Abstract

The study sought to examine the effect of long-term meloxicam treatment on the survival of cats with and without naturally-occurring chronic kidney disease at the initiation of therapy. The databases of two feline-only clinics were searched for cats older than 7 years that had been treated continuously with meloxicam for a period of longer than 6 months. Only cats with complete medical records available for review were recruited into the study.The median longevity in the renal group was 18.6 years [95% confidence interval (CI) 17.5–19.2] and the non-renal group was 22 years [95% CI 18.5–23.8]. The median longevity after diagnosis of CKD was 1608 days [95% confidence interval 1344–1919] which compares favourably to previously published survival times of cats with CKD. In both groups the most common cause of death was neoplasia. Long-term treatment with oral meloxicam did not appear to reduce the lifespan of cats with pre-existent stable CKD, even for cats in IRIS stages II and III. Therefore, to address the need for both quality of life and longevity in cats with chronic painful conditions, meloxicam should be considered as a part of the therapeutic regimen.

Introduction

Chronic painful conditions such as degenerative joint disease (DJD) are common in the aged cat.1–5 These conditions often affect the quality of life of cats and require medical treatment. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) remain the most common pharmaceuticals used to treat pain and inflammation in humans, horses and dogs. Meloxicam is licensed for chronic therapy in the European Union, Switzerland, Australia and New Zealand, and is currently the only NSAID licensed for the long-term treatment of chronic pain in cats.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is very common in aged cats,6–9 and thus many cats with DJD also have CKD. Renal function is partially dependent on prostaglandins, which regulate vascular tone (and therefore intra-renal blood flow), and electrolyte and water homeostasis. The risk of renal damage following NSAID use is considered to be highest in animals that have concurrent hypovolaemia or hypotension as such patients are dependent on locally produced prostaglandins to maintain renal perfusion. For this reason, CKD is listed as a contraindication or warning on all NSAID data sheets. However, there is no evidence to indicate that well hydrated cats with CKD are more dependent on renal prostaglandins to maintain renal perfusion than normal healthy cats. Furthermore, experimental studies in normal healthy cats have shown that some NSAIDs are not inherently nephrotoxic, even at high doses. 10

This presents a challenge to practitioners who wish to improve the quality of life (QoL) for cats with both painful conditions and CKD.

Building on the earlier work of Gunew et al, 11 Gowan et al 12 examined the effects of long-term meloxicam administration on renal function in cats, with and without pre-existing CKD, using a group of age- and International Renal Interest Society (IRIS)-matched control cats from the same clinic. This study concluded that long-term therapy with meloxicam (median daily dose 0.02 mg/kg) can be administered safely to aged cats with CKD, provided they are clinically stable and monitored carefully. The results further suggested that meloxicam may actually slow the progression of renal disease in cats with both DJD and CKD, by either direct or indirect mechanisms. A limitation of that study, however, was the absence of long-term survival data. The objective of this follow-up article was to document the effect of long-term oral meloxicam therapy on the longevity of aged cats with or without naturally-occurring overt CKD. To increase the number of patients available for examination the study was extended to a second feline-only practice, in addition to the clinic that conducted the preliminary work. 12

Materials and methods

The computer databases of the original feline-only clinic in Melbourne (The Cat Clinic; Ciderhouse Veterinary Software) and the additional Sydney feline-only hospital (Paddington Cat Hospital; Practice Pro Professional Office Software) were searched for cats older than 7 years that had been treated continuously with meloxicam (Metacam oral suspension 1.5 or 0.5 mg/ml) administered once daily for a period of longer than 6 months, with complete medical records available for review. In addition, cats were required to have a good body condition score (≥5 on a scale of 0–9) 13 and have diligent owners. The period of data collection ran from 1998 to 2011. Data collection was finalised on 31 March 2011. Patients were treated by the first four authors (RG, RB, AL, MC). Concurrent medications were not restricted unless the use of the drug with meloxicam was thought to be contraindicated, for example prednisolone.

Cats (n = 34) from Gowan et al 12 were included in this analysis by following their progress for a longer time frame (16 from the renal group; 18 from the non-renal group). Four cats were lost to follow-up. Cats were subdivided into two groups on the basis of whether CKD was evident prior to treatment (renal group) or not (non-renal group). The presence or absence of renal disease was determined in cats by considering physical and sonographic findings, serum or plasma creatinine concentrations, urinary protein to creatinine ratio (UPC) determinations and urine-specific gravity (USG) measurements determined using a species-specific (feline) refractometer. Serum creatinine concentration and USG were considered in the assessment of CKD staging according to guidelines developed by IRIS (Table 1).

Table 1.

IRIS staging guidelines

| IRIS stage | Clinical features | Creatinine and urine specific gravity (USG) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Inadequate urine concentrating ability in the absence of azotaemia | Creatinine <140 µmol/l; USG <1.038 |

| 2 | Mild clinical signs associated with CKD | Creatinine 140–250 µmol/l; USG <1.030 |

| 3 | Many clinical signs of CKD | Creatinine 251–440 µmol/l; USG <1.020 |

Both practices managed cats with CKD in similar ways, utilising: (i) canned and dry ‘prescription’ kidney diets (Hill’s or Royal Canin); (ii) control of hypertension (using amlodipine); (iii) treatment of serious periodontal disease (extractions, scaling, polishing and antimicrobials); (iv) control of persistent hyperphosphataemia if patients with IRIS stage 2 CKD had serum phosphate levels greater than 1.6 mmol/l or IRIS stage 3 and phosphate levels greater than 1.8 mmol/l; and (v) eradication of urinary tract infections (UTI), as required. All cats had initial urinary protein estimations by both reagent strips (in house) and quantitative UPC determinations (Idexx Laboratories). Patients were only considered to have sufficiently stable CKD to commence meloxicam therapy if there was no progression of clinical signs and minimal creatinine changes over time (a trend of less than 10–15% over a 1–2-month period) and concurrent disease conditions (eg, hypertension, UTI, periodontal disease) were considered well controlled.

The age of the cats at the start of treatment, median meloxicam dose at start of treatment, median treatment duration and median final maintenance dose of meloxicam were all calculated using a commercial software program (SAS System; SAS Institute). The survival time of cats was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier (KM) method. The time until death was censored at the date of study discontinuation or at the end of the study (31 March 2011) for cats which were still alive at this time point. In addition, survival of cats in the renal group from the point of diagnosis of CKD was estimated using the KM method and compared with the published longevity of cats with CKD (using historical control data available from the literature).14,15 The primary cause of death or euthanasia (if applicable) was recorded by the attending veterinarian.

Results

A total of 82 cats met the stringent inclusion criteria. Of these, 47 had CKD diagnosed before treatment with meloxicam, while overt CKD was not evident in the remaining 35 cats. No cats with significantly elevated UPC (>0.4) at enrolment were included. Table 2 provides a comparison of the groups at enrolment and at the completion of the data collection period. The median treatment dose throughout was 0.02 mg/kg in both groups. Cats with CKD had, on average, shorter survival and, therefore, treatment duration than cats that did not have CKD at the time of enrolment.

Table 2.

Comparison of the groups at enrolment and end of data collection

| Group | Renal | Non-renal |

|---|---|---|

| Total number of cats | 47 | 35 |

| IRIS stage 1 (number of cats) at enrolment | 14 | 0 |

| IRIS stage 2 (number of cats) at enrolment | 28 | 0 |

| IRIS stage 3 (number of cats) at enrolment | 5 | 0 |

| IRIS stage 0 (number of cats) end of data collection | 0 | 10 |

| IRIS stage 1 (number of cats) end of data collection | 7 | 7 |

| IRIS stage 2 (number of cats) end of data collection | 27 | 13 |

| IRIS stage 3 (number of cats) end of data collection | 7 | 3 |

| IRIS stage 4 (number of cats) end of data collection | 6 | 2 |

| Median age at start of treatment [range] (years) | 15.4 [7.8–19.0] | 16.6 [8.0–22.1] |

| Median starting daily dose of meloxicam [range] (mg/kg) | 0.02 [0.01–0.05] | 0.02 [0.01–0.05] |

| Median steady state [final] daily meloxicam dose [range] (mg/kg) | 0.02 [0.01–0.06] | 0.02 [0.01–0.05] |

| Median duration of treatment (days) | 852 [95% CI: 641–1129] | 1866 [95% CI: 653–1970] |

| Median longevity (life-span) (years) | 18.6 [95% CI: 17.5–19.2] | 22 [95% CI: 18.5–23.8] |

| Median longevity after diagnosis of CKD (days) | 1608 [95% CI 1344–1919] | N/A |

| Death or euthanasia attributed to CKD (number of cats) | 3 | 2 |

| Death or euthanasia attributed to non-renal causes (number of cats) | 25 | 12 |

CI = confidence interval

Figure 1 shows the calculated survival time of cats with CKD at the time of enrolment, calculated from the day of diagnosis of CKD to death or the final day of data collection by the KM method. The primary cause of death or euthanasia recorded by the clinician for both groups is documented in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Longevity in cats with chronic kidney disease treated with meloxicam using Kaplan-Meier plots

Figure 2.

Primary cause of death or euthanasia recorded in the renal and non-renal groups (CHF = congestive heart failure, CKD = chronic kidney disease, GI = gastrointestinal, RTA = road traffic accident)

Discussion

Data has already been provided in relation to the safety and efficacy of meloxicam given for treatment periods of less than 6 months 11 and the effect of long-term meloxicam therapy on renal analytes. 12 The principal aim of the present retrospective study was, therefore, to determine the effect of long-term meloxicam on survival of cats with naturally-occurring stable CKD that was evident prior to starting treatment.

Meloxicam therapy was started using a median dose of 0.02 mg/kg (range 0.01–0.05). This is approximately 40% of the manufacturer’s registered dose. Based on a risk:benefit perception and response to therapy, the dose was titrated downwards or upwards to the lowest effective dose, as assessed by owner observations of the cat’s behaviour in its home environment.

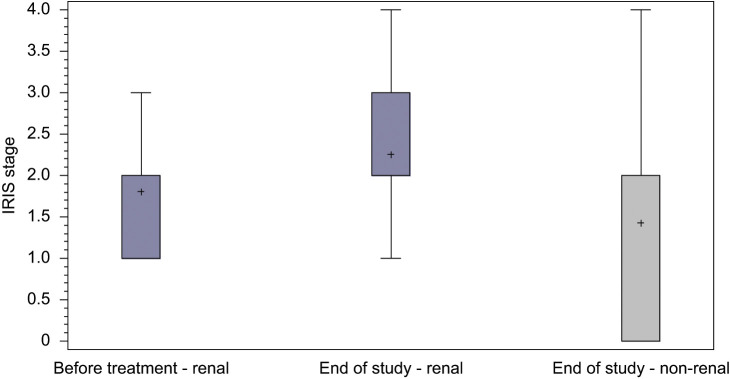

CKD is very common in cats and its prevalence is considered to increase with age. It was presumed that many aged cats in the non-renal group may actually have initially had subclinical CKD and, indeed, in 25 of these cats, CKD became overt during the observation period (median 1866 days, range 653–1970) (see Table 2 and Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Number of cats in each IRIS stage at enrolment and end of data collection

As one would expect, cats with CKD had, on average, a shorter survival than cats that did not have CKD at the time of enrolment. However, perhaps because of diligent management, cats with CKD had prolonged survival (median survival 1608 days). This is important information for veterinarians managing feline patients with CKD because one of the critical factors listed by owners as important regarding the decision whether to euthanase an animal was ‘poor prognosis’ given by the attending veterinarian. 16

Human patients with CKD are more likely to die of cardiac failure than from progression of established renal disease.17,18 To our knowledge, there are no published studies which investigate the actual cause of death in a group of cats with established CKD. The majority of cats in this study (62%) had a variety of co-morbidities (most commonly hypertension and hyperthyroidism) for which they received concurrent medications (96%), and this may have impacted on longevity. The most common cause of death in both the renal and non-renal groups was neoplasia (Figure 2). DJD is a progressive disease, therefore, over time, the daily administered dose of meloxicam was increased and/or other treatment modalities, such as glucosamine, chondroitin, pentosan polysulphate, gabapentin or tramadol, were added based upon individual risk:benefit assessments for each cat. Despite the aggressive multi-modal treatment regimen, 28% of cats were eventually euthanased because of progression of their underlying joint disease.

It is generally recognised that owners value QoL over quantity of life. Furthermore, according to Reynolds et al 19 a majority of cat owners (93%) would actually trade longevity for increased QoL. There is no validated metric for measuring QoL in cats, although aspects of quality of life considered most important to pet owners include pain control, pet–owner interaction and mobility.19–21 Meloxicam is the only molecule registered for long-term pain relief in cats and studies have shown that it improves QoL measures such as mobility,22,23 demeanour 11 and activity, grooming and temperament.23,24 Ideally, treatment of disease processes in older cats would provide increases in both QoL and longevity. Treatment with meloxicam does not appear to impact longevity negatively, as it does not reduce survival times of cats with CKD (median 1608 days in this study) when compared with previously published values reported in studies by King et al 14 (mean survival time 637 ± 480 days; median calculated manually from KM graph 560 days) or Boyd et al 15 [IRIS 2b median 1151 (2–3107) days].

In conclusion, the survival data presented here confirm that many cats with carefully managed CKD can survive for a substantial period with standard medical therapy. In addition, long-term treatment with oral meloxicam does not appear to reduce the longevity of cats with pre-existent stable CKD, even for cats in IRIS stages II and III. Therefore, to address the need for both longevity and QoL in cats with chronic painful conditions, with or without overt stable CKD, meloxicam should be considered as part of the therapeutic regimen.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Stacey Frankcombe, Dr Leah Puk and Georgia Puttock for help with data collection.

Footnotes

Funding: Boehringer Ingelheim recompensed both practices for the time taken to collect the data.

Laura Johnston and Wibke Stansen are employees of Boehringer Ingelheim.

Accepted: 16 June 2012

References

- 1. Hardie EM, Roe SC, Martin FR. Radiographic evidence of degenerative joint disease in geriatric cats: 100 cases (1994–1997). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2002; 220: 628–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Clarke SP, Mellor D, Clements DN, Gemmill T, Farrell M, Carmichael S, Bennett D. Prevalence of radiographic signs of degenerative joint disease in a hospital population of cats. Vet Rec 2005; 157: 793–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Godfrey DR. Osteoarthritis in cats: a retrospective radiological study. J Small Anim Pract 2005; 46: 425–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lascelles BD, Robertson SA. DJD-associated pain in cats: what can we do to promote patient comfort? J Feline Med Surg 2010; 12: 200–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lascelles BD. Feline degenerative joint disease. Vet Surg 2010; 39: 2–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dibartola SP, Rutgers HC, Zack PM, Tarr MJ. Clinicopathologic findings associated with chronic renal disease in cats: 74 cases (1973–1984). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1987; 190: 1196–1202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lulich JP, Osborne CA, O’Brien TD, Polzin DJ. Feline renal failure: questions, answers, questions. Comp Contin Educ Pract 1992; 14: 127–152. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Elliott J, Barber PJ. Feline chronic renal failure: clinical findings in 80 cases diagnosed between 1992 and 1995. J Small Anim Pract 1998; 39: 78–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. White JD, Norris JM, Baral RM, Malik R. Naturally-occurring chronic renal disease in Australian cats: a prospective study of 184 cases. Aust Vet J 2006, 84: 188–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Metacam® EPAR. Scientific discussion, http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Scientific_Discussion/veterinary/000033/WC500065773.pdf (2010, accessed 12 April 2012).

- 11. Gunew MN, Menrath VH, Marshall RD. Long-term safety, efficacy and palatability of oral meloxicam at 0.01-0.03 mg/kg for treatment of osteoarthritic pain in cats. J Feline Med Surg 2008; 10: 235–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gowan R, Lingard A, Johnston L, Stansen W, Brown S, Malik R. Retrospective case-control study of the effects of long-term dosing with meloxicam on renal function in aged cats with degenerative joint disease. J Feline Med Surg 2011; 13: 752–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. LaFlamme DP, Kealy RD, Schmidt DA. Estimation of body fat by body condition score. J Vet Intern Med 1994; 8: 154. [Google Scholar]

- 14. King JN, Gunn-Moore DA, Tasker S, Gleadhill A, Strehlau G; Benazepril in renal insufficiency in Cats Study Group. Tolerability and efficacy of benazepril in cats with chronic kidney disease. J Vet Intern Med 2006; 20: 1054–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Boyd LM, Langston C, Thompson K, Zivin K, Imanishi M. Survival in cats with naturally occurring chronic kidney disease (2000–2002). J Vet Intern Med 2008; 22: 1111–1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mallery KF, Freeman LM, Harpster NK, Rush JE. Factors contributing to the decision for euthanasia of dogs with congestive heart failure. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1999; 214: 1201–1204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. NICE. NICE Clinical Guideline 73. Chronic kidney disease. 2008: NICE [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ruggenenti P, Perna A, Gherardi G, Gaspari F, Benini R, Remuzzi G. Renal function and requirement for dialysis in chronic nephropathy patients on long-term ramipril: REIN follow-up trial. Gruppo Italiano di Studi Epidemiologici in Nefrologia (GISEN). Ramipril Efficacy in Nephropathy. Lancet 1998; 17: 1252–1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Reynolds CA, Oyama MA, Rush JE, Rozanski EA, Singletary GE, Brown DC, et al. Perceptions of quality of life and priorities of owners of cats with heart disease. J Vet Intern Med 2010; 24: 1421–1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tzannes S, Hammond MF, Murphy S, Sparkes A, Blackwood L. Owners perceptions of their cats quality of life during COP chemotherapy for lymphoma. J Feline Med Surg 2008; 10: 73–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pittari J, Rodan I, Beekman G, Gunn-Moore D, Polzin D, Taboada J, et al. American Association of Feline Practitioners. Senior care guidelines. J Feline Med Surg 2009; 11: 763–778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lascelles BD, Hansen BD, Roe S, DePuy V, Thomson A, Pierce CC, et al. Evaluation of client-specific outcome measures and activity monitoring to measure pain relief in cats with osteoarthritis. J Vet Intern Med 2007; 21: 410–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Clarke SP, Bennett D. Feline osteoarthritis: a prospective study of 28 cases. J Small Anim Pract 2006; 47: 439–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bennett D, Morton C. A study of owner observed behavioural and lifestyle changes in cats with musculoskeletal disease before and after analgesic therapy. J Feline Med Surg 2009; 11: 997–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]