Abstract

Enhancement of insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF-IR) degradation by heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) inhibitor is a potential antitumor therapeutic strategy. However, very little is known about how IGF-IR protein levels are degraded by HSP90 inhibitors in pancreatic cancer (PC). We found that the HSP90α inhibitor NVP-AUY922 (922) effectively downregulated and destabilized the IGF-1Rβ protein, substantially reduced the levels of downstream signaling molecules (p-AKT, AKT and p-ERK1/2), and resulted in growth inhibition and apoptosis in IGF-1Rβ-overexpressing PC cells. Preincubation with a proteasome or lysosome inhibitor (MG132, 3 MA or CQ) mainly led to IGF-1Rβ degradation via the lysosome degradation pathway, rather than the proteasome-dependent pathway, after PC cells were treated with 922 for 24 h. These results might be associated with the inhibition of pancreatic cellular chymotrypsin–peptidase activity by 922 for 24 h. Interestingly, 922 induced autophagic flux by increasing LC3II expression and puncta formation. However, knockdown of the crucial autophagy component AGT5 and the chemical inhibitor 3 MA-blocked 922-induced autophagy did not abrogate 922-triggered IGF-1Rβ degradation. Furthermore, 922 could enhance chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA) activity and promote the association between HSP/HSC70 and IGF-1Rβ or LAMP2A in coimmunoprecipitation and immunofluorescence analyses. Silencing of LAMP2A to inhibit CMA activity reversed 922-induced IGF-1Rβ degradation, suggesting that IGF-1Rβ degradation by 922 was partially dependent on the CMA pathway rather than macroautophagy. This finding is mirrored by the identification of the KFERQ-like motif in IGF-1Rβ. These observations support the potential application of 922 for IGF-1Rβ-overexpressing PC therapy and first identify the role of the CMA pathway in IGF-1Rβ degradation by an HSP90 inhibitor.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00018-019-03080-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor β, Pancreatic cancer, Heat shock protein 90, Autophagy

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer (PC) is the third leading cause of cancer-related death in the USA. Despite decades of research on PC, the overall 5-year survival rate of PC has improved marginally from 3.0% in the 1970s to 7.6% currently [1]. Therefore, new and effective therapies against PC are urgently needed. Insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF-1R) is an important growth factor receptor in cancer that is overactivated and/or overexpressed in multiple cancers, including PC [2]. IGF-1R is a member of the insulin receptor (IR) family and shares high sequence homology with the IR [3]. As a transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptor, IGF-1R is activated by the binding of its ligands IGF-I (the highest affinity), IGF-II (reduced affinity) and insulin (low affinity) with differing affinities [4], resulting in activation of 70–100% of the intracellular signaling cascades involved in pancreatic pathogenesis [5, 6]. These signaling pathways, including phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and janus kinase (JAK)/signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT), can promote proliferation, survival and metastasis while inhibiting apoptosis of PC cells [7, 8]. Thus, targeting IGF-IR has become an attractive therapeutic strategy for PC [4].

In addition to tyrosine kinase inhibitors and receptor–ligand interaction blockers, a potential strategy for inhibiting IGF-IR function is promotion of the cellular degradation of constitutively overexpressed IGF-IR [9]. Picard et al. discovered that IGF-1R, a client protein of heat shock protein 90 (HSP90), is stabilized and protected from protein degradation by HSP90 (http://www.picard.ch/downloads/Hsp90interactors). HSP90 is an essential molecular chaperone involved in the folding, stabilization and conformational maturation of its client proteins. The majority of these client proteins are implicated in the growth, differentiation, anti-apoptosis effects and metastasis of multiple cancers. Inhibition of overactive HSP90 function in cancer could promote the degradation of oncogenic clients and eventually result in blockage of tumorigenesis and aggravation [10]. We and others previously showed that HSP90 inhibitors, such as 17-AAG and geldanamycin (GA), downregulated IGF-1Rβ and inhibited its downstream signaling pathways mediated by PI3K/AKT and MAPK, resulting in reduced pancreatic tumor growth and vascularization in an orthotopic model [11, 12]. Zitzmann et al. also found that other HSP90 inhibitors, such as NVP-AUY922 (922) and HSP990, could substantially decrease the IGF-IR level in the human pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor cell line BON-1 [13]. However, the mechanism underlying downregulation of IGF-IR mediated by HSP90 inhibition has not yet been fully elucidated.

While it is generally believed that HSP90 inhibitors induce the degradation of client proteins through the ubiquitin–proteasome system (UPS) [14, 15], we previously showed that the HSP90 inhibitor Y306zh induced IGF-1Rβ degradation in a mechanism independent of the ubiquitin–proteasomal pathway [12]. Consistent with our results, HSP90 inhibitors, such as 17-DMAG, SNX-2112 and BIIB021, have been shown to induce autophagy through a pathway involving inhibition of AKT/mTOR signaling [16–18], and accordingly, inhibition of HSP90 chaperone function could induce the degradation of several clients (such as IKK, EGFR, KIT and α-synuclein) by the autophagy–lysosomal pathway [19–22]. At least three types of autophagy have been identified in mammals [23]: macroautophagy, microautophagy and chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA). Characterized by dynamic formation of autophagosome and direct engulfment to cargo by the lysosome surface [24], macroautophagy and microautophagy mediate basic and nonselective degradation of proteins, lipids and organelles, respectively. In contrast, CMA mediates selective degradation of substrates containing a KFERQ-like motif by binding to heat shock cognate 70 kDa protein (HSC70/HSPA8) and lysosome-associated membrane protein type 2A (LAMP2A), followed by translocation of target proteins to the lysosome for degradation [25, 26]. To date, whether and how HSP90 inhibitors mediate IGF-1Rβ degradation via the autophagy–lysosomal pathway remains unclear.

Here, we showed that the HSP90 inhibitor 922 exerts a potential antitumor effect on IGF-1Rβ-overexpressing PC cells. We found that 922 could promote the degradation of IGF-1Rβ protein and inhibit the downstream signaling components (p)/AKT and p-ERK1/2 in Mia-paca2 and Capan-2 cells. In addition to the proteasome-dependent pathway, the lysosome pathway plays an important role in 922-induced IGF-1Rβ degradation in PC cells. Although 922 enhanced the autophagic flux in PC cells, the degradation of IGF-1Rβ protein induced by 922 was partially dependent on CMA-mediated lysosomal degradation by promoting the interaction between HSP/HSC70 and IGF-1Rβ or LAMP2A. We provided the first evidence for the involvement of the CMA pathway in the IGF-1Rβ degradation induced by an HSP90 inhibitor and supported the potential application of 922 for IGF-1Rβ-overexpressing PC therapy.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and culture conditions

The human PC cell lines Mia-paca2 and Capan-2 were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). These cell lines were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere and 5% CO2 in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Gibco®, Life Technologies TM, Carlsbad, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), streptomycin (100 μg/ml) and penicillin (100 U/ml).

Antibodies and chemical reagents

Antibodies against IGF-IRβ, p-AKTSer473, AKT, p-ERK1/2Thr202/Tyr204, cleaved PARP, CDK4, ATG5, LC3A/B, HSP70/HSC70, p62 and the corresponding HRP-conjunction secondary antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technologies. LAMP2A antibody was purchased from Abcam. The appropriate fluorescein-labeled secondary antibodies to anti-rat Alexa Fluor 647 dye and anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 dye were purchased from Invitrogen (Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The HSP90 inhibitors 922 (5-(2,4-dihydroxy-5-isopropylphenyl)-N-ethyl-4-[4-(4-morpholinylmethyl)phenyl]-1,2-oxazole-3-carboxamide) and GA were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), and Y306zh was synthesized and identified as previously described [12]. MG132 (#M7449), chloroquine (CQ, #C6628), 3 methyladenine (3 MA, #M9281), cycloheximide (CHX, #C1988) and 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). LysoTracker® Red DND-99 (#L7528) was obtained from Invitrogen (Molecular Probes, Paisley, UK). N-succinyl-Leu–Leu-Val-Tyr-7-amino-4-methylcoumarin (Suc-LLVY-AMC) was purchased from Enzo Life Sciences (Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA).

Cell viability assays

The MTT assay was used to measure cell viability. Briefly, Mia-paca2 or Capan-2 cells were seeded in 96-well plates overnight at a density of 2 × 103/well and treated with 922 or GA at concentrations ranging from 1.1 nM to 33.3 μM for an additional 72 h. MTT (0.5 mg/mL) was incubated for 4 h. Then, the formazan crystals were solubilized in 150 μL DMSO and measured by spectrophotometry at a 570 nm wavelength. IC50 values were calculated using GraphPad Prism 5 software.

Flow cytometry assay

Annexin V–FITC/propidium iodide (PI) dual staining was used to detect the apoptotic effect on PC cells according to the manufacturer’s recommended procedures (Tianjin Sungene Biotech Co., Ltd.), and the samples were analyzed by a BD FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) using the Modfit LT program.

Western blot and coimmunoprecipitation (coIP) analysis

Treated and untreated PC cell lysates (30 μg) were subjected to SDS-PAGE as described previously [12]. Signals were visualized by Image Quant LAS 4000 (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA). The relative protein levels were calculated based on β-actin as the loading control and were densitometrically analyzed by ImageJ software (NIH, MD).

For detection of proteasomal or autophagy–lysosomal degradation of client proteins, Mia-paca2 and Capan-2 cells were preincubated with 1 or 3 μM MG132, 50 μM CQ, 20 mM NH4Cl or 5 mM 3 MA for 2 h and then treated with 1 μM of 922 for an additional 6 h or 24 h. The samples of Triton-soluble and Triton-insoluble proteins were analyzed by 10% SDS-PAGE as previously described [27].

For the coIP assays, Mia-paca2 cells were treated with 1 μM 922 for 24 h. 500 μg proteins of whole cell extracts were incubated with 5 μL anti-IGF-1Rβ antibody or 2 μg anti-LAMP2A antibody overnight at 4 °C rotation. Then, 30 μL of Protein A/G PLUS-Agarose (sc-2003; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., USA) was added to each sample and shaken for 4 h at 4 °C. The protein–agarose pellet was washed twice with RIPA:PBS (1:1 dilution) and once with ice-cold PBS, then eluted with loading buffer and subsequently used for western blot analysis.

Quantitative RT-PCR (qPCR)

PCR amplifications for the quantification of IGF-1Rβ, HSC70, LAMP2A and LAMP1 genes were performed using a SYBR Green PCR Master Mix kit (Cat. QPK-201, Toyobo, Japan) and an ABI PRISM 7900 Sequence Detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The primers used for qPCR were as follows: IGF-1Rβ, F, 5′-AGAATAATCCAGTCCTAGCACCT-3′, R, 5′-GAAATCTTCGGCTACCATGCAA-3′; HSC70, F, 5′-CCTCATCAAGCGTAATACCAC-3′, R, 5′-TCATAAACCTGAATAAGCACACC-3′; LAMP2A, F, 5′-ATTTGGTTAATGGCTCCGTTT-3′, R, 5′-CACATTGAAAGGCTGAACCC-3′; LAMP1, F, 5′-ACCTTTGACCTGCCATCAGA-3′, R, 5′-TAACGTGTTGCATTTCTCGTG-3′; GAPDH, F, 5′-CCACTCCTCCACCTTTGAC-3′, R, 5′-ACCCTGTTGCTGTAGCCA-3′. GAPDH was used as an internal control. The fold changes in IGF-1Rβ, HSC70, LAMP2A and LAMP1 gene expression were calculated according to the method.

Immunofluorescence assay

Mia-paca2 and Capan-2 cells were seeded on 96-well plates at a density of 8 × 103/well (Corning #3603) or 8-well slides (1 × 104/well) (#PEZG0896, Millipore, USA) and treated with 0.2 or 1 μM 922 or 50 μM CQ for 6 h or 24 h, followed by labeling with or without 50 nM LysoTracker Red DND-99 for 30 min. PC cells were washed three times and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min at room temperature and blocked with 3% BSA containing 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS buffer. Subsequently, these cells were stained with single primary antibodies against IGF-1Rβ or LC3A/B or were double labeled with anti-LAMP2A and anti-HSP70/HSC70 antibodies at 4 °C overnight. After washing three times with PBS, cells were incubated with anti-rat Alexa Fluor 647 dye (Red) and anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 dye (Green) for 1 h at room temperature in the dark. Slides were mounted using Anti-Fade DAPI Solution, and images were acquired using a cell analyzer 1000 (GE Healthcare) or confocal microscopy (Olympus, FV1000, Confocal Laser Scanning Biological Microscope).

RNA interference assay

Small interfering RNA (siRNA) specific to human ATG5 and negative control siRNA were purchased from the RiboBio Company (Cat. 1299003, Guangzhou, China). pSuper-LAMP2A RNAi and pSuper-empty plasmid were generous gifts from A.M. Cuervo (Albert Einstein College of Medicine, NY, USA). Mia-paca2 cells were transfected with ATG5, LAMP2A or negative control si/shRNA using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. In brief, Mia-paca2 cells were grown to approximately 70% confluence in six-well plates and then transfected with 50 nM siATG5 or 2 μg of pSuper-shLAMP2A plasmid and the control si/shRNA mixed with 5 μL of Lipofectamine 2000 reagent. After transfection for 6 h, the cells were cultured with serum-containing complete medium for 18 h and then treated with 1 μM 922 for an additional 24 h. ATG5, LAMP2A or IGF-1Rβ expression was confirmed by qPCR or western blot with specific antibody.

Proteasome activity assays

Proteasome chymotrypsin peptidase activity was determined using fluorescence assays as described previously [28, 29]. PC cells were harvested and resuspended in HEPES buffer (5 mM HEPES, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.5) and then disrupted by sonication. After centrifugation at 12,000 rpm at 4 °C for 15 min, the supernatant was used to provide the 20S proteasome for analysis of the direct influence of compounds on proteasomal activity. For each sample, equal cellular extract (10 μg protein) was incubated with the proteasome substrate Suc-LLVY-AMC (80 μM) in the presence of the indicated concentrations of 922, GA, Y306zh, MG132 or CQ in assay buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 0.5% NP40, 0.2 mM ATP, 2 mM DTT, pH 8.0) in a black 96-well plate (200 μL/well) at 37 °C. Fluorescence was determined after 60 min at 380 nm excitation and 440 nm emission in an Enspire Multilabel Plate reader (PerkinElmer, CA, USA). The inhibitory effect of compound on proteasome activity was represented by the following formula: Inhibition rate (%) = 100 × (RFUctrl − RFUcompound)/RFUctrl.

To measure proteasomal activity in live PC cells, Mia-paca2 cells were incubated with the indicated doses of 922, GA, Y306zh or MG132 for 6 or 24 h and then harvested and sonicated in HEPES buffer. Aliquots of 100 μL each (10 μg protein) were incubated with the substrate Suc-LLVY-AMC (80 μM) in a black 96-well plate (200 μL/well) at 37 °C for 120 min, and substrate hydrolysis was determined every 10 min by measuring fluorescence at 380 nm excitation and 440 nm emission in an Enspire Multilabel Plate reader (PerkinElmer, CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

The results are expressed as the mean ± SD from three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

NVP-AUY922 downregulates the IGF-1Rβ protein level in PC cells

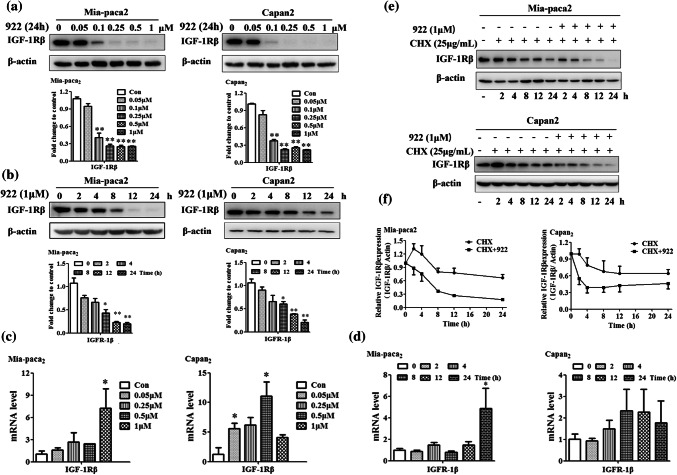

Mia-paca2 and Capan-2 cells over-expressing both HSP90a and IGF-1Rβ were used in our study [12] (Supplemental Fig. 1a). We exposed these cells to several well-known HSP90 inhibitors, including GA, 922 and Y306zh, for 24 h and found that the IGF-1Rβ protein levels in both Mia-paca2 and Capan-2 cells were significantly downregulated in a dose-dependent manner (Supplemental Fig. 1b). Among these HSP90 inhibitors, 922 exhibited the strongest inhibition of IGF-1Rβ expression. We also determined the IGF-1Rβ level in PC cells in the presence of 922 at varying doses and for various periods. Western blot analysis showed that the IGF-1Rβ expression level was dose-dependently reduced after treatment with 0.05–1 μM 922 for 24 h and time-dependently decreased by treatment with 1 μM 922 for 2 h to 24 h in Mia-paca2 and Capan-2 cells (Fig. 1a, b). In addition, immunofluorescence analysis of IGF-1Rβ staining showed that 922 could remarkably reduce IGF-1Rβ expression in the surface and cytosol of Mia-paca2 cells (Supplemental Fig. 1c, d).

Fig. 1.

NVP-AUY922 promotes IGF-1Rβ degradation in PC cells. Mia-paca2 and Capan-2 cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of 922 for 24 h or treated with 1 μM 922 for different times. a, b IGF-1Rβ expression was detected by western blot analysis. β-actin served as a loading control. Relative protein levels were quantified by densitometry and are shown in the histogram. c, d The IGF-1Rβ mRNA level in 922-treated Mia-paca2 or Capan-2 cells was measured by qPCR. GAPDH served as the internal standard. e Mia-paca2 and Capan-2 cells were treated with 25 μg/mL of CHX alone or in combination with 1 μM of 922 for the indicated times. Cells were lysed and analyzed by immunoblotting against IGF-1Rβ. The IGF-1Rβ expression level was normalized to β-actin. f Quantification of the degradation rate of the IGF-1Rβ protein. The half-life of the IGF-1Rβ protein was calculated as the relative IGF-1Rβ expression level. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3). *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01 versus con

To exclude the possibility that the downregulation of IGF-1Rβ protein level by 922 is due to decreased transcription of the IGF-1Rβ gene, we measured the IGF-1Rβ mRNA level after treatment with 922 for 24 h in both PC cells. As shown in Fig. 1c, 922 at concentrations sufficient to decrease the IGF-1Rβ protein level did not decrease but rather increased the IGF-1Rβ mRNA levels in Mia-paca2 and Capan-2 cells. Furthermore, exposure to 1 μM 922 for 2 to 24 h did not decrease IGF-1Rβ mRNA levels in either PC cell line (Fig. 1d). These results suggest that the 922-induced decreases in IGF-1Rβ protein expression were independent of the inhibition of transcription. We thus determined whether this change was caused by the promotion of protein degradation by measuring the half-life of the IGF-1Rβ protein in the presence/absence of the HSP90 inhibitor in cycloheximide (CHX) chase assays. As shown in Fig. 1e, f, the half-life of endogenous IGF-1Rβ protein in the presence of 922 combined with CHX was dramatically decreased compared with that of CHX alone in both PC cells. Thus, we demonstrated that the HSP90 inhibitor 922 could promote degradation of the IGF-1Rβ protein in PC cells.

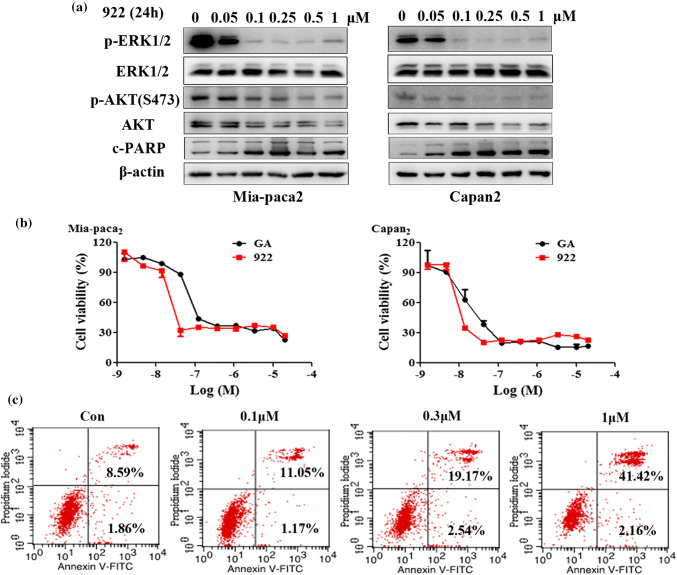

NVP-AUY922 inhibits downstream signaling of IGF-1Rβ and exhibits antitumor activity against PC cells

The phosphoinositide 3-OH kinase (PI3K)/AKT and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways were crucial downstream targets of IGF-1R signaling that play important roles in the growth and survival of PC cells [30]. Consistent with the inhibition of IGF-1Rβ expression, treatment with 922 (0.05–1 μM) for 24 h dose-dependently decreased the levels of p-ERK1/2, p-AKT and total AKT in both Mia-paca2 and Capan-2 cells (Fig. 2a). Meanwhile, we detected the cytotoxic effect of 922 in PC cells by cell viability assays. As described in Fig. 2b, similar to GA, 922 treatments resulted in a dose-dependent inhibition of PC cell viability. The IC50 values of 922 and GA were 12.48 and 63.30 nM in Mia-paca2 cells and 13.74 and 45.68 nM in Capan-2 cells, respectively. Furthermore, Annexin V–FITC/PI dual staining showed that 922 mainly induced late apoptosis and necrosis in PC cells. The cell populations, as identified by Annexin V-positive and PI-positive staining, increased from 8.6% in the untreated control to 41.4% in the treated group (1 μM) of Mia-paca2 cells (Fig. 2c). These results were further supported by a dose-dependent increase in the level of cleaved PARP (an apoptotic marker) in Mia-paca2 and Capan-2 cells (Fig. 2a). Thus, 922 decreased IGF-1Rβ-mediated AKT and ERK1/2 signaling, concurrently inhibiting PC cell viability and inducing late apoptosis/necrosis.

Fig. 2.

NVP-AUY922 inhibits downstream signaling of IGF-1Rβ and exerts antitumor effects on PC cells. a Mia-paca2 and Capan-2 cells were incubated with the indicated doses of 922 for 24 h, and the levels of p-ERK1/2, ERK1/2, p-AKT, AKT, and c-PARP were measured by western blot analyses. b Cell viability was measured by MTT assays in Mia-paca2 and Capan-2 cells after treatment with different concentrations of 922 or GA for 72 h. c Mia-paca2 cells were treated with 0.1, 0.3 or 1 μM 922 for 24 h and then analyzed by Annexin V–PI staining. All data are expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 3)

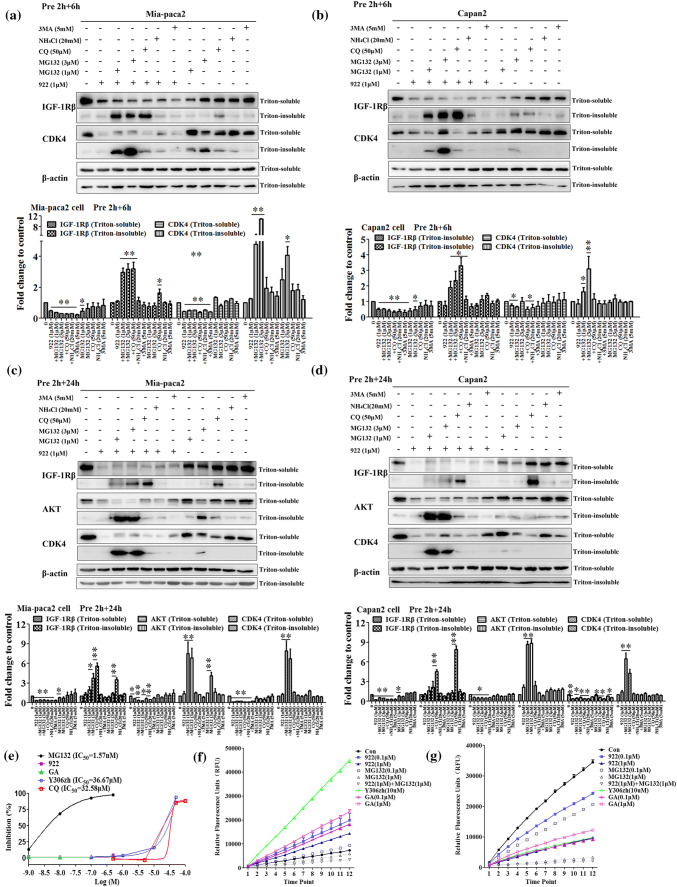

NVP-AUY922 induces IGF-1Rβ degradation via the lysosomal pathway

To characterize the pathway involved in the degradation of IGF-1Rβ induced by 922, Mia-paca2 and Capan-2 cells were pretreated with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (1 or 3 μM), lysosome inhibitors CQ (50 μM) and ammonium chloride (NH4Cl, 20 mM), or the autophagy inhibitor 3 methyladenine (3 MA, 5 mM) for 2 h, followed by coincubation with 1 μM of 922 for an additional 6 or 24 h. Western blot analysis showed that the decrease of the IGF-1Rβ protein level by exposure to 922 for 6 h could be significantly rescued by both MG132 and CQ in Mia-paca2 and Capan-2 cells, as shown by significant accumulation of IGF-1Rβ protein in the Triton-insoluble fraction after treatment 922 in combination with MG132 or CQ (Fig. 3a, b). These results suggested that not only the proteasome, but also the lysosome-mediated degradation pathway participated in IGF-1Rβ degradation induced by 922 for 6 h in PC cells. Interestingly, when the cells were treated with 922 for 24 h, the downregulation of the IGF-1Rβ level could be reversed by CQ pretreatment but not MG132, particularly in Capan-2 cells (Fig. 3c, d). These data indicated that the lysosome pathway was the preferred degradation pathway for 922-mediated downregulation of IGF-1Rβ when the cells were treated for 24 h. Lysosomal degradation induced by 922 appeared to be specific to IGF-1Rβ in our study, as only MG132 but not CQ could reverse the decrease of AKT and CDK4, two other HSP90 clients in the cytoplasm, induced by the HSP90 inhibitor, as expected [31].

Fig. 3.

NVP-AUY922 induces IGF-1Rβ degradation mainly via the lysosomal pathway. a–d Mia-paca2 and Capan-2 cells were pretreated with MG132 (1, 3 μM), CQ (50 μM), NH4Cl (20 mM) or 3 MA (5 mM) for 2 h and then treated with 1 μM of 922 for an additional 6 h or 24 h. The IGF-1Rβ, CDK4 or AKT protein levels from Triton-soluble and Triton-insoluble fractions were measured by western blotting. β-actin was used as a loading control. Relative protein levels were quantified by densitometry and are shown in the histogram. e The chymotrypsin-like proteasome activity was determined as a magnitude of fluorogenic proteasome substrate (Suc-LLVY-AMC) degradation. Human 20S proteasome from Mia-paca2 cell lysates was incubated with 922, GA, Y306zh, CQ, or MG132, and the chymotrypsin-like proteasome activities were monitored after 60 min. MG132 served as a positive control. Relative proteasome activity is represented by the percentage of fluorescence compared with the control. f, g Mia-paca2 cells were treated with the indicated doses of 922, GA, Y306zh, CQ, or MG132 for 6 h or 24 h, and the chymotrypsin-like proteasome activities were monitored every 10 min. All data are expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 3). *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01 versus con

Furthermore, we detected the effect of 922 on proteasomal and lysosomal activity at the extra/intercellular level. As indicated in Fig. 3e, 500 nM of 922 or GA did not directly impair chymotrypsin-like proteasomal activity, while MG132 exhibited potential inhibitory activity with an IC50 value of 1.57 nM. In live PC cells, chymotrypsin-like proteasomal activity was enhanced after exposure to 922 or GA (0.1 and 1 μM) for 6 h, but decreased by ~ 70% after treatment with 1 μM 922 or GA for 24 h (Fig. 3f, g). Interestingly, quantitative evaluation of LysoTracker-labeled lysosomes indicated that CQ could significantly increase the numbers of acidic lysosomes, while 922 did not affect the acidic lysosomes (Supplemental Fig. 2), suggesting that 922 did not cause lysosomal degradation of IGF-1Rβ by regulating lysosome activity.

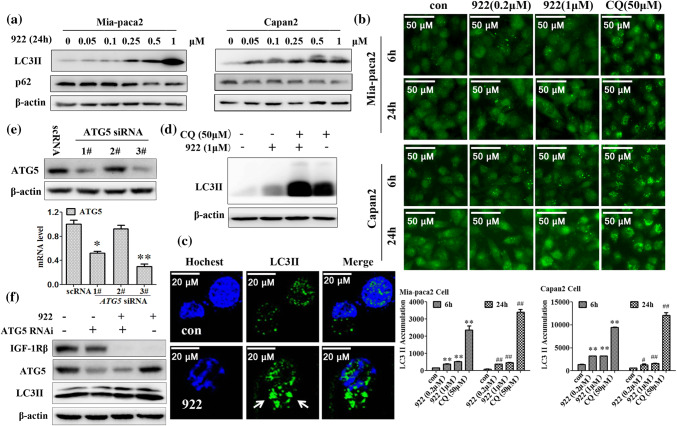

NVP-AUY922-induced IGF-1Rβ degradation is independent of macroautophagy

To further confirm whether autophagy is involved in 922-induced IGF-1Rβ degradation, we examined LC3 II accumulation (a component of autophagosomes) as well as expression of the autophagy-specific substrate p62 after 922 treatments in PC cells. As shown in Fig. 4a–c, 922 markedly increased the LC3 II levels and induced the formation of LC3 II-positive puncta in a dose-dependent manner in PC cells. Moreover, 922 did not induce p62 expression, but rather reduced p62 levels. Because turnover of LC3 II itself is performed by autophagy, we compared LC3 II levels in the absence and presence of CQ. Figure 4d shows that the LC3 II protein level was significantly increased after inhibiting lysosomal degradation by CQ. Moreover, the LC3 II levels were further augmented by treatments of 922 in combination with CQ compared to CQ administration alone. These findings suggest that 922 induced the formation of autophagic flux in PC cells.

Fig. 4.

NVP-AUY922-induced IGF-1Rβ degradation is independent of macroautophagy. a Western blot analysis of the expression of the autophagy-related proteins LC3 II and p62 in Mia-paca2 and Capan-2 cells after treatment with the indicated doses of 922 for 24 h. β-actin served as a loading control. b Expression of LC3 II in Mia-paca2 and Capan-2 cells after treatment with 0.2 or 1 μM of 922 or 50 μM of CQ for 6 h or 24 h was assessed by immunofluorescence using a GE InCell Analyzer 1000. c Representative images of LC3 II puncta formation are presented after treatment with 1 μM of 922 for 24 h in Mia-paca2 cells (× 400). d Mia-paca2 cells were cultured in 1 μM of 922 for 24 h with or without CQ pretreatment (50 μM, 2 h). The LC3 II expression was detected using western blot analysis. e The mRNA level of ATG5 was silenced by siRNA in Mia-paca2 cells. f Knockdown of ATG5 by 50 nM targeted siRNA for 24 h in Mia-paca cells followed by treatment with 1 μM 922 for another 24 h. The expressions of ATG5 and IGF-1Rβ were detected by western blot analysis. The data are expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 3). **P ≤ 0.01 versus con of 6 h. #P ≤ 0.05, ##P ≤ 0.01 versus con of 24 h

Although 922 activated autophagic flux, 3 MA (a specific macroautophagy inhibitor) did not rescue the IGF-1Rβ degradation induced by 922 for 6 or 24 h in both Mia-paca2 and Capan-2 cells, indicating that 922-induced IGF-1Rβ degradation might be independent of macroautophagy (Fig. 3a, b). To further assess this idea, we attenuated the expression of ATG5, an essential molecule for autophagosome formation [32], using ATG5-specific siRNA. The 3# ATG5 siRNA effectively reduced the transcription and protein levels of ATG5 in Mia-capa2 cells (Fig. 4e). As expected, knockdown of ATG5 could inhibit macroautophagy, which was characterized by a decrease in LC3 II protein levels in Fig. 4f. However, 922-induced degradation of IGF-1Rβ protein was not reversed in ATG5-knockdown (ATG5−/−) Mia-paca2 cells (Fig. 4f).

NVP-AUY922 induces IGF-1Rβ degradation via a chaperone-mediated autophagy pathway

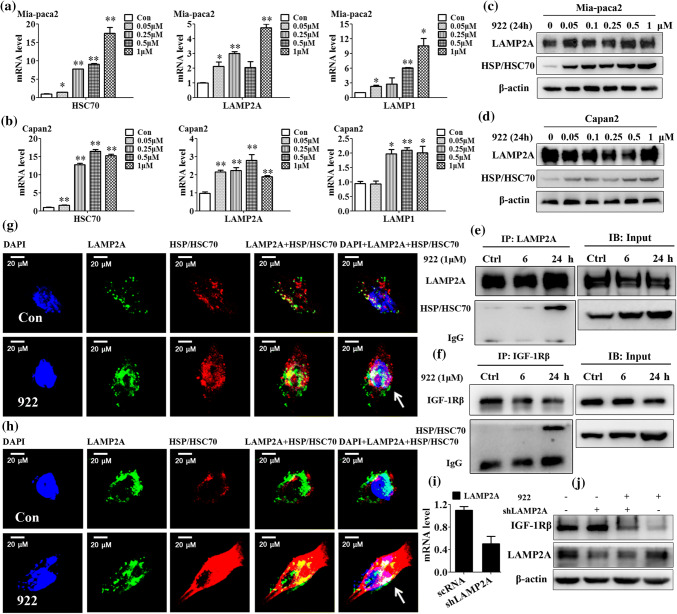

CMA is a selective mechanism for the degradation of substrates with the KFERQ-like motif in lysosomes by an HSC70–LAMP2A chaperone complex [25]. First, we found that 922 dose-dependently increased HSC70, LAMP2A and LAMP1 mRNA levels in both Mia-paca2 and Capan-2 cells by qPCR analysis (Fig. 5a, b). Western blot analysis revealed that 922 strongly increased HSP70/HSC70 protein levels in a concentration-dependent manner, without an obvious effect on LAMP2A expression, in Mia-paca2 and Capan-2 cells (Fig. 5c, d). Second, coIP assays were performed using LAMP2A antibody or IGF-1Rβ antibody in Mia-paca2 cells. As shown in Fig. 5e, f, treating cells with 1 μM 922 for 24 h not only increased the amount of HSP/HSC70 interacting with endogenous LAMP2A, but also promoted the association between IGF-1Rβ and HSP/HSC70. Consistently, in confocal microscope analysis, a significantly increased amount of HSP/HSC70 colocalized with LAMP2A was visualized as yellow dots upon treatment with 1 μM of 922 for 24 h in Mia-paca2 and Capan-2 cells. Meanwhile, we found that LAMP2A was redistributed to the nucleus in 922-treated Mia-paca2 and Capan-2 cells (Fig. 5g, h).

Fig. 5.

NVP-AUY922 induces IGF-1Rβ degradation partially via a chaperone-mediated autophagic pathway. a, b The mRNA levels of HSC70, LAMP2A and LAMP1 were detected in Mia-paca2 and Capan-2 cells after incubation with the indicated concentrations of 922 for 24 h by qPCR. GAPDH served as an internal standard. c, d The LAMP2A and HSC/HSP70 expression levels in Mia-paca2 and Capan-2 cells after treatment with the indicated doses of 922 for 24 h were analyzed by western blots. β-actin served as a loading control. e, f LAMP2A or IGF-1Rβ coIP assays. Lysates (500 μg) from Mia-paca2 cells treated with 922 (1 μM) for 6 or 24 h were immunoprecipitated with LAMP2A or IGF-1Rβ antibodies, and the precipitates were used for western blot assays to evaluate LAMP2A, HSC70/HSC70 or IGF-1Rβ protein levels. IgG served as an internal control. Input: total cell lysate. g, h After 24 h of 922 (1 μM) treatments, Mia-paca2 and Capan-2 cells were stained with anti-LAMP2A (green) and anti-HSC/HSP70 (red) antibodies and then visualized by confocal fluorescence microscopy. DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) was used to label the nucleus (blue). Representative images are presented (400 ×). i The LAMP2A mRNA level after LAMP2A knockdown by vector-mediated RNAi. j Silencing of LAMP2A for 24 h in Mia-paca2 cells and then treated with 1 μM of 922 for another 24 h. The IGF-1Rβ and LAMP2A expression levels were analyzed by western blot. The data are expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 3). *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01 versus con

LAMP2A recognition is a rate-limiting factor in CMA [33]. We further investigated whether silencing LAMP2A could block the IGF-1Rβ degradation induced by 922. As shown in Fig. 5i, j, knockdown of LAMP2A in Mia-paca2 cells by vector-mediated RNAi significantly reversed the downregulation of IGF-1Rβ induced by 922. Thus, we suggested that 922 promoted HSP/HSC70 expression and LAMP2A redistribution, followed by enhanced formation of HSP/HSC70–LAMP2A complexes, which resulted in the degradation of IGF-1Rβ in a CMA-dependent fashion.

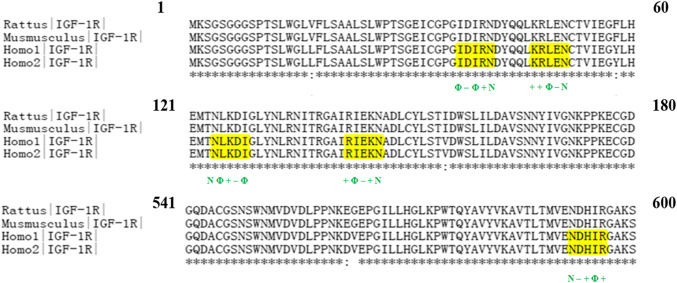

IGF-1Rβ has KFERQ-like pentapeptide sequences

Most of the known substrates of CMA have a KFERQ-like pentapeptide consensus sequence [26]. To identify peptides related to KFERQ of IGF-1R, we first compared amino acid sequences for the target proteins listed in Fig. 6. These sequences of IGF-1R were shown to be conserved in Homo sapiens (NP_000866.1, isoform 1; NP_001278787.1, isoform 2), Mus musculus (NP_034643.2) and Rattus norvegicus (NP_434694.1) by Clustal X software. According to the arrangement principles of peptide regions similar to KFERQ identified by Chiang and Shen et al. [19, 34], we found five sequence motifs possibly related to KFERQ in the human IGF-1R amino acid sequence using in silico analysis (yellow boxes). Thus, IGF-1R might be a potential target protein for CMA-dependent proteolysis.

Fig. 6.

IGF-1Rβ has KFERQ-like pentapeptide sequences. IGF-1R amino acidic sequence alignment and KFERQ-like motif (yellow boxes) from Rattus norvegicus (GenBank ID: NP_434694.1), Mus musculus (GenBank ID: NP_034643.2) and Homo sapiens (GenBank ID: NP_000866.1, isoform 1; NP_001278787.1, isoform 2). N, Asn; +, basic amino acid (K, R, H); −, acidic amino acid (D, E); Φ, hydrophobic amino acid (F, I, V, L)

Discussion

Insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF-1R) plays an essential role in tumorigenesis and aggravation. A significant number of cancers, including PC, have either overactivation and/or overexpression of IGF-1R, which indicates that targeting the IGF-1R signaling pathway is an attractive anticancer therapeutic approach. In addition to its tyrosine kinase inhibitor and receptor neutralization activities, the HSP90 inhibitor 17-AAG was shown to be a treatment option for PC through degradation of IGF-IRβ protein and inhibition of the downstream STAT3/hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) pathway by Lang et al. [11], suggesting that promotion of IGF-IRβ degradation could be another potential treatment for PC. Our study demonstrated that 922 could potentially dose- and time-dependently decrease IGF-1Rβ protein levels in PC cells compared with other well-known HSP90 inhibitors, such as GA and Y306zh. Meanwhile, the reduction of total IGF-1Rβ expression was consistent with inactivation of downstream ERK1/2 and AKT signaling in PC cells and pancreatic stellate cells of the tumor microenvironment (Supplemental Fig. 6). Additionally, 922 appeared to be more potent than GA in inhibiting PC cell viability, and the IC50 (~ 13 nM) of 922 was less than three times that of GA. Furthermore, 922 were synergistic with the first-line drug (gemcitabine) for PC (Supplemental Fig. 5). These findings showed that 922 has a potential to be used not only as a signal agent for IGF-1Rβ-overexpressing PC, but also in combination with chemotherapy.

Generally, HSP90 inhibitor-induced downregulation of multiple clients is thought to involve enhancement of their degradation via a ubiquitin-dependent proteasome pathway [14]. Recently, some researchers have found that inhibition of HSP90 chaperone function could induce the degradation of several clients (such as EGFR, KIT and α-synuclein) by the autophagy–lysosomal pathway [19, 21, 22]. Our present study showed that treatment with 922 for 6 h or 24 h induced proteasome-dependent degradation of AKT or CDK4 in PC cells, as Y306zh did [12]. However, we first addressed the role of the lysosomal pathway in 922-induced IGF-1Rβ degradation. Both proteasome pathway and lysosome pathway were involved in the IGF-1Rβ degradation induced by 922 for 6 h. However, the lysosome pathway was mainly mediated by IGF-1Rβ degradation after exposure to 922 for 24 h in PC cells, especially in Capan-2 cells. The ubiquitin–proteasome and autophagy–lysosome pathways are the two main routes for intracellular protein clearance in eukaryotic cells. Although these two pathways are assumed to be independent of each other in terms of the degradation mechanisms, increasing evidence suggests that there are numerous intersections between them. As an example, Ding et al. reported that inhibition of UPS could activate autophagy, and inhibition of autophagy in turn promoted ubiquitinated protein degradation [35]. After detection of chymotrypsin-like proteasomal activity, we found that, unlike MG132, the HSP90 inhibitors 922, GA and Y306zh did not directly affect the proteasomal activity at the enzyme level. Interestingly, at the intracellular level, these HSP90 inhibitors activated proteasome activity after treatment for 6 h but inhibited proteasomal activity after exposure for 24 h. Thus, we speculated that 922-induced lysosomal degradation of IGF-1Rβ was partially due to the inhibition of proteasome activity by 922 for 24 h. In addition, consistent with the results reported by Navab et al. [36], we found that IGF-1Rβ self-degradation was responsible for the lysosome pathway. HSP90 is essential in the assembly of the 26S proteasome. Yamano et al. reported that the addition of recombinant HSP90 to cell lysate stimulated chymotrypsin-like activity, and inhibition of HSP90 by GA abrogated the stimulatory effect of proteasome [37]. However, Opattova et al. found that GA could activate proteasomal activity to degrade intracellular misfolded Tau protein [38]. These controversial reports about proteasome activity might be related to the different dosages of HSP90 inhibitor administration and cell types. Several natural chemicals have been reported as HSP90 inhibitors, such as curcumin and EGCG, which potently inhibit proteasome activity to exhibit antitumor effects [39, 40]. Thus, we think that the proapoptotic effect of PC cells induced by 922 was associated with its inhibitory effect on proteasome activity.

The autophagy pathway is upstream of lysosomal degradation. LC3 is a specific marker for autophagosomes. During autophagosome formation, the endogenous cytosolic form of LC3 I conjugated to phosphatidylethanolamine is converted to membrane-bound LC3-phosphatidylethanolamine conjugate (LC3 II), which is recruited to autophagosomal membranes [41]. Our study showed that 922 markedly increased LC3 II levels and induced LC3 II-positive puncta, indicating increased autophagosome formation. It is important to distinguish the pseudomorphic effect on autophagosome formation derived from inhibition of lysosomal activity [42]. CQ, as a weak alkaline compound, accumulates in and neutralizes the acidity of lysosomes to inhibit lysosome activity, which prevented autophagy through blockage of autophagosome fusion and degradation [43]. We also observed substantial accumulation of LC3 II fluorescence and LysoTracker probes after exposure to 50 μM CQ for 6 or 24 h, which was the result of lysosomal dysfunction. However, 922 did not induce LysoTracker probes to accumulate in the lysosome, but further increased LC3 II expression in combination with CQ, suggesting that 922-induced LC3 II accumulation was associated with the promotion of autophagic flux rather than the inhibition of lysosomal activity. A similar study reported that inhibition of HSP90 by GA or 17-AAG could modestly trigger autophagic flux and induce HSP90 client IKK degradation through the macroautophagy pathway [20, 44]. Unexpectedly, blockade of macroautophagy with 3 MA or ATG5 (a specific gene required for macroautophagy) siRNA also did not rescue the degradation of IGF-1Rβ by 922. Thus, we showed that although 922 promoted autophagic flux, 922-induced IGF-1Rβ degradation was independent of macroautophagy.

CMA is a selective degradation pathway for substrates with KFERQ-like motif. HSC70 and LAMP2A are key effectors of the CMA pathway; the former is responsible for recognition of a specific substrate with a KFERQ-like sequence, and the latter is in charge of translocation of the target protein to the lysosome [45]. Previous reports showed that either enhanced expression or translocation of HSC70 and LAMP2A activated CMA [46–48]. We found that 922 increased HSC70/HSP70 and LAMP2A expressions and promoted the interactions between HSC70/HSP70 and LAMP2A, as well as redistributed HSC70/HSP0 and LAMP2A to the nucleus of PC cells, indicating that 922 could induce CMA activity in PC cells. Meanwhile, we observed that 922 significantly increased the amount of HSP/HSC70 associated with IGF-1Rβ and LAMP2A. LAMP2A is as a rate-limiting enzyme. Knockdown of LAMP2A is not ensured to exercise the CMA degradation, even if lysosomal membrane HSC70 exists [26, 33]. After silencing of LAMP2A, we found that 922-induced IGF-1Rβ degradation was significantly reversed in PC cells. In addition, we first showed that IGF-1Rβ is highly conserved and contains five KFERQ-like sequences based on the principles of Ali and Chiang et al. [34, 49]. These results suggested that IGF-1Rβ could be a CMA substrate and degraded by 922 in a CMA fashion. However, whether 922-induced CMA participated in PC therapy has not been investigated until now. There are some CMA substrates, such as hexokinase II and hypoxia-inducible factor-1α, which are degraded by CMA to promote metabolic catastrophe or cancer cell death [50, 51]. However, recent studies have shown that elevated expression of LAMP2A was observed in many tumors, including gastric cancer, colon cancer, breast cancer and NSCLC. These reports indicated that inhibition of CMA activity by LAMP2A deficiency could be an efficient strategy for cancer therapy [52–54]. We found that the population of late apoptotic cells was increased after knockdown of LAMP2A in combination with 922 treatment (Supplemental Fig. 3). The underlying mechanism should be clarified in future experiments to explain the efficacy of combination therapy of silencing LAMP2A and HSP90 inhibitors for PC. Furthermore, we found that IR, another client of HSP90 with high homology to IGF-1R, has five KFERQ-like pentapeptide consensus sequences (Supplemental Fig. 4), indicating that IR might be degraded by 922 through the CMA pathway. Because an isoform of IR and hybrid IGF-IR/IR receptors were overexpressed on a variety of cancers, including breast cancer, prostate cancer and osteoblastogenesis [3], cotargeting IR and IGF-1R using an HSP90 inhibitor in cancer would be a more useful therapeutic option than targeting IGF-1R alone. A report from Lee et al. showed that the HSP90 inhibitor 922 improved insulin resistance in obese mice and reversed hyperglycemia in the diabetic mouse [55]. Taken together, we speculated that the HSP90 inhibitor 922 may be a useful strategy for the treatment of PC along with insulin resistance or diabetes in the near future.

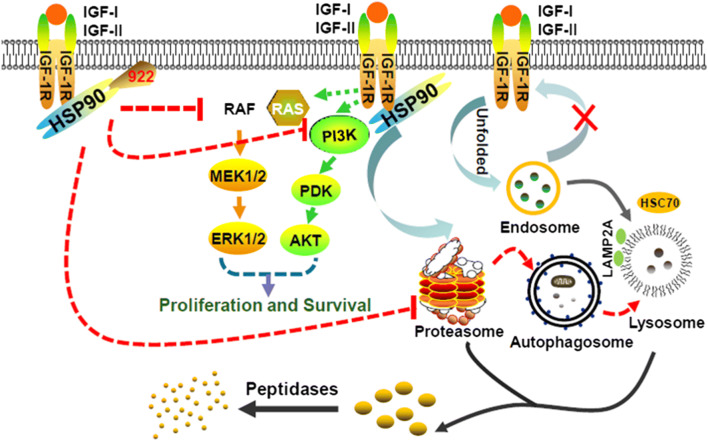

Our current study showed that the HSP90 inhibitor 922 downregulated IGF-1Rβ protein and its downstream signaling molecules (p)/AKT and p-ERK1/2, accompanied by effective inhibition of cell viability and enhanced apoptosis of PC cells. In addition to the proteasome-dependent pathway, the CMA-mediated protein degradation pathway partially participated in 922-induced IGF-1Rβ degradation in PC cells by promoting the association between HSP/HSC70 and IGF-1Rβ or LAMP2A (Fig. 7). These findings first demonstrated that the CMA pathway is involved in 922-induced IGF-1Rβ degradation and suggested a potential therapeutic strategy involving 922 for PC patients with IGF-1Rβ overexpression.

Fig. 7.

Schematic representation of the proposed mechanism for 922-induced IGF-1Rβ degradation in PC cells. Long-term treatment with 922 reduced proteasome activity and promoted IGF-1Rβ degradation through the CMA pathway. The downstream signaling pathways PI3 K and MAPK were significantly attenuated by 922, thereby suppressing proliferation and survival of PC cells

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81573466). We thank Ms. Long Long for her assistance in the high content analysis experiments using an InCell Analyzer 1000.

Abbreviations

- 922

NVP-AUY922

- ATG5

Autophagy-related 5

- CHX

Cycloheximide

- CMA

Chaperone-mediated autophagy

- CQ

Chloroquine

- DAPI

4,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole

- GA

Geldanamycin

- HSC70

Heat shock cognate 70 kDa

- HSP70

Heat shock 70 kDa protein

- HSP90

Heat shock protein 90

- IGF-IR

Insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor

- IC50

The drug concentration that inhibited cell growth by 50%

- JAK

Janus kinase

- LAMP2A

Lysosome-associated membrane protein 2

- 3 MA

3 Methyladenine

- LC3

Microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (MAP1LC3)

- MAPK

Mitogen-activated protein kinase

- PC

Pancreatic cancer

- PI3K

Phosphatidyl inositol 3-kinase

- PI

Propidium iodide

- STAT

Signal transducer and activator of transcription

- UPS

Ubiquitin–proteasome system

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Nina Xue and Fangfang Lai contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Jing Jin, Phone: +86-10-6316-5207, Email: rebeccagold@imm.ac.cn.

Xiaoguang Chen, Phone: +86-10-6316-5207, Email: chxg@imm.ac.cn.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(1):7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergmann U, Funatomi H, Yokoyama M, Beger HG, Korc M. Insulin-like growth factor I overexpression in human pancreatic cancer: evidence for autocrine and paracrine roles. Can Res. 1995;55(10):2007–2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pollak M. Targeting insulin and insulin-like growth factor signalling in oncology. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2008;8(4):384–392. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rieder S, Michalski CW, Friess H, Kleeff J. Insulin-like growth factor signaling as a therapeutic target in pancreatic cancer. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2011;11(5):427–433. doi: 10.2174/187152011795677454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.LeRoith D, Werner H, Beitner-Johnson D, Roberts CT., Jr Molecular and cellular aspects of the insulin-like growth factor I receptor. Endocr Rev. 1995;16(2):143–163. doi: 10.1210/edrv-16-2-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ullrich A, Gray A, Tam AW, Yang-Feng T, Tsubokawa M, Collins C, Henzel W, Le Bon T, Kathuria S, Chen E, et al. Insulin-like growth factor I receptor primary structure: comparison with insulin receptor suggests structural determinants that define functional specificity. EMBO J. 1986;5(10):2503–2512. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04528.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bondar VM, Sweeney-Gotsch B, Andreeff M, Mills GB, McConkey DJ. Inhibition of the phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase–AKT pathway induces apoptosis in pancreatic carcinoma cells in vitro and in vivo. Mol Cancer Ther. 2002;1(12):989–997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kulik G, Klippel A, Weber MJ. Antiapoptotic signalling by the insulin-like growth factor I receptor, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, and Akt. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17(3):1595–1606. doi: 10.1128/MCB.17.3.1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Breinig M, Mayer P, Harjung A, Goeppert B, Malz M, Penzel R, Neumann O, Hartmann A, Dienemann H, Giaccone G, Schirmacher P, Kern MA, Chiosis G, Rieker RJ. Heat shock protein 90-sheltered overexpression of insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor contributes to malignancy of thymic epithelial tumors. Clin Cancer Research. 2011;17(8):2237–2249. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Isaacs JS, Xu W, Neckers L. Heat shock protein 90 as a molecular target for cancer therapeutics. Cancer Cell. 2003;3(3):213–217. doi: 10.1016/S1535-6108(03)00029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lang SA, Moser C, Gaumann A, Klein D, Glockzin G, Popp FC, Dahlke MH, Piso P, Schlitt HJ, Geissler EK, Stoeltzing O. Targeting heat shock protein 90 in pancreatic cancer impairs insulin-like growth factor-I receptor signaling, disrupts an interleukin-6/signal-transducer and activator of transcription 3/hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha autocrine loop, and reduces orthotopic tumor growth. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(21):6459–6468. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xue N, Jin J, Liu D, Yan R, Zhang S, Yu X, Chen X. Antiproliferative effect of HSP90 inhibitor Y306zh against pancreatic cancer is mediated by interruption of AKT and MAPK signaling pathways. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2014;14(7):671–683. doi: 10.2174/1568009614666140908101523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zitzmann K, Ailer G, Vlotides G, Spoettl G, Maurer J, Goke B, Beuschlein F, Auernhammer CJ. Potent antitumor activity of the novel HSP90 inhibitors AUY922 and HSP990 in neuroendocrine carcinoid cells. Int J Oncol. 2013;43(6):1824–1832. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2013.2130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wandinger SK, Richter K, Buchner J. The Hsp90 chaperone machinery. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(27):18473–18477. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800007200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pratt WB, Morishima Y, Osawa Y. The Hsp90 chaperone machinery regulates signaling by modulating ligand binding clefts. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(34):22885–22889. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800023200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palacios C, Martin-Perez R, Lopez-Perez AI, Pandiella A, Lopez-Rivas A. Autophagy inhibition sensitizes multiple myeloma cells to 17-dimethylaminoethylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin-induced apoptosis. Leuk Res. 2010;34(11):1533–1538. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He W, Ye X, Huang X, Lel W, You L, Wang L, Chen X, Qian W. Hsp90 inhibitor, BIIB021, induces apoptosis and autophagy by regulating mTOR–Ulk1 pathway in imatinib-sensitive and -resistant chronic myeloid leukemia cells. Int J Oncol. 2016;48(4):1710–1720. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2016.3382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu KS, Liu H, Qi JH, Liu QY, Liu Z, Xia M, Xing GW, Wang SX, Wang YF. SNX-2112, an Hsp90 inhibitor, induces apoptosis and autophagy via degradation of Hsp90 client proteins in human melanoma A-375 cells. Cancer Lett. 2012;318(2):180–188. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shen S, Zhang P, Lovchik MA, Li Y, Tang L, Chen Z, Zeng R, Ma D, Yuan J, Yu Q. Cyclodepsipeptide toxin promotes the degradation of Hsp90 client proteins through chaperone-mediated autophagy. J Cell Biol. 2009;185(4):629–639. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200810183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qing G, Yan P, Xiao G. Hsp90 inhibition results in autophagy-mediated proteasome-independent degradation of IkappaB kinase (IKK) Cell Res. 2006;16(11):895–901. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7310109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsueh YS, Yen CC, Shih NY, Chiang NJ, Li CF, Chen LT. Autophagy is involved in endogenous and NVP-AUY922-induced KIT degradation in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Autophagy. 2013;9(2):220–233. doi: 10.4161/auto.22802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Riedel M, Goldbaum O, Schwarz L, Schmitt S, Richter-Landsberg C. 17-AAG induces cytoplasmic alpha-synuclein aggregate clearance by induction of autophagy. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(1):e8753. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levine B, Klionsky DJ. Development by self-digestion: molecular mechanisms and biological functions of autophagy. Dev Cell. 2004;6(4):463–477. doi: 10.1016/S1534-5807(04)00099-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yorimitsu T, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy: molecular machinery for self-eating. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12(Suppl 2):1542–1552. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Majeski AE, Dice JF. Mechanisms of chaperone-mediated autophagy. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36(12):2435–2444. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Massey AC, Kaushik S, Sovak G, Kiffin R, Cuervo AM. Consequences of the selective blockage of chaperone-mediated autophagy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(15):5805–5810. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507436103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen WY, Chang FR, Huang ZY, Chen JH, Wu YC, Wu CC. Tubocapsenolide A, a novel withanolide, inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 cells by thiol oxidation of heat shock proteins. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(25):17184–17193. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709447200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumar B, Hanson AJ, Prasad KN. Sensitivity of proteasome to its inhibitors increases during cAMP-induced differentiation of neuroblastoma cells in culture and causes decreased viability. Cancer Lett. 2004;204(1):53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2003.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiang H, Sun J, Xu Q, Liu Y, Wei J, Young CY, Yuan H, Lou H. Marchantin M: a novel inhibitor of proteasome induces autophagic cell death in prostate cancer cells. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4:e761. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vivanco I, Sawyers CL. The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase AKT pathway in human cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2(7):489–501. doi: 10.1038/nrc839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu Y, Hamza A, Zhang T, Gu M, Zou P, Newman B, Li Y, Gunatilaka AA, Zhan CG, Sun D. Withaferin A targets heat shock protein 90 in pancreatic cancer cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;79(4):542–551. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuma A, Hatano M, Matsui M, Yamamoto A, Nakaya H, Yoshimori T, Ohsumi Y, Tokuhisa T, Mizushima N. The role of autophagy during the early neonatal starvation period. Nature. 2004;432(7020):1032–1036. doi: 10.1038/nature03029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kiffin R, Christian C, Knecht E, Cuervo AM. Activation of chaperone-mediated autophagy during oxidative stress. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15(11):4829–4840. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-06-0477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chiang HL, Dice JF. Peptide sequences that target proteins for enhanced degradation during serum withdrawal. J Biol Chem. 1988;263(14):6797–6805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ding WX, Ni HM, Gao W, Yoshimori T, Stolz DB, Ron D, Yin XM. Linking of autophagy to ubiquitin-proteasome system is important for the regulation of endoplasmic reticulum stress and cell viability. Am J Pathol. 2007;171(2):513–524. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Navab R, Chevet E, Authier F, Di Guglielmo GM, Bergeron JJ, Brodt P. Inhibition of endosomal insulin-like growth factor-I processing by cysteine proteinase inhibitors blocks receptor-mediated functions. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(17):13644–13649. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100019200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamano T, Mizukami S, Murata S, Chiba T, Tanaka K, Udono H. Hsp90-mediated assembly of the 26 S proteasome is involved in major histocompatibility complex class I antigen processing. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(42):28060–28065. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803077200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Opattova A, Filipcik P, Cente M, Novak M. Intracellular degradation of misfolded tau protein induced by geldanamycin is associated with activation of proteasome. J Alzheimer’s Dis (JAD) 2013;33(2):339–348. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-121072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nam S, Smith DM, Dou QP. Ester bond-containing tea polyphenols potently inhibit proteasome activity in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(16):13322–13330. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004209200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yin Z, Henry EC, Gasiewicz TA. (−)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate is a novel Hsp90 inhibitor. Biochemistry. 2009;48(2):336–345. doi: 10.1021/bi801637q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kabeya Y, Mizushima N, Ueno T, Yamamoto A, Kirisako T, Noda T, Kominami E, Ohsumi Y, Yoshimori T. LC3, a mammalian homologue of yeast Apg8p, is localized in autophagosome membranes after processing. EMBO J. 2000;19(21):5720–5728. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.21.5720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hansen TE, Johansen T. Following autophagy step by step. BMC Biol. 2011;9:39. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-9-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rubinsztein DC, Gestwicki JE, Murphy LO, Klionsky DJ. Potential therapeutic applications of autophagy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6(4):304–312. doi: 10.1038/nrd2272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Samarasinghe B, Wales CT, Taylor FR, Jacobs AT. Heat shock factor 1 confers resistance to Hsp90 inhibitors through p62/SQSTM1 expression and promotion of autophagic flux. Biochem Pharmacol. 2014;87(3):445–455. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bandyopadhyay U, Kaushik S, Varticovski L, Cuervo AM. The chaperone-mediated autophagy receptor organizes in dynamic protein complexes at the lysosomal membrane. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28(18):5747–5763. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02070-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bejarano E, Cuervo AM. Chaperone-mediated autophagy. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2010;7(1):29–39. doi: 10.1513/pats.200909-102JS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kaushik S, Cuervo AM. Methods to monitor chaperone-mediated autophagy. Methods Enzymol. 2009;452:297–324. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)03619-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li W, Yang Q, Mao Z. Chaperone-mediated autophagy: machinery, regulation and biological consequences. Cell Mol Life Sci (CMLS) 2011;68(5):749–763. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0565-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ali AB, Nin DS, Tam J, Khan M. Role of chaperone mediated autophagy (CMA) in the degradation of misfolded N-CoR protein in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(9):e25268. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xia HG, Najafov A, Geng J, Galan-Acosta L, Han X, Guo Y, Shan B, Zhang Y, Norberg E, Zhang T, Pan L, Liu J, Coloff JL, Ofengeim D, Zhu H, Wu K, Cai Y, Yates JR, Zhu Z, Yuan J, Vakifahmetoglu-Norberg H. Correction: Degradation of HK2 by chaperone-mediated autophagy promotes metabolic catastrophe and cell death. J Cell Biol. 2016;212(7):881–882. doi: 10.1083/jcb.20150304403082016c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hubbi ME, Hu H, Kshitiz Ahmed I, Levchenko A, Semenza GL. Chaperone-mediated autophagy targets hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha (HIF-1alpha) for lysosomal degradation. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(15):10703–10714. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.414771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhou J, Yang J, Fan X, Hu S, Zhou F, Dong J, Zhang S, Shang Y, Jiang X, Guo H, Chen N, Xiao X, Sheng J, Wu K, Nie Y, Fan D. Chaperone-mediated autophagy regulates proliferation by targeting RND3 in gastric cancer. Autophagy. 2016;12(3):515–528. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2015.1136770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Saha T. LAMP2A overexpression in breast tumors promotes cancer cell survival via chaperone-mediated autophagy. Autophagy. 2012;8(11):1643–1656. doi: 10.4161/auto.21654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Suzuki J, Nakajima W, Suzuki H, Asano Y, Tanaka N. Chaperone-mediated autophagy promotes lung cancer cell survival through selective stabilization of the pro-survival protein, MCL1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;482(4):1334–1340. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee JH, Gao J, Kosinski PA, Elliman SJ, Hughes TE, Gromada J, Kemp DM. Heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) inhibitors activate the heat shock factor 1 (HSF1) stress response pathway and improve glucose regulation in diabetic mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;430(3):1109–1113. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.