Abstract

Mitochondrial dysfunction and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) play important roles in cancer development and metastasis. However, very little is known about the connection between mitochondrial dysfunction and EMT. Tu translation elongation factor, mitochondrial (TUFM), a key factor in the translational expression of mitochondrial DNA, plays an important role in the control of mitochondrial function. Here, we show that TUFM is downregulated in human cancer tissues. TUFM expression level was positively correlated with that of E-cadherin and decreased significantly during the progression of human lung cancer. TUFM knockdown induced EMT, reduced mitochondrial respiratory chain activity, and increased glycolytic function and the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Mechanistically, TUFM knockdown activated AMPK and phosphorylated GSK3β and increased the nuclear accumulation of β-catenin, leading to the induction of EMT and increased migration and metastasis of A549 lung cancer cells. Although TUFM knockdown also induced EMT of MCF7 breast cancer cells, the underlying mechanism appeared somewhat different from that in lung cancer cells. Our work identifies TUFM as a novel regulator of EMT and suggests a molecular link between mitochondrial dysfunction and EMT induction.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00018-015-2122-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: EMT, AMPK, ROS, TUFM, Signaling, Lung cancer

Introduction

Mitochondria play essential roles in oxidative metabolism and various other cellular processes and mitochondrial dysfunction has been implicated in many human diseases, including cancers [1, 2]. The activities and expression levels of mitochondrial respiratory chain enzymes are downregulated in many types of cancer and a high mutation rate in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and nuclear genes encoding mitochondrial proteins has been reported [3, 4]. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is an important process that contributes to cancer metastasis. Cancer cells can detach from the primary tumor and intravasate into lymph or blood vessels through EMT. Moreover, EMT can endow cells with the ability to resist anoikis, senescence, and immune defense [5]. EMT can be induced by many factors including oxidative and hypoxic stresses [6–8]. Interestingly, both oxidative and hypoxic stresses are highly linked to mitochondrial dysfunction. It has also been reported that a decrease in the content of mtDNA in human breast cancer cells induces EMT [9]. Mitochondrial pyrimidine nucleotide carrier 1 (PNC1), which controls mitochondrial DNA replication and the transcriptional ratio of mitochondrial genes relative to nuclear genes, has been shown to be involved in the regulation of EMT through a reactive oxygen species (ROS)-dependent pathway [10]. Recent reports of suppression of mitochondrial respiration by transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) and Wnt/Snail and the involvement of mitochondrial dysfunction in aldosterone-induced EMT in renal tubular epithelial cells suggest that mitochondrial dysfunction and EMT are closely linked biological processes [11–13]. However, whether mitochondrial dysfunction directly contributes to the induction of EMT and the mechanism underlying EMT regulation remain largely unknown.

Mitochondria possess their own genome and highly specialized transcription, translation, and protein-assembly machineries. It is well known that mtDNA-encoded proteins are essential components of the mitochondrial respiratory complexes. TUFM is a nuclear gene-encoded protein that is critical for mitochondrial respiratory function. It is a key factor for the translation of mitochondrial genes, which controls the amino acid elongation of mtDNA-encoded peptides [14]. The protein levels of TUFM were found to be decreased during TGF-β1-induced EMT and apoptosis [15]. However, whether TUFM plays an important role in regulating EMT and the invasive/metastatic potential of cancer cells remains unknown. In this study, we investigated the regulatory effect of TUFM on EMT and the implications of this effect in lung cancer. Our results indicate that TUFM is essential for maintaining the epithelial phenotype of human lung cancer cells. Downregulation of TUFM reduced mitochondrial respiratory chain activity and increased ROS production, which induced EMT and the migration and invasion of lung cancer cells via a mechanism involving activation of the AMPK-GSK3β/β-catenin pathway.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

A549, CCL64, NCI-H446, MCF7, MDA-MB-453, MDA-MB-231 and 293T cells were originally purchased from the American Type Culture Collection. A549, MDA-MB-453, MDA-MB-231, and 293T cells were cultured in DMEM (Thermo Scientific HyClone) containing 10 % FBS supplemented with penicillin (100 units/ml) and streptomycin (100 mg/ml; Life Technologies Gibco). NCI-H446 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Thermo Scientific Hyclone) containing 10 % FBS supplemented with penicillin (100 units/ml) and streptomycin (100 mg/ml). MCF7 cells were cultured in DMEM containing 10 % FBS supplemented with penicillin (100 units/ml), streptomycin (100 mg/ml) and insulin (0.01 mg/ml; Sigma). CCL64 cells were cultured in MEM (Thermo Scientific Hyclone) containing 10 % FBS supplemented with penicillin (100 units/ml), streptomycin (100 mg/ml) and non-essential amino acids. All cells were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5 % CO2.

Reagents and antibodies

Human recombinant TGF-β1 was purchased from Chemi-Con. The antibody against TUFM (#AP2918a) was purchased from Abgent. The antibody against ZO-1 (#339100) was purchased from Invitrogen. Antibodies against E-cadherin (#610182), N-cadherin (#610921) and γ-catenin (#610254) were obtained from BD Biosciences. Antibodies against vimentin (#sc-53464), actin (#sc-47778), PARP (#sc-25780), tubulin (#sc-55529) and β-catenin (#sc-7693) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Antibodies against ACC (#3676), p-ACC (S79) (#3661), AMPKα (#2532), p-AMPKα (T172) (#2535s), GSK3β (#9315), p-GSK3β (S9) (#9323), LC3 (#3868) and snail (#3895) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. The antibody against fibronectin (#F3648), the N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) and Compound C were purchased from Sigma.

Cell migration assays

Wound-healing and transwell assays were performed as described previously [16].

Colony formation in soft agar

The base agar was made by mixing equal volumes of 1.2 % agar and 2× DMEM. The top agar was made by mixing equal volumes of 0.6 % agar and 2 × DMEM. Then, 1 × 104 cells were seeded in the top agar of each dish. Clones were counted after 2 weeks.

Cell cycle analysis

Cells were trypsinized, suspended in PBS, and fixed with 1 ml of 70 % ethanol overnight at −20 °C. After centrifugation, cells were resuspended in 500 μl of PBS and digested with RNase A (0.1 mg/ml) for 1 h at 37 °C. Cells were then stained with PI (0.1 mg/ml) for 30 min at room temperature and protected from light. The DNA content of cells was measured using flow cytometry (Becton–Dickinson FACSCalibur).

BrdU cell proliferation assay

Cell proliferation was examined using a BrdU cell proliferation assay kit (Cell Signaling Technology) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

shRNAs and plasmids

shRNAs were inserted into the pLKO.1-TRC plasmid following the Addgene instructions. The following shRNA sequences were used to target human TUFM: 5′-CAGCCAATGATCTTAGAGAAA-3′; 5′-GCTCACCGAGTTTGGCTATAA-3′. The following shRNA sequences were used to target human β-catenin: 5′-AAGCCACAAGATTACAAGAAA-3′; 5′-AAGTGAAGAATGCACAAGAAT-3′. The following shRNA sequence was used to target human AMPKα: 5′-AACTATGCTGCACCAGAAGTA-3′. The scrambled shRNA sequence used is 5′-CCTAAGGTTAAGTCGCCCTCG-3′.

Western blotting and immunofluorescent staining

Western blotting and immunofluorescent staining were performed as previously described [17].

Lentiviral transduction

Lentiviruses for gene knockdown were produced as previously described [18].

Measurement of mRNA by real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cells using TRIzol reagent (Tiangen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. mRNA was reverse transcribed for 30 min at 42 °C using ReverTra Ace (Toyobo) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Real-time PCR was performed using qPCR SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Vazyme) with an Applied Biosystems 7500 Fast Real-time PCR system. The following primers were used:

| Forward (5′–3′) | Reverse (5′–3′) | |

|---|---|---|

| GLUT1 | TCTGGCATCAACGCTGTCTTC | CGATACCGGAGCCAATGGT |

| GLUT4 | TGGGCGGCATGATTTCCTC | GCCAGGACATTGTTGACCAG |

| LDHA | TTGACCTACGTGGCTTGGAAG | GGTAACGGAATCGGGCTGAAT |

| Axin2 | ACCAAGTCCTTACACTCCTT | AGAAGTCTAAGGTATCCACG |

| GAPDH (homo) | AGCCACATCGCTCAGACACCAT | CAAGCTTCCCGTTCTCAGCCTT |

| GAPDH (mus) | CGTCCCGTAGACAAAATGGTG | GCTTCCCGTTGATGACAAGCT |

| Slug | CGAACTGGACACACATACAGT | CTGAGGATCTCTGGTTGTGGT |

| Twist | CAAGAGGCGCAAACAAGCC | GGTTGGCAATACCGTCATCC |

| Zeb2 | CAAGAGGCGCAAACAAGCC | GGTTGGCAATACCGTCATCC |

Analysis of glycolytic activity

Glycolytic activity was assessed by a Seahorse XF24 Extracellular Flux Analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience). A549 cells were cultured on Seahorse XF24 plates at a density of 30,000/well and glycolytic capacity was measured using XF Glycolysis Stress Test Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Seahorse Bioscience).

Measurement of cellular ROS

Cells were trypsinized, suspended in 0.5 ml serum-free DMEM, and incubated with 10 μmol/L of 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein (DCFH) diacetate for 20 min at 37 °C. Then, the cells were washed three times with serum-free DMEM. The fluorescence of the cells was measured at 525-nm wavelength with a flow cytometer (Becton–Dickinson FACSCalibur).

Nuclear extraction

Cells were washed with PBS and resuspended in 400 μl of hypotonic buffer [10 mM HEPES (pH 7.9), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, 0.5 mM DTT and fresh protease and phosphatase inhibitors]. After incubation for 10 min on ice, cells were mixed with 10 μl of 10 % NP-40 and centrifuged for 5 min at 500×g. The precipitate was washed with hypotonic buffer 3 times and then resuspended in hypertonic buffer [20 mM HEPES (pH 7.9), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 420 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM EDTA and 25 % glycerol, with fresh protease and phosphatase inhibitors] for 45 min at 4 °C. The suspension was centrifuged for 10 min at 20,000×g, and the supernatant was collected as the nuclear extracts.

ATP and NAD+/NADH quantification

The intracellular ATP content and the NAD+/NADH ratio were examined using an ATP bioluminescent assay kit (Beyotime) and a NAD+/NADH quantification kit (BioVision) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Measurement of enzyme activity in complex I and complex IV

The enzyme activities of cellular complexes I and IV were determined using the enzyme activity assay kits for each complex (Abcam) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Tissue microarray immunohistochemistry

Human lung adenocarcinoma tissue microarrays were purchased from the National Engineering Center for Biochip at Shanghai, China. The product ID of the tissue microarray used was Hlug-Ade060PG-01. The sections were dewaxed, rehydrated and treated with H2O2. The sections were incubated with TUFM antibody (1:150) and E-cadherin antibody (1:500) at 4 °C overnight followed by incubation with secondary antibody for 30 min at room temperature. After washing, the antibody was visualized using diaminobenzidine/H2O2 substrate, and the nuclei were stained with hematoxylin.

Animal experiments

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology (Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences, Chinese Academy of Science). For the analysis of in vivo tumor growth and invasion, 1 × 107 A549 cells in 200 µl of DMEM were subcutaneously injected into each 4- to 6-week-old nude mouse (n = 5). At 7 weeks after injection, mice were euthanized, whole blood was collected, and the tumors were surgically isolated and weighed. RNA from the whole blood was extracted and reverse transcribed. The human cancer cells in the mouse circulating blood were examined using real-time PCR by detecting the mRNA of human GADPH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) which is expressed only in human CTCs. The amount of human GADPH was normalized to mouse GAPDH with the specific primers for human and mouse GAPDH. For the analysis of in vivo metastasis, 5 × 105 cells were injected into the tail veins of 8-week-old nude mice (n = 6 or n = 7). After 2 months, the lungs of the nude mice were surgically isolated, and the number of surface metastases per lung was determined under a dissecting microscope.

Statistical analysis

For statistical analyses, quantitative data from at least three experiments were compared and are expressed as the mean ± SD. Statistical significance was determined using Student’s t test or one-way ANOVA. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01).

Results

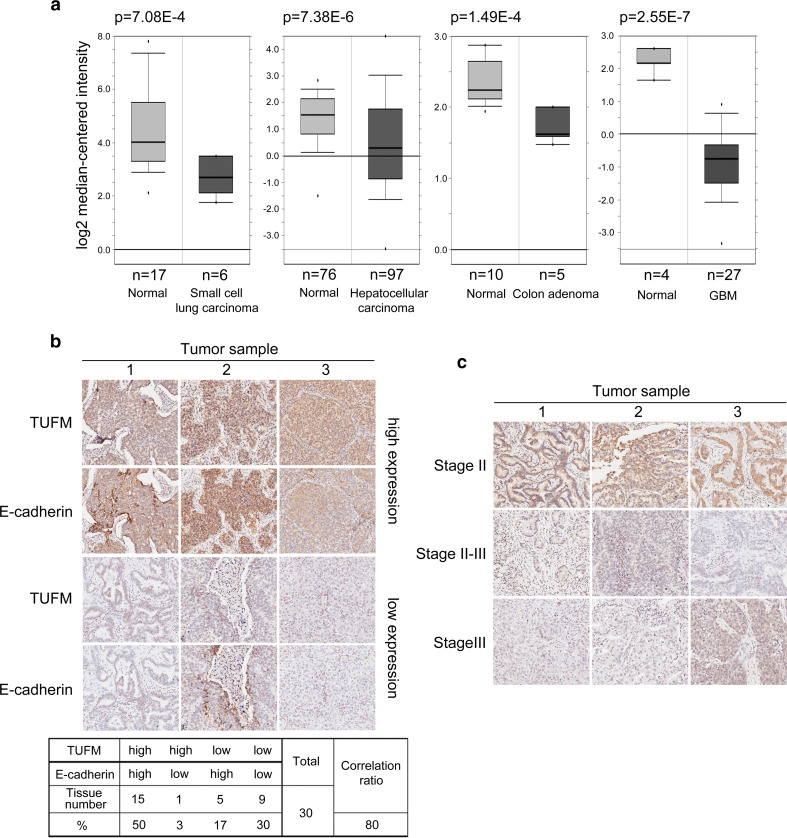

TUFM expression decreases during tumor progression

To investigate the role of TUFM in EMT and tumor development, we analyzed the expression levels of TUFM in clinical tumor samples through the online database Oncomine. Compared with normal tissues, TUFM levels are significantly decreased in several types of cancer (Fig. 1a). In addition, TUFM levels are positively correlated with E-cadherin levels in human lung adenocarcinoma tissues, as determined by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 1b). A correlation between TUFM level and EMT in breast cancer cells was also observed, as assessed by cell morphology, EMT markers, and cell migratory ability (Supplementary Fig. S1). Importantly, we observed that TUFM levels decreased progressively with the progression of lung adenocarcinoma (Fig. 1c). Furthermore, TUFM protein level was lower in infiltrating bladder urothelial carcinoma than in superficial bladder cancer tissues (Supplementary Fig. S2). These data imply that TUFM is involved in maintaining the epithelial phenotype and is downregulated in tumors.

Fig. 1.

Decreased TUFM levels are correlated with tumor progression. a Oncomine box plots of TUFM expression levels in multiple advanced human cancers, showing the number of samples and P values. b Three representative lung cancer tissue samples with high and low expression levels of TUFM and E-cadherin were examined by immunohistochemistry (upper). Statistical data are shown in the table (bottom). c Immunohistochemical analysis of expression levels of TUFM in three representative lung cancer tissue samples at different pathologic stages

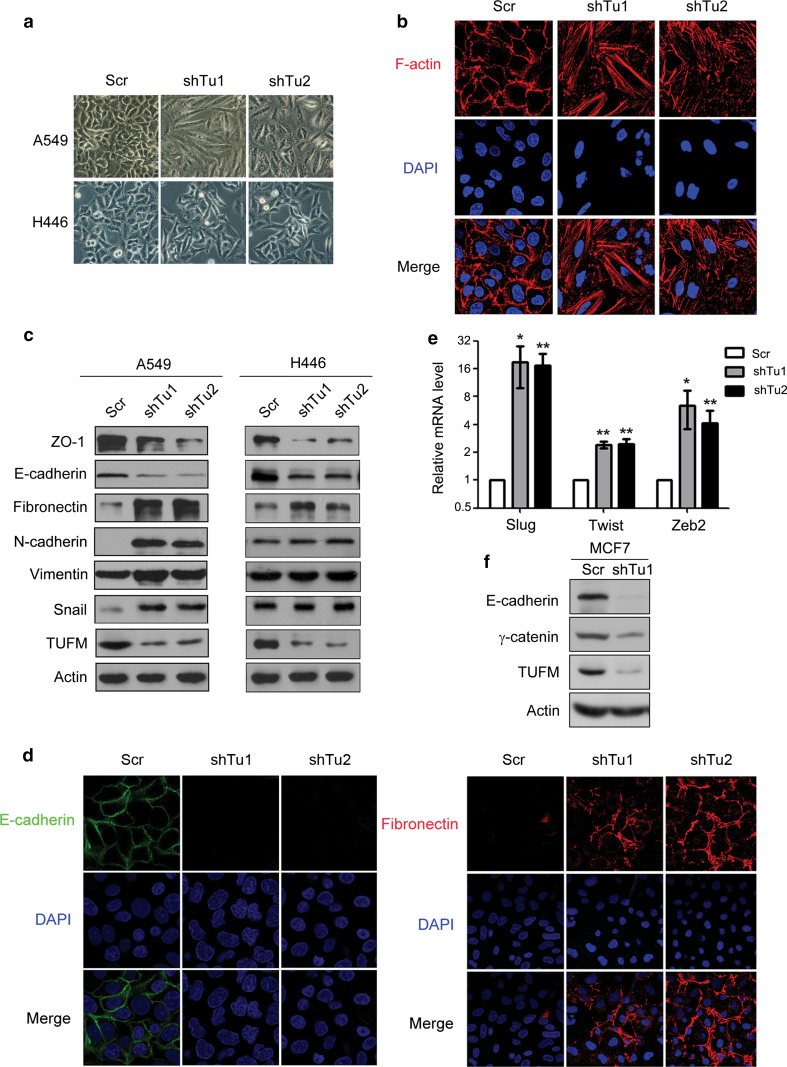

Knockdown of TUFM induces EMT in lung cancer cells

Further investigation showed that knockdown of TUFM in A549 and H446 human lung cancer cells induced morphologic changes from a square-like to a spindle-like shape (Fig. 2a). Immunofluorescent assays revealed F-actin rearrangement in A549 cells (Fig. 2b). Consistent with these findings, decreased levels of epithelial marker proteins (ZO-1 and E-cadherin) and increased protein levels of mesenchymal markers (N-cadherin, fibronectin, and vimentin) were detected in A549 cells. In addition, expression of Snail was induced. Knockdown of TUFM in H446 cells also induced EMT, as shown by decreased levels of ZO-1 and E-cadherin and increased expression of fibronectin (Fig. 2c). H446 is a lung cancer cell line that has a relatively strong mesenchymal phenotype, and the basal levels of mesenchymal marker proteins N-cadherin and vimentin are correspondingly higher than in A549 cells. In addition, the basal level of Snail is also relatively high in H446 cells. In these cells, TUFM knockdown could not further increase the levels of mesenchymal marker proteins N-cadherin and vimentin, and there was only a weak increase in the level of Snail. Changes in the cellular levels and distribution of E-cadherin and fibronectin in A549 cells induced by TUFM knockdown were determined using immunofluorescent assays (Fig. 2d). Increased mRNA level of EMT-inducing factors such as Slug, Twist, and zeb2 was also observed in A549 cells (Fig. 2e). In addition, overexpression of mouse TUFM abolished the changes induced by TUFM knockdown in A549 cells (Supplementary Fig. S3A–C). However, TUFM overexpression could not induce mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET) in H1299 and H1650 lung cancer cells, which exhibited a relatively strong mesenchymal phenotype (Supplementary Fig. S3D, E). TUFM knockdown also induced EMT in MCF7 breast cancer cells, as determined by decreased expression levels of E-cadherin and γ-catenin (Fig. 2f). These results indicate that TUFM plays a role in maintaining the epithelial phenotype of cancer cells.

Fig. 2.

Knockdown of TUFM induces EMT. a TUFM-knockdown-induced morphologic changes in lung cancer cell lines. Cells were photographed at ×200 magnification. Scr, scramble control (shRNA against a scrambled sequence). b TUFM-knockdown-induced F-actin rearrangement was detected by immunofluorescent staining. c Protein levels of EMT marker proteins ZO-1, E-cadherin, fibronectin, N-cadherin, vimentin, Snail were examined by immunoblotting. d Immunofluorescent staining of E-cadherin and fibronectin in A549 cells. e Relative mRNA levels of Slug, Twist, and Zeb2 in control and TUFM-knockdown A549 cells were quantified using real-time PCR. f Levels of E-cadherin and γ-catenin in MCF7 cells were examined by immunoblotting

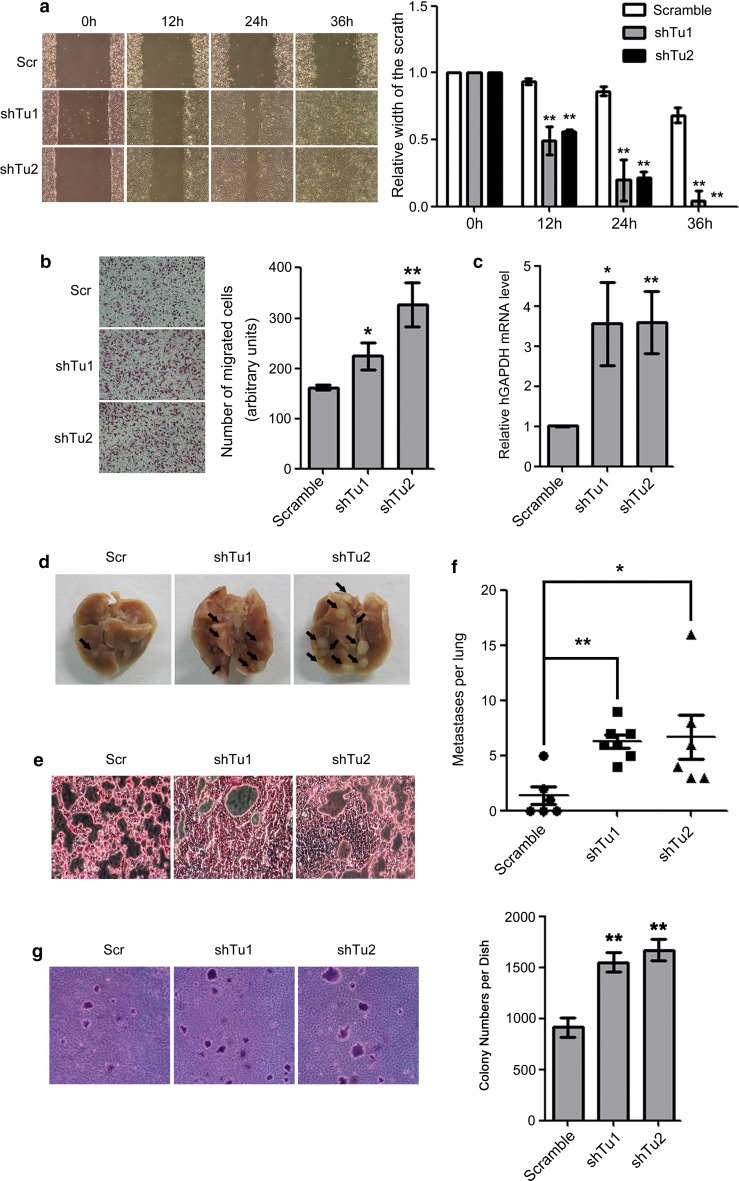

Knockdown of TUFM promotes lung cancer cell migration, invasion, metastasis, and anchorage-independent growth

Because EMT is associated with the invasive growth and metastasis of cancers, we also examined the effects of TUFM knockdown on the migration, invasion, and metastasis of lung cancer cells. Wound-healing (Fig. 3a) and transwell (Fig. 3b) assays showed that TUFM knockdown significantly increased the migratory ability of A549 cells. The ability of TUFM-knockdown A549 cells to invade from the primary tumor into blood vessels was also significantly increased in vivo, as determined by the presence of circulating tumor cells in a mouse xenograft model (Fig. 3c). To examine whether TUFM knockdown enhances the metastasis of lung cancer cells in vivo, we injected control or TUFM-knockdown A549 cells into the tail veins of nude mice and found that knockdown of TUFM significantly promoted the formation of metastatic nodules in lungs (Fig. 3d–f). Moreover, TUFM knockdown significantly increased the survival of tumor cells in the blood (Supplementary Fig. S4) and increased colony formation of A549 cells in soft agar (Fig. 3g). These results suggest that TUFM knockdown increased the ability of lung cancer cells to resist anoikis.

Fig. 3.

Effects of TUFM knockdown on cell migration, invasion, and metastasis. a Cell migration was examined by wound-healing assays. Scr, scramble control (shRNA against scrambled sequence); shTu, TUFM knockdown. Cell morphology was examined at the indicated time points after scratching. Data shown are a representative result of three independent experiments (left) with statistical analysis (right). b Cell migration was examined by transwell assays. Data shown are a representative result of three independent experiments (left) with statistical analysis (right). c At 7 weeks after subcutaneous injection of control or TUFM-knockdown A549 cells, the levels of circulating tumor cells in the blood were determined by real-time PCR. Statistical data for three independent experiments are presented. d Lungs of nude mice were surgically isolated and photographed 2 months after tail vein injection of control or TUFM-knockdown A549 cells. Lung surface metastatic nodules are indicated by black arrows. e Histologic analysis by hematoxylin and eosin staining of lungs 2 months after tail vein injection. f The number of surface metastases per lung was determined using a dissecting microscope, and statistical analysis is presented. g The effect of TUFM knockdown on anchorage-independent growth of A549 cells was determined by a colony formation assay in soft agar. Data shown are a representative result of three independent experiments (left) with statistical analysis (right)

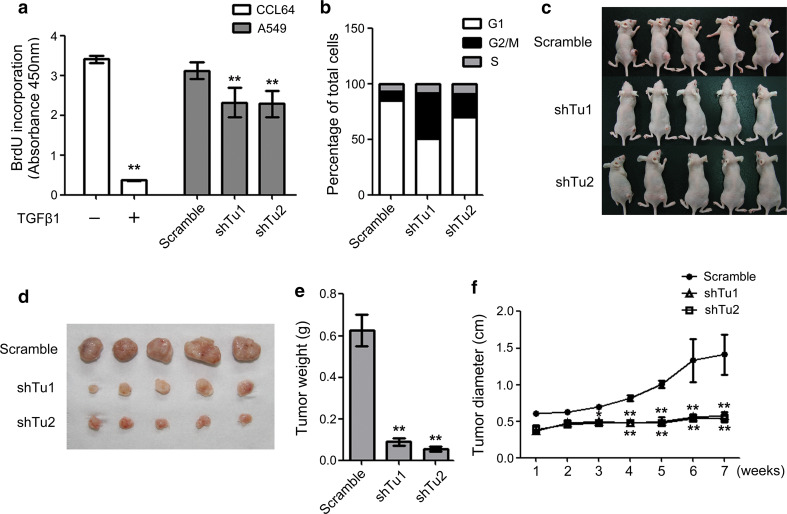

Because normal mitochondrial function is important for cell growth, we also examined the influence of TUFM knockdown on the cell proliferation rate. Knockdown of TUFM inhibited cell proliferation as examined with a BrdU incorporation assay (Fig. 4a). As shown in Fig. 4b, TUFM knockdown caused significant arrest at the G2/M phase, which is consistent with a previous report that mitochondrial respiration activity is required for cells to proceed through the G2/M transition [19]. To investigate whether TUFM knockdown impairs the growth of xenografted lung cancer cells, we subcutaneously injected TUFM-knockdown A549 cells and control cells into nude mice and examined tumor growth using photography and surgical isolation. As shown in Fig. 4c–f, TUFM knockdown significantly reduced the tumor growth rate in vivo (Fig. 4e, f). These results indicate that TUFM is important for the growth of lung cancer cells. Thus, TUFM knockdown induced EMT and increased cell migration, invasion and metastasis, but reduced the rate of cell proliferation.

Fig. 4.

TUFM knockdown reduces cell proliferation and xenograft tumor growth. a Cell proliferation was examined by BrdU incorporation assay. The inhibitory effect of TGF-β (5 ng/ml, 24 h) on CCL64 cells was used as a positive control. Data shown represent statistical analysis of three independent experiments. b The percentage of cells in different cell cycle phases was examined using FACS, and statistical analysis is shown. c, d At 7 weeks after subcutaneous injection of control or TUFM-knockdown A549 cells, nude mice were photographed (c), and tumors from each mouse were surgically isolated (d). e Control and TUFM-knockdown tumors were weighed after surgical isolation. Data shown are the statistical analysis of three independent experiments. f The diameters of control and TUFM-knockdown tumors were measured at the indicated time points. Statistical data of three independent experiments are presented

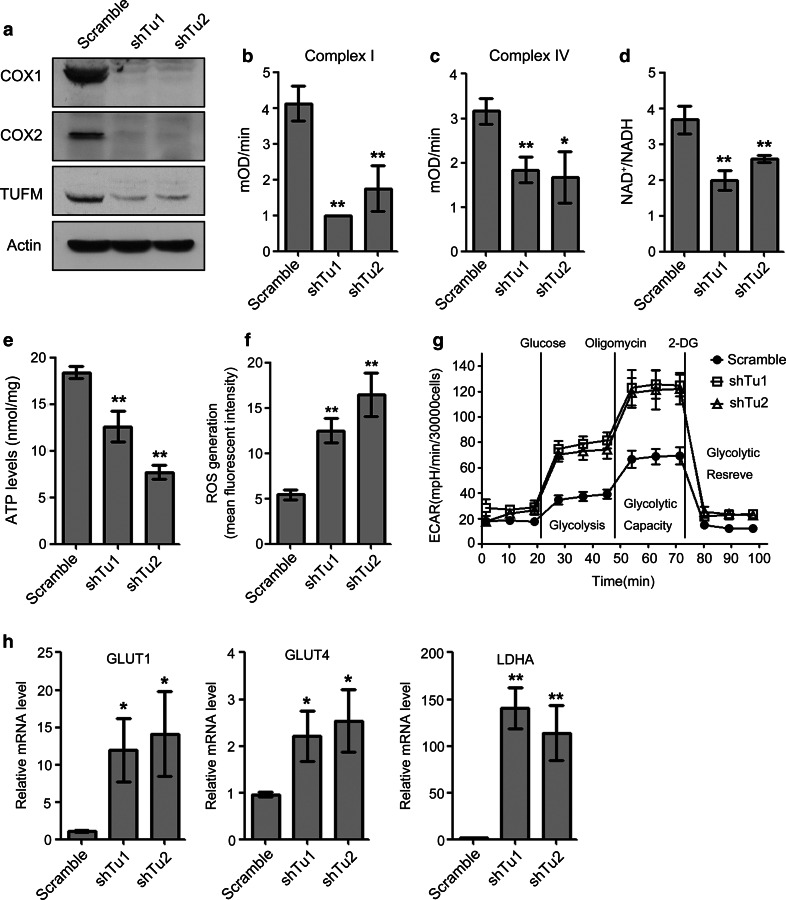

TUFM knockdown reduced mitochondrial respiratory chain activity and increased glycolysis and reactive oxygen species production in lung cancer cells

Because TUFM is essential for normal mitochondrial function, we next investigated whether TUFM knockdown affected mitochondrial respiratory chain activities. Consistent with a previously published report [20], TUFM knockdown decreased the expression levels of COX1 (cytochrome c oxidase 1) and COX2, which are encoded by mtDNA, indicating that TUFM knockdown suppressed the translation of mtDNA (Fig. 5a). In addition, the enzymatic activities of mitochondrial respiratory complex I and complex IV, which contain several mtDNA-encoded proteins, were significantly decreased by TUFM knockdown (Fig. 5b, c). Complex I is an essential respiratory enzyme that catalyzes NADH oxidation, and TUFM knockdown significantly decreased the NAD+/NADH ratio in whole cell extracts (Fig. 5d). ATP is a major product of the mitochondrial respiratory chain, and TUFM knockdown also significantly decreased the cellular ATP levels (Fig. 5e). These results suggest that TUFM knockdown impairs mitochondrial respiratory chain activity. Inhibition of mitochondrial oxidation has been shown to increase levels of ROS [21, 22] and, accordingly, TUFM knockdown significantly increased ROS levels in A549 cells (Fig. 5f). As EMT can be associated with increased glycolysis, and impaired mitochondrial function can increase glycolysis in cancer cells [12, 23], we examined whether TUFM knockdown affected glycolytic function. The extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) reflects the glycolytic function of cells. Strikingly, TUFM knockdown increased glycolysis of lung cancer cells (Fig. 5g) and markedly induced the expression of the glycolytic genes glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1), glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4), and lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA) (Fig. 5h). These results confirmed that impaired mitochondrial function could promote glycolysis.

Fig. 5.

TUFM knockdown reduces mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and glycolysis in lung cancer cells. a Protein levels of COX1 and COX2 in the indicated cells were examined by immunoblotting. b, c Effects of TUFM knockdown on the enzymatic activities of complex I (b) and complex IV (c) in A549 cells. Data shown are the statistical analysis of three independent experiments. d, e Effects of TUFM knockdown on cellular NAD+/NADH ratios (d) and ATP levels (e) in A549 cells. Data shown are the statistical analysis of three independent experiments. f ROS levels in control and TUFM-knockdown A549 cells were detected by FACS. Data shown are statistical analysis of three independent experiments. g Kinetic chart of Seahorse XFe24 glycolysis stress analysis. Cells were incubated in the absence of glucose for 1 h, and then glucose (10 mM), oligomycin (1 μM), and 2-DG (100 mM) were added. Glycolytic function was assessed by measuring the extracellular acidification rate (ECAR). h Relative mRNA levels of GLUT1, GLUT4, and LDHA in control and TUFM-knockdown A549 cells were quantified using real-time PCR. Data shown are statistical analysis of three independent experiments

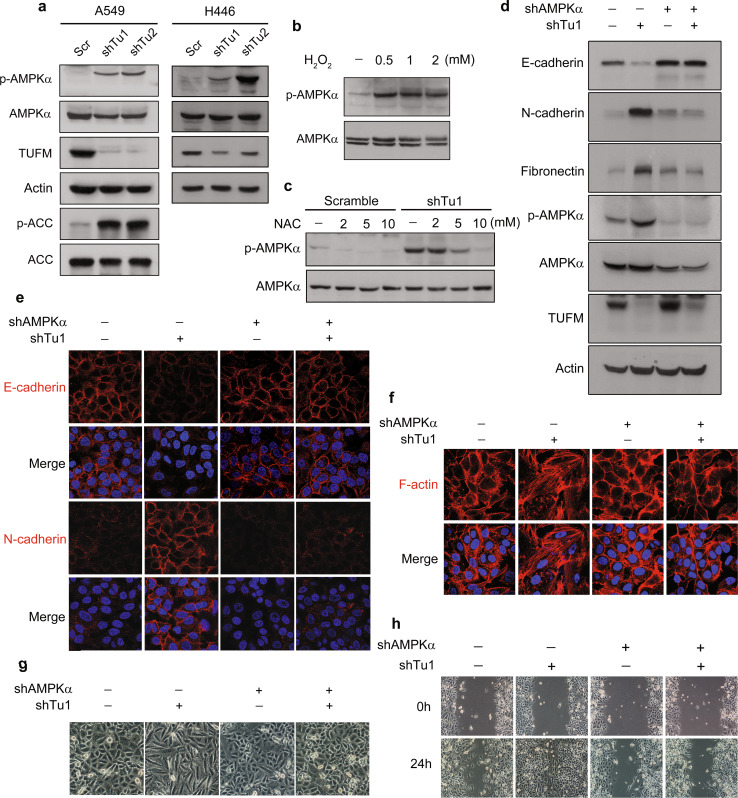

AMPK plays a role in TUFM-knockdown-induced EMT

AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is a highly conserved serine/threonine protein kinase that plays an important role in the regulation of cellular energy metabolism and other biological functions. AMPK is typically activated in response to cellular stresses such as a high AMP: ATP ratio, hypoxia, and oxidative stress [24, 25]. Because TUFM knockdown significantly decreased the ATP level and increased ROS production in lung cancer cells, we examined whether the effects of TUFM knockdown are associated with AMPK activation. Indeed, TUFM knockdown significantly activated AMPK in A549 and H446 cells, as shown by phosphorylation of AMPKα and its downstream target acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) (Fig. 6a). Treatment of cells with H2O2 significantly induced AMPK activation (Fig. 6b), whereas NAC treatment reduced the AMPK activation induced by TUFM knockdown (Fig. 6c). These data suggest that ROS are important in AMPK activation mediated by TUFM knockdown. AMPK activation has been previously shown to be required for TGF-β1-induced EMT in mouse hepatocytes [26] and we observed that TGF-β1 activated AMPK during EMT induction in A549 cells (Supplementary Fig. S5A). Inhibition of AMPK activation by Compound C or AMPKα knockdown suppressed TGF-β1-induced EMT in A549 cells (Supplementary Fig. S5B, C). Notably, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S6, the AMPK activator AICAR had no obvious effect on TGF-β-induced EMT in A549 cells, as determined by cell morphology and expression levels of E-cadherin and N-cadherin (Supplementary Fig. S6A, S6B). The same results were observed with overexpression of AMPKα or a constitutively activated AMPKα mutant (CA-AMPKα) (Supplementary Fig. S6C, S6D). Consistent with these findings, AMPK activator or AMPK overexpression had no feedback effect on the phosphorylation of Smad2 and Smad3 (Supplementary Fig. S6E, S6F). These results imply that the background expression level of AMPK is sufficient for TGF-β-induced EMT. The fact that AMPK activation is essential for TGF-β1-induced EMT in human lung cancer cells prompted us to examine whether AMPK activation is necessary for TUFM-knockdown-induced EMT. Downregulation of AMPK (AMPKα) abolished the TUFM-knockdown-induced EMT, as assessed by levels of E-cadherin, N-cadherin, and fibronectin (Fig. 6d, e), rearrangement of F-actin (Fig. 6f) and cell morphologic changes (Fig. 6g). Knockdown of AMPKα also suppressed TUFM-knockdown-induced cell migration in a wound-healing assay (Fig. 6h). These results suggest that AMPK is required for the induction of EMT by TUFM knockdown.

Fig. 6.

AMPK activation is essential for EMT induction by TUFM knockdown. a TUFM-knockdown-induced AMPK activation was assessed by examining the levels of p-AMPK (T172) and p-ACC in A549 and H446 cells by immunoblotting. b A549 cells were treated with H2O2 at the indicated concentrations for 2 h and the expression levels of AMPK and p-AMPK (T172) were determined by immunoblotting. c Effect of NAC treatment (2 h) on AMPK and p-AMPK (T172) levels in control and TUFM-knockdown A549 cells. d–g Inhibition of AMPK activation by AMPKα knockdown suppressed the induction of EMT by TUFM knockdown, as determined by immunoblotting (d) and immunofluorescent staining of EMT marker proteins (e), immunofluorescent staining of F-actin (f), and cell morphologic changes (g). h Cell migration of control and TUFM-knockdown A549 cells with or without AMPKα knockdown was examined by the wound-healing assay

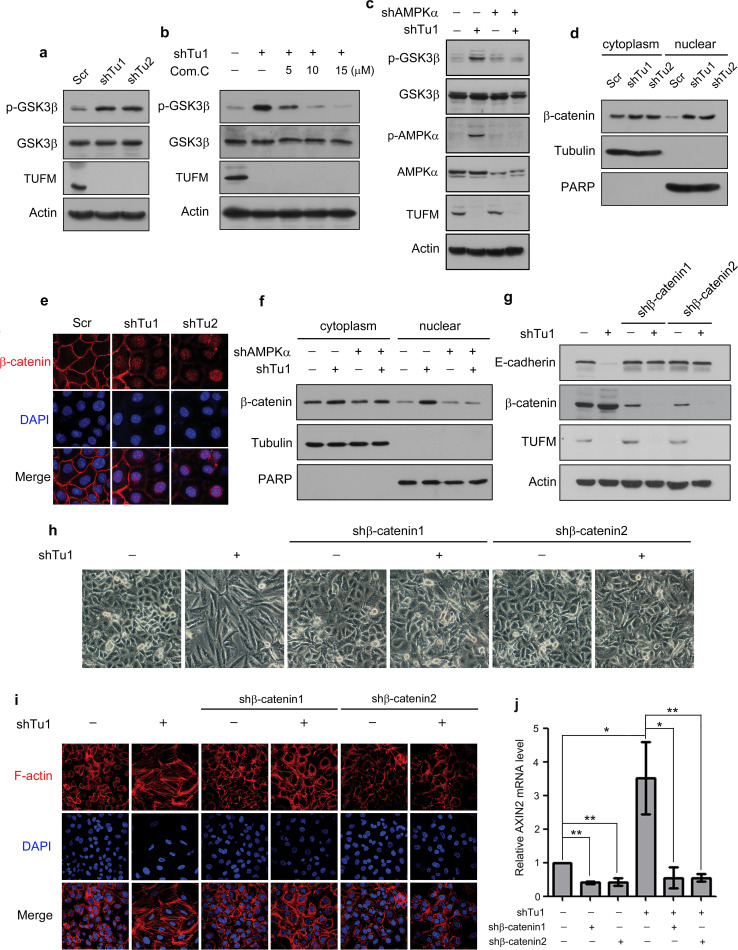

The AMPK-GSK3β/β-catenin pathway is involved in TUFM-knockdown-induced EMT

The GSK3β/β-catenin pathway has been reported to be involved in the regulation of glycolytic metabolism and EMT of cancer cells [27, 28]. To further investigate the mechanism by which TUFM regulates EMT, we examined the possible involvement of GSK3β in this process. TUFM knockdown significantly increased GSK3β phosphorylation (Fig. 7a) and the mRNA level of Axin2, a downstream gene in GSK3β signaling (Supplementary Fig. S7A). Further examination showed that inhibition of AMPK using Compound C suppressed both GSK3β phosphorylation (Fig. 7b) and the increased Axin2 level induced by TUFM knockdown (Supplementary Fig. S7B). Downregulation of AMPKα also abolished the GSK3β phosphorylation induced by TUFM knockdown (Fig. 7c). These results indicate that TUFM-knockdown-mediated AMPK activation plays an important role in modulating GSK3β signaling.

Fig. 7.

TUFM knockdown activates the AMPK/GSK3β/β-catenin pathway. a The effect of TUFM knockdown on GSK3β phosphorylation (S9) in A549 cells was examined by immunoblotting. b The effect of various doses of Compound C (24 h) on the levels of phosphorylated GSK3β (S9) in control and TUFM-knockdown A549 cells was examined by immunoblotting. c Inhibition of AMPK activation by AMPKα knockdown inhibited GSK3β phosphorylation induced by TUFM knockdown, as detected by immunoblotting. d Isolation of the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions of control and TUFM-knockdown cells. Tubulin and PARP were used as loading controls for the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions, respectively. e Immunofluorescent staining of β-catenin in control and TUFM-knockdown cells. f Cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions of the indicated cells were isolated. Tubulin and PARP were used as loading controls for the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions, respectively. g–i shRNA targeting β-catenin suppressed TUFM-knockdown-induced EMT, as assessed by the level of E-cadherin (g), cell morphologic changes (h), and F-actin rearrangement (i). j Relative mRNA levels of Axin2 in the indicated cells were quantified using real-time PCR

β-catenin can translocate from the cytoplasm to the nucleus, where it binds to transcription factors to regulate the expression of EMT-related genes [29]. Since active GSK3β can interact with β-catenin, promoting its phosphorylation and degradation, inactivation of GSK3β by its phosphorylation can increase the levels of cytosolic and nuclear β-catenin. Nuclear extraction (Fig. 7d) immunofluorescent staining (Fig. 7e) assays showed that TUFM knockdown significantly increased the level of nuclear β-catenin in A549 cells. Knockdown of TUFM also increased the level of nuclear β-catenin in H446 cells (Supplementary Fig. S8A). However, TUFM knockdown did not significantly affect the location of β-catenin in MCF7 cells (Supplementary Fig. S8B). This discrepancy is probably due to differences in the cell type and context between the MCF7 breast cancer cells and the lung cancer cells that we used. Because AMPK can stimulate GSK3β phosphorylation, we hypothesized that AMPK functions in TUFM-knockdown-induced EMT by increasing the nuclear accumulation of β-catenin. Consistent with this hypothesis, inhibition of AMPK activation via AMPKα-knockdown suppressed the increase in nuclear β-catenin levels induced by TUFM knockdown (Fig. 7f). To determine whether GSK3β/β-catenin is involved in TUFM-knockdown-induced EMT, we knocked down endogenous β-catenin in A549 cells. Knockdown of β-catenin inhibited the TUFM-knockdown-induced EMT, as shown by E-cadherin levels (Fig. 7g), cell morphology (Fig. 7h), and F-actin rearrangement (Fig. 7i). In addition, β-catenin knockdown abolished its accumulation in the nuclei (Supplementary Fig. S9) and suppressed the increase in Axin2 expression in TUFM-knockdown cells (Fig. 7j), suggesting that the nuclear translocation of β-catenin induced by TUFM knockdown is important for increased transcriptional activity of its target genes. Taken together, these results suggest that the AMPK/GSK3β/β-catenin signaling pathway is involved in the TUFM-knockdown-mediated induction of EMT.

Discussion

Although mitochondrial dysfunction in human cancers has been documented in many reports, the mechanism by which mitochondrial dysfunction contributes to tumor progression remains unclear. EMT is a critical process for the invasion and metastasis of cancers; however, whether regulation of EMT is a link between mitochondrial dysfunction and cancer progression is not clear. The mitochondrial genome encodes several genes that are essential for mitochondrial function. Because TUFM is involved in the control of mitochondrial gene translation, changes in TUFM levels affect mitochondrial respiratory chain activity. TUFM-knockdown-mediated inhibition of the translation of mtDNA-encoded proteins in lung cancer cells induces both mitochondrial dysfunction and EMT, suggesting that abnormal mitochondrial gene expression plays an important role in the induction of EMT. Interestingly, TFAM and PNC1, which control the replication and transcription of mtDNA, have also been reported to suppress EMT [9, 10]. These results implicate regulation of mitochondrial gene expression at multiple levels in the control of EMT.

EMT plays a critical role in tumor progression, not only because of its roles in invasion and metastasis, but also because of its effect on the ability of cancer cells to resist anoikis. EMT inducers such as TGF-β and Snail have been shown to inhibit mitochondrial respiration [11, 12], implying that the induction of EMT is associated with suppression of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. Tumor cells with repressed mitochondrial oxidation have been shown to be more resistant to anoikis [30, 31], suggesting that repression of mitochondrial respiration is involved in the EMT-associated anoikis resistance. Our findings that decreased TUFM expression impaired the expression of mitochondrial gene-encoded proteins and induced EMT provide novel evidence for a link between regulation of EMT and mitochondrial dysfunction in lung cancer cells.

The observation that TUFM knockdown reduced the cell proliferation rate is consistent with the fact that EMT induction is usually associated with some degree of growth inhibition [32–34]. TUFM knockdown strongly reduced xenograft tumor growth in vivo and significantly inhibited the proliferation of lung cancer cells in vitro. Glucose concentrations in tumors are generally much lower than those in normal tissues [35, 36]. The mitochondrial dysfunction caused by mtDNA mutation can increase the sensitivity of cancer cells to glucose limitation [37], and we observed that TUFM knockdown significantly decreased the resistance of lung cancer cells to low glucose conditions (Supplementary Fig. S10). The concentration of glucose is much higher in the in vitro culture conditions than in the growth environment of xenograft tumor cells. Thus, the growth inhibitory effect of TUFM knockdown may vary according to glucose availability. TUFM knockdown significantly reduced the growth of xenograft lung cancer cells, but increased the migration, anchorage-independent growth, and anoikis resistance of these cells, thus promoting their invasion and metastasis. As mitochondrial dysfunction can be linked with cancer progression, the finding that mitochondrial dysfunction caused by impaired TUFM expression induced EMT provides insight into the potential mechanism underlying regulation of EMT.

Although the nuclear and mitochondrial genomes are relatively independent of one another, communication between the genomes is essential for various biological processes [38–40]. TUFM, which is encoded by a nuclear gene, synthesized in the cytoplasm, and imported into the mitochondria, regulates expression of the mitochondrial genome by controlling the translation of mtDNA-encoded proteins. These phenomena indicate that nuclear gene products can modulate the expression of mitochondrial genes. Decreased expression of mtDNA induces mitochondrial dysfunction and cellular stresses such as ATP deficiency and ROS production, which trigger AMPK activation and the subsequent regulation of nuclear gene expression and EMT. These results suggest that AMPK is a critical signal transducer in the communication between the mitochondrial genome and nuclear genes, and imply that bidirectional regulation of the mitochondrial and nuclear genomes is involved in the control of EMT.

AMPK can function as a sensor of cellular redox states and plays a key role in regulating energy homeostasis. Our finding that TUFM knockdown induces AMPK activation is consistent with the observation that TUFM knockdown induces cellular energy and oxidative stress. The fact that AMPK activation is critical for the survival of tumor cells [41] may explain why TUFM knockdown facilitated the survival of tumor cells in circulating blood. Although a role of AMPK in regulation of EMT has recently been reported [26], the underlying mechanism remained unclear. The present study shows that AMPK can regulate GSK3β phosphorylation and β-catenin nuclear translocation, which is essential for TUFM-knockdown-mediated EMT, thus suggesting that AMPK may regulate EMT by modulating the GSK3β/β-catenin pathway. It has been reported that inhibition of GSK3β and activation of β-catenin are involved in the regulation of aerobic glycolysis and expression of glycolytic genes [27, 42]. TUFM knockdown activated the AMPK-GSK3β/β-catenin pathway, promoted glycolysis, and induced expression of GLUT1 and LDHA. These data suggest that AMPK can modulate glycolytic metabolism through regulation of GSK3β. Importantly, the inhibitory phosphorylation of GSK3β by AMPK has been shown to protect cells against oxidative stress [43, 44], further suggesting a role of AMPK-mediated GSK3β phosphorylation in EMT and related cell behaviors.

Autophagy is a catabolic process by which cellular material is delivered to lysosomes for degradation [45]. Autophagy is also known to be linked to different types of cell death [46]. AMPK has been shown to play an important role in surveillance of mitochondrial damage and induction of autophagy [47]. TUFM knockdown impaired mitochondrial function and activated AMPK, suggesting that TUFM knockdown may be able to induce autophagy. Indeed, we observed that TUFM knockdown promoted autophagic induction as determined by the conversion of LC3I to LC3II (supplementary Fig. S11). Importantly, it has been reported that autophagy can promote the invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma cells through activation of EMT [48], implying that autophagic induction might be a component of the EMT-related events induced by TUFM knockdown.

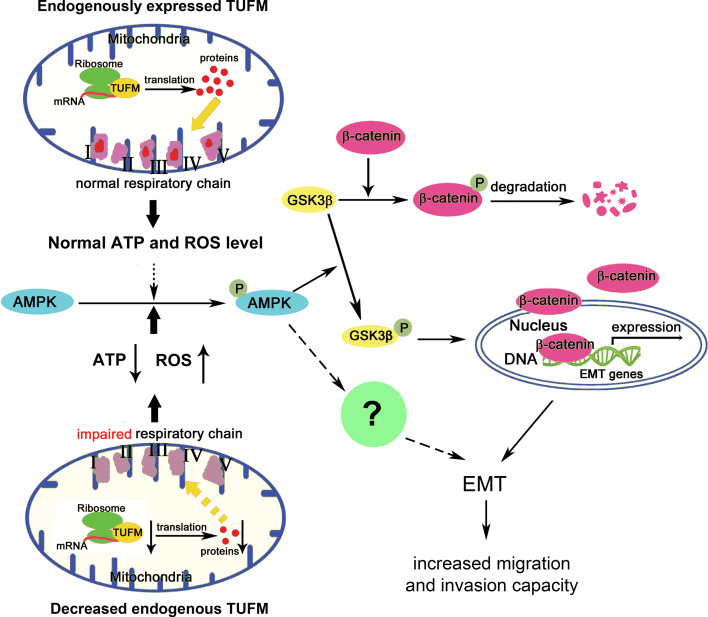

In summary, our data show that TUFM plays a critical role in maintaining the epithelial cell phenotype and therefore the control of EMT. Loss of TUFM induces EMT and metastasis of lung cancer cells via a mechanism involving activation of the AMPK/GSK3β/β-catenin pathway (Fig. 8). These results provide a molecular link between mitochondrial dysfunction and EMT, which is implicated in lung cancer progression.

Fig. 8.

Schematic illustrations of the findings of this study. Endogenous or basal TUFM expression is essential for normal mitochondria function, including levels of ATP and ROS. Reduced TUFM expression in lung cancer cells causes a decrease in mtDNA translation, leading to dysfunction of the mitochondrial respiratory chain. Mitochondrial dysfunction induces cellular stresses such as decreased ATP production and increased ROS level and the subsequent activation of AMPK, which phosphorylates and thus inactivates GSK3β. GSK3β inactivation reduces the phosphorylation and degradation of β-catenin, thereby increasing levels of cytosolic β-catenin and its nuclear translocation, which results in β-catenin-mediated gene expression and EMT. In MCF7 breast cancer cells, repression of mitochondrial gene expression activates AMPK, which is important for EMT induction as reported in other studies. Thus, decreased TUFM expression may also activate AMPK, which further promotes EMT through a somewhat different mechanism

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Yunneng Tang, Guangwen Shu, and other members of the laboratory for their critical comments and insightful discussions. This work was supported by the National Science Foundation of China (81472603) and the Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology (2011CB966200).

Abbreviations

- EMT

Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition

- TUFM

Tu translation elongation factor, mitochondrial

- GLUT1

Glucose transporter 1

- GLUT4

Glucose transporter 4

- LDHA

Lactate dehydrogenase A

- ECAR

Extracellular acidification rate

- 2-DG

2-Deoxyglucose

- AMPK

AMP-activated protein kinase

- GSK3β

Glycogen synthase kinase 3β

- ACC

Acetyl-CoA carboxylase

- AXIN2

Axis inhibition protein 2

- GAPDH

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- CTCs

Circulating tumor cells

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Kai He and Xiaojie Guo have contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Wallace DC. Mitochondrial diseases in man and mouse. Science. 1999;283(5407):1482–1488. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5407.1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ohsawa S, Sato Y, Enomoto M, Nakamura M, Betsumiya A, Igaki T. Mitochondrial defect drives non-autonomous tumour progression through Hippo signalling in Drosophila. Nature. 2012;490(7421):547–551. doi: 10.1038/nature11452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Modica-Napolitano JS, Singh KK. Mitochondrial dysfunction in cancer. Mitochondrion. 2004;4(5–6):755–762. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2004.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brandon M, Baldi P, Wallace DC. Mitochondrial mutations in cancer. Oncogene. 2006;25(34):4647–4662. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thiery JP, Acloque H, Huang RY, Nieto MA. Epithelial–mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. Cell. 2009;139(5):871–890. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lamouille S, Xu J, Derynck R. Molecular mechanisms of epithelial–mesenchymal transition. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15(3):178–196. doi: 10.1038/nrm3758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu X, Kang Y. Hypoxia and hypoxia-inducible factors: master regulators of metastasis. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(24):5928–5935. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giannoni E, Parri M, Chiarugi P. EMT and oxidative stress: a bidirectional interplay affecting tumor malignancy. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2012;16(11):1248–1263. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guha M, Srinivasan S, Ruthel G, Kashina AK, Carstens RP, Mendoza A, et al. Mitochondrial retrograde signaling induces epithelial–mesenchymal transition and generates breast cancer stem cells. Oncogene. 2014;33(45):5238–5250. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Favre C, Zhdanov A, Leahy M, Papkovsky D, O’Connor R. Mitochondrial pyrimidine nucleotide carrier (PNC1) regulates mitochondrial biogenesis and the invasive phenotype of cancer cells. Oncogene. 2010;29(27):3964–3976. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoon YS, Lee JH, Hwang SC, Choi KS, Yoon G. TGFβ1 induces prolonged mitochondrial ROS generation through decreased complex IV activity with senescent arrest in Mv1Lu cells. Oncogene. 2005;24(11):1895–1903. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee SY, Jeon HM, Ju MK, Kim CH, Yoon G, Han SI, et al. Wnt/Snail signaling regulates cytochrome C oxidase and glucose metabolism. Cancer Res. 2012;72(14):3607–3617. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yuan Y, Chen Y, Zhang P, Huang S, Zhu C, Ding G, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction accounts for aldosterone-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition of renal proximal tubular epithelial cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;53(1):30–43. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Christian BE, Spremulli LL. Mechanism of protein biosynthesis in mammalian mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1819(9–10):1035–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang KH, Tian HY, Gao X, Lei WW, Hu Y, Wang DM, et al. Ferritin heavy chain-mediated iron homeostasis and subsequent increased reactive oxygen species production are essential for epithelial–mesenchymal transition. Cancer Res. 2009;69(13):5340–5348. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu Y, He K, Wang D, Yuan X, Liu Y, Ji H, et al. TMEPAI regulates EMT in lung cancer cells by modulating the ROS and IRS-1 signaling pathways. Carcinogenesis. 2013;34(8):1764–1772. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgt132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shi J, Wang DM, Wang CM, Hu Y, Liu AH, Zhang YL, et al. Insulin receptor substrate-1 suppresses transforming growth factor-β1-mediated epithelial–mesenchymal transition. Cancer Res. 2009;69(18):7180–7187. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tiscornia G, Singer O, Verma IM. Production and purification of lentiviral vectors. Nat Protoc. 2006;1(1):241–245. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Z, Fan M, Candas D, Zhang TQ, Qin L, Eldridge A, et al. Cyclin B1/Cdk1 coordinates mitochondrial respiration for cell-cycle G2/M progression. Dev Cell. 2014;29(2):217–232. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Skrtic M, Sriskanthadevan S, Jhas B, Gebbia M, Wang X, Wang Z, et al. Inhibition of mitochondrial translation as a therapeutic strategy for human acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2011;20(5):674–688. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li N, Ragheb K, Lawler G, Sturgis J, Rajwa B, Melendez JA, et al. Mitochondrial complex I inhibitor rotenone induces apoptosis through enhancing mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(10):8516–8525. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210432200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park WH, Han YW, Kim SH, Kim SZ. An ROS generator, antimycin A, inhibits the growth of HeLa cells via apoptosis. J Cell Biochem. 2007;102(1):98–109. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qu J, Miao H, Ma Y, Guo F, Deng J, Wei X, et al. Loss of Abhd5 promotes colorectal tumor development and progression by inducing aerobic glycolysis and epithelial–mesenchymal transition. Cell Rep. 2014;9(5):1798–1811. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kahn BB, Alquier T, Carling D, Hardie DG. AMP-activated protein kinase: ancient energy gauge provides clues to modern understanding of metabolism. Cell Metab. 2005;1(1):15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hardie DG, Salt IP, Hawley SA, Davies SP. AMP-activated protein kinase: an ultrasensitive system for monitoring cellular energy charge. Biochem J. 1999;338(Pt3):717–722. doi: 10.1042/bj3380717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang X, Pan X, Song J. AMP-activated protein kinase is required for induction of apoptosis and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Cell Signal. 2010;22(11):1790–1797. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Landis J, Shaw LM. Insulin receptor substrate 2-mediated phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling selectively inhibits glycogen synthase kinase 3β to regulate aerobic glycolysis. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(26):18603–18613. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.564070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gonzalez DM, Medici D. Signaling mechanisms of the epithelial–mesenchymal transition. Sci Signal. 2014;7(344):re8. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim K, Lu Z, Hay ED. Direct evidence for a role of β-catenin/LEF-1 signaling pathway in induction of EMT. Cell Biol Int. 2002;26(5):463–476. doi: 10.1006/cbir.2002.0901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moro L, Arbini AA, Yao JL, di Sant’Agnese PA, Marra E, Greco M. Mitochondrial DNA depletion in prostate epithelial cells promotes anoikis resistance and invasion through activation of PI3 K/Akt2. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16(4):571–583. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kamarajugadda S, Stemboroski Cai Q, Simpson NE, Nayak S, Tan M, et al. Glucose oxidation modulates anoikis and tumor metastasis. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32(10):1893–1907. doi: 10.1128/MCB.06248-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burstyn-Cohen T, Kalcheim C. Association between the cell cycle and neural crest delamination through specific regulation of G1/S transition. Dev Cell. 2002;3(3):383–395. doi: 10.1016/S1534-5807(02)00221-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang Y, Pan X, Lei W, Wang J, Song J. Transforming growth factor-β1 induces epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and apoptosis via a cell cycle-dependent mechanism. Oncogene. 2006;25(55):7235–7244. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vega S, Morales AV, Ocana OH, Valdes F, Fabregat I, Nieto MA. Snail blocks the cell cycle and confers resistance to cell death. Genes Dev. 2004;18(10):1131–1143. doi: 10.1101/gad.294104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Urasaki Y, Heath L, Xu CW. Coupling of glucose deprivation with impaired histone H2B monoubiquitination in tumors. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(5):e36775. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hirayama A, Kami K, Sugimoto M, Sugawara M, Toki N, Onozuka H, et al. Quantitative metabolome profiling of colon and stomach cancer microenvironment by capillary electrophoresis time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Cancer Res. 2009;69(11):4918–4925. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Birsoy K, Possemato R, Lorbeer FK, Bayraktar EC, Thiru P, Yucel B, et al. Metabolic determinants of cancer cell sensitivity to glucose limitation and biguanides. Nature. 2014;508(7494):108–112. doi: 10.1038/nature13110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gomes AP, Price NL, Ling AJ, Moslehi JJ, Montgomery MK, Rajman L, et al. Declining NAD(+) induces a pseudohypoxic state disrupting nuclear-mitochondrial communication during aging. Cell. 2013;155(7):1624–1638. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnson KR, Zheng QY, Bykhovskaya Y, Spirina O, Fischel-Ghodsian N. A nuclear-mitochondrial DNA interaction affecting hearing impairment in mice. Nat Genet. 2001;27(2):191–194. doi: 10.1038/84831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roubertoux PL, Sluyter F, Carlier M, Marcet B, Maarouf-Veray F, Cherif C, et al. Mitochondrial DNA modifies cognition in interaction with the nuclear genome and age in mice. Nat Genet. 2003;35(1):65–69. doi: 10.1038/ng1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jeon SM, Chandel NS, Hay N. AMPK regulates NADPH homeostasis to promote tumour cell survival during energy stress. Nature. 2012;485(7400):661–665. doi: 10.1038/nature11066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang W, Zheng Y, Xia Y, Ji H, Chen X, Guo F, Lyssiotis CA, Aldape K, Cantley LC, Lu Z. ERK1/2-dependent phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of PKM2 promotes the Warburg effect. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14(12):1295–1304. doi: 10.1038/ncb2629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shin SM, Cho IJ, Kim SG. Resveratrol protects mitochondria against oxidative stress through AMP-activated protein kinase-mediated glycogen synthase kinase-3β inhibition downstream of poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase-LKB1 pathway. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;76(4):884–895. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.058479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Choi SH, Kim YW, Kim SG. AMPK-mediated GSK3β inhibition by isoliquiritigenin contributes to protecting mitochondria against iron-catalyzed oxidative stress. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;79(9):1352–1362. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.BE Fitzwalter, Thorburn A (2015) Recent insights into cell death and autophagy. FEBS J. Sep 14. doi: 10.1111/febs.13515 (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Cicchini M, Karantza V, Xia B. Molecular pathways: autophagy in cancer—a matter of timing and context. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(3):498–504. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liang J, Xu ZX, Ding Z, Lu Y, Yu Q, Werle KD, et al. Myristoylation confers noncanonical AMPK functions in autophagy selectivity and mitochondrial surveillance. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7926. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li J, Yang B, Zhou Q, Wu Y, Shang D, Guo Y, et al. Autophagy promotes hepatocellular carcinoma cell invasion through activation of epithelial–mesenchymal transition. Carcinogenesis. 2013;34(6):1343–1351. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgt063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.