Abstract

Mammalian two-pore channels (TPCs) are activated by the low-abundance membrane lipid phosphatidyl-(3,5)-bisphosphate (PI(3,5)P2) present in the endo-lysosomal system. Malfunction of human TPC1 or TPC2 (hTPC) results in severe organellar storage diseases and membrane trafficking defects. Here, we compared the lipid-binding characteristics of hTPC2 and of the PI(3,5)P2-insensitive TPC1 from the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Combination of simulations with functional analysis of channel mutants revealed the presence of an hTPC2-specific lipid-binding pocket mutually formed by two channel regions exposed to the cytosolic side of the membrane. We showed that PI(3,5)P2 is simultaneously stabilized by positively charged amino acids (K203, K204, and K207) in the linker between transmembrane helices S4 and S5 and by S322 in the cytosolic extension of S6. We suggest that PI(3,5)P2 cross links two parts of the channel, enabling their coordinated movement during channel gating.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00018-018-2829-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Electrophysiology, Homology model, Ion channel, Ligand-binding, Molecular dynamics simulation, Site-directed mutagenesis

Introduction

Low-abundance membrane lipids increasingly gain attention as important regulators of ion channel function [1–3]. A major signalling lipid in the plasma membrane is phosphatidyl-4,5-bisphosphate (PI(4,5)P2), which is required for proper function of several ion channels, including transient receptor potential channels and voltage-gated potassium channels [1, 3, 4]. In most cases, however, lack of structural information hampers the analysis of the molecular nature of lipid-binding to the channels. In 2012, the very low-abundant lipid PI(3,5)P2 was shown to gate the otherwise voltage-independent mammalian two-pore channel TPC2 [5]. Similarly, the voltage-dependent mammalian TPC1 also functions as a PI(3,5)P2-activated channel [6–8]. Recently, structural information of a plant TPC1 channel from Arabidopsis thaliana has been obtained [9, 10]. Since the latter channel is insensitive to PI(3,5)P2 [11], the TPC channel family provides an excellent model for a comparative study of isoform-specific lipid-binding and lipid regulation of ion channels.

Two-pore channels are cation channels present in membranes of endo-lysosomal compartments in animals (TPC1-3) and plant vacuoles (TPC1) [12, 13]. Impairment of their proper function is associated with diverse endo-lysosomal trafficking and storage disorders [14]. Over the last years, hTPC2 called more and more attention, based on its importance for sensing the cellular nutrient status, Ebola virus infection, migration of cancer cells, neoangiogenesis [15], and prevention of fatty liver disease [6, 16–18]. In the light of their contribution to various diseases, TPCs are of utmost interest as potential targets for drugs and medical therapies.

TPCs belong to the superfamily of voltage-gated ion channels [19] and are composed of two homologous, but not identical Shaker-like 6-transmembrane (S1–S6; S7–S12) domains interconnected by a cytosolic linker (Fig. 1). In the functional homo-dimer, four helix pairs—S5–S6 and S11–S12 of each monomer—establish the pore with S6 and S12 helices lining the pore wall [9, 10]. Two-pore helices (P1 and P2) between S5 and S6, and S11 and S12, respectively, contain filter regions that determine the selectivity of the channel. While TPC1 from the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana (AtTPC1) is permeable to monovalent alkali cations and also to Ca2+, hTPC2 strongly selects for Na+ against K+ and Ca2+ mainly due to differences in the second filter region [20, 21]. Besides the diversification in their permeation properties, mammalian and plant TPCs have evolved different regulation mechanisms. In plant TPC1 channels, the central cytosolic linker bridging the Shaker-like domains harbours two EF hands, and Ca2+-binding to EF-hand 2 has been shown to be crucial for Ca2+- and voltage-dependent channel gating [10, 22]. In a previous study, we reported that homo-dimerization via the C-terminus is required for AtTPC1 function [23]. Animal TPCs lack cytosolic Ca2+ sensors and have initially been described as receptors for nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP), which triggers Ca2+-release from acidic organelles [13, 24–26]. While the direct activation of TPCs by NAADP appears unlikely, several recent studies have shown that mammalian TPC1 and TPC2 but not Arabidopsis TPC1 channels are activated by PI(3,5)P2 and in turn mediate Na+-release from acidic organelles [5–8, 11].

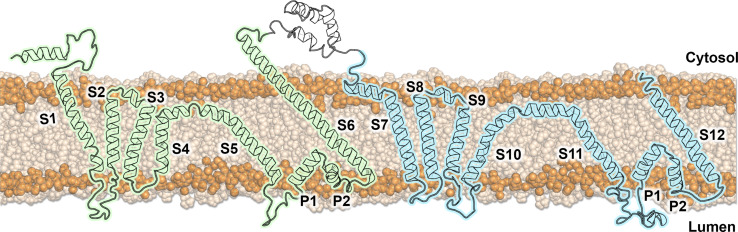

Fig. 1.

Topology of hTPC2. The three-dimensional structure of model hTPC2 was mapped onto a one-dimensional plane while keeping tilt angles between the helices and the membrane normal fixed. The two Shaker-like subunits are highlighted in green and blue, respectively, the membrane and phosphorus atoms in light brown and orange. Parts of the N-terminus and the C-terminus are missing, because they have not been structurally resolved in the model AtTPC2 template [10]

However, a direct interaction of PI(3,5)P2 with TPC channels could not be shown so far. Here, we combined patch-clamp measurements, site-directed mutagenesis, and both coarse-grained and atomistic molecular dynamics (MD) simulations [27] to provide molecular evidence of a specific positively charged binding site for PI(3,5)P2 formed by the S4-S5 linker and the extension of helix S6 (S6ext), mediating the activation of hTPC2 by PI(3,5)P2. In contrast, binding of PI(3,5)P2 to the corresponding site in AtTPC1 was not observed. Our data allow novel structural and functional insights into the lipid-binding and activation mechanism of TPCs.

Materials and methods

Starting structures

To investigate the comparative binding behaviour of phosphatidylinositol-(3,5)-bisphosphate (PI(3,5)P2) lipids to the human Two-Pore Channel 2 (hTPC2) and the plant TPC1 (AtTPC1), we used coarse-grained (CG) molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. For this purpose, each protein was embedded in a 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl phosphatidylcholine (POPC) membrane containing in total either 1 or 2% PI(3,5)P2 lipids (8 or 16 molecules) in the cytosolic leaflet. Starting structures were prepared based on the procedure described in [28]. First, a homology model of hTPC2 (residues 47–708, UniProt accession number: Q8NHX9) was generated from the recently published crystal structure of AtTPC1 [10] (residues 32–686, UniProt accession number: Q94KI8, PDB: 5E1J) using SWISS-MODEL [29–32]. The sequence alignment provided by SWISS-MODEL is shown in Supplemental Fig. 1a. The sequence identity in the transmembrane (TM) region (35.80%) is higher than over the whole sequence (23.20%, similarity 33%, target sequence coverage of 91%). In line with this, we obtained a homology model with a high reliability in the TM region, whereas soluble and loop regions with a higher diversity in secondary structure display a lower confidence level (Supplemental Fig. 1b). The reliability was assessed based on the QMEANBrane scoring function, which was developed for membrane proteins and provides information about the nativeness of the protein structure [33]. In an atomistic control simulation of the modeled hTPC2 embedded in a phosphatidylcholine bilayer (data not shown), the TM part of the protein was stable on a 500 ns timescale with a root mean square deviation from the starting structure of approx. 0.4 nm.

Next, the modeled hTPC2 structure was converted to CG representation using martinize [34], followed by an energy minimization with a steepest descent algorithm for 500 steps. Subsequently, the tool insane [35] was used to surround the protein with 800 lipids, ~ 20,000 polarizable water beads [36] and counter ions for neutralization. A sequence of protein position restraint simulations (in total 5 ns) with increasing integration step sizes (1–20 fs) followed an additional energy minimization (500 steps) to allow for equilibration of the system.

To model a similar starting environment for both hTPC2 and AtTPC1, hTPC2 was replaced by the coarse-grained crystal structure of AtTPC1, and the system energy-minimized and simulated for 5 ns with position restraints on the protein. Missing residues of loop regions in the atomistic plant TPC protein structure were added with the program MODELLER [37] followed by an energy minimization with frozen coordinates of resolved, pre-existing residues and transformation to coarse-grained representation [34].

Each starting configuration, i.e., hTPC2 or AtTPC1 protein embedded in a POPC membrane with either 1 or 2% PI(3,5)P2 lipids, was simulated three times with varying starting velocities for a simulation length of each 1 µs (in total 12 simulations).

An atomistic starting structure was prepared by converting a coarse-grained structure at the end (t = 1 µs) of one simulation to atomistic representation with the tool backward [38], followed by a short equilibration simulation (5 ns) with position restraints on protein and PI(3,5)P2 heavy atoms.

Next to coarse-grained equilibrium simulations of the wild-type hTPC2 protein, we performed further 1 µs long simulations of 5 mutated variants: K203Q, K204D–K207V, S322Q, T325Q, and L327D. To ensure specificity in binding, we set the PI(3,5)P2 lipid concentration to 1%. Since AtTPC1 is not activated by PI(3,5)P2 [11], the mutants were chosen by either referring to the sequence of the plant channel (Fig. 4) or to reduce the number of positive surface charges. Starting structures were generated by replacing the wild-type hTPC2 protein in the starting system described above (1% PIP) with the individual mutants. Three replica simulations of each mutant were conducted resulting in 15 mutant simulations (1 µs each).

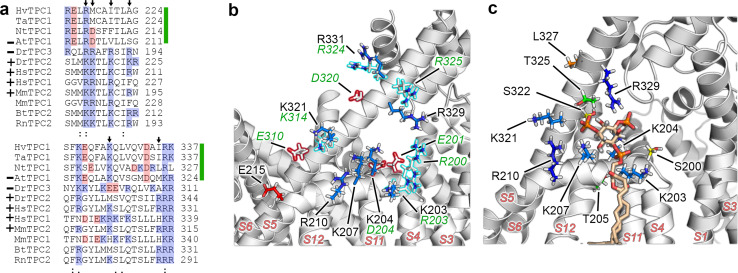

Fig. 4.

In hTPC2, the S4-S5 linker and S6ext constitute a binding pocket for PI(3,5)P2. a Sequence alignment of the S4-S5 linker (top) and S6ext (bottom) between several plant (upper green bars) and animal (unmarked) TPCs. Different TPC isoforms which were shown to be activated by PI(3,5)P2 lipids are marked with ‘+’, ‘–’ indicates channels which are not regulated by PI(3,5)P2 lipids [5, 7, 11, 16, 62]. Basic and acidic residues are highlighted in blue and red, respectively. Arrows indicate charged residues of hTPC2 important for lipid-binding (K203, K204, K207, R210 and K321, R329). The pairwise sequence alignment of the whole AtTPC1 and hTPC2 sequences is given in Supplemental Fig. 1a. Hv Hordeum vulgare, Ta Triticum aestivum, Nt Nicotiana tabacum, At Arabidopsis thaliana, Dr Danio rerio, Hs Homo sapiens, Mm Mus musculus, Bt Bos taurus, Rn Rattus norvegicus. b Structural comparison between charged residues of hTPC2 (filled) and AtTPC1 (outlined). Positively charged arginines and lysines are coloured in blue, negatively charged glutamic and aspartic residues in red. Amino acids written in green correspond to AtTPC1. c Snapshot (t = 80 ns) of an atomistic simulation showing PI(3,5)P2 bound to hTPC2 (light brown). Phosphate atoms are represented in orange, oxygens in red and hydrogens in white, lysines in light blue, arginines in dark blue, threonines in green, serines in yellow, and leucine in orange. For clarity, the S3 helix and surrounding water and the membrane is hidden in b and c

In summary, each of the 27 simulation systems of AtTPC1, wild type and mutant hTPC2 proteins consisted of ~ 74,000 coarse grained particles and was simulated for 1 µs.

Simulation details

All coarse-grained simulations were carried out using the GROMACS 4.6.x package [39]. Since we expected that electrostatic effects play an important role in the study of binding of the highly negatively charged PI(3,5)P2 lipid to the human and plant TPC, respectively, we chose the polarizable version (2.2) of the coarse-grained MARTINI force field [34, 36]. Long-range electrostatics was considered using the particle-mesh Ewald method [40] with a real space cutoff of 1.2 nm and a relative dielectric constant of 2.5. Van der Waals forces were described by a Lennard-Jones 12-6 potential and decayed smoothly to zero between 0.9 nm to 1.2 nm. The temperature was maintained at 310 K by rescaling of velocities with a time constant of 1 ps [41]. The pressure was coupled semi-isotropically to 1 bar using the Berendsen algorithm (τp = 1 ps) [42]. In all coarse-grained production run simulations the integration time step was reduced from a standard value of 20 fs to 10 fs required to ensure (numerical) stability of the PI(3,5)P2 lipids.

The MARTINI lipid DPP2 with a total charge of – 5 e served as coarse-grained model for the phosphoinositol molecule (Supplemental Fig. 2) [43]. Originally, parameters for this lipid were generated based on the PI(3,4)P2 head group; however, due to the coarsened structure PI(3,4)P2 and PI(3,5)P2, lipids are virtually indistinguishable. The original parameters by López et al. [43] were employed (including the dihedral parameters for C3–C1–CP–GL1 and the default MARTINI angle parameters [44] for CP–GL1–GL2 and CP–GL1–C1A).

The ordered protein structure was preserved by applying an elastic network with a distance-dependent force of 500 kJ mol−1 nm−2 between all backbone beads within a distance of 0.9 nm.

Two atomistic simulations (each 500 ns) were conducted in GROMACS 5.0.x [45] in combination with the CHARMM36 force field [46–49] of hTPC2 in a pure phosphatidylcholine lipid bilayer and with 1% PI(3,5)P2. For the latter simulation, a starting structure was prepared from an equilibrated simulation at coarse-grained resolution (see above). The atomistic simulation systems contained ~ 300,000 atoms. Simulation parameters were equivalent to those described previously [50], except that the temperature was coupled to 310 K with the v-rescale thermostat [41].

Data analysis

Binding of PI(3,5)P2 lipids to the individual channels was evaluated by calculating the number of contacts between the three phosphate beads in the lipid head group and the protein over time. A contact was counted if a bead was within a distance of 0.65 nm to the protein, such that a maximum number of 24 and 48 contacts in the simulations with 8 and 16 PI(3,5)P2 molecules, respectively, were possible in each frame. The data were normalized to obtain an overview of lipid molecules binding to the channel. The distance criterion was obtained by calculating the radial distribution function of phosphate beads around the protein.

The PI(3,5)P2 lipid occupancy of single residues in the CG simulations was calculated as an average over the last 500 ns of each simulation and subunit, in which at least one of the three phosphate beads was within a distance of 0.65 nm to the protein. Median minimal distances between pocket-bound PI(3,5)P2 lipids and residues in the binding pocket were calculated over the last 300 ns of wild type and mutant simulations. To increase the statistics, data of the wild-type simulations with 1 and 2% PI(3,5)P2 concentrations were combined.

The root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) was calculated for PI(3,5)P2 lipid head groups after least square fitting the transmembrane backbone beads of the protein. For the wild-type hTPC2 simulations, the RMSF was calculated separately for three groups, namely, PI(3,5)P2 lipids that bound to the binding pocket at the S4/5-linker and extended S6 helix, the binding site at the C-terminal end of S12 and the remaining binding sites. The calculation was done separately for each group for both PI(3,5)P2 concentrations and averaged over the last 300 ns (split into 50 ns windows for error estimation). For the mutant simulations, RMSF values were only calculated for PI(3,5)P2 lipids bound to the binding pocket of the respective mutant.

The multiple sequence alignment was obtained via the online program Clustal Omega [51]. Sequences of TPC isoforms were downloaded from the UniProt database with the following accession numbers: AtTPC1 (Q94KI8), BtTPC2 (E1BIB9), DrTPC2 (A0JMD4), DrTPC3 (C4IXV6), HsTPC1 (Q9ULQ1), HsTPC2 (Q8NHX9), HvTPC1 (Q6S5H8), MmTPC1 (Q9EQJ0), MmTPC2 (Q8BWC0), NtTPC1 (Q75VR1), RnTPC2 (D3ZTJ6), and TaTPC1 (Q6YLX9).

The electrostatic surface potential for hTPC2 and AtTPC1 in an implicit membrane was calculated using our recently developed program GroPBS [52, 53] for the numerical solution of the Poisson–Boltzmann equation in membrane environments. Parameters were chosen according to refs, [52, 53], i.e., a filling rate of 80% was used with a grid spacing of 0.5 Å. Furthermore, we used periodic boundaries in x and y dimensions and quasi-Coulombic dipole conditions in z-direction. The dielectric constant was set to 80 in water, 4 inside the proteins, and 2 in the membrane [54]. A temperature of 298 K was used to mimic laboratory conditions and a physiological salt concentration of 150 mM was adjusted. The Poisson–Boltzmann equation was solved for the completed and energy-minimized crystal structure of AtTPC1 (see above) and the model hTPC2 structure.

Generation of hTPC2 mutants

The hTPC2-coding sequence in pSAT6–EFGP–N1 [55] was used as template for Quick change mutagenesis (QCM) (QuickChange II Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit by Agilent) using a modified version of the SPRINP mutagenesis protocol [56]. Forward and reverse primers were: aactcctctatgatgcagaagaccttgaaatgc and gcatttcaaggtcttctgcatcata gaggagtt for K203Q; tcctctatgatgaaggacaccttgaaatgcatc and gatgcatttcaaggtgtccttcatcatagagga for K204D as well as tcctctatgatgaaggacaccttggtatgcatc and gatgcataccaaggtgtccttcatcatagagga for K204D–K207V; tctatgatgaagaaggacttgaaatgcatccgc and gcggatgcatttcaagtccttcttcatcataga for T205D; ggctacctgatgaaacaactccagacctcgctg and cagcgaggtctggagttgtttcatcaggtagcc for S322Q; atgaaatctctccagcagtcgctgtttcggagg and cctccgaaacagcgactgctggagagatttcat for T325Q; tctctccagacctcggactttcggaggcggctg and cagccgcctccgaaagtccgaggtctggagaga for L327D, respectively.

Plant material, protoplast isolation, and transfection

Arabidopsis thaliana plants lacking the TPC1 gene (tpc1-2) [57] were grown on soil at 22 °C in a growth chamber under short day (8 h) conditions. Five-to-seven-week-old plants were used for mesophyll protoplast isolation and transfection, using 30 µg plasmid DNA and 150 µl protoplast suspension at a density of 2·104 cells µl−1, as described [22, 58]. The protoplast solution was kept at 22 °C in darkness in W5 buffer [22] containing ampicillin (100 µg/ml) and gentamycin (25 µg/ml) for 3 days before electrophysiological assessment, and stored at 4 °C for up to 7 days after transfection.

Patch-clamp recordings and data analysis

Individual mesophyll cells showing EGFP fluorescence were lysed by superfusion with VR solution (100 mM malic acid, 160 mM 1,3-bis(tris(hydroxymethyl)methylamino)propane (BTP), 5 mM EGTA, 3 mM MgCl2, pH7.5 (BTP), 450 mOsm with D-sorbitol) via a glass capillary containing a large tip-opening and application of gentle positive pressure [59]. Release of the intact vacuole was observed and vacuolar EGFP fluorescence was confirmed before electrophysiological recordings. For patch-clamp measurement, the pipette solution (luminal side) contained 200 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 10 mM MES, pH 5.5 (NaOH), 550 mOsm with 155 mM D-sorbitol. The bath solution (cytoplasmic side) contained 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.5 (NaOH), and 600 mOsm with 365 mM D-sorbitol. 2 mM Dithiothreitol (DTT) was added to the bath solution prior to each experiment. A soluble form of PI(3,5)P2, PI(3,5)P2 diC8 (dioctanyl ester) was purchased from Echelon Bioscience Inc., solved in ddH2O to a stock solution of 1 mM, shock frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at − 20 °C. Other chemicals were purchased in the highest purity from Carl Roth or Sigma-Aldrich. Whole-vacuolar current recordings were performed using a patch-clamp amplifier (EPC-10) connected to a PC running FitMaster (HEKA electronics, Lambrecht, Germany) as described [22, 58]. Currents were measured during 1 s voltage ramps from + 40 to − 40 mV before and after the addition of PI(3,5)P2-diC8 to the bath solution, as well as after removal of the lipid (Supplemental Fig. 6). For assessment of half-maximum activation, steady-state currents at − 40 mV were used. Background currents in the absence of PI(3,5)P2-diC8 were subtracted before further data analysis. The half-maximum activation concentration was determined by a Hill-fit to individual measurements and averaged from 3 to 7 individual experiments, using the IGOR Pro software (Wavemetrics, Inc.) Images were prepared using IGOR Pro, Adobe Photoshop, and Adobe Illustrator.

Confocal microscopy

Fluorescence and bright field images of protoplasts were taken with a Leica TCS SP5 confocal laser-scanning microscope (Leica Microsystems). The fluorescence of EGFP and the auto-fluorescence of chlorophyll were excited with a 488 nm 20 mW Argon laser und detected in a range from 500 to 556 nm and from 653 to 767 nm, respectively. Images were obtained with the Leica Confocal Software and processed using Adobe® Photoshop®.

Results

Differential PI(3,5)P2 lipid-binding to the human and plant TPC channel

Protein–lipid interactions were addressed in coarse-grained (CG) MD simulations of the PI(3,5)P2-gated human TPC2 in comparison with the PI(3,5)P2-insensitive Arabidopsis TPC1. To this end, an atomistic homology model of hTPC2 in its closed conformation was built, using the structure of AtTPC1 as a template. Similar to the plant channel, the topology of hTPC2 is characterized by an unusually long S6 helix (S6ext), extending into the cytosol (Fig. 1), which was shown to be involved in the gating of AtTPC1.

The CG starting structures contained either hTPC2 or AtTPC1 embedded in a POPC membrane at a total concentration of 1 or 2% PI(3,5)P2 lipids, randomly distributed in the cytosolic leaflet. During the production run simulations (each setup repeated three times, in total 12 CG simulations, each 1 µs), the lipids were free to diffuse within the POPC membrane. To avoid any bias, the starting conditions, i.e., in particular the lipid distribution, were chosen similarly for both hTPC2 and AtTPC1. Figure 2 illustrates the binding tendency of PI(3,5)P2 to hTPC2 (red tones) and AtTPC1 (green tones), respectively. During 1 µs of unconstrained MD runs, the number of contacts between the proteins and PI(3,5)P2 lipids converged within the initial 500 ns (Fig. 2a). The amount of PI(3,5)P2 molecules in contact to hTPC2 was almost twice as high as compared to the plant protein. At least six PI(3,5)P2 molecules bound to hTPC2 in the course of the simulations, which represents 75% (37.5%) of the total amount of PI(3,5)P2 lipids in the 1% (2%) simulations. In contrast, a significantly decreased PI(3,5)P2-binding propensity was found for TPC1 compared to hTPC2. A representative final snapshot of one of the simulations for each TPC isoform was subsequently backmapped to atomistic resolution, illustrating the different lipid occupancy between hTPC2 and AtTPC1 (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Binding tendency of PI(3,5)P2 lipids is higher towards hTPC2 as compared to AtTPC1. a Number of contacts between all PI(3,5)P2 molecules and the human (red lines) and plant (green lines) TPC for simulations at a total PI(3,5)P2 concentration of 1% (corresponding to 8 PI(3,5)P2 lipids, top panel) and 2% (16 PI(3,5)P2 lipids, bottom panel). Individual lines represent independently performed simulations. b Side and cytosolic view of example protein–PI(3,5)P2 complexes that formed in one of the CG simulations (t = 1 µs). Individual subunits of hTPC2 (top) are coloured in a red–white gradient from the N- to the C-terminus, AtTPC1 (bottom) subunits in a green–white gradient. S1′–S12′ and S1″–S12″ indicate the two TPC subunits of the homo-dimer. Bound PI(3,5)P2 molecules are represented in blue sticks with phosphate and oxygen atoms highlighted in orange and white, the membrane is coloured in brown (cytosolic side at the top). For clarity, coarse-grained structures were converted to atomistic representation and surrounding water molecules as well as hydrogen atoms omitted

The S4–S5 linker and S6ext form a PI(3,5)P2-binding pocket in hTPC2

Independent of their concentration, PI(3,5)P2 lipids predominately interacted via their fivefold negatively charged head group with positively charged amino acids of the two TPC isoforms (Fig. 3). In hTPC2, the main PI(3,5)P2-binding contacts were built by the cytosolic S4–S5 linker (residues 200–211) and the cytosolic region (residues 314–331) of the extended S6 helix, which together formed a lipid-binding pocket. Comparison of the PI(3,5)P2 occupancy of the respective homologous regions of hTPC2 and AtTPC1 showed that neither the S4–S5 helix nor S6ext are in contact with PI(3,5)P2 in the plant TPC1 (Figs. 2b, 3). In addition, PI(3,5)P2 lipids preferentially interacted with K700 and R704 at the C-terminal end of S12 of hTPC2 (Fig. 3). At a significantly decreased occupancy as compared to the binding pocket, lateral binding of PI(3,5)P2 was observed to the cytosolic regions of S1, S7, and the S2–S3 linker of hTPC2, and to the space between the two domains encompassing S1–S4 and S7–S10. In comparison, contacts between PI(3,5)P2 and AtTPC1 were mainly generated with R62 in the N-terminal domain and R145 of the S2–S3 helix, as well as with a cluster of five residues at the pre-S7 helix (Figs. 2b, 3). As most of them are located at the outer surface of the channel and AtTPC1 activity is not regulated by PI(3,5)P2 [11], a physiological role of these interactions appears unlikely.

Fig. 3.

PI(3,5)P2-binding sites differ significantly for hTPC2 (top) and AtTPC1 (bottom). Upper and lower panel: the occupancy of individual residues by PI(3,5)P2 lipids over the last 500 ns is coloured in rainbow from blue, 0% occupied, to red, 100% occupied. The membrane is indicated in brown. S1′–S12′ and S1″–S12″ indicate the two TPC subunits of the homo-dimer. For clarity, the atomistic protein structure is shown. Protein orientation as in Fig. 2. Middle panel: occupancies of residues in regions involved in PI(3,5)P2-binding. Upper red bars correspond to residues of hTPC2, lower green bars to residues at locally equivalent positions of AtTPC1

The observed differences in the PI(3,5)P2-binding behaviour of the human and plant TPC are most probably linked to the presence of negatively charged residues and the absence of positively charged residues at the respective positions in AtTPC1 (Fig. 4 and Supplemental Fig. 3). The S4–S5 linker of the human channel and its related TPC2 isoforms in other species as well contain three lysines at the positions corresponding to 203, 204, and 207 in hTPC2 and another basic residue (R210) at position 210, whereas homologous positions in Arabidopsis and other plant TPCs are occupied by one basic, and acidic or neutral residues, respectively (Fig. 4a). Similarly, S6ext in AtTPC1 misses an arginine, which is pointing towards the binding pocket in hTPC2 (R329), and contains another negatively charged residue (D) at position 320 (L327 in hTPC2; Fig. 4b, c). At the C-terminal end of S12, the number of acidic residues (poly-E) prevails in the plant channel. Accordingly, the electrostatic surface potential differs significantly between the mammalian and plant TPC for the above-described regions (Supplemental Fig. 3), explaining the drastically reduced probability of PI(3,5)P2-binding to these regions in the plant channel.

In the hTPC2 simulations, PI(3,5)P2 approached the lipid-binding pocket at the S4–S5 linker and S6ext, either by direct binding to the pocket or by first interacting with residues 151–154 (K154) of the S2–S3 linker located laterally in front of the binding pocket. Typically, several residues interacted simultaneously with the three phosphate beads of PI(3,5)P2 in the pocket, including K203, K204, K207, and R210 from the S4–S5 linker and Y318, K321, S322, T325, S326, and R329 from S6ext. An equivalent binding behaviour was observed in a 500 ns long atomistic MD simulation that served for validation of the CG results (Fig. 4c). In addition, a second PI(3,5)P2 molecule interacted with K154 within the S2–S3 linker in front of the pocket (compare Figs. 2b and 3). A comparison of the root mean square fluctuations (RMSF) of bound PI(3,5)P2 molecules suggested a more tight binding of PI(3,5)P2 in the presumed lipid-binding pocket than at the remaining sites where binding is rather flexible (Supplemental Fig. 4a). The median and interquartile range (IQR) of the RMSF of the pocket-bound PI(3,5)P2 lipid head groups accounted for 1.20 Å and 0.44 Å, while the fluctuation was slightly increased for S12-bound groups (median: 1.46 Å, IQR: 0.67 Å) and remaining bound PI(3,5)P2 head groups (median: 2.44 Å, IQR: 1.59 Å).

In summary, the binding tendency and binding sites of TPCs towards the fivefold negatively charged PI(3,5)P2 lipids differed significantly between the human and plant TPC homologues. Binding to hTPC2 is favoured by the presence of several positively charged residues in the S4–S5 linker and S6ext that are accessible to PI(3,5)P2. Besides this lipid-binding pocket, PI(3,5)P2 lipids preferentially interacted with K700 and R704 at the C-terminal end of S12.

Mutations within the PI(3,5)P2-binding pocket decrease lipid sensitivity of hTPC2

To verify the importance of the identified lipid-binding pocket and to investigate the impact of individual residues for PI(3,5)P2-dependent activation, electrophysiological recordings and CG simulations of hTPC2 channels carrying mutations within the S4–S5 linker and S6ext were performed. Introduction of point mutations (K203Q, K204D–K207V, S322Q, T325Q, and L327D) did not prevent PI(3,5)P2 molecules from binding to the protein during CG simulations (Supplemental Fig. 5), and lipid-binding to the modified binding pockets occurred to a similar extent as for the wild type. However, some mutations induced significant changes in the lipid-binding profile (see below) and significantly affected the channel activity in patch-clamp experiments.

Expression of mammalian TPC2 in Arabidopsis thaliana leads to a sorting of the channel to the membrane of the vacuole, which represents the acidic organelle in plant cells, equivalent to the lysosome [58]. For functional analyses, wild type and mutant channels were expressed as a GFP fusion in mesophyll cells of the Arabidopsis tpc1-2 knockout mutant lacking any endogenous TPC1 currents (Supplemental Fig. 6). The C-terminal GFP-tag was used to verify expression and correct targeting of the hTPC2 variants to the vacuolar membrane, which was selected for subsequent patch-clamp recordings (Fig. 5; Supplemental Fig. 6). Addition of soluble PI(3,5)P2-diC8 (hereafter: PI(3,5)P2) to the cytosolic side of the membrane elicited dose-dependent inward and outward Na+ currents in hTPC2–GFP expressing cells, as expected for the voltage-independent, lipid-gated channel [5, 11]. hTPC2 currents were induced in bath solutions containing PI(3,5)P2 with a half-maximum activation at 48 ± 10 nM (n = 7), and reversed upon removal of the lipid (Fig. 5a and Supplemental Fig. 6).

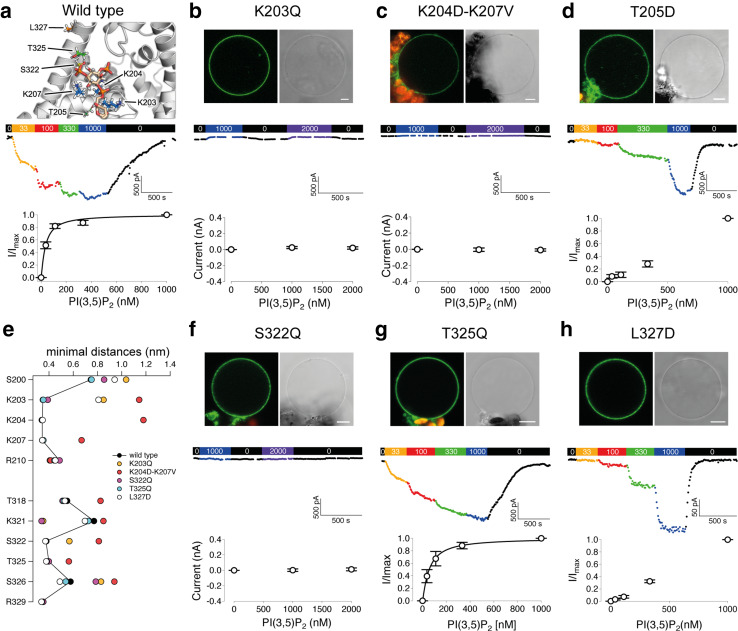

Fig. 5.

PI(3,5)P2-sensitivity of hTPC2 mutants. a Top: Illustration of residues in the PI(3,5)P2-binding pocket, which were point mutated. The bound PI(3,5)P2 molecule is shown in sticks. Colour coding according to Fig. 4. b–d, f–h Upper panels: Confocal fluorescence overlay images of the GFP (green) and chlorophyll (red) signals (scales represent 5 µm) and bright field images of hTPC2–GFP variants expressed in mesophyll cells of the Arabidopsis tpc1-2 mutant. Vacuoles were released from the intact cells prior to imaging. a–d, f–h Middle panels: Current–time diagram of PI(3,5)P2-dependent whole-vacuolar currents at − 40 mV. PI(3,5)P2-diC8 concentration in the bath solution was 0 nM (black), 33 nM (orange), 100 nM (red), 330 nM (green), 1000 nM (blue) as indicated by the colour bar at the top. a–d, f–h Bottom panels: Dose–response curves of PI(3,5)P2-dependent currents at − 40 mV for hTPC2 (a), n = 7, hTPC2–T205D (d), n = 7, hTPC2–T325Q (g), n = 4, and hTPC2–L327D (h), n = 4. Currents were normalized to the value in the presence of 1000 nM PI(3,5)P2 (I/Imax). Lines represent fits according to the Hill equation with n = 1.15 For the silent channels hTPC2–K203Q (b), K204D–K207V (c), and S322Q (f), current amplitudes were plotted as a function of the PI(3,5)P2 concentration (n = 5, 4, and 3, respectively). Data represent mean ± s.e.m. e Median minimal distances between PI(3,5)P2 lipids bound in the binding pocket and residues from the wild type and mutant simulations. Distances are only shown for those residues where PI(3,5)P2 molecules were closer than 0.8 nm for at least one protein variant. Note that the sequence (y-axis) is given for the wild type

Mutations within the polybasic patch of positively charged amino acids in the S4–S5 linker (Fig. 5a) completely prevented PI(3,5)P2-induced currents: cells expressing hTPC2–K203Q or hTPC2–K204D/K207 V did not respond to PI(3,5)P2 (Fig. 5b, c), similar to tpc1–2 control cells (Supplemental Fig. 6). These findings are in agreement with the close proximity of the respective wild-type residues to the negatively charged lipid phosphates in the binding pocket, to which they form salt bridges (Figs. 4c, 5a). The distances of PI(3,5)P2 to the mutated residues, as well as to the other residues involved in lipid-binding were increased in the CG mutant simulations indicating that the binding profile changed for the hTPC2–K203Q and hTPC2–K204D/K207V mutants (Fig. 5e). Furthermore, the distance between PI(3,5)P2 and S200 of the S4–S5 linker, which had no direct contact to the lipid in the wild type (Fig. 4c) increased when positive charges of the binding pocket were removed. The effects on the distance were stronger, when two charges were removed compared to a single mutant, reflecting the additive effect of multiple salt bridges for tight PI(3,5)P2-binding. In addition, PI(3,5)P2 molecules that bound into the pocket of the K204D–K207V mutant showed a slightly increased median RMSF of 1.68 Å (IQR: 0.69 Å) as compared to the wild-type channel (1.20 Å, IQR: 0.44) and the other mutants (0.96–1.17 Å), indicating a less stable binding (Supplemental Fig. 4b). However, elimination of one positively charged binding residue was sufficient to prevent PI(3,5)P2-dependent channel activity.

Another mutant (T205D), inserting a negative charge within the S4–S5 linker, was designed to further investigate the interaction between the lipid head group and the binding pocket (Fig. 5d). Application of 33 nM PI(3,5)P2 induced only minor currents at − 40 mV, which did not saturate at concentrations up to 1000 nM, revealing a shift of the sensitivity towards higher lipid concentrations in hTPC2–T205D compared to the wild-type channel. Removal of PI(3,5)P2 resulted in a swift decay of the current (Fig. 5d). Thus, although T205 established no direct contact to PI(3,5)P2 in MD wild-type simulations and points away from the binding pocket (Fig. 5a), introduction of a negative charge at this position was sufficient to reduce the lipid-binding affinity to the micromolar range, most likely by electrostatic repulsion of approaching lipids. Similarly, when a negative charge was introduced into S6ext at L327, which also had no direct contact to the bound lipid (Fig. 5a), the PI(3,5)P2-sensitivity of hTPC2–L327D was significantly reduced compared to the wild type (Fig. 5h). Upon an increase from 330 nM to 1000 nM PI(3,5)P2, the recorded currents almost linearly increased by ~ 60%. In the CG simulations, the L327D mutation had a more locally restricted influence on PI(3,5)P2-binding, resulting in an increased distance of the lipid to K203 and S200 (Fig. 5e and Supplemental Fig. 5). Apparently, introduction of a negative charge into the S6ext helix in the vicinity of the ligand had a similar effect on the PI(3,5)P2-sensitivity of the channel as compared to the introduction of a negative charge into the S4-S5 linker. While the T205D mutation likely alters the PI(3,5)P2-sensitivity solely due to electrostatic repulsions, the L327D mutation may additionally destabilize hydrophobic interaction and induce the formation of new salt bridges between S6ext and a helical region of the N-terminal domain, which is essential for channel function [10, 58].

Two polar residues (S322 and T325) in S6ext established direct PI(3,5)P2 contacts during MD simulations (Fig. 3). Increasing the size of the polar side chain at position 322 (S322Q) abolished PI(3,5)P2-activation (Fig. 5f). In the CG simulations, the latter mutation slightly shifted the binding position towards K321 and away from S326 (Fig. 5e). In comparison, the T325Q mutation did not significantly influence PI(3,5)P2-binding. Among all mutants tested, hTPC2–T325Q behaved most similar to the wild-type channel in CG simulations (Supplemental Fig. 4), and no alterations in the lipid–protein profile were observed (Fig. 5e). This is in perfect agreement with the wild-type like PI(3,5)P2-sensitivity of the mutant in functional studies (Fig. 5g). The dose–response curve revealed a PI(3,5)P2-affinity of 84 ± 34 nM (n = 4), well within the concentration range as determined for the wild type.

Taken together, the results from site-directed mutagenesis and functional analysis of hTPC2 mutants after expression in plant cells suggest electrostatic interactions as the main driving force for binding of PI(3,5)P2 preceding channel opening, and identified essential roles of positive charges in the S4–S5 linker and of residues in the extended S6 helix for PI(3,5)P2-dependent activity of the channel. CG simulations showed a significant change of the protein–lipid interface upon mutations of residues within the lipid-binding pocket that establish a direct contact with PI(3,5)P2, except for T325Q which had neither an effect on the binding behaviour nor on the channel’s lipid sensitivity.

Discussion

Due to limited structural information, lipid-binding to target proteins is not well understood, although phosphatidylinositol-derived lipids have been shown as essential functional elements of an increasing set of ion channels [1–3]. This study provides the first identification of a binding pocket in an ion channel of the TPC family for the anionic signalling lipid PI(3,5)P2, which is present in internal membranes of the endo-lysosomal system. So far, there is only one further example known on the molecular level of where PI(3,5)P2 binds to an ion channel in this compartment: The mucolipin TRPML1 channel possesses a polybasic region at the N-terminus that was shown to represent the binding and activation site for PI(3,5)P2 [60], which was subsequently used to design the first fluorescent reporter for in vivo localization of this phosphoinositide [61]. In contrast, in hTPC2, the S4–S5 linker and the cytosolic helical extension of S6 mutually build a lipid-binding pocket, as evidenced by coarse-grained and atomistic MD simulations. In the three-dimensional protein conformation of the closed channel, these two helices adopt a relative orientation, such that four basic residues of the S4–S5 linker (K203, K204, K207, and R210) and two residues of S6ext (K321 and R329) establish spatial proximity, thus forming a positively charged binding pocket for PI(3,5)P2 lipids. Besides electrostatic interactions with the head group, lipid tails established hydrophobic contacts with the transmembrane helices (S4, S11, and S12, Fig. 4c), further stabilizing the orientation of the inositol head group towards the negatively charged lipid-binding pocket.

Site-directed mutagenesis of lysines of the S4–S5 linker to neutral and acidic residues entirely suppressed PI(3,5)P2-evoked currents in patch-clamp experiments, supporting the conclusion that electrostatic interactions play a crucial role in hTPC2 activation by PI(3,5)P2. Despite these convergent lines of evidence, we cannot completely exclude the possibility that some of these mutations may have affected channel functions other than direct lipid-binding. Introduction of negatively charged residues in proximity to the binding pocket (T205D, L327D) significantly shifted the sensitivity of the channel to increased PI(3,5)P2 levels, which further points towards the importance of (long-ranged) electrostatic interactions. Interestingly, and in striking accordance with the insensitivity of AtTPC1 to PI(3,5)P2 [11], not a single PI(3,5)P2 molecule bound to the equivalent site of the plant channel in the performed MD simulations. A sequence alignment of the S4–S5 linker and S6ext between TPCs of different species known to be activated by PI(3,5)P2 [5–8, 11, 16] shows that these channels share similarities with respect to the presence of basic and absence of acidic residues (Fig. 4a). These TPCs possess arginines or lysines at the respective positions corresponding to 203, 204, and 207 in hTPC2. In addition, they have conserved positively charged or neutral residues in S6ext that in hTPC2 point into the binding pocket (residue K321, S322, and R329, Fig. 4a). In contrast, proteins such as AtTPC1 and DrTPC3, known to be insensitive for PI(3,5)P2 [11, 62], partially lack these basic residues and instead contain acidic or neutral residues in the S4–S5 linker (AtTPC1, Fig. 4b) or in S6ext (DrTPC3). This strongly suggests that lipid-sensitive TPC1 and TPC2 isoforms share a principle mechanism to link lipid-binding to channel gating, and can be separated from lipid-insensitive TPCs on the basis of their electrostatic potential of the binding pocket. Although knowledge about the mechanisms of PI(3,5)P2-binding to target proteins is still very limited, this study supports the model, in which PIP lipids in general exert their effects mainly via electrostatic interactions between the charged lipid head group and positively charged protein sites [2].

While the gating mechanism of hTPC2 remains unknown, a model on how the plant TPC1 is activated in a Ca2+- and voltage-dependent manner was developed on the basis of structural information [9, 10]. Ca2+-binding to the EF-hand domain encompassing part of S6ext induces pore opening by triggering the concerted upward movement of the S4–S5 linker and S6, whereas membrane depolarization is sensed by the second Shaker-like domain, which evokes a similar movement of the S10–S11 linker and S12 [10]. Since hTPC2 lacks Ca2+-binding EF-hands and is not voltage-dependent, binding of PI(3,5)P2 lipids to the lipid-binding pocket of the first Shaker-like domain may induce similar concerted motions within the hTPC2 protein that result in channel opening. A role of S12 in lipid-binding and corresponding conformational changes of the second Shaker-like domain may also be possible as lipid interactions with S12 have been observed in MD simulations.

Besides triggering conformational changes, ligand-binding might as well stabilize the channel in the open conformation. However, the artificial rigidity in terms of secondary and tertiary structure in the MARTINI model does not allow the study of protein conformational changes during coarse-grained simulations. In atomistic simulations on the 500 ns timescale we could not observe channel opening neither of PI(3,5)P2 bound hTPC2 nor of pure hTPC2 (data not shown).

Compared to PI(3,5)P2 lipids in membranes of the endo-lysosomal compartment, many more targets have been studied for the plasma membrane lipid PI(4,5)P2, and structural information of PI(4,5)P2 bound to the inward-rectifying potassium channels Kir2.2 and Kir3.2 has been reported [63, 64]. MD simulations of PI(4,5)P2-sensitive Shaker-like voltage-gated potassium channels (Kv) revealed the S4-S5 linker as lipid-binding site, similar to hTPC2 [65, 66]. It appears, that the S4-S5 linker in PIP-dependent channels represents a common structural element responsible for coupling lipid-binding and conformational changes in the pore domain.

Taken together, the hitherto unknown PI(3,5)P2-binding site in hTPC2 identified in this study fits perfectly well into the apparently evolutionarily conserved feature of PIP acting as a bidentate ligand cross-linking two parts of the channel to favour the open conformation by binding to a positively charged spot and a concomitant channel activation [3]. Our study provides a framework for future research towards the understanding of conserved and isoform-specific mechanisms of ligand- and voltage activation of two-pore channels.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Research Training Group 1962 (to RAB and PD) from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and by 2015795S5W funding to AC from the Italian Ministry of Education, University and Research. We would like to thank Joachim Scholz-Starke and Margherita Festa (Genova) for supervision of AK during part of his experiments.

Abbreviations

- PI(3,5)P2

Phosphatidylinositol-(3,5)-bisphosphate

- POPC

1-Palmitoyl-2-oleoyl phosphatidylcholine

- MD

Molecular dynamics

- CG

Coarse-grained

Author contributions

RAB and PD designed and directed research of the simulations and functional analysis, respectively. SAK set up the homology model, and performed CG and atomistic simulations and the related analysis. AK performed cloning, site-directed mutagenesis, functional expression and patch-clamp analysis in plant vacuoles and analyzed the data; AC hosted AK during a laboratory stay to conduct part of the experiments and helped analyzing the data. SAK, PD, RAB, AK, and AC wrote the manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Sonja A. Kirsch and Andreas Kugemann contributed equally.

Contributor Information

Rainer A. Böckmann, Email: rainer.boeckmann@fau.de

Petra Dietrich, Phone: 0049-9131-8525208, Email: petra.dietrich@fau.de.

References

- 1.Hansen SB. Lipid agonism: the PIP2 paradigm of ligand-gated ion channels. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1851(5):620–628. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2015.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suh BC, Hille B. PIP2 is a necessary cofactor for ion channel function: how and why? Annu Rev Biophys. 2008;37:175–195. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hille B, Dickson EJ, Kruse M, Vivas O. Suh BC (2015) Phosphoinositides regulate ion channels. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1851;6:844–856. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2014.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diaz-Franulic I, Poblete H, Mino-Galaz G, Gonzalez C, Latorre R. Allosterism and structure in thermally activated transient receptor potential channels. Annu Rev Biophys. 2016;45:371–398. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-062215-011034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang X, Zhang X, Dong XP, Samie M, Li X, Cheng X, Goschka A, Shen D, Zhou Y, Harlow J, Zhu MX, Clapham DE, Ren D, Xu H. TPC proteins are phosphoinositide- activated sodium-selective ion channels in endosomes and lysosomes. Cell. 2012;151(2):372–383. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cang C, Zhou Y, Navarro B, Seo YJ, Aranda K, Shi L, Battaglia-Hsu S, Nissim I, Clapham DE, Ren D. mTOR regulates lysosomal ATP-sensitive two-pore Na(+) channels to adapt to metabolic state. Cell. 2013;152(4):778–790. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cang C, Bekele B, Ren D. The voltage-gated sodium channel TPC1 confers endolysosomal excitability. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10(6):463–469. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lagostena L, Festa M, Pusch M, Carpaneto A. The human two-pore channel 1 is modulated by cytosolic and luminal calcium. Sci Rep. 2017;7:43900. doi: 10.1038/srep43900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kintzer AF, Stroud RM. Structure, inhibition and regulation of two-pore channel TPC1 from Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature. 2016;531(7593):258–262. doi: 10.1038/nature17194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guo J, Zeng W, Chen Q, Lee C, Chen L, Yang Y, Cang C, Ren D, Jiang Y. Structure of the voltage-gated two-pore channel TPC1 from Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature. 2016;531(7593):196–201. doi: 10.1038/nature16446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boccaccio A, Scholz-Starke J, Hamamoto S, Larisch N, Festa M, Gutla PV, Costa A, Dietrich P, Uozumi N, Carpaneto A. The phosphoinositide PI(3,5)P2 mediates activation of mammalian but not plant TPC proteins: functional expression of endolysosomal channels in yeast and plant cells. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2014;71(21):4275–4283. doi: 10.1007/s00018-014-1623-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peiter E, Maathuis FJ, Mills LN, Knight H, Pelloux J, Hetherington AM, Sanders D. The vacuolar Ca2+-activated channel TPC1 regulates germination and stomatal movement. Nature. 2005;434(7031):404–408. doi: 10.1038/nature03381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calcraft PJ, Ruas M, Pan Z, Cheng X, Arredouani A, Hao X, Tang J, Rietdorf K, Teboul L, Chuang KT, Lin P, Xiao R, Wang C, Zhu Y, Lin Y, Wyatt CN, Parrington J, Ma J, Evans AM, Galione A, Zhu MX. NAADP mobilizes calcium from acidic organelles through two-pore channels. Nature. 2009;459(7246):596–600. doi: 10.1038/nature08030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu H, Ren D. Lysosomal physiology. Annu Rev Physiol. 2015;77:57–80. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021014-071649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Favia A, Desideri M, Gambara G, D’Alessio A, Ruas M, Esposito B, Del Bufalo D, Parrington J, Ziparo E, Palombi F, Galione A, Filippini A. VEGF-induced neoangiogenesis is mediated by NAADP and two-pore channel-2-dependent Ca2 + signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(44):E4706–E4715. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1406029111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grimm C, Holdt LM, Chen CC, Hassan S, Müler C, Jörs S, Cuny H, Kissing S, Schröder B, Butz E, Northoff B, Castonguay J, Luber CA, Moser M, Spahn S, Lüllmann-Rauch R, Fendel C, Klugbauer N, Griesbeck O, Haas A, Mann M, Bracher F, Teupser D, Saftig P, Biel M, Wahl-Schott C. High susceptibility to fatty liver disease in two-pore channel 2-deficient mice. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4699. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sakurai Y, Kolokoltsov AA, Chen CC, Tidwell MW, Bauta WE, Klugbauer N, Grimm C, Wahl-Schott C, Biel M, Davey RA. Ebola virus. Two-pore channels control Ebola virus host cell entry and are drug targets for disease treatment. Science. 2015;347(6225):995–998. doi: 10.1126/science.1258758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nguyen ON, Grimm C, Schneider LS, Chao YK, Atzberger C, Bartel K, Watermann A, Ulrich M, Mayr D, Wahl-Schott C, Biel M, Vollmar AM. Two-pore channel function is crucial for the migration of invasive cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2017 doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-0852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Papazian DM, Schwarz TL, Tempel BL, Jan YN, Jan LY. Cloning of genomic and complementary DNA from Shaker, a putative potassium channel gene from Drosophila. Science. 1987;237(4816):749–753. doi: 10.1126/science.2441470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo J, Zeng W, Jiang Y. Tuning the ion selectivity of two-pore channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114(5):1009–1014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1616191114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hedrich R, Marten I. TPC1—SV channels gain shape. Mol Plant. 2011;4(3):428–441. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssr017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schulze C, Sticht H, Meyerhoff P, Dietrich P. Differential contribution of EF-hands to the Ca2+-dependent activation in the plant two-pore channel TPC1. Plant J. 2011;68(3):424–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Larisch N, Kirsch SA, Schambony A, Studtrucker T, Böckmann RA, Dietrich P. The function of the two-pore channel TPC1 depends on dimerization of its carboxy-terminal helix. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016;73(13):2565–2581. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2131-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruas M, Davis LC, Chen CC, Morgan AJ, Chuang KT, Walseth TF, Grimm C, Garnham C, Powell T, Platt N, Platt FM, Biel M, Wahl-Schott C, Parrington J, Galione A. Expression of Ca2+-permeable two-pore channels rescues NAADP signalling in TPC-deficient cells. EMBO J. 2015;34(13):1743–1758. doi: 10.15252/embj.201490009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zong X, Schieder M, Cuny H, Fenske S, Gruner C, Rötzer K, Griesbeck O, Harz H, Biel M, Wahl-Schott C. The two-pore channel TPCN2 mediates NAADP-dependent Ca2+-release from lysosomal stores. Pflügers Arch. 2009;458(5):891–899. doi: 10.1007/s00424-009-0690-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brailoiu E, Hooper R, Cai X, Brailoiu GC, Keebler MV, Dun NJ, Marchant JS, Patel S. An ancestral deuterostome family of two-pore channels mediates nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate-dependent calcium release from acidic organelles. J Biol Chem. 2009;285(5):2897–2901. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C109.081943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pluhackova K, Böckmann RA. Biomembranes in atomistic and coarse-grained simulations. J Phys Condens Matter. 2015;27(32):323103. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/27/32/323103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pluhackova K, Wassenaar TA, Böckmann RA. Molecular dynamics simulations of membrane proteins. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;1033:85–101. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-487-6_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arnold K, Bordoli L, Kopp J, Schwede T. The SWISS-MODEL workspace: a web-based environment for protein structure homology modelling. Bioinformatics. 2006;22(2):195–201. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kiefer F, Arnold K, Künzli M, Bordoli L, Schwede T. The SWISS-MODEL repository and associated resources. Nucleic Acid Res. 2009;37:D387–D392. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guex N, Peitsch MC, Schwede T. Automated comparative protein structure modeling with SWISS-MODEL and Swiss-PdbViewer: a historical perspective. Electrophoresis. 2009;30(Suppl 1):S162–S173. doi: 10.1002/elps.200900140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Biasini M, Bienert S, Waterhouse A, Arnold K, Studer G, Schmidt T, Kiefer F, Gallo Cassarino T, Bertoni M, Bordoli L, Schwede T. SWISS-MODEL: modelling protein tertiary and quaternary structure using evolutionary information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:W252–W258. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Studer G, Biasini M, Schwede T. Assessing the local structural quality of transmembrane protein models using statistical potentials (QMEANBrane) Bioinformatics. 2014;30(17):i505–i511. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Jong DH, Singh G, Bennett WF, Arnarez C, Wassenaar TA, Schäfer LV, Periole X, Tieleman DP, Marrink SJ. Improved parameters for the martini coarse-grained protein force field. J Chem Theory Comput. 2013;9(1):687–697. doi: 10.1021/ct300646g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wassenaar TA, Ingólfsson HI, Böckmann RA, Tieleman DP, Marrink SJ. Computational lipidomics with insane: a versatile tool for generating custom membranes for molecular simulations. J Chem Theory Comput. 2015;11(5):2144–2155. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yesylevskyy SO, Schäfer LV, Sengupta D, Marrink SJ. Polarizable water model for the coarse-grained MARTINI force field. PLoS Comput Biol. 2010;6(6):e1000810. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sánchez R, Sali A. Evaluation of comparative protein structure modeling by MODELLER-3. Proteins Suppl. 1997;1:50–58. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0134(1997)1+<50::AID-PROT8>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wassenaar TA, Pluhackova K, Böckmann RA, Marrink SJ, Tieleman DP. Going backward: a flexible geometric approach to reverse transformation from coarse grained to atomistic models. J Chem Theory Comput. 2014;10(2):676–690. doi: 10.1021/ct400617g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hess B, Kutzner C, van der Spoel D, Lindahl E. GROMACS 4: algorithms for highly efficient, load-balanced, and scalable molecular simulation. J Chem Theory Comput. 2008;4(3):435–447. doi: 10.1021/ct700301q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Darden T, York D, Pedersen L. Particle Mesh Ewald—an N.Log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J Chem Phys. 1993;98(12):10089–10092. doi: 10.1063/1.464397. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bussi G, Donadio D, Parrinello M. Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. J Chem Phys. 2007;126(1):014101. doi: 10.1063/1.2408420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Berendsen HJC, Postma JPM, Vangunsteren WF, Dinola A, Haak JR. Molecular-dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J Chem Phys. 1984;81(8):3684–3690. doi: 10.1063/1.448118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.López CA, Sovova Z, van Eerden FJ, de Vries AH, Marrink SJ. Martini Force field parameters for glycolipids. J Chem Theory Comput. 2013;9(3):1694–1708. doi: 10.1021/ct3009655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marrink SJ, de Vries AH, Mark AE. Coarse grained model for semiquantitative lipid simulations. J Phys Chem B. 2004;108(2):750–760. doi: 10.1021/jp036508g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abraham MJ, Murtola T, Schulz R, Páll S, Smith JC, Hess B, Lindahl E. GROMACS: high performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX. 2015;1–2:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.softx.2015.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Best RB, Zhu X, Shim J, Lopes PE, Mittal J, Feig M, Mackerell AD., Jr Optimization of the additive CHARMM all-atom protein force field targeting improved sampling of the backbone phi, psi and side-chain chi(1) and chi(2) dihedral angles. J Chem Theory Comput. 2012;8(9):3257–3273. doi: 10.1021/ct300400x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mallajosyula SS, Guvench O, Hatcher E, Mackerell AD., Jr CHARMM additive all-atom force field for phosphate and sulfate linked to carbohydrates. J Chem Theory Comput. 2012;8(2):759–776. doi: 10.1021/ct200792v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Klauda JB, Venable RM, Freites JA, O’Connor JW, Tobias DJ, Mondragon-Ramirez C, Vorobyov I, MacKerell AD, Jr, Pastor RW. Update of the CHARMM all-atom additive force field for lipids: validation on six lipid types. J Phys Chem B. 2010;114(23):7830–7843. doi: 10.1021/jp101759q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hatcher E, Guvench O, Mackerell AD., Jr CHARMM additive all-atom force field for acyclic polyalcohols, acyclic carbohydrates and inositol. J Chem Theory Comput. 2009;5(5):1315–1327. doi: 10.1021/ct9000608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pluhackova K, Kirsch SA, Han J, Sun L, Jiang Z, Unruh T, Böckmann RA. A critical comparison of biomembrane force fields: structure and dynamics of model DMPC, POPC, and POPE bilayers. J Phys Chem B. 2016;120(16):3888–3903. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.6b01870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sievers F, Wilm A, Dineen D, Gibson TJ, Karplus K, Li W, Lopez R, McWilliam H, Remmert M, Söding J, Thompson JD, Higgins DG. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol Syst Biol. 2011;7:539. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sun L, Bertelshofer F, Greiner G, Böckmann RA. Characteristics of sucrose transport through the sucrose-specific porin ScrY studied by molecular dynamics simulations. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2016;4:9. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2016.00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bertelshofer F, Sun L, Greiner G, Böckmann RA. GroPBS: fast solver for implicit electrostatics of biomolecules. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2015;3:186. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2015.00186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Böckmann RA, de Groot BL, Kakorin S, Neumann E, Grubmuller H. Kinetics, statistics, and energetics of lipid membrane electroporation studied by molecular dynamics simulations. Biophys J. 2008;95(4):1837–1850. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.129437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tzfira T, Tian GW, Lacroix B, Vyas S, Li J, Leitner-Dagan Y, Krichevsky A, Taylor T, Vainstein A, Citovsky V. pSAT vectors: a modular series of plasmids for autofluorescent protein tagging and expression of multiple genes in plants. Plant Mol Biol. 2005;57(4):503–516. doi: 10.1007/s11103-005-0340-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Edelheit O, Hanukoglu A, Hanukoglu I. Simple and efficient site-directed mutagenesis using two single-primer reactions in parallel to generate mutants for protein structure-function studies. BMC Biotechnol. 2009;9:61. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-9-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ranf S, Wünnenberg P, Lee J, Becker D, Dunkel M, Hedrich R, Scheel D, Dietrich P. Loss of the vacuolar cation channel, AtTPC1, does not impair Ca2+ signals induced by abiotic and biotic stresses. Plant J. 2008;53(2):287–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Larisch N, Schulze C, Galione A, Dietrich P. An N-terminal dileucine motif directs two-pore channels to the tonoplast of plant cells. Traffic. 2012;13(7):1012–1022. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2012.01366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Costa A, Gutla PV, Boccaccio A, Scholz-Starke J, Festa M, Basso B, Zanardi I, Pusch M, Schiavo FL, Gambale F, Carpaneto A. The Arabidopsis central vacuole as an expression system for intracellular transporters: functional characterization of the Cl-/H+ exchanger CLC-7. J Physiol. 2012;590(15):3421–3430. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.230227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dong XP, Shen D, Wang X, Dawson T, Li X, Zhang Q, Cheng X, Zhang Y, Weisman LS, Delling M, Xu H. PI(3,5)P(2) controls membrane trafficking by direct activation of mucolipin Ca(2 +) release channels in the endolysosome. Nat Commun. 2010;1:38. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li X, Wang X, Zhang X, Zhao M, Tsang WL, Zhang Y, Yau RG, Weisman LS, Xu H. Genetically encoded fluorescent probe to visualize intracellular phosphatidylinositol 3,5-bisphosphate localization and dynamics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(52):21165–21170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311864110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cang C, Aranda K, Ren D. A non-inactivating high-voltage-activated two-pore Na(+) channel that supports ultra-long action potentials and membrane bistability. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5015. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hansen SB, Tao X, MacKinnon R. Structural basis of PIP2 activation of the classical inward rectifier K+ channel Kir2.2. Nature. 2011;477(7365):495–498. doi: 10.1038/nature10370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Whorton MR, MacKinnon R. Crystal structure of the mammalian GIRK2K+ channel and gating regulation by G proteins, PIP2, and sodium. Cell. 2011;147(1):199–208. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rodriguez-Menchaca AA, Adney SK, Tang QY, Meng XY, Rosenhouse-Dantsker A, Cui M, Logothetis DE. PIP2 controls voltage-sensor movement and pore opening of Kv channels through the S4-S5 linker. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(36):E2399–E2408. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207901109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang Q, Zhou P, Chen Z, Li M, Jiang H, Gao Z, Yang H. Dynamic PIP2 interactions with voltage sensor elements contribute to KCNQ2 channel gating. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(50):20093–20098. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1312483110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.