Abstract

Nuclear receptors are ligand-activated transcription factors that partake in several biological processes including development, reproduction and metabolism. Over the last decade, evidence has accumulated that group 2, 3 and 4 LIM domain proteins, primarily known for their roles in actin cytoskeleton organization, also partake in gene transcription regulation. They shuttle between the cytoplasm and the nucleus, amongst other as a consequence of triggering cells with ligands of nuclear receptors. LIM domain proteins act as important coregulators of nuclear receptor-mediated gene transcription, in which they can either function as coactivators or corepressors. In establishing interactions with nuclear receptors, the LIM domains are important, yet pleiotropy of LIM domain proteins and nuclear receptors frequently occurs. LIM domain protein-nuclear receptor complexes function in diverse physiological processes. Their association is, however, often linked to diseases including cancer.

Keywords: LIM, Nuclear receptor, Actin cytoskeleton, Coregulator, Transcription

Introduction

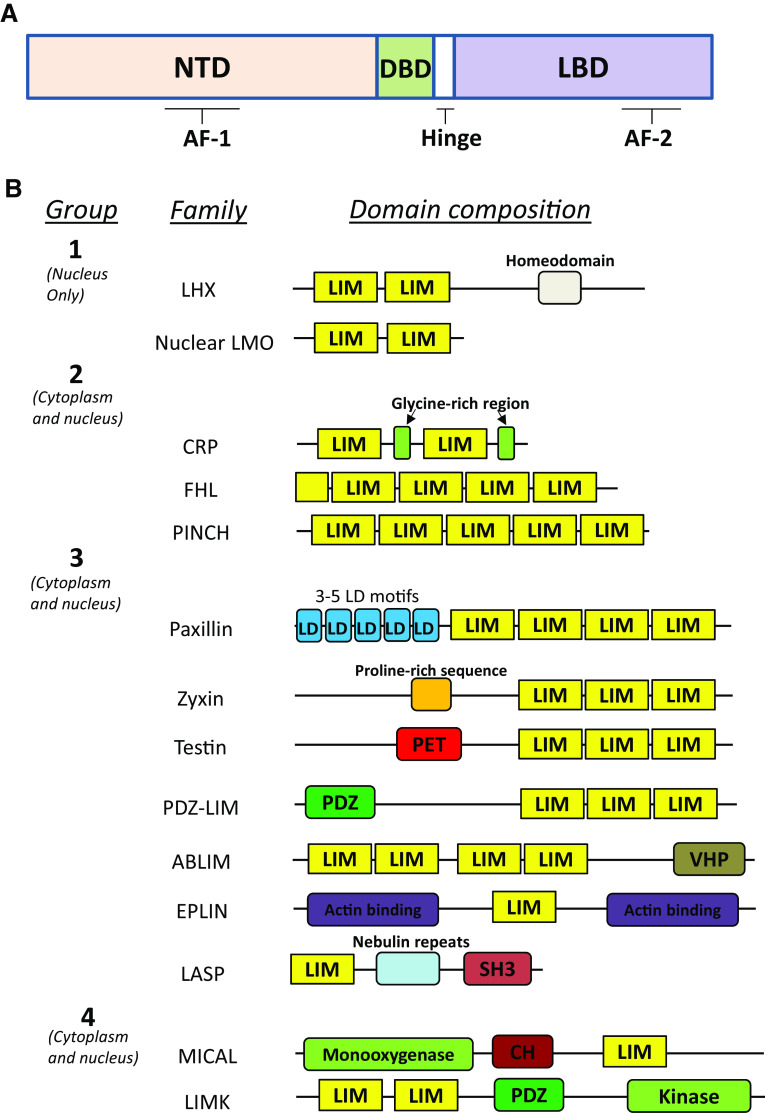

The superfamily of nuclear receptors (NR) is a group of ligand-activated transcription factors that play important roles in metabolism, homeostasis, reproduction and normal development. They are additionally often linked to pathologies such as neurodegenerative and metabolic diseases, inflammation and cancer [1–4]. From a structural point of view, NRs share a common organization (Fig. 1a). They contain a central highly conserved DNA-binding domain (DBD), which is involved in receptor dimerization and binding to hormone-response elements at promoter regions of target genes. Their C-terminal region contains a more moderately conserved ligand-binding domain (LBD), which is also responsible for receptor dimerization [5]. DBD and LBD are linked by a flexible hinge that allows conformational changes of the receptor and that also contains a nuclear localization signal (NLS) [6]. The region N-terminal of the DBD, the N-terminal domain (NTD) is very diverse and contains the receptor activation function (AF-1) region. These regions interact, in a ligand-independent manner, with cofactors and other proteins that are part of the transcription machinery. A second, ligand-dependent receptor activation function region (AF-2) is present within the LBD and can act synergistically with AF-1 [5, 6]. Collectively, these structural properties allow NRs to interact with specific ligands, dimerize and translocate to the nucleus where they bind hormone-response elements at promoter sites, and recruit coregulators of the transcription machinery to regulate gene expression.

Fig. 1.

Structure of nuclear receptors and classification and domain organization of LIM domain proteins. a Schematic representation of a nuclear receptor. Nuclear receptors consist of an N-terminal domain (NTD), and a DNA-binding domain (DBD) and ligand-binding domain (LBD) which are separated by a hinge region. The NTD and the LBD both contain a receptor activation function, AF-1 and AF-2, respectively. b LIM domain proteins are subdivided into four groups. Members of group 1 exclusively reside in the nucleus, whereas group 2, 3 and 4 members can be cytoplasmic or nuclear. For each group, the different families and their general domain composition and organization are displayed. CH calponin homology, LD leucine/aspartate repeat, LIM Lin-11, Isl-1, Mec-3, PDZ postsynaptic density-95, disc large, zona occludens-1, PET Prickle, Espinas, Testin, SH3 Src homology 3, VHP villin head piece. The number of LIM domains in the mammalian PDZ-LIM proteins is 1 or 3, in the testin family it is 2 or 3

Another important class of proteins is LIM domain containing proteins which participate in various biological processes such as gene regulation, cell fate determination and cytoskeleton organization. Similar to NRs, they contribute to pathologies including heart disease, inflammation, metabolic and neurological disorders as well as cancer [7–19]. The name of these proteins is derived from the LIM (Lin-11, Isl-1, Mec-3) domain they share, and of which often more than one copy is present. Some proteins only consist of this type of domain but there are numerous examples of LIM domain proteins that in addition contain otherwise different domains, modules or motifs that codetermine their specific functions (and which is in part used for their classification, see below). LIM domains comprise 50–60 amino acids that build up two zinc fingers [19]. Each zinc finger contains four conserved cysteine or histidine residues (usually CCHC in the first zinc finger and CCC(H/C) in the second) that coordinate Zn2+, which is necessary for maintaining the proper fold, and thus the function of the LIM domain [19]. Unlike zinc fingers in transcription factors, zinc fingers in LIM domains are generally considered as protein–protein interaction units (exceptions are described below).

Over the last decade, evidence for a functional link between NRs and (cytoskeletal) LIM domain proteins has consistently emerged. It has been established that non-genomic rapid steroid hormone actions, such as mediated by glucocorticoids and androgens, include actin cytoskeleton rearrangements [20] and it can be anticipated that these LIM domain proteins are part of this response. However, this review will focus on NR-mediated gene transcription modulated by LIM domain proteins. We first briefly address classification of NRs and LIM domain proteins. Because the presence of LIM domain proteins in the nucleus is a prerequisite for their coregulatory activity, we describe relevant aspects about their shuttling between cytoplasm and nucleus, with special attention to the triggers that are responsible for their nuclear translocation. We next overview the structural requirements for the LIM domain protein–NR interactions in which the LIM domains appear crucial. We summarize the current knowledge on how LIM domain proteins exert their coregulator functions. Finally, we discuss biological processes and disease context of LIM domain protein–NR-mediated gene transcription.

Classification of nuclear receptors and LIM domain proteins

The NRs are subdivided into three major classes based on their modes of action. Class I receptors are tethered in the cytoplasm by heat-shock proteins, and upon ligand binding, they are released from these proteins enabling the receptors to dimerize and translocate to the nucleus where they affect gene transcription [21]. This class comprises the progesterone receptor (PR), oestrogen receptor (ER), glucocorticoid receptor (GR), androgen receptor (AR) and mineralocorticoid receptor (MR). Class II receptors already reside in the nucleus, bound to DNA. They generally are heterodimeric with the retinoid X receptor (RXR) as one of the subunits. Ligand binding leads to recruitment of coregulators and subsequently regulation of gene expression. The retinoic acid receptor (RAR), thyroid hormone receptor (THR), vitamin D receptor (VDR), liver X receptor (LXR) and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) also belong to this second class [5]. Class III members are often referred to as ‘orphan receptors’ since their natural ligands remain to be identified [22]. Their exact mechanism of action is still under investigation, though these receptors are able to operate either as dimers or monomers. This class comprises, among others, the liver receptor homolog 1 (LRH-1), steroidogenic factor 1 (SF-1), testicular receptor 4 (TR4), Nur77 and Nurr1 [22].

LIM domain proteins are subdivided into four groups. This takes into account the domain composition, their arrangement, and additionally considers subcellular localization (Table 1, Fig. 1b). Group 1 consists of nuclear proteins that have two LIM domains. Examples are members of the LMO (LIM domain only) and LHX (LIM homeobox) families; the latter containing a C-terminal tail with a homeodomain. They act as transcription factors or cofactors to regulate tissue-specific gene expression [18]. Their interaction with nuclear receptors has been established [23, 24] and they will not be further discussed in this review. In contrast, groups 2, 3 and 4 LIM domain proteins were mostly identified as cytoplasmic proteins and often associated with the actin cytoskeleton. However, several of these proteins are also capable of shuttling between the cytoplasm and the nucleus where they can be involved in gene transcription [25]. Group 2 members consist of proteins with only LIM domains and no discernible other domains. This group comprises, among others, the CRP (cysteine and glycine-rich protein), FHL (four-and-a-half LIM) and PINCH (particularly interesting new cysteine and histidine-rich protein) families. Apart from their LIM domains, group 3 and group 4 families harbour several other domains. Group 3 have other protein–protein interaction domains or motifs and consist, among others, of the paxillin (including transforming growth factor beta-1-induced transcript 1 protein, further referred to as TGFB1I1), zyxin, testin and LASP families (Table 1, Fig. 1b). Group 4 members combine LIM domains with a catalytic module: MICAL proteins possess a monooxygenase activity, whereas LIM kinases phosphorylate proteins [18].

Table 1.

LIM domain protein families and their members

| Group | Family | Members (alternative name) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | LHX | ISL-1, ISL-2, LHX1, LHX2, LHX3, LHX4, LHX5, LHX6, LHX8, LHX9, LIM homeobox transcription factor 1a, LIM homeobox transcription factor 1b |

| Nuclear LMO | Rhombotin 1 (LMO1), Rhombotin 2 (LMO2), LMO3, LIM domain transcription factor LMO4 | |

| 2 | CRP | CRP1, CRP2, CRP3 |

| FHL | FHL1, FHL2, FHL3, FHL5 (ACT) | |

| PINCH | LIM and senescent cell antigen-like-containing domain protein 1 (PINCH1), LIM and senescent cell antigen-like-containing domain protein 2 (PINCH2) | |

| 3 | Paxillin | Paxillin, leupaxin, transforming growth factor beta-1-induced transcript 1 protein (Hic-5, ARA55) |

| Zyxin | Zyxin, TRIP6, LPP, LIMD1, LIM domain-containing protein ajuba, WTIP, FBLP-1 (Migfilin) | |

| Testin | Testin, LMCD1 (Dyxin), Prickle1, Prickle2, Prickle3, Prickle4 | |

| PDZ-LIM | PDZ and LIM domain protein 1 (CLP-36), PDZ and LIM domain protein 2 (Mystique), PDZ and LIM domain protein 3 (ALP), PDZ and LIM domain protein 4 (RIL), PDZ and LIM domain protein 5 (ENH), PDZ and LIM domain protein 7 (Enigma), LIM domain-binding protein 3 (Cypher) | |

| LASP | LASP-1, NRAP | |

| EPLIN | LIM domain and actin-binding protein 1 (EPLIN) | |

| ABLIM | ABLIM1, ABLIM2, ABLIM3 | |

| Other | LIM domain only protein 7 (LMO7), LIM and calponin homology domains containing protein 1, Zinc finger protein 185 (ZNF185), Sciellin | |

| 4 | LIMK | LIMK-1, LIMK-2 |

| MICAL | [F-actin]-monooxygenase MICAL1, [F-actin]-monooxygenase MICAL2, [F-actin]-monooxygenase MICAL3, MICAL-like protein 1, MICAL-like protein 2 |

ABLIM actin-binding LIM protein, ACT activator of cyclic AMP response element modulator in testis, ALP α-actinin-associated LIM protein, ARA55 androgen receptor-associated protein of 55 kDa, CLP-36 36 kDa C-terminal LIM domain protein, CRP cysteine and glycine-rich protein, ENH enigma homolog, EPLIN epithelial protein lost in neoplasm, FBLP filamin-binding LIM protein, FHL four-and-a-half LIM domain, Hic-5 hydrogen peroxide-inducible clone 5, ISL insulin gene enhancer protein, LASP LIM and SH3 protein, LHX LIM homeobox protein, LIMD1 LIM domain-containing protein, LIMK LIM domain kinase, LMCD1 LIM and cysteine-rich domains protein 1, LMO LIM domain only, LPP Lipoma-preferred partner, MICAL molecule interacting with CasL protein 1, NRAP nebulin-related anchoring protein, PDZ postsynaptic density-95, disc large zona occludens-1, PINCH particularly interesting new cysteine and histidine-rich protein, Prickle prickle-like protein, TRIP6 thyroid receptor interacting protein 6, WTIP wilms tumour 1 interacting protein. (adapted and expanded from Zheng et al., 2007, the MICAL family has been originally classified as group 4 based on the presence of a catalytic module, the evolutionary related MICAL-like proteins do not have this module)

Nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling of LIM domain proteins

The observation that LIM domain proteins operate in the nucleus as coregulators of NR-mediated transcription, in addition to their cytoplasmic cytoskeletal functions, implicates they are capable of shuttling between the cytoplasm and the nucleus. The nuclear location/import/export of the LIM domain proteins, as well as the triggers (including NR ligands) that are responsible for their nuclear translocation, will be addressed in this section although this process is in many cases only poorly understood.

There are several lines of evidence for nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling of LIM domain proteins. For instance, LIM and cysteine-rich domain protein 1 (LMCD1) functions as corepressor of GATA6-mediated transcription, whereas a cancer-associated mutant LMCD1 localizes in the cytoplasm and enhances lamellipodium formation [26, 27]. A related protein: testin, which is traditionally considered as a focal adhesion protein, is also observed in the nucleus in certain cell types [28, 29]. For many of these proteins, including members of the zyxin and paxillin families as well as LIMK-1, PINCH and LASP, [30–40] functional nuclear export signals have been identified. Inhibition of nuclear export by leptomycin B leads to nuclear accumulation of zyxin/paxillin family members demonstrating that their nuclear export is Crm-1-dependent [25]. Conversely, for only a limited number of LIM domain proteins (e.g. LIMK-2, FHL1B), well-defined nuclear localization signals have been recognized [41, 42]. This raises the possibility that LIM domain proteins use other mechanisms to enter the nucleus. A possible scenario is that LIM domain proteins do so by interacting with other proteins that are known to translocate to the nucleus. For instance, PINCH and CRP interact with TGFB1I1 (also a LIM domain protein) which enhances their nuclear localization [43]. The predominant cytoplasmic localization of LIM domain proteins also makes it unlikely the shuttling from the cytoplasm to the nucleus is unregulated, and thus suggests that their nuclear translocation is an active process that requires the correct triggers.

Relevant for this review, translocation of LIM domain proteins to the nucleus upon triggering by NR ligands has been observed. Paxillin and TGFB1I1 colocalize with the AR in the nucleus upon stimulation by AR ligand [44, 45]. An explanation for this observation is that paxillin and TGFB1I1 already interact with the AR in the cytoplasm and consequently enter the nucleus together with this NR, after ligand stimulation. We note, however, that many NRs are constitutively present in the nucleus (e.g. class II receptors) and NR-independent mechanisms for the nuclear translocation of LIM domain proteins upon NR ligand stimulation, must also exist. One example supporting this hypothesis is zyxin translocation to the nucleus after retinoic acid stimulation of the RAR [46]. Whether other LIM domain proteins enter the nucleus upon NR ligand stimulation (alone or together with NR) remains to be investigated. It is, however, clear that translocation of LIM domain proteins to the nucleus can also occur via other stimuli than NR ligands. TGFB1I1 is tethered in focal adhesions via interactions with focal adhesion kinase and protein tyrosine phosphatase PEST. Under oxidative conditions, these interactions are ruptured enabling TGFB1I1 to translocate to the nucleus [47]. Similarly, zyxin dissociates from focal adhesions upon mechanical tension and subsequently translocates to the nucleus [48]. It is possible that these non-NR ligand-mediated nuclear translocation events are still required for NR activity. For instance, FHL2 nuclear translocation is triggered by activation of the Rho-ROCK pathway which leads to transcription of AR-dependent genes [12]. Similarly, calpain-mediated cleavage of filamin also triggers FHL2 nuclear translocation and AR activation [49].

It will be important for the future to map the complexity of triggered translocations of LIM domain proteins, and hence identify mechanisms, NR-dependent and -independent, which allow better understanding the link between these cytosolic LIM domain proteins and NR-mediated gene transcription.

Pleiotropy of LIM domain protein–NR interaction: structural importance of the LIM domains

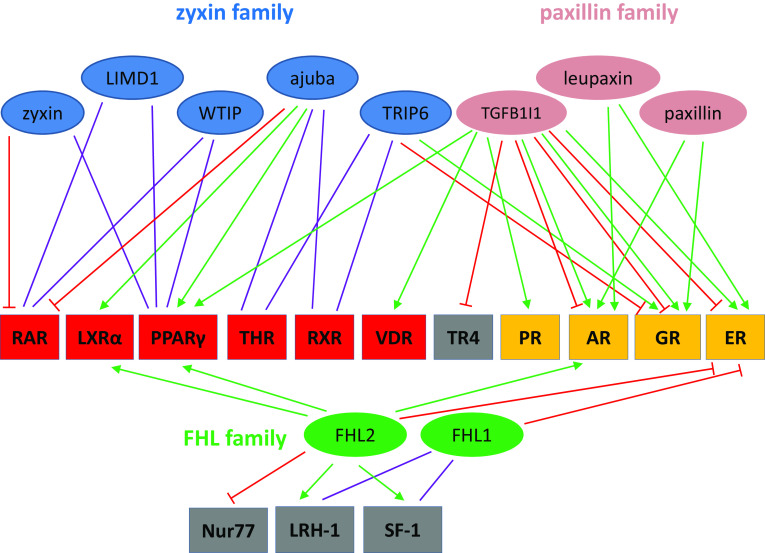

As outlined in the previous section, LIM domain proteins are capable of shuttling between the cytoplasm and the nucleus. Given this nuclear localization, together with the fact that LIM domains are protein–protein scaffolding modules, it comes as no surprise that several of these LIM domain proteins are interaction partners of NRs. The evidence is based on multiple studies exploiting different assays: yeast two-hybrid studies, co-immunoprecipitations and GST pull-down assays. Different LIM domain proteins have been observed to interact with the same NR but certain LIM domain proteins also associate with different NRs, which are illustrated for members of the FHL, zyxin and paxillin families in Fig. 2. A common theme is the importance of the LIM domains in partner interaction. However, the binding region within the NR is more variable and depends on the particular LIM domain protein that interacts with it. Table 2 gives an overview of the LIM domain protein–NR interactions that have been studied so far, the regions or domains involved in these interactions and the coregulatory role of the LIM domain proteins.

Fig. 2.

Pleiotropy of LIM domain protein–NR interactions. Pleiotropy of LIM domain protein–NR interactions is illustrated for members of the zyxin (blue), paxillin (magenta) and FHL (green) families (see also Table 2). Orange boxes indicate class I, red boxes class II and grey boxes class III NRs. Green arrow: interaction and coactivation, red T-shaped line: interaction and corepression, purple line: interaction with uncharacterized effect. For abbreviations of proteins we refer to the legends of Tables 1 and 2

Table 2.

LIM domain protein–NR interactions and LIM domain protein coregulatory functions

| LIM domain protein | NR | LIM domain protein region | NR region | LIM domain protein coregulatory function | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FHL1 | ER | LIM domains | NTD | Corepressor | [55] |

| LRH-1, SF-1 | NI | NI | NI | [53] | |

| FHL2 | AR | LIM domains | AF-2 | Coactivator | [51] |

| LXR | LIM domains | NI | Coactivator | [52] | |

| LRH-1 | LIM domains | DBD, LBD | Coactivator | [53] | |

| SF-1 | LIM domains | LBD | Coactivator | [53] | |

| Nur77 | LIM domains | DBD, NTD | Corepressor | [50] | |

| ER | LIM domains | NTD | Corepressor | [54] | |

| PPARα | No interaction | Coactivator | [85] | ||

| Paxillin | AR | LIM domains | NI | Coactivator | [60] |

| GR | LIM domains | NI | Coactivator | [60] | |

| Leupaxin | AR | LIM3 | LBD | Coactivator | [59] |

| ERα | LIM domains | NTD, DBD | Coactivator | [40] | |

| TGFB1I1 | AR | LIM2, 4 | LBD | Coactivator/corepressor | [68, 82, 88] |

| GRα | LIM3, 4 | Tau-2 region | Coactivator/corepressor | [62, 63] | |

| GRγ | NI | NI | Coactivator/corepressor | [63] | |

| ERα | NI | NI | Coactivator/corepressor | [63] | |

| PPARγ | LIM domains | NI | Coactivator | [64] | |

| TR4 | NI | NI | Corepressor | [67] | |

| VDR | NI | NI | Coactivator | [65] | |

| PR | NI | NI | Coactivator | [66] | |

| Zyxin | RAR | No interaction | Corepressor | [46] | |

| PPARγ | AA 1–42 | NI | NI | [70] | |

| Ajuba | LXRα | LIM domains | LBD, hinge | Coactivator | [75] |

| PPARγ | NTR | DBD | Coactivator | [72] | |

| RAR | NTR, LIM2, 3 | NI | Corepressor | [71] | |

| THRα, RXRγ | NI | NI | NI | [71] | |

| TRIP6 | GR | LIM domains | NI | Coactivator/corepressor | [74] |

| THR, RXR | NI | NI | NI | [73] | |

| LIMK-1 | AR | NI | NI | Coactivator | [87] |

| Nurr1 | LIM, kinase domains | LBD, NTD | Corepressor | [77] | |

| RAR | NI | NI | Corepressor | [86] | |

| LIMD1 | RAR, PPARγ | NI | NI | NI | [71, 72] |

| WTIP | RAR, PPARγ | NI | NI | NI | [71, 72] |

AA amino acid, AR androgen receptor, ER oestrogen receptor, GR glucocorticoid receptor, LRH liver receptor homolog, LXR liver X receptor, NI not investigated, NTR N-terminal region, PPAR peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor, PR progesterone receptor, RAR retinoic acid receptor, RXR retinoid X receptor, SF steroidogenic factor, THR thyroid hormone receptor, TR testicular receptor, VDR vitamin D receptor

A first level of pleiotropy is exemplified by studies on members of the FHL family, belonging to group 2 of LIM domain proteins (Table 2, Fig. 2). FHL2 interacts with the AR and LXR as well as with the orphan receptors Nur77, LRH-1 and SF-1 [49–53]. The latter two receptors also interact with FHL1 [53]. Further pleiotropy within the FHL family is evident from the observation that FHL2 binds ERα and ERβ [54]. Similar observations were made for FHL1 that exerts corepressor function on ER transcription [55].

For the above mentioned NR interactions of FHL2, it has been demonstrated that the LIM domains are required. Differences do, however, exist. For the interaction of FHL2 with AR and LXR, all four LIM domains contribute to complex formation [51, 52], whereas for the FHL2-LRH-1 and FHL2-Nur77 interactions, each single LIM domain is sufficient [50, 53]. Also structural features within the NR, required for the interaction with LIM domain proteins, have been mapped and display common and unique aspects. Illustrating complexity, either DBD, LBD, AF-1 or AF-2 can be involved. For the AR there is evidence that AF-2 is needed for its interaction with FHL2. In contrast, the LBD and DBD domains of LRH-1 are required for interaction with FHL2, whereas for the orphan receptor Nur77 this is the DBD and the N-terminal region [50, 53]. In case of the ER, the AF-1 containing NTD is required to ensure the interaction with both FHL1 and FHL2 [55, 56].

There is not only pleiotropy for NRs within group 2 of LIM domain proteins, but also between groups. Indeed, also LIM domain proteins of group 3 have been shown to bind to AR or ER. However, other NRs also come into play. For group 3 members, we will consider the paxillin and zyxin families because these have been best studied in the context of NRs (Table 2), but a singular observation has also been made for the tumour suppressor testin which was found in a protein complex with a minor GR isoform [57]. All three members of the paxillin family (paxillin, leupaxin and TGFB1I1) interact with NRs, in particular with AR [44, 58–60], but for other NRs this redundancy was disproven. In addition to AR, TGFB1I1 was found to interact with GR, ER, PR, PPARγ, TR4 and VDR [61–67]. It shares binding to GR with paxillin [60] and interaction with ERα with leupaxin [40] (but ERα does not interact with paxillin [60]).

Similar to FHL1 and 2, the LIM domains of group 3 members are crucial for mediating the interactions with NRs. For the AR-TGFB1I1 interaction, two FXXLF motifs in the second and fourth LIM domains of TGFB1I1 are important [68]. In contrast, transactivation of GR requires its LIM3 and LIM4 domains [62]. Furthermore, TGFB1I1 was also found as a ligand-dependent coactivator of PPARγ and the interaction is mediated through each LIM domain [64]. Transactivation of the GR and AR by paxillin requires its LIM domains and both receptors bind these domains in vitro in a NR ligand-independent manner [60]. For leupaxin it was shown that the third LIM domain is sufficient for interaction with AR [59]. Likewise, leupaxin binding of ERα is mediated by the LIM domains [40]. Within the nuclear receptors, distinct regions are responsible for their interaction with paxillin family members. In vitro, TGFB1I1 selectively interacts with the AF-2 region of the AR LBD [68], whereas it binds the tau-2 activation domain in GR [62, 69]. In a yeast two-hybrid system, it was shown that leupaxin interacts with the LBD of the AR in a ligand-dependent manner [59] but for the interaction with ERα, the NTD and DBD were required [40].

The zyxin family members: zyxin, LIM domain containing protein ajuba (ajuba), Thyroid receptor interacting protein 6 (TRIP6), LIM domain containing protein 1 (LIMD1) and Wilms tumour 1 interacting protein (WTIP), are also found in the nucleus in association with NRs (Table 2). They also display pleiotropy for NRs within the group and across the LIM domain protein groups. For instance, zyxin and LIMD1 interact with PPARγ, whereas LIMD1 and WTIP are capable of interacting with RAR [70–72]. TRIP6 was originally found as a ligand-dependent interaction partner of the THR and RXR [73], but also binds GR [74]. The most complex pattern is displayed by ajuba which interacts with the THRα, RAR, RXRγ, LXRα and PPARγ [46, 71, 72, 75] but does so in different manners. It directly interacts with RAR, via four conserved NR binding motifs in its N-terminal region and in the second and third LIM domains. Furthermore, the ajuba LIM domains mediate binding to the hinge and LBD of LXRα [75]. In contrast, its N-terminal region (which does not contain the LIM domains) interacts with the DBD of PPARγ [72]. Similarly, in a yeast two-hybrid screen, the latter nuclear receptor also interacts with an N-terminal region of zyxin [70]. These observations raise the possibility that members of the zyxin family possess interaction motifs for NRs in regions other than the LIM domains (which as outlined above are generally involved in NR interaction, see also Table 2). It will be important to investigate whether this also applies to other families of LIM domain proteins by dissecting the NR interaction regions within the LIM domain proteins in a more complete manner. We believe this is a necessary step to assess whether there is a link between their mode of interaction and the transcriptional activity of the NR, which is currently underexplored.

For other group 3 families, including PDZ-LIM, LASP, EPLIN, ABLIM or the proteins LMO7, ZNF185, LIM and calponin homology domains containing protein 1 and Sciellin, association with NRs has not yet been described. Since several members of these families have been observed in the nucleus [e.g. LIM domain and SH3 domain protein-1, PDZ and LIM domain protein 2 (Mystique)] [36, 76], the link between these LIM domain proteins and NRs, however, potentially exists.

Group 4 members include the LIM kinases (LIMK) and the MICAL family (Table 1). A potential link between MICAL family members and NRs has not been investigated yet, but LIMK-1 is involved in regulation of gene transcription via (interaction with) NRs (Table 2). In vitro, LIMK-1 interacts with the orphan receptor Nurr1. The LIM domains as well as the kinase domain of LIMK-1 are involved in the interaction with the LBD and NTD of Nurr1 [77].

The important function of LIM domain proteins as scaffolds for protein–protein interactions is in line with the observation that the LIM domains (or other parts) are capable of interacting with different NRs. However, this pleiotropy must be interpreted with caution. The evidence is mostly based on biochemical interaction studies in a specific cell type. Generality has not been assessed, let alone systematic investigation of competition between NRs for binding the same LIM domain protein (or vice versa). The functional outcome thereof is important because pleiotropy in the inherent competitive environment in the nucleus can differentially modulate the transcriptional activity of a certain NR (see next section), and hence the expression of a particular set of genes. Therefore, it is important to further map the specificity and pleiotropy of LIM domain protein–NR interactions and investigate what the consequences of this competition are within the context of cellular signalling. An equally important question is to what extent expression (or activation) of a certain NR and a particular LIM domain protein is co-regulated.

LIM domain proteins: emerging coactivators and corepressors of NRs

The fact that LIM domain proteins interact with NRs implies a logical involvement in NR-mediated gene transcription. Of note is that, although LIM domains consist of zinc fingers that are known interaction motifs for DNA [78], in mammals LIM domains are generally not considered as DNA-binding domains [79]. The only known exception so far is TGFB1I1 of which the LIM domains have been shown to interact with DNA in vitro, in a zinc-dependent manner [34]. However, it needs to be mentioned that investigations for establishing direct interactions between mammalian LIM domain proteins with nucleic acids are rarely performed. In this context we note that in plants, several members of the 2LIM family (closest mammalian homologs are the cysteine-rich protein family) are involved in transcription regulation through binding of DNA at promoter regions [80]. A more systematic analysis is necessary to assess whether mammalian LIM domain proteins have, in general, lost their capacity to bind DNA during evolution. Nevertheless, transcriptional effects of LIM domain proteins have been clearly established but appear to result mainly from the protein–protein scaffolding function of the LIM domains. This is in line with the notion that NR-associated coregulators assemble into complexes at NR bound promoters to stimulate (coactivator) or repress (corepressor) NR-mediated gene transcription (examples of such activities by LIM domain proteins are depicted in red and green lines in Fig. 2). These coregulators exploit several mechanisms: by interacting with the basal transcription machinery, by inducing chromatin remodelling through histone (de)acetylation or (de)methylation or by recruiting chromatin modifying enzymes [6, 81]. During the last two decades, it has indeed been found that LIM domain proteins either act as direct coregulators of NRs or influence transcription by indirect mechanisms.

These two global manners of regulation are interchangeably used within LIM domain protein groups and families. For instance, the group 2 LIM domain protein FHL2, binds LXR and enhances its interaction with DNA [52]. In contrast, FHL2 and FHL1 indirectly reduce transcriptional activity of Nur77 and ER, respectively, by inhibiting interaction of these NRs with their target promoters [50, 55].

TGFB1I1 binds the GR and in this context it was proposed that it functions as a scaffold that assembles coactivator complexes at GR-responsive promoters leading to GR-mediated gene expression. These complexes involve the histone acetyltransferases transcriptional intermediary factor 2 (TIF-2) and p300, as well as CREB binding protein (CBP), the Med1 mediator complex subunit and RNA polymerase II [82, 83]. Interestingly, TGFB1I1 can also block transcription of GR-responsive genes by interacting with chromatin modifying enzymes and GR itself. This prevents them from localizing to GR promoter regions [83]. Recently, it was found that these TGFB1I1-mediated regulatory functions with opposite effects also apply to ERα and GRγ (this form differs from the more abundant GRα isoform by a single arginine insertion in the DBD) [63]. Furthermore, TGFB1I1 also represses TR4-mediated transcription by enhancing acetylation of its DBD, through the recruitment of CBP, which reduces DNA binding of this NR with its target promoter [67].

Ajuba, which is a coactivator of LXR and PPARγ, recruits CBP to target promoter regions of these NRs and enhances their transcriptional activity by promoting histone acetylation at these loci [72, 75]. Nuclear TRIP6 is capable of recruiting AP-1 and NF-κB to GR-responsive promoters leading to transcriptional repression of GR [74]. Conversely, at AP-1 recognition sites in promoters, TRIP6 recruits GR which blocks the interaction of TRIP6 with the mediator complex subunit THRAP3, leading to transrepression of AP-1 [84]. Intriguingly, in a recent proteomics study both GR and THRAP3 were identified as proximity partners of the LIM domain protein testin [57]. Zyxin decreases RAR activity by forming a ternary complex with the known RAR corepressor PTOV1 and the RAR coactivator and mediator complex protein CBP (a histone acetyltransferase). In this case, zyxin does not bind RAR but to CBP which leads to the dissociation of the latter from the RAR responsive promoter [46]. Similarly, FHL2, which enhances PPARα transcriptional activity, does not directly interact with this NR [85]. Furthermore, LIMK-1 influences AR and RAR activity but a potential direct binding with these receptors has not been studied yet [86, 87]. These observations are rather exceptional since, in most cases, the effects of LIM domain proteins on transcription by NRs are mediated by interactions between these proteins (Table 2).

As mentioned above, TGFB1I1 is capable of both increasing or decreasing the transcriptional activity of GRα, GRγ and ERα (see Table 2). This seems peculiar but raises the question whether other LIM domain proteins are also capable of exerting both effects on the NRs they associate with. As observed for TGFB1I1, the opposite effects are gene-specific [63, 83] and depend on the specific composition of regulatory protein complexes, assembled at the promoters that codetermine the effect of the LIM domain protein on its NR partner. It remains to be investigated whether such dual activity is generally applicable for NR–LIM domain protein interactions, but this notion is in line with the widely accepted function of LIM domain proteins as scaffolding proteins, allowing context-dependent recruitment of transcription factors. However, in view of our scarce knowledge on these nuclear scaffolding functions of LIM domain proteins, further investigations are necessary to elucidate the underlying direct or indirect mechanisms influencing NR-mediated gene transcription.

Physiological and pathological aspects of LIM domain protein–NR interactions

Following the pleiotropy described above, it is not surprising that the LIM domain protein–NR interactions influence transcription of a wide set of genes. From a biological point of view, the effects of transcription contribute to normal cell physiology but are, in some cases, also associated with pathology (Table 3). Similar to many studies on other biological systems or disease models, our knowledge is fragmentary but the LIM domain protein–NR interaction is most often studied in the context of cancer, in particular tumour cell proliferation.

Table 3.

Physiological/pathological processes involving LIM domain protein–NR interactions

| LIM domain protein | NR | Physiological/pathological process | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| FHL1 | ER | Breast cancer | [55] |

| FHL2 | AR | Prostate function and cancer | [49, 51] |

| LRH-1 | Ovary function and mammalian reproduction | [53] | |

| SF-1 | Ovary function and mammalian reproduction | [53] | |

| LXR | Cholesterol metabolism | [52] | |

| Nur77 | Vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation | [50] | |

| ER | Breast cancer | [54] | |

| Paxillin | AR | Prostate cancer | [45, 60] |

| Leupaxin | AR | Prostate cancer | [59] |

| ERα | Breast cancer | [40] | |

| TGFB1I1 | AR | Prostate cancer | [44, 61, 88, 96] |

| PPARγ | Differentiation of gut epithelium | [64] | |

| VDR | 1,25D3 metabolism in prostate cancer | [65] | |

| PR | Endometriosis | [66] | |

| Ajuba | LXRα | Lipid and glucose metabolism | [75] |

| PPARγ | Adipogenesis | [72] | |

| LIMK-1 | AR | Prostate cancer | [87] |

| RAR | T-lymphocyte activation | [86] | |

| Nurr1 | Differentiation and survival of dopaminergic neurons | [77] |

Repression of the ER-responsive genes cathepsin D and pS2 by FHL1 results in inhibition of breast cancer cell growth [55]. Similar effects on ER-mediated transcription in breast cancer cells were observed for FHL2, which additionally cooperates synergistically with the transcription factor Smad4 to repress cathepsin D expression [54]. FHL2 has also been associated with prostate cancer progression. In castrate-resistant prostate cancer, FHL2 acts as a ligand-independent coactivator of cancer-associated AR variants [49]. However, FHL2 was also proposed to play a role in normal prostate function by enhancing the transcription of the AR target gene probasin [51]. In vascular smooth muscle cells, FHL2 inhibits Nur77-mediated transcription, promoting their proliferation. In contrast, in the same cell system, FHL2 enhances transcriptional activity of the LXR which is necessary for a normal cholesterol metabolism of the smooth muscle cells [50, 52]. Furthermore, FHL2 functions as a coactivator of the orphan receptors LRH-1 and SF-1, which in part regulate a common set of genes, leading to inhibin-α gene expression in ovarian granulosa cells necessary for mammalian reproduction [53].

Also members of the paxillin family are often seen to play a role in NR-associated cancer, in particular prostate cancer. Several studies suggest that TGFB1I1-induced AR activation contributes to prostate cancer progression [44, 61, 88]. However, another study proposed a potential beneficial role for TGFB1I1 in prostate cancer based on the observation that TGFB1I1 sensitizes the VDR in prostate cancer cells to the anti-proliferative effects of the VDR ligand 1,25-dihydroxy-vitamin D3 (1,25D3) [65]. Similar to TGFB1I1, paxillin and leupaxin are linked to prostate cancer. MAPK-dependent phosphorylation of paxillin mediates AR transactivation, which leads to upregulation of prostate specific-antigen (PSA) and NKX3-1, resulting in enhanced tumour cell growth in vivo [45]. Leupaxin also enhances AR-mediated transcription and promotes the invasive capacity and motility of prostate cancer cells [59]. However, members of the paxillin family are also linked to other diseases. Leupaxin stimulates ERα transcriptional activity which is thought to be responsible for an enhanced migratory capacity of breast cancer cells [40]. TGFB1I1 coactivates PR-responsive genes and impaired TGFB1I1 expression is associated with progesterone resistance in endometriosis [66]. TGFB1I1-mediated PPARγ transactivation selectively upregulates gut epithelial markers such as keratin 20, L-FABP and KLF4, implicating a role for TGFB1I1 in gut epithelium differentiation [64].

Within the zyxin family, the founding member was shown to repress RAR function which counteracts retinoic acid (a RAR ligand) induced cytotoxic effects on H1299 lung cancer cells [46]. Ajuba upregulates LXR target genes in liver cells suggesting a role for ajuba in lipid and glucose metabolism [75]. Moreover, ajuba activates PPARγ-mediated transcription of adipogenesis related genes such as FABP4 and CD36 [72].

Studies on coregulatory aspects and transcriptional effects of NRs by group 4 members of LIM domain proteins are scarce and limited to investigations of LIMK-1. It was found to be involved in androgen-dependent prostate cancer. Inhibition of LIMK-1 reduces nuclear localization and hence transcriptional activity of the AR. This was shown to contribute to decreased cell motility and proliferation of prostate cancer cells [87]. Furthermore, the LIMK-1–Nurr1 interaction (see section on pleiotropy) is important in the nervous system. It represses the transcriptional activity of Nurr1, which plays a key role in differentiation and survival of dopaminergic neurons [77]. Similarly, LIMK-1 decreases RAR activity, leading to T-lymphocyte activation [86].

These examples illustrate the importance of the NR–LIM domain protein interactions in physiological processes and the deregulation of their interplay in diseases, but also demonstrate that their combined effect is strongly dependent on their (tumour) specific cellular context.

Conclusions and future perspectives

LIM domain proteins have traditionally been linked to the cytosolic actin cytoskeleton, but over the last two decades, evidence has accumulated that they interact with NRs and function as coregulators of NR-mediated gene transcription [18, 19]. Although LIM domain proteins appear to have differential roles in the cytosol and the nucleus, the evidence discussed above suggests these functions are interconnected. In part this is because for both the cytoplasmic actin regulatory and the nuclear coregulatory function, the LIM domains seem to be crucial as interaction or targeting domains. For the interaction with NRs, pleiotropy has been observed within, as well as between, the different groups of LIM domain proteins. Although it is evident that, in some cases, NR ligands serve as initial triggers for nuclear translocation of LIM domain proteins, this has not been mapped in a more general or systematic way. This merits attention because temporal regulation of specificity of NR–LIM domain protein interactions could at least in part arise from selective nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling of particular LIM domain proteins.

In line with the view that LIM domains are molecular scaffolds for protein–protein interactions in the cytoplasm, these domains enable the recruitment of NRs, other transcription factors, cofactors, chromatin remodelling enzymes and other members of the transcription machinery. As such, LIM domain proteins assist the regulation of gene expression as part of coactivator or corepressor complexes. The exact mechanisms that LIM domain proteins use to perform their coregulatory functions for NRs are only poorly characterized but the fragmentary information already suggests very diverse ways of action. These mechanisms of modulation of gene expression can be direct, as evidenced by some of the examples given above, or indirect, for example by modulating chromatin occupancy of NRs [63, 83]. Another possible but yet unexplored mechanism of indirect regulation is that, similar to the situation in the cytoplasm, LIM domain proteins cooperate with actin or actin-binding proteins in the nucleus. Indeed, actin remodelling in the nucleus has been linked to transcription-related processes including RNA transcription and chromatin remodelling. Moreover, several actin-binding proteins such as cofilin, gelsolin, supervillin, α-actinin and filamin are involved in NR-mediated gene transcription [89–94]. The possibility that LIM domain proteins exert part of their function towards NRs by interacting with the nuclear actin cytoskeleton, therefore opens an additional mechanistic avenue for regulation.

Collectively, the multiple direct and indirect mechanisms by which LIM domain proteins influence NR-mediated gene transcription suggest a very complex landscape of regulation. Although this can be expected from molecular scaffolds, the complexity is further increased by the observed pleiotropy of LIM domain proteins for NRs. Dissecting the different levels of LIM domain protein-mediated NR regulation will require a large body of challenging research. In our opinion, this will, however, be necessary to understand the consequences of LIM domain protein–NR interactions in normal physiological processes such as reproduction and metabolism. Since NR activity is also linked to pathology, in particular cancer in the context of LIM domain proteins [1–3], it can be expected that their interplay contributes to disease progression due to their deregulated expression [95]. For instance, FHL1 is often upregulated in ER-related breast cancer, whereas paxillin and leupaxin are upregulated in AR-related prostate cancer [45, 55, 59]. In view of their scaffolding function, it is possible that altered expression also shifts equilibria in transcriptional complexes. Therefore, it is crucial to further investigate the composition of such transcriptional complexes at NR target promoters, and in view of the pleiotropy, the contribution of the various LIM domain proteins as coregulators therein. Unravelling the mechanisms of these coregulatory functions of LIM domain proteins will also lead to better understanding how deregulated expression of these proteins alters NR-mediated gene expression in disease. This last aspect is confounded by potentially differential functions of the nuclear and cytoplasmic populations of LIM domain proteins resulting in different nuclear programs. Mapping these differential functions and understanding them in a disease context will form an enormous challenge for future research on NR–LIM domain protein interactions.

References

- 1.Lee JS, Kim KI, Baek SH. Nuclear receptors and coregulators in inflammation and cancer. Cancer Lett. 2008;267(2):189–196. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Skerrett R, Malm T, Landreth G. Nuclear receptors in neurodegenerative diseases. Neurobiol Dis. 2014;72(Part A):104–116. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schulman IG. Nuclear receptors as drug targets for metabolic disease. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2010;62(13):1307–1315. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robinson-Rechavi M, Garcia HE, Laudet V. The nuclear receptor superfamily. J Cell Sci. 2003;116(4):585–586. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bain DL, Heneghan AF, Connaghan-Jones KD, Miura MT. Nuclear receptor structure: implications for function. Annu Rev Physiol. 2007;69(1):201–220. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.69.031905.160308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heitzer MD, Wolf IM, Sanchez ER, Witchel SF, DeFranco DB. Glucocorticoid receptor physiology. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2007;8(4):321–330. doi: 10.1007/s11154-007-9059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tabur S, Oztuzcu S, Oguz E, Demiryu S, Dagli H, Alasehirli B, et al. Evidence for elevated (LIMK2 and CFL1) and suppressed (ICAM1, EZR, MAP2K2, and NOS3) gene expressions in metabolic syndrome. Endocrine. 2016;53(2):465–470. doi: 10.1007/s12020-016-0910-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ni C, Qiu H, Rezvan A, Kwon K, Nam D, Son DJ, et al. Discovery of novel mechanosensitive genes in vivo using mouse carotid artery endothelium exposed to disturbed flow. Blood. 2010;116(15):E66–E73. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-278192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mullen RD, Colvin SC, Hunter CS, Savage JJ, Walvoord EC, Bhangoo APS, et al. Roles of the LHX3 and LHX4 LIM-homeodomain factors in pituitary development. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2007;265:190–195. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2006.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ono R, Kaisho T, Tanaka T. PDLIM1 inhibits NF-κB-mediated inflammatory signaling by sequestering the p65 subunit of NF-κB in the cytoplasm. Sci Rep. 2015;5:18327. doi: 10.1038/srep18327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alnajar A, Nordhoff C, Schied T, Chiquet-ehrismann R, Loser K, Vogl T, et al. The LIM-only protein FHL2 attenuates lung inflammation during bleomycin-induced fibrosis. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e81356. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muller JM, Metzger E, Greschik H. The transcriptional coactivator FHL2 transmits Rho signals from the cell membrane into the nucleus. EMBO J. 2002;21(4):736–748. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.4.736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caltagarone J, Hamilton RL, Murdoch G, Jing Z, DeFranco DB, Bowser R. Paxillin and hydrogen peroxide-inducible clone 5 expression and distribution in control and Alzheimer disease hippocampi. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2010;69(4):356–371. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181d53d98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ehaideb SN, Wignall EA, Kasuya J, Evans WH, Iyengar A, Koerselman HL, et al. Mutation of orthologous prickle genes causes a similar epilepsy syndrome in flies and humans. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2016;3(9):695–707. doi: 10.1002/acn3.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lanni C, Necchi D, Pinto A, Buoso E, Buizza L, Memo M, et al. Zyxin is a novel target for beta-amyloid peptide: characterization of its role in Alzheimer’s pathogenesis. J Neurochem. 2013;125(5):790–799. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matthews JM, Lester K, Joseph S, Curtis DJ. LIM-domain-only proteins in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13(2):111–122. doi: 10.1038/nrc3418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li A, Ponten F, dos Remedios CG. The interactome of LIM domain proteins: the contributions of LIM domain proteins to heart failure and heart development. Proteomics. 2012;12(2):203–225. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201100492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zheng Q, Zhao Y. The diverse biofunctions of LIM domain proteins: determined by subcellular localization and protein-protein interaction. Biol Cell. 2007;99(9):489–502. doi: 10.1042/BC20060126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kadrmas JL, Beckerle MC. The LIM domain: from the cytoskeleton to the nucleus. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5(11):920–931. doi: 10.1038/nrm1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stournaras C, Gravanis A, Margioris AN, Lang F. The actin cytoskeleton in rapid steroid hormone actions. Cytoskeleton. 2014;71(5):285–293. doi: 10.1002/cm.21172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sever R, Glass CK. Signaling by nuclear receptors. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5(3):1–4. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a016709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mullican SE, DiSpirito JR, Lazar MA. The orphan nuclear receptors at their 25-year reunion. J Mol Endocrinol. 2013;51(3):T115–T140. doi: 10.1530/JME-13-0212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schock SC, Xu J, Duquette PM, Qin Z, Lewandowski AJ, Rai PS, et al. Rescue of neurons from ischemic injury by peroxisome proliferator-activated-receptor requires a novel essential cofactor LMO4. J Neurosci. 2008;28(47):12433–12444. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2897-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gu H, Liu T, Cai X, Tong Y, Li Y, Wang C, et al. Upregulated LMO1 in prostate cancer acts as a novel coactivator of the androgen receptor. Int J Oncol. 2015;47(6):2181–2187. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2015.3195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Y, Gilmore TD. Zyxin and paxillin proteins: focal adhesion plaque LIM domain proteins go nuclear. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1593(2–3):115–120. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4889(02)00349-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rath N, Wang Z, Lu MM, Morrisey EE. LMCD1/Dyxin is a novel transcriptional cofactor that restricts GATA6 function by inhibiting DNA binding. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(20):8864–8873. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.20.8864-8873.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang C, Lin S, Su W, Ho C, Jou Y. Somatic LMCD1 mutations promoted cell migration and tumor metastasis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene. 2012;31:2640–2652. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garvalov BK, Higgins TE, Sutherland JD, Zettl M, Scaplehorn N, Köcher T, et al. The conformational state of Tes regulates its zyxin-dependent recruitment to focal adhesions. J Cell Biol. 2003;161(1):33–39. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200211015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coutts AS, MacKenzie E, Griffith E, Black DM. TES is a novel focal adhesion protein with a role in cell spreading. J Cell Sci. 2003;116(Pt 5):897–906. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nix DA, Beckerle MC. Nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling of the focal contact protein, zyxin: a potential mechanism for communication between sites of cell adhesion and the nucleus. J Cell Biol. 1997;138(5):1139–1147. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.5.1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang Y, Gilmore TD. LIM domain protein Trip6 has a conserved nuclear export signal, nuclear targeting sequences, and multiple transactivation domains. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1538(2–3):260–272. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4889(01)00077-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kanungo J, Pratt SJ, Marie H, Longmore GD. Ajuba, a cytosolic LIM protein, shuttles into the nucleus and affects embryonal cell proliferation and fate decisions. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11(10):3299–3313. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.10.3299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Petit MM, Fradelizi J, Golsteyn RM, Ayoubi TA, Menichi B, Louvard D, et al. LPP, an actin cytoskeleton protein related to zyxin, harbors a nuclear export signal and transcriptional activation capacity. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11(1):117–129. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.1.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nishiya N, Sabe H, Nose K, Shibanuma M. The LIM domains of hic-5 protein recognize specific DNA fragments in a zinc-dependent manner in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26(18):4267–4273. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.18.4267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Campana WM, Myers RR, Rearden A. Identification of PINCH in Schwann cells and DRG neurons: shuttling and signaling after nerve injury. Glia. 2003;41(3):213–223. doi: 10.1002/glia.10138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mihlan S, Reiß C, Thalheimer P, Herterich S, Gaetzner S, Kremerskothen J, et al. Nuclear import of LASP-1 is regulated by phosphorylation and dynamic protein–protein interactions. Oncogene. 2013;32(16):2107–2113. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang N, Mizuno K. Nuclear export of LIM-kinase 1, mediated by two leucine-rich nuclear export signals within the PDZ domain. Biochem J. 1999;338(Pt 3):793–798. doi: 10.1042/bj3380793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heitzer MD, DeFranco DB. Hic-5, an adaptor-like nuclear receptor coactivator. Nucl Recept Signal. 2006;4:e019. doi: 10.1621/nrs.04019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dong JM, Lau LS, Ng YW, Lim L, Manser E. Paxillin nuclear-cytoplasmic localization is regulated by phosphorylation of the LD4 motif: evidence that nuclear paxillin promotes cell proliferation. Biochem J. 2009;418(1):173–184. doi: 10.1042/BJ20080170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaulfuss S, Herr AM, Büchner A, Hemmerlein B, Günthert AR, Burfeind P. Leupaxin is expressed in mammary carcinoma and acts as a transcriptional activator of the estrogen receptor alpha. Int J Oncol. 2015;47(1):106–114. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2015.2988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ming S, Lee Y, Li HY, Kai E, Ng O, Man S, et al. Characterization of a brain-specific nuclear LIM domain protein (FHL1B) which is an alternatively spliced variant of FHL1. Gene. 1999;237:253–263. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(99)00251-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goyal P, Pandey D, Siess W. Phosphorylation-dependent regulation of unique nuclear and nucleolar localization signals of LIM kinase 2 in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(35):25223–25230. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603399200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mori K, Asakawa M, Hayashi M, Imura M, Ohki T, Hirao E, et al. Oligomerizing potential of a focal adhesion LIM protein Hic-5 organizing a nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling complex. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(31):22048–22061. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513111200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leach DA, Need EF, Trotta AP, Grubisha MJ, DeFranco DB, Buchanan G. Hic-5 influences genomic and non-genomic actions of the androgen receptor in prostate myofibroblasts. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2014;384(1–2):185–199. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sen A, De Castro I, DeFranco DB, Deng FM, Melamed J, Kapur P, et al. Paxillin mediates extranuclear and intranuclear signaling in prostate cancer proliferation. J Clin Investig. 2012;122(7):2469–2481. doi: 10.1172/JCI62044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Youn H, Kim EJ, Um SJ. Zyxin cooperates with PTOV1 to confer retinoic acid resistance by repressing RAR activity. Cancer Lett. 2013;331(2):192–199. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shibanuma M, Mori K, Kim-Kaneyama J, Nose K. Involvement of FAK and PTP-PEST in the regulation of redox-sensitive nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling of a LIM protein, Hic-5. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2005;7(2–3):335–347. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cattaruzza M, Lattrich C, Hecker M. Focal adhesion protein zyxin is a mechanosensitive modulator of gene expression in vascular smooth muscle cells. Hypertension. 2004;43(4):726–730. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000119189.82659.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McGrath MJ, Binge LC, Sriratana A, Wang H, Robinson PA, Pook D, et al. Regulation of the transcriptional coactivator FHL2 licenses activation of the androgen receptor in castrate-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2013;73(16):5066–5079. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kurakula K, Van Der Wal E, Geerts D, van Tiel CM, De Vries CJM. FHL2 protein is a novel co-repressor of nuclear receptor Nur77. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(52):44336–44343. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.308999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Muller J, Isele U, Metzger E, Rempel A, Moser M, Pscherer A, et al. FHL2, a novel tissue-specific coactivator of the androgen receptor. EMBO J. 2000;19(3):359–369. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.3.359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kurakula K, Sommer D, Sokolovic M, Moerland PD, Scheij S, van Loenen PB, et al. LIM-only protein FHL2 is a positive regulator of liver X receptors in smooth muscle cells involved in lipid homeostasis. Mol Cell Biol. 2015;35(1):52–62. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00525-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Matulis CK, Mayo KE. The LIM domain protein FHL2 interacts with the NR5A family of nuclear receptors and CREB to activate the inhibin-alpha subunit gene in ovarian granulosa cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2012;26(8):1278–1290. doi: 10.1210/me.2011-1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xiong Z, Ding L, Sun J, Cao J, Lin J, Lu Z, et al. Synergistic repression of estrogen receptor transcriptional activity by FHL2 and Smad4 in breast cancer cells. IUBMB Life. 2010;62(9):669–676. doi: 10.1002/iub.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ding L, Niu C, Zheng Y, Xiong Z, Liu Y, Lin J, et al. FHL1 interacts with oestrogen receptors and regulates breast cancer cell growth. J Cell Mol Med. 2011;15(1):72–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00938.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kobayashi S, Shibata H, Yokota K, Suda N, Murai A, Kurihara I, et al. FHL2, UBC9, and PIAS1 are novel estrogen receptor alpha-interacting proteins. Endocr Res. 2004;30(4):617–621. doi: 10.1081/ERC-200043789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sala S, Van Troys M, Medves S, Catillon M, Timmerman E, Staes A, et al. Expanding the interactome of TES by exploiting TES modules with different subcellular localizations. J Proteome Res. 2017;16(5):2054–2071. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.7b00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang X, Yang Y, Guo X, Sampson ER, Hsu C, Tsai M, et al. Suppression of androgen receptor transactivation by Pyk2 via interaction and phosphorylation of the ARA55 coregulator. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(18):15426–15431. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111218200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kaulfuss S, Grzmil M, Hemmerlein B, Thelen P, Schweyer S, Neesen J, et al. Leupaxin, a novel coactivator of the androgen receptor, is expressed in prostate cancer and plays a role in adhesion and invasion of prostate carcinoma cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22(7):1606–1621. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kasai M, Guerrero-santoro J, Friedman R, Leman ES, Getzenberg RH, Defranco DB. The group 3 LIM domain protein paxillin potentiates androgen receptor transactivation in prostate cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 2003;63(28):4927–4935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fujimoto N, Yeh S, Kang HY, Inui S, Chang HC, Mizokami A, et al. Cloning and characterization of androgen receptor coactivator, ARA55, in human prostate. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(12):8316–8321. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.12.8316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yang L, Guerrero J, Hong H, DeFranco DB, Stallcup MR. Interaction of the tau2 transcriptional activation domain of glucocorticoid receptor with a novel steroid receptor coactivator, Hic-5, which localizes to both focal adhesions and the nuclear matrix. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11(6):2007–2018. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.6.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chodankar R, Wu D, Gerke DS, Stallcup MR. Selective coregulator function and restriction of steroid receptor chromatin occupancy by Hic-5. Mol Endocrinol. 2015;29(5):716–729. doi: 10.1210/me.2014-1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Drori S, Girnun GD, Tou L, Szwaya JD, Mueller E, Kia X, et al. Hic-5 regulates an epithelial program mediated by PPARγ. Genes Dev. 2005;19(3):362–375. doi: 10.1101/gad.1240705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Solomon JD, Heitzer MD, Liu TT, Beumer JH, Parise RA, Normolle DP, et al. VDR activity is differentially affected by Hic-5 in prostate cancer and stromal cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2014;12(8):1166–1180. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-13-0395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Aghajanova L, Velarde MC, Giudice LC. The progesterone receptor coactivator Hic-5 is involved in the pathophysiology of endometriosis. Endocrinology. 2009;150(8):3863–3870. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Xie S, Ni J, Lee Y, Liu S, Li G, Shyr C, et al. Increased acetylation in the DNA-binding domain of TR4 nuclear receptor by the coregulator ARA55 leads to suppression of TR4 transactivation. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(24):21129–21136. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.208181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.He B, Minges JT, Lee LW, Wilson EM. The FXXLF motif mediates androgen receptor-specific interactions with coregulators. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(12):10226–10235. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111975200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Guerrero-Santoro J, Yang L, Stallcup MR, DeFranco DB. Distinct LIM domains of Hic-5/ARA55 are required for nuclear matrix targeting and glucocorticoid receptor binding and coactivation. J Cell Biochem. 2004;92(4):810–819. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Li B, Trueb B. Analysis of the alpha-Actinin/Zyxin interaction. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(36):33328–33335. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100789200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hou Z, Peng H, White DE, Negorev DG, Maul GG, Feng Y, et al. LIM protein Ajuba functions as a nuclear receptor corepressor and negatively regulates retinoic acid signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2010;107(7):2938–2943. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908656107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li Q, Peng H, Fan H, Zou X, Liu Q, Zhang Y, et al. The LIM protein Ajuba promotes adipogenesis by enhancing PPARγ and p300/CBP interaction. Cell Death Differ. 2016;23(1):158–168. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2015.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lee JW, Choi HS, Gyuris J, Brent R, Moore DD. Two classes of proteins dependent on either presence or absence of thyroid hormone for interaction with the thyroid-hormone receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 1995;9(2):243–254. doi: 10.1210/mend.9.2.7776974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Diefenbacher ME, Litfin M, Herrlich P, Kassel O. The nuclear isoform of the LIM domain protein Trip6 integrates activating and repressing signals at the promoter-bound glucocorticoid receptor. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;320(1–2):58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2010.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fan H, Dong W, Li Q, Zou X, Zhang Y, Wang J, et al. Ajuba preferentially binds LXRα/RXRγ heterodimer to enhance LXR target gene expression in liver cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2015;29(11):1608–1618. doi: 10.1210/me.2015-1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Healy NC, O’Connor R. Sequestration of PDLIM2 in the cytoplasm of monocytic/macrophage cells is associated with adhesion and increased nuclear activity of NF-kappaB. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;85(3):481–490. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0408238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sacchetti P, Carpentier R, Ségard P, Olivé-Cren C, Lefebvre P. Multiple signaling pathways regulate the transcriptional activity of the orphan nuclear receptor NURR1. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(19):5515–5527. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Eom KS, Cheong JS, Lee SJ. Structural analyses of zinc finger domains for specific interactions with DNA. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2016;26(12):2019–2029. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1609.09021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Matthews JM, Bhati M, Lehtomaki E, Mansfield RE, Cubeddu L, Mackay JP. It takes two to tango: the structure and function of LIM, RING, PHD and MYND domains. Curr Pharm Des. 2009;15(31):3681–3696. doi: 10.2174/138161209789271861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Moes D, Gatti S, Hoffmann C, Dieterle M, Moreau F. A LIM domain protein from tobacco involved in actin-bundling and histone gene transcription. Mol Plant. 2013;6(2):483–502. doi: 10.1093/mp/sss075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.McKenna NJ, Lanz RB, O’Malley BW. Nuclear receptor coregulators: cellular and molecular biology. Endocr Rev. 1999;20(3):321–344. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.3.0366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Heitzer MD, DeFranco DB. Mechanism of action of Hic-5/androgen receptor activator 55, a LIM domain-containing nuclear receptor coactivator. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20(1):56–64. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chodankar R, Wu DY, Schiller BJ, Yamamoto KR, Stallcup MR. Hic-5 is a transcription coregulator that acts before and/or after glucocorticoid receptor genome occupancy in a gene-selective manner. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2014;111(11):4007–4012. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400522111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Diefenbacher ME, Reich D, Dahley O, Kemler D, Litfin M, Herrlich P, et al. The LIM domain protein nTRIP6 recruits the mediator complex to AP-1-regulated promoters. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e97549. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ciarlo JD, Flores AM, McHugh NG, Aneskievich BJ. FHL2 expression in keratinocytes and transcriptional effect on PPARgamma/RXRalpha. J Dermatol Sci. 2004;35(1):61–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2004.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ishaq M, Lin BR, Bosche M, Zheng X, Yang J, Huang D, et al. LIM kinase 1- dependent cofilin 1 pathway and actin dynamics mediate nuclear retinoid receptor function in T lymphocytes. BMC Mol Biol. 2011;12(1):41. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-12-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mardilovich K, Gabrielsen M, McGarry L, Orange C, Patel R, Shanks E, et al. Elevated LIM kinase 1 in nonmetastatic prostate cancer reflects its role in facilitating androgen receptor nuclear translocation. Mol Cancer Ther. 2015;14(1):246–258. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-14-0447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rahman MM, Miyamoto H, Lardy H, Chang C. Inactivation of androgen receptor coregulator ARA55 inhibits androgen receptor activity and agonist effect of antiandrogens in prostate cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(9):5124–5129. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0530097100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Obrdlik A, Percipalle P. The F-actin severing protein cofilin-1 is required for RNA polymerase II transcription elongation. Nucleus. 2011;2(1):72–79. doi: 10.4161/nucl.14508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kristό I, Bajusz I, Bajusz C, Borkúti P, Vilmos P. Actin, actin-binding proteins, and actin-related proteins in the nucleus. Histochem Cell Biol. 2016;145(4):373–388. doi: 10.1007/s00418-015-1400-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Savoy RM, Chen L, Siddiqui S, Melgoza FU, Durbin-Johnson B, Drake C, et al. Transcription of Nrdp1 by the androgen receptor is regulated by nuclear filamin A in prostate cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2015;22(3):369–386. doi: 10.1530/ERC-15-0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zhao X, Khurana S, Charkraborty S, Tian Y, Sedor JR, Bruggman LA, et al. α actinin 4 (ACTN4) regulates glucocorticoid receptor-mediated transactivation and transrepression in podocytes. J Biol Chem. 2017;292(5):1637–1647. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.755546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ting HJ, Yeh S, Nishimura K, Chang C. Supervillin associates with androgen receptor and modulates its transcriptional activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2002;99(2):661–666. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022469899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Nishimura K, Ting HJ, Harada Y, Tokizane T, Nonomura N, Kang HY, et al. Modulation of androgen receptor transactivation by gelsolin. Cancer Res. 2003;63(16):4888–4894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Dasgupta S, Lonard DM, O’Malley BW. Nuclear receptor coactivators: master regulators of human health and disease. Annu Rev Med. 2014;65(1):279–292. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-051812-145316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Heitzer MD, DeFranco DB. Hic-5/ARA55, a LIM domain-containing nuclear receptor coactivator expressed in prostate stromal cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66(14):7326–7333. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]