Abstract

Spermine synthase is an aminopropyltransferase that adds an aminopropyl group to the essential polyamine spermidine to form tetraamine spermine, needed for normal human neural development, plant salt and drought resistance, and yeast CoA biosynthesis. We functionally identify for the first time bacterial spermine synthases, derived from phyla Bacillota, Rhodothermota, Thermodesulfobacteriota, Nitrospirota, Deinococcota, and Pseudomonadota. We also identify bacterial aminopropyltransferases that synthesize the spermine same mass isomer thermospermine, from phyla Cyanobacteriota, Thermodesulfobacteriota, Nitrospirota, Dictyoglomota, Armatimonadota, and Pseudomonadota, including the human opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Most of these bacterial synthases were capable of synthesizing spermine or thermospermine from the diamine putrescine and so possess also spermidine synthase activity. We found that most thermospermine synthases could synthesize tetraamine norspermine from triamine norspermidine, that is, they are potential norspermine synthases. This finding could explain the enigmatic source of norspermine in bacteria. Some of the thermospermine synthases could synthesize norspermidine from diamine 1,3-diaminopropane, demonstrating that they are potential norspermidine synthases. Of 18 bacterial spermidine synthases identified, 17 were able to aminopropylate agmatine to form N1-aminopropylagmatine, including the spermidine synthase of Bacillus subtilis, a species known to be devoid of putrescine. This suggests that the N1-aminopropylagmatine pathway for spermidine biosynthesis, which bypasses putrescine, may be far more widespread than realized and may be the default pathway for spermidine biosynthesis in species encoding L-arginine decarboxylase for agmatine production. Some thermospermine synthases were able to aminopropylate N1-aminopropylagmatine to form N12-guanidinothermospermine. Our study reveals an unsuspected diversification of bacterial polyamine biosynthesis and suggests a more prominent role for agmatine.

Keywords: bacterial metabolism, biosynthesis, polyamine, spermidine, spermine, thermospermine, N1-aminopropylagmatine, norspermidine, norspermine

Polyamines are amino acid–derived, small polycations synthesized by bacteria, archaea, eukaryotes, and some viruses (1, 2, 3). Most linear polyamines are synthesized from the diamine putrescine (Put) by sequential transfer of one or more aminopropyl groups (Fig. 1) mediated by a small family of aminopropyltransferases (APTs) that have a common evolutionary origin, including spermidine (Spd), spermine (Spm), and thermospermine (Tspm) synthases (4, 5, 6, 7, 8). The aminopropyl groups are donated by decarboxylated S-adenosylmethionine (dcAdoMet) (9), formed by S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase (AdoMetDC) (Fig. 1A). It is likely that Spd synthase (SpdSyn) was present in the Last Universal Common Ancestor of all life (10), indicating the primordial role of Spd in early cellular physiology. In eukaryotes and archaea, Spd is essential for cell growth and proliferation due to its role in the deoxyhypusine/hypusine posttranslational modification of translation factor eIF5a/aIF5a (11, 12, 13). The essentiality of Spd in bacterial growth varies between species (14), likely reflecting the diversification of Spd function across evolutionary time.

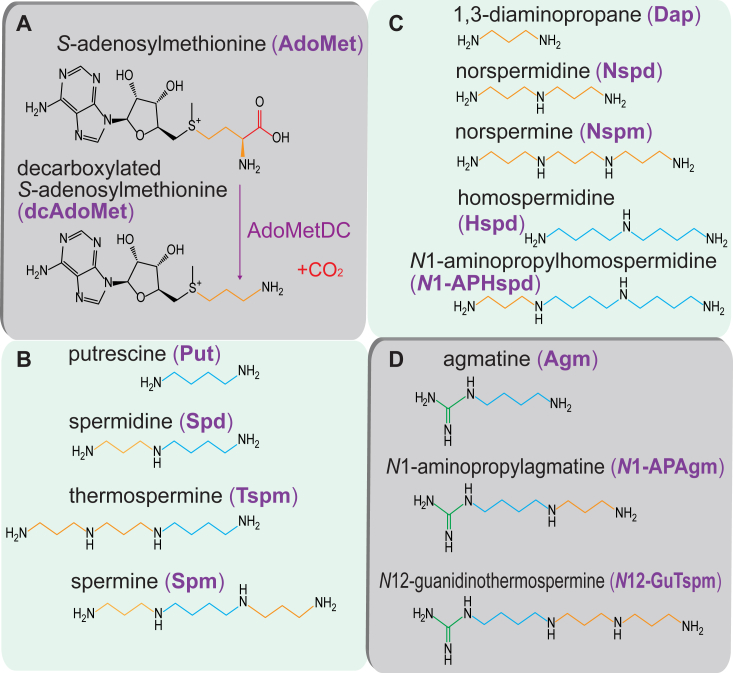

Figure 1.

Aminopropyltransferase substrates and products.A, production of decarboxylated S-adenosylmethionine (dcAdoMet) from S-adenosylmethionine (AdoMet) by S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase (AdoMetDC). The donated aminopropyl group is shown in tan. B, consecutive aminopropylations produce spermidine (Spd) from putrescine (Put, blue) and spermine (Spm) and thermospermine (Tspm) from Spd. C, consecutive aminopropylations produce norspermidine (Nspd) from 1,3-diaminopropane (Dap), norspermine (Nspm) from Nspd, and N1-aminopropylhomospermidine (N1-APHspd) from homospermidine (Hspd). D, consecutive aminopropylations produce N1-aminopropylagmatine (N1-APAgm) from agmatine (Agm) and N12-guanidinothermospermine (N12-GuTspm) from N1-APAgm. The guanidino group is shown in green.

In eukaryotes, in addition to the triamine Spd, the tetraamine Spm (Fig. 1B) has evolved from Spd by aminopropylation of the N8-aminobutyl side of Spd, performed by Spm synthase (SpmSyn). Spm biosynthesis has evolved independently at least three times in eukaryotes: in metazoa, fungi, and plants (15, 16). The function of Spm is less understood than that of Spd; it is not universally present in all eukaryotes but it is known to regulate potassium channels and NMDA receptors (17). Mutations of the human SpmSyn result in severe mental developmental defects (18), although it is not clear whether the problem is due to Spm deficiency or Spd excess (19). In the model flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana, Spm is not required for normal growth but mutants of SpmSyn are highly sensitive to drought and salt stress (20, 21). In the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, SpmSyn is not required for growth unless the growth medium lacks pantothenate (22). Spm is oxidized by yeast FMS1 to produce 1,3-diaminopropane (Fig. 1C), which is converted to β-alanine, pantothenate, and then co-enzyme A (23), revealing that Spm is required for de novo CoA biosynthesis.

The fact that Spm biosynthesis has evolved independently at least three times in eukaryotes suggests selective pressures to evolve Spm biosynthesis for diverse cellular processes. In addition to Spm, eukaryotes of the algal and plant lineage produce a structural isomer of Spm with the same mass—Tspm, which is synthesized from Spd by addition of an aminopropyl group to the N1-aminopropyl side of Spd (Fig. 1B) (24). A mutant of TspmSyn (acl5) in A. thaliana, which was originally misidentified as a SpmSyn (25, 26), exhibits severe growth abnormalities, dwarfism, and aberrant vascular development. The structural analog norspermine (Fig. 1C) is able to partially replace Tspm function in growth and development (27). Tspm has been shown recently to be essential for correct organ development in the nonvascular plant Marchantia polymorpha (28).

It has been proposed that bacteria do not encode SpmSyn (15), but many phylogenetically diverse bacteria, especially thermophiles, have been found to contain Spm (29, 30, 31, 32). The APT of hyperthermophile Thermus thermophilus exhibits a very relaxed substrate specificity and produces a large number of longer polyamines by aminopropylation of diverse polyamine substrates (33, 34). However, no specific SpmSyn has been identified in bacteria. Furthermore, previous measurements of Spm in bacteria did not usually distinguish between Spm and Tspm due to their similar chromatographic behavior. Similarly, no specific TspmSyn has been identified in bacteria, although the APT of Thermus thermophilus is regarded as a bifunctional N1-aminopropylagmatine/Tspm synthase (7, 33). Given the known presence of Spm and Tspm in bacteria, we sought to determine whether bacteria encode functional Spm and Tspm synthases.

Results

Selecting candidates for bacterial spermine and thermospermine synthases

Bacteria that accumulate Spm/Tspm have been identified in a long-term effort to use polyamine profiles for chemotaxonomy (29, 30, 31, 32). We selected diverse bacterial species that were found by Hamana et al. to accumulate Spm/Tspm and interrogated their genomes for APT-encoding genes. Most species we selected encode pairs of APT homologs, but some encode single (“singleton”) APT proteins (Table S1). As Escherichia coli does not produce Spm/Tspm, it provides a useful platform for detection of SpmSyn/TspmSyn activity. The selected genes were synthesized for the expression in E. coli BL21 from plasmid pETDuet-1. As positive controls for Spm, Tspm, and Spd production, the biochemically validated eukaryotic SpmSyns of Homo sapiens (35) and flowering plant A. thaliana (36), TspmSyns of A. thaliana (25, 26) and chlorophyte single-celled alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (37), and SpdSyns of H. sapiens, A. thaliana, and corresponding homolog from C. reinhardtii were synthesized (Table S1) and expressed in E. coli BL21-derived strains.

Some of the bacterial genes were encoded by species from the Bacillota phylum: Thermanaerobacter brockii (1 APT, thermophile (T)), Thermosyntropha lipolytica (2 APTs, T), Thermobrachium celere (1 APT, T), Sulfobacillus acidophilus (2 APTs, T), Geobacillus stearothermophilus (2 APTs, T), and Desulfosporosinus orientis (2 APTs, mesophile (M)). Others were encoded by phyla Cyanobacteriota, Arthrospira platensis (Spirulina, 2 APTs, M); Thermodesulfobacteriota, Thermodesulfobacterium thermophilum (2 APTs, T); Thermotogota, Thermotoga maritima (1 APT, T); Deinococcota, Oceanithermus profundus (1 APT, T) and Thermus thermophilus (1 APT, T); Nitrospirota, Thermodesulfovibrio yellowstonii (2 APTs, T); Rhodothermota, Rhodothermus marinus (2 APTs, T); and Dictyoglomota, Dictyoglomus thermophilum (2 APTs, T). We chose a singleton APT encoded by the genome of cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa (M), a species that was found not to accumulate Spm/Tspm (32) but the APT is closely homologous to the two APTs encoded by A. platensis. In addition to species investigated by Hamana et al., we also selected a number of mesophilic species among many based on the presence of two APT homologs in a genome: Desulfoarculus baarsii (Thermodesulfobacteriota), Fimbriimonas ginsengsoli (Armatimonadota), Heliorestis convoluta (Bacillota), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 (Pseudomonadota). We also selected three mesophilic bacterial species encoding single divergent APTs: Leptospirillum ferrodiazotrophum (Nitrospirota); and Candidatus Pelagibacter ubique HTCC1062 and Ca. Pelagibacter sp. HTCC7211 (Pseudomonadota) that each encode a fused N-terminal AdoMetDC (class 1b) (38) and C-terminal APT.

Functional identification of bacterial spermine and thermospermine synthases

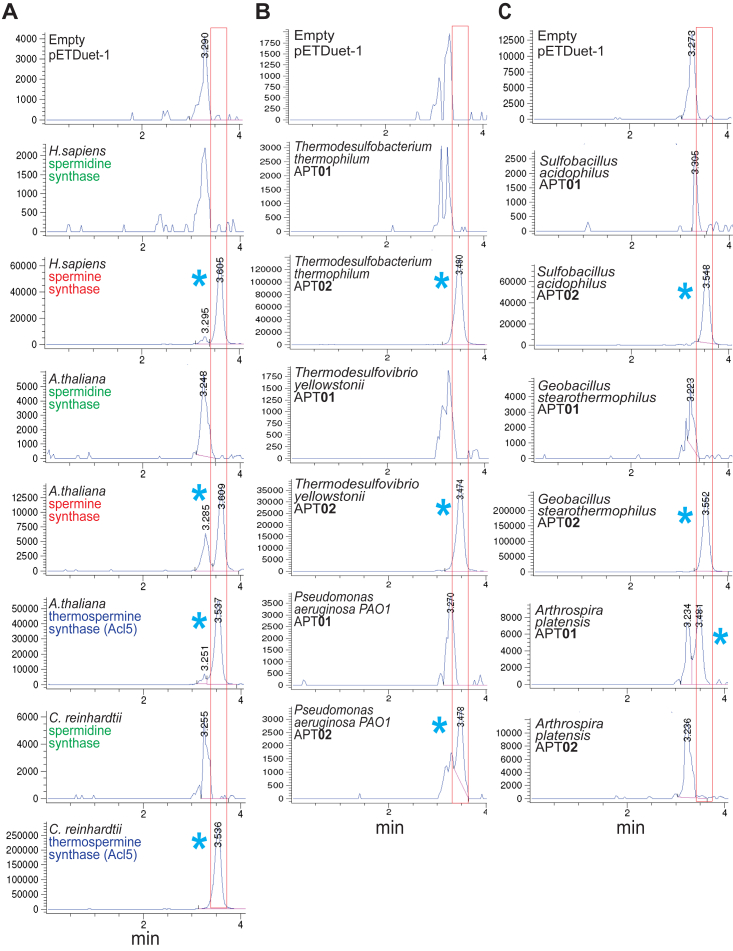

Spm is much more efficiently N-acetylated by bacterial Spd N-acetyltransferase (SpeG) than is Spd (39). We therefore expressed each APT gene in a ΔspeG deletion strain of E. coli BL21 to avoid N-acetylation of any Spm or Tspm that might be produced. After growth in polyamine-free, chemically-defined M9 medium and induced expression of each gene, polyamines were extracted from cells and benzoylated for analysis by LC-MS. The relative efficiency of each APT enzyme for producing Spm/Tspm cannot be directly compared using our approach due to possible differences in steady-state expression level of each APT gene expressed from pETDuet-1. The control BL21speG strain expressing the empty pETDuet-1 plasmid contains Put and Spd, and we looked for the production of tetrabenzoylated Spm/Tspm (extracted ion chromatogram (EIC) mass tolerance window 619:620 Da). In this LC-MS system, the Spm/Tspm identical mass structural isomers are not clearly distinguished chromatographically. Eukaryotic H. sapiens and A. thaliana SpmSyns and A. thaliana and C. reinhardtii Tspmsyns produced Spm/Tspm when expressed in BL21speG (Fig. 2), validating the utility of E. coli for detecting Spm/Tspm synthase-encoding genes (Table 1). The A. thaliana, C. reinhardtii, and H. sapiens SpdSyns did not produce detectable Spm/Tspm. Within the pairs of bacterial APT homologs analyzed, in each case, one gene produced a peak corresponding to Spm/Tspm (Figs. 2 and 3, Table 1). Among the singleton APTs, those encoded by Thermus thermophilus, Oceanithermus profundus, and the two Ca. Pelagibacter species produced Spm/Tspm (Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

Expression of aminopropyltransferases in Escherichia coli BL21speG.A–C, samples in each vertical panel represent independent experiments (group A, group B, group C). APT01 and APT02 represent individual genes from pairs of aminopropyltransferase homologs encoded in the same genome. Shown are the Extracted Ion Chromatograms for tetrabenzoylated Spm/Tspm (EIC = 619.02:620.02). The red box outlines the position of eluted tetrabenzoylated Spm/Tspm detected by LC-MS. The blue asterisk indicates the presence of peaks for tetrabenzoylated Spm/Tspm (m/z 619.6). E. coli BL21speG synthesizes spermidine. Aminopropyltransferase genes were expressed from pETDuet-1. The vertical axis represents arbitrary units of ion intensity. APT, aminopropyltransferase.

Table 1.

Spermidine and spermine/thermospermine synthase activities of aminopropyltransferase homologs

| Species (Phylum) | Protein [Genbank acc.no.] | SpdSyn | Spm/TspmSyn |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arthrospira platensis (Cyanobacteriota) | APT01 [BAI92260] | Y | Y |

| Arthrospira platensis (Cyanobacteriota) | APT02 [BAI90257] | Y | N |

| Desulfarculus baarsii (Thermodesulfobacteriota) | APT01 [WP_013259899] | Y | Y |

| Desulfarculus baarsii (Thermodesulfobacteriota) | APT02 [WP_013257411] | Y | N |

| Desulfosporosinus orientis (Bacillota, Clostridia) | APT01 [WP_014182696] | Y | N |

| Desulfosporosinus orientis (Bacillota, Clostridia) | APT02 [WP_014182917] | Y | Y |

| Dictyoglomus thermophilum (Dictyoglomota) | APT01 [WP_012546901] | Y | N |

| Dictyoglomus thermophilum (Dictyoglomota) | APT02 [WP_012547113] | Y | Y |

| Fimbriimonas ginsengisoli (Armatimonadota) | APT01 [WP_025227485] | Y | Y |

| Fimbriimonas ginsengisoli (Armatimonadota) | APT02 [WP_025225227] | Y | N |

| Geobacillus stearothermophilus (Bacillota, Bacilli) | APT01 [WP_049624640] | Y | N |

| Geobacillus stearothermophilus (Bacillota, Bacilli) | APT02 [WP_033014118] | Y | Y |

| Heliorestis convoluta (Bacillota, Clostridia) | APT01 [WP_153726121] | Y | T |

| Heliorestis convoluta (Bacillota, Clostridia) | APT02 [WP_153723875] | Y | Y |

| Leptospirillum ferrodiazotrophum (Nitrospirota) | APT [EES53973] | Y | ∗ |

| Microcystis aeruginosa (Cyanobacteriota) | APT [WP_002790803] | Y | N |

| Oceanithermus profundus (Deinococcota) | APT [WP_013456826] | Y | Y |

| Ca. Pelagibacter sp. HTCC7211 (α-Proteobacteria) | APT [WP_008544956] | Y | Y |

| Ca. Pelagibacter ubique HTCC1062 (α-Proteobacteria) | APT [WP_011282223] | Y | Y |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 (γ-Proteobacteria) | APT01 [NP_250378] | Y | N |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 (γ-Proteobacteria) | APT02 [NP_253462] | T | Y |

| Rhodothermus marinus (Rhodothermota) | APT01 [WP_012844841] | Y | ∗ |

| Rhodothermus marinus (Rhodothermota) | APT02 [WP_012844658] | Y | Y |

| Sulfobacillus acidophilus (Bacillota, Clostridia) | APT01 [AEJ41924] | Y | N |

| Sulfobacillus acidophilus (Bacillota, Clostridia) | APT02 [AEJ39917] | Y | Y |

| Thermoanaerobacter brockii (Bacillota, Clostridia) | APT [WP_003867984] | Y | N |

| Thermobrachium celere (Bacillota, Clostridia) | APT [CDF58371] | Y | N |

| Thermodesulfobacterium thermophilum (Thermodesulfobacteriota) | APT01 [WP_022855228] | Y | N |

| Thermodesulfobacterium thermophilum (Thermodesulfobacteriota) | APT02 [WP_022855378] | Y | Y |

| Thermodesulfovibrio yellowstonii (Nitrospirota) | APT01 [ACI21680] | Y | N |

| Thermodesulfovibrio yellowstonii (Nitrospirota) | APT02 [ACI21563] | N | Y |

| Thermosyntropha lipolytica (Bacillota, Clostridia) | APT01 [SHG87240] | Y | N |

| Thermosyntropha lipolytica (Bacillota, Clostridia) | APT02 [SHG61007] | Y | Y |

| Thermotoga maritima (Thermotogota) | APT [AGL49579] | Y | N |

| Thermus thermophilus (Deinococcota) | APT [WP_011172918] | Y | Y |

| Arabidopsis thaliana (Streptophyta) | SpdSyn [Q9ZUB3] | Y | N |

| Arabidopsis thaliana (Streptophyta) | SpmSyn [BAH19534] | Y | Y |

| Arabidopsis thaliana (Streptophyta) | TspmSyn [OAO96167] | T | T |

| Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (Chlorophyta) | SpdSyn [XP_001702843] | Y | N |

| Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (Chlorophyta) | TspmSyn [ADF43120] | Y | Y |

| Homo sapiens (Metazoa) | SpdSyn [NP_003123] | Y | N |

| Homo sapiens (Metazoa) | SpmSyn [CAA88921] | T | T |

Aminopropyltransferase activities determined in Escherichia coli BL21speG and BL21speE. The asterisk indicates APTs that produce Spm/Tspm in E. coli BL21speE but not in BL21speG.

Abbreviations: APT, aminopropyltransferase; N, no activity; SpdSyn, spermidine synthase; SpmSyn, spermine synthase, TspmSyn, thermospermine synthase; T, trace activity; Y, activity.

Figure 3.

Expression of aminopropyltransferases in Escherichia coli BL21speG.A–D, samples in each vertical panel represent independent experiments (group A, group B, group C, group D). APT01 and APT02 represent individual genes from pairs of aminopropyltransferase homologs encoded in the same genome; others represent singleton aminopropyltransferases. See Figure 2 for further description. APT, aminopropyltransferase.

To determine whether the APT homologs that did not produce Spm/Tspm were functional SpdSyns, all genes were then expressed in a SpdSyn gene deletion strain (ΔspeE) of E. coli BL21, which is devoid of Spd. The EICs for tribenzoylated Spd (m/z 458:459) and tetrabenzoylated Spm/Tspm from the cell extracts of BL21speE expressing the different APT genes are shown in Figs. S1–S3. All APTs that did not produce Spm/Tspm in BL21speG produced Spd in BL21speE, indicating SpdSyn activity (Table 1). Three of these SpdSyns were singleton APTs encoded by thermophilic species found previously to accumulate Spm/Tspm (30): Thermotoga maritima, Thermoanaerobacter brockii, and Thermobrachium celere. However, in the study of Hosoya et al. (30), each species was grown at temperatures of at least 60 °C, which may be required for Spm/Tspm synthase activity in those species. Notably, all Spm/Tspm synthases except those from Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 and Thermodesulfovibrio yellowstonii produced Spm/Tspm in BL21speE, that is, they were able to synthesize Spm/Tspm from Put. This indicates that the Spm/Tspm synthases synthesize Spd from Put and then synthesize Spm/Tspm from Spd. This was also the case for the eukaryotic A. thaliana SpmSyn and C. reinhardtii TspmSyn but to a lesser degree for the H. sapiens SpmSyn and A. thaliana TspmSyn (Fig. S1). Therefore, the Spm/Tspm synthases do not necessarily require a dedicated partner SpdSyn to be able to produce Spm/Tspm from Put, except for those of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 and Thermodesulfovibrio yellowstonii.

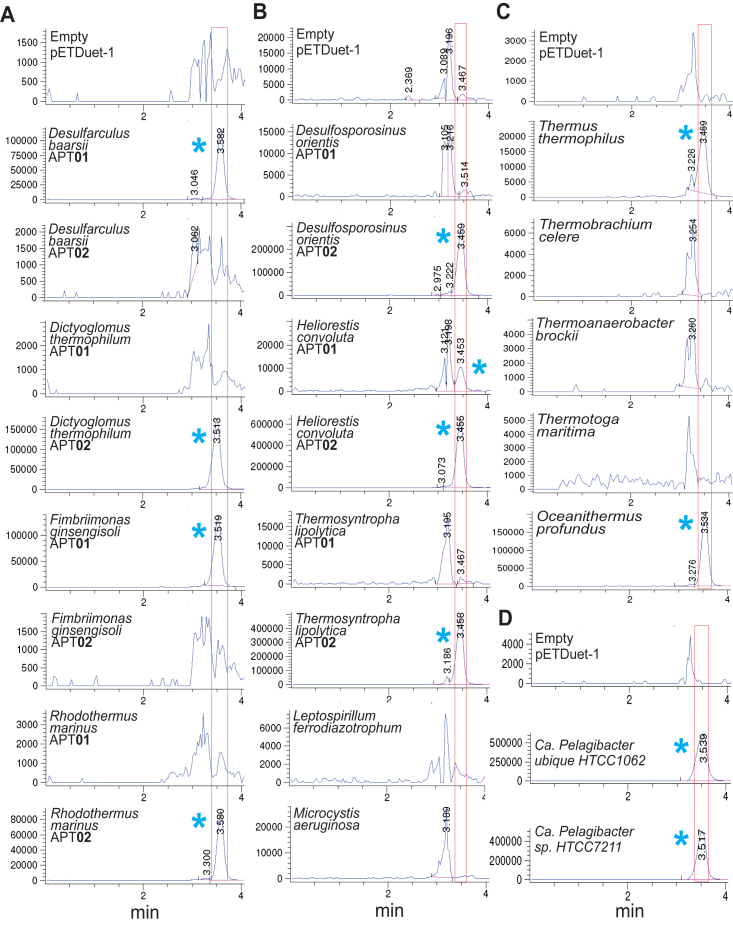

Of the singleton APTs, the proteins from Oceanithermus profundus and Thermus thermophilus produced Spm/Tspm in BL21speE, that is, they are able to produce Spm/Tspm from Put. The singleton APTs from Thermobrachium celere, Thermoanaerobacter brockii, and Thermotoga maritima produce Spd but not Spm/Tspm in BL21speE. In contrast, the APT from Leptospirillum ferrodiazotrophum and APT01 from Rhodothermus marinus, which did not produce Spm/Tspm in BL21speG, generated detectable amounts of Spm/Tspm in BL21speE, which suggests that high levels of Spd in BL21speG may inhibit Spm/Tspm synthase activity of these APTs. The AdoMetDC-APT fusion proteins encoded by Ca. Pelagibacter ubique HTCC1062 and Ca. Pelagibacter sp. HTCC7211 produce Spm/Tspm when expressed in BL21speE (Fig. 4). They produce Spd when expressed in an AdoMetDC gene deletion strain (ΔspeD) of BL21, confirming that the N-terminal AdoMetDC domain is functional (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Expression of Ca.pelagibacter species S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase-aminopropyltransferase fusion proteins genes in Escherichia coli BL21speD and BL21speE. Shown are the extracted ion chromatograms for tribenzoylated Spd (EIC = 457.94:498.94) and tetrabenzoylated Spm/Tspm (EIC = 619.02:620.02). The blue box outlines the position of Spd, and the red box outlines the position of Spm/Tspm detected by LC-MS. All genes were expressed from pETDuet-1. No Spd or Spm/Tspm is synthesized in either BL21speD or BL21speE with an empty pETDuet-1 expression vector. All strains were grown and processed in parallel.

To determine whether each bacterial tetraamine (Spm/Tspm) synthase was specifically a Spm or Tspm synthase, we then developed an LC-MS/MS approach that chromatographically separated tetrabenzoylated Spm and Tspm. Using these conditions, commercially obtained Tspm and Spm eluted at 10.92 and 11.63 min, respectively (Fig. S4), and multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode was used to detect the tetrabenzoylated Spm and Tspm having the same MS transitions as they eluted off from the HPLC column at different retention times. We monitored the following transitions in MRM positive polarity mode, 619.228/497.2, 619.228/162, and 619.228/77 for both tetrabenzoylated Spm and Tspm. The quantifier ion was 619.228/497.2 while 619.228/162 and 619.228/77 were used as the qualifier ions. The quantifier ion was used to determine the analyte response using the peak area calculation, while the qualifier ions were used to help identify the analyte.

Analysis by LC-MS/MS of the eukaryotic Spm/Tspm synthases expressed in BL21speG indicated that the eukaryotic H. sapiens and A. thaliana SpmSyns are highly specific and do not produce any detectable Tspm (Table 2). The C. reinhardtii TspmSyn (Acl5) is also highly specific, whereas the A. thaliana TspmSyn (Acl5) produces a small amount of Spm in addition to Tspm. Detectable Spm was identified in the BL21speG strain containing an empty expression vector. It represented approximately 0.035% (area under the peak) of the Spm produced by expression of the H. sapiens SpmSyn. To assess whether the low level of Spm in the control BL21speG strain represented contamination or endogenous production of Spm by E. coli, we analyzed Tspm and Spm levels in BL21, BL21speE, and BL21speG expressing the empty pETDuet-1 plasmid (Table 3). A small amount of Tspm and approximately twice as much Spm was detected in BL21speG, whereas no Tspm or Spm was detected in BL21speE, indicating that the native E. coli SpdSyn produces a previously unnoticed low level of Spm and an even lower level of Tspm. The background level of Spm in the parental E. coli BL21 strain represents approximately 0.01% of the amount of Spm produced by the H. sapiens SpmSyn in BL21speG (Table 3).

Table 2.

LC-MS/MS analysis of thermospermine and spermine production by validated aminopropyltransferases in Escherichia coli BL21speG

| Aminopropyltransferase [GenBank protein acc. no] | Synthase activity | AUP 10.92 min (Tspm) | AUP 11.63 min (Spm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Empty pETDuet-1 | None | ND | 5.21 × 104 |

| Homo sapiens SpdSyn [NP_003123] | Spermidine | ND | 3.55 × 104 |

| H. sapiens SpmSyn [CAA88921] | Spermine | ND | 1.48 × 108 |

| Arabidopsis thaliana SpdSyn1 [Q9ZUB3] | Spermidine | ND | 9.49 × 103 |

| A. thaliana SpmSyn [BAH19534] | Spermine | ND | 1.26 × 107 |

| A. thaliana Acl5 [OAO96167] | Thermospermine | 3.79 × 107 | 4.32 × 105 |

| Chlamydomonas reinhardtii SpdSyn [XP_001702843] | Spermidine | ND | 5.79 × 104 |

| C. reinhardtii Acl5 [ADF43120] | Thermospermine | 3.54 × 108 | ND |

All genes expressed from pETDuet-1.

Abbreviations: Acl5, Acaulis 5/thermospermine synthase; AUP, area under the peak with elution time; ND, not detected; SpdSyn, spermidine synthase; Spm, spermine; SpmSyn, spermine synthase; Tspm, thermospermine.

Table 3.

LC-MS/MS analysis of background thermospermine and spermine levels detected in different E. coli BL21 strains

| Aminopropyltransferase and Escherichia coli BL21 strain | Synthase activity | AUP 10.92 min (Tspm) | AUP 11.63 min (Spm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Empty pETDuet-1 in BL21 | Native spermidine | ND | 1.93 × 104 |

| Empty pETDuet-1 in BL21speE | None | ND | ND |

| Empty pETDuet-1 in BL21speG | Native spermidine | 1.21 × 104 | 2.56 × 104 |

| Homo sapiens SpmSyn [CAA88921] | Spermine | ND | 1.88 × 108 |

| Chlamydomonas reinhardtii Acl5 [ADF43120] | Thermospermine | 2.85 × 108 | ND |

Tspm (thermospermine), Spm (spermine), SpdSyn (spermidine synthase), SpmSyn (spermine synthase), Acl5 (Acaulis 5/thermospermine synthase), AUP (area under the peak with elution time) from parent ion/daughter ion 619.228/497.200 (619.228 = tetrabenzoylated spermine/thermospermine). Heterologous genes expressed from pETDuet-1.

Abbreviations: ND, not detected; speE, spermidine synthase; speG, spermidine N1-acetyltransferase.

Bacterial Spm/Tspm synthases were expressed in either BL21speE or BL21speG according to which strain allowed the greater accumulation of Spm/Tspm. Using an arbitrary criterion of at least 10-fold more production of either Spm or Tspm, most of the bacterial Spm/Tspm synthases were either specifically Spm or Tspm synthases. The specific Tspm synthases were identified from Arthrospira platensis, Thermodesulfobacterium thermophilum, Thermodesulfovibrio yellowstonii, Dictyoglomus thermophilum, Fimbriimonas ginsengisoli, Thermus thermophilus, and surprisingly, the opportunistic human pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 (Table 4). Specific SpmSyns were identified from Geobacillus stearothermophilus, Sulfobacillus acidophilus, Desulfoarculus baarsii, Rhodothermus marinus APT01 (which is primarily a SpdSyn), Desulfosporosinus orientis, Heliorestis convoluta, Thermosyntropha lipolytica, and Oceanithermus profundus (Table 4). APTs from Rhodothermus marinus (APT02), Ca. Pelagibacter sp. HTCC7211, and Ca. P. ubique HTCC1062 could be considered as bifunctional Spm/Tspm synthases.

Table 4.

LC-MS/MS detection of thermospermine and spermine production by bacterial aminopropyltransferases in Escherichia coli BL21 strains

| Species | Aminopropyltransferase | AUP Tspm |

AUP Spm |

Synthase activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10.92 min | 11.63 min | |||

| Group 1 | ||||

| Empty pETDuet-1 in BL21 | Endogenous SpdSyn | ND | 1.93 × 104 | Spd |

| Empty pETDuet-1 in BL21speE | None | ND | ND | None |

| Empty pETDuet-1 in BL21speG | Endogenous SpdSyn | ND | 2.56 × 104 | Spd |

| Homo sapiens in BL21speG | SpmSyn [CAA88921] | ND | 1.88 × 108 | Spm |

| Chlamydomonas reinhardtii in BL21speG | Acl5 [ADF43120] | 2.85 × 108 | ND | Tspm |

| Group 2 (in BL21speG) | ||||

| Empty pETDuet-1 | Endogenous SpdSyn | ND | 2.73 × 105 | Spd |

| Geobacillus stearothermophilus | APT01 [WP_049624640] | ND | 1.47 × 105 | Spd |

| Geobacillus stearothermophilus | APT02 [WP_033014118] | 2.90 × 104 | 1.12 × 109 | Spm |

| Sulfobacillus acidophilus | APT01 [AEJ41924] | ND | 1.03 × 105 | Spd |

| Sulfobacillus acidophilus | APT02 [AEJ39917] | ND | 1.75 × 108 | Spm |

| Arthrospira platensis | APT01 [BAI92260] | 2.84 × 106 | 1.03 × 105 | Tspm |

| Arthrospira platensis | APT02 [BAI90257] | 1.26 × 105 | 2.30 × 105 | Spd |

| Group 3 (in BL21speG) | ||||

| Empty pETDuet-1 | Endogenous SpdSyn | ND | 2.91 × 104 | Spd |

| Thermodesulfobacterium thermophilum | APT02 [WP_022855378] | 1.37 × 108 | 4.11 × 105 | Tspm |

| Thermodesulfovibrio yellowstonii | APT02 [ACI21563] | 9.50 × 107 | 3.28 × 105 | Tspm |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 | APT02 [NP_253462] | 3.72 × 106 | 4.82 × 104 | Tspm |

| Group 4 (in BL21speG) | ||||

| Desulfarculus baarsii | APT01 [WP_013259899] | ND | 1.45 × 109 | Spm |

| Dictyoglomus thermophilum | APT02 [WP_012547113] | 1.26 × 107 | 1.04 × 105 | Tspm |

| Fimbriimonas ginsengisoli | APT01 [WP_025227485] | 9.26 × 108 | 3.19 × 106 | Tspm |

| Rhodothermus marinus | APT01 [WP_012844841] | 3.96 × 104 | 3.33 × 108 | Spm |

| Rhodothermus marinus | APT02 [WP_012844658] | 2.71 × 108 | 1.46 × 109 | Spm>Tspm |

| Group 5 (in BL21speE) | ||||

| Empty pETDuet-1 | None | ND | 3.19 × 104 | Spd |

| Desulfosporosinus orientis | APT02 [WP_014182917] | 1.06 × 104 | 5.55 × 108 | Spm |

| Heliorestis convoluta | APT02 [WP_153723875] | ND | 8.54 × 108 | Spm |

| Thermosyntropha lipolytica | APT01 [SHG87240] | 4.90 × 104 | 3.03 × 105 | Spm>Tspm |

| Thermosyntropha lipolytica | APT02 [SHG61007] | ND | 5.28 × 108 | Spm |

| Leptospirillum ferrodiazotrophum | Single APT [EES53973] | 1.68 × 105 | 9.05 × 106 | Spm |

| Group 6 (in BL21speG) | ||||

| Empty pETDuet-1 | Endogenous SpdSyn | ND | 7.88 × 103 | Spd |

| Thermus thermophilus | Single APT [WP_011172918] | 8.23 × 106 | 1.63 × 105 | Tspm>>Spm |

| Oceanithermus profundus | Single APT [WP_013456826] | 3.87 × 103 | 6.80 × 107 | Spm |

| Ca. Pelagibacter sp. HTCC7211 | Single APT [WP_008544956] | 4.95 × 107 | 7.92 × 107 | Spm/Tspm |

| Ca. Pelagibacter ubique HTCC1062 | Single APT [WP_011282223] | 4.18 × 107 | 8.07 × 107 | Spm/Tspm |

The area under the peak (AUP) for the tetrabenzoylated tetraamine 619.228/497.200 daughter ion is provided for thermospermine (elutes at 10.92 min) and spermine (11.52 min). Each group of E. coli strains were grown and analyzed by LC-MS/MS independently; within groups, all strains were grown and analyzed in parallel.

Abbreviations: APT, aminopropyltransferase; Spd, spermidine; speE, spermidine synthase; speG, spermidine N-acetyltransferase; Spm, spermine; Tspm, thermospermine.

Production of norspermine and N1-aminopropylhomospermidine

SpmSyns transfer an aminopropyl group from dcAdoMet (Fig. 1A) to the N8-(aminobutyl) side of Spd to form Spm, whereas TspmSyns transfer the aminopropyl group to the N1-(aminopropyl) side of Spd to form Tspm (Fig. 1B). The symmetrical triamines norspermidine (Nspd) and homospermidine (Hspd) consist of only aminopropyl or aminobutyl moieties, respectively (Fig. 1C). We sought to determine whether the SpmSyns and TspmSyns would prefer Hspd or Nspd as substrates when expressed in the E. coli Spd-devoid BL21speE. Transformed strains were grown in polyamine-free M9 medium with added 0.5 mM Nspd or Hspd. Relative uptake efficiencies of each polyamine were not determined. The products of N-aminopropylation of Nspd and Hspd are norspermine (Nspm) and N1-aminopropylhomospermidine (N1-APHspd), respectively (Fig. 1C). Benzoylated polyamines from cell extracts were analyzed by LC-MS, and the EICs for tetrabenzoylated Nspm (m/z = 605) and tetrabenzoylated N1-APHspd (m/z = 634) are shown in Figs. S5–S7. The eukaryotic SpmSyns from A. thaliana and H. sapiens produced N1-APHspd but not Nspm, emphasizing their strict specificity for aminopropylating an aminobutyl but not an aminopropyl moiety (Table 5). Bacterial SpmSyns are also specific for aminobutyl moieties except for the APT from Oceanithermus profundus, which produced Nspm at a level of approximately 10% that of N1-APHspd. In contrast, the substrate specificity of TspmSyns is more complex, with the TspmSyns of Dictyoglomus thermophilum and Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 being strictly selective for Nspd over Hspd as substrates, whereas the other TspmSyns exhibit activity with both triamines. The TspmSyns from Arthrospira plantensis, Thermus thermophilus, and Fimbriimonas ginsengisoli are equally or more active with Hspd than Nspd. The singleton APT from Leptospirillum ferrodiazotrophum produced N1-APHspd, consistent with its SpmSyn activity. These data suggest that all investigated TspmSyns are potentially NspmSyns, if Nspd is present as a substrate.

Table 5.

Norspermidine and N1-aminopropylhomospermidine synthase activities of aminopropyltransferases

| Species (Phylum) | Protein [Genbank acc.no.] | Nspm | N1APHspd |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis thaliana (Streptophyta) | TspmSyn [OAO96167] | Y | T |

| Arabidopsis thaliana (Streptophyta) | SpmSyn [BAH19534] | N | Y |

| Arthrospira platensis (Cyanobacteriota) | TspmSyn [BAI92260] | Y | Y |

| Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (Chlorophyta) | TspmSyn [ADF43120] | Y | T |

| Desulfarculus baarsii (Thermodesulfobacteriota) | SpmSyn [WP_013259899] | N | Y |

| Desulfosporosinus orientis (Bacillota, Clostridia) | SpmSyn [WP_014182917] | N | Y |

| Dictyoglomus thermophilum (Dictyoglomota) | TspmSyn[WP_012547113] | Y | N |

| Fimbriimonas ginsengisoli (Armatimonadota) | TspmSyn [WP_025227485] | Y | Y |

| Geobacillus stearothermophilus (Bacillota, Bacilli) | SpmSyn [WP_033014118] | N | Y |

| Homo sapiens (Metazoa) | SpmSyn [Q9ZUB3] | N | Y |

| Heliorestis convoluta (Bacillota, Clostridia) | SpmSyn [WP_153723875] | N | Y |

| Leptospirillum ferrodiazotrophum (Nitrospirota) | SpdSyn [EES53973] | N | Y |

| Oceanithermus profundus (Deinococcota) | SpmSyn [WP_013456826] | Y | Y |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 (γ-Proteobacteria) | TspmSyn [NP_253462] | Y | N |

| Rhodothermus marinus (Rhodothermota) | SpmSyn [WP_012844841] | N | Y |

| Rhodothermus marinus (Rhodothermota) | TspmSyn [WP_012844658] | N | Y |

| Sulfobacillus acidophilus (Bacillota, Clostridia) | SpmSyn [AEJ39917] | N | Y |

| Thermodesulfob. thermophilum (Thermodesulfobacteriota) | TspmSyn [WP_022855378] | Y | Y |

| Thermodesulfovibrio yellowstonii (Nitrospirota) | TspmSyn [ACI21563] | Y | Y |

| Thermosyntropha lipolytica (Bacillota, Clostridia) | SpmSyn [SHG61007] | N | Y |

| Thermus thermophilus (Deinococcota) | APagmSyn [WP_011172918] | Y | Y |

| Arabidopsis thaliana (Streptophyta) | SpmSyn [BAH19534] | N | Y |

| Arabidopsis thaliana (Streptophyta) | TspmSyn [OAO96167] | Y | T |

| Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (Chlorophyta) | TspmSyn [ADF43120] | Y | T |

| Homo sapiens (Metazoa) | SpmSyn [CAA88921] | N | Y |

Aminopropyltransferase genes were expressed from pETDuet-1 in E. coli BL21speE grown with 0.5 mM norspermidine (Nspd) or homospermidine (Hspd). Based on data derived from Figs. S5–S7.

Abbreviations: APagmSyn, N1-aminopropylagmatine synthase; N, no activity; SpmSyn, spermidine synthase; T, trace activity; TspmSyn, thermospermine synthase; Y, synthase activity.

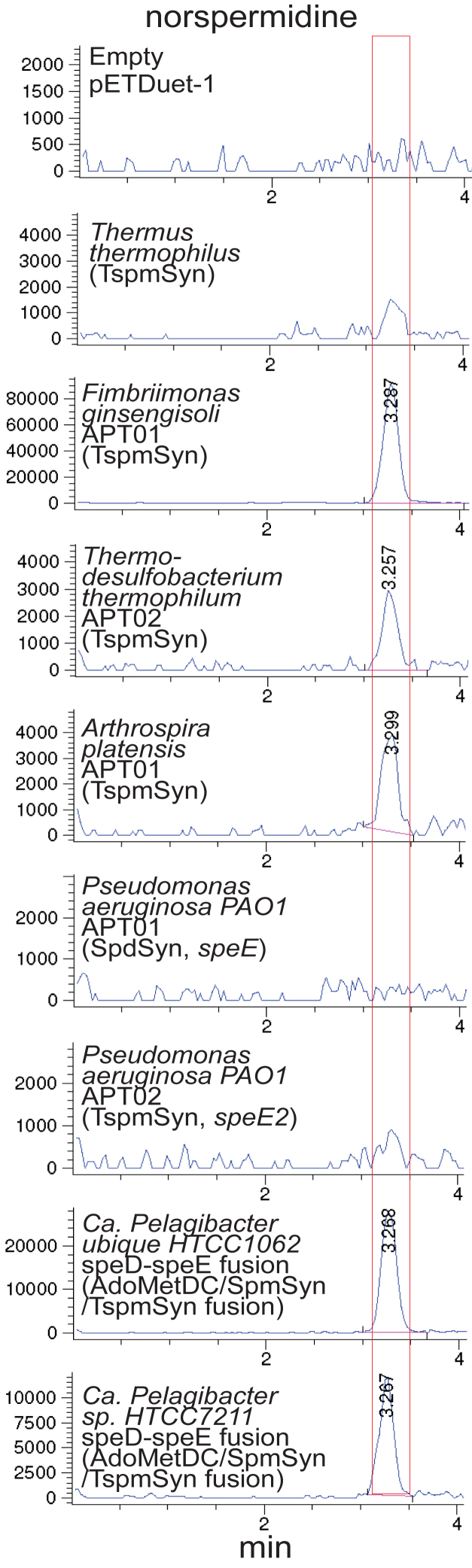

Production of norspermidine from 1,3-diaminopropane

Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 strain has been reported to produce Nspd from 1,3-diaminopropane (Dap) (Fig. 1C) and that Nspd production may participate in resistance to antibiotics (40). The gene suggested as the NspdSyn is PA4774 (speE2) (40), which is the gene we identified as encoding a TspmSyn. It is immediately downstream of a gene encoding a class 1b AdoMetDC (PA4773, SpeD2, AE004891, 160 aa). In addition to this class 1b AdoMetDC (38), PAO1 also encodes a class 1a AdoMetDC (PA0654, SpeD, WP_003101641, 264 aa). The P. aeruginosa PAO1 SpdSyn and TspmSyn exhibit 60% and 36% a.a. identity to the E. coli K12 SpdSyn, respectively. Because of the importance of P. aeruginosa as an opportunistic human pathogen, we examined whether either of the two APTs of P. aeruginosa were able to produce Nspd from Dap. TspmSyns aminopropylate aminopropyl moieties, so we also analyzed a selection of other bacterial TspmSyns. The genes were expressed in Spd-devoid BL21speE grown in M9 medium containing 1.0 mM Dap. TspmSyn of Fimbriimonas ginsengisoli, Ca. P. ubique HTCC1062, and Ca. Pelagibacter sp. HTCC7211 produced relatively large quantities of Nspd from Dap (Fig. 5). These TspmSyns are therefore potentially NspdSyns if the substrate Dap is present. Smaller amounts were produced by the TspmSyns of Thermodesulfobacterium thermophilum and Arthrospira platensis but no detectable Nspd was produced by the APT of Thermus thermophilus or the SpdSyn or TspmSyn of P. aeruginosa PAO1. It is possible that in P. aeruginosa PAO1, the Tspm produced by PA 4774 (TspmSyn, SpeE2) is oxidized by an unknown oxidase to Nspd, as observed with the vascular plant Selaginella lepidophylla (41) or by converted to Nspd by a dehydrogenase.

Figure 5.

Norspermidine production by aminopropyltransferases expressed in Escherichia coli BL21speE grown with 1.0 mM 1,3-diaminopropane. Shown are the LC-MS extracted ion chromatograms for tribenzoylated Nspd (EIC = 443.92:444.92). The red box outlines the position of Nspd detected by LC-MS. All genes were expressed from pETDuet-1. No Nspd, Spd, or Spm/Tspm is synthesized in either BL21speD or BL21speE with an empty pETDuet-1 expression vector. All strains were grown and processed in parallel.

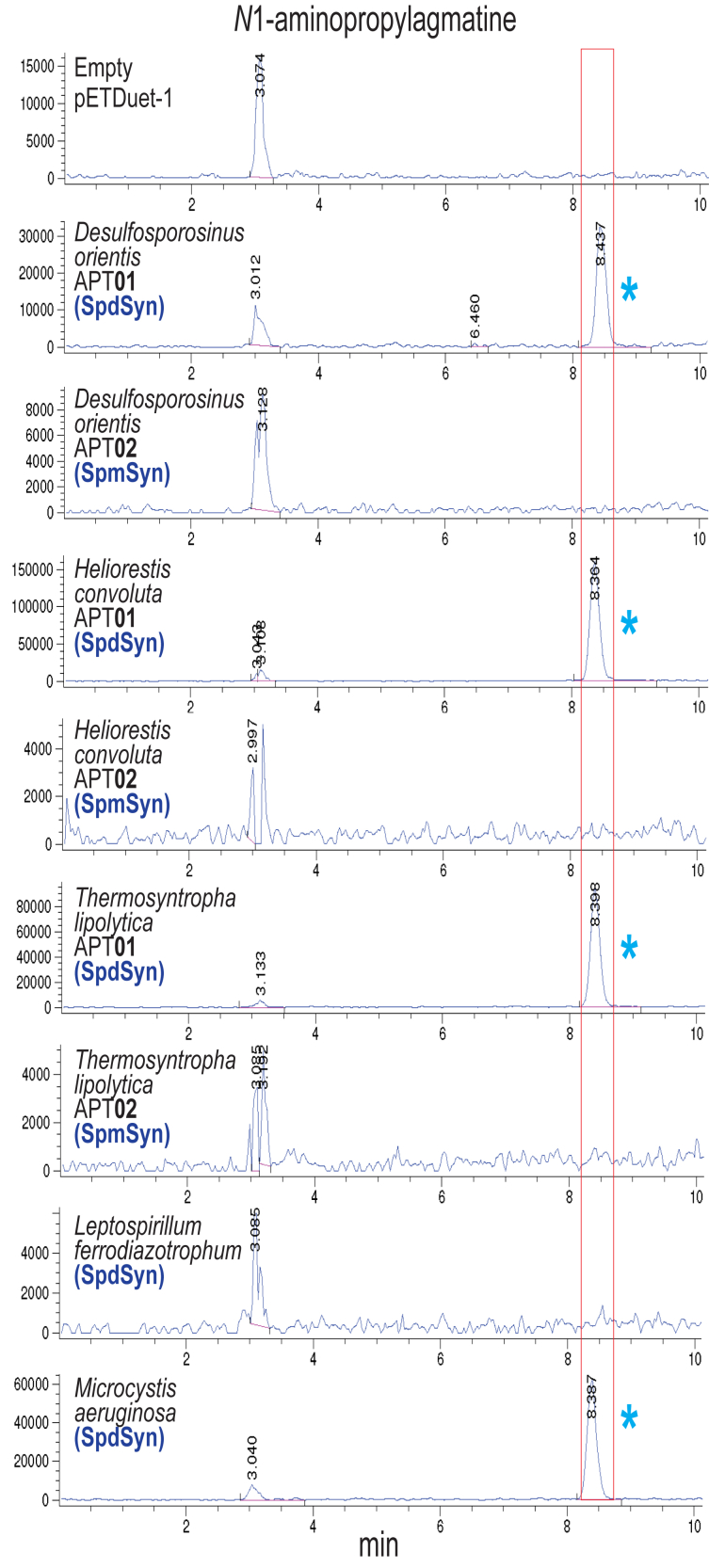

Most spermidine synthases are N1-aminopropylagmatine synthases

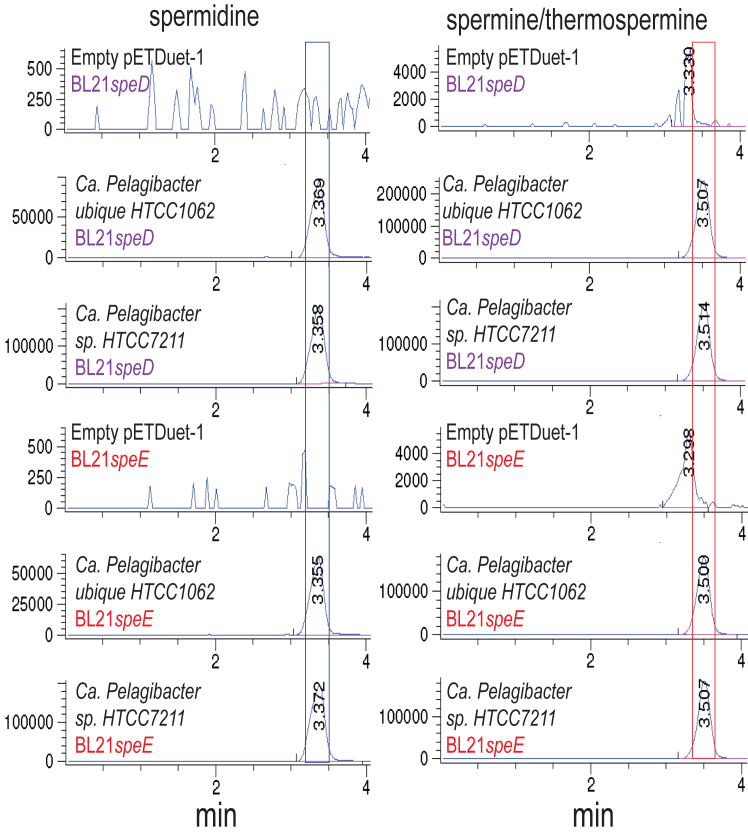

We have considered the aminopropylation of Put to form Spd and of Spd to form either Spm or Tspm. Another form of aminopropylation has been described for the bacterium Thermus thermophilus (33) and the archaeon Thermococcus kodakarensis (42): the aminopropylation of agmatine (Agm) to form N1-aminopropylagmatine (N1-APAgm) (Fig. 1D). In this pathway, N1-APAgm is converted to Spd by an agmatinase homolog (N1-aminopropylagmatinase). The single APT of Thermus thermophilus aminopropylates both Agm and Spd (33). We noticed that some of the SpdSyns we expressed in BL21speG produced a peak corresponding to tetrabenzoylated N1-APAgm (m/z 604.2) (Fig. 6). For example, Desulfosporosinus orientis, Heliorestis convoluta, and Thermosynthropha lipolytica, which encode two APTs each, the SpdSyn but not the SpmSyn produced N1-APAgm in BL21speG. The SpdSyn of Microcystis aeruginosa also produced N1-APAgm.

Figure 6.

N1-aminopropylagmatine production by aminopropyltransferases expressed in Escherichia coli BL21speG. Shown are the LC-MS extracted ion chromatograms for tetrabenzoylated N1-aminopropylagmatine (N1-APAgm, EIC = 603.98:604.98). The red box outlines the position of N1-APAgm, and the blue asterisk indicates the presence of a peak for N1-APAgm. Genes were expressed from pETDuet-1. All strains were grown and processed in parallel.

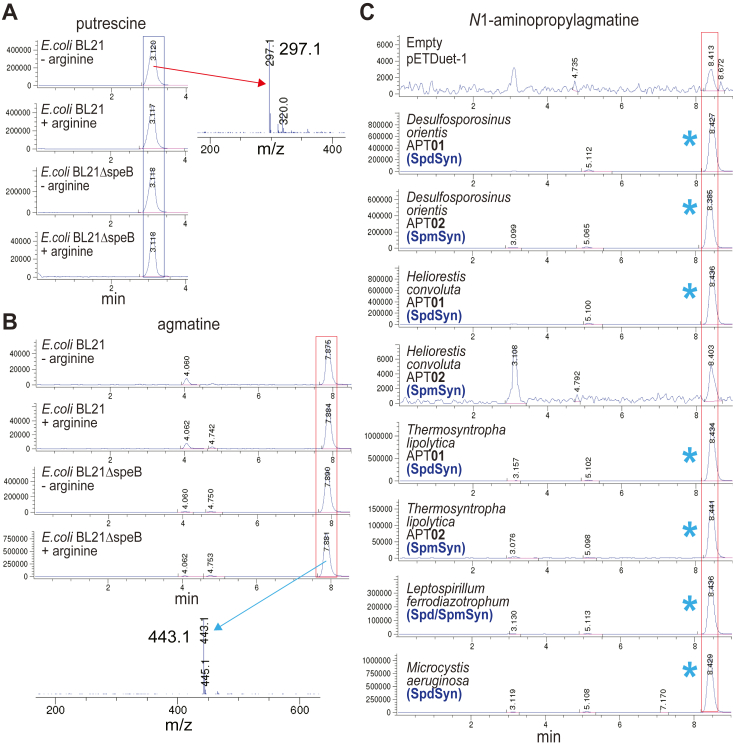

We decided to more fully explore the aminopropylation of Agm by the APTs described so far in our study. As a positive control, we included the N1-APAgm synthase from Thermococcus kodakarensis, and as negative controls, the SpdSyns of E. coli, Bacillus subtilis (43), and an uncultivated bacteriophage (3). To facilitate this analysis, by increasing Agm levels in E. coli, a gene deletion of agmatinase in BL21 was created (BL21ΔspeB). Genes were expressed in E. coli BL21speB grown with 300 μM arginine, which partially represses flux through the arginine biosynthesis pathway, thereby reducing Put but increasing Agm levels (Fig. 7). Using this approach, Put decreased by 10-fold (Fig. 7A) and Agm levels were increased approximately 20-fold (Fig. 7B). Unexpectedly, we found that all SpdSyns except those from P. aeruginosa PAO1 and the uncultivated Caudovirales bacteriophage produced N1-APAgm (Figs. 7C, S8 and S9). Whereas the SpmSyns of Desulfosporosinus orientis and Thermosynthropha lipolytica did not produce N1-APAgm in BL21speG, they did produce N1-APAgm in BL21speB grown with 300 μM arginine, although less than produced by the corresponding SpdSyns. Overexpression of the E. coli SpdSyn produced only a relative trace of N1-APAgm compared to, for example, SpdSyn of Bacillus subtilis, which produced approximately as much N1-APAgm in this system as the Thermococcus kodakarensis N1-APAgm synthase. The N1-APAgm synthase activity of the Bacillus subtilis SpdSyn (SpeE) enzyme was entirely unexpected.

Figure 7.

Expression of aminopropyltransferases in Escherichia coli BL21speB. All genes were expressed from pETDuet-1. A, LC-MS extracted ion chromatograms for dibenzoylated Put (EIC = 296.85:297.85). The blue box outlines the position of Put. Cultures of E. coli BL21 and BL21speB were grown with ± 300 μM L-arginine and expressed the empty pETDuet-1 plasmid. All strains were grown and processed in parallel. The inset shows the mass spectrum for the dibenzoylated putrescine peak. B, LC-MS extracted ion chromatograms for tribenzoylated Agm (EIC = 442.9:443.9). The red box outlines the position of Agm. Cultures of E. coli BL21 and BL21speB were grown with ± 300 μM L-arginine and expressed the empty pETDuet-1 plasmid. All strains were grown and processed in parallel. The inset shows the mass spectrum for the tribenzoylated agmatine peak. C, LC-MS extracted ion chromatograms for tetrabenzoylated N1-aminopropylagmatine (N1-APAgm, EIC = 603.98:604.98) in the cell extracts of E. coli BL21speB expressing aminopropyltransferase genes from pETDuet-1 and grown with 300 μM L-arginine. The red box outlines the position N1-APAgm. All strains were grown and processed in parallel. The blue asterisk indicates the presence of peaks for N1-APAgm (m/z 604.4). Put, putrescine.

We reasoned that species encoding an N1-APAgmSyn should also encode an L-arginine decarboxylase to produce Agm. If the purpose of N1-APAgm production is to bypass Put in Spd biosynthesis, as is thought to be the case for Thermus thermophilus (33) and T. kodakarensis (42), the presence of L-ornithine decarboxylase, that converts ornithine directly to Put, would undermine that purpose. The genomes of the species encoding the APTs analyzed in the current study were interrogated for all the known forms of L-arginine and L-ornithine decarboxylases (44, 45). Most species encoding N1-APAgmSyn activity were found to encode only L-arginine decarboxylases, albeit from four different protein folds (Table S2). Consistent with the lack or low level of N1-APAgmSyn activity from the APTs of P. aeruginosa PAO1 and E. coli, these two species each encode L-arginine and L-ornithine decarboxylases. Exceptions are Thermodesulfovibrio yellowstonii and Thermotoga maritima, which encode N1-APAgmSyn activity but possess only L-ornithine decarboxylase homologs. The genome of Oceanithermus profundus does not appear to encode a recognizable L-arginine or L-ornithine homolog, which suggests a novel form of these enzymes remains to be discovered or else this organism would have to take up exogenous Agm or Put.

In contrast to the SpdSyn homologs, the Spm and Tspm synthases did not produce N1-APAgm except for the SpmSyns of Desulfosporosinus orientis, Thermosyntropha lipolytica, Rhodothermus marinus, and Geobacillus stearophilus. The first two of these did not produce N1-APAgm when expressed in BL21speG (Fig. 6). No TspmSyn produced N1-APAgm except the APT of Thermus thermophilus, which was originally identified as a bifunctional N1-APAgm synthase/TspmSyn (33). The production of N1-APAgm was confirmed using LC-high resolution mass spectrometry (LC-HRMS), and selected species are shown in Fig. S10.

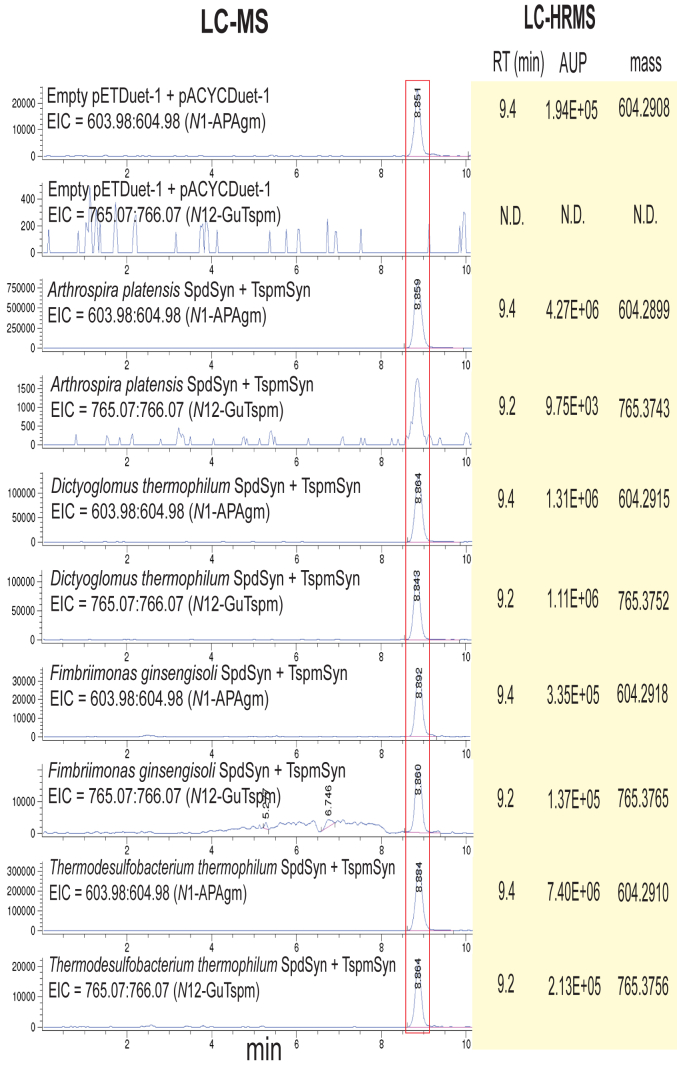

Biosynthesis of N12-guanidinothermospermine

Production of N1-APAgm by SpdSyn homologs raised the possibility that some bacterial species encoding TspmSyn might aminopropylate the aminopropyl side of N1-APAgm synthesized by the SpdSyn/N1-APAgmSyn to produce (N1-aminopropyl)- N1-APAgm, that is, N12-guanidinothermospermine (Fig. 1D) that might potentially then be hydrolyzed by a ureohydrolase to Tspm. We selected SpdSyn/N1-APAgmSyn and TspmSyn pairs encoded by Arthrospira platensis, Dictyoglomus thermophilum, Fimbriimonas ginsengisoli, and Thermodesulfobacterium thermophilum for co-expression in E. coli BL21speB.

To further increase the level of Agm and decrease Put available for this reaction sequence, BL21speB was grown with 10-fold more L-arginine (3 mM) to repress flux from L-glutamate to L-ornithine. Under this growth condition, the native SpdSyn of E. coli BL21speB produced easily detectable levels of N1-APAgm, as the tetrabenzoylated form (Fig. 8A). However, with BL21speB expressing empty vectors, no N12-guanidinothermospermine was detected (pentabenzoylated form EIC = 765.07:766.07). Similarly, the APT pair from Arthrospira platensis did not produce detectable N12-guanidinothermospermine. In contrast, the other APT pairs produced easily detectable levels of N12-guanidinothermospermine, particularly so for Dictyoglomus thermophilum. The tetrabenzoylated N1-APAgm and pentabenzoylated N12-guanidinothermospermine eluted at the same time from the LC column, so the fraction eluting at 8.86 to 8.88 min contained the masses of both metabolites (Fig. S11). To further confirm the identities of tetrabenzoylated N1-APAgm and pentabenzoylated N12-guanidinothermospermine, the experiment was repeated, and benzoylated cell extracts were analyzed by LC-HRMS (Fig. 8B). The exact masses of tetrabenzoylated N1-APAgm and pentabenzoylated N12-guanidinothermospermine were detected.

Figure 8.

LC-MS detection of N1-aminopropylagmatine and N12-guanidinothermospermine. SpdSyn/N1-APAgmSyn in pETDuet-1 and TspmSyn in pACYCDuet-1 were coexpressed in E. coli BL21speB and grown in the presence of 3 mM L-arginine. The left-hand panel shows the extracted ion chromatograms from the LC-MS detection of tetrabenzoylated N1-aminopropylagmatine (N1-APAgm, EIC = 603.98:604.98) and pentabenzoylated N12-guanidinothermospermine (N12-GuTspm, EIC = 765.07:766.07). The peaks for N1-APAgm and N12-GuTspm elute at similar times and are highlighted by the red box. In an independent experiment, the same cultures were grown again for analysis by LC-high resolution MS. In the right-hand panel, the retention times, area under the peak (AUP), and accurate mass of tetrabenzoylated N1-APAgm and pentabenzoylated N12-GuTspm are shown for the corresponding cultures in the left-hand panel. N.D., not detected.

Prediction of aminopropyltransferase function from amino acid sequence

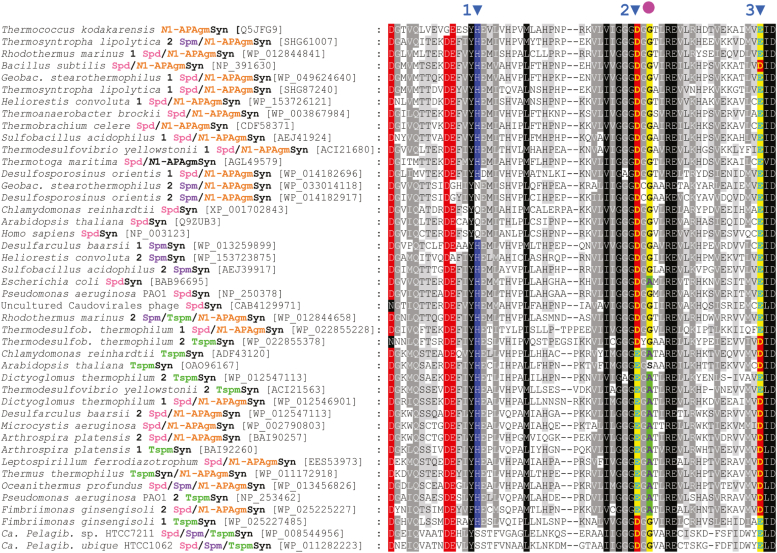

Currently, there is only one SpmSyn and one TspmSyn published X-ray crystal structure (6, 8), although structures exist for the substrate-flexible APTs of Thermus thermophilus (7) and the crenarchaeote Pyrobaculum calidifontis (46). Active site residues for the SpdSyn, SpmSyn, and TspmSyn proteins of the leguminous plant Medicago trunculata have been compared to identify key differences (8). APTs bind dcAdoMet and a polyamine substrate in the active site cleft. Three amino acids involved in binding dcAdoMet differentiate the plant TspmSyn from SpdSyn and SpmSyn (8). In the M. trunculata TspmSyn, these amino acids correspond to His85, Glu109, and Asp129 (marked as motifs 1, 2, & 3, respectively in Fig. 9). The Glu109 position (motif 2) is found in a highly conserved sequence hhhhGGG(D/E)G(G/A), where h represents a small hydrophobic residue. The presence of a Glu rather than an Asp in motif 2 was thought previously to discriminate TspmSyn from SpdSyn and SpmSyn (15, 16). Comparison of the APTs analyzed in our current study suggests that the His85 position in motif 1 is not informative. In contrast, all APTs from our study acting principally as SpmSyns possess an Asp in motif 2 and Glu in motif 3. Furthermore, the position 2 amino acids downstream of the Asp in motif 2 is always a Gly in SpmSyns (D(G/C)G). This pattern distinguishes SpmSyns from Spd/N1-APAgmSyns and TspmSyns, with the caveat that the SpmSyns in our study are phylogenetically skewed towards the Bacillota phylum. APTs exhibiting primarily TspmSyn activity possess a Glu in motif 2, except for the TspmSyns of Fimbriimonas ginsengisoli and Thermodesulfobacterium thermophilum that have an Asp. SpdSyn/N1-APAgmSyns are not distinguished by any of the motifs.

Figure 9.

Amino acid sequence alignment of the analyzed aminopropyltransferases. The alignment covers the region corresponding to the Escherichia coli SpeE (SpdSyn) amino acid positions 50 to 110. Blue arrows indicate significant motifs. The red circle indicates the position 2 amino acids downstream of motif 2.

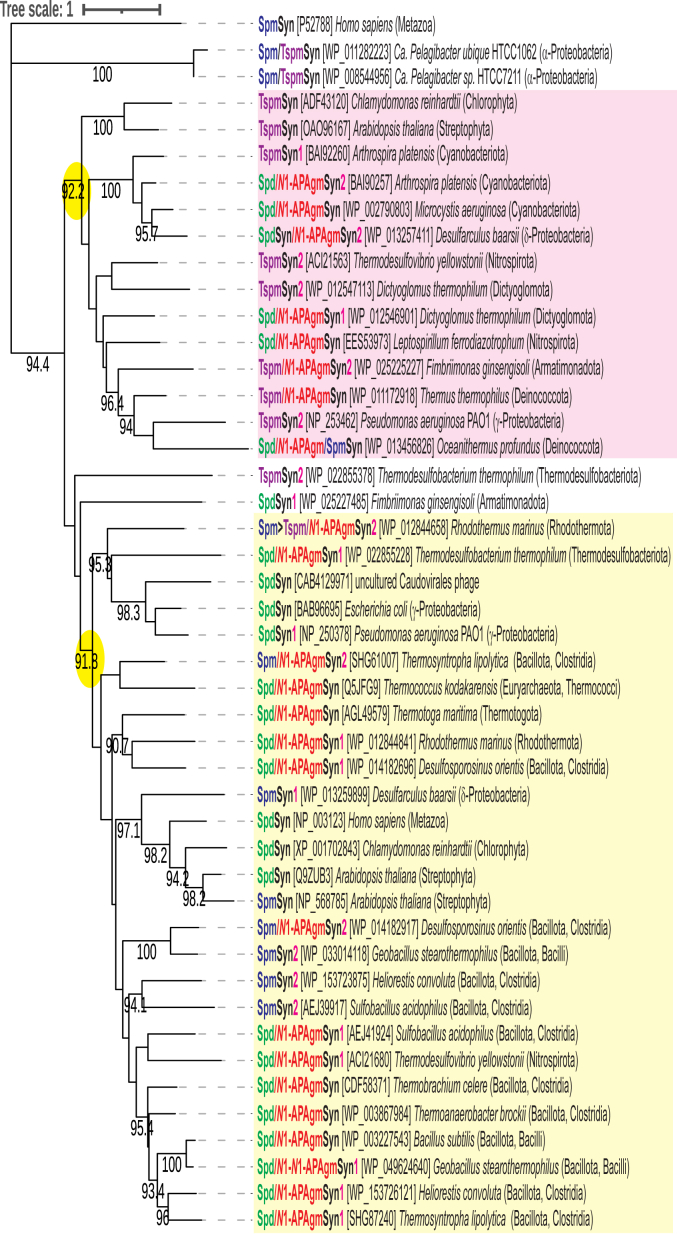

A phylogenetic tree of the APT proteins shows that there are two, well supported clades (Fig. 10). One clade consists of TspmSyns interspersed with Spd/N1-APAgmSyns, and the other consists of SpdSyns and Spd/N1-APAgmSyns interspersed with SpmSyns. For genomes encoding pairs of APTs, there are strong candidates for horizontal acquisition of one of the genes, for example, each member of the APT pairs of Thermodesulfovibrio yellowstonii and Desulfarculus baarsii are found in separate clades. In contrast, the two APTs of Arthrospira platensis and of Dictyoglomus thermophilum are found close together on the Maximum Likelihood tree, indicating gene duplication and neofunctionalization. The APT pairs of Heliorestis convoluta, Geobacillus stearothermophilus, and Sulfobacillus acidophilus are found in the same subclade. They may represent a common ancestral gene duplication and neofunctionalization followed by vertical divergence.

Figure 10.

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of the analyzed aminopropyltransferases. TspmSyn (thermospermine synthase), SpmSyn (spermine synthase), SpdSyn (spermidine synthase), Spd/N1-APAgmSyn (spermidine/N1-aminopropylagmatine synthase). Numbers after enzyme name indicate aminopropyltransferase pairs; no number indicates a singleton aminopropyltransferase. Phyla are indicated in parentheses after the species name. The pink box covers TspmSyns and Spd/N1-APAgmSyns; yellow box covers SpmSyns, SpdSyns, and Spd/N1-APAgmSyns. Numerical values represent percentage bootstrap support above 90% from 1000 ultrafast bootstrap analyses. The scale bar represents the average number of amino acid substitutions per site.

Discussion

It has been proposed that bacteria do not encode SpmSyn (15); however, our study has functionally identified for the first time bona fide SpmSyns in bacteria. They are found in diverse phyla: Geobacillus stearothermophilus, Sulfobacillus acidophilus, Desulfosporosinus orientis, Heliorestis convoluta, and Thermosynthropha lipolytica (Bacillota phylum, formerly Firmicutes); Rhodothermus marinus (Rhodothermota); Desulfoarculus baarsii (Thermodesulfobacteriota); Leptospirillum ferrodiazotrophum (Nitrospirota), Oceanithermus profundus (Deinococcota), and Ca. Pelagibacter species (Pseudomonadota, class α-Proteobacteria). We have also functionally identified TspmSyns from equally diverse phyla: Arthrospira platensis (Cyanobacteriota); Thermodesulfobacterium thermophilum (Thermodesulfobacteriota); Thermodesulfovibrio yellowstonii (Nitrospirota); Dictyoglomus thermophilum (Dictyoglomota); Fimbriimonas ginsengisoli (Armatimonadota), Ca. Pelagibacter species (Pseudomonadota, class α-Proteobacteria), Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 (class γ-Proteobacteria), and we have reconfirmed the Thermus thermophilus (Deinococcota) TspmSyn activity. It is notable that we did not identify a TspmSyn in the Bacillota phylum. However, there are some genomes encoding APTs with TspmSyn homology, for example, Dethiobacter alkaliphilus (Bacillota, Dethiobacteria) encodes a TspmSyn homolog (WP_264698086, 304 aa) and a Spd/N1-APAgmSyn homolog (WP_264697253, 276 aa). The APTs from Ca. Pelagibacter species standout because they are Spd/Spm/Tspm synthases fused at the N terminus to a functional AdoMetDC. Both SpmSyns and TspmSyns are found in thermophiles and also mesophiles.

All bacterial Spm and Tspm synthases were able to varying degrees to produce either Spm or Tspm from Put, with the exception of the TspmSyns from P. aeruginosa PAO1 and Thermodesulfovibrio yellowstonii. This would be consistent with the idea that Spm/Tspm synthases evolved from Spd/N1-APAgm synthases and retained SpdSyn function. A potential advantage of encoding distinct Spd/N1-APAgm synthases, and separate Spm/Tspm synthases that can synthesize Spm/Tspm from Put, in the same cell, is that Spm/Tspm biosynthesis could be uncoupled from Spd and even Put biosynthesis.

A universal feature of TspmSyns that we observed is their ability to synthesize Nspm from Nspd, implying that Nspm biosynthesis is an inherent characteristic of TspmSyns. That is to say, TspmSyns are de facto NspmSyns if the substrate Nspd is present and if Spd does not completely outcompete Nspd as substrate. This is of direct relevance in some bacteria, for example, Nspm is a prominent polyamine in Thermodesulfobacterium thermophilum and in Thermus thermophilus (30), each of which encodes a TspmSyn. The NspmSyn activity of a crenarchaeote TspmSyn has also been demonstrated (46), and in the case of Pyrobaculum calidifontis, the Nspd substrate for Nspm biosynthesis is thought to be generated from Tspm by an unknown dehydrogenase. TspmSyns from Arthrospira platensis, Fimbriimonas ginsengisoli, and Thermodesulfobacterium thermophilum, and the Spm/Tspm synthases from Ca. Pelagibacter species were also able to produce Nspd from Dap, revealing that TspmSyns are also potential Nspd and Nspm synthases, if Dap or Nspd are present in the corresponding cells. Although all SpmSyns aminopropylated Hspd, only the SpmSyn from Oceanithermus profundus was able to aminopropylate Nspd, suggesting that most SpmSyns exhibit strict specificity for aminopropylating substrates with N-aminobutyl groups (Put, Spd, and Hspd).

One of our more unexpected findings was that most of the SpdSyns we analyzed were able to aminopropylate Agm. Until our study, only the APTs of Thermus thermophilus and the archaea Thermococcus kodakarensis and Pyrobaculum calidifontis were known to aminopropylate Agm (33, 42, 46). Some of the SpdSyns were able to aminopropylate Agm in the E. coli BL21speG strain that contains a very high level of putrescine and relatively low level of Agm. The overexpressed E. coli SpdSyn was only able to produce N1-APAgm in the BL21speB strain that contains a very high level of Agm and a relatively low level of Put. When expressed in BL21speB grown with L-arginine, the only bacterial SpdSyn that was not able to aminopropylate Agm was the SpdSyn (SpeE) of P. aeruginosa PAO1. It is notable that E. coli and P. aeruginosa PAO1 are the only species we examined that encode two alternative pathways for Put biosynthesis via L-arginine and L-ornithine decarboxylases. Most of the species encoding N1-APAgm synthases possess only L-arginine decarboxylases, although these nonhomologous decarboxylases are derived from four different protein folds. Therefore, irrespective of the evolutionary origin of agmatine production within these species, N1-APAgm biosynthesis, and potentially the formation of Spd via N1-APAgm is likely a common feature of bacterial polyamine biosynthesis. This seems to be the case with even well-studied species such as Bacillus subtilis, which is known to accumulate Spd without any detectable Put accumulation (47). It is also the case that Oceanithermus profundus, Thermosynthropha lipolytica, Geobacillus stearothermophilus, Sulfobacillus acidophilus, and Desulfosporosinus orientis contain little or no detectable Put accumulation (30). N1-APAgm may therefore play a much more widespread role in Spd biosynthesis than previously realized, and the biosynthetic sequence of Spd biosynthesis from L-arginine will need to be reconfigured for many bacteria.

We also note that some APT pairs where the SpdSyn produces N1-APAgm, when coexpressed with their corresponding TspmSyn, are able to aminopropylate N1-APAgm, that is, to produce N12-guanidinothermospermine. It is therefore formally possible that in some species, Tspm could be produced from Agm via N1-APAgm and N12-guanidinothermospermine, in the absence of Put and Spd formation. Whether the same ureohydrolase would act on both N1-APAgm and N12-guanidinothermospermine is not known but the advantage of such a pathway would be that Tspm biosynthesis could be decoupled from both Put and Spd biosynthesis. It is likely that the various N1-APAgm synthases identified in our study were able to produce Spd directly from Put in E. coli BL21speE because the E. coli agmatine ureohydrolase rapidly converts Agm to Put. Thus, Put would be the only substrate available for aminopropylation.

To distinguish between Spm and Tspm synthases at the amino acid sequence level, the most useful motif is hhhhGGGD(G/C)G for SpmSyns and hhhhGGGEGA for TspmSyns, where h represents a small hydrophobic residue. The exceptions are the TspmSyns from Thermodesulfobacterium thermophilum, and Fimbriimonas ginsengisoli, which have a SpmSyn-like motif. This motif is part of the dcAdoMet binding region (8). The motif does not distinguish SpdSyns/N1-APAgmSyns from either Spm or Tspm synthases. A Maximum Likelihood phylogenetic tree confirms the separation of Spm and Tsm synthases into two distinct clades but noticeably each clade contains SpdSyns/N1-APAgmSyns.

The most unexpected bacterial species from which we functionally identified a TspmSyn is the important opportunistic human pathogen P. aeruginosa. Indeed, the role of polyamines in the growth, virulence and biofilm formation of P. aeruginosa PAO1 and PA14 strains have been extensively studied (48, 49, 50, 51). The TspmSyn that we identified corresponds to the PAO1 strain PA4774 gene, also known as speE2, which encodes the protein NP_253462 (349 a.a.). This gene has been previously described as encoding a SpdSyn (52, 53) and a NspdSyn (40). P. aeruginosa is unusual in that it encodes a typical γ-proteobacterial class 1a AdoMetDC (SpeD) and SpdSyn (SpeE, NP_250378, 286 aa), which are not physically linked in the PAO1 genome. It also encodes a smaller class 1b AdoMetDC (SpeD2, PA7443) immediately upstream of the atypical APT, SpeE2 (the TspmSyn).

Biochemical evidence for SpeE2 being a SpdSyn is based on changes to surface-associated Spd levels when the speE2 gene is mutated (53). This evidence is rather marginal as the reduction of Spd level is only 2-fold. The evidence for SpeE2 being a NspdSyn, or at least being required for Nspd biosynthesis is more compelling; mutation of speE2 was found to reduce surface-associated Nspd by 800-fold (40). We have shown that P. aeruginosa SpeE2 (TspmSyn) does not convert Dap to Nspd. Nevertheless, it is formally possible that the TspmSyn might be required for Nspd production. In the lycophyte vascular plant Selaginella lepidophylla, Tspm is oxidized to Nspd by a polyamine oxidase SelPAO5 (41). The P. aeruginosa PAO1 spermidine dehydrogenase SpdH is able to catabolize Spd to Dap and 4-aminobutyraldehyde, and Spm to Spd and 3-aminopropanaldehyde (54, 55). Although Tspm was not tested as a substrate, it seems plausible that Tspm could be catabolized to Nspd and 4-aminobutyraldehyde. Thus, it is possible that the Tspm could be catabolized to Nspd by SpdH, however, we were able to show that the TspmSyn efficiently converts Nspd to Nspm. A futile cycle might then be set up where Spd is converted to Tspm, which is catabolized to Nspd, which is then converted to Nspm, and then catabolized back to Nspd.

Our analysis of the PAO1 Spd dehydrogenase amino acid sequence (NP_252402; 620 aa) by Interproscan shows that the N-terminal region encodes a strong twin arginine translocation pathway sequence. This would suggest that the Spd dehydrogenase SpdH is exported fully folded into the periplasm. A periplasmic location of SpdH would prevent Nspd being convert to Nspm by the TspmSyn, and would facilitate the export of Nspd to the cell surface in response to cationic antibiotics. This hypothetical pathway for Nspd biosynthesis offers an alternative to the characterized Nspd biosynthetic pathway via Dap and carboxyNspd (56). The P. aeruginosa SpeE SpdSyn exhibits 60% amino acid identity to the E. coli SpdSyn, but the SpeE2 TspmSyn exhibits only 36% identity to E. coli SpdSyn, suggesting that the P. aeruginosa SpeD2-SpeE2 Tspm biosynthetic metabolon was acquired from outside the Proteobacteria by horizontal gene transfer.

Experimental procedures

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

All strains used are derived from E. coli BL21 (DE3). Construction of BL21speD (S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase gene deletion), BL21speE (spermidine synthase gene deletion), and BL21speG (spermidine N-acetyltransferase gene deletion) was described previously (39, 57, 58). A new strain BL21speB (BL21 (DE3) ΔspeB::FRT-kan+-FRT; agmatine ureohydrolase gene deletion) was constructed for the current study. The ΔspeB::FRT-kan+-FRT locus derived from strain JW2904 of the KEIO collection was transduced into BL21 (DE3) using phage P1 and selected for using kanamycin resistance. Flux from L-glutamate to L-ornithine was inhibited by growing BL21speB with added L-arginine as indicated. All strains were grown on or in polyamine-free, chemically defined M9 medium (59).

Chemicals

Thermospermine was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. Homospermidine was a kind gift from Patrick Woster, Medical University of South Carolina. All other chemicals were purchased from Sigma Aldrich.

Plasmids, genes, and expression in E. coli BL21 (DE3)

All tested genes were synthesized by GenScript with E. coli-optimized codons and inserted into pETDuet-1 or pACYCDuet-1 (Novogen) with 5′-Nde1 and 3′-Xho1 sites. Genes were expressed from a phage T7 promoter in pETDuet-1 or from pACYCDuet-1 as indicated and selected with ampicillin or chloramphenicol, respectively. GenBank protein accession numbers and protein sizes in amino acids of each APT homolog are listed in Table S1, along with preferred growth mode and percentage amino acid identity of pairs of APTs encoded by the same genome.

Bacterial growth and polyamine extraction

Strains derived from E. coli BL21 were grown in M9 polyamine-free chemically defined medium without or with added polyamines as described previously (3). Polyamine extraction and benzoylation was performed as described previously (3).

Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry

Benzoylated cell extract samples were run on an Agilent 1290 Infinity HPLC system fitted with an Eclipse XDB-C18 column (4.6 × 150 mm, 5 μm particle size), coupled to an Agilent 6130 quadrapole ESI mass spectrometer run in positive mode, employing a scan range of 100 to 1100 m/z. Due to the relatively low resolution of this machine, the mass tolerance window used for the EICs was set to 1.0 Da. For the liquid chromatography stage, a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min at 20 °C was used with a 5 μl injection volume, employing a gradient elution with aqueous acetonitrile containing 0.1% formic acid. The different polarities of the analyzed compounds required gradient adjustment.

LC-MS/MS analysis of tetrabenzoylated Spm and Tspm

High performance liquid chromatography conditions are as follows: reverse phase chromatography was performed using an ACE 3 C18-PFP 150 × 4.6 mm, 3 μm HPLC column (Mac-Mod). Column temperature, sample injection volume, and flow rate was set to 30 °C, 5 μl, and 0.8 ml/min, respectively. HPLC conditions were as follows: solvent A: water with 0.1% formic acid (v/v), Optima LC/MS Grade; solvent B: acetonitrile with 0.1% formic Acid (v/v), Optima LC/MS Grade: 40% B, 0 to 13 min; 5% B, 15 to 18 min; 95% B, 20 to 23 min; 40% B, 24 to 30 min. Total run time 30 min. Data was processed by SCIEX MultiQuant 3.0.3 software (https://sciex.com/products/software/mass-spectrometry-software-solutions) (AB Sciex) with relative quantification based on the peak area of each metabolite. Targeted mass spectrometric analyses were performed on an AB Sciex QTRAP 6500+ mass spectrometer equipped with an ESI ion spray source. The ESI source was used in positive ion mode. Ion source conditions in the positive mode were as follows: ion source gas 1, 70 p.s.i.; ion source gas 2, 65 p.s.i.; curtain gas, 45 p.s.i.; ion spray voltage, 5500 V; and source temperature, 550 °C. Data acquisition was performed in MRM mode. Three diagnostic MRM transitions in the positive mode for tetrabenzoylated spermine (elution at 11.50 min) and thermospermine (10.63 min) were obtained, and three MS ion transitions Q1/Q3, 619.228/497.2; 619.228/162 and 619.228/77 were monitored. The MS transition of Q1/Q3, 619.228/497.2, was used as the quantifier ion while 619.228/162 and 619.228/77 were used as the qualifier ions. The mass spectrometer was coupled to a Shimadzu HPLC (Nexera X2 LC-30AD) and was controlled by Analyst 1.7 software (https://sciex.com/products/software/mass-spectrometry-software-solutions).

LC-HRMS analysis of tetrabenzoylated N1-aminopropylagmatine and pentabenzoylated N12-guanidinothermospermine

For the chromatographic analysis of tetrabenzoylated N1-aminopropylagmatine only (Fig. S10), Kinetex 2.6 μm, C18, 100 A 50 × 2.1 mm column (Phenomenex) was used with a total run time of 7.5 min. To analyze tetrabenzoylated N1-aminopropylagmatine and pentabenzoylated N12-guanidinothermospermine together, an ACE 3 C18-PFP 150 × 4.6 mm HPLC column (Mac-Mod, USA) with total run 30 min was used to obtain a sharper and more symmetrical peak for pentabenzoylated N12-guanidinothermospermine. For HPLC using the ACE 3 C18-PFP 150 × 4.6 mm column, column temperature, sample injection volume, the flow rate was set to 30 °C, 5 μl, and 0.5 ml/min, respectively. HPLC conditions were as follows: solvent A: water with 0.1% formic Acid (v/v), Optima LC/MS Grade. Solvent B: acetonitrile with 0.1% Formic Acid (v/v), Optima LC/MS Grade: 2% B, 0 to 2 min; 90% B, 5 to 16 min; 2% B, 17 to 30 min. Total run time: 30 min. Data was processed by SCIEX OS software version 2.0.1.48692 (AB Sciex) with relative quantification based on the peak area of each metabolite.

Untargeted mass spectrometric analyses were performed on a Sciex TripleTOF 6600 system (AB SCIEX) equipped with an electrospray ionization source used in the positive ionization mode and configured as follows: ion source gas 1, 50 p.s.i; ion source gas 2, 45 p.s.i; curtain gas, 25 p.s.i.; source temperature, 550 °C; and ion spray voltage floating, +5500 V. TOF-MS mode (full scan) and information dependent acquisition mode (product ion scan) were utilized to collect MS and MS/MS data, respectively. For TOF-MS scans, the mass range was from m/z 60 to 1000, and for product ion scans, the mass range was from m/z 30 to 1000. The collision energy was set at 30 V (+) and collision energy spread was ±15 V. Accumulation time was 0.25 s for TOF-MS scans and 0.06 s for product ion scans. The instrument was automatically calibrated using a calibration delivery system injected in APCI positive calibration solution every 5 samples. The mass spectrometer was coupled to a Shimadzu HPLC (Nexera X2 LC-30AD), and system was controlled by Analyst TF 1.8.1 software (https://sciex.com/products/software/mass-spectrometry-software-solutions) (Sciex).

Phylogenetic analysis

Aminopropyltransferase homologs were identified in specific bacterial genomes using BLASTP analysis, employing the SpdSyn amino acid sequences from E. coli and Bacillus subtilis and the A. thaliana Tspm synthase encoded by the acl5 gene (Genbank protein accession numbers listed in Table S1). A general identification of genomes encoding two APT homologs was performed by interrogating all bacterial genomes using TBLASTN. The N-terminal regions of the H. sapiens SpmSyn and the Ca. Pelagibacter species Spd/Spm/Tspm synthases were removed to facilitate alignment. Amino acid sequence alignment was performed with ClustalW for Figure 9 or MUSCLE (60) for phylogenetic tree creation, and Maximum Likelihood phylogenetic tree construction was performed with IQ-TREE (61), using the “Auto” substitution model and 1000 ultrafast bootstraps analysis (62). The Maximum Likelihood phylogenetic tree was visualized with iTOL (63).

Data availability

All data presented are contained within the article.

Supporting information

This article contains supporting information.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interests with the contents of this article.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions

B. L. investigation; B. L., J. L., H. R. B., and S. K. methodology; M. A. P. and A. J. M. formal analysis; A. J. M. writing–review and editing; A. J. M. writing–original draft; A. J. M. supervision; A. J. M. conceptualization.

Funding and additional information

The work in this study was supported by NIH grants R37AI034432 and R01AI034432 (to M. A. P.) and by the Welch Foundation grant I-1257 to M. A. P., and A. J. M. is supported by UT Southwestern Medical Center. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Reviewed by members of the JBC Editorial Board. Edited by Chris Whitfield

Supporting information

References

- 1.Tabor C.W., Tabor H. Polyamines. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1984;53:749–790. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.53.070184.003533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Michael A.J. Polyamines in eukaryotes, bacteria, and archaea. J. Biol. Chem. 2016;291:14896–14903. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R116.734780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li B., Liang J., Baniasadi H.R., Phillips M.A., Michael A.J. Functional polyamine metabolic enzymes and pathways encoded by the virosphere. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2023;120 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2214165120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Korolev S., Ikeguchi Y., Skarina T., Beasley S., Arrowsmith C., Edwards A., et al. The crystal structure of spermidine synthase with a multisubstrate adduct inhibitor. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2002;9:27–31. doi: 10.1038/nsb737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu H., Min J., Ikeguchi Y., Zeng H., Dong A., Loppnau P., et al. Structure and mechanism of spermidine synthases. Biochemistry. 2007;46:8331–8339. doi: 10.1021/bi602498k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu H., Min J., Zeng H., McCloskey D.E., Ikeguchi Y., Loppnau P., et al. Crystal structure of human spermine synthase: implications of substrate binding and catalytic mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:16135–16146. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710323200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohnuma M., Ganbe T., Terui Y., Niitsu M., Sato T., Tanaka N., et al. Crystal structures and enzymatic properties of a triamine/agmatine aminopropyltransferase from Thermus thermophilus. J. Mol. Biol. 2011;408:971–986. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sekula B., Dauter Z. Crystal structure of thermospermine synthase from Medicago truncatula and substrate discriminatory features of plant aminopropyltransferases. Biochem. J. 2018;475:787–802. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20170900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pegg A.E. S-Adenosylmethionine decarboxylase. Essays Biochem. 2009;46:25–45. doi: 10.1042/bse0460003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weiss M.C., Sousa F.L., Mrnjavac N., Neukirchen S., Roettger M., Nelson-Sathi S., et al. The physiology and habitat of the last universal common ancestor. Nat. Microbiol. 2016;1 doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park M.H., Wolff E.C. Hypusine, a polyamine-derived amino acid critical for eukaryotic translation. J. Biol. Chem. 2018;293:18710–18718. doi: 10.1074/jbc.TM118.003341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gutierrez E., Shin B.S., Woolstenhulme C.J., Kim J.R., Saini P., Buskirk A.R., et al. eIF5A promotes translation of polyproline motifs. Mol. Cell. 2013;51:35–45. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jansson B.P., Malandrin L., Johansson H.E. Cell cycle arrest in archaea by the hypusination inhibitor N(1)-guanyl-1,7-diaminoheptane. J. Bacteriol. 2000;182:1158–1161. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.4.1158-1161.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Michael A.J. Polyamine function in archaea and bacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 2018;293:18693–18701. doi: 10.1074/jbc.TM118.005670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Minguet E.G., Vera-Sirera F., Marina A., Carbonell J., Blazquez M.A. Evolutionary diversification in polyamine biosynthesis. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2008;25:2119–2128. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pegg A.E., Michael A.J. Spermine synthase. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2010;67:113–121. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0165-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pegg A.E. The function of spermine. IUBMB Life. 2014;66:8–18. doi: 10.1002/iub.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cason A.L., Ikeguchi Y., Skinner C., Wood T.C., Holden K.R., Lubs H.A., et al. X-linked spermine synthase gene (SMS) defect: the first polyamine deficiency syndrome. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2003;11:937–944. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stewart T.M., Foley J.R., Holbert C.E., Khomutov M., Rastkari N., Tao X., et al. Difluoromethylornithine rebalances aberrant polyamine ratios in Snyder-Robinson syndrome. EMBO Mol. Med. 2023;15 doi: 10.15252/emmm.202317833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamaguchi K., Takahashi Y., Berberich T., Imai A., Miyazaki A., Takahashi T., et al. The polyamine spermine protects against high salt stress in Arabidopsis thaliana. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:6783–6788. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.10.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamaguchi K., Takahashi Y., Berberich T., Imai A., Takahashi T., Michael A.J., et al. A protective role for the polyamine spermine against drought stress in Arabidopsis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007;352:486–490. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamasaki-Katagiri N., Katagiri Y., Tabor C.W., Tabor H. Spermine is not essential for growth of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: identification of the SPE4 gene (spermine synthase) and characterization of a spe4 deletion mutant. Gene. 1998;210:195–201. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00027-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.White W.H., Gunyuzlu P.L., Toyn J.H. Saccharomyces cerevisiae is capable of de Novo pantothenic acid biosynthesis involving a novel pathway of beta-alanine production from spermine. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:10794–10800. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009804200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takano A., Kakehi J., Takahashi T. Thermospermine is not a minor polyamine in the plant kingdom. Plant Cell Physiol. 2012;53:606–616. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcs019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hanzawa Y., Takahashi T., Michael A.J., Burtin D., Long D., Pineiro M., et al. ACAULIS5, an Arabidopsis gene required for stem elongation, encodes a spermine synthase. EMBO J. 2000;19:4248–4256. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.16.4248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knott J.M., Romer P., Sumper M. Putative spermine synthases from Thalassiosira pseudonana and Arabidopsis thaliana synthesize thermospermine rather than spermine. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:3081–3086. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.05.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kakehi J., Kuwashiro Y., Motose H., Igarashi K., Takahashi T. Norspermine substitutes for thermospermine in the control of stem elongation in Arabidopsis thaliana. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:3042–3046. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Furumoto T., Yamaoka S., Kohchi T., Motose H., Takahashi T. Thermospermine is an evolutionarily ancestral phytohormone required for organ development and stress responses in Marchantia polymorpha. Plant Cell Physiol. 2024;65:460–471. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcae002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hamana K., Hamana H., Niitsu M., Samejima K., Matsuzaki S. Distribution of unusual long and branched polyamines in thermophilic eubacteria belonging to "Rhodothermus," Thermus and Thermonema. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 1992;38:575–584. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hosoya R., Hamana K., Niitsu M., Itoh T. Polyamine analysis for chemotaxonomy of thermophilic eubacteria: polyamine distribution profiles within the orders Aquificales, Thermotogales, Thermodesulfobacteriales, Thermales, Thermoanaerobacteriales, Clostridiales and Bacillales. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 2004;50:271–287. doi: 10.2323/jgam.50.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hosoya R., Yokoyama Y., Hamana K., Itoh T. Polyamine analysis within the eubacterial thirteen phyla Acidobacteria, Actinobacteria, Chlorobi, Chloroflexi, Chrysiogenetes, Deferribacteres, Fibrobacteres, Firmicutes, Fusobacteria, Gemmatimonadetes, Nitrospirae, Planctomycetes and Verrucomicrobia. Microbiol. Cult. Coll. 2006;22:21–33. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hamana K., Furuchi T., Hayashi H., Niitsu M. Additional analysis of cyanobacterial polyamines - Distributions of spermidine, homospermidine, spermine, and thermospermine within the phylum Cyanobacteria. Microb. Resour. Syst. 2016;32:179–186. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ohnuma M., Terui Y., Tamakoshi M., Mitome H., Niitsu M., Samejima K., et al. N1-aminopropylagmatine, a new polyamine produced as a key intermediate in polyamine biosynthesis of an extreme thermophile, Thermus thermophilus. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:30073–30082. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413332200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oshima T. Unique polyamines produced by an extreme thermophile, Thermus thermophilus. Amino Acids. 2007;33:367–372. doi: 10.1007/s00726-007-0526-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Korhonen V.P., Halmekyto M., Kauppinen L., Myohanen S., Wahlfors J., Keinanen T., et al. Molecular cloning of a cDNA encoding human spermine synthase. DNA Cell Biol. 1995;14:841–847. doi: 10.1089/dna.1995.14.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hanzawa Y., Imai A., Michael A.J., Komeda Y., Takahashi T. Characterization of the spermidine synthase-related gene family in Arabidopsis thaliana. FEBS Lett. 2002;527:176–180. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03217-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sole-Gil A., Hernandez-Garcia J., Lopez-Gresa M.P., Blazquez M.A., Agusti J. Conservation of thermospermine synthase activity in vascular and non-vascular plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2019;10:663. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.00663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bale S., Ealick S.E. Structural biology of S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase. Amino Acids. 2010;38:451–460. doi: 10.1007/s00726-009-0404-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li B., Maezato Y., Kim S.H., Kurihara S., Liang J., Michael A.J. Polyamine-independent growth and biofilm formation, and functional spermidine/spermine N-acetyltransferases in Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus faecalis. Mol. Microbiol. 2019;111:159–175. doi: 10.1111/mmi.14145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bolard A., Schniederjans M., Haussler S., Triponney P., Valot B., Plesiat P., et al. Production of norspermidine Contributes to Aminoglycoside resistance in pmrAB mutants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019;63:e01044–e01119. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01044-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sagor G.H., Inoue M., Kim D.W., Kojima S., Niitsu M., Berberich T., et al. The polyamine oxidase from lycophyte Selaginella lepidophylla (SelPAO5), unlike that of angiosperms, back-converts thermospermine to norspermidine. FEBS Lett. 2015;589:3071–3078. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2015.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morimoto N., Fukuda W., Nakajima N., Masuda T., Terui Y., Kanai T., et al. Dual biosynthesis pathway for longer-chain polyamines in the hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus kodakarensis. J. Bacteriol. 2010;192:4991–5001. doi: 10.1128/JB.00279-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sekowska A., Bertin P., Danchin A. Characterization of polyamine synthesis pathway in Bacillus subtilis 168. Mol. Microbiol. 1998;29:851–858. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00979.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Michael A.J. Evolution of biosynthetic diversity. Biochem. J. 2017;474:2277–2299. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20160823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]