Abstract

Background

Because of wars, conflicts, persecutions, human rights violations, and humanitarian crises, about 84 million people are forcibly displaced around the world; the great majority of them live in low‐ and middle‐income countries (LMICs). People living in humanitarian settings are affected by a constellation of stressors that threaten their mental health. Psychosocial interventions for people affected by humanitarian crises may be helpful to promote positive aspects of mental health, such as mental well‐being, psychosocial functioning, coping, and quality of life. Previous reviews have focused on treatment and mixed promotion and prevention interventions. In this review, we focused on promotion of positive aspects of mental health.

Objectives

To assess the effects of psychosocial interventions aimed at promoting mental health versus control conditions (no intervention, intervention as usual, or waiting list) in people living in LMICs affected by humanitarian crises.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, and seven other databases to January 2023. We also searched the World Health Organization's (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform and ClinicalTrials.gov to identify unpublished or ongoing studies, and checked the reference lists of relevant studies and reviews.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing psychosocial interventions versus control conditions (no intervention, intervention as usual, or waiting list) to promote positive aspects of mental health in adults and children living in LMICs affected by humanitarian crises. We excluded studies that enrolled participants based on a positive diagnosis of mental disorder (or based on a proxy of scoring above a cut‐off score on a screening measure).

Data collection and analysis

We used standard Cochrane methods. Our primary outcomes were mental well‐being, functioning, quality of life, resilience, coping, hope, and prosocial behaviour. The secondary outcome was acceptability, defined as the number of participants who dropped out of the trial for any reason. We used GRADE to assess the certainty of evidence for the outcomes of mental well‐being, functioning, and prosocial behaviour.

Main results

We included 13 RCTs with 7917 participants. Nine RCTs were conducted on children/adolescents, and four on adults. All included interventions were delivered to groups of participants, mainly by paraprofessionals. Paraprofessional is defined as an individual who is not a mental or behavioural health service professional, but works at the first stage of contact with people who are seeking mental health care. Four RCTs were carried out in Lebanon; two in India; and single RCTs in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Jordan, Haiti, Bosnia and Herzegovina, the occupied Palestinian Territories (oPT), Nepal, and Tanzania. The mean study duration was 18 weeks (minimum 10, maximum 32 weeks). Trials were generally funded by grants from academic institutions or non‐governmental organisations.

For children and adolescents, there was no clear difference between psychosocial interventions and control conditions in improving mental well‐being and prosocial behaviour at study endpoint (mental well‐being: standardised mean difference (SMD) 0.06, 95% confidence interval (CI) −0.17 to 0.29; 3 RCTs, 3378 participants; very low‐certainty evidence; prosocial behaviour: SMD −0.25, 95% CI −0.60 to 0.10; 5 RCTs, 1633 participants; low‐certainty evidence), or at medium‐term follow‐up (mental well‐being: mean difference (MD) −0.70, 95% CI −2.39 to 0.99; 1 RCT, 258 participants; prosocial behaviour: SMD −0.48, 95% CI −1.80 to 0.83; 2 RCT, 483 participants; both very low‐certainty evidence). Interventions may improve functioning (MD −2.18, 95% CI −3.86 to −0.50; 1 RCT, 183 participants), with sustained effects at follow‐up (MD −3.33, 95% CI −5.03 to −1.63; 1 RCT, 183 participants), but evidence is very uncertain as the data came from one RCT (both very low‐certainty evidence).

Psychosocial interventions may improve mental well‐being slightly in adults at study endpoint (SMD −0.29, 95% CI −0.44 to −0.14; 3 RCTs, 674 participants; low‐certainty evidence), but they may have little to no effect at follow‐up, as the evidence is uncertain and future RCTs might either confirm or disprove this finding. No RCTs measured the outcomes of functioning and prosocial behaviour in adults.

Authors' conclusions

To date, there is scant and inconclusive randomised evidence on the potential benefits of psychological and social interventions to promote mental health in people living in LMICs affected by humanitarian crises. Confidence in the findings is hampered by the scarcity of studies included in the review, the small number of participants analysed, the risk of bias in the studies, and the substantial level of heterogeneity. Evidence on the efficacy of interventions on positive mental health outcomes is too scant to determine firm practice and policy implications. This review has identified a large gap between what is known and what still needs to be addressed in the research area of mental health promotion in humanitarian settings.

Keywords: Adolescent; Adult; Child; Female; Humans; Adaptation, Psychological; Altruism; Bias; Developing Countries; Health Promotion; Health Promotion/methods; Mental Disorders; Mental Disorders/therapy; Mental Health; Psychosocial Functioning; Psychosocial Intervention; Psychosocial Intervention/methods; Quality of Life; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Refugees; Refugees/psychology; Stress Disorders, Post-Traumatic; Stress Disorders, Post-Traumatic/psychology; Stress Disorders, Post-Traumatic/therapy

Plain language summary

Do psychological and social interventions promote improved mental health in people living in low‐ and middle‐income countries affected by humanitarian crises?

Key message

– We did not find enough evidence in favour of interventions for promoting positive aspects of mental health in humanitarian settings. Larger, well‐conducted randomised studies are needed.

Mental health during a humanitarian crisis

A humanitarian crisis is an event, or series of events, that threatens the health, safety, security, and well‐being of a community or large group of people, usually over a wide area. Examples include wars and armed conflicts; famine; and disasters triggered by hazards such as earthquakes, hurricanes, and floods. People living through a humanitarian crisis may experience physical and mental distress and experience highly challenging circumstances that make them vulnerable to developing mental disorders, such as post‐traumatic stress disorder, depression, and anxiety. The estimated occurrence of mental disorders during humanitarian crises is 17% for depression and anxiety, and 15% for post‐traumatic stress disorder.

What are psychological and social interventions?

Psychological and social interventions (also called psychosocial) recognise the importance of the social environment for shaping mental well‐being. They usually have both psychological components (related to the mental and emotional state of the person; e.g. relaxation) and social components (e.g. efforts to improve social support). They can be aimed at promoting positive aspects of mental health (e.g. strengthening hope and social support, parenting skills), or prevent and reduce psychological distress and mental disorders.

What did we want to find out?

We wanted to know if psychosocial interventions could promote positive mental health outcomes in people living through humanitarian crises in low‐ and middle‐income countries, compared with inactive comparators such as no intervention, intervention as usual (participants are allowed to seek treatments that are available in the community), or waiting list (participants receive the psychosocial intervention after a waiting phase).

What did we do?

We searched for studies that looked at the effects of psychosocial interventions on positive aspects of people's mental health in low‐ and middle‐income countries affected by humanitarian crises. In these studies, we selected those outcome measures representative of positive emotions, positive social engagement, good relationships, meaning, and accomplishment. This is in line with the definition of mental health given by the World Health Organization, according to which mental health is "a state of mental wellbeing that enables people to cope with the stresses of life, realise their abilities, learn well and work well, and contribute to their community." We looked for randomised controlled studies in which the interventions people received were decided at random. This type of study usually gives the most reliable evidence about the effects of an intervention.

What did we find?

We found 13 studies on mental health promotion with a total of 7917 participants. Nine studies were with children and adolescents (aged seven to 18 years), and four were with adults (aged over 18 years). Four studies were carried out in Lebanon; two in India; and one study each in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Jordan, Haiti, Bosnia and Herzegovina, the occupied Palestinian Territories (oPT), Nepal, and Tanzania. The average study duration was 18 weeks (minimum 10 weeks, maximum 32 weeks). Trials were generally funded by grants from academic institutions or non‐governmental organisations. The studies measured mental well‐being, functioning, and prosocial behaviour (a behaviour that benefits other people or society as a whole), at the beginning of the study, at the end of the intervention, and three or four months later. They compared the results in people who did and did not receive the intervention.

What are the results of our review?

There is not enough evidence to make firm conclusions. In children and adolescents, psychosocial interventions may have little to no effect in improving mental well‐being, functioning, and prosocial behaviour, but the evidence is very uncertain. For the adult population, we found encouraging evidence that psychosocial interventions may improve mental well‐being slightly, but there were no data on any other positive dimensions of mental health. Overall, for both children and adults, we are not confident that these results are reliable: the results are likely to change when further evidence is available.

What are the limitations of the evidence?

The main limitation of this review is that we cannot guarantee that the evidence we have generated is trustworthy. This is a direct consequence of the small amount of data that addressed our research question. By conducting analyses from such a small pool of data, we cannot be sure that the changes in outcomes are related to the interventions provided, rather than due to the play of chance. Furthermore, people in the studies were aware of which treatment they were getting, and not all the studies provided data about everything that we were interested in.

How up to date is this evidence?

We included evidence published up to January 2023.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Summary of findings table ‐ Psychosocial intervention compared to control for promoting the mental health of people living in LMICs affected by humanitarian crises (children).

| Psychosocial intervention compared to control for promoting the mental health of people living in LMICs affected by humanitarian crises (children) | ||||||

| Patient or population: promoting the mental health of people living in LMICs affected by humanitarian crises (children) Setting: low‐ and middle‐income countries affected by humanitarian crises Intervention: psychosocial intervention Comparison: control | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with control | Risk with psychosocial intervention | |||||

| Mental well‐being at study endpoint | ‐ | SMD 0.06 SD higher (0.17 lower to 0.29 higher) | ‐ | 3378 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b,c | Investigators measured mental well‐being using different instruments. In 1 case, lower/higher scores mean better/worse mental well‐being, while in the other 2 cases, high numbers suggest greater mental well‐being. The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of psychosocial intervention on mental well‐being at study endpoint. This is a small effect according to Cohen. As a rule of thumb, 0.2 standard deviations (SD) represents a small difference, 0.5 a moderate, and 0.8 a large. |

| Mental well‐being at follow‐up assessed with: Arab Youth Mental Health scale Scale from: 21 to 63 follow‐up: mean 26 weeks | The mean mental well‐being at follow‐up was 30.99 | MD 0.7 lower (2.39 lower to 0.99 higher) | ‐ | 258 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,c,d | Investigators measured mental well‐being using the Arab Youth Mental Health Scale, where higher score is suggestive of poorer mental health. |

| Functioning at study endpoint assessed with: "Functioning impairment" Scale from: 8 to 40 | The mean functioning at study endpoint was 14.98 | MD 2.18 lower (3.86 lower to 0.5 lower) | ‐ | 183 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,d | Investigators measured functional impairment with a self‐report scale that included 8 items derived from the Child Diagnostic Interview Schedule. Higher score suggestive of poorer functioning. |

| Functioning at follow‐up assessed with: "Functioning impairment" Scale from: 8 to 40 follow‐up: mean 34 weeks | The mean functioning at follow‐up was 14.64 | MD 3.33 lower (5.03 lower to 1.63 lower) | ‐ | 183 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,d | Investigators measured functional impairment with a self‐report scale that included 8 items derived from the Child Diagnostic Interview Schedule. Higher score suggestive of poorer functioning. |

| Prosocial behaviour at study endpoint | ‐ | SMD 0.25 SD lower (0.6 lower to 0.1 higher) | ‐ | 1633 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,c | Investigators measured prosocial behaviour using different instruments. In 1 case, lower/higher scores mean better/worse prosocial behaviour, while in all the other cases, high numbers suggest greater prosocial behaviour. The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of psychosocial intervention on prosocial behaviour at study endpoint. This is a small‐to‐moderate effect according to Cohen. As a rule of thumb, 0.2 SD represents a small difference, 0.5 a moderate, and 0.8 a large. |

| Prosocial behaviour at follow‐up follow‐up: mean 10 months | ‐ | SMD 0.48 SD lower (1.8 lower to 0.83 higher) | ‐ | 483 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,c,e | Investigators measured prosocial behaviour using different instruments. Higher/lower scores indicate worse/better mental prosocial behaviour. The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of psychosocial intervention on prosocial behaviour at follow‐up. This is a medium effect according to Cohen. As a rule of thumb, 0.2 SD represents a small difference, 0.5 a moderate, and 0.8 a large. |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; SMD: standardised mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

| See interactive version of this table: https://gdt.gradepro.org/presentations/#/isof/isof_question_revman_web_438685613947752018. | ||||||

a Downgraded one level owing to study limitations (concrete risk of performance and detection bias at least in some trials). b Downgraded one level owing to inconsistency (I2 was higher than 50%). c Downgraded one level owing to imprecision (the confidence intervals included appreciable benefit and harm). d Downgraded two levels owing to imprecision (number of randomised participants well below the optimal information size of 350 participants per arm). e Downgraded one level owing to imprecision (optimal information size of 350 participants per arm not achieved).

Summary of findings 2. Summary of findings table ‐ Psychosocial intervention compared to control for promoting the mental health of people living in LMICs affected by humanitarian crises (adults).

| Psychosocial intervention compared to control for promoting the mental health of people living in LMICs affected by humanitarian crises (adults) | ||||||

| Patient or population: promoting the mental health of people living in LMICs affected by humanitarian crises (adults) Setting: low‐ and middle‐income countries affected by humanitarian crises Intervention: psychosocial intervention Comparison: control | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with control | Risk with psychosocial intervention | |||||

| Mental well‐being at study endpoint | ‐ | SMD 0.29 SD lower (0.44 lower to 0.14 lower) | ‐ | 674 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | Investigators measured mental well‐being using different instruments. In both cases, high numbers suggest greater mental well‐being. Psychosocial intervention may result in a reduction in mental well‐being at study endpoint. This is a small‐to‐moderate effect according to Cohen. As a rule of thumb, 0.2 standard deviations (SD) represents a small difference, 0.5 a moderate, and 0.8 a large. |

| Mental well‐being at follow‐up assessed with: Warwick‐Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale Scale from: 14 to 70 follow‐up: mean 12 weeks | The mean mental well‐being at follow‐up was 45.68 | MD 0.44 lower (2.07 lower to 1.19 higher) | ‐ | 441 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b,c | The score range for the Warwick‐Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale is from 14 to 70, with higher scores indicating higher levels of mental well‐being. |

| Functioning at study endpoint ‐ not measured | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Not measured. |

| Functioning at follow‐up ‐ not measured | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Not measured. |

| Prosocial behaviour at study endpoint ‐ not measured | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Not measured. |

| Prosocial behaviour at follow‐up ‐ not measured | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | Not measured. |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; SMD: standardised mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

| See interactive version of this table: https://gdt.gradepro.org/presentations/#/isof/isof_question_revman_web_438972912524011941. | ||||||

a Downgraded one level owing to study limitations (concrete risk of performance and detection bias at least in some trials). b Downgraded one level owing to imprecision (optimal information size of 350 participants per arm not achieved). c Downgraded one level owing to imprecision (the confidence intervals included appreciable benefit and harm).

Background

Description of the condition

Humanitarian emergencies such as armed conflicts, disasters (e.g. triggered by natural hazards such as earthquakes and cyclones), or pandemics profoundly disrupt the daily lives of those impacted and result in psychological distress for many people. This is particularly the case for people living in low‐ and middle‐income countries (LMICs), where the increasing frequency of public health crises since the 2010s, including the most recent Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic and the resurgence of the Palestinian‐Israeli conflict, has sorely increased the number of people exposed to mental health stressors. Social and environmental factors such as poverty, discrimination, war, and violence all play a key role in all aspects of public health and are risk factors for mental health problems (Lund 2018; Ridley 2020). For example, people living in humanitarian settings (i.e. contexts affected by armed conflicts or by disasters triggered by natural, industrial, or technological hazards) in LMICs may not have adequate access to health care, education, or basic resources such as food or shelter. In addition, humanitarian crises often do not provide the conditions that are necessary to promote positive aspects of mental health, such as suitable housing, adequate income, and opportunities for a strong social network.

By the end of 2020, the number of people forcibly displaced due to war, conflict, persecution, human rights violations, and humanitarian crises had grown to 82.4 million (UNHCR 2020). Syria, Venezuela, Afghanistan, South Sudan, The Democratic Republic of the Congo, Burkina Faso, and Yemen represent just a few of the many hotspots in 2019 that drove people to seek refuge and safety within their country or flee abroad to seek protection (UNHCR 2020). Most displaced populations remain in their region of origin or flee to neighbouring countries (i.e. an LMIC). In fact, LMICs host 82% of the world's refugee population (UNHCR 2015). Humanitarian crises impact a large part of the world's population, often affecting populations already beset by adversity (e.g. discrimination, gender‐based violence, social marginalisation), with 356 million children younger than five years living in extreme poverty, defined as existing on less than US dollars (USD) 1.90 a day (UNICEF 2021).

Two Cochrane reviews have evaluated the effectiveness of approaches to treat (Purgato 2018) and prevent (Papola 2020) mental disorders in people living in LMICs affected by humanitarian crises. These reviews followed the classification of interventions described by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) (Institute of Medicine 1994; Institute of Medicine 2009; Purgato 2020a; Tol 2015). The IOM's classification distinguishes treatment from prevention and promotion. Treatment is aimed at reducing symptoms in people with identified mental disorders and prevention is a complementary approach aimed at reducing the likelihood of future disorders within the general population. Prevention is further subdivided on the basis of the population targeted into universal prevention (interventions in the general population), selective prevention (interventions in subpopulations identified as being at risk for a disorder), and indicated prevention (with individuals having an increased vulnerability for a disorder based on individual assessment) (Institute of Medicine 1994; Papola 2024). Although there may be areas of overlap with prevention, mental health promotion does not directly focus on preventing mental disorders, but on improving positive outcomes or mental well‐being (Institute of Medicine 2009).

Given the broad impact of humanitarian settings on mental health, this review aimed to provide a comprehensive evaluation of the effectiveness of promotion interventions to foster positive aspects of mental health in children, adolescents, and adults living in LMICs affected by humanitarian crises.

Description of the intervention

Mental health and psychosocial support interventions are becoming a standard part of humanitarian programmes. These interventions cover a wide range of objectives, from addressing the environmental conditions that shape well‐being to the management of severe (neuro)psychiatric disorders. Accordingly, they are implemented in diverse humanitarian sectors including health, protection, nutrition, shelter, and education (Miller 2021). Although this was previously an ideologically divided field, there appears to be growing agreement on best practices, as suggested by international consensus‐based documents (IASC 2007; The Sphere Project 2011). These documents advocate multilayered systems of care, to address the diversity of mental health and psychosocial needs in humanitarian settings. Such recommended multilayered systems of care are envisioned to include interventions to address the broad range of mental health needs in populations affected by humanitarian crises.

A Lancet Commission set up in 2018 to align global mental health efforts with sustainable development goals has emphasised the importance of action to promote mental health (Patel 2018). Promotion is an approach that aims to strengthen positive aspects of mental well‐being; it includes, for example, intervention components that foster prosocial behaviour, self‐esteem, positive coping with stress, and decision‐making capacity (WHO 2018a). Mental health promotion usually targets the entire population (universal), but may target high‐risk populations such as refugees, asylum seekers, and internally displaced people (selective health promotion). It considers outcomes related to positive aspects of psychological functioning and mental well‐being rather than ill health (Purgato 2021a; Tol 2015). Psychosocial interventions aimed to promote mental health delivered in LMICs affected by humanitarian crises may include individual‐level, group‐based, or community‐based interventions. For example, activities to encourage good mental health and development for children may take place in classrooms or in refugee camps. One definition of promotion includes a wider set of interventions provided at societal, community, individual, and family levels. These updates reflect important trends in research in the field of public mental health, and reveal the enduring importance of a spectrum of key tools for fostering mental health and reducing the treatment gap between high‐income countries (HIC) and LMICs (National Academies of Sciences 2019).

Since 2010, 'task sharing' strategies have been increasingly advocated as a pivotal tool to deliver psychosocial interventions to treat, prevent, or promote mental health in low‐resource settings (Patel 2010; van Ginneken 2021), and in humanitarian settings (Barbui 2020; Papola 2020; Purgato 2018). The World Health Organization (WHO) defines task shifting as "the rational redistribution of tasks among health workforce teams" (WHO 2018b). In other words, specific functions are shifted, where appropriate, from highly qualified health workers to health workers with shorter training and fewer qualifications, to make more efficient use of the available human resources for health. The specialist role shifts from direct service provider towards supervisor and consultant to train 'primary‐level health workers'. Systematic reviews and conventional meta‐analyses of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) show that psychosocial interventions delivered by locally available primary‐level health workers in community and primary care settings are promising to treat common mental disorders in LMICs (Bangpan 2019; Kamali 2020; Purgato 2021b; Purgato 2023). Mental health promotion interventions are very often implemented outside of healthcare settings in community settings.

How the intervention might work

Mental health promotion aims at strengthening positive aspects of mental health and psychosocial well‐being (Institute of Medicine 2009). Mental health promotion activities are contingent on the definition of mental health as being more than the absence of disease (i.e. as "a state of well‐being in which every individual realises his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to her or his community") (WHO 2018c). Psychosocial promotion interventions may achieve their aim by strengthening psychological skills (e.g. training positive coping strategies), or by improving the social, physical, and economic environments that influence mental health (e.g. providing communities with the resources to strengthen social connectedness).

Psychosocial interventions may build on knowledge with regard to resilience and strength‐focused processes. Interventions may focus, for example, on introducing creative expressive elements (co‐operative activities, structured movement, relaxation), reinforcing self‐esteem, social support (even group cohesion within the intervention group), empowerment, and emotion regulation (Wessells 2015; Wessells 2018). Psychosocial interventions to promote mental health are often delivered in an empowering, collaborative, and participatory manner to foster positive aspects of mental health in individuals, such as coping capacity and resilience. They increase connections between individuals and communities, create opportunities for income generation and employment, and strengthen positive family and peer relations and other social support mechanisms (Hobfoll 2007; WHO 2004). Mental health promotion is commonly attempted through multisectoral interventions (i.e. with activities across a wide number of sectors, policies, programmes, settings, and environments). Mental health promotion requires action to influence the full range of potentially modifiable determinants of mental health (Hobfoll 2007; Marmot 2014). These include not only those related to the actions of individuals, such as behaviours and ways of life, but also factors such as income and social status, education, employment and working conditions, access to appropriate health services, and the physical environment (Walker 2005).

A popular conceptual framework for psychosocial interventions in humanitarian settings is that of 'ecological resilience' (Tol 2013; Ungar 2013), which has been defined as "those assets and processes on all socioecological levels that have been shown to be associated with good developmental outcomes after exposure to situations of conflict" (Bronfenbrenner 1979; Tol 2008). Ecological resilience refers to a process whereby people attain desirable outcomes despite significant risks to their adaptation and development (Theron 2016; Ungar 2020). These processes are thought to involve dynamic relationships between risk, protective factors, and promotive factors at different levels of the person's social ecology (e.g. individual, family, neighbourhood levels) (Betancourt 2008; Betancourt 2013).

Mental health promotion aims to raise the position of mental health in the scale of values of individuals, families, and societies, so that decisions taken by government and business can ensure social conditions and factors that create positive environments for good mental health and well‐being of populations, communities, and individuals (Frankish 2018).

Why it is important to do this review

The present review is necessary, and considered particularly timely, for at least three reasons.

The largest populations affected by humanitarian crises live in LMICs. For example, four out of the five countries most often hit by disasters associated with natural hazards since the mid‐2010 are LMICs (China, the Philippines, India, and Indonesia) (Centre for research on epidemiology of disasters – CRED). Similarly, 30 of the 32 armed conflicts and wars recorded by the Uppsala Conflict Data Program in 2012 took place in LMICs (93.8%) (Themnér 2013). A considerable number of studies have examined mental health in populations affected by humanitarian crises (Attanayake 2009; Augustinavicius 2018; Greene 2017; Jordans 2016; Morina 2017; Papola 2020; Purgato 2018; Siriwardhana 2014; Steel 2009; Tol 2015).

In general, LMICs differ from HICs with regard to numerous characteristics; thus, LMICs and HICs are to be reviewed separately. Among the most striking differences between LMICs and HICs are: health system indicators (e.g. the number of mental health professionals available); humanitarian response capacity; and distribution of the determinants of mental health before the onset of humanitarian crises. In addition, there is a large variety of ways in which populations conceptualise and seek assistance for mental health problems in LMICs that may differ from conceptualisations and help‐seeking patterns in high‐income industrialised countries (Kohrt 2013). Therefore, evidence regarding the effectiveness of interventions implemented in HICs may not generalise or be relevant to LMICs. Given the large impact of humanitarian crises in LMICs and unknown generalisability of findings from HICs, this review focused on psychosocial interventions aimed at promoting mental health implemented with populations living in LMICs.

There is currently no systematic review of psychosocial interventions specifically aimed at promoting the mental health of people living in LMICs affected by humanitarian crises (Uphoff 2020). Although psychosocial promotion interventions have been popular in practice, an earlier systematic review did not identify a large number of rigorous studies evaluating the benefits of such interventions for mental health (Tol 2011). A Cochrane overview of reviews found similar results (Uphoff 2020). One review focused on the efficacy of process‐based forgiveness interventions among samples of adolescents and adults who had experienced a range of hurt or violence provided evidence suggesting that forgiving a variety of real‐life interpersonal offences can be effective in promoting different dimensions of mental well‐being (Akhtar 2018). Regardless of such conflicting results, it should be noted that none of these reviews focused specifically on LMICs.

Objectives

To assess the effects of psychosocial interventions aimed at promoting mental health versus control conditions (no intervention, intervention as usual, or waiting list) in people living in LMICs affected by humanitarian crises.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included RCTs. Trials that employ a cross‐over design were also eligible. We excluded quasi‐RCTs, in which participants were allocated to different arms of the trial using a method of allocation that was not truly random (e.g. allocation based on date of birth, or the order in which people were recruited). We considered both individual and cluster‐randomised trials as eligible for inclusion.

Types of participants

Participant characteristics

We considered participants of any age, gender, ethnicity, and religion. Consistent with the two parallel Cochrane reviews mentioned in the Description of the condition (Papola 2020; Purgato 2018), we planned two separate meta‐analyses on the different outcomes, one for children and adolescents (aged less than 18 years), and one for adults (aged 18 years and older). Studies with mixed population groups (children and adolescents; adults) were allocated according to the proportion of participants belonging to the child and adolescent age range, or to the adult age range.

Setting

We considered studies conducted in humanitarian settings in LMICs (i.e. contexts affected by armed conflicts or by disasters triggered by natural, industrial, or technological hazards). We applied the World Bank criteria for categorising a country as low or middle income (World Bank 2021). More specifically, we focused on people who had experienced a humanitarian crisis in an LMIC and who were living in a humanitarian setting in an LMIC at the time of the study. We excluded studies undertaken in HICs. According to the World Bank (World Bank 2021), for the 2021 fiscal year, low‐income economies were defined as those with a gross national income (GNI) per capita of USD 1035 or less in 2019; middle‐income economies were those with a GNI per capita between USD 1036 and USD 4045; upper middle‐income economies were those with a GNI per capita between USD 4046 and USD 12,535; and high‐income economies were those with a GNI per capita of USD 12,536 or more. Psychosocial interventions aimed at promoting mental health may have been delivered in healthcare settings, refugee camps, schools, communities, survivors' homes, and detention facilities. We included studies with populations experiencing the humanitarian crisis at the time the study was conducted, as well as studies conducted after the acute phase of humanitarian crises.

Diagnosis

Given the focus on mental health promotion, we excluded studies that selected participants meeting criteria for a formal psychiatric diagnosis at the time of enrolment in the study. We also excluded studies that included participants scoring above a disclosed validated cut‐off score on a scale measuring psychological symptoms associated with a particular mental disorder at baseline, as this may be considered a proxy of a psychiatric diagnosis. However, because many studies screen on the basis of a risk factor or heightened symptoms, we could not exclude the possibility that trial participants might have fulfilled criteria for an actual psychiatric diagnosis that remained unobserved because it was not investigated when the trial was undertaken. For example, we included populations who left their homes due to a sudden impact, threat, or conflict; populations exposed to political violence/armed conflicts/natural and industrial disasters; those with major losses or in poverty; and those belonging to a group (i.e. people who were discriminated against or marginalised) experiencing political oppression, family separation, disruption of social networks, destruction of community structures and resources and trust, increased gender‐based violence, and undermined community structures or traditional support mechanisms (IASC 2007).

We only included studies of mixed populations if most participants did not meet a formal psychiatric diagnosis or a proxy thereof (i.e. scoring above the cut‐off of a screening measure). We adopted a common‐sense strategy, also relying on authors' specific statements of intent, without specifying any arbitrary threshold with regard to cut‐offs on symptom checklists, as suggested in Section 5.2 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2017).

Comorbidities

We included studies with participants reporting physical disorders.

Types of interventions

Included interventions

We included studies assessing any types of intervention with a psychosocial component aimed at promoting mental health (i.e. interventions with a psychological or social component aimed at creating living conditions and environments that support mental health and encourage positive healthy lifestyles, as well as teaching people social and emotional skills).

Included mental health promotion interventions could have been delivered by a range of facilitators, including primary‐level health workers, or community workers (in a range of sectors). Primary‐level health workers include professionals (doctors, nurses, midwives, and other general health professionals) and paraprofessionals (such as trained lay health providers, e.g. traditional birth attendants) working in non‐specialised healthcare settings (e.g. primary care, HIV/AIDS care, maternal care). Community workers are paraprofessionals who work in the community, and represent an important human resource employed in the delivery of promotion and prevention interventions (Patel 2007). Community workers might include teachers, trainers, support workers from schools and colleges, social workers, and other volunteers or workers within community‐based networks or non‐governmental organisations (NGOs). In this review, we considered both primary‐level health workers and community workers under the umbrella term of 'non‐specialist workers' (NSWs) (see also Description of the intervention).

Psychosocial interventions could be delivered at individual, group, family, community, or societal levels (National Academies of Sciences 2019). Interventions may be delivered through any means, including, for example, face‐to‐face meetings, digital tools, radio, telephone, or self‐help booklets, between participants and primary‐level health workers. Both individual and group interventions were eligible for inclusion, with no limit placed on the number of sessions.

Excluded interventions

We excluded interventions that aimed to treat people with a diagnosed mental disorder, or explicitly aimed to prevent mental disorders (i.e. specifically aiming to reduce the incidence of mental disorders). We used the following criteria to define a study that aimed to prevent mental disorders.

The primary outcome of the study aimed to measure the incidence of mental disorders by means of a formal diagnostic assessment.

The primary outcome of the study utilised a rating scale which was dichotomised to set a cut‐off, above which the participant was considered to have a diagnosis of a mental disorder.

The study measured the frequency of the diagnosis at follow‐up.

We also excluded studies that included participants on the basis of scoring above a cut‐off on a symptom checklist.

Comparators

As control comparators, we considered the following.

No intervention.

Care as usual (CAU) (also called standard/usual care): participants could receive any appropriate general support during the course of the study on a naturalistic basis.

Waiting list: delaying delivery of the intervention to the control group until all participants in the intervention group had completed the intervention. As in CAU, participants in the waiting‐list control could have received any appropriate support during the course of the study on a naturalistic basis.

Participants may have received any appropriate medical care during the course of the study on a naturalistic basis, including pharmacotherapy, as deemed necessary by the healthcare staff.

Types of outcome measures

We included studies that met the above inclusion criteria regardless of whether they reported on the following outcomes.

Primary outcomes

Mental well‐being: having good mental health, or being mentally healthy, is more than just the absence of illness, rather it is a state of overall well‐being (WHO 2018c). The concept of mental well‐being generally relates to enjoyment of life, having the ability to cope with and 'bounce back' (recover) from stress and sadness, being able to set and fulfil goals, and having the capability to build and maintain relationships with others. Mental well‐being is commonly measured with the WHO Five Well‐Being Index (WHO‐5) (Topp 2015), or with other validated rating scales (Clarke 2011).

Functioning: is an objective performance in a given life domain, and is often measured with the WHO Disability Assessment Scheme (WHO 2010), Global Assessment of Functioning (APA 2000), or with other validated rating scales.

Quality of life: is defined by the WHO as "an individual's perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns" (WHO 2018b). It can be measured with the Quality of Life Scale (CASP‐19) (Hyde 2003), the WHO Quality of Life scale (WHO 2012), or with other validated rating scales (Burckhardt 2003).

Resilience: refers to the effective use of resources to maintain good mental health in the face of adversity. Resilience can be measured with the Child and Youth Resilience Measure (CYRM; Ungar 2011), the Connor‐Davidson Resilience Scale (CD‐RISC; Connor 2003), or with other validated rating scales (Windle 2011).

Coping: is intended as the capacity to use a series of actions, or a thought process used in meeting a stressful or unpleasant situation or in modifying one's reaction to such a situation. Coping may be measured with the Kidcope (Spirito 1988), or with other validated rating scales (Carver 1989).

Hope: is the expectation that one will have positive experiences, or that a potentially threatening or negative situation will not materialise or will ultimately result in a favourable state of affairs. Hope can be measured with the Children's Hope Scale (CHS) (Snyder 1997), or with other validated rating scales (Snyder 1991).

Prosocial behaviour: is a behaviour that could bring benefit to other people or society as a whole. Prosocial behaviour activities are those such as helping, sharing, donating, co‐operating, and volunteering. Prosocial behaviour may be measured with the prosocial subscale derived from the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) (Goodman 1997), or with other validated rating scales (Carlo 2002).

Secondary outcomes

Acceptability: number of participants who dropout of the trial for any reason.

Timing of outcome assessment

We grouped primary and secondary outcomes into three sets of time points.

Postintervention (up to one month after the intervention)

One to six months postintervention (medium‐term follow‐up)

Seven to 24 months postintervention (long‐term follow‐up)

Hierarchy of outcome measures

If more than one relevant outcome measure was available in the domain of interest and both described the domain adequately, we chose the measure with the most detailed sociocultural evaluation or the one that other trials in the analysis used. Secondarily, we chose any measure that the study authors stated was tested for suitability in the population of interest.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases and trial registers using relevant keywords, subject headings (controlled vocabularies), and search syntax appropriate to each resource (Appendix 1).

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2023, Issue 1) in the Cochrane Library

MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to 20 January 2023)

Embase Ovid (1974 to 20 January 2023)

PsycINFO Ovid (1806 to 20 January 2023)

PTSDpubs ProQuest (all available years to 20 January 2023)

Dissertations & Theses ProQuest (all available years to 20 January 2023)

ERIC (EBSCO – Education Resources Information Center; 1966 to 20 January 2023)

EconLit Ovid (1886 to 20 January 2023)

JSTOR (all available years to 20 January 2023)

Campbell Collaboration (all available years to 20 January 2023)

US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov; all available years to 20 January 2023)

WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (apps.who.int/trialsearch; all available years to 20 January 2023)

We placed no restrictions on date, language, or publication status for the searches.

Searching other resources

Grey literature

We searched sources of grey literature, including dissertations and theses, humanitarian reports, and evaluations published on websites, clinical guidelines, and reports from regulatory agencies (where appropriate).

Reference lists

We checked the reference lists of all included studies and relevant systematic reviews (both Cochrane and non‐Cochrane) to identify additional studies missed from the original electronic searches. We also performed forward‐citation searches (of the included study reports) using the Web of Science and Google Scholar.

Correspondence

We contacted trialists and subject experts for information on unpublished or ongoing studies, or to request additional trial data.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We downloaded all titles and abstracts retrieved by electronic searching to Covidence (Covidence), a reference management database, and removed duplicates. Review authors (DP, EP, CCec, CCad, MCF, CG) independently screened titles and abstracts for inclusion. Then, the same authors retrieved the full‐text study report/publication of eligible titles and abstracts, and independently screened the full text to finally identify studies for inclusion. We resolved any disagreements through discussion or, if required, we consulted a third review author (CB, MP). When screening the articles, we inspected them to identify trials that met the following inclusion criteria.

RCTs.

Any psychosocial intervention that aimed to promote mental health compared with no intervention, waiting‐list control, or intervention as usual.

Children, adolescents, and adults living in humanitarian settings in LMICs without a formal diagnosis of post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, depression according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 3rd Edition (DSM III) (APA 1980), Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 3rd Edition Revised (DSM‐III‐R) (APA 1987), Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th Edition Text Revision (DSM‐IV‐TR) (APA 2000), Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th Edition (DSM‐5) (APA 2103) or International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision (ICD‐10) (WHO 1992), or any other standardised criteria.

We identified and excluded duplicate records, and collated multiple reports that related to the same study so that each study rather than each report was the unit of interest in the review. We identified and recorded reasons for exclusion of the ineligible full‐text articles. We recorded the selection process in sufficient detail to complete a PRISMA flow diagram (Page 2021).

Data extraction and management

We extracted descriptive and outcome data for each study using an adapted version of the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) standard data collection form (EPOC 2017). We piloted the form on two studies in the review. Two pairs of review authors (DP and EP, or CCec and MCF or CCad) independently extracted descriptive data; we resolved disagreements by discussion and arbitration by one of the senior review authors (MP, CB). We extracted the following study characteristics from the included studies and entered the data into Review Manager (Review Manager 2024).

Methods: study design; number of study centres and locations; study settings; dates of study; follow‐up

Participants: number; mean age; age range; gender; health conditions; inclusion criteria; exclusion criteria; duration of exposure to the crisis; other relevant characteristics such as ethnicity and socioeconomic status

Interventions: type and length of intervention; full description of cadre(s) of primary‐level health or community workers, including details on supervision, training, and length, frequency, and type of experience; comparison; timing of the intervention (during or after the crisis); presence of a fidelity assessment

Setting: country; type of implementation setting (e.g. workplace, school, community); type of humanitarian crisis; type of traumatic event

Outcomes: main and other outcomes specified and collected; time points reported

Notes: funding for the trial; notable conflicts of interest of trial authors; ethical approval

We sought key unpublished information by contacting study authors of included studies via email.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (DP, EP, CCad) independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2017). We resolved any disagreements by discussion or by involving another review author (CB or MP). We assessed the risk of bias according to the following domains.

Random sequence generation

Allocation concealment

Blinding of participants and personnel

Blinding of outcome assessment

Incomplete outcome data

Selective outcome reporting

Other bias

Therapist qualification

Therapist/investigator allegiance

Intervention fidelity

We evaluated cluster‐randomised trials according to Section 16.3.2 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2017). In particular, we considered: recruitment bias, baseline imbalance, loss of clusters, and incorrect analysis. For each cluster‐RCT we verified, where possible: if all clusters were randomised at the same time, if samples were stratified on variables likely to influence outcomes, if clusters were pair‐matched, and if there was baseline comparability between psychosocial interventions and control groups.

We judged each potential source of bias as high, low, or unclear and provided a supporting quotation from the study report or a justification for our judgement in the risk of bias table.

For the domain of 'selective outcome reporting', we considered the study to have an unclear risk of bias if there was no protocol information and no trial registration, even if all measures described in the methods were reported in the results; for the same domain, we considered the study to have a low risk if there was at least a trial registration number and there were no other concerns.

We evaluated the risk of bias in the included studies using the Cochrane RoB 1 tool (Higgins 2017), for consistency with methods in the two previous reviews on psychosocial interventions that aimed to treat (Purgato 2018) and prevent (Papola 2020) mental health disorders in people living in LMICs affected by humanitarian crises.

Measures of treatment effect

We estimated the effect of the psychosocial intervention using the risk ratio (RR) with its 95% confidence interval (CI) for dichotomous data, and the mean difference (MD) or standardised mean difference (SMD) with 95% CIs for continuous data (Higgins 2021). We ensured that an increase in scores for continuous outcomes could be interpreted in the same way for each outcome, explained the direction of the scale to the reader, and reported when the directions were reversed, if this was necessary. For SMDs, we used the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions to interpret their clinical relevance: 0.2 represents a small effect, 0.5 a moderate effect, and 0.8 a large effect (Cohen 1988; Higgins 2021).

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

We included cluster‐RCTs when communities, primary healthcare facilities, schools, or classes within schools rather than single individuals were the unit of allocation. Because variation in response to psychosocial interventions between clusters may be influenced by cluster membership, we included, when possible, data adjusted with an intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC). We adjusted the results for clustering by multiplying standard errors (SE) of the estimates by the square root of the design effect when the design effect was calculated as DEff = 1 + (M − 1) × ICC, where M is the mean cluster size. When included studies did not report ICCs for respective outcome measures, we derived ICCs from a different outcome from the same study, or from a different study included in the same meta‐analysis. If the ICC value was not reported or was not available from trial authors directly, we assumed it to be 0.05 (Higgins 2021; Ukoumunne 1999). We combined adjusted measures of effects of cluster‐randomised trials with results of individually randomised trials when it was possible to adjust the results of cluster trials adequately.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted investigators to verify key study characteristics and to obtain missing outcome data when possible (e.g. when a study was identified as abstract only). We tried to compute missing summary data from other reported statistics (Higgins 2021). We documented all the correspondence with trial authors that were contacted in order to provide unpublished data (Appendix 2). As mentioned above, when the ICC was neither available from the trial reports nor directly available from the trial authors, we assumed it to be 0.05 (Ukoumunne 1999). For continuous data, we applied a looser form of intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis, whereby all participants with at least one postbaseline measurement were represented by their last observation carried forward (LOCF). If the authors of included RCTs stated that they used an LOCF approach, we checked details on LOCF strategy and used data as reported by the study authors. When study authors report only the SE, t statistics, or P values, we calculated standard deviations according to Altman 1996. For dichotomous data, we applied ITT analysis, whereby we considered all dropouts not included in the analyses as negative outcomes (i.e. we assumed they would have experienced the negative outcome by the end of the trial).

When it was not possible to obtain data, we reported the level of missingness and considered how that might impact the certainty of evidence.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed clinical heterogeneity through the creation of comprehensive synoptic tables by which it is possible to assess the variability of participants, interventions, and outcomes across trials (Characteristics of included studies table).

We assessed methodological heterogeneity by applying the risk of bias assessment to the included studies (Assessment of risk of bias in included studies; Characteristics of included studies table).

We obtained an initial visual overview of statistical heterogeneity by scrutinising the forest plots while looking at the overlap between CIs around the estimate for each included study. To quantify the impact of heterogeneity on each meta‐analysis we used the I2 statistic and considered the following ranges, according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2021).

0% to 40%: might not be important

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity

The importance of the observed I2 statistic depends on the magnitude and direction of intervention effects and the strength of evidence for heterogeneity (Higgins 2021; Purgato 2012).

If any meta‐analysis was associated with substantial levels of heterogeneity (i.e. I2 statistic > 75%), two review authors (MP and DP) independently checked data to ensure they were entered correctly. Assuming data were entered correctly, we investigated the source of this heterogeneity by visually inspecting the forest plots, and we removed each trial that had a very different result to the general pattern of the others until homogeneity was restored as indicated by an I2 statistic value of less than 75%. We reported the results of this sensitivity analysis in the text of the review alongside hypotheses regarding the likely causes of the heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

As far as possible, we minimised the impact of reporting biases by undertaking comprehensive searches of multiple sources, increasing efforts to identify unpublished material without language restrictions. We did not use funnel plots for outcomes where there were fewer than 11 studies, or where all studies were of similar sizes (Sterne 2011).

Data synthesis

Given the potential heterogeneity of mental health promotion psychosocial interventions, we used a random‐effects model in all analyses (Borenstein 2019). The random‐effects model has the highest generalisability in empirical examinations of summary effect measures for meta‐analyses (Furukawa 2002). Specifically, for dichotomous data, we used the Mantel‐Haenszel method, as this is preferable in Cochrane reviews, given its better statistical properties when there are few events (Higgins 2021). We adopted the inverse variance method for continuous data: this method minimises the imprecision of the pooled effect estimate, as the weight given to each study is chosen to be the inverse of the variance of the effect estimate (Hjemdal 2011).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

The small number of RCTs included in this review did not allow us to undertake subgroup analyses as preplanned in the protocol (Papola 2022a). See Differences between protocol and review.

Sensitivity analysis

Owing to the small number of RCTs included in this review, it was not possible to carry out sensitivity analyses. See Differences between protocol and review.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We used the GRADE approach to interpret findings (Langendam 2013). Using GRADEpro GDT software, we imported data from Review Manager to create summary of findings tables (GRADEpro GDT; Review Manager 2024). These tables provide outcome‐specific information concerning the overall certainty of the evidence from studies included in the comparison, the magnitude of effect of the psychosocial interventions examined, and the sum of available data on the outcomes we considered. We adhered to the standard methods for the preparation and presentation results outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Guyatt 2013; Higgins 2021). Two review authors (DP, CG) independently performed the GRADE assessments, and resolved disagreements by arbitration by a senior review author (MP).

We included the following outcomes as measured at trial endpoint and follow‐up in the summary of findings tables.

Mental well‐being

Functioning

Prosocial behaviour

We created two summary of findings tables, one for children and one for adults, for the comparison of psychosocial intervention versus control. For continuous outcomes, we adopted the Cohen's approach for the interpretation of effect size (0.2 represents a small effect; 0.5 represents a moderate effect; 0.8 represents a large effect) (Cohen 1988).

As RoB 1 does not calculate an overall risk of bias across risk of bias domains (Higgins 2017), we decided to downgrade the certainty of evidence due to study limitations if concrete risks of bias were reported in one or more domains for the studies providing outcome data.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

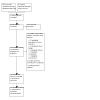

We identified 5014 records from electronic sources to January 2023. Of these, we removed 1768 duplicates and 3185 records after title/abstract level screening. Sixty‐one studies (72 reports) underwent full‐text screening. Of these, we included 13 RCTs with 7917 participants (see Characteristics of included studies table) and excluded 45 studies (see Characteristics of excluded studies table). Two studies are awaiting classification (see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification table) and one study is ongoing (see Characteristics of ongoing studies table) (see Figure 1 for the PRISMA flow diagram).

1.

Study flow diagram.

We contacted the author of one study (Panter‐Brick 2018), to request details not reported in the study publication (Papola 2023 [pers comm]). The data supplied are available in Appendix 2.

Included studies

See Characteristics of included studies table for further details.

Design

We included six trials that randomised participants at the individual level (Berger 2018; Dybdahl 2001; James 2020; Leventhal 2015; O'Callaghan 2014; Yankey 2019), and seven cluster‐randomised trials (Afifi 2010; Dhital 2019; Diab 2015; Maalouf 2020; Miller 2020; Miller 2023; Panter‐Brick 2018). There were no cross‐over trials.

Sample sizes

Included studies involved 7917 participants, with the number of participants in each trial ranging from 87 (Dybdahl 2001) to 2732 (Leventhal 2015).

Setting

Four studies were carried out in Lebanon (Afifi 2010; Maalouf 2020; Miller 2020; Miller 2023); two in India (Leventhal 2015; Yankey 2019); and one each in The Democratic Republic of the Congo (O'Callaghan 2014), Jordan (Panter‐Brick 2018), Haiti (James 2020), Bosnia and Herzegovina (Dybdahl 2001), Palestine (Diab 2015), Nepal (Dhital 2019), and Tanzania (Berger 2018). In Dhital 2019 and James 2020, the humanitarian crisis was triggered by natural disasters, whereas in Berger 2018, Leventhal 2015, and Yankey 2019 the trigger was extreme poverty. In all the other cases, the humanitarian crisis was the aftermath of war or armed conflicts. Five studies delivered the intervention in community facilities (Dybdahl 2001; Miller 2020; Miller 2023; O'Callaghan 2014; Panter‐Brick 2018), and the other studies delivered the intervention in schools. Aside from Dhital 2019, Diab 2015, Dybdahl 2001, and Maalouf 2020, which delivered the intervention after the end of the humanitarian crisis, all included studies delivered psychological and social interventions during the acute crisis.

Participants

Most studies considered adolescents between 11 and 18 years of age (Afifi 2010; Berger 2018; Dhital 2019; Diab 2015; Leventhal 2015; Maalouf 2020; Panter‐Brick 2018; Yankey 2019), one study considered both children and adolescents (O'Callaghan 2014). James 2020 focused on adults, Dybdahl 2001 considered mother–child dyads, while two other studies focused on refugee caregivers with at least one child between the ages of three and 12 years (Miller 2020; Miller 2023). For these studies, we considered the outcomes related to the adult caregivers, as the interventions were primarily directed to promote their mental health. In all studies except Leventhal 2015 (enrolled only girls), both genders were represented. The main types of potentially traumatic events were bereavement (Diab 2015; Maalouf 2020; O'Callaghan 2014); displacement (Afifi 2010; Dhital 2019; Dybdahl 2001; Miller 2020; Miller 2023; Panter‐Brick 2018; Yankey 2019); and a series of compounded stressors without an identifiable recurrent event (James 2020; Leventhal 2015). No study enrolled participants formally diagnosed with mental disorders as per our exclusion criteria.

Interventions and comparators

The trials compared interventions involving humane, supportive, and practical help covering both a social and a psychological dimension versus a control condition.

Afifi 2010 delivered the "Qaderoon" (We are Capable) intervention, a social skill‐building intervention based on stress inoculation training, improving social awareness and social problem‐solving, and positive youth development programme.

Berger 2018 delivered the "ERSAE‐Stress‐Prosocial" (ESPS), a universal school‐based programme, divided into two sets of strategies – stress‐reduction interventions and prosocial interventions (i.e. perspective‐taking, empathy training, mindfulness, and compassion‐cultivating practices).

Dhital 2019 implemented a teacher‐mediated school‐based intervention, which falls under the second layer of intervention as outlined in Inter‐Agency Standing Committee (IASC) guidelines.

Diab 2015 delivered the "Teaching Recovery Techniques" (TRT) intervention, where relaxation exercises and sleep hygiene are deployed to attune hyperarousal symptoms, manipulation of mental imagery to gain control of intrusive symptoms, and graded exposure techniques are trained to deal with avoidance symptoms. The TRT involves symbolic elements of play, drawing, writing, and narrating, as well as psychoeducation about normal and worrying trauma responses.

The content and organisation of the psychosocial intervention in Dybdahl 2001 were based on two different sources: 1. therapeutic discussion groups for traumatised women that had been held during the war, and 2. the "International Child Development Program" (ICDP). The objectives of the ICDP are to influence the caregiver's positive experience with the child, promote sensitive emotional expressive communication, promote enriching, and stimulating interaction.

James 2020 delivered the "mental health integrated disaster preparedness intervention", which utilises an experiential approach, including facilitated discussion, space for sharing personal experiences and exchange of peer‐support, establishing safety and practising coping skills targeting disaster‐related distress, and hands‐on training in disaster preparedness and response techniques for use by participants in their own lives and to support other community members.

Leventhal 2015 deployed an intervention developed for females only. Through the "Girls First Resilience Curriculum" girls used methods from positive psychology, social‐emotional learning, and life skills as a foundation for problem‐solving and conflict resolution, drawing from restorative practices. Girls then learned coping skills, building on their character strengths and drawing from other positive psychology skills, such as finding benefits in difficult situations ("benefit finding"); and emotional intelligence skills such as identifying and managing difficult emotions.

Maalouf 2020 deployed the "FRIENDS program", a universal, preventive, cognitive‐behavioural, school‐based intervention.

Miller 2020 and Miller 2023 deployed the "Caregiver Support Intervention" (CSI), focusing on caregiver well‐being, strengthening parenting under conditions of adversity, and relaxation techniques.

O'Callaghan 2014 delivered a psychosocial intervention based on three components: 1. ChuoChaMaisha, a youth life skills leadership programme developed and piloted in Tanzania; 2. Mobile Cinema clips: narrative, fictional films, produced and created in the local language to address stigma and discrimination and model how young people, parents, and the village community could welcome formerly abducted children back into their communities; and 3 relaxation technique scripts used in trauma‐focused cognitive behavioural therapy.

Panter‐Brick 2018 delivered the "Advancing Adolescents" programme, an eight‐week programme of structured activities informed by a profound stress attunement (PSA) framework. The PSA approach is a community‐based, non‐clinical programme of psychosocial care to meet the psychosocial needs of at‐risk children and improve social interactions with participatory approaches. It focusses on the practice of attunement, for developing safe emotional spaces, managing stressors, and establishing healthy relationships.

Yankey 2019 delivered the "Life Skills Training" (LST) intervention, which included techniques of brainstorming, role‐playing, and group discussion.

Paraprofessionals (i.e. trained lay counsellors; community health workers) delivered almost all the interventions in the trials and at a group level. Control conditions were waiting list in eight trials (Afifi 2010; Diab 2015; James 2020; Maalouf 2020; Miller 2020; Miller 2023; O'Callaghan 2014; Panter‐Brick 2018), no intervention (i.e. school as usual) in four trials (Berger 2018; Dhital 2019; Leventhal 2015; Yankey 2019), and CAU in one trial (Dybdahl 2001).

Outcomes

All RCTs provided data for at least one outcome. Six studies provided data for the outcome 'mental well‐being' (Afifi 2010; Diab 2015; Dybdahl 2001; Leventhal 2015; Miller 2020; Miller 2023; 4052 participants), five studies provided data for the outcome 'prosocial behaviour' (Berger 2018; Diab 2015; Maalouf 2020; O'Callaghan 2014; Panter‐Brick 2018; 1633 participants), two studies provided data for the outcome 'resilience' (Leventhal 2015; Panter‐Brick 2018; 2774 participants), while the outcomes of 'functioning' (Berger 2018; 183 participants), 'coping' (Yankey 2019; 300 participants), and 'hope' (Dhital 2019; 1070 participants) were each informed by one study. No study provided data on the prespecified outcome of 'quality of life'.

All but one (Yankey 2019) study provided data on the secondary outcome of 'acceptability' (7390 participants).

Follow‐up data were available for the outcomes of 'mental well‐being' (six‐month follow‐up: Afifi 2010, 258 participants; three‐month follow‐up: Miller 2023, 480 participants), 'functioning' (eight‐month follow‐up: Berger 2018, 183 participants), 'resilience' (11‐month follow‐up: Panter‐Brick 2018, 299 participants), and 'prosocial behaviour' (eight‐month follow‐up: Berger 2018; 11‐month follow‐up: Panter‐Brick 2018, 483 participants).

Funding sources

Ten studies were funded by grants from foundations, academic institutions, or NGOs (Afifi 2010; Dhital 2019; Diab 2015; Dybdahl 2001; James 2020; Leventhal 2015; Maalouf 2020; Miller 2020; Miller 2023; Panter‐Brick 2018). In one case, the funder wished to remain anonymous (O'Callaghan 2014). One study received no funding (Berger 2018), and the source of funding for one study was unknown (Yankey 2019).

Excluded studies

Of the 61 studies (72 reports) initially selected as potentially relevant, we excluded 23 studies because of ineligible population (participants with a diagnosis of a mental health condition or scoring above a scale cut‐off). We excluded studies that employed rating scales with cut‐off scores at baseline as an inclusion criterion. As cut‐offs could be considered as a proxy of a diagnosis, we excluded these studies because we reasoned they were not really meant to be focused on promotion (but more on prevention or treatment). We excluded 10 studies due to ineligible design (not an RCT or incorrect randomisation procedure); nine studies because of inapplicable setting (no humanitarian crisis in LMICs); two studies because they tested active interventions against each other (ineligible comparison); and one study because it implemented an ineligible intervention (Figure 1). For further information, see Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Studies awaiting classification

We classified two studies as awaiting classification: one is not yet recruiting (ACTRN12618000892213), and another is completed but results are not yet available (NCT03760627). See Characteristics of studies awaiting classification table.

Ongoing studies

We classified one study as ongoing (Jansen 2022). This is a cluster‐RCT designed to test the efficacy of a psychosocial intervention to promote social dignity among participants in post‐genocide Rwanda. The study started in March 2022. See Characteristics of ongoing studies table.

Risk of bias in included studies

See Characteristics of included studies table. For graphical representations of overall risk of bias in included studies, see Figure 2. We summarised the risk of bias judgements across different studies for each of the domains listed in Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Researchers described generation of a random sequence that we considered leading to low risk of bias in all 13 studies.

Regarding allocation concealment, we considered four trials at low risk of bias (Dhital 2019; Miller 2020; Miller 2023; O'Callaghan 2014), and the nine remaining RCTs at unclear risk of bias as they did not describe allocation concealment.

Blinding

Participants (both personnel and study participants) were aware of whether they had been assigned to an intervention group or a control group in all but two trials (Afifi 2010; Panter‐Brick 2018); therefore, we rated 11 studies at high risk of performance bias. Afifi 2010 and Panter‐Brick 2018 were at unclear risk of performance bias because there was insufficient information to make a judgement.

We rated six trials at low risk of bias when researchers described blinded assessment of outcomes (Berger 2018; Dybdahl 2001; Miller 2020; Miller 2023; O'Callaghan 2014; Panter‐Brick 2018). We rated two trials at high risk of bias, as the assessors were described as likely to have been aware of participant allocation (James 2020; Leventhal 2015). The remaining five trials were at unclear risk of bias because there was insufficient information to make a judgement (Afifi 2010; Dhital 2019; Diab 2015; Maalouf 2020; Yankey 2019).

Incomplete outcome data

The risk of attrition bias was low in nine studies, as researchers clearly reported low dropout rates (Afifi 2010; Berger 2018; Dhital 2019; Diab 2015; Dybdahl 2001; Leventhal 2015; Miller 2020; Miller 2023; O'Callaghan 2014). In three other cases there was a high dropout rate (more than 20% of participants); therefore, we rated these studies at high risk of attrition bias (James 2020; Maalouf 2020; Panter‐Brick 2018). Yankey 2019 did not provide information on study dropouts, therefore we rated this study at unclear risk of bias.

Selective reporting

Although none of the trials reported information on study protocols, four manuscripts provided the trial registration number, and thus were at low risk of bias (Dhital 2019; James 2020; Miller 2020; Miller 2023). One study did not report data for the control group at follow‐up and for this reason, was rated at high risk of bias (O'Callaghan 2014). The remaining eight trials were at unclear risk of bias because there was insufficient information to make a judgement (Afifi 2010; Berger 2018; Diab 2015; Dybdahl 2001; Leventhal 2015; Maalouf 2020; Panter‐Brick 2018; Yankey 2019).

Other potential sources of bias

We considered the following additional items in our risk of bias evaluation.

Therapist qualification

Most of the trials delivered their psychosocial intervention through trained lay counsellors, or by trained volunteer adults from local communities. In two trials, the intervention was delivered by specialised personnel (Diab 2015; Maalouf 2020). The interventions delivered through the task‐sharing modality and the interventions delivered by professionals were considered at low risk of bias (nine trials: Berger 2018; Dhital 2019; Diab 2015; Dybdahl 2001; Leventhal 2015; Maalouf 2020; Miller 2020; Miller 2023; Panter‐Brick 2018). Four trials that did not specify the qualification of the intervention facilitators were at unclear risk of bias (Afifi 2010; James 2020; O'Callaghan 2014; Yankey 2019). No study was at high risk of bias.

Therapist/investigator allegiance

We rated the risk of intervention facilitator or investigator allegiance as unclear in all trials because of lack of information reported in the manuscripts.

Intervention fidelity