Abstract

Aging is a biological process characterized by progressive decline in physiological functions, increased oxidative stress, reduced capacity to respond to stresses, and increased risk of contracting age-associated disorders. Mitochondria are referred to as the powerhouse of the cell through their role in the oxidative phosphorylation to generate ATP. These organelles contribute to the aging process, mainly through impairment of electron transport chain activity, opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore and increased oxidative stress. These events lead to damage to proteins, lipids and mitochondrial DNA. Cardiolipin, a phospholipid of the inner mitochondrial membrane, plays a pivotal role in several mitochondrial bioenergetic processes as well as in mitochondrial-dependent steps of apoptosis and in mitochondrial membrane stability and dynamics. Cardiolipin alterations are associated with mitochondrial bienergetics decline in multiple tissues in a variety of physiopathological conditions, as well as in the aging process. Melatonin, the major product of the pineal gland, is considered an effective protector of mitochondrial bioenergetic function. Melatonin preserves mitochondrial function by preventing cardiolipin oxidation and this may explain, at least in part, the protective role of this compound in mitochondrial physiopathology and aging. Here, mechanisms through which melatonin exerts its protective role against mitochondrial dysfunction associated with aging and age-associated disorders are discussed.

Keywords: Melatonin, Mitochondrial bioenergetics, Cardiolipin, Aging

Introduction

Aging is a complex and multifactorial biological process characterized by a general and progressive decline in the intrinsic physiological function of several tissues, with a more pronounced effect on brain and heart function. The exact mechanisms underlying the aging process are still not well understood. As hypothesized by the free radical theory of aging, reactive oxygen species (ROS), produced as byproducts of biological oxidations, cause random and cumulative oxidative damage to biological constituents leading to cellular dysfunction with age and eventually cell death [1]. Mitochondria are intimately implicated in the aging process. In fact, these organelles are considered the main intracellular source of ROS, and at the same time, the major target of their oxidative attack. According to the mitochondrial theory of aging, ROS produced by the mitochondrial respiratory chain activity, attack mitochondrial constituents, including proteins, lipids, and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) [2–4]. ROS-induced cumulative damage to mtDNA with aging may lead to DNA strand breaks and to the occurrence of somatic mtDNA mutations [5, 6] which in turn, may lead to impairment of the respiratory chain complexes activity with increased ROS production and additional mitochondrial DNA mutations. This sequence of events triggers a vicious cycle that leads to a progressive decline in cellular and tissue function as a result of insufficient supply of energy and/or increased susceptibility to apoptosis [5, 7, 8]. The age-associated increase in oxidative damage to DNA, lipids, and proteins has been well documented [9–14]. Although there is a large consensus in the literature on the mitochondrial free radical theory of aging, recent studies, obtained in particular in Caenorhabditis elegans and in rodents, have challenged this theory [15].

In the last few years, dietary administration of a range of pharmacological agents, vitamins, or other nutritional antioxidant compounds has proven particularly useful in retarding the onset of age-related deficits in brain and heart tissues functioning by modulating mitochondrial ROS production. Nowadays, there is growing interest in discovering new compounds with antioxidants properties and low toxicity that are easily accessible to cellular and subcellular compartments, in particular mitochondria, the main locus of ROS production [16–18].

Melatonin (N-acetyl-5-methoxytryptamine) is an endogenously produced highly conserved molecule derived from the essential amino acid tryptophan that is found in all organisms from unicells to vertebrates [19, 20]. Melatonin and its metabolites function as endogenous free radical scavengers and broad-spectrum antioxidants [21–23]. Due to its amphiphilic nature, melatonin reaches several cellular compartments, especially mitochondria [24]. Most of the beneficial consequences resulting from melatonin administration may depend on its effect on mitochondrial physiology [25–29].

Recent studies have clearly shown that melatonin plays an effective role in preserving mitochondrial homeostasis [26, 28, 30, 31] and this may explain the beneficial effect of melatonin in several physiopathological conditions characterized by mitochondrial dysfunction, such as neurological [29, 32] and cardiovascular disorders [33–35] as well as aging [36, 37]. The protective effect of melatonin may be explained, at least in part, by its antioxidant properties, thus preserving the structural and functional properties of mitochondrial membranes [38].

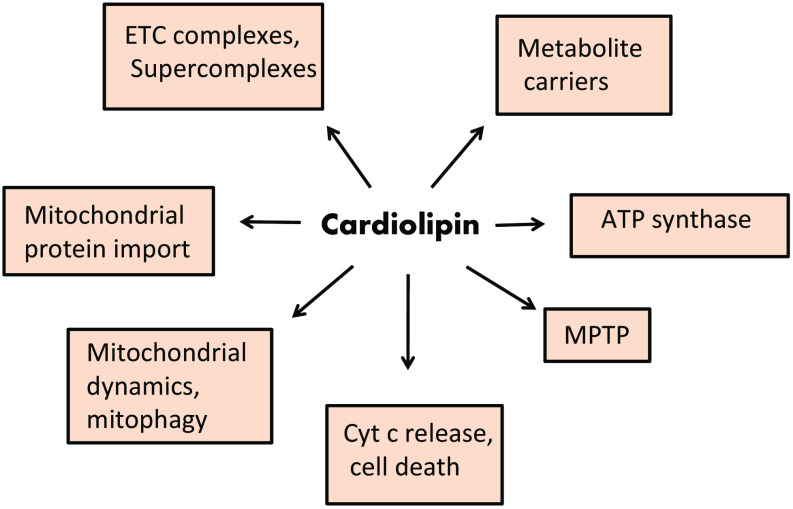

Cardiolipin (CL), is a phospholipid located at the level of the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM) where it is biosynthesized. Growing evidence indicates that this phospholipid plays an important role in several biochemical processes of the mitochondrial function (Fig. 1). In fact, CL has been reported to be involved in the modulation of mitochondrial bioenergetics, optimizing the activity of key mitochondrial IMM proteins involved in oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) [39–42]. Cardiolipin is also involved in mitochondrial-dependent steps of apoptosis, mitochondrial membrane stability and dynamics and mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MPTP) [43, 44]. Alterations in CL structure and/or composition have been shown to affect the fluidity and folding of the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM) [42]. These alterations affect the stabilization and function of the respiratory chain complexes and/or their organization in supercomplexes [45–47]. In particular, oxidation and depletion of CL is associated with mitochondrial dysfunction in several metabolic and degenerative diseases [43, 48, 49].

Fig. 1.

Proposed roles of cardiolipin in mitochondrial function. For details, see the text. CL cardiolipin, ETC electron transport chain, MPTP mitochondrial permeability transition pore, Cyt c cytochrome c

Results obtained in our laboratory have shown that melatonin preserves mitochondrial CL from ROS attack, and this may explain, at least in part, the beneficial effect of this indoleamine against mitochondrial dysfunction associated with several pathophysiological conditions, as well as with aging [43, 50, 51]. In this review, we discuss the mechanisms by which melatonin exerts its protective role against mitochondrial dysfunction associated with aging and age-associated disorders.

Mitochondria and oxidative stress

The main function of mitochondria within the cell is that of producing ATP through the OXPHOS process associated with the electron transport chain (ETC). The ETC machinery is composed of four electron carrier enzymes located at the level of IMM, namely complex I (CI) (NADH-ubiquinone reductase), complex II (CII) (succinate-ubiquinone reductase), complex III (CIII) (ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase) and complex IV (CIV) (cytochrome c oxidase). The electrons flow from NADH + H+/FADH2 to molecular oxygen, resulting in the reduction of oxygen to water at the level of complex IV. This process is associated with proton (H+) pumping at the level of CI, CIII and CIV to generate an electrochemical gradient, the main contributor to the mitochondrial membrane potential, which is the driving force of ATP synthesis. The return flux of H+ into the matrix through the ATP synthase enzyme complex leads to the synthesis of ATP which is than translocated by the ADP/ATP carrier (ANT) to the intermembrane space, in exchange with ADP. Mitochondrial OXPHOS process consumes 80–90% of a cell’s oxygen. This process, however, can lead to the production of potentially harmful chemical species, such as ROS. The mitochondrial ETC transport chain is the main locus of ROS production within the cell. It has been reported that around 0.2–2% of the oxygen utilized by the cell is transformed by mitochondrial ETC mainly into superoxide anion (O·−2) [52], which is then converted to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) by spontaneous dismutation or by the reaction catalyzed by superoxide dismutase (SOD). Hydrogen peroxide, in turn, is converted to water by glutathione peroxidase or catalase enzymes. Alternatively, in the presence of iron or other divalent cations, H2O2 can undergo Fenton’s reaction producing hydroxyl radical (·OH). This oxygen radical is considered highly harmful to the mitochondrial and cellular constituents. The mechanisms and the sites of superoxide anion generation along the mitochondrial ETC have been largely investigated [53]. Complex I and complex III are considered the primary locus of O·−2 production. O·−2 is mainly generated at the level of mitochondrial complex I, under conditions of high matrix NADH + H+/NAD+ ratio, leading to a reduced FMN site on complex I. O·−2 can be produced also under conditions of high proton motive force and low rates of ATP synthesis [53]. The ubiquinone (CoQ) pool or cytochrome b is considered the sites of superoxide production at the level of mitochondrial complex III. The amount of mitochondrial ROS production by complex I and III appears to be dependent on mitochondrial metabolic situations. O·−2 generation is particularly abundant under state 4 respiration, low oxygen consumption, high protonmotive force and when ETC complexes are in reduced state [54]. ROS are also produced in extramitochondrial compartments by xanthine oxidase, d-amino oxidase, the P-450 cytochromes and proline and lysine hydroxylase.

The generation of ROS within mitochondria could be modulated by nitric oxide (NO). This compound can be transformed to various reactive nitrogen species, including nitroxyl anion (NO−) or the toxic peroxynitrite (ONOO−) [55]. It has been found that mitochondria can generate NO by the activity of mitochondrial nitric oxide synthase [56]. Mitochondrial ROS production is also modulated by endogenous NO. Under conditions of low NO levels, the production of O·−2 and H2O2 can be increased by NO-induced modulation of the rate of oxygen consumption at the level of cytochrome c oxidase [57], while high NO levels inhibit H2O2 production by reacting with O·−2 resulting in ONOO− formation [58]. Both NO and ONOO− can also trigger free radical- mediated chain reactions that, in turn, affect proteins, lipids and DNA molecules [59]. Mitochondrial ETC alterations can lead to the collapse of mitochondrial membrane potential with further ROS production. This sequence of events can trigger a vicious cycle that ultimately leads to cell death.

A complex of enzymatic and nonenzymatic antioxidant systems are present within mitochondria to detoxify ROS. Nonenzymatic components include hydrophilic and lipophilic radical scavengers, such as cytochrome c, α-tocopherol, ascorbate, ubiquinone, glutathione, and melatonin. In addition, a specific mitochondrial defense mechanism is represented by the mild uncoupling that attenuates the increase in membrane potential and thus, O·−2 production. Antioxidant defense systems include several enzymes, such as manganese superoxide dismutase (Mn-SOD), catalase, glutathione peroxidase and phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase. The redox cycling in the mitochondria is involved in preventing significant loss of glutathione (GSH). Melatonin promotes de novo synthesis of GSH, either by enhancing the activity of the enzyme γ-glutamyl-cysteine synthase [60], or modulating gene expression of glutathione peroxidase, SOD and catalase [61]. This effect promotes the recycling of GSH, thus maintaining high reduced glutathione/oxidized glutathione (GSH/GSSG) ratio. These effects of melatonin may have important implications in mitochondrial physiology and physiopathology [37].

Mitochondria, oxidative stress and melatonin

Mitochondria are the main locus of ROS production and also the target for their damaging attack. The interaction of ROS with mitochondrial constituents affects the function of these organelles, altering cell viability and triggering cell death. MtDNA, which encodes proteins of the ETC and OXPHOS system are important target of ROS attack. Because of its proximity to the ETC and the lack of protective histones, mtDNA is particularly susceptible to ROS attack. Therefore, ROS-induced mtDNA damage, affecting the ETC activity, mitochondrial membrane potential and ATP generation, may lead to cell injury and cell death. It has been reported that the level of oxidatively modified bases in mitochondrial DNA is higher than that found in nuclear DNA [62]. Somatic mtDNA mutations acquired during a life span contribute to the physiological decline that occurs with aging. Large-scale deletions and point mutations in specific mtDNA control regions, which are the most studied mtDNA mutations that accumulate with aging, correlate with a progressive decline in mitochondrial function. Oxidative damage to mtDNA can be propagated as the mitochondria and cell divide, thus amplifying the physiological consequences of the damage [63].

ROS-induced structural and functional alterations to proteins is considered an important factor in the aging process and in age-related disorders in biological systems [64]. Several factors may contribute to modulate the level of oxidative damage to proteins with age, including the proximity of the proteins to the site of ROS generation and the nature and concentration of antioxidants. Increased level of oxidized mitochondrial proteins with age has been mainly detected by analysing carbonyl derivatives, loss of sulfhydryl groups and oxidation products of specific amino acids such as tyrosine and methionine [65, 66].

Phospholipids are important structural constituents of the biological membranes. At mitochondrial level, these compounds play an essential role in the modulation of membrane permeability and membrane fluidity, both of which are crucial for optimal function of proteins and enzymes. Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) are structural components of mitochondrial phospholipids. The methylene bridge between two double bonds of unsaturated fatty acids, renders these compounds particularly susceptible to ROS attack. ROS-induced lipid peroxidation triggers long free radical chain reactions producing hydroperoxides and endoperoxides. These lipid peroxidation products can undergo fragmentation, generating a variety of reactive intermediates, among them are malondialdehyde (MDA) and the most reactive 4-hydroxy-trans-2-nonenal (HNE). ROS-induced alterations to membrane phospholipids is widely recognized as an important contributing factor in mitochondrial dysfunction in several physiopathological conditions, as well as in aging. Peroxidized lipids affect the mitochondrial membrane bilayer organization, thus altering membrane fluidity and permeability. These alterations, in turn, affect mitochondrial ETC activity and OXPHOS process, mitochondrial membrane potential and mitochondrial Ca2+ buffering capacity [67].

Melatonin is well recognized as a potent scavenger of ROS, including the hydroxyl radical, peroxyl radical, superoxide anion radical, hydrogen peroxide and reactive nitrogen species [68, 69]. Due to its capacity to stimulate several antioxidant enzymes, including superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase and down-regulate pro-oxidant enzymes, melatonin is also recognized as an indirect antioxidant agent [70–72]. Therefore, this indoleamine plays an important role in antioxidant defense, preserving mitochondrial homeostasis, reducing ROS generation and stimulating ETC complex activity [26, 31, 51, 73, 74].

Due to their proximity to the locus of ROS production, polyunsaturated fatty acids are particularly sensitive to oxidative damage. In addition, because lipid peroxidation has a deleterious effect on cell membranes structure and function, there is great interest in identifying compounds able to reduce the onset and progression of this process. Melatonin and its derivatives have been shown to exert a protective effect against lipid peroxidation in mitochondrial membranes [38, 75], although the exact mechanism underlying this effect is not yet established. It has been reported that melatonin is able to scavenge the peroxyl radical PLOO· [76, 77], which is produced during lipid peroxidation and is involved in the propagation of this process. Melatonin was shown to be more effective than vitamin E in neutralizing PLOO· and in inhibiting lipid peroxidation [76, 78]. Another compound involved in lipid peroxidation is ONOO− which is a powerful initiator of lipid breakdown. By neutralizing ONOO−, melatonin may protect membrane lipids [69]. It has been suggested that melatonin exerts its protective effect against lipid peroxidation by reacting with the radicals that initiate this process, especially ·OH and ONOO− [79]. Because of its amphiphilic nature, melatonin may accumulate into cellular and subcellular compartments. In vitro experiments have shown that melatonin inhibits lipid peroxidation in rat brain homogenates, brain and liver microsomes and mitochondria treated with ascorbate-Fe2+ system [80]. Melatonin protection against lipid peroxidation has been shown in a variety of experimental animal models [81, 82].

Mitochondrial membranes are biological structures, the fluidity of which is required for their optimal functioning. Phospholipids containing PUFAs are the main contributing factor to achieve the proper membrane fluidity. Therefore, oxidative damage to PUFAs results in a decrease of the mitochondrial membranes fluidity. The protection of PUFAs from ROS attack is crucial for optimal functioning of mitochondrial membranes. Melatonin, by preventing lipid peroxidation, could maintain the optimal fluidity and function of the mitochondrial membranes. Aging is characteristically associated with a decrease in cell membrane fluidity. Reduced level of melatonin found in aging may be responsible for an increase in lipid peroxidation and consequently for a more rigid cellular membranes [83, 84]. In line with this, it has been reported that treatment of senescence-accelerated prone mice with melatonin maintains the proper mitochondrial membranes fluidity [38].

Melatonin and mitochondrial bioenergetics

Due to its small size and its highly lipophilic nature, melatonin crosses cell membranes to easily reach cellular and subcellular compartments, including mitochondria. Melatonin seems to accumulate in mitochondria against a concentration gradient. The existence of specific melatonin transporter at the level of mitochondrial membrane has also been suggested [30]. This indoleamine has been shown to modulate mitochondrial homeostasis by stabilizing IMM, thereby improving ETC and mitochondrial function [26, 28, 73, 74]. Melatonin was reported to increase the activity of CI and CIV in mitochondria isolated from rat brain and liver tissues, while having no effect on CII and CIII [73]. The stimulatory effect of melatonin on the CI and CIV activities may be due in principle to its antioxidant effects. In addition, due to its high redox potential (0.94 V), melatonin may interact with the ETC enzyme complexes by donating and accepting electrons, thereby increasing electron flux. This effect is not shared by other antioxidant compounds [85].

Melatonin may influence mitochondrial bioenergetic parameters by modulating the oxygen consumption and membrane potential [74]. In vitro experiments carried out with normal mitochondria, have shown that melatonin protected the mitochondrial function against ROS-induced oxidative attack, lowering oxygen consumption in the presence of ADP. This resulted in a reduction of the membrane potential and subsequently in the inhibition of O·−2 and H2O2 production [74]. In addition, melatonin maintained the respiratory control ratio, the efficiency of the OXPHOS process and ATP production, while enhancing the activity of ETC complexes (mainly CI, CIII and CIV). The fact that mitochondria can accumulate melatonin in high concentration is of great pharmacological interest. This means that, following exogenous administration in vivo, this indoleamine reaches the mitochondrial compartment and exerts its beneficial effect on mitochondrial function.

Melatonin may also modulate mitochondrial membrane potential needed for ATP generation and for maintaining the proper function of mitochondria. Uncoupling proteins (UCPs) are components of the IMM which play an important role in the modulation of mitochondrial membrane potential. Melatonin has been shown to enhance the activity of UCPs either upregulating gene expression or directly interfering with these proteins. This results in a mild reduction of membrane potential and decrease in ATP production. The lowered ATP production caused by activation of UCPs may be counteracted by the lower leaked electrons and increased electron flux through ETC induced by melatonin [30, 86].

Cardiolipin and mitochondrial function

Cardiolipin is generally referred to as the signature phospholipid of mitochondria. This phospholipid is located in biological membranes involved in the generation of electrochemical gradient used to synthesize ATP, such as bacterial plasma membrane and the inner mitochondrial membrane [41]. It is widely recognized that cardiolipin plays a pivotal role in the modulation of a variety of reactions and processes of the mitochondrial bioenergetics [41, 42]. In fact, CL has been shown to interact with a number of IMM proteins and enzymes including, among others, the ETC complexes involved in OXPHOS [40, 87, 88] and the metabolite carriers [89] notably ANT. Furthermore, CL seems to play a crucial role in the association, stabilization and organization of respiratory chain complexes into supercomplexes [42, 46, 90]. Cardiolipin is also required for the interaction between ANT protein and respiratory supercomplexes [47]. Very recently, a possible role for CL on ATP synthase functioning has been proposed [91].

Cardiolipin molecules participate in the process of apoptosis in animal cells by interacting with a number of death-inducing proteins, including cytochrome c [92, 93] which acts also as peroxidase, by reacting specifically with CL, causing oxidation and then hydrolysis of the product CL hydroperoxide [44]. As consequence, cytochrome c is released into the intermembrane space, while the oxidized CL is transferred to the outer mitochondrial membrane where it participates, together with other factors, to the opening of the MPTP [94]. The opening of MPTP facilitates the release of several proapoptotic factors, including cytochrome c, from mitochondria into the cytosol where they trigger the apoptotic process. Recent studies have shown that CL plays an important role in mitochondrial morphology and dynamics, including fusion and fission processes [95], as well as in the protein insertion and assembly into the mitochondria [96]. Because of many roles played by CL in mitochondrial metabolism, it is plausible that alterations in CL structure, content and fatty acyl chain composition may lead to mitochondrial dysfunction in a variety of physiopathological states and diseases [43, 48]. Cardiolipin alterations may occur mainly as a consequence of loss in the CL content, changes in acyl chain composition or CL oxidation.

Effect of melatonin on cardiolipin oxidation

Due to their high chemical reactivity, ROS are particularly damaging in the proximity of the site of their production. Mitochondrial membrane constituents such as phospholipid components rich in PUFAs are the primary target of ROS attack. Among phospholipids, CL molecules are especially susceptible to ROS-induced attack, either because of their close location to the site of ROS production or because of their high content of PUFAs. In fact, CL molecules are rich in unsaturated fatty acyl chains, notably linoleic acid in heart and liver, or docosahexaenoic and arachidonic acids in brain tissue mitochondria. Recent studies have shown that HNE is one of the major product of CL oxidation [97]. HNE is known to affect the structural integrity and several parameters of mitochondrial function, such as protein transportation, respiratory metabolism for ATP generation, mitochondrial dynamics and mitophagy quality control through fission and fusion of mitochondria. All these HNE-induced alterations have been associated with human disorders [98].

It has been shown that melatonin and its derivatives protect against ROS-mediated lipid peroxidation in mitochondrial membranes [38, 75, 99]. In line with this, our studies have demonstrated that melatonin is able to inhibit CL oxidation in isolated rat heart and brain mitochondria [50, 100]. Treatment of mitochondria with t-butylhydroperoxide (t-BuOOH), a lipid-soluble hydroperoxide known to induce lipid peroxidation in biological membranes, in the presence of copper ions, resulted in an oxidation/depletion of CL. These CL changes were prevented by melatonin. The protection afforded by melatonin against CL alterations can be reasonably explained on the ability of this indoleamine to inhibit the peroxidation of linoleic acid, the main constituents of CL molecules. Consistently, results by others have demonstrated the antioxidant effect of melatonin on linoleate oxidation initiated by HO· free radical generated by water gamma radiolysis [101]. Conjugated dienes and hydroperoxides were measured as an index of lipid peroxidation on a lipid model of linoleate micelles. Melatonin displayed strong in vitro lipid peroxyl radicals (LOO·) scavenging properties, as shown by its inhibitory effect on the radiation-induced peroxidation of linoleate.

Emerging insights have linked CL oxidation/depletion to mitochondrial dysfunction in a number of disorders and physiopathological settings including heart ischemia/reperfusion, diabetes, aging and age-associated diseases [43, 48]. Cardiolipin oxidation appears also to play a role in the modulation of several of the mitochondrial steps of cell death as well as of mitochondrial dynamics [43, 93]. Thus, the ability of melatonin to preserve CL integrity by ROS attack in mitochondria, may have important implications in mitochondrial dysfunction associated with multiple physiopathological situations. As mentioned above, HNE is one of the major products of CL oxidation [97]. The ability of melatonin to prevent CL oxidation will result in a lower generation of HNE, thus reducing its damaging effects on mitochondrial membranes structure and function. This may represent an additional mechanism through which melatonin protects against oxidative stress-induced mitochondrial dysfunction.

Mitochondrial ETC dysfunction in aging and the effect of melatonin

A decrease in electron transport activity in mitochondria isolated from rat and mouse tissues upon aging is well documented [102–104]. Complex I and IV show a reduced enzymatic activity in mitochondria isolated from various tissues of rats and mice upon aging [102, 105–107]. Oxidation/depletion of mitochondrial cardiolipin may underlie the age-related impairment of CI and CIV activity. In fact, the content of normal CL was found to decline, while the level of oxidized CL to increase during aging process [106, 107]. Complex I and IV of the ETC bind selectively CL molecules and this phospholipid seems to be required for the optimal activity of these respiratory chain complexes [45, 108]. Furthermore, mitochondrial mediated ROS production impairs CI and CIV activity via CL oxidation [43]. Altogether, these results suggest that ROS-induced oxidative alteration to mitochondrial CL is involved in the age-associated defects of mitochondrial CI and CIV activities. Complexes I and IV alterations might be implicated in ROS generation during the aging process. In fact, the impairment of the activity of mitochondrial CI and CIV, may enhance the electron leak from the ETC, generating more superoxide radical. All these events may trigger a cycle of oxidative damage that leads to mitochondrial bioenergetic decay in aging [8, 104, 109]. The age-related defect in mitochondrial CI and CIV activity in heart and brain tissues, may be implicated in the etiopathology of age-associated cardiovascular and neurodegenerative disorders and, at the same time, may represent a central target for the development of potential therapeutic strategies.

A number of biochemical and biophysical experimental data obtained in various laboratories have shown that the individual components of the mitochondrial respiratory chain are organized as large supramolecular assemblies, named mitochondrial supercomplexes [46, 90]. Various models of supercomplexes, involving components of the ETC (complexes I, II, III and IV), complex V and ANT, have been suggested [46, 47, 110]. Such supercomplex organization of the respiratory chain seems to optimize the efficiency of electron/proton flux and hence, that of ATP synthesis. In addition, the supercomplex organization of the ETC, seems to minimize the production of reactive oxygen species [110]. It has been suggested that CL molecules may be implicated in the respiratory supercomplex organization and stability in mammalian mitochondria [111]. Accordingly, aberrant respiratory supercomplexes were reported in fibroblasts derived from Barth syndrome, an X-linked recessive disease, associated with abnormalities in CL content [112]. Yet, destabilization of ETC supercomplexes was observed in mitochondria isolated from rat heart upon aging [113]. Collectively, these data suggest that oxidation/depletion of CL with aging, might be, at least in part, responsible for the destabilization of the ETC supercomplexes and hence, for the dysfunction of mitochondrial respiratory chain activity. This may represent a contributing factor to mitochondrial bioenergetics decay with aging.

It is well accepted that melatonin has a beneficial effect against mitochondrial dysfunction associated with aging process [27, 29]. Melatonin mitigates mitochondrial decay in brain aging [36] and it is recognized as a potential mitochondria-targeted protector against ROS-induced oxidative stress associated with brain aging and related disorders [114, 115]. Our data showed CI and CIV dysfunction, decrease in both oxygen consumption and membrane potential, as well as an increase in ROS production in rat brain mitochondria with aging [51, 103]. All these alterations in mitochondrial function were largely mitigated by melatonin treatment. The protection afforded by melatonin against age-associated changes of mitochondrial bioenergetic in rat brain, could be ascribed to the ability of this indoleamine to preserve CL integrity by ROS-attack. This is also supported by our in vitro experiments on isolated rat brain mitochondria [51].

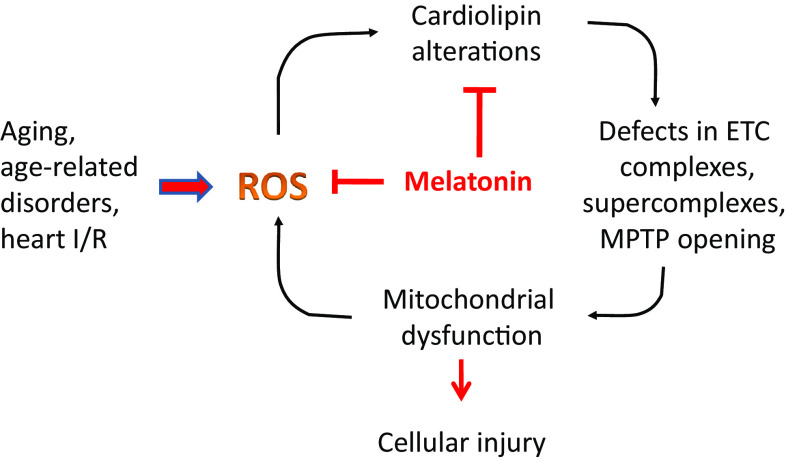

Complex I and IV are considered rate-limiting factors of the mitochondrial ETC and hence, of the modulation of OXPHOS process. ROS-induced cardiolipin alteration leading to CI and CIV dysfunction may increase ROS production, thus triggering an amplification of oxygen radical-induced membrane damage. This vicious cycle may be implicated in mitochondrial dysfunction and bioenergetics decline in brain function with aging. The ability of melatonin to inhibit mitochondrial cardiolipin oxidation, may be critical in preventing CI and CIV dysfunction and ROS-induced progression and amplification of oxidative stress during the aging process in brain tissue (Fig. 3). Therefore, administration of melatonin, by preserving CL integrity, could represent a useful strategy against the age-dependent mitochondrial oxidative damage, leading to the improvement of mitochondrial bioenergetics and brain function. This beneficial effect could be obtained also by melatonin’s metabolites.

Fig. 3.

Cardiolipin alterations in mitochondrial dysfunction in aging and physiopathology and proposed mechanisms of melatonin protection. For details, see the text. ETC electron transport chain, MPTP mitochondrial permeability transition pore, I/R ischemia/reperfusion

Complex I and IV dysfunction has been implicated in a wide spectrum of age-related neurodegenerative disorders, in particular Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases [116, 117]. It has been reported that defect in CI activity, which occurs in various neurodegenerative disorders, sensitizes neurons, via mitochondrial cardiolipin oxidation, to the action of death agonists such as Bax [118]. Melatonin administration may lead to the improvement of mitochondrial function and then, health in aging. Thus, this indoleamine treatment may represent an efficient therapeutic tool against cellular bioenergetics decay with aging and age-associated neurodegenerative disorders in which both mitochondrial ETC deficiency and cardiolipin oxidation could play a critical role.

The mitochondrial permeability transition pore

Mitochondria play a central role in cell metabolism by providing energy and modulating intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis and cellular redox status. Under physiological condition, the IMM is impermeable to almost all metabolites and ions. The mitochondrial permeability transition is a large nonspecific channel in the IMM whose opening is triggered by many stimuli, including high matrix Ca2+, elevated phosphate concentrations, low adenine nucleotide levels and oxidative stress. Opening of MPTP induces passive diffusion of any molecules of 1.5 kDa, collapse of membrane potential and uncoupling of OXPHOS that ultimately leads to mitochondrial dysfunction and cell death predominantly through necrosis [119, 120].

Despite extensive studies, the exact molecular identity of MPTP remains unresolved. Three protein molecules were accepted as key structural components of the MPTP, including ANT in the IMM, cyclophilin D (Cyp-D) in the matrix and VDAC (also known as porin) in the outer membrane. Benzodiazepine receptors, creatine kinase, hexokinase and Bcl-2 family members have been also suggested as structural components of the MPTP, although the evidence for their involvement in this process has been questioned. Cyclophilin D is a nuclear encoded mitochondrial isoform of cyclophilin which is widely accepted as crucial component of MPTP, as shown by the inhibition of pore opening by cyclosporine A (CsA) [119]. The central role of Cyp-D in MPTP formation is confirmed by the finding that mitochondria isolated from Cyp-D knockout mice exhibited a lower sensitivity to Ca2+. In addition, these mitochondria exhibited a delayed MPTP opening that was insensitive to CsA [121]. Cyclosporine A inhibits MPTP opening by interacting with Cyp-D, thus reducing the sensitivity of pore opening to Ca2+. Adenine nucleotide translocator is believed as another protein component of the MPTP complex, as shown by the modulatory effects exerted by bongkrekic acid and carboxyatractyloside, two inhibitors of ANT, on MPTP opening [122]. In fact, bongkrekic acid inhibits MPTP opening by decreasing its sensitivity to Ca2+, while carboxyatractyloside promotes this process [123]. Other studies carried out with knockout mice showed that ANT was not directly involved in MPTP opening [124] but rather it may have a regulatory role on this process. Another activator of pore opening is inorganic phosphate (Pi). Recent studies have demonstrated the involvement of phosphate carrier in MPTP opening, as shown by the finding that CyP-D binds to this protein translocator in a CsA-sensitive manner [120]. Inorganic phosphate is required for inhibition of MPTP opening through blocking Cyp-D [125]. This result supports a potential involvement of the phosphate carrier in MPTP formation.

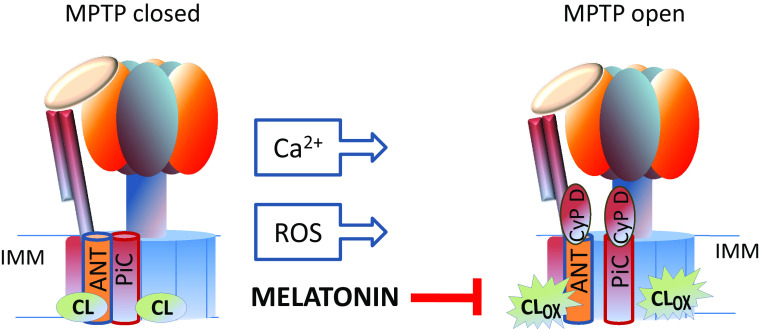

Very recently, the mitochondrial FoF1 ATP synthase or CV of the OXPHOS system has been proposed as a molecular component of MPTP [126]. This multi-subunit complex located in the IMM is a molecular motor which catalyzes the synthesis of ATP from ADP and Pi, by utilizing the transmembrane proton-motive force generated by the ETC. FoF1 ATP synthase enzyme complex is composed by soluble catalytic F1 and by a membrane-embedded Fo subcomplex. These sub-complexes are linked by a central and peripheral stalk. Cardiolipin molecules are essential components of the FoF1 ATP synthase. This phospholipid interacts specifically with the rotor of this enzyme complex, either lubricating its rotation or participating directly in the rotation supported by transmembrane proton motive force [91]. The involvement of mitochondrial FoF1 ATP synthase in the MPTP formation comes from the results of assays screening for potential CyP-D binding partners. CyP-D was shown to co-migrate with mitochondrial FoF1 ATP synthase in blue native gels [127] and the subunit OSCP (oligomycin sensitivity conferring protein) as a binding site [128]. Two possible main sites of pore-formation in mitochondrial FoF1 ATP synthase enzyme complex have been suggested: the monomer–monomer interface of the dimer [128] and the c-ring (also termed rotor ring) by itself or in the context of mitochondrial FoF1 ATP synthase [129]. As mentioned above, ANT and phosphate carrier (both of which bind CyP-D) are potential molecular components of the MPTP [130, 131]. It is well possible that an interaction between ANT, phosphate carrier and ATP synthase enzyme could be a contributing factor in pore formation. Such interaction may occur in the ATP-synthasome [132–134]. The oligomerization of this supercomplex has been reported to be modulated by cardiolipin [47, 135], which interacts with all these protein components of the pore. In addition, cardiolipin molecules have been shown to interact with the c subunit of Fo by solid state NMR studies with bacterial proteins [136]. It has also been suggested that Ca2+ ions, which are the main inducers of MPTP opening, bind to annular CL at the interface between the phosphate carrier, ANT and FoF1 ATP synthase [131]. On this basis, it is conceivable that alterations occurring in the structure, composition and especially in the degree of oxidation of CL may induce destabilization and conformational changes in the ATP-synthasome complex, thus favoring the MPTP opening (Fig. 2). This view is also supported by the finding that oxidized CL sensitizes mitochondria to Ca2+-induced MPTP opening [94]. The interaction of cardiolipin molecules with complex I may be of particular interest in view of the influence exerted by complex I on MPTP opening [137].

Fig. 2.

Possible role of oxidized cardiolipin in MPTP opening and protective effect of melatonin. For other details, see the text. ANT ADP/ATP carrier, PiC phosphate carrier, CL OX oxidized cardiolipin, CyP-D cyclophilin D, IMM inner mitochondrial membrane

Melatonin, cardiolipin and MPTP

A large body of evidence supports a role for the MPTP in the early stages of the apoptotic or necrotic pathway of cell death [43, 93, 134, 138]. Cytochrome c release from the mitochondria to the extramitochondrial compartment is a crucial event in triggering the apoptotic cascade that leads to programmed cell death. Cytochrome c is a protein component involved in the electron transport by the ETC. This hemoprotein is normally bound to the outer surface of the IMM. Cardiolipin molecules are involved in this binding [139] the strength of which is influenced by the molecular nature of CL. Oxidation of CL facilitates the detachment of cytochrome c from IMM and its release into the cytosolic space [93, 140]. Cytochrome c release from mitochondria occurs by a two-step process, the first of which is the dissociation of this protein from the IMM, followed by permeabilization of the outer mitochondrial membrane probably via its association with Bcl2 family proteins, such as Bax and Bid, and/or through the MPTP opening [93]. In addition, oxidation of cardiolipin molecules may promote the permeabilization of the outer mitochondrial membrane, probably through their association with Bcl2 family proteins such as Bax and Bid [44, 93].

Experiments carried out in our laboratory have shown that external added oxidized CL to mitochondria promotes Ca2+-induced MPTP opening [94]. It is suggested that Ca2+ and oxidized CL act synergistically in this process by interacting with components of the MPTP, probably with ATP-synthasome, inducing a conformational change of this multiprotein complex, thus promoting MPTP opening (Fig. 2). In addition, our studies have demonstrated that oxidation of intramitochondrial CL molecules, following treatment of mitochondria with t-BuOOH, enhanced the susceptibility to Ca2+-induced MPTP opening [50]. These results further confirm the involvement of oxidized CL in MPTP opening. As a consequence of MPTP opening by oxidized CL and Ca2+, cytochrome c is release from mitochondria into the cytosol. Addition of micromolar concentrations of melatonin inhibited either the Ca2+/t-BuOOH-induced CL peroxidation or MPTP opening [50]. Collectively, these results indicate that preservation of endogenous CL oxidation by melatonin underlie the protective effect exerted by this indolemaine on MPTP opening (Fig. 2). Moreover, melatonin prevented the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria to the cytosol associated with MPTP opening, under oxidative stress conditions. This effect of melatonin can be ascribed to its ability to prevent CL peroxidation, thereby inhibiting both cytochrome c detachment from the IMM and MPTP opening. The fact that melatonin is able to prevent MPTP opening and the associated cytochrome c release from mitochondria may have important implications in mitochondrial physiopathology. Alterations of Ca2+ homeostasis and accumulation of oxidized CL in mitochondria isolated from different tissues have been found in a number of physiopathological situations including aging, age-associated degenerative diseases, heart ischemia/reperfusion and diabetes.

A study carried out by others in primary skeletal muscle cultures, further confirmed the protective effect of melatonin on MPTP opening promoted by t-BuOOH-induced oxidative stress [141]. In fact, melatonin treatment fully prevented myotube death induced by t-BuOOH by inhibiting t-BuOOH-induced ROS generation. In isolated mitochondria, melatonin decreased the sensitivity of mitochondrial MPTP to Ca2+ and prevented t-BuOOH-induced mitochondrial swelling, pyridine nucleotide and GSH oxidation.

Melatonin, cardiolipin and heart ischemia/reperfusion

There is a general agreement for the involvement of mitochondria in the processes that lead to cell death following ischemia/reperfusion (I/R). These organelles are therefore potential target for cardioprotective intervention [142, 143]. Oxidative stress is a key factor in inducing lethal cell injury associated with cardiac I/R. A number of studies have shown that mitochondria isolated from I/R rat heart exhibit altered bioenergetic parameters, including lowered rate of mitochondrial oxygen consumption, complex I and III dysfunction and increased basal rate of H2O2 generation [144]. In addition, a decrease in the level of normal CL and an increase in the level of oxidized CL were found in mitochondria isolated from I/R rat heart. The alterations in the ETC complexes activity observed in mitochondria isolated from I/R rat heart seem to be due, at least in part, to ROS-induced CL oxidation. Melatonin administration to rat heart subjected to I/R prevented the alterations in CI and CIII activity and preserved CL integrity [27, 100, 144]. Similar protective effects by melatonin treatment were observed in in vitro experiments carried out on isolated rat heart mitochondria under oxidative stress conditions. The melatonin’s protective effect against I/R-induced mitochondrial dysfunction could be explained on the ability of this indoleamine to protect CL integrity from ROS attack and/or to directly improve the ETC activity. In addition, melatonin administration resulted in an improvement of post-ischemic hemodynamic function of the heart [145]. These results emphasize that melatonin-induced protection of mitochondrial function in heart failure could be of great interest for the cardioprotective actions afforded by this compound [27, 33–35].

A large body of experimental evidence indicates that MPTP opening plays a key role in cardiomyocytes cell death during I/R [134, 142, 143]. Mitochondrial Ca2+ accumulation and increased ROS levels occurring during reperfusion induce MPTP opening and cell death. As reported above, oxidized CL and Ca2+ overload act synergistically in promoting MPTP opening in cardiac I/R [144]. This assumption is also supported by the increased level of oxidized CL detected in mitochondria isolated from rat heart subjected to I/R. Melatonin administration to rat heart subjected to I/R resulted in both protection of CL oxidation and prevention of MPTP opening [145]. The protective effect of melatonin on mitochondria function is associated with an enhanced recovery of hemodynamic functions of the reperfused heart as well as a reduction in infarct size and a decrease in necrotic damage. Altogether, these data suggest that melatonin administration may represent a useful therapeutic strategy against cardiac reperfusion injury, as well as for other cardiovascular disorders associated with mitochondrial oxidative damage.

Melatonin, cardiolipin and MPTP in aging

Mitochondrial dysfunction associated with MPTP opening may be involved in the aging process and age-associated diseases [146]. Increased sensitivity to MPTP opening has been reported in aged or senescent cells, including lymphocytes, neurons, hepatocytes and cardiac myocytes. Mitochondria isolated from liver, brain and heart exhibit a higher susceptibility to Ca2+-induced MPTP opening with aging [147]. As described above, oxidized CL sensitizes rat heart mitochondria to Ca2+-induced MPTP opening. This process is associated with the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria to the cytosol [94]. Enhancement of CL oxidation in aging could increase the sensitivity to Ca2+-induced MPTP opening, thus promoting the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria to the extramitochondrial space. Consistently, we have reported that aging is associated with an increased sensitivity to Ca2+-induced MPTP opening and with an increased release of cytochrome c [148]. These events may be, at least in part, responsible for the increased extent of apoptosis reported in aged heart [149]. Long-term melatonin treatment prevented both the MPTP opening and the cytochrome c release. This protective effect afforded by melatonin against mitochondrial dysfunction with aging could be explained, in part, on its ability to preserve CL integrity, thereby preventing MPTP opening, and cytochrome c release from mitochondria. The increased susceptibility to Ca2+-induced MPTP opening and to cytochrome c release from mitochondria may represent an important contributing factor in necrotic and apoptotic myocyte cell death in aging, as well as in age-associated cardiovascular and neurodegenerative disorders.

Melatonin, cardiolipin and mitochondria in age-related neurodegenerative diseases

Mitochondria are thought to play a key role in the pathogenesis of age-associated neurodegenerative disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease (PD) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD). In fact, neurons are particularly vulnerable to mitochondrial dysfunction because of their high energy demand. Oxidative stress in neurodegenerative processes affects several bioenergetics parameters such as ATP synthesis, mitochondrial membrane potential, intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis, MPTP opening and cell signaling. Therefore, mitochondrial bioenergetics alterations induced by ROS-overproduction may have important implications in age-related neurodegenerative diseases characterized by a progressive mitochondrial dysfunction [150, 151].

Parkinson’s disease is a common progressive disorder of the central nervous system characterized by progressive loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra and production of intraneuronal protein aggregates. It is hypothesized that oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction are involved in PD pathogenesis. In fact, compounds which inhibit mitochondrial respiration and increase ROS production cause loss of dopaminergic neurons either in humans or in experimental animal models. A significant decrease in the activity of CI, as well as reduced levels and altered assembly of CI subunits, associated with oxidative stress and alterations in OXPHOS activity, have been observed in PD patients [150]. It has been reported that α-synuclein, the major structural constituent of cytoplasmic inclusions bodies (Lewy bodies), interacts with mitochondrial membranes. This interaction between these two factors might have important implications toward the complexities of PD [152]. As shown in in vitro studies, liposomes derived from mitochondrial membranes containing CL bind α-synuclein [153]. This binding is associated with the inhibition of mitochondrial fission and fusion cycle [154]. This is not surprising as CL is enriched in fusion events zones and seems to be involved in mitochondrial dynamics, including fusion and fission processes [155]. The specific binding of α-synuclein to CL in mitochondrial membranes, points to a potential role of this phospholipid in PD pathogenesis [156]. α-Synuclein knockout mice exhibit a defect in ETC activity with a parallel loss in mitochondrial CL content [157] suggesting a potential role of α-synuclein in brain phospholipid metabolism, mitochondrial function, and pathogenesis of PD. Interestingly, α -synuclein was found to form complexes with cytochrome c and CL and this results in the protection of neurons against apoptotic cell death in PD [158].

Melatonin has been reported to exert neuroprotective effect in animal experimental models of PD [32, 159, 160]. Long-term melatonin treatment in a chronic mouse model of PD was shown to preserve mitochondrial function, ATP synthesis and antioxidant enzymes activity [161]. Functional impairment of mitochondrial complex I has been associated with PD [116]. It has been reported that alteration in CI activity, which occurs in PD and other neurodegenerative disorders, sensitizes neurons to the action of death agonists such as Bax, via CL oxidation [118]. Melatonin was shown to have a protective effect against oxidative stress and the associated CI deficiency in mitochondria from substantia nigra and striatum in a mouse model of PD [162]. Moreover, this indoleamine binds with high affinity to CI and this binding could be, in part, responsible for the protection afforded by melatonin on this enzyme complex in the PD [163]. Very recently it has been reported that deletion of CyP-D, a crucial component of MPTP, delays the onset and the progression of this disease in mice model of PD, prolonging the survival [164, 165]. Moreover, CyP-D deletion protects neurons from apoptotic cell death in central nervous system. Collectively, these results point to a direct potential role of MPTP opening in the pathogenesis of PD. Thus, an additional mechanism through which melatonin protects against mitochondrial dysfunction associated with PD might be the inhibition of MPTP opening, probably by preserving mitochondrial CL integrity.

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is characterized by severe neurodegenerative alterations such as loss of neurons and synapses, neuronal atrophy and depletion of neurotransmitter systems. During AD progression there is also an accumulation of extracellular senile plaques of aggregated β-amiloide (Aβ) and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles containing hyperphosphorylated tau. AD is associated with a progressive loss of memory and cognition. Genetic factors, inflammation and oxidative stress have been suggested as possible underlying causes in the etiopathology of AD [166]. Mitochondrial dysfunction, in particular defects in the electron transport chain, appears to play a critical role in the pathogenesis of this common neurodegenerative disease [167, 168]. The most consistent alteration in the mitochondrial ETC enzymes in AD is a defect in cytochrome oxidase which results in an increased oxidative stress and impairment of mitochondrial and cellular metabolism. There is also substantial evidence showing that mitochondrial dysfunction is associated with the progressive accumulation of mitochondrial Aβ peptides which induce oxidative stress, impaired Ca2+ homeostasis and energy metabolism and induction of apoptosis [169, 170]. Melatonin has been proven particularly useful in antagonizing the effects of AD [29, 32]. The ability of melatonin to prevent mitochondrial alterations associated with AD was tested in young and senescent hippocampal neurons [171]. Neurons treatment with Aβ25–35 resulted in alterations of several mitochondrial bioenergetic parameters such as ETC impairment, loss of mitochondrial membrane potential and ATP content. All these mitochondrial bioenergetic alterations were attenuated by melatonin treatment. It was also shown, in transgenic AD mice and cultured cells, that melatonin treatment inhibits the increase of mitochondrial Bax and caspase-3 activity induced by Aβ-peptides [172, 173]. A possible involvement of MPTP in the etiopathogenesis of AD has been also suggested [174]. Melatonin indirectly inhibits the opening of the MPTP, the associated cytochrome c release and other apoptotic proteins and subsequent cell death by apoptosis [50, 145, 175]. Therefore, melatonin, through its antiapoptotic effects, may be particularly useful in treatment of this neurodegenerative disease.

Conclusion

Numerous studies have revealed that mitochondrial bioenergetic decay is an important contributing factor in aging and age-associated disorders, as well as in a variety of other pathophysiological situations such as heart ischemia/reperfusion, diabetes, various forms of hepatic disorders, neurodegenerative and cardiovascular diseases. Mitochondrial dysfunction, in particular defects in ETC activity, OXPHOS process and MPTP opening have all been suggested to play a critical role in the pathogenesis of these disorders. Multiple in vitro and in vivo studies have shown a beneficial effect of melatonin on mitochondria bioenergetics in a number of physiopathological conditions characterized by mitochondrial dysfunction. The beneficial effects of melatonin against aging and age-associated disorders, appear to be due to, at least in part, its ability to preserve mitochondrial function, through different mechanisms, including an antioxidant action on OXPHOS process and MPTP opening. There is large consensus in the literature on the involvement of CL in several mitochondrial bioenergetic processes, in mitochondrial stability, morphology and dynamics as well as in cell death. Cardiolipin alterations have been associated with mitochondrial dysfunction in numerous physiopathological conditions. The finding that melatonin prevents oxidative stress and ROS-induced CL abnormalities and, hence mitochondrial dysfunction, may have important implications in mitochondrial physiopathology (Fig. 3). Due to its multiple beneficial effects on mitochondrial metabolism and due to the lack of side effects, melatonin may represent an effective therapeutic agent to counteract mitochondrial dysfunction associated with aging and age-associated disorders.

References

- 1.Harman D. Aging: a theory based on free radical and radiation chemistry. J. Gerontol. 1956;11:298–300. doi: 10.1093/geronj/11.3.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harman D. The biologic clock: the mitochondria? J Am Geriatr Soc. 1972;20:145–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1972.tb00787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miquel J, Economos AC, Fleming J, et al. Mitochondrial role in cell aging. Exp Gerontol. 1980;15:575–591. doi: 10.1016/0531-5565(80)90010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pak JW, Herbst A, Bua E, et al. Mitochondrial DNA mutations as a fundamental mechanism in physiological declines associated with aging. Aging Cell. 2003;2:1–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1474-9728.2003.00034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wei YH. Mitochondrial DNA alterations as ageing-associated molecular events. Mutat Res. 1992;275:145–155. doi: 10.1016/0921-8734(92)90019-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richter C. Oxidative damage to mitochondrial DNA and its relationship to ageing. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1995;27:647–653. doi: 10.1016/1357-2725(95)00025-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Linnane AW, Marzuki S, Ozawa T, et al. Mitochondrial DNA mutations as an important contributor to ageing and degenerative diseases. Lancet. 1989;1:642–645. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(89)92145-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Judge S, Leeuwenburgh C. Cardiac mitochondrial bioenergetics, oxidative stress, and aging. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C1983–C1992. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00285.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sohal RS, Weindruch R. Oxidative stress, caloric restriction, and aging. Science. 1996;5:59–63. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5271.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beckman KB, Ames BN. The free radical theory of aging matures. Physiol Rev. 1998;78:547–581. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.2.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayakawa M, Hattori K, Sugiyama S, et al. Age-associated oxygen damage and mutations in mitochondrial DNA in human hearts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;189:979–985. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(92)92300-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paradies G, Ruggiero FM, Petrosillo G, et al. Age-dependent impairment of mitochondrial function in rat heart tissue: effect of pharmacological agents. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1996;786:252–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb39068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shigenaga MK, Hagen TM, Ames BN. Oxidative damage and mitochondrial decay in aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10771–10778. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.10771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lesnefsky EJ, Moghaddas S, Tandler B, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in cardiac disease: ischemia–reperfusion, aging, and heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33:1065–1089. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kauppila TE, Kauppila JH, Larsson NG. Mammalian mitochondria and aging: an update. Cell Metab. 2017;25:57–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramis MR, Esteban S, Miralles A, et al. Protective effects of melatonin and mitochondria-targeted antioxidants against oxidative stress: a review. Curr Med Chem. 2015;22:2690–2711. doi: 10.2174/0929867322666150619104143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gruber J, Fong S, Chen CB, et al. Mitochondria-targeted antioxidants and metabolic modulators as pharmacological interventions to slow ageing. Biotechnol Adv. 2013;31:563–592. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2012.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skulachev VP, Anisimov VN, Antonenko YN. An attempt to prevent senescence: a mitochondrial approach. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1787:437–461. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hardeland R, Pandi-Perumal SR, Cardinali DP. Melatonin. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;3:313–316. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tan DX, Manchester LC, Terron MP, et al. One molecule, many derivatives: a never-ending interaction of melatonin with reactive oxygen and nitrogen species? J Pineal Res. 2007;1:28–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2006.00407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tan DX, Reiter RJ, Manchester LC, et al. Chemical and physical properties and potential mechanisms: melatonin as a broad spectrum antioxidant and free radical scavenger. Curr Top Med Chem. 2002;2:181–197. doi: 10.2174/1568026023394443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reiter RJ, Paredes SD, Korkmaz A, et al. Melatonin combats molecular terrorism at the mitochondrial level. Interdiscip Toxicol. 2008;2:137–149. doi: 10.2478/v10102-010-0030-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reiter RJ, Mayo JC, Tan DX, et al. Melatonin as an antioxidant: under promises but over delivers. J Pineal Res. 2016;61:253–278. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Venegas C, García JA, Escames G, et al. Extrapineal melatonin: analysis of its subcellular distribution and daily fluctuations. J Pineal Res. 2012;52:217–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2011.00931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leon J, Acuña-Castroviejo D, Sainz RM, et al. Melatonin and mitochondrial function. Life Sci. 2004;7:765–790. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paradies G, Petrosillo G, Paradies V, et al. Melatonin, cardiolipin and mitochondrial bioenergetics in health and disease. J Pineal Res. 2010;48:297–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2010.00759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paradies G, Paradies V, Ruggiero FM, et al. Protective role of melatonin in mitochondrial dysfunction and related disorders. Arch Toxicol. 2015;89:923–939. doi: 10.1007/s00204-015-1475-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Acuña Castroviejo D, López LC, Escames G, et al. Melatonin–mitochondria interplay in health and disease. Curr Top Med Chem. 2011;11:221–240. doi: 10.2174/156802611794863517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manchester LC, Coto-Montes A, Boga JA, et al. Melatonin: an ancient molecule that makes oxygen metabolically tolerable. J Pineal Res. 2015;59:403–419. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tan DX, Manchester LC, Qin L, et al. Melatonin: a mitochondrial targeting molecule involving mitochondrial protection and dynamics. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:2124. doi: 10.3390/ijms17122124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Navarro-Alarcón M, Ruiz-Ojeda FJ, Blanca-Herrera RM, et al. Melatonin and metabolic regulation: a review. Food Funct. 2014;5:2806–2832. doi: 10.1039/C4FO00317A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hardeland R, Cardinali DP, Brown GM, et al. Melatonin and brain inflammaging. Prog Neurobiol. 2015;128:46–63. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dominguez-Rodriguez A, Abreu-Gonzalez P, Avanzas P. The role of melatonin in acute myocardial infarction. Front Biosci. 2012;17:2433–2441. doi: 10.2741/4063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Favero G, Franceschetti L, Buffoli B, et al. Melatonin: protection against age-related cardiac pathology. Ageing Res Rev. 2017;35:336–349. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2016.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang Y, Sun Y, Yi W, et al. A review of melatonin as a suitable antioxidant against myocardial ischemia–reperfusion injury and clinical heart diseases. J Pineal Res. 2014;57:357–366. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bondy SC, Sharman EH. Melatonin and the aging brain. Neurochem Int. 2007;50:571–580. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2006.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Escames G, López A, García JA, et al. The role of mitochondria in brain aging and the effects of melatonin. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2010;3:182–193. doi: 10.2174/157015910792246245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.García JJ, López-Pingarrón L, Almeida-Souza P, et al. Protective effects of melatonin in reducing oxidative stress and in preserving the fluidity of biological membranes: a review. J Pineal Res. 2014;56:225–237. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoch FL. Cardiolipins and biomembrane function. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1113:71–133. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(92)90035-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Houtkooper RH, Vaz FM. Cardiolipin, the heart of mitochondrial metabolism. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:2493–2506. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8030-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ren M, Phoon CK, Schlame M. Metabolism and function of mitochondrial cardiolipin. Prog Lipid Res. 2014;55:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paradies G, Paradies V, De Benedictis V, et al. Functional role of cardiolipin in mitochondrial bioenergetics. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1837:408–417. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Paradies G, Paradies V, Ruggiero, et al. Cardiolipin and mitochondrial function in health and disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;20:1925–1953. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kagan VE, Bayir HA, Belikova NA, Kapralov O, Tyurina YY, Tyurin VA, Jiang J, Stoyanovsky DA, Wipf P, Kochanek PM, Greenberger JS, Pitt B, Shvedova AA, Borisenko G. Cytochrome c/cardiolipin relations in mitochondria: a kiss of death. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;11:1439–1453. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Musatov A, Robinson NC. Susceptibility of mitochondrial electron-transport complexes to oxidative damage. Focus on cytochrome c oxidase. Free Radic Res. 2012;46:1313–1326. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2012.717273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mileykovskaya E, Dowhan W. Cardiolipin-dependent formation of mitochondrial respiratory supercomplexes. Chem Phys Lipids. 2014;179:42–48. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2013.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Claypool SM. Cardiolipin, a critical determinant of mitochondrial carrier protein assembly and function. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1788:2059–2068. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chicco AJ, Sparagna GC. Role of cardiolipin alterations in mitochondrial dysfunction and disease. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C33–C44. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00243.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Paradies G, Petrosillo G, Paradies, et al. Role of cardiolipin peroxidation and Ca2+ in mitochondrial dysfunction and disease. Cell Calcium. 2009;45:643–650. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2009.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Petrosillo G, Moro N, Ruggiero FM, et al. Melatonin inhibits cardiolipin peroxidation in mitochondria and prevents the mitochondrial permeability transition and cytochrome c release. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;47:969–974. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Petrosillo G, Fattoretti P, Matera M, et al. Melatonin prevents age-related mitochondrial dysfunction in rat brain via cardiolipin protection. Rejuvenation Res. 2008;11:935–943. doi: 10.1089/rej.2008.0772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boveris A, Chance B. The mitochondrial generation of hydrogen peroxide. General properties and effect of hyperbaric oxygen. Biochem J. 1973;134:707–716. doi: 10.1042/bj1340707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Murphy MP. How mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species. Biochem J. 2009;2009417:1–13. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Skulachev VP. Role of uncoupled and non-coupled oxidations in maintenance of safely low levels of oxygen and its one-electron reductants. Q Rev Biophys. 1996;29:169–202. doi: 10.1017/S0033583500005795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Giulivi C, Poderoso JJ, Boveris A. Production of nitric oxide by mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:11038–11043. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.18.11038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ghafourifar P, Richter C. Nitric oxide synthase activity in mitochondria. FEBS Lett. 1997;418:291–296. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(97)01397-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sarkela TM, Berthiaume J, Elfering S, et al. The modulation of oxygen radical production by nitric oxide in mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:6945–6949. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007625200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cleeter MW, Cooper JM, Darley-Usmar VM, et al. Reversible inhibition of cytochrome c oxidase, the terminal enzyme of the mitochondrial respiratory chain, by nitric oxide: implications for neurodegenerative diseases. FEBS Lett. 1994;345:50–54. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00424-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Levine RL, Stadtman ER. Oxidative modification of proteins during aging. Exp Gerontol. 2001;36:1495–1502. doi: 10.1016/S0531-5565(01)00135-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Urata Y, Honma S, Goto S, et al. Melatonin induces gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase mediated by activator protein-1 in human vascular endothelial cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;27:838–847. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(99)00131-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Reiter RJ, Tan DX, Osuna C, Gitto E. Actions of melatonin in the reduction of oxidative stress. A review. J Biomed Sci. 2000;7:444–458. doi: 10.1007/BF02253360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Barja G. Free radicals and aging. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:595–600. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Van Remmen H, Hamilton ML, Richardson A. Oxidative damage to DNA and aging. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2003;31:149–153. doi: 10.1097/00003677-200307000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stadtman ER. Importance of individuality in oxidative stress and aging. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;33:597–604. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(02)00904-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Van Remmen H, Richardson A. Oxidative damage to mitochondria and aging. Exp Gerontol. 2001;36:957–968. doi: 10.1016/S0531-5565(01)00093-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yan LJ, Levine RL, Sohal R. Oxidative damage during aging targets mitochondrial aconitase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:11168–11172. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pamplona R. Membrane phospholipids, lipoxidative damage and molecular integrity: a causal role in aging and longevity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1777:1249–1262. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Reiter RJ, Tan DX, Galano A. Melatonin: exceeding expectations. Physiology (Bethesda) 2014;29:325–333. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00011.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cuzzocrea S, Zingarelli B, Gilad E, et al. Protective effect of melatonin in carrageenan-induced models of local inflammation: relationship to its inhibitory effect on nitric oxide production and its peroxynitrite scavenging activity. J Pineal Res. 1997;23:106–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.1997.tb00342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Halladin NL, Ekeløf S, Jensen SE, et al. Melatonin does not affect oxidative/inflammatory biomarkers in a closed-chest porcine model of acute myocardial infarction. In Vivo. 2014;28:483–488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mauriz JL, Collado PS, Veneroso C, et al. A review of the molecular aspects of melatonin’s anti-inflammatory actions: recent insights and new perspectives. J Pineal Res. 2013;54:1–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2012.01014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Antolín I, Rodríguez C, Saínz RM, et al. Neurohormone melatonin prevents cell damage: effect on gene expression for antioxidant enzymes. FASEB J. 1996;10:882–890. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.10.8.8666165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Martín M, Macías M, Escames G, et al. Melatonin-induced increased activity of the respiratory chain complexes I and IV can prevent mitochondrial damage induced by ruthenium red in vivo. J Pineal Res. 2000;28:242–248. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-079X.2000.280407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.López A, García JA, Escames G, et al. Melatonin protects the mitochondria from oxidative damage reducing oxygen consumption, membrane potential, and superoxide anion production. J Pineal Res. 2009;46:188–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2008.00647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Reiter RJ, Tan DX, Galano A. Melatonin reduces lipid peroxidation and membrane viscosity. Front Physiol. 2014;5:377–380. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pieri C, Marra M, Gaspar R, et al. Melatonin protects LDL from oxidation but does not prevent the apolipoprotein derivatization. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;2:256–260. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Livrea MA, Tesoriere L, D’arpa D, et al. Reaction of melatonin with lipoperoxyl radicals in phospholipid bilayers. Free Radic Biol Med. 1997;5:706–711. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(97)00018-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pieri C, Marra M, Moroni F, et al. Melatonin: a peroxyl radical scavenger more effective than vitamin E. Life Sci. 1994;55:PL271–PL276. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(94)00666-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ceraulo L, Ferrugia M, Tesoriere L, et al. Interactions of melatonin with membrane models: portioning of melatonin in AOT and lecithin reversed micelles. J Pineal Res. 1999;26:108–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.1999.tb00570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Teixeira A, Morfim MP, de Cordova CA, et al. Melatonin protects against pro-oxidant enzymes and reduces lipid peroxidation in distinct membranes induced by the hydroxyl and ascorbyl radicals and by peroxynitrite. J Pineal Res. 2003;35:262–268. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-079X.2003.00085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Maharaj DS, Maharaj H, Daya S, et al. Melatonin and 6-hydroxymelatonin protect against iron-induced neurotoxicity. J Neurochem. 2006;1:78–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Parlakpinar H, Sahna E, Ozer MK, et al. Physiological and pharmacological concentrations of melatonin protect against cisplatin-induced acute renal injury. J Pineal Res. 2002;33:161–166. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-079X.2002.02910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Reiter RJ, Tan D, Kim SJ, et al. Augmentation of indices of oxidative damage in life-long melatonin-deficient rats. Mech Ageing Dev. 1999;110:157–173. doi: 10.1016/S0047-6374(99)00058-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hardeland R. Melatonin and the theories of aging: a critical appraisal of melatonin’s role in antiaging mechanisms. J Pineal Res. 2013;55:325–356. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tan DX, Manchester LC, Reiter RJ, et al. Melatonin directly scavenges hydrogen peroxide: a potentially new metabolic pathway of melatonin biotransformation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;29:1177–1185. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(00)00435-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tan DX, Manchester LC, Fuentes-Broto L, et al. Significance and application of melatonin in the regulation of brown adipose tissue metabolism: relation to human obesity. Obes Rev. 2011;12:167–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhang M, Mileykovskaya E, Dowhan W. Gluing the respiratory chain together. Cardiolipin is required for supercomplex formation in the inner mitochondrial membrane. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:43553–43556. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200551200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Schlame M, Ren M. The role of cardiolipin in the structural organization of mitochondrial membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1788:2080–2083. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Klingenberg M. Cardiolipin and mitochondrial carriers. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1788:2048–2058. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Schagger H. Respiratory chain supercomplexes of mitochondria and bacteria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1555:154–159. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2728(02)00271-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Duncan AL, Robinson AJ, Walker JE. Cardiolipin binds selectively but transiently to conserved lysine residues in the rotor of metazoan ATP synthases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:8687–8692. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1608396113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Gonzalvez F, Gottlieb E. Cardiolipin: setting the beat of apoptosis. Apoptosis. 2007;12:877–885. doi: 10.1007/s10495-007-0718-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ott M, Zhivotovsky B, Orrenius S. Role of cardiolipin in cytochrome c release from mitochondria. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:1243–1247. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Petrosillo G, Casanova G, Matera M, et al. Interaction of peroxidized cardiolipin with rat-heart mitochondrial membranes: induction of permeability transition and cytochrome c release. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:6311–6316. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ban T, Heymann JA, Song Z, et al. OPA1 disease alleles causing dominant optic atrophy have defects in cardiolipin-stimulated GTP hydrolysis and membrane tubulation. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:2113–2122. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Marom M, Safonov R, Amram S, et al. Interaction of the Tim44 C-terminal domain with negatively charged phospholipids. Biochemistry. 2009;48:11185–11195. doi: 10.1021/bi900998v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Xiao M, Zhong H, Xia L, et al. Pathophysiology of mitochondrial lipid oxidation: role of 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) and other bioactive lipids in mitochondria. Free Radic Biol Med. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.04.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hsu P, Shi Y. Regulation of autophagy by mitochondrial phospholipids in health and diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2017;1862:114–129. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2016.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Catalá A. The ability of melatonin to counteract lipid peroxidation in biological membranes. Curr Mol Med. 2007;7:638–649. doi: 10.2174/156652407782564444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Petrosillo G, Di Venosa N, Pistolese M, et al. Protective effect of melatonin against mitochondrial dysfunction associated with cardiac ischemia–reperfusion: role of cardiolipin. FASEB J. 2006;20:269–276. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4692com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mekhloufi J, Bonnefont-Rousselot D, et al. Antioxidant activity of melatonin and apinoline derivative on linoleate model system. J Pineal Res. 2005;39:27–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2005.00208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Navarro A, Boveris A. The mitochondrial energy transduction system and the aging process. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C670–C686. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00213.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Petrosillo G, De Benedictis V, Ruggiero FM, et al. Decline in cytochrome c oxidase activity in rat-brain mitochondria with aging. Role of peroxidized cardiolipin and beneficial effect of melatonin. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2013;45:431–440. doi: 10.1007/s10863-013-9505-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]