is similar to the hypersensitive response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(14):7956–7961. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.7956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Reape TJ, McCabe PF. Apoptotic-like regulation of programmed cell death in plants. Apoptosis. 2010;15(3):249–256. doi: 10.1007/s10495-009-0447-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kader J-C, Delseny M. The botanical dance of death: programmed cell death in plants. In: Kacprzyk J, Daly CT, McCabe PF, editors. Advances in botanical research. Waltham, San Diego, Amsterdam: London; 2011. pp. 169–261. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Li W, Kabbage M, Dickman MB. Transgenic expression of an insect inhibitor of apoptosis gene, SfIAP, confers abiotic and biotic stress tolerance and delays tomato fruit ripening. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 2010;74(5–6):363–375. doi: 10.1016/j.pmpp.2010.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 111.McCabe PF, Levine A, Meijer P-J, Tapon NA, Pennell RI. A programmed cell death pathway activated in carrot cells cultured at low cell density. Plant J. 1997;12(2):267–280. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1997.12020267.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Li W, Dickman MB. Abiotic stress induces apoptotic-like features in tobacco that is inhibited by expression of human Bcl-2. Biotechnol Lett. 2004;26(2):87–95. doi: 10.1023/B:BILE.0000012896.76432.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Balk J, Chew SK, Leaver CJ, McCabe PF. The intermembrane space of plant mitochondria contains a DNase activity that may be involved in programmed cell death. Plant J. 2003;34(5):573–583. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Balk J, Leaver CJ. The PET1-CMS mitochondrial mutation in sunflower is associated with premature programmed cell death and cytochrome c release. Plant Cell. 2001;13(8):1803–1818. doi: 10.1105/TPC.010116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Reape TJ, McCabe PF. Apoptotic-like programmed cell death in plants. New Phytol. 2008;180(1):13–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.O’Brien IE, Reutelingsperger CP, Holdaway KM. Annexin-V and TUNEL use in monitoring the progression of apoptosis in plants. Cytometry. 1997;29(1):28–33. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0320(19970901)29:1<28::AID-CYTO2>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Min K, Son H, Lee J, Choi GJ, Kim J-C, Lee Y-W. Peroxisome function is required for virulence and survival of Fusarium graminearum. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2012;25(12):1617–1627. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-06-12-0149-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Vanyushin B, Bakeeva L, Zamyatnina V, Aleksandrushkina N. Apoptosis in plants: specific features of plant apoptotic cells and effect of various factors and agents. Int Rev Cytol. 2004;233:135–179. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(04)33004-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Polverari A, Buonaurio R, Guiderdone S, Pezzotti M, Marte M. Ultrastructural observations and DNA degradation analysis of pepper leaves undergoing a hypersensitive reaction to Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria. Eur J Plant Pathol. 2000;106(5):423–431. doi: 10.1023/A:1008773321809. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Cai Q, Qiao L, Wang M, He B, Lin F-M, Palmquist J, et al. Plants send small RNAs in extracellular vesicles to fungal pathogen to silence virulence genes. Science. 2018;360(6393):1126–1129. doi: 10.1126/science.aar4142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Gonçalves AP, Heller J, Daskalov A, Videira A, Glass NL. Regulated forms of cell death in fungi. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1837. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Ramsdale M. Programmed cell death in pathogenic fungi. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. 2008;1783(7):1369–1380. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Madeo F, Herker E, Maldener C, Wissing S, Lächelt S, Herlan M, et al. A caspase-related protease regulates apoptosis in yeast. Mol Cell. 2002;9(4):911–917. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00501-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Carmona-Gutierrez D, Eisenberg T, Büttner S, Meisinger C, Kroemer G, Madeo F. Apoptosis in yeast: triggers, pathways, subroutines. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17(5):763–773. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Madeo F, Engelhardt S, Herker E, Lehmann N, Maldener C, Proksch A, et al. Apoptosis in yeast: a new model system with applications in cell biology and medicine. Curr Genet. 2002;41(4):208–216. doi: 10.1007/s00294-002-0310-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.McGary KL, Park TJ, Woods JO, Cha HJ, Wallingford JB, Marcotte EM. Systematic discovery of nonobvious human disease models through orthologous phenotypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(14):6544–6549. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910200107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Simon J, Bedalov A. Yeast as a model system for anticancer drug discovery. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(June):1–8. doi: 10.1038/nrc1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Yamaki M, Umehara T, Chimura T, Horikoshi M. Cell death with predominant apoptotic features in Saccharomyces cerevisiae mediated by deletion of the histone chaperone ASF1/CIA1. Genes Cells. 2001;6(12):1043–1054. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2001.00487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Madeo F, Fröhlich E, Fröhlich KU. A yeast mutant showing diagnostic markers of early and late apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 1997;139(3):729–734. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.3.729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Váchová L, Palková Z. Physiological regulation of yeast cell death in multicellular colonies is triggered by ammonia. J Cell Biol. 2005;169(5):711–717. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200410064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Fabrizio P, Battistella L, Vardavas R, Gattazzo C, Liou L-L, Diaspro A, et al. Superoxide is a mediator of an altruistic aging program in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol. 2004;166(7):1055–1067. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200404002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Kaczanowski S, Sajid M, Reece SE. Evolution of apoptosis-like programmed cell death in unicellular protozoan parasites. Parasites Vectors. 2011;4(1):44. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-4-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Lüder CG, Campos-Salinas J, Gonzalez-Rey E, van Zandbergen G. Impact of protozoan cell death on parasite-host interactions and pathogenesis. Parasites Vectors. 2010;3(1):116. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-3-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Proto WR, Coombs GH, Mottram JC. Cell death in parasitic protozoa: regulated or incidental? Nat Rev Microbiol. 2013;11(1):58–66. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Ameisen JC, Idziorek T, Billaut-Mulot O, Loyens M, Tissier JP, Potentier A, et al. Apoptosis in a unicellular eukaryote (Trypanosoma cruzi): implications for the evolutionary origin and role of programmed cell death in the control of cell proliferation, differentiation and survival. Cell Death Differ. 1995;2(4):285–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Mamani-Matsuda M, Rambert J, Malvy D, Lejoly-Boisseau H, Daulouède S, Thiolat D, et al. Quercetin induces apoptosis of Trypanosoma brucei gambiense and decreases the proinflammatory response of human macrophages. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48(3):924–929. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.3.924-929.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Duszenko M, Figarella K, Macleod ET, Welburn SC. Death of a trypanosome: a selfish altruism. Trends Parasitol. 2006;22(11):536–542. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2006.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Piacenza L, Peluffo G, Radi R. l-Arginine-dependent suppression of apoptosis in Trypanosoma cruzi: contribution of the nitric oxide and polyamine pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2001;98(13):7301–7306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121520398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Irigoín F, Inada NM, Fernandes MP, Piacenza L, Gadelha FR, Vercesi AE, et al. Mitochondrial calcium overload triggers complement-dependent superoxide-mediated programmed cell death in Trypanosoma cruzi. Biochem J. 2009;418(3):595–604. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Welburn SC, Dale C, Ellis D, Beecroft R, Pearson TW. Apoptosis in procyclic Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense in vitro. Cell Death Differ. 1996;3(2):229–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Das M, Mukherjee SB, Shaha C. Hydrogen peroxide induces apoptosis-like death in Leishmania donovani promastigotes. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:2461–2469. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.13.2461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Paris C, Loiseau PM, Bories C, Bréard J. Miltefosine induces apoptosis-like death in Leishmania donovani promastigotes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48(3):852–859. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.3.852-859.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Shadab M, Jha B, Asad M, Deepthi M, Kamran M, Ali N. Apoptosis-like cell death in Leishmania donovani treated with KalsomeTM10, a new liposomal amphotericin B. PLoS One. 2017;12(2):e0171306. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Gannavaram S, Debrabant A. Programmed cell death in Leishmania: biochemical evidence and role in parasite infectivity. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2012;2:95. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Arambage SC, Grant KM, Pardo I, Ranford-Cartwright L, Hurd H. Malaria ookinetes exhibit multiple markers for apoptosis-like programmed cell death in vitro. Parasites Vectors. 2009;2(1):32. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-2-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Meslin B, Barnadas C, Boni V, Latour C, Monbrison FD, Kaiser K, et al. Features of apoptosis in Plasmodium falciparum erythrocytic stage through a putative role of PfMCA1 metacaspase-like protein. J Infect Dis. 2007;195(12):1852–1859. doi: 10.1086/518253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Al-Olayan EM, Williams GT, Hurd H. Apoptosis in the malaria protozoan, Plasmodium berghei: a possible mechanism for limiting intensity of infection in the mosquito. Int J Parasitol. 2002;32(9):1133–1143. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7519(02)00087-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Ni Nyoman AD, Lüder CGK. Apoptosis-like cell death pathways in the unicellular parasite Toxoplasma gondii following treatment with apoptosis inducers and chemotherapeutic agents: a proof-of-concept study. Apoptosis. 2013;18(6):664–680. doi: 10.1007/s10495-013-0832-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Peng B-W, Lin J, Lin J-Y, Jiang M-S, Zhang T. Exogenous nitric oxide induces apoptosis in Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites via a calcium signal transduction pathway. Parasitology. 2003;126(6):541–550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Jensen JB, Boland MT, Akood M. Induction of crisis forms in cultured Plasmodium falciparum with human immune serum from Sudan. Science. 1982;216(4551):1230. doi: 10.1126/science.7043736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Deponte M, Becker K. Plasmodium falciparum—do killers commit suicide? Trends Parasitol. 2004;20(4):165–169. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2004.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]