Abstract

A number of studies have demonstrated that transplantation of neural precursor cells (NPCs) promotes functional recovery after spinal cord injury (SCI). However, the NPCs had been mostly harvested from embryonic stem cells or fetal tissue, raising the ethical concern. Yamanaka and his colleagues established induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) which could be generated from somatic cells, and this innovative development has made rapid progression in the field of SCI regeneration. We and other groups succeeded in producing NPCs from iPSCs, and demonstrated beneficial effects after transplantation for animal models of SCI. In particular, efficacy of human iPSC–NPCs in non-human primate SCI models fostered momentum of clinical application for SCI patients. At the same time, however, artificial induction methods in iPSC technology created alternative issues including genetic and epigenetic abnormalities, and tumorigenicity after transplantation. To overcome these problems, it is critically important to select origins of somatic cells, use integration-free system during transfection of reprogramming factors, and thoroughly investigate the characteristics of iPSC–NPCs with respect to quality management. Moreover, since most of the previous studies have focused on subacute phase of SCI, establishment of effective NPC transplantation should be evaluated for chronic phase hereafter. Our group is currently preparing clinical-grade human iPSC–NPCs, and will move forward toward clinical study for subacute SCI patients soon in the near future.

Keywords: Central nervous system, Stem cell graft, Regeneration, Mechanisms for functional recovery, Safety issue

Introduction

Regeneration of the central nervous system (CNS) is considered to be extremely difficult once injury occurs. In particular, spinal cord injury (SCI) is a devastating event because patients exhibit permanent impairment of motor and sensory function, and damaged autonomic neurons results in disturbance of bladder and sexual function. Moreover, neuropathic pain after SCI is also a critical issue to make the patients suffer. The annual incidence of traumatic SCI is estimated at 23 cases per million on average, and detailed regional occurrence showed 40 per million in North America and Japan, 16 per million in Western Europe, and 15 per million in Australia [1]. Previously, the SCI was a trauma mainly for younger patients due to high-energy accident, but with the development of aging society, there increases older patients with cervical canal stenosis. At present, surgical intervention and following rehabilitation are the only options for the treatment of SCI. Administration of methylprednisolone has been used, but the consensus of its use has not been reached yet with respect to the efficacy and complications [2, 3].

Recent development of stem cell research is breaking down this situation. A numerous studies demonstrated the efficacy of neural precursor cell (NPC) transplantation for SCI in animal models. Although ethical concerns remained with the use of NPCs harvested from fetus or embryonic stem cells (ESCs), Yamanaka and his colleagues developed induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and opened a hopeful avenue toward the application of iPSC-derived NPCs for regenerative medicine [4, 5]. iPSCs show similar characteristics with ESCs, and are able to generate all three germ layers. Since the cells can be induced from human somatic cells, they have the potential to overcome the ethical issues. Moreover, immune rejection can be prevented by producing the iPSCs from patients themselves as autologous cellular sources. While iPSCs hold enormous attractive potentialities, artificial induction methodology creates alternative problems such as genetic and epigenetic abnormalities and tumorigenicity. It is crucial to resolve these issues for promoting clinical application [6].

The aim of this review article is to present the history of NPC transplantation study for SCI, and current status of cell therapy with the usage of iPSCs. Recently, we developed several methods to overcome the issues of tumorigenicity after transplantation, and introduce these intriguing studies. Currently, we are investigating clinical-grade human iPSC–NPCs, and initiation of the first human clinical study for SCI patients comes around the corner.

Pathophysiology of SCI

The stage of traumatic SCI is divided into primary and secondary phases. At primary phase, mechanical factors such as fracture and/or dislocation damage the spinal cord irreversibly, and neurological deficits occur at and below the level of the cord. This initial mechanical damage and following persistence of compression on the spinal cord initiates a complex array of secondary pathophysiological events, which amplify the primary injury [7, 8].

Within a few minutes after the damage, the spinal cord present severe hemorrhages mainly in gray matter area, and subsequent necrosis at the lesion site. This event initiates occurrence of vasospasm, thrombosis, and spinal cord edema, leading to the status of ischemia. This ischemic status upregulates the cascade of secondary damage processes such as disruption of blood-spinal cord barrier (BSCB), inflammation, oxidative stress, and glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity. These processes are mutually interacted, and eventually lead to axonal degeneration and cell death.

The breakdown of BSCB results from vascular disruption and following degeneration of endothelial cells and astrocytes. Persistent permeability of BSCB triggers invasion of inflammatory mediators into the spinal cord tissue, and these events expand the secondary damage. With respect to neuroinflammation, microglia in the cord tissue is initially activated, and migrates toward the lesion area. The microglia release cytokines, free radicals, and chemokines. These mediators recruit inflammatory cells through the permeability of BSCB, modulate protein expression in neural cells, and lead to neurotoxicity and myelin damage.

Ionic regulation is also broken at secondary phase. With the disruption of neuronal ionic balance by increased influx of sodium and calcium ions, excitatory transmitter glutamate is excessively released from presynaptic neurons. Accumulate of glutamate in synaptic clefts leads to edema, excitotoxicity and apoptotic death of postsynaptic cells.

At chronic stage, substantial tissue loss leads to cavity formation at the site of injury. In addition, glial scar formation, which mainly consists of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans (CSPGs), prevents axonal growth. Suppression of neurite elongation also occurs by myelin-related inhibitory molecules such as Nogo, MAG or OMgp through Rho/ROCK pathway in the injured cord. These statuses at this stage generate unfavorable environment for neural cell survival, resulting in failure of spinal cord regeneration.

Efficacy of NPC transplantation for SCI

As reviewed the aforementioned, orchestrated activation of various cascades leads to cellular loss in SCI. To overcome these phenomenon, exogenous cell transplantation is one of the reasonable strategies to replenish the damaged neural cells in the injured tissue. There are several candidates for the cellular sources such as mesenchymal stromal cells, Schwann cells, and olfactory ensheathing cells. Among these, neural precursor cells (NPCs) from central nervous system is a promising source for the cell replacement therapy in SCI. NPCs have the potential to self-renew with repeated passages and to generate neurons, astrocytes and oligodendrocytes. In adult mammalians, the NPCs exist in subventricular zone and granular cell layer in hippocampus, and they are infinitely maintained in those places. The NPCs can be isolated and cultured under trophic factors, and be expanded with passages [9]. It is, therefore, of great importance to introduce the historical SCI studies and to understand the rationale of efficacy in NPC transplantation before discussing about the iPSC derivatives.

A previous study also showed the existence of NPCs in the spinal cord, and after injury, the cells spread around the lesion site [10]. However, most of the NPCs predominantly differentiated into astrocytes, and did not contribute to functional recovery after SCI. When evaluating the expression of factors that affect NPC differentiation, inflammatory mediators such as interleukin and infiltration of macrophage/microglia were upregulated immediately after SCI, which led to promotion of astrocyte differentiation [11]. However, the inflammatory reaction is decreasing over time by 2 weeks, and we considered subacute phase could be an optimal timing for cell transplantation. Indeed, we harvested NPCs from rat CNS and transplanted into rodent spinal cord tissue 9 days after injury [12]. As expected, the cells at 5 weeks post-transplantation differentiated not only astrocytes, but neurons and oligodendrocytes in the injured spinal cord, and more intriguingly, the neurons extended their processes longitudinally and made synaptic formation. These mechanisms contributed to motor functional recovery.

Another group injected mouse brain-derived NPCs into rat thoracic spinal cord 2 weeks after injury [13]. In combination with growth factors (PDGF-AA, FGF-2, EGF), the NPCs differentiated mainly into glial cells such as astrocytes and oligodendrocytes in vitro. When transplanting the NPCs, they survived up even at chronic stage, and predominantly differentiated into oligodendrocyte lineage cells in vivo. These oligodendrocytes remyelinated host axons, and resulted in locomotor recovery.

NPCs could be generated not only from fetal tissues but also ESCs. In 1999, the efficacy of mouse ESC-derived NPCs was first demonstrated when transplanting the cells into SCI model of rats [14]. The transplanted cells showed tri-lineage differentiation 6 weeks after injury, and promoted improvement of behavior recovery. Our group also focused on the mouse ESCs. We had already established a protocol to generate NPCs with CNS characteristics from mouse ESCs, and succeeded to make primary neurospheres and passaged secondary neurospheres which exhibit neurogenic and gliogenic potentials, respectively [15]. When transplanting these two types of cells into the injured spinal cord of mice, the recipients who underwent graft of gliogenic NPCs showed better functional recovery rather than the neurogenic ones [16]. This recovery could be explained by promoting axonal growth, remyelination and angiogenesis through histological analysis.

To clarify the mechanisms of functional recovery after NPC transplantation, Anderson’s group conducted a unique study [17]. They grafted human CNS-derived NPCs into spinal cord of immunodeficient non-obese diabetic (NOD)- severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mice 9 days after injury, and observed recovery of locomotor performance after the transplantation. However, when administrating diphtheria toxin, which does not kill rodent but human cells, significant deterioration of the recovered motor function was shown in the recipient mice with NPC transplantation.

Since the transplanted cells were histologically confirmed to form synapse with host neurons and myelinate axons before the toxic administration, their results with loss of function indicate that maturation of neurons and oligodendrocytes from transplanted NPCs was fairly essential for motor function recovery after SCI.

Our group demonstrated the importance of remyelination for the treatment of SCI. We harvested NPCs from embryonic striatum in both wild type and shiverer mice, which carry a deletion mutation in the myelin basic protein gene and could not generate myelin in their nervous system [18–20]. We transplanted these two types of cells into the injured spinal cord of mice model, and showed that the grafted NPCs from shiverer mice could differentiate into oligodendrocytes, but did not generate myelination sheath [21]. Although the SCI mice with NPCs from shiverer mice showed locomotor and electrophysiological functional recovery to some extent, the recovery was significantly less than the one by NPCs from wild-type mice. These findings emphasize on the biological significance of myelination by grafted cells, and also highlight one of the mechanisms for functional recovery after NPC treatment in SCI.

As mentioned above, there are several presumable mechanisms for functional recovery after NPC transplantation in SCI [17, 22–26]. First, the NPCs secret trophic factors at the transplanted site to reduce secondary damage. This potential mechanism could explain how the functional restoration occurs shortly after NPC transplantation without full neural maturation of the grafted cells. Second, the transplants play a role as substrates for axonal regeneration and/or differentiate into neuronal cells to reconstruct neural circuit around the lesion site. And finally, the transplanted NPCs differentiate into oligodendrocytes and myelinate host axons to restore axonal saltatory conduction.

iPSCs and its derivative NPCs: a promising source for cell replacement therapy

Based on the expected results of NPC transplantation in SCI animal models, we had already proceeded toward clinical application with the preparations to stock human NPCs from fetal tissues and establish cell banks. However, the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare developed guidelines for clinical research related to human stem cells in 2006, and announced that human fetal tissue and ESCs were prohibited to use in regenerative medicine due to ethical issues [27].

Concurrently with this disappointing news, Yamanaka and his colleagues reported innovative development in 2006. They transfected reprogramming factors (Oct3/4, Sox2, Klf4 and c-Myc) into mouse somatic cells and generated induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) which showed comparable characteristics to ESCs [5]. Then in 2007, they developed human iPSCs with similar methodology to mouse iPSCs [4], and this prominent invention opened up a novel way toward regenerative medicine because this technology can avoid ethical concerns related to human ESCs or fetal tissues. In addition, the iPSCs have the potential to overcome immune rejection after transplantation if the cells could be induced from somatic cells of patients themselves as autologous cellular sources.

For clinical application of iPSCs for CNS injury or diseases, it was critically important to produce NPCs from the iPSCs. Since we had already established methods to generate NPCs from mouse ESCs [15], we succeeded to induce neurospheres from mouse iPSCs by mimicking the ESC methodology [28]. However, the characteristics of generated NPCs varied among the iPSC lines, and some of them showed tumor formation after transplantation. To clarify the differences of iPSC properties, we used 36 lines of iPSCs characterized by (1) tissue origin, (2) presence or absence of drug selection, and (3) presence or absence of c-Myc transgene whose reactivation was associated with tumor formation [28, 29]. Among these, we found that tissue origin substantially affected the tumorigenicity. The iPSCs–NPCs which were generated from mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) showed no undifferentiated cells in proliferated neurospheres in vitro. When transplanting these cells into a brain of NOD/SCID mice, the propensity for teratoma formation was quite low and comparable to those from ESCs. Moreover, no tumor formation was observed in the iPSC–NPCs derived from gastric epithelial cells. In contrast, the iPSC–NPCs from adult tail-tip fibroblasts (TTF) showed significant resistance to differentiation, resulting in residual Nanog+ undifferentiated cells in the neurospheres. After transplantation of the cells, teratoma formation was observed at higher frequency compared with the other cell origins. The NPCs from adult hepatocyte-derived mouse iPSCs showed intermediate propensities between MEFs and TTFs. These characteristic differences among iPSC lines could be attributed to the expression profiles of the different remaining genes in the original somatic cells. A recent study demonstrated that adult-derived iPSCs carried more mitochondrial DNA mutations than those from younger-aged sources, resulting in loss of metabolic function [30]. These age-related genetic alteration might affect the properties of iPSCs.

According to the results of mouse iPSC characterization described above, we determined MEF-derived iPSCs as a safe cellular source, and evaluated its efficacy for cell transplantation therapy in SCI [31]. We induced contusive injury model in mice, and transplanted the safe iPSC–NPCs which were derived from MEFs at subacute phase. The grafted NPCs showed differentiation into three neuronal lineages without tumor formation. In particular, the differentiated oligodendrocytes enhanced remyelination for host neuronal axons, and induced neurite regrowth of 5-HT+ serotonergic fibers around the lesion area. These mechanisms contributed to locomotor functional recovery, which was quite similar to regenerative potential in NPCs derived from fetal CNS or mouse ESCs. In contrast to the MEF–iPSCs, we also transplanted TTF–iPSC-derived NPCs, which was pre-evaluated as unsafe cell lines, and observed tumorigenesis and loss of motor function after preliminary functional recovery. Thus, iPSC–NPCs have the great potential to recover the injured spinal cord both histologically and functionally, while it was essential to evaluate the cell characteristics including genomic stability or tumorigenicity and to select safe clones before transplantation.

With respect to the methods for transfection in iPSCs, retroviral infection was initially used. However, there was a risk for tumorigenicity since the retrovirus has a property to be inserted into host genome, and transfected reprogramming genes or oncogenes have the potential to be activated. Therefore, it is important to develop integration-free iPSCs to secure the safety issue. Nagy’s group established iPSCs without genomic insertion by piggyback transposon system which enables the induction of pluripotency with reprogramming factors on a single vector [32]. After activating and stabilizing the pluripotent status in the transfected somatic cells, the transgene cassette could be seamlessly excised. With this system, Fehlings group succeeded to establish a culture protocol to generate NPCs from mouse iPSCs, and transplanted them into thoracic SCI at subacute phase [33, 34]. The transplanted cells survived without tumor formation, differentiated into mature oligodendrocytes with remyelination capacity and contributed to recovery of normal nodal architecture necessary for saltatory conduction. Interestingly, they also generated iPSCs from shiverer MEF, and grafted NPCs derived from them into the injured tissue. Similar to our results with NPCs from embryonic brain striatum in shiverer mice [21], the iPSC–NPCs from shiverer MEF showed poor remyelination capability and action potential conduction after transplantation. As a result, better locomotor recovery was not observed compared to a vehicle-treated control group [34]. Again, these results suggest that remyelination after SCI plays a crucial role for behavior improvement.

Efficacy of human iPSC-derived NPCs for SCI treatment

Effectiveness of human iPSCs can be directly connected to realization of clinical application for SCI treatment. In 2011, we transplanted human iPSC–NPCs into SCI model of NOD/SCID mice, and showed that the transplanted cells mainly differentiated into neurons which made synaptic connection with host axons [35]. The human iPSC–NPCs enhanced axonal regrowth, angiogenesis, and preservation of whole spinal cord and white matter area. These beneficial effects contributed to locomotor functional recovery with improvement of electrophysiological motor-evoked potential. Importantly, the NPCs did not make tumor for 3.5 months after transplantation. Although longer observational duration was essential to validate the non-tumorigenic properties, this was the first study to demonstrate the usefulness and safety of human iPSCs for therapeutic strategy in SCI. To investigate the efficacy of human iPSCs in primates, we next induced SCI models of common marmosets, and transplanted human iPSC–NPCs at subacute phase [36]. Again, the transplanted cells predominantly differentiated into neurons around the lesion site without tumorigenicity, and promoted axonal regrowth and angiogenesis, and preserved myelination area. These positive mechanisms resulted in significant functional recovery in the NPC recipients compared to a vehicle control group.

The efficacy of human iPSC–NPCs has been also demonstrated in laboratories worldwide. Tuszynski’s group had initially conducted transplantation of human NPCs derived from embryonic spinal cord into immunodeficient rats 2 weeks after spinal cord transection [37]. They injected a growth factor cocktail simultaneously to enhance the cell viability. As a result, the grafted cells that differentiated into neurons elongated their processes, intruded into the spinal cord across the lesion site, and formed synaptic connections with host axons. They observed functional recovery, which deteriorated after retransection. Based on this study, they next used human iPSC–NPCs for transplantation therapy [38]. They induced a cervical hemisection model of immunodeficient rats, and transplanted the human iPSC–NPCs. Similar to the results of NPCs from embryonic tissue, the grafted cells showed neurite elongation with very long distances 12 weeks after injury. The elongated axons penetrated into host gray matter and made synaptic formation between the neurons. Host supraspinal motor axons also penetrated human grafts and formed synapses. These findings indicate that even in the post-injury environment with neurite growth inhibition, human iPSC–NPCs have the potential to elongate robust axons. In spite of this fruitful phenomenon, the rats with human NPCs did not show functional recovery [38]. To gain the motor recovery, it could be of great importance to guide the elongated axons toward appropriate targets and to make functional neural circuits, by rehabilitation for example [39, 40].

Jendelova’s group compared efficacy of human iPSC–NPC transplantation into SCI with other types of cells such as bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and spinal fetal cell-derived NPCs [41]. Among these cells, the iPSC–NPCs provided the most beneficial effect to preserve host tissue, reduce glial scar, increase axonal sprouting, and promote motor functional recovery. In contrast to very short survival of MSCs, the transplanted NPCs survived for 2 months, and these results could contribute to better histological and functional improvement.

Nakashima’s group established a protocol to generate neuroepithelial-like stem (NES) cells from human iPSCs, which exhibited continuous expandability and generated mature functional neurons [42]. They grafted the NES cells into the spinal cord of NOD/SCID mice 7 days after injury, and observed predominantly neuronal differentiation around the lesion site at 10 weeks post-injury. Although the transplanted NES cells did not enhance axonal regeneration of corticospinal tract, they reconstructed the tract by forming synaptic connections and integrating neuronal circuits. These results led to recovery of motor function. Interestingly, they administered diphtheria toxin to ablate the human grafts 7 weeks after injury and showed sudden deterioration of improved locomotor function. These results with loss of function revealed the significance of neuronal activity enhanced by the transplanted cells.

Hwang’s group uniquely induced human iPSCs from discs because the dissected discs can be easily acquired during surgery for SCI and induced disc-derived iPSC–NPCs can be useful for subsequent cell transplantation therapy [43]. Reprogramming factors were transfected in the dissected discs, and generated human iPSCs showed similar characteristics with human ESCs in gene and marker expressions, and methylation patterns. The disc-derived iPSCs were differentiated into NPCs via embryoid body-based method, and the NPCs mainly differentiated into neurons with functional activity electrophysiologically. The transplanted NPCs at subacute phase showed neuronal differentiation without tumor formation, and contributed to motor functional recovery in SCI model of mice.

On the assumption of allogenic cell transplantation in the actual clinical setting, immunological issues cannot be avoided, and immunosuppressant drugs should be considered. Romanyuk et al. conducted transplantation of human iPSC–NPCs into SCI model of wild-type rats with the use of various immunosuppressant medications such as cyclosporin, methylprednisolone, and azathioprine sodium [44]. The grafted cells survived, differentiated into tri-lineage neural cells, preserved spinal cord tissue, and secreted neurotrophic factors 8 weeks post-transplantation. At 17 weeks after transplantation, the NPCs underwent maturation to become interneurons, motoneurons, and dopaminergic and serotoninergic neurons. This study indicates that the transplanted allogenic human iPSC–NPCs could survive and exert beneficial effects with maturation if the lesion site is under immunosuppressive environment. In contrast, another group only used tacrolimus as an immunosuppressive medication for human iPSC–NPCs transplantation into SCI model of wild-type mice, and showed negative results with poor survival rate of grafted cells and no better functional recovery [45]. For the aim of clinical application, it is of great importance to clarify the association of grafted NPCs with immunoreaction and to optimize the administration methods of immunosuppressant drugs.

One of the issues surrounding SCI research field is that most of the studies were conducted using thoracic model of injury. The established preclinical grading system recommends using cervical model of SCI because actual clinical situation presents more than 60% of patients with cervical SCI [46, 47]. Anatomically, motor function of upper limbs is segmentally divided in the cervical spinal cord, and it would be quite beneficial for functional and quality-of-life restoration even if the transplanted NPCs repair only singular cervical cord segment [48]. Recently, several studies performed transplantation of human iPSC-derived neural cells into cervical SCI models [36, 38, 49–51], and the accumulation of evidence from these clinically relevant studies is further needed to bridge the knowledge gap.

Safety issue and its resolution for human iPSC–NPCs transplantation

Similar to the human NPCs from fetal tissues or ESCs, several studies introduced above also demonstrated positive impact of human iPSC–NPCs on histological and neurological recovery in SCI. However, if we make a wrong choice for iPSC lines, it leads to a problematic situation such as tumorigenicity.

Our group succeeded in presenting functional recovery after SCI with a human iPSC clone by transducing reprogramming factors Oct3/4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc (201B7) [35]. We also used another iPSC line from the same adult human dermal fibroblasts, but induced only three factors such as Oct4, Sox2, and Klf4 (253G1) [52, 53]. The grafted 253G1-derived NPCs survived and showed tri-lineage neural differentiation in the injured spinal cord of NOD/SCID mice 47 days post-transplantation. Although motor function was improved during the duration, it started to decline afterwards and continued over time. This deterioration of the recovered function was explained by the occurrence of tumor formation from the transplanted iPSC–NPCs. When examining the propensities of formed tumor, they consisted of undifferentiated Nestin+ cells, but not Nanog+ pluripotent cells. The tumor presented activation of transgene Oct4, which is known to express in human gliomas and is associated with tumor formation. Transcriptome analysis showed high expression of genes related to epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT), which has a role for tumor invasion and progression. In addition, canonical pathway analysis revealed activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway after transplantation, which also played a crucial role in tumor formation. Although reactivation of c-Myc transgene was considered to have association with tumor development, it was a surprising result in this study since the transfected 253G1 iPSC line did not receive the c-Myc transgene. Instead, incomplete reprogramming for iPSC generation could result in genomic instability and tumor formation.

As a provision of tumorigenicity after cell transplantation, we reported a unique treatment with immunosuppressant medication [54]. Again, we transplanted tumorigenic 253G1-derived NPCs into the spinal cord of immunocompetent wild-type mice, and observed tumor development with worsened motor function if used immunosuppressant drug such as FK506 and anti-CD4 mAb. However, the grafted cells could not survive in the spinal cord without the medications, and more interestingly, when immunosuppressants were terminated en route in mice with tumors, the formed mass was completely rejected, and deteriorated hind-limb motor function was recovered. Histologically, infiltration of lymphocytes and microglia was observed during the tumor rejection, leading to apoptosis of iPSC–NPC-derived tumorigenic cells. Taken together, this on–off system of immunosuppressants could be one of the useful tools to control the tumor formation after iPSC–NPC transplantation.

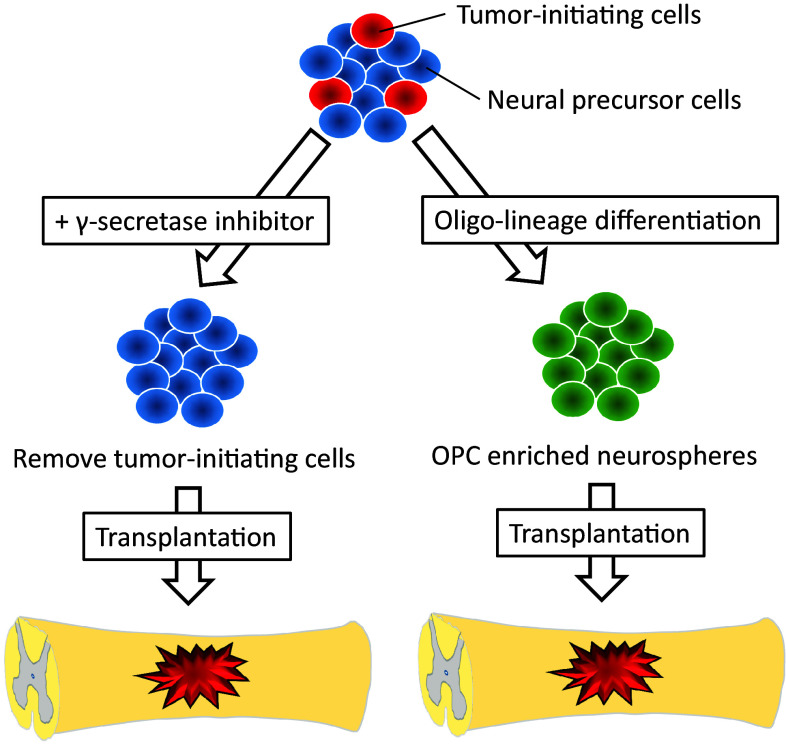

As another method to decrease the risk for tumorigenicity, we pretreated the tumorigenic human iPSC-derived NPCs by a γ-secretase inhibitor (GSI) before transplantation into the injured spinal cord of NOD/SCID mice [55]. The status of undifferentiated NPCs are maintained by Notch signaling pathway, and inhibition of this signaling promotes NPCs for more maturation and neuronal differentiation. In our study, the 253G1 human iPSC–NPCs treated with GSI for 1 day showed neuronal differentiation, reduction of cell division and proliferation, and suppression of EMT-related gene expression. When transplanted the cells, they differentiated mainly into mature neurons around the lesion site, and did not make tumor even for a long-term follow-up. On the other hand, non-GSI-treated NPCs formed tumor with declining motor function. Thus, the pretreatment of GSI could eliminate tumor-initiating cells in the human iPSC–NPCs, and have the potential to overcome the safety issue related to tumorigenicity after cell transplantation (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Strategy to reduce a risk for tumorigenicity after transplantation. OPC oligodendrocyte progenitor cell

Previously, efficacy of oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs) has been demonstrated as a cellular source for transplantation therapy in SCI. Keirstead and his colleagues showed that the grafted ESC-derived human OPCs at subacute phase remyelinated host axons without tumor development and promoted locomotor recovery [23]. Therefore, more committed differentiating status from undifferentiated NPCs have the capability of less tumorigenicity by reducing tumor-initiating cells. Generally, frequency of oligodendrogenic differentiation is quite limited in NPCs. However, this specific differentiation could be facilitated and enriched using factors for caudalization (retinoic acid) and ventralization (Sonic hedgehog) along developmental neural axis [56]. Our group succeeded in establishing OPCs-enriched NPCs from human iPSCs [57], and transplanted the cells into SCI model of NOD/SCID mice at subacute phase [58] (Fig. 1). The grafted cells differentiated into oligodendrocytes at around 40%, which was a significant enhancement of oligo-lineage differentiation compared to NPCs (around 3% [35]). The grafts promoted remyelination and axonal growth with synapse formation, resulting in functional and electrophysiological recovery. Similar results were observed from a study by another group, which established culture protocol to generate OPCs from human iPSCs [59]. The OPCs were transplanted into rat spinal cord 24 h after injury, and more than 70% of the grafts differentiated into mature oligodendrocytes around lesion site without tumorigenicty. The cells protected host axons by remyelination, and reduced cavity and glial scar area, leading to functional recovery 3 months after SCI. Taken together, these results indicate that iPSC-derived OPCs also have the potential to recovery of myelination and neurological function similar to ESC-derivatives, and can overcome the tumorigenic problem by more committed differentiation from undifferentiated NPCs.

Clinical study with human iPSC–NPCs

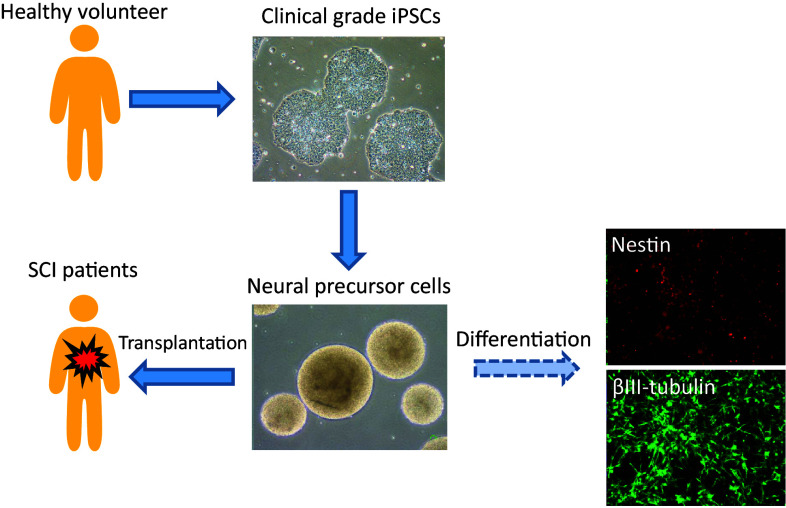

Based on the results of effectiveness in the transplantation therapy, we are now preparing for clinical study with the use of human iPSC–NPCs for patients with SCI. At first, we tried to harvest somatic cells for generating iPSCs from patients themselves, for the aim of autologous cellular transplantation. However, since it takes approximately 6 months to generate iPSCs and produce NPCs, it is impossible to transplant autologous cells within the suitable time window at subacute phase (2–4 weeks after SCI) [60]. Moreover, each iPSCs and its derivative NPCs should be strictly examined on their characteristics and quality including tumorigenicity. Accordingly, large amount of costs would be mandatory. Therefore, it is realistic to conduct allogenic transplantation by establishing a cell bank and stock human iPSC–NPCs which have already been evaluated [27] (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Strategy for iPSC-derived NPC transplantation in SCI patients. CiRA at Kyoto University has already provided clinical grade human iPSCs. We have established differentiation protocol into NPCs and its derivatives. Now we conduct detailed analysis for these cells to secure the efficacy and safety

For clinical application, we have collaborated with the Center for iPS Cell Research and Application (CiRA) at Kyoto University, which establishes clinical-grade integration-free human iPSC lines. We have already received several lines, and started to conduct analyses, especially focusing on their efficacy and safety as therapeutic cell transplantation (Table 1). To date, human iPSCs are mainly established from peripheral or cord blood cells due to easy accessibility and sufficient amount of samples. In detail, we analyze expression of pluripotent and neural markers at gene levels, intracellular domain, and cell surface in iPSC–NPCs. In addition, we examine karyotype, copy number variant, and sterility. To investigate the characteristics of the NPCs, we will examine survival rate, proliferation capability, differentiation and self-renewal potential. For the analysis of tumorigenicity, we transplant the iPSC–NPCs into CNS of immunodeficient animals, and observe them for more than a year. After establishing these screening protocols, we will start phase I-IIa clinical trial for subacute SCI patients to transplant iPSC–NPCs whose quality is guaranteed. Validation of iPSC–NPC transplantation at subacute phase possesses the potential to lead to expand of graft indication for chronic SCI and stroke.

Table 1.

Items of quality management for clinical grade iPSC-derived NPCs

| General characterization | Cell morphology |

| Cell number | |

| Survival rate | |

| Cell proliferation | |

| Cell cycle | |

| Marker expression analysis | Genomic marker |

| Protein marker | |

| Cell surface marker | |

| Genomic analysis | Chromosome/Karyotypte |

| Human Leucocyte Antigen | |

| Copy number variant | |

| Methylation | |

| Functional analysis | Differentiation |

| Neuronal conduction | |

| Secretion of trophic factors | |

| Safety analysis | Sterility |

| Virus test | |

| Tumorigenicity after graft |

With respect to safety issue, our group made new insights into the histological pattern of iPSC–NPCs to distinguish the malignant transformations of transplants in vivo [61]. In that study, transplanted non-carcinogenic iPSC–NSPCs produced differentiation patterns resembling those in embryonic CNS development, and genomic instability of iPSCs correlated with increased proliferation of transplants. According to these results, we established a large database to classify the histological characteristics for the transplanted NPCs (http://www.skip.med.keio.ac.jp/iPSC-NSPC/). We think this database is quite useful to evaluate the safety for transplanting iPSC–NPCs at a stage prior to clinical application for SCI.

To promote regeneration at chronic phase of SCI

To date, transplantation of NPCs has been conducted at subacute phase in most studies. However, most patients with SCI are at chronic stage, and to fill the knowledge gap, future study should more focus on the investigation of pathology and therapeutic development in SCI at this phase. For example, Keirstead’ group established a protocol to enrich OPCs from human ESCs, and transplanted them into rat SCI not only at subacute phase but at chronic phase (10 months after injury) [23]. Their results showed that the transplanted cells survived around the lesion site, but failed to remyelinate host axons and contribute to locomotor functional recovery at the chronic stage. In fact, pathological condition at chronic human SCI presented myelinated host axons by endogenous Schwann cells [62], and this internal repair mechanism potentially hinder the remyelination by exogenous OPCs due to quite limited space.

To investigate the unfavorable cues for the transplanted cells, we grafted mouse NPCs into the injured spinal cord at subacute and chronic phase, and compared microenvironment of the recipients and properties of transplanted NPCs [25]. Although there was no significant differences in the expression levels of genes associated with inflammatory cytokines or growth factors, the gene expression related to macrophage/microglia was upregulated at subacute phase compared to chronic phase. Intriguingly, the expression levels of arginase-1, which associated with anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages, were also higher at subacute stage. With respect to the characteristics of transplanted NPCs, the cells showed similar trend on survival rate and differentiation patterns at both phases, whereas at chronic phase, the location of the grafts was quite limited at lesion epicenter only and remyelination or neurite outgrowth was not enhanced compared to subacute phase. To analyze the transplanted NPCs at molecular levels, another group harvested the NPC intraspinally grafted at acute, subacute, and chronic phases with flow-cytometry, and performed transcriptome analysis for these cells [24, 63]. Interestingly, the grafts even a few months after injury showed strong capacity to differentiate into neural cells, and also retained secretory function of growth factors and regenerative molecules. However, the locomotor function was not recovered with the transplantation at chronic phase. Taken these chronic studies together, the NPCs transplanted even at chronic phase have the potential to survive and differentiate into neural cells at the injured spinal cord, but the cells cannot exert the potential for their own maturation such as axonal regeneration and remyelination. Therefore, to enhance the potential of transplanted NPCs and recover the locomotor function, it is substantially important to modulate the microenvironment at chronic phase by reducing the glial scar and altering inflammatory reactions. For this purpose, combinatory therapy could be an appropriate strategy with the use of drug administration and rehabilitation, in addition to NPC transplantation.

Recently, our group examined the efficacy of NPC transplantation at chronic stage with a combination of rehabilitation [39]. After transplantation of mouse CNS-derived NPCs 49 days after SCI, one of the groups started treadmill exercise for 8 weeks. On behavior analysis, this group showed significant motor recovery at final follow-up compared to the group without NPC transplantation nor exercise. Histologically, grafted cells differentiated into neurons in combinatory therapeutic group compared to the group only with transplantation. In addition, increase of serotonergic neurons and neurite regeneration was observed in the combination group, and excitatory and inhibitory control for coordinative gait was also upregulated in lumbar enlargement where central pattern generator (CPG) elements were distributed. Thus, the treadmill exercise promoted neuronal differentiation, regeneration and maturation of neural circuits at CPG, and beneficial functional recovery.

CSPGs are major components in extracellular matrix of CNS, and after injury, the CSPGs are produced by reactive astrocytes and prevail in glial scar [64]. The CSPGs consist of a core protein with glycosaminoglycans (GAG), which play a role to inhibit axonal growth and sprouting [64, 65]. The CSPGs bind to receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase σ at growth cone and upregulate phosphatase activities, leading to restriction of regenerative neurite outgrowth [66]. In the strategy for spinal cord regeneration, removal of CSPGs, but not ablation of reactive astrocytes, is ideal because the astrocytes play not only detrimental role to inhibit axonal regeneration but beneficial role to prevent the intrusion of inflammatory cells into the spinal cord [67, 68].

Chondroitinase ABC (C-ABC) is a bacterial enzyme which detach the GAG from CSPG protein, and this degradation allows neural axons to grow in vitro [64, 69]. A previous study showed that acute stage administration of C-ABC contributed to regeneration of ascending sensory projections and descending corticospinal tracts, and resulted in recovery of locomotor and proprioceptive behavior in rodent models of SCI [70]. The C-ABC treatment also promoted robust sprouting of descending corticospinal and serotonergic projections [71]. Moreover, the C-ABC exerts neuroprotective efficacy by ameliorating atrophic degenerative changes in neuronal somata of the damaged spinal cord [72]. Thus, this enzyme plays beneficial roles for SCI to promote (1) axonal regeneration, (2) neural sprouting and (3) neuroprotection [64]. Karimi-Abdolrezaee et al. clarified another mechanism of functional improvement in C-ABC treatment with growth factor infusion (EGF, bFGF, and PDGF-AA) [73]. This intervention promoted proliferation of endogenous NPCs and their differentiation into mature oligodendrocytes, vascular formation and suppressed inflammatory reaction. Our group extended their results by examining the efficacy of C-ABC at chronic stage of SCI, and revealed that in combination with treadmill exercise, the treated rats histologically showed significant extension of serotonergic and regenerating neurite fibers, resulting in motor recovery [74].

Next question is how about the efficacy of C-ABC treatment with NPC transplantation. Our group induced rat SCI model, and infused C-ABC with transplantation of rat CNS-derived NPCs 1 week after injury [75]. Histological results demonstrated that the amount of CSPG was reduced in the animals with C-ABC, and regenerative neurite outgrowth was significantly enhanced in the injured spinal cord. In a study at chronic phase, another group administered C-ABC 7 weeks after SCI in a rat model, and transplanted CNS-derived mouse NPCs 1 week after the drug treatment [76]. They found that cell survival was enhanced with predominant differentiation of oligodendrocytes, and the cells promoted increase of corticospinal tract and serotonergic neurons. These mechanisms contributed to motor functional recovery without allodynia. Taken together, the results at chronic phase of SCI suggest that regenerative capacity is preserved and exerted at the cord if suitable treatment is performed.

Conclusions

Recent iPSC technology has rapidly advanced in basic research field, and clinical application for these cells is coming around the corner. However, thorough examination for its efficacy and safety should be conducted cautiously. Moreover, it is imperative to clarify pathological condition of injured spinal cord at chronic stage, and establish effective treatment for this challenging condition. Further study should be necessary to achieve beneficial effects for patients suffering from SCI.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the help of Drs. Masaya Nakamura, RyoYamaguchi, Munehisa Shinozaki, Keiko Sugai, Kota Kojima, who all members of the spinal cord research team in the Department of Physiology and Orthopaedic Surgery. This work was supported by Research Center Network for Realization of Regenerative Medicine the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) (to H.O.). H.O. is a founding scientist of SanBio Co. Ltd and K Pharma Inc. N.N. has no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Lee BB, Cripps RA, Fitzharris M, Wing PC. The global map for traumatic spinal cord injury epidemiology: update 2011, global incidence rate. Spinal Cord. 2014;52(2):110–116. doi: 10.1038/sc.2012.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fehlings MG, Wilson JR, Cho N. Methylprednisolone for the treatment of acute spinal cord injury: counterpoint. Neurosurgery. 2014;61(Suppl 1):36–42. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000000412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hurlbert RJ. Methylprednisolone for the treatment of acute spinal cord injury: point. Neurosurgery. 2014;61(Suppl 1):32–35. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000000393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M, Ichisaka T, Tomoda K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131(5):861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126(4):663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Okano H, Nakamura M, Yoshida K, Okada Y, Tsuji O, Nori S, Ikeda E, Yamanaka S, Miura K. Steps toward safe cell therapy using induced pluripotent stem cells. Circ Res. 2013;112(3):523–533. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.256149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tator CH, Fehlings MG. Review of the secondary injury theory of acute spinal cord trauma with emphasis on vascular mechanisms. J Neurosurg. 1991;75(1):15–26. doi: 10.3171/jns.1991.75.1.0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson JR, Forgione N, Fehlings MG. Emerging therapies for acute traumatic spinal cord injury. CMAJ. 2013;185(6):485–492. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.121206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reynolds BA, Tetzlaff W, Weiss S. A multipotent EGF-responsive striatal embryonic progenitor cell produces neurons and astrocytes. J Neurosci. 1992;12(11):4565–4574. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-11-04565.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frisen J, Johansson CB, Torok C, Risling M, Lendahl U. Rapid, widespread, and longlasting induction of nestin contributes to the generation of glial scar tissue after CNS injury. J Cell Biol. 1995;131(2):453–464. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.2.453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakamura M, Houghtling RA, MacArthur L, Bayer BM, Bregman BS. Differences in cytokine gene expression profile between acute and secondary injury in adult rat spinal cord. Exp Neurol. 2003;184(1):313–325. doi: 10.1016/S0014-4886(03)00361-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ogawa Y, Sawamoto K, Miyata T, Miyao S, Watanabe M, Nakamura M, Bregman BS, Koike M, Uchiyama Y, Toyama Y, Okano H. Transplantation of in vitro-expanded fetal neural progenitor cells results in neurogenesis and functional recovery after spinal cord contusion injury in adult rats. J Neurosci Res. 2002;69(6):925–933. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karimi-Abdolrezaee S, Eftekharpour E, Wang J, Morshead CM, Fehlings MG. Delayed transplantation of adult neural precursor cells promotes remyelination and functional neurological recovery after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2006;26(13):3377–3389. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4184-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McDonald JW, Liu XZ, Qu Y, Liu S, Mickey SK, Turetsky D, Gottlieb DI, Choi DW. Transplanted embryonic stem cells survive, differentiate and promote recovery in injured rat spinal cord. Nat Med. 1999;5(12):1410–1412. doi: 10.1038/70986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okada Y, Matsumoto A, Shimazaki T, Enoki R, Koizumi A, Ishii S, Itoyama Y, Sobue G, Okano H. Spatiotemporal recapitulation of central nervous system development by murine embryonic stem cell-derived neural stem/progenitor cells. Stem Cells. 2008;26(12):3086–3098. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumagai G, Okada Y, Yamane J, Nagoshi N, Kitamura K, Mukaino M, Tsuji O, Fujiyoshi K, Katoh H, Okada S, Shibata S, Matsuzaki Y, Toh S, Toyama Y, Nakamura M, Okano H. Roles of ES cell-derived gliogenic neural stem/progenitor cells in functional recovery after spinal cord injury. PloS One. 2009;4(11):e7706. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cummings BJ, Uchida N, Tamaki SJ, Salazar DL, Hooshmand M, Summers R, Gage FH, Anderson AJ. Human neural stem cells differentiate and promote locomotor recovery in spinal cord-injured mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(39):14069–14074. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507063102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kimura M, Inoko H, Katsuki M, Ando A, Sato T, Hirose T, Takashima H, Inayama S, Okano H, Takamatsu K, et al. Molecular genetic analysis of myelin-deficient mice: shiverer mutant mice show deletion in gene(s) coding for myelin basic protein. J Neurochem. 1985;44(3):692–696. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1985.tb12870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mikoshiba K, Okano H, Tamura T, Ikenaka K. Structure and function of myelin protein genes. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1991;14:201–217. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.14.030191.001221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roach A, Boylan K, Horvath S, Prusiner SB, Hood LE. Characterization of cloned cDNA representing rat myelin basic protein: absence of expression in brain of shiverer mutant mice. Cell. 1983;34(3):799–806. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90536-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yasuda A, Tsuji O, Shibata S, Nori S, Takano M, Kobayashi Y, Takahashi Y, Fujiyoshi K, Hara CM, Miyawaki A, Okano HJ, Toyama Y, Nakamura M, Okano H. Significance of remyelination by neural stem/progenitor cells transplanted into the injured spinal cord. Stem Cells. 2011;29(12):1983–1994. doi: 10.1002/stem.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barnabe-Heider F, Frisen J. Stem cells for spinal cord repair. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3(1):16–24. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keirstead HS, Nistor G, Bernal G, Totoiu M, Cloutier F, Sharp K, Steward O. Human embryonic stem cell-derived oligodendrocyte progenitor cell transplants remyelinate and restore locomotion after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2005;25(19):4694–4705. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0311-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumamaru H, Ohkawa Y, Saiwai H, Yamada H, Kubota K, Kobayakawa K, Akashi K, Okano H, Iwamoto Y, Okada S. Direct isolation and RNA-seq reveal environment-dependent properties of engrafted neural stem/progenitor cells. Nat Commun. 2012;3:1140. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nishimura S, Yasuda A, Iwai H, Takano M, Kobayashi Y, Nori S, Tsuji O, Fujiyoshi K, Ebise H, Toyama Y, Okano H, Nakamura M. Time-dependent changes in the microenvironment of injured spinal cord affects the therapeutic potential of neural stem cell transplantation for spinal cord injury. Mol Brain. 2013;6:3. doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-6-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abematsu M, Tsujimura K, Yamano M, Saito M, Kohno K, Kohyama J, Namihira M, Komiya S, Nakashima K. Neurons derived from transplanted neural stem cells restore disrupted neuronal circuitry in a mouse model of spinal cord injury. J Clin Investig. 2010;120(9):3255–3266. doi: 10.1172/JCI42957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okano H, Yamanaka S. iPS cell technologies: significance and applications to CNS regeneration and disease. Mol Brain. 2014;7:22. doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-7-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miura K, Okada Y, Aoi T, Okada A, Takahashi K, Okita K, Nakagawa M, Koyanagi M, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Ogawa D, Ikeda E, Okano H, Yamanaka S. Variation in the safety of induced pluripotent stem cell lines. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27(8):743–745. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okita K, Ichisaka T, Yamanaka S. Generation of germline-competent induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2007;448(7151):313–317. doi: 10.1038/nature05934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kang E, Wang X, Tippner-Hedges R, Ma H, Folmes CD, Gutierrez NM, Lee Y, Van Dyken C, Ahmed R, Li Y, Koski A, Hayama T, Luo S, Harding CO, Amato P, Jensen J, Battaglia D, Lee D, Wu D, Terzic A, Wolf DP, Huang T, Mitalipov S. Age-related accumulation of somatic mitochondrial DNA mutations in adult-derived human iPSCs. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;18(5):625–636. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsuji O, Miura K, Okada Y, Fujiyoshi K, Mukaino M, Nagoshi N, Kitamura K, Kumagai G, Nishino M, Tomisato S, Higashi H, Nagai T, Katoh H, Kohda K, Matsuzaki Y, Yuzaki M, Ikeda E, Toyama Y, Nakamura M, Yamanaka S, Okano H. Therapeutic potential of appropriately evaluated safe-induced pluripotent stem cells for spinal cord injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(28):12704–12709. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910106107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Woltjen K, Michael IP, Mohseni P, Desai R, Mileikovsky M, Hamalainen R, Cowling R, Wang W, Liu P, Gertsenstein M, Kaji K, Sung HK, Nagy A. piggyBac transposition reprograms fibroblasts to induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2009;458(7239):766–770. doi: 10.1038/nature07863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salewski RP, Buttigieg J, Mitchell RA, van der Kooy D, Nagy A, Fehlings MG. The generation of definitive neural stem cells from PiggyBac transposon-induced pluripotent stem cells can be enhanced by induction of the NOTCH signaling pathway. Stem Cells Dev. 2013;22(3):383–396. doi: 10.1089/scd.2012.0218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Salewski RP, Mitchell RA, Li L, Shen C, Milekovskaia M, Nagy A, Fehlings MG. Transplantation of induced pluripotent stem cell-derived neural stem cells mediate functional recovery following thoracic spinal cord injury through remyelination of axons. Stem Cells Trans Med. 2015;4(7):743–754. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2014-0236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nori S, Okada Y, Yasuda A, Tsuji O, Takahashi Y, Kobayashi Y, Fujiyoshi K, Koike M, Uchiyama Y, Ikeda E, Toyama Y, Yamanaka S, Nakamura M, Okano H. Grafted human-induced pluripotent stem-cell-derived neurospheres promote motor functional recovery after spinal cord injury in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(40):16825–16830. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108077108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kobayashi Y, Okada Y, Itakura G, Iwai H, Nishimura S, Yasuda A, Nori S, Hikishima K, Konomi T, Fujiyoshi K, Tsuji O, Toyama Y, Yamanaka S, Nakamura M, Okano H. Pre-evaluated safe human iPSC-derived neural stem cells promote functional recovery after spinal cord injury in common marmoset without tumorigenicity. PloS One. 2012;7(12):e52787. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lu P, Wang Y, Graham L, McHale K, Gao M, Wu D, Brock J, Blesch A, Rosenzweig ES, Havton LA, Zheng B, Conner JM, Marsala M, Tuszynski MH. Long-distance growth and connectivity of neural stem cells after severe spinal cord injury. Cell. 2012;150(6):1264–1273. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lu P, Woodruff G, Wang Y, Graham L, Hunt M, Wu D, Boehle E, Ahmad R, Poplawski G, Brock J, Goldstein LS, Tuszynski MH. Long-distance axonal growth from human induced pluripotent stem cells after spinal cord injury. Neuron. 2014;83(4):789–796. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tashiro S, Nishimura S, Iwai H, Sugai K, Zhang L, Shinozaki M, Iwanami A, Toyama Y, Liu M, Okano H, Nakamura M. Functional recovery from neural stem/progenitor cell transplantation combined with treadmill training in mice with chronic spinal cord injury. Sci Rep. 2016;6:30898. doi: 10.1038/srep30898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tashiro S, Shinozaki M, Mukaino M, Renault-Mihara F, Toyama Y, Liu M, Nakamura M, Okano H. BDNF induced by treadmill training contributes to the suppression of spasticity and allodynia after spinal cord injury via upregulation of KCC2. Neurorehabilit Neural Repair. 2015;29(7):677–689. doi: 10.1177/1545968314562110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ruzicka J, Machova-Urdzikova L, Gillick J, Amemori T, Romanyuk N, Karova K, Zaviskova K, Dubisova J, Kubinova S, Murali R, Sykova E, Jhanwar-Uniyal M, Jendelova P. A comparative study of three different types of stem cells for treatment of rat spinal cord injury. Cell Transpl. 2017;26(4):585–603. doi: 10.3727/096368916X693671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fujimoto Y, Abematsu M, Falk A, Tsujimura K, Sanosaka T, Juliandi B, Semi K, Namihira M, Komiya S, Smith A, Nakashima K. Treatment of a mouse model of spinal cord injury by transplantation of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived long-term self-renewing neuroepithelial-like stem cells. Stem Cells. 2012;30(6):1163–1173. doi: 10.1002/stem.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oh J, Lee KI, Kim HT, You Y, do Yoon H, Song KY, Cheong E, Ha Y, Hwang DY. Human-induced pluripotent stem cells generated from intervertebral disc cells improve neurologic functions in spinal cord injury. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2015;6:125. doi: 10.1186/s13287-015-0118-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Romanyuk N, Amemori T, Turnovcova K, Prochazka P, Onteniente B, Sykova E, Jendelova P. Beneficial effect of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived neural precursors in spinal cord injury repair. Cell Transpl. 2015;24(9):1781–1797. doi: 10.3727/096368914X684042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pomeshchik Y, Puttonen KA, Kidin I, Ruponen M, Lehtonen S, Malm T, Akesson E, Hovatta O, Koistinaho J. Transplanted human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived neural progenitor cells do not promote functional recovery of pharmacologically immunosuppressed mice with contusion spinal cord injury. Cell Transpl. 2015;24(9):1799–1812. doi: 10.3727/096368914X684079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sekhon LH, Fehlings MG. Epidemiology, demographics, and pathophysiology of acute spinal cord injury. Spine. 2001;26(24 Suppl):S2–S12. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200112151-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kwon BK, Okon EB, Tsai E, Beattie MS, Bresnahan JC, Magnuson DK, Reier PJ, McTigue DM, Popovich PG, Blight AR, Oudega M, Guest JD, Weaver LC, Fehlings MG, Tetzlaff W. A grading system to evaluate objectively the strength of pre-clinical data of acute neuroprotective therapies for clinical translation in spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma. 2011;28(8):1525–1543. doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Doulames VM, Plant GW. Induced pluripotent stem cell therapies for cervical spinal cord injury. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(4):530. doi: 10.3390/ijms17040530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hodgetts SI, Edel M, Harvey AR. The state of play with iPSCs and spinal cord injury models. J Clin Med. 2015;4(1):193–203. doi: 10.3390/jcm4010193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li K, Javed E, Scura D, Hala TJ, Seetharam S, Falnikar A, Richard JP, Chorath A, Maragakis NJ, Wright MC, Lepore AC. Human iPS cell-derived astrocyte transplants preserve respiratory function after spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol. 2015;271:479–492. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2015.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nutt SE, Chang EA, Suhr ST, Schlosser LO, Mondello SE, Moritz CT, Cibelli JB, Horner PJ. Caudalized human iPSC-derived neural progenitor cells produce neurons and glia but fail to restore function in an early chronic spinal cord injury model. Exp Neurol. 2013;248:491–503. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nakagawa M, Koyanagi M, Tanabe K, Takahashi K, Ichisaka T, Aoi T, Okita K, Mochiduki Y, Takizawa N, Yamanaka S. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells without Myc from mouse and human fibroblasts. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26(1):101–106. doi: 10.1038/nbt1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nori S, Okada Y, Nishimura S, Sasaki T, Itakura G, Kobayashi Y, Renault-Mihara F, Shimizu A, Koya I, Yoshida R, Kudoh J, Koike M, Uchiyama Y, Ikeda E, Toyama Y, Nakamura M, Okano H. Long-term safety issues of iPSC-based cell therapy in a spinal cord injury model: oncogenic transformation with epithelial–mesenchymal transition. Stem Cell Rep. 2015;4(3):360–373. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Itakura G, Kobayashi Y, Nishimura S, Iwai H, Takano M, Iwanami A, Toyama Y, Okano H, Nakamura M. Controlling immune rejection is a fail-safe system against potential tumorigenicity after human iPSC-derived neural stem cell transplantation. PloS One. 2015;10(2):e0116413. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Okubo T, Iwanami A, Kohyama J, Itakura G, Kawabata S, Nishiyama Y, Sugai K, Ozaki M, Iida T, Matsubayashi K, Matsumoto M, Nakamura M, Okano H. Pretreatment with a gamma-secretase inhibitor prevents tumor-like overgrowth in human iPSC-derived transplants for spinal cord injury. Stem Cell Rep. 2016;7(4):649–663. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2016.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang S, Bates J, Li X, Schanz S, Chandler-Militello D, Levine C, Maherali N, Studer L, Hochedlinger K, Windrem M, Goldman SA. Human iPSC-derived oligodendrocyte progenitor cells can myelinate and rescue a mouse model of congenital hypomyelination. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12(2):252–264. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Numasawa-Kuroiwa Y, Okada Y, Shibata S, Kishi N, Akamatsu W, Shoji M, Nakanishi A, Oyama M, Osaka H, Inoue K, Takahashi K, Yamanaka S, Kosaki K, Takahashi T, Okano H. Involvement of ER stress in dysmyelination of Pelizaeus–Merzbacher disease with PLP1 missense mutations shown by iPSC-derived oligodendrocytes. Stem Cell Rep. 2014;2(5):648–661. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kawabata S, Takano M, Numasawa-Kuroiwa Y, Itakura G, Kobayashi Y, Nishiyama Y, Sugai K, Nishimura S, Iwai H, Isoda M, Shibata S, Kohyama J, Iwanami A, Toyama Y, Matsumoto M, Nakamura M, Okano H. Grafted human iPS cell-derived oligodendrocyte precursor cells contribute to robust remyelination of demyelinated axons after spinal cord injury. Stem Cell Rep. 2016;6(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.All AH, Gharibani P, Gupta S, Bazley FA, Pashai N, Chou BK, Shah S, Resar LM, Cheng L, Gearhart JD, Kerr CL. Early intervention for spinal cord injury with human induced pluripotent stem cells oligodendrocyte progenitors. PloS One. 2015;10(1):e0116933. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Iwai H, Shimada H, Nishimura S, Kobayashi Y, Itakura G, Hori K, Hikishima K, Ebise H, Negishi N, Shibata S, Habu S, Toyama Y, Nakamura M, Okano H. Allogeneic neural stem/progenitor cells derived from embryonic stem cells promote functional recovery after transplantation into injured spinal cord of nonhuman primates. Stem Cells Trans Med. 2015;4(7):708–719. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2014-0215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sugai K, Fukuzawa R, Shofuda T, Fukusumi H, Kawabata S, Nishiyama Y, Higuchi Y, Kawai K, Isoda M, Kanematsu D, Hashimoto-Tamaoki T, Kohyama J, Iwanami A, Suemizu H, Ikeda E, Matsumoto M, Kanemura Y, Nakamura M, Okano H. Pathological classification of human iPSC-derived neural stem/progenitor cells towards safety assessment of transplantation therapy for CNS diseases. Mol Brain. 2016;9(1):85. doi: 10.1186/s13041-016-0265-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kakulas BA, Kaelan C. The neuropathological foundations for the restorative neurology of spinal cord injury. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2015;129(Suppl 1):S1–S7. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2015.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kumamaru H, Saiwai H, Kubota K, Kobayakawa K, Yokota K, Ohkawa Y, Shiba K, Iwamoto Y, Okada S. Therapeutic activities of engrafted neural stem/precursor cells are not dormant in the chronically injured spinal cord. Stem Cells. 2013;31(8):1535–1547. doi: 10.1002/stem.1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bradbury EJ, Carter LM. Manipulating the glial scar: chondroitinase ABC as a therapy for spinal cord injury. Brain Res Bull. 2011;84(4–5):306–316. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2010.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Silver J, Miller JH. Regeneration beyond the glial scar. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5(2):146–156. doi: 10.1038/nrn1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Coles CH, Shen Y, Tenney AP, Siebold C, Sutton GC, Lu W, Gallagher JT, Jones EY, Flanagan JG, Aricescu AR. Proteoglycan-specific molecular switch for RPTPsigma clustering and neuronal extension. Science. 2011;332(6028):484–488. doi: 10.1126/science.1200840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Okada S, Nakamura M, Katoh H, Miyao T, Shimazaki T, Ishii K, Yamane J, Yoshimura A, Iwamoto Y, Toyama Y, Okano H. Conditional ablation of Stat3 or Socs3 discloses a dual role for reactive astrocytes after spinal cord injury. Nat Med. 2006;12(7):829–834. doi: 10.1038/nm1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Renault-Mihara F, Okada S, Shibata S, Nakamura M, Toyama Y, Okano H. Spinal cord injury: emerging beneficial role of reactive astrocytes’ migration. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40(9):1649–1653. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhao RR, Fawcett JW. Combination treatment with chondroitinase ABC in spinal cord injury–breaking the barrier. Neurosci Bull. 2013;29(4):477–483. doi: 10.1007/s12264-013-1359-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bradbury EJ, Moon LD, Popat RJ, King VR, Bennett GS, Patel PN, Fawcett JW, McMahon SB. Chondroitinase ABC promotes functional recovery after spinal cord injury. Nature. 2002;416(6881):636–640. doi: 10.1038/416636a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Barritt AW, Davies M, Marchand F, Hartley R, Grist J, Yip P, McMahon SB, Bradbury EJ. Chondroitinase ABC promotes sprouting of intact and injured spinal systems after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2006;26(42):10856–10867. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2980-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Carter LM, Starkey ML, Akrimi SF, Davies M, McMahon SB, Bradbury EJ. The yellow fluorescent protein (YFP-H) mouse reveals neuroprotection as a novel mechanism underlying chondroitinase ABC-mediated repair after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2008;28(52):14107–14120. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2217-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Karimi-Abdolrezaee S, Schut D, Wang J, Fehlings MG. Chondroitinase and growth factors enhance activation and oligodendrocyte differentiation of endogenous neural precursor cells after spinal cord injury. PloS One. 2012;7(5):e37589. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shinozaki M, Iwanami A, Fujiyoshi K, Tashiro S, Kitamura K, Shibata S, Fujita H, Nakamura M, Okano H. Combined treatment with chondroitinase ABC and treadmill rehabilitation for chronic severe spinal cord injury in adult rats. Neurosci Res. 2016;113:37–47. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2016.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ikegami T, Nakamura M, Yamane J, Katoh H, Okada S, Iwanami A, Watanabe K, Ishii K, Kato F, Fujita H, Takahashi T, Okano HJ, Toyama Y, Okano H. Chondroitinase ABC combined with neural stem/progenitor cell transplantation enhances graft cell migration and outgrowth of growth-associated protein-43-positive fibers after rat spinal cord injury. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22(12):3036–3046. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Karimi-Abdolrezaee S, Eftekharpour E, Wang J, Schut D, Fehlings MG. Synergistic effects of transplanted adult neural stem/progenitor cells, chondroitinase, and growth factors promote functional repair and plasticity of the chronically injured spinal cord. J Neurosci. 2010;30(5):1657–1676. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3111-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]