Abstract

Circadian clocks synchronize organisms to the 24 h rhythms of the environment. These clocks persist under constant conditions, have their origin at the cellular level, and produce an output of rhythmic mRNA expression affecting thousands of transcripts in many mammalian cell types. Here, we review the charting of circadian output rhythms in mRNA expression, focusing on mammals. We emphasize the challenges in statistics, interpretation, and quantitative descriptions that such investigations have faced and continue to face, and outline remaining outstanding questions.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00018-015-2072-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Circadian, mRNA expression, Post-transcriptional regulation, Systems biology, Biostatistics

Introduction

Circadian rhythms in gene expression are found in many organisms, and typically in many cell types in metazoans. A broad definition of circadian gene expression encompasses rhythms with a period of ~24 h in the abundance of mRNAs and proteins, rhythms which are generated directly or indirectly by the so-called core circadian clock. These rhythms have broad implications for cellular physiology; in essence, a cell changes its nature according to the time of day.

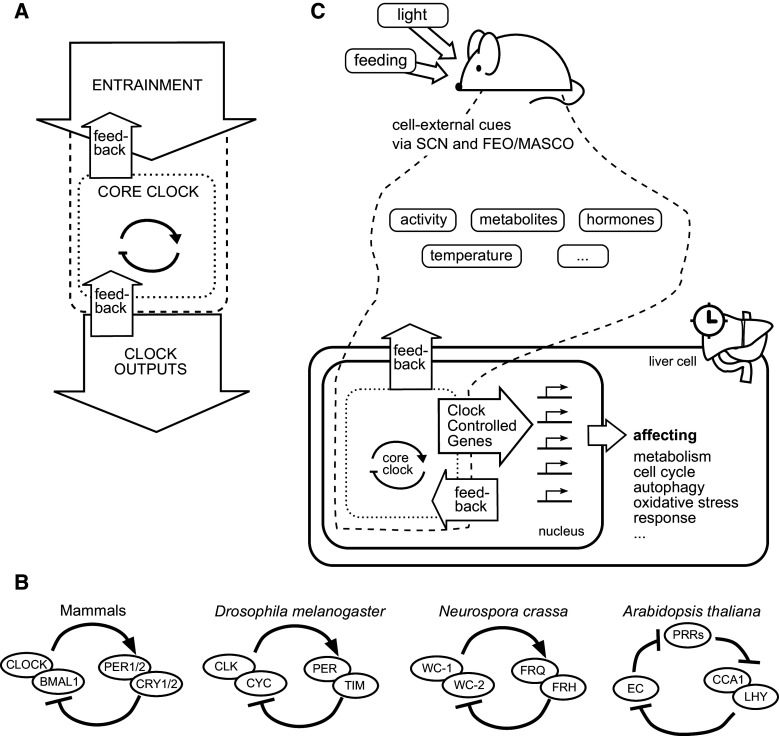

To understand circadian gene expression, it is necessary to first understand the organization of the core circadian clock, which operates both at the cellular and at the organismal level, and ultimately generates rhythms in gene expression. A useful conceptual framework when thinking about circadian clocks is a 3-tiered model [1, 2] (Fig. 1a). This model consists of, first, the core circadian clock, whose nature is summarized below. Second, the core clock has input pathways that enable synchronization (“entrainment”) to input cues ultimately originating in the environment. Third, there are output pathways, which are responsible for generating rhythms in behavior as well as organismal and cellular physiology. The classical definition of circadian rhythms requires such rhythms to persist when an organism is placed in a constant environment without any form of rhythmic conditions. In the model (Fig. 1a), this would mean that the removal of the entrainment arrow would leave the organism with intact rhythmicity in the core clock and the lion’s share of its output. Measuring various facets of this output under constant light conditions, researchers found early on that different organisms generally exhibit slightly different periods in their rhythmicity, a strong piece of evidence in favor of the endogenous nature of circadian clocks [3]. Yet, to prove beyond any doubt that circadian clocks exist according to this definition, a definitive experiment held a selection of organisms on the south pole isolated from any rhythms in ambient light intensity, temperature, or magnetic field strength, in sealed cages placed on rotating discs neutralizing earth’s rotation; the organisms indeed kept their behavioral ~24 h rhythms [4].

Fig. 1.

Overview of the circadian clock and its input and output pathways in the mouse. a Circadian clock (dotted) and its input (dashed) and output. This model could represent an animal, with inputs such as light cues and outputs such as rhythms in arousal. The model could also represent the cellular circadian clock as expanded upon in panel c. b The core clock has similar designs in animals, plants, and fungi. In mammals, TF heterodimer CLOCK/BMAL1 activates transcription of transcriptional repressors PER1/2 and CRY1/2, which target CLOCK/BMAL1-mediated transcription. The Drosophila core clock contains TF heterodimer CLK/CYC (homologs to CLOCK and BMAL1, respectively) that activates transcription of repressors PER (homologous to mammalian PERs) and TIM [5]. The core clock of Neurospora crassa involves transcriptional activators WC1 and WC2 together with the repressor FRQ and helper protein FRH. WC1 might be a homolog of BMAL1 [27]. Finally, the principal negative feedback loop of the Arabidopsis thaliana core clock might be constituted by three transcriptional repressors inhibiting each other in a cyclical layout: a so-called repressilator [29]. Here, PRRs is a group of three proteins (PRR5, PRR7, PRR9); EC stands for evening complex and consists of the proteins ELF3, ELF4, and LUX. c The cellular circadian clock is depicted from the point of view of a hepatocyte, in a specific version of the model in panel a. The circadian clock (dotted lines) becomes entrained via cues (dashed lines) originating primarily from the SCN, but also from two other ~24 h oscillators (FEO, food-entrainable oscillator; MASCO, methamphetamine sensitive circadian oscillator) [37]. The circadian clock and the cues together orchestrate circadian rhythms in the expression of hundreds of genes. Not shown are the probably great number of feedback pathways from peripheral tissues to the SCN [37]

The first circadian clocks probably arose around 2.5 billion years ago in cyanobacteria [5]. In these prokaryotes, ATP-driven circadian cycles in the phosphorylation state of the protein KaiC ultimately orchestrate circadian rhythms in gene expression [6, 7]. One theory for the evolutionary driving force behind the emergence of cyanobacterial circadian clocks is the “escape from light” hypothesis. This hypothesis posits that clocks may have enabled temporal gating of cellular processes that are sensitive to UV or even visible light, such as DNA replication, to the dark part of the day, in this way providing an evolutionary advantage [5, 8, 9]. In plants, fungi, and animals, the same “escape from light” principle may have triggered the independent evolution of circadian clocks, since the proteins involved exhibit no apparent homologies to KaiC [9]. Evidence supporting the “escape from light” principle in eukaryotes includes an evolutionary deep link between photolyases, which use UV light to drive repair of UV-induced DNA damage, and cryptochromes, which are part of the mammalian cellular core circadian clock (described below) and also mediate circadian control over nucleotide excision DNA repair [10, 11]. Another argument in favor of an eukaryotic “escape from light” principle is the coupling observed in various eukaryotic species between the cell cycle and the circadian clock, which might serve to minimize UV-induced DNA damage by gating the cell cycle to appropriate light conditions [12].

Circadian clocks of plants, fungi, and animals also have a cellular origin but a design different to that of the cyanobacterial clocks. The cellular circadian clocks in multicellular organisms consist of networks of transcriptional–translational feedback loops in which transcriptional (co)-activators and -repressors modulate their own levels of expression. It is difficult to put definite limits to these networks; such discrimination depends on the strengths of the interactions considered which is also dependent on context and cell type. The consensus views focus on a few transcriptional (co)-regulators—core clock proteins—that are functional in most cell types of a given organism and that are necessary for a properly functioning cellular core circadian clock. In particular, in plants, fungi, and animals, transcriptional activators and repressors forming transcriptional–translational negative feedback loops are instrumental for the cellular core circadian clock, as demonstrated by several key experiments [13–16] (Fig. 1b). Such negative feedback loops are well understood also from a theoretical perspective [17, 18], and several combined theoretical and experimental studies have elucidated some of the conditions for such oscillations to be stable [19–24]. Central here are transcriptional activators including the mammalian clock proteins BMAL1 and CLOCK that activate the transcription of transcriptional co-repressors such as the PER1 and PER2, as well as the CRY1 and CRY2 (cryptochrome) proteins. These co-repressors exert negative feedback on their own expression by inhibiting the activation mediated by BMAL1 and CLOCK. The circadian clocks in Drosophila and the fungus Neurospora crassa consist of similar feedback loops [25, 26] with proteins partly homologous to those of mammals, at least as far as Drosophila is concerned (Fig. 1b). The homology is much more limited for Neurospora crassa [27], and it is debatable whether the clocks in animals and fungi might have arisen independently or not [5, 9, 28]. There is a stronger case to be made for plants having evolved circadian clocks independently [9]. The plant cellular circadian clock design has been partly elucidated in Arabidopsis thaliana, but is difficult to delineate because of a large number of interconnected feedback loops [16]. One working model is that the transcriptional activation is implemented as a series consisting of two steps of transcriptional inhibition [29] (Fig. 1b).

In mammals, cellular circadian clocks are operative in most, if not all, cell types: Even red blood cells seem to exhibit cellular circadian rhythms generated by mechanisms separate from the canonical transcriptional–translational feedback loop design [30]. The functional outputs of the cellular circadian clocks determine the daily rhythms in physiology and behavior of the host organism. The paired suprachiasmatic nuclei (SCN) in the hypothalamus, consisting of on the order of ~10,000 neurons, each with its own cellular core circadian clock, act as a master regulator of the circadian clocks in the organism. These neurons synchronize to form a collective super-cellular oscillator, which in turn is entrained by the light input of the eyes via partially characterized pathways [31, 32]. The SCN generate rhythmic cues that entrain the circadian clocks of the other 1011–1013 cells in the body (exemplified by the entrainment of liver cells in Fig. 1c). This formidable feat is accomplished by orchestrating hormonal, body temperature, neural, feeding, metabolic, and locomotor activity rhythms that in turn affect peripheral organs and cells in myriad ways, effectively entraining them [33]. Hormonal cues orchestrated by the SCN include glucocorticoids and melatonin [34–37]. Melatonin may, from an evolutionary point of view, bridge the above-described “escape from light” function in ancient unicellular organisms with circadian behavior and sleep in higher animals [38]. Finally, cues from entrained organs may exert feedback on the SCN, although these pathways are incompletely characterized [37].

Traditionally, any ~24 h rhythms in body or cell physiology that do not necessarily persist under constant conditions are termed diurnal rhythms. This terminology is somewhat blurred in this Review, where we will be mainly concerned with peripheral tissues in mouse, in particular the liver, which has served as a prime experimental model for studying circadian gene expression. The hepatocyte (the most numerous cell type in the liver), which has a steady cellular circadian clock, receives various systemic entraining input cues such as hormone, metabolite, or electrolyte levels that may result from the circadian system in a strict sense, or have their origin in other processes with a ~24 h period (Fig. 1c). For the case of cues resulting from feeding, the issue of discriminating between signals originating from SCN-mediated rhythmic cues and from other ~24 h period processes is particularly complex, since there is a so-called food-entrainable oscillator, distinct from the SCN, that is involved in entraining peripheral organs such as the liver [37, 39]. From the point of view of a hepatocyte, it may hence not be important whether a given external cue would persist or not under constant conditions, and we will thus here term all cellular ~24 h rhythms “circadian” rhythms.

Since the cellular core circadian clock in animals to a large part consists of transcriptional (co)-regulators, it directly generates circadian rhythms in the expression of its so-called clock-controlled genes (CCGs), often hundreds or thousands, depending on cell type and context (Fig. 1c) [40]. These are the output pathways of the cellular core circadian clock. Other genes may have circadian rhythms in expression generated primarily by signaling events of systemic origin. Whatever their origin, circadian rhythms in gene expression influence a myriad of cellular functions such as primary metabolism, signaling, autophagy, tissue homeostasis, nucleotide excision repair, and cell cycle progression [41–49]. The charting of cellular processes influenced by the circadian clock is a field still in its infancy, where many important discoveries are bound to lie ahead. One may surmise, however, that the circadian clock serves to start up- and down-regulating processes already before their optimal levels are to be reached. In this way, it enables prediction of physiological states in addition to mere reaction to external demands [2, 50].

Thus, a number of core circadian clock proteins and external cues in general orchestrate circadian rhythms in a much larger set of CCGs. The controlling machinery needs to be flexible enough to be able to generate rhythms of any amplitude and phase (peak time of day) and, furthermore, to be able to adjust these two parameters to changes in physiological state, such as nutritional state. Failure to do so, i.e., circadian misalignment, which can be induced by e.g., shift work, has been linked to a multitude of disease states in mice and humans [51–57]. Therefore, a thorough understanding of the principles of circadian regulation of gene expression is of highest importance for cell biology and physiology in general.

Here, we review circadian mRNA expression from a genomics and systems biology perspective, providing a complementary viewpoint to mechanism-focused molecular biology studies. This means that we focus on recurring themes and general laws or tendencies concerning groups of genes and their products, rather than particular mechanisms, and that we assume a quantitative or semi-quantitative perspective. In particular, we highlight recent findings that point to important contributions of circadian post-transcriptional regulation of mRNA expression in mouse and Drosophila.

The transcriptional output of the circadian clock

As it became clear that animals have an endogenous circadian clock that controls body and organ physiology [58, 59], circadian fluctuations in different biochemical activities, especially enzymatic activities, were noted by several researchers [60–63]. In a few cases, these fluctuating activities were even shown to correlate with abundances of mRNAs encoding the corresponding enzymes [64]. As the circadian core clock was uncovered in an array of seminal studies [15], it was surmised that circadian transcriptional activators might drive such fluctuating activities and mRNA abundances transcriptionally [14, 65–67]. A single transcriptional activator could potentially drive oscillations in a large number of output genes, although it was at the time not known how widespread such circadian output routing is. One of the first such activators to be characterized was the transcriptional activator DBP, which is particularly highly expressed in liver. Rat liver DBP exhibits extraordinarily strong circadian oscillations in its mRNA expression [65]. The rhythms in DBP abundance also provide a link to rhythmic enzyme activity: Rhythmic DBP levels drive circadian rhythms in cholesterol 7α hydroxylase mRNA and protein levels, which correlate with rhythms in enzyme activity [68]. Dbp is still to this day a paradigmatic example of a CCG that mediates circadian rhythms in gene expression.

A systematic charting of circadian mRNA expression became possible with the advent of the microarray technology, which made it possible to address the question as to how widespread the transcriptional output of the circadian clock is on the cellular and tissue level. The first studies emerged in the years 2001–2002, when, among others, Arabidopsis, Drosophila heads, mouse fibroblasts, and mouse heart, SCN, and liver tissues were examined [69–74]. Many similar studies followed, expanding on the range of tissues and also cell lines studied [47, 75–85]. Study designs varied, but always involve samples collected from tissues or cells at different circadian times (CT) or zeitgeber times (ZT). Both these time measures are in hours, with CT being used for studies under constant conditions, such as constant dark, and ZT being used in studies with a rhythmic external cue (zeitgeber) such as light–dark cycles. CT0 (ZT0) represents the start of activity for diurnal animals (lights on), and CT12 (ZT12) is defined as the start of activity for nocturnal animals (lights off). Typically, the number of sample collection time points in the studies mentioned above lies between 6 and 24.

These exploratory studies indeed demonstrated an abundance of transcripts whose levels fluctuate with a circadian rhythm. The phases of circadian transcripts cover the whole 24 h day, with functions pointing in all directions of cellular physiology. In particular, circadian expression of genes related to metabolic enzymes was found to comprise a relatively large part of the circadian clock output in mouse liver [72, 85]. The studies also hinted at extensive circadian regulation of signaling networks influencing diverse functions such as metabolism, cell cycle control, and functions of immune cells [47, 72, 82]. More recently, an extensive atlas of circadian mRNA expression in 12 different tissues of the mouse, measured primarily using Affymetrix microarrays but with additional RNA sequencing controls, was published [40]. This data set constitutes a valuable resource for comparative studies relating different physiological functions to mRNA expression rhythms. Recent studies with high temporal resolution also uncovered other types of rhythms. For instance, Hughes et al. [84] showed that so-called higher harmonics, i.e., 12 and 8 h rhythms in mRNA expression exist too, albeit in fewer transcripts than circadian rhythms. Such 12 h rhythms also exist in functions of entire processes or pathways, such as the ER stress response [86].

A few investigators have studied circadian mRNA expression on a transcriptome-wide scale in mouse liver during non-standard conditions or in genetically modified animals, to investigate the contributions of different circadian input pathways. For instance, Kornmann and colleagues established a conditional liver-specific knockdown system of the Bmal1 gene [87]. The gene was put under doxycycline-dependent repression by REV-ERB alpha, so that when modified mice were given doxycycline-containing food, transcription of the Bmal1 gene was repressed. Such repression of Bmal1 transcription essentially ceases the operation of the cellular circadian clock. Microarrays were hybridized at different times of day both for mice with and without suppressed liver clocks, and, as in other studies, many cycling transcripts with function in carbohydrate and lipid metabolism were identified. Interestingly, 31 transcripts were detected (given the specific statistics employed in the study) that were cycling also in livers with inactive cellular circadian clocks. The circadian rhythms in the abundance of these transcripts must, therefore, be induced by external input cues. Heat-shock transcription factors (TFs), perhaps controlled by body temperature rhythms, were suggested to be partially responsible for this.

Another study examined the influence of circadian rhythms in feeding activity—another fundamental input pathway—on the mouse liver circadian clock [88]. An inverted, daytime restricted feeding schedule was shown to invert the circadian expression patterns of hundreds of genes; similarly, enforced feeding rhythms could restore circadian expression of hundreds of transcripts in Cry1 −/−; Cry2 −/− double knockout mice, which have a non-functional circadian clock. This indicates that input signals from feeding are extraordinary important for circadian gene expression in mouse liver. Interestingly, a slightly more subtle change of feeding regimen, namely the switch from a normal to a high-fat diet, still causes widespread changes, both losses and gains, in rhythmicity of mouse liver mRNA expression levels, changes which are reversible upon a switch back to a normal diet [89]. Similar transcriptome studies have uncovered different contributions to circadian mRNA expression in mouse liver of the histone deacetylases SIRT1 and SIRT6 [90], as well as light-induced circadian mRNA expression patterns in chicken pineal gland clock cells [91].

Because of the central role of the liver in metabolism, and the potential role of circadian rhythms for metabolic enzymes, further studies characterized the circadian metabolome in mouse liver [92, 93]. These studies indeed uncovered pervasive circadian rhythms in the concentration of many metabolites. Also in mouse skeletal muscle, widespread circadian rhythms in metabolite levels were found [94]; this study is also noteworthy since it paired a metabolome and a transcriptome analysis. The question is then how to interpret the circadian metabolome in terms of the circadian transcriptome. As mentioned earlier, there is a wealth of studies on circadian enzyme activities in rodent liver, which could be correlated to circadian mRNA expression levels in a future meta-study. In the specific context of antioxidant enzymes, such correlations were summarized by Patel et al. [95]. The challenging problem remains, however, how to connect rhythmic enzyme activities to rhythmic metabolite concentrations. The expression of genes coding for enzymes that catalyze rate-limiting steps in metabolism has been predicted to dictate circadian function of entire pathways [72, 92]. In certain cases, this may be true: Such an example is serotonin N-acetyltransferase, an enzyme involved in melatonin synthesis [96]. We note, however, that true rate-limiting steps in metabolism are rare [97, 98]. Rather, concerted regulation of several steps in a pathway is almost always needed to achieve a marked regulation of flux through the pathway. Consequently, circadian regulation of entire pathways or processes (hereafter: higher-level processes) realized by many components (such as enzymes or proteins involved in signal transduction) must generally be realized via circadian regulation of several individual components, in a properly concerted fashion so that amplitudes add up rather than cancel each other out. An example of a higher-level process would be a metabolic pathway governed by several individual enzymes, such as adrenal corticosterone biosynthesis, a pathway whose enzymes exhibit a wealth of circadian rhythms in their mRNA expression levels [76]. The flux through a metabolic pathway is regulated at the level of the individual enzymes, and there are probably universal laws that govern circadian regulation of higher-level processes: flux through a metabolic pathway is unlikely to vary with a circadian rhythm if the enzyme activities are rhythmic with random phases. Such laws must be uncovered by a combined experimental and theoretical approach rooted in biochemical kinetics; we anticipate such work to advance the understanding of the circadian clock output.

How many clock-controlled genes are there?

As with all genome-wide studies, measurement noise and statistical matters such as false discovery rate estimations are central issues in these investigations. Circadian rhythms are most often detected using statistical hypothesis testing against a null hypothesis formulated as some sort of random noise without rhythmic components. Both parametric and non-parametric methods have been developed for this task [99–102], with the non-parametric methods often being found to be more robust to biological variation and measurement errors typically encountered in common assays. In the literature, fixed percentages or numbers of circadian genes are very often given; Statements, for instance, that 5–10 % of mouse liver transcripts exhibit circadian rhythms in their abundances are common. Here, however, it is important to note that such numbers were almost always obtained by applying a false discovery rate cutoff, e.g., 5 %, chosen arbitrary. To obtain a true estimate of the number or percentage of genes with circadian mRNA expression, different but related methods such as the adaptive method described by Benjamini and Hochberg [103] or Storey and Tibshirani [104] should rather be used. The former method yields more conservative estimates: Applying this method [105] to the mouse liver measurements from the circadian gene expression atlas [40], we find that in fact, at least 49 % of expressed transcripts exhibit circadian rhythms in their levels. This may seem like a lot, but one must keep in mind that most of the detectable rhythms have very moderate amplitude and must be suspected to be non-functional. However, as mentioned above, it might still be possible for several low-amplitude components to conspire to create a larger amplitude in a higher-level process, such as autophagic flux [106].

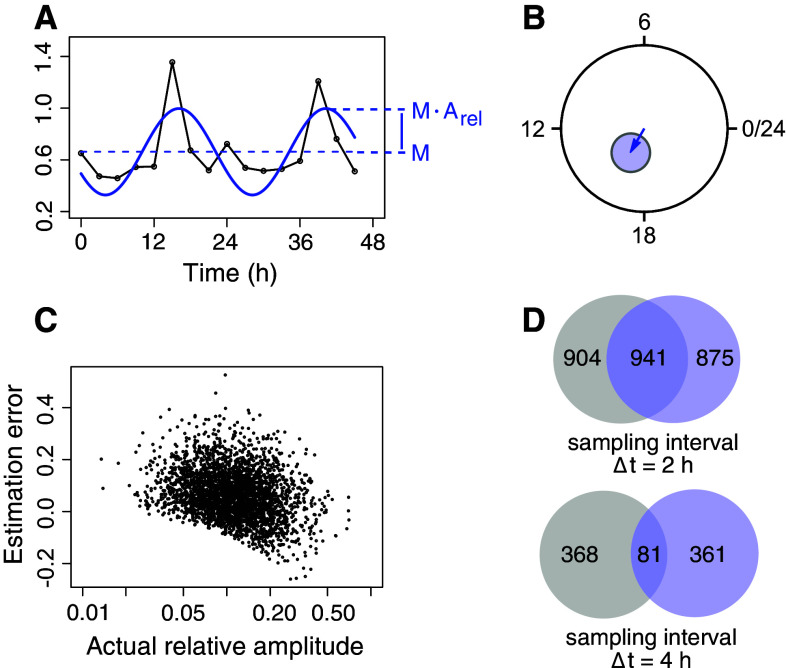

The notion of amplitude must itself be carefully defined to serve as an analysis tool. As is generally the case, relative, dimensionless units such as percentages or fold-changes should in most cases be used, as it allows for comparisons between experiments and conditions by normalizing away systematic errors. One could also argue that biochemical signal propagation often is tuned to fold-change detection than absolute levels [107]. For circadian biology, a normalized (relative) amplitude estimate is easily obtained and defined by dividing the amplitude of a fitted sine curve with the mean measurement intensity (Fig. 2a). This measure has a monotonous one-to-one relationship to amplitudes measured as fold-changes: f = (1 + A rel)/(1 − A rel), where A rel is the relative amplitude and f is the fold-change amplitude. The fit of a sine wave also produces an estimation of the phase, and for both the phase and amplitude, approximate confidence intervals can be obtained [99]. In fact, what one obtains is a so-called confidence ellipse in the plane where amplitude and phase are described by a hand on a 24 h disc (Fig. 2b). For most experimental designs, this confidence ellipse is circular, which has the consequence that the phase can be estimated with far greater relative accuracy than the amplitude (This is easily realized by inspecting the geometry in Fig. 2b). One must further keep in mind that the amplitude estimation with this method is biased: it tends to slightly overestimate amplitudes [108], although this effect fades with higher amplitudes (Fig. 2c).

Fig. 2.

Quantification of circadian mRNA expression. a An overview of measures used when quantifying circadian mRNA expression: M (mean or magnitude), and A (relative amplitude). The absolute amplitude is M × A. b Quantification results in phases and relative amplitudes that can be represented abstractly in a circadian phase plane. The angle then becomes the phase, and the length of the hand (or vector) becomes the relative amplitude. Uncertainties in estimates of amplitudes and phases are represented as 95 % confidence ellipses. c When the number of time points per time series is low, there is a positive bias in the amplitude estimation by the harmonic regression method. Synthetic time series were generated using amplitudes as sampled from harmonic regression estimates of all circadian time series in the mouse liver microarray data of [40]. Circadian time series had RAIN Benjamini–Hochberg adjusted p values smaller than 0.01, for microarray processing, see Table 1. Synthetic time series were generated as six time points sampled evenly at CT0–CT20. White noise was added multiplicatively to produce a coefficient of variation (standard deviation over mean) at each time point of 0.2. d When the number of samples is low, identical populations of rhythmic time series but with different random variability added, can appear to be very different in terms of which time series are rhythmic. Two identical populations of 3000 rhythmic time series were generated as above with the indicated sampling interval. Multiplicative Gaussian noise with a coefficient of variation of 0.2 was generated separately for the two populations. For each population, 7000 time series that were non-rhythmic (amplitude zero), but that had the same noise characteristics, were also generated. Using a Benjamini–Hochberg adjusted RAIN p value cutoff of 0.05 to decide if a time series is rhythmic or not resulted in the overlaps depicted

When restricting the complement of mouse liver circadian transcripts to those with more marked relative amplitudes, say, larger than 0.15 (corresponding to a 15 % variation fluctuation around the mean) and with Benjamini–Hochberg-adjusted RAIN p values smaller than 0.25, its number is much more modest: 1422 (Table 1). This combination of p values and effect sizes (effect size here: amplitudes) for isolating features of interest is generally recommended [109]; as assays get more sensitive and the numbers of samples analyzed in experiments increase, also very small effects without plausible functionality can be endowed with very low p values.

Table 1.

Various features of transcripts of mouse liver genes. mRNA expression was quantified based on microarray experiments [40], using the ENSEMBL mouse gene annotation from the Brainarray project [249], normalized by the standard RMA method. Expressed genes were those with an expression greater than 64

| Expressed, non-circadian | Circadian | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coding seq lengths (total) | 827 | 936 | 0.33 |

| Intron lengths (total) | 15,360 | 21,230 | 2.4 × 10−9 |

| 3′ UTR lengths | 1103 | 1390 | 1.5 × 10−8 |

| 5′ UTR lengths | 233.5 | 284.5 | 1.2 × 10−6 |

| Expressed | Circadian | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of genes | 12,219 | 1422 |

| TFs | 726 | 77 |

| RBPs | 859 | 57 |

Circadian genes were those which were expressed, with a Benjamini–Hochberg adjusted RAIN [102] p value less than 0.25, and a circadian relative amplitude greater than 0.15 (harmonic regression [99, 171]). Expressed non-circadian genes had both RAIN and harmonic regression non-adjusted p values greater than 0.1. Lengths of different features are given as median values. P values refer to two-tailed rank sum tests. TFs were as listed [166], class ‘x’ TFs (dubious) were removed, and human gene IDs were converted to mouse orthologs using BioMart [250]. RBPs were merged lists from Castello et al. and Kwon et al. [227, 228]. For the statistical package R, the parametric method harmonic regression is available at http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/HarmonicRegression/index.html. The non-parametric method RAIN is available at http://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/rain.html

An important question is whether circadian gene expression is tissue specific and how this might relate to tissue physiology. Investigators have begun to address this question mainly by simple comparisons of the complements of circadian transcripts measured in different tissues. The general consensus has been that circadian gene expression is highly tissue specific: Typically, Venn diagrams constructed from the sets of circadian transcripts of two or more tissues, determined by applying an (adjusted) p value cutoff, show moderate overlaps. However, we recommend strong caution when interpreting such analyses: There is no canonic method for determining the absence of circadian rhythms. P values are themselves random variables that strongly depend on measurement noise [110], and thus it will often be the case that the p value falls above the cutoff for one measurement, and below it for a replicate measurement, especially if the amplitudes are moderate. We illustrate this in Fig. 2d, which was generated by simulating two identical populations of rhythmic time series with amplitudes sampled from an actual microarray experiment, and with further added artificial measurement noise. Although being generated by exactly the same amplitude distributions and only differing by the added measurement noise, these time series nevertheless yielded apparently small overlaps in a Venn diagram constructed by applying a p value cutoff, especially for the case with 6 samples taken every 4 h. Although tissue specificity of circadian rhythms is a real and significant phenomenon, it may not always be as pronounced as suggested by Venn diagrams in the literature. The issues raised here in fact apply to any studies concerning changed or vanished rhythms under different conditions. For instance, the cautions apply to the interpretation of (non)-overlaps between sets of genes whose expression are controlled by SIRT1 and SIRT6, respectively [90].

Circadian transcriptional control

How does the core circadian clock induce rhythmic mRNA levels? As mentioned, interest was at an early stage directed especially to circadian transcriptional (co)-activators in the search for master regulators of CCGs. In particular, the idea was that the rhythmic expression of CCGs often might be governed by TFs that are part of the core circadian clock itself. Thus, the circadian TF heterodimer CLOCK/BMAL1, which activates target genes in a circadian fashion by binding to E-box elements in their promoters, was suggested to be an important mediator of the clock output [66, 67]. Rhythmic induction of CLOCK/BMAL1 binding target genes with E-boxes may be generated by rhythmic CRY1-mediated repression of transcription of genes with promoters constitutively bound by CLOCK/BMAL1. However, the most common rhythmic transcriptional regulation of the target genes probably involves rhythmic binding of CLOCK/BMAL1 to promoter E-boxes [111, 112]. In either case, judging by the peak phases of BMAL1, CRY, and PER protein phases in mouse liver [113, 114] and assuming transcriptional activation to peak at the same time, target genes should be expected to exhibit maximal transcriptional activity between CT6 and CT10 in that tissue. Matters are complicated by the fact that flanking DNA sequence might influence the phase of target genes through yet to be characterized mechanisms, possibly involving co-regulators [115], as discussed further below.

The circadian TF DBP was mentioned above; rhythmic transcription by binding of DBP and other PAR-bZIP TFs with rhythmic abundances (TEF, HLF, E4BP4) has since been established as an important factor for circadian rhythms in the expression of clock output genes [116–118]. In mouse liver, the concerted action of PAR-bZIP TFs should cause those target genes that are mainly regulated by these factors to have a peak transcriptional activity during the hours around CT14 [116], again judging by the peak phases of the abundances of these TFs.

Finally, rhythmic repression of transcription mediated by the rhythmically expressed nuclear receptors REV-ERB alpha and REV-ERB beta has been demonstrated to play a large role for the circadian output. In mouse liver, these two nuclear receptors reach their peak abundance at around CT8 or ZT8 [119, 120] and, consequently, since they repress transcription, target gene transcriptional activities peak at around CT20. REV-ERB alpha and REV-ERB beta bind to ROR elements [119], and in at least some tissues in mouse, the nuclear receptors ROR alpha, beta, and gamma, whose circadian expression generally occurs in antiphase to REV-ERB alpha and REV-ERB beta, also bind to ROR elements, thus boosting circadian amplitudes [121].

Mutant mice devoid of the PAR-bZIP proteins DBP, TEF, and HLF exhibit extensive disturbances in the circadian transcriptional output [117]. Similarly, depletion of REV-ERB alpha in a human cell line has widespread effects on mRNA expression, especially of genes coding for metabolic enzymes [122]. Mutant mice with liver-specific REV-ERB alpha and beta deletions, furthermore, exhibit gross disturbances in the circadian rhythms in mRNA expression of hundreds of genes in that organ [123, 124], underscoring the widespread effects of circadian rhythms in the abundances of these TFs. Such direct assessment of the effects of BMAL1 depletion on the circadian transcriptional output is much more difficult to obtain, since mice with a homozygotic null mutation of BMAL1 as a consequence lack a functional cellular circadian clock [125]. However, the binding of BMAL1 to DNA in mouse liver has been charted on a genome-wide scale using ChIP-sequencing technology, and by comparing phases of BMAL1 binding in promoters with transcript abundance phases, a strong case could be made for BMAL1 controlling circadian rhythms in the levels of hundreds of transcripts [111]. To summarize this evidence, these three TF groups—CLOCK/BMAL1, the PAR-bZIP TFs, and REV-ERBs—are often considered as prime mediators of the circadian transcriptional output (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Illustration of factors exerting circadian regulation of transcription rates. TFs bind in a circadian fashion to promoter regions (or downstream of the TSS). Such TFs include CLOCK/BMAL1, PAR-bZIP TFs such as E4BP4, and REV-ERBs. Co-regulators, such as PER and CRY co-repressors, may modify the action of the TFs. TFs and co-regulators conspire to recruit various chromatin modifiers, including histone acetyl or methyl transferases, or histone deacetylases, in a circadian fashion. In turn, this leads to circadian fluctuations in the rate with which Polymerase II is recruited to the core promoter (the region immediately proximal to the TSS). Ultimately, this results in circadian rhythms in transcription rates

For the case of several mouse core clock genes, functional binding sites for the three TF classes in the promoters are abundant and well studied. The Per1 promoter contains five functional CLOCK/BMAL1-binding E-boxes in a region between the transcription start site (TSS) and −4000 base pairs (bp) upstream [126, 127]. The Per2 promoter contains several E-boxes, of which one 20 bp upstream of the TSS clearly dominates rhythm generation [128, 129]. The Rev-Erb alpha promoter has been shown to contain at least two E-boxes, one proximal to the TSS and one in the first intron [130]. The promoter of the Dbp gene harbors four E-boxes (one in the proximal promoter and three intronic) that are necessary for circadian transcriptional activity [114, 131]. The Cry1 gene also has a proximal pair of E-boxes (located between −81 and −57 bp of the TSS) crucial for rhythm generation [115]. However, not only E-boxes are important for the regulation of core clock mRNA expression: Rhythmic mouse Bmal1 transcription is principally driven by REV-ERB and ROR TFs binding to two ROR elements closely upstream of the TSS [119, 132]. In the following, we discuss how rhythmic binding of TFs to promoter elements translates into well-defined rhythms in transcriptional activity. We also discuss how the three main classes of circadian TFs may employ combinatorial transcriptional control to induce the observed broad spectrum of phases in the circadian transcriptional output.

The roles of co-regulators, histone modifications, enhancers, and chromatin remodeling

Many TFs function by binding DNA and recruiting co-regulators (co-repressors and co-activators). The TFs involved in circadian gene regulation are no exception; after all, PER and CRY proteins act as co-regulators of BMAL1-mediated transcriptional activation, and there are other examples concerning the mammalian core clock, such as members of the DBHS family of nuclear factors and the TRAP150 co-activator that also influence BMAL1 action [133, 134].

Some co-regulators influence transcriptional activity by modifying histones, others by inducing chromatin remodeling [135]. These kinds of events influence the recruitment rate and/or transcriptional initiation rate of Polymerase II. Experiments by Etchegaray et al. [136] showed that CLOCK recruits the histone acetyltransferase p300 resulting in rhythmic Histone H3 acetylation levels at the Cry1, Per1, and Per2 promoters, in turn leading to rhythmic Polymerase II binding and transcriptional activity. For the Cry1 promoter, it was shown that there are accompanying changes in chromatin accessibility. Another well-studied example is the Dbp promoter, where rhythmic binding of CLOCK and BMAL1 to its four E-boxes in mouse liver is accompanied by rhythmic transcriptional activity, as well as by rhythmic H3 lysine 4 trimethylation immediately downstream of the TSS, slightly lagging the transcriptional activity in time. Also, the overall H3 occupancy around the TSS fluctuates in a circadian manner [114]. The Dbp locus was also shown to co-localize spatially in a circadian fashion with more than 200 other genes, some of which present circadian transcriptional activities. BMAL1 was implicated in organizing this dynamic spatial chromatin arrangement [137], which may represent coordinated spatiotemporal gene regulation. It remains to be seen whether this finding generalizes to other genes in the circadian transcriptional output. A final example concerns the Bmal1 gene. REV-ERB alpha rhythmically binds to ROR elements close to the transcriptional start site of this transcript, causing circadian transcriptional rhythms [74, 119]. REV-ERB alpha recruits the co-repressor NCOR1 in complex with histone deacetylase 3, which, as shown for different mammalian cell lines, executes repression of transcription of Bmal1 in response to REV-ERB alpha binding [138].

Thus, there is a clear role for histone acetylation and methylation, as well as chromatin remodeling in mediating circadian control of transcription of several core clock genes (Fig. 3). This mode of regulation is also widespread among the circadian output genes. NCOR1 was shown to mediate rhythmic expression of genes many of which code for proteins involved in primarily lipid metabolism, by binding to REV-ERB alpha [139, 140]. Further strong evidence for the role of nuclear receptor co-regulators in energy metabolism came with the discovery that the central co-activator PGC1-alpha itself has a rhythmic abundance in mouse liver, and acts as a co-activator for the ROR TFs; mice with liver-specific knockdowns of PGC1-alpha have strongly disturbed circadian rhythms in the liver clock [141]. The core clock component PER2 has also been shown to act as a co-regulator for nuclear receptors, in this way inducing or modulating circadian rhythms in the expression of nuclear receptor target genes [142].

Studies showing that histone deacetylases SIRT1 and SIRT6 are involved in circadian control of histone acetylation status [90, 143] underscore the widespread role for nucleosomal dynamics and chromatin remodeling in circadian transcriptional rhythms. Histone methylation seems to play a crucial role for circadian mRNA expression of many genes [144–147]. Comprehensive genome-wide data sets on circadian histone acetylation and methylation corroborating an important role for the majority of circadian output genes have also been published [148–150]. A hard unsolved question remains which, and to which degree, circadian TFs in conjunction with co-regulators contribute to these pervasive rhythms in histone status.

Focusing on the histones themselves, Menet et al. [151] showed that nucleosome occupancies as well as levels of the H2A.Z histone variant (which is thought to be more permissive for transcription) exhibit strong circadian rhythms at primarily BMAL1 binding sites. These results were interpreted as BMAL1 being a pioneering TF that is necessary to first loosen DNA–histone interactions so that further TFs can bind and induce transcription. Integration of DNA-binding patterns from several other ChIP-sequencing-based studies further supported this notion [151].

Combinatorial transcriptional control

Recalling that there are at least three important classes of TFs with strongly circadian abundances and occupancies at their cognate DNA-binding sites, a natural question to ask is whether combinatorial circadian regulation of transcription of output genes occurs and if so, what principles may govern such regulation.

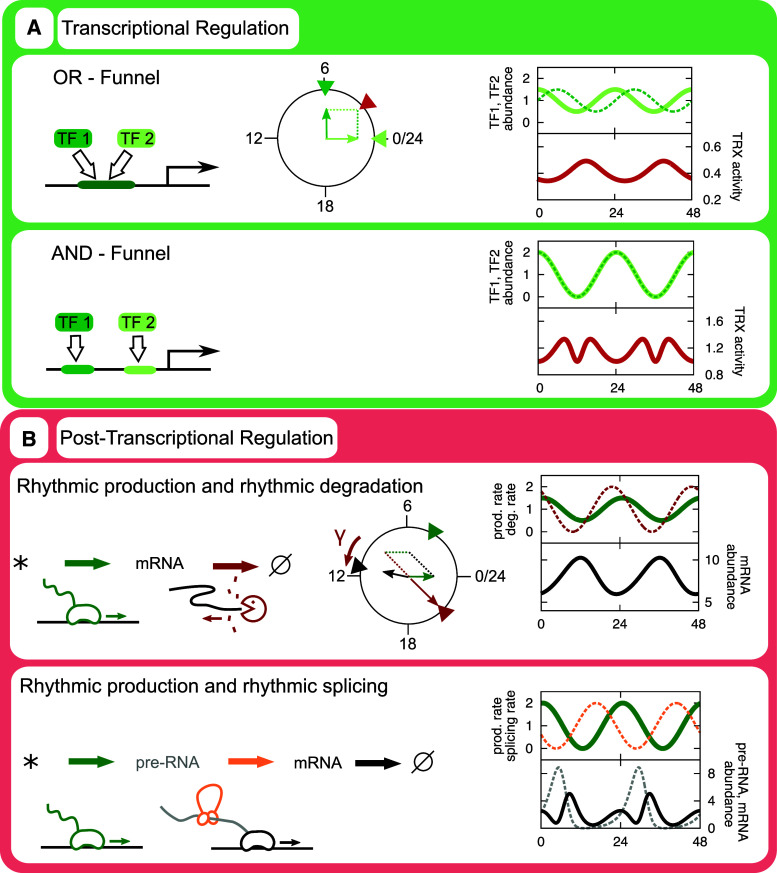

This problem was addressed in a series of experiments involving reporter vectors with synthetic promoters containing different combinations of E-boxes, D-boxes, and ROR elements, in which Ueda and colleagues [120, 121, 152, 153] showed that such combinatorial circadian control of gene expression follows a simple so-called phase vector model (Fig. 4a). For example, the primarily E-box-driven rhythmic transcription of Rev-Erb alpha was proposed to be modulated by PAR-bZIP proteins binding to a D-box more distal to the TSS, and rhythmic transcription of Cry1 was proposed to be modulated by a distal ROR element, explaining the later phase of CRY1 as compared to PER2. Expanding on this notion, Westermark and Herzel [154] showed that combinatorial control of mRNA expression at the proximal promoter regions (within a few hundred base pairs (bp) of the TSS) might account for the observed 12 and 8 h rhythms in mouse liver mRNA expression levels observed by Hughes et al. [84]. Generation of such “overtone” rhythms may occur by combinations of several circadian TFs binding to separate binding sites in the promoters of target genes (Fig. 4a). In addition, however, as shown below, circadian control of any processing steps between nascent and mature mRNA, such as splicing, may in principle also give rise to 12 h rhythms in the abundance of mature mRNA.

Fig. 4.

Combinatorial transcriptional control and effects of rhythmic decay rates. a The action of rhythmic abundances of TFs is additive if they compete for a binding site, multiplicative if they bind to separate sites. Quantitatively, these phenomena can be approximated as vector operations in the circadian phase plane. Here, two TFs, TF1 and TF2, are considered. Light green solid lines refer to the abundance of TF1, dotted dark green lines to TF2, which has a peak phase 6 h later than TF1. The combinatorial effects of the TFs are depicted as red lines. b Also the effect of rhythmic decay rates can be understood as a vector addition of transcriptional activity (green) and decay rate inverted 12 h (red). The resulting vector is adjusted by average decay rate (gamma), which is a good approximation for the phase of the transcript abundance (black). See Lück et al. [171] for details. Extending this model to incorporate splicing activity (orange, dotted) of pre-mRNA (gray, dotted) may result in 12 h rhythms in transcript abundance but not in pre-mRNA abundance. See accompanying Mathematica notebook for equations and solution methods (Supplemental file)

Combinatorial circadian regulation has also been demonstrated for the mouse Per2 promoter [155], where a D-box at ~200 bp downstream of the TSS contributes to increasing the amplitude of transcriptional oscillations, in concert with the E-box 20 bp upstream of the TSS. In fact, there appear to be variants of E-boxes that confer different phases to transcriptional rhythms. The canonical E-box sequence is CACGTC, but the −20 Per2 E-box has the sequence CACGTT [128, 129], which has been termed E′-box [121]. Another variant (CATGTG, termed E′′-box), found 120 bp upstream of the mouse Per2 TSS, was proposed to confer a later transcriptional phase [156]. Similarly, the combination of an E′-box and an E-box between 81 and 57 bp upstream of the mouse Cry1 TSS seems to be able to confer the late Cry1 transcriptional phase: the ROR element may not be needed for this [115]. Thus, an accurate control of circadian transcriptional output phases might be partly achieved by variant TF-binding sites, although the molecular mechanisms are generally not elucidated yet. A possibility is that some variant TF-binding sites attract different competing binding factors. This might be the case for E-boxes in the mouse Per1 and Dbp promoters, for which the competing TF DEC1 was shown to confer a later transcriptional activation phase, in contrast to the primarily E′-box-driven Per2 and Cry1 promoters [157]. Finally, it may be the sheer number of TF-binding sites of a certain type that, rather than binding affinity, is the determining factor for the transcriptional output, as demonstrated in the context of Drosophila development [158]. Along these lines, it has been noted that the 5 E-boxes (including variants) in the mouse Per1 promoter dominate the transcriptional output phase compared to the only D-box [156]. A related effect was observed when varying the number of E-boxes in a reporter construct consisting of the second intron of the mouse Dbp gene: as more E-boxes were inserted, the phase of the reporter readout advanced [159], which is in line with the phase vector model.

Demonstrating combinatorial circadian control of gene expression is substantially more difficult in an in vivo setting, or on a genome-wide scale. One avenue of research has focused on predicting functional binding sites of different TFs in promoters, using e.g., positional weight matrix models [160, 161]. Such predictions are fraught with false-positive predictions [161], but statistical overrepresentation of binding sites for a given TF, e.g., in promoters of genes with circadian mRNA expression as compared to in promoters of genes that are expressed but not in a circadian fashion, may still be detected in this way [162]. An example concerning BMAL1 may serve to illustrate such overrepresentation analysis. The resource SwissRegulon [163] provides TF-binding site predictions for promoter regions (spanning a −300 to +200 nucleotides region around the TSSs), and we may ask whether promoters predicted to have at least one binding site for BMAL1 indeed do exhibit detectable BMAL1 binding. The binding of BMAL1 to DNA in mouse liver was charted on a genome-wide scale by Rey et al. [111] using ChIP-sequencing technology. These investigators annotated 2049 ChIP-sequencing peaks representing BMAL1 binding to specific genomic coordinates, and a comparison of BMAL1 binding predictions with the ChIP-sequencing peaks provides some information about prediction quality. Promoters predicted to bind BMAL1 turned out to be more than sevenfold likely to overlap with actual BMAL1 binding coordinates in the ChIP-sequencing assay, compared to the rest of the promoters (Table 2). This overrepresentation can be formally tested using Fisher’s exact test, which yields a p value on the order of 10−65. Seen in this overrepresentation perspective, the TF-binding site prediction method is thus quite solid. However, if we ask instead how large the percentage is of promoters with measured BMAL1 binding that were also predicted to host binding sites (prediction power), the result is less than 50 %, and the method starts to show some weakness. When instead asking how many of the predicted BMAL1 binding promoters indeed do bind BMAL1, which is the crucial question to ask when investigating a single promoter of interest, the result is sobering: a bit less than 8 % (Table 2). This number must additionally be considered in light of the narrow promoter region considered (500 bp around the TSS). Although many functional binding sites indeed are to be found within such a narrow region, as might be inferred from the specific studies of mammalian core clock promoters summarized above, it is clear that many functional binding sites, as well as enhancer regions, are situated much more distal to the TSS. For instance, of the 2049 ChIP-sequencing peaks analyzed here, 418 overlapped with a −300 to +200 bp promoter region. The 8 % must hence be regarded as an upper limit for the detection power for single promoters. The lesson to be learned is that TF-binding site prediction is a powerful method for inferring biological function on a collective scale. However, it should be routinely viewed in light of an at least around 90 % false-positive rate when focusing on single promoters.

Table 2.

Comparison of predicted and measured BMAL1 binding to proximal promoters (−300 to +200 of RefSeq-annotated TSSs. BMAL1 binding peaks were taken from the ChIP-sequencing study of Rey et al. [111]; overlaps with proximal promoter regions were counted. Numbers in the table refer to promoters with at least one peak or binding site, or with no peaks or binding sites

| Predicted BMAL1 binding | Not predicted BMAL1 binding | |

|---|---|---|

| BMAL1 peak | 155 | 253 |

| No BMAL1 peak | 2011 | 24,812 |

One may note the conceptual problem when isolating the background in studies relying on binding site enrichments in promoters of circadian genes: How to accurately determine non-circadian transcripts? There is no clean solution, as noted above. One might apply non-adjusted p value cutoffs of, say, 0.1, and hope for the best, as is done in the examples in this Review. Still, a few such analyses [89, 93, 154, 164, 165] have yielded some insights. For further work, investigators may keep in mind that in principle, any TF with a circadian pattern of expression may be able to help cause circadian transcriptional activity. Cross-referencing data on circadian mRNA abundances in mouse liver [40] with a census of TFs [166] reveal 77 TFs with circadian mRNA abundances (Table 1). It is still unknown to what degree these rhythms in mRNA expression propagate to rhythmic TF abundances and ultimately to circadian regulation of transcriptional activities. There are, however, examples. One is the TF C/EBP-beta, which has a rhythmic abundance pattern in mouse liver and was shown to strongly influence expression of genes involved in autophagy, in turn leading to a rhythmic pattern of autophagic flux [46]. Autophagy plays a central role in protein catabolism and the maintenance of damaged protein complexes and mitochondria. Other examples were uncovered by Vollmers et al. [88], who cross-referenced feeding induced circadian gene expression with genes known to be induced by a few feeding- and/or stress-related TFs (ATF6, CREB, FoxO1, SREBP1/2), and indeed found significant overlaps. There have also been more direct experimental approaches to discover additional TFs involved in circadian transcriptional control, beyond those acting on E-boxes, D-boxes and ROR elements. The so-called differential display of DNA-binding proteins was employed by Reinke et al. [167], who used this assay to identify the heat-shock factor HSF1 as a circadian regulator of the expression of heat-shock proteins.

To shed light on combinatorial circadian transcriptional control in a genome-wide setting experimentally, the degrees of promoter occupancies by the most important circadian TFs have been charted using ChIP-sequencing technology (as also mentioned above): BMAL1 [111], BMAL1, Clock, Npas2, PER1, PER2, CRY1, and CRY2 [148], and the D-box binding transcriptional inhibitor E4BP4 [118]. These studies all showed correlations between phases of promoter occupancies and corresponding phases of mRNA expression, although these correlations are far from clean. Deviations from such a correlation can be explained both by the fact that promoter binding by a TF is not necessarily functional in terms of regulation of mRNA expression, as well as by contributions of combinatorial control of circadian mRNA expression as outlined above. To what extent these explanations apply to discrepancies between TF promoter occupancies and mRNA expression levels remains to be determined. A modeling study [168] addressed this question, and the results suggest that in principle, the actions of well-known circadian TFs on E-boxes, D-boxes, and ROR elements combined with the phase vector model go a long way to explain a large part of the circadian output.

The role of rhythmic activities of transcriptional co-regulators with regard to combinatorial circadian transcriptional control is a relatively open question. The co-activator PGC1-alpha, which was mentioned above, indeed exhibits a rhythmic abundance and interacts with ROR TFs. However, the dynamic result of a situation where both a TF and one or more of its co-regulators have rhythmic abundances remains to be assessed rigorously.

As transcriptional activators and repressors often act via distal enhancers, Fang et al. [118] examined enhancer activities by quantifying eRNA, a form of RNA transcribed at active enhancer regions, at different ZTs in mouse liver. Indeed, thousands of enhancers with circadian activities were identified, activities which were also shown to correlate with transcriptional activities of nearby genes. Interestingly, in contrast to the combinatorial control and phase vector model suggested for proximal promoter regions, enhancer activities generally appear dominated by a single instance of TF binding. This is a functional mode in line with the enhanceosome scenario [169], involving specific related TFs binding to an enhancer in a cooperative fashion, triggering further regulatory actions. In contrast, a competing scenario for enhancer action, the so-called billboard model, posits that varying cocktails of TFs may bind to a given enhancer, eliciting various degrees of activation [170]. This seems to be more akin to the situation at proximal promoters of genes transcribed in a circadian manner. We anticipate important progress in this line of research when methods for measuring the spatial configuration of chromatin and interactions between different loci, such as chromosome conformation capture variants, are applied to shed light on how circadian rhythms of enhancer activity are reflected in the spatial conformation of chromatin.

Kinetic laws govern circadian transcript abundances

How do rhythmic transcriptional activities propagate to rhythmic transcript abundances? The simplest possible kinetic scheme describing this process is sketched in Fig. 4b. Mathematically, this scheme can be formulated as a linear ordinary differential equation whose simple solution has far-reaching implications: The delay between the transcriptional activity phase and the phase of transcript abundance is between 0 and 6 h [150, 171]. The relative amplitude of transcript abundance is by necessity smaller than that of the transcriptional activity. The phase shift and attenuation of relative amplitude are both functions of solely the transcript half-life: The longer the half-life, the larger the delay and the more dramatic the attenuation of the relative amplitude. These simple qualitative relationships were early pointed out in the context of circadian rhythms by Wuarin et al. [172]. The first studies that compared circadian transcriptional activities and transcript abundances showed that this simple model goes very far in explaining the biology—although certain anomalies spawned an interest in circadian post-transcriptional regulation, as discussed in detail below.

A seldom noticed but interesting factor that may play an under-appreciated role in circadian regulation of transcription is the timing and kinetics of transcription itself [173]. Assuming a transcriptional speed of, say, ~30 bases per second in the mouse liver (a ballpark estimate [174]), just above 100 kB will be transcribed in an hour. Many mouse transcripts are at least this long, with the consequence of an automatic time delay between initiation of transcription and mature exported mRNA on the order of 1 h. In fact, as shown in Table 1, by cross-referencing the set of circadian transcripts as above with transcript lengths, we see that circadian transcripts actually on average are longer than non-circadian transcripts. This contribution of transcript lengths to the delays between transcriptional activity and transcript abundance phases should be taken into account in future studies.

The dynamics of transcript and protein abundances is determined by their half-lives, which are often on the order of hours or more (shorter for mRNAs [175]), so that phase delays and amplitude attenuation occur between rhythmic production or degradation rates and abundances [171]. One might assume dynamics to be different, and faster, in cellular signaling and metabolism, so that circadian rhythms simply correspond to different basal experimental conditions: Predicting the effects of circadian rhythms in this case would only require analyzing varying pseudo-equilibria. However, for common modes of cellular signaling, e.g. phosphorylation/dephosphorylation, reasonable assumptions [176] would lead to elementary rate constants on the order of ~0.1 h−1. Such kinetics would lead to measurable phase shifts and amplitude changes between the circadian stimulus (e.g. kinase activity), and the response (e.g. degree of phosphorylation). This means that circadian rhythms may elicit complex phase shifts and transients in some cellular signaling pathways, and that circadian rhythms cannot always be viewed as slowly changing basal conditions. It may in this case be difficult to discriminate between effects elicited by signal transduction and those elicited by the circadian clock. Similarly, rate constants for metabolic enzymes span many orders of magnitude [177], so that for at least a subset of metabolic enzymes, circadian rhythms would lead to complex transient and phase shifting effects with regard to metabolite concentrations and fluxes. It is, furthermore, likely that some cytosolic mRNA and protein localization processes are slow enough to lead to such complex effects with respect to circadian rhythmicity [178]. On the other hand, RNA export from nucleus to cytoplasm, with typical translocation times of ~1 s [179], might be fast enough to not induce phase shifts or amplitude attenuation on the circadian time scale.

Circadian post-transcriptional regulation and the advent of RNA sequencing

In principle, not only rhythmic transcriptional activities may result in rhythmic mRNA abundances, but also any types of rhythmic regulation of post-transcriptional processes may propagate to mRNA levels [180]. This gives rise to two questions, first, how widespread is such circadian post-transcriptional regulation? Second, are some mechanisms of post-transcriptional regulation preferably exploited by the circadian clock to induce rhythmic mRNA abundances? We will here be concerned with two main post-transcriptional modes of regulation that influence mRNA abundances: regulation of alternative splicing, and various modes of regulation of mRNA degradation. Further post-transcriptional regulatory processes do influence rates of translation; such matters are, however, beyond the scope of this Review.

Post-transcriptional regulation is affected by mRNA-associated factors such as RNA binding proteins (RBPs) and micro-RNAs (miRNAs), which determine the mRNAs’ fate. These factors are subject to dynamical changes that respond to the cellular needs. Together with the mRNA, the complement of factors is referred to as the messenger ribonucleoprotein particle (mRNP) [181–183]. The mRNPs act as adaptors for numerous intracellular machineries that regulate subcellular localization, translation and degradation of mRNA molecules. All mRNA-associated factors act as trans-acting elements that recognize cis-acting binding sites on (pre)mRNAs. Time-dependent or, specifically, rhythmic post-transcriptional regulation might then in principle be generated by rhythmic abundances or activities of RBPs or miRNAs. It might also be achieved by dynamic changes in recognition sites on (pre)mRNAs induced by alternative splicing [184].

More than 1500 RBPs have been identified in humans [185], each on average targeting groups of mRNAs rather than single mRNAs. Also the complement of miRNAs is large: over 1000 have been identified in humans and an estimated 50 % of protein-coding genes may be regulated by miRNAs, with each miRNA on average targeting perhaps tens of mRNAs [186, 187]. In general, miRNAs downregulate gene expression both by inducing mRNA decay and by inhibiting protein translation; both modes of repression require accessory RBP complexes [188]. Also other forms of RNA are involved in post-transcriptional degradation; various forms of long non-coding RNAs may in some cases affect mRNA stability and translational efficiency [189], as may antisense transcripts [190].

Identifying the trans-factors, such as RBPs or miRNAs, is crucial to chart and understand post-transcriptional regulation. However, equally reasonable is starting from the other direction by investigating post-transcriptional modifications of (pre)mRNA regardless of the mediating molecules. Some of the interesting RNA modifications are mRNA splicing, the length of the poly(A) tail and RNA methylation. In mammals, alternative splicing affects approximately 95 and 80 % of genes in humans and mice, respectively [191, 192]. The poly(A) tail is a stabilizing adenosine chain at the 3′end of a mature transcript. During the lifetime of an mRNA molecule, the poly(A) tail becomes shortened in the cytosol by different deadenylases [193]. The speed of this poly(A) tail shortening is not constant: It slows down, pauses; even re-lengthening is possible (see Kojima et al. [194] and references therein). The length of a poly(A) tail is connected to both the half-lives of transcripts and the efficiency by which they are translated. m6A RNA methylation is the post-transcriptional addition of one methyl group (-CH3) to an adenosine. It is a widespread phenomenon and occurs in transcripts corresponding to about 7000 human genes [195]. Fustin et al. [196] identified m6A sites on many clock gene transcripts and showed that specific inhibition of m6A methylation results in a lengthened period of the core clock.

An instance of circadian post-transcriptional regulation was discovered serendipitously by Robinson et al. [197], who noted two different forms of rat SCN vasopressin mRNA, present in different proportions depending on the phase of the external light–dark cycle. This was shown to correspond to different lengths of the mRNA poly(A) tail. So and Rosbash [198] discovered circadian rhythmicity in the Per mRNA half-life in Drosophila; Cheng et al. [199] found alternative splicing of the 3′ UTR of this transcript, which gives rise to two different transcript forms. The mode of splicing was later shown to be temperature and photoperiod-dependent [200] and to contribute to nocturnal locomotor activity on long and hot days, which helps to avoid desiccation of the fly. Mouse core clock transcripts with circadian half-lives have also been noted [201–203]. In these cases, specific proteins bind rhythmically to the 3′ UTRs of the mRNA molecules, which lead to their destabilization varying in a circadian fashion.

As mentioned, deadenylases represent a mechanism by which poly(A) tail lengths and mRNA half-lives are regulated. Nocturnin, one of the mammalian deadenylases, was found to exhibit circadian rhythms at the transcript level in the retina of Xenopus and in several tissues of mice [204, 205]. Although the complement of direct targets of Nocturnin is not known yet [206], corresponding knockout mice have deficits in lipid metabolism, in addition to changes in glucose and insulin sensitivity [205]. Thus, Nocturnin is important for the orchestration of the cellular circadian clock output.

A few other RBPs have been implicated in regulation of the circadian clock or transcripts of CCGs in a rhythmic manner. RBM4, also known as LARK, has a circadian abundance in mouse SCN and Drosophila [207]. LARK is an RBP with two binding domains and is involved in widespread range of post-transcriptional regulation including splicing, translation and RNA silencing [208]. Gene dosage experiments showed that LARK is involved in the timing of eclosion of adult flies [209], a process controlled by the circadian clock [210]. Furthermore, altering the endogenous abundance of LARK in mice leads to an altered core clock period, most likely by affecting the PER1 level [207]. Also worth mentioning is the butyrate response factor (BRF1), which is expressed in a circadian fashion in mouse liver, and recognizes AU-rich elements in the 3′UTR in its targets and destabilizes them [211].

With mounting evidence of various pathways affecting transcript abundances post-transcriptionally, a central question arises as to how widespread such regulation is. In 2012, three groups published studies on mouse liver in which this question was addressed [148, 150, 212]. The overarching strategy was the same in these studies: Comparing the phase discrepancies between circadian transcriptional activities and transcript abundances on a transcriptome-wide scale. Circadian transcripts for which transcriptional activity either appeared arrhythmic or rhythmic with a phase very different from that of the transcript abundance (absence of rhythmic post-transcriptional regulation would lead to transcripts peaking at most 6 h after transcriptional activities as outlined above) were assumed to be subject to significant circadian post-transcriptional regulation. Menet et al. [212] and Koike et al. [148] measured transcript abundances by RNA sequencing, while Le Martelot et al. [150] used microarrays. Transcriptional activities, more difficult to measure, were estimated by Koike et al. as the amount of RNA sequencing reads mapping to introns, while Le Martelot et al. employed a ChIP-sequencing assay for RNA Polymerase II, and assumed intensities of signals mapping to gene bodies as a readout proportional to transcriptional activities. Menet et al. opted to first isolate DNA-associated RNA, enriched for transcribed nascent mRNA, before RNA sequencing in a protocol termed “nascent-seq”. These studies all found a significant amount of rhythmic transcripts either without transcriptional rhythms or with anomalous phase shifts hinting at rhythmic post-transcriptional regulation. In a comment to the study by Koike et al., it was even suggested that a majority of circadian transcripts cycle as a result of rhythmic post-transcriptional regulation [213]. Similar conclusions were made in a follow-up investigation of Drosophila heads, using nascent-seq and standard RNA sequencing [214].

RNA sequencing has also been used to investigate how widespread circadian rhythms in poly(A)-tail length are. Kojima et al. [194] demonstrated that more than 200 transcripts in mouse liver show a circadian rhythm in their poly(A) tail length. Furthermore, genome-wide approaches help to identify factors acting in the post-transcriptional regulation, RBPs and miRNAs, with a circadian abundance including their targets. Using modern sequencing techniques, targets of rhythmic RBPs have also been assayed: The cold-inducible RNA binding protein CIRP as well as the RNA binding protein 3 (RBM3) are rhythmically expressed upon temperature cycles in peripheral tissues [215, 216], possibly suggesting a role in synchronization of peripheral tissues via the body temperature. Identification of the binding sites of both proteins resulted in valuable genome-wide listings of possible target mRNAs. More than 8500 binding sites for CIRP and over 9500 for RBM3 were assigned to annotated transcript regions [216].

Is it possible to obtain more precise estimates of the number of transcripts affected by rhythmic post-transcriptional regulation? To answer this question, a quantitative theory for the combined effect of rhythmic transcription and rhythmic decay rates (the latter being a general effect of rhythmic post-transcriptional regulation) must first be formulated. Lück et al. [171] developed a mathematical model to describe this situation. The model resulted in simple formulae for phases and (relative) amplitudes of transcripts, if phases and amplitudes of transcription and mRNA decay rates are known; these formulas can be represented as vector sums from production and degradation rates, the latter of which is shifted by a half-life-dependent factor (Fig. 4b). The model can also be used to estimate rhythmic decay rates if phases and amplitudes of transcription rates and transcription abundances are known.

To estimate how widespread post-transcriptional regulation is, Lück et al. used this model to develop a statistical test that estimates a p value for the null hypothesis that no rhythmic post-transcriptional regulation takes place. They estimated that at least 30 % of the circadian mouse liver transcripts are affected by rhythmic post-transcriptional regulation. The same test applied on the data from Drosophila heads [214] gives a very similar proportion (34 %) for this organism. Furthermore, transcripts with strong evidence for rhythmic post-transcriptional regulation are overrepresented among RBM3 and CIRBP binding targets, as well as among transcripts with rhythmic poly(A)-tail length.

A further mode of post-transcriptional regulation that is possibly influenced by the circadian clock is mRNA splicing. Using Affymetrix mouse exon-arrays, investigators identified exons with circadian alternative splicing in mouse liver for 0.4 % of genes with detectable transcripts [217]. However, these researchers also demonstrated that circadian alternative splicing is tissue dependent and is modulated by fasting conditions.

Are the consequences of circadian splicing different than those of circadian mRNA decay rates? This has not been systematically investigated, but we can already show by extending our previous mathematical model [171] to incorporate regulated splicing, that circadian rhythms in splicing activity may result in 12 h rhythms in mature transcript abundances (Fig. 4b). Noteworthy is that these 12 h rhythms are not accompanied by 12 h rhythms in pre-mRNA abundances, since the pre-mRNA precisely follows the original model [171], for which 12 h rhythms were ruled out: 12 h rhythms do not arise by any combination of circadian transcriptional activities and circadian decay rates alone. Thus, circadian splicing activities may explain a subset of the 12 h rhythms in transcript abundances [84], and would in particular be predicted if the corresponding transcriptional activities were circadian.

The importance of miRNAs for circadian clocks is unclear. Gatfield et al. [218] examined miR-122 in mouse liver, a highly abundant miRNA [219]. Downregulation of miRNA-122 results in reduction of lipid and cholesterol metabolism [220, 221], processes known to be daytime dependent. Gatfield et al. did observe transcriptional rhythms for miR-122 [218], but due to the long half-life of this miRNA, rhythmicity is absent in its abundance. Vodala et al. [222] used RNA sequencing to identify six oscillating miRNAs in Drosophila heads. These miRNAs seem to be involved in the modulation of immune function, metabolism and feeding behavior. Setting the flies under a different feeding regime, these investigators found that food intake also affects the miRNA levels. By RNA sequencing the mouse liver transcriptome, Vollmers et al. [149] identified 54 miRNAs with cycling abundances. However, functions of these rhythms, such as inducing rhythmic mRNA decay rates, were not ascertained. In fact, miRNA-mediated induction of transcript rhythmicity might not be a widespread phenomenon, as Du et al. [223] found that only 20 out of 1630 rhythmic transcripts change their rhythmicity when faced with a global disruption of the biogenesis of miRNAs. This does not mean that miRNAs are irrelevant for the circadian clock output: The experiment did result in changes in mean abundances in up to 30 % of the rhythmic transcriptome.

Taken together, however, these findings suggest that rhythms in miRNA levels do not generally induce rhythms in gene expression. This is also consistent with results showing that the kinetics of miRNA–target interactions generally are too slow to induce circadian rhythms in mRNA levels [224], as well as with the findings of Lück et al. [171], who failed to observe any overrepresentation in target sites for rhythmic miRNAs among transcripts with significant rhythmic post-transcriptional regulation.

An interesting concept, mRNA regulons, might aid the understanding of higher-level effects of post-transcriptional regulation [225]. In this model, sets of mRNAs that code for proteins involved in shared pathways or processes also share binding sites for specific combinations of RBPs or miRNAs. Keene further proposed that specialized mRNP-compositions might be responsible for coordinated circadian mRNA levels [211].

Since RBPs act primarily on the 5′ and 3′ UTRs of mRNAs [226], the complexity of post-transcriptional regulation of mRNAs should correlate with the length of their UTRs. We surveyed 5′ and 3′ UTRs of mouse liver circadian transcripts, and found that these on average have significantly longer UTRs than expressed transcripts without significant circadian rhythms (Table 1). Also the total intron lengths per gene are significantly larger for genes with circadian mRNA expression. This, together with the results of aforementioned studies, points to an important role for circadian post-transcriptional regulation, possibly largely mediated by rhythmic RBPs. We cross-referenced the set of circadian mouse liver transcripts with a list of 855 validated RBPs [227, 228], and found 57 rhythmic out of 859 expressed transcripts coding for RBPs. This could be compared to 77 circadian out of 726 expressed TF transcripts found when cross-referencing the exhaustive list of TFs compiled by Vaquerizas et al. [166] (Table 1 and Supplementary Table). Hence, routing of the circadian output could be almost as intensively directed through RBPs as through TFs. Here, in the same way as several circadian TFs may synergistically create a large amplitude in the resulting transcriptional activity, several RBPs might in similar ways collectively orchestrate rhythmic regulation of mRNA transport, localization, and decay. Such multiplicative effects have indeed been demonstrated for miRNA action on target mRNAs [229].

Outlook