Abstract

Regeneration is a remarkable phenomenon that has been the subject of awe and bafflement for hundreds of years. Although regeneration competence is found in highly divergent organisms throughout the animal kingdom, recent advances in tools used for molecular and genomic characterization have uncovered common genes, molecular mechanisms, and genomic features in regenerating animals. In this review we focus on what is known about how genome regulation modulates cellular potency during regeneration. We discuss this regulation in the context of complex tissue regeneration in animals, from Hydra to humans, with reference to ex vivo–cultured cell models of pluripotency when appropriate. We emphasize the importance of a detailed molecular understanding of both the mechanisms that regulate genomic output and the functional assays that assess the biological relevance of such molecular characterizations.

Keywords: planarian, regeneration, chromatin, stem cell, genomic, methylation

INTRODUCTION

The observation that certain animals can replace lost body parts has fascinated and puzzled scientists for hundreds of years. The first known recordings of such phenomena were made by Aristotle around 350 BC, when he noted that “if the tails of serpents or lizards be cut off, they will be reproduced” (6, Book II, p.44). Although his inclusion of serpents in this statement is not well supported (3), many succeeding naturalists indeed recorded detailed observations of lizard tail regeneration (38, 51, 104) as well as the restoration of body parts in animals such as hydra (63), planarians (81), snails (17), and frog tadpoles (104). More recently, modern scientists have documented remarkably wide-ranging regeneration in vertebrates such as teleost fish [e.g., the fins, heart, and neural tissues of zebrafish (46)], certain small mammals [e.g., the multilayered skin and ear pinna of African spiny mice (45, 97)], and importantly, male deer [e.g., the annual renewal of antlers (48)]. Humans, however, have a limited regenerative capacity: We can regenerate digit tips only if they are amputated distal to the nail bed (33) and although our liver can restore compensatory mass and function after tissue loss, its shape and vasculature are significantly different (66). Nevertheless, because humans have some regenerative capacity, combined with the complex tissue regeneration displayed by other mammals, it may be possible to reactivate or induce regeneration in humans.

Yet, despite the keen and persistent interest of many brilliant minds over multiple centuries and a critical need for regenerative medicine, regeneration research has proceeded at a painfully slow pace. Even Nobel Prize winner Thomas Hunt Morgan, who spent many years studying the phenomenon and wrote several papers on planarian regeneration, once advised a young scientist that he was “being very foolish”to work on such questions because “[w]e will never understand the phenomena of development and regeneration”(15, p. 949). It is true that we still do not have a clear understanding of the molecular mechanisms that orchestrate various elements of regeneration nor do we know how to exploit such mechanisms to induce nonregenerating tissues or animals to have this extraordinary capacity. However, the field has significantly progressed in recent years through the use of powerful new technologies and tools (25) and, in our view, is on the precipice of making additional breakthrough discoveries.

Regeneration is a complex process that involves many interactions between different cell types, signaling molecules, and genomic loci. Many aspects of animal regeneration, including wound healing and polarity/patterning, have been reviewed previously (21, 38, 75). In this review we focus on how regeneration-competent animals generate what we consider the seeds of regeneration: the cells needed to create new tissues. We discuss the origins of such cells and the molecular mechanisms that regulate their activation upon tissue loss. In particular, we focus on mechanisms that regulate the genome in vivo to control cellular plasticity, as such mechanisms are relatively unexplored in animal models of regeneration. We also discuss how such genomic regulation likely operates in bidirectional feedback loops with extracellular signaling so that together they can orchestrate the regeneration of complex tissues.

THE FOUNTAIN OF YOUTH?

A major question in the field of regeneration concerns the origin of the cells that give rise to newly remade tissue. On the one hand, many tissues undergo constant turnover during normal homeostasis, suggesting that mechanisms are in place to renew such tissues and need only to be upregulated. On the other hand, many organisms mount distinctly different molecular responses to different amounts of tissue loss (12, 70, 121). The type and extent of tissue loss also affect the number of cell types that require replacing, some of which may no longer exist in the remaining tissue. This then raises a related question about the number of cellular sources that must be activated or recruited to produce a new organ or body part.

The stem cell is an obvious candidate to serve as the seed of regeneration competence. The term stem cell derives in part from the word Stammzelle; it was likely used first by Ernst Haeckel in the mid-1800s to describe both the single-celled organism that is the precursor to multicellular life and the single-celled embryo that gives rise to a multicellular organism (87). In due course, other scientists adopted the term and its concept, calling cells that were hypothesized to be the common precursor of a specific tissue its stem cells (119). Scientists studying the hematopoietic system were among the first to adopt this term and its hypothesis and then demonstrate its accuracy (82).

The etymology of stem cells calls attention to the fact that not all cells to which it refers are created equal. The Stammzelle named by Haeckel is more akin to a pluripotent stem cell, which can give rise to every type of differentiated cell needed to create an embryo (92), than to a hematopoietic stem cell, which only can give rise to cells of the blood and bone marrow (73). Understanding the molecular definition and culture requirements for maintaining specific types of stem cells ex vivo has been the focus of much research (68), and the successful development of regenerative medicine strategies is often argued to rest on our understanding of these cells and their ability to differentiate into mature tissues (103). Indeed, the breakthrough development by Takahashi & Yamanaka (109) in creating stable, ex vivo induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) from differentiated fibroblasts makes this an attractive avenue, as it would allow the creation of individualized pluripotent stem cells that could be used to seed the regeneration of missing organs or body parts. Such perfectly matched tissues would be less likely to be rejected by the immune system; iPSC-based regeneration strategies may also provide opportunities to study the (re)development of organs or body parts in the context of specific genetic backgrounds, helping researchers dissect the progression of certain pathologies.

Yet although pluripotent stem cells would appear to be ideally suited as candidates for the cellular seeds of regeneration, studies of regenerating animals suggest that these highly plastic cells are in fact not a common source of newly regenerated tissue [see the section titled Paths to (Pluri)potency]. Moreover, regenerating animals sometimes employ multiple strategies to induce cellular plasticity as they remake a new organ or body part (Figure 1). This leads us to two critical questions: What types of cellular potency are necessary and sufficient to seed successful regeneration? Do such cells mimic their embryonic counterparts? Studies of multiple animal models hint that the answers to these questions may not be predictable and are likely context dependent. In the next section we discuss various strategies used by regenerating animals to induce the production or conversion of cells that serve as the cellular seeds of regeneration.

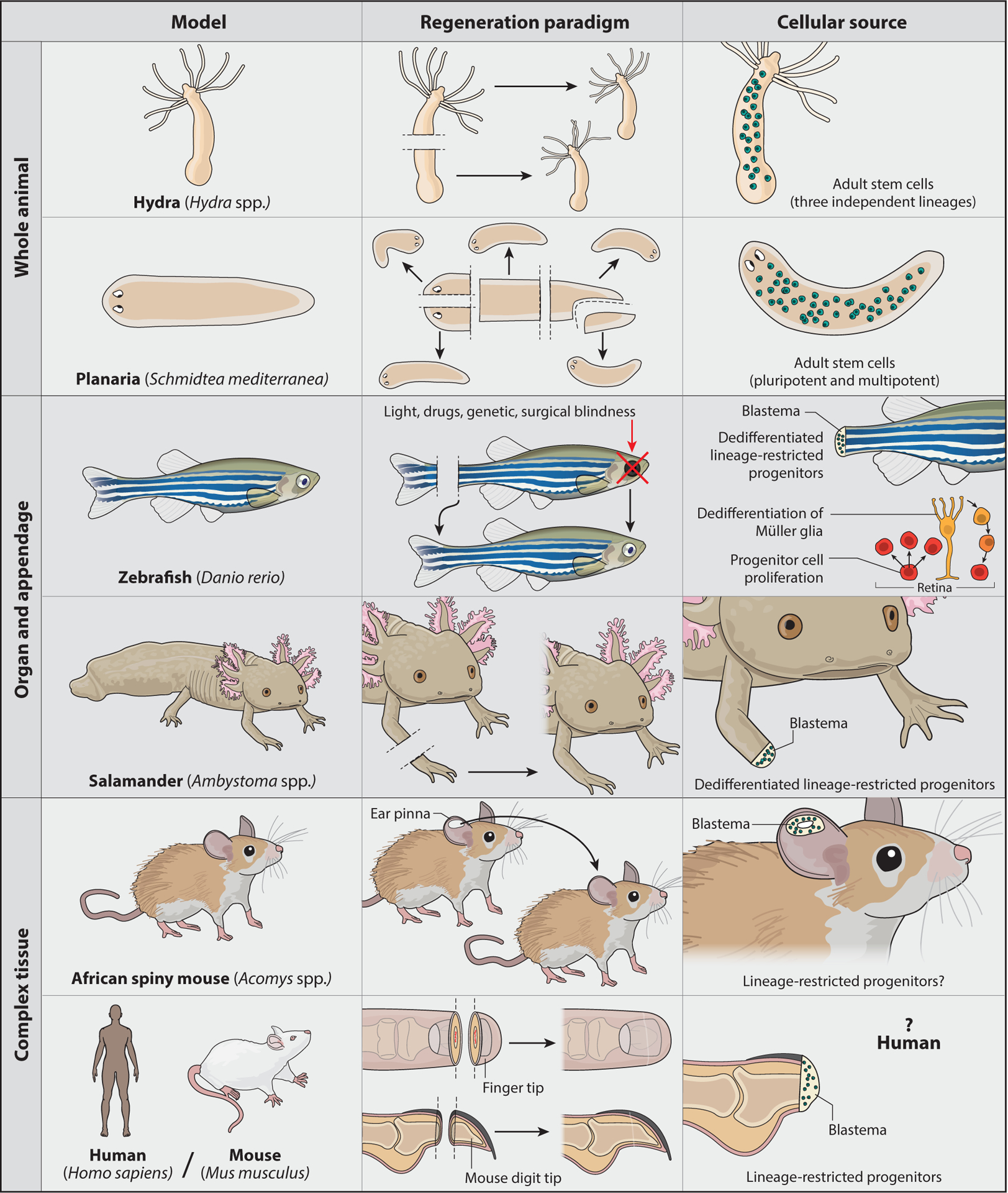

Figure 1.

Animal models of regeneration. (Top) Animals capable of whole-animal regeneration. Animals such as hydra and planarians have expansive regenerative capacities and constantly maintain pools of adult stem cells. (Middle) Animals capable of appendage regeneration. Animals such as the zebrafish and salamander can regenerate appendages and other complex organs. Although many of their tissues are highly similar to those of nonregenerating vertebrates, these animals respond to injury by dedifferentiating cells into lineage-restricted progenitors capable of building new complex tissues. (Bottom) Animals capable of regenerating complex tissues. Although most mammals have limited regenerative abilities, there is evidence of mammalian regeneration. As with zebrafish and salamanders, instances of mammalian regeneration often involve the formation of blastema tissue (versus scar tissue).

PATHS TO (PLURI)POTENCY

Animals with regenerative capacities use a range of strategies to achieve the plasticity required to redifferentiate cells and replace lost tissue (Figure 1). Hydra and planarians, arguably the animal kingdom’s best regenerators, stand at one end of this spectrum. Both animals maintain pools of adult stem cells that not only feed their incredible capacity for regeneration but also make them negligibly senescent, if not immortal; such adult stem cells allow Hydra and planarians to sustain the constant cell turnover of normal homeostasis and avoid senescence (16, 69, 79, 94, 116).

In Hydra, adult stem cells can be divided into three independent lineages: ectodermal epithelial cells, endodermal epithelial cells, and interstitial cells. The independence of these three types of stem cells has been established by lineage tracing (123) and molecular characterization (50). Both epithelial lineages give rise to somatic cell types, whereas the interstitial lineage is more broadly multipotent and gives rise to both somatic and germ cells (18). However, despite their expanded potential, the interstitial cells are dispensable for Hydra regeneration: Hydra depleted of interstitial cells can regenerate nerve-free animals that derive solely from epithelial stem cells and the reincorporation of differentiated cells (44). These results reinforce the conclusion that although Hydra maintains dividing stem cells in the mature animal, they are restricted to specific lineages.

Planarian flatworms also maintain a large pool of stem cells in the adult animal yet, unlike Hydra, at least some of these cells are pluripotent (113, 135). For many years, planarian stem cells were treated as a single cell type, the neoblast (9). Neoblasts are characterized by their ability to incorporate BrdU into their replicating genome, their contribution to differentiated tissues during both normal homeostasis and regeneration, and their expression of specific molecular markers such as the smedwi-1 transcript (37, 49, 79, 90, 131). However, several recent studies have used single-cell expression analyses to show that the planarian stem cell population is much more heterogeneous than previously appreciated (43, 84, 111, 135). Nonetheless, planarian stem cells do not appear to divide into distinct, restricted lineages as in Hydra.

The dynamic plasticity of planarian stem cells is clearly demonstrated in experiments that address the expression and function of the transcription factor (TF)–encoding gene foxA. This pioneering transcription factor is expressed in a subset of stem cells around the pharynx and is required for pharynx regeneration (2), suggesting that these foxA+ stem cells function as pharynx progenitors. However, planarian tissue fragments amputated outside the radius of foxA+ stem cells (e.g., a head fragment amputated just below the photoreceptors) induce foxA expression in a new subset of neoblasts and successfully regenerate a new pharynx (1). The foxA data highlight two important features of planarian stem cells: (a) At least some of the cells in this population must have the ability to activate the expression of any lineage-determining gene as needed, and (b) these cells must receive external signals and have mechanisms to translate them into appropriate changes in gene expression. Indeed, this first feature defines a subclass of stem cells termed clonal neoblasts (cNeoblasts) (113), the existence of which is strongly supported by recent studies describing their developmental origins (30) and molecular signature (135). These recent characterizations of cNeoblasts have finally enabled researchers to carry out detailed and systematic analyses that will unravel the molecules and mechanisms that regulate their function and genomic output.

Whereas both Hydra and planarians draw on their large pools of proliferating adult stem cells to replace lost tissues, studies of regenerating vertebrates reveal that these animals must often induce the generation of cells that comprise a new organ or limb. Teleost fish and salamanders, including the well-established zebrafish and axolotl model systems, have been particularly informative in this regard. Not only are adult zebrafish and axolotls able to regenerate a wide variety of complex organs and appendages, but scientists in these fields have also created many genetic tools to dissect the origins and differentiation potential of cells that contribute to regenerating tissues (59,60,100, 105). As studies tracing the cellular sources of zebrafish fin regeneration and salamander limb regeneration have been thoroughly reviewed elsewhere (25, 76), we do not go into detail here. Briefly, amputation of these appendages induces a subset of the remaining cells to dedifferentiate, or reprogram, back to a progenitor state (Figure 1). Although these reprogrammed cells can now proliferate and differentiate, they remain lineage restricted (e.g., osteoblasts dedifferentiate to osteoblast progenitors and redifferentiate to osteoblasts).

In addition to their ability to regenerate fin and heart tissues, zebrafish can also restore the architecture and function of injured retinas (115). This particular regenerative ability is remarkable both because the retina is part of the central nervous system, which is especially resistant to regeneration, and because most other species cannot regenerate damaged retinas even though they are highly similar in structure and function to zebrafish retinas (47). Retinal regeneration thus provides a powerful opportunity to identify key differentiating mechanisms that confer regenerative ability. In addition, zebrafish derive the cells they need to replenish lost retinal tissue through a combination of strategies used in other contexts: (a) Adult zebrafish maintain pools of retinal stem cells (progenitors) that differentiate into new neurons during both normal growth and regeneration (72, 88); and (b) retinal injury induces dedifferentiation of a specific cell type, the Müller glia, which then redifferentiate into neurons of the inner retina (39, 42) and photoreceptors (12, 88). The choice to activate one or both strategies and the subsequent fate choices of the resulting progenitor cells depend on the specific type of retinal damage. For example, targeted loss of cone photoreceptors increases cone progenitor proliferation as well as Müller glia dedifferentiation, whereas selective loss of rod photoreceptors stimulates mitotic activity in rod progenitors alone and does not activate Müller glia dedifferentiation (72).

Together, the above studies show that acute retinal damage in zebrafish induces signals that are translated by specific cell types into mechanisms that regulate gene expression and, ultimately, cellular plasticity. Uncovering the molecular details of those mechanisms that drive retinal regeneration in zebrafish will not only provide insight into how we might induce this process in mammals, but also inform us more broadly about the molecular differences that distinguish regeneration-competent tissues from those without this ability.

Finally, the maintenance or activation of potency in the few known examples of mammalian regeneration merits some discussion. Among these examples, African spiny mice (multiple Acomys species) and the European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) show great promise as models, particularly as they lend themselves to powerful comparative analyses with regeneration-incompetent Mus musculus. Although the breadth of their regeneration capacity is still being characterized, African spiny mice can robustly regenerate both large areas of damaged skin and the complex, multilayered tissue of their ear pinna; in contrast, M. musculus repairs equivalent injuries with scar tissue (45, 97). Importantly, puncture of the ear pinna in Acomys induces the formation of a blastema, a specialized tissue that forms at the amputation site in many regenerative organisms (16, 98). After a circular punch is made in the Acomys ear pinna, the tissue surrounding the wound site develops many features that define a regeneration-competent blastema: reepithelialization without scarring, recruitment of mesenchymal cells, and an increase in cell proliferation (45). Given these and other similarities between the blastemas of African spiny mice and those of salamander limbs or mammalian digit tips (98), it is tempting to speculate that ear pinna regeneration may also depend on lineage-restricted progenitors. However, the potency and derivation of Acomys blastema cells are currently unknown and will be important to determine.

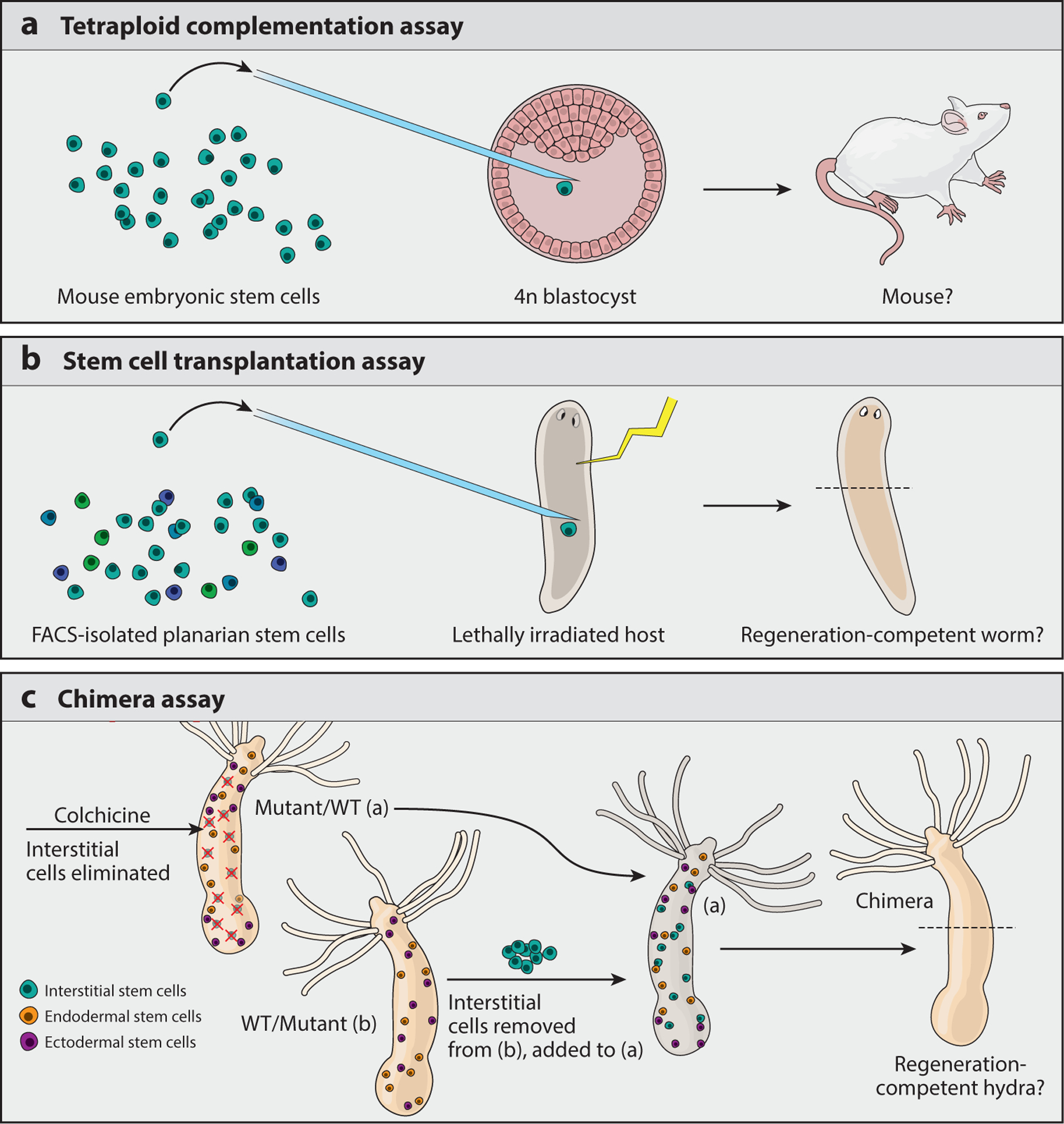

Potency is often defined by molecular markers, particularly with the recent development of powerful methods to assay the chromatin state and gene expression of single cells (22, 128). However, important findings from the embryonic stem cell (ESC) field have demonstrated the significance of establishing potency with functional assays (27, 129). In these studies, ESCs cultured in two different media [two inhibitors/leukemia inhibitory factor (2i/LIF) and serum/LIF] were tested for functional pluripotency in the tetraploid complementation assay (Figure 2a). Briefly, ESCs are injected into a tetraploid embryo, which cannot form a viable fetus on its own (120). Thus, the development of fetal tissue depends on the in vivo pluripotency of the injected cells and the assay serves as a functional test of this potency. Upon injecting ESCs cultured in 2i/LIF versus those cultured in serum/LIF, the former were significantly less successful at creating viable animals (27, 129). This is despite the fact that 2i/LIF media were specifically optimized to enhance the stemness of cultured ESCs (versus standard serum/LIF conditions) and cells cultured in 2i/LIF media have many morphological, molecular, and genomic features that suggest they are more robustly and homogeneously naive (95). For example, ESCs cultured in 2i/LIF express significantly fewer lineage-specific genes (67) and have dramatically lower levels of DNA methylation (114) when compared with ESCs grown in serum/LIF media.

Figure 2.

Functional tests of (pluri)potency. (a) Mammalian tetraploid complementation assay in which 2n cells are injected into a tetraploid (4n) blastocyst and allowed to develop. As the 4n blastocyst cannot form a viable embryo on its own, viable mouse embryos will develop only from 2n cells that are functionally pluripotent. (b) Planarian stem cell transplantation assay in which host worms are depleted of stem cells by a lethal dose of radiation and then injected with stem cells isolated from another worm. As lethally radiated worms will lose their ability to maintain homeostasis and regenerate, only worms rescued by injected pluripotent stem cells will recover these abilities. (c) Hydra chimera assay in which one lineage of Hydra stem cells (the interstitial cells) is ablated by treatment with the drug colchicine, leaving the animal (either a mutant or wild-type strain) with only the endodermal and ectodermal epithelial stem cell lineages. Interstitial cells from a separate animal (of the opposite strain) are then transplanted into the treated hydra; this creates a wild type + mutant chimera and reveals the contribution of a particular mutation to a cell lineage (interstitial or epithelial). Abbreviations: FACS, fluorescence activated cell sorting; WT, wild type.

In addition to uncovering interesting differences in the genomic regulation of these differently cultured cells, these data indicate it is crucial to determine the in vivo functional relevance of all molecular, transcriptomic, or chromatin-based characterizations. Importantly, here we use the term “in vivo” in reference to organismal studies, distinguishing them from experiments done in cell cultures propagated ex vivo. For example, the pluripotency of planarian stem cells was established by injecting a single, adult planarian stem cell into a separate host animal from which all stem cells had been depleted (113) (Figure 2b). Similarly, the potency and functional contribution of specific Hydra stem cells can be determined by a chimera assay (108) (Figure 2c). These experiments establish the functional capacity of a particular cell, beyond its molecular signature, in a functionally relevant environment. As we discuss in the next section, this in vivo environment provides critical signaling information that is translated by specific cell types into changes in genomic output and, ultimately, changes in cellular plasticity.

MOLECULAR MECHANISMS OF IN VIVO POTENCY DURING REGENERATION

Genomic output is regulated at many levels: TFs target specific DNA motifs, various enzymes modify histone proteins in specific ways, chromatin-remodeling complexes alter nucleosome density, and histone chaperones can vary the composition of individual nucleosomes (4). The genome can also be regulated in more dramatic ways, such as the programmed DNA elimination during specific stages of ciliate (130), parasitic nematode (19), and lamprey development (101). Although the precise mechanisms are largely unknown, genome regulation likely plays a major role in many aspects of regeneration, including wound healing, tissue remodeling, and reestablishing polarity. Here, we focus on how various modes of genome regulation influence the potency of cells that give rise to new tissues.

Pioneers of Regeneration

TFs are often considered the drivers of cell fate choice, as they have the ability to discriminate genomic loci by DNA sequence. This sequence-specific recognition allows TFs to activate only those genes required for a particular lineage or potency. However, although sequence specificity is a powerful feature of TFs, their preferred sequence motifs are not always available for binding and subsequent activation. For example, even though there are millions of binding-competent GATA sequence motifs in the human genome, less than 1% of them are bound by this TF at any given time (20). Therefore, limited genome accessibility is an important feature of gene regulation, as it adds a layer of control for cells to prevent misexpression. Yet it also means that unexpected events, such as injury or amputation, must regulate all features controlling genome accessibility to activate the gene networks required to rebuild complex tissue.

A subset of TFs, aptly named pioneer factors (134), have the powerful ability to circumvent such restrictions and initiate significant changes in genomic output. Experiments with the TF myosin D first demonstrated this remarkable power. Weintraub and colleagues showed that exogenous expression of this gene could not only change the transcriptional profile of transfected cells (117, 118) but also drive the conversion of fibroblast cells to myoblasts (31). These breakthrough discoveries then paved the way for another landmark study in which a combination of four specific TFs (Oct4, Sox2, c-Myc, and Klf4) converted fibroblasts to pluripotent stem cells (109). Such iPSCs not only express the expected molecular markers of pluripotency but also pass in vivo functional tests (see Figure 2a).

Pioneer factors are thus ideal candidates to serve as essential regulators of regeneration. In fact, several pioneer factor–encoding genes, including p53 (83, 133), foxA (2), and sox2 (41), are critical for regeneration. A particularly illustrative example of a TF with an essential yet context-dependent role in dedifferentiation is observed during retinal regeneration (40, 54, 86). Upon injury, the zebrafish retina mounts a powerful regenerative response that restores both structure and function (Figure 1). This is achieved, in part, through the dedifferentiation of Müller glia to retinal stem cells (39, 42). By using the powerful genetics tools available for zebrafish, Fausett et al. (40) uncovered that expression of the TF-encoding gene ascl1a is both induced after retinal injury and required for retinal regeneration. Notably, its mammalian homolog (Ascl1) is not upregulated after retinal damage in mice (55), although it is expressed in mouse retinal progenitors and required for the proliferation of neural progenitors during mouse brain development (24). Together, these data strongly support the notion that ascl1 both drives the dedifferentiation of Müller glia upon injury and alters their genomic output in a way that confers regenerative function.

The above findings naturally led researchers working on mammalian retinal models to ask whether exogenous expression of Ascl1 upon injury can induce robust dedifferentiation of mammalian Müller glia and, importantly, neural cell regeneration. They found that overexpression of Ascl1 alone could induce some reprogramming of Müller glia, including the expression of retinal progenitor-specific genes and adoption of neuron-like features (86). However, Ascl1 overexpression could not induce robust regeneration of mature neurons (86). These data are highly reminiscent of the low efficiency seen using overexpression of Yamanaka TFs alone to reprogram differentiated cells into iPSCs; although the original experiment has been validated (77, 122) and these TFs have the potential to drive differentiated cells back to an undifferentiated state, the frequency of such reversion is low. Moreover, all iPSCs are not equally pluripotent when assayed by molecular or functional tests (23, 56, 124).

In spite of their limitations, the Yamanaka TFs and Ascl1 all demonstrate pioneering activity, in that exogenously expressing them induces measurable changes in chromatin accessibility and gene expression (54, 58, 86). However, because such exogenous expression can induce dedifferentiation, but does not do so robustly or efficiently, the genomic context in which these TFs are introduced is critically important. Characterizing these variables and how they affect TF binding to the genome is essential to developing strategies that can induce potency in vivo.

Consider the (Chromatin) Context

Pioneer factors are often necessary but not sufficient for initiating the changes in genomic output that are required for a robust regeneration. This leads us to ask, What are the contextual details that influence a TF’s ability to induce regeneration?

One major variable that affects TF binding and activation is the chromatin state at a given genomic locus (127). The chromatin state is regulated by several different mechanisms, including histone tail modification, DNA methylation, and nucleosome remodeling, all of which affect the accessibility of a given DNA sequence. Again, the exogenous overexpression of Ascl1 in mouse retina serves as an excellent model for understanding how chromatin context plays a highly significant role in mediating TF function during regeneration. As discussed in the section titled Pioneers of Regeneration, overexpressing Ascl1 in the adult mouse retina is not sufficient to induce robust regeneration upon injury (86). However, when Ascl1 is overexpressed in Müller glia and the retinas of these mice are treated with the histone deacetylase inhibitor trichostatin A (TSA), functional neurons regenerate from dedifferentiated Müller glia (54). Moreover, data comparing the chromatin accessibility of these cells with and without TSA treatment show that the maintenance of histone acetylation correlates with the maintenance of accessibility at chromatin-remodeling genes, such as Brd7. Together, these remarkable data suggest that regulation of the chromatin state not only affects the ability of TFs to bind their genomic target sites but also promotes the maintenance of a regeneration-competent state by creating a positive feedback loop with chromatin-remodeling genes. They also suggest that zebrafish retinal cells have intrinsically different chromatin landscapes from those of mouse retinal cells and, further, that uncovering these differences may point to additional targeting strategies.

Despite this significant advance toward inducing retinal regeneration in mammals, many details of this mechanism have yet to be uncovered. Although the combined TF overexpression and histone acetylation maintenance approach does induce the regeneration of functional neurons that respond to light, these damaged mouse retinas are not restored to their original structure or function [as occurs during zebrafish retinal regeneration (54)]. There are many possible reasons for this poor functional outcome, such as the fact that treatment with TSA broadly inhibits deacetylation at many acetylation sites, perhaps including some at which it may have an opposing effect. Although it is useful to know that increased acetylation has a positive effect on functional Müller glia dedifferentiation and differentiation into certain types of neurons, it is still only the first of many important steps toward understanding exactly how the chromatin state must be regulated to achieve complete retinal regeneration.

Histone H3 K4me3: Does form follow function?

The use of a histone deacetylase inhibitor to maintain chromatin accessibility is grounded in a rich literature of studies showing that histone acetylation correlates highly with open chromatin and active transcription (61, 62, 65, 85). The trimethylation of lysine 4 on the histone H3 tail (H3K4me3) is also strongly correlated with active transcription (10, 13, 96, 107). A histone methyltransferase (HMTase) that catalyzes this modification (Mll1) is essential for neuronal differentiation in the postnatal mouse brain (64), hinting at a possible connection between another chromatin-activating mark and retinal regeneration. H3K4me3 also plays a significant role in planarian stem cell biology, as loss of the HMTase Schmidtea mediterranea Set1 (SmedSet1) leads to loss of stem cell function and thus loss of regeneration competence (36, 53).

The planarian model offers considerable benefits in terms of the ability to assess both the functional and the molecular roles of chromatin-modifying enzymes in stem cells. RNA interference (RNAi) effectively perturbs the functional requirements of specific enzymes (78, 89), and the isolation of cells by fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) allows researchers to assay both their function (30, 113, 135) (Figure 2b) and their molecular signature (36, 37, 111, 135). For instance, by isolating stem cells from set1(RNAi) planarians and performing chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by DNA sequencing, Duncan et al. (36) correlated the loss of H3K4me3 at specific genomic loci with the identity and expression of genes at those loci. Importantly, these data revealed SmedSet1 target genes critical for stem cell function and maintenance, including piwi-1, cyclin homologs, and histone genes. Moreover, when these experiments were performed in parallel with stem cells from planarians that had been depleted of a different H3K4me3 HMTase, SmedMLL1/2, it was clear that SmedSet1 targeted a specific set of genomic loci distinct from those targeted by SmedMLL1/2 (36). Notably, the genomic distinction between SmedSet1 and SmedMLL1/2 is reflected in their biological function, as SmedMLL1/2 targets cilia gene loci and smedmll1/2(RNAi) causes a motility phenotype (36, 53). Nevertheless, although it is clear that these two HMTases target different genomic loci with distinct functional consequences, it is still unclear how they achieve this specificity.

The analysis of H3K4me3 signal from planarian stem cells also uncovered some interesting differences in genomic activity between Set1 and MLL1/2. For example, loci targeted by SmedSet1 are marked with fairly wide peaks of H3K4me3 that often cover a large percentage of the gene body; in contrast, loci targeted by SmedMLL1/2 bear peaks of average width that are localized more narrowly to the transcription start site. These differences in peak width clearly correlate with differences in gene expression in planarian stem cells (36). Differences in peak width between gene loci in other organisms correlate with gene expression in those contexts as well (11, 26); however, these studies did not correlate peaks of different average widths with individual H3K4me3 HMTases. Benayoun et al. (11) showed that peak width is, at least in part, regulated by H3K4me3 demethylation in mouse ESCs. However, the mechanism underpinning the regulation of peak width in this context remains unclear. Insight into this problem has been provided by studies of yeast, in which the correlation between H3K4me3 peak width and gene expression has been elegantly dissected and attributed to RNA polymerase II (RNApII) elongation (102). Here, the connection between extended H3K4me3 signal and increased gene expression is clear: Highly transcribed genes correlate with increased RNApII elongation and longer dwell times. Because Set1 associates directly with RNApII, this additional time at a genomic locus provides the H3K4me3 HMTase with an opportunity to methylate more nucleosomes. Therefore, these data not only support a correlation between H3K4me3 peak width and gene expression but also provide mechanistic details about how such variation in H3K4me3 signals may occur.

The yeast data above draw attention to a major question regarding the function of H3K4me3. Although this modification clearly and strongly correlates with gene expression, whether it has a causal role is unclear (52). Soares et al. (102) conclude in fact that high levels of gene expression induce extended H3K4me3 signal rather than the reverse. Yet in many organisms and contexts, including planarian stem cells, loss of H3K4me3 through loss of HMTase activity correlates with loss of gene expression as well (5, 32, 35, 36, 71, 125, 132). Whether such differences are cell type specific, locus specific, or particular to some other contextual variation, together they point to a pleiotropic role for H3K4me3 in vivo.

The functional effects of the planarian HMTase SmedMLL1/2 present an example of one such interesting role for H3K4me3 in vivo. Loci marked by SmedMLL1/2 in planarian stem cells often appear poised for later activation, i.e., upon differentiation, rather than showing strong expression in the stem cells themselves (36). Specifically, SmedMLL1/2 methylates the transcription start site of many conserved cilia genes in stem cells, even though these cells do not robustly express cilia genes or show any signs of cilia structures (7). However, RNAi knockdown of SmedMLL1/2 leads to a highly robust and penetrant cilia-deficient phenotype, suggesting that its targeting of cilia loci in stem cells is meaningful. Although studies aimed at understanding how such poising operates on a mechanistic level are currently ongoing, these data provide evidence that chromatin poising mechanisms exist in planarian stem cells and that they may play a role in creating the appropriate contexts for injury-induced gene activation.

Maintaining a fine balance.

The observation that cilia genes are poised but not robustly expressed in planarian stem cells raises the question: What mechanisms keep such genes silenced until induction by the appropriate signal? One possibility, of course, is that these genes may require a signal-induced TF to bind and activate their expression. However, another possibility is that other chromatin modifications act to silence such loci until the appropriate time. One modification often implicated in such a silencing role is the trimethylation of lysine 27 on histone H3 (H3K27me3) (57, 74). Although it had been known for many years that H3K27me3 correlates with gene silencing, two parallel studies of mouse ESCs (8, 14) were the first to show that this silencing mark can coexist with the H3K4me3 active mark at the same genomic locus. Azuara et al. (8) further showed that loss of H3K27me3 leads to activation of these bivalent genes. As these experiments were done in stem cells and genes important for development, this finding advanced the idea that such combinations of active and silencing chromatin marks can create bivalent switches that poise genes for later activation (or silencing).

The concept of a bivalent switch that can keep genes in a preactivated state for rapid induction in response to external signals is attractive when looking for candidate mechanisms that confer regenerative capacity. Nevertheless, it is unclear whether this particular chromatin switch plays a role in regeneration in vivo. For example, experiments done in planarian stem cells (36) do not show evidence of H3K27me3 enrichment at poised cilia genes, despite trying multiple antibodies with high specificity toward trimethylated H3K27 (versus those that recognize demethylation as well). However, another study of planarian stem cells did observe H3K4me3 + H3K27me3 bivalency at genes that are silent in the stem cells population (29), although it was not shown whether such bivalency is functional (i.e., through knockdown of the planarian H3K27me3 HMTase and subsequent analysis of transcription at these loci). RNAi knockdown of the planarian H3K27me3 HMTase, SmedEzh2, has been done in the context of a screen for conserved genetic regulators and results in a rather weak phenotype (112). However, the latter study was not focused on the role of H3K27me3 and thus did not analyze its loss upon RNAi of the enzyme, so it is possible that the silencing mark was not fully depleted from bivalent genes. It is also possible that there is functional redundancy with other silencing chromatin modifications. In short, additional experiments are needed to fully characterize genomic poising mechanisms in planarian stem cells (and other cells), particularly as they relate to regeneration.

The dynamic regulation of H3K27me3 in zebrafish fin regeneration, in which an enzyme with H3K27me3-demethylating activity is required for proper regeneration, has also been studied. Here, Stewart et al. (106) uncovered evidence of decreased gene expression upon loss of the H3K27me3 demethylase Kdm6b.1, as expected, although they do not show that such changes in expression correlate with increased H3K27me3 at those specific genomic loci. The kdm6b.1 gene is both strongly expressed in the blastema of regenerating fins and strongly upregulated after amputation (106). Understanding the mechanism by which increased H3K27me3 affects regeneration is also complicated because there are several Kdm6 homologs in zebrafish, indicating possible functional redundancy. Nevertheless, although the exact cellular localization and genomic targeting of Kdm6b.1 are unclear, these data combined with unpublished experimental evidence (S. Stewart, personal communication) support the hypothesis that H3K27me3 plays a functional role in zebrafish fin regeneration.

Broader Impact of Chromatin Organization on Regeneration

The dynamic regulation of histone modifications is an important mechanism through which cells can modulate chromatin contexts that affect TF binding. Histone acetylation affects genome accessibility, at least in part, by changing the charge of histone proteins and their direct interactions with DNA. Because histone methylation is a charge-neutral addition to the genome (93), this modification instead functions indirectly by serving as a new binding site for other proteins, e.g., chromatin-remodeling complexes (99, 126). Recruited complexes can then alter genome accessibility themselves, through nucleosome remodeling or long-range interactions with other regions of the genome, depending on their intrinsic activity and binding properties (28).

The above examples of in vivo genome regulation in stem cells and regenerative models reveal how specific mechanisms can broadly impact overall chromatin organization. First, treatment of the mouse retina with the histone deacetylase inhibitor TSA not only increased acetylation levels and chromatin accessibility directly but also led to the increased transcription of chromatin-remodeling genes (54). In this way, the alteration of one histone modification led to a positive feedback loop that can maintain open chromatin. Second, differences in H3K4me3 peak width correlate with functional differences in genomic output (11, 26, 36, 102). A mechanism for creating extended H3K4me3 signal in yeast (102) and to some extent in mammalian cells (11) has been detailed; yet questions remain regarding the downstream function of H3K4me3 signal differences in vivo. Unpublished data from E.M. Duncan and A. Sánchez Alvarado on planarian stem cells suggest that increased H3K4me3 leads to increased chromatin accessibility at those loci, an effect that is likely mediated by the recruitment of the nucleosome remodeling factor (NuRF) complex. Together, these data also suggest that the modification of a single lysine in the H3 tail can create a robust, positive feedback loop that maintains genomic accessibility at important gene loci.

Whereas the above examples, as well as many others from ex vivo cell culture (95), reveal how individual modifications on the chromatin template can have larger impacts on overall chromatin organization, it is considerably more difficult to address the functional question that arises from these findings: Do changes to overall chromatin organization have specific functional effects in vivo? Additionally, and specific to the questions discussed in this review, do such changes impact regenerative ability?

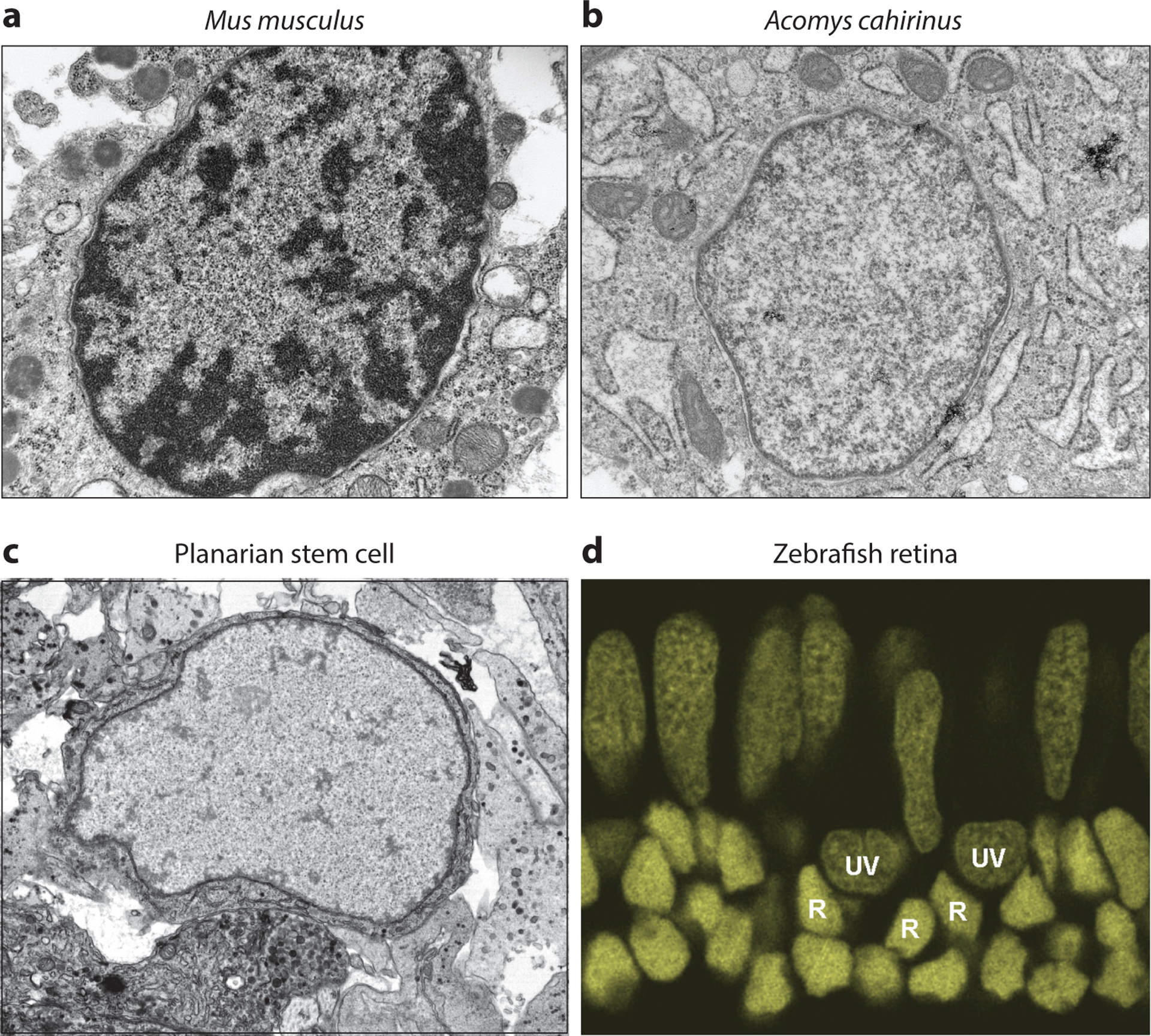

Although many experiments must be done to test these questions, some observational data collected from animal models of regeneration may inform such experiments. First, electron microscopy data comparing cells in the injured ears of regeneration-competent African spiny mice with those from nonregenerative M. musculus show obvious differences in chromatin compaction; whereas the nuclei of M. musculus contain significant regions of darkly stained heterochromatin, those of Acomys cahirinus appear entirely euchromatic (45). This is highly reminiscent of the appearance of euchromatic nuclei in both mammalian ESCs (110) and planarian in vivo stem cells (80) (Figure 3). Second, the staining of zebrafish retinas with DNA dye also reveals that the nuclei of different retinal neurons have markedly different chromatin compaction (A. Morris, personal communication) (Figure 3). Given that the zebrafish retina has robust regenerative abilities and that rods and cones regenerate from different progenitor pools, such intriguing differences will be interesting to dissect in future studies.

Figure 3.

Chromatin compaction and cellular plasticity. (a) Transmission electron micrograph of fibroblast cells in the surrounding tissue of a Mus musculus ear hole, 15 days postinjury. Image provided by and published with permission from A. Seifert. (b) Transmission electron micrograph of fibroblast cells in the surrounding tissue of an Acomys cahirinus ear hole, 15 days postinjury. Image provided by and published with permission from A. Seifert. (c) Transmission electron micrograph of a planarian neoblast cell. Image provided by and published with permission from A. Sánchez Alvarado. (d) A zebrafish retinal section stained with DAPI nuclear dye. The chromatin compaction of rod nuclei (R) appears significantly more compact and darkly stained than that of either UV cone nuclei (UV) or blue/red/green cone nuclei (elongated nuclei in top layer). Image provided by and published with permission from A. Morris. Abbreviation: DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

LOOKING FORWARD

In many ways, T.H.Morgan’s choice to abandon planarian research and pursue the study of genetic heritability in a more accessible organism (Drosophila melanogaster) is understandable; what makes regeneration so fascinating also makes it exceedingly hard to untangle—it upends our normal expectations. However, with the development of so many powerful tools in recent decades, we now have the ability to address many questions that T.H. Morgan could not.

In this review we attempted to highlight two key themes essential for uncovering functional mechanisms that regulate genomic output and in vivo regeneration: First, it is important to use in vivo functional tests of (pluri)potency. Although the development of methods to maintain ESCs in culture ex vivo is an enormous advance and allows the development of powerful conceptual hypotheses (more below), experimental findings have taught us that molecular evidence does not substitute for in vivo functional results (27, 129). Moreover, in vivo functional tests and experiments in organismal models of regeneration are likely to uncover findings that are more immediately biologically relevant.

Second, we want to emphasize the importance of detailed mechanistic inquiry in organismal models. Here, in contrast, we can lean heavily on ex vivo–cultured models to develop testable hypotheses of important conceptual advances. For example, the chromatin field has recently moved toward understanding the function of histone modifications themselves separate from the enzymes that catalyze them. Studies of ESCs (34) and D. melanogaster (91) use both catalytically inactivated MLL3 and MLL4 to show that monomethylation of H3K4 at enhancers does not significantly affect downstream gene expression. In each case, MLL3 and MLL4 enzymes can form normal complexes and bind their target enhancer loci; they simply cannot modify histone tails. In contrast, loss of these enzymes leads to downregulation of target genes, suggesting that the important function of these proteins is to create interactions between their target enhancers and other regions of the genome (e.g., promoters). Although such detailed mechanistic studies are much less tractable in organisms in which the same genetic tools cannot yet be used, their findings represent an important conceptual advance that, once uncovered, may be tested in different contexts and by different methods.

Across the animal kingdom, animals use multiple strategies and molecular mechanisms to achieve (pluri)potency and regeneration competence. Understanding the breadth of these strategies is crucial for developing clinical methods that recapitulate regeneration in noncompetent tissues. It may also help us answer more expansive questions: Are there common regulatory mechanisms that render an organism or tissue capable of regeneration? Are these mechanisms rooted in genomic differences, differences in genome regulatory mechanisms, or both? We look forward to making new discoveries that help answer these questions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Mark M. Miller for the beautiful illustrations he created for Figures 1 and 2. E.M.D. would also like to thank A. Morris and A. Seifert for thoughtful discussions and helpful input. A.S.A. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the Stowers Institute for Medical Research. A.S.A. is grateful to the National Institutes of General Medicine for funding part of the research reported here (NIH R37GM057260).

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors are not aware of any affiliations, memberships, funding, or financial holdings that might be perceived as affecting the objectivity of this review.

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.Adler CE,Sánchez Alvarado A. 2017. PHRED-1 is a divergent neurexin-1 homolog that organizes muscle fibers and patterns organs during regeneration. Dev. Biol 427:165–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adler CE, Seidel CW, McKinney SA, Sánchez Alvarado A. 2014. Selective amputation of the pharynx identifies a FoxA-dependent regeneration program in planaria. eLife 3:e02238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alibardi L 2010. Morphological and cellular aspects of tail and limb regeneration in lizards. A model system with implications for tissue regeneration in mammals. Adv. Anat. Embryol. Cell Biol 207:1–109 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allis CD, Caparros M-L, Jenuwein T, Reinberg D. 2015. Epigenetics. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. 2nd ed. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ardehali MB, Mei A, Zobeck KL, Caron M, Lis JT, Kusch T. 2011. Drosophila Set1 is the major histone H3 lysine 4 trimethyltransferase with role in transcription. EMBO J. 30:2817–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aristotle. 1878. Aristotle’s History of Animals. In Ten Books, transl. Cresswell R. London: G. Bell [Google Scholar]

- 7.Azimzadeh J, Wong ML, Downhour DM, Sánchez Alvarado A, Marshall WF. 2012. Centrosome loss in the evolution of planarians. Science 335:461–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Azuara V, Perry P, Sauer S, Spivakov M, Jørgensen HF, et al. 2006. Chromatin signatures of pluripotent cell lines. Nat. Cell Biol 8:532–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baguñà J 2012. The planarian neoblast: the rambling history of its origin and some current black boxes. Int. J. Dev. Biol 56:19–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barski A, Cuddapah S, Cui K, Roh T-Y, Schones DE, et al. 2007. High-resolution profiling of histone methylations in the human genome. Cell 129:823–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benayoun BA, Pollina EA, Ucar D, Mahmoudi S, Karra K, et al. 2015. H3K4me3 breadth is linked to cell identity and transcriptional consistency. Cell 163:1281–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernardos RL,Barthel LK,Meyers JR,Raymond PA. 2007. Late-stage neuronal progenitors in the retina are radial Müller glia that function as retinal stem cells. J. Neurosci 27:7028–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernstein BE, Humphrey EL, Erlich RL, Schneider R, Bouman P, et al. 2002. Methylation of histone H3 Lys 4 in coding regions of active genes. PNAS 99:8695–700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bernstein BE, Mikkelsen TS, Xie X, Kamal M, Huebert DJ, et al. 2006. A bivalent chromatin structure marks key developmental genes in embryonic stem cells. Cell 125:315–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berrill NJ. 1983. The pleasure and practice of biology. Can. J. Zool 61:947–51 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Birnbaum KD, Sánchez Alvarado A. 2008. Slicing across kingdoms: regeneration in plants and animals. Cell 132:697–710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bonnet C 1777. Expériences sur la régénération de la Téte du Limaçon terrestre. J. Physique 10(Part II):165–79 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bosch TCG. 2009. Hydra and the evolution of stem cells. Bioessays 31:478–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bovari T 1887. Über Differenzierung der Zellkerne wahrend der Furchung des Eies von Ascaris megalocephala. Anat. Anz 2:688–93 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bresnick EH, Katsumura KR, Lee HY, Johnson KD, Perkins AS. 2012. Master regulatory GATA transcription factors: mechanistic principles and emerging links to hematologic malignancies. Nucleic Acids Res. 40:5819–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brockes JP, Kumar A. 2008. Comparative aspects of animal regeneration. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol 24:525–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buenrostro JD, Wu B, Litzenburger UM, Ruff D, Gonzales ML, et al. 2015. Single-cell chromatin accessibility reveals principles of regulatory variation. Nature 523:486–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buganim Y, Markoulaki S, van Wietmarschen N, Hoke H, Wu T, et al. 2014. The developmental potential of iPSCs is greatly influenced by reprogramming factor selection. Cell Stem Cell 15:295–309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Castro DS, Martynoga B, Parras C, Ramesh V, Pacary E, et al. 2011. A novel function of the proneural factor Ascl1 in progenitor proliferation identified by genome-wide characterization of its targets. Genes Dev. 25:930–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen CH, Poss KD. 2017. Regeneration genetics. Annu. Rev. Genet 51:63–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen K, Chen Z, Wu D, Zhang L, Lin X, et al. 2015. Broad H3K4me3 is associated with increased transcription elongation and enhancer activity at tumor-suppressor genes. Nat. Genet 47:1149–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choi J,Huebner AJ,Clement K,Walsh RM,Savol A,et al. 2017. Prolonged Mek1/2 suppression impairs the developmental potential of embryonic stem cells. Nature 548:219–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clapier CR, Cairns BR. 2009. The biology of chromatin remodeling complexes. Annu. Rev. Biochem 78:273–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dattani A, Kao D, Mihaylova Y, Abnave P, Hughes S, et al. 2018. Epigenetic analyses of planarian stem cells demonstrate conservation of bivalent histone modifications in animal stem cells. Genome Res. 28:1543–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davies EL, Lei K, Seidel CW, Kroesen AE, McKinney SA, et al. 2017. Embryonic origin of adult stem cells required for tissue homeostasis and regeneration. eLife 6:e21052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davis RL, Weintraub H, Lassar AB. 1987. Expression of a single transfected cDNA converts fibroblasts to myoblasts. Cell 51:987–1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Denissov S, Hofemeister H, Marks H, Kranz A, Ciotta G, et al. 2014. Mll2 is required for H3K4 trimethylation on bivalent promoters in embryonic stem cells, whereas Mll1 is redundant. Development 141:526–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dolan CP, Dawson LA, Muneoka K. 2018. Digit tip regeneration: merging regeneration biology with regenerative medicine. Stem Cells Transl. Med 7:262–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dorighi KM, Swigut T, Henriques T, Bhanu NV, Scruggs BS, et al. 2017. Mll3 and Mll4 facilitate enhancer RNA synthesis and transcription from promoters independently of H3K4 monomethylation. Mol. Cell 66:568–76.e4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dou Y, Milne TA, Ruthenburg AJ, Lee S, Lee JW, et al. 2006. Regulation of MLL1 H3K4 methyltransferase activity by its core components. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 13:713–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Duncan EM, Chitsazan AD, Seidel CW, Sánchez Alvarado A. 2015. Set1 and MLL1/2 target distinct sets of functionally different genomic loci in vivo. Cell Rep. 13:2741–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eisenhoffer GT, Kang H, Sánchez Alvarado A. 2008. Molecular analysis of stem cells and their descendants during cell turnover and regeneration in the planarian Schmidtea mediterranea. Cell Stem Cell 3:327–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elliott SA, Sánchez Alvarado A. 2013. The history and enduring contributions of planarians to the study of animal regeneration. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Dev. Biol 2:301–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fausett BV, Goldman D. 2006. A role for α1 tubulin-expressing Müller glia in regeneration of the injured zebrafish retina. J. Neurosci 26:6303–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fausett BV, Gumerson JD, Goldman D. 2008. The proneural basic helix-loop-helix gene ascl1a is required for retina regeneration. J. Neurosci 28:1109–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fei JF, Schuez M, Tazaki A, Taniguchi Y, Roensch K, Tanaka EM. 2014. CRISPR-mediated genomic deletion of Sox2 in the axolotl shows a requirement in spinal cord neural stem cell amplification during tail regeneration. Stem. Cell Rep 3:444–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fimbel SM, Montgomery JE, Burket CT, Hyde DR. 2007. Regeneration of inner retinal neurons after intravitreal injection of ouabain in zebrafish. J. Neurosci 27:1712–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fincher CT, Wurtzel O, de Hoog T, Kravarik KM, Reddien PW. 2018. Cell type transcriptome atlas for the planarian Schmidtea mediterranea. Science 360:eaaq1736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fujisawa T 2003. Hydra regeneration and epitheliopeptides. Dev. Dyn 226:182–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gawriluk TR, Simkin J, Thompson KL, Biswas SK, Clare-Salzler Z, et al. 2016. Comparative analysis of ear-hole closure identifies epimorphic regeneration as a discrete trait in mammals. Nat. Commun 7:11164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gemberling M, Bailey TJ, Hyde DR, Poss KD. 2013. The zebrafish as a model for complex tissue regeneration. Trends Genet. 29:611–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goldman D 2014. Müller glial cell reprogramming and retina regeneration. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 15:431–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goss RJ, Powel RS. 1985. Induction of deer antlers by transplanted periosteum. I. Graft size and shape. J. Exp. Zool 235:359–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guo T, Peters AHFM, Newmark PA. 2006. A bruno-like gene is required for stem cell maintenance in planarians. Dev. Cell 11:159–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hemmrich G, Khalturin K, Boehm AM, Puchert M, Anton-Erxleben F, et al. 2012. Molecular signatures of the three stem cell lineages in Hydra and the emergence of stem cell function at the base of multicellularity. Mol. Biol. Evol 29:3267–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Histoire de l’Académie Royale des Sciences depuis 1686 jusqu’ à son renouvellement en 1699. 1733. Paris: Bibliothéque De M. J.-A. Barral [Google Scholar]

- 52.Howe FS, Fischl H, Murray SC, Mellor J. 2017. Is H3K4me3 instructive for transcription activation? Bioessays 39:1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hubert A, Henderson JM, Ross KG, Cowles MW, Torres J, Zayas RM. 2013. Epigenetic regulation of planarian stem cells by the SET1/MLL family of histone methyltransferases. Epigenetics 8:79–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jorstad NL, Wilken MS, Grimes WN, Wohl SG,VandenBosch LS, et al. 2017. Stimulation of functional neuronal regeneration from Müller glia in adult mice. Nature 548:103–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Karl MO, Hayes S, Nelson BR, Tan K, Buckingham B, Reh TA. 2008. Stimulation of neural regeneration in the mouse retina. PNAS 105:19508–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim K, Doi A, Wen B, Ng K, Zhao R, et al. 2010. Epigenetic memory in induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature 467:285–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kirmizis A, Bartley SM, Kuzmichev A, Margueron R, Reinberg D, et al. 2004. Silencing of human polycomb target genes is associated with methylation of histone H3 Lys 27. Genes Dev. 18:1592–605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Knaupp AS, Buckberry S, Pflueger J, Lim SM, Ford E, et al. 2017. Transient and permanent reconfiguration of chromatin and transcription factor occupancy drive reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell 21:834–45.e6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Knopf F, Hammond C, Chekuru A, Kurth T, Hans S, et al. 2011. Bone regenerates via dedifferentiation of osteoblasts in the zebrafish fin. Dev. Cell 20:713–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kragl M, Knapp D, Nacu E, Khattak S, Maden M, et al. 2009. Cells keep a memory of their tissue origin during axolotl limb regeneration. Nature 460:60–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kurdistani SK, Tavazoie S, Grunstein M. 2004. Mapping global histone acetylation patterns to gene expression. Cell 117:721–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee DY, Hayes JJ, Pruss D, Wolffe AP. 1993. A positive role for histone acetylation in transcription factor access to nucleosomal DNA. Cell 72:73–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lenhoff SG, Lenhoff HM, Trembley A. 1986. Hydra and the Birth of Experimental Biology—1744. Abraham Trembley’s Mémoires Concerning the Polyps. Pacific Grove, CA: Boxwood Press [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lim DA, Huang Y-C, Swigut T, Mirick AL, Garcia-Verdugo JM, et al. 2009. Chromatin remodeling factor Mll1 is essential for neurogenesis from postnatal neural stem cells. Nature 458:529–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lin R,Leone JW,Cook RG,Allis CD. 1989. Antibodies specific to acetylated histones document the existence of deposition- and transcription-related histone acetylation in Tetrahymena. J. Cell Biol 108:1577–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Manco R,Leclercq IA,Clerbaux L-A. 2018. Liver regeneration: Different sub-populations of parenchymal cells at play choreographed by an injury-specific microenvironment. Int. J. Mol. Sci 19:E4115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Marks H, Kalkan T, Menafra R, Denissov S, Jones K, et al. 2012. The transcriptional and epigenomic foundations of ground state pluripotency. Cell 149:590–604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Martello G, Smith A. 2014. The nature of embryonic stem cells. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol 30:647–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Martínez DE. 1998. Mortality patterns suggest lack of senescence in Hydra. Exp. Gerontol 33:217–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.McCusker CD, Athippozhy A, Diaz-Castillo C, Fowlkes C, Gardiner DM, Voss SR. 2015. Positional plasticity in regenerating Ambystoma mexicanum limbs is associated with cell proliferation and pathways of cellular differentiation. BMC Dev. Biol 15:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Milne TA, Briggs SD, Brock HW, Martin ME, Gibbs D, et al. 2002. MLL targets SET domain methyltransferase activity to Hox gene promoters. Mol. Cell 10:1107–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Morris AC, Scholz TL, Brockerhoff SE, Fadool JM. 2008. Genetic dissection reveals two separate pathways for rod and cone regeneration in the teleost retina. Dev. Neurobiol 68:605–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Morrison SJ, Uchida N, Weissman IL. 1995. The biology of hematopoietic stem cells. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol 11:35–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Müller J, Hart CM, Francis NJ, Vargas ML, Sengupta A, et al. 2002. Histone methyltransferase activity of a Drosophila Polycomb group repressor complex. Cell 111:197–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Murawala P,Tanaka EM,Currie JD. 2012. Regeneration: the ultimate example of wound healing. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol 23:954–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nacu E,Tanaka EM. 2011. Limb regeneration: a new development? Annu.Rev.Cell Dev.Biol 27:409–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nakagawa M, Koyanagi M, Tanabe K, Takahashi K, Ichisaka T, et al. 2008. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells without Myc from mouse and human fibroblasts. Nat. Biotechnol 26:101–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Newmark PA, Reddien PW, Cebrià F, Sánchez Alvarado A. 2003. Ingestion of bacterially expressed double-stranded RNA inhibits gene expression in planarians. PNAS 100(Suppl. 1):11861–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Newmark PA, Sánchez Alvarado A. 2000. Bromodeoxyuridine specifically labels the regenerative stem cells of planarians. Dev. Biol 220:142–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Newmark PA, Sánchez Alvarado A. 2002. Not your father’s planarian: a classic model enters the era of functional genomics. Nat. Rev. Genet 3:210–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pallas PS. 1767. Spicilegia zoologica: quibus novae imprimis et obscurae animalium species iconibus. Pre-1801 Imprint Collection, Library of Congress, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 82.Papayannopoulou T, Scadden DT. 2008. Stem-cell ecology and stem cells in motion. Blood 111:3923–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pearson BJ, Sánchez Alvarado A. 2010. A planarian p53 homolog regulates proliferation and self-renewal in adult stem cell lineages. Development 137:213–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Plass M, Solana J, Wolf FA, Ayoub S, Misios A, et al. 2018. Cell type atlas and lineage tree of a whole complex animal by single-cell transcriptomics. Science 360:eaaq1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pogo BG, Pogo AO, Allfrey VG, Mirsky AE. 1968. Changing patterns of histone acetylation and RNA synthesis in regeneration of the liver. PNAS 59:1337–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pollak J, Wilken MS, Ueki Y, Cox KE, Sullivan JM, et al. 2013. ASCL1 reprograms mouse Müller glia into neurogenic retinal progenitors. Development 140:2619–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ramalho-Santos M, Willenbring H. 2007. On the origin of the term “stem cell.” Cell Stem Cell 1:35–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Raymond PA,Barthel LK,Bernardos RL,Perkowski JJ. 2006. Molecular characterization of retinal stem cells and their niches in adult zebrafish. BMC Dev. Biol 6:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Reddien PW, Bermange AL, Murfitt KJ, Jennings JR, Sánchez Alvarado A. 2005. Identification of genes needed for regeneration, stem cell function, and tissue homeostasis by systematic gene perturbation in planaria. Dev. Cell 8:635–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Reddien PW, Oviedo NJ, Jennings JR, Jenkin JC, Sánchez Alvarado A. 2005. SMEDWI-2 is a PIWI-like protein that regulates planarian stem cells. Science 310:1327–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Rickels R, Herz HM, Sze CC, Cao K, Morgan MA, et al. 2017. Histone H3K4 monomethylation catalyzed by Trr and mammalian COMPASS-like proteins at enhancers is dispensable for development and viability. Nat. Genet 49:1647–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Rossant J 2018. Genetic control of early cell lineages in the mammalian embryo. Annu. Rev. Genet 52:185–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ruthenburg AJ, Allis CD, Wysocka J. 2007. Methylation of lysine 4 on histone H3: intricacy of writing and reading a single epigenetic mark. Mol. Cell 25:15–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sánchez Alvarado A, Yamanaka S. 2014. Rethinking differentiation: stem cells, regeneration, and plasticity. Cell 157:110–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Schlesinger S, Meshorer E. 2019. Open chromatin, epigenetic plasticity, and nuclear organization in pluripotency. Dev. Cell 48:135–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Schneider R, Bannister AJ, Myers FA, Thorne AW, Crane-Robinson C, Kouzarides T. 2004. Histone H3 lysine 4 methylation patterns in higher eukaryotic genes. Nat. Cell Biol 6:73–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Seifert AW, Kiama SG, Seifert MG, Goheen JR, Palmer TM, Maden M. 2012. Skin shedding and tissue regeneration in African spiny mice (Acomys). Nature 489:561–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Seifert AW, Muneoka K. 2018. The blastema and epimorphic regeneration in mammals. Dev. Biol 433:190–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Shi X, Hong T, Walter KL, Ewalt M, Michishita E, et al. 2006. ING2 PHD domain links histone H3 lysine 4 methylation to active gene repression. Nature 442:96–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Singh SP, Holdway JE, Poss KD. 2012. Regeneration of amputated zebrafish fin rays from de novo osteoblasts. Dev. Cell 22:879–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Smith JJ, Antonacci F, Eichler EE, Amemiya CT. 2009. Programmed loss of millions of base pairs from a vertebrate genome. PNAS 106:11212–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Soares LM, He PC, Chun Y, Suh H, Kim T, Buratowski S. 2017. Determinants of histone H3K4 methylation patterns. Mol. Cell 68:773–85.e6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Soldner F, Jaenisch R. 2018. Stem cells, genome editing, and the path to translational medicine. Cell 175:615–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Spallanzani L 1768. Prodromo di un’ opera da imprimersi sopra le riproduzioni animali dato in luce dall’ abate spallanzani. Modena, Italy: Nella Stamperia di Giovanni Montanari [Google Scholar]

- 105.Stewart S, Stankunas K. 2012. Limited dedifferentiation provides replacement tissue during zebrafish fin regeneration. Dev. Biol 365:339–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Stewart S, Tsun Z-Y, Izpisua Belmonte JC. 2009. A histone demethylase is necessary for regeneration in zebrafish. PNAS 106:19889–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Strahl BD,Ohba R,Cook RG,Allis CD. 1999. Methylation of histone H3 at lysine 4 is highly conserved and correlates with transcriptionally active nuclei in Tetrahymena. PNAS 96:14967–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Sugiyama T, Wanek N. 1993. Genetic analysis of developmental mechanisms in Hydra: XXI. Enhancement of regeneration in a regeneration-deficient mutant strain by the elimination of the interstitial cell lineage. Dev. Biol 160:64–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. 2006. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell 126:663–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Underwood JM, Becker KA, Stein GS, Nickerson JA. 2017. The ultrastructural signature of human embryonic stem cells. J. Cell Biochem 118:764–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.van Wolfswinkel JC, Wagner DE, Reddien PW. 2014. Single-cell analysis reveals functionally distinct classes within the planarian stem cell compartment. Cell Stem Cell 15:326–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Wagner DE, Ho JJ, Reddien PW. 2012. Genetic regulators of a pluripotent adult stem cell system in planarians identified by RNAi and clonal analysis. Cell Stem Cell 10:299–311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Wagner DE, Wang IE, Reddien PW. 2011. Clonogenic neoblasts are pluripotent adult stem cells that underlie planarian regeneration. Science 332:811–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Walter M, Teissandier A, Pérez-Palacios R, Bourc’his D. 2016. An epigenetic switch ensures transposon repression upon dynamic loss of DNA methylation in embryonic stem cells. eLife 5:e11418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Wan J, Goldman D. 2016. Retina regeneration in zebrafish. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev 40:41–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Watanabe H,Hoang VT,Mattner R,Holstein TW. 2009. Immortality and the base of multicellular life: lessons from cnidarian stem cells. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol 20:1114–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Weintraub H, Dwarki VJ, Verma I, Davis R, Hollenberg S, et al. 1991. Muscle-specific transcriptional activation by MyoD. Genes Dev. 5:1377–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Weintraub H, Tapscott SJ, Davis RL, Thayer MJ, Adam MA, et al. 1989. Activation of muscle-specific genes in pigment, nerve, fat, liver, and fibroblast cell lines by forced expression of MyoD. PNAS 86:5434–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Weismann A 1893. The Germ-Plasm. A Theory of Heredity, transl Parker WN, Rönnfeldt H. New York: Scribner’s [Google Scholar]

- 120.Wen D, Saiz N, Rosenwaks Z, Hadjantonakis AK, Rafii S. 2014. Completely ES cell-derived mice produced by tetraploid complementation using inner cell mass (ICM) deficient blastocysts. PLOS ONE 9:e94730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Wenemoser D, Reddien PW. 2010. Planarian regeneration involves distinct stem cell responses to wounds and tissue absence. Dev. Biol 344:979–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Wernig M, Meissner A, Foreman R, Brambrink T, Ku M, et al. 2007. In vitro reprogramming of fibroblasts into a pluripotent ES-cell-like state. Nature 448:318–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Wittlieb J, Khalturin K, Lohmann JU, Anton-Erxleben F, Bosch TCG. 2006. Transgenic Hydra allow in vivo tracking of individual stem cells during morphogenesis. PNAS 103:6208–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Wu T, Liu Y, Wen D, Tseng Z, Tahmasian M, et al. 2014. Histone variant H2A.X deposition pattern serves as a functional epigenetic mark for distinguishing the developmental potentials of iPSCs. Cell Stem Cell 15:281–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Wysocka J,Swigut T,Milne TA,Dou Y,Zhang X, et al. 2005. WDR5 associates with histone H3 methylated at K4 and is essential for H3 K4 methylation and vertebrate development. Cell 121:859–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Wysocka J,Swigut T,Xiao H,Milne TA,Kwon SY,et al. 2006. A PHD finger of NURF couples histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation with chromatin remodelling. Nature 442:86–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Xu CR, Cole PA, Meyers DJ, Kormish J, Dent S, Zaret KS. 2011. Chromatin “prepattern” and histone modifiers in a fate choice for liver and pancreas. Science 332:963–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Xue Z, Huang K, Cai C, Cai L, Jiang CY, et al. 2013. Genetic programs in human and mouse early embryos revealed by single-cell RNA sequencing. Nature 500:593–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Yagi M, Kishigami S, Tanaka A, Semi K, Mizutani E, et al. 2017. Derivation of ground-state female ES cells maintaining gamete-derived DNA methylation. Nature 548:224–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Yokoyama RW, Yao MC. 1982. Elimination of DNA sequences during macronuclear differentiation in Tetrahymena thermophila, as detected by in situ hybridization. Chromosoma 85:11–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Yoshida-Kashikawa M, Shibata N, Takechi K, Agata K. 2007. DjCBC-1, a conserved DEAD box RNA helicase of the RCK/p54/Me31B family, is a component of RNA-protein complexes in planarian stem cells and neurons. Dev. Dyn 236:3436–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Yu BD, Hanson RD, Hess JL, Horning SE, Korsmeyer SJ. 1998. MLL, a mammalian trithorax-group gene, functions as a transcriptional maintenance factor in morphogenesis. PNAS 95:10632–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Yun MH, Gates PB, Brockes JP. 2013. Regulation of p53 is critical for vertebrate limb regeneration. PNAS 110:17392–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Zaret KS, Mango SE. 2016. Pioneer transcription factors, chromatin dynamics, and cell fate control. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev 37:76–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Zeng A, Li H, Guo L, Gao X, McKinney S, et al. 2018. Prospectively isolated tetraspanin+ neoblasts are adult pluripotent stem cells underlying planaria regeneration. Cell 173:1593–608.e20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]