Version Changes

Revised. Amendments from Version 1

On behalf of the authors, I am delighted to express my gratitude to the reviewers and editors of the Open Research Africa Journal. Indeed, the revised version of our manuscript has been greatly improved after considering all the suggestions and comments. The authors were asked to state the additional advantages of the CT-IMRS PCR assay as compared to conventional PCR techniques and the adverse clinical outcomes of Chlamydia trachomatis infection in women. The authors included advantages of the CT-IMRS (Refer to the introduction section). Also, the overall turn-around time of the CT-IMRS was mentioned. The authors were also asked to describe the specific treatment that the participant who were recruited into the study were given. Treatment regimens for the participant was included in the revised version of the manuscript (method section). The clinical samples that were used to validate the CT-IMRS assay were mentioned in the result section of the revised manuscript. The authors were also requested to rephrase figure captions for clarity. No new Figures or Tables have been added to the new version. The authors have also included the specificity and sensitivity of the CT-IMRS assay. The expected band sizes for the CT-IMRS primers have also been stated as suggested by the reviewers. The authors were also asked to mention the major limitation of the study. This section has been included. Some more edits have also been addressed appropriately.

Abstract

Chlamydia trachomatis ( C. trachomatis) is a common sexually transmitted infection (STI). In 2019, the World Health Organization reported about 131 million infections. The majority of infected patients are asymptomatic with cases remaining undetected. It is likely that missed C. trachomatis infections contribute to preventable adverse health outcomes in women and children. Consequently, there is an urgent need of developing efficient diagnostic methods. In this study, genome-mining approaches to identify identical multi-repeat sequences (IMRS) distributed throughout the C. trachomatis genome were used to design a primer pair that would target regions in the genome. Genomic DNA was 10-fold serially diluted (100pg/μL to 1×10 -3pg/μL) and used as DNA template for PCR reactions. The gold standard PCR using 16S rRNA primers was also run as a comparative test, and products were resolved on agarose gel. The novel assay, C. trachomatis IMRS-PCR, had an analytical sensitivity of 4.31 pg/µL, representing better sensitivity compared with 16S rRNA PCR (9.5 fg/µL). Our experimental data demonstrate the successful development of lateral flow and isothermal assays for detecting C. trachomatis DNA with potential use in field settings. There is a potential to implement this concept in miniaturized, isothermal, microfluidic platforms, and laboratory-on-a-chip diagnostic devices for reliable point-of-care testing.

Keywords: Identical Multi-Repeat Sequences, Chlamydia trachomatis, Isothermal assays

Introduction

Chlamydia trachomatis ( C. trachomatis) is among the most common sexually transmitted infections (STIs) that lead to adverse birth and neonatal outcomes such as pre-term labor and low birth weight infants 1 . It is, therefore, most likely that undiagnosed maternal C. trachomatis infections may lead to unavoidable adverse health outcomes in women and children worldwide, for example, salpingitis, endometritis, tubo-ovarian abscesses, pelvic peritonitis, blocked fallopian tubes and perihepatitis 2 . During delivery, the risk of mother-to-child transmission of C. trachomatis increases 3 . Most patients with C. trachomatis infections are asymptomatic, and these cases remain undetected and untreated, further complicating the management of infected cases in most countries 4 . In 2019 the World Health Organization (WHO) reported about 131 million infections of C. trachomatis globally 5 .

Traditional methods of C. trachomatis testing include cervical cytological examination using Papanicolaou (Pap) smears 6 . However, these techniques have many challenges, such as technical difficulties during cultures, labor intensiveness, increased turnaround time, and high cost. C. trachomatis infections are diagnosed by indirect and direct methods 7 .

Direct methods detect the presence of C. trachomatis in localized infections 7 . These methods include culture, antigen tests (Enzyme Immuno Assays (EIA), Direct Fluorescent Antibody (DFA) tests, immune chromatographic tests, Rapid Detection Tests (RDTs), and Nucleic Acid Amplification Tests (NAATs)) 7 . Indirect methods are specific to C. trachomatis antibodies and are used for diagnostic evaluation of chronic or invasive infection (Pelvic Inflammatory Disease and lymphogranuloma venereum) and post-infectious complications, like sexually acquired reactive arthritis (SARA) 7 .

Direct detection methods, such as NAATs, have several advantages. They use polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and use fluorescent-labeled probes to identify amplification products in real-time, and these reduce the turn-around time 8 . Studies have also shown that C. trachomatis PCR using DNA extracted from conjunctival swabs can achieve a detection limit of up to 100 plasmid copies 9 .

Other NAATs, such as ligase chain reaction and transcription mediated amplification, are also specific and sensitive in the screening of C. trachomatis in patient samples 10 . Results of these tests can be generated in a few hours when coupled with automated nucleic acid extraction techniques.

However, NAATs such as the Abbot Real-Time CT/NG requires stringent sample transport and storage conditions 11 . For example, to achieve accurate and reliable results, samples from asymptomatic women must be stored between 2°C and 30°C and processed within 14 days after collection 11 . Symptomatic women's specimens must be thawed, frozen, and stored at the same temperature range 11 . These conditions may be challenging, mainly in resource-limited countries where refrigeration facilities are unavailable, especially during specimen collection and transport 12 .

When compared to C. trachomatis culture, the DFA has a sensitivity of between 95–100% 13 . However, DFA involves labor-intensive microscopic examination of individual stained specimens, which can be time-consuming when dealing with many samples 13 . Also, highly skilled and experienced personnel perform routine microscopic examinations 13 . By contrast, EIAs are suitable for testing of many samples and have sensitivities of 90% as compared to culture, however, they are less accurate than DFA and test results may be false positive 13 .

Thriving C. trachomatis culture is dependent on isolated live organisms, and cases identified in clinical samples ranges between 60–80%. In addition, culture sensitivity can be affected by improper specimen sample collection, and transport, storage, toxic material in patient samples, and colonization of cell cultures by opportunistic microorganisms 14 . C. trachomatis culture has prolonged turn-around time; it is labor intensive, and different laboratories have various standardization protocols 14 .

Indirect methods used for the identification of C. trachomatis are inaccurate in identifying acute infections of the lower reproductive and digestive tract; this is because antibody responses become detected after several weeks to months after an initial infection 14 .

Enzyme linked immuno-sorbent assays that detect bacterial lipopolysaccharide may cross-react with other gram negative bacteria, which may give false-positive results. The C. trachomatis antibody response may be absent or delayed in some patients, which makes many serological tests inaccurate 15 . In addition, most of the C. trachomatis infections are asymptomatic and are diagnosed late, resulting in uninterrupted transmission 16 . To manage asymptomatic C. trachomatis infections, there is an urgent need to develop efficient methods of diagnosis with appropriate specificity and sensitivity that can be incorporated as part of routine screening programs, can be used to identify new infections and prevent the transmission of C. trachomatis cases 17 . In this study, we have developed a highly sensitive molecular method that uses de novo genome mining approaches to detect identical multi-repeat sequences (IMRS) in C. trachomatis bacterial genome to be used as both isothermal amplification and PCR assays. The assay has a potential for field deployability due to inherent high sensitivity.

Methods

Identical Multi-Repeat Sequence (IMRS) genome-mining

The primers used in this study were developed using Identical Multi-Repeat Sequence (IMRS) genome mining algorithm. The IMRS algorithm was designed by using the Java Collection Framework by plugging in Google Guava version 23.0-jre (open-source common libraries for Java; https://github.com/google/guava, last accessed September 1, 2018). In the C. trachomatis IMRS application, the algorithm performs an analysis of the genome to select similar repeating oligonucleotide sequences of various lengths. The algorithm fragments the C. trachomatis genome into cross-matching windows of size L and enumerates all fragmented L-mer sequences into a list along with their corresponding positional coordinates on the genome. The repeated L-mers are determined with their exact positions categorized and classified on the basis of the repeat count. The hit counts are then screened by calculating coordinates for a pair of repeat sequences that are next to each other on the Chlamydia trachomatis genome and within an amplifiable region for primer generation. The NIH’s Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST; NIH, Bethesda, MD; https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi, last accessed July 11, 2019) and the National Center for Biotechnology Information’s Primer-BLAST (NCBI, Bethesda, MD; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast, last accessed July 11, 2019) evaluated the specificity of lead pairs and the best pair was then identified. To identify C. trachomatis IMRS primers, C. trachomatis genome was used as an input for IMRS algorithm; and the primer pair having maximum number of repeats was selected for assay design. BLAST analyses were then performed to ensure that the selected primer pair is specific only for Chlamydia trachomatis 18 . The C. trachomatis genome (NCBI, NC_000117.1) was used as a standard to mine repetitive sequences of less than 30 bases that can serve as reverse or forward primers. The Basic Local Alignment Search Tool available from the NIH website was used to determine the primer sets to ascertain C. trachomatis specificity. The resulting primers were predicted to amplify 6 fragment sizes of DNA derived from different regions of the C. trachomatis genome as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. IMRS Primer target regions on the Chlamydia trachomatis bacterial genome.

IMRS, identical multi-repeat sequences.

| No. | Amplification

regions |

Expected sequence

fragment |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 531375 - 531511 | 137bp |

| 2 | 531375 - 531661 | 287bp |

| 3 | 531375 - 531814 | 440bp |

| 4 | 531525 - 531661 | 137bp |

| 5 | 531525 - 531814 | 290bp |

| 6 | 531675 - 531814 | 140bp |

Distribution of primer targets on the C. trachomatis genome was determined by the Circos plot version 0.69–9 (Circos; RRID:SCR_011798).

C. trachomatis genomic DNA preparation

C. trachomatis DNA was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) (ATCC ® VR-885D ™, LOT Number. 70013611) (Manassas, Virginia, USA) at an initial concentration of ≥1 × 10 5 genome copies/μL. The original DNA stock concentration was diluted to 100 pg/μL (8.92 × 10 4 copies/μL) and eventually diluted 100 fold and 10 fold in Tris EDTA buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) for the respective PCR assays.

16S rRNA PCR

The 16S rRNA PCR assays were performed in a SimpliAmp Thermal Cycler (Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) in a 25 μL reaction volume composed of dNTPs (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) (0.2mM), forward (TCCGGAGCGAGTTACGAAGA) and reverse (AATCAATGCCCGGGATTGGT) primers (0.01 mM each) (Macrogen, Seoul, South Korea), Taq Hot-Start DNA polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) (1.25 U), and 1 μL C. trachomatis DNA. The thermocycling parameters were as indicated: 95°C for 3 min; 40 cycles of: 95°C for 30 s, 56°C for 30 s, 72°C for 30 s; and 72°C for 5 min and a final hold step of 4°C 19 . All PCR amplicons were resolved in 1% agarose gel and visualized on a UV Gel illuminator machine (Fison Instruments, Glasgow, United Kingdom) under ethidium bromide (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts, USA) staining 19 .

C. trachomatis IMRS PCR

The C. trachomatis IMRS assays were carried out in a SimpliAmp Thermal Cycler (Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) in a 25 μL reaction volume consisting of dNTPs (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts, USA) (0.2 mM), forward (TGCTGCTGCTGATTACGAGCCGA) and reverse (TGTAGGAGGAGCCTCTTAGAGAA) primers (0.01 mM) (Jigsaw Biosolutions, Bengaluru, India), Taq Hot-Start DNA polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts, USA) (1.25 U) and 1 μL C. trachomatis DNA. The thermocycling parameters for C. trachomatis-IMRS PCR assay was as indicated: 95°C for 3 min; 40 cycles of: 95°C for 30 s, 50°C for 30 s, 72°C for 30 s; and 72°C for 5 min and a final hold of 4°C. All PCR amplicons were resolved in 1% agarose gel and visualized on a UV Gel illuminator machine (Fison Instruments, Glasgow, United Kingdom) under ethidium bromide (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts, USA) staining 19 .

Isothermal IMRS amplification

The Isothermal IMRS amplification was done in a reaction volume of 25 μL composed of the following Bst 2.0 polymerase (640 U/mL) (New England Biolabs, Massachusetts, USA), with 1X amplification buffer, 1.6 μM reverse primer (TGTAGGAGGAGCCTCTTAGAGAA), and 3.2 μM forward primer (TGCTGCTGCTGATTACGAGCCGA) (Jigsaw Biosolutions, Bengaluru, India) with 10 mM dNTPs (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts, USA), 0.4 M Betaine (Sigma-Aldrich, Missouri, USA), molecular-grade water and Ficoll (0.4 g/mL) (Sigma-Aldrich, Missouri, USA). Amplification was performed at 56°C for 40 min. PCR amplicons were resolved in 1% agarose gel and visualized on a UV Gel illuminator machine (Fison Instruments, Glasgow, United Kingdom) under ethidium bromide (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts, USA) staining 19 .

Lower limit of detection

To determine the lower limit of detection (LLOD), DNA template was diluted 100-fold from 100 pg/μL (8.92 × 10 4 copies/μL) to 10 -6 pg/μL (<1 copies/μL) and 10-fold from 100 pg/μL (8.92 × 10 4 copies/μL) to 10 -2 pg/μL (< 1 copies/μL) for the C. trachomatis IMRS PCR and gold standard 16S rRNA PCR, respectively. Five replicates of each dilution were then used for the PCR assays. PCR amplicons were resolved in 1% agarose gel and visualized on a UV Gel illuminator machine (Fison Instruments, Glasgow, United Kingdom) under ethidium bromide staining. To calculate the LLOD of the 16S rRNA and IMRS C. trachomatis PCR, probit analysis was done by determining the ratio of reactions that were successful to the total number of reactions performed. Similarly, to assess the LLOD for the C. trachomatis Isothermal IMRS PCR assay, genomic DNA was diluted 10-fold from a starting concentration of 1.64 × 10 6 copies/μL. Thereafter, the LLOD was calculated as mentioned earlier 19 .

C. trachomatis-Lateral Flow Assay

To produce a visual read-out signal of amplified products, the C. trachomatis-Lateral Flow Assay ( C. trachomatis-LFA) was performed as follows in a final master mix volume of 25 μL, 2.5 μL annealing buffer, dNTPs and NaCl (1.75 μL), MgSO 4 (1.2 μL), NG 5’ biotinylated forward primer (Biotin 5'-“TGCTGCTGCTGATTACGAGCCGA”-3'), C. trachomatis Reverse primer, C. trachomatis 3’ FAM labelled probe (CCACCAATACTCTC/-FAM-3’), C. trachomatis Digotexin labelled probe, Ficoll 400 (6.25 μL), internal control sequence (2.5 μL), ISO Amp III enzyme mix 2.0 μL, C. trachomatis DNA 5μL and molecular grade water 1.45 μL. The LFA strip (Milenia Biotec GmbH, Giessen, Germany) were incubated at 65°C for 1 hour, thereafter, 5 μL of reaction liquid was added to the LFA strip and 2 drops of buffer added 19 .

Real-time PCR assay

Real-Time PCR assay was performed on the QuantStudio™ 5 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) as a comparative method 20 for determining the sensitivity of the C. trachomatis IMRS and 16S rRNA PCR primers for detecting C. trachomatis DNA. The genomic DNA was serially diluted 10-fold starting concentration of 10 4 genome copies/μL. The PCR was done in triplicate in a final master mix volume of 10 μL and was composed of the following: 1 μL reverse and forward IMRS primer mix, 5 μL SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (Thermo fisher, Massachusetts, USA), 2.5 μL C. trachomatis DNA and 1.5 μL molecular grade water. The thermocycling conditions were 50°C for 2 min; 95°C for 10 min; 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 30 s.

Confirmation of C. trachomatis-IMRS amplicons using gene cloning

Specificity C. trachomatis-IMRS primers was also confirmed using gene cloning. Amplification of Chlamydia trachomatis gDNA was done using Assembly IMRS-F (ttccggatggctcgagtttttcagcaagattgcctgcc TGCTGATTACGAGCCGA ) and Assembly IMRS-R (agaatattgtaggagatcttctagaaagatt GTAGGAGGAGCCTCTTAGAGAA ) primer set. The bold and underlined sequences represent the IMRS primers specific for the C. trachomatis genome whereas the non-priming overlap lowercase sequence at the 5 ´-end of the primers sequence corresponds to the homologous sequences in the vector used for cloning. The PCR products were resolved on 2% agarose to ascertain the size of the fragment and thereafter the PureLink™ PCR purification kit (ThermoFisher) was used for purification. The NEBuilder® HiFi DNA Assembly kit (NEB) was used to ligate the PCR products into pJET1.2 blunt vector (ThermoFisher) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The NEBuilder HiFi DNA Assembly product obtained was further transformed into NEB 5-alpha Competent E. coli (NEB #C2987, NEB) following the manufacturer’s recommendations. Colonies that were transformed were selected randomly, DNA extraction and Sanger-sequencing done using the universal pJET1.2 forward sequencing primer (cgactcactatagggagagcggc) and pJET1.2 reverse sequencing primer (aagaacatcgattttccatggcag). The nucleotides obtained were trimmed and assessed using SnapGene sequence analysis software (Version 6.1 GSL Biotech; available at snapgene.com, RRID:SCR_015052), alignment performed to determine similarity and or clonal differences and BLAST used assess for similarity with the C. trachomatis genomic sequences.

Clinical samples

Vaginal swab samples collected from a cohort of women aged between 19 – 49 years participating in an STI study in Nairobi County at the Kenyatta National Hospital (KNH) in 2022 were used to validate the Chlamydia trachomatis IMRS PCR method. Enrolled participants provided written informed consent. This study was approved by the KNH Ethics Review Committee on the 13 th of April 2022 (P928/12/2021). The C. trachomatis-16S rRNA PCR method was used to screen for C. trachomatis cases. Thereafter, positive clinical samples were used to validate the C. trachomatis-IMRS primers. Participants were notified of results directly and confidentially by study staff, and were treated for C. trachomatis infection. Patients with persistent symptoms were referred to a molecular laboratory for testing. The following drugs were used, Ceftriaxone, Azithromycin, and Doxycycline. The Mount Kenya University Ethical Review Committee (MKU/ERC/1649) approved the study and use of clinical samples on the 23 rd of October 2020.

Data analysis

The mean, and SD values calculation, and graphs were done using Microsoft Excel (RRID:SCR_016137) 2016. Probit regression analyses and calculation of the LLOD of C. trachomatis-IMRS and C. trachomatis-16S rRNA PCR assays (the concentration at which Chlamydia trachomatis DNA is determined with 95% confidence), was done in Excel 2016. Trichomonas vaginalis and Treponema pallidum DNA were used to confirm the specificity of the C. trachomatis-IMRS primers for other related infections. Analyses were done using paired t-test for two-tailed distribution. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Development and IMRS primer distribution targets on Chlamydia trachomatis genome

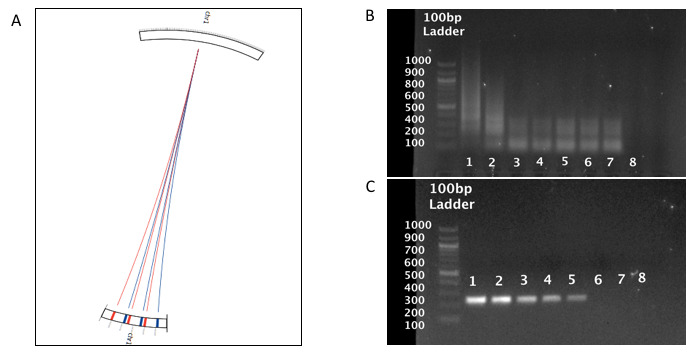

Using the IMRS-based genome mining algorithm 10 , six repeat sequences ( Table 1) 19, 21 were identified on the Chlamydia trachomatis genome, which could serve as reverse and forward primers for the PCR assay. The primers (F 5’- TGCTGCTGCTGATTACGAGCCGA -3’ and R 5’- TGTAGGAGGAGCCTCTTAGAGAA - 3’), as were depicted using a Circos plot version 0.69–9 (Circos; RRID:SCR_011798) ( Figure 1), are present at a number of loci allowing them to serve interchangeably as reverse or forward primers.

Figure 1. Chlamydia trachomatis-IMRS primer targets and gel images from the C. trachomatis IMRS and conventional 16S rRNA PCR assay.

( A) Circos plot for the distribution of identical multi repeat sequence (IMRS) primers in the C. trachomatis genome. C. trachomatis IMRS primer A (blue lines) IMRS primer B (red lines) both have 6 repeats. ( B) and ( C) Gel image of 10-fold serially diluted (1 – 100, 2 – 10, 3 – 1, 4 – 0.1, 5 – 0.01, 6 – 0.01, 7 – 0.001 and 8 - NTC) (pg/μl) genomic C. trachomatis DNA amplicons resolved on 1% gel using IMRS primers and gold standard 16S rRNA PCR primers, respectively.

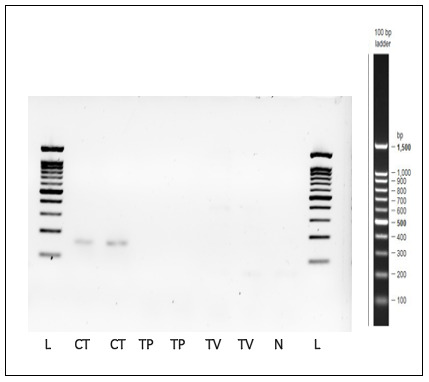

Specificity of C. trachomatis identical multi-repeat primers

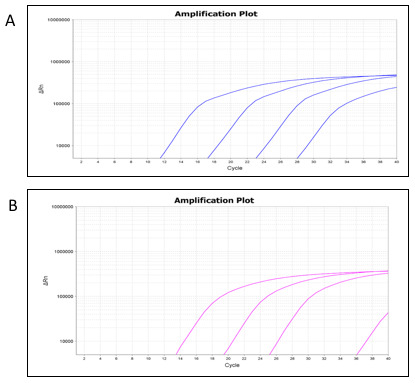

To confirm specificity of the IMRS primers for regions on the C. trachomatis genome, serially diluted DNA was used as template for PCR amplification. The IMRS primers amplified C. trachomatis DNA at a starting template concentration of 0.1 fg/μL ( Figure 1B), and the gold standard 16S rRNA primers ( Figure 1C) detected C. trachomatis DNA to a concentration of 10 fg/μL. This shows that the IMRS-PCR assay has a 100-fold higher sensitivity compared to the conventional 16S rRNA PCR assay. Diluted C. trachomatis DNA was used as a template for real-time PCR amplification using C. trachomatis-IMRS primers ( Table 2A), and conventional C. trachomatis-16S rRNA primers ( Table 2B). Amplification curves were plotted using the mean Ct values at each respective dilution ( Figure 2A, C. trachomatis-IMRS primers and Figure 2B, C. trachomatis-16S rRNA primers).

Figure 2.

Real-time PCR amplification plots from the Chlamydia trachomatis-identical multi repeat sequence (IMRS) ( A) and the 16S rRNA ( B) assays using serially diluted C. trachomatis genomic DNA.

Table 2. Genomic DNA dilution to determine the sensitivity of the C. trachomatis-IMRS primers using Real time PCR.

IMRS, identical multi-repeat sequences.

| A, Serially diluted

Chlamydia trachomatis

genomic DNA served as amplification templates for the C. trachomatis-IMRS primers | ||

|---|---|---|

| Concn of DNA (genome

copies/ µl) |

Ct value | STD.DEV |

| 1×10 4 | 12.298 | 0.541 |

| 1×10 3 | 17.674 | 1.244 |

| 1×10 2 | 23.639 | 0.349 |

| 1×10 1 | 28.265 | 0.275 |

| B, Serially diluted

Chlamydia trachomatis

genomic DNA served as amplification templates for the 16S rRNA primers | ||

| Concentration of DNA

(genome copies/ µl) |

Ct value | STD.DEV |

| 1×10 4 | 14.64 | 0.902 |

| 1×10 3 | 20.584 | 1.599 |

| 1×10 2 | 26.607 | 1.056 |

| 1×10 1 | 36.527 | 0.249 |

Determination of the Lower Limit of Detection (LLOD)

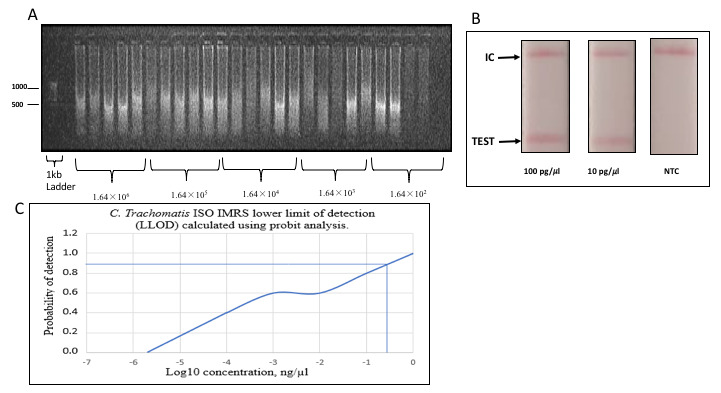

To calculate the lower limit of detection (LLOD) of the IMRS PCR and the conventional 16S rRNA PCR, probit statistic was calculated using concentrations of 100 and 10 fold serially diluted C. trachomatis DNA and thereafter the dilutions served as starting template for the C. trachomatis-IMRS and 16S RNA PCR respectively ( Table 3A and Table 3B). The probit plots for the C. trachomatis-IMRS PCR and the gold standard 16S rRNA PCR assay are shown in Figure 3A and Figure 3B. The concentration at which C. trachomatis DNA can be estimated with 95% confidence was used to calculate the LLOD. Probit calculation for the C. trachomatis-IMRS PCR, had a coefficient of χ = -3.6494 and a P-value of 0.7043 ( Table 4). As shown, the C. trachomatis IMRS primers had a detection limit of 9.5 fg/μL ( Figure 3A). The probit calculation for the 16S rRNA PCR is shown in Table 4, and had a coefficient of χ = -7.2101 and a P-value of 0.9978. The 16S rRNA PCR assay for C. trachomatis had an LLOD of 4.31 pg/μL ( Figure 3B). In summary, the C. trachomatis-IMRS PCR assay was more sensitive than the gold standard 16S rRNA PCR assay.

Figure 3. Probit regression analysis to estimate the lower limit of detection for the Chlamydia trachomatis-identical multi repeat sequence (IMRS) primers and the 16S rRNA PCR.

Probit analysis estimation for C. trachomatis-IMRS ( A). As indicated, the IMRS primers for C. trachomatis had an LLOD = 9.5 fg/μl. B: Probit analysis estimation for 16S rRNA PCR. As indicated, gold standard primers for C. trachomatis had an LLOD = 4.31 pg/μl.

Table 3. Chlamydia trachomatis genomic DNA was serially diluted 100 folds (A) and 10-folds (B) and used as template for the C. trachomatis-IMRS and 16S rRNA PCR to estimate the lower limit of detection.

| A, 100-fold dilution | |

|---|---|

| Serial dilutions (pg/μl) | Replicates (5) |

| 100 | 5/5 |

| 1 | 5/5 |

| 0.01 | 4/5 |

| 0.0001 | 5/5 |

| 0.000001 | 0/5 |

| 0.00000001 | 0/5 |

| B, 10-fold dilution | |

| Serial dilutions (pg/μl) | Replicates (5) |

| 100 | 5/5 |

| 10 | 4/5 |

| 1 | 3/5 |

| 0.1 | 1/5 |

| 0.01 | 1/5 |

| 0.001 | 0/5 |

Table 4. Shows the statistics obtained from the Probit analysis.

IMRS, identical multi-repeat sequences.

| Assay | χ Coefficient | P-Value |

|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA | -7.2101 | 0.9978 |

| IMRS | -3.6494 | 0.7043 |

Genomic Chlamydia trachomatis DNA amplification using the Isothermal assay

Serially diluted genomic DNA was used to perform the Isothermal- C. trachomatis-IMRS amplification and the resulting reaction products visualized on a 1% gel ( Figure 4A). The Isothermal- C. trachomatis-IMRS assay successfully amplified C. trachomatis DNA down to 1.64×10 2 genome copies/μL. The LLOD for the C. trachomatis-Iso-IMRS assay was estimated at 0.3162 ng/μL ( Figure 4C).

Figure 4. Chlamydia trachomatis-Iso-identical multi repeat sequence (IMRS), lateral flow assay and estimation of the lower limit of detection of the isothermal assay.

( A) Gel image of C. trachomatis-Iso IMRS assay products visualized on 1% gel. Five replicates of each dilution served as DNA template for the C. trachomatis-Iso IMRS. DNA concentration is in genome copies per μl. ( B) Visual read-out detection of serially diluted C. trachomatis DNA using the lateral flow assay. Amplicons were incubated at 65°C for 1 hour and transferred onto strips as indicated. IC – Internal Control, NTC – Non Template Control. ( C) Probit analysis estimation for C. trachomatis Iso-IMRS. As indicated, the IMRS primers for C. trachomatis had an LL0D = 0.3162 ng/μl.

Chlamydia trachomatis Lateral Flow Assay

A visual readout signal was observed when serially diluted DNA was transferred on lateral flow assay (LFA) strips ( Figure 4B). The LFA readout of the amplification products was successful indicating the potential and applicability of the Isothermal-IMRS assay in the field.

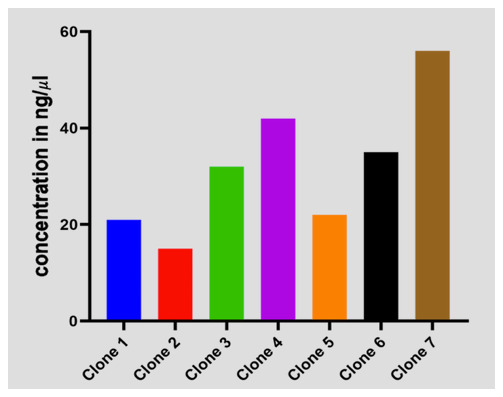

Plasmid C. trachomatis-DNA concentration in ng/μl of transformed E. coli cells

To validate the exact regions that were amplified by the C. trachomatis-IMRS primers, we cloned and transformed the amplicon into blunt vectors into electrocompetent E. coli cells, thereafter, the clones were plated on agar plates. Transformed cells were selected from eight colonies ( Figure 5) and DNA extracted and sanger sequencing performed. Multiple sequence alignment confirmed C. trachomatis sequences. These shows that the C. trachomatis-IMRS primers are specific for targets within the C. trachomatis genome.

Figure 5. Transformed E.coli cells expressing Chlamydia trachomatis sequences amplified using C. trachomatis-identical multi repeat sequence (IMRS) primers.

Validation of C. trachomatis-IMRS primers

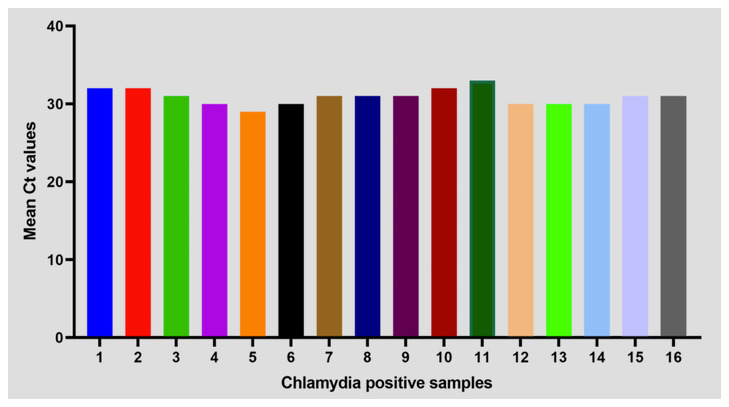

Chlamydia trachomatis positive DNA samples from a cross-sectional study at the Kenyatta National Hospital were used to validate the C. trachomatis-IMRS primers for identifying C. trachomatis DNA using RT-PCR assay as indicated in Figure 6. The demographic information for recruited participants has been described in Table 5. Results from RT-PCR assay using C. trachomatis-IMRS primers were concordant with the results from conventional PCR. The performance characteristics for the CT-IMRS PCR was as follows: sensitivity, 100% (95% CI, 79.41% - 100%) and specificity, 100% (95% CI, 79.41% - 100%)

Figure 6. Mean Ct values of PCR confirmed 16 clinical DNA samples from RT-PCR assay that were used to validate the Chlamydia trachomatis-identical multi repeat sequence (IMRS) PCR primers.

Table 5. Demographic data for participants.

| Variable | Chlamydia

positive, n = 16,(%) |

Chlamydia

negative, n = 187, (%) |

P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Category | ||||

| 10 – 19 | 0, 0 | 2, 1 | 0.9467 | |

| 20 – 29 | 6, 38 | 63, 34 | ||

| 30 – 39 | 9, 56 | 105, 56 | ||

| 40 – 49 | 1, 6 | 17, 9 | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 13, 81 | 161, 86 | 0.5949 | |

| Not Married | 3, 19 | 26, 14 | ||

| Level of Education | ||||

| Primary | 1, 6 | 14, 7 | 0.5013 | |

| Secondary | 8, 50 | 66, 35 | ||

| Tertiary | 7, 44 | 107, 57 | ||

| Employment status | ||||

| Employed | 8, 50 | 55, 29 | 0.0875 | |

| Not employed | 8, 50 | 132, 71 | ||

| Parity | ||||

| Primipara | 1, 6 | 39, 21 | 0.3702 | |

| Multipara | 14, 88 | 138, 74 | ||

| Grandmultipara | 1, 6 | 10, 5 | ||

| Gestational Age | ||||

| First trimester | 0, 0 | 11, 6 | 0.0637 | |

| Second trimester | 7, 44 | 37, 20 | ||

| Third trimester | 9, 56 | 139, 74 | ||

| HIV Status | ||||

| Positive | 1, 6 | 1, 1 | 0.0263 | |

| Negative | 15, 94 | 186, 99 | ||

| Miscarriage | ||||

| None | 9, 56 | 111, 59 | 0.8421 | |

| Once | 5 | 52, 28 | ||

| Twice | 2 | 14, 7 | ||

| Thrice | 0, 0 | 7, 11 | ||

| Quadruple | 0, 0 | 3, 2 |

Specificity and sensitivity of the C. trachomatis-IMRS primers

As indicated in Figure 7, C. trachomatis-IMRS primers showed specificity to C. trachomatis DNA and non-specific to Trichomonas vaginalis and Treponema pallidum genomic DNA. Compared to the conventional 16S-rRNA PCR, the C. trachomatis-IMRS PCR accurately detected C. trachomatis genomic DNA at starting template concentration of 1 fg/μl ( Figure 1B).

Figure 7. Gel image of PCR products obtained after amplification of Treponema pallidum (TP) and Trichomonas vaginalis (TV) genomic DNA using Chlamydia trachomatis-identical multi repeat sequence (IMRS) primers.

C. trachomatis genomic DNA was used as a positive control. N = Negative control, L = Ladder.

Discussion

Traditional techniques for identifying C. trachomatis infections are less sensitive, require collection of invasive patient samples, have complex algorithms and test result reporting, and are expensive 17 . As a consequence, there is need of developing novel tests that are sensitive, specific and readily applicable in field set-ups. In the present study, we demonstrate the use of a deep genome mining strategy to identify identical multiple repeat sequences that could be used as robust primers for a novel nucleic acid-based test that is a highly sensitive test against C. trachomatis. Specifically, IMRS forward and reverse primers are able to initiate amplicon generation at various loci on the C. trachomatis genome. Therefore, the overall analytical sensitivity is improved by producing many amplicons 22, 23 . Our findings confirm that, compared to the gold standard 16S rRNA PCR, using IMRS primers to amplify of specific sequences on the C. trachomatis genome is sensitive, yielding large number of amplicons of different sizes hence a lower detection limit of 9.5 pg/mL (8.4 genome copies/mL). Our results are comparable to the Chlamydial Roche Amplicor Real-Time Quantitative PCR with a lower limit of detection of 200 genome copies/ml 24 . However, this assay targets up to 10 copies of chlamydial plasmid.

We also confirmed that isothermal amplification of DNA using IMRS PCR primers is reliable and sensitive for detecting C. trachomatis. The C. trachomatis-Iso-IMRS assay detected DNA up to 8.9 genome copies per mL. The Isothermal-IMRS assay had increased sensitivity compared to a Loop-mediated isothermal assay utilizing the ompA and orf1 genes, which reported a detection limit of 50 copies per mL 25 .

Our study had success in developing and testing a Lateral Flow Assay technology to detect C. trachomatis to a concentration of 10 pg/mL (8.8 genome copies/ml) ( Figure 6). Our finding was different from a study that developed a visual read-out of C. trachomatis-LAMP method based on a gold nanoparticle lateral flow biosensor that reported a limit of detection of 50 copies/ml after an incubation of 45 minutes 26 .

Compared to nucleic acid methods that are used for the identification of C. trachomatis that are mostly suboptimal, the C. trachomatis-IMRS PCR primers were specific and sensitive when used for the identification of C. trachomatis DNA.

The study limitation was the use of few clinical samples to validate the C. trachomatis IMRS PCR assay.

Conclusions

Put together; here we show that the IMRS algorithm can serve as a platform technology for designing primers that are sensitive and specific for C. trachomatis. This platform has potential application in other bacterial and non-bacterial pathogens and could significantly improve future disease diagnostics procedures. The use of the C. trachomatis -IMRS primers when modified with fluorescent tags can be used to develop a visual read-out signal of DNA which can then be used in the design of a Lateral Flow Assay as has been described previously 27 .

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank Dr. Karen Muthembwa and all staff working at the Sexually transmitted infection Clinic at the Kenyatta National Hospital, in Nairobi County.

An earlier version of this article can be found on medRxiv (doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.07.19.22272924). An earlier version of the abstract can be found on sciety ( https://sciety.org/articles/activity/10.1101/2023.07.19.22272924).

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the African Academy of Sciences (AAS) through a Future Leaders African Independent Researchers (FLAIR) Scheme (FLR\R1\201314) awarded to JG.

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

[version 2; peer review: 2 approved]

Data availability

Underlying data

Zenodo: Chlamydia trachomatis RAW DATA. https://zenodo.org/doi/10.5281/zenodo.10200809 19 .

GenBank: Chlamydia trachomatis D/UW-3/CX, complete genome. Accession number https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc:AE001273.1 21 .

Data are available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC-BY 4.0).

References

- 1. Wynn A, Mussa A, Ryan R, et al. : Evaluating the diagnosis and treatment of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae in pregnant women to prevent adverse neonatal consequences in Gaborone, Botswana: protocol for the Maduo study. BMC Infect Dis. 2022;22(1): 229. 10.1186/s12879-022-07093-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Olaleye AO, Babah OA, Osuagwu CS, et al. : Sexually transmitted infections in pregnancy - An update on Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;255:1–12. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gadoth A, Shannon CL, Hoff NA, et al. : Prenatal chlamydial, gonococcal, and trichomonal screening in the Democratic Republic of Congo for case detection and management. Int J STD AIDS. 2020;31(3):221–9. 10.1177/0956462419888315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Armstrong-Mensah E, Ebiringa DP, Whitfield K, et al. : Genital Chlamydia Trachomatis infection: prevalence, risk factors and adverse pregnancy and birth outcomes in children and women in sub-Saharan Africa. Int J MCH AIDS. 2021;10(2):251–7. 10.21106/ijma.523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. World Health Organization: Sexually transmitted infections.2019;27:9–10. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 6. Budai I: Chlamydia trachomatis: Milestones in clinical and microbiological diagnostics in the last hundred years: a review. Acta Microbiol Immunol Hung. 2007;54(1):5–22. 10.1556/AMicr.54.2007.1.2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Meyer T: Diagnostic procedures to detect Chlamydia trachomatis infections. Microorganisms. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI);2016;4(3):25. 10.3390/microorganisms4030025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Böhm I, Gröning A, Sommer B, et al. : A German Chlamydia trachomatis screening program employing semi-automated real-time PCR: results and perspectives. J Clin Virol. 2009;46 Suppl 3:S27–32. 10.1016/S1386-6532(09)70298-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Elnifro EM, Storey CC, Morris DJ, et al. : Polymerase chain reaction for detection of Chlamydia trachomatis in conjunctival swabs. Br J Ophthalmol. 1997;81(6):497–500. 10.1136/bjo.81.6.497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Watson EJ, Templeton A, Russell I, et al. : The accuracy and efficacy of screening tests for Chlamydia trachomatis: A systematic review. J Med Microbiol. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins;2002;51(12):1021–31. 10.1099/0022-1317-51-12-1021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Masek BJ, Arora N, Quinn N, et al. : Performance of three nucleic acid amplification tests for detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae by use of self-collected vaginal swabs obtained via an internet-based screening program. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47(6):1663–7. 10.1128/JCM.02387-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Papp JR, Schachter J, Gaydos CA, et al. : Recommendations for the laboratory-based detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae - 2014. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2014;63(RR-02):1–19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lanjouw E, Ouburg S, de Vries HJ, et al. : 2015 European guideline on the management of Chlamydia trachomatis infections. Int J STD AIDS. 2016;27(5):333–48. 10.1177/0956462415618837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. CDC: MMWR Chlamydia testing. Guidelines. 2002;51:48. [Google Scholar]

- 15. de Haro-Cruz MJ, Guadarrama-Macedo SI, López-Hurtado M, et al. : Obtaining an ELISA test based on a recombinant protein of Chlamydia trachomatis. Int Microbiol. 2019;22(4):471–8. 10.1007/s10123-019-00074-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bianchi S, Frati ER, Canuti M, et al. : Molecular epidemiology and genotyping of Chlamydia trachomatis infection in a cohort of young asymptomatic sexually active women (18–25 years) in Milan, Italy. J Prev Med Hyg. 2016;57(3):E128–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shetty S, Kouskouti C, Schoen U, et al. : Diagnosis of Chlamydia trachomatis genital infections in the era of genomic medicine. Braz J Microbiol. Brazilian Society of Microbiology;2021;52(3):1327–39. 10.1007/s42770-021-00533-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Raju LS, Kamath S, Shetty MC, et al. : Genome mining-based identification of identical multirepeat sequences in Plasmodium falciparum genome for highly sensitive real-time quantitative PCR assay and its application in malaria diagnosis. J Mol Diagn. 2019;21(5):824–38. 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2019.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shiluli C: Chlamydia trachomatis RAW DATA. Zenodo . [Dataset].2023. 10.5281/zenodo.10200810 [DOI]

- 20. Graham EK, Drobac J, Thompson J, et al. : Evaluation of the PowerQuant ® System on the QuantStudio TM 5 Real-Time PCR System. White Pap Promega Corp,2018;1–12. Reference Source

- 21. Stephens RS, Kalman S, Lammel CJ, et al. : Chlamydia trachomatis D/UW-3/CX, complete genome. GenBank . [Dataset].2014. https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc:AE001273.1

- 22. Balows A: Manual of clinical microbiology 8th edition. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2003;47(4):625–6. 10.1016/S0732-8893(03)00160-3 7135312 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kulkarni S, Bala M, Risbud A: Performance of tests for identification of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Indian J Med Res. 2015;142(6):833–5. 10.4103/0971-5916.160721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wiggins R, Graf S, Low N, et al. : Real-time quantitative PCR to determine chlamydial load in men and women in a community setting. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47(6):1824–9. 10.1128/JCM.00005-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chen X, Zhou Q, Yuan W, et al. : Visual and rapid identification of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae using multiplex loop-mediated isothermal amplification and a gold nanoparticle-based lateral flow biosensor. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2023;13: 1067554. 10.3389/fcimb.2023.1067554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chen X, Zhou Q, Tan Y, et al. : Nanoparticle-Based lateral flow biosensor integrated with loop-mediated isothermal amplification for rapid and visual identification of Chlamydia trachomatis for point-of-care use. Front Microbiol. 2022;13: 1914620. 10.3389/fmicb.2022.914620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Peters RPH, Klausner JD, Mazzola L, et al. : Novel lateral flow assay for point-of-care detection of Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection in syndromic management settings: a cross-sectional performance evaluation. Lancet. 2024;403(10427):657–664. 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)02240-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]