Abstract

Practical relevance Feline herpesvirus-1 (FHV-1) is a major cause of feline morbidity. Following exposure to the virus, virtually all cats become persistently infected and many of these will develop recrudescent disease on one or more occasions during their lifetime. Acute ocular herpetic disease manifests as conjunctivitis, corneal ulceration and keratitis, and can be severe and painful. Repeated bouts of recrudescent ocular disease can lead to progressive corneal pathology that can be ultimately blinding in affected cats.

Global importance FHV-1 has a worldwide distribution, with reported exposure rates in some cat populations of up to 97%. As such it is a significant cause of clinical disease in the global cat population.

Patient group Young and adolescent cats are most at risk of acute primary disease, and the vast majority of these will become persistently infected. Around half of all persistently infected cats will shed virus at some stage in their life and these may develop recrudescent ocular disease.

Clinical challenges Treatment of FHV-1 ocular disease is challenging. Antiviral medications may be expensive, and require good owner and patient compliance. Clinical responses in patients can be variable. Selecting the appropriate therapeutic approach requires good clinical judgement, with assessment of factors such as severity and stage of clinical disease, patient and owner compliance, and financial considerations.

Evidence base Although a wide range of antiviral treatments is available, few have been tested in controlled clinical trials. Therapeutic decisions are, therefore, often based on results of in vitro studies, case-based reports and anecdote. Large, masked, controlled clinical trials are required in order to determine the efficacy of the antiviral drugs currently available to treat FHV-1.

Viral characteristics and epidemiology

Feline herpesvirus-1 (FHV-1) is a member of the subfamily Alphaherpesvirinae. These are double-stranded DNA viruses characterised by their short replication cycle, rapid cell-to-cell spread, tendency to induce cell lysis, and persistence in sensory ganglia of their host. Other members of the subfamily include varicella zoster virus (the cause of chickenpox and shingles) and human herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 (HSV-1, HSV-2; the causes of oral and genital herpes). Clinically, members of this subfamily tend to cause acute lytic disease followed by periods of latency and subsequent intermittent recrudescent disease (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Features of FHV-1 disease that are typical for alphaherpesviruses

| Alphaherpesvirus characteristic | FHV-1 disease characteristics | FHV-1 clinical signs and epidemiology |

|---|---|---|

| Short replication cycle | Primary infection is characterised by acute disease which is usually self-limiting over a period of 2–3 weeks | Causes acute rhinotracheitis, conjunctivitis and keratitis in kittens and adolescent cats |

| Rapid spread in cell culture | FHV-1 is highly infectious in the acute phase of primary infection | Capable of causing epidemics of acute viral disease in cat colonies |

| Causes lysis of infected cells during acute phase of infection | Leads to acute cellular damage of infected epithelial cells | Causes ulceration of infected conjunctival and corneal epithelial cells in acute disease |

| Establishment of latency | Latency established in trigeminal ganglion in most or all cats | Recrudescent disease occurs in around 50% of infected cats |

Serological studies show that FHV-1 is widespread in the feline population worldwide, with reported exposure rates of up to 97%. 1 Following exposure to FHV-1, more than 80% of cats become persistently infected. 2 Of these, 45% will subsequently shed virus spontaneously or as a result of natural stress situations, while around 70% will shed virus in response to corticosteroid administration. 2

Following exposure to FHV-1, more than 80% of cats become persistently infected. Of these, 45% will subsequently shed virus spontaneously or as a result of natural stress situations, while around 70% will shed virus in response to corticosteroid administration.

Globally, there is little genomic variation between FHV-1 strains, with only three main genotype groups recognised. Despite this, experimental infection studies have shown that there is significant variation in virulence between field isolates of the same strain, which may in part explain the variation in severity of clinical signs that is recognised clinically.

Pathogenesis of FHV-1 disease

Transmission

FHV-1 is relatively unstable in the environment, persisting for up to 18 h in moist conditions and a shorter duration in dry conditions. It is susceptible to most disinfectants, antiseptics and detergents. The main source of transmission between cats are bodily fluids, in particular respiratory secretions, which are passed on via sneezing, contaminated fomites or unhygienic handling practices. 3

Primary infection

Primary infection occurs most frequently in kittens and adolescent cats, as maternal antibodies decline from around 8 weeks of age. However, even vaccinated cats remain at some risk because FHV-1 vaccines, both parenteral and intranasal, confer only partial immunity against clinical signs and no protection against reactivation/shedding. 4

FHV-1 preferentially infects mucoepithelial cells of the tonsils, conjunctiva and nasal mucosa, 5 but there is also significant infection of corneal epithelial cells. 6 The resultant lytic infection is characterised by rapid replication and acute cellular damage leading to cytolysis. Clinical signs develop 2–6 days after infection. Ocular signs associated with this phase are acute conjunctivitis and epithelial keratitis characterised by the formation of punctate and dendritic epithelial ulcers that have been shown to persist for up to 24 days in experimental infections. 6

Latency

The establishment of latency in the host tissue is a key characteristic of herpesviruses. During primary infection, FHV-1 virions invade sensory nerve endings of the trigeminal nerve within the host tissue and travel to the trigeminal ganglion, which is housed in a depression within the petrous temporal bone in the middle cranial fossa at the base of the skull. Here FHV-1 develops a latent state in which the genome persists in episomes within the cell nuclei of the trigeminal ganglia. 7 Although this is a clinically quiescent phase there is transcription of latency-associated transcripts (LATs), which are RNA species that play an, as yet, incompletely understood role in maintaining latency and allowing recrudescent disease. 8,9

Reducing environmental stress is a particularly important management strategy for recrudescent disease.

The identification of LATs within a tissue is considered proof that the tissue acts as a site of latency for the virus. While latency within the trigeminal ganglia is proven, there is debate as to whether FHV-1 is able to maintain latency within other tissues. Human herpesvirus LATs have been identified within human cornea, raising the question as to whether feline corneal tissue might serve as a site of latency for FHV-1. FHV-1 DNA has certainly been identified in corneal tissue from clinically normal cats, but this finding may be attributable to a low grade persistent infection rather than constitute evidence of true latency. 4 A study using reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) failed to identify LATs in clinically normal feline corneas, suggesting that the feline cornea does not support latency of FHV-1. 10

Recrudescent disease

Latent FHV-1 virus may be reactivated and cause recrudescent clinical disease. This has been recorded spontaneously as well as in association with various stressors including systemic corticosteroid administration, co-infection with other agents, change of housing, parturition and lactation. 2

The molecular mechanism behind viral recrudescence is poorly understood, but it results in viral replication and migration down the sensory axons to epithelial tissues. This may result in:

Re-excretion of virus in the absence of clinical signs (subclinical shedding).

Lytic infection, with clinical signs similar to, although usually less severe than, those of the primary infection.

Development of immunopathological disease (chronic stromal keratitis) as the host mounts an immune response against viral antigens within the cornea. 11

Persistent infection

The advent of PCR technology has led to the identification of a previously unrecognised stage of herpes disease pathogenesis — that of persistent viral infection in non-neural cells. In an experimental murine model, herpes DNA was identified within the conjunctiva and eyelid in chronic inflammatory eyelid disease, raising the possibility that an equivalent mechanism may be involved in feline chronic ocular and periocular disease. 12

Evasion of the host immune system.

Both humoral and cell-mediated arms of the immune response are mobilised following primary infection with FHV-1. In response, the alphaherpesviruses have evolved a large number of countermeasures to allow maintenance of infection and establishment of latency. These are outlined in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

| Disease state | Viral activity | Target cell response | Immune system response: humoral | Immune system response: cell-mediated | Viral countermeasures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary infection | Virus binds to and infects epithelial cells of conjunctiva, tonsils, nasal mucosa and cornea | Infected cells release pro-inflammatory molecules including prostaglandins, leukotrienes and cytokines including TNF-α, IFN-α, IL-1 and IL-12 | IgM-, IgA- and IgG- mediated attack against viral surface glycoproteins | NK-, DC-, macrophage- and CD8+ CTL-mediated destruction of infected host cells |

|

| Latency | Viral genome exists as episomes within nuclei of trigeminal ganglia | Minimal | Absence of cell-free virus results in minimal humoral immune response | CD8+ T-cells and IFN-γ production thought to play role in maintaining latency | LATs involved in latency and allow recrudescent disease Minimal viral protein translation during latency allows evasion of humoral and cell-mediated response |

TNF = tumour necrosis factor, IFN = interferon, CTL = cytotoxic T lymphocyte, NK = natural killer cell, DC = dendritic cell, IL = interleukin, MHC = major histocompatibility complex, LAT = latency-associated transcript

Ocular manifestations of FHV-1

FHV-1 has been linked to a wide range of feline ocular and periocular diseases (see right).

Ophthalmia neonatorum

Ocular FHV-1 infection in the neonatal period, prior to eyelid opening, can lead to a build up of mucopurulent discharge behind the closed eyelids (Fig 1). 15 This can cause extensive corneal damage and globe rupture in severe cases. Treatment consists of premature opening of the palpebral fissure and irrigation of the ocular surface.

FIG 1.

Ophthalmia neonatorum in a young kitten. Courtesy of Professor Sheila Crispin

Conjunctivitis

FHV-1 is a major cause of acute and chronic conjunctivitis. In primary infections, acute conjunctivitis occurs in conjunction with rhinotracheitis, following an incubation period of 2–6 days. 6 The conjunctivitis is usually bilateral, with signs of hyper-aemia, serous ocular discharge and a variable degree of chemosis. Areas of conjunctival ulceration may develop secondarily to viral-induced epithelial necrosis. In the majority of cases, the clinical signs resolve by 10–20 days post-infection. Recurrent acute conjunctivitis is a feature of viral recrudescence.

Ocular disease linked to FHV-1.

Ophthalmia neonatorum

Conjunctivitis

-

Keratitis

— Dendritic ulceration

— Geographic corneal ulceration

— Chronic stromal keratitis

Symblepharon

Corneal sequestration

Eosinophilic conjunctivitis and keratitis

Keratoconjunctivitis sicca

Calcific band keratopathy

Periocular dermatitis

Anterior uveitis

FHV-1 is also a major cause of chronic conjunctivitis. 16

Keratitis

Dendritic ulceration

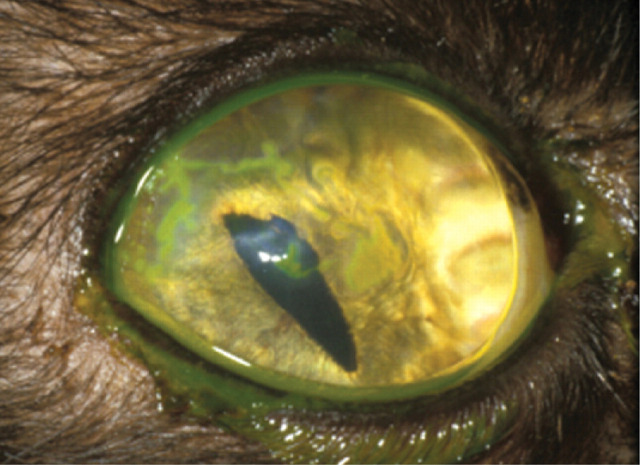

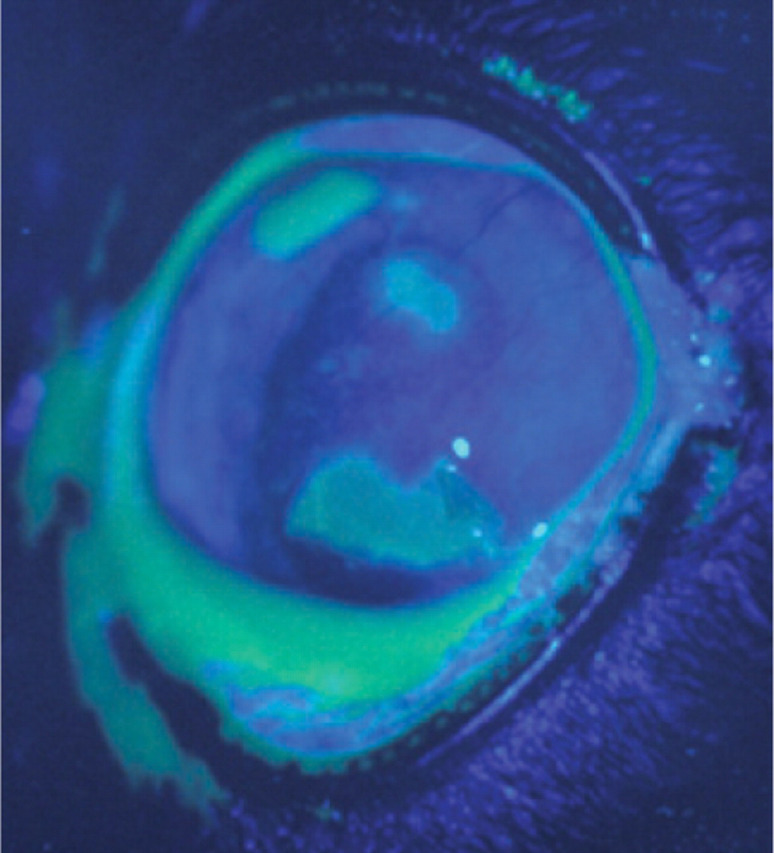

The presence of dendritic corneal ulcers is considered pathognomonic for FHV-1 infection. 6 FHV-1 infection of the corneal epithelial cells in acute primary infection leads to corneal ulceration, which typically manifests as linear or branching epithelial defects (Fig 2). These can be very fine in appearance. Therefore, magnified examination under cobalt blue light, following application of topical fluorescein to the ocular surface, is recommended. Rose Bengal stain may also be used to aid identification of dendritic ulcers (Fig 3). However, it can be locally irritant so the ocular surface should be flushed thoroughly following its application.

FIG 2.

Dendritic corneal ulceration stained with topical fluorescein dye. Courtesy of Professor Sheila Crispin

FIG 3.

Dendritic corneal ulceration stained with Rose Bengal dye

The presence of dendritic corneal ulcers is considered pathognomonic for FHV-1 infection.

Geographic corneal ulceration

Larger areas of geographic corneal ulceration may also develop as a result of primary infection. 6 These may be single or multiple (Fig 4) in appearance.

FIG 4.

Geographic corneal ulceration stained with topical fluorescein dye and photographed under cobalt blue light. Courtesy of Professor Sheila Crispin

In recrudescent infections, either dendritic or geographic corneal ulceration may be a clinical feature.

Chronic stromal keratitis

Following multiple bouts of recrudescent disease or periods of chronic ulceration, the corneal stroma may develop chronic inflammatory changes including neovascularisation, inflammatory cell infiltration, pigmentation, scarring and fibrosis (Fig 5). This chronic stromal keratitis is a result of an (ineffective) immune response to viral antigens sequestered within the cornea. 17

FIG 5.

Chronic stromal keratitis, characterised by stromal neovascularisation and progressive scarring

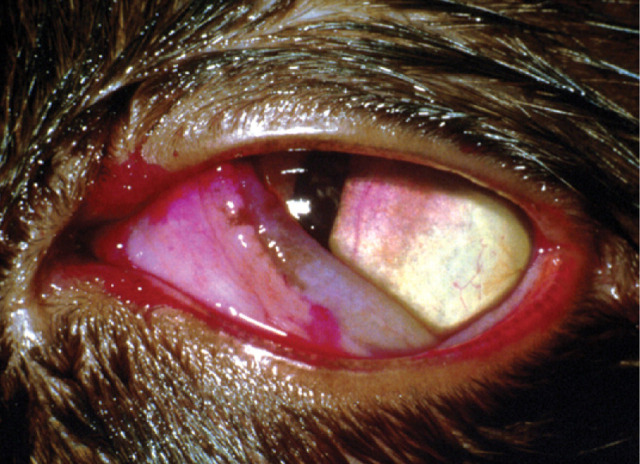

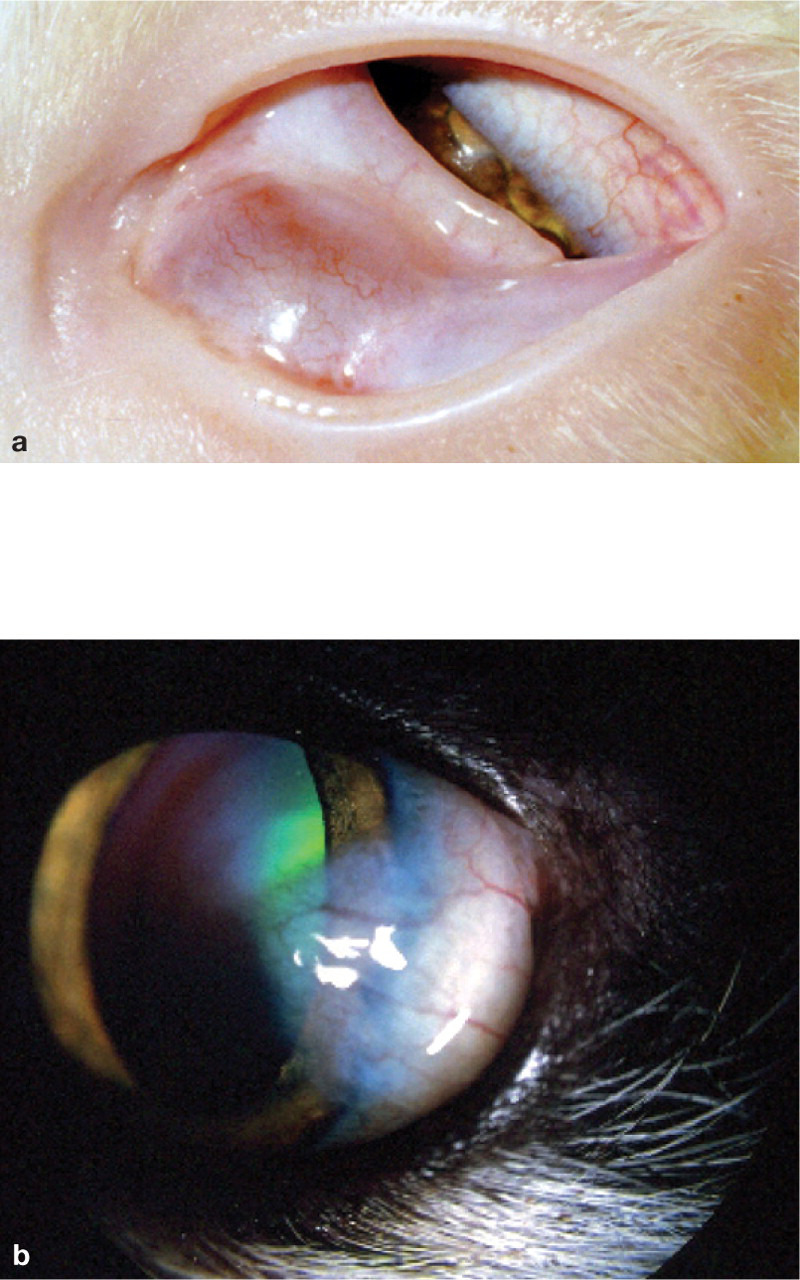

Symblepharon

Severe conjunctivitis in kittens and adolescent cats may lead to adhesion of the conjunctiva to itself (or to the cornea if corneal ulceration has been present). 4 Such symblepharon formation can cause significant ocular problems including inability to blink, destruction of the lacrimal gland ductules (with resultant functional keratoconjunctivitis sicca [KCS]), and conjunctivalisation of the cornea, leading to blindness (Fig 6).

FIG 6.

(a) Symblepharon formation in a young cat. Note the extensive adhesions between the third eyelid and palpebral conjunctiva. (b) Localised conjunctivalisation of the cornea in an FHV-1 infected cat

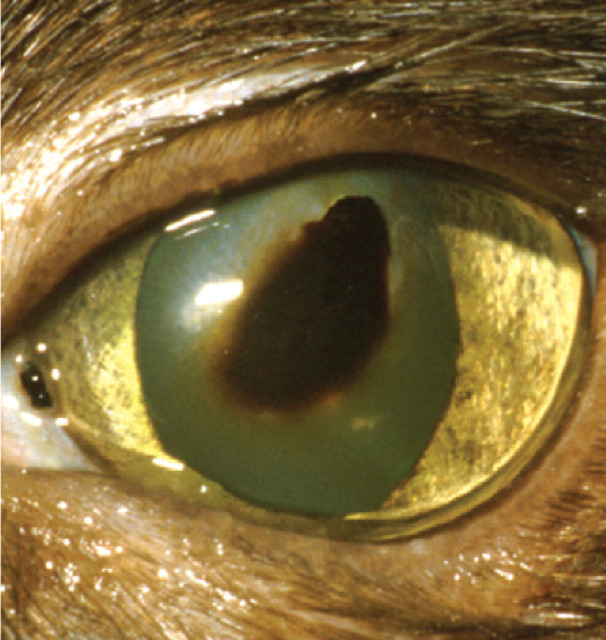

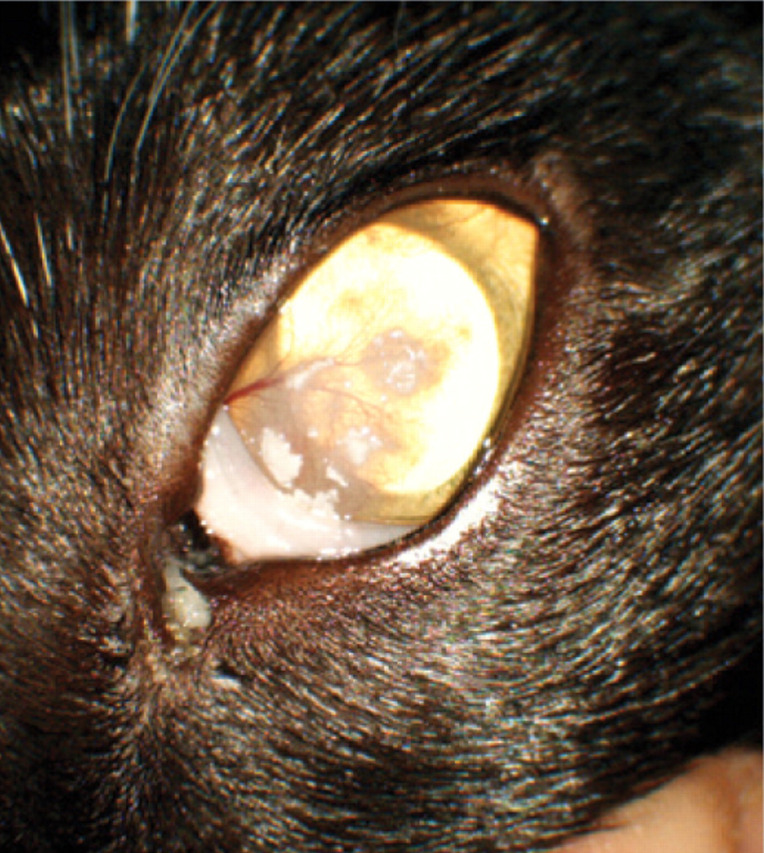

Corneal sequestration

Corneal sequestrum development is a common disease in cats. The term describes a focal area of corneal stromal degeneration associated with a brown/black discolouration (Fig 7). There is a breed predisposition in the Persian and Himalayan. In these breeds the condition may represent a primary stromal disease, but the majority of cases are associated with chronic corneal ulceration or chronic keratitis. 4,18 As such, FHV-1 has been strongly implicated in the aetiology of the condition. Topical corticosteroid use in cats experimentally infected with FHV-1 has been reported to induce corneal sequestrum formation. 6 In two separate PCR studies on sequestra samples, FHV-1 DNA was identified in 18% and 55% of cases. 19,20

FIG 7.

Corneal sequestrum

Corneal sequestra are not responsive to medical treatment, and superficial keratectomy with or without grafting procedures (conjunctival pedicle graft or corneoconjunctival transposition) is recommended.

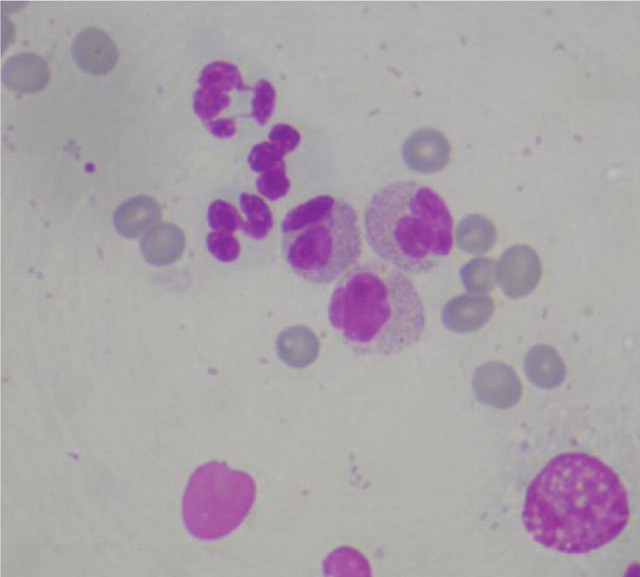

Eosinophilic conjunctivitis and keratitis

Clinically, eosinophilic conjunctivitis or keratitis manifests as a superficial proliferative, irregular, white/pink vascularised infiltration of the conjunctiva and/or cornea (Fig 8). 4

FIG 8.

(a,b) Eosinophilic keratitis. (a) Courtesy of Professor Sheila Crispin

The condition may be unilateral or bilateral. 21 There is no apparent link with feline eosinophilic complex. Diagnosis is based on clinical appearance and exfoliative cytology findings, which reveal a mixed infiltrate of eosinophils, plasma cells, lymphocytes, mast cells and macrophages (Fig 9).

FIG 9.

Cytology of eosinophilic keratitis, showing a mixed inflammatory infiltrate including neutrophils and bilobed eosinophils. Oil immersion × 100. Courtesy of Karen Dunn, Focus-EyePathLab

A PCR study identified FHV-1 in 76% cases of eosinophilic keratitis, 20 whereas an earlier study using indirect immunofluorescence identified the virus in 33% of cases. 22 The role of FHV-1 in disease pathogenesis is uncertain. The condition is usually responsive to topical corticosteroids without the need for antiviral medication, which may argue against a primary viral cause. The condition is also responsive to oral megestrol acetate at an initial dose of 0.5 mg/kg/day, tapering to every second day and then weekly administration until clinical resolution. 21

Keratoconjunctivitis sicca and tear film instability

FHV-1 infection has been associated with KCS, but it is not known whether this is due to direct effects of the virus on the lacrimal glands or whether KCS develops secondarily to inflammation-induced occlusion of the lacrimal ductules where they open onto the conjunctival surface. 6,23

There is significant variation in virulence between field isolates of the same strain of FHV-1, which may in part explain the variation in severity of clinical signs that is recognised clinically.

In experimentally infected cats, FHV-1 causes significant reductions in both conjunctival goblet cell densities and tear film break-up times that persist beyond apparent clinical improvement. 24 These changes can be expected to lead to tear film instability and qualitative tear film deficits.

Calcific band keratopathy

Corneal stromal calcific mineralisation has been reported in experimentally infected cats treated with subconjunctival corticosteroid injections. 6 It progresses to involve the central corneal stroma in a horizontal band pattern.

Periocular dermatitis

FHV-1 DNA, intranuclear inclusion bodies and herpes virions have been identified in cats suffering from ulcerative dermatitis affecting the periocular skin. 25 Clinically, the lesions consist of vesicles, crusts and ulcers and the condition can be severe in its presentation (Fig 10).

FIG 10.

Periocular and facial dermatitis associated with FHV-1 infection

Anterior uveitis

In humans, HSV-1 is a recognised cause of anterior uveitis. 26 The link between FHV-1 and feline anterior uveitis is less well defined. PCR testing of aqueous humour samples identified FHV-1 DNA in 11 of 44 cats with idiopathic anterior uveitis, suggesting that FHV-1 may be a cause of this condition in cats. 27

Diagnostic testing for FHV-1

Fluorescent antibody testing

Fluorescent antibody testing is performed on conjunctival or corneal tissue. To maximise cell numbers and quality, conjunctival cells should be harvested using a cytobrush. Corneal cells can be collected using a Kimura spatula or the blunt handle end of a scalpel blade. Following application of topical anaesthetic to the sample site, the cytobrush should be gently rolled over the tissue then rolled on to a clean glass slide, air dried and submitted to the testing laboratory. Because most fluorescent antibody tests use fluorescein-conjugated antibody to detect FHV-1 antigen within the submitted tissue, topical fluorescein should be avoided prior to collection. 27

Fluorescent antibody testing has largely been superseded by virus isolation (VI) and PCR testing, although some diagnostic laboratories still offer the service.

Virus isolation

Because VI identifies live virus it has traditionally been accepted as the diagnostic ‘gold standard’ for active infection. Swabs are collected from the conjunctival or corneal surface and then transported in viral transport medium, which is available from commercial testing laboratories. Although topical anaesthetics are often used prior to collection of samples, it should be noted that after 1 h incubation in proparacaine, FHV-1 does not remain infectious, raising the possibility that the use of topical anaesthetics prior to sampling may reduce sensitivity. 28

In primary acute lytic disease, ocular swabs may be submitted in combination with pharyngeal swabs. A disadvantage of VI is the inevitable delay while awaiting viral culture results. This inconvenience, coupled with the fact that PCR testing is more sensitive than either VI or fluoresent antibody testing, 29 means that PCR is probably now the most commonly performed diagnostic test for FHV-1 in the UK.

Polymerase chain reaction

The PCR test identifies FHV-1 by amplifying specific sequences of viral DNA. It has, in theory, 100% specificity and extremely high sensitivity. Various PCR testing protocols have been developed for FHV-1 diagnosis. 29–31 Most are based on DNA amplification of sections of the highly conserved viral thymidine kinase gene.

Conventional (single round) PCR, nested PCR and real-time PCR (a variation of conventional PCR) testing are variously offered by commercial diagnostic testing laboratories. Because of its exquisite sensitivity, nested PCR carries a higher risk of contamination than conventional PCR, and as nested and conventional PCR methods show good correlation, most UK laboratories now offer only conventional or real-time PCR as their standard test for FHV-1. 32

PCR testing can be performed on dry conjunctival or corneal swabs without the need for viral transport medium. As with VI, ocular swabs may be submitted in combination with pharyngeal swabs in primary lytic disease. Commonly, such swabs are taken following application of topical anaesthetic. While this should have no deleterious effect on the viral DNA itself, a study has shown that both topical anaesthetic and fluorescein can significantly reduce the sensitivity of real-time PCR for the diagnosis of human herpesviruses. The authors of that study recommended that either the use of topical anaesthetic or fluorescein be avoided altogether prior to sampling for PCR, or that the ocular surface should be thoroughly rinsed prior to taking swabs. 33

Problems with diagnostic testing.

False-positive results

Diagnostic testing for FHV-1 poses some difficulty because of the relatively high frequency of normal cats that are reported to test positive for FHV-1. Different PCR-based studies have calculated the frequency of such false-positive cases as being between 3% and 49%. 10,34 There are a number of possible reasons for these false-positive cases:

Clinically healthy cats can shed virus in response to pharmacological or physiological stress. 2

Clinically healthy cats may harbour the virus within the cornea and conjunctiva. 4

There is evidence that vaccine virus can itself become latent within, and be reactivated from, the trigeminal ganglia; because PCR tests are unable to differentiate between vaccine and wild-type virus, this gives rise to the possibility that a positive PCR result may reflect vaccine rather than wild-type virus. 35,36

False-negative results

Conversely, a significant number of cats with a high index of suspicion for herpesvirus disease will test negative for FHV-1. Possible reasons for false-negative cases include:

Intermittent viral shedding by infected cats.

Inadequate sample collection or degradation of the DNA sample during transport. To ensure that a sufficient quantity of DNA has been submitted, commercial PCR tests should include a positive control in which a portion of host feline DNA is also PCR-amplified.

Reduced sensitivity of the PCR test. Clearly errors in the laboratory PCR design or protocol may affect sensitivity, but external factors may also be important, such as the effects of topical anaesthetics and topical fluorescein (see text).

Making a diagnosis of FHV-1 ocular disease

Diagnostic testing results must be interpreted with caution as both false-positive and false-negative testing is common (see box above). It is important, therefore, to consider the overall clinical picture when attempting to make a diagnosis of FHV-1 ocular disease in a patient.

Where dendritic corneal ulceration is identified it is possible to make a clinical diagnosis of FHV-1 keratitis based on these pathognomonic signs alone, without the need to perform diagnostic testing. However, for a cat presenting only with conjunctivitis there are a number of potential infectious causes, including FHV-1, Chlamydophila felis, Mycoplasma species and feline calicivirus. 34 To some degree, clinical signs can point towards one infectious cause over another. For example, acute conjunctivitis in the absence of systemic signs is typical of C felis infection. Acute FHV-1 infection, by contrast, is usually associated with signs of upper respiratory tract disease; one epidemiological study concluded that FHV-1 is 2.7 times more likely to be detected in sneezing cats than is C felis. 37 While such statistics clearly should not be over-interpreted, the study is nevertheless a reminder of the importance of considering the overall clinical picture when attempting to make a diagnosis. In practice, a ‘jigsaw’ approach to diagnosis (see right) can be highly valuable.

As both false-positive and false-negative testing is common, it is important to consider the overall clinical picture when attempting to make a diagnosis of FHV-1 ocular disease.

Jigsaw approach to clinical diagnosis

Selecting the optimal treatment protocol

Just as making a clinical diagnosis of herpes-related ocular disease may benefit from a ‘jigsaw’ diagnostic approach, so selecting the best treatment protocol may require a multi-faceted approach tailored to the individual patient and, importantly, its owner. Factors to assess include the stage of infection, severity of clinical disease, financial considerations and owner/patient compliance.

Stage of infection

Acute primary infection

In kittens and adolescent cats exposed to FHV-1 for the first time, ocular signs are usually seen in association with upper respiratory tract disease. In these cases systemic as well as local ocular therapy is indicated. In addition to topical and/or systemic antiviral treatment in severe disease, this should include antibacterial drugs to combat concurrent or secondary bacterial infection.

In some cases, additional supportive therapy may be necessary, such as systemic fluid administration or parenteral feeding.

Recrudescent disease

In adult cats presenting with recrudescent keratitis or conjunctivitis, antiviral drugs are the mainstay of treatment. In addition, because stress is a major aetiological factor in recrudescent disease, an important aim should be to identify and reduce or manage any potential stressors.

Such stressors may include concurrent systemic or topical corticosteroid administration, parturition and lactation, co-infection with other agents, a change of environment or change in normal routine.

Chronic stromal keratitis

In adult cats suffering from chronic stromal keratitis, treatment options are limited. This is because the associated corneal pathology is thought not to be due to a direct viral cytopathic effect but rather is host-induced, as the body mounts a dramatic but ineffective ocular immune response to sequestered corneal antigens.

In theory, anti-inflammatory or immunosuppressive treatment is indicated. However, this runs the very real risk of inducing viral recrudescence, especially if corticosteroid drugs are used. Some clinicians will use topical corticosteroids in combination with prophylactic antivirals in an attempt to minimise the risk of this, but evidence for the effectiveness of this approach is lacking. 4

The use of topical ciclosporin, in combination with antiviral therapy, has also been advocated. 4 However, as this is a powerful immunosuppressant it also carries a theoretical risk of inducing viral reactivation.

The use of topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) has also been investigated. Experimental studies in mouse and rabbit models of herpes keratitis have produced conflicting results, with one study showing that the use of topical NSAIDs exacerbated herpesvirus disease and another showing that it did not exacerbate disease (nor did it lessen disease). 4

Severity of clinical disease

In some cases, especially in recrudescent disease, clinical signs are relatively mild. In these instances treatment may not always be necessary as the disease is usually self-limiting.

Reducing environmental stress is a particularly important management strategy for recrudescent disease. Over-medication can be a significant source of stress in some cats and, in the author's experience, simply reducing or stopping the treatment regime can be sufficient to allow the host immune system to suppress viral reactivation in many cases.

Financial considerations and owner/patient compliance

Antiviral drugs can be expensive and many of the topical formulations require frequent application for maximum efficacy. Clearly these are two factors that will have an impact on therapeutic decision-making.

Antiviral drugs

DNA analogues

The most effective group of anti-herpesvirus drugs are the acyclic nucleoside analogues. These are virostatic, acting via competitive inhibition of DNA polymerase and triggering chain termination of replicating DNA. 38

To become metabolically active, most acyclic nucleosides require phosphorylation by viral thymidine kinase (although some, such as cidofovir, rely only on host thymidine kinases for activation). Following viral thymidine kinase phosphorylation, additional phosphorylation steps occur; these are mediated by host cellular kinases.

A large number of acyclic nucleoside analogue drugs exist, although commercial availability varies between countries (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Selected acyclic nucleoside analogue drugs listed in decreasing order of in vitro efficacy against FHV-1 3,4,38–40,48

| Drug | Mode of action | In vitro efficacy against FHV-1 (ED50, μM) 38–40 | Dosage | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trifluorothymidine (trifluridine, 5FT) | Thymidine analogue | 0.67 | 1% solution topically q4-6h for 21 days |

|

| Ganciclovir | Guanosine analogue | 5.2 | 0.15% gel topically q4-6h for 21 days | No controlled clinical trials reported |

| Idoxuridine | Thymidine analogue | 4.3–6.8 | 0.1% ointment topically q4-6h for 21 days | No controlled clinical trials reported |

| Cidofovir | Cytosine analogue | 11.0 | 0.5% solution topically q12h for 21 days | Controlled clinical trial reported clinical efficacy 42 |

| Famciclovir/penciclovir | Guanosine analogue | 13.9 | 90 mg/kg PO q8h for 21 days | Controlled clinical trial reported clinical efficacy 44 |

| Vidarabine | Adenosine analogue | 21.4 | 3% ointment topically q4-6h for 21 days | No controlled clinical trials reported |

| Aciclovir | Guanosine analogue | 57.9–85.6 | 3% ointment topically q4-6h for 21 days | No controlled clinical trials reported although prospective clinical trial suggested efficacy 48 |

Trifluorothymidine

Also known as trifluridine or 5FT, trifluorothymidine (TFT) shows the most effective in vitro efficacy against FHV-1. As such, it is theoretically the topical antiviral drug of choice. Unfortunately, however, no clinical trials of its use in cats have been reported. 38,39 A 1% topical solution should be used four to six times daily for up to 21 days. In the UK, TFT can only be obtained from eye hospital pharmacies, although in some countries it is available by prescription through a pharmacy. It is relatively expensive and can be irritant in some cats. The bottle should be kept refrigerated after opening.

Ganciclovir

Ganciclovir has recently become available in gel form from UK pharmacies (Virgan; Théa). In vitro studies indicate good efficacy against FHV-1, so this drug is a promising treatment option although clinical trials in cats are currently lacking.

Cidofovir

Cidofovir is used to treat cytomegalovirus retinitis in humans but it also has a wide spectrum of activity against other viruses. Studies have shown it to be effective against FHV-1, both in vitro and in vivo. 40–42 Of particular interest is its apparent long-term antiviral action, the active metabolite of cidofovir possessing an intracellular half-life of 65 h. This appears to be reflected in its therapeutic effects; twice-daily application of 0.5% cido-fovir significantly reduced viral shedding and severity of clinical signs in cats with experimentally induced FHV-1 infection. 42 In some countries topical preparations are available from compounding pharmacies, but in others (including the UK) such compounded preparations are not currently obtainable, to the author's knowledge.

Famciclovir

Famciclovir is the prodrug of penciclovir, and is converted to the active drug following absorption across the gastrointestinal tract. The pharmacokinetics of penciclovir following oral administration of famciclovir in cats appear to be complex, with significant interindividual variability among cats. 43

A recent study evaluated the effects of orally administered famciclovir in cats experimentally infected with FHV-1. The study used high doses of famciclovir (90 mg/kg three times daily for 21 days) and showed that it reduced viral shedding and conjunctivitis scores compared with controls. 44 As one of only two antivirals with proven clinical efficacy against FHV-1 (the other being cidofovir, see above), famciclovir should be considered one of the drugs of choice in the treatment of FHV-1 clinical disease.

Although clinical efficacy of famciclovir has been proven only for doses of 90 mg/kg three times daily, anecdotal reports of efficacy at lower doses (62–125 mg per cat once to three times daily) have been reported. 45

Famciclovir and cidofovir are the only two antivirals with proven clinical efficacy against FHV-1.

Famciclovir is relatively expensive. As it is metabolised by the liver and excreted via the kidneys it may be prudent to monitor liver and kidney function prior to its administration and during the course of treatment.

Aciclovir

Aciclovir is available from medical pharmacies in many countries in topical formulation (Zovirax Eye Ointment; GlaxoSmithKline). It is inexpensive and the topical formulation is well tolerated in cats (systemic aciclovir has been associated with bone marrow suppression and should be avoided in this species). 46

Unfortunately, a number of experimental studies have shown aciclovir to be ineffective against FHV-1 in vitro, 39,40 although its in vitro antiviral activity has been shown to be significantly enhanced when used in combination with alpha interferon. 47

However, despite its poor in vitro efficacy, one prospective clinical trial suggested that topical aciclovir applied five times daily to cats with herpetic keratitis was clinically effective. 48 The author of that study hypothesised that the high drug concentration in the topical 3% formulation was sufficient to provide virostatic potency on the ocular surface.

Interferons

Interferons (IFNs) are cytokines released by host cells in response to viral infection and are known to have wide-ranging antiviral activity. 49 Interferons are classed into two broad groups: type I includes interferon alpha, beta and omega (IFN-α, IFN-β, IFN-ω) and can be produced by most cell types following viral infection; type II is represented by gamma interferon (IFN-γ) and is produced only by certain cells of the immune system, including natural killer cells, CD4+ helper cells and CD8+ cytotoxic T cells.

Type I IFNs hold most promise for the treatment of viral disease. Topical, oral and parenteral routes of administration have been investigated:

Although IFNs are degraded by the gastrointestinal tract and are undetectable in blood following oral dosing, 50 orally administered IFN-α is reported to induce cytokine responses in buccal mucosal lymph nodes in mice, and this may explain why therapeutic responses have been seen following oral administration of IFN in the treatment of various viral diseases of humans and animals. 51–53

However, Mx protein expression (a biological marker of IFN-) is not induced in conjunctival cells following oral administration of IFN- to cats. 54 This implies that oral administration may be ineffective in inducing ocular surface effects in cats.

Topical and oral interferon appears to be ineffective in the treatment of FHV-1 ocular disease.

Specifically regarding IFN use in treating FHV-1 ocular disease, in vitro studies have shown anti-FHV-1 activity for both recombinant human IFN-α and feline IFN-, 47,55,56 suggesting that in vivo trials are warranted. To date, however, such clinical studies are limited and contradictory:

A preliminary study of cats experimentally infected with FHV-1 (published in abstract form only) showed that once-daily oral doses of 25 U human IFN-α early in the course of disease resulted in reduced viral shedding. 57

A later, small study looking at the effects of high dose recombinant feline IFN- given topically (10,000 U q12h) and orally (20,000 U q24h) prior to experimental FHV-1 infection, showed no difference in viral shedding compared with control cats. 58

Anecdotal reports describe the use of topical IFN- diluted in saline to treat FHV-1 ocular disease, and although a small uncontrolled study has been reported in abstract form suggesting improvement in around half of cases treated, 59 no controlled clinical trials have been published. One such formulation suggested is 10 MU IFN- diluted in 19 ml of 0.9% saline and used five times daily for 10 days. 60–62 It is, however, debatable as to whether such formulations would be pharmacologically active due to the inherent instability of IFNs, which are rapidly inactivated and degraded in vitro by denaturation, oxidation and hydrolysis. Formulation of therapeutic proteins such as IFNs poses a particular pharmacological challenge, for this reason. Although a topical dosage delivery system for clinical delivery of human IFN-α has been described, 63 it is not yet commercially available.

Clearly, more clinical trials are warranted in order to assess the efficacy of topical, oral and parenteral administration of feline IFN- and human IFN-α in the treatment of FHV-1 disease.

L-lysine

If data on the effectiveness or not of IFNs is confusing, the situation with respect to L-lysine is even more contradictory. Experimental studies from the 1960s showed that in vitro replication of HSV-1 was inhibited in the presence of high lysine levels. 64 In vitro FHV-1 replication is also inhibited by lysine, but only in the presence of low arginine levels. 65 It was hypothesised that the lysine acted as a competitive inhibitor of arginine during assembly of the viral nucleocapsid. Uncontrolled clinical trials in humans suggested that dietary supplementation of L-lysine, coupled with a low arginine diet, ameliorated clinical symptoms of HSV-1. 66 Unfortunately, because of its status as an essential amino acid in cats, dietary restriction of arginine is not possible in this species and, therefore, studies have instead concentrated simply on lysine supplementation as a prophylactic or therapeutic treatment for FHV-1. The trials have produced mixed results:

The role of vaccination.

FHV vaccines do not necessarily prevent infection but they do reduce the severity of clinical disease, reduce viral shedding and reduce the consequences of viral recrudescence. 62 They provide protection by inducing both humoral and cellular immunity. Both inactivated and modified-live parenteral vaccines are available.

Maternally derived antibodies provide some degree of humoral protection in kittens up to the age of around 8 weeks, and therefore primary vaccination should be instigated at around 9 weeks of age, with a second vaccination 2–4 weeks later. Yearly boosters are recommended in most cats; although, according to the European Advisory Board on Cat Diseases (ABCD guidelines on feline herpesvirus), 3-yearly intervals are acceptable for cats in low risk situations, such as indoor-only cats. 62

A small controlled experimental trial of eight cats showed that lysine supplementation given to half of them prior to infection with FHV-1 led to reduced clinical signs in comparison with the half that was not lysine supplemented. However, VI results did not differ between the two groups. 67

Another small controlled experimental study in 14 FHV-1-infected cats showed that lysine supplementation given to half of them led to a reduction in viral shedding following rehousing in comparison with the half that did not receive lysine. However, there was no difference in severity of clinical signs between the two groups. 68

In a larger study, addition of lysine to the diet of 50 cats with enzootic upper respiratory tract disease actually increased the severity of clinical signs and FHV-1 DNA detection rates. 69

In a large clinical study within an animal shelter (144 treated cats, 147 controls), dietary lysine supplementation did not reduce FHV-1 infection rates in the experimental group compared with the control group. 70

Another large controlled study involving 261 animal shelter cats reached similar conclusions, with lysine-dosed cats developing more severe clinical signs and higher FHV-1 DNA detection rates than control cats. 71

Currently, there is no evidence of the benefit of dietary L-lysine supplementation, and its addition may paradoxically increase disease severity and viral shedding.

There is no evidence of the benefit of dietary L-lysine supplementation, and its addition may paradoxically increase disease severity and viral shedding.

Probiotics

A single pilot study has evaluated the effect of the probiotic Enterococcus faecium SF68 given as an oral supplement to cats with latent FHV-1. 72 This probiotic has previously been reported to possess various immune-enhancing properties when fed to cats. 73 The authors concluded that oral administration of E faecium SF68 lessened morbidity associated with chronic FHV-1 infection in some cats. However, the small study size precluded more definitive conclusions and additional studies are necessary before the benefit of this supplement can be evaluated.

KEY POINTS.

Treatment options for FHV-1 ocular disease should be tailored to the individual patient and owner. Important factors to assess include clinical signs and severity, stage of disease, patient and owner compliance, and financial considerations.

-

The mainstays of therapy for ocular FHV-1 disease include:

— reduction of stress;

— supportive treatment (restoration of fluids, electrolytes and acid-base balance, if indicated; broad spectrum antibacterials to prevent or treat secondary bacterial infections; appropriate nursing care, if indicated);

— topical antiviral agents q4-6h for 21 days (see Table 3);

— systemic antiviral agents (eg, famciclovir 90 mg/kg q8h for 21 days).

L-lysine supplementation appears to be ineffective and may exacerbate clinical disease or viral shedding, according to a series of clinical trials.

Interferon, given orally and topically, appears to be ineffective, although further studies are warranted.

Case notes.

CASE 1

A 3-year-old neutered female domestic shorthair cat is presented for evaluation of a left ocular abnormality.

History The cat is a confirmed FHV-1 carrier (by PCR from a previously taken conjunctival swab) but is otherwise healthy and has no active signs of upper respiratory tract disease. The owner reports that the eye condition was first noticed around 3 weeks previously and that it has gradually progressed since that time.

No signs of ocular discomfort have been noted and the other eye is unaffected.

WHAT IS YOUR ASSESSMENT?

(a) Describe the lesions seen.

(b) What is the most likely diagnosis in this case and how could it be confirmed?

(c) What is the usual treatment for this condition, and what is the concern about instigating such therapy in this particular case?

CASE 2

A 6-year-old neutered female Persian cat is presented for assessment of a painful right eye of 2 weeks’ duration.

History The cat has a history of recurrent right corneal ulceration but has previously tested negative for FHV-1 (by PCR from corneal swabs). However, her sibling housemate is a known FHV-1 carrier (by PCR from a previously taken conjunctival swab).

WHAT IS YOUR ASSESSMENT?

(a) Describe the ocular abnormalities.

(b) What is your diagnosis?

(c) What treatment options should be considered in this case?

Answers and discussion

Case 1 (a) A mild mucopurulent ocular discharge is associated with superficial corneal neovascularisation extending towards multiple areas of discrete white proliferative lesions that appear to be raised from the ocular surface.

(b) The clinical appearance is characteristic of eosinophilic keratitis. Diagnosis can be confirmed by corneal cytology, which should show a mixed inflammatory response including eosinophils.

(c) Eosinophilic keratitis is usually responsive to topical corticosteroids. However, use of corticosteroids in FHV-1 infected cats carries a high risk (70%) of viral reactivation. 2 Treatment options in this case include topical corticosteroids in combination with topical antivirals, or systemic megestrol acetate.

Case 2 (a) Image i shows a mucoid ocular discharge with green staining due to application of topical fluorescein.

The reflection from the tear film reflex on the ocular surface is disrupted and a faint brown discolouration to the cornea is evident. Image ii reveals a relatively large but apparently superficial corneal ulcer surrounded by diffuse corneal oedema, consistent with epithelial underrunning. The central part of the ulcer is faintly brown in colour.

(b) The brown discolouration of the corneal stroma is diagnostic of early corneal sequestrum formation. This is associated with an underrun superficial corneal ulcer. It is likely that recurrent or chronic corneal ulceration has predisposed to the formation of a corneal sequestrum.

(c) The presence of a corneal sequestrum means that the overlying corneal ulcer is unlikely to heal without surgical intervention. Surgical treatment would involve gentle debridement of the underrun epithelium followed by superficial keratectomy to remove the sequestrum. This procedure should be performed under an operating microscope, and additional grafting procedures (eg, conjunctival pedicle graft) may be required following superficial keratectomy.

Although the cat has previously tested negative for FHV-1, the ophthalmic history and the environmental association with a known FHV-1 carrier raise the suspicion that this cat is chronically infected with, and may be currently affected by, FHV-1. Repeat PCR testing or a therapeutic trial with antiviral medications could be considered.

References

- 1. Maggs DJ, Lappin MR, Reif JS, et al. Evaluation of serologic and viral detection methods for diagnosing feline herpesvirus-1 infection in cats with acute respiratory tract or chronic ocular disease. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1999; 214: 502–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gaskell RM, Povey RC. Experimental induction of feline viral rhinotracheitis virus re-excretion in FVR-recovered cats. Vet Rec 1977; 12: 128–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stiles. Feline herpesvirus. Infectious disease and the eye. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2000; 30: 1001–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stiles J, Townsend WM. Feline ophthalmology. In: Gelatt KN, ed. Veterinary ophthalmology, 4th edn. Iowa: Blackwell Publishing, 2007: 1095–164. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gaskell RM, Povey RC. Feline viral rhinotracheitis: sites of virus replication and persistence in acutely and persistently infected cats. Res Vet Sci 1979; 27: 167–74 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nasisse MP, Guy JS, Davidson MG, Sussman WA, Fairley NM. Experimental ocular herpesvirus infection in the cat. Sites of virus replication, clinical features and effects of corticosteroid administration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1989; 30: 1758–68 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gaskell R, Dennis PE, Goddard LE, Cocker FM, Wills JM. Isolation of felid herpesvirus 1 from the trigeminal ganglia of latently infected cats. J Gen Virol 1985; 66: 391–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ohmura Y, Ono E, Matsuura, Kida H, Shimizu Y. Detection of feline herpesvirus 1 transcripts in trigeminal ganglia of latently infected cats. Arch Virol 1993; 129: 341–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bloom DC. HSV-1 latency and the role of the LATs. In: Sandri-Goldin RM, ed. Alpha herpesviruses: molecular and cellular biology. Norwich, UK: Caister Academic Press, 2006: 325–42. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Townsend WM, Stiles J, Guptill-Yoran L, Krohne SG. Development of a reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction assay to detect feline herpesvirus-1 latency-associated transcripts in the trigeminal ganglia and corneas of cats that did not have clinical signs of ocular disease. Am J Vet Res 2004; 65: 314–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Galle LE, Moore CP. Clinical microbiology. In: Gelatt KN, ed. Veterinary ophthalmology. 4th edn. Iowa: Blackwell Publishing, 2007: 236–70. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Maggs DJ, Chang E, Nasisse MP, Mitchell WJ. Persistence of herpes simplex virus type 1 DNA in chronic conjunctival and eyelid lesions of mice. J Virol 1998; 72: 9166–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. English RV. Immune responses and the eye. In: Gelatt KN, ed. Veterinary ophthalmology. 2nd edn. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 1999: 239–58. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lafon M. Latent viral infections of the nervous system: role of the host immune response. Rev Neurol 2009; 165: 1039–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bistner SI, Carlson JH, Shively JN, Scott FW. Ocular manifestations of feline herpesvirus infection. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1971; 159: 1223–37 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nasisse MP, Guy JS, Stevens JB, English RV, Davidson MG. Clinical and laboratory findings in chronic conjunctivitis in cats: 91 cases (1983–1991). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1993; 203: 834–37 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nasisse MP, English RV, Tompkins MB, Guy JS, Sussman W. Immunologic, histologic, and virologic features of herpesvirus-induced stromal keratitis in cats. Am J Vet Res 1995; 56: 51–55 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Morgan RV. Feline corneal sequestration: a retrospective study of 42 cases (1987–1991). J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1994; 30: 24–28 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stiles J, McDermott M, Bigsby D, Willis M, Martin C, Roberts W, Greene C. Use of nested polymerase chain reaction to identify feline herpesvirus in ocular tissue from clinically normal cats and cats with corneal sequestra or conjunctivitis. Am J Vet Res 1997; 58: 338–42 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nasisse MP, Glover TL, Moore CP, Weigler BJ. Detection of feline herpesvirus 1 DNA in corneas of cats with eosinophilic keratitis or corneal sequestration. Am J Vet Res 1998; 59: 856–58 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Allgoewer I, Schaffer EH, Stockhaus C, Vogtlin A. Feline eosinophilic conjunctivitis. Vet Ophthalmol 2001; 4: 69–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Morgan RV, Abrams KL, Kern TJ. Feline eosinophilic keratitis: a retrospective study of 54 cases (1989–1994). Vet Comp Ophthalmol 1996; 6: 131–34 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stiles J. Treatment of cats with ocular disease attributable to herpesvirus infection: 17 cases (1983–1993). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1995; 5: 599–603 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lim CC, Reilly CM, Thomasy SM, Kass PH, Maggs DJ. Effects of feline herpesvirus type 1 on tear film break-up time, Schirmer tear test results, and conjunctival goblet cell density in experimentally infected cats. Am J Vet Res 2009; 70: 394–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hargis AM, Ginn PE, Mansell JEKL, Garber RL. Ulcerative facial and nasal dermatitis and stomatitis in cats associated with feline herpesvirus 1. Vet Dermatol 1999; 10: 267–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Liesegang TJ. Classification of herpes simplex virus keratitis and anterior uveitis. Cornea 1999; 18: 127–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Maggs DJ, Lappin MR, Nasisse MP. Detection of feline herpesvirus-specific antibodies and DNA in aqueous humour from cats with or without uveitis. Am J Vet Res 1999; 60: 932–36 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Storey ES, Gerding PA, Scherba G, Schaeffer DJ. Survival of equine herpesvirus-4, feline herpesvirus-1, and feline calicivirus in multidose ophthalmic solutions. Vet Ophthalmol 2002; 5: 263–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Stiles J, McDermott M, Willis M, Roberts W, Greene C. Comparison of nested polymerase chain reaction, virus isolation, and fluorescent antibody testing for identifying feline herpesvirus in cats with conjunctivitis. Am J Vet Res 1997; 58: 804–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hara M, Fukuyama M, Suzuki Y, et al. Detection of feline herpesvirus 1 DNA by the nested polymerase chain reaction. Vet Microbiol 1996; 48: 345–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Helps C, Reeves N, Egan K, Howard P, Harbour D. Detection of Chlamydophila felis and feline herpesvirus by multiplex realtime PCR analysis. J Clin Microbiol 2003; 41: 2734–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Volopich S, Benetka V, Schwendenwein I, Mostl K, Sommerfeld-Stur I, Nell B. Cytological findings, and feline herpesvirus DNA and Chlamydophila felis antigen detection rates in normal cats and cats with conjunctival and corneal lesions. Vet Ophthalmol 2005; 8: 25–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Goldschmidt P, Rostane H, Sain-Jean C, et al. Effects of topical anaesthetics and fluorescein on the real-time PCR used for the diagnosis of herpesviruses and Acanthamoeba keratitis. Br J Ophthalmol 2006; 90: 1354–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Low HC, Powell CC, Veir JK, Hawley JR, Lappin MR. Prevalence of feline herpesvirus 1, Chlamydophila felis and Mycoplasma spp DNA in conjunctival cells collected from cats with and without conjunctivitis. Am J Vet Res 2007; 68: 643–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Weigler BJ, Guy JS, Nasisse MP, Hancock SI, Sherry B. Effect of a live attenuated intranasal vaccine on latency and shedding of feline herpesvirus 1 in domestic cats. Arch Virol 1997; 142: 2389–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Maggs DJ, Clarke HE. Relative sensitivity of polymerase chain reaction assays used for detection of feline herpesvirus type 1 DNA in clinical samples and commercial vaccines. Am J Vet Res 2005; 66: 1550–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sykes JE, Anderson GA, Studdert VP, Browning GF. Prevalence of feline Chlamydia psittaci and feline herpesvirus 1 in cats with upper respiratory tract disease. J Vet Intern Med 1999; 13: 153–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Galle LE. Antiviral therapy for ocular viral disease. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2004; 34: 639–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nasisse MP, Guy JS, Davidson MG, Sussman W, De Clercq E. In vitro susceptibility of feline herpesvirus-1 to vidarabine, idoxuridine, trifluridine, acyclovir, or bromovinyldeoxyuridine. Am J Vet Res 1989; 50: 158–60 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Maggs DJ, Clarke HE. In vitro efficacy of ganciclovir, cidofovir, penciclovir, foscarnet, idoxuridine, and acyclovir against feline herpesvirus type-1. Am J Vet Res 2004; 65: 399–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sandmeyer LS, Keller CB, Bienzle D. Effects of cidofovir on cell death and replication of feline herpesvirus-1 in cultured feline corneal epithelial cells. Am J Vet Res 2005; 66: 217–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fontenelle JP, Powell CC, Veir JK, Radecki. Effect of topical ophthalmic application of cidofovir on experimentally induced primary ocular feline herpesvirus-1 infection in cats. Am J Vet Res 2008; 69: 289–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Thomasy SM, Maggs DJ, Moulin NK, Stanley SD. Pharmacokinetics and safety of penciclovir following oral administration of famciclovir to cats. Am J Vet Res 2007; 68: 1252–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Thomasy SM, Lim CC, Reilly CM, Kass PH, Lappin MR, Maggs DJ. Evaluation of orally administered famciclovir in cats experimentally infected with feline herpesvirus type-1. Am J Vet Res 2011; 72: 85–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Malik R, Lessels NS, Webb S, et al. Treatment of feline herpesvirus-1 associated disease in cats with famciclovir and related drugs. J Feline Med Surg 2009; 11: 40–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hartley C. Treatment of corneal ulcers. What are the medical options? J Feline Med Surg 2010; 12: 383–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Weiss RC. Synergistic antiviral activities of acyclovir and recombinant huma leucocyte (alpha) interferon on feline herpesvirus replication. Am J Vet Res 1988; 50: 1672–77 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Williams DL, Robinson JC, Lay E, Field H. Efficacy of topical aciclovir for the treatment of feline herpetic keratitis: results of a prospective clinical trial and data from in vitro investigations. Vet Rec 2005; 157: 254–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Katze MG, He Y, Gale M. Viruses and interferon: a fight for supremacy. Nat Rev Immunol 2002; 2: 675–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Cantell K, Pyhäla L. Circulating interferon in rabbits after administration of human interferon by different routes. J Gen Virol 1973; 20: 97–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tompkins WA. Immunomodulation and therapeutic effects of the oral use of interferon-alpha: mechanism of action. J Interferon Cytokine Res 1999; 19: 817–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Dec M, Puchalski A. Use or oromucosally administered interferon-α in the prevention and treatment of animal diseases. Pol J Vet Sci 2008; 11: 175–86 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Cummins JM, Krakowka GS, Thompson CG. Systemic effects of interferons after oral administration in animals and humans. Am J Vet Res 2005; 66: 164–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bracklein T, Theise S, Metzler A, Spiess BM, Richter M. Activity of feline interferon-omega after ocular or oral administration in cats as indicated by Mx protein expression in conjunctival and white blood cells. Am J Vet Res 2006; 67: 1025–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Siebeck N, Hurley DJ, Garcia M, et al. Effects of human recombinant alpha-2b interferon and feline recombinant omega interferon on in vitro replication of feline herpesvirus-1. Am J Vet Res 2006; 67: 1406–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sandmeyer LS, Keller CB, Bienzle D. Effects of interferonalpha on cytopathic changes and titers for feline herpesvirus-1 in primary cultures of feline corneal epithelial cells. Am J Vet Res 2005; 66: 210–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Nasisse MP, Halenda RM, Luo H. Efficacy of low dose oral, natural human interferon alpha in acute feline herpesvirus-1 (FHV-1) infection: a preliminary dose determination trial. Trans Am Coll Vet Ophthalmol 1996; 27: 79 [Google Scholar]

- 58. Haid C, Kaps S, Gönczi E, et al. Pretreatment with feline interferon omega and the course of subsequent infection with feline herpesvirus in cats. Vet Ophthalmol 2007; 10: 278–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Verneuil M. Topical application of feline interferon omega in the treatment of herpetic keratitis in the cat: preliminary study. Vet Ophthalmol 2004; 7: 427 [Google Scholar]

- 60. Jongh O. A cat with herpetic keratitis (primary stage of infection) treated with feline omega interferon. In: de Mari K. (ed). Veterinary interferon handbook. Carros: Virbac, 2004: 138–42. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Jongh O. A cat with a relapse of herpetic keratitis treated with feline omega interferon. In: de Mari K. (ed). Veterinary interferon handbook. Carros: Virbac, 2004: 143–477. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Thiry E, Addie D, Belák S, et al. Feline herpesvirus infection. ABCD guidelines on prevention and management. J Feline Med Surg 2009; 11: 547–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kumar P, Batta R, LaBine G, et al. Stabilization of interferon alpha-2b in a topical cream. Pharm Tech 2009; 33: 80–86 [Google Scholar]

- 64. Tankersley RW. Amino acid requirements of herpes simplex virus in human cells. J Bacteriol 1964; 87: 609–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Maggs DJ, Collins BK, Thorne JG, Nasisse MP. Effects of L-lysine and L-arginine on in vitro replication of feline herpesvirus type-1. Am J Vet Res 2000; 61: 1474–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Griffith RS, Norins AL, Kagan C. A multicentered study of lysine therapy in herpes simplex infection. Dermatologica 1978; 156: 257–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Stiles J, Townsend WM, Rogers QR, Krohne SG. Effect of oral administration of L-lysine on conjunctivitis caused by feline herpesvirus in cats. Am J Vet Res 2002; 63: 99–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Maggs DJ, Nasisse MP, Kass PH. Efficacy of oral supplementation with L-lysine in cats latently infected with feline herpesvirus. Am J Vet Res 2003; 64: 37–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Maggs DJ, Sykes JE, Clarke HE, et al. Effects of dietary lysine supplementation in cats with enzootic upper respiratory disease. J Feline Med Surg 2007; 9: 97–108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Rees TM, Lubinski JL. Oral supplementation with L-lysine did not prevent upper respiratory infection in a shelter population of cats. J Feline Med Surg 2008; 10: 510–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Drazenovich TL, Fascetti AJ, Westermeyer HD, et al. Effects of dietary lysine supplementation on upper respiratory and ocular disease and detection of infectious organisms in cats within an animal shelter. Am J Vet Res 2009; 70: 1391–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Lappin MR, Veir JK, Satyaraj E, Czarnecki-Maulden G. Pilot study to evaluate the effect of oral supplementation of Enterococcus faecium SF68 on cats with latent feline herpesvirus 1. J Feline Med Surg 2009; 11: 650–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Veir JK, Knorr R, Cavadini C, et al. Effect of supplementation with Enterococcus faecium (SF68) on immune functions in cats. Vet Ther 2007; 8: 229–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]