Abstract

Cardiomyocyte proliferation and regeneration are key to the functional recovery of myocardial tissue from injury. In the recent years, studies on cardiomyocyte proliferation overturned the traditional belief that adult cardiomyocytes permanently withdraw from the cell cycle activity. Hence, targeting cardiomyocyte proliferation is one of the potential therapeutic strategies for myocardial regeneration and repair. To achieve this, a deep understanding of the fundamental mechanisms involved in cardiomyocyte cell cycle as well as differences between neonatal and adult cardiomyocytes’ cell cycle activity is required. This review focuses on the recent progress in understanding of cardiomyocyte cell cycle activity at different life stages viz., gestation, birth, and adulthood. The temporal expression/activities of major cell cycle activators (cyclins and CDKs), inhibitors (p21, p27, p57, p16, and p18), and cell-cycle-associated proteins (Rb, p107, and p130) in cardiomyocytes during gestation and postnatal life are described in this review. The influence of different transcription factors and microRNAs on the expression of cell cycle proteins is demonstrated. This review also deals major pathways (PI3K/AKT, Wnt/β-catenin, and Hippo-YAP) associated with cardiomyocyte cell cycle progression. Furthermore, the postnatal alterations in structure and cellular events responsible for the loss of cell cycle activity are also illustrated.

Keywords: Cardiomyocytes, Cell cycle, Cyclins, Signaling pathways, MicroRNAs, Transcription factors

Introduction

Cardiomyocytes are vital for the heart function despite their numbers is lower than other types of cells in cardiac tissue. The loss of cardiomyocytes and its insufficient regeneration is the major contributor in the pathogenesis of many cardiovascular diseases, including myocardial infarction, cardiac fibrosis, and heart failure [1–3]. In fact, the injury induced adult myocardial tissue remodeling results from the lack of cardiomyocytes replenishment, while the neonatal and fetal myocardial tissues retain its contractile tissue from the proliferation of pre-existing cardiomyocytes [3]. This is mainly due to the fact that mammalian cardiomyocytes display distinct ways of growth during developmental stage and postnatal life [2, 3]. Undoubtedly, cardiomyocyte proliferation in a mammalian system is active during developmental stages and reduces at the early neonatal stage. Nevertheless, adult cardiomyocyte cell cycle entry and its proliferation are still in debate. Earlier studies with human heart samples showed an increase in DNA synthesis and nuclei number in the adult heart regardless of age, albeit the cell division being scarce [4, 5]. In the recent years, a growing number of evidence in human and other mammals support the self-renewal of adult cardiomyocytes [1, 2, 6–8]. In addition, the rate of cardiomyocyte proliferation is significantly higher after myocardial injury, especially in areas adjacent to the injury [8]. In small rodents, such as mice, cardiomyocytes replenish at a rate of 1.3–4 % per year, mainly through the activation of resident cardiomyocyte proliferation [9]. Likewise, many research groups observed self-renewal of cardiomyocytes in the adult human heart. However, the proliferation rate differently reported ranging from 1 to 40 % per year [1, 2, 6, 10]. This wide variation is due to techniques and parameters used to evaluate cardiomyocyte proliferation in human hearts. Despite the variable degree of cardiomyocyte renewal rate observed, these studies emphasize the re-entry of adult cardiomyocytes in cell cycle and its proliferative capacity. Unlike mammals, certain fishes, reptiles, and amphibians maintain the regenerative ability throughout the life, even at large cardiac defects. This renewal is mainly achieved by the proliferation of pre-existing/survived cardiomyocytes [3, 11]. The viable difference between the ability and inability of productive heart regeneration depends on the capability of cardiomyocyte to acquire its proliferative state. In this review, we discuss the activities of major cell-cycle-associated proteins in cardiomyocytes at different stages of the heart development and the mechanisms of cardiomyocyte cell proliferation and its regulations before and after birth.

Cardiomyocytes proliferation and heart development

The heart is a first organ, which begins its function early from embryonic stage. Therefore, normal morphogenesis is essential for a proper functioning of the heart throughout the life. The growth pattern of cardiomyocyte is vital for the formation of normal structure, appropriate size, and function of the heart [12, 13]. The mesodermal layer is the origin of the heart in the embryo. The cardiogenic mesodermal cells form two major progenitor pools at the anterior part of the embryo. This primitive heart streak is called first (or cardiac crescent) and second heart fields that are precursors for cardiomyocytes. The regional patterning of specific signaling in cardiac crescent determines the specification of cardiac cells. Multiple growth factors and transcription factors work in a concert of initial cardiomyocyte lineage determination and subsequent differentiation of cardiomyocytes [14]. In the developing heart, the spatiotemporal growth and assembly of embryonic cardiomyocytes are vital for the cardiac chamber maturation, a process which includes three important interrelated events, such as the formation of myocardial projection (trabeculae formation), establishment of the conducting system, and compaction of myocardium [15, 16]. A high rate of cell cycle activity has been observed in ventricular cardiomyocytes during the early stage of cardiomyogenesis as well as during the compaction of the myocardium [17]. This indicates that the rhythm of cardiomyocyte proliferation is essential for sculpting the structure of heart. It is well known that proliferative pulse is distinct between species, which is likely to be the primary basis for the variation in heart size and structure among different species. During the developmental period, cardiomyocytes have the ability to undergo DNA synthesis and cytokinesis, which results in an increase of cardiomyocytes population. In contrast, postnatal heart growth occurs primarily by non-mitotic growth and hypertrophic growth, a process in which cardiomyocytes increase its DNA content and size without an increase in its numbers [18, 19]. The non-mitotic cell cycle also produces multinucleated or polyploidy cells. Thus, the cell cycle activity is not only required for cell division, but also involved in hypertrophic growth, polyploidy, and multinucleation.

Cell cycle in cardiomyocytes proliferation and growth

The distinct activity of the mammalian cardiomyocyte cell cycle is the root cause of the variation in growth pattern of cardiomyocytes before and after birth [18, 20]. The cell proliferation is controlled by the activation of two classes of proteins called cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs). These two families of proteins coordinate and form complexes that precede DNA synthesis and cell division. These complexes are regulated by two families of CDK inhibitors (INK4 family and CIP/KIP family). These inhibitors regulate the cell cycle activity by binding to CDKs and inactivating cyclin-CDK complexes. The CIP/KIP family members (p21, p27, and p57) regulate a wide range of CDKs, while the INK4 family members (p16, p15, p18, and p19) specifically target CDK4/6 activity [18, 20, 21]. The upregulation of these CDK inhibitors co-operatively blocks the regulators (CDK2, 4, and 6) of G1/S and G2/M checkpoints and arrests the cell cycle activity [18, 20, 21]. The CDK inhibitors also play a key role in cardiomyocyte differentiation. In general, there is an inverse relationship between proliferation and differentiation. However, both proliferation and terminal differentiation (maturation) require cell cycle activity. This phase is characterized by harmonized changes in the expression of many cell cycle molecules, such as increased levels of cell cycle inhibitors (p21, p27, Rb, Meis1, and p130) [21–23] and decreased expression of cell cycle activators (Cyclins, CDKs, and co-factors) [21, 24].

Cyclins and CDKs

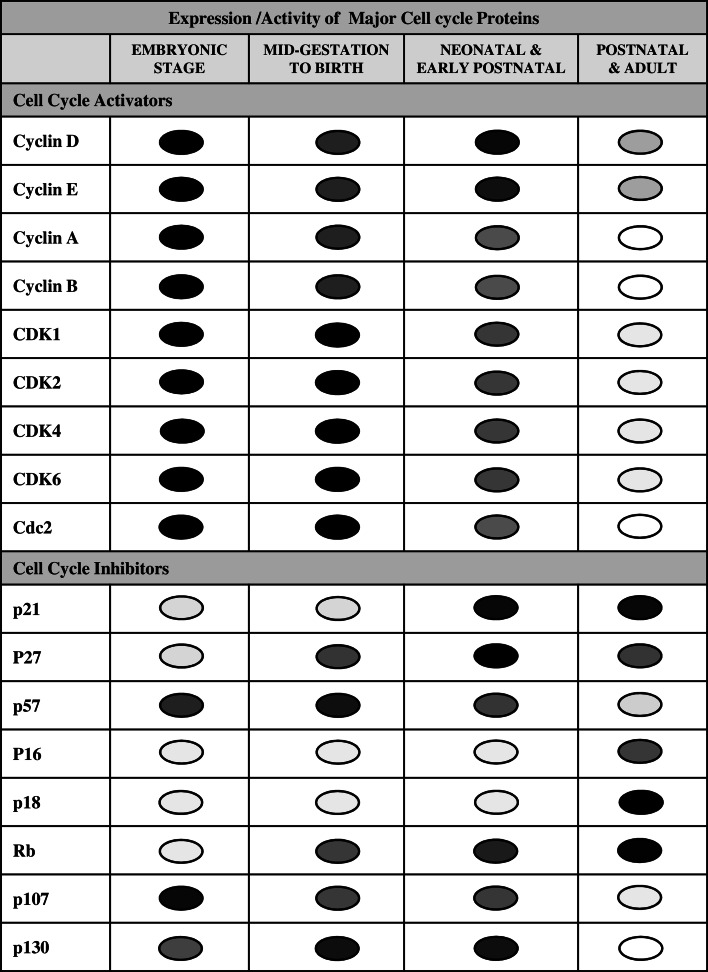

Cyclins and CDKs are positive modulators of cell cycle progression, and their increase serves as an index of mitotic events in all the types of cells. The D-type cyclins and its partners are important regulators of cell cycle entry. Molecular studies found that the nuclear entry and binding of cyclins D1 and D2 with CDK4 are essential for cardiomyocyte proliferation. However, these two isoforms of cyclin D have differential binding affinity for CDK4. The impairment of cyclin D1 nuclear import in terminally differentiated cardiomyocyte partly contributes to withdrawal from the cell cycle [24–26]. In embryonic stage, the expression and activity of some important cyclin-CDK complexes, such as cyclin D-CDK4/6, cyclin E-CDK2, cyclin A-CDK1/2, and cyclin B-CDK1, are remarkably high in cardiomyocytes. However, their activities are relatively reduced from mid-gestation period to birth, and then, a wave of increased activity can be seen in early postnatal life that largely results in the development of binucleated and multinucleated cells (Fig. 1) [18, 27, 28].

Fig. 1.

Diagrammatic representation of temporal expression/activity of cell cycle proteins in cardiomyocytes at different stages of heart development. The circles with different shades indicate the expression and activity of different cell cycle proteins. Dark shade

indicates higher expression and activity. Lighter shades

indicates higher expression and activity. Lighter shades

indicate comparatively decreased/lower activity. Empty circles

indicate comparatively decreased/lower activity. Empty circles

indicate barely detectable or undetectable. CDK cyclin-dependent kinase, CDC cell division cycle protein, Rb retinoblastoma

indicate barely detectable or undetectable. CDK cyclin-dependent kinase, CDC cell division cycle protein, Rb retinoblastoma

The expression/activity pattern of cyclin-CDK complexes in cardiomyocytes is universal in the majority of the mammalians and a slight variation in their levels observed in different species. A very high level of cyclins and CDKs was observed in human atrial tissue during the gestation period, but their levels reduced differentially during the adult stage. The levels of cyclin D1, cyclin D3, CDK2, and CDK6 were detectable in adult atria, but their levels were extremely low when compared to gestational heart atria. Other cyclins, such as cyclin E, cyclin A, cyclin B, and cdc2, were undetectable, while there was no change in the activity of CDK4 from the fetal stage to adult period [28]. A detailed study in rats by Kang et al. explains the temporal pattern of different cyclin and CDK activities in cardiomyocytes. The G2–M-phase cyclins (cyclins A and B) are detectable in embryonic and neonatal cardiomyocytes, but they disappear in young and adult hearts. The mRNA levels of G1–S-phase cyclins (cyclins D1, D2, D3, and E) are high throughout all the stages of the heart development, but the protein levels of cyclins D1, D3, and E variably decrease at the young age. Interestingly, the levels of CDKs (CDK2, CDK4, and cdc2) are high during embryonic heart development and remain constant during the neonatal period, but their expression/activities are very low at young and adult stages [27]. Ikenishi et al. observed a similar pattern of the expression of these cyclins and CDKs in mouse heart [18]. Collectively, these studies reveal that there is a variation in the expression of cyclins and CDKs in cardiomyocytes at different development stages.

CDK inhibitors

CDK inhibitors p21, p27, and p57 are important regulators of cardiomyocyte cell cycle activities. In general, the expression and activities of CDK inhibitors are lower in fetal and neonatal cardiomyocytes. The levels of p21 and p27 increase in maturing cardiomyocytes, and their expressions are persistent in adult cardiomyocytes [18, 20, 21]. A gene knockout study in mice confirmed that p21 and p27 are important partners in mammalian cardiomyocyte cell cycle exit after birth [21]. p21 and p27 coordinately force the cell cycle exit by blocking all the phases of the cell cycle. Both p21 and p27 inhibit G1 phase entry, while p21 plays a crucial role in the inhibition of M-phase entry [20, 21, 29]. A study in adult cardiomyocytes found that p21 blocks S-phase entry and DNA replication by promoting the degradation of proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) [30]. Notably, p57 does not take part in these processes. Unlike p21 and p27, p57 is expressed in the fetal heart and its activity appears to be more related to cell differentiation. During mid-gestation, p57 is selectively expressed by cardiomyocytes residing in the inner trabecular layer and their upregulation is highly associated with lower proliferation of cardiomyocytes and structural differentiation of the trabecular layer [31].

These CIP/KIP family members exhibit different roles in adult cardiomyocyte. Overexpression of p21 and p27 protects cardiomyocyte from hypoxia-induced cell death, and this protection is independent of CDK inhibition activity [32]. Similarly, forced expression of p57 attenuates hypoxia-ischemic injury in the adult mouse heart [33]. Interestingly, Haley et al. found a persistent DNA synthesis and active proliferation of p57 over-expressing cardiomyocytes, which indicate that cell cycle activity of cardiomyocyte remains unaffected by the expression of p57. This study also reveals that p57-mediated terminal differentiation of cardiomyocyte is not necessarily required the cell cycle exit [33]. The role of INK4 family members (p16, p15, p18, and p19) in cardiomyocyte cell cycle regulation is less clear. In contrast to CIP/KIP family, INK4 family members appear mostly in adult cardiomyocytes, in which they maintain a quiescent state as well as involved in the induction of hypertrophic response. INK4 family-mediated inhibition of cell cycle progression targets the activation of responsive retinoblastoma (Rb) proteins [18, 29] (Fig. 1).

Cell-cycle-associated proteins and transcription factors in cardiomyocyte proliferation

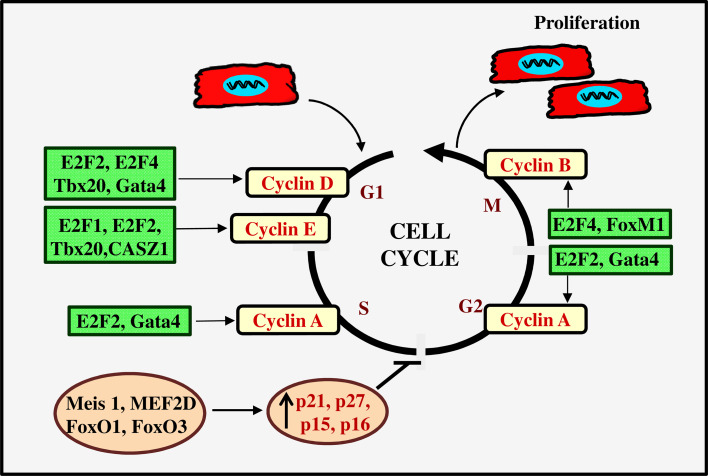

The cardiomyocyte cell cycle is tightly regulated by a complex network of transcription factors and proteins, which either positively or negatively regulate the expression of cell cycle proteins (Fig. 2). However, the mechanisms by which these molecules rapidly decline/appear after birth and the maintenance of cell cycle exit are yet largely unknown. The pocket proteins, retinoblastoma (Rb), p107, and p130, are variably expressed in cardiomyocytes before and after birth. During developmental stage, these proteins are essential for the regulation of growth of the trabecular myocardium and ventricular conduction system [23, 34]. In cardiomyocytes, Rb expression increases during the late gestation and the postnatal period, while p107 and p130 are highly expressed during gestation and barely detectable in the adult stage. Rb plays a vital role in cell cycle exit and differentiation of cardiomyocyte [35]. During cell cycle progression, CDK2 and CDK4 mediate hyper-phosphorylation of Rb family members, thereby blocking Rb proteins from binding with E2F transcription factors. This results in active transcription of genes involved in cell cycle progression [23, 32]. Recent studies found that Rb and p130 have overlapping roles in maintaining the post-mitotic state of adult cardiomyocyte. They interact with heterochromatin protein 1-γ (HP1-γ) to silent many proliferation-promoting genes [23, 34]. A recent study showed that down syndrome-associated dual-specificity tyrosine-(Y)-phosphorylation-regulated kinase 1A (DYRK1A), a protein kinase, positively regulates Rb signaling by inhibiting cyclin D-mediated inhibition of Rb in cardiomyocytes. The increased expression of DYRK1 leads to the activation (hypo-phosphorylation) of Rb and, consequently, suppresses E2F-targeted cell cycle gene expression. This indicates that DYRK1 could be a critical factor in cardiomyocyte cell cycle entry [36].

Fig. 2.

Transcription factors involved in regulation of cardiomyocyte cell cycle activity. The transcription factors, such as E2F1, E2F2, E2F4, CASZ1, GATAT4, Tbx20, and FoxM1, positively regulate cell cycle by the increasing expression of cyclins. E2F transcription factors promote the cell cycle progression by increasing expression of cyclin D, E, A, and B. Tbx20 promotes cell cycle by increasing the expression of both G1/S and G2/M cyclins (cyclins D, E and A). GATA4 upregulates cyclin D and cyclin A expression and it contributes to G1/S-phase transition. FoxM1 acts as a mitosis inducing factor by increasing expression of cyclin B. The transcription factors, such as Meis1, MEF2D, FoxO1, and FoxO3, inhibit cell cycle progression by increasing the expression of p21, p27, p15, and p16

The E2F family of transcription factors plays a fundamental role in proliferation by regulating the expression of many cell cycle genes. Among seven members of E2F family, E2F1, E2F2, E2F3, and E2F4 involve cell cycle progression and DNA synthesis in neonatal cardiomyocytes. Although all these E2Fs promote S-phase entry and DNA synthesis, only E2F1 and E2F2 can promote mitotic cell division by increasing the expression of cyclins B1 and B2 in cardiomyocyte. Interestingly, increased expressions of these two E2Fs provoke binucleation in neonatal cardiomyocytes [37]. In particular, E2F2 appears to increase the expression of cyclins D1, A, E, and B. However, it does not affect the level of CDK inhibitors [37–39]. The proliferating cardiomyocytes required nuclear expression of E2F4 for progression to mitotic phase. In proliferating cells, E2F4 is expressed in the nucleus at the end of S phase, and moves to chromosomes during G2/M phase and disappears at the end of cytokinesis [39]. Although E2F1 and E2F3 promote cell cycle entry and S-phase progression, these E2Fs strongly activate the transcription of several pro-apoptotic genes, such as p21CIP/WAF and p19ARF in cardiomyocyte. Surprisingly, E2F2 and E2F4 can mitigate the apoptotic response elicited by E2F1 and E2F3 [37, 40]. These studies reveal that balancing in these divergent siblings is an important deciding factor in cardiomyocyte proliferation, binucleation, and survival. It is well known that Rb family proteins regulate E2F family of transcription factors. Interestingly, p107 interacts with E2F in fetal cardiomyocytes to regulate the DNA synthesis, but in the neonatal stage, E2F primarily interacts with p130 and to a lesser extent with Rb [41]. Although adult cardiomyocytes can express E2F transcription factors, the inability of adult cardiomyocyte proliferation is due to the suppression of E2F-dependent cell cycle genes, in particular, G2/M phase and cytokinesis genes. Currently, the factors associated with silencing of these genes are largely unknown. It is believed that epigenetic modifications, such as histone methylation, could be responsible for the inaccessibility of transcription machinery, which is a universal mechanism of stable transcription silencing in eukaryotic cells [23].

The transcription factor of the T-box family, Tbx20, plays an essential role in promoting cardiomyocyte proliferation in prenatal heart and cardiac homeostasis in adults. Tbx20 shows distinct functions in embryonic and fetal hearts by differentially regulating cardiac lineage specification and cell proliferation of cardiomyocytes [42, 43]. A recent study identified that Tbx20 increases cyclin D1 and E1 expressions while decreasing the cell cycle negative regulators, such as p21 in cardiomyocytes. In addition, Tbx20 directly binds to the gene region of B-cell translocation gene 2 (Btg2), a negative regulator of cell-cycle, and represses its expression in neonatal cardiomyocyte [44]. This is achieved by the activation of multiple signaling pathways, including AKT-GSK3β-βcatenin, BMP2-pSmad1/5/8, and Yes-Associated Protein (YAP)-signaling pathways [43, 44]. Notably, Tbx20 suppresses Meis1, a member of the TALE homeodomain transcription factors, to promote cardiomyocyte proliferation [44]. Meis1 was identified as an important regulator of postnatal cardiomyocyte cell cycle exit. The expression of Meis1, predominantly, Meis1B isoform, is upregulated in cardiomyocytes soon after birth and it implements the cell cycle arrest by inducing the expression of several CDK inhibitors, such as p15, p16, and p21 [22]. A study with Meis1 knockout mice found that the silencing of Meis1 resurges cardiomyocyte proliferation by the activation of mitosis in the injured adult heart without inducing hypertrophy or reducing cardiac function. This observation revealed that Meis1 activity and expression are crucial for mitotic phase blockage and multinucleation in adult cardiomyocytes [22]. Together, these studies provided Tbx20-Meis1, a transcription axis, as a potential target to trigger cardiomyocyte proliferation and improve cardiac function in the injured heart.

The zinc finger family of transcription factors, such as GATA4 and castor zinc finger (CASZ1), also important contributors in cardiac morphogenesis as well as cardiomyocyte proliferation [45, 46]. GATA4 is one of the earliest genes expressed in the cardiac crescent. GATA4 is essential for the expression of many cardiac transcription factor genes, including Mef2c, Hand2, and Nkx2-5, which are involved in cardiomyocyte specification. The gain and loss of function studies in mice found that GATA4 is an integral member of cardiomyocyte cell cycle, which induce the expression of several cell cycle genes, such as cyclin D2, cyclin A2, and CDK4 [46]. Interestingly, cyclin D2 acts as a cofactor in GATA4-dependent transcriptional activities during cardiomyocyte proliferation [47]. In embryo stage, CASZ1 is required for cardiomyocyte cell cycle progression in both the first and second heart fields. CASZ1 promotes the cell cycle progression from G1 to S phases, and its loss leads to reduction in DNA synthesis. In addition, CASZ1 promotes cytokinesis and cell division by upregulating the expression of cyclin B1, which is an important mitotic phase cyclin [45].

The member of myocyte-specific enhancer factor 2 (MEF2) family of transcription factor, MEF2D, is a key transcription mediator of pathological remodeling in the adult heart. A genome-wide transcriptome analysis found that MEF2D impairs cardiomyocyte cell cycle by increasing the expression of PTEN, a negative regulator of PI3K/AKT pathway. However, prolonged deficiency of MEF2D triggers cell death in neonatal cardiomyocytes, which reveals the critical role of MEF2D in cardiomyocyte cell cycle [48]. The Fork head box (Fox) family transcription factors have also been implicated in cardiomyocyte cell cycle. A balanced function of FoxM1 and FoxOs (FoxO1 and FoxO3) is required for the proper growth of cardiomyocytes and cardiac development. The expression of FoxM1 is downregulated at birth and it becomes undetectable in cardiomyocytes of the adult heart. In the prenatal heart, FoxM1 promotes cardiomyocyte cell cycle, while FoxO1 and FoxO3 have a negative role in proliferation of cardiomyocytes [49]. These two FoxOs inhibit cell cycle in neonatal cardiomyocytes by upregulating the expression of p21 and p27, while they promote survival in adult cardiomyocytes. Molecular studies found that insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1) and AMPK signaling are common targets of these FoxO proteins [49]. The mitogenic receptors (FGFR and IGFR) mediated the activation of PI3K/AKT pathway phosphorylates FOXO (inactivation) to downregulate the expression of p21 and p27 in proliferating cardiomyocytes [50]. Thus, the transcriptional regulatory network has multifaceted role in regulating cardiomyocyte cell cycle activities beginning from cardiac development to myocardial injury in the adult stage.

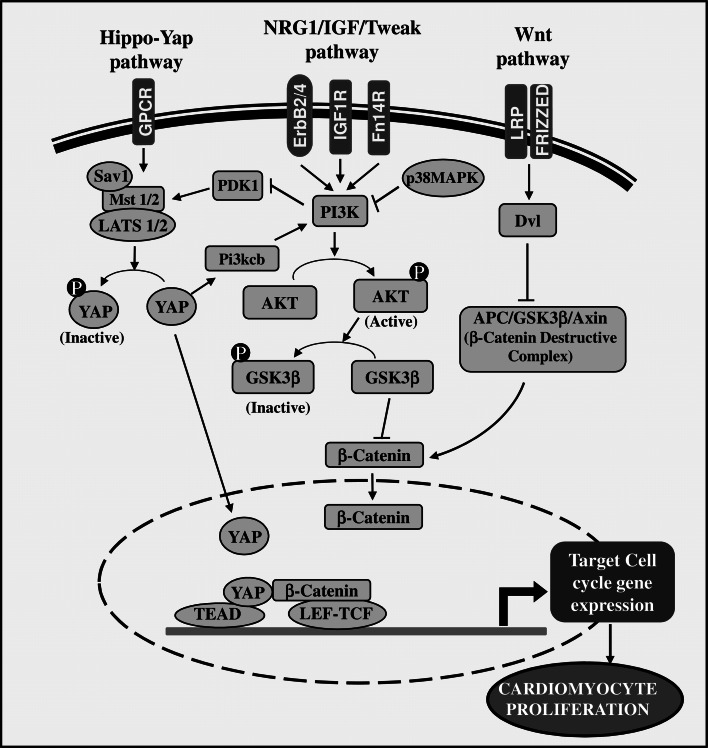

Signaling pathways associated with cardiomyocyte proliferation

The advancement in techniques and experimental methods in the last two decades has uncovered many molecular events and signaling pathways in cardiomyocyte cell cycle activation or prevention [50–54]. The majority of proliferation stimulators activate PI3K-AKT, Wnt/β-catenin, and YAP pathways. These pathways act as a central effector signaling in cardiomyocyte proliferation, although they have different upstream activators [51, 53–56]. The recently defined Hippo-YAP signaling plays a vital role in controlling cardiomyocytes growth and heart size [57]. Growing evidences indicate that YAP signaling not only interacts with Wnt/β-catenin signaling, but also with PI3K-AKT signaling. This interaction positively regulates cardiomyocyte cell cycle progression [56, 58]. Interestingly, YAP activates PI3K-AKT pathway by directly targeting the expression of Pik3cb, a catalytic submit of PI3K, to promote cardiomyocyte proliferation [56]. The cell surface tyrosine kinases, such as epidermal growth factor receptors (ErbB2 and ErbB4) and IGFR, play a central role in the activation of YAP and PI3K-AKT signaling during cardiomyocyte cell cycle and cardiac regeneration [58–60]. The mitogenic receptors, such as EGF receptor, induce YAP nuclear accumulation by PI3K-dependent blockage of YAP phosphorylation. The phosphoinositide-dependent kinase (PDK1) associates with hippo core complexes (Mst-Sav-LATS1/2), which is essential for the YAP phosphorylation and inactivation. EGFR-mediated activation of PI3K recruits PDK1 to the plasma membrane, where it binds with PtdIns (3,4,5)P3. This leads to the dissociation of Mst-Sav-LATS1/2 complex and inactivation of LATS1/2, which in turn switch on YAP activity [61] (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Major pathways involved in cardiomyocyte proliferation. The proliferation stimuli activates mitogenic receptors (ErbB2, ErbB4, IGF1R, fibroblast growth factor inducible molecule 14 receptor (FN14R), etc.) and its cytoplasmic signaling, such as PI3K-AKT, Wnt/β-catenin, and YAP. Wnt and PI3K-AKT pathways directly promote β-catenin nuclear translocation by inhibiting GsK3β, which blocks β-catenin activity by increasing its phosphorylation and degradation. Wnt and Frizzled receptors classically activate disheveled (Dvl) protein to block β-catenin destructive complex. The nuclear β-catenin binds with LEF/TCF transcription factors and this complex upregulates expression of various cell cycle genes. YAP is a positive regulator of many cell cycle genes expression. Non-phosphorylated form of YAP (active) translocates to the nucleus and binds with TEAD to activate cell cycle gene expression. YAP and PI3K-AKT pathway are interconnected. YAP directly upregulates PI3K-AKT pathway by increasing the expression of catalytic submit of PI3K (Pi3kcb), and thereby it indirectly promotes β-catenin activity. In addition, YAP interacts with β-catenin in the nucleus and enhances its transcriptional activity. In contrast, p38MAPK activation inhibits PI3K-AKT pathway to turn off cell cycle progression. GPCR-activated Hippo kinases (Mst1/2, Sav1, and LATS1/2) regulate (switch off) YAP activity by phosphorylation. The growth-factor-dependent activation of PI3K stimulates the dissociation of PDK1 from hippokinase complex (Mst1/2-Sav1-LATS1/2), which leads to the dispersing of YAP inactivation complex and turns on YAP signaling

Notch pathway also plays a key role in stimulating mammalian cardiomyocyte proliferation during development and in the early postnatal life. Notch induces RBP-JKappa-dependent expression of cyclin D1 and its nuclear localization, which is essential for its cell cycle activity [62]. However, the activity of Notch signaling pathway is downregulated in adult cardiomyocytes. The forced activation of Notch signaling only triggers the DNA damage checkpoints and imposes G2/M interphase arrest. This is mainly due to irreversible epigenetic modifications, such as cytosine-guanine dinucleotide (CpG) DNA methylation of Notch-responsive promoters as well as repressive chromatin environment [63]. In contrast to these pathways, mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) have a negative effect on cardiomyocyte cell proliferation. In fact, this signaling pathway elicits the pathological hypertrophic response and mitosis inhibition in cardiomyocyte by suppressing the expression of cdc2, cyclin A, cyclin B, and cyclin D [64, 65]. Among these cell cycle proteins, the down regulation of cyclins A and B facilitates cell cycle exit without cytokinesis. In addition, the upregulation of p38MAPK inhibits PI3K-AKT pathway, which is involved in the expression of many cell cycle genes in cardiomyocytes [64]. In contrast to this, Ras-induced activation of ERK1/2 increases the expression of G1/S cyclins (cyclin B1 and D1) without altering cyclins A and E. However, it inactivates cdc2 by phosphorylation at Tyr15. It is well known that cyclin B-cdc2 complex is obligatory in the mitotic phase to complete cell cycle, but Tyr15 phosphorylation inhibits cdc2 binding with cyclin B, which is accompanied by elevated levels of p21, p27, and p57 [65]. These studies indicate that MAPK signals assist cardiomyocyte cell cycle reactivation, but its negative effect on the cytokinesis phase leads to incomplete cell cycle and hypertrophic growth. Nevertheless, the interesting phenomenon is the majority of pathways stimulate proliferation in fetal and neonatal cardiomyocytes, but they increase hypertrophic growth in the adult heart. This discrepancy needs to be further evaluated and addressed.

Numerous molecules can force re-entry of cell cycle entry and DNA synthesis in adult cardiomyocytes; however, the majority of them turn on hypertrophic growth in the injured heart. Very few growth factors, such as TNF-related weak inducer of apoptosis (TWEAK) [53], insulin-like growth factor (IGF1), fibroblast growth factor 1 (FGF1) [54], and neuregulin 1 (NRG1) [51], efficiently promote cardiomyocyte proliferation. These molecules stimulate cell cycle entry, DNA synthesis, and cytokinesis in cardiomyocytes by the activation of PI3K-AKT, Wnt/β-catenin, and YAP pathways. Under experimental conditions, these growth factors increased cardiomyocyte numbers and improved cardiac tissue function following pathological injury [51, 53, 54]. Among these molecules, NRG1 is the most promising one in promoting cardiac repair and regeneration following cardiac injury under experimental conditions as well as in clinical trials [66–68]. The therapeutic benefits of NRG1 primarily rely on the induction of cardiomyocyte proliferation, cardiomyogenesis, and inhibition of cardiomyocyte apoptosis. Administration of NRG1 stimulates adult cardiomyocyte cell cycle re-entry and division by triggering ErbB2/ErbB4-dependent activation of PI3K-AKT and YAP-signaling pathways [51, 56, 59]. Interestingly, NRG1 administration does not provoke hypertrophic response in cardiomyocytes. Therefore, extrinsic stimulation with these factors could enhance the proliferation of differentiated cardiomyocytes and boost up cardiac repair. However, further detailed investigation of signaling mechanisms of these molecules is not only required for understanding its mechanism of action, but also for efficient and safe therapy in heart failure patients.

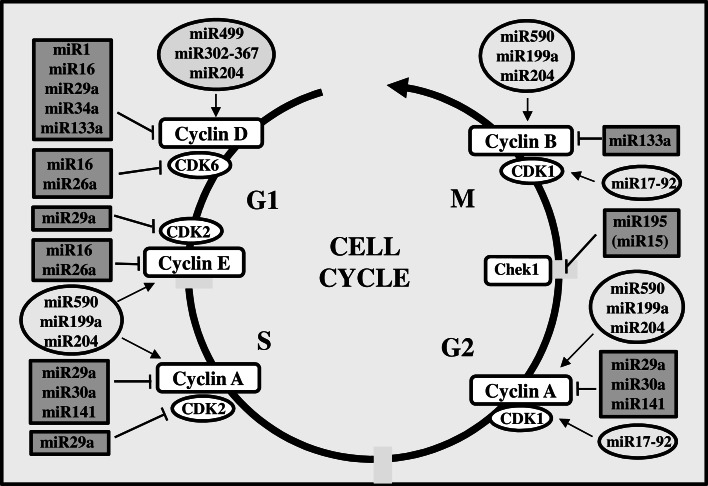

MicroRNAs in cardiomyocyte proliferation

Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) are the transcripts of non-protein coding region of the genome. ncRNAs play a crucial role in regulating the cardiac development and remodeling by controlling gene expression at epigenetic, transcriptional, and post-transcriptional levels. The small ncRNAs, particularly, microRNAs (miRNAs) have been studied extensively for their functional importance in the normal heart development and functions [69]. They play a central role in deciding cardiomyocyte proliferation and maturation (Fig. 4). A high throughput functional screening identified that about 204 miRNAs can promote neonatal cardiomyocyte proliferation, while 331 miRNAs can decrease cardiomyocyte proliferation without affecting the cell survival. Among these, 40 miRNAs were found to play essential role in DNA duplication and cytokinesis [69]. The gain and loss of function studies using experimental animal models revealed that miRNAs, such as miR-1, miR16, miR-29 family, miR-99 family, miR-133 family, and miR-195, are important regulators of various cell cycle protein expressions in cardiomyocytes of developing heart. The miRNA clusters of miR-17-92 and miR302-367 were found to be involved in cardiomyocyte proliferation in embryonic and postnatal heart [70, 71]. Importantly, miR-17-92 promotes adult cardiomyocyte proliferation by increasing the expression of CDK1, which is essential for cell division. This upregulation is associated with the inhibition of phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), which is an inhibitor of PI3K-AKT activity, a prominent signaling pathway in cardiomyocyte proliferation. miR302-367 improves cardiac function as well as increases cardiomyocyte proliferation by promoting cyclin D expression through targeting Hippo pathway [70, 71]. miR499 also increases cyclin D expression by an unknown pathway [72]. Some miRNAs, such as miR204, miR590-3p, and miR199a-3p, can increase the expression of cyclins A, E, and B in proliferating cardiomyocytes [69, 73]. Thus, they contribute to the progression of all the phases of the cell cycle. miR204 targets jumonji-AT rich interactive domain 2 (Jarid2), a transcription repressor, to upregulate the expression of cell cycle proteins. miR204-dependent regulation of Jarid2 in cardiomyocyte is essential during embryo development and cardiogenesis [73]. In fact, nuclear Jarid2 interacts with SETDB1, a histone methyl transferases, to downregulate the expression of Notch 1 [74], which can lead to the suppression of cyclin D1. Similarly, MEF2A-regulated expression of miR410 and miR495 stimulates DNA synthesis and proliferation in cardiomyocyte by suppressing Cited2-dependent expression of p57Kip2, a cell cycle inhibitor blocks G1 phase cyclin-CDK complexes [75].

Fig. 4.

MicroRNAs in cardiomyocyte cell cycle proteins expression. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are differentially expressed by cardiomyocytes during fetal and postnatal heart development. Among the cell-cycle-associated miRNAs, miR499, miR302-367, miR590, miR199a, miR204, and miR17-29 positively regulate cardiomyocyte cell cycle, while miR1, miR15, miR16, miR26a, miR29a, miR30a, 34a, miR133a, and miR141 negatively regulate cell cycle by modulating the expression of different cyclins (cyclins D, E, A, and B) and cyclin-dependent kinases (CDK1, 2, and 6). In contrast to all these miRNAs, miR195 blocks G2/M transition by inhibiting the expression of chek1

Several classes of miRNAs negatively regulate cardiomyocyte proliferation by directly or indirectly downregulating expression of one or more cell cycle activators. The miR15 family can suppress heart regeneration by its repressing effect on postnatal cardiomyocyte proliferation [76]. A member of the miR15 family, miR195 arrests cell cycle by targeting expression of checkpoint kinase 1 (Chek1), a protein kinase which promotes G2/M transition and mitotic progression. miR16 is another member of miR15 family, which downregulates the expression of multiple cycle proteins (cyclin D, cyclin E, and CDK6) to impose the shutdown of cell cycle activity [77]. Similarly, miR29a imposes cell cycle arrest by suppressing the expression of cyclin D, cyclin A, and CDK2 [78, 79], whereas miR26a downregulates cyclin E and CDK6 [80]. miR133a reduces cardiomyocyte proliferation by blocking the expression of cyclin D and cyclin B [81]. The increased expression of miR499 [72] and miR34a [82] leads to the suppression of cyclin D, while miR30a and miR141 abrogate the expression of cyclin A to block cell cycle progression [79]. Collectively, these studies infer that the cell cycle activity in cardiomyocyte is tightly controlled by microRNAs. The counterbalance in the expression of miRNAs is a critical factor to switch on different phases of cell cycle in cardiomyocytes. A fall in this balance leads to incomplete cell cycle during postnatal heart development as well as cardiac regeneration, which results in binucleation, polyploidization, and/or hypertrophic growth [76–78].

Adult cardiomyocyte cell cycle and growth

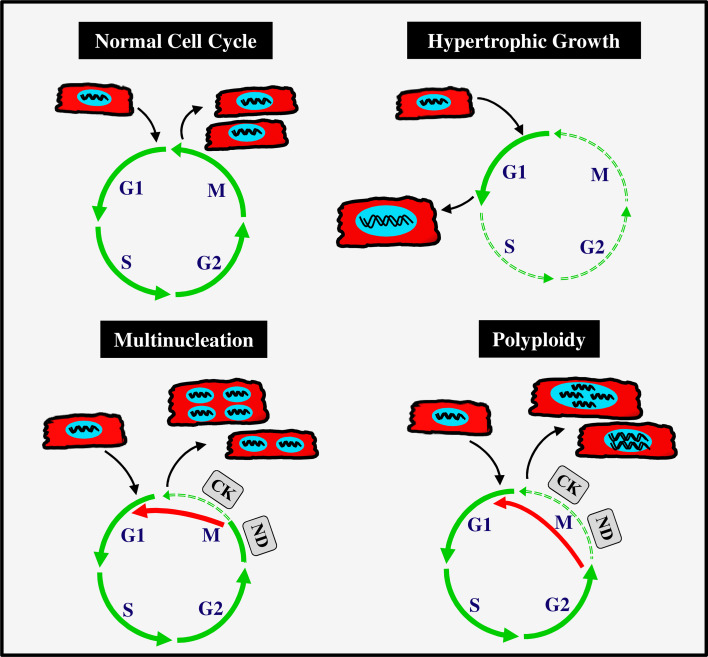

In general, the growth of postnatal heart occurs mainly by gradual enlargement of terminally differentiated cardiomyocytes (both mono-nucleated and binucleated) through hypertrophic process. Increasing evidences disclose that the prolonged activity of certain cell cycle machineries (e.g., cyclins D1, D2, and D3) and/or down regulation of mitotic cyclins and CDKs (e.g., cyclins A and B) are responsible for an increase in cell size, polyploidation, and multiple nuclei formation. The hypertrophic response in both normal and injured adult heart triggers cardiomyocytes to enter into G1 phase of cell cycle, a preparatory phase, during which cells grow in size by means of synthesizing several RNAs and proteins required for the cell cycle processes. An increase in the activity/expression of G1 phase cyclins (D-type) and CDKs (CDK2 and CDK4) as well as blockage of G2/M phase is seen in hypertrophic condition, which results in premature cell cycle exit and yielding enlarged cells [77, 83, 84]. Apart from this, multinucleation and polyploidy are characteristic features of mammalian cardiomyocytes, which often occur after birth. During perinatal period, the majority of cardiomyocytes undergo additional rounds of DNA synthesis without cytokinesis (acytokinetic mitosis) that leaves them in binucleated or multinucleated states [18, 19]. In contrast to multinucleation, the polyploidy results from endoreduplication (DNA duplication) without nuclear division (karyokinesis). The polyploidy cells are having increased number of chromosomes sets (>2 N) due to shuttling between G and S phases without entering M phase. Some cells can enter into M phase and complete the assembly of nuclear spindle and segregation of sister chromatids (anaphase), but they fail at nuclear envelope breakdown (telophase) and cytokinesis (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Cell cycle variation yields cardiomyocytes with hypertrophic growth, multiple nuclei, and polyploidy. The solid green arrow indicates normal flow of cell cycle, and dotted line indicates obstruction/impairment of cell cycle phases. The solid red arrow indicates cells bypassing failed/impaired cell cycle phase and proceeding to other phases of cell cycle. In typical cell cycle, the cell enters G1 phase and gain sufficient growth prior to the onset of DNA replication in S phase. Another gap phase (G2) prepares the cell for the nuclear division (ND) and cytokinesis (CK) in M phase. In hypertrophic growth, cells enter G1 phase and exit before or after the entry into S phase. The polyploidazation and multinucleation result from oscillation of cell cycle activity between gap phase (G) and DNA synthesis phase (S) when there is a defect in mitotic phase. During multinucleation process, the cell normally completes all the events of cell cycle, including telophase (nuclear division; ND) of M phase, but it fails at cytokinesis (CK) part of M phase. The polyploidazation is distinct from multinucleation, which is due to the failure of entry into mitotic phase (M phase). In this event, the cell completes G1, S, and G2 phases of cell cycle and it exits from cell cycle or continues another round without entering into M phase

Each mammalian species seems to have its own program that decides the timing, abundance, and degree of ploidy and nucleation. However, the exact reason and the regulatory mechanisms, which drive these events under normal physiological condition, remain largely unknown. In mouse and rat, the binucleation of cardiomyocytes starts shortly after birth and it is completed by postnatal 14 days. In contrast, about 60–70 % of cardiomyocytes of sheep and ovine undergo this process before birth, in particular, at the last trimester of gestation period [19]. Nearly, 90 % of cardiomyocytes are binuclear in the adult mouse, rat, rabbit and guinea pig, while only 45 % are binucleated in dog and cow. In contrast to all these mammalian systems, nearly, two-third of cardiomyocytes remain as mono-nucleated in the human heart at birth, and their nucleation and ploidy increase between birth and adulthood [1, 7]. Several studies in rodents and human heart found that the ploidy of nuclei increases (>8 N) with increasing of age. Cardiomyocytes rapidly undergo this process in the failing heart in response to growth stimuli, which result in an increased number of multinucleated and polyploidy cells in the injured myocardial tissue [4, 10, 85, 86]. Together, these reports suggest that many adult cardiomyocytes enter into the cell cycle, but they do not complete productive proliferation cycle. This is still a poorly understood process, and is the major obstacle to target cardiomyocytes proliferation for cardiac repair and regeneration.

Cardiomyocyte proliferation: lessons from non-mammalian vertebrates

The most striking phenomenon in mammalian cardiobiology is the divergence of cardiomyocyte proliferation and nucleation capacity among different species. Some species of fishes, reptiles, and amphibians have cardiomyocyte proliferation capacity throughout the life. For instance, a complete regeneration of cardiac tissue can be seen in zebrafish after the surgical injury of cardiac apex. Genetic fate mapping studies using Cre/loxp system in the adult zebrafish revealed that the expansion of cardiomyocyte population results from pre-existing cardiomyocytes [11, 87]. However, cardiomyocyte proliferative responses in the adult mammalian system end up in hypertrophic growth, multinucleation, and polyploidization. The reason for variable response of mammalian cardiomyocytes to mitogenic stimuli remains elusive. Available reports suggest that a drastic change in structural features of cardiomyocytes, such as alterations in centrosome integrity, telomere dysfunction, epigenetic silencing of cell cycle positive regulator genes, multinucleation, and dramatic alterations of the extracellular matrix during postnatal life, implements the cell cycle defect/arrest in the majority of adult cardiomyocytes [23, 88, 89].

The structural studies in proliferating cardiomyocytes revealed that the disassembly of the cytoskeleton and contractile apparatus is required for the cell cycle progression. In proliferating neonatal cardiomyocytes, the flexibility and dissolution of myofibrillar organization, particularly, sarcomere network disorganization, are the key process of the cytokinesis. The myosin binding protein C (MYBPC) is a critical regulator of this process. An increased expression of MYBPC increases the stiffness and rigidity of myofilaments, which consequently leads to incomplete cell cycle and hypertrophic response [90, 91]. The centrosome is primarily required for the separation of copies of DNA during cell division, which also acts as a hub to integrate the initial signals that determine whether a cell should divide or not. In newts and zebrafish, the developmentally acquired structure of centrosomes remains intact in adulthood, while mammalian cardiomyocytes lose its integrity and functions (ciliogenesis and microtubule organization) right after birth. This loss induces stress signaling, such as p38MAPK, which promotes cell cycle arrest in mammalian cardiomyocytes. In contrast to this, p38-MAPK activity is suppressed in zebrafish during cardiomyocyte proliferation and regeneration [88]. Anillin is a cytokinesis phase protein, which is required for furrow construction and midbody formation during cytokinesis. However, it was observed that p38MAPK-mediated defects in the localization of anillin lead to the failure of midbody formation, which consequently result in an incomplete cell cycle and binucleation in postnatal cardiomyocytes [92]. In mammalian cardiomyocytes, it is proved that p38MAPK inhibition can promote cell division in both mono- and binucleated cardiomyocytes [64]. Similarly, the cytokinesis failure in postnatal and adult cardiomyocytes is also due to the downregulation/complete absence of septins (SEPT), a family of cytoskeletal GTPases, whose expression is crucial for the partitioning and separation of cytoplasm during mitosis [93].

Recent studies have shown that the telomere dysfunction due to its shortening provokes cell cycle arrest and binucleation in cardiomyocytes after birth. The maintenance of a certain minimum length of the telomere is essential for distinguishing chromosome ends from damaged DNA during segregation. However, the inactivation of telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) and a sharp fall in telomere length in postnatal and adult cardiomyocytes push them out from cell cycle by upregulating p21 [89]. Apart from this, epigenetic changes, such as DNA methylation and histone modification, also significantly contribute to the decrease of postnatal cardiomyocyte proliferative ability as well as heart regeneration [23, 94]. A genome sequencing study of methylated DNA in postnatal mouse cardiomyocytes found that the vast majority of DNA regions are hypermethylated during the early postnatal period (postnatal days 1–14). These hypermethylated regions are genes transcribed by important developmental signaling pathways, such as FGF, Wnt/β-catenin, and PI3K-AKT [95]. In support of this finding, Felician et al. observed that Notch signaling is largely ineffective in adult cardiomyocytes, although they are highly active in response to myocardial injury. This is due to the permanent CpG methylation of Notch-responsive promoter regions [63]. In addition, Rb family members interact with multiple chromatin remodeling factors, such as histone deacetyltransferases (HDAC), histone methyltransferases (EZH2, G9a, and Suv39h1), HP1, and DNA methyltransferase (Dnmt), and recruit them to suppress the expression of many cell cycle supportive transcription factors, such as E2F [23]. Thus, the elucidation of mechanisms and events associated with mitotic defect could help to enforce the adult cardiomyocyte proliferation.

Cardiomyocyte cell cycle: a target for cardiac repair

The cardiomyocyte retains its DNA synthesizing capacity regardless of the age. The increase of nucleation and ploidy of cardiomyocytes in the injured heart [4, 10, 85, 86] indicate that there is no big barrier in karyokinesis, but the blockage of cytokinesis is the major obstacle in adult cardiomyocyte proliferation. Several reports confirmed this notion in experimental animal models and proved that exogenous/forced expression of mitotic phase cyclins can overcome this hurdle. In the adult porcine heart, adenoviral vector-mediated overexpression of cyclin A2, a mitotic phase cyclin, promoted cytokinesis and mitosis, as well as increased cardiomyocyte numbers following myocardial infarction. This was accompanied by an improved cardiac function in those animals [96]. Similarly, the forced expression of cyclin B-cdc2 complex, a vital mitotic complex, re-initiated cell division in adult cardiomyocytes under in vivo condition [97]. Interestingly, p38MAPK inhibition stimulated cytokinesis and cell division in binucleated cardiomyocytes [64]. A combined inhibition of CDK inhibitors (p21 and p27) also promoted cytokinesis and proliferation in adult cardiomyocytes by increasing the expressions of cyclins A and E, which are vital for S-phase and G2/M-phase progression [21, 29]. These observations illustrate the capacity of cardiomyocytes to re-enter cell cycle activity. An earlier study by Beltrami et al. demonstrated that a proportion of adult cardiomyocytes can enter mitosis, complete cytokinesis, and produce daughter cells in the human heart after myocardial injury [8]. Recently, hypoxia fate mapping study in mouse heart divulged that hypoxic cardiomyocytes acquire proliferative characteristics of neonatal cardiomyocytes and they contribute to the formation of new cardiomyocytes in the adult heart [98]. Surprisingly, several studies have shown that binucleated cardiomyocytes also has the ability to re-enter the cell cycle and can increase cardiomyocyte numbers [2, 64, 86]. In mice, the binucleated adult cardiomyocytes produced both mono and binucleated cardiomyocytes [64]. In support of this, a cell tracking study using cultured adult newt cardiomyocyte found that multinucleated cells have the capacity of cytokinesis and mitotic division. In fact, some of these cells underwent several rounds of cell division with complete mitosis and cytokinesis, although outcomes varied in each cell division (i.e., yielding mono or multinucleated cells) [99]. These studies suggest that a certain population of adult cardiomyocytes has the capability of completing cell cycle in response to cardiac injury. Therefore, targeting cardiomyocyte proliferation is a possible and potential therapeutic strategy for the myocardial regeneration and repair.

Conclusive summary

Recent progress in treatment regimens for cardiac failure significantly reduced the mortality but failed to compensate the loss of cardiomyocytes, which is the primary reason for the failure of many strategies. Several experimental studies revealed the benefits of targeting cardiomyocyte cell cycle for cardiac repair and regeneration. In animal models, the forced expression of cyclin B-cdc2 complex [97] or cyclin A2 [96, 100, 101] re-initiated cell division in adult cardiomyocytes with a significant improvement of myocardial function. Likewise, cardiomyocyte-specific overexpression of cyclin D2 sustained the cell cycle activity with a marked reduction in infarction size and remarkable improvement in the mechanical function of the heart [26, 102]. On the other hand, the inhibition of CDK inhibitors (p21 and p27) [21, 29], transcription factors (Meis1) [22], or p38MAPK [64] also promisingly promoted adult cardiomyocyte proliferation and cardiac regeneration. All the above, NRG1, a potent cardiomyocyte proliferation stimulator, is showing promising outcome in clinical trials by improving cardiac function and reversing remodeling of the heart in cardiac failure patients [51, 66, 67]. Collectively, these findings provide a hope that the manipulation of cardiomyocyte cell cycle machineries could be one of the most effective strategies for cardiac regeneration and functional recovery. However, more detailed elucidation of the hindrance in cell cycle entry as well as molecular and cellular programs involved in non-productive cell cycle activity (formation of binucleated and polyploid cells) will help to efficiently utilize cell-cycle-based therapy for cardiac regeneration in clinical settings.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81522005, 81270160, and 81470522).

Contributor Information

Pei-Feng Li, Phone: +86 532 82991039, Email: peifengliqd@163.com.

Kun Wang, Phone: +86 532 82991039, Email: wangk696@163.com.

References

- 1.Bergmann O, Bhardwaj RD, Bernard S, Zdunek S, Barnabe-Heider F, Walsh S, Zupicich J, Alkass K, Buchholz BA, Druid H, Jovinge S, Frisen J. Evidence for cardiomyocyte renewal in humans. Science. 2009;324:98–102. doi: 10.1126/science.1164680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mollova M, Bersell K, Walsh S, Savla J, Das LT, Park SY, Silberstein LE, Dos Remedios CG, Graham D, Colan S, Kuhn B. Cardiomyocyte proliferation contributes to heart growth in young humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:1446–1451. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1214608110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Porrello ER, Mahmoud AI, Simpson E, Hill JA, Richardson JA, Olson EN, Sadek HA. Transient regenerative potential of the neonatal mouse heart. Science. 2011;331:1078–1080. doi: 10.1126/science.1200708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herget GW, Neuburger M, Plagwitz R, Adler CP. DNA content, ploidy level and number of nuclei in the human heart after myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res. 1997;36:45–51. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(97)00140-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Erokhina IL, Selivanova GV, Vlasova TD, Emel’ianova OI. Correlation between the level of polyploidy and hypertrophy and degree of human atrial cardiomyocyte damage in certain congenital and acquired heart pathologies. Tsitologiia. 1997;39:889–899. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Senyo SE, Steinhauser ML, Pizzimenti CL, Yang VK, Cai L, Wang M, Wu TD, Guerquin-Kern JL, Lechene CP, Lee RT. Mammalian heart renewal by pre-existing cardiomyocytes. Nature. 2013;493:433–436. doi: 10.1038/nature11682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kajstura J, Urbanek K, Perl S, Hosoda T, Zheng H, Ogorek B, Ferreira-Martins J, Goichberg P, Rondon-Clavo C, Sanada F, D’Amario D, Rota M, Del Monte F, Orlic D, Tisdale J, Leri A, Anversa P. Cardiomyogenesis in the adult human heart. Circ Res. 2010;107:305–315. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.223024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 8.Beltrami AP, Urbanek K, Kajstura J, Yan SM, Finato N, Bussani R, Nadal-Ginard B, Silvestri F, Leri A, Beltrami CA, Anversa P. Evidence that human cardiac myocytes divide after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1750–1757. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200106073442303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malliaras K, Zhang Y, Seinfeld J, Galang G, Tseliou E, Cheng K, Sun B, Aminzadeh M, Marban E. Cardiomyocyte proliferation and progenitor cell recruitment underlie therapeutic regeneration after myocardial infarction in the adult mouse heart. EMBO Mol Med. 2013;5:191–209. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201201737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kajstura J, Gurusamy N, Ogorek B, Goichberg P, Clavo-Rondon C, Hosoda T, D’Amario D, Bardelli S, Beltrami AP, Cesselli D, Bussani R, del Monte F, Quaini F, Rota M, Beltrami CA, Buchholz BA, Leri A, Anversa P. Myocyte turnover in the aging human heart. Circ Res. 2010;107:1374–1386. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.231498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jopling C, Sleep E, Raya M, Marti M, Raya A, Izpisua Belmonte JC. Zebrafish heart regeneration occurs by cardiomyocyte dedifferentiation and proliferation. Nature. 2010;464:606–609. doi: 10.1038/nature08899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takeuchi T. Regulation of cardiomyocyte proliferation during development and regeneration. Dev Growth Differ. 2014;56:402–409. doi: 10.1111/dgd.12134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Pater E, Clijsters L, Marques SR, Lin YF, Garavito-Aguilar ZV, Yelon D, Bakkers J. Distinct phases of cardiomyocyte differentiation regulate growth of the zebrafish heart. Development. 2009;136:1633–1641. doi: 10.1242/dev.030924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spater D, Hansson EM, Zangi L, Chien KR. How to make a cardiomyocyte. Development. 2014;141:4418–4431. doi: 10.1242/dev.091538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sedmera D, Thompson RP. Myocyte proliferation in the developing heart. Dev Dyn. 2011;240:1322–1334. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen H, Shi S, Acosta L, Li W, Lu J, Bao S, Chen Z, Yang Z, Schneider MD, Chien KR, Conway SJ, Yoder MC, Haneline LS, Franco D, Shou W. BMP10 is essential for maintaining cardiac growth during murine cardiogenesis. Development. 2004;131:2219–2231. doi: 10.1242/dev.01094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Christoffels VM, Habets PE, Franco D, Campione M, de Jong F, Lamers WH, Bao ZZ, Palmer S, Biben C, Harvey RP, Moorman AF. Chamber formation and morphogenesis in the developing mammalian heart. Dev Biol. 2000;223:266–278. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ikenishi A, Okayama H, Iwamoto N, Yoshitome S, Tane S, Nakamura K, Obayashi T, Hayashi T, Takeuchi T. Cell cycle regulation in mouse heart during embryonic and postnatal stages. Dev Growth Differ. 2012;54:731–738. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2012.01373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chattergoon NN, Louey S, Stork PJ, Giraud GD, Thornburg KL. Unexpected maturation of PI3K and MAPK-ERK signaling in fetal ovine cardiomyocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2014;307:H1216–H1225. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00833.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tane S, Okayama H, Ikenishi A, Amemiya Y, Nakayama KI, Takeuchi T. Two inhibitory systems and CKIs regulate cell cycle exit of mammalian cardiomyocytes after birth. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;466:147–154. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.08.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tane S, Ikenishi A, Okayama H, Iwamoto N, Nakayama KI, Takeuchi T. CDK inhibitors, p21(Cip1) and p27(Kip1), participate in cell cycle exit of mammalian cardiomyocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;443:1105–1109. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.12.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mahmoud AI, Kocabas F, Muralidhar SA, Kimura W, Koura AS, Thet S, Porrello ER, Sadek HA. Meis1 regulates postnatal cardiomyocyte cell cycle arrest. Nature. 2013;497:249–253. doi: 10.1038/nature12054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sdek P, Zhao P, Wang Y, Huang CJ, Ko CY, Butler PC, Weiss JN, Maclellan WR. Rb and p130 control cell cycle gene silencing to maintain the postmitotic phenotype in cardiac myocytes. J Cell Biol. 2011;194:407–423. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201012049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tamamori-Adachi M, Goto I, Yamada K, Kitajima S. Differential regulation of cyclin D1 and D2 in protecting against cardiomyocyte proliferation. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:3768–3774. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.23.7239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tamamori-Adachi M, Ito H, Sumrejkanchanakij P, Adachi S, Hiroe M, Shimizu M, Kawauchi J, Sunamori M, Marumo F, Kitajima S, Ikeda MA. Critical role of cyclin D1 nuclear import in cardiomyocyte proliferation. Circ Res. 2003;92:e12–e19. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000049105.15329.1C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pasumarthi KB, Nakajima H, Nakajima HO, Soonpaa MH, Field LJ. Targeted expression of cyclin D2 results in cardiomyocyte DNA synthesis and infarct regression in transgenic mice. Circ Res. 2005;96:110–118. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000152326.91223.4F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kang MJ, Kim JS, Chae SW, Koh KN, Koh GY. Cyclins and cyclin dependent kinases during cardiac development. Mol Cells. 1997;7:360–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim WH, Joo CU, Ku JH, Ryu CH, Koh KN, Koh GY, Ko JK. Cell cycle regulators during human atrial development. Korean J Intern Med. 1998;13:77–82. doi: 10.3904/kjim.1998.13.2.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Di Stefano V, Giacca M, Capogrossi MC, Crescenzi M, Martelli F. Knockdown of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors induces cardiomyocyte re-entry in the cell cycle. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:8644–8654. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.184549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Engel FB, Hauck L, Boehm M, Nabel EG, Dietz R, von Harsdorf R. p21(CIP1) Controls proliferating cell nuclear antigen level in adult cardiomyocytes. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:555–565. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.2.555-565.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kochilas LK, Li J, Jin F, Buck CA, Epstein JA. p57Kip2 expression is enhanced during mid-cardiac murine development and is restricted to trabecular myocardium. Pediatr Res. 1999;45:635–642. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199905010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hauck L, Hansmann G, Dietz R, von Harsdorf R. Inhibition of hypoxia-induced apoptosis by modulation of retinoblastoma protein-dependent signaling in cardiomyocytes. Circ Res. 2002;91:782–789. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000041030.98642.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haley SA, Zhao T, Zou L, Klysik JE, Padbury JF, Kochilas LK. Forced expression of the cell cycle inhibitor p57Kip2 in cardiomyocytes attenuates ischemia-reperfusion injury in the mouse heart. BMC Physiol. 2008;8:4. doi: 10.1186/1472-6793-8-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park DS, Tompkins RO, Liu F, Zhang J, Phoon CK, Zavadil J, Fishman GI. Pocket proteins critically regulate cell cycle exit of the trabecular myocardium and the ventricular conduction system. Biol Open. 2013;2:968–978. doi: 10.1242/bio.20135785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.MacLellan WR, Garcia A, Oh H, Frenkel P, Jordan MC, Roos KP, Schneider MD. Overlapping roles of pocket proteins in the myocardium are unmasked by germ line deletion of p130 plus heart-specific deletion of Rb. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:2486–2497. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.6.2486-2497.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hille S, Dierck F, Kuhl C, Sosna J, Adam-Klages S, Adam D, Lullmann-Rauch R, Frey N, Kuhn C. Dyrk1a regulates the cardiomyocyte cell cycle via D-cyclin-dependent Rb/E2f-signalling. Cardiovasc Res. 2016;110:381–394. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvw074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ebelt H, Hufnagel N, Neuhaus P, Neuhaus H, Gajawada P, Simm A, Muller-Werdan U, Werdan K, Braun T. Divergent siblings: E2F2 and E2F4 but not E2F1 and E2F3 induce DNA synthesis in cardiomyocytes without activation of apoptosis. Circ Res. 2005;96:509–517. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000159705.17322.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ebelt H, Zhang Y, Kampke A, Xu J, Schlitt A, Buerke M, Muller-Werdan U, Werdan K, Braun T. E2F2 expression induces proliferation of terminally differentiated cardiomyocytes in vivo. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;80:219–226. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Amerongen MJ, Diehl F, Novoyatleva T, Patra C, Engel FB. E2F4 is required for cardiomyocyte proliferation. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;86:92–102. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dingar D, Konecny F, Zou J, Sun X, von Harsdorf R. Anti-apoptotic function of the E2F transcription factor 4 (E2F4)/p130, a member of retinoblastoma gene family in cardiac myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2012;53:820–828. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Flink IL, Oana S, Maitra N, Bahl JJ, Morkin E. Changes in E2F complexes containing retinoblastoma protein family members and increased cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor activities during terminal differentiation of cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1998;30:563–578. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1997.0620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chakraborty S, Yutzey KE. Tbx20 regulation of cardiac cell proliferation and lineage specialization during embryonic and fetal development in vivo. Dev Biol. 2012;363:234–246. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chakraborty S, Sengupta A, Yutzey KE. Tbx20 promotes cardiomyocyte proliferation and persistence of fetal characteristics in adult mouse hearts. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2013;62:203–213. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xiang FL, Guo M, Yutzey KE. Overexpression of Tbx20 in adult cardiomyocytes promotes proliferation and improves cardiac function after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2016;133:1081–1092. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.019357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dorr KM, Amin NM, Kuchenbrod LM, Labiner H, Charpentier MS, Pevny LH, Wessels A, Conlon FL. Casz1 is required for cardiomyocyte G1-to-S phase progression during mammalian cardiac development. Development. 2015;142:2037–2047. doi: 10.1242/dev.119107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rojas A, Kong SW, Agarwal P, Gilliss B, Pu WT, Black BL. GATA4 is a direct transcriptional activator of cyclin D2 and Cdk4 and is required for cardiomyocyte proliferation in anterior heart field-derived myocardium. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:5420–5431. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00717-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamak A, Latinkic BV, Dali R, Temsah R, Nemer M. Cyclin D2 is a GATA4 cofactor in cardiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:1415–1420. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1312993111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Estrella NL, Clark AL, Desjardins CA, Nocco SE, Naya FJ. MEF2D deficiency in neonatal cardiomyocytes triggers cell cycle re-entry and programmed cell death in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:24367–24380. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.666461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sengupta A, Kalinichenko VV, Yutzey KE. FoxO1 and FoxM1 transcription factors have antagonistic functions in neonatal cardiomyocyte cell-cycle withdrawal and IGF1 gene regulation. Circ Res. 2013;112:267–277. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.277442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rochais F, Sturny R, Chao CM, Mesbah K, Bennett M, Mohun TJ, Bellusci S, Kelly RG. FGF10 promotes regional foetal cardiomyocyte proliferation and adult cardiomyocyte cell-cycle re-entry. Cardiovasc Res. 2014;104:432–442. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvu232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bersell K, Arab S, Haring B, Kuhn B. Neuregulin1/ErbB4 signaling induces cardiomyocyte proliferation and repair of heart injury. Cell. 2009;138:257–270. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Evans-Anderson HJ, Alfieri CM, Yutzey KE. Regulation of cardiomyocyte proliferation and myocardial growth during development by FOXO transcription factors. Circ Res. 2008;102:686–694. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.163428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Novoyatleva T, Diehl F, van Amerongen MJ, Patra C, Ferrazzi F, Bellazzi R, Engel FB. TWEAK is a positive regulator of cardiomyocyte proliferation. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;85:681–690. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Novoyatleva T, Sajjad A, Pogoryelov D, Patra C, Schermuly RT, Engel FB. FGF1-mediated cardiomyocyte cell cycle reentry depends on the interaction of FGFR-1 and Fn14. FASEB J. 2014;28:2492–2503. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-243576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Buikema JW, Mady AS, Mittal NV, Atmanli A, Caron L, Doevendans PA, Sluijter JP, Domian IJ. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling directs the regional expansion of first and second heart field-derived ventricular cardiomyocytes. Development. 2013;140:4165–4176. doi: 10.1242/dev.099325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lin Z, Zhou P, von Gise A, Gu F, Ma Q, Chen J, Guo H, van Gorp PR, Wang DZ, Pu WT. Pi3kcb links Hippo-YAP and PI3K-AKT signaling pathways to promote cardiomyocyte proliferation and survival. Circ Res. 2015;116:35–45. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.304457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.von Gise A, Lin Z, Schlegelmilch K, Honor LB, Pan GM, Buck JN, Ma Q, Ishiwata T, Zhou B, Camargo FD, Pu WT. YAP1, the nuclear target of Hippo signaling, stimulates heart growth through cardiomyocyte proliferation but not hypertrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:2394–2399. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116136109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sudol M. Neuregulin 1-activated ERBB4 as a “dedicated” receptor for the Hippo-YAP pathway. Sci Signal. 2014;7:pe29. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aaa2710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.D’Uva G, Aharonov A, Lauriola M, Kain D, Yahalom-Ronen Y, Carvalho S, Weisinger K, Bassat E, Rajchman D, Yifa O, Lysenko M, Konfino T, Hegesh J, Brenner O, Neeman M, Yarden Y, Leor J, Sarig R, Harvey RP, Tzahor E. ERBB2 triggers mammalian heart regeneration by promoting cardiomyocyte dedifferentiation and proliferation. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17:627–638. doi: 10.1038/ncb3149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wadugu B, Kuhn B. The role of neuregulin/ErbB2/ErbB4 signaling in the heart with special focus on effects on cardiomyocyte proliferation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302:H2139–H2147. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00063.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fan R, Kim NG, Gumbiner BM. Regulation of Hippo pathway by mitogenic growth factors via phosphoinositide 3-kinase and phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:2569–2574. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216462110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Campa VM, Gutierrez-Lanza R, Cerignoli F, Diaz-Trelles R, Nelson B, Tsuji T, Barcova M, Jiang W, Mercola M. Notch activates cell cycle reentry and progression in quiescent cardiomyocytes. J Cell Biol. 2008;183:129–141. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200806104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Felician G, Collesi C, Lusic M, Martinelli V, Ferro MD, Zentilin L, Zacchigna S, Giacca M. Epigenetic modification at Notch responsive promoters blunts efficacy of inducing notch pathway reactivation after myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2014;115:636–649. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.304517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Engel FB, Schebesta M, Duong MT, Lu G, Ren S, Madwed JB, Jiang H, Wang Y, Keating MT. p38 MAP kinase inhibition enables proliferation of adult mammalian cardiomyocytes. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1175–1187. doi: 10.1101/gad.1306705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wei BR, Martin PL, Hoover SB, Spehalski E, Kumar M, Hoenerhoff MJ, Rozenberg J, Vinson C, Simpson RM. Capacity for resolution of Ras-MAPK-initiated early pathogenic myocardial hypertrophy modeled in mice. Comp Med. 2011;61:109–118. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gao R, Zhang J, Cheng L, Wu X, Dong W, Yang X, Li T, Liu X, Xu Y, Li X, Zhou M. A Phase II, randomized, double-blind, multicenter, based on standard therapy, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of recombinant human neuregulin-1 in patients with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:1907–1914. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jabbour A, Hayward CS, Keogh AM, Kotlyar E, McCrohon JA, England JF, Amor R, Liu X, Li XY, Zhou MD, Graham RM, Macdonald PS. Parenteral administration of recombinant human neuregulin-1 to patients with stable chronic heart failure produces favourable acute and chronic haemodynamic responses. Eur J Heart Fail. 2011;13:83–92. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfq152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Polizzotti BD, Ganapathy B, Walsh S, Choudhury S, Ammanamanchi N, Bennett DG, dos Remedios CG, Haubner BJ, Penninger JM, Kuhn B. Neuregulin stimulation of cardiomyocyte regeneration in mice and human myocardium reveals a therapeutic window. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:281ra245. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa5171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Eulalio A, Mano M, Dal Ferro M, Zentilin L, Sinagra G, Zacchigna S, Giacca M. Functional screening identifies miRNAs inducing cardiac regeneration. Nature. 2012;492:376–381. doi: 10.1038/nature11739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chen J, Huang ZP, Seok HY, Ding J, Kataoka M, Zhang Z, Hu X, Wang G, Lin Z, Wang S, Pu WT, Liao R, Wang DZ. mir-17-92 cluster is required for and sufficient to induce cardiomyocyte proliferation in postnatal and adult hearts. Circ Res. 2013;112:1557–1566. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.300658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tian Y, Liu Y, Wang T, Zhou N, Kong J, Chen L, Snitow M, Morley M, Li D, Petrenko N, Zhou S, Lu M, Gao E, Koch WJ, Stewart KM, Morrisey EE. A microRNA-Hippo pathway that promotes cardiomyocyte proliferation and cardiac regeneration in mice. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:279ra238. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3010841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li X, Wang J, Jia Z, Cui Q, Zhang C, Wang W, Chen P, Ma K, Zhou C. MiR-499 regulates cell proliferation and apoptosis during late-stage cardiac differentiation via Sox6 and cyclin D1. PLoS One. 2013;8:e74504. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Liang D, Li J, Wu Y, Zhen L, Li C, Qi M, Wang L, Deng F, Huang J, Lv F, Liu Y, Ma X, Yu Z, Zhang Y, Chen YH. miRNA-204 drives cardiomyocyte proliferation via targeting Jarid2. Int J Cardiol. 2015;201:38–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.06.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mysliwiec MR, Carlson CD, Tietjen J, Hung H, Ansari AZ, Lee Y. Jarid2 (Jumonji, AT rich interactive domain 2) regulates NOTCH1 expression via histone modification in the developing heart. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:1235–1241. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.315945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Clark AL, Naya FJ. MicroRNAs in the Myocyte Enhancer Factor 2 (MEF2)-regulated Gtl2-Dio3 noncoding RNA locus promote cardiomyocyte proliferation by targeting the transcriptional coactivator cited2. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:23162–23172. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.672659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Porrello ER, Johnson BA, Aurora AB, Simpson E, Nam YJ, Matkovich SJ, Dorn GW, 2nd, van Rooij E, Olson EN. MiR-15 family regulates postnatal mitotic arrest of cardiomyocytes. Circ Res. 2011;109:670–679. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.248880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Huang S, Zou X, Zhu JN, Fu YH, Lin QX, Liang YY, Deng CY, Kuang SJ, Zhang MZ, Liao YL, Zheng XL, Yu XY, Shan ZX. Attenuation of microRNA-16 derepresses the cyclins D1, D2 and E1 to provoke cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. J Cell Mol Med. 2015;19:608–619. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cao X, Wang J, Wang Z, Du J, Yuan X, Huang W, Meng J, Gu H, Nie Y, Ji B, Hu S, Zheng Z. MicroRNA profiling during rat ventricular maturation: a role for miR-29a in regulating cardiomyocyte cell cycle re-entry. FEBS Lett. 2013;587:1548–1555. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.01.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhang Y, Matsushita N, Eigler T, Marban E. Targeted microRNA interference promotes postnatal cardiac cell cycle re-entry. J Regen Med. 2013;2:2. doi: 10.4172/2325-9620.1000108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Crippa S, Nemir M, Ounzain S, Ibberson M, Berthonneche C, Sarre A, Boisset G, Maison D, Harshman K, Xenarios I, Diviani D, Schorderet D, Pedrazzini T. Comparative transcriptome profiling of the injured zebrafish and mouse hearts identifies miRNA-dependent repair pathways. Cardiovasc Res. 2016;110:73–84. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvw031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Liu N, Bezprozvannaya S, Williams AH, Qi X, Richardson JA, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. microRNA-133a regulates cardiomyocyte proliferation and suppresses smooth muscle gene expression in the heart. Genes Dev. 2008;22:3242–3254. doi: 10.1101/gad.1738708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yang Y, Cheng HW, Qiu Y, Dupee D, Noonan M, Lin YD, Fisch S, Unno K, Sereti KI, Liao R. MicroRNA-34a plays a key role in cardiac repair and regeneration following myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2015;117:450–459. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.305962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hinrichsen R, Hansen AH, Haunso S, Busk PK. Phosphorylation of pRb by cyclin D kinase is necessary for development of cardiac hypertrophy. Cell Prolif. 2008;41:813–829. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2008.00549.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Busk PK, Bartkova J, Strom CC, Wulf-Andersen L, Hinrichsen R, Christoffersen TE, Latella L, Bartek J, Haunso S, Sheikh SP. Involvement of cyclin D activity in left ventricle hypertrophy in vivo and in vitro. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;56:64–75. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(02)00510-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tevzadze N, Rukhadze R, Dzidziguri D. The age related changes in cell cycle of mice cardiomyocytes. Georgian Med News. 2005;128:87–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Stephen MJ, Poindexter BJ, Moolman JA, Sheikh-Hamad D, Bick RJ. Do binucleate cardiomyocytes have a role in myocardial repair? Insights using isolated rodent myocytes and cell culture. Open Cardiovasc Med J. 2009;3:1–7. doi: 10.2174/1874192400903010001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kikuchi K, Holdway JE, Werdich AA, Anderson RM, Fang Y, Egnaczyk GF, Evans T, Macrae CA, Stainier DY, Poss KD. Primary contribution to zebrafish heart regeneration by gata4(+) cardiomyocytes. Nature. 2010;464:601–605. doi: 10.1038/nature08804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zebrowski DC, Vergarajauregui S, Wu CC, Piatkowski T, Becker R, Leone M, Hirth S, Ricciardi F, Falk N, Giessl A, Just S, Braun T, Weidinger G, Engel FB. Developmental alterations in centrosome integrity contribute to the post-mitotic state of mammalian cardiomyocytes. Elife. 2015 doi: 10.7554/eLife.05563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Aix E, Gutierrez-Gutierrez O, Sanchez-Ferrer C, Aguado T, Flores I. Postnatal telomere dysfunction induces cardiomyocyte cell-cycle arrest through p21 activation. J Cell Biol. 2016;213:571–583. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201510091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Knoll R. Myosin binding protein C: implications for signal-transduction. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2012;33:31–42. doi: 10.1007/s10974-011-9281-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Jiang J, Burgon PG, Wakimoto H, Onoue K, Gorham JM, O’Meara CC, Fomovsky G, McConnell BK, Lee RT, Seidman JG, Seidman CE. Cardiac myosin binding protein C regulates postnatal myocyte cytokinesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:9046–9051. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1511004112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Engel FB, Schebesta M, Keating MT. Anillin localization defect in cardiomyocyte binucleation. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;41:601–612. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ahuja P, Perriard E, Trimble W, Perriard JC, Ehler E. Probing the role of septins in cardiomyocytes. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312:1598–1609. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gornikiewicz B, Ronowicz A, Krzeminski M, Sachadyn P. Changes in gene methylation patterns in neonatal murine hearts: implications for the regenerative potential. BMC Genom. 2016;17:231. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-2545-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sim CB, Ziemann M, Kaspi A, Harikrishnan KN, Ooi J, Khurana I, Chang L, Hudson JE, El-Osta A, Porrello ER. Dynamic changes in the cardiac methylome during postnatal development. FASEB J. 2015;29:1329–1343. doi: 10.1096/fj.14-264093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Shapiro SD, Ranjan AK, Kawase Y, Cheng RK, Kara RJ, Bhattacharya R, Guzman-Martinez G, Sanz J, Garcia MJ, Chaudhry HW. Cyclin A2 induces cardiac regeneration after myocardial infarction through cytokinesis of adult cardiomyocytes. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:224ra227. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bicknell KA, Coxon CH, Brooks G. Forced expression of the cyclin B1-CDC2 complex induces proliferation in adult rat cardiomyocytes. Biochem J. 2004;382:411–416. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]