Abstract

Lyme borreliosis (LB) is the most common vector‐borne disease in the Northern Hemisphere caused by spirochetes belonging to the Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato (Bbsl) complex. Borrelia spirochetes circulate in obligatory transmission cycles between tick vectors and different vertebrate hosts. To successfully complete this complex transmission cycle, Bbsl encodes for an arsenal of proteins including the PFam54 protein family with known, or proposed, influences to reservoir host and/or vector adaptation. Even so, only fragmentary information is available regarding the naturally occurring level of variation in the PFam54 gene array especially in relation to Eurasian‐distributed species. Utilizing whole genome data from isolates (n = 141) originated from three major LB‐causing Borrelia species across Eurasia (B. afzelii, B. bavariensis, and B. garinii), we aimed to characterize the diversity of the PFam54 gene array in these isolates to facilitate understanding the evolution of PFam54 paralogs on an intra‐ and interspecies level. We found an extraordinarily high level of variation in the PFam54 gene array with 39 PFam54 paralogs belonging to 23 orthologous groups including five novel paralogs. Even so, the gene array appears to have remained fairly stable over the evolutionary history of the studied Borrelia species. Interestingly, genes outside Clade IV, which contains genes encoding for proteins associated with Borrelia pathogenesis, more frequently displayed signatures of diversifying selection between clades that differ in hypothesized vector or host species. This could suggest that non‐Clade IV paralogs play a more important role in host and/or vector adaptation than previously expected, which would require future lab‐based studies to validate.

Keywords: Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato, gene evolution, host‐pathogen interactions, Lyme borreliosis, PFam54 gene array, spirochetes

Utilizing whole genome sequencing data for 141 Eurasian distributed Borrelia isolates, we show that the PFam54 gene array is highly variable among and within Borrelia species, including the absence of genes of known function during infection. Further analysis highlighted though that understudied paralogs most likely are important to completing the Borrelia life cycle, although with a yet unknown function, requiring further research. Taken together, the results display the importance of studying individual variation in Borrelia species from a population genetics perspective to provide novel hypotheses regarding Borrelia or vector‐borne pathogen evolution.

1. INTRODUCTION

Lyme borreliosis (LB) is the most common vector‐borne disease in the Northern Hemisphere (Stanek et al., 2011; Steere et al., 2016). This disease is caused by spirochetes belonging to the Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato (Bbsl) species complex and are maintained naturally in complex enzootic transmission cycles between ixodid ticks and various vertebrate hosts (Kurtenbach et al., 2006; Stanek et al., 2011). Borrelia possess a range of proteins encoded by genes located on a fragmented genome allowing spirochetes to interact with different environmental conditions in tick vectors and vertebrate hosts. The borrelial genome consists of a highly conserved, linear chromosome and up to 20 circular and linear plasmids (Fraser et al., 1997; Kraiczy, 2016; Schwartz et al., 2021). Although much research has gone into understanding the pathogenic processes in humans, many open questions remain regarding the impact of naturally occurring genetic variation in LB spirochetes on underlying molecular infection mechanisms especially in relation to natural transmission cycles.

To establish an infection, Bbsl must evade host immune responses including complement as an important pillar of innate immunity. This may be either indirectly through the acquisition of complement regulators or directly through interactions with different complement components (Coburn et al., 2021; Dulipati et al., 2020; Kraiczy & Stevenson, 2013; Lin, Diuk‐Wasser, et al., 2020; Lin, Frye, et al., 2020; Skare & Garcia, 2020). The complement system consists of three distinct pathways (classical, lectin, and alternative) which all converge to the cleavage of the central component C3 to form activated C3b (Atkinson et al., 2019). Host cells control excessive complement damage by utilizing membrane‐bound or fluid‐phase regulator proteins (Atkinson et al., 2019) which can terminate the complement cascade at different activation levels to protect self‐cells from damage (Atkinson et al., 2019). Lyme borreliosis spirochetes produce diverse outer surface proteins that bind distinct host complement components resulting in complement inactivation (Caine et al., 2017; Coburn et al., 2021; Garcia et al., 2016; Kraiczy, 2016; Skare & Garcia, 2020; Xie et al., 2019). One well‐studied protein belonging to the paralogous protein family PFam54 Clade IV, CspA (bba68), is capable of binding the fluid‐phase complement regulatory proteins Factor H and Factor H‐like protein 1 (FHL‐1) (Hart et al., 2018; Kraiczy, 2016). Members of the PFam54 are encoded by genes predominantly arranged in a multi‐gene array located at the 5´‐terminal end of the linear plasmid 54 (lp54) in the majority of Bbsl isolates studied (Casjens et al., 2012; Hart et al., 2018; Rollins et al., 2022; Schwartz et al., 2021; Wywial et al., 2009). The PFam54 gene array can be separated into five major Clades where Clades I, II, III, and V share one‐to‐one orthology among the Bbsl species studied to date (Wywial et al., 2009). Clade IV, however, contains a variable number of paralogs and many species display unique Clade IV paralogs not found in other Bbsl species (Wywial et al., 2009). Furthermore, gene array members have been linked to specific host adaptations as well as being differentially expressed during tick and host infection (Caimano et al., 2019; Hart et al., 2018, 2021; Iyer et al., 2015) placing them as suitable candidate genes for study in relation to host and/or vector adaptation. However, the majority of genes present in the Bbsl genome, including the PFam54 gene array, are unique to Bbsl spirochetes reducing the ability to deduce potential function through comparison to other studied bacterial species (Schwartz et al., 2021). This is where comparative, population genomics can be leveraged to guide future studies through comparing within and among Bbsl species which differ in proposed host and/or vector adaptation.

Currently, three major Borrelia species act as LB‐causing agents across Eurasia namely B. afzelii, B. bavariensis, and B. garinii (Kurtenbach et al., 2006; Radolf et al., 2012; Stanek et al., 2011; Steere et al., 2016). All three Borrelia species share an Asian origin and have expanded into at least two tick transmission cycles (I. persulcatus, I. ricinus) with this expansion being adaptive toward colonizing a new tick vector (I. ricinus) in B. bavariensis (Becker et al., 2020; Gatzmann et al., 2015; Margos et al., 2019; Rollins et al., 2023). In both transmission cycles, these Borrelia species additionally utilize variable reservoir hosts either infecting rodent (B. afzelii, B. bavariensis) or avian (B. garinii) species (Comstedt et al., 2011; Kurtenbach et al., 2006; Margos et al., 2009; Munro et al., 2017). In the case of B. bavariensis and B. garinii, these species are sister taxa suggesting a host switch between rodent and avian reservoir hosts has occurred at some point during their evolutionary history (Becker et al., 2016; Margos et al., 2019). Selection for traits such as these can lead toward signatures of adaptation in the genome of these species which can provide information on what genes may be involved in specific phenotypes (Nielsen & Slatkin, 2013). As members of the PFam54 gene array encode proteins with known involvement toward host adaptation (Hart et al., 2018, 2021), we elected to focus on the evolutionary history of this gene family to determine if other genes present in the array may play a yet unknown role in Bbsl pathogenesis. Previous work on the diversity of the PFam54 gene array analyzed very few samples and, in the case of Eurasian distributed species, individual isolates (Wywial et al., 2009) or specific PFam54 clades have been studied (Hart et al., 2021). To determine what roles the PFam54 gene members may play in adaptation within Eurasian LB‐causing Bbsl spirochetes, we aimed to utilize recently published, whole genome sequencing data from 136 Eurasian Borrelia isolates (Rollins et al., 2023) along with published reference genomes (n = 5) so as to (1) characterize the diversity of the PFam54 gene array in these isolates to determine the naturally occurring level of genetic variation, (2) robustly reconstruct the phylogeny of the gene family and assign each gene to an orthologous group so as to enable (3) the search for signatures of diversifying selection within the reconstructed phylogeny in relation to different hypothesized reservoir hosts (rodent vs. bird) or tick vectors (I. ricinus vs. I. persulcatus). Altogether, these findings have the potential to open the door for novel directions in future research to understand how Bbsl species have adapted to novel host and vector species.

2. METHODS

2.1. Isolates and reconstruction of lp54 sequences

In this study, we aimed to determine the level of variation along the PFam54 gene array in B. afzelii, B. bavariensis, and B. garinii. For reconstruction of the lp54 sequences, on which the PFam54 gene array is located, we utilized the isolate library described in Rollins et al. (2023) containing MiSeq sequencing data for 136 Eurasian Borrelia isolates: B. afzelii (total n = 33, Asian n = 20, European n = 13), B. bavariensis (total n = 46, Asian n = 27, European n = 19), and B. garinii (total n = 57, Asian n = 25; European n = 32). Asian or European here refers to an isolate hypothesized to be maintained either in the I. persulcatus or I. ricinus transmission cycle, respectively, based on the geographic origin of isolation. Future analysis will be required though to determine each isolate's capacity to transmit through these tick species specifically.

Sequences of the linear plasmid lp54 were assembled based on the mapping protocol outlined previously (Becker et al., 2020; Rollins et al., 2023). In brief, Illumina reads (paired‐end reads of 250 bp) were first trimmed for Illumina MiSeq adapter sequences using Trimmomatic v.0.38 (Bolger et al., 2014) before being assembled using SPAdes v.3.13.0 (Bankevich et al., 2012). SPAdes contigs were then mapped to reference lp54 sequences (PacBio Sequences: PBi, A104S, NT24, PHei, PBr, and NT31 (Margos et al., 2018; Rollins et al., 2023); GenBank: PKo (CP002950.1), K78 (CP009059.1), and ACA‐1 (CP001247)) using NUCmer v.3.23 from the package MUMmer (Delcher et al., 2002; Kurtz et al., 2004). Lp54 identity was confirmed by searching for plasmid partitioning genes belonging to PFam32, 49, 50, and 57.62 families using BLAST v.2.8.1 (Altschul et al., 1990; Camacho et al., 2009) (algorithm: blastn) as outlined in (Becker et al., 2020; Rollins et al., 2023). Final lp54 sequences were determined in one of two ways: (1) a complete contig covering the full reference sequence and containing one or more of the partitioning genes mentioned above was taken without modification as the complete lp54 sequence, or (2) the lp54 was fragmented over two or more contigs for which the best reference (highest percent identity, highest overall coverage, and fewest structural variations) was used to guide reconstruction as outlined in (Becker et al., 2020). In this way, 136 lp54 sequences were reconstructed from NGS data to which the GenBank references used for mapping (n = 3) and additional GenBank lp54 sequences (n = 2; B. bavariensis, BgVir, CP003202.1; B. garinii, Far04, CP001318.1) were included in all future analyses bringing the total sample set analyzed to 141 sequences.

2.2. Identification and characterization of PFam54 gene array

Sequences for lp54‐located PFam54 paralogs described in (Wywial et al., 2009) for B. afzelii PKo (pko2060‐pko2071), B. bavariensis PBi (bga63‐bga73), B. garinii ZQ1 (zqa66‐zqa73), and B. burgdorferi B31 (bba64‐bba66, bba68‐70, bba73) were downloaded from GenBank (Accession Numbers: PKo, CP002950.1; PBi, CP000015.1; ZQ1, AJ786369.1; B31, AE000790.2) and used as queries (Note: GenBank and (Wywial et al., 2009) designations are not identical but numbering is). We used BLAST v.2.8.1 (Altschul et al., 1990; Camacho et al., 2009) (algorithm: blastn) to search for paralogs described above. A BLAST approach was chosen to conform to previous work to describe the PFam54 family (Wywial et al., 2009). Blast hits shorter than 500 bp and with a percentage identity lower than 80% compared to the reference were not considered paralogous. Further BLAST hits were removed if they were overlapping with regions already designated as a different paralog. BLAST hit lists were manually checked for intergenic regions >1000 bp, which were extracted and scanned for open reading frames in Aliview v.1.28 (Larsson, 2014). Final PFam54 gene sequences were compared against their own reference lp54 sequences and used to produce final gene lists. Gene assignments were checked through phylogenetic reconstruction (see below). Final gene lists were used to define PFam54 gene array architecture types (i.e., structure of gene array taking gene order, content, and gene/intergenic space length into account). An architecture type was defined based on the following rules: (1) same paralogs present in the same order, (2) gene length does not differ by more than ±50 bp, (3) intergenic spaces do not differ by more than ±100 bp.

2.3. Phylogenetic reconstruction and selection testing

To understand the evolution of the PFam54 gene family, a robust reconstruction of the evolutionary history of the orthologous genes in all borrelial isolates analyzed was required. We opted for phylogenetic reconstruction taking codon variation into account, which should capture the evolution of protein coding sequences better than simple nuclear substitution models (Goldman & Yang, 1994; Muse & Gaut, 1994). Only unique PFam54 sequences (n = 524 of 1308 sequences) were used for phylogenetic reconstruction. Final stop codons were removed before aligning as amino acids using MUSCLE v3.8.425 (Edgar, 2004a, 2004b) implemented in Aliview v1.28 (Larsson, 2014). Phylogenetic reconstruction was run in MrBayes v.3.2.6 (Huelsenbeck & Ronquist, 2001; Ronquist et al., 2012) with the following parameters: ploidy = haploid, codon substitution model with inverse gamma‐distributed rate variation, genetic‐code = universal, and assuming equal site selection (ω) (Goldman & Yang, 1994; Muse & Gaut, 1994). Three independent runs were launched for 50 million generations each. Convergence was checked with Tracer v.1.7.1 (Rambaut et al., 2018). Consensus trees were built using the sumt command from MrBayes using a respective burn‐in of 25%. Convergence to a single topology in all three independent runs was checked manually in FigTree v.1.4.4 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/). Gene orthology of individual paralogs (i.e., orthology groups) was based on the monophyletic clustering of individual gene copies either for single or multiple Borrelia species.

In addition to reconstructing the gene phylogeny, we further aimed to test for instances of diversifying selection. As signals of positive selection can often be hidden by negative selected sites (Zhang et al., 2005) and selection coefficients (ω n) could vary along different branches within the reconstructed gene phylogeny, we chose a model for selection inference that allows for variation in selection pressure between branches and sites. We tested for instances of diversifying selection along the tree reconstructed with the codon model in MrBayes using aBSREL v2.2 (Smith et al., 2015) from the HyPhy package (https://www.hyphy.org/) using the universal genetic code and not allowing for multiple hits. Positive selection on a branch is indicated by a significant result of the likelihood ratio test (LRT) performed by aBSREL after multiple testing corrections by the Holm–Bonferroni sequential rejection procedure. Four different kinds of branches were tested: branches separating species that utilize different vertebrate hosts (bird vs. rodent), branches separating isolates hypothesized to be maintained in transmission cycles involving different tick vectors (I. persulcatus, I. ricinus), genes that appear to have arisen through recombination based on our analysis (e.g., bga67b), or genes known to encode proteins that have been shown to provide protection from host‐immune mediated killing (zqa68, bga66 bga71, pko2068) (Hammerschmidt et al., 2014, 2016; Hart et al., 2018, 2021; Kraiczy, 2016). This resulted in a total of 44 branches being tested.

2.4. Determining gene gain and loss events along the PFam54 gene array

Gene gain and loss events were determined by reconstructing the phylogeny of the entire lp54 after removing any recombining region following the four‐gamete condition test as outlined in (Gatzmann et al., 2015; Rollins et al., 2023). Full, corrected lp54 sequences were aligned using MAFFT v.7.407 (Katoh et al., 2002; Katoh & Standley, 2013). Phylogenetic reconstruction was performed in MrBayes v.3.2.6 (Huelsenbeck & Ronquist, 2001; Ronquist et al., 2012) with ploidy set to haploid and a GTR (Tavaré, 1986) substitution model with inverse gamma‐distributed rate variation. Three independent runs were launched and ran for 10 million generations. Convergence was checked with Tracer v. 1.7.1 (Rambaut et al., 2018). Consensus trees were built using the sumt command from MrBayes using a respective burn‐in of 25%. Convergence to a single topology in all three independent runs was checked manually in FigTree v.1.4.4 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/). Gene gain or losses were then mapped onto the final lp54 tree using the maximum parsimony principle.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Clustering based on a binary matrix of orthology group (OG) presence or absence was run using classical multidimensional scaling (MDS) run with the cmdscale function using the base R package on a distance matrix calculated from the binary presence/absence plasmid data per isolate. Saturation curves were produced by randomly sampling architecture types 50 times for each number of isolates less than or equal to the total number of isolates present from a single species in each transmission cycle from all possible combinations of architecture types. The number of unique architecture types was determined per each random sample. The mean and standard deviation were calculated for each sampling event in R v.3.5.2 (R Core Team, 2019).

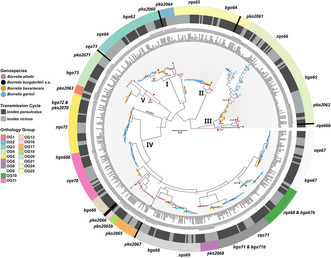

3. RESULTS

In total, 23 unique OGs could be described with 19 OGs being present in the 141 Eurasian B. afzelii, B. bavariensis, and B. garinii isolates studied (Table S1). In comparison to the three Borrelia species analyzed, B. burgdorferi sensu stricto (s.s.) strain B31, used as a reference, showed four unique OGs including OG14, OG15 (including bba68 or synonymous cspA), OG19, and OG23 (Table S1). Five novel PFam54 paralogs were identified only in Asian isolates of all species (pko2065b, bga67b, bga68b, bga71b, and zqa66b), most of which belong to Clade IV (n = 4). Certain reference genes (pko2069, pko2070, zqa73) based on (Wywial et al., 2009) could not be detected in any of the 141 Bbsl isolates analyzed (Table S2). Both B. afzelii and B. bavariensis displayed one major architecture type (Ba_A5, B. afzelii; Bba_A11, B. bavariensis) (Figure 1a) while B. garinii displayed multiple architecture types at similar frequencies (Figure 1a). In general, we observed a high number of variable PFam54 gene array architecture types with 8, 18, and 27 different architectures found in B. afzelii, B. bavariensis, and B. garinii, respectively (Figure 1a, Figures S1–S3, Table S3). Within these, Clade I, II, III, and V genes (Wywial et al., 2009) were generally present in all Borrelia isolates with the majority of variability arising due to differences in gene length (e.g., zqa66 in B. garinii, Figure S3) or absence/presence of Clade IV genes (Figures S1–S3, Table S2). Only pko2060 and zqa65 were found in all B. afzelii and B. garinii isolates, respectively, with all other identified paralogs being absent from at least one isolate (Table S2). MDS analysis based on the binary string of OG presence/absence showed that Borrelia species generally form independent groups with only a few samples not displaying clear clustering based on species identity (Figure 1b). In an effort to determine if our samples represented all possible PFam54 architecture types, we performed a saturation curve analysis. Only Asian B. bavariensis and B. garinii appeared to not reach an asymptote in this analysis suggesting there could be further architecture types present in both populations (Figure 1c, see Table S3 for additional information on individual architecture types per isolate).

FIGURE 1.

Diversity and prevalence of PFam54 architecture types identified in the 141 Eurasian isolates of B. afzelii, B. bavariensis, and B. garinii analyzed in this study. (a) Frequency of different architecture types present in the studied isolates (n = 141). Architecture types are separated by species (B. afzelii, B. bavarinesis, B. garinii). Colors correspond to tick transmission cycle (dark gray, I. persulcatus; light gray, I. ricinus). For information on the architecture of individual isolates see Table S3. (b) MDS clustering based on presence/absence matrix of orthology groups (OG) in each isolate. Here each point corresponds to a single Borrelia isolate. (c) Saturation curve analysis produced per species per transmission. In panels B and C, colors correspond to Borrelia species (purple, B. afzelii; orange, B. bavariensis; blue, B. garinii) and shapes correspond to the hypothesis tick transmission cycle based on the geographic origin of the isolates (I. persulcatus ▲, I. ricinus ●).

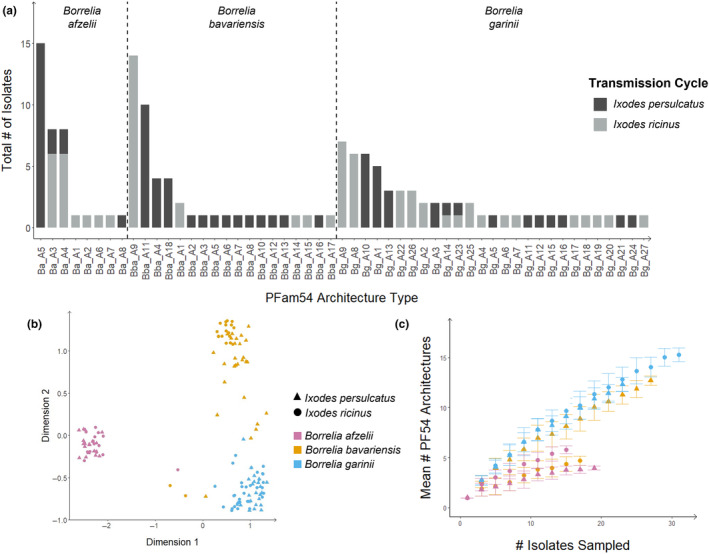

Most paralogs described (74%) are hypothesized to be present at the base of the lp54 phylogenies of the respective species (i.e., present for the entire evolutionary history of each Borrelia species studied) including two novel PFam54 paralogs, bga68b in B. bavariensis and pko2065b in B. afzelii (Figure 2). Variation in which paralogs were found per isolate appears to have arisen mostly through individual gene gain (n = 12) or loss (n = 56) events with losses being more common (Figure 2). Borrelia afzelii displayed the lowest number of gene gains or losses (n = 16) followed by B. garinii (n = 23) with B. bavariensis displaying the highest (n = 29).

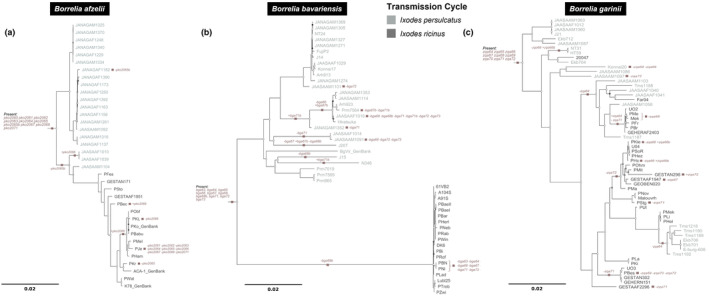

FIGURE 2.

Gene gain and loss events of PFam54 paralogs based on the principle of maximum parsimony mapped onto the phylogenetic tree reconstructed based on full lp54 sequences corrected for recombination based on the four‐gamete condition test described in (Gatzmann et al., 2015; Rollins et al., 2023) and with the PFam54 gene array removed. Phylogenetic reconstruction was performed in MrBayes v.3.2.6 (Huelsenbeck & Ronquist, 2001; Ronquist et al., 2012) with ploidy set to haploid and a GTR (Tavaré, 1986) substitution model with inverse gamma‐distributed rate variation. Three independent runs were launched and ran for 10 million generations at which point convergence of parameters was checked with Tracer v.1.7.1 (Rambaut et al., 2018). Consensus trees were built using the sumt command from MrBayes using a respective burn‐in of 25%. Convergence to a single topology in all three independent runs was checked manually in FigTree v.1.4.4 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/). Colors correspond to the hypothesis tick transmission cycle based on the geographic origin of the isolates (I. persulcatus or I. ricinus).

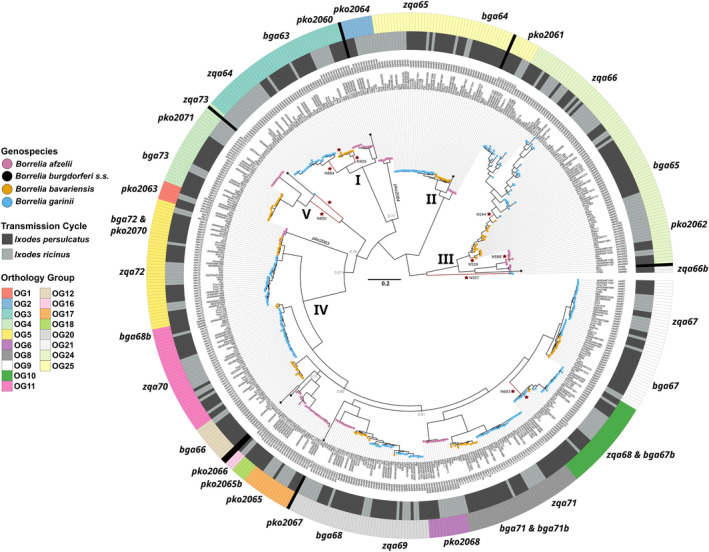

All five clades (I–V) originally described in (Wywial et al., 2009) were found in our dataset, although structuring of the clades deviated with Clade III being the most basal group (Figure 3) instead of Clade I as previously described (Wywial et al., 2009). The genes pko2063 and pko2064, which were previously not assigned to a Clade, form sister clades to Clade I and IV, respectively, but with lower node probability (pko2063, p = 0.57; pko2064, p = 0.77) and remain unique genes of B. afzelii (Figure 3). In the phylogenetic reconstruction of the PFam54 gene family, most genes form monophyletic clades by Borrelia species within each OG (Figure 3), although some paralogs do not follow this pattern. For example, zqa66 (B. garinii) and bga65 (B. bavariensis) form a monophyletic clade (Figure 3) with all zqa66 sequences forming a monophyletic clade within the larger zqa66/bga65 clade (Figure 3). A similar pattern can be seen for other B. bavariensis and B. garinii paralogs (bga68 and zqa69; bga67 and zqa67; bga64 and zqa65) where the genes do not form monophyletic clades purely based on species (Figure 3). Additionally, pko2071 of B. afzelii and bga73 of B. bavariensis form a monophyletic clade with the B. garinii paralog (zqa73) as a sister clade to pko2071/bga73 (Figure 3). Novel PFam54 paralogs clustered throughout the phylogeny with bga67b and bga68b of B. bavariensis being paralogs of B. garinii genes zqa68 and zqa70, respectively (Figure 3). Borrelia bavariensis gene bga71b clusters within bga71 but bga71b is paraphyletic (Figure 3). Borrelia afzelii gene pko2065b forms a sister clade to pko2065 with pko2066 being basal to both genes (Figure 3). Finally, zqa66b forms a single monophyletic clade which is a sister clade to the OG24 group (Clade III) containing pko2062, bga65, and zqa66 (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Phylogenetic tree of all, unique PFam54 paralogs identified in our analysis. In total, 1302 paralogs were identified which represented 524 unique sequences. Phylogenetic reconstruction was run in MrBayes v.3.2.6 (Huelsenbeck & Ronquist, 2001; Ronquist et al., 2012) with ploidy set to haploid and a codon substitution model with inverse gamma‐distributed rate variation, the universal genetic code, and assuming equal selection (ω) (Goldman & Yang, 1994; Muse & Gaut, 1994). Three independent runs were launched and ran for 50 million generations at which point convergence of parameters was checked with Tracer v.1.7.1 (Rambaut et al., 2018). Consensus trees were built using the sumt command from MrBayes using a respective burn‐in of 25%. Convergence to a single topology in all three independent runs was checked manually in FigTree v.1.4.4 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/). All internal nodes that had probabilities lower than 0.95 are shown in light gray. Orthology groups (OGs), based on the monophyletic clustering of an individual gene copy within the tree either for a single or multiple species, are shown in the outer ring. Hypothesized tick transmission cycle based on the geographic origin of the isolate is shown as either dark gray (I. persulcatus) or light gray (I. ricinus) in the inner ring. Individual paralog placements in the phylogeny are marked outside of these rings. Borrelia species are denoted by tip end color: purple (B. afzelii), orange (B. bavariensis), blue (B. garinii). Roman numerals (I–V) denote the PFam54 Clades as described in (Wywial et al., 2009). Red stars denote branches that were found to show significant instances of diversifying selection as determined by aBSREL v2.2 (Smith et al., 2015) from the HyPhy package (https://www.hyphy.org/) using the universal genetic code and not allowing for multiple hits.

Some proteins, predominantly encoded by Clade IV PFam54 genes, are known to play a role in immune evasion with influences to host and, potentially, vector adaptation (Gilmore et al., 2010; Hart et al., 2018; Patton et al., 2011, 2013). Host or vector adaptation could leave signatures of diversifying selection in genes related to this phenotype, such as genes encoding the PFam54. This allows us to test whether PFam54 paralogs of B. afzelii, B. bavariensis, and B. garinii are also implicated for host and/or vector adaptation by testing branches in the phylogeny which separate out clades that differ in which vector or host they are hypothesized to use. Of the 44 branches tested, 11 branches showed significant evidence for diversifying selection (Table S4). These were found in five OGs including OG3 (Clade 1), OG24 (Clade III), OG10 (Clade IV), OG4 (Clade V), and OG21 (Figure 3). Of these, four separated out clades of isolates are hypothesized to utilize either I. ricinus (Europe) or I. persulcatus (Asia) as vectors (N588, B. afzelii on pko2062; N526, B. bavariensis on bga65; terminal branch leading to B. bavariensis isolate PBi on bga63 and B. garinii isolate 20,047 on zqa68) (Figure 3; indicated by red stars). The other seven branches separate clades of isolates which differ in their proposed, reservoir hosts (rodent or bird) (Figure 3). Specifically, OG3 (Clade I) and OG24 (Clade III) where both branches leading either to rodent‐associated B. afzelii (N850) or B. bavariensis (N905) as well as bird‐associated B. garinii (zqa63 terminal branch for ZQ1, N884) displayed significant instances of diversifying selection. Genes with known functionality to human or host adaptation predominantly did not show signatures of diversifying selection (pko2068, B. afzelii; bga66 & bga71, B. bavariensis). Only the monophyletic clade containing zqa68 and the novel B. bavariensis gene bga67b showed evidence for diversifying selection but bga67b alone did not (Figure 3, Table S4).

4. DISCUSSION

Utilizing recently published whole genome sequences (n = 136) (Rollins et al., 2023) and GenBank reference genomes (n = 5) obtained from 141 Eurasian B. afzelii, B. bavariensis, and B. garinii isolates, we aimed to quantify the genetic variation along the PFam54 gene array and to analyze how PFam54 genes have evolved in these three Borrelia species known to differ within their host and vector adaptation (Comstedt et al., 2011; Kurtenbach et al., 2006; Margos et al., 2019). Our analyses highlighted the PFam54 gene array is more variable than previously expected, with novel paralogs found in all three Borrelia species studied. Additionally, genes displaying signatures of diversifying selection potentially in association with hypothesized vector and/or host adaption lie outside of Clade IV which has received the majority of interest in relation to Borrelia‐host infection mechanisms.

The isolates studied displayed a high number of different PFam54 architecture types which has also been partially observed for B. burgdorferi s.s., although based on analysis of five isolates (Wywial et al., 2009) with overall synteny of Clade IV genes being shown as well for further isolates (Hart et al., 2021). Architecture types do appear to be geographically restricted suggesting that they potentially have evolved over time due to the selection pressures associated with various biotic and abiotic conditions arising from different tick‐host transmission cycles. Of particular interest is that B. garinii appears to maintain many equally frequent PFam54 architecture types in contrast to B. afzelii and B. bavariensis (Figure 1a, Figure S3). This species‐specific pattern supports the findings of adaptation of certain Borrelia species to specific vertebrate hosts (i.e., individual bird species) (Lin, Diuk‐Wasser, et al., 2020; Lin, Frye, et al., 2020). This pattern is mirrored in the full genome where the plasmid content of B. garinii isolates tends to be smaller than in other Borrelia species (Rollins et al., 2023). Even so, these smaller genomes do not correspond to an overall reduction in plasmid diversity (Rollins et al., 2023). These findings could suggest a trend toward smaller but, potentially, specialized genomes. Genome reduction is commonly found in pathogenic microorganisms and may be due to adaptation to a parasitic lifestyle (Moran, 2002). If true, one could hypothesize that the variability in architecture types within B. garinii isolates could correspond to the capacity to infect specific bird species. Borrelia garinii selectively binds complement regulator Factor H of avian origin to protect itself from complement‐mediated killing and, thus facilitate infection of avian hosts (Hart et al., 2018, 2021; Sürth et al., 2021). Differences in susceptibility to complement in vitro therefore could be one of the possibilities to determine infection capacity of B. garinii isolates. Recent data has demonstrated variation in the susceptibility of B. garinii to avian complement from different terrestrial European bird species (Sürth et al., 2021), suggesting that host adaptation toward specific bird species could exist.

Our data revealed, regardless of the genetic variability, that the PFam54 gene array within the isolates studied has remained relatively stable over time as most paralogs (74% of all) are predicted to be present at the base of the lp54 phylogenies (Figure 2). Even so, only two PFam54 paralogs, pko2060 and zqa65, have been detected in all B. afzelii or B. garinii isolates, respectively, which could suggest one possibility that some genes are dispensable for completing the spirochetes tick‐host transmission cycle in the studied species. This includes the loss of genes encoding for proteins known to interact with the complement system of vertebrates, namely BGA66 and BGA71 of B. bavariensis, PKO2068 of B. afzelii, and ZQA68 of B. garinii (Hammerschmidt et al., 2016; Hart et al., 2021; Kraiczy, 2016). This is supported by recent work which showed that the loss of the whole PFam54 gene array in two B. bavariensis isolates (PBN, PNi) impacted susceptibility to human complement but did not influence infection of mice further highlighting the probable, functional redundancy in the overall Borrelia genome and especially in relation to the studied species (Rollins et al., 2022).

We identified a number of, so far, undescribed PFam54 paralogs including pko2065b (B. afzelii), bga67b (B. bavariensis), bga68b (B. bavariensis), bga71b (B. bavariensis), and zqa66b (B. garinii). As pko2065b and bga68b are suggested to be present at the base of the species‐specific lp54 phylogenies, it could be hypothesized that both genes have been maintained over the evolutionary history of B. afzelii and B. bavariensis, suggesting these genes could have a yet unknown function with importance to these species completing their lifecycle. For this, bga68b, and additionally bga67b, are paralogs, respectively, of zqa68 and zqa70 from B. garinii. Concerning the history of bga67b, this gene could have arisen through a recombination event between B. bavariensis and B. garinii, as suggested previously for genes located on the chromosome (Rollins et al., 2023). Of note, the ortholog of BGA67b in B. garinii, ZQA68, displays selective binding properties to the complement regulator Factor H of avian origin and thus protects spirochetes from complement‐mediated killing by avian innate immunity (Hart et al., 2018, 2021). Polymorphisms in complement‐interacting proteins of B. burgdorferi s.s. are known to influence potential host adaptation through complement binding (Hart et al., 2018, 2021; Lin, Diuk‐Wasser, et al., 2020; Lin, Frye, et al., 2020; Marcinkiewicz et al., 2018). Even though multiple single nucleotide polymorphisms are present when comparing the zqa68 and bga67b sequences, it is tempting to speculate that this paralog could enable Asian B. bavariensis isolates to circulate in birds as previously suggested in contrast to European B. bavariensis which is most likely a mammalian‐associated Borrelia species (Ishiguro et al., 2005; Margos et al., 2019; Munro et al., 2017; Rollins et al., 2023). However, further in vitro studies are required to understand the role(s) of these novel paralogs in host adaptation and immune evasion. We also observed the complete absence of specific, reference genes from all analyzed isolates (pko2069, pko2070, zqa73) (Table S2). Noteworthy, our analysis was based on short‐read sequencing technologies which have been shown in recent years to not capture the entirety of the complex Borrelia genome, with the use of long‐read technologies (e.g., PacBio) providing much better, but also not perfect, resolution (Combs et al., 2022; Hepner et al., 2023; Margos et al., 2017). This could explain the absence of some genes in our analysis and also the presence of many, singular architecture types potentially due to lower resolution in specific samples. Nevertheless, short‐reads have been shown to adequately reconstruct the lp54 where the PFam54 gene array is located (Margos et al., 2017) and previous work has shown that short‐read data was able to reconstruct the full absence of the PFam54 gene array in B. bavariensis isolates PBN and PNi with confirmation through long‐read sequencing (Rollins et al., 2022). Taken together, this suggests short‐read sequencing should be adequate to reconstruct the PFam54 gene array but future analysis should include long‐read sequencing data to determine any bias that could arise due to sequencing methodology.

The majority of branches that have experienced diversifying selection potentially in relation to host and/or vector adaptation (i.e., along branches separating clades hypothesized to utilize different vertebrate hosts or tick vectors) belonged to non‐Clade IV PFam54 genes that have not been directly linked to host and vector adaptation so far (Caimano et al., 2019; Hammerschmidt et al., 2014; Hart et al., 2021; Iyer et al., 2015; Wywial et al., 2009). Indeed, Clade IV paralogs encoding for proteins capable of binding vertebrate complement proteins/regulators only contained two branches displaying instances of diversifying selection both in the zqa68/bga67b clade (Figure 3). Genes belonging to Clades I and III (bga63, bga65, pko2062) displayed the majority of branches separating out isolates which are hypothesized to be transmitted by different ticks, potentially suggesting diversifying selection in relation to this phenotype. Previous work revealed that PFam54 Clade I and III paralogs bba64 and bba66 from B. burgdorferi s.s. are variably regulated during tick infection (Iyer et al., 2015). Additional studies have shown that some PFam54 members grouped in Clade I and III are important for tick transmission of B. burgdorferi s.s. to the mammalian host (Gilmore et al., 2010; Hart et al., 2018; Patton et al., 2011, 2013), potentially highlighting the importance of these paralogous proteins in host‐pathogen interactions. Clades I, III, and V contained branches also displaying instances of diversifying selection potentially linked to host adaptation (i.e., along branches separating clades with differences in the proposed reservoir host). Clades I, III, and V paralogs of B. burgdorferi s.s. have been shown to be upregulated during infection of tick‐infected mice (Caimano et al., 2019; Gilmore et al., 2008), but loss of these genes did not significantly impede host infection, although some variation in tissue tropism was observed (Caimano et al., 2019; Patton et al., 2011, 2013). These results highlight that PFam54 genes outside of Clade IV are most likely important for Borrelia transmission from the vector to the host but additional investigations are required to assess their role in host and/or vector adaptation within Eurasian‐distributed Borrelia species. Further studies are required to confirm the results of this correlative analysis and to assess the function of these particular paralogs regarding their complement‐inhibitory capacity.

Taken together, our results show that the PFam54 gene array of the three main causative agents of LB across Eurasia (B. afzelii, B. bavariensis, B. garinii) is highly variable in genetic architecture including gene content. Moreover, the signatures of diversifying selection identified emphasize a potential role of paralogs belonging to Clades I, III, and V in host and vector adaptation and, thus, in functionality toward the natural transmission cycles of the three Borrelia species investigated herein. Utilizing genomic data, we were able to elucidate the evolution of an important gene family and were able to generate testable hypotheses regarding which genes should be studied in relation to host and vector adaptation in the future. Taken together, our comparative analyses highlight the importance of investigating individual diversity in Borrelia species from a population genetics perspective. Analyses such as these can increase our understanding and guide future projects into Borrelia pathogenesis, with the overall goal to determine how vector‐borne pathogens evolve leading to the emergence of wildlife and human disease.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Janna Wülbern: Data curation (equal); formal analysis (supporting); investigation (equal); writing – original draft (supporting). Laura Windorfer: Formal analysis (equal); investigation (supporting); methodology (equal). Kozue Sato: Data curation (supporting); investigation (equal); writing – original draft (supporting). Minoru Nakao: Data curation (supporting); investigation (supporting). Sabrina Hepner: Investigation (supporting); writing – original draft (supporting). Gabriele Margos: Conceptualization (supporting); funding acquisition (supporting); project administration (supporting); supervision (supporting); writing – original draft (equal). Volker Fingerle: Conceptualization (supporting); funding acquisition (supporting); project administration (supporting); resources (equal); supervision (supporting); writing – original draft (equal). Hiroki Kawabata: Conceptualization (supporting); data curation (supporting); funding acquisition (supporting); project administration (supporting); writing – original draft (supporting). Noémie S. Becker: Conceptualization (lead); formal analysis (supporting); funding acquisition (lead); project administration (equal); supervision (equal); writing – original draft (equal). Peter Kraiczy: Conceptualization (equal); investigation (supporting); project administration (supporting); supervision (equal); writing – original draft (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Robert E. Rollins: Conceptualization (equal); data curation (lead); formal analysis (lead); investigation (lead); project administration (equal); supervision (equal); visualization (lead); writing – original draft (lead); writing – review and editing (lead).

FUNDING INFORMATION

The project was funded through the German Research Foundation (DFG Grant No. BE 5791/2‐1) (NSB, RER). The National Reference Centre for Borrelia was funded by the Robert‐Koch‐Institut, Berlin (VF, GM). Part of this work was supported by the LOEWE Center DRUID (Novel Drug Targets against Poverty‐Related and Neglected Tropical Infectious Diseases), projects C3 (PK).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no conflicts of interest to state.

Supporting information

Appendix S1.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank all past members of the Evolutionary Biology group at the LMU; Cecilia Hizo‐Teufel, Wiltrud Strehle, Christine Hartberger, and Sylvia Stockmeier and Nikolas Alig from the National Reference Centre for Borrelia, the National Institute of Infection Diseases in Tokyo for allowing us to work in their facilities, all members and especially Dr. Niels Dingemanse of the Behavioral Ecology group at LMU for allowing us to collect ticks in their study plots. We would further like to thank Georg Manthey and Dr. Kristian Ullrich for their support in bioinformatical analyses. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Wülbern, J. , Windorfer, L. , Sato, K. , Nakao, M. , Hepner, S. , Margos, G. , Fingerle, V. , Kawabata, H. , Becker, N. S. , Kraiczy, P. , & Rollins, R. E. (2024). Unprecedented genetic variability of PFam54 paralogs among Eurasian Lyme borreliosis‐causing spirochetes. Ecology and Evolution, 14, e11397. 10.1002/ece3.11397

Peter Kraiczy and Robert E. Rollins share joint senior authorship for this project.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All SRA files have been uploaded to GenBank under the BioProject numbers PRJNA327303, PRJNA449844, and PRJNA722378. All assembled lp54 sequences, finalized PFam54 gene lists and sequences, finalized trees (lp54 and PFam54), all MrBayes output files and alignments used, and HyPhY output files have been uploaded to a Mendeley Data repository and can be accessed at DOI: 10.17632/xy8wt4ty8f.1.

REFERENCES

- Altschul, S. F. , Gish, W. , Miller, W. , Myers, E. W. , & Lipman, D. J. (1990). Basic local alignment search tool. Journal of Molecular Biology, 215(3), 403–410. 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, J. P. , Du Clos, T. W. , Mold, C. , Kulkarni, H. , Hourcade, D. , & Wu, X. (2019). 21 ‐ the human complement system: Basic concepts and clinical relevance. In Rich R. R., Fleisher T. A., Shearer W. T., Schroeder H. W., Frew A. J., & Weyand C. M. (Eds.), Clinical immunology (5th ed., pp. 299–317). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Bankevich, A. , Nurk, S. , Antipov, D. , Gurevich, A. A. , Dvorkin, M. , Kulikov, A. S. , Lesin, V. M. , Nikolenko, S. I. , Pham, S. , Prjibelski, A. D. , Pyshkin, A. V. , Sirotkin, A. V. , Vyahhi, N. , Tesler, G. , Alekseyev, M. A. , & Pevzner, P. A. (2012). SPAdes: A New Genome Assembly Algorithm and Its Applications to Single‐Cell Sequencing. Journal of Computational Biology, 19(5), 455–477. 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker, N. S. , Margos, G. , Blum, H. , Krebs, S. , Graf, A. , Lane, R. S. , Castillo‐Ramírez, S. , Sing, A. , & Fingerle, V. (2016). Recurrent evolution of host and vector association in bacteria of the Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato species complex. BMC Genomics, 17(1), 734–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker, N. S. , Rollins, R. E. , Nosenko, K. , Paulus, A. , Martin, S. , Krebs, S. , Takano, A. , Sato, K. , Kovalev, S. Y. , Kawabata, H. , Fingerle, V. , & Margos, G. (2020). High conservation combined with high plasticity: Genomics and evolution of Borrelia bavariensis . BMC Genomics, 21, 702. 10.1186/s12864-020-07054-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger, A. M. , Lohse, M. , & Usadel, B. (2014). Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics, 30(15), 2114–2120. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caimano, M. J. , Groshong, A. M. , Belperron, A. , Mao, J. , Hawley, K. L. , Luthra, A. , Graham, D. E. , Earnhart, C. G. , Marconi, R. T. , Bockenstedt, L. K. , Blevins, J. S. , & Radolf, J. D. (2019). The RpoS gatekeeper in Borrelia burgdorferi: An invariant regulatory scheme that promotes spirochete persistence in reservoir hosts and niche diversity. Frontiers in Microbiology, 10, 1923. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caine, J. A. , Lin, Y.‐P. , Kessler, J. R. , Sato, H. , Leong, J. M. , & Coburn, J. (2017). Borrelia burgdorferi outer surface protein C (OspC) binds complement component C4b and confers bloodstream survival. Cellular Microbiology, 19(12), e12786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho, C. , Coulouris, G. , Avagyan, V. , Ma, N. , Papadopoulos, J. , Bealer, K. , & Madden, T. L. (2009). BLAST+: Architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics, 10, 1–9. 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casjens, S. , Mongodin, E. F. , Qiu, W. G. , Luft, B. J. , Schutzer, S. E. , Gilcrease, E. B. , Huang, W. M. , Vujadinovic, M. , Aron, J. K. , Vargas, L. C. , Freeman, S. , Radune, D. , Weidman, J. F. , Dimitrov, G. I. , Khouri, H. M. , Sosa, J. E. , Halpin, R. A. , Dunn, J. J. , & Fraser, C. M. (2012). Genome stability of Lyme disease spirochetes: Comparative genomics of Borrelia burgdorferi plasmids. PLoS One, 7(3), 3280. 10.1371/journal.pone.0033280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coburn, J. , Garcia, B. , Hu, L. T. , Jewett, M. W. , Kraiczy, P. , Norris, S. J. , & Skare, J. (2021). Lyme disease pathogenesis. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 42, 473–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combs, M. , Marcinkiewicz, A. L. , Dupuis, A. P. , Davis, A. D. , Lederman, P. , Nowak, T. A. , Stout, J. L. , Strle, K. , Fingerle, V. , Margos, G. , Ciota, A. T. , Diuk‐Wasser, M. A. , Kolokotronis, S.‐O. , & Lin, Y.‐P. (2022). Phylogenomic diversity elucidates mechanistic insights into Lyme Borreliae‐host association. MSystems, 7(4), e00488. 10.1128/msystems.00488-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comstedt, P. , Jakobsson, T. , & Bergström, S. (2011). Global ecology and epidemiology of Borrelia garinii spirochetes. Infection Ecology & Epidemiology, 1(1), 9545. 10.3402/iee.v1i0.9545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delcher, A. L. , Phillippy, A. , Carlton, J. , & Salzberg, S. L. (2002). Fast algorithms for large‐scale genome alignment and comparison. Nucleic Acids Research, 30(11), 2478–2483. 10.1093/nar/30.11.2478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulipati, V. , Meri, S. , & Panelius, J. (2020). Complement evasion strategies of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato. FEBS Letters, 594(16), 2645–2656. 10.1002/1873-3468.13894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar, R. C. (2004a). MUSCLE: A multiple sequence alignment method with reduced time and space complexity. BMC Bioinformatics, 5, 113. 10.1186/1471-2105-5-113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar, R. C. (2004b). MUSCLE: Multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Research, 32(5), 1792–1797. 10.1093/nar/gkh340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, C. , Casjens, S. , & Huang, W. (1997). Genomic sequence of a Lyme disease spirochaete, Borrelia burgdorferi . Nature, 390, 580–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, B. L. , Zhi, H. , Wager, B. , Höök, M. , & Skare, J. T. (2016). Borrelia burgdorferi BBK32 inhibits the classical pathway by blocking activation of the C1 complement complex. PLoS Pathogens, 12(1), e1005404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatzmann, F. , Metzler, D. , Krebs, S. , Blum, H. , Sing, A. , Takano, A. , Kawabata, H. , Fingerle, V. , Margos, G. , & Becker, N. S. (2015). NGS population genetics analyses reveal divergent evolution of a Lyme Borreliosis agent in Europe and Asia. Ticks and Tick‐Borne Diseases, 6(3), 344–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore, R. D. , Howison, R. R. , Dietrich, G. , Patton, T. G. , Clifton, D. R. , & Carroll, J. A. (2010). The bba64 gene of Borrelia burgdorferi, the Lyme disease agent, is critical for mammalian infection via tick bite transmission. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(16), 7515–7520. 10.1073/pnas.1000268107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore, R. D. , Howison, R. R. , Schmit, V. L. , & Carroll, J. A. (2008). Borrelia burgdorferi expression of the bba64, bba65, bba66, and bba73 genes in tissues during persistent infection in mice. Microbial Pathogenesis, 45(5), 355–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, N. , & Yang, Z. (1994). A codon‐based model of nucleotide substitution for protein‐coding DNA sequences. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 11(5), 725–736. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammerschmidt, C. , Klevenhaus, Y. , Koenigs, A. , Hallström, T. , Fingerle, V. , Skerka, C. , Pos, K. M. , Zipfel, P. F. , Wallich, R. , & Kraiczy, P. (2016). BGA66 and BGA71 facilitate complement resistance of Borrelia bavariensis by inhibiting assembly of the membrane attack complex. Molecular Microbiology, 99(2), 407–424. 10.1111/mmi.13239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammerschmidt, C. , Koenigs, A. , Siegel, C. , Hallström, T. , Skerka, C. , Wallich, R. , Zipfel, P. F. , & Kraiczy, P. (2014). Versatile roles of CspA orthologs in complement inactivation of serum‐resistant Lyme disease spirochetes. Infection and Immunity, 82(1), 380–392. 10.1128/IAI.01094-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart, T. , Dupuis, A. P. , Tufts, D. M. , Blom, A. M. , Starkey, S. R. , Rego, R. O. M. , Ram, S. , Kraiczy, P. , Kramer, L. D. , Diuk‐Wasser, M. A. , Kolokotronis, S. O. , & Lin, Y.‐P. (2021). Host tropism determination by convergent evolution of immunological evasion in the Lyme disease system. PLoS Pathogens, 17(7), 1–29. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart, T. , Thien, N. , Nguyen, T. , Nowak, N. A. , Zhang, F. , Linhardt, J. , Diuk‐wasser, M. , Ram, S. , Kraiczy, P. , & Lin, Y.‐P. (2018). Polymorphic factor H‐binding activity of CspA protects Lyme borreliae from the host complement in feeding ticks to facilitate tick‐ to‐host transmission. PLoS Pathogens, 14(5), e1007105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepner, S. , Kuleshov, K. , Tooming‐Kunderud, A. , Alig, N. , Gofton, A. , Casjens, S. , Rollins, R. E. , Dangel, A. , Mourkas, E. , Sheppard, S. K. , Wieser, A. , Hübner, J. , Sing, A. , Fingerle, V. , & Margos, G. (2023). A high fidelity approach to assembling the complex Borrelia genome. BMC Genomics, 24(1), 401. 10.1186/s12864-023-09500-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huelsenbeck, J. P. , & Ronquist, F. (2001). MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics, 17(8), 754–755. 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.8.754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiguro, F. , Takada, N. , & Masuzawa, T. (2005). Molecular evidence of the dispersal of Lyme disease Borrelia from the Asian continent to Japan via migratory birds. Japanese Journal of Infectious Diseases, 58(3), 184–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer, R. , Caimano, M. J. , Luthra, A. , Axline, D. , Corona, A. , Iacobas, D. A. , Radolf, J. D. , & Schwartz, I. (2015). Stage‐specific global alterations in the transcriptomes of Lyme disease spirochetes during tick feeding and following mammalian host adaptation. Molecular Microbiology, 95(3), 509–538. 10.1111/mmi.12882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh, K. , Misawa, K. , Kuma, K. , & Miyata, T. (2002). MAFFT: A novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Research, 30(14), 3059–3066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh, K. , & Standley, D. M. (2013). MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 30(4), 772–780. 10.1093/molbev/mst010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraiczy, P. (2016). Hide and seek: How Lyme disease spirochetes overcome complement attack. Frontiers in Immunology, 7, 385. 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraiczy, P. , & Stevenson, B. (2013). Complement regulator‐acquiring surface proteins of Borrelia burgdorferi: Structure, function and regulation of gene experession. Ticks and Tick‐Borne Diseases, 4, 26–34. 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.12.017.Two-stage [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtenbach, K. , Hanincová, K. , Tsao, J. I. , Margos, G. , Fish, D. , & Ogden, N. H. (2006). Fundamental processes in the evolutionary ecology of Lyme borreliosis. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 4(9), 660–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz, S. , Phillippy, A. , Delcher, A. L. , Smoot, M. , Shumway, M. , Antonescu, C. , & Salzberg, S. L. (2004). Versatile and open software for comparing large genomes. Genome Biology, 5, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson, A. (2014). AliView: A fast and lightweight alignment viewer and editor for large datasets. Bioinformatics, 30(22), 3276–3278. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.‐P. , Diuk‐Wasser, M. A. , Stevenson, B. , & Kraiczy, P. (2020). Complement evasion contributes to Lyme Borreliae–Host Associations. Trends in Parasitology, 36(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.‐P. , Frye, A. M. , Nowak, T. A. , & Kraiczy, P. (2020). New insights into CRASP‐mediated complement evasion in the Lyme disease enzootic cycle. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 10, 121. 10.3389/fcimb.2020.00001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcinkiewicz, A. L. , Lieknina, I. , Kotelovica, S. , Yang, X. , Kraiczy, P. , Pal, U. , Lin, Y.‐P. P. , & Tars, K. (2018). Eliminating factor H‐binding activity of Borrelia burgdorferi CspZ combined with virus‐like particle conjugation enhances its efficacy as a Lyme disease vaccine. Frontiers in Immunology, 9, 1–11. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margos, G. , Fingerle, V. , & Reynolds, S. (2019). Borrelia bavariensis: Vector switch, niche invasion, and geographical spread of a tick‐borne bacterial parasite. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 7(October), 1–20. 10.3389/fevo.2019.00401 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Margos, G. , Gofton, A. , Wibberg, D. , Dangel, A. , Marosevic, D. , Loh, S. M. , Oskam, C. , & Fingerle, V. (2018). The genus Borrelia reloaded. PLoS One, 13(12), 1–14. 10.1371/journal.pone.0208432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margos, G. , Hepner, S. , Mang, C. , Marosevic, D. , Reynolds, S. E. , Krebs, S. , Sing, A. , Derdakova, M. , Reiter, M. A. , & Fingerle, V. (2017). Lost in plasmids: Next generation sequencing and the complex genome of the tick‐borne pathogen Borrelia burgdorferi . BMC Genomics, 18(1), 422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margos, G. , Vollmer, S. A. , Cornet, M. , Garnier, M. , Fingerle, V. , Wilske, B. , Bormane, A. , Vitorino, L. , Collares‐Pereira, M. , Drancourt, M. , & Kurtenbach, K. (2009). A new Borrelia species defined by multilocus sequence analysis of housekeeping genes. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 75(16), 5410–5416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran, N. A. (2002). Microbial minimalism: Genome reduction in bacterial pathogens. Cell, 108(5), 583–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munro, H. J. , Ogden, N. H. , Lindsay, L. R. , Robertson, G. J. , Whitney, H. , & Lang, S. (2017). Evidence for Borrelia Bavariensis Infections of Ixodes Uriae within Seabird Colonies of the North Atlantic Ocean. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 83(20), 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muse, S. , & Gaut, B. S. (1994). A likelihood approach for comparing synonymous and nonsynonymous nucleotide substitution rates, with application to the chloroplast genome. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 11(5), 715–724. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, R. , & Slatkin, M. (2013). An Introdcution to population genetics: Theory and applications (6th ed.). Sinauer Associates, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, T. G. , Brandt, K. S. , Nolder, C. , Clifton, D. R. , Carroll, J. A. , & Gilmore, R. D. (2013). Borrelia burgdorferi bba66 gene inactivation results in attenuated mouse infection by tick transmission. Infection and Immunity, 81(7), 2488–2498. 10.1128/IAI.00140-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton, T. G. , Dietrich, G. , Dolan, M. C. , Piesman, J. , Carroll, J. A. , & Gilmore, R. D., Jr. (2011). Functional analysis of the Borrelia burgdorferi bba64 gene product in murine infection via tick infestation. PLoS One, 6(5), e19536. 10.1371/journal.pone.0019536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team . (2019). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Radolf, J. D. , Caimano, M. J. , Stevenson, B. , & Hu, L. T. (2012). Of ticks, mice and men: Understanding the dual‐host lifestyle of Lyme disease spirochaetes. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 10(2), 87–99. 10.1038/nrmicro2714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rambaut, A. , Drummond, A. J. , Xie, D. , Baele, G. , & Suchard, M. A. (2018). Posterior summarization in Bayesian phylogenetics using tracer 1.7. Systematic Biology, 67(5), 901–904. 10.1093/sysbio/syy032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollins, R. E. , Sato, K. , Nakao, M. , Tawfeeq, M. T. , Herrera‐Mesías, F. , Pereira, R. J. , Kovalev, S. , Margos, G. , Fingerle, V. , Kawabata, H. , & Becker, N. S. (2023). Out of Asia? Expansion of Eurasian Lyme borreliosis causing genospecies display unique evolutionary trajectories. Molecular Ecology, 32(4), 786–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollins, R. E. , Wülbern, J. , Röttgerding, F. , Nowak, T. A. , Hepner, S. , Fingerle, V. , Margos, G. , Lin, Y.‐P. , Kraiczy, P. , & Becker, N. S. (2022). Utilizing two Borrelia bavariensis isolates naturally lacking the PFam54 gene Array to elucidate the roles of PFam54‐encoded proteins. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 88(5), e01555‐21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist, F. , Teslenko, M. , Van Der Mark, P. , Ayres, D. L. , Darling, A. , Höhna, S. , Larget, B. , Liu, L. , Suchard, M. A. , & Huelsenbeck, J. P. (2012). MrBayes 3.2: Efficient bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Systematic Biology, 61(3), 539–542. 10.1093/sysbio/sys029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, I. , Margos, G. , Casjens, S. R. , Qiu, W. G. , & Eggers, C. H. (2021). Multipartite genome of Lyme disease Borrelia: Structure, variation and prophages. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 42, 409–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skare, J. T. , & Garcia, B. L. (2020). Complement evasion by Lyme disease spirochetes. Trends in Microbiology, 28(11), 889–899. 10.1016/j.tim.2020.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M. D. , Wertheim, J. O. , Weaver, S. , Murrell, B. , Scheffler, K. , & Kosakovsky Pond, S. L. (2015). Less is more: An adaptive branch‐site random effects model for efficient detection of episodic diversifying selection. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 32(5), 1342–1353. 10.1093/molbev/msv022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanek, G. , Fingerle, V. , Hunfeld, K.‐P. , Jaulhac, B. , Kaiser, R. , Krause, A. , Kristoferitsch, W. , O'Connell, S. , Ornstein, K. , Strle, F. , & Gray, J. (2011). Lyme borreliosis: Clinical case definitions for diagnosis and management in Europe. Clinical Microbiology and Infection, 17, 69–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steere, A. C. , Strle, F. , Wormser, G. P. , Hu, L. T. , Branda, J. A. , Hovius, J. W. R. , Li, X. , & Mead, P. S. (2016). Lyme borreliosis. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 2, 90. 10.1038/nrdp.2016.90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sürth, V. , Lopes de Carvalho, I. , Núncio, M. S. , Norte, A. C. , & Kraiczy, P. (2021). Bactericidal activity of avian complement: A contribution to understand avian‐host tropism of Lyme borreliae. Parasites and Vectors, 14(1), 1–7. 10.1186/s13071-021-04959-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavaré, S. (1986). Some probabilistic and Statistial problems in the analysis of DNA sequences. Lectures on Mathematics in Teh Life Sciences, 17, 57–86. [Google Scholar]

- Wywial, E. , Haven, J. , Casjens, S. R. , Hernandez, Y. A. , Singh, S. , Monogodin, E. F. , Fraser‐Ligget, C. M. , Luft, B. J. , Schutzer, S. E. , & Qiu, W. G. (2009). Fast, adaptive evolution at a bacterial host‐resistance locus: The PFam54 gene Array in Borrelia burgdorferi . Gene, 445(1–2), 26–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie, J. , Zhi, H. , Garrigues, R. J. , Keightley, A. , Garcia, B. L. , & Skare, J. T. (2019). Structural determination of the complement inhibitory domain of Borrelia burgdorferi BBK32 provides insight into classical pathway complement evasion by Lyme disease spirochetes. PLoS Pathogens, 15(3), e1007659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J. , Nielsen, R. , & Yang, Z. (2005). Evaluation of an improved branch‐site likelihood method for detecting positive selection at the molecular level. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 22(12), 2472–2479. 10.1093/molbev/msi237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1.

Data Availability Statement

All SRA files have been uploaded to GenBank under the BioProject numbers PRJNA327303, PRJNA449844, and PRJNA722378. All assembled lp54 sequences, finalized PFam54 gene lists and sequences, finalized trees (lp54 and PFam54), all MrBayes output files and alignments used, and HyPhY output files have been uploaded to a Mendeley Data repository and can be accessed at DOI: 10.17632/xy8wt4ty8f.1.