Abstract

Actin has emerged as a versatile regulator of gene transcription. Cytoplasmatic actin regulates mechanosensitive-signaling pathways such as MRTF–SRF and Hippo-YAP/TAZ. In the nucleus, both polymerized and monomeric actin directly interfere with transcription-associated molecular machineries. Natural actin-binding compounds are frequently used tools to study actin-related processes in cell biology. However, their influence on transcriptional regulation and intranuclear actin polymerization is poorly understood to date. Here, we analyze the effects of two representative actin-binding compounds, Miuraenamide A (polymerizing properties) and Latrunculin B (depolymerizing properties), on transcriptional regulation in primary cells. We find that actin stabilizing and destabilizing compounds inversely shift nuclear actin levels without a direct influence on polymerization state and intranuclear aspects of transcriptional regulation. Furthermore, we identify Miuraenamide A as a potent inducer of G-actin-dependent SRF target gene expression. In contrast, the F-actin-regulated Hippo-YAP/TAZ axis remains largely unaffected by compound-induced actin aggregation. This is due to the inability of AMOTp130 to bind to the amorphous actin aggregates resulting from treatment with miuraenamide. We conclude that actin-binding compounds predominantly regulate transcription via their influence on cytoplasmatic G-actin levels, while transcriptional processes relying on intranuclear actin polymerization or functional F-actin networks are not targeted by these compounds at tolerable doses.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00018-018-2919-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Latrunculin, Miuraenamide, MRTF-A, Nuclear actin, Transcription, YAP

Introduction

Being one of the most abundant proteins in the cell, actin has been extensively studied over the past decades. Owing to its ability to polymerize from monomers into an organized filamentous network, the actin cytoskeleton plays a key role in cell division, migration, and intracellular transport [1]. More recently, actin has drawn attention as a functional and regulatory element of gene transcription, which is closely associated with its long-debated role in mammalian cell nuclei [2–5]. For example, monomeric actin has been identified and functionally characterized as a constituent of several chromatin-remodeling complexes [6, 7]. Furthermore, binding of nuclear actin is required for the activity of all three RNA polymerases [8–10] and for proper histone modification [11–13].

In close collaboration with its nuclear counterpart, also cytoplasmatic actin is known to regulate transcription in a variety of cell lines [14]. This has been described in detail for the family of myocardin-related transcription factors (MRTFs), whose nuclear translocation and thereafter association with serum response factor (SRF) at CArG-box sequences is inhibited by binding of monomeric actin in both the nuclear and the cytoplasmatic compartment [15–17]. A similar, though less directly mediated effect of actin polymerization has been reported for the yes-associated protein (YAP) [18–20], a mechanosensitive transcription factor of the Hippo-YAP/TAZ pathway [21, 22].

Actin-binding compounds are frequently used to study actin-related signaling mechanisms in cell biology [23]. Examples include the targeting of DNA damage response pathways, or the activation of mechanosensitive-signaling cascades [24–26]. However, a systematic analysis of the transcriptional effects of actin-binding compounds in living cells has not been reported to date. In particular, the influence of actin-binding compounds on nuclear actin structure and function remains largely elusive.

In the present study, we analyze the impact of Miuraenamide A [27, 28], a potent actin polymerizing compound from Paraliomyxa miuraensis [28, 29], and the commercially available actin depolymerizer Latrunculin B on nuclear actin dynamics and transcriptional regulation. We demonstrate that these compounds modulate the concentration of nuclear actin, while intranuclear polymerization state and actin-dependent transcriptional machineries remain largely unaffected. Furthermore, we show that compound-induced actin aggregation in the cytoplasm selectively activates MRTF but not YAP, promoting MRTF–SRF as a key regulatory target of actin-binding compounds in primary cells.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) were purchased from Promocell (Heidelberg, Germany). Cells were cultivated with ECGM Kit enhanced (PELO Biotech, Planegg, Germany) supplemented with 10% FCS (PAA Laboratories GmbH, Pasching, Austria). All experiments were performed in passage #6 and cells were cultivated at 37 °C under 5% CO2 atmosphere.

NIH3T3 cells were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA) and cultivated with DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS. Cell culture media were supplemented with 1% penicillin/streptomycin (PAN-Biotech, Aidenbach, Germany).

Actin-binding compounds

Myxobacterial compound Miuraenamide A was provided by the lab of Prof. Uli Kazmaier (Institute for Organic Chemistry, Saarland University, Saarbruecken, Germany) [28]. The compound was stored at − 20 °C as 10 mM DMSO stock solution and used at working concentrations of 50–100 nM containing < 0.1% DMSO. Latrunculin B was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA) and handled according to manufacturer’s instructions. Due to the steep dose–response curves of actin-binding compounds, the concentration of Miuraenamide A was adjusted for each experiment regarding cell density, culture conditions, and the time of stimulation.

Plasmids and transfections

Primary endothelial cells were transiently transfected using the Targefect-HUVEC™ transfection kit (Targeting Systems, El Cajon, CA, USA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Live-cell imaging and all other experiments were performed between 24 and 48 h after transfection.

MRTF-A-GFP was a gift from Robert Grosse. mCherry-C3-hYAP1 was recloned from Addgene plasmid #17843 (pEGFP-C3-hYAP1) using the standard cloning procedures. pCAG–mGFP–Actin, mCherry–Actin-7, and YFP–NLS–β-Actin were from Addgene (#21948, #54966 and #60613). HA-AMOTp130 was a gift from Bin Zhao. Luciferase reporter constructs pGL4.74 (renilla control) and pGL4.34 (SRE–RE, [30]) were purchased from Promega (Madison, WI, USA), the 8xGTTIC YAP/TAZ firefly construct was from Addgene (#34615).

Luciferase reporter gene assays

Luciferase reporter gene assays were performed using an Orion II microplate luminometer equipped with Simplicity Software (Bad Wildbad, Germany). Samples were stimulated 24 h after transfection and analyzed in duplicates. Firefly reporter RLUs were normalized to a constitutive renilla control (10:1 transfection ratio) using the Dual Luciferase reporter gene assay kit from Promega (Madison, WI, USA).

Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS)

FCS measurements were performed on a Leica TCS SP8 SMD microscope combined with a Picoquant LSM Upgrade Kit. For all measurements, a 63× Zeiss water immersion lens and ibidi 8 well µ-slides with glass bottoms were used. The effective volume (Veff) and structure parameter (κ) were measured at the start of each experiment using 1 nM ATTO488 dye solution (ATTO-TEC GmbH, Siegen, Germany). Three different points were measured in every cell nucleus for 45 s per point. This process was repeated at four different timepoints (0, 5, 15, and 25 min) with the respective compound being added after the zero-timepoint measurement.

FCS curves were analyzed using the Picoquant SymPhoTime V 5.2.4.0 software and fitted with a single diffusing species and a triplet state (Eq. 1). Control measurements without the addition of compounds were performed over the same timepoints to verify that photobleaching does not influence the analysis:

| 1 |

Raster image correlation spectroscopy (RICS)

The RICS measurements were performed on a home-built PIE-FI microscope and calibrations were performed on single-measurement basis, as described elsewhere [31]. The following laser lines were used for excitation: 475 nm for GFP-actin and 561 nm for mCherry–actin. The laser power was measured using a slide power meter to be ~ 1.1 µW at the sample level. The measurements were performed using a 100× oil NA 1.49 objective. Image calculations from the raw photon data and subsequent analysis were performed with our Microtime Image Analysis (MIA) software. MIA is a stand-alone program (MATLAB; The MathWorks GmbH) for global, serial, and automated analysis of CLSM images (using continuous-wave excitation or PIE) that can perform RICS and ccRICS, as well as other image correlation methods. To localize the GFP- and mCherry-labeled actin, a wide-field imaging system was used. For prolonged imaging conditions at 37 °C, a home-built autofocus system was used to avoid the possible focal drift in z direction. The wide field and autofocus systems are further described in [31].

RICS and ccRICS were performed consecutively on the cytoplasm and on the nucleus. The data were obtained recording 150 frames per z position (12 × 12 μm or 300 × 300 pixels) at a frame time of τf = 1 s, interframe time τif = ~ 0.5 s, line time τl = 3.33 ms, pixel dwell time τp = 11.11 μs, and pixel size δr = 40 nm. The RICS and ccRICS processing was performed as explained elsewhere [31].

The RICS experiments were corrected for cellular movement by applying a moving average correction prior to correlation of the image. For analyzing the different cellular regions, we designated an arbitrary ROI, where the unwanted pixels (e.g., due to heterogeneities in the nucleus or from pixels outside of the cell) were removed. The correlation functions were then determined using the ARICS algorithm. A two-component model assuming a 3D Gaussian focus shape was used for fitting the SACFs (Eq. 2):

| 2 |

where ξ and ψ denote the spatial lag in pixels along the fast and slow scanning axes, respectively. The scanning parameters, , , and , represent the pixel dwell time, the line time (i.e., the time difference between the start of two consecutive lines), and the pixel size, respectively. and are the lateral and axial focus sizes, respectively, defined as the distance from the focus center to the point, where the signal intensity has decreased to 1/e2 of the maximum. The shape factor is 2−3/2 for a 3D Gaussian. The vertical lines denote that the absolute value should be taken over the absolute time lag. The correlation at zero lag time was omitted from analysis due to the contribution of uncorrelated shot noise.

The fitting was used to extract the quantitative number of mobile and immobile fraction of molecules. The “immobile” fraction refers to particles that did not move significant on the time necessary to image them (~ 30 ms), but are dynamic on the timescale of frames; otherwise, they would have been removed by the moving average correction. A single, static component was used for fitting the SCCFs (Eq. 3) and used to extract the quantitative number of “immobile” molecules:

| 3 |

where sx and sy are the spatial offsets in x and y directions between the two images, respectively.

The normalized fraction of polymerizing actin (Fig. 4c, d) was obtained by the division of the SCCF amplitude by the SACF amplitude of the EGFP-labeled actin.

Fig. 4.

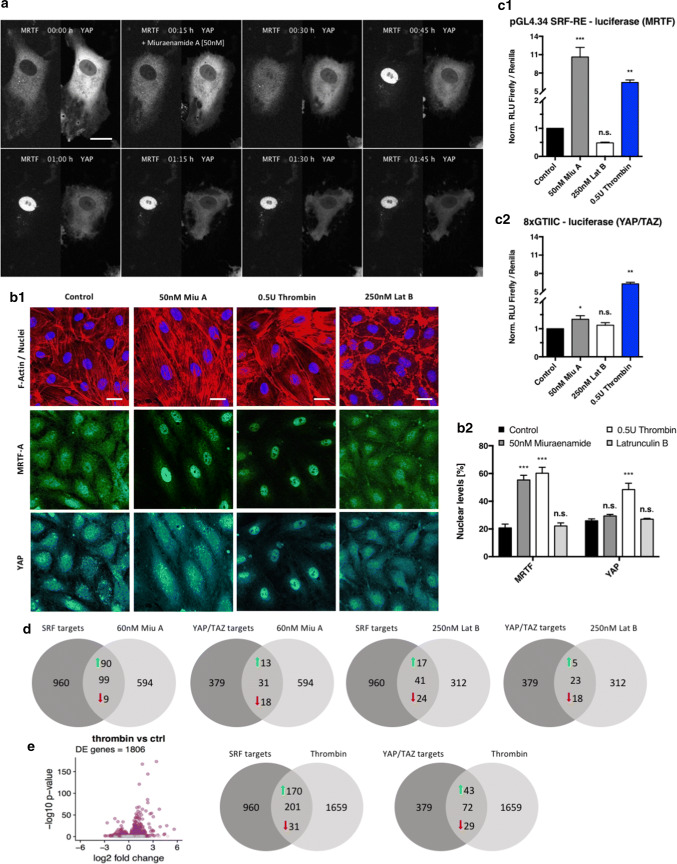

Miuraenamide A activates MRTF-A but not YAP. a Live-cell imaging sequence of MRTF-A-GFP and hYAP1-mCherry co-expressing endothelial cell. MRTF-A and YAP subcellular localization was imaged over a time span of 90 min after stimulation with 50 nM Miuraenamide A at t = 15 min. Bar = 30 µm. b1 Confluent HUVEC were stimulated for 5 h with either 50 nM Miuraenamide A, 250 nM Latrunculin B or 0.5 U thrombin and immunostained for F-actin, MRTF-A, and YAP. Bars = 30 µm. b2 Quantification of nuclear MRTF-A and YAP levels for the experiment shown in b1. Nuclear protein levels are expressed as nuclear signal intensity divided by total cellular intensity. c Dual Luciferase reporter gene assays for SRF response element (c1) and YAP/TAZ promotor (c2). Luciferase reporter activity is expressed as firefly RLU normalized to the constitutive renilla control construct. d Number of significantly up- and downregulated, known SRF and YAP/TAZ target genes in response to stimulation with Miuraenamide A and Latrunculin B. Green and red arrows indicate the numbers of up- and downregulated genes in the respective settings. Numbers in the left circles indicate the total numbers of known SRF or YAP/TAZ target genes. Numbers in the right circles indicate the total numbers of regulated genes after stimulation with Miuraenamide A, Latrunculin B or thrombin. e Volcano plot of gene expression and number of up- and downregulated, known SRF and YAP/TAZ target genes after stimulation with 0.5 U thrombin versus control. The colored points indicate significantly differentially expressed genes (FDR < 0.1). The numbers in circle diagrams apply, as described in d

Laser scanning confocal microscopy

Confocal images were acquired using a Leica TCS SP8 SMD microscope equipped with the following HC PL APO objectives: 40×/1.30 OIL, 63×/1.40 OIL, 63×/1.20 W CORR. Pinhole size was adjusted to 1.0 airy units and scanning was performed at 400 Hz. An average of four frames was acquired for every channel in sequential scanning mode. The following laser lines and excitation sources were used: 405 nm (diode), 561 nm (DPSS), 488 nm, and 647 nm (both argon). Live-cell imaging was performed at 37 °C under 5% CO2 atmosphere and 80% humidity using a bold line incubation system from Okolab (Pozzuoli, Italy).

Antibodies and staining reagents

Rhodamine phalloidin and Hoechst 33342 were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA) and used at a dilution of 1:400 (phalloidin) or at a final working concentration of 0.5 µg/ml (Hoechst). FluorSave Reagent mounting medium was purchased from Merck Millipore (Darmstadt, Germany).

Immunofluorescence stainings and nuclear run on assays

For immunofluorescence stainings, cells were rinsed with PBS + Ca2+/Mg2+ followed by 10 min fixation with 4% EM grade pFA (Polysciences Inc., Warrington, PA, USA). After 10 min washing with PBS, samples were permeabilized for 10 min with 0.5% TX-100 in PBS (Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany). Unspecific binding was blocked by 30 min incubation with 5% goat serum (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) in PBS + 0.2% BSA (Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany) and cells were incubated overnight (16 h) with primary antibodies (1:200 dilution, Table 1) in PBS + 0.2% BSA (4 °C). After 3 × 10 min washing with PBS, samples were incubated with secondary antibodies (1:500 dilution, Table 2), rhodamine phalloidin, and Hoechst for 1 h, washed again 3 × 10 min with PBS, and sealed with one drop of mounting medium.

Table 1.

Primary antibodies

| Antibody | Supplier |

|---|---|

| MRTF-A (G-8) mouse mAb IgG2a, sc-390324 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA |

| YAP (B-8) mouse mAb IgG2a, sc-398182 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA |

| YAP (D8H1X) XP® rabbit mAb | Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA |

| Angiomotin (D2O4H) rabbit mAb | Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA |

| Monoclonal Anti-BrdU Clone BU-33 | Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA |

| HA-Tag (6E2) mouse mAb | Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA |

| Histone H3 (acetyl K9), mouse mAb IgG1, ab12179 | Abcam, Cambridge, UK |

| Histone H3, ab1791 | Abcam, Cambridge, UK |

| Histone H3 (trimethyl K4), mouse mAb IgG1, ab12209 | Abcam, Cambridge, UK |

| Histone H3 (dimethyl K4), mouse mAb IgG1, 25254 | BPS Bioscience, CA, USA |

| POLR1A, rabbit mAb IgG1, HPA031513 | Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA |

| Anti-ACTB, mouse mAb IgG1, AMAB91241 | Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA |

Table 2.

Secondary antibodies

| Antibody | Supplier |

|---|---|

| Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG (H + L), A-11001 | ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, USA |

| Alexa Fluor 647 goat anti-rabbit IgG (H + L), A-21245 | ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, USA |

| Alexa Fluor 546 goat anti-mouse IgG (H + L), A-11030 | ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, USA |

| Goat anti-rabbit IgG (H + L)-HRP conjugate #1706515 | Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA |

| Goat anti-mouse IgG (H + L)-HRP conjugate BZL07046 | Biozol, Eching, Germany |

Nuclear actin stainings were performed with cytoskeleton stabilizing buffers and 2% glutaraldehyde fixation as previously described [32].

For quantification of 5-FU incorporation (nuclear run on assay), cells were pretreated with either Miuraenamide A, Latrunculin B, or Actinomycin D (positive control) and incubated with 5 mM 5-fluorouracil for the last 90 min of stimulation. Nuclear 5-FU foci were quantified using the ImageJ particle analyzer tool.

Duolink proximity ligation assay (PLA)

Duolink proximity ligation assays (PLA) were performed using the Duolink® PLA kit from Sigma-Aldrich (Taufkirchen, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All reagents were stored and handled according to the available online instructions. 2% BSA in PBS was used as blocking reagent and antibody diluent.

Immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) and western blot (SDS-PAGE)

Co-IP experiments were performed using the standard NP-40 lysis buffer (Table 3). Cell lysates were incubated with 3 µg precipitation antibody (sc-398182) for 2 h at room temperature followed by addition of 40 µl protein G agarose suspension (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). After 2 h incubation at room temperature, beads were washed 3× with 500 µl cold PBS, resuspended in 50 µl 2× sample buffer, and boiled for 5 min at 95 °C.

Table 3.

NP-40 lysis buffer recipe

| NP-40 lysis buffer (pH 7.2) |

|---|

| 150 mM NaCl |

| 1% Nonidet P-40 |

| 50 mM Tris HCl |

| 0.25% Deoxycholate |

| 1 mM EGTA |

| 1 mM PMSF (before use) |

| Complete® protease inhibitor 1:10 (before use) |

SDS-PAGE was performed with the standard tank blotting procedures, 10% polyacrylamide gels, and Amersham nitrocellulose membranes (GE Healthcare, Munich, Germany). Total protein was quantified using Stain-Free technology. Antibody-based protein detection was carried out using HRP-coupled secondary antibodies and Amersham ECL reagent (GE Healthcare, Munich, Germany) on a ChemiDoc Touch imaging system.

Transcriptome analysis

mRNA was cleaned up from cell lysates with Sera-Mag carboxylated magnetic beads (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) and reverse transcribed using a slightly modified SCRB-seq protocol [33]. During reverse transcription, sample-specific barcodes and unique molecular identifiers were incorporated into first strand cDNA. Next, samples were pooled and excess primers digested by Exonuclease I (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA).

cDNA was preamplified using KAPA HiFi HotStart polymerase (KAPA Biosystems). Sequencing libraries were constructed from cDNA using the Nextera XT Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Resulting libraries were quantified and sequenced at 10 nM on a HiSeq 1500 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). To obtain genewise expression values, raw sequencing data were processed using the zUMIs pipeline [34] using the Human genome build hg19 and Ensembl gene models (GRCh37.75).

Transcriptome analysis was performed using the free statistical software R (v. 3.4.2). DESeq2 package (v.1.16.1) was used for normalization and differential expression (DE) analysis. DESeq2 models transcriptional count data using negative binomial distribution. Additional filtering was done using HTSFilter (v.1.16.0) to remove constant, lowly expressed genes. The final gene set consisted of 15,232 genes.

DE testing was based on Wald test. Multiple testing was accounted for by applying a global false discovery rate (FDR) correction to all comparisons. All genes with FDR < 0.1 were considered significant.

Enrichment analysis for Gene Ontology terms was performed using topGO package (v.2.28.0), specifying the ontology of Biological Processes (BP). Fisher’s exact test was applied to measure the significance of enrichment.

RT-qPCR experiments

RT-qPCR experiments were performed on an Applied Biosystems® 7300 Real-Time PCR System (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, USA) with the standard procedures. SYBR™ Green Master Mix (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, USA) was used for detection of amplified cDNA.

The following primers were purchased from Metabion (Planegg, Germany) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Primer list

| Target | Forward sequence | Reverse sequence |

|---|---|---|

| hu18SrRNA | 5′-CGACGACCCATTCGAACGTCT-3′ | 5′-CTCTCCGGAATCGAACCCTGA-3′ |

| GAPDH | 5′-ACGGGAAGCTTGTCATCAAT-3′ | 5′-CATCGCCCCACTTGATTTT-3′ |

Data analysis and statistics

All images and time-lapse sequences were analyzed and processed using ImageJ version 1.5. Statistical analysis (mean, SEM, unpaired student t test, and one-way ANOVA test) was performed with GraphPad Prism Version 7.0a for Mac OS X. Unless stated otherwise, all presented data are derived from three independent experiments.

Results

Actin-binding compounds influence gene transcription in endothelial cells

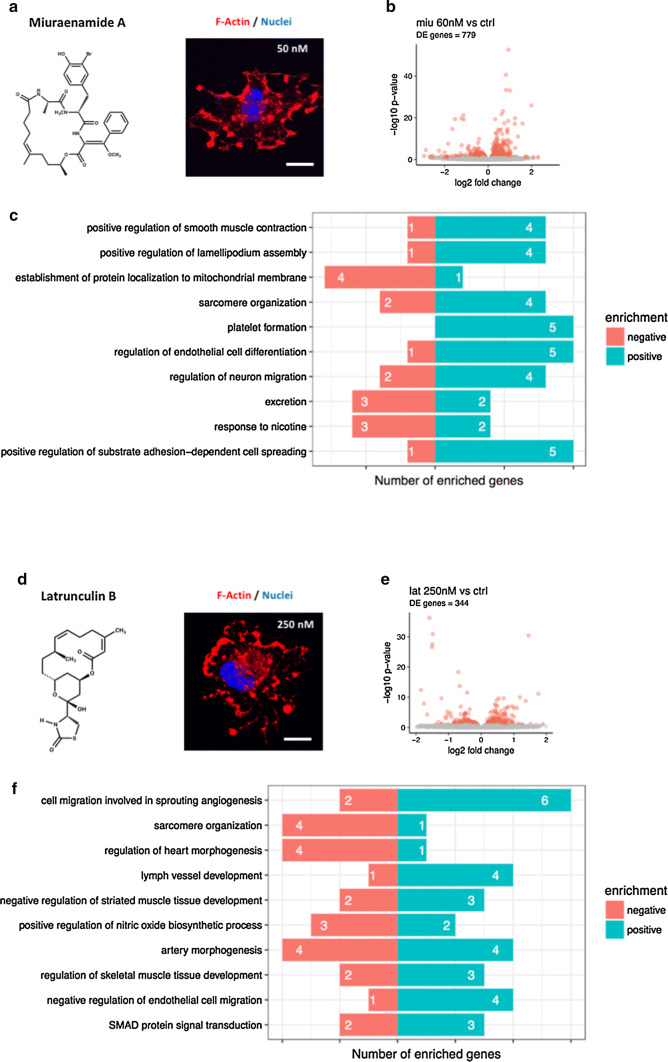

As a first step, we investigated the impact of Miuraenamide A (Fig. 1a) and Latrunculin B (Fig. 1d) on gene expression patterns in Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) using RNA-sequencing. Figure 1b summarizes the data obtained for 60 nM Miuraenamide A, which significantly regulated a total number of 779 genes in comparison with untreated control cells. As indicated by the topGO gene enrichment analysis shown in Fig. 1c, most of the regulated genes could be allocated to cytoskeleton-associated processes, such as lamellipodium formation or actin filament organization. A full list of all significantly regulated genes is available as supplementary file.

Fig. 1.

Actin-binding compounds regulate gene transcription in endothelial cells. a, d Left: molecular structures of Miuraenamide A and Latrunculin B. Right: representative F-actin stainings in HUVEC after 4 h stimulation with indicated concentrations of Miuraenamide A or Latrunculin B. b, e Volcano plots of differential gene expression in cells stimulated with 60 nM Miuraenamide A or 250 nM Latrunculin B versus control. The colored points indicate significantly differentially expressed genes (FDR < 0.1). c, f Enriched and filtered topGO categories for stimulation with Miuraenamide A and Latrunculin B versus control. The numbers in each bar indicate the number of enriched genes over the number of annotated genes in this term. Asterisks show the level of significance of Fisher’s exact test for the enrichment of the particular term. p values: *< 0.01; **< 0.001; ***< 0.0001. All bars = 20 µm

Regarding the depolymerizing compound Latrunculin B, we found a total number of 344 significantly regulated genes (Fig. 1e). The subsequent gene enrichment analysis showed that, in contrast to treatment with Miuraenamide A (Fig. 1c), most of the regulated genes were assigned to cellular processes involved in angiogenesis and the response to hypoxia (Fig. 1f). Thus, polymerizing and depolymerizing actin-binding compounds diversely regulate gene expression in primary cells. In the following, we addressed the question whether the observed transcriptional effects of both compounds are mediated by actin-dependent processes in the cytoplasm or in the nucleus.

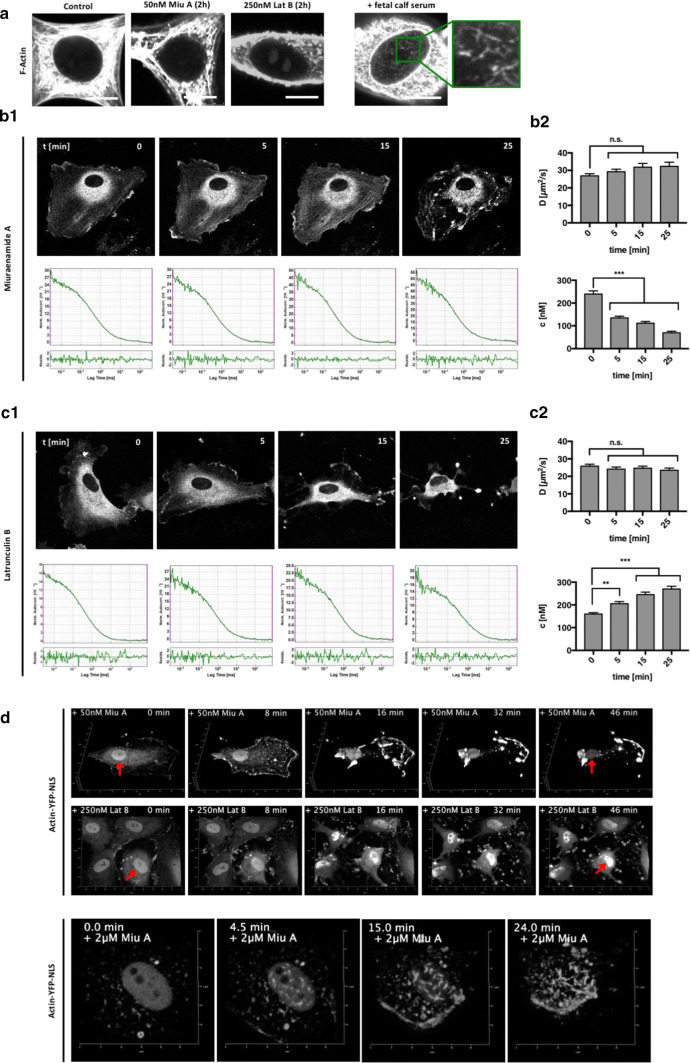

Actin polymerizers and depolymerizers inversely shift the concentration of nuclear actin

To assess whether Miuraenamide A and Latrunculin B could influence the structure of intranuclear actin, we stimulated NIH3T3 cells with either compound and performed F-actin stainings with phalloidin (Fig. 2a). As expected, Miuraenamide A induced a strong aggregation of actin in the cytoplasmatic compartment, whereas Latrunculin B led to a rapid collapse of larger stress fibers (left panels in Fig. 2a). However, although we were able to reproduce previously reported findings on serum-induced polymerization of nuclear actin filaments in NIH3T3 cells [15], we did not observe any structural alteration such as intranuclear actin aggregation or rod formation with Miuraenamide A or Latrunculin B (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

Miuraenamide A and Latrunculin B inversely shift the concentration of nuclear actin. a Phalloidin staining of nuclear actin in NIH3T3 fibroblasts after simulation with Miuraenamide A and Latrunculin B. FCS stimulation of starved cells was used as a positive control for induction of nuclear actin polymerization. Bars = 10 µm. EGFP-β-actin expressing HUVEC were stimulated with Miuraenamide A (b) or Latrunculin B (c) and the dynamics of nuclear actin were analyzed by single points FCS measurements. The representative confocal images and autocorrelation curves depicted in b1 and c1 were acquired 0, 5, 15, and 25 min after stimulation. b2, c2 Nuclear concentration and diffusion coefficients were determined in > 40 cells for each setting. Bars representing mean + SEM, statistical significance was determined by ordinary one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. d Time-lapse imaging series of actin–YFP–NLS expressing HUVEC after stimulation with Miuraenamide or Latrunculin. Red arrows indicate the position of the nuclei at the beginning and the end of the two imaging sequences

To further assess the dynamics of intranuclear actin in response to treatment with actin-binding compounds, we performed single-point fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS) measurements in EGFP–β-actin expressing cells (Fig. 2b, c). After stimulation with either 50 nM Miuraenamide A or 250 nM Latrunculin B, autocorrelation curves for nuclear EGFP–actin were acquired (45 s per measurement) over a period of 25 min (Fig. 2b1, c1). At the endpoint of our measurements, the disruptive effect of both compounds on cytoplasmatic actin was clearly evident. The data presented in Fig. 2b2 show that Miuraenamide A led to significantly decreased levels of nuclear EGFP–actin already 5 min after stimulation. In contrast, stimulation with Latrunculin B caused a time-dependent accumulation of EGFP–actin in the nuclear compartment (Fig. 2c2). Remarkably, we could not observe a change in the diffusion coefficient for either of the two compounds, which remained stable at 25–35 µm2/s, respectively. Since a considerable fraction of nuclear actin could either be incorporated into larger protein complexes or form polymers, we also applied a two-component fitting model [35, 36] and obtained similar results for both diffusion coefficients (Fig. S1).

To verify our assumption that Miuraenamide A and Latrunculin B inversely affect the concentration of nuclear actin in our cells, we overexpressed a YFP–NLS–tagged β-actin variant and performed live-cell imaging under similar conditions as in our FCS experiments. In line with our hypothesis, stimulation with Miuraenamide A or Latrunculin B had opposite effects on nuclear intensities of the YFP–NLS–β-actin construct over time (Fig. 2d). Notably, only excessive concentrations of Miuraenamide A (2 µM) were able to induce nuclear actin aggregates in β-actin–NLS expressing cells (Fig. 2d, bottom panel).

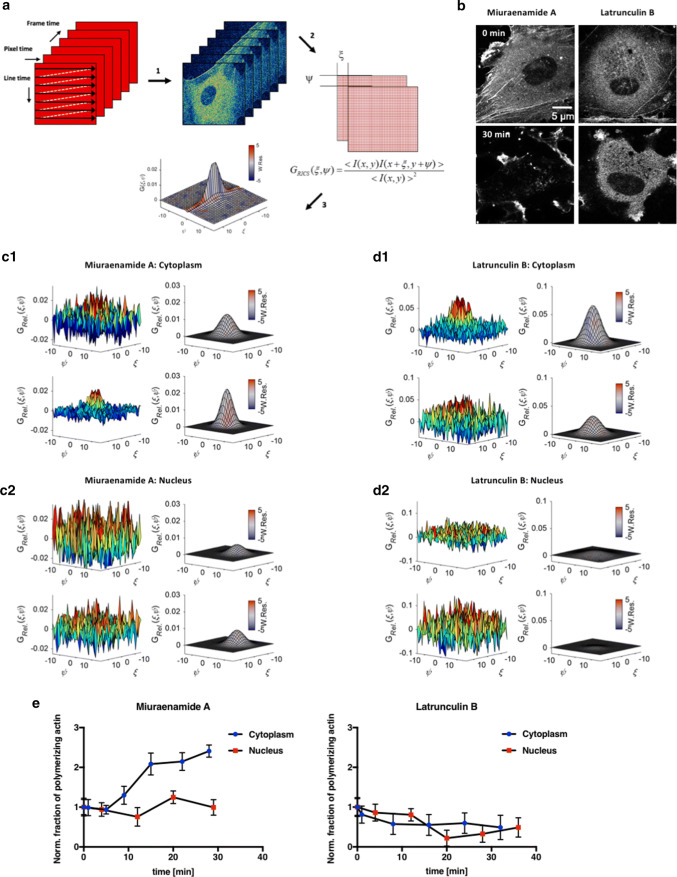

Actin-binding compounds do not affect intranuclear polymerization state at tolerable doses

Apart from the disturbing influence of vesicles and larger stress fibers, the high signal intensity of cytoplasmatic EGFP–actin severely impairs the possibility to acquire reliable FCS data in this compartment. To generate comparative data for measurements in the cytoplasm, we switched to a robust and powerful approach termed raster image correlation spectroscopy [37–39] (RICS, Fig. 3a). In RICS, a series of raster-scan images is collected as a function of time. Temporal information, from the raster-scan pattern, is encoded into the position information of the image. Using an image autocorrelation analysis, the temporal–spatial correlation in the figure can be extracted and fit to determine the concentrations and mobilities of the imaged biomolecules. The encoded spatio-temporal information in RICS is sampled over a much larger observation area and averages over local heterogeneities. Another significant advantage of RICS is the shorter exposure time of the fluorophores at one location due to laser scanning. Therefore, when performing RICS experiments, the blinking and photobleaching of the fluorescent proteins are reduced compared to FCS [40].

Fig. 3.

RICS analysis of actin aggregation in response to actin-binding compounds. a Schematic explanation of RICS data acquisition. (1) Images are acquired by a raster-scan pattern providing diffusion information of particles moving on three different time scales. (2) The image series is correlated with spatial increments upon the horizontal and vertical axes, thus providing diffusion information on three different timescales. (3) By fitting the correlation values from (2), the information on particles and diffusion is extracted. b Representative images of EGFP– and mCherry–β-actin expressing HUVEC before (0 min) and 30 min after stimulation with 100 nM Miuraenamide A or 250 nM Latrunculin B. Experimental ccRICS data obtained for the cytoplasmic (c1, d1) and nuclear (c2, d2) compartments upon stimulation with Miuraenamide A (c1, c2) and Latrunculin B (d1, d2). Left: mean SCCFs in 3D, color coded for the correlation values: SCCF before (top) and 20 min after (bottom) compound addition. Right: two-component fits of the data before (top) and 20 min after (bottom) compound addition. Fits are color coded according to the value of the goodness-of-fit weighted residuals parameter (W. Res.), where gray illustrates a good fit and red–blue indicate regions, where the residuals deviate by > 5σ. e Time course of relative cross correlation between EGFP– and mCherry–β-actin in the nuclear versus cytoplasmatic compartment in response to Miuraenamide A (left) and Latrunculin B (right)

To simultaneously address cytoplasmatic and nuclear actin aggregation in cells, we applied the novel arbitrary region RICS (ARICS) approach [41]. In principle, the desired measurement is performed in a homogenous region of the sample. However, cells are never purely homogenous with respect to structure and the distribution of biomolecules. Therefore, applying the ARICS is crucial in cases, where cellular inhomogeneity might bias the results. Actin polymerization state in live cells was assessed by co-transfecting primary endothelial cells with EGFP- and mCherry-labeled β-actin derivatives. The increase in the spatial cross correlation function amplitude (SCCF, representative images in Fig. 3b) was used to monitor the dually labeled actin. The increase of the fraction of dually labeled actin species upon stimulation with Miurenamide A clearly indicates an increase in actin oligomerization in the cytoplasm. In contrast, cross correlation and, therefore, the polymerization state of the nuclear actin pool remained unchanged over the analyzed time period. As expected, the actin-depolymerizing compound Latrunculin B leads to a decrease in the amplitude of the cross-correlation function in both compartments (Fig. 3d, e). Similarly, we monitored and analyzed both the spatial autocorrelation functions (SACF) of EGFP- and mCherry-labeled actin (Fig. S2–S4). As presented in Figs. S2–S4, we observed that the cellular stimulation with Miuraenamide A leads to an increase in a slowly diffusing species due to actin polymerization in the cytoplasmic compartment, for both EGFP- and mCherry-labeled actin. However, no significant change was observed in the nuclear compartment.

Since our findings demonstrated that actin-binding compounds have minor effects on the polymerization state of intranuclear actin, we speculated that intranuclear transcriptional machineries might not be the key mediators of the effects, as described in Fig. 1. To confirm our hypothesis, we analyzed actin-dependent transcriptional processes such RNA polymerase function, epigenetic histone modification, and chromatin structure and indeed found that most of the aforementioned processes remained unaffected by the standard doses of Miuraenamide A or Latrunculin B (Fig. S5).

Actin-binding compounds selectively regulate MRTF-A but not YAP

Having shown Miuraenamide and Latrunculin predominantly target cytoplasmatic actin, we went on to study how these compounds would affect the regulation of the two actin-dependent mechanosensitive transcription factors MRTF-A and YAP. Live-cell imaging of MRTF-A-GFP and YAP–mCherry overexpressing HUVEC revealed that stimulation with Miuraenamide A triggers nuclear translocation of MRTF-A (Fig. 4a). This is consistent with the well-established mechanism of actin-dependent MRTF–SRF regulation [42]. Apart from MRTF-A, actin polymerization has also been demonstrated to activate YAP [43]. However, we did not observe a translocation of this transcription factor upon stimulation with Miuraenamide A (Fig. 4a), which was supported by the analysis of endogenous MRTF-A and YAP localization in immunostained cells (Fig. 4b).

To test whether the nuclear translocation of MRTF-A or YAP was ultimately connected to an induction of SRF and TEAD target gene expression, we performed luciferase reporter gene assays using both CArG-box and TEAD reporter constructs (Fig. 4c). In line with our imaging data, Miuraenamide A only activated the CArG-box reporter, whereas stimulation with Latrunculin B caused only marginal changes in reporter activity. Interestingly, we found that thrombin, a PAR-receptor ligand, and physiological regulator of Rho-induced actin polymerization readily activated both MRTF-A and YAP (Fig. 4b, c), further substantiating that Miuraenamide A selectively activates MRTF–SRF but not Hippo-YAP signaling. To verify these findings on a transcriptional level, we went back to the transcriptome data presented in Fig. 1 and searched the data set for significantly up- and downregulated MRTF-A [44] and YAP/TAZ [45] target genes. We found that Miuraenamide A upregulated 90 out of 99 overlapping MRTF–SRF target genes (Fig. 4d, left panels). On the other hand, only 13 out of 31 YAP/TAZ targets were positively regulated by this compound, thus supporting our assumption that Miuraenamide A is far more efficient in activating MRTF-A compared to YAP/TAZ. Regarding the depolymerizing compound Latrunculin B, we found that the majority of MRTF–SRF and YAP/TAZ target genes was downregulated compared to untreated controls (Fig. 4d, right panels).

We also generated transcriptome data for the Rho GTPase activator thrombin and found that both MRTF–SRF (170 out of 201) and YAP/TAZ (43 out of 72) target genes were predominantly upregulated in our samples (Fig. 4e). Our transcriptome data thus underscore the finding that YAP is differently affected by actin polymerization induced by Miuraenamide A compared to the physiological PAR ligand thrombin.

Functional F-actin is required to abrogate AMOTp130-mediated YAP inhibition

The mutual crosstalk between inhibitory YAP phosphorylation (pYAP) and actin-mediated regulation of YAP is a subject of ongoing debate. Our western blot analysis of pYAP levels (Fig. 5a) showed that neither thrombin- nor Miuraenamide A-induced actin polymerization significantly decreased the amount of pYAP. This suggests that the differences in actin-dependent YAP activation described here are predominantly caused by a Lats1/2 kinase-independent mechanism.

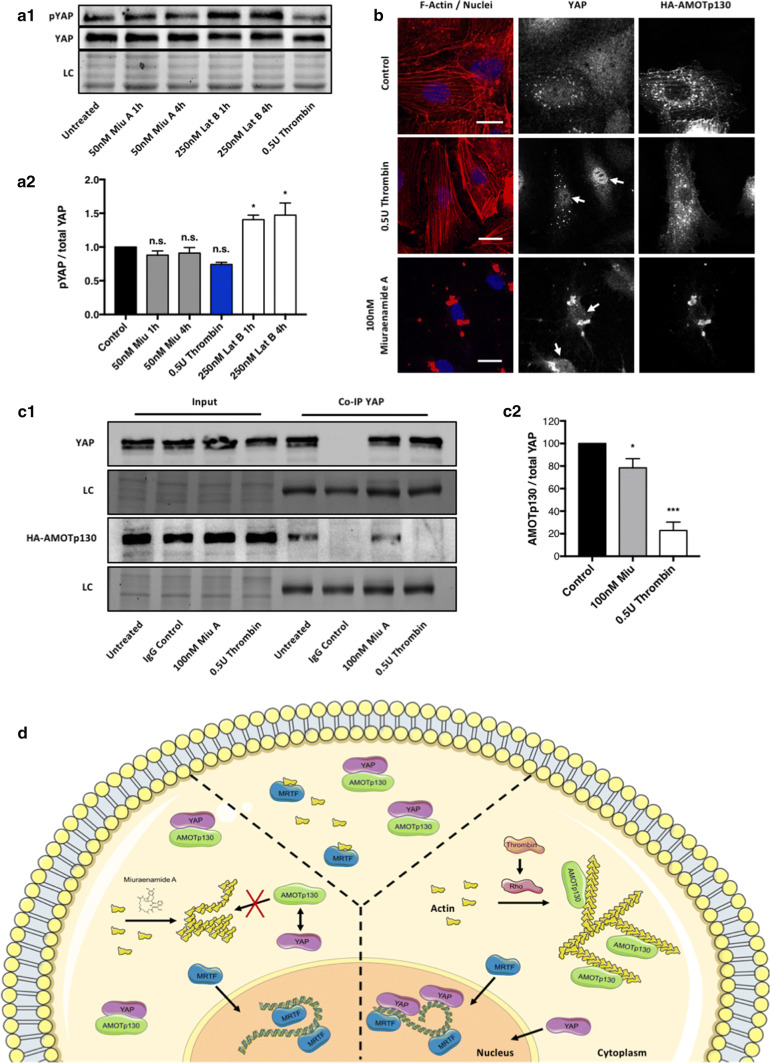

Fig. 5.

Miuraenamide A-induced actin polymerization fails to disrupt the interaction between AMOTp130 and YAP. a Representative western blot (a1) and quantification (a2) of pYAP levels normalized total YAP in cells treated with 50 nM Miuranamide A, 250 nM Latrunculin B or 0.5 U Thrombin. b HUVEC were transiently transfected with HA-AMOTp130 carrying constructs and after 2 h stimulation with either 0.5U Thrombin or 100 nM Miuraenamide co-stained for F-actin, YAP, and the overexpressed variant of AMOTp130. Bars = 30 µm. White arrows in the central YAP panel indicate the localization of cell nuclei for improved orientation. c HA-AMOTp130-expressing HUVEC were grown to confluency and stimulated, as described in b. After immunoprecipitation of endogenous YAP, bound AMOTp130 was detected via SDS-PAGE (c1, LC loading control). c2 Quantification of AMOTp130 levels normalized to total YAP, data derived from three independent experiments. Statistical significance in all experiments was determined using ordinary one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. d Supposed regulatory model underlying the differential response of MRTF-A and YAP to Miuraenamide A-induced actin aggregation

The previous studies have stated that the protein family of angiomotins (AMOTs), in particular its isoform AMOTp130, plays a key role in connecting the polymerization state of actin to YAP activity [18, 20]. We, therefore, determined whether the activation of YAP observed after stimulation with thrombin was mediated by AMOTp130. Indeed, we found that in AMOTp130 overexpressing cells, the activation of YAP in response to thrombin was abrogated when compared to wild-type cells (see white arrows in Fig. 5b). In contrast, stimulation with Miuraenamide A did not induce translocation of YAP, regardless if AMOTp130 was overexpressed or not (Fig. 5b, bottom panel). To verify our assumption, the actin aggregates formed by Miuraenamide A are unable to disrupt the interaction between AMOTp130 and YAP, we co-immunoprecipitated YAP and AMOTp130 in cell lysates obtained from the experimental setting, as described in Fig. 5a. In line with our hypothesis, binding of AMOTp130 to YAP was absent in thrombin-stimulated cells, whereas treatment with Miuraenamide A only slightly diminished this interaction compared to untreated controls cells (Fig. 5c). In sum, our data show that compound-induced actin aggregation fails to activate YAP due to the inability to release the inhibitory interaction with AMOTp130.

Discussion

Due to recent advances in the visualization of nuclear actin [46, 47], its importance for the regulation of transcriptional processes has drawn increasing attention over the past years [3, 48, 49]. However, to date, very little is known about the influence of actin-binding compounds on nuclear actin in general and on transcriptional regulation in particular. In the present study, we use the two actin-binding compounds Miuraenamide A and Latrunculin B to address the question if, and how, a pharmacological interference with the actin cytoskeleton affects transcriptional regulation, nuclear actin, and two exemplary mechanosensitive-signaling pathways.

In the experiments described here, transcription was regulated by actin-binding compounds at concentrations that affected the quantities of nuclear actin, but not its polymerization state. Our data thus implicate that, to manipulate transcriptional events, nuclear actin does not necessarily need to polymerize or depolymerize. Other examples that highlight the regulatory importance of nuclear actin levels rather than polymerization state include but are not limited to the work of Spencer et al. [50] and two studies of the Vartiainen lab [51, 52]. Moreover, our results identify actin-binding compounds as pharmacological tools for the bidirectional modulation of nuclear actin levels.

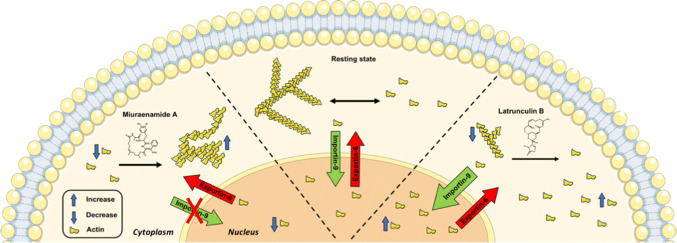

Nuclear and cytoplasmatic actin pools are in a dynamic equilibrium, which is maintained via an active transport mechanism mediated by importin 9 and exportin 6 [51, 53]. Since actin can only enter or exit the nucleus in monomeric form, we assume that an interference with the cytoplasmatic polymerization state of actin will shift the steady-state distribution of actin monomers between both compartments. As it is shown in the regulatory model presented in Fig. 6, we suggest that the change in nuclear actin concentration is a secondary result of an altered cytoplasmatic G-actin availability and thus nuclear import rates.

Fig. 6.

Proposed model for the response of nuclear versus cytoplasmatic actin to (de)polymerizing actin-binding compounds

We observed that extremely high concentrations of Miuraenamide A can induce nuclear actin aggregation in NLS–actin overexpressing cells (Fig. 2d). However, the endogenous amount of readily accessible, intranuclear actin monomers was insufficient to trigger polymerization with Miuraenamide A at tolerable concentrations. Since the cytoplasmatic concentration of actin is in the micromolar range [54], we assume that actin-binding compounds are preferentially bound in the cytoplasm. In turn, these compounds are unable to reach the nucleus in sufficient quantities within the timescale required to influence transcriptional regulation.

Taken together, our findings suggest that intranuclear actin polymerization does not significantly contribute to the mode of action of actin-binding compounds. Nevertheless, this does not exclude the possibility that intranuclear actin polymerization is relevant in other physiological contexts such as DNA damage response, mitosis, or spreading [55–57].

Apart from its distinct effect on nuclear actin levels, we found that Miuraenamide A activates the mechanosensitive transcription factor MRTF-A. This could be expected, since monomeric actin serves as the direct and main regulator of MRTF-A [17, 42]. More remarkably, subcellular localization and thus activity of the actin-dependent transcription factor YAP remained unaffected by Miuraenamide A. A regulatory connection between the actin cytoskeleton and YAP/TAZ has been extensively described [43, 58, 59]. However, the underlying mechanism is still incompletely understood. Several groups have demonstrated that the actin cytoskeleton is a major upstream regulator of the Hippo-YAP/TAZ pathway [21]. Still, it is not entirely clear whether a reduced activity of the canonical Hippo pathway kinases is mandatory or optional for actin-mediated activation of YAP [20, 60]. Our data points in the direction that actin polymerization per se do not necessarily interfere with YAP phosphorylation, regardless of whether the polymers are ultimately organized as a filamentous network or aggregate-like. A reduced interaction between AMOTp130 and YAP was sufficient to increase nuclear YAP levels independent of phosphorylation. In line with the previous work by Mana-Capelli et al., we, therefore, suggest that reduced Hippo pathway activity might act as an enhancer of actin-mediated YAP activation rather than being a prerequisite [18]. Based on our results, we developed the regulatory model, as shown in Fig. 5d. In brief, our model states that the structure of polymerized actin decides over its ability to trigger nuclear translocation of YAP via cytoskeletal remodeling. In turn, our findings support the role of F-actin as a binding scaffold for the YAP inhibitory protein AMOTp130 [19]. From a more general perspective, our results indicate that actin polymerizers, such as Miuraenamide A, are adequate tools to deplete cellular G-actin. However, due to their aggregate-like structure, the resulting polymers should not be functionally equated with physiological F-actin.

MRTF–SRF signaling accounts for many, but by far not for all of the genes regulated in our transcriptome analysis. In this context, the drastic changes in nuclear shape and chromatin structure induced by actin-binding compounds provide an interesting route for further investigation. It is well established that chromatin architecture is reorganized in response to cytoskeletal destabilization [61, 62]. However, to our knowledge, very little is known about gene sets that are specifically regulated by changes in nuclear shape or a disruption of the LINC complex.

In conclusion, our study provides an analysis of the transcriptional response to actin-binding compounds in primary cells. We demonstrate that Miuraenamide A is a potent and selective activator of the MRTF–SRF-signaling axis, since the aberrant structure of cytoplasmatic aggregates formed by this compound prevents the activation of other mechanosensitive-signaling pathways. In turn, our findings emphasize that not every actin-dependent cellular process can be mimicked with actin-binding compounds. Second, our data show that, although actin-binding compounds interfere with the quantities of nuclear actin, intranuclear polymerization state and transcriptional machineries in the nucleus remain largely unaffected. Thus, we conclude that actin-binding compounds regulate transcription via the cytoplasm rather than the nucleus.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary material 1 (TIFF 25477 kb)

Supplementary material 2 (TIFF 25477 kb)

Supplementary material 3 (TIFF 25477 kb)

Supplementary material 4 (TIFF 25477 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the labs of Prof. Robert Grosse and Prof. Bin Zhao for the sharing of plasmids and fruitful scientific discussions. We, furthermore, thank Jana Peliskova for excellent technical assistance and Dr. Lisa Karmann for providing synthetic samples of Miuraenamide A. This work was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG), SFB 1032, projects B08 and B03, and FOR1406.

References

- 1.Pollard TD, Cooper JA. Actin, a central player in cell shape and movement. Science. 2009;326(5957):1208–1212. doi: 10.1126/science.1175862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Virtanen JA, Vartiainen MK. Diverse functions for different forms of nuclear actin. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2017;46:33–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2016.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Falahzadeh K, Banaei-Esfahani A, Shahhoseini M. The potential roles of actin in the nucleus. Cell J. 2015;17(1):7–14. doi: 10.22074/cellj.2015.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Lanerolle P, Serebryannyy L. Nuclear actin and myosins: life without filaments. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13(11):1282–1288. doi: 10.1038/ncb2364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vartiainen MK. Nuclear actin dynamics—from form to function. FEBS Lett. 2008;582(14):2033–2040. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Szerlong H, Hinata K, Viswanathan R, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Cairns BR. The HSA domain binds nuclear actin-related proteins to regulate chromatin-remodeling ATPases. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15(5):469–476. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kapoor P, Shen X. Mechanisms of nuclear actin in chromatin-remodeling complexes. Trends Cell Biol. 2014;24(4):238–246. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Philimonenko VV, Zhao J, Iben S, Dingova H, Kysela K, Kahle M, Zentgraf H, Hofmann WA, de Lanerolle P, Hozak P, Grummt I. Nuclear actin and myosin I are required for RNA polymerase I transcription. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6(12):1165–1172. doi: 10.1038/ncb1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hofmann WA, Stojiljkovic L, Fuchsova B, Vargas GM, Mavrommatis E, Philimonenko V, Kysela K, Goodrich JA, Lessard JL, Hope TJ, Hozak P, de Lanerolle P. Actin is part of pre-initiation complexes and is necessary for transcription by RNA polymerase II. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6(11):1094–1101. doi: 10.1038/ncb1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu P, Wu S, Hernandez N. A role for beta-actin in RNA polymerase III transcription. Genes Dev. 2004;18(24):3010–3015. doi: 10.1101/gad.1250804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Almuzzaini B, Sarshad AA, Rahmanto AS, Hansson ML, Von Euler A, Sangfelt O, Visa N, Farrants AK, Percipalle P. In beta-actin knockouts, epigenetic reprogramming and rDNA transcription inactivation lead to growth and proliferation defects. FASEB J Off Publ Fed Am Soc Exp Biolgy. 2016;30(8):2860–2873. doi: 10.1096/fj.201600280R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Serebryannyy LA, Cruz CM, de Lanerolle P. A role for nuclear actin in HDAC 1 and 2 regulation. Sci Rep. 2016;6:28460. doi: 10.1038/srep28460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Toh KC, Ramdas NM, Shivashankar GV. Actin cytoskeleton differentially alters the dynamics of lamin A, HP1alpha and H2B core histone proteins to remodel chromatin condensation state in living cells. Integr Biol (Camb) 2015 doi: 10.1039/c5ib00027k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mammoto A, Mammoto T, Ingber DE. Mechanosensitive mechanisms in transcriptional regulation. J Cell Sci. 2012;125(Pt 13):3061–3073. doi: 10.1242/jcs.093005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baarlink C, Wang H, Grosse R. Nuclear actin network assembly by formins regulates the SRF coactivator MAL. Science. 2013;340(6134):864–867. doi: 10.1126/science.1235038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Posern G, Treisman R. Actin’ together: serum response factor, its cofactors and the link to signal transduction. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16(11):588–596. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vartiainen MK, Guettler S, Larijani B, Treisman R. Nuclear actin regulates dynamic subcellular localization and activity of the SRF cofactor MAL. Science. 2007;316(5832):1749–1752. doi: 10.1126/science.1141084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mana-Capelli S, Paramasivam M, Dutta S, McCollum D. Angiomotins link F-actin architecture to Hippo pathway signaling. Mol Biol Cell. 2014;25(10):1676–1685. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E13-11-0701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao B, Li L, Lu Q, Wang LH, Liu CY, Lei Q, Guan KL. Angiomotin is a novel Hippo pathway component that inhibits YAP oncoprotein. Genes Dev. 2011;25(1):51–63. doi: 10.1101/gad.2000111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chan SW, Lim CJ, Chong YF, Pobbati AV, Huang C, Hong W. Hippo pathway-independent restriction of TAZ and YAP by angiomotin. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(9):7018–7026. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C110.212621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gaspar P, Tapon N. Sensing the local environment: actin architecture and Hippo signalling. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2014;31:74–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wada K, Itoga K, Okano T, Yonemura S, Sasaki H. Hippo pathway regulation by cell morphology and stress fibers. Development. 2011;138(18):3907–3914. doi: 10.1242/dev.070987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Allingham JS, Klenchin VA, Rayment I. Actin-targeting natural products: structures, properties and mechanisms of action. Cell Mol Life Sci CMLS. 2006;63(18):2119–2134. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6157-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Olson EN, Nordheim A. Linking actin dynamics and gene transcription to drive cellular motile functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11(5):353–365. doi: 10.1038/nrm2890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Collin O, Na S, Chowdhury F, Hong M, Shin ME, Wang F, Wang N. Self-organized podosomes are dynamic mechanosensors. Curr Biol. 2008;18(17):1288–1294. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.07.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang CY, Leu JD, Lee YJ. The actin depolymerizing factor (ADF)/cofilin signaling pathway and DNA damage responses in cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16(2):4095–4120. doi: 10.3390/ijms16024095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ojima D, Yasui A, Tohyama K, Tokuzumi K, Toriihara E, Ito K, Iwasaki A, Tomura T, Ojika M, Suenaga K. Total synthesis of miuraenamides A and D. J Org Chem. 2016;81(20):9886–9894. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.6b02061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karmann L, Schultz K, Herrmann J, Muller R, Kazmaier U. Total syntheses and biological evaluation of miuraenamides. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2015;54(15):4502–4507. doi: 10.1002/anie.201411212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iizuka T, Fudou R, Jojima Y, Ogawa S, Yamanaka S, Inukai Y, Ojika M. Miuraenamides A and B, novel antimicrobial cyclic depsipeptides from a new slightly halophilic myxobacterium: taxonomy, production, and biological properties. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 2006;59(7):385–391. doi: 10.1038/ja.2006.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheng Z, Garvin D, Paguio A, Stecha P, Wood K, Fan F. Luciferase reporter assay system for deciphering GPCR pathways. Curr Chem Genom. 2010;4:84–91. doi: 10.2174/1875397301004010084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hendrix J, Baumgartel V, Schrimpf W, Ivanchenko S, Digman MA, Gratton E, Krausslich HG, Muller B, Lamb DC. Live-cell observation of cytosolic HIV-1 assembly onset reveals RNA-interacting Gag oligomers. J Cell Biol. 2015;210(4):629–646. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201504006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Small J, Rottner K, Hahne P, Anderson KI. Visualising the actin cytoskeleton. Microsc Res Tech. 1999;47(1):3–17. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19991001)47:1<3::AID-JEMT2>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Soumillon M, Cacchiarelli D, Semrau S, van Oudenaarden A, Mikkelsen TS. Characterization of directed differentiation by high-throughput single-cell RNA-Seq. BioRxiv. 2014 doi: 10.1101/003236. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parekh S, Ziegenhain C, Vieth B, Enard W, Hellmann I. zUMIs: A fast and flexible pipeline to process RNA sequencing data with UMIs. BioRxiv. 2017 doi: 10.1101/153940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McDonald D, Carrero G, Andrin C, de Vries G, Hendzel MJ. Nucleoplasmic beta-actin exists in a dynamic equilibrium between low-mobility polymeric species and rapidly diffusing populations. J Cell Biol. 2006;172(4):541–552. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200507101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wachsmuth M, Waldeck W, Langowski J. Anomalous diffusion of fluorescent probes inside living cell nuclei investigated by spatially-resolved fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. J Mol Biol. 2000;298(4):677–689. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brown CM, Dalal RB, Hebert B, Digman MA, Horwitz AR, Gratton E. Raster image correlation spectroscopy (RICS) for measuring fast protein dynamics and concentrations with a commercial laser scanning confocal microscope. J Microsc. 2008;229(Pt 1):78–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.2007.01871.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hendrix J, Lamb DC. Implementation and application of pulsed interleaved excitation for dual-color FCS and RICS. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1076:653–682. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-649-8_30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Digman MA, Brown CM, Sengupta P, Wiseman PW, Horwitz AR, Gratton E. Measuring fast dynamics in solutions and cells with a laser scanning microscope. Biophys J. 2005;89(2):1317–1327. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.062836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hendrix J, Schrimpf W, Holler M, Lamb DC. Pulsed interleaved excitation fluctuation imaging. Biophys J. 2013;105(4):848–861. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.05.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hendrix J, Dekens T, Schrimpf W, Lamb DC. Arbitrary-region raster image correlation spectroscopy. Biophys J. 2016;111(8):1785–1796. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miralles F, Posern G, Zaromytidou AI, Treisman R. Actin dynamics control SRF activity by regulation of its coactivator MAL. Cell. 2003;113(3):329–342. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00278-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reddy P, Deguchi M, Cheng Y, Hsueh AJ. Actin cytoskeleton regulates Hippo signaling. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e73763. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Esnault C, Stewart A, Gualdrini F, East P, Horswell S, Matthews N, Treisman R. Rho-actin signaling to the MRTF coactivators dominates the immediate transcriptional response to serum in fibroblasts. Genes Dev. 2014;28(9):943–958. doi: 10.1101/gad.239327.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zanconato F, Forcato M, Battilana G, Azzolin L, Quaranta E, Bodega B, Rosato A, Bicciato S, Cordenonsi M, Piccolo S. Genome-wide association between YAP/TAZ/TEAD and AP-1 at enhancers drives oncogenic growth. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17(9):1218–1227. doi: 10.1038/ncb3216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Belin BJ, Cimini BA, Blackburn EH, Mullins RD. Visualization of actin filaments and monomers in somatic cell nuclei. Mol Biol Cell. 2013;24(7):982–994. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-09-0685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Melak M, Plessner M, Grosse R. Actin visualization at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2017 doi: 10.1242/jcs.189068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miyamoto K, Gurdon JB. Transcriptional regulation and nuclear reprogramming: roles of nuclear actin and actin-binding proteins. Cell Mol Life Sci CMLS. 2013;70(18):3289–3302. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1235-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rajakyla EK, Vartiainen MK. Rho, nuclear actin, and actin-binding proteins in the regulation of transcription and gene expression. Small GTPases. 2014;5:e27539. doi: 10.4161/sgtp.27539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Spencer VA, Costes S, Inman JL, Xu R, Chen J, Hendzel MJ, Bissell MJ. Depletion of nuclear actin is a key mediator of quiescence in epithelial cells. J Cell Sci. 2011;124(Pt 1):123–132. doi: 10.1242/jcs.073197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dopie J, Skarp KP, Rajakyla EK, Tanhuanpaa K, Vartiainen MK. Active maintenance of nuclear actin by importin 9 supports transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(9):E544–E552. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118880109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sharili AS, Kenny FN, Vartiainen MK, Connelly JT. Nuclear actin modulates cell motility via transcriptional regulation of adhesive and cytoskeletal genes. Sci Rep. 2016;6:33893. doi: 10.1038/srep33893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stuven T, Hartmann E, Gorlich D. Exportin 6: a novel nuclear export receptor that is specific for profilin.actin complexes. EMBO J. 2003;22(21):5928–5940. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pollard TD. Actin and actin-binding proteins. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2016 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a018226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Baarlink C, Plessner M, Sherrard A, Morita K, Misu S, Virant D, Kleinschnitz EM, Harniman R, Alibhai D, Baumeister S, Miyamoto K, Endesfelder U, Kaidi A, Grosse R. A transient pool of nuclear F-actin at mitotic exit controls chromatin organization. Nat Cell Biol. 2017 doi: 10.1038/ncb3641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Plessner M, Grosse R. Extracellular signaling cues for nuclear actin polymerization. Eur J Cell Biol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2015.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Belin BJ, Lee T, Mullins RD. DNA damage induces nuclear actin filament assembly by formin-2 and spire-(1/2) that promotes efficient DNA repair. Elife. 2015 doi: 10.7554/eLife.07735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Matsui Y, Lai ZC. Mutual regulation between Hippo signaling and actin cytoskeleton. Protein Cell. 2013;4(12):904–910. doi: 10.1007/s13238-013-3084-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yu FX, Guan KL. The Hippo pathway: regulators and regulations. Genes Dev. 2013;27(4):355–371. doi: 10.1101/gad.210773.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dai X, She P, Chi F, Feng Y, Liu H, Jin D, Zhao Y, Guo X, Jiang D, Guan KL, Zhong TP, Zhao B. Phosphorylation of angiomotin by Lats1/2 kinases inhibits F-actin binding, cell migration, and angiogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(47):34041–34051. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.518019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Isermann P, Lammerding J. Nuclear mechanics and mechanotransduction in health and disease. Curr Biol. 2013;23(24):R1113–R1121. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dahl KN, Ribeiro AJ, Lammerding J. Nuclear shape, mechanics, and mechanotransduction. Circ Res. 2008;102(11):1307–1318. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.173989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material 1 (TIFF 25477 kb)

Supplementary material 2 (TIFF 25477 kb)

Supplementary material 3 (TIFF 25477 kb)

Supplementary material 4 (TIFF 25477 kb)