Abstract

The methylation of proteins is integral to the execution of many important biological functions, including cell signalling and transcriptional regulation. Protein methyltransferases (PMTs) are a large class of enzymes that carry out the addition of methyl marks to a broad range of substrates. PMTs are critical for normal cellular physiology and their dysregulation is frequently observed in human disease. As such, PMTs have emerged as promising therapeutic targets with several inhibitors now in clinical trials for oncology indications. The discovery of chemical inhibitors and antagonists of protein methylation signalling has also profoundly impacted our general understanding of PMT biology and pharmacology. In this review, we present general principles for drugging protein methyltransferases or their downstream effectors containing methyl-binding modules, as well as best-in-class examples of the compounds discovered and their impact both at the bench and in the clinic.

Keywords: Chemical probe, Protein methyltransferase, Methyl-binder protein, Epigenetics, Chromatin, Chemical biology, Drug discovery, Oncology

Introduction

The post-translational modification (PTM) of proteins is a fundamental biological phenomenon, which contributes to the regulatory control of protein function and cell signalling. Following synthesis, proteins can be enzymatically modified by the addition of a wide range of chemical moieties. Key among these modifications is protein methylation. First described in 1959 in bacteria and shortly thereafter observed in mammalian histones [1, 2], protein methylation is now recognized as a pervasive, reversible, and highly versatile means of protein regulation (for a compelling historical narrative on the breakthroughs and challenges faced in the field of protein methylation, we recommend a recent review by Murn and Shi [3]).

In eukaryotes, the majority of protein methylation is carried out by two broadly defined enzyme families; lysine methyltransferases (KMTs) and protein arginine methyltransferases (PRMTs), which modify the ε amino group of lysine and guanidinium group of arginine, respectively (Fig. 1). Methylation of histidine, glutamate, glutamine, asparagine, cysteine, N-terminal, and C-terminal residues has also been observed [4]. However, our understanding of non-lysine/arginine methylation is limited. In fact, the first mammalian histidine methyltransferase was only recently described [5, 6]. Regardless of the substrate, all protein methyltransferases (PMTs) utilise S-5′-adenosyl-l-methionine (SAM) cofactor/cosubstrate as a methyl donor, catalyzing the transfer of a methyl group to a substrate acceptor. Deposition of the methyl mark by so-called ‘writer’ enzymes can influence a protein’s structure, localisation, or interactions with methyl-binding ‘reader’ domains. The recruitment of methyl-readers often plays a central role in coupling the modification with downstream effector proteins. Like many PTMs, the methyl mark can be erased by demethylase enzymes, permitting tunable and dynamic regulation of methyl signalling [7].

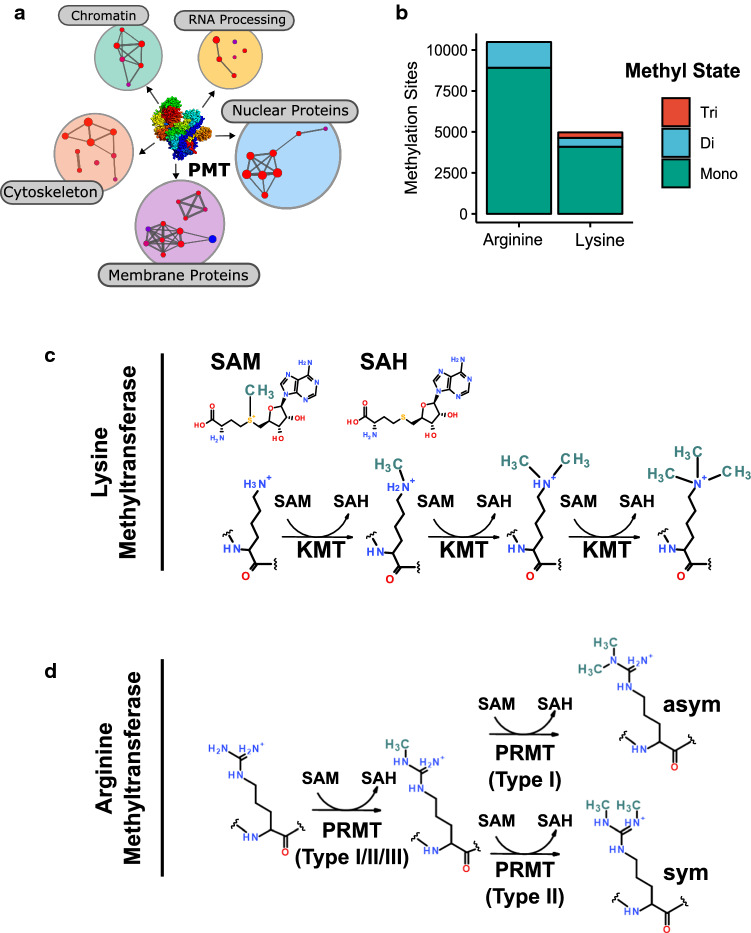

Fig. 1.

Protein methylation in humans. a Protein methyltransferase substrates are found throughout the cell. Shown is a network view of associated cellular component gene ontologies of methyltransferase substrates identified in the PhosphoSite database [8]. b Number of arginine and lysine methylation sites in the phosphosite database by methyl state. c, d Schematic illustrations of lysine and arginine methylation. Lysine can be mono-, di-, or trimethylated by KMT enzymes at the ε-amino group. Type I/II/III PRMTs can monomethylate arginine on guanidine group. Further modification by Type I PRMTs results in asymmetric dimethylation, while Type II proceeds to symmetrical dimethylation of arginine residues

Protein methyltransferases operate throughout the cell, targeting a functionally diverse spectrum of proteins [8] (Fig. 1a). In humans, over 4000 Lys and Arg methylation sites have been observed (Fig. 1b). As the identification of many of these sites is the result of large-scale proteomics efforts, the biological consequence of most is unknown. The most significant strides in our understanding of how protein methylation influences molecular events has come from studying the epigenetic regulation of the genome. Histone proteins, which package eukaryotic genomes as chromatin, are a major and well-defined substrate of PMTs [9]. The location, extent, and interaction of these marks are critical for chromatin-templated processes, including establishing the transcriptional programs that define a cell’s identity. There is an association between the dysregulation of chromatin-modifying enzymes and the development and progression of many human diseases, including cancer [10–12].

Consequently, there is significant interest in the pharmacological modulation of proteins that write, read, and erase methyl marks [13, 14]. Indeed, several histone methyltransferase inhibitors have already reached the clinic [15] (Table 1), demonstrating the tractability of PMTs as a target class. In addition to histone-centric roles, PMTs are also critical in the regulation of non-histone proteins, with important implications for human health and the treatment of disease beyond oncology [16, 17].

Table 1.

Examples of potent, selective, and cell-active inhibitors of protein methyltransferase activity

| Target | Compounds | Binding Mode | IC50 or Kd (in vitro) | Cellular Activity (Biomarker) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EZH2/1 |

UNC1999 EPZ-6438 |

SAM Competitive | < 100 nM |

< 300 nM H3K27me3 |

[83, 160] |

| EHMT1/EHMT2 |

UNC0642 A366 |

Peptide Competitive | < 10 nM |

< 300 nM H3K9me2 |

[56, 57] |

| SUV420H1/2 | A-196 | Peptide Competitive | 21 nM |

< 400 nM H4K20me2/3 |

[161] |

| SMYD2 |

BAY-598 EPZ033294 |

Peptide Competitive | < 100 nM |

< 100 nM P53K370me |

[72, 73] |

| SMYD3 | EPZ031686 | Peptide Competitive | < 10 nM |

< 100 nM MEKK2K260me3 |

[162] |

| SETD7 | (R)-PFI-2 | Peptide Competitive | < 10 nM |

~ 1 µM YAP translocation |

[163] |

| pan-type 1 PRMT | MS023 | Peptide Competitive | < 100 nM |

< 100 nM H4R3me2a |

[98] |

| PRMT3 | SGC707 | Allosteric Inhibitor | 31 nM |

<100 nM H4R3me2a |

[74] |

| CARM1 (PRMT4) |

TP-064 EZM2302 (GSK3359088) |

Peptide Competitive Non-competitive |

<10 nM 6 nM |

< 400 nM MED12me2a < 100 nM PABP1me1a, SmBme0 |

[101, 106] |

| PRMT5 |

EPZ015666 LLY-284 |

Peptide Competitive | < 50 nM |

< 100 nM SmD3,SmBB-Rme2 s |

[116, 128] |

| PRMT6 | EPZ020411 | Peptide Competitive | 10 nM |

< 1 μM H3R2me2a |

[99] |

| PRMT7 | SGC3027 | SAM Competitive | < 2.5 nM |

~ 1 μM HSP70me1 |

a |

| PRDM9 | MRK-740 | Peptide Competitive | 85 nM |

~ 1 μM H3K4me3 |

b |

| DOT1L | SGC0946 | SAM Competitive | < 1 nM |

~ 10 nM H3K79me3 |

[78] |

| EED |

A-395 EED226 |

Allosteric Antagonist |

< 50 nM |

< 100 nM H3K27me3 |

[42, 43] |

| WDR5 | OICR-9429 | Disruption of MLL complex | 64 nM |

223 nM Disruption of Wdr5-MLL |

[164] |

Since the first selective PMT inhibitor was identified in 2007 [18], there has been phenomenal progress in the discovery and refinement of small-molecule disruptors of methyl-lysine/arginine signalling (Fig. 2; Table 2). These tools, with complementary molecular technologies, have enabled numerous breakthroughs in our understanding of biology and medicinal target discovery. In particular, a coordinated effort by the chemical biology community to develop sets of well-defined, selective, and cell-active chemical probes has provided researchers across disciplines with valuable tools to “probe” mechanistic questions in biology (for a broader discussion on what constitutes a chemical probe, we suggest commentaries by Blagg and Workman [19], Arrowsmith et al. [20], and Frye [21]). When used to study biology, chemical probes offer several distinct advantages over genetic knockouts or RNAi-mediated knockdowns, including (1) mechanistic insight from selective targeting of a specific activity/domain of a protein, (2) temporal resolution of function, (3) amenability to high-throughput screening techniques, and (4) direct translational potential of findings. Underscoring the utility of chemical probes as such, significant advances in our understanding of the pharmacology and biology of the acetyl-lysine binding bromodomains has resulted from the discovery of the probes JQ1 [22], I-BET [23], and the many that followed [24–30]. Panels of well-validated probes to protein methyltransferases have also been described with demonstrated utility in interrogating complex biological systems [31].

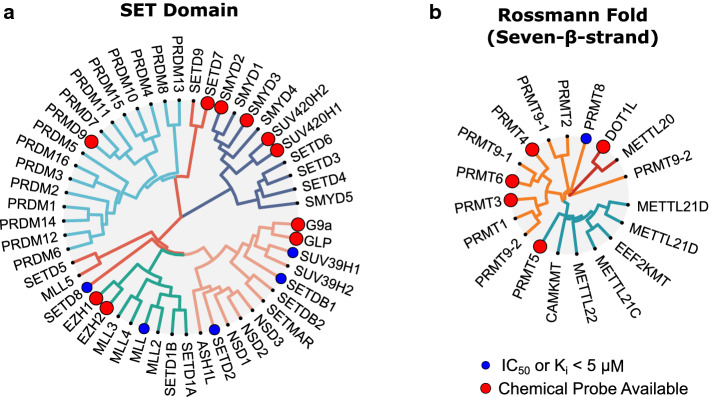

Fig. 2.

Inhibitors of Protein Methyltransferase Families. a, b Phylogeny of protein methyltransferase domains from SET-domain and seven-β-strand PMT families. Indicated with a blue circle, are proteins with inhibitors of at least 5 µM potency (IC50 or Ki) described in the BindingDB database [157] Those with a chemical probe available are indicated with a red circle (https://www.thesgc.org/chemical-probes)

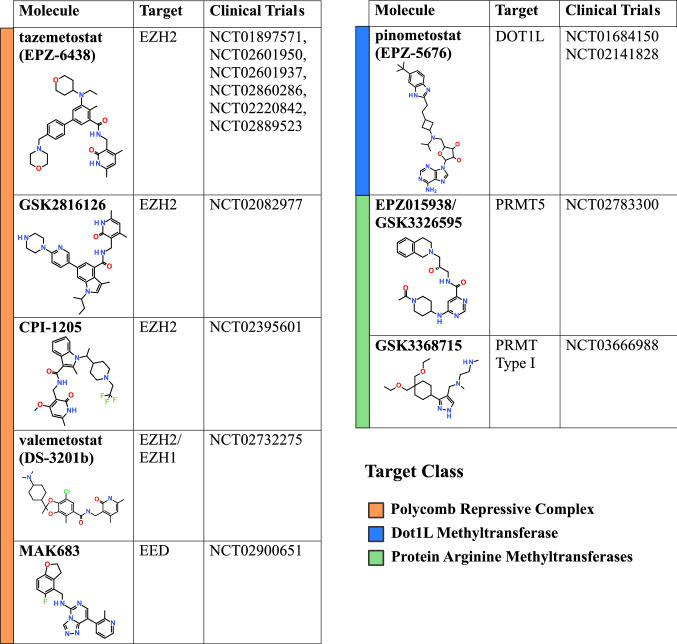

Table 2.

Protein methyltransferase inhibitors in clinical trials

In this review, we will first present a general description of the chemical modalities of PMT inhibition. It is followed by examples of cell-active catalytic-site inhibitors of both KMTs and PRMTs, with particular attention paid to the novel biology discovered and movement towards clinical utility. Finally, we will touch upon more recent advances in the development of methyl-lysine reader antagonists, which present opportunities to selectively intervene in the downstream signalling of the methyl mark or as alternative sites to target PMTs themselves.

Targeting protein methyltransferase activity

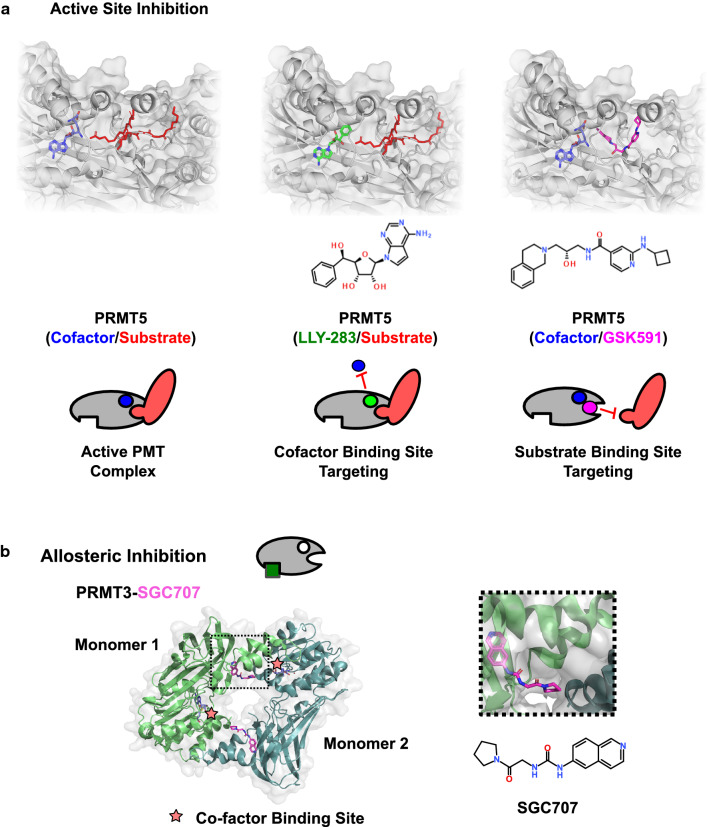

All PMTs share a common catalytic mechanism. The SAM donor and peptide methyl-acceptor bind to distinct, but connected, surfaces within the active site to form a functional ternary complex. Followed by the assembly of the complex, direct transfer of the methyl group from SAM to substrate proceeds via a classical SN2 reaction. Chemical inhibition has been demonstrated by targeting either cofactor or substrate-binding sites, as well as by allosteric means (Fig. 3). Each of these modalities presents unique challenges and opportunities to disrupt the methyltransferase activity of these enzymes.

Fig. 3.

Mechanisms of enzymatic PMT inhibition. a Substrate peptide and SAM cofactor bind at distinct sites in the active site, as shown in a crystal structure of PRMT5 with H4 peptide substrate and SAM analogue cofactor (PDB: 4GQB). Active site inhibition can be achieved by targeting either cofactor or substrate-binding site. Examples shown include LLY-283 cofactor site binding (PDB: 6CKC) and GSK591/EPZ015866 binding to the substrate peptide channel (PDB: 5C9Z). b Structure of the allosteric inhibitor SGC707 bound to a biological assembly of PRMT3 (PDB: 4RYL). SGC707 binds at the interface between dimers to block formation of the active homodimer

The earliest efforts to inhibit protein methyltransferases mainly exploited non-selective analogues of SAM in the discovery of PMT inhibitors [32], including the antibiotic sinefungin [33]. Chaetocin, another naturally occurring SAM analogue, was initially reported as the first selective inhibitor of SU(VAR)3–9 and G9a [34]. However, it is now clear that these effects are likely due to the off-target activity of a reactive thiol group [35]. Broad-spectrum inhibition of methylation has also been demonstrated through the blockade of AdoHcy hydrolase activity, resulting in the accumulation of SAH and feedback on cellular production of SAM, including the compounds adenosine dialdehyde (AdOx) [36], MDL 28842 [37], and DZNep [38]. Given the lack of specificity, these compounds should be avoided for biological studies of methyltransferase function. Additional challenges in targeting the SAM-binding sites include overcoming the high concentrations of intracellular SAM (~ 20–40 uM), which will often result in a drastic shift in potency when moving from in vitro to cell-based assays [15] In addition, the hydrophobic nature of the SAM-binding pocket, which can represent challenges in generating molecules sufficiently polar to enable cell penetrance [39]. Despite these challenges, the SAM-binding site itself is poorly conserved and inhibitor selectivity, even amongst close analogues, is possible [39]. Indeed, potent, selective, cell-permeable SAM-competitive inhibitors have been described, with several having advanced to the clinic (Tables 1 and 2).

Selective inhibition of the substrate channel is generally considered to be a more chemically tractable approach, as the pocket tends to be deep, enclosed, structurally diverse, and accommodating of small molecules with desirable physiochemical properties [40]. For these reasons, there are a higher number of selective substrate-site small molecules described in the literature. While structural diversity within the substrate groove can be exploited in the design of highly selective molecules, chemical selectivity for closely related enzymes with demonstrated activity towards the same target lysine/arginine can still be achieved [40]. Targeting the peptide-binding site is not without its challenges. Structural plasticity is a common feature of PMT substrate-binding sites, whereby a ligand-dependent conformation may be adopted [41]. This has implications on the shape and druggability of the substrate-binding site in ligand-bound versus unbound states. Computationally, this is difficult to model and has made ab initio virtual screening approaches particularly challenging [40].

The enzymatic activity of PMTs can be allosterically modulated through distal binding sites. Molecules targeting PRMT3 and the PRC2 complex are the best examples of allosteric inhibition described to date [42–45]. In both instances, allosteric compounds act by disrupting critical protein interactions required for methyltransferase activity (Fig. 3). The conformational plasticity of substrate-binding sites may also enable other forms of allosteric regulation through structural perturbations resulting from binding allosteric sites on the methyltransferase enzyme itself. However, this remains to be determined. The next section of the review will discuss specific examples of lysine and arginine methyltransferases with attention paid to their mechanisms of action.

Drugging lysine methyltransferases

The ɛ amine of lysine can be mono-, di-, or trimethylated, progressively increasing side-chain steric bulk and hydrophobicity without altering charge. In humans, greater than 50 KMTs catalyze lysine methylation to various degrees and across a broad range of substrates [46] (Fig. 2). Most lysine methyltransferases rely on a conserved ~ 130 amino acid long SET [Su(var.)3–9(the suppressor of position-effect variegation 3–9), En(zeste) (an enhancer of the eye color mutant zeste), and Trithorax (the homeotic gene regulator)] domain to catalyze transfer of the methyl moiety. The flanking I-SET and post-SET domains further contribute to the substrate and, in some cases, SAM-binding sites [41]. A smaller subset of KMTs, along with the PRMTs, belong to the seven-beta-strand methyltransferase family and contain a Rossmann-like fold [47]. The seven-β-strand family includes the only non-SET-domain-containing lysine histone methyltransferase, DOT1L. Here, we describe several examples of the biology gleaned from PMT tool compounds and translational advances. For more in-depth coverage of the many PMT inhibitors discovered to date, we suggest recent reviews by Jian Jin et al. [48–50].

KMT active site inhibitors

In 2007, the first selective small-molecule inhibitor of a KMT, BIX-01294, was reported [18]. BIX-01294 displayed selective cofactor-independent activity against G9a (IC50 = 1.7 µM), the primary H3K9me1/2 histone methyltransferase, and to a lesser extent the obligatory G9a heterodimerization partner, GLP (IC50 = 38 µM). Subsequent crystallographic studies of BIX-01294 revealed binding to the substrate-binding site [51]. Importantly, BIX-01294 decreased the euchromatin-associated H3K9 dimethyl mark in cells, making it a valuable tool to study repressive chromatin environments. Since its discovery, this inhibitor has been used to probe G9a involvement in cellular reprogramming [52, 53] and viral latency of HIV-1 [54]. Unfortunately, the poor separation between cytotoxic and functional effects has limited broader utility and adoption of this compound. This issue was primarily overcome with the discovery of UNC0638, a potent substrate-competitive inhibitor of G9a (IC50 < 15 nM) and GLP (IC50 = 19 nM), which has increased on-target functional potency relative to off-target cytotoxicity [55]. UNC0638 reduced the abundance of H3K9me2 and reactivated G9a-silenced genes and a retroviral reporter in mouse ES cells, demonstrating its usefulness to study the biology of G9a/GLP [55]. Notably, UNC0638 has been further optimized to UNC0642, a molecule with improved pharmacokinetics suitable for in vivo animal experiments [56]. Another potent G9a inhibitor with an unrelated scaffold, A-366 [57], was also shown to induce differentiation in leukemia cell lines and inhibit the growth of a flank xenograft leukemia model [58]. However, A-366 was recently shown to antagonize recognition of H3K4me3 by the Tudor domain of Spindin1, a methyl-lysine reader (IC50 = 182.6 ± 9.1 nM) [59]. While numerous studies link G9a to disease [60], no G9a inhibitors have yet reached the clinic.

The five-member SMYD family of lysine methyltransferases methylate both histone and non-histone proteins [61]. Reports of overexpression and dependency of SMYD2 and SMYD3 in several cancer types has generated significant interest in the identification of chemical inhibitors [62–65]. To date, various selective SMYD2 inhibitors have been reported, highlighting the possibility to target the same site with multiple chemotypes [66]. The first selective inhibitor of SYMD2, the benzoxazinone AZ505 (IC50 = 120 nM), laid significant groundwork in the development of SMYD2 substrate-site inhibitors by reporting crystal structures of both substrate and AZ505 bound complexes [67]. While AZ505 has been used to probe the involvement of SMYD2 in triple negative breast cancer [68], more advanced probes are available and recommended for biological work. Investigation of the structure–activity relationship (SAR) of AZ505, led to A-893 (IC50 = 2.8 nM), a significantly more potent molecule with apparent reduced off-target effects [69]. A second chemotype, LLY-507 (IC50 < 15 nM), was shown to inhibit monomethylation of p53-K370 at sub-μM concentrations [70], a modification believed to attenuate p53′s tumour suppressor activity [71]. LLY-507 also displayed anti-proliferative effects on esophageal, liver, and breast cancer cell lines in a dose-dependent manner [70]. In stark contrast, BAY-598 (IC50 = 27 nM), an equipotent SMYD2 inhibitor had little effect on the same cell lines that displayed sensitivity to LLY-507 [72]. Resolving this discrepancy, a recent and comprehensive study evaluating SMDY2 dependency in cancer, including two new inhibitors EPZ033294 and EPZ032597 with demonstrated cellular inhibition of relevant methyl marks, found neither CRISPR-mediated disruption nor treatment with novel tool compounds reproduced previously reported cancer cell line vulnerabilities to SMDY2 inhibition or RNAi knockdown [73]. Similar to SMDY2, the SMYD3 inhibitors, BCI-121 [74], GSK2807 [75], EPZ031686 [73], and EPZ028862 [73], also seem to have limited effects on cancer cell line proliferation. As it happens, the genetic validation data for SMYD2 and SMYD3 relied on shRNAs that later proved to have off-target effects [73]. The saga of SMYD inhibitors provides essential lessons in validating phenotypes ideally by genetic knockouts, extensive screening for off-target effects, and the value of having orthogonal probes with diverse chemotypes when pursuing medicinal target validation.

DOT1L methyltransferase performs mono, di and trimethylation of H3K79 mark, which is associated with transcriptional regulation, development and DNA repair [76]. The genetic link showing that DOT1L is essential in MLL-rearranged leukemias has spurred clinical interest in selective DOT1L inhibitors [77]. The first inhibitor based on the cofactor SAM, EPZ004777, was reported as a highly potent and selective compound and was followed by closely related chemical probe compound with improved cell potency, SGC0946 [78, 79]. This DOT1L inhibitor series has a remarkably long residence time (> 24 h) and high affinity to the enzyme, which is explained by binding to the SAM pocket leading to a conformational change and generation of a new pocket, thus increasing the affinity dramatically [78, 79]. These conformational dynamics illustrates the challenges in modelling compound–enzyme interactions but also offers opportunities for other possible induced-fit type compounds in the PMT space. Despite the chemical scaffold closeness to SAM, DOT1L inhibitors were highly cell permeable and active on leukemia cell lines carrying MLL rearrangements; however, in vivo stability liabilities warranted further optimisation of pharmacokinetic properties and yielded EPZ-5676, a compound currently currently in phase I clinical trials for hematologic malignancies [79] (Table 2; Clinical Trial #NCT01684150; NCT02141828).

EZH2 and EZH1 are the catalytic subunits of the PRC2 H3K27 methyltransferase complex, which also contains the essential core regulatory subunits SUZ12 and EED. The complex has many well-described roles in development and carcinogenesis [80]. Accumulating reports of high levels of EZH2 and H3K27 methylation in cancer, led to keen interest and numerous high-throughput biochemical screening campaigns that since 2012 have provided several tools and clinical compounds (Tables 1, 2). The first EZH2 selective inhibitor, EPZ005687, was followed shortly by GSK126, the chemical probe UNC1999, which has activity against both EZH2 and EZH1 [81–83], and finally by the clinical compound EPZ-6438 [84]. All of these molecules contain the 2-pyridone moiety crucial for enzyme inhibition. This moiety partially occupies the cofactor SAM-binding site accounting for the cofactor-competitive mechanism. These compounds primarily differ by the linking of the 2-pyridone warhead to several groups such as indazole (EPZ005687 and UNC1999), indole (GSK126) or simple aromatic rings as in the clinical compound EPZ-6438. Modulation of high H3K27me3 levels in many solid tumours is still being explored in cancer therapy; however, this regulation is likely more complicated, and modulation of H3K27 methylation itself may not result in clear-cut anti-cancer effects. Where EZH2 inhibition proved to be particularly beneficial was in lymphomas with activating EZH2 mutations that result in abnormally high levels of H3K27me3 [85]. Several clinical phase 1 and 2 trials are ongoing in lymphomas [15] (Table 2). Another area where the genetic experiments, as well as chemical modulation, discovered an unexpected avenue for EZH2 inhibition is in cancers with mutated SWI/SNF complexes [84, 86]. In particular, EPZ-6438 has shown remarkable activity in rhabdoid tumours with SWI/SNF mutations, and clinical trials are ongoing for synovial sarcoma (Table 2; Clinical Trial: NCT02601950).

KMT allosteric inhibitors

There are no allosteric inhibitors that bind lysine methyltransferase proteins directly. However, several KMTs are only active in the context of sizeable multi-subunit protein complexes, and small-molecule antagonism of regulatory subunits has been demonstrated as a viable strategy to inhibit methyltransferase activity. One such example is the targeting of WD-40 repeats of EED, a regulatory component of PRC2. WD-40 repeats are one of the most abundant scaffolding domains in the proteome and play a significant role in facilitating the connectivity of cellular networks [87]. Structurally, WD-40 repeats are defined by a β-propeller with a peptide-binding pocket at its centre. Pharmacologically, these domains often have druggable binding pockets on surfaces that mediate protein–protein interactions [88]. In PRC2, the EED subunit binds to H3K27me3 to allosterically activate the complex and propagate the repressive mark [89]. Two unique small-molecule allosteric antagonists of EED H3K27me3 binding, A-395 and EED226, were recently described in back-to-back studies to have activity against PRC2-dependent tumours [42, 43]. These allosteric inhibitors have the potential to overcome developed resistance to SAM-competitive EZH2 compounds, a potential limitation of previous clinical molecules observed in several cancer cell lines [90, 91]. A clinical compound that utilises this mechanism, MAK683, is now in trials for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (Table 2; Clinical Trial #NCT02900651).

Drugging arginine methyltransferases

Arginine methylation is a widespread PTM mediated by a family of PRMT enzymes with diverse substrate clientele (Fig. 1). Structurally, PRMTs belong to the seven-β-strand family of methyltransferases and are characterized by a β-barrel and a Rossmann fold, which contribute to binding of the substrate and cofactor, respectively [92, 93]. Type I PRMTs asymmetrically dimethylate arginine and have head to tail homodimer structures, while type III arginine monomethylating PRMT7 has two domains adopting a similar arrangement with the C-terminal pseudo-catalytic domain acting as a counterpart of the dimer [94] (Fig. 1d). In addition to the β barrel and a Rossmann fold, the type II symmetric dimethyl-arginine-catalyzing PRMT5 has an N-terminal TIM barrel that binds WD-repeat protein MEP50 to act as a substrate recruitment platform [95]. Several PRMT inhibitors with variable degrees of in vitro activity, selectivity, and cellular potency have been identified and described in extensive reviews [48, 96]. In this review, we will focus on the most selective compounds with cellular target engagement and activity characterisation (Table 2).

PRMT allosteric inhibitors

In 2012, screening of a 16,000 compound library led to the identification of a PRMT3 inhibitor (IC50 = 2.5 μM) [97]. The crystal structure revealed compound binding at the dimerisation arm of a PRMT3 monomer (Fig. 3b). This compound displayed non-competitive inhibition for both SAM and substrate, indicating an allosteric mechanism of action [97]. In further support of an allosteric binding mode, mutation of the allosteric site abrogated inhibitory activity of the compound without disrupting PRMT3 methyltransferase activity [97]. Further lead optimization yielded a very potent (IC50 = 31 nM) and selective inhibitor, SGC707 [45]. The cell activity of this compound was demonstrated by monitoring target engagement and PRMT3 protein stabilization in In Cell Hunter assays as well as the reduction of PRMT3-driven H4R3me2a levels [45].

Type I PRMT inhibitors

Small molecules that target the peptide-binding site of PRMTs display selectivity profiles ranging from very selective (TP-064) to pan-Type I inhibitors (MS023). The challenge of achieving selectivity may stem from the fact that several inhibitors exploit the arginine-binding channel, where a basic alkyl-diamino or alanine–amide tail interacts with conserved glutamate, methionine, and histidine residues [48]. This includes the pan-Type I inhibitor MS023, which is highly potent and active in vitro against PRMT1, 3, 4, 6, and 8 (IC50 = 4–120 nM). MS023 also shows activity in cells towards both endogenous PRMT1 driven asymmetric methylation of H4R3 (IC50 = 10 nM) and overexpressed PRMT6-driven methylation of H3R2 (IC50 = 56 nM) [98]. However, for the inhibition of bulk asymmetric methylation, much higher concentrations of MS023 are required (1 μM), indicating differential sensitivity between various cellular substrates [98]. Improvements in inhibitor selectivity within Type I PRMTs were demonstrated with EPZ020411 and MS049 [99, 100]. EPZ020411 exploits additional moieties in the substrate-binding site, rendering it more selective towards PRMT6, while MS049, a PRMT4 and PRMT6 dual inhibitor that also occupies the arginine binding channel has diminished activity towards PRMT1. The PRMT4 inhibitor TP-064 achieves selectivity by engaging additional hydrophobic π-stacking interactions and hydrogen bond interactions with phenylalanine and asparagine side chains [101]. Unfortunately, a lack of PRMT1 structures with compounds has hindered our understanding of selectivity for this chemical series and development of more discriminatory molecules. While exquisite selectivity is a highly desirable feature of a chemical probe, this not necessarily the case for drug development, where the phenotypic effect is the most important outcome [20]. Thus, the pan-selectivity of MS023 and broad-spectrum Type I inhibitors has not excluded intense exploration as a therapeutic modality at the preclinical and clinical level. The type I PRMT inhibitor, GSK3368715, recently entered phase I First Time in Humans clinical study in patients with solid tumours and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (Clinical Trial: NCT03666988) (Table 2).

Challenges in developing target-specific Type I inhibitors have not entirely prevented their adoption in the study of methyl-arginine biology. Several studies have utilised MS023 as a PRMT6 inhibitor to confirm results from knockdown or knockout experiments, including validating a role for PRMT6 in regulating global DNA methylation through obstruction of UHRF1, and in turn DNMT1, recruitment to chromatin [102] and as a repressor of the erythroid transcriptional program [103]. The dual PRMT6/4 inhibitor MS049 phenocopied PRMT6 knockout in the modulation of differentiation-associated genes by regulating the interplay of H3R2me2a and adjacent histone marks [104]. MS023 dramatically reduces cellular PRMT1-dependent methylation, and as such, it has been shown to affect TOP3B methylation, downstream transcription regulation, and stress granule sequestration [105]. Finally, selective PRMT4 inhibitors EZM2302 (GSK3359088) and TP-064 were initially characterized for anti-tumour activity in multiple myeloma [101, 106]. TP-064 was later used to confirm the link between PRMT4 and liver cancer, as well as regulation of metabolism through the methylation of GAPDH [107].

While most studies using PRMT inhibitors focus on implications in oncology, the involvement of arginine methylation in Treg cell suppressive function in xenogeneic graft-versus-host disease was discovered by screening PRMT inhibitors and shown to be dependent on the methylation of FOXP3 methylation [108]. Some PRMTs have been shown to have overlapping substrates. For example, G3BP1, RGG repeat protein, can be methylated by PRMT1 and PRMT5 to govern its downstream role in stress granule formation [109]. This sharing of substrates is consistent with the scavenging hypothesis, where downregulation of PRMT1 leads to other PRMTs monomethylating or symmetrically dimethylating the substrates that are usually methylated by PRMT1 [110]. Several studies have examined the cellular arginine methylated proteins at the global levels and enumerated hundreds of proteins involved in the RNA metabolism, translation, DNA damage, and stress response [111–115]. However, systematic studies on PRMT1 or other particular PRMT-dependent substrates are lacking, and selective inhibitors would greatly facilitate these types of studies.

Type II PRMT inhibitors

Type II PRMTs comprise PRMT5 and PRMT9, and for the latter, there are no selective inhibitors. PRMT5 chemical targeting has been intensely explored due to PRMT5’s attractiveness as an oncology target. EPZ015666/GSK3235025 was the first potent, selective, cell active, and orally bioavailable PRMT5 inhibitor to be reported [116]. It is classified as an SAM cofactor uncompetitive and substrate-competitive inhibitor; however, binding in the substrate pocket is dependent on the presence of the cofactor (Fig. 3a). EPZ015666 has in vitro activity of 22 nM, reduces the SMN complex component, SmB and SmD3 methylation in cells and specifically inhibits the growth of mantle cell lymphoma cells at concentrations below 1 μM [116]. Oral bioavailability of the molecule has enabled in vitro efficacy in cancer models at 25–200 mg/kg BID [116], which correlates with downregulation of an in vivo biomarker, indicating significant compound exposure. GSK3326595/EPZ015938, a compound with improved pharmacokinetic properties, is currently in phase I clinical trials for solid tumours and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (Table 2; Clinical Trial# NCT02783300). Given the broad anti-proliferative activity of this compound in numerous human cancer cell lines, this inhibitor is likely to be considered in additional therapeutic areas [117]. As a similar tool compound for the academic community, GSK591/EPZ015866 has facilitated the discovery of novel PRMT5 biology, including putative roles for PRMT5 in DNA repair and homologous recombination [118], HBV replication and encapsidation [119], and the antiviral response [120]. In addition, inhibition of PRMT5 or genetic knockdown has been shown to reduce PDGFRA methylation and increase its degradation during oligodendrocyte differentiation [121]. Other studies have investigated the effects of PRMT5 inhibition in developmental myelination [122], osteoclast differentiation [123], anti-tumoural activity in mouse models of MLL-rearranged AML [124], and breast cancer stem-cell maintenance [125]. It is not clear how much of PRMT5 biology is associated with transcriptional regulation via histone methylation or its prominent role in splicing regulation resulting in pervasive effects on the transcriptome [126, 127]. Further PRMT5-specific substrate identification may shed some light in this area. Recently, reported PRMT5 inhibitor, LLY-283, structurally resembles SAM and occupies the cofactor pocket in PRMT5 [128]. LLY-283 inhibited PRMT5 with a similar potency as the compounds mentioned above (20 nM); however, in cells, it was more potent inhibiting the methylation of SmBB′ with an IC50 of 25 nM in MCF7 cells and also eliciting the alternative splicing of MDM4 with an IC50 of 40 nM in A375 cells [128]. The compound displayed good pharmacokinetic properties. Thus, it will be interesting to follow its future clinical development.

Antagonists of methyl-binding domains

The biological consequence of protein methylation often proceeds through the recruitment of effector proteins containing methyl-lysine or methyl-arginine binding domains [129]. These reader modules are also frequently found within methyltransferase enzymes themselves, facilitating cross-talk between methyl marks and spreading of histone modifications within chromatin environments. Individual proteins will often contain several distinct reader modules with different binding capabilities. Potent, selective, and cell-active antagonists of reader function are, therefore, valuable tools to decipher the individual contributions of distinct reader domains in addition to uncovering potential therapeutic value. Historically, disruption of protein–protein interactions has been considered less tractable than inhibiting enzymatic activity. However, success in the field of bromodomain modulation by small-molecule antagonists and studies on methyl-lysine druggability have demonstrated the feasibility of drugging readers [130] (Fig. 4a). In addition to disrupting methyl-lysine effectors, reader antagonism also provides additional opportunities to alter the function of methyltransferases with pharmacologically challenging active sites or in cases of acquired resistance to enzymatic inhibitors.

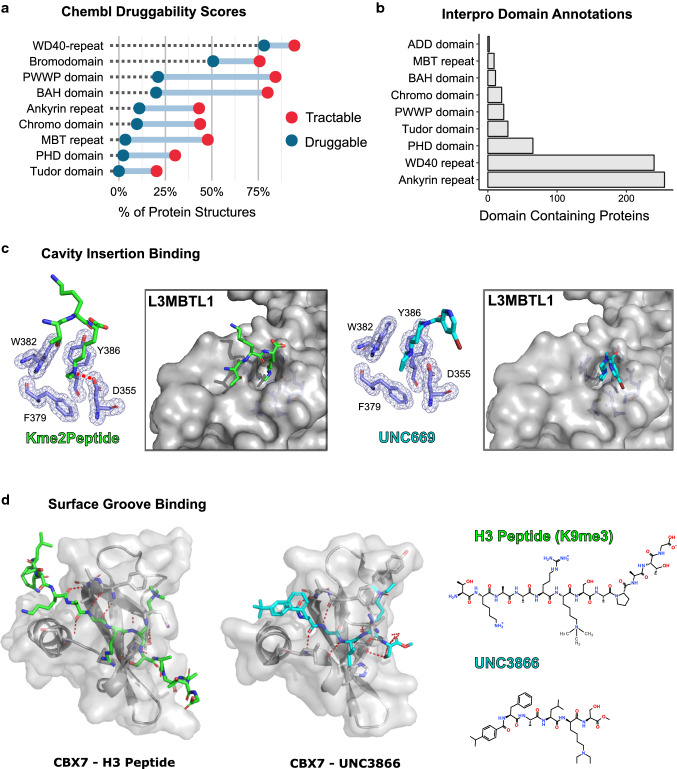

Fig. 4.

Targeting Methyl-lysine reader domains. a Reader domain druggability scores from the Chembl database [158]. Putative druggability varies significantly between families, indicating some families may be more tractable for the development of small-molecule antagonists. b Annotated reader module containing proteins in the Interpro database [159]. c L3MBT1L exhibits ‘cavity-insertion’ binding mode. Crystal structures of L3MBT1L bound to H1.5K27me2 peptide (PDB: 2RHI) or small-molecule UNC669 (PDB: 3P8H) (d) ‘surface-groove’ binding mode as exemplified by CBX7. NMR structure of CBX7 bound to an H3 peptide (PDB: 2L1B) and crystal structure of chemical probe UNC3866 in complex with CBX7 are shown (PDB: 5EPJ)

Methyl-binding activity has been observed in several protein families, including Ankyrin repeats, WD-40 repeats, bromo-adjacent homology (BAH)-containing proteins, Plant Homeodomain (PHD) fingers, and the Royal superfamily. These domains differ significantly in the frequency in which they appear in the human proteome, and not all are comprised exclusively of methyl-binding modules—for example, WD-40 and Ankyrin repeats are general protein–protein interaction surfaces found in many proteins (Fig. 4b). Typically, the methyl-binding site is composed of two-to-four aromatic residues that form an ‘aromatic cage’ [131]. Cation-π and van der Waals contacts primarily mediate the interaction with methylated residue. Recognition of a methyl mark can be generalised into two different distinct binding modes first put forward by Patel et al. [132] (Fig. 4c, d). ‘Cavity-insertion’ binders are characterized by insertion of the methylammonium into a deep and narrow-binding pocket with the methylated residue being the primary point of contact. Alternatively, ‘surface-groove’ binders make multiple contacts along the surface of a shallow and extended binding groove. These two classifications have been generally informative in defining chemical strategies for the discovery of antagonists, with cavity-insertion modes thought to be amenable to small molecule/fragment screening, while surface-groove binders may be better suited to peptidomimetic structure-based design [133]. Aside from antagonism of EED WD40-H3K27me3 binding, (described in detail for its allosteric regulation of PRC2 above), cell-active molecules have only been described for the Royal superfamily; none of which target the Tudor methyl-arginine binders. Derivatives of amiodarone (AMI), an antiarrhythmic drug, have been identified as antagonists of the third PHD domain of the demethylase JAIRD1A, WAG-03 (IC50 = 30 µM) and WAG-04 (IC50 = 41 µM); however, these compounds have not been shown to be active in cells [134, 135]. Therefore, this review will focus exclusively on antagonism of methyl-lysine binders from the Royal superfamily.

Royal family antagonists

Royal superfamily domains are defined by an evolutionarily conserved barrel-like protein fold (“Tudor barrel”), which consists of 4–5 anti-parallel β-strands that form a β-barrel-like fold [136]. This family is further sub-classified based on additional structural features that flank the fold and provide selectivity for specific methyl marks, and include Tudor, chromo, MBT (malignant brain tumour) and PWWP domains.

MBT repeats

MBT domains have been primarily characterized for their recognition of mono- and dimethylated lysine residues on histones via a “cavity-insertion” binding mode [137]. Found within Polycomb group and L3MBT proteins, they are comprised of ~ 70 amino acid repeats arrayed in tandem and generally act as transcriptional repressors [138]. The MBT domain of L3MBTL1 was the first methyl-lysine reader to be targeted in the form of UNC591, a biophysical probe designed to mimic a single lysine residue [139]. Shortly after, the first demonstration of reader antagonism, albeit with modest affinity, was achieved; UNC669 was shown to displace L3MBTL1 from a native histone peptide (Kd = 5 µM) with fivefold higher binding affinity and sixfold selectivity over its close homolog L3MBTL3 [140] (Fig. 4c). Further structure–activity relationship and target-class cross-screening approach eventually led to the development of a potent and selective chemical probe for L3MBTL3, UNC1215 (Kd = 120 nM) [141]. Mapping of protein–protein interactions by mass spectrometry in UNC1215 treated and untreated cells revealed a novel methyl-dependent interaction with the DNA damage repair factor BCLAF1, demonstrating the utility of probe-based approaches in the unbiased determination of reader module function. Additional structure–activity relationship studies of L3MBTL3 antagonists have also been informative in furthering our understanding of the molecular mechanisms of MBT binding partner recognition [142]. Interestingly, UNC1215 has also been shown to antagonize the interaction between the MBT-containing protein PHF20L and the SET7 substrate DNMT1-K142me1 resulting in increased DNMT1 turnover. However, this activity was only significant at a concentration > 40 µM compared to demonstrated activity towards L3MBTL3 at 1 µM [141, 143].

Tudor domain

Found in approximately ~ 30 mammalian proteins, Tudor domains recognize both methyl-lysine and methyl-arginine residues in histone and non-histone proteins [144]. To date, chemical antagonists for two members of this family have been described in the literature, 53BP1 and Spindlin 1. 53BP1 is a critical mediator of DNA double-strand break repair outcomes and acts by attenuating end-resection at the expense of homologous recombination. This activity has important implications for BRCA1-deficient cancers, gene editing, and immunology. UNC2170, a cell-active micromolar antagonist of 53BP1-Tudor binding to H4K20me2 (Kd = 22 µM), was discovered using a cross-screening approach of methyl-readers [145]. Promisingly, UNC2170 has been shown to disrupt recruitment of 53BP1 to damaged chromatin, albeit at relatively high concentrations of 300 µM [146]. Further improvements in compound potency will greatly benefit further exploration of 53BP1 as a medicinal target and as an adjuvant in gene editing applications by programmable nucleases [147]. In the case of Spindlin1, a target-hopping strategy was used to identify, EML631-633, cell-active antagonists of H3K4me3 binding, which has proven to be a useful tool in demonstrating Spindlin1-dependent gene regulation beyond previously described roles in the nucleolus [148]. As previously mentioned, the chemical probe A366 is also a nanomolar ligand of the Tudor domain of Spindlin1 [59]. This observation highlights the potential for potent off-target interactions of a chemical probe and suggests future probe validation would greatly benefit from broader and unbiased chemoproteomic-based selectivity screens [149].

Chromodomains

Chromodomains are found mostly in modular multi-domain proteins of the HP1/Chromobox and CHD subfamilies, which primarily function as transcriptional repressors and chromatin remodelers [150]. Chromodomains engage methylated peptides along a hydrophobic groove, which has been successfully targeted by several peptidomimetic small molecules. The first such example was a ~ 200 nM compound to CBX7, a PRC1 associated reader of H3K27me3 [151]. PRC1 complexes regulate vital transcriptional programs involved in development, self-renewal, senescence, and oncogenesis with the target of its repressive activity often dictated by the associated CBX protein [152]. Overexpression of CBX7 can promote the proliferation of tumour-derived prostate cancer cells, which is thought to occur through the suppression of the senescence-associated INK4a/ARF locus, making it a potential target in cancer [153]. Encouragingly, UNC3866, which targets several CBX proteins with exquisite potency to CBX4 and CBX7, initiates senescence in the PC3 prostate cancer cell line [154]. Structural biology studies of the compounds binding mode showed that UNC3866 binds similar to the H3 peptide (Fig. 4d). Surprisingly, this phenotype was independent of INK4a/ARF regulation. Structure-guided discovery has led to the identification of two-additional classes of CBX7 antagonists, analogues of the compounds MS452 and MS351, that show similar binding to CBX7, however, differentially regulate the INK4a/ARF locus in cells [155, 156]. Interestingly, it appears the compound that activates INK4a/ARF expression, MS352, selectively targets the biologically active, RNA-bound, form of CBX7. These observations may explain some of the discrepancies reported in the literature. However, further research will be required to decipher the molecular and mechanistic details of the anti-cancer activity of CBX7 antagonists if this effect is indeed through the regulation of the INK4a/ARF locus.

Concluding remarks

In a relatively short period, we have witnessed the advance of protein methyltransferase inhibitors from tool compounds to precision medicines. Several promising compounds are now in clinical trials in oncology. These efforts have not only led to new medicines, but have also greatly expanded our knowledge of the underlying biology of protein methylation. Here, we have outlined the general modalities of PMT inhibition and describe many breakthroughs in the discovery of chemical inhibitors. Selective, potent, and cell-active inhibitors of both lysine and arginine methyltransferases have been developed by exploiting the cofactor-binding site, substrate peptide-binding site and less commonly distal allosteric pockets. Many of the inhibitors described here are available for the research community to probe mechanistic questions in biology and test translational research hypothesises. More recently, there has also been significant progress in the identification of methyl-lysine reader antagonists. These compounds will be valuable for interrogating the downstream effectors of protein methylation as well as the function of reader domains within the context of large multi-domain proteins, including PMTs themselves. From a therapeutic standpoint, reader antagonism may provide alternative routes to modulate methyl signalling pathways in disease, which may be particularly valuable in cases, where resistance has developed to existing clinical candidates. While significant progress has been made, there remains much to learn about the pharmacology and biology of most protein methyltransferases; it is without a doubt that chemical biology will continue to play a vital role in advancing the field.

Acknowledgements

The authors receive supported from a fellowship from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (DD) and the SGC, a registered charity (number 1097737) that receives funds from AbbVie, Bayer Pharma AG, Boehringer Ingelheim, Canada Foundation for Innovation, Eshelman Institute for Innovation, Genome Canada through Ontario Genomics Institute [OGI-055], Innovative Medicines Initiative (EU/EFPIA) [ULTRA-DD grant no. 115766], Janssen, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany, MSD, Novartis Pharma AG, Ontario Ministry of Research, Innovation and Science (MRIS), Pfizer, São Paulo Research Foundation—FAPESP, Takeda, and Wellcome [106169/ZZ14/Z]. We thank Dr Peter J Brown for help with the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ambler RP, Rees MW. ε-N-methyl-lysine in bacterial flagellar protein. Nature. 1959;184:56–57. doi: 10.1038/184056b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray K. the occurrence of epsilon-N-methyl lysine in histones. Biochemistry. 1964;3:10–15. doi: 10.1021/bi00889a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murn J, Shi Y. The winding path of protein methylation research: milestones and new frontiers. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2017;18:517–527. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2017.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clarke SG. Protein methylation at the surface and buried deep: thinking outside the histone box. Trends Biochem Sci. 2013;38:243–252. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kwiatkowski S, Seliga AK, Vertommen D, Terreri M, Ishikawa T, Grabowska I, Tiebe M, Teleman AA, Jagielski AK, Veiga-da-Cunha M, Drozak J. SETD3 protein is the actin-specific histidine N-methyltransferase. Elife. 2018 doi: 10.7554/eLife.37921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilkinson AW, Diep J, Dai S, Liu S, Ooi YS, Song D, Li T-M, Horton JR, Zhang X, Liu C, Trivedi DV, Ruppel KM, Vilches-Moure JG, Casey KM, Mak J, Cowan T, Elias JE, Nagamine CM, Spudich JA, Cheng X, Carette JE, Gozani O. SETD3 is an actin histidine methyltransferase that prevents primary dystocia. Nature. 2019;565:372–376. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0821-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bannister AJ, Kouzarides T. Reversing histone methylation. Nature. 2005;436:1103–1106. doi: 10.1038/nature04048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hornbeck PV, Zhang B, Murray B, Kornhauser JM, Latham V, Skrzypek E. PhosphoSitePlus, 2014: mutations, PTMs and recalibrations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D512–D520. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bannister AJ, Kouzarides T. Regulation of chromatin by histone modifications. Cell Res. 2011;21:381–395. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dawson MA, Kouzarides T. Cancer epigenetics: from mechanism to therapy. Cell. 2012;150:12–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Portela A, Esteller M. Epigenetic modifications and human disease. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:1057–1068. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greer EL, Shi Y. Histone methylation: a dynamic mark in health, disease and inheritance. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:343–357. doi: 10.1038/nrg3173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones PA, Issa J-PJ, Baylin S. Targeting the cancer epigenome for therapy. Nat Rev Genet. 2016;17:630–641. doi: 10.1038/nrg.2016.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arrowsmith CH, Bountra C, Fish PV, Lee K, Schapira M. Epigenetic protein families: a new frontier for drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2012;11:384–400. doi: 10.1038/nrd3674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Copeland RA. Protein methyltransferase inhibitors as precision cancer therapeutics: a decade of discovery. Sci: Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol; 2018. p. 373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamamoto R, Saloura V, Nakamura Y. Critical roles of non-histone protein lysine methylation in human tumorigenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15:110–124. doi: 10.1038/nrc3884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buuh ZY, Lyu Z, Wang RE. Interrogating the roles of post-translational modifications of non-histone proteins. J Med Chem. 2018;61:3239–3252. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kubicek S, O’Sullivan RJ, August EM, Hickey ER, Zhang Q, Teodoro ML, Rea S, Mechtler K, Kowalski JA, Homon CA, Kelly TA, Jenuwein T. Reversal of H3K9me2 by a small-molecule inhibitor for the G9a histone methyltransferase. Mol Cell. 2007;25:473–481. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blagg J, Workman P. Choose and use your chemical probe wisely to explore cancer biology. Cancer Cell. 2017;32:9–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arrowsmith CH, Audia JE, Austin C, Baell J, Bennett J, Blagg J, Bountra C, Brennan PE, Brown PJ, Bunnage ME, Buser-Doepner C, Campbell RM, Carter AJ, Cohen P, Copeland RA, Cravatt B, Dahlin JL, Dhanak D, Edwards AM, Frederiksen M, Frye SV, Gray N, Grimshaw CE, Hepworth D, Howe T, Huber KVM, Jin J, Knapp S, Kotz JD, Kruger RG, Lowe D, Mader MM, Marsden B, Mueller-Fahrnow A, Mueller S, O’Hagan RC, Overington JP, Owen DR, Rosenberg SH, Ross R, Roth B, Schapira M, Schreiber SL, Shoichet B, Sundstroem M, Superti-Furga G, Taunton J, Toledo-Sherman L, Walpole C, Walters MA, Willson TM, Workman P, Young RN, Zuercher WJ. The promise and peril of chemical probes (vol 11, pg 536, 2015) Nat Chem Biol. 2015;11:887. doi: 10.1038/nchembio1115-887c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frye SV. The art of the chemical probe. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:159–161. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Filippakopoulos P, Qi J, Picaud S, Shen Y, Smith WB, Fedorov O, Morse EM, Keates T, Hickman TT, Felletar I, Philpott M, Munro S, McKeown MR, Wang Y, Christie AL, West N, Cameron MJ, Schwartz B, Heightman TD, La Thangue N, French CA, Wiest O, Kung AL, Knapp S, Bradner JE. Selective inhibition of BET bromodomains. Nature. 2010;468:1067–1073. doi: 10.1038/nature09504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nicodeme E, Jeffrey KL, Schaefer U, Beinke S, Dewell S, Chung C-W, Chandwani R, Marazzi I, Wilson P, Coste H, White J, Kirilovsky J, Rice CM, Lora JM, Prinjha RK, Lee K, Tarakhovsky A. Suppression of inflammation by a synthetic histone mimic. Nature. 2010;468:1119–1123. doi: 10.1038/nature09589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brand M, Measures AR, Wilson BG, Cortopassi WA, Alexander R, Hoss M, Hewings DS, Rooney TPC, Paton RS, Conway SJ. Small molecule inhibitors of bromodomain-acetyl-lysine interactions. ACS Chem Biol. 2015;10:22–39. doi: 10.1021/cb500996u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen P, Chaikuad A, Bamborough P, Bantscheff M, Bountra C, Chung C-W, Fedorov O, Grandi P, Jung D, Lesniak R, Lindon M, Muller S, Philpott M, Prinjha R, Rogers C, Selenski C, Tallant C, Werner T, Willson TM, Knapp S, Drewry DH. Discovery and characterization of GSK2801, a selective chemical probe for the bromodomains BAZ2A and BAZ2B. J Med Chem. 2016;59:1410–1424. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clark PGK, Vieira LCC, Tallant C, Fedorov O, Singleton DC, Rogers CM, Monteiro OP, Bennett JM, Baronio R, Muller S, Daniels DL, Mendez J, Knapp S, Brennan PE, Dixon DJ. LP99: discovery and synthesis of the first selective BRD7/9 bromodomain inhibitor. Angew Chem Weinheim Bergstr Ger. 2015;127:6315–6319. doi: 10.1002/ange.201501394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Drouin L, McGrath S, Vidler LR, Chaikuad A, Monteiro O, Tallant C, Philpott M, Rogers C, Fedorov O, Liu M, Akhtar W, Hayes A, Raynaud F, Muller S, Knapp S, Hoelder S. Structure enabled design of BAZ2-ICR, a chemical probe targeting the bromodomains of BAZ2A and BAZ2B. J Med Chem. 2015;58:2553–2559. doi: 10.1021/jm501963e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fish PV, Filippakopoulos P, Bish G, Brennan PE, Bunnage ME, Cook AS, Federov O, Gerstenberger BS, Jones H, Knapp S, Marsden B, Nocka K, Owen DR, Philpott M, Picaud S, Primiano MJ, Ralph MJ, Sciammetta N, Trzupek JD. Identification of a chemical probe for bromo and extra C-terminal bromodomain inhibition through optimization of a fragment-derived hit. J Med Chem. 2012;55:9831–9837. doi: 10.1021/jm3010515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hay DA, Fedorov O, Martin S, Singleton DC, Tallant C, Wells C, Picaud S, Philpott M, Monteiro OP, Rogers CM, Conway SJ, Rooney TPC, Tumber A, Yapp C, Filippakopoulos P, Bunnage ME, Muller S, Knapp S, Schofield CJ, Brennan PE. Discovery and optimization of small-molecule ligands for the CBP/p300 bromodomains. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:9308–9319. doi: 10.1021/ja412434f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vazquez R, Riveiro ME, Astorgues-Xerri L, Odore E, Rezai K, Erba E, Panini N, Rinaldi A, Kwee I, Beltrame L, Bekradda M, Cvitkovic E, Bertoni F, Frapolli R, D’Incalci M. The bromodomain inhibitor OTX015 (MK-8628) exerts anti-tumor activity in triple-negative breast cancer models as single agent and in combination with everolimus. Oncotarget. 2017;8:7598–7613. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scheer S, Ackloo S, Medina TS, Schapira M, Li F, Ward JA, Lewis AM, Northrop JP, Richardson PL, Kaniskan HÜ, Shen Y, Liu J, Smil D, McLeod D, Zepeda-Velazquez CA, Luo M, Jin J, Barsyte-Lovejoy D, Huber KVM, De Carvalho DD, Vedadi M, Zaph C, Brown PJ, Arrowsmith CH. A chemical biology toolbox to study protein methyltransferases and epigenetic signaling. Nat Commun. 2019;10:19. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07905-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Borchardt RT, Shiong Y, Huber JA, Wycpalek AF. Potential inhibitors of S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methyltransferases. 6. Structural modifications of S-adenosylmethionine. J Med Chem. 1976;19:1104–1110. doi: 10.1021/jm00231a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vedel M, Lawrence F, Robert-Gero M, Lederer E. The antifungal antibiotic sinefungin as a very active inhibitor of methyltransferases and of the transformation of chick embryo fibroblasts by Rous sarcoma virus. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1978;85:371–376. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(78)80052-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Greiner D, Bonaldi T, Eskeland R, Roemer E, Imhof A. Identification of a specific inhibitor of the histone methyltransferase SU(VAR)3-9. Nat Chem Biol. 2005;1:143–145. doi: 10.1038/nchembio721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cherblanc FL, Chapman KL, Brown R, Fuchter MJ. Chaetocin is a nonspecific inhibitor of histone lysine methyltransferases. Nat Chem Biol. 2013;9:136–137. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bartel RL, Borchardt RT. Effects of adenosine dialdehyde on S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase and S-adenosylmethionine-dependent transmethylations in mouse L929 cells. Mol Pharmacol. 1984;25:418–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tehlivets O, Malanovic N, Visram M, Pavkov-Keller T, Keller W. S-adenosyl-L-homocysteine hydrolase and methylation disorders: yeast as a model system. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2013;1832:204–215. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2012.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miranda TB, Cortez CC, Yoo CB, Liang G, Abe M, Kelly TK, Marquez VE, Jones PA. DZNep is a global histone methylation inhibitor that reactivates developmental genes not silenced by DNA methylation. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:1579–1588. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Campagna-Slater V, Mok MW, Nguyen KT, Feher M, Najmanovich R, Schapira M. Structural chemistry of the histone methyltransferases cofactor binding site. J Chem Inf Model. 2011;51:612–623. doi: 10.1021/ci100479z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schapira M. Chemical inhibition of protein methyltransferases. Cell Chem Biol. 2016;23:1067–1076. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2016.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boriack-Sjodin PA, Swinger KK. Protein methyltransferases: a distinct, diverse, and dynamic family of enzymes. Biochemistry. 2016;55:1557–1569. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b01129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.He Y, Selvaraju S, Curtin ML, Jakob CG, Zhu H, Comess KM, Shaw B, The J, Lima-Fernandes E, Szewczyk MM, Cheng D, Klinge KL, Li H-Q, Pliushchev M, Algire MA, Maag D, Guo J, Dietrich J, Panchal SC, Petros AM, Sweis RF, Torrent M, Bigelow LJ, Senisterra G, Li F, Kennedy S, Wu Q, Osterling DJ, Lindley DJ, Gao W, Galasinski S, Barsyte-Lovejoy D, Vedadi M, Buchanan FG, Arrowsmith CH, Chiang GG, Sun C, Pappano WN. The EED protein-protein interaction inhibitor A-395 inactivates the PRC2 complex. Nat Chem Biol. 2017;13:389–395. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qi W, Zhao K, Gu J, Huang Y, Wang Y, Zhang H, Zhang M, Zhang J, Yu Z, Li L, Teng L, Chuai S, Zhang C, Zhao M, Chan H, Chen Z, Fang D, Fei Q, Feng L, Feng L, Gao Y, Ge H, Ge X, Li G, Lingel A, Lin Y, Liu Y, Luo F, Shi M, Wang L, Wang Z, Yu Y, Zeng J, Zeng C, Zhang L, Zhang Q, Zhou S, Oyang C, Atadja P, Li E. An allosteric PRC2 inhibitor targeting the H3K27me3 binding pocket of EED. Nat Chem Biol. 2017;13:381–388. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kaniskan HU, Eram MS, Zhao K, Szewczyk MM, Yang X, Schmidt K, Luo X, Xiao S, Dai M, He F, Zang I, Lin Y, Li F, Dobrovetsky E, Smil D, Min S-J, Lin-Jones J, Schapira M, Atadja P, Li E, Barsyte-Lovejoy D, Arrowsmith CH, Brown PJ, Liu F, Yu Z, Vedadi M, Jin J. Discovery of potent and selective allosteric inhibitors of protein arginine methyltransferase 3 (PRMT3) J Med Chem. 2018;61:1204–1217. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kaniskan HU, Szewczyk MM, Yu Z, Eram MS, Yang X, Schmidt K, Luo X, Dai M, He F, Zang I, Lin Y, Kennedy S, Li F, Dobrovetsky E, Dong A, Smil D, Min S-J, Landon M, Lin-Jones J, Huang X-P, Roth BL, Schapira M, Atadja P, Barsyte-Lovejoy D, Arrowsmith CH, Brown PJ, Zhao K, Jin J, Vedadi M. A potent, selective and cell-active allosteric inhibitor of protein arginine methyltransferase 3 (PRMT3) Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2015;54:5166–5170. doi: 10.1002/anie.201412154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Richon VM, Johnston D, Sneeringer CJ, Jin L, Majer CR, Elliston K, Jerva LF, Scott MP, Copeland RA. Chemogenetic analysis of human protein methyltransferases. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2011;78:199–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2011.01135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chouhan BPS, Maimaiti S, Gade M, Laurino P. Rossmann-fold methyltransferases: taking a “β-Turn” around their cofactor, S -adenosylmethionine. Biochemistry. 2019;58:166–170. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.8b00994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kaniskan HU, Martini ML, Jin J. Inhibitors of protein methyltransferases and demethylases. Chem Rev. 2018;118:989–1068. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kaniskan HÜ, Jin J. Recent progress in developing selective inhibitors of protein methyltransferases. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2017;39:100–108. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2017.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kaniskan HÜ, Jin J. Chemical probes of histone lysine methyltransferases. ACS Chem Biol. 2015;10:40–50. doi: 10.1021/cb500785t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chang Y, Zhang X, Horton JR, Upadhyay AK, Spannhoff A, Liu J, Snyder JP, Bedford MT, Cheng X. Structural basis for G9a-like protein lysine methyltransferase inhibition by BIX-01294. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:312–317. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shi Y, Desponts C, Do JT, Hahm HS, Scholer HR, Ding S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic fibroblasts by Oct4 and Klf4 with small-molecule compounds. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:568–574. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shi Y, Do JT, Desponts C, Hahm HS, Schöler HR, Ding S. A combined chemical and genetic approach for the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:525–528. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Imai K, Togami H, Okamoto T. Involvement of histone H3 lysine 9 (H3K9) methyltransferase G9a in the maintenance of HIV-1 latency and its reactivation by BIX01294. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:16538–16545. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.103531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vedadi M, Barsyte-Lovejoy D, Liu F, Rival-Gervier S, Allali-Hassani A, Labrie V, Wigle TJ, DiMaggio PA, Wasney GA, Siarheyeva A, Dong A, Tempel W, Wang S-C, Chen X, Chau I, Mangano TJ, Huang X, Simpson CD, Pattenden SG, Norris JL, Kireev DB, Tripathy A, Edwards A, Roth BL, Janzen WP, Garcia BA, Petronis A, Ellis J, Brown PJ, Frye SV, Arrowsmith CH, Jin J. A chemical probe selectively inhibits G9a and GLP methyltransferase activity in cells. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:566–574. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu F, Barsyte-Lovejoy D, Li F, Xiong Y, Korboukh V, Huang X-P, Allali-Hassani A, Janzen WP, Roth BL, Frye SV, Arrowsmith CH, Brown PJ, Vedadi M, Jin J. Discovery of an in vivo chemical probe of the lysine methyltransferases G9a and GLP. J Med Chem. 2013;56:8931–8942. doi: 10.1021/jm401480r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sweis RF, Pliushchev M, Brown PJ, Guo J, Li F, Maag D, Petros AM, Soni NB, Tse C, Vedadi M, Michaelides MR, Chiang GG, Pappano WN. Discovery and development of potent and selective inhibitors of histone methyltransferase G9a. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2014;5:205–209. doi: 10.1021/ml400496h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pappano WN, Guo J, He Y, Ferguson D, Jagadeeswaran S, Osterling DJ, Gao W, Spence JK, Pliushchev M, Sweis RF, Buchanan FG, Michaelides MR, Shoemaker AR, Tse C, Chiang GG. The histone methyltransferase inhibitor A-366 uncovers a role for G9a/GLP in the epigenetics of leukemia. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0131716. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wagner T, Greschik H, Burgahn T, Schmidtkunz K, Schott A-K, McMillan J, Baranauskienė L, Xiong Y, Fedorov O, Jin J, Oppermann U, Matulis D, Schüle R, Jung M. Identification of a small-molecule ligand of the epigenetic reader protein Spindlin1 via a versatile screening platform. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:e88. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Casciello F, Windloch K, Gannon F, Lee JS. Functional role of G9a histone methyltransferase in cancer. Front Immunol. 2015;6:487. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang X, Huang Y, Shi X. Emerging roles of lysine methylation on non-histone proteins. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2015;72:4257–4272. doi: 10.1007/s00018-015-2001-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Komatsu S, Imoto I, Tsuda H, Kozaki K, Muramatsu T, Shimada Y, Aiko S, Yoshizumi Y, Ichikawa D, Otsuji E, Inazawa J. Overexpression of SMYD2 relates to tumor cell proliferation and malignant outcome of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:1139–1146. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Komatsu S, Ichikawa D, Hirajima S, Nagata H, Nishimura Y, Kawaguchi T, Miyamae M, Okajima W, Ohashi T, Konishi H, Shiozaki A, Fujiwara H, Okamoto K, Tsuda H, Imoto I, Inazawa J, Otsuji E. Overexpression of SMYD2 contributes to malignant outcome in gastric cancer. Br J Cancer. 2015;112:357–364. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cho H-S, Hayami S, Toyokawa G, Maejima K, Yamane Y, Suzuki T, Dohmae N, Kogure M, Kang D, Neal DE, Ponder BAJ, Yamaue H, Nakamura Y, Hamamoto R. RB1 methylation by SMYD2 enhances cell cycle progression through an increase of RB1 phosphorylation. Neoplasia. 2012;14:476–486. doi: 10.1593/neo.12656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sakamoto LHT, de Andrade RV, Felipe MSS, Motoyama AB, Pittella Silva F. SMYD2 is highly expressed in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia and constitutes a bad prognostic factor. Leuk Res. 2014;38:496–502. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2014.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cowen SD, Russell D, Dakin LA, Chen H, Larsen NA, Godin R, Throner S, Zheng X, Molina A, Wu J, Cheung T, Howard T, Garcia-Arenas R, Keen N, Pendleton CS, Pietenpol JA, Ferguson AD. Design, synthesis, and biological activity of substrate competitive SMYD2 inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2016;59:11079–11097. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ferguson AD, Larsen NA, Howard T, Pollard H, Green I, Grande C, Cheung T, Garcia-Arenas R, Cowen S, Wu J, Godin R, Chen H, Keen N. Structural basis of substrate methylation and inhibition of SMYD2. Structure. 2011;19:1262–1273. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li LX, Zhou JX, Calvet JP, Godwin AK, Jensen RA, Li X. Lysine methyltransferase SMYD2 promotes triple negative breast cancer progression. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:326. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0347-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sweis RF, Wang Z, Algire M, Arrowsmith CH, Brown PJ, Chiang GG, Guo J, Jakob CG, Kennedy S, Li F, Maag D, Shaw B, Soni NB, Vedadi M, Pappano WN. Discovery of A-893, a new cell-active benzoxazinone inhibitor of lysine methyltransferase SMYD2. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2015;6:695–700. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.5b00124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nguyen H, Allali-Hassani A, Antonysamy S, Chang S, Chen LH, Curtis C, Emtage S, Fan L, Gheyi T, Li F, Liu S, Martin JR, Mendel D, Olsen JB, Pelletier L, Shatseva T, Wu S, Zhang FF, Arrowsmith CH, Brown PJ, Campbell RM, Garcia BA, Barsyte-Lovejoy D, Mader M, Vedadi M. LLY-507, a cell-active, potent, and selective inhibitor of protein-lysine methyltransferase SMYD2. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:13641–13653. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.626861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Huang J, Perez-Burgos L, Placek BJ, Sengupta R, Richter M, Dorsey JA, Kubicek S, Opravil S, Jenuwein T, Berger SL. Repression of p53 activity by Smyd2-mediated methylation. Nature. 2006;444:629–632. doi: 10.1038/nature05287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Eggert E, Hillig RC, Koehr S, Stockigt D, Weiske J, Barak N, Mowat J, Brumby T, Christ CD, Ter Laak A, Lang T, Fernandez-Montalvan AE, Badock V, Weinmann H, Hartung IV, Barsyte-Lovejoy D, Szewczyk M, Kennedy S, Li F, Vedadi M, Brown PJ, Santhakumar V, Arrowsmith CH, Stellfeld T, Stresemann C. Discovery and characterization of a highly potent and selective aminopyrazoline-based in vivo probe (BAY-598) for the protein lysine methyltransferase SMYD2. J Med Chem. 2016;59:4578–4600. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Thomenius MJ, Totman J, Harvey D, Mitchell LH, Riera TV, Cosmopoulos K, Grassian AR, Klaus C, Foley M, Admirand EA, Jahic H, Majer C, Wigle T, Jacques SL, Gureasko J, Brach D, Lingaraj T, West K, Smith S, Rioux N, Waters NJ, Tang C, Raimondi A, Munchhof M, Mills JE, Ribich S, Porter Scott M, Kuntz KW, Janzen WP, Moyer M, Smith JJ, Chesworth R, Copeland RA, Boriack-Sjodin PA. Small molecule inhibitors and CRISPR/Cas9 mutagenesis demonstrate that SMYD2 and SMYD3 activity are dispensable for autonomous cancer cell proliferation. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0197372. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0197372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Peserico A, Germani A, Sanese P, Barbosa AJ, Di Virgilio V, Fittipaldi R, Fabini E, Bertucci C, Varchi G, Moyer MP, Caretti G, Del Rio A, Simone C. A SMYD3 small-molecule inhibitor impairing cancer cell growth. J Cell Physiol. 2015;230:2447–2460. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Van Aller GS, Graves AP, Elkins PA, Bonnette WG, McDevitt PJ, Zappacosta F, Annan RS, Dean TW, Su D-S, Carpenter CL, Mohammad HP, Kruger RG. Structure-based design of a novel SMYD3 inhibitor that bridges the SAM-and MEKK2-binding pockets. Structure. 2016;24:774–781. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2016.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nguyen AT, Zhang Y. The diverse functions of Dot1 and H3K79 methylation. Genes Dev. 2011;25:1345–1358. doi: 10.1101/gad.2057811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nguyen AT, Taranova O, He J, Zhang Y. DOT1L, the H3K79 methyltransferase, is required for MLL-AF9-mediated leukemogenesis. Blood. 2011;117:6912–6922. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-334359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yu W, Chory EJ, Wernimont AK, Tempel W, Scopton A, Federation A, Marineau JJ, Qi J, Barsyte-Lovejoy D, Yi J, Marcellus R, Iacob RE, Engen JR, Griffin C, Aman A, Wienholds E, Li F, Pineda J, Estiu G, Shatseva T, Hajian T, Al-Awar R, Dick JE, Vedadi M, Brown PJ, Arrowsmith CH, Bradner JE, Schapira M. Catalytic site remodelling of the DOT1L methyltransferase by selective inhibitors. Nat Commun. 2012;3:1288. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Daigle SR, Olhava EJ, Therkelsen CA, Basavapathruni A, Jin L, Boriack-Sjodin PA, Allain CJ, Klaus CR, Raimondi A, Scott MP, Waters NJ, Chesworth R, Moyer MP, Copeland RA, Richon VM, Pollock RM. Potent inhibition of DOT1L as treatment of MLL-fusion leukemia. Blood. 2013;122:1017–1025. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-04-497644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Margueron R, Reinberg D. The Polycomb complex PRC2 and its mark in life. Nature. 2011;469:343–349. doi: 10.1038/nature09784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Knutson SK, Wigle TJ, Warholic NM, Sneeringer CJ, Allain CJ, Klaus CR, Sacks JD, Raimondi A, Majer CR, Song J, Scott MP, Jin L, Smith JJ, Olhava EJ, Chesworth R, Moyer MP, Richon VM, Copeland RA, Keilhack H, Pollock RM, Kuntz KW. A selective inhibitor of EZH2 blocks H3K27 methylation and kills mutant lymphoma cells. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;8:890–896. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.McCabe MT, Ott HM, Ganji G, Korenchuk S, Thompson C, Van Aller GS, Liu Y, Graves AP, Della Pietra A, 3rd, Diaz E, LaFrance LV, Mellinger M, Duquenne C, Tian X, Kruger RG, McHugh CF, Brandt M, Miller WH, Dhanak D, Verma SK, Tummino PJ, Creasy CL. EZH2 inhibition as a therapeutic strategy for lymphoma with EZH2-activating mutations. Nature. 2012;492:108–112. doi: 10.1038/nature11606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Konze KD, Ma A, Li F, Barsyte-Lovejoy D, Parton T, Macnevin CJ, Liu F, Gao C, Huang X-P, Kuznetsova E, Rougie M, Jiang A, Pattenden SG, Norris JL, James LI, Roth BL, Brown PJ, Frye SV, Arrowsmith CH, Hahn KM, Wang GG, Vedadi M, Jin J. An orally bioavailable chemical probe of the lysine methyltransferases EZH2 and EZH1. ACS Chem Biol. 2013;8:1324–1334. doi: 10.1021/cb400133j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Knutson SK, Warholic NM, Wigle TJ, Klaus CR, Allain CJ, Raimondi A, Porter Scott M, Chesworth R, Moyer MP, Copeland RA, Richon VM, Pollock RM, Kuntz KW, Keilhack H. Durable tumor regression in genetically altered malignant rhabdoid tumors by inhibition of methyltransferase EZH2. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 2013;110:7922–7927. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303800110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sneeringer CJ, Scott MP, Kuntz KW, Knutson SK, Pollock RM, Richon VM, Copeland RA. Coordinated activities of wild-type plus mutant EZH2 drive tumor-associated hypertrimethylation of lysine 27 on histone H3 (H3K27) in human B-cell lymphomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2010;107:20980–20985. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012525107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wilson BG, Wang X, Shen X, McKenna ES, Lemieux ME, Cho Y-J, Koellhoffer EC, Pomeroy SL, Orkin SH, Roberts CWM. Epigenetic antagonism between polycomb and SWI/SNF complexes during oncogenic transformation. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:316–328. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Schapira M, Tyers M, Torrent M, Arrowsmith CH. WD40 repeat domain proteins: a novel target class? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017;16:773–786. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Song R, Wang Z-D, Schapira M. Disease association and druggability of WD40 repeat proteins. J Proteome Res. 2017;16:3766–3773. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.7b00451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Margueron R, Justin N, Ohno K, Sharpe ML, Son J, Drury WJ, III, Voigt P, Martin SR, Taylor WR, De Marco V, Pirrotta V, Reinberg D, Gamblin SJ. Role of the polycomb protein EED in the propagation of repressive histone marks. Nature. 2009;461:762–767. doi: 10.1038/nature08398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Baker T, Nerle S, Pritchard J, Zhao B, Rivera VM, Garner A, Gonzalvez F. Acquisition of a single EZH2 D1 domain mutation confers acquired resistance to EZH2-targeted inhibitors. Oncotarget. 2015;6:32646–32655. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gibaja V, Shen F, Harari J, Korn J, Ruddy D, Saenz-Vash V, Zhai H, Rejtar T, Paris CG, Yu Z, Lira M, King D, Qi W, Keen N, Hassan AQ, Chan HM. Development of secondary mutations in wild-type and mutant EZH2 alleles cooperates to confer resistance to EZH2 inhibitors. Oncogene. 2016;35:558–566. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Cheng X, Collins RE, Zhang X. Structural and sequence motifs of protein (histone) methylation enzymes. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2005;34:267–294. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.34.040204.144452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Schapira M, Ferreira de Freitas R. Structural biology and chemistry of protein arginine methyltransferases. Medchemcomm. 2014;5:1779–1788. doi: 10.1039/C4MD00269E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hasegawa M, Toma-Fukai S, Kim J-D, Fukamizu A, Shimizu T. Protein arginine methyltransferase 7 has a novel homodimer-like structure formed by tandem repeats. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:1942–1948. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Antonysamy S, Bonday Z, Campbell RM, Doyle B, Druzina Z, Gheyi T, Han B, Jungheim LN, Qian Y, Rauch C, Russell M, Sauder JM, Wasserman SR, Weichert K, Willard FS, Zhang A, Emtage S. Crystal structure of the human PRMT5:mEP50 complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:17960–17965. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209814109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hu H, Qian K, Ho M-C, Zheng YG. Small molecule inhibitors of protein arginine methyltransferases. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2016;25:335–358. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2016.1144747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Siarheyeva A, Senisterra G, Allali-Hassani A, Dong A, Dobrovetsky E, Wasney GA, Chau I, Marcellus R, Hajian T, Liu F, Korboukh I, Smil D, Bolshan Y, Min J, Wu H, Zeng H, Loppnau P, Poda G, Griffin C, Aman A, Brown PJ, Jin J, Al-Awar R, Arrowsmith CH, Schapira M, Vedadi M. An allosteric inhibitor of protein arginine methyltransferase 3. Structure. 2012;20:1425–1435. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Eram MS, Shen Y, Szewczyk M, Wu H, Senisterra G, Li F, Butler KV, Kaniskan HU, Speed BA, Dela Sena C, Dong A, Zeng H, Schapira M, Brown PJ, Arrowsmith CH, Barsyte-Lovejoy D, Liu J, Vedadi M, Jin J. A potent, selective, and cell-active inhibitor of human type I protein arginine methyltransferases. ACS Chem Biol. 2016;11:772–781. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.5b00839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Mitchell LH, Drew AE, Ribich SA, Rioux N, Swinger KK, Jacques SL, Lingaraj T, Boriack-Sjodin PA, Waters NJ, Wigle TJ, Moradei O, Jin L, Riera T, Porter-Scott M, Moyer MP, Smith JJ, Chesworth R, Copeland RA. Aryl pyrazoles as potent inhibitors of arginine methyltransferases: identification of the first PRMT6 tool compound. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2015;6:655–659. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.5b00071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]