Abstract

Five structurally and functionally different proteins, an enzyme superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1), a TAR-DNA binding protein-43 (TDP-43), an RNA-binding protein FUS, a cofilin-binding protein C9orf72, and polypeptides generated as a result of its intronic hexanucleotide expansions, and to lesser degree actin-binding profilin-1 (PFN1), are considered to be the major drivers of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. One of the features common to these proteins is the presence of significant levels of intrinsic disorder. The goal of this study is to consider these neurodegeneration-related proteins from the intrinsic disorder perspective. To this end, we employed a broad set of computational tools for intrinsic disorder analysis and conducted intensive literature search to gain information on the structural peculiarities of SOD1, TDP-43, FUS, C9orf72, and PFN1 and their intrinsic disorder predispositions, and the roles of intrinsic disorder in their normal and pathological functions.

Keywords: Neurodegeneration, Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, SOD1, TDP-43, FUS, Intrinsically disordered proteins, Protein–protein interactions, Posttranslational modifications, Binding-induced folding, Polymorphism, Protein structure, Protein function

Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS, also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease) is a malady that causes progressive degeneration of motor neurons, eventually leading to inability to speak, eat, move, and finally breathe. This disease affects motor neurons that provide control of voluntary movements. There are two major types of ALS: sporadic and familial. These types of ALS are clinically undistinguishable, and sporadic ALS is far more common and accounts for 90–95% of all ALS cases [1]. Although familial ALS has a hereditary genetic basis, whereas sporadic ALS is obviously not inheritable, recent research suggests that the story might not be so simple. An expansion of a GGGGCC hexanucleotide that can vary from ten to thousands of repeats in the non-coding region of gene C9orf72 on chromosome 9p21 is seemingly the cause of 30–60% of familial ALS cases [2–5]. Of particular interest, however, is that approximately 8% of sporadic ALS cases also contain this mutation. This suggests that the genetic risk for ALS can be viewed as a continuum in which “the same genetic variants can serve as either mutations with Mendelian segregation or low-penetrance risk alleles, depending on the genetic background” [1]. Five structurally and functionally different proteins, an enzyme superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1), a TAR-DNA binding protein-43 (TDP-43), an RNA-binding protein FUS, a cofilin-binding protein C9orf72 (and proteins generated as a result of its intronic hexanucleotide expansions), and a cytoskeleton regulator profilin1 (PFN1) are considered to be the major drivers of the ALS pathology.

Intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) or intrinsically disordered protein regions (IDPRs) can be defined as functional proteins or protein regions that lack ordered three dimensional structures [6–16]. These proteins have the ability to bind to multiple partners, which enables them to function in regulation, signaling, and control, where they are commonly engaged in one-to-many and many-to-one interactions [6, 8, 12–14, 17–23]. Disordered proteins or protein regions are often affected by post translational modifications, such as phosphorylation, glycosylation, methylation, and ubiquitination [24, 25], and serve as major targets for the alternative splicing [26–28]. All these means are utilized by nature to control and regulate functions of IDPs or hybrid proteins containing ordered domains and functional IDPRs. These structure-less, highly dynamic, promiscuously interacting proteins/regions are implicated in numerous human diseases [29–31]. Specifically, these proteins are major players in many neurodegenerative diseases including Alzheimer’s disease (Aβ, tau, NAC fragment of α-synuclein), Parkinson’s disease (α-synuclein), prion diseases (prion protein), and many others [32, 33]. We show here that although five proteins associated with ALS are characterized by very different levels of intrinsic disorder, this disorder plays an important role in their functional life and is likely to be related to their pathogenic behavior.

Materials and methods

Amino acid sequences of all proteins analyzed in this study (in FASTA format) and some general information related to their structure and function were retrieved from UniProt [34].

Intrinsic disorder propensities of target proteins were evaluated using four algorithms from the PONDR family, PONDR-FIT, PONDR® VLXT, PONDR® VSL2, and PONDR® VL3 [35–40], as well as the IUPred web server [41]. For each protein, after obtaining an average disorder score by each predictor, all predictor-specific average scores were averaged again to generate an average per-protein intrinsic disorder score. Use of consensus for evaluation of intrinsic disorder is motivated by empirical observations that this approach usually increases the predictive performance compared to the use of a single predictor [42–44]. We further characterized the disorder status of query proteins using the MobiDB database (http://mobidb.bio.unipd.it/) [45, 46], that generates consensus disorder scores by aggregating the output from ten predictors, such as two versions of IUPred [41], two versions of ESpritz [47], two versions of DisEMBL [48], JRONN [49], PONDR® VSL2B [39, 40], and GlobPlot [50]. MobiDB also has manually curated annotations related to protein function and structure derived from UniProt [34] and DisProt [51], as well as from Pfam [52] and PDB [53].

We also used binary disorder predictors, which are computational tools that evaluate the overall disorder status of a query protein as its predisposition to be ordered or disordered as a whole. These binary disorder predictors were the charge-hydropathy (CH) plot [8, 54] and the cumulative distribution function (CDF) plot [54, 55], as well as their combination known as the CH-CDF plot [55–57]. In the resulting CH-CDF plot, the coordinates of a query protein are calculated as a distance of the corresponding protein in the CH-plot from the boundary (Y-coordinate) and an average distance of the respective CDF curve from the CDF boundary (X-coordinate). Positive and negative Y values in the CH-CDF plot correspond to proteins predicted within CH-plot analysis to be intrinsically disordered or ordered, respectively. In contrast, positive and negative X values are attributed to proteins predicted within CDF analysis to be ordered or intrinsically disordered, respectively. The resultant CH-CDF space is split into four quadrants that provide specific expectations for proteins they carry. Here, Q1 (upper-right) contains proteins predicted to be disordered by CH-plot but ordered by CDF; Q2 (lower-right) includes ordered proteins; Q3 (lower-left) has proteins predicted to be disordered by CDF but compact by CH-plot (i.e., native molten globules or hybrid proteins containing comparable quantities of order and disorder); whereas Q4 (upper-left) contains proteins predicted to be disordered by both methods (i.e., proteins with extended disorder, such as native coils and native pre-molten globules) [56].

Complementary disorder evaluations together with important disorder-related functional information were retrieved from the D2P2 database (http://d2p2.pro/) [58], which is a database of predicted disorder for a large library of proteins from completely sequenced genomes [58]. D2P2 database uses outputs of IUPred [41], PONDR® VLXT [35], PrDOS [59], PONDR® VSL2B [39, 40], PV2 [58], and ESpritz [47]. The database is further supplemented by data concerning location of various curated posttranslational modifications and predicted disorder-based protein-binding sites.

Additional functional information for these proteins was retrieved using Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes; STRING, http://string-db.org/, which generates a network of predicted associations based on predicted and experimentally validated information on the interaction partners of a protein of interest [60]. In the corresponding network, the nodes correspond to proteins, whereas the edges show predicted or known functional associations. Seven types of evidence are used to build the corresponding network, where they are indicated by the differently colored lines: a green line represents neighborhood evidence; a red line—the presence of fusion evidence; a purple line—experimental evidence; a blue line—co-occurrence evidence; a light blue line—database evidence; a yellow line—text mining evidence; and a black line—co-expression evidence [60]. In our analysis, the most stringent criteria were used for selection of interacting proteins by choosing the highest cut-off of 0.9 as the minimal required confidence level.

Potential disorder-based protein binding sites of query proteins (molecular recognition features, MoRFs) were identified by the ANCHOR algorithm [61, 62]. This algorithm utilizes the pair-wise energy estimation approach originally used by IUPred [41, 63]. This approach acts on the hypothesis that long regions of disorder include localized potential binding sites which are not capable of folding on their own due to not being able to form enough favorable intrachain interactions, but can obtain the energy to stabilize via interaction with a globular protein partner [61, 62].

Interactability of three major ALS-related players and their binding partners was further evaluated by the APID (Agile Protein Interactomes DataServer) platform (http://apid.dep.usal.es) [64]. APID contains information on 90,379 distinct proteins from more than 400 organisms (including Homo sapiens) and on the 678,441 singular protein–protein interactions. For each protein–protein interaction (PPI), the server provides currently reported information about its experimental validation. For each protein, APID unifies PPIs found in five major primary databases of molecular interactions, such as BioGRID [65], Database of Interacting Proteins (DIP) [66], Human Protein Reference Database (HPRD) [67], IntAct [68], and the Molecular Interaction (MINT) database [69], as well as from the BioPlex (biophysical interactions of ORFeome-based complexes) [70] and from the protein databank (PDB) entries of protein complexes [71]. This server provides a simple way to evaluate the interactability of individual proteins in a given dataset and also allows researchers to create a specific protein–protein interaction network in which proteins from the query dataset are engaged.

Results and discussion

SOD1

Superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1, or superoxide dismutase [Cu–Zn]) is an antioxidant enzyme that protects cells from superoxide radicals by catalyzing a reaction that converts superoxide (O2 −) to produce O2 ions and H2O2 using Cu2+ ion as an important constituent of the catalytic site and Zn2+ ion as an important structure stabilizer [72]. Of the genes involved in the ALS pathogenesis, SOD1 is one of the most commonly implicated. Mutations of this gene have been associated with many varieties of familial ALS; as much as 20% of patients with familial ALS contain a mutation of the SOD1 gene. More than 170 mutations of SOD1 are found to cause ALS. At least some of these mutations are believed to cause the enzyme to gain damaging properties [73]. The conformations of SOD1 mutants share a similar property: they all contain an exposed N-terminal short region which is believed to cause stress in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) by acting on the ER protein Derlin-1. In addition, SOD1 mutants have been shown to expose their hydrophobic regions, thereby increasing the propensity of the protein to aggregate [74].

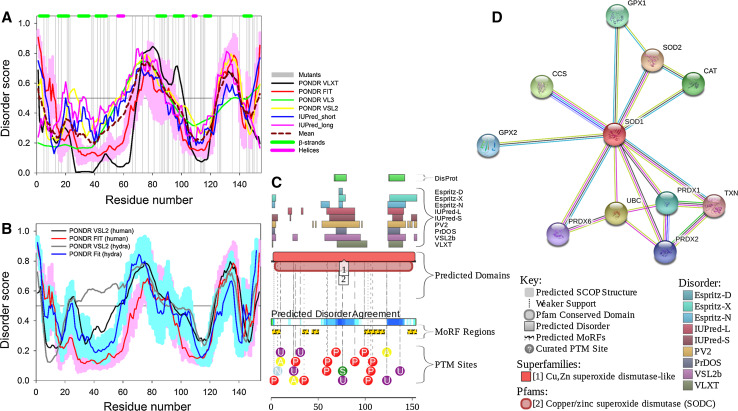

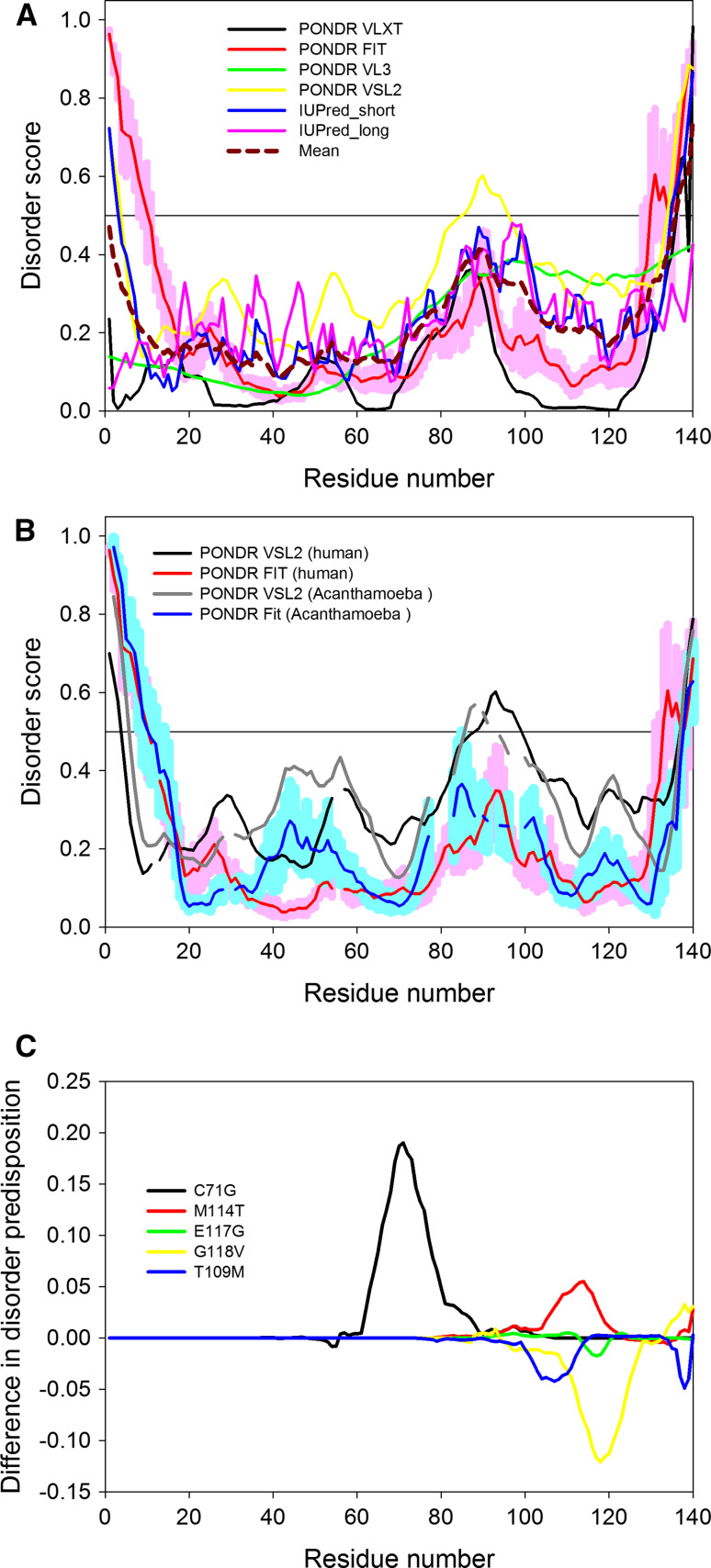

The multiparametric computational analysis conducted in our study revealed that human SOD1 (UniProt ID: P00441) is predicted to possess rather high level of intrinsic disorder (see Fig. 1). In fact, according to the PONDR® VL3, PONDR® VLXT, IUPred_short, IUPred_long, PONDR® FIT, and PONDR® VSL2 analyses, SOD1 is characterized by the contents of the predicted disordered residues (CPDR) of 29.87, 31.77, 32.12, 34.42, 36.36, and 44.81%, respectively. Furthermore, 30.52 and 27.63% of human SOD1 residues are predicted to be disordered (have disorder scores above the 0.5 threshold) based on the averaging the outputs of the PONDR® VLXT, PONDR® VL3, PONDR® VSL2, PONDR® FIT, IUPred_short, and IUPred_long predictors and by the MobiDB platform that aggregates the outputs from ten disorder predictors, respectively (http://mobidb.bio.unipd.it/) [45, 46]. This clearly places SOD1 into the category of moderately or even highly disordered proteins, if the classification of proteins based on their CPDR values is used, where proteins are considered as highly ordered, moderately disordered, or highly disordered if their CPDR < 10%, 10% ≤ CPDR < 30%, or CPDR ≥ 30%, respectively [75].

Fig. 1.

Evaluating functional intrinsic disorder and interactability of human SOD1 protein (UniProt ID: P00441). a Evaluating intrinsic disorder propensity by series of per-residue disorder predictors. Disorder profiles generated by PONDR® VLXT, PONDR® VSL2, PONDR® VL3, PONDR® FIT, IUPred_short and IUPred_long are shown by black, red, yellow, green, blue, and pink lines, respectively. Dark red dashed line shows the mean disorder propensity calculated by averaging disorder profiles of individual predictors. Light pink shadow around the PONDR® FIT shows error distribution. In these analyses, the predicted intrinsic disorder scores above 0.5 are considered to correspond to the disordered residues/regions, whereas regions with the disorder scores between 0.2 and 0.5 are considered flexible. b Analysis of the evolutionary conservation of intrinsic disorder propensity in SOD1 proteins from Homo sapience (UniProt ID: P00441) human and Hydra attenuata (UniProt ID: I3V7W8). c Intrinsic disorder propensity and some important disorder-related functional information generated for human SOD1 by the D2P2 database (http://d2p2.pro/) [58]. Here, the green-and-white bar in the middle of the plot shows the predicted disorder agreement between nine predictors, with green parts corresponding to disordered regions by consensus. Yellow bar shows the location of the predicted disorder-based binding sites (molecular recognition features, MoRFs), whereas colored circles at the bottom of the plot show location of various PTMs. d Analysis of the interactivity of human SOD1 by STRING computational platform that produces the network of predicted associations for a particular group of proteins [60]

Figure 1a shows that the most disorder is found within the short N- and C-terminal tails of SOD1, as well as within the two central regions (residues 65–92 and 125–140) that correspond to the functional loops IV and VII of the protein (see below). Therefore, there is an excellent agreement between the computationally evaluated distribution of the intrinsic disorder predisposition within the sequence of SOD1 and known structural properties of this protein derived in the NMR and crystallographic studies. Figure 1b compares disorder profiles of human SOD1 and its orthologue from Hydra attenuata (UniProt ID: I3V7W8) and clearly shows that major order–disorder features are well-conserved over the evolution, which is evidenced by the overall similarity of disorder profiles and by the rather similar CPDR values evaluated for these two proteins by the MobiDB platform (27.63 and 29.22% for human and hydra proteins, respectively). To further illustrate abundance and functionality of intrinsic disorder in human SOD1, Fig. 1c shows the output of the D2P2 platform (http://d2p2.pro/) [58], which uses outputs of IUPred [41], PONDR® VLXT [35], PrDOS [59], PONDR® VSL2B [39, 40], PV2 [58], and ESpritz [47] and also shows location of various posttranslational modifications and predicted disorder-based protein binding sites in a query protein. Figure 1C shows that according to the ANCHOR algorithm [61, 62], human SOD1 is expected to have five disorder-based binding sites (residues 1–9, 33–39, 43–50, 99–120, and 145–154). This protein also has a multitude of various posttranslational modifications, such as phosphorylation, ubiquitination, SUMOylation, acetylation, and nitrosylation (see Fig. 1c). All these clearly indicate that conserved and abundant disorder serves several important functions for this enzyme. Finally, Fig. 1d represents the STRING-based evaluation of the human SOD1 interactome and shows that this protein has several binding partners. Note that data shown in this plot were obtained using the most stringent confidence level of 0.95. MobiDB lists 409 proteins interacting with human SOD1. These SOD1 partners are characterized by the variable levels of intrinsic disorder that range from 0 to 100%. Overall, 36, 71, and 302 SOD1 partners have CPDR ≥ 30% (are predicted to be highly disordered), 10% ≤ CPDR < 30% (are moderately disordered), and CPDR < 10% (are highly ordered), respectively.

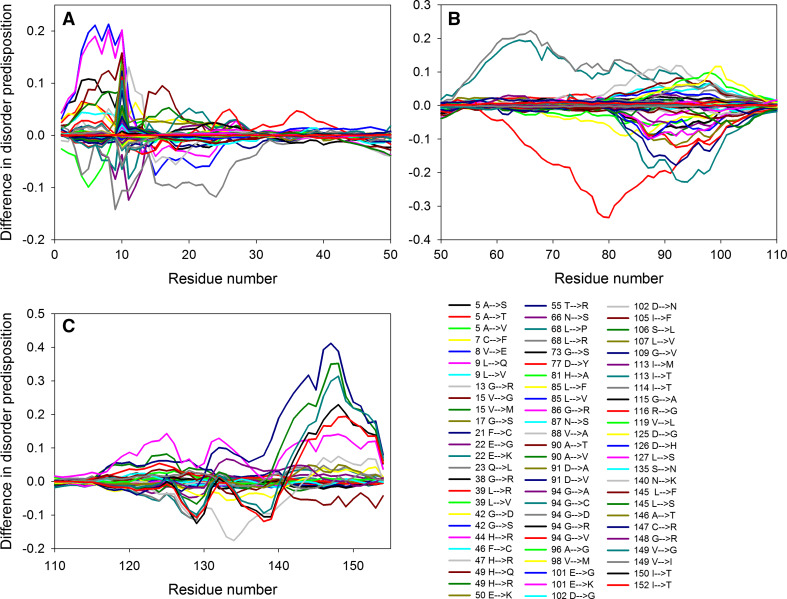

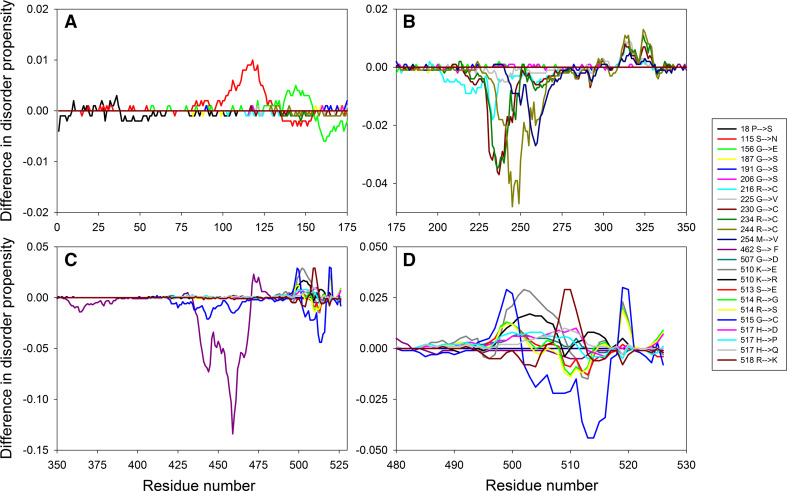

Figure 1a illustrates that ALS-related mutations are almost evenly distributed within the SOD1 sequence, affecting ordered and intrinsically disordered regions almost with similar probability. To illustrate how the mutations affect disorder propensity of human SOD1, Fig. 2 represents “disorder difference spectra” calculated as a simple difference between the disorder curves calculated for mutant and wt-SOD1. Obviously, in this presentation, negative (positive) peaks correspond to mutations leading to the local decrease (increase) in the intrinsic disorder propensity. Since SOD1 contains numerous mutations and to show effects of mutations in more detail, the SOD sequence was split into three parts to show data for N-terminal region (residues 1–50), the central region (residues 50–110) and the C-terminal region (residues 110–154). This figure shows that many point mutations had profound effects on the local disorder propensity of a protein, providing further support to the idea that specific distribution of order and disorder is needed for the appropriate functioning of SOD1. For example, as a result of L144F mutation, the local disorder propensity within the C-terminal tail of SOD1 decreases, extending the existing disorder-based binding site by a couple of residues. As a result, this mutant is able to specifically interact with the RNA-binding protein G3BP1 in an RNA-independent manner and affects stress granule dynamics, whereas wt-SOD1 does not have these functions [76]. Similarly, Dorfin or RNF19A, which is a RING finger-type E3 ubiquitin ligase, specifically interacts with the pathogenic ALS-related variants of SOD1, Gly38Arg, His47Arg, Gly86Arg, and Gly94Ala (all of which causes changes in the local disorder propensity in the vicinity of mutation), whereas there is no interaction between this E3 ubiquitin ligase and wt-SOD1 [77].

Fig. 2.

Effect of ALS-associated mutations on local intrinsic disorder propensity of human SOD1 in a form of the “difference spectra” calculated as a simple difference between the per-residue disorder propensities evaluated by the PONDR® VSL2 for the mutant form of human SOD1 and the per-residue disorder propensity evaluated by the PONDR® VSL2 for the wild-type protein. The protein sequence is split into three parts to zoom into the N-terminal region (residues 1–50, a), the central region (residues 50–110, b) and the C-terminal region (residues 110–154, c)

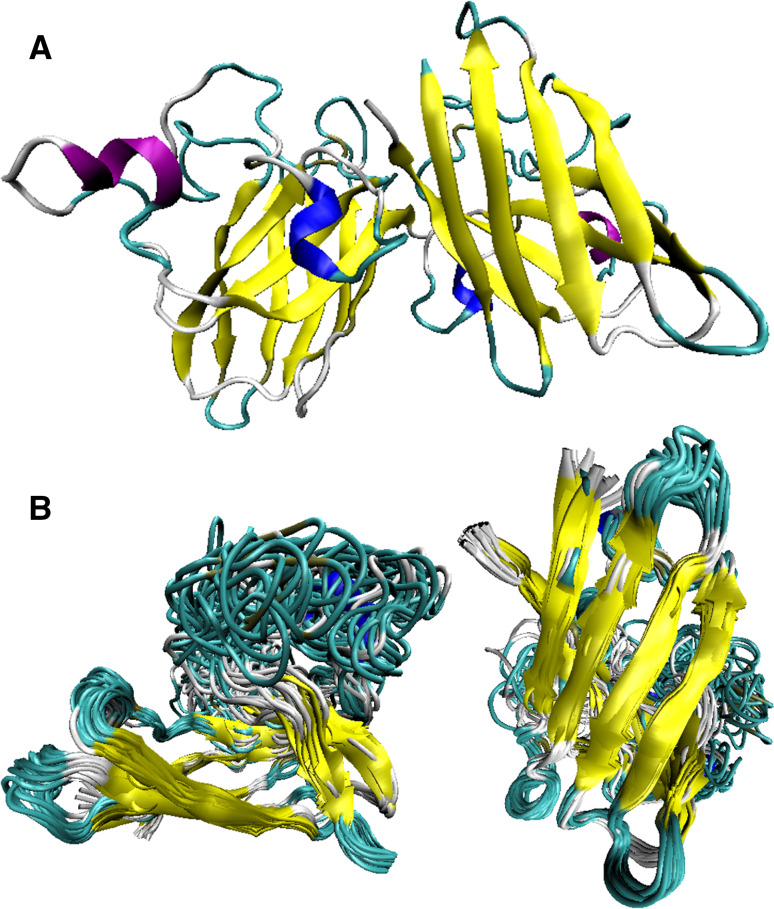

It is interesting to put these observations in line with the known structural characteristics of human SOD1, which exists as a homodimer, whose protomers are held together by hydrophobic interactions [78, 79]. This protein is characterized by a very well-conserved folding topology found in all the intracellular eukaryotic SODs, where each protomer has 153 amino acids arranged in a Greek key β-barrel structure composed of eight antiparallel β-strands [80] (see Fig. 3a). The length of loops connecting β-strands varies, and they are numbered according to the number of the first strand they connect. Loops play important functional roles, with loop IV (residues 49–82) being involved in the Zn2+ coordination and the inter-protomer interactions, and with the electrostatic loop VII (residues 121–143) possessing strategically placed charge residues to generate an electrostatic field needed for guiding the superoxide anion to the copper ion [81–83]. The metal ions are coordinated by ligands located both in β-strands (e.g., His46 and His48 in β4 and His120 in β7 are involved in the Cu+ binding and Asp83 in β5 is involved in the Zn2+ ion coordination), and in the loop IV, where His63, His71, and His80 are responsible for coordination the Zn2+ ion [78, 80].

Fig. 3.

Structural comparison of holo- and apo-forms of human SOD1. a X-ray crystal structure of the metal-saturated dimer of human SOD1 (PDB ID: 2C9V; [85]). b NMR solution structure of the monomeric apo-form of SOD1 (PDB ID: 1RK7; [84]). Here, structure of the protein is shown in two projections (bottom and side views, left and right structure, respectively) to better visualize structural dynamics of the loop region

Analysis of the solution NMR structure of the apo-form of human SOD1 revealed that although removal of metal ions does not significantly affect the overall fold of this protein, which is still characterized by a well-defined tertiary structure, it significantly enhances conformational dynamics and has some local structural effects, mostly affecting loops [84]. For example, the length of the β-strands involved in the coordination of metal ions was shortened, and apo-SOD1 gained more open configuration due to the movement of the β7 and β8 strands away from the reminder of the β-barrel [84]. Furthermore, loops IV (zinc coordination and the inter-protomer interactions) and VII (contribution to the active cavity channel) which contains three zinc ligands (His63, His71, and His80) became severely disordered and highly mobile [84]. Curiously, these two loops correspond to the central regions of SOD1 predicted to be disordered (see Fig. 1a). These observations are further illustrated by Fig. 3 that compares the high resolution (1.07 Å) X-ray crystal structure of the metal-saturated dimer of human SOD1 (PDB ID: 2C9V; [85], Fig. 3a) with the NMR solution structure of its monomeric apoform (PDB ID: 1RK7; [84], Fig. 3b, c) and shows the presence of a dramatic difference in the structural dynamics between the metal-saturated dimer and the metal-free monomer. Therefore, despite being an enzyme, SOD1 (especially its reduced apo-form) is a highly dynamic protein, a conclusion supported by both structural and computational analyses.

TDP-43

Another important player in the ALS pathology is the TAR-DNA binding protein-43 (TDP-43), which is also involved in the pathogenesis of another neurodegenerative disease, frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) with ubiquitin positive inclusions (FTLD-U) with and without motor neuron disease (MND) [86, 87]. In fact, all sporadic ALS and some forms of familial ALS and most sporadic and some familial forms of FTLD-U (which is now known as FTLD-TDP) are characterized by the TDP-43 pathology [88–90].

TDP-43 is an RNA- and DNA-binding protein that is 414 amino acids long with a molecular mass of 44 kDa. It has an N-terminal domain (NTD, residues 1–103), two RNA recognition motifs, RRM1 (residues 104–200) and RRM2 (residues 191–262), a nuclear export signal (NES), a nuclear localization signal (NLS), and a glycine-rich C-terminal domain (residues 274–413), which is known as a prion-like domain. TDP-43 is present in two proteoforms generated by alternative splicing, with isoform #2 being different from the canonical form of the protein by having changed N-terminal tail, where the 1MSEYIRVTEDENDEPIEI18 sequence is substituted to MPQMLAGEIWCMLSTIQK, and by missing the 19–134 region.

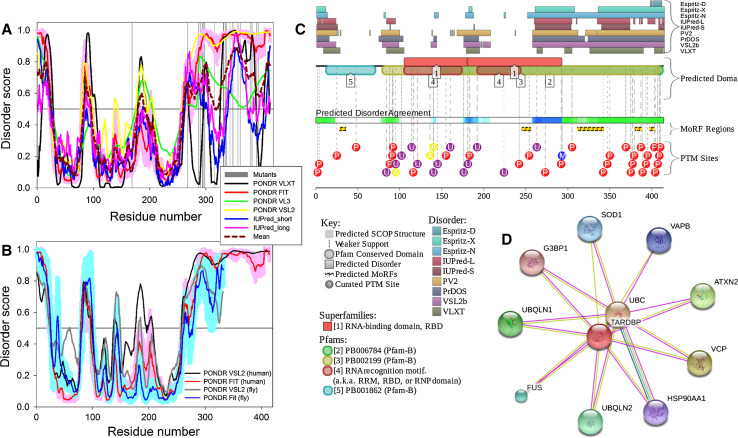

Figure 4a shows that human TDP-43 is predicted to have several long IDPRs (residues 1–25, 84–104, 175–204, 260–414), with the longest one being the prion-like C-terminal domain. Importantly, almost all pathology-related mutations are located within this C-terminal tail, indicating the importance of its sequence integrity. It is known that TARDBP gene is highly conserved in human, mouse, Drosophila melanogaster, and Caenorhabditis elegans [91]. Figure 4b shows the disorder profiles of human SOD1 and its orthologue from Drosophila melanogaster (UniProt ID: Q9W1I0) and illustrates remarkable similarity of these rather complex profiles. Furthermore, the CPDR values evaluated for these two proteins by the MobiDB platform were rather similar too (36.96 and 30.72% for human and fly proteins, respectively).

Fig. 4.

Functional disorder in human TDP-43 protein (UniProt ID: Q13148). a Disorder profiles generated by PONDR® VLXT, PONDR® VSL2, PONDR® VL3, PONDR® FIT, IUPred_short and IUPred_long and a consensus disorder profile. b Evolutionary conservation of intrinsic disorder propensity in TDP-43 proteins from Homo sapience (UniProt ID: Q13148) human and Drosophila melanogaster (UniProt ID: Q9W1I0). c Intrinsic disorder propensity and some important disorder-related functional information generated the D2P2 database. d Interactivity analysis by STRING. All other keys are described in legend to Fig. 1

Figure 4c provides the D2P2 output for human TDP-43 and shows that intrinsic disorder has several functional implications for this protein, being important for its interactivity and numerous posttranslational modifications. In fact, there are five MoRFs in TDP-43, with four of them being concentrated within the long disordered C-tail [residues 28–35 (MoRF1); 245–255 (MoRF2); 311–342 (MoRF3); 380–387 (MoRF4); and 397–402 (MoRF5)], and this protein is extensively decorated with phosphorylation, ubiquitination acetylation, and methylation. It was pointed out that the phosphorylated TDP-43 became resistant to the calpain cleavage suggesting that phosphorylation (and likely some other posttranslational modifications) may play a regulatory role in the TDP-43 pathology of ALS/FTLD [92]. It is also known that the pathological phosphorylation of TDP-43 is controlled by the phosphatase calcineurin that can bind to and catalyze the removal of pathological C-terminal phosphorylation of TDP-43 [93].

Several pathological mutations are located within the predicted MoRF regions (e.g., A315T, Q331K, S332N, G335D, and M337V are within the MoRF3) and, therefore, are likely to contribute to the changed interactability of this protein. Figure 4D shows the interactome of human TDP-43 evaluated by STRING platform using the most stringent confidence level of 0.95. According to the MobiDB analysis, TDP-43 interacts with 110 proteins, half of which is predicted to be highly or moderately disordered (there are 26, 27, and 57 partners of TDP-43 that are characterized by CPDR ≥ 30%, 10% ≤ CPDR < 30%, and CPDR < 10%, respectively.

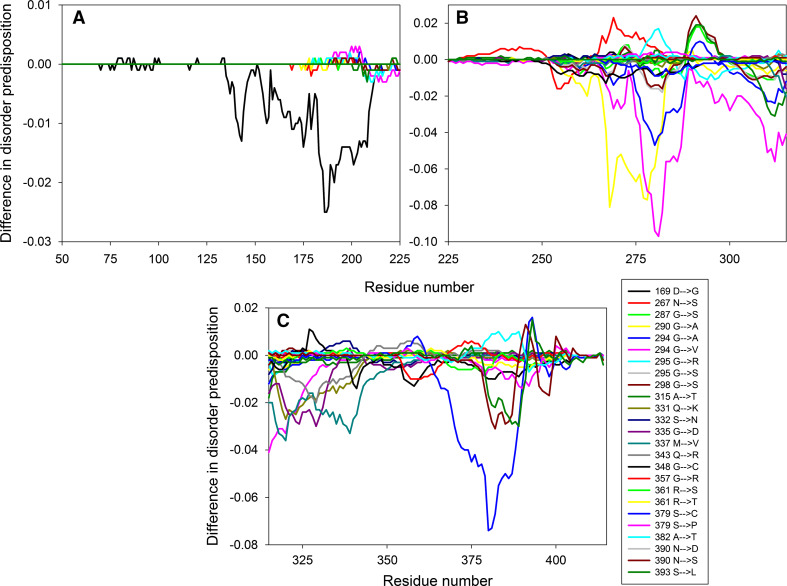

Figure 5 summarizes the effect of pathological mutations on the local intrinsic disorder propensity of human TDP-43 in a form of “disorder difference spectra” introduced in the SOD1 section and shows that the major “response” of this protein to mutations in its highly disordered C-terminal tail is a decrease in intrinsic disorder propensity (there are far more negative than positive peaks in the graph). This mutation-induced “order enhancement” might constitute a molecular basis for the increased interactability of mutated TDP-43 proteoforms. This is because many disorder-based binding regions are characterized by the presence of less disordered sub-regions, which are not capable of folding on their own, but can undergo binding-induced folding at interaction with its binding protein partner. In disorder profiles, such regions are typically manifested as local “dips” within the regions with high disorder score [94, 95].

Fig. 5.

Difference disorder spectra calculated based on the effect of pathological mutations on intrinsic disorder propensity of human TDP-43. The protein sequence is split into three parts to zoom into the N-terminal region (residues 50–225, a), the central region (residues 225–315, b), and the C-terminal region (residues 315–414, c)

High levels of predicted intrinsic disorder in this protein provide a reasonable explanation for the inability to obtain structure for the full-length TDP-43. In fact, despite the obvious importance of TDP-43 for the pathology of several neurodegenerative diseases, there is no structure of the full-length protein. It was pointed out that one of the potential reasons for the lack of success in crystallization of this protein is its instability, since the recombinant full-length TDP-43 is known to be degraded within hours of its expression [96]. This instability is mostly due to the highly flexible C-terminal domain and in part due to the N-terminal domain, since in the experiments on the thermal stability analysis of different fragments derived from TDP-43 it was shown that the most thermally stable was the RRM1 domain, whereas the NTD and the truncated C-terminal tail reduced its stability [96].

Structural information is currently available for several fragments of TDP-43, and corresponding NMR structures for the N-terminal domain (residues 1–77; PDB ID: 2N4P; [97]) and the RRM1-RRM2 domain (residues 102–269; PDB ID: 4BS2; [98]) in aqueous solutions, as well as for the prion-like hydrophobic helix (residues 307–349) in DPC (PDB ID: 2N2C; [99]) are shown in Fig. 6. Therefore, ~30% of the TDP-43 sequences do not have structural coverage. One should keep in mind though that the structure of the prion-like domain fragment was obtained for its dodecylphosphocholine (DPC) micelle-bound form, suggesting that this region is likely to be disordered in the aqueous media. This further increases the structurally uncharacterized part of human TDP-43 to 41%.

Fig. 6.

Structural characterization of different TDP-43 domains. a Solution NMR structure of the N-terminal domain (residues 1–77; PDB ID: 2N4P; [97]). b NMR solution structure of the RRM1-RRM2 domain (residues 102–269) in a complex with the UG-rich RNA, where the RNA molecule was computationally removed (PDB ID: 4BS2; [98]). c Solution NMR structure of the TDP-43 prion-like hydrophobic helix in DPC (residues 307–349; PDB ID: 2N2C; [99])

RNA-binding protein FUS

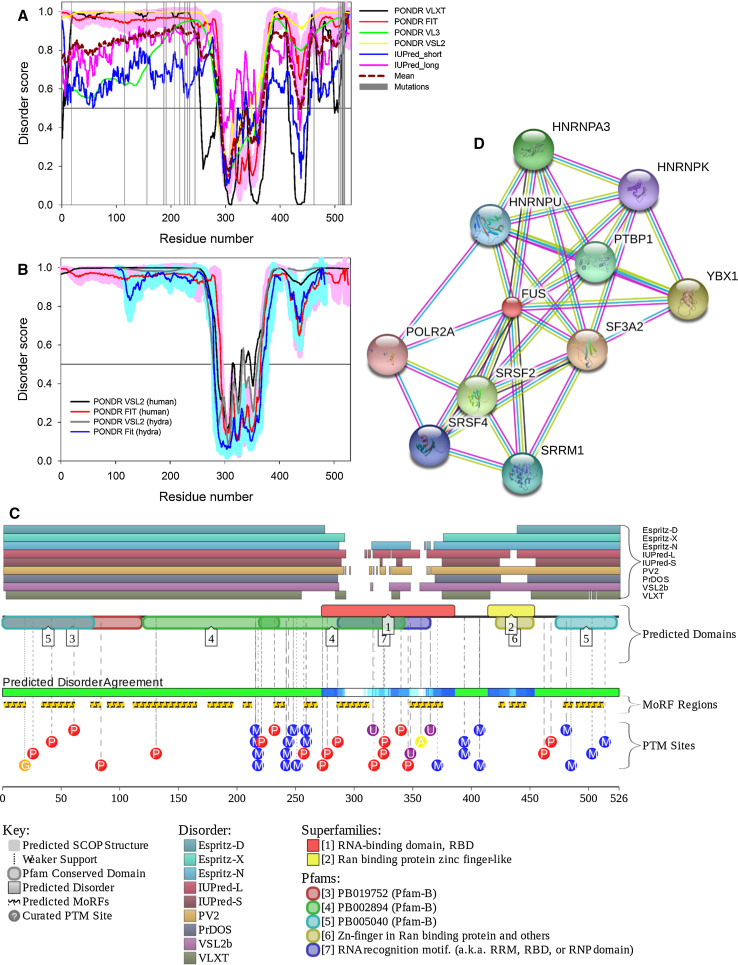

In addition to SOD1 and TARDBP genes discussed in the previous sections, missense mutations in FUS/TLS (fused in sarcoma/translocation in liposarcoma or FUS) are also associated with familial ALS (FALS), accounting for ~5% of FALS cases [100]. FUS is a 526 amino acid-long protein that is a member of the FET/TET family of the DNA/RNA-binding proteins that also includes EWS (Ewing’s sarcoma) and TAF15 (TATA-box binding protein associated factor 15) [101]. FUS consists of an N-terminal domain that is Gln/Gly/Ser/Tyr-rich domain (residues 1–165), a Gly- rich domain (166–267), an RNA recognition motif (RRM, residues 285–379), and an Arg/Gly-rich domain (residues 371–526) that contains a zinc-finger motif (residues 422–453) [102].

Figure 7a shows that FUS is predicted to be highly disordered. In fact, the only region expected to be ordered corresponds to the RRM domain located within the central part of FUS protein (residues 290–370). Figure 7b shows that the peculiarities of disorder distribution in FUS proteins are well conserved within the animal kingdom, since shapes of disorder profiles of human and hydra proteins are rather similar. FUS from Hydra attenuata (UniProt ID: T2MGK7) is characterized by the MobiDB consensus score of 75.27%, whereas for human protein (UniProt ID: P35637), the MobiDB consensus score is 86.14%. Figure 7c shows that human FUS is predicted to have 15 MoRFs ranging in length from 6 to 55 residues [residues 1–19 (MoRF1); 33–61 (MoRF2); 75–83 (MoRF3); 89–103 (MoRF4); 111–165 (MoRF5); 175–196 (MoRF6); 205–212 (MoRF7); 231–240 (MoRF8); 257–268 (MoRF9); 285–312 (MoRF10); 347–375 (MoRF11); 423–428 (MoRF12); 432–446 (MoRF13); 478–486 (MoRF14); and 489–512 (MoRF15)]. Therefore, disorder-based binding regions cover >55% of the protein length, indicating that FUS is expected to utilize disorder-based binding mode for interaction with its numerous partners (see Fig. 7d). In fact, according to the MobiDB analysis, human FUS interacts with 494 proteins, half of which is predicted to be highly or moderately disordered (there are 136, 110, and 248 partners of FUS that are characterized by CPDR ≥ 30%, 10% ≤ CPDR < 30% and CPDR < 10%, respectively.

Fig. 7.

Functional disorder in human FUS protein (UniProt ID: P35637). a Disorder profiles generated by PONDR® VLXT, PONDR® VSL2, PONDR® VL3, PONDR® FIT, IUPred_short and IUPred_long and a consensus disorder profile. b Evolutionary conservation of intrinsic disorder propensity in FUS proteins from Homo sapience (UniProt ID: P35637) and Hydra attenuata (UniProt ID: T2MGK7). c Intrinsic disorder propensity and some important disorder-related functional information generated the D2P2 database. d Interactivity analysis by STRING. All other keys are described in legend to Fig. 2

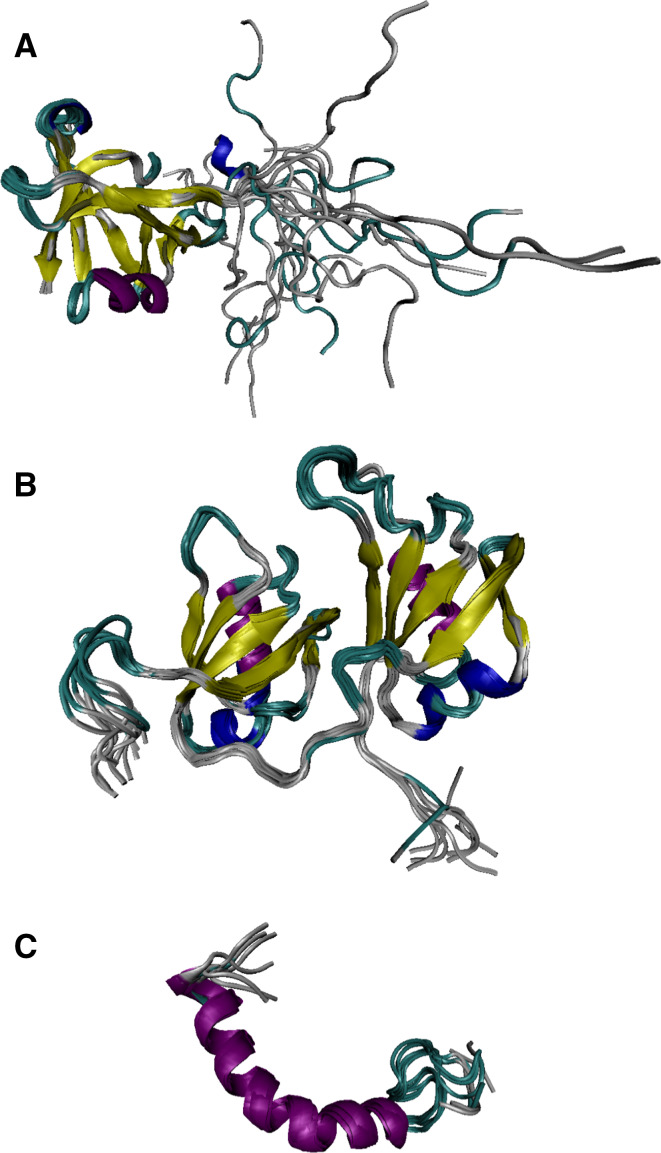

In agreement with these predictions, Fig. 8 shows that structural information on FUS protein is limited to the NMR structure of its RRM domain (residues 278–385; PDB ID: 2LCW) and the X-ray crystal structure of its nuclear localization signal (NLS) peptide (residues 495–526) bound to the human transportin (PDB ID: 4FQ3). This gives the least structural coverage of 26.4% for the FUS sequence among the three proteins considered in this study.

Fig. 8.

Structural characterization of human FUS protein. a Solution NMR structure of the RRM domain (residues 278–385; PDB ID: 2LCW). b X-ray crystal structure of the FUS fragment (residues 495–526, red ribbon) in a complex with human transportin (blue semitransparent surface), where the RNA molecule was computationally removed (PDB ID: 4FQ3)

Curiously, all disease causing mutations are located outside the ordered region of FUS (see Fig. 7a). Effects of the pathological mutations on intrinsic disorder propensity of human FUS protein were analyzed in the form of “disorder difference spectra” (see Fig. 9). Similar to human TDP-43, the majority of mutations caused decrease in the local disorder score since difference spectra contain more negative than positive peaks. As it was emphasized in the TDP-43 section, local decrease in disorder propensity within the highly disordered region (or mutation-induced “order enhancement”) might generate new disorder-based binding sites, thereby affecting interactability of protein. Furthermore, since many mutations are located at sites of known posttranslational modifications (or at least in close proximity to these sites) one can assume that they might further affect regulation and control of the FUS interactability.

Fig. 9.

Difference disorder spectra calculated based on the effect of pathological mutations on intrinsic disorder propensity of human FUS protein. The protein sequence is split into three parts, the N-terminal region (residues 1–175, a), the central region (residues 175–350, b) and the C-terminal region (residues 350–526, c), whereas plot d further zooms into the last 46 residues of the protein

Protein C9orf72 and dipeptide repeat proteins poly(GA), poly(GR), poly(GP), poly(PA), and poly(PR)

As it was already indicated, genetic alterations in the chromosome 9 open reading frame 72 gene (C9ORF72) are the major cause of both FTLD and ALS. Contrary to all the cases considered so far, where the FTLD and/or ALS-related pathogenicity is associated with the point mutations within the coding regions of the implemented genes (FUS, TDP43, SOD1, and PFN1, see below), the pathological involvement of C9orf72 in these neurodegenerative diseases is based on the GGGGCC hexanucleotide repeat expansion in the non-coding region of the C9ORF72 gene located in an intronic region of this gene between the non-coding exons 1a and 1b. This expansion, which can vary from 10 to thousands of repeats, is the cause of 30–60% of familial ALS cases, is also found in 8% of sporadic ALS cases and in FTLD [2–5], and is considered now as the most common cause of familial and sporadic TDP-43-positive FTLD and ALS (C9-FTLD/ALS) [103, 104]. Although the GGGGCC hexanucleotide repeat expansion is located within the non-coding region of the C9ORF72 gene, it has been established that these expanded repeats can be bi-directionally transcribed, and both sense and antisense repeat RNAs are engaged in the formation of RNA foci in the CNS of ALS and FTLD patients [105–108]. Besides hexanucleotide repeat, RNA foci afflicted patients are present with proteinaceous inclusions throughout the CNS [109]. These inclusions are composed of the dipeptide repeat proteins (DPRs or C9RANT proteins) generated from the GGGGCC repeat RNA via repeat-associated non-ATG (RAN) translation. When sense repeat RNAs are used in the RAN translation, three different proteins, poly(GA), poly(GR), and poly(GP), are synthesized [110, 111], whereas RAN translation of the antisense repeat RNAs generates poly(PA), poly(PR), and poly(GP) proteins [106, 108, 112].

C9orf72 protein was recently shown to be involved in the formation of a complex with cofilin and other actin-binding proteins and regulate axonal actin dynamics, serving as a modulator of small GTPases [113]. Human C9orf72 (UniProt ID: Q96LT7) is present as two proteoforms generated by alternative splicing, where a canonical form (or long isoform #1) represents a 481 residue-long protein and the isoform #2 (or short isoform with 222 residues) is different from the canonical form by missing the C-terminal half of a sequence (residues 223–481) and the N → K substitution at the residue 222. Although reduced expression of both the canonical and short C9orf72 isoforms was reported in the repeat-positive patients [114–116], based on the analysis of the data generated by several studies it was pointed out that the loss-of-function mechanism is unlikely to be the primary cause of the C9-FTLD/ALS [117].

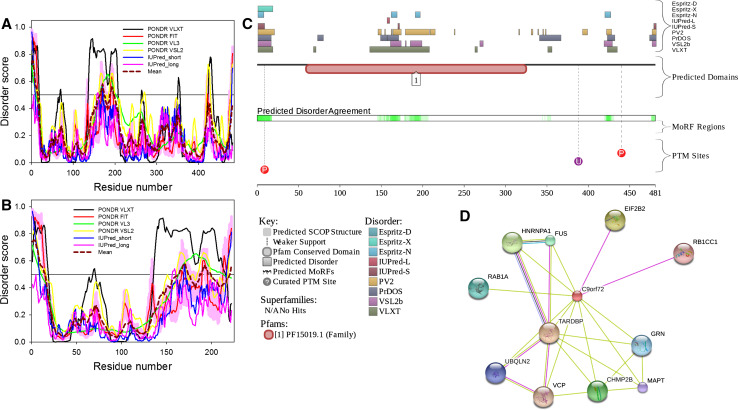

No structural information is currently available for C9orf72, but Fig. 10a, c show that although this protein is predicted to be mostly ordered, it is expected have short disordered tails, three to four short disordered loops, and a long disordered/flexible region located between the residues 130 and 210. Curiously, this region is located in the close proximity to the C-terminal end of the C9orf72 short (residue 1–222), and, therefore, it constitutes the C-terminal mostly disordered tail of this short isoform (see Fig. 10b). Although no disorder-based binding motifs are predicted in the canonical isoform, the C9orf72 short is expected to have one C-terminally located MoRF (residues 215–222). Finally, Fig. 10c shows that C9orf72 has two phosphorylation sites (residues S9 and T440) and one ubiquitination site (residue K388). Figure 10d shows that the C9orf72 is a rather promiscuous binder.

Fig. 10.

Functional disorder in human C9orf72 protein (UniProt ID: Q96LT7). a Disorder profiles generated for the canonical (or long) isoform of a protein by PONDR® VLXT, PONDR® VSL2, PONDR® VL3, PONDR® FIT, IUPred_short and IUPred_long and a consensus disorder profile. b Disorder profiles generated for the short isoform of a protein by PONDR® VLXT, PONDR® VSL2, PONDR® VL3, PONDR® FIT, IUPred_short and IUPred_long and a consensus disorder profile. c Intrinsic disorder propensity and some important disorder-related functional information generated the D2P2 database. d Interactivity analysis by STRING. All other keys are described in legend to Fig. 2

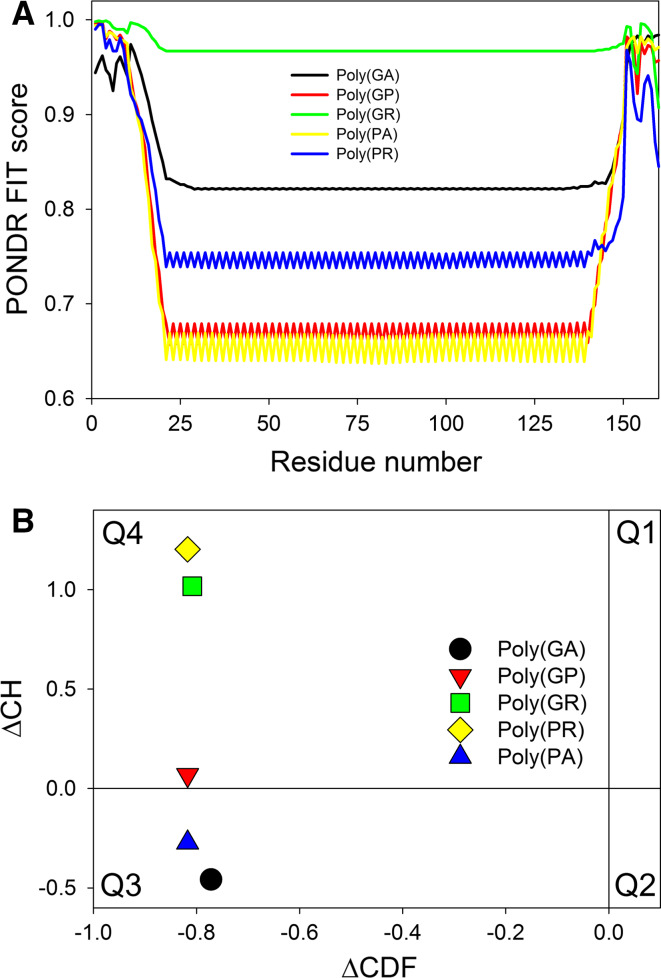

It is known that repeat-containing proteins are often intrinsically disordered, with the more perfect repeats being the less structured [118]. Therefore, it was expected that the poly(GA), poly(GR), poly(GP), poly(PA), and poly(PR) DPRs synthesized as a result of the RAN translation of the sense and antisense repeat RNAs derived from the intronic region of C9ORF72 should be mostly disordered. In agreement with this hypothesis, Fig. 11a represents the PONDR® FIT profiles of these five DPRs, each containing 80 corresponding repeats, and shows that all of these C9RANT proteins are predicted to be highly disordered. One should keep in mind that according to other computation tools used in this study (PONDR® VLXT, PONDR® VL3, PONDR® VSL2, IUPred_short, and IUPred_long) these proteins were predicted to be even more disordered, often showing protein-average disorder score of 1.0.

Fig. 11.

Analysis of the intrinsic disorder predisposition of the poly(GA), poly(GR), poly(GP), poly(PA), and poly(PR) DPRs synthesized as a result of the RAN translation of the sense and antisense repeat RNAs transcribed from the GGGGCC hexanucleotide repeat expansion located within the non-coding region of the C9ORF72 gene. a PONDR® FIT profiles of these five DPRs, each containing 80 corresponding repeats. b CH-CDF analysis of these five C9RANT proteins, all of which are predicted to be disordered at the whole molecule level

Since these five DPRs are highly disordered and are expected to be either highly charged [Poly(GR) and poly(PR)] or uncharged [Poly(GA), Poly(GP), and Poly(PA)], we next analyzed their positions within the CH-CDF phase space. This approach utilizes methodological difference between two binary disorder predictors, CH-plot and CDF analysis. The CH-plot is a linear disorder predictor that uses charge and hydropathy as the only two parameters for classifying query proteins as proteins with substantial amounts of extended disorder (native coils and native pre-molten globules) or proteins with globular conformations (native molten globules and ordered proteins) [54, 119]. On the other hand, CDF analysis uses the PONDR outputs to discriminate all types of disorder (native coils, native molten globules and native pre-molten globules) from ordered proteins [54]. Therefore, the use of the combined CH-CDF plot provides a comprehensive assessment of intrinsic disorder allowing predictive classification of proteins into structurally different classes [56, 57]. Figure 11b represents the CH-CDF plot for five C9RANT proteins and clearly indicates that, being highly disordered, DPRs can be classified either as native molten globules [Poly(GA) and Poly(PA)] or native coils or pre-molten globules [Poly(GP), Poly(GR), and Poly(PR)]. Obviously, these predicted differences in conformational behavior of the DRPs require experimental validation.

Profilin-1

Human profilin-1 (PFN1), is another protein, mutations in which (C71G, T109M, M114T, E117G, and G118V) are associated with a familial form of ALS [120]. However, the PFN1 gene mutations represent a relatively rare cause of familial ALS among patients with predominantly European ancestry [121]. Although the number of ALS cases associated with the PFN1 mutations is much lower than the numbers of cases linked to FUS, TDP43, SOD1, and C9orf72, this protein still deserves consideration, since it is known to misfold and precipitate in some familiar forms of ALS [120].

Human PFN1 (UniProt ID: P07737) is a 140 amino acid protein that serves as a major growth regulator of filamentous (F)-actin via binding to the monomeric (G)-actin [122, 123]. This ubiquitous eukaryotic protein is also known to interact with the phospholipid phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate, suggesting that it serves as a link between the phosphatidyl inositol cycle and actin polymerization, thereby serving as an essential component of the cytoskeletal rearrangement signaling pathway [124, 125]. PFN1 can also interact with poly-l-proline [126, 127]. This protein is rather well conserved over evolution, with human PFN1 and Acanthamoeba profilin I sharing 22% sequence identity and ~45% sequence similarity [125]. Curiously, PFN1 can be related to the pathogenesis of the polyglutamine expansion diseases, since phosphorylation of this protein by ROCK1 kinase was shown to regulate aggregation of the polyglutamine-expanded huntingtin (Htt) and androgen receptor (AR) [128].

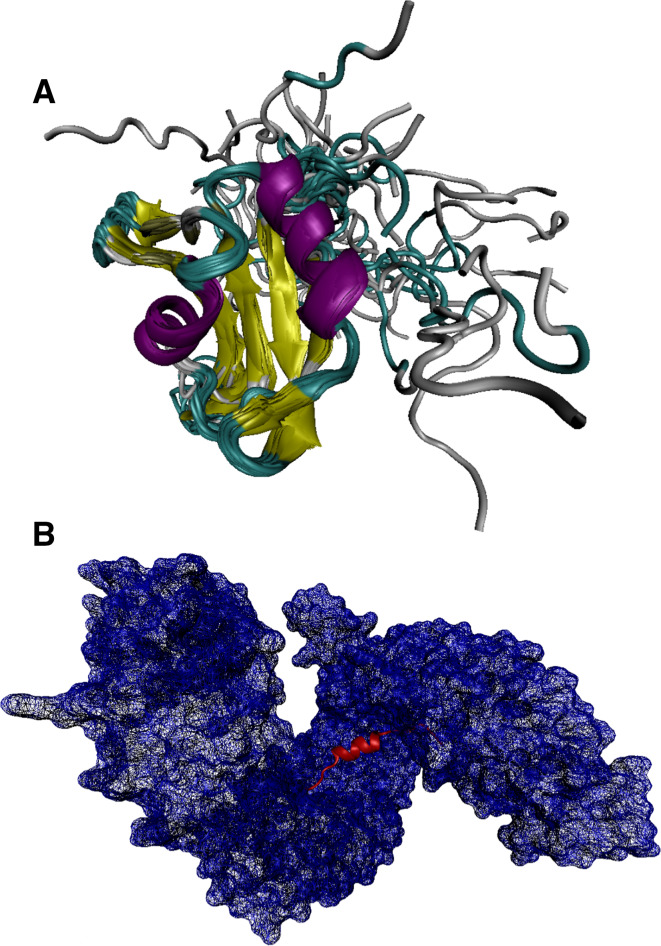

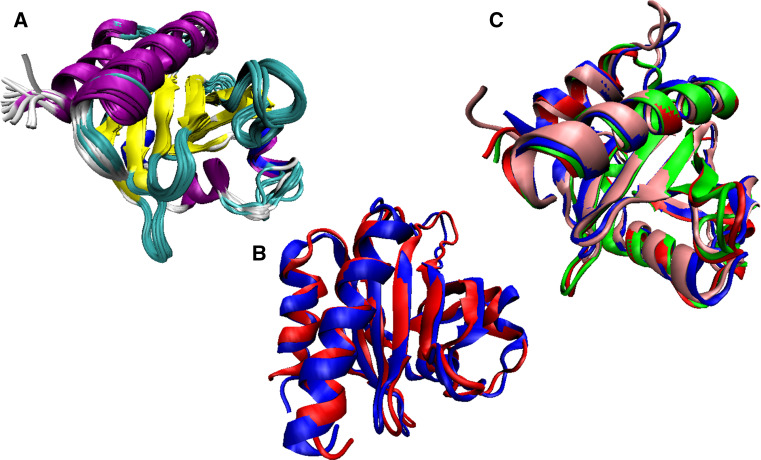

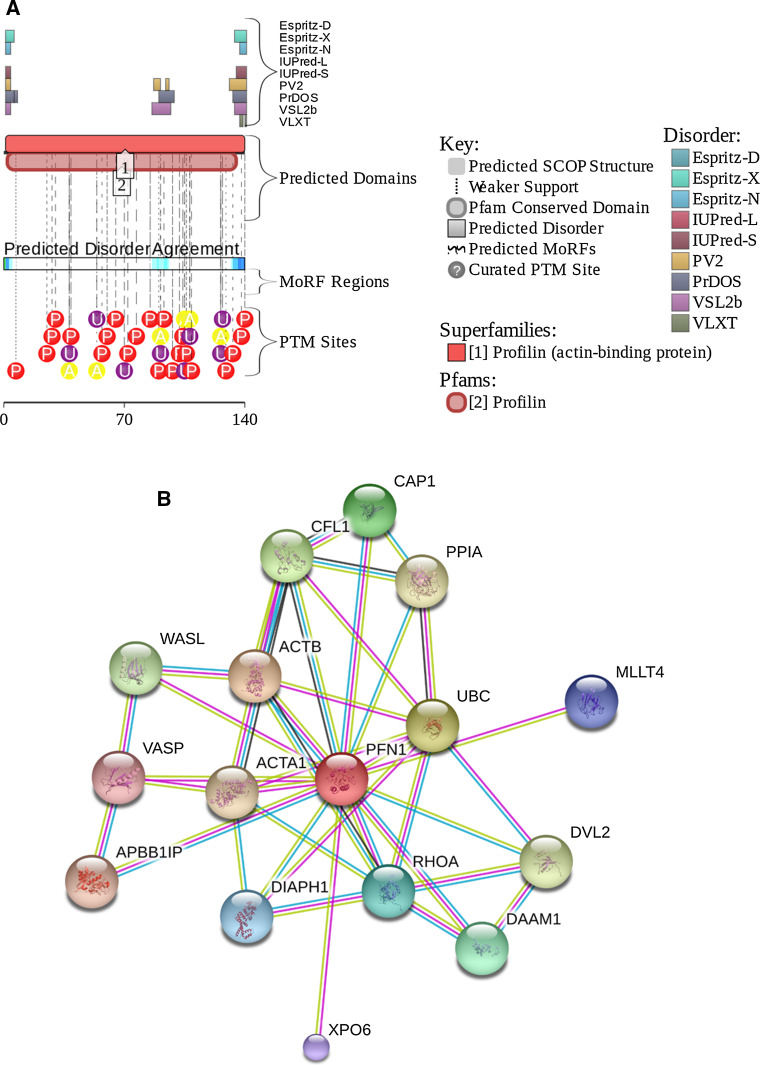

Solution structure was solved for human PFN1 using multidimensional heteronuclear NMR spectroscopy (PDB ID: 1PFL) [125], and high resolution X-ray crystallographic structure of this protein (e.g., PDB ID: 1FIK) is also known. Figure 12a represents 15 structures that comprise the solution structural ensemble of human PFN1 and shows that this protein is characterized by the presence of a well-defined globular structure containing an extended antiparallel β-sheet consisting of seven β-strands (residues 17–24, 29–34, 63–65, 68–76, 84–91, 97–105, and 108–115). On its convex face, this β-sheet is covered by two α-helices comprising the N- and C-terminal residues (residues 3–12 and 122–137, respectively), whereas the opposite, concave, face of the β-sheet is covered by the three short helical regions (residues 38–41, 44–51, and 58–61) [125]. Figure 12b represents alignment of NMR and X-ray structures of this protein conducted using the MultProt (http://bioinfo3d.cs.tau.ac.il/MultiProt/) [129] and shows their very close similarity. In fact, the aligned structures are characterized by the root mean square deviation (RMSD) of 1.17 Å over 136 residues, with highest deviations being observed in the loops and three short helical regions located at the concave face of the β-sheet.

Fig. 12.

Structural characterization of the PFN1 protein. a Solution NMR structure, where 15 structural models are shown that comprise the structural ensemble (PDB ID: 1PFL) [125]. b Structural alignment of NMR (PDB ID: 1PFL, red ribbon) and X-ray structures (PDB ID: 1FIK, blue ribbon) of this protein conducted using the MultProt (http://bioinfo3d.cs.tau.ac.il/MultiProt/) [129]. c Multiple structural alignment of profilin from different organisms (Arabidopsis thaliana (PDB ID: 1A0K; blue ribbon) [130], Homo sapiens (PDB ID: 1FIK; red ribbon), Bos taurus (PDB ID: 1PNE; green ribbon) [131], and Artemisia vulgaris (PDB ID: 5EM0) [132]; pink ribbon)

It was pointed out that structure of PNF1 is evolutionary conserved, with human and bovine proteins being characterized by similar global folding patterns [125]. Figure 12c supports this conclusion by showing aligned 3D structures of profilin from different organisms (Arabidopsis thaliana (PDB ID: 1A0K) [130], Homo sapiens (PDB ID: 1FIK), Bos taurus (PDB ID: 1PNE) [131], and Artemisia vulgaris (PDB ID: 5EM0) [132]). This structural alignment of four proteins of different origin is characterized by the RMSD of 1.17 Å over 110 residues and clearly shows that profilin generally preserved major features of its structure in a long evolutionary run from plants to mammals and to human. Curiously, visual inspection of structures shown in Fig. 12 indicates high overall similarity between the conformational ensembles representing the solution structure of human PFN1 (Figure 12A) and aligned structures of profilin from different organisms.

In agreement with the presence of the well-conserved globular structure in profilin proteins, Fig. 13a shows that human PFN1 is predicted to be the most ordered protein analyzed in this study, being characterized by the mean CPDR of 3.6%. Figure 13a shows that human protein is expected to possess short disordered tails and a flexible region in the vicinity of residues 78–103 characterized by the mean disorder score of 0.327 ± 0.009, which is noticeable higher than the sequence-based mean disorder score of this protein (0.229 ± 0.009). This region with predicted high flexibility includes a loop between the β-strands 4 and 5, β-strands 5 and 6, and a loop between them. In agreement with these predictions, analysis of the dynamics of solution NMR structure of human PFN1 suggested that 79–81 and 91–97 regions are characterized by high conformational variability and enhanced mobility on either the nanosecond-picosecond (residues 91–97) or the microsecond–millisecond (residues 79–81) time scales [125].

Fig. 13.

Evaluation of intrinsic disorder in human PFN1 protein (UniProt ID: P07737). a Disorder profiles generated for the canonical (or long) isoform of a protein by PONDR® VLXT, PONDR® VSL2, PONDR® VL3, PONDR® FIT, IUPred_short and IUPred_long and a consensus disorder profile. b Evolutionary conservation of intrinsic disorder propensity in PFN1 from Homo sapience (UniProt ID: P07737) and profilin-1A from Acanthamoeba castellanii (UniProt ID: P68696). c Difference disorder spectra calculated a difference between the per-residue disorder propensities evaluated by the PONDR® VSL2 for the mutant forms of human PFN1 and the per-residue disorder propensity evaluated by the PONDR® VSL2 for the wild-type protein

Figure 13b illustrates that in agreement with the aforementioned high evolutionary conservation [125], the shapes of disorder profiles of human PFN1 (UniProt ID: P07737) and profilin-1A from Acanthamoeba castellanii (UniProt ID: P68696) are rather similar, suggesting functional importance of the peculiarities of disorder/flexibility distribution within sequences of these proteins. Figure 13c represents “disorder difference spectra” calculated by subtracting per-residue disorder propensities of the PFN1 mutants from those of the wild-type protein and illustrates that the ALS-associated mutations differently affect disorder predisposition of this protein. Here, the C71G and M114T mutations cause noticeable increase in the local disorder propensity, whereas the T109M, E117G, and G118V mutations are associated with the local decrease in the intrinsic disorder propensity.

Figure 14a represents the D2P2 profile of human PFN1 and shows that although this protein does not have disorder-base binding sites and it is not too disordered, it contains a very significant amount of various PTMs that can affect interactability and/or conformational stability of PFN1. In agreement with this hypothesis, PFN1 phosphorylation at Y129 was shown to promote binding of this protein to the tumor suppressor protein von Hippel–Lindau (VHL), preventing the VHL-mediated degradation of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α [133]. Protein kinase A (PKA)-mediated phosphorylation of PFN1 at T89 was shown to enhance PFN1-actin interaction and affect structure and stability of PFN1 [133]. Furthermore, the T109M mutation was shown to abrogate a phosphorylation site and thereby affect functionality of this protein [134]. Figure 14b represents the interactome of human PFN1 evaluated by STRING platform and shows that this mostly ordered protein is involved in a broad spectrum of protein–protein interactions.

Fig. 14.

Functional disorder in human PFN1 protein (UniProt ID: P07737). a Intrinsic disorder propensity and some important disorder-related functional information generated the D2P2 database. b Interactivity analysis by STRING. All other keys are described in legend to Fig. 2

Concluding remarks

Genes such as SOD1, TDP-43, FUS, PFN1, and C9ORF72 are now associated with ALS and are theorized to cause ALS through induction of the abnormalities in RNA processing and/or metabolism. However, FUS and TDP-43 might have pathological mechanism different from those found in more established SOD1-based ALS pathologies. In fact, inclusions that contain TDP-43 and FUS were identified in all ALS patients that were SOD1 mutation-negative, but in none of the SOD1-positive ALS patients [135]. This suggests that while FUS and TDP-43 might be implicated in ALS pathogenesis, the mechanism of their involvement is likely to be independent of SOD1. However, another study showed that mutant/wild-type TDP-43 and mutant FUS can cause misfolding of the wild-type SOD1 in neurons [136], suggesting that a common mechanism involving all of these proteins may cause ALS pathogenesis. Furthermore, a link was recently found between the PFN1 mutations related to familial ALS and intracellular aggregation of TDP-43, where the C-terminal region of TDP-43 which is essential for TDP-43 aggregation was shown to be indispensable for the PFN1-TDP-43 interaction [137, 138].

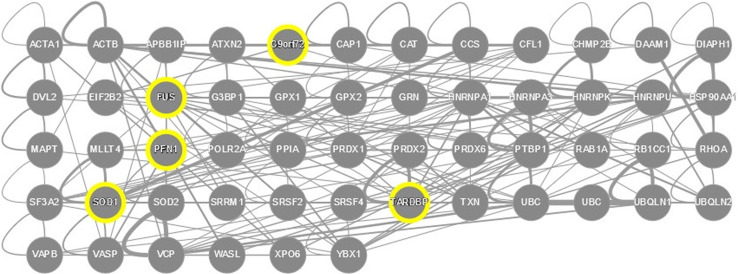

To further illustrate complexity of SOD1-TDP43-FUS-PFN1-C9orf72 system, we analyzed cross-interactivity of these proteins and their binding partners by the APID web server (http://apid.dep.usal.es) [64]. This analysis revealed that SOD1, TDP-43, and FUS can interact with themselves. This is in agreement with their known ability to form homodimers. Furthermore, FUS and TDP-43 have been shown to interact with each other. Next, we used the ability of the APID web server (http://apid.dep.usal.es) to build a protein-protein interaction network between the proteins included in a query list [64]. Figure 15 represents the results of application of this tool to SOD1, TDP-43, FUS, PFN1, C9orf72, and their STRING partners predicted with the confidence of 0.9–0.95 and shows that all these proteins are involved in the formation of a common interactive cluster. The resulting interactome clearly shows that almost all these proteins are talking to each other. Since all five ALS-related proteins analyzed in this study are promiscuous binders and four of them contain significant amount of intrinsic disorder, SOD1, TDP-43, FUS, and C9orf72 can be considered as disordered hub proteins, whereas PFN1 serves as an example of ALS-related ordered hub. It is known that intrinsic disorder is important for binding promiscuity and hubs can be either entirely disordered, or contain both ordered and disordered regions [139]. Although some hubs are ordered, their binding partners contain disordered binding regions. Therefore, there are two primary mechanisms by which disorder is utilized in protein–protein interaction networks, namely one disordered region binding to many partners and many disordered region binding to one partner [139–145]. The astonishing capability of ALS-related proteins with different levels of intrinsic disorder (SOD1, TDP-43, FUS, PFN1, and C9orf72) to be heavily connected hubs and to form a complex intertwined PPI network might represent a major challenge for the development of drugs targeting these proteins.

Fig. 15.

Evaluation of the inter-set interactivity of SOD1, TDP-43, FUS, PFN1, C9orf72, and their interacting proteins from the STRING (the confidence level of 0.9 or 0.95) using the APID web server (http://apid.dep.usal.es) which builds a PPI network between proteins included in a query list

Another important feature of SOD1 [76], TDP-43, and FUS [146], PFN1 [147] is their involvement in the formation of the cytoplasmic RNA granules known as the stress granules (SGs). Similarly, C9orf72 was shown to localize to processing bodies (P-bodies) and to be recruited to SGs upon stress-related stimuli [148], with the long (canonical) isoform of C9orf72 protein being responsible for the regulation of the SG assembly [148]. Also, RAN derived highly charged DPRs (poly(GR) and poly(PR)) were reported to form unique ubiquitin/p62-negative cytoplasmic inclusions, which co-localized with the components of RNA granules [149].

SGs are spheroid or ellipsoid structures that are usually 1–2 μm, but can range from 0.4 to 5 μm [150]. They are formed in response to a variety of stresses that inhibit translation initiation, such as glucose starvation, heat shock, hypoxia, infection by certain viruses, inhibition of mitochondrial function, oxidative stress, and proteotoxic stress [151]. Among various functions ascribed to SGs is their ability to serve as regulatory hubs for mRNA sorting, stress signaling, and apoptosis [146]. Since SGs are found in neurons of ALS and FTLD patients (as well as in some other neurodegenerative diseases) it is likely that the formation or disassembly of these membrane-less organelles may be important for neurological pathogenesis [146]. For example, expression of the C9orf72 protein was shown to be impaired by the hexanucleotide expansion, which also caused an abnormal accumulation of RNA foci, and led to the spontaneous formation of SGs [148].

The normal functionality of TDP-43, FUS, C9orf72, and PFN1, as well as the normal dynamics of SGs (which are, by their nature, reversible entities that undergo constant exchange with their environment) can be affected by the ALS-linked mutations of PFN1 [147], C9orf72 [148], TDP-43 and FUS [152], or the disbalance in their cellular levels [146], or by their mislocalization from nucleus to cytoplasm [153], suggesting that the deregulation of the ability of TDP-43, FUS, C9orf72, and PFN1 to form SGs represent another molecular mechanism of their pathogenic behavior.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by a grant from the ALS Association to V.N.U. (Grant Number IIP-265).

References

- 1.Talbot K. Familial versus sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis—a false dichotomy? Brain. 2011;134(Pt 12):3429–3431. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeJesus-Hernandez M, Mackenzie IR, Boeve BF, Boxer AL, Baker M, Rutherford NJ, Nicholson AM, Finch NA, Flynn H, Adamson J, Kouri N, Wojtas A, Sengdy P, Hsiung GY, Karydas A, Seeley WW, Josephs KA, Coppola G, Geschwind DH, Wszolek ZK, Feldman H, Knopman DS, Petersen RC, Miller BL, Dickson DW, Boylan KB, Graff-Radford NR, Rademakers R. Expanded GGGGCC hexanucleotide repeat in noncoding region of C9ORF72 causes chromosome 9p-linked FTD and ALS. Neuron. 2011;72(2):245–256. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Renton AE, Majounie E, Waite A, Simon-Sanchez J, Rollinson S, Gibbs JR, Schymick JC, Laaksovirta H, van Swieten JC, Myllykangas L, Kalimo H, Paetau A, Abramzon Y, Remes AM, Kaganovich A, Scholz SW, Duckworth J, Ding J, Harmer DW, Hernandez DG, Johnson JO, Mok K, Ryten M, Trabzuni D, Guerreiro RJ, Orrell RW, Neal J, Murray A, Pearson J, Jansen IE, Sondervan D, Seelaar H, Blake D, Young K, Halliwell N, Callister JB, Toulson G, Richardson A, Gerhard A, Snowden J, Mann D, Neary D, Nalls MA, Peuralinna T, Jansson L, Isoviita VM, Kaivorinne AL, Holtta-Vuori M, Ikonen E, Sulkava R, Benatar M, Wuu J, Chio A, Restagno G, Borghero G, Sabatelli M, Consortium I, Heckerman D, Rogaeva E, Zinman L, Rothstein JD, Sendtner M, Drepper C, Eichler EE, Alkan C, Abdullaev Z, Pack SD, Dutra A, Pak E, Hardy J, Singleton A, Williams NM, Heutink P, Pickering-Brown S, Morris HR, Tienari PJ, Traynor BJ (2011) A hexanucleotide repeat expansion in C9ORF72 is the cause of chromosome 9p21-linked ALS-FTD. Neuron 72 (2):257–268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Daoud H, Suhail H, Sabbagh M, Belzil V, Szuto A, Dionne-Laporte A, Khoris J, Camu W, Salachas F, Meininger V, Mathieu J, Strong M, Dion PA, Rouleau GA. C9orf72 hexanucleotide repeat expansions as the causative mutation for chromosome 9p21-linked amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia. Arch Neurol. 2012;69(9):1159–1163. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2012.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garcia-Redondo A, Dols-Icardo O, Rojas-Garcia R, Esteban-Perez J, Cordero-Vazquez P, Munoz-Blanco JL, Catalina I, Gonzalez-Munoz M, Varona L, Sarasola E, Povedano M, Sevilla T, Guerrero A, Pardo J, Lopez de Munain A, Marquez-Infante C, de Rivera FJ, Pastor P, Jerico I, de Arcaya AA, Mora JS, Clarimon J, Group COSS, Gonzalo-Martinez JF, Juarez-Rufian A, Atencia G, Jimenez-Bautista R, Moran Y, Mascias J, Hernandez-Barral M, Kapetanovic S, Garcia-Barcina M, Alcala C, Vela A, Ramirez-Ramos C, Galan L, Perez-Tur J, Quintans B, Sobrido MJ, Fernandez-Torron R, Poza JJ, Gorostidi A, Paradas C, Villoslada P, Larrode P, Capablo JL, Pascual-Calvet J, Goni M, Morgado Y, Guitart M, Moreno-Laguna S, Rueda A, Martin-Estefania C, Cemillan C, Blesa R, Lleo A (2013) Analysis of the C9orf72 gene in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in Spain and different populations worldwide. Hum Mutat 34 (1):79–82 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Dunker AK, Lawson JD, Brown CJ, Williams RM, Romero P, Oh JS, Oldfield CJ, Campen AM, Ratliff CM, Hipps KW, Ausio J, Nissen MS, Reeves R, Kang C, Kissinger CR, Bailey RW, Griswold MD, Chiu W, Garner EC, Obradovic Z. Intrinsically disordered protein. J Mol Graph Model. 2001;19(1):26–59. doi: 10.1016/S1093-3263(00)00138-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wright PE, Dyson HJ. Intrinsically unstructured proteins: re-assessing the protein structure-function paradigm. J Mol Biol. 1999;293(2):321–331. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uversky VN, Gillespie JR, Fink AL. Why are “natively unfolded” proteins unstructured under physiologic conditions? Proteins. 2000;41(3):415–427. doi: 10.1002/1097-0134(20001115)41:3<415::AID-PROT130>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tompa P. Intrinsically unstructured proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 2002;27(10):527–533. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(02)02169-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uversky VN, Dunker AK. Understanding protein non-folding. Biochim Biophys Acta 1804. 2010;6:1231–1264. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tompa P. Intrinsically disordered proteins: a 10-year recap. Trends Biochem Sci. 2012;37(12):509–516. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uversky VN. A decade and a half of protein intrinsic disorder: biology still waits for physics. Protein Sci. 2013;22(6):693–724. doi: 10.1002/pro.2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van der Lee R, Buljan M, Lang B, Weatheritt RJ, Daughdrill GW, Dunker AK, Fuxreiter M, Gough J, Gsponer J, Jones DT, Kim PM, Kriwacki RW, Oldfield CJ, Pappu RV, Tompa P, Uversky VN, Wright PE, Babu MM. Classification of intrinsically disordered regions and proteins. Chem Rev. 2014;114(13):6589–6631. doi: 10.1021/cr400525m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Habchi J, Tompa P, Longhi S, Uversky VN. Introducing protein intrinsic disorder. Chem Rev. 2014;114(13):6561–6588. doi: 10.1021/cr400514h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oldfield CJ, Dunker AK. Intrinsically disordered proteins and intrinsically disordered protein regions. Annu Rev Biochem. 2014;83:553–584. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-072711-164947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uversky VN. Dancing protein clouds: the strange biology and chaotic physics of intrinsically disordered proteins. J Biol Chem. 2016;291(13):6681–6688. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R115.685859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dunker AK, Brown CJ, Lawson JD, Iakoucheva LM, Obradovic Z. Intrinsic disorder and protein function. Biochemistry. 2002;41(21):6573–6582. doi: 10.1021/bi012159+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dunker AK, Brown CJ, Obradovic Z. Identification and functions of usefully disordered proteins. Adv Protein Chem. 2002;62:25–49. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3233(02)62004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uversky VN. Natively unfolded proteins: a point where biology waits for physics. Protein Sci. 2002;11(4):739–756. doi: 10.1110/ps.4210102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Uversky VN. What does it mean to be natively unfolded? Eur J Biochem. 2002;269(1):2–12. doi: 10.1046/j.0014-2956.2001.02649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uversky VN. Protein folding revisited. A polypeptide chain at the folding-misfolding-nonfolding cross-roads: which way to go? Cell Mol Life Sci. 2003;60(9):1852–1871. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3096-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uversky VN. Unusual biophysics of intrinsically disordered proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1834(5):932–951. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Uversky VN. Functional roles of transiently and intrinsically disordered regions within proteins. FEBS J. 2015;282(7):1182–1189. doi: 10.1111/febs.13202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iakoucheva LM, Radivojac P, Brown CJ, O’Connor TR, Sikes JG, Obradovic Z, Dunker AK. The importance of intrinsic disorder for protein phosphorylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(3):1037–1049. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pejaver V, Hsu WL, Xin F, Dunker AK, Uversky VN, Radivojac P. The structural and functional signatures of proteins that undergo multiple events of post-translational modification. Protein Sci. 2014;23(8):1077–1093. doi: 10.1002/pro.2494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Romero PR, Zaidi S, Fang YY, Uversky VN, Radivojac P, Oldfield CJ, Cortese MS, Sickmeier M, LeGall T, Obradovic Z, Dunker AK. Alternative splicing in concert with protein intrinsic disorder enables increased functional diversity in multicellular organisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(22):8390–8395. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507916103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buljan M, Chalancon G, Dunker AK, Bateman A, Balaji S, Fuxreiter M, Babu MM. Alternative splicing of intrinsically disordered regions and rewiring of protein interactions. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2013;23(3):443–450. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buljan M, Chalancon G, Eustermann S, Wagner GP, Fuxreiter M, Bateman A, Babu MM. Tissue-specific splicing of disordered segments that embed binding motifs rewires protein interaction networks. Mol Cell. 2012;46(6):871–883. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Uversky VN, Oldfield CJ, Dunker AK. Intrinsically disordered proteins in human diseases: introducing the D2 concept. Annu Rev Biophys. 2008;37:215–246. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Uversky VN, Dave V, Iakoucheva LM, Malaney P, Metallo SJ, Pathak RR, Joerger AC. Pathological unfoldomics of uncontrolled chaos: intrinsically disordered proteins and human diseases. Chem Rev. 2014;114(13):6844–6879. doi: 10.1021/cr400713r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uversky VN. Wrecked regulation of intrinsically disordered proteins in diseases: pathogenicity of deregulated regulators. Front Mol Biosci. 2014;1:6. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2014.00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uversky VN. Intrinsically disordered proteins and their (disordered) proteomes in neurodegenerative disorders. Front Aging Neurosci. 2015;7:18. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2015.00018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Uversky VN. Targeting intrinsically disordered proteins in neurodegenerative and protein dysfunction diseases: another illustration of the D(2) concept. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2010;7(4):543–564. doi: 10.1586/epr.10.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Apweiler R, Bairoch A, Wu CH, Barker WC, Boeckmann B, Ferro S, Gasteiger E, Huang H, Lopez R, Magrane M, Martin MJ, Natale DA, O’Donovan C, Redaschi N, Yeh LS. UniProt: the Universal Protein knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(Database issue):D115–D119. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Romero P, Obradovic Z, Li X, Garner EC, Brown CJ, Dunker AK. Sequence complexity of disordered protein. Proteins. 2001;42(1):38–48. doi: 10.1002/1097-0134(20010101)42:1<38::AID-PROT50>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li X, Romero P, Rani M, Dunker AK, Obradovic Z (1999) Predicting Protein Disorder for N-, C-, and Internal Regions. In: Genome informatics workshop on genome informatics, vol 10, pp 30–40 [PubMed]

- 37.Xue B, Dunbrack RL, Williams RW, Dunker AK. Uversky VN (2010) PONDR-FIT: a meta-predictor of intrinsically disordered amino acids. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1804;4:996–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peng K, Vucetic S, Radivojac P, Brown CJ, Dunker AK, Obradovic Z. Optimizing long intrinsic disorder predictors with protein evolutionary information. J Bioinform Comput Biol. 2005;3(1):35–60. doi: 10.1142/S0219720005000886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Obradovic Z, Peng K, Vucetic S, Radivojac P, Dunker AK. Exploiting heterogeneous sequence properties improves prediction of protein disorder. Proteins. 2005;61(Suppl 7):176–182. doi: 10.1002/prot.20735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peng K, Radivojac P, Vucetic S, Dunker AK, Obradovic Z. Length-dependent prediction of protein intrinsic disorder. BMC Bioinform. 2006;7:208. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dosztanyi Z, Csizmok V, Tompa P, Simon I. IUPred: web server for the prediction of intrinsically unstructured regions of proteins based on estimated energy content. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(16):3433–3434. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Walsh I, Giollo M, Di Domenico T, Ferrari C, Zimmermann O, Tosatto SC. Comprehensive large-scale assessment of intrinsic protein disorder. Bioinformatics. 2015;31(2):201–208. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fan X, Kurgan L. Accurate prediction of disorder in protein chains with a comprehensive and empirically designed consensus. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2014;32(3):448–464. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2013.775969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peng Z, Kurgan L (2012) On the complementarity of the consensus-based disorder prediction. In: Pacific symposium on biocomputing, pp 176–187 [PubMed]

- 45.Di Domenico T, Walsh I, Martin AJ, Tosatto SC. MobiDB: a comprehensive database of intrinsic protein disorder annotations. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(15):2080–2081. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Potenza E, Domenico TD, Walsh I, Tosatto SC. MobiDB 2.0: an improved database of intrinsically disordered and mobile proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(Database issue):D315–D320. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Walsh I, Martin AJ, Di Domenico T, Tosatto SC. ESpritz: accurate and fast prediction of protein disorder. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(4):503–509. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Linding R, Jensen LJ, Diella F, Bork P, Gibson TJ, Russell RB. Protein disorder prediction: implications for structural proteomics. Structure. 2003;11(11):1453–1459. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang ZR, Thomson R, McNeil P, Esnouf RM. RONN: the bio-basis function neural network technique applied to the detection of natively disordered regions in proteins. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(16):3369–3376. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Linding R, Russell RB, Neduva V, Gibson TJ. GlobPlot: exploring protein sequences for globularity and disorder. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(13):3701–3708. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sickmeier M, Hamilton JA, LeGall T, Vacic V, Cortese MS, Tantos A, Szabo B, Tompa P, Chen J, Uversky VN, Obradovic Z, Dunker AK. DisProt: the database of disordered proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(Database issue):D786–D793. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Finn RD, Bateman A, Clements J, Coggill P, Eberhardt RY, Eddy SR, Heger A, Hetherington K, Holm L, Mistry J, Sonnhammer EL, Tate J, Punta M. Pfam: the protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(Database issue):D222–D230. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Berman HM, Westbrook J, Feng Z, Gilliland G, Bhat TN, Weissig H, Shindyalov IN, Bourne PE. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28(1):235–242. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Oldfield CJ, Cheng Y, Cortese MS, Brown CJ, Uversky VN, Dunker AK. Comparing and combining predictors of mostly disordered proteins. Biochemistry. 2005;44(6):1989–2000. doi: 10.1021/bi047993o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xue B, Oldfield CJ, Dunker AK, Uversky VN. CDF it all: consensus prediction of intrinsically disordered proteins based on various cumulative distribution functions. FEBS Lett. 2009;583(9):1469–1474. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.03.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mohan A, Sullivan WJ, Jr, Radivojac P, Dunker AK, Uversky VN. Intrinsic disorder in pathogenic and non-pathogenic microbes: discovering and analyzing the unfoldomes of early-branching eukaryotes. Mol BioSyst. 2008;4(4):328–340. doi: 10.1039/b719168e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huang F, Oldfield CJ, Meng J, Hsu W-L, Xue B, Uversky VN, Romero P, Dunker AK (2012) Subclassifying disordered proteins by the CH-CDF plot method. In: Pacific symposium on biocomputing, pp 128–139 [PubMed]

- 58.Oates ME, Romero P, Ishida T, Ghalwash M, Mizianty MJ, Xue B, Dosztanyi Z, Uversky VN, Obradovic Z, Kurgan L, Dunker AK, Gough J. D(2)P(2): database of disordered protein predictions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(Database issue):D508–D516. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ishida T, Kinoshita K. PrDOS: prediction of disordered protein regions from amino acid sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(Web Server issue):W460–W464. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Szklarczyk D, Franceschini A, Kuhn M, Simonovic M, Roth A, Minguez P, Doerks T, Stark M, Muller J, Bork P, Jensen LJ, von Mering C. The STRING database in 2011: functional interaction networks of proteins, globally integrated and scored. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(Database issue):D561–D568. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Meszaros B, Simon I, Dosztanyi Z. Prediction of protein binding regions in disordered proteins. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009;5(5):e1000376. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dosztanyi Z, Meszaros B, Simon I. ANCHOR: web server for predicting protein binding regions in disordered proteins. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(20):2745–2746. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dosztanyi Z, Csizmok V, Tompa P, Simon I. The pairwise energy content estimated from amino acid composition discriminates between folded and intrinsically unstructured proteins. J Mol Biol. 2005;347(4):827–839. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.01.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Alonso-Lopez D, Gutierrez MA, Lopes KP, Prieto C, Santamaria R, De Las Rivas J. APID interactomes: providing proteome-based interactomes with controlled quality for multiple species and derived networks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(W1):W529–W535. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chatr-Aryamontri A, Breitkreutz BJ, Oughtred R, Boucher L, Heinicke S, Chen D, Stark C, Breitkreutz A, Kolas N, O’Donnell L, Reguly T, Nixon J, Ramage L, Winter A, Sellam A, Chang C, Hirschman J, Theesfeld C, Rust J, Livstone MS, Dolinski K, Tyers M. The BioGRID interaction database: 2015 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(Database issue):D470–D478. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Salwinski L, Miller CS, Smith AJ, Pettit FK, Bowie JU, Eisenberg D. The database of interacting proteins: 2004 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(Database issue):D449–D451. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Keshava Prasad TS, Goel R, Kandasamy K, Keerthikumar S, Kumar S, Mathivanan S, Telikicherla D, Raju R, Shafreen B, Venugopal A, Balakrishnan L, Marimuthu A, Banerjee S, Somanathan DS, Sebastian A, Rani S, Ray S, Harrys Kishore CJ, Kanth S, Ahmed M, Kashyap MK, Mohmood R, Ramachandra YL, Krishna V, Rahiman BA, Mohan S, Ranganathan P, Ramabadran S, Chaerkady R, Pandey A. Human protein reference database—2009 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(Database issue):D767–D772. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kerrien S, Aranda B, Breuza L, Bridge A, Broackes-Carter F, Chen C, Duesbury M, Dumousseau M, Feuermann M, Hinz U, Jandrasits C, Jimenez RC, Khadake J, Mahadevan U, Masson P, Pedruzzi I, Pfeiffenberger E, Porras P, Raghunath A, Roechert B, Orchard S, Hermjakob H. The IntAct molecular interaction database in 2012. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(Database issue):D841–D846. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Licata L, Briganti L, Peluso D, Perfetto L, Iannuccelli M, Galeota E, Sacco F, Palma A, Nardozza AP, Santonico E, Castagnoli L, Cesareni G. MINT, the molecular interaction database: 2012 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(Database issue):D857–D861. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Huttlin EL, Ting L, Bruckner RJ, Gebreab F, Gygi MP, Szpyt J, Tam S, Zarraga G, Colby G, Baltier K, Dong R, Guarani V, Vaites LP, Ordureau A, Rad R, Erickson BK, Wuhr M, Chick J, Zhai B, Kolippakkam D, Mintseris J, Obar RA, Harris T, Artavanis-Tsakonas S, Sowa ME, De Camilli P, Paulo JA, Harper JW, Gygi SP. The BioPlex network: a systematic exploration of the human interactome. Cell. 2015;162(2):425–440. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.06.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rose PW, Prlic A, Bi C, Bluhm WF, Christie CH, Dutta S, Green RK, Goodsell DS, Westbrook JD, Woo J, Young J, Zardecki C, Berman HM, Bourne PE, Burley SK. The RCSB Protein Data Bank: views of structural biology for basic and applied research and education. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(Database issue):D345–D356. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Seetharaman SV, Taylor AB, Holloway S, Hart PJ. Structures of mouse SOD1 and human/mouse SOD1 chimeras. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2010;503(2):183–190. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kaur SJ, McKeown SR, Rashid S. Mutant SOD1 mediated pathogenesis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Gene. 2016;577(2):109–118. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2015.11.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hayashi Y, Homma K, Ichijo H. SOD1 in neurotoxicity and its controversial roles in SOD1 mutation-negative ALS. Adv Biol Regul. 2016;60:95–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jbior.2015.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rajagopalan K, Mooney SM, Parekh N, Getzenberg RH, Kulkarni P. A majority of the cancer/testis antigens are intrinsically disordered proteins. J Cell Biochem. 2011;112(11):3256–3267. doi: 10.1002/jcb.23252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gal J, Kuang L, Barnett KR, Zhu BZ, Shissler SC, Korotkov KV, Hayward LJ, Kasarskis EJ, Zhu H. ALS mutant SOD1 interacts with G3BP1 and affects stress granule dynamics. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;132(4):563–576. doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1601-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Niwa J, Ishigaki S, Hishikawa N, Yamamoto M, Doyu M, Murata S, Tanaka K, Taniguchi N, Sobue G. Dorfin ubiquitylates mutant SOD1 and prevents mutant SOD1-mediated neurotoxicity. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(39):36793–36798. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206559200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]