Abstract

A hallmark to decipher bioprocesses is to characterize protein–protein interactions in living cells. To do this, the development of innovative methodologies, which do not alter proteins and their natural environment, is particularly needed. Here, we report a method (LUCK, Laser UV Cross-linKing) to in vivo cross-link proteins by UV-laser irradiation of living cells. Upon irradiation of HeLa cells under controlled conditions, cross-linked products of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) were detected, whose yield was found to be a linear function of the total irradiation energy. We demonstrated that stable dimers of GAPDH were formed through intersubunit cross-linking, as also observed when the pure protein was irradiated by UV-laser in vitro. We proposed a defined patch of aromatic residues located at the enzyme subunit interface as the cross-linking sites involved in dimer formation. Hence, by this technique, UV-laser is able to photofix protein surfaces that come in direct contact. Due to the ultra-short time scale of UV-laser-induced cross-linking, this technique could be extended to weld even transient protein interactions in their native context.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00018-015-2015-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Protein–protein interactions, Ultra-short UV-laser pulses, UV cross-linking, Living cells irradiation

Introduction

Communications between proteins underlie all biological processes, from the formation of multimeric proteins and protein complexes to the regulation of all the mechanisms involved in biological processes. The primary challenges associated with the study of biological systems are targeted to identify protein interactions occurring in a natural context, i.e. in vivo.

Besides the interaction of each single protein with its functional partners, the relationship between the dynamic oligomeric properties of multimeric proteins and their functional diversity plays a key role in cellular processes [1]. On the basis of known protein structures, it emerges that 50–70 % of proteins exists as homomeric complexes in vivo [1, 2].

Chemical stabilization of protein–protein interactions and protein assemblies by cross-linking is a strategy aimed at studying protein association and has been used both in vitro and in vivo, in the complex cellular milieu [3–8]. The strength of this methodology resides in the transformation of non-covalent interactions into stable covalent bonds. Methods based on in vivo cross-linking are increasingly widespread used in combination with mass spectrometry (XL-MS) to identify interacting proteins as well as topological features [3, 4, 6–11]. Some of these techniques are based on the use of ingenious and attractive chemical reagents, such as PIR reagents [7, 12, 13]. This facilitates fractionation of cross-linked peptides by introducing affinity tags within the cross-linking reagents [14]. Other techniques adopt small reagents, such as formaldehyde and glutaraldehyde [4, 9, 15], which are very reactive and membrane permeable, but rarely allow to obtain structural details. Site-specific incorporation of genetically encoded photo-reactive amino acids is particularly attractive, allowing time- and location-specific cross-linking, although engineering of living cells is required [10, 16, 17].

All these techniques are based on the use of chemical reagents, chemical treatments or engineering of living cells, which may alter the investigated proteins and their natural environment. Therefore, expanding the panel of strategies to explore protein–protein interactions within living cells is still a great challenge.

Following a multidisciplinary approach, we have recently developed a new procedure to cross-link peptides in vitro by UV-laser irradiation [18]. Upon irradiation, aromatic side chains produce radicals able to react and generate covalent bonds with nearby residues. Here, we transfer this know-how from peptides to complex biological systems, by developing a new procedure, named LUCK (Laser UV Cross-linKing), to cross-link interacting proteins in their natural context, i.e. in living cells. This cross-linking is a fast process that essentially occurs when protein surfaces are in direct contact, thus enabling LUCK to “weld” interacting protein chains potentially at zero length. In this methodology, the reactive groups are within the protein itself, without any need of reagents introduction or cell engineering. This represents the novelty and the advantage of our procedure over most of the presently available techniques. Moreover, as the targets of most common chemical cross-linkers are primary amine and thiol nucleophilic groups [19], exposed hydrophobic protein regions, which often play an important role in protein–protein interactions [20], usually escape detection. The procedure herein proposed mainly targets aromatic residues, which are present in almost all proteins. Even though their occurrence on protein surfaces is clearly lower than that of polar residues, all three aromatic residues (Phe, Trp, Tyr) are strong contact formers, as first reported by Jones and Thornton [21] and, more recently, by Mezei [22]. Moreover, it has been recently shown that hot spots of protein–protein interactions frequently contain Trp, Arg and Tyr [23]. Authors also report that mutual interactions between aromatic residues are more frequent than mutual interactions between any other couple of residues [22]. Taken together, all these data further emphasize the need of new cross-linking methodologies that specifically target aromatic residues. To the best of our knowledge, the only strategy developed so far to chemically stabilize hydrophobic interactions is the introduction of photo-leucine, photo-isoleucine and photo-methionine [10, 16].

In this work, we applied our approach in vivo to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), a homo-tetramer made up of four 37 kDa subunits, structurally and functionally well characterized [24]. Although once thought to solely play a role in glycolysis, GAPDH is now considered to be a classic example of a moonlighting protein [25]. Mammalian GAPDH has been implicated in many cellular activities, including apoptosis, nuclear RNA transport, DNA replication and repair, and it is thought to play roles in many diseases, including Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s and Huntington’s diseases [26]. This array of activities has to be correlated to a number of factors, including the stabilization of dynamic oligomers, since GAPDH largely exists as a tetramer with minor populations of dimers and monomers. Several GAPDH interactors are already known and play a key role in driving the multiple activities of the enzyme. High-resolution crystal structure of human GAPDH has been recently solved [27], giving the opportunity to have a structural understanding of the ongoing processes. This makes GAPDH an ideal candidate to test the idea of welding, by covalent bonds, interacting protein surfaces in their natural environment.

By immunological and mass spectrometry techniques, we demonstrated that, upon irradiation of HeLa living cells with UV-laser ultra-short pulses under controlled conditions, subunit–subunit cross-linking occurs in GAPDH generating dimeric species, as expected by the presence of hydrophobic residues at the symmetric interface between the two dimers which associate to give rise to the homo-tetrameric structure of the enzyme in vivo.

Results

Irradiation of HeLa living cells

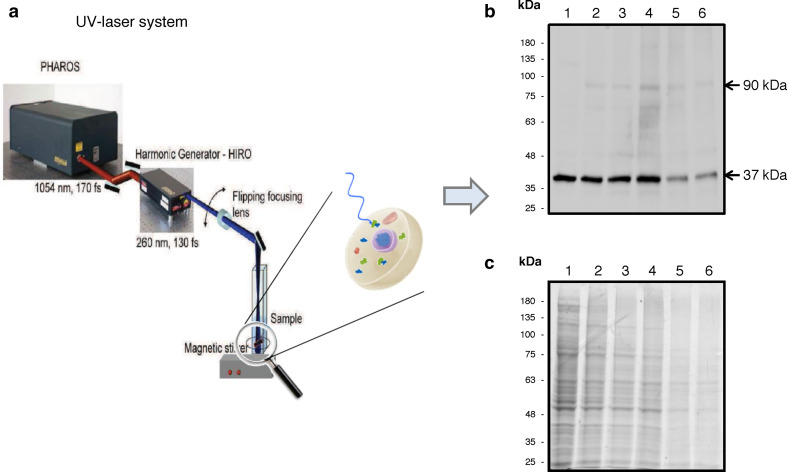

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was selected as a model protein to analyse the power of UV-laser irradiation in welding protein–protein interactions in living cells. Taking advantage of our previous in vitro studies on laser-induced cross-linking of peptides [18], human living cells (HeLa cell line from human epithelial adenocarcinoma) were irradiated with the fourth harmonic (257 nm) of a PHAROS near-IR fundamental pulse by setting the following irradiation parameters: 50 µJ as energy of each single pulse (E pulse), 2 kHz as pulse repetition rate (f rate), 10 s as total time of cell irradiation (T irr), with a total irradiation energy of = 1.0 J. To this purpose, the cell suspension (4 × 105 cells/mL) was placed in a cuvette under magnetic stirring to ensure uniform conditions during irradiation with the UV-femtosecond laser source (Fig. 1a). Total proteins were then extracted from irradiated and control cells and analysed in parallel experiments by Western blotting with anti-GAPDH antibodies (Fig. 1b) or Coomassie Blue staining (Fig. 1c). Western blot analyses revealed that, besides the presence of the monomeric form of GAPDH (37 kDa), additional immunopositive protein bands were present in the irradiated sample (Fig. 1b, lane 2), with a protein species of about 90 kDa molecular mass as the most evident, which was found to be absent in control, i.e. non-irradiated cells (Fig. 1b, lane 1). This suggested that UV-laser irradiation induced cross-linking between GAPDH and its protein partners and/or between GAPDH subunits. In either case, this represents a very promising starting point for further studies aimed at investigating the potential of this methodology in different environments. Further, Coomassie Blue staining revealed no significant differences in protein pattern between control (Fig. 1c, lane 1) and irradiated sample (Fig. 1c, lane 2), indicating that irradiation does not significantly alter cell protein profile.

Fig. 1.

UV-laser apparatus and analysis of irradiated cells. PHAROS laser apparatus (a). SDS-PAGE followed by Western blot with anti-GAPDH antibodies (b) or Coomassie Blue staining (c) of total proteins (40 µg) extracted from untreated cells (lane 1) or cells irradiated (lanes 2–6) using an energy pulse of 50 µJ and a pulse repetition rate of 2 kHz. The total irradiation energy was: 1.0 J (lane 2), 2.0 J (lane 3), 4.0 J (lane 4), 8.0 J (lane 5) and 10.0 J (lane 6), with a total irradiation time of 10, 20, 40, 80 and 100 s, respectively

Optimization of irradiation experimental conditions

To maximize the efficiency of UV-laser-induced protein–protein cross-linking, we analysed the influence of three physical parameters, i.e. f rate, E pulse and T irr, on the cross-linking yield. By assuming a linear response of cross-linking yield to laser irradiation, it turns out that the yield of the process depends upon only through D. It is worth noticing that, in place of the pulse energy (E pulse), we should better consider the laser intensity, I [28], proportional to E pulse and defined as , S being the laser beam section onto the target and τ pulse the laser pulse duration. Typically, I is expressed in W/cm2 and corresponds to the peak intensity of a single ultra-short laser pulse. In our case, S and τ pulse were fixed to ~0.3 cm2 and ~250 femtosec, respectively, [29] in all the tested experimental conditions. Thus, in the following, we shall refer to E pulse, rather than I, E pulse being varied between 30 and 70 µJ, that implies 4.0 × 108 W/cm2 ≤ I ≤ 9.3 × 108 W/cm2.

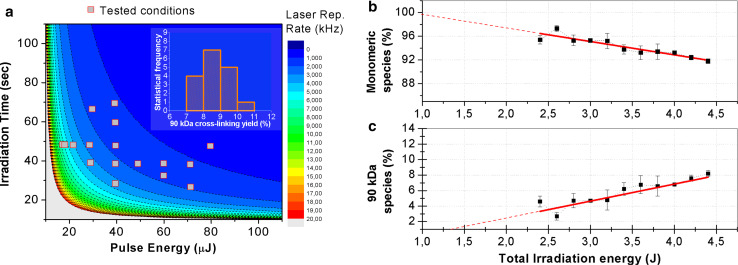

Therefore, optimization measurements were carried out at constant D, set at the value of 4.0 J, as a similar value was used to cross-link DNA and proteins by UV-laser irradiation [30]. Through the experiments, each of the three parameters was kept constant, while the other two were varied. In a first subset of experiments, at a fixed repetition rate of 2 kHz, T irr and E pulse were changed; in a second subset, T irr was set at 40 s and E pulse and f rate varied; and in a third subset, E pulse was kept constant at 50 μJ, whereas f rate and T irr were changed. Using this scheme, E pulse was scanned between 30 and 70 µJ, T irr was varied between 30 and 70 s, and f rate was tested between 1 and 6 kHz. The panel of irradiation conditions is reported in the contour plot frame of Fig. 2a, where pulse energy and irradiation time are reported on x- and y-axes, respectively, whereas the colour code refers to laser repetition rate reported in the third dimension. The experimental conditions, represented by rectangles in Fig. 2a, are detailed in ESM_Table 1.

Fig. 2.

Optimization of HeLa living cells irradiation conditions. 3D representation of the laser parameter space as a contour plot (a), being the pulse energy and the irradiation time the x- and y-axis, respectively, and the colour code representing in the third dimension the laser repetition rate. In the plot, the experimental conditions tested (rectangles) refer to the selected constant energy dose of 4.0 J. The ~90 kDa cross-linked species yield (%) at a constant energy dose of 4.0 J is reported in the inset in panel a. The percentage of monomeric GAPDH (b) and of the ~90 kDa species (c), with GAPDH monomers + GAPDH complexes equal to 100 %, is reported as a function of total irradiation energy. This was varied by increasing the irradiation time between 24 and 44 s, and keeping constant the pulse energy at 50 µJ and the repetition rate at 2 kHz. The Pearson’s R coefficients of the linear best-fit in b and c are 0.97 and 0.96, respectively. In panel b, the slope of the line is −(2.2 ± 0.2) × 10−3 J−1 and the intercept value is nearly consistent with 100, as expected, within the error bar. In panel c, the slope of the line is (2.2 ± 0.2) × 10−3 J−1 and the intercept value is nearly consistent with 0

For each set of experiments, the cross-linking yield was determined as follows. Upon UV-laser irradiation of HeLa living cells, total proteins were extracted and analysed by Western blotting using anti-GAPDH specific antibodies (see ESM_Fig. 1). The relative intensities of the two main protein bands recognized by the antibody, corresponding to monomeric GAPDH (37 kDa) and to cross-linked species (~90 kDa band), were determined by densitometric analyses, normalized to the total protein amount of each sample and expressed as percentage of total GAPDH (monomers + complexes = 100 %). The results clearly showed that in all the conditions tested, at D = 4.0 J, the relative amount of GAPDH monomer and cross-linked products remains substantially unvaried, being the percentage of GAPDH cross-linked species (~90 kDa) nearly stable at ~10 % (inset in Fig. 2a), independently on , thus confirming our initial assumption that cross-linking yield only depends on D. It is worth noting that, under some irradiation conditions, immunopositive complexes with a molecular mass higher than 90 kDa were also present (ESM_Fig. 1). They may correspond to higher molecular order protein complexes, which in principle may undergo different excitation schemes at a molecular level.

We then analysed the effects of energy dose with the ultimate goal to maximize cross-linking efficiency. We set f rate and E pulse at 2 kHz and 50 µJ, respectively, while the T irr was varied from 24 to 44 s to reach a dose comprised in the 2.4–4.4 J range. The percentage of monomeric GAPDH and of cross-linked species is reported in Fig. 2b and c, respectively, as a function of D. A linear decrease of the 37 kDa monomeric species (from 98 to 92 %, Fig. 2b) and a corresponding linear increase of higher molecular mass species (from 3 to 8 %, Fig. 2c) were observed by increasing the dose. The Pearson’s R coefficients of the linear best-fit in Fig. 2b and c were found to be 0.97 and 0.96, respectively, thus confirming the goodness of linearity in the investigated range of laser dose. It is noteworthy that by delivering a total irradiation energy lower than 2.4 J significantly less efficient cross-linking occurs (Fig. 1b, c, lane 2), while at higher energy doses (>4.4 J) total protein amount appeared to be much lower (Fig. 1b, c, lanes 5 and 6), although no significant changes in protein pattern were observed. This is possibly due to extensive and uncontrolled cross-linking generating insoluble protein aggregates, removed by centrifugation prior to electrophoresis. Indeed, the overcrowded conditions of the intracellular environment could promote, at high energy doses, a rapid intermolecular cross-linking, as proteins are in constant contact. This indicates that protein–protein cross-linking efficiency may be modulated, since the phenomenon depends upon the total energy released to the target.

All the data set allowed us to define the optimal irradiation conditions, thereafter used as standard parameters; 40 s irradiation time, 50 µJ pulse energy, 2 kHz repetition rate and 4.0 J total irradiation energy represent the conditions that maximize cross-linked GAPDH signals (Fig. 1b, lane 4) without altering total protein pattern (Fig. 1c, lane 4). Under these conditions, we observed high reproducibility of the cross-linked species yield (10 % ± 1, n = 30 independent experiments).

The linear correlation between the yield of cross-linked products and the total irradiation energy suggests that the process is triggered by the absorption of a single UV-laser photon by side chains of aromatic amino acids. In this hypothesis, it is possible to define the value of the energy required to induce protein–protein cross-linking as approximately the energy associated to a single 257 nm photon (4.81 eV).

Identification of GAPDH cross-linked species

To identify the protein species covalently bound to GAPDH upon living cells irradiation, mass spectrometry analyses of total proteins extracted from control and irradiated HeLa cells were performed. By superimposing the Western blot (Fig. 1b) to the corresponding Coomassie Blue stained gel (Fig. 1c), the gel area corresponding to the immunopositive signal of ~90 kDa molecular mass was localized (Fig. 1b, c, lane 4), excised from gel and treated as described in the “Materials and methods”. As control, the equivalent gel section was also excised from the non-irradiated sample lane (Fig. 1c, lane 1). Proteins were identified by standard proteomic procedures by LC–MS/MS and database search in the human subset of NCBI with a licensed version of MASCOT software. In agreement with the immunopositive signal revealed by Western blot analysis (Fig. 1b, lane 4), LC–MS/MS analysis indicated the presence of GAPDH in the ~90 kDa protein band, based on the identification of 8 peptides covering 35 % of GAPDH sequence. This represents a clear evidence of the formation of cross-linked GAPDH species upon living cells irradiation. No photo-oxidized peptides were detected in the analysed samples.

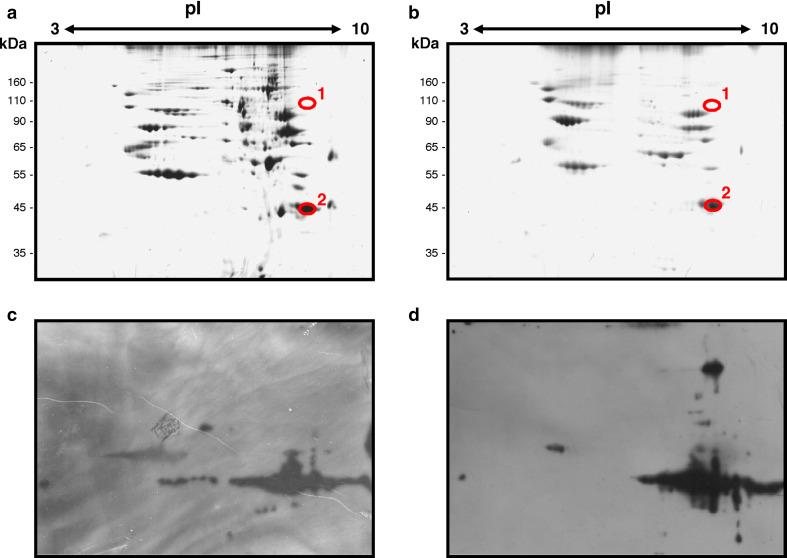

In order to identify the GAPDH cross-linked species, total proteins extracted from control and irradiated cells were fractionated by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (2D gel). Gels were either stained with colloidal Coomassie Blue (Fig. 3a, b, for control and irradiated cells, respectively) or analysed by Western blotting with anti-GAPDH specific antibodies (Fig. 3c, d, for control and irradiated cells, respectively). As shown in Fig. 3, a high molecular mass protein spot (spot 1) was recognized by anti-GAPDH antibodies in the irradiated sample, migrating as a ~90 kDa species, and with the same pI as monomeric GAPDH (spot 2). By superimposition of 2D blot and 2D gel of the irradiated sample, protein spots of interest were localized, excised from gel and in situ digested with trypsin. As control, the corresponding spots were excised from the gel of the non-irradiated sample. The resulting peptide mixtures were analysed by nanoLC-MS/MS experiments, as described above, and, in agreement with immunostaining, the high molecular mass protein spot of irradiated sample was found to contain GAPDH (ESM_Table 2). Most interestingly, no other proteins were identified in the same spot, thus suggesting that GAPDH intersubunit cross-linking occurred.

Fig. 3.

Two-dimensional electrophoresis of proteins extracted from HeLa cells, untreated (a, c) or exposed to UV-laser irradiation (b, d). Duplicate samples of each total protein extract were fractionated in parallel by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis, and analysed by colloidal Coomassie Blue staining (a, b), or transferred onto a PVDF membrane (c, d) and immunoblotted with anti-GAPDH antibodies. Circles on Coomassie Blue stained gels correspond to spots that were excised for subsequent analyses

To further investigate this point, total proteins were extracted from control and irradiated cells and immunoprecipitated with anti-GAPDH specific antibodies. The immuno-selected proteins were then analysed by SDS-PAGE, followed by Coomassie Blue staining (ESM_Fig. 2). From gels of irradiated and control samples, 12 slices were excised, as indicated in ESM_Fig. 2, and analysed by nanoLC-MS/MS as described above. The comparative analysis of the identified proteins (ESM_Table 3) indicated that at ~90 kDa molecular mass (slice 5), and even at higher molecular masses (slices 2–4), GAPDH was present in the irradiated sample but not in control cells. Since no other proteins were found, this clearly confirmed that intermolecular cross-linking between GAPDH subunits was induced by UV-laser irradiation of living cells.

It is worth noting that no known photo-oxidation products of Trp and Tyr [31] were detected in the analysed irradiated samples, while classical methionine oxidation was observed both in irradiated and control samples (ESM_Table 2, ESM_Table 3).

In silico and in vitro GAPDH spectroscopic analyses

To shed light on GAPDH intersubunit cross-linking, we irradiated in vitro pure GAPDH from rabbit muscle (95 % identity with human GAPDH) and compared the electrophoretic mobility of cross-linked products to that of immunopositive GAPDH species obtained upon irradiation of living cells. As shown by Western blot analysis (Fig. 4a), a species with an apparent molecular mass of ~90 kDa, comparable to that of the GAPDH species cross-linked in living cells, was found to be present in the in vitro irradiated sample.

Fig. 4.

Irradiation of GAPDH in vitro and human GAPDH crystal structure. Comparative Western blot analysis of in vitro irradiated GAPDH from rabbit muscle and endogenous GAPDH from irradiated cells (a). Total proteins were extracted from untreated cells (control) and irradiated cells (lane 1) and analysed with anti-GAPDH antibodies. Pure GAPDH was analysed before (lane 3) and after (lane 2) in vitro irradiation. Human GAPDH crystal structure (PDB ID 1U8F27) (b). The four symmetry-related subunits are specified as in the bottom balloons. W196 from P subunit, and Y42, Y45, Y49 from Q subunit are showed as green sticks. This figure was generated using the PyMOL molecular graphics system, by Delano Scientific (www.pymol.org)

Moreover, we analysed the high-resolution GAPDH crystal structure to investigate on the exclusive formation of dimers. The protein is a D 2-symmetric homo-tetramer in its functional form, with three independent interfaces [27]. Cross-distance matrix between aromatic residues (ESM_Fig. 3) clearly shows that only one interface (the so-called R interface) presents aromatic residues prone to cross-link. In particular, W196 is in close proximity with three tyrosine residues (Y42, Y45, Y49) from the nearby subunit (Fig. 4b). Therefore, only dimers can be generated by UV-laser cross-linking, whereas higher oligomers cannot be predicted based on GAPDH intrinsic symmetry and on the assumption that aromatic residues are essential for laser-induced cross-linking.

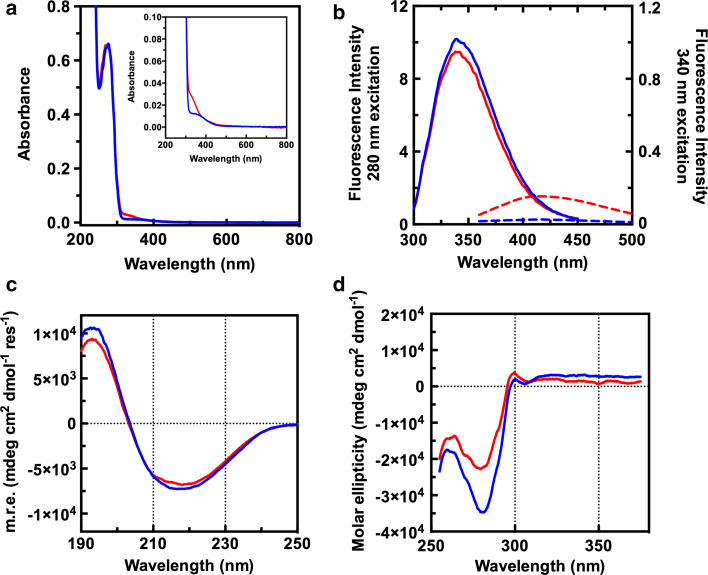

To deeply analyse the involvement of aromatic residues in the intersubunit cross-linking, we performed a spectroscopic characterization of the irradiated GAPDH from rabbit muscle in vitro. UV–Vis spectrum of irradiated sample clearly showed a new band centred around 330 nm (Fig. 5a), which can be interpreted as a conjugated aromatic chromophore [32], whereas the absorption intensity of the 280 nm band remains substantially unchanged, with a slight increase in the 250–270 nm region. Tryptophan intrinsic fluorescence analyses of the irradiated GAPDH showed only a decrease in intensity (Fig. 5b), without any difference in the emission maximum wavelength, suggesting a quenching of the fluorescence probably due to a higher solvent exposure, or a decrease in the number of fluorophores that are excited at 280 nm. The latter hypothesis was further supported by a concomitant increase of emission at 420 nm, upon 340 nm excitation, thus indicating that a fraction of aromatic residues was involved in the red-shifted fluorescence.

Fig. 5.

Spectroscopic characterization of irradiated GAPDH from rabbit muscle. Blue lines are relative to control GAPDH, red lines are relative to irradiated samples (65 µM in 50 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.5). UV–Vis absorption spectra (a) including a magnification in the inset; intrinsic fluorescence spectra (b); far-UV and aromatic region circular dichroism spectra (c, d). In b, intrinsic fluorescence emission was registered upon excitation at 280 nm (continuous lines) or at 340 nm (dashed lines)

Circular dichroism (CD) analysis was performed both in the amide and in the aromatic regions. CD spectra in the far-UV (Fig. 5c) were typical of an α/β protein, in good agreement with previously published GAPDH CD analyses [33, 34]. Irradiated sample showed only slight spectral differences in this region with respect to control GAPDH, indicating that the secondary structure content is almost unaltered. Spectral differences between irradiated and control samples in the near-UV region (Fig. 5d) were more evident, in agreement with fluorescence and absorption data. Global profiles of the spectra remained unaltered, with bands centred at the same wavelengths. However, we found a significant decrease of the molar ellipticity of the minimum at 280 nm in the case of the irradiated sample.

Discussion

We conceived and set up a simple, reliable method to “weld” protein surfaces that come in direct contact, by establishing cross-links at zero length. By in vitro studies on peptides, we demonstrated that a radical mechanism is at the basis of the phenomenon as, upon absorption of UV light, aromatic side chains produce radicals able to react and generate covalent bonds with nearby residues [18]. Hence, reactive groups belong to the interacting proteins themselves, without the need of introducing reagents, which may alter the protein natural environment. This represents a great advantage of the methodology. Furthermore, cross-linking occurs in a very rapid time scale and is triggered by the absorption of a single UV-laser photon by an aromatic side chain.

Using HeLa cells as the natural context and endogenous GAPDH (37 kDa) as a model protein, we demonstrated, for the first time, that UV-laser irradiation of living cells freezes GAPDH complexes of high molecular mass, among which we focused on species of about 90 kDa for protein identification. We defined a wide energy range in which the yield of these cross-linked products is a linear function of total irradiation energy with no apparent perturbation of cell proteome. Within this range, we set up optimal conditions to induce cross-linking by UV-laser irradiation of living cells.

By immunological, 2D-electrophoretic and mass spectrometric analyses, we demonstrated that UV-laser irradiation of HeLa living cells induces cross-linking between two GAPDH chains, generating cross-linked dimers. Analysis of the high-resolution GAPDH crystal structure [27] supports our findings. A detailed analysis of the distances between aromatic residues shows that W196 and Y42, Y45, Y49 form the most important set of aromatic interactions between the two subunits (Fig. 4b). Given the one-photon excitation mechanism of the here proposed technique, it is likely to hypothesize that the covalent GAPDH homo-dimer formation upon photochemical cross-coupling involves W196 and one of the three tyrosine residues in its proximity, both tryptophan and tyrosine being indeed amino acid residues amongst the most involved in excitation mechanisms induced by UVC light (200–280 nm) [35]. Most notably, these aromatic residues lie at the C2 symmetric R interface, thus a covalent bond would produce only dimers, as experimentally found both in living cells and in vitro.

Spectroscopic analyses, performed on pure GAPDH irradiated in vitro, clearly support the involvement of aromatic residues in the covalent cross-linking between two subunits. Taken together, all the spectroscopic data suggest that a new chromophore, absorbing around 330 nm, is produced upon laser irradiation. Concomitant changes were detected in both UV–Vis and fluorescence spectra. In particular, fluorescence emission generated upon 340 nm excitation can be attributed to the presence of highly conjugated aromatic moieties, in agreement with literature data [32]. Aryl substituted tryptophans in position 2 have been previously synthesized via Pd-catalysed Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling [32]. Taking these unnatural amino acids as models for a tyrosyl-tryptophan cross-coupling product, we found that their UV–Vis and fluorescence spectral features fairly correlate with our results, thus suggesting that a cross-coupled aromatic moiety is produced upon laser irradiation.

Analysis of CD spectra gives further insights into the molecular mechanism occurring after cross-coupling. The lower intensities of the positive and negative bands in the far-UV region, upon laser irradiation, can be related to a decrease in the secondary structure content, or to a change in the oligomerization state, as already reported for GAPDH [33, 34]. A more evident decrease in spectrum amplitude is observed in the near-UV region, further confirming that aromatic residues are involved in the cross-coupling event. The observed CD variations are generally interpreted as a partial transition to a molten globule state [36], which in the case of the GAPDH has been correlated to a lower oligomerization state [33, 34]. It can be argued that the observed changes in the CD signals are related to degenerative oxidative processes, triggered by the laser in vitro, differently from what observed in living cells. The decrease of the near-UV signal amplitude has been indeed reported for GAPDH, upon exposure to chemical oxidative stress [37, 38] and it has been related to non-native amyloid-like aggregates. In that case, differently from our results, such a decrease in the near-UV region was accompanied by an increased signal amplitude in far-UV region. Our results well fit with a mechanism of tetramer destabilization upon covalent dimer formation. In conclusion, the results herein reported strongly confirm the formation of specific cross-linked species through aromatic residues triggered by laser irradiation.

The procedure herein proposed is a fast, reproducible and controlled process. It is fast, as the time needed for cross-linking induction is much shorter (seconds) than that required for conventional methodologies applied to living cells. It is a controlled process, as the energy dose can be modulated accurately to optimize cross-linking in a given experimental system.

The linear response of protein–protein cross-linking in living cells to the laser intensity led us to highlight that the cross-linking event is triggered by the absorption of a single UV-laser photon by aromatic side chains. This makes the process basically different from that occurring in the case of protein-DNA photoinduced cross-linking, from a microscopic point of view. For DNA–protein cross-linking, in fact, the reaction proceeds in two steps: (1) bi-photonic UV light absorption [39–41] and excitation of the DNA bases, in the nanosec-, picosec- or even femtosec-time scale; (2) cross-linking with proteins interacting with the DNA excited site and therefore lying nearby (zero-length cross-linking), which is completed in less than 1 millisec [39–41].

It is also important underlying the reproducibility and high cross-linking efficiency of this novel technique as compared to many of the presently available alternatives, based on the use of chemicals. The yield of the cross-linked products was found to be about 10 %, suggesting that 10 % of total GAPDH chains are cross-linked as dimers upon UV-laser irradiation. Hence, our method turns out to be approximately 5 times more efficient than conventional formaldehyde cross-linking [41], and its efficiency is comparable to that of recently developed single-molecular-interaction sequencing (SMI-seq) technology for in vitro analyses [42]. Therefore, LUCK technology has the potentiality to become a universal technique to photo-fix protein interactions, as in principle it may be applicable to any biological context, such as the intracellular milieu of living cells, to unveil protein–protein interactions in a native context.

Moreover, due to the ultra-short time scale of UV-laser-induced cross-linking, this technique might allow to unveil transient interactions between proteins in a native context, differently from most of the methods based on the chemical induction of bonds between partners.

Materials and methods

Materials

All reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, unless differently specified. Protein G Sepharose was from GE Healthcare. The chemiluminescence detection system (SuperSignal® West Pico) was purchased from Pierce. Protease inhibitors cocktail was from Roche. HeLa cells (ATCC) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10 % foetal bovine serum (FBS), 4 mM l-glutamine and penicillin–streptomycin (50 U/mL), in a 5 % CO2 humidified atmosphere at 37 °C. Anti-GAPDH antibodies were from Ambion (monoclonal) and from Proteintech (polyclonal). Anti-mouse and anti-rabbit secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxide enzyme (HRP) were from Thermo Scientific.

UV-laser irradiation of living HeLa cells

To irradiate HeLa living cells, a powerful source of UV radiation, a custom-made version of the PHAROS laser system (Light Conversion Ltd., Vilnius, Lithuania, see the company website at http://www.lightcon.com/) was used. This is a very compact femtosecond amplified laser source—a single-unit integrated system, combining up to millijoule pulse energies and high average output power. This system, based on the new Yb:KGW lasing medium and on a very compact Chirped Pulse Amplification scheme, emits 1.3 mJ, 170 femtosec pulses, centred at 1030 nm, at a repetition rate of 2 kHz, corresponding to an average power of 2.5–2.6 W. The repetition rate can be increased up to 200 kHz, where the average output power reaches nearly 7 W. The IR pulse is then frequency up-converted into a harmonic generator stage (HIRO) where II (515 nm), III (343 nm), and VI (257 nm) harmonic pulses, lasting about 250 femtosec, are obtained. The system is equipped with a sophisticated pulse picker which allows one to separately select any possible repetition rate, from single-shot to 200 kHz.

For UV-laser irradiation, HeLa cells were detached by trypsin–EDTA and suspended in phosphate buffer (PBS 1X) at a density of 4 × 105 cells/mL. Cells were then placed in a cuvette containing a magnetic stirrer to ensure continuous agitation of the cell suspension during irradiation and uniform irradiation conditions.

UV-laser irradiation of GAPDH in vitro

In vitro cross-linked GAPDH was prepared by irradiating the protein isolated from rabbit muscle (65 µM, 500 µL total volume). To this purpose, lyophilized GAPDH was dissolved in 50 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.5 and placed in a cuvette containing a magnetic stirrer. Irradiation was then performed under the following conditions: 5 s irradiation time, 100 µJ pulse energy, 2 kHz repetition rate and 1.0 J total irradiation energy.

Cell extracts and immunoprecipitation

Following irradiation, cells were centrifuged at 2300g for 5 min. For total protein extraction, the cell pellet was resuspended at a density of 1 × 104 cells/µL in PBS 1X containing 1 % NP-40 and protease inhibitors cocktail (Roche, Germany). After 30 min on ice, lysates were centrifuged at 14,000 g for 30 min at 4 °C. Soluble protein concentration was determined by the Bradford assay. UV-laser-induced cross-linking was analysed by Western blotting of total proteins extracted from control and irradiated cells by the use of monoclonal anti-GAPDH antibodies.

For immunoprecipitation (IP) experiments, protein extracts (300 µg) were diluted in 0.01 % Tween-20 in PBS (1 µg/µL final concentration) and incubated with polyclonal anti-GAPDH-specific antibodies (3 µg) overnight at 4 °C on a shaker. After incubation with protein G Sepharose (60 µL) for 1.5 h at room temperature, the sample was centrifuged, washed, and bound proteins eluted in 2 % SDS and 10 % glycerol in 0.125 M Tris–HCl, pH 6.8. Selected proteins were analysed by Western blotting with anti-GAPDH monoclonal antibodies.

Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis

Protein extracts were obtained as described above. For each sample, 200 μg of proteins were precipitated using the 2D Clean-Up Kit (GE Healthcare). After precipitation, the pellet was mixed with 125 μL of rehydration buffer (6 M urea, 2 M tiourea, 0.4 % CHAPS, 1 % bromophenol blue), 3 μL of 1 M DTT and 2.5 μL of pH 3–10 nl IPG buffer (GE Healthcare). Samples were loaded in duplicates onto 7 cm Immobiline™DryStrip gels strips (GE Healthcare) with a non-linear pH range of 3–10 using an isoelectric focusing system (EttanIPGphoreIII). Strips were rehydrated (20 °C, 16 h) and isoelectric focused (500 V for 1 h, 1000 V for 1 h, 5000 V for 3 h, held at 5000 V, 6000 V for 3 h, and held at 6000 V for 5 h to reach 15,000 V total energy). The maximum current was maintained at 50 μA per strip. Strips were subsequently reduced and alkylated twice (15 min each) in equilibration buffer [50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.8, 6 M urea, 30 % (v/v) glycerol, 2 % (w/v) SDS, and 0.03 % bromophenol blue] with 65 mM DTT and 135 mM iodoacetamide. Strips were subjected to the second-dimensional separation (Ettan DALTsix) using a SDS–polyacrylamide gel (12.5 %). SDS-PAGE was carried out by standard methods with a constant voltage (180 V) at room temperature. A set of samples was then stained with colloidal Coomassie Brilliant Blue, while a second set of samples was electroblotted for Western blot analysis.

Protein identification

Protein identification by mass spectrometry was performed on Coomassie Blue stained spots from 2D gels and on bands excised from monodimensional gels. Excised spots/bands were destained by repetitive washes with 0.1 M NH4HCO3, pH 7.5 and acetonitrile. Enzymatic digestion was carried out with 100 ng of proteomic grade trypsin (Sigma) in 10 mM NH4HCO3 buffer, pH 7.5. Samples were incubated for 2 h at 4 °C, then trypsin solution was removed and a fresh trypsin solution was added and samples were incubated for 18 h at 37 °C. Peptides were then extracted by washing the gel spots/bands with acetonitrile and 0.1 % formic acid at room temperature and then were filtered using 0.22 µm PDVF filters (Millipore) following the recommended procedure.

The resulting peptide mixtures were analysed by nanoLC–MS/MS, on a CHIP MS 6520 QTOF equipped with a capillary 1200 HPLC system and a chip cube (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, Ca). After sample loading, the peptide mixture was first concentrated and washed at 4 µL/min in 40 nL enrichment column (Agilent Technologies chip), with 0.1 % formic acid in 2 % acetonitrile. The sample was then fractionated on a C18 reverse-phase capillary column (75 µm × 43 mM in the Agilent Technologies chip) at a flow rate of 400 nL/min, with a linear gradient of eluent B (0.1 % formic acid in 95 % acetonitrile) in A (0.1 % formic acid in 2 % acetonitrile) from 7 to 60 % in 50 min. Peptide analysis was performed using data-dependent acquisition of one MS scan (mass range from 300 to 2000 m/z) followed by MS/MS scans of the five most abundant ions in each MS scan. MS/MS spectra were measured automatically when the MS signal surpassed the threshold of 50,000 counts. Double and triple charged ions were preferably isolated and fragmented. Each LC-MS/MS analysis was preceded and followed by blank runs to avoid carryover contamination.

Data handling

The acquired MS/MS spectra were transformed in Mascot Generic format (.mgf) and used to query the SwissProt database 2015_01 (547,357 sequences; 194,874,700), with taxonomy restriction to Human (142,140 sequences), for protein identification with a licensed version of MASCOT software (www.matrixscience.com) version 2.4.0. Mascot search parameters were: trypsin as enzyme; 3, as allowed number of missed cleavages; carbamidomethylation of cysteines as fixed modification; 10 ppm MS tolerance and 0.6 Da MS/MS tolerance; peptide charge from +2 to +3. Possible oxidation of methionine and the formation of pyroglutamic acid from glutamine residues at the N-terminal position of peptides were considered as variable modifications. We also searched for known photo-oxidation products, as described by Plowman [31]. Peptide score threshold provided from MASCOT software to evaluate quality of matches for MS/MS data was 10. Individual ion score threshold provided by MASCOT software to evaluate the quality of matches in MS/MS data was 22. Only proteins presenting two or more peptides were considered as positively identified.

UV, fluorescence and CD spectroscopies

The spectroscopic characterization was carried out with commercially available GAPDH from rabbit muscle in 50 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.5, at a final concentration of 65 µM (ɛ 280 = 29,910 M−1 cm−1). All acquired spectra were conveniently subtracted from blank contribution. The UV–Vis absorption spectra were recorded in 0.33 cm path length quartz cuvette. Wavelength scans were performed in the 200–800 nm range, with a 300 nm/min scan rate, 1.0 nm data interval and an average time of 0.0125 s, with the temperature set at 25 °C.

Fluorescence experiments were performed on a Horiba Jobin–Yvon Fluoromax-4 fluorimeter. The spectra were recorded with a reduced volume quartz cuvette with a 1.0 cm path length. Temperature of 25 °C was kept constant by the peltier unit with 2 nm slits. Spectra were recorded in the 300–450 nm region and in the 360–500 nm region with excitation wavelengths of 280 and 340 nm, respectively. Fluorescence spectra were smoothed adopting a Savitzky–Golay filter with a 15 points window.

CD experiments were performed on a Jasco J-815 circular dichroism spectropolarimeter, calibrated for intensity with ammonium [D 10] camphorsulfonate [(θ 290.5) = 7910 °C cm2 dmol−1). Depending on the observed region, the cell path length was 0.01 or 0.33 cm. CD spectra were recorded in the 190–250 nm (far-UV) and 255–375 nm (Soret) regions, at 0.2 nm intervals, with a 20 nm/min scan rate, 1.0 nm bandwidth and a 16 s response. In order to improve the signal to noise ratio, 3 accumulations were collected for the near-UV region. Spectra in the far-UV region are reported in terms of mean residue ellipticity, calculated by dividing the total molar ellipticity by the number of amino acids in the molecule, whereas spectra in the near-UV region are reported in terms of molar ellipticity.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary material 1 Electronic supporting material_Figure 1. Western blot analyses with anti-GAPDH antibodies of total proteins extracted from untreated cells (control) and from cells irradiated under the experimental conditions detailed in ESM_Table 1 (lanes 1-24). Protein samples in a, b and c refer to experimental conditions tested at constant energy dose (4.0 J). Protein samples in d and e were obtained by varying total irradiation energy between 2.4 and 4.4 J.(TIFF 2143 kb)

Supplementary material 2 Electronic supporting material_Figure 2. SDS-PAGE analyses of UV-laser irradiated and control HeLa cell extracts immuno-selected by anti-GAPDH antibodies. Gel was cut into 12 slices (denoted by boxes 1–12) to be analysed by mass spectrometry; the results of slice-by-slice protein identification are reported in ESM_Table 3. M, molecular mass markers. (TIFF 3359 kb)

Supplementary material 3 Electronic supporting material_Figure 3. Aromatic residues distance matrix as measured from human GAPDH crystal structure (PDB ID 1U8F). Distances are reported in angstroms and are highlighted in a heat map (blue/close, red/far) for visualization clarity. (TIFF 4461 kb)

Acknowledgments

This research was partially supported by “Programma STAR” of University of Naples Federico II, “Compagnia di San Paolo” and “Istituto Banco di Napoli—Fondazione”. We acknowledge the STRAIN PROJECT (POR Campania FSE 2007/2013 CUP B25B0900000000), which provided a postdoctoral fellowship to M.C. The authors are deeply indebted to Professor Gennaro Marino for his interest in this work and very useful comments and suggestions.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

F. Itri, D.M. Monti were contributed equally to the paper.

References

- 1.Goodsell DS, Olson AJ. Structural symmetry and protein function. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2000;29:105–153. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.29.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levy ED, Pereira-Leal JB, Chothia C, Teichmann SA. 3D complex: a structural classification of protein complexes. PLoS Comput Biol. 2006;2:e155. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tang X, Bruce JE. Chemical cross-linking for protein-protein interaction studies. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;492:283–293. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-493-3_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Subbotin RI, Chait BT. A pipeline for determining protein-protein interactions and proximities in the cellular milieu. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2014;13:2824–2835. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M114.041095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sinz A. Chemical cross-linking and mass spectrometry to map three-dimensional protein structures and protein-protein interactions. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2006;25:663–682. doi: 10.1002/mas.20082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruce JE. In vivo protein complex topologies: sights through a cross-linking lens. Proteomics. 2012;12:1565–1575. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201100516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang H, Tang X, Munske GR, Tolic N, Anderson GA, Bruce JE. Identification of protein-protein interactions and topologies in living cells with chemical cross-linking and mass spectrometry. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2009;8:409–420. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800232-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walzthoeni T, Leitner A, Stengel F, Aebersold R. Mass spectrometry supported determination of protein complex structure. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2013;23:252–260. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2013.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guerrero C, Tagwerker C, Kaiser P, Huang L. An integrated mass spectrometry-based proteomic approach: quantitative analysis of tandem affinity-purified in vivo cross-linked protein complexes (QTAX) to decipher the 26 S proteasome-interacting network. Mol Cell Proteomics MCP. 2006;5:366–378. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500303-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sinz A. The advancement of chemical cross-linking and mass spectrometry for structural proteomics: from single proteins to protein interaction networks. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2014;11:733–743. doi: 10.1586/14789450.2014.960852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gingras A, Gstaiger M, Raught B, Aebersold R, Raught RAB. Analysis of protein complexes using mass spectrometry. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:645–654. doi: 10.1038/nrm2208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chavez JD, Weisbrod CR, Zheng C, Eng JK, Bruce JE. Protein interactions, post-translational modifications and topologies in human cells. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2013;12:1451–1467. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M112.024497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zheng C, Yang L, Hoopmann MR, Eng JK, Tang X, Weisbrod CR, et al. Cross-linking measurements of in vivo protein complex topologies. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2011;10(M110):006841. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M110.006841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaake RM, Wang X, Burke A, Yu C, Kandur W, Yang Y, et al. A new in vivo cross-linking mass spectrometry platform to define protein-protein interactions in living cells. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2014;13:3533–3543. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M114.042630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lougheed KE, Bennett MH, Williams HD. An in vivo crosslinking system for identifying mycobacterial protein-protein interactions. J Microbiol Methods. 2014;105:67–71. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2014.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suchanek M, Radzikowska A, Thiele C. Photo-leucine and photo-methionine allow identification of protein-protein interactions in living cells. Nat Methods. 2005;2:261–267. doi: 10.1038/nmeth752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin S, He D, Long T, Zhang S, Meng R, Chen PR. Genetically encoded cleavable protein photo-cross-linker. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:11860–11863. doi: 10.1021/ja504371w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leo G, Altucci C, Bourgoin-Voillard S, Gravagnuolo AM, Esposito R, Marino G, et al. Ultraviolet laser-induced cross-linking in peptides. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2013;27:1660–1668. doi: 10.1002/rcm.6610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petrotchenko EV, Borchers CH. Crosslinking combined with mass spectrometry for structural proteomics. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2010;29:862–876. doi: 10.1002/mas.20293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keskin O, Gursoy A, Ma B, Nussinov R. Principles of protein-protein interactions: what are the preferred ways for proteins to interact? Chem Rev. 2008;108:1225–1244. doi: 10.1021/cr040409x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones S, Thornton JM. Principles of protein-protein interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1996;93:13–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mezei M. Statistical properties of protein-protein interfaces. Algorithms. 2015;8:92–99. doi: 10.3390/a8020092. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Falchi F, Caporuscio F, Recanatini M. Structure-based design of small-molecule protein–protein interaction modulators: the story so far. Future Med Chem. 2014;6:343–357. doi: 10.4155/fmc.13.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sirover MA. Structural analysis of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase functional diversity. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2014;57:20–26. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2014.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henderson B, Martin AC. Protein moonlighting: a new factor in biology and medicine. Biochem Soc Trans. 2014;42:1671–1678. doi: 10.1042/BST20140273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chuang DM, Ishitani R. A role for GAPDH in apoptosis and neurodegeneration. Nat Med. 1996;2:609–610b. doi: 10.1038/nm0696-609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jenkins JL, Tanner JJ. High-resolution structure of human d-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62:290–301. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905042289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boyd RW (2008) Nonlinear optics. Elsevier Academic Press, ISBN:0123694701

- 29.Valadan M, D’Ambrosio D, Gesuele F, Velotta R, Altucci C (2015) Temporal and spectral characterization of femtosecond deep-UV chirped pulses. Laser Phys Lett 12: 025302. IOP Select http://iopscience.iop.org/1612-202X/12/2/025302/article

- 30.Altucci C, Nebbioso A, Benedetti R, Esposito R, Carafa V, Conte M, et al. Nonlinear protein—nucleic acid crosslinking induced by femtosecond UV laser pulses in living cells. Laser Phys Lett. 2012;9:234–239. doi: 10.1002/lapl.201110122. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Plowman JE, Deb-Choudhury S, Grosvenor AJ, Dyer JM. Protein oxidation: identification and utilisation of molecular markers to differentiate singlet oxygen and hydroxyl radical-mediated oxidative pathways. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2013;12:1960–1967. doi: 10.1039/c3pp50182e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams TJ, Reay AJ, Whitwood AC, Fairlamb IJ. A mild and selectivePd-mediated methodology for the synthesis of highly fluorescent 2-arylated tryptophans and tryptophan-containing peptides: a catalytic role for Pd(0) nanoparticles? Chem Commun (Camb) 2014;50:3052–3054. doi: 10.1039/c3cc48481e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pappenberger G, Schurig H, Jaenicke R. Disruption of an ionic network leads to accelerated thermal denaturation of d-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase from the hyperthermophilic bacterium Thermotoga maritima. J Mol Biol. 1997;274:676–683. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.He RQ, Li YG, Wu XQ, Li L. Inactivation and conformation changes of the glycated and non-glycated d-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase during guanidine-HCl denaturation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1253:47–56. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(95)00145-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pattison DI, Rahmanto AS, Davies MJ. Photo-oxidation of proteins. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2011;11:38–53. doi: 10.1039/C1PP05164D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fasman GD. Circular dichroism and the conformational analysis of biomolecules. New York: Springer Science & Business Media; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakajima H, Amano W, Fukuhara A, Kubo T, Misaki S, Azuma YT, et al. An aggregate-prone mutant of human glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase augments oxidative stress-induced cell death in SH-SY5Y cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;390:1066–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.10.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakajima H, Amano W, Kubo T, Fukuhara A, Ihara H, Azuma YT, et al. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase aggregate formation participates in oxidative stress-induced cell death. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:34331–34341. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.027698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kryukov P, Letokhov V, Nikogosyan D, Borodavkin A, Budowsky E, Simukova N. Multiquantum photoreactions of nucleic acid components in aqueous solution by powerful ultraviolet picosecond radiation. Chem Phys Lett. 1979;61:375–379. doi: 10.1016/0009-2614(79)80666-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nikogosyan DN. Two-quantum UV photochemistry of nucleic acids: comparison with conventional low-intensity UV photochemistry and radiation chemistry. Int J Radiat Biol. 1990;57:233–299. doi: 10.1080/09553009014552411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Klockenbusch C, Kast J. Optimization of formaldehyde cross-linking for protein interaction analysis of non-tagged integrin B1. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2010;2010:927585. doi: 10.1155/2010/927585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gu L, Li C, Aach J, Hill DE, Vidal M, Church GM. Multiplex single-molecule interaction profiling of DNA-barcoded proteins. Nature. 2014;515:554–557. doi: 10.1038/nature13761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material 1 Electronic supporting material_Figure 1. Western blot analyses with anti-GAPDH antibodies of total proteins extracted from untreated cells (control) and from cells irradiated under the experimental conditions detailed in ESM_Table 1 (lanes 1-24). Protein samples in a, b and c refer to experimental conditions tested at constant energy dose (4.0 J). Protein samples in d and e were obtained by varying total irradiation energy between 2.4 and 4.4 J.(TIFF 2143 kb)

Supplementary material 2 Electronic supporting material_Figure 2. SDS-PAGE analyses of UV-laser irradiated and control HeLa cell extracts immuno-selected by anti-GAPDH antibodies. Gel was cut into 12 slices (denoted by boxes 1–12) to be analysed by mass spectrometry; the results of slice-by-slice protein identification are reported in ESM_Table 3. M, molecular mass markers. (TIFF 3359 kb)

Supplementary material 3 Electronic supporting material_Figure 3. Aromatic residues distance matrix as measured from human GAPDH crystal structure (PDB ID 1U8F). Distances are reported in angstroms and are highlighted in a heat map (blue/close, red/far) for visualization clarity. (TIFF 4461 kb)