Abstract

Warfarin remains the most prescribed oral anticoagulant of choice in atrial fibrillation (AF) patient in resource-limited settings. Despite evidence linking Time in Therapeutic Range (TTR) to patient outcomes, its use in clinical practice is not widespread. This prospective study explores the impact of a TTR-INR guided Warfarin adjustment protocol on TTR in AF patients. Conducted at the Warfarin clinic of King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital. TTR was calculated using the Rosendaal linear interpolation method at baseline, and then at 6 and 12 months post-protocol implementation. The primary outcome was the improvement in TTR following the protocol’s implementation. The study analyzed 57 patients, with a mean age of 72 years and an even gender distribution. At baseline, 53% of patients had a TTR of less than 65%. However, TTR significantly improved from 65% at baseline to 80% after 12 months of protocol implementation (p < 0.001). Furthermore, there was a significant increase in the proportion of patients with a TTR of 65% or more, from 47 to 88% (p < 0.001). During the follow-up period in the first 12 months, three patients died, but no ischemic or major bleeding events occurred. The significant improvement in TTR after 12 months of protocol implementation suggests that this strategy could provide additional value in improving TTR and outcomes in AF patients receiving Warfarin.

Keywords: Atrial fibrillation (AF), Time in therapeutic range (TTR), International normalized ratio (INR), Vitamin K antagonist (VKA), Oral anticoagulants (OACs), Non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs)

Subject terms: Cardiology, Atrial fibrillation

Introduction

Atrial Fibrillation (AF) is a common cardiac arrhythmia, affecting approximately 1–2% of the general population. It is associated with an increased risk of thrombotic events in the neurological system, especially stroke1–4. Anti-coagulant therapy is a standard of practice for ischemic stroke prevention in patients with AF. n Thailand, warfarin, a widely available vitamin K antagonist (VKA), is the standard anticoagulant therapy for ischemic stroke prevention in AF patients. However, studies have shown that non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs) are at least non-inferior, if not superior, to warfarin in stroke prevention5, with a better safety profile6. Interestingly, NOACs are not included in the Thailand National List of Essential Medicines (NLEM), while warfarin is listed. This discrepancy poses challenges in clinical practice for ischemic event prevention in AF patients in Thailand.

Time in Therapeutic Range (TTR), calculated from International Normalized Ratio (INR) measurements, reflects how well warfarin is managed. Patients with TTR less than 60% have higher mortality rates and bleeding complications, while those with higher TTR have better survival rates7,8. The accepted target TTR is 65–70% or higher for optimal clinical outcomes with fewer complications6,9.

Despite studies advocating for the use of TTR in monitoring patients on Vitamin K Antagonists (VKA), with a target range of 65–70% or higher, its adoption has been limited due to a lack of evidence supporting its benefits for Thai patients. Furthermore, the inability to switch from VKAs to Novel Oral Anticoagulants (NOACs) due to restrictions in the NLEM and socioeconomic factors of patients, warfarin remains the primary anticoagulant used in stroke prevention for patients with AF in Thailand.

The current standard for adjusting warfarin dosage is primarily based on the patient’s INR levels, without considering TTR. This research, however, introduces a novel approach: a TTR-INR guided warfarin adjustment protocol. This protocol, adapted from the Hamilton Dosing Nomogram and treatment guidelines endorsed by the Thai Heart Association for patients on oral anticoagulants, categorizes patients into two groups based on their initial TTR values:

Patients with TTR levels below the standard threshold (TTR < 65%).

Patients with TTR levels within or above the standard threshold (TTR ≥ 65%).

Upon implementing this protocol, its efficacy will be assessed by monitoring the changes in the number of patients achieving the standard TTR threshold (TTR ≥ 65%). The objective of this research is to evaluate the efficacy of warfarin dose adjustment guidelines, both before and after the incorporation of TTR and INR assistance. It is hypothesized that patients with TTR levels below the standard threshold (TTR < 65%) will experience an increase in TTR levels following warfarin dosage adjustments guided by the TTR-INR assisted protocol. This intervention is expected to lead to a decrease in thromboembolic events within the cerebral and peripheral vascular systems, and a subsequent reduction in hemorrhagic occurrences.

Material and method

Study design

This prospective cohort, non-randomized, single-center study was conducted in Warfarin Clinic, King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Research Ethics Review Committee for Research Involving Human Research Participants, Health Sciences Group, Chulalongkorn University (COA No. 202/2021, IRB No. 899/63), and is in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1983, was registered in Thai Clinical Trials Registry (TCTR20201224003, Date of registration: 24/12/2020).

Patient enrollment

The study enrolled consecutive patients diagnosed with Non-Valvular Atrial Fibrillation (NVAF), confirmed by either a 12-lead ECG or an ECG strip showing at least 30 s of AF, including those recorded by wearable devices. These patients were receiving warfarin treatment and were part of a study conducted at King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital from February 1, 2021, to February 1, 2022.

The inclusion criteria required patients to be aged 18 years or older, have a minimum of 2 years of warfarin use, and have undergone at least 3 separate INR measurements. The exclusion criteria included significant valvular heart disease, pregnancy, atrial fibrillation associated with transient reversible causes, recent use of Novel Oral Anticoagulants (NOACs) within the past 2 years, and inability or refusal to attend follow-up appointments. All participants provided written informed consent prior to their participation in the study.

TTR calculation and warfarin adjustment protocol

The percentage of time a patient maintained an International Normalized Ratio (INR) between 2 and 3 was determined using the Rosendaal linear interpolation method7. Patients were categorized into two groups based on their anticoagulant control:

Poor anticoagulant control (Group 1): Defined as a Time in Therapeutic Range (TTR) less than 65%.

Good anticoagulant control (Group 2): Defined as a TTR of 65% or higher.

All participants underwent warfarin dose adjustments according to the TTR-INR guided warfarin adjustment protocol, detailed in Table S5 of the supplementary appendix. The TTR was calculated at three different time points: at baseline, 6 months, and 12 months after the implementation of the protocol.

Clinical follow-up and protocol assessment

Clinical follow-up was conducted for up to one year at the warfarin clinic, either during outpatient visits or through telephone interviews. The feasibility of the TTR-INR guided warfarin adjustment protocol was assessed using a questionnaire, and any protocol violations were recorded. The protocol’s accuracy, efficacy, and safety were evaluated by a team of two cardiologists and one hematologist. To ensure the reliability of the questionnaire used in the study, a reliability analysis was performed using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. The analysis yielded a value of 0.85.

Data collection

Baseline clinical characteristics, including demographic information, medical history, medication, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), and laboratory tests (complete blood count, renal function tests, electrolytes, liver function tests, and INR) were collected from patient medical records. Ischemic and bleeding risk scores were calculated using the SAMe-TT2R2, CHA2DS2-VASc, and HAS-BLED scoring systems. Major bleeding, clinically relevant non-major bleeding (CRNM), and minor bleeding were categorized according to the 2005 International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) criteria. Renal disease, pulmonary disease, and liver disease were defined based on laboratory data and medical record documentation.

Sample size calculation

To calculate the sample size for a census study aiming to detect a minimum clinically important difference of 20% in categorical data with two independent groups, the following parameters are used:

N = Sample size (93).

Z1-α/2 = 1.96 (for α = 0.05, two-tailed test).

Z1-β = 0.84 (for β = 0.2, power = 80%).

P1 = Proportion of patients with TTR ≥ 65% before protocol implementation (55%).

P2 = Proportion of patients with TTR ≥ 65% after protocol implementation (75%).

MCD = Minimal clinically important difference (20%), Drop-out rate = 10%

Given the study duration of up to 1 year and considering a potential drop-out rate of 10%, the sample size is adjusted to 93 individuals.

This sample size calculation ensures that the study will have sufficient power to detect the specified clinically important difference with a significance level of 0.05 and a power of 80%.

Outcomes

The primary endpoint of this study was the change in Time in Therapeutic Range (TTR) after the implementation of the protocol.

The secondary endpoints included: the feasibility of the protocol and any violations that occurred, the proportion of patients who switched to using NOACs, the incidence of ischemic stroke, the occurrence of bleeding events, and all-cause mortality.

Statistical analysis

Categorical data was presented as frequency and percentage. Continuous data was presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for normal distribution, and as median for skewed distribution.

Categorical data were compared using McNemar’s Chi-square test and continuous paired data was compared using paired t-test.

P-value < 0.05 was accepted as statistically significant. All statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 28 statistical software.

Ethical approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board and the Ethics Committee of Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University (COA No. 202/2021, IRB No. 899/63).

Informed consent statement

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Results

From February 1, 2021, to February 1, 2022, we screened a total of 95 consecutive patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) at King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital, Bangkok. Out of these, 73 patients were undergoing treatment with warfarin and were thus enrolled in our study. However, 16 patients had to be excluded due to incomplete data. The reasons for exclusion were as follows: 10 were lost to follow-up, 2 declined to participate, 3 had reasons to target an INR of more than 2.0–3.0, and 1 had a high INR (> 4.99) at the enrollment date. A total of 57 NVAF patients who were treated with warfarin had complete data for TTR calculation were included in this study.

Baseline characteristics

This study included 57 participants with an average age of 72 ± 11 years, 50% were female. The mean left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was 56%, with 17% of the patients having an LVEF less than 40%. 32% of the patients reported ischemic heart diseases (IHD), 57% had hypertension, 36% had diabetes mellitus, 46% had dyslipidemia, and 21% had a history of stroke. Additionally, 21% had chronic kidney disease (CKD) at least at stage III, 1.8% had end-stage renal disease (ESRD), and 45% had a history of heart failure (HF) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population compared between patients with TTR ≥ 65% and patients with TTR < 65%

| Characteristics | All patients (n = 57) N (%) or Mean ± SD | TTR < 65% (n = 30) N (%) or Mean ± SD | TTR ≥ 65% (n = 27) N (%) or Mean ± SD | P-value1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General information | ||||

| Age (years) | 72 ± 11 | 73 ± 12 | 70 ± 10 | 0.278 |

| Female | 28 (50) | 16 (48.48) | 12 (52.17) | 0.786 |

| LV systolic function (LVEF) | 55.98 ± 15.39 | 55.76 ± 16.18 | 56.37 ± 14.32 | 0.892 |

| LVEF ≤ 40% | 9 (17.31) | 6 (18.18) | 3 (15.79) | 0.911 |

| LVEF 41–49% | 7 (13.46) | 5 (15.15) | 2 (10.53) | |

| LVEF ≥ 50% | 36 (69.23) | 22 (66.67) | 14 (73.68) | |

| Medical history | ||||

| Heart failure | 25 (44.64) | 16 (48.48) | 9 (39.13) | 0.488 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 20 (35.71) | 11 (33.33) | 9 (39.13) | 0.656 |

| Coronary artery disease | 18 (32.14) | 11 (33.33) | 7 (30.43) | 0.819 |

| Prior PCI | 8 (14.29) | 5 (15.15) | 3 (13.04) | 1.000 |

| Prior CABG | 5 (8.93) | 2 (6.06) | 3 (13.04) | 0.392 |

| Hypertension | 32 (57.14) | 17 (51.52) | 15 (65.22) | 0.308 |

| Dyslipidemia | 26 (46.43) | 15 (45.45) | 12 (52.17) | 0.621 |

| Old CVA | 12 (21.43) | 8 (24.24) | 4 (17.39) | 0.743 |

| CKD stage ≥ 3 | 12 (21.43) | 10 (30.30) | 2 (8.70) | 0.053 |

| ESRD | 1 (1.79) | 1 (3.03) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| PAD | 1 (1.79) | 1 (3.03) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Cirrhosis | 2 (3.57) | 1 (3.03) | 1 (4.35) | 1.000 |

| COPD | 2 (3.57) | 1 (3.03) | 1 (4.35) | 1.000 |

| OSA | 4 (7.14) | 1 (3.03) | 3 (39.13) | 0.295 |

| Cancer | 6 (10.71) | 15 (15.15) | 1 (4.35) | 0.383 |

| Cardiac implantable electronic device (CIED) | ||||

| PPM | 9 (16.07) | 6 (18.18) | 3 (13.04) | 0.607 |

| ICD | 2 (3.57) | 2 (6.06) | 0 (0) | 0.507 |

| CRT | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Procedure | ||||

| AF RFA | 3 (5.36) | 1 (3.03) | 2 (8.70) | 0.562 |

| AV node ablation | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Medications | ||||

| Furosemide | 28 (50) | 18 (54.55) | 10 (43.48) | 0.415 |

| Spironolactone | 7 (12.50) | 5 (15.15) | 2 (8.70) | 0.688 |

| Statin | 46 (82.14) | 29 (87.88) | 17 (73.91) | 0.179 |

| Beta blocker | 41 (73.21) | 25 (75.76) | 16 (69.57) | 0.607 |

| ACEI | 11 (19.64) | 7 (21.21) | 3 (39.13) | 0.723 |

| ARB | 16 (28.57) | 7 (21.21) | 4 (17.39) | 0.144 |

| Sacubitril/Valsartan (ARNI) | 2 (3.57) | 2 (6.06) | 0 (0) | 0.507 |

| Digoxin | 7 (12.50) | 5 (15.15) | 2 (8.70) | 0.688 |

| Hydralazine | 2 (3.57) | 2 (6.06) | 0 (0) | 0.507 |

| Nitrate | 4 (7.14) | 4 (12.12) | 0 (0) | 0.136 |

| Warfarin (dose: mg/week) | 21.02 ± 9.69 (Mean 18) | 22.33 ± 11.12 (Mean 19.5) | 19.13 ± 9.98 (Mean 18) | 0.363 |

| Aspirin | 1 (1.79) | 0 (0) | 1 (4.35) | 0.411 |

| P2Y12 inhibitor (Clopidogrel) | 1 (1.79) | 1 (3.03) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Laboratory investigation | ||||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.66 ± 2.00 | 12.24 ± 2.10 | 13.27 ± 1.69 | 0.055 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 38.59 ± 5.69 | 37.36 ± 5.88 | 40.36 ± 5.00 | 0.055 |

| Platelet (cu.mm2) | 221,200 ± 70,560 | 229,180 ± 78,250 | 209,740 ± 57,530 | 0.315 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | 20.31 ± 11.61 | 23.52 ± 13.75 | 15.50 ± 4.25 | 0.010 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.23 ± 0.67 | 1.34 ± 0.82 | 1.06 ± 0.32 | 0.212 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 140.04 ± 2.40 | 139.70 ± 2.63 | 140.55 ± 1.95 | 0.314 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 4.11 ± 0.40 | 4.16 ± 0.41 | 4.03 ± 0.38 | 0.241 |

| Chloride (mmol/L) | 104.62 ± 3.27 | 104.15 ± 3.92 | 105.32 ± 1.81 | 0.144 |

| Bicarbonate (mmol/L) | 27.20 ± 2.93 | 27.24 ± 2.84 | 27.14 ± 3.12 | 0.897 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.78 ± 0.72 | 3.73 ± 0.42 | 3.85 ± 1.01 | 0.046 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.91 ± 0.54 | 0.97 ± 0.58 | 0.81 ± 0.45 | 0.353 |

| Direct bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.44 ± 0.30 | 0.48 ± 0.34 | 0.37 ± 0.21 | 0.271 |

| AST (SGOT) (U/L) | 25.48 ± 9.75 | 25.36 ± 9.12 | 25.67 ± 10.90 | 0.901 |

| ALT (SGPT) (U/L) | 22.28 ± 11.17 | 20.15 ± 9.05 | 25.62 ± 13.44 | 0.126 |

| ALP (U/L) | 86.23 ± 39.27 | 94.36 ± 44.94 | 74.26 ± 25.64 | 0.068 |

1P-value for comparison between patients with TTR ≥ 65% and TTR < 65%

Significant values are in bold.

All patients were treated with warfarin, with an average dose of 21.02 ± 9.69 mg per week and a median dose of 18 mg per week. The average CHA2DS2-VASc score, HAS-BLED score, and SAMe-TT2R2 score were 3.82 ± 1.82, 2.13 ± 1.01, and 3.30 ± 0.74, respectively. The average TTR was 64.69 ± 20.14% (mean = 62.78%). Notably, 30 patients (52.63%) fell into the poor anticoagulant control group, with a TTR less than 65%. These findings are detailed in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2.

Risk scores of the study population compared between patients with TTR ≥ 65% and patients with TTR < 65%

| Risk score | All patients (n = 57) N (%) or Mean ± SD | TTR < 65% (n = 30) N (%) or Mean ± SD | TTR ≥ 65% (n = 27) N (%) or Mean ± SD | P value1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHA2DS2-VASc score | ||||

| Total score | 3.82 ± 1.82 | 3.97 ± 1.90 | 3.61 ± 1.73 | 0.436 |

| Number of positive each component | ||||

| Congestive heart failure/ LV dysfunction | 25 (44.64) | 19 (57.58) | 6 (26.09) | 0.020 |

| Hypertension | 36 (64.29) | 18 (54.55) | 18 (78.26) | 0.068 |

| Age > 75 years | 24 (35.71) | 16 (48.48) | 8 (34.78) | 0.308 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 20 (35.71) | 12 (36.36) | 8 (34.78) | 0.903 |

| Stroke/TIA/thromboembolism | 11 (19.64) | 6 (18.18) | 5 (21.74) | 0.742 |

| Vascular disease | 16 (28.57) | 11 (33.33) | 5 (21.74) | 0.345 |

| Age 65–74 years | 19 (33.93) | 11 (33.33) | 8 (34.78) | 0.910 |

| Sex categrophy (female sex) | 28 (50) | 16 (48.48) | 12 (52.17) | 0.786 |

| HAS-BLED score | ||||

| Total score | 2.13 ± 1.01 | 2.39 ± 1.09 | 1.74 ± 0.75 | 0.016 |

| Number of positive each component | ||||

| Hypertension | 36 (64.29) | 18 (54.55) | 18 (78.26) | 0.068 |

| Abnormal liver or renal function | 36 (64.29) | 6 (18.18) | 1 (4.35) | 0.220 |

| Stroke | 11 (19.64) | 6 (18.18) | 5 (21.74) | 0.742 |

| Bleeding | 2 (3.57) | 2 (6.06) | 0 (0) | 0.507 |

| Labile INR | 22 (39.29) | 22 (66.67) | 0 (0) | < 0.001 |

| Elderly (> 65 years) | 39 (69.64) | 24 (72.73) | 15 (65.22) | 0.548 |

| Drug or alcohol | 2 (3.57) | 1 (3.03) | 1 (4.35) | 1.000 |

| SAMe-TT2R2 score | ||||

| Total score | 3.30 ± 0.74 | 3.21 ± 0.60 | 3.43 ± 0.90 | 0.249 |

| Number of positive each component | ||||

| Sex (female) | 28 (50) | 16 (48.48) | 12 (52.17) | 0.786 |

| Age (< 60 years) | 7 (12.5) | 4 (12.12) | 3 (13.04) | 1.000 |

| Medical history | 33 (58.93) | 20 (60.61) | 13 (56.52) | 0.261 |

| Treatment (rhythm control strategy) | 1 (1.79) | 0 (0) | 1 (4.35) | 0.411 |

| Tobacco use (within 2 years) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Race (non-Caucasian) | 56 (100) | 33 (100) | 23 (100) | – |

1P-value for comparison between patients with TTR ≥ 65% and TTR < 65%

The CHA2DS2-VASc score calculates stroke risk for patients with AF, ranging from 0 to 9 (higher scores indicating a greater risk of stroke).

The HAS-BLED score predicts major bleeding risk and estimates the risk of major bleeding for patients on anticoagulation to assess the quality of atrial fibrillation care, also ranging from 0 to 9 (higher scores indicating a higher risk of major bleeding for patients on anticoagulation).

The SAMe-TT2R2 score aids decision-making between a non-VKA oral anticoagulant (NOAC) and a vitamin K antagonist (VKA). A score of 0–2 suggests the patient would benefit from a VKA, while a score > 2 indicates the use of alternative strategies (e.g., NOAC).

Table 3.

Baseline TTR of the study population compared between patients with TTR ≥ 65% and patients with TTR < 65%

| Baseline TTR | All patients (n = 57) | TTR < 65% (n = 30) | TTR ≥ 65% (n = 27) | P-value1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TTR (Mean ± SD) | 64.69 ± 20.14 | 49.50 ± 13.15 | 81.56 ± 10.89 | < 0.001 |

| TTR (Median) | 62.78 | 54.88 | 79.40 | < 0.001 |

1P-value for comparison between patients with TTR ≥ 65% and TTR < 65.

Significant values are in bold.

In our study, patients in the poor anticoagulant control group (TTR less than 65%) had higher BUN and HAS-BLED scores compared to those in the good anticoagulant control group. Specifically, the BUN was 23.52 ± 13.75 versus 15.50 ± 4.25 (p = 0.01), and the HAS-BLED scores were 2.39 ± 1.09 versus 1.74 ± 0.75 (p = 0.016).

Furthermore, patients in the poor anticoagulant control group had a lower serum albumin level than those in the good control group (3.73 ± 0.42 versus 3.85 ± 1.01; p = 0.046). However, no significant differences were observed between the two groups in terms of age, sex, LVEF, number of prior cardiovascular diseases, drugs used (including statin, diuretic, beta-blocker, ACEI/ARB/ARNI, digoxin, hydralazine, nitrate, anticoagulant, aspirin, and P2Y12 inhibitor), CHA2DS2-VASc score, SAMe-TT2R2 score, history of Cardiac Implantable Electronic Devices (CIED), and other laboratory testing.

The baseline characteristics of the study population, compared between patients with TTR ≥ 65% and patients with TTR < 65%, are shown in Table 1.

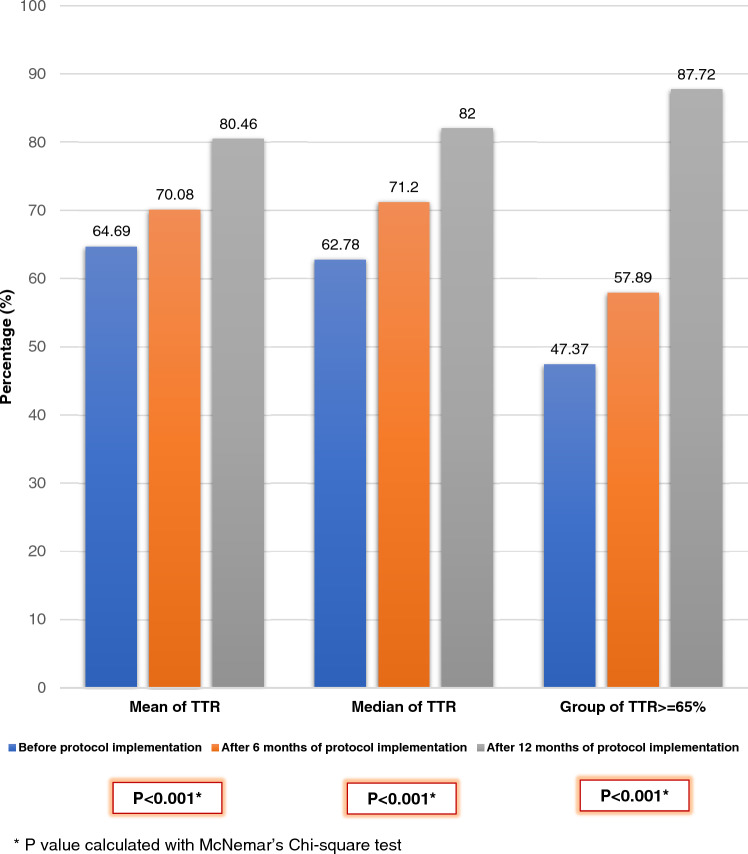

Primary outcome

Twelve months after the implementation of the protocol, there was a significant improvement in the TTR. The TTR improved to 80.46 ± 16.51 (p < 0.001), indicating a statistically significant increase. Moreover, there was a significant increase in the proportion of patients with a TTR of 65% or more. This proportion rose from 47 to 88% (p < 0.001). These improvements are detailed in Table 4 and illustrated in Figs. 1, 2, 3.

Table 4.

Change of TTR after 6 and 12 months of protocol implementation compared between patients with TTR ≥ 65% and patients with TTR < 65%

| TTR | Before protocol | After protocol 6 months | After protocol 12 months | P-value1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TTR (Mean ± SD) % | 64.69 ± 20.14 | 70.08 ± 17.20 | 80.46 ± 16.51 | < 0.001 |

| TTR (Median) % | 62.78 | 71.20 | 79.40 | < 0.001 |

| Group 1: TTR < 65%, n (%) | 30 (52.63) | 24 (42.11) | 7 (12.28) | < 0.001 |

| Group 2: TTR ≥ 65%, n (%) | 27 (47.37) | 33 (57.89) | 50 (87.72) | < 0.001 |

1P-value for comparison between patients with TTR ≥ 65% and TTR < 65%

Significant values are in bold.

Figure 1.

Individual change of TTR before and after 12 months of protocol implementation in 57 patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation received warfarin.

Figure 2.

Individual change of TTR before and after 6 and 12 months of protocol implementation in 57 patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation received warfarin.

Figure 3.

Change of TTR before and after 6 and 12 months of protocol implementation in 57 patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation received warfarin.

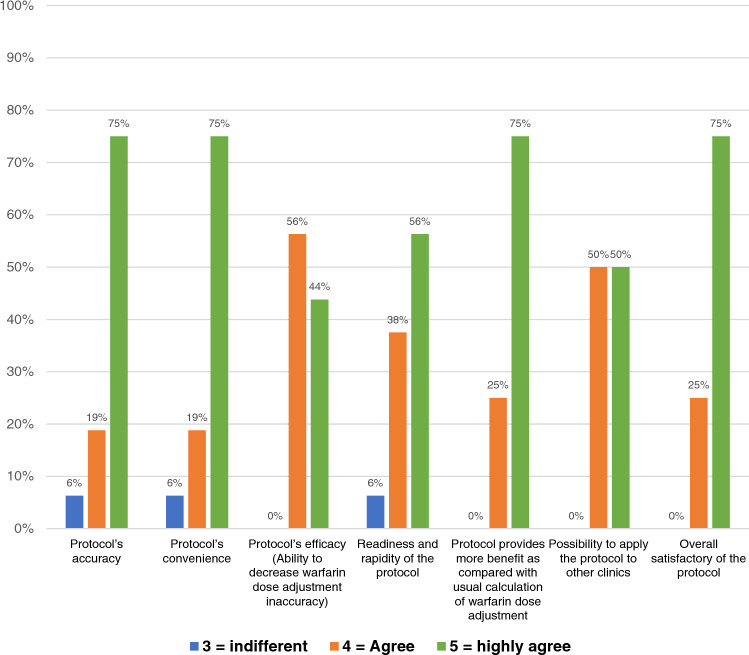

Secondary outcomes

During the follow-up period, there were three recorded mortalities. Importantly, no ischemic or major bleeding events occurred in the first 12 months. For patients with a persistently low TTR of less than 55% despite adjustments to the protocol, a switch was made from VKAs to NOACs. This switch was made for ten patients. Only one patient was excluded due to a violation of the protocol. The feasibility of the protocol was assessed through a questionnaire. The responses indicated high levels of satisfaction and provided suggestions for improvement. These details are outlined in the manuscript and can be seen in Fig. 4 and Supplementary Appendix Table S6.

Figure 4.

Bar chart showing satisfactory using TTR-INR guided warfarin adjustment protocol in patients with atrial fibrillation receiving vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant.

Discussion

This study evaluated the effectiveness of a protocol for adjusting warfarin dosage. The protocol, guided by TTR and INR, was derived from the Hamilton Dosing Nomogram and Thai guidelines for patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF). After implementing the protocol for 12 months, the average TTR significantly increased from 65 to 80% (p < 0.001). Furthermore, the number of patients with a TTR of 65% or higher rose from 27 (47%) to 50 (88%) (p < 0.001), demonstrating the protocol’s effectiveness. Despite two rounds of warfarin adjustments according to the protocol, ten patients consistently had low TTR levels (below 65%). As a result, they were switched from VKA to NOACs due to their inability to reach the target INR and TTR levels (≥ 65%). This decision highlights the physicians’ meticulous approach to managing patients on warfarin therapy, as evidenced by regular assessments of INR and TTR levels at each visit. In addition, three patients were transitioned to NOACs due to difficulties in monitoring INR levels. Only one patient was excluded from the study due to a protocol violation, suggesting that the TTR-INR guided warfarin adjustment protocol is feasible and easy to use for most physicians. This is further supported by questionnaire responses, where the majority of participants either agreed or strongly agreed with items assessing the protocol’s feasibility.

Before the implementation of our protocol, only about 55% of patients achieved a TTR of 65% or higher. This aligns with a meta-analysis by Baker and colleagues, which highlighted the challenge of controlling INR levels among warfarin-receiving patients in the USA. Their study revealed that only 55% of AF patients in the USA maintained INR within the target range10. Similar trends were observed in Thailand. A study at Samutprakarn General Hospital11 involving 132 warfarin patients showed that only 22% achieved the target INR range of 2.0–3.0. Another study at Songklanagarind University Hospital found that only 32% of patients reached the target INR. Additional studies by Saokaew et al12,13. also showed varying TTR among AF patients in warfarin clinics, ranging from 31 to 56%.

Our study demonstrated a 15% increase in TTR after implementing the TTR-INR guided warfarin adjustment protocol for 12 months. However, clinical outcomes were not observed, possibly due to the short follow-up duration. Despite this, our findings support the recommendations from previous studies by Rosendaal et al.14, Witt et al.15, and Young et al.16, which advocated for systematic monitoring and adjustment of warfarin using protocols to improve TTR, clinical outcomes, and reduce complications.

During the follow-up, three deaths due to severe acute pancreatitis and sepsis were recorded. However, no treatment-related ischemic or significant bleeding events were observed in the initial 12 months, suggesting a favorable safety profile. This is consistent with a systematic review by Wan et al.9, which found that TTR could serve as a predictor of UAEs. A retrospective analysis of 21,540 patients revealed that a 7% increase in TTR was associated with a reduction in severe bleeding complications, while a 22% increase in TTR correlated with a decrease in ischemic events. Some clinical trials9 reported that every 10% increase in algorithm-consistent dosing of warfarin led to a 6.12% increase in TTR, accompanied by an 8% reduction in both ischemic stroke and severe bleeding complications.

Study strength

Our study is a prospective study that utilizes a protocol-based approach for adjusting the warfarin dosage in patients with NVAF who are on warfarin as an anticoagulant. While TTR is a standard of care for patients with AF taking warfarin, its implementation is not widespread in Thailand. Notably, there was no prior study in Thailand that demonstrated the efficacy of using the Warfarin Dosing Nomogram, a TTR-INR guided warfarin adjustment protocol. As shown in numerous studies, algorithm-consistent dosing was effective, helped decrease human error in calculation, and was easy to use. The results of our study underscore the future use of protocol-based dose adjustment in Thailand, that potentially enhance the management of patients on warfarin therapy, improving their health outcomes and quality of life.

Limitations

This study was a non-randomized, single-center investigation that collected data from patients at the Warfarin Clinic at King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital. The clinic staff, comprised of cardiologists, pharmacists, and nurses, were accustomed to warfarin and experienced in patient education about the drug. This expertise may have contributed to a higher baseline TTR compared to other studies from different centers or clinics.

The COVID-19 pandemic temporarily closed the clinic, which reopened in June 2021. This closure delayed patient recruitment and the calculation of the 12-month TTR. Further results are expected upon the study’s completion.

The pandemic also led to some patients being lost to follow-up or having to postpone scheduled visits with physicians. This may have introduced errors in the TTR calculation. Moreover, the study population did not meet the previously calculated sample size of 93 participants; instead, a total of 57 patients were analyzed for the primary outcome. Despite this, the data still showed a significantly large effect size in the improvement of TTR following the protocol implementation. This suggests the certainty of the results, even though the number of enrolled participants did not meet the previously calculated number.

Future research

In order to gather more precise data and better reflect the real practice in Thailand, a prospective multicenter study of a similar design could be beneficial. This would allow for a larger and more diverse patient population from both the warfarin clinic and other clinics. Additionally, a longer follow-up period might provide more comprehensive data to elucidate clinical outcomes. This approach could potentially offer a more robust understanding of the effectiveness of the TTR-INR guided warfarin adjustment protocol in a real-world setting.

Conclusion

This study provides valuable insights into the effectiveness and feasibility of a TTR-INR guided warfarin adjustment protocol in patients with NVAF. The implementation of this protocol resulted in substantial enhancements in TTR levels and the control of anticoagulation, without any observed complications related to the treatment during the first 12 months of follow-up. To confirm these findings and evaluate the impact of the protocol on clinical outcomes, further research involving larger patient groups and extended follow-up periods is recommended.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We thank Chonlada Phathong for her assistance in designed study and statistical analysis.

Author contributions

P.K. designed the study, recruited the patients, acquired, analyzed, and interpreted the data, and drafted the article; N.S. recruited the patients, acquired, analyzed, and interpreted the data; K.N., W.L., and W.S. interpreted the data and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content, K.T., R.A., and A.S. acquired the data, V.R. designed the study, analyzed, and interpreted the data, and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content; All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported in part by the Ratchadapiseksompotch Fund (2021), Chulalongkorn University (Grant No. RA 64/025).

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Paisit Kosum and Noppachai Siranart.

Contributor Information

Noppachai Siranart, Email: siranartnoppachai@gmail.com.

Voravut Rungpradubvong, Email: voravut.r@chula.ac.th.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-61664-5.

References

- 1.Haissaguerre M, Jais P, Shah DC, Takahashi A, Hochini M, Quiniou G, et al. Spontaneous initiation of atrial fibrillation by ectopic beats originating in the pulmonary vein. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998;339:659–666. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199809033391003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perez-Lugones A, Mcmahon JT, Ratliff NB, Saliba WI, Schweikert RA, Marrouche NF, et al. Evidence of specialized conduction cells in human pulmonary veins of patients with atrial fibrillation. J. Cardiovasc. Elecgtrophysiol. 2003;14:803–809. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2003.03075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen YJ, Chen YC, Wongcharoen W, Lin CI, Chen EA. Effect of k201, a novel antiarrhythmic drug on calcium handling and arrhythmogenic activity of pulmonary vein cardiomyocytes. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2008;153:915–925. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee SH, Chen YC, Chen YJ, Chang SL, Tai CT, Wongcharoen W, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha alters calcium handling and increases arrthymogenesis of pulmonary vein cardiomyocytes. Life Sci. 2007;80:1806–1815. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2007.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruff CT, Guiglinao RP, Braunwald E, Hoffman EB, Deenadayalu N, Ezekowitz MD, et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safe ty of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. A meta-analysis of randomized trials. Lancet. 2014;383:955–962. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62343-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hindrick G, Potpara T, Dagres N, Arbelo E, Bax JJ, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, et al. ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) Eur. Heart J. 2020;2020(00):1–125. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosendaal FR, Cannegieter SC, Meer FJ, Briet E. A method to determine the optimal intensity of oral anticoagulant therapy. Thromb. Haemost. 1993;69:236–239. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1651587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morgan CL, McEwan P, Tukiendorf A, Robinson PA, Clemens A, Plumb JM. Warfarin treatment in patients with atrial fibrillation: Observing outcomes associated with varying levels of INR control. Thromb. Res. 2009;124:37–41. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2008.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wan Y, Heneghan C, Perera R, Roberts N, Hollowell J, Glasziou P, et al. Anticoagulation control and prediction of adverse events in patients with atrial fibrillation: A systematic review. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes. 2008;1:84–91. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.796185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baker WL, Cios DA, Sander SD, Coleman CI. Meta-analysis to assess the quality of warfarin control in atrial fibrillation patients in the united states. JMCP. 2009;15(3):244–252. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2009.15.3.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lekjaoren S. Outcome of suggestion of pharmacist in patient with receiving warfarin at Samut Prakan Hospital (abstract), 2010. Thesis of Master of Science in Pharmacy Program in Clinical Pharmacy. Chulalongkorn University

- 12.Saokaew S, Sapoo U, Nathisuwan S, Chaiyakunapruk N, Permsuwan U. Anticoagulation control of pharmacist-managed collaborative care versus usual care in Thailand. Int. J. Clin. Pharmacy. 2012;34(1):105–112. doi: 10.1007/s11096-011-9597-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, Eikelboom J, Oldgren J, Parekh A, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. New Engl. J. Med. 2009;361(12):1139–1151. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosendaal FR, Cannegieter SC, van der Meer FJ, Briët E. A method to determine the optimal intensity of oral anticoagulant therapy. Thromb. Haemost.. 1993;69(3):236–239. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1651587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Witt DM, Sadler MA, Shanahan RL, Mazzoli G, Tillman DJ. Effect of a centralized clinical pharmacy anticoagulation service on the outcomes of anticoagulation therapy. Chest. 2005;127(5):1515–1522. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.5.1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Young S, Bishop L, Twells L, Dillon C, Hawboldt J, O’shea P. Comparison of pharmacist managed anticoagulation with usual medical care in a family medicine clinic. BMC Fam. Pract. 2011;12:88. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-12-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.