Abstract

Sandy sediments of lowland streams are transported as migrating ripples. Benthic microorganisms colonizing sandy grains are exposed to frequent moving–resting cycles and are believed to be shaped by two dominant environmental factors: mechanical stress during the moving phase causing biofilm abrasion, and alternating light–dark cycles during the resting phase. Our study consisted of two laboratory experiments and aimed to decipher which environmental factor causes the previously observed hampered sediment-associated microbial activity and altered community structure during ripple migration. The first experiment tested the effect of three different migration velocities under comparable light conditions. The second experiment compared migrating and stationary sediments under either constant light exposure or light oscillation. We hypothesized that microbial activity and community structure would be more strongly affected by (1) higher compared to lower migration velocities, and by (2) light oscillation compared to mechanical stress. Combining the results from both experiments, we observed lower microbial activity and an altered community structure in sediments exposed to light oscillation, whereas migration velocity had less impact on community activity and structure. Our findings indicate that light oscillation is the predominating environmental factor acting during ripple migration, resulting in an increased vulnerability of light-dependent photoautotrophs and a possible shift toward heterotrophy.

Keywords: community structure, light oscillation, metabolism, microbial communities, migrating bedforms, streambed

Microbial communities of migrating ripples in sandy lowland streams show decreased microbial activity and an altered community composition, driven by light oscillation rather than by mechanical forces.

Introduction

Microbial communities colonizing benthic sediments of shallow rivers and streams are responsible for the majority of nutrient and energy cycling in stream ecosystems, as they form the basal trophic level of the ecosystem food web (Lear et al. 2008, Besemer 2015, Battin et al. 2016). These surface-associated communities are a consortium of mainly heterotrophic and autotrophic microorganisms, embedded in a matrix of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS; Sigee 2004, Flemming and Wingender 2010, Romaní et al. 2016). The microorganisms interact via carbon and nutrient cycling, modulating biogeochemical processes at the water–sediment interface (Fischer and Pusch 2001, Battin et al. 2016, Leff et al. 2016, Gerbersdorf et al. 2020). Benthic microbial communities can alter bed morphology and erodibility characteristics (Gerbersdorf et al. 2008, Piqué et al. 2016, Chen et al. 2017). In turn, the composition and functioning of microbial communities are shaped by a multitude of environmental factors, e.g. hydrological variation (Zoppini et al. 2010, Romaní et al. 2013, Risse-Buhl et al. 2017), fine sediment deposition (Wagenhoff et al. 2013, Baattrup-Pedersen et al. 2020), and irradiance (Wagner et al. 2015, Prieto et al. 2016, Bengtsson et al. 2018).

In rivers draining lowland alluvial and glacial landscapes, sand is the dominating substrate owing to particle sorting and grain size diminishing along the river continuum (Brussock et al. 1985, Wantzen et al. 2014). Fluctuations of flow and bed roughness provoke instability of riverbeds resulting in sand entrainment (Moss 1975, Kobayashi and Madsen 1985, Nelson et al. 2011, Charru et al. 2013). Consequently, fine sand grains (∼ 0.1–0.7 mm) of the upper sediment layer (<2 cm) are recurrently eroded and deposited at flow velocities in the range of <0.2 to 0.6 m s–1, creating patterns of nearly sinusoidal bedforms that migrate along the riverbed parallel to flow direction (Baas 1999, 2003, Verdonschot 2000, Uehlinger et al. 2002). These so called migrating ripples have a triangular shape with a flatter upriver (stoss) and a steeper downriver slope (lee) and are usually 6–20 cm long and 1–2 cm high (Engelund and Fredsoe 1982, Raudkivi 1997, Friedrich et al. 2004). It is estimated that patches of migrating ripples in sand-dominated streams can cover 20%–50% of natural riverbeds and up to 100% in degraded riverbeds (Mutz et al. 2001, Wallbrink 2004, Rabení et al. 2005, Marcarelli et al. 2015).

As the ripple migrates, sand grains undergo continuous moving–resting cycles (Baas 2003, Scheidweiler et al. 2021). When a critical shear stress is reached, the uppermost sand grains erode and are entrained along the stoss side of the ripple during the moving phase (McLean 1990, Valance 2005). After passing the ripple crest, they are deposited on the ripple lee side or in the trough between two adjacent ripples. At daytime, sand grains are exposed to light for several seconds during the moving phase. Soon after they have come to rest on the lee side, sand grains are buried for minutes to hours under subsequently depositing grains. Light availability quickly decreases within sandy sediments, creating a thin photic zone of less than 2 mm (Scheidweiler et al. 2021). Light does not reach buried sediment grains during the following resting phase, so the resting grains remain in dark while the ripple migrates downriver. A new moving–resting cycle starts as soon as rested grains become uncovered and begin to erode again. The time required to conclude one moving–resting cycle (i.e. turnover frequency) is strongly related to ripple migration velocity and morphology (Teitelbaum et al. 2022). The moving phase ranges on the scale of seconds and is two orders of magnitudes shorter than the resting phase (minutes to hours) according to ripple size and ripple migration velocity (Baas 1999, Bridge 2003, Harvey et al. 2012).

Ripple migration increases pore water exchange and dissolved oxygen fluxes (Ahmerkamp et al. 2015, Zheng et al. 2019, Wolke et al. 2020), whereas microbial metabolism is constrained compared to sediments in stationary patches (Atkinson et al. 2008, Zlatanović et al. 2017, Scheidweiler et al. 2021). Therefore, we postulate that two key environmental drivers, namely mechanical forces and light availability, predominantly shape the formation and stability of microbial communities in migrating ripples (Wimpenny et al. 2000, Burns and Ryder 2001, Wellnitz and Rader 2003). During the moving phase, microorganisms experience favorable light conditions but suffer from mechanical forces, as sediment grains collide, resulting in cell disruption and abrasion of cells attached to the sediment grain (Miller 1989). Elevated mechanical shear stress can destabilize the microbial community (Schwendel et al. 2010, Thom et al. 2015, Schmidt et al. 2018) and decrease microbial diversity by maintaining the population in an early successional stage (Wellnitz and Rader 2003, Rickard et al. 2004, Rochex et al. 2008). During the resting phase, microbial communities remain dark and stationary. Here, phototrophic organisms can suffer from limited light availability, which restrains their photosynthetic activity (Hill et al. 1995, 2001, Dodds et al. 1996, Roeselers et al. 2007, Prieto et al. 2016). Recent studies reported that microbial community structure (consisting of bacteria, algae, and meiobenthos) in migrating ripples differed from that found in stationary sediments (Kryvokhyzhyna et al. 2022, Oprei et al. 2023) as ripple migration acts as an environmental filter (Risse‐Buhl et al. 2023). Despite the documented effects of ripple migration on the structure and activity of microbial communities, the driving environmental factor has not yet been identified.

In this study, we wanted to unravel to what extent mechanical forces and light contribute to shaping microbial community structure and activity of the sediment-associated microbial community. To answer this question, we designed two independent microcosm experiments: first, we assessed the effect of different grain turnover frequencies resulting from variation in ripple migration velocity while providing constant light conditions. Second, we investigated the effect of different light regimes on migrating and stationary sediment. Past studies reported that microbial biomass decreased along an increasing gradient of shear stress (Lau and Liu 1993), and that reduced light availability exceeded the effects of frequent storms (exerting hydraulic scour and mechanical stress on the streambed) on whole stream metabolism (Blaszczak et al. 2019). Based on these findings, we hypothesized that (1) higher turnover frequencies of sediment grains in migrating ripples have a more pronounced impact on the sediment community structure and activity than lower migration velocities. Moreover, we hypothesized that (2) light oscillation in migrating ripples has a more pronounced effect on the microbial structure and activity compared to mechanical forces.

Materials and methods

Each hypothesis was tested with a separate microcosm experiment under controlled conditions in the laboratory. We followed a two-step experimental design to test the effect of mechanical forces (Experiment I—Exp-I) and oscillating light (Experiment II—Exp-II) on the structure and activity of the phototrophic and heterotrophic microbial community of sandy sediments. The experimental setup generally followed that of previous studies described in Risse-Buhl et al. (2014), Zlatanović et al. (2017) and Scheidweiler et al. (2021).

Study site and sampling

Sediments were collected from five random sites along a 50-m reach from River Spree (near Cottbus, Germany, UTM coordinates 51°50′N and 14°20′E) in May (Exp-II) and July (Exp-I) 2020 (Fig. S1). At the sampling site, the River Spree is a third order lowland river fully exposed to sunlight (Oprei et al. 2023). Light intensity on the riverbed in 60 cm depth was ~900 µmol m−2 s−1. We sampled sediments from the top 1.5 cm of migrating ripples and stationary patches. Sediments were mainly composed of sand (90%) and to a minor extent of fine gravel (10%) and silt (<0.1%). We mixed migrating and stationary sediments in a 5:1 ratio representing the relative distribution of migrating ripple (83%) and stationary (17%) sediment patches observed on the riverbed. River water for microcosm incubations and nutrient analysis was collected and filtered (10 µm) on each sampling day. Sediment samples were transported submerged, aerated, dark and cool to the laboratory (<2 h).

Experimental set-up

Microcosms (48 ml glass tubes, 9 cm long, 2.7 cm diameter) were filled with sampled sediment (5 g dry weight, DW), filtered river water, and sealed airtight without headspace. All microcosms were placed horizontally resulting in a maximum sediment depth of 2.5 mm. Our own measurements of the light penetration depth showed that light reached to 2.5 mm in sampled sediments (5% of sediment surface light). Thus, the chosen amount of sediment in microcosms guaranteed photic conditions for the associated microbial community. Microcosms were either attributed a migrating or a stationary treatment (see details on experimental treatments below). Migrating ripple conditions were simulated by rotating microcosms along their longitudinal axis (Zlatanović et al. 2017, Scheidweiler et al. 2021) at treatment-specific intervals. In order to mimic stationary conditions, we added a hollow glass balloon to each microcosm and tilted the microcosms along their short axis at a constant and gentle pace. The glass hollows slowly moved in the supernatant water above the sediment layer, creating gentle water movement and turbulence that allowed pore water exchange with the supernatant water without sediment movement. Sediment samples were incubated for a period of 8 days. The supernatant water in microcosms was exchanged every second day to avoid nutrient limitation of microbial communities as well as anoxic (<2 mg l−1) or hyperoxic (above O2 saturation) conditions. In order not to remove any fine-particulate organic matter (OM), we used a syringe to carefully suck the supernatant water and to replace it with fresh water. All microcosms were placed in a climate chamber at a constant temperature of 20.9 ± 0.1°C (Exp-I) and 13.8 ± 0.1°C (Exp-II), mimicking water temperature at the time of sampling, and cycles of 14 h day and 10 h night for 8 days. During day periods, light (60 ± 10 µmol m−2 s−1, IP65 Premium 24 V COB Filament LED) was provided at treatment-specific intervals (see details on experimental treatments below). During night periods, all microcosms were in dark.

Microbial activity [community respiration, CR; and net community production, NCP, which is the difference between gross primary production (GPP) and CR] was measured 2 h following incubation of the sediments (initial activity) and at the end of the 8-day experiment (final activity; each n = 5). Microbial community structure assessments (bacterial amplicon sequencing and gene abundance, autotrophic morphotypes) were carried out for initial sediments after sampling and before treatment allocation, and at the end of the experiment individually for each treatment and replicate (n = 3). DW from each sediment was obtained by drying the sample until constant mass at 60°C. OM content was then determined via ash free dry mass after combustion at 450°C for 4 h.

Experiment I: effect of mechanical forces on microbial community

In a first experiment (Exp-I), we aimed to decipher the effect of different ripple migration velocities on microbial community structure and activity (Fig. S2A). Three treatments were allocated to sediments that followed a gradient of migration velocities representing the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentile of migration velocities measured in River Spree (n = 460): (i) low migration velocity of 6 cm h−1 (MIG-low), (ii) medium migration velocity of 37 cm h−1 (MIG-med), and (iii) high migration velocity of 69 cm h−1 (MIG-high). To mimic theoretical turnover frequencies of sediment grains, rotation of microcosms occurred in MIG-low every 92 min (turnover frequency of 0.65 h−1), in MIG-med every 13 min (4.62 h−1), and in MIG-high every 5 min (12 h−1) (Table 1). Rotation lasted 29 s for all treatments. The gradient of migration velocities entails a gradient of light oscillation, with higher migration velocities having a more frequent shift between light and dark periods. Therefore, the light periods of each treatment oscillated in parallel to its turnover frequency, translating into returning cycles of 19.3 min light and 72.7 min dark (MIG-low), 3.8 min light and 9.2 min dark (MIG-med), and 1.8 min light and 3.2 min dark (MIG-high). These recurring light–dark cycles were applied only during the 14 h day period.

Table 1.

Overview of experimental treatments for Exp-I and Exp-II (treatment labels are explained in the text). Migration velocities simulated in the lab represent the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentile of migration velocities measured in River Spree. Grain turnover frequency describes the number of turnovers of single sediment grains based on their migration velocity. During the day period, all treatments were assigned a light–dark oscillation regime, connected to the characteristic light–dark shifts in migrating ripples. Grey shaded treatments mark identical settings for Exp-I and Exp-II.

| Day period (14 h) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Ripple migration velocity (cm h−1) | Grain turnover frequency (h−1) | Light (moving phase) | Dark (resting phase) | |

| Exp-I | MIG-low | 6 | 0.65 | 19.3 min | 72.7 min |

| MIG-med | 37 | 4.72 | 3.2 min | 9.8 min | |

| MIG-high | 69 | 12.15 | 1.8 min | 3.2 min | |

| Exp-II | MIG-osc | 37 | 4.72 | 3.2 min | 9.8 min |

| STA-osc | – | – | 3.2 min | 9.8 min | |

| STA-const | – | – | 14 h | – | |

Experiment II: disentangling light and mechanical effects during ripple migration

In a second experiment (Exp-II), we aimed to disentangle mechanical effects from light effects (Fig. S2B). Consequently, microcosms with sediment samples were assigned three different treatments: (i) a migrating ripple treatment with a medium migration velocity of 37 cm h−1 and corresponding frequent light–dark oscillation (MIG-osc), which is the natural condition for migrating ripples, (ii) a stationary treatment experiencing the same light–dark oscillation (STA-osc), and (iii) a stationary treatment under constant light exposure (STA-const), which is characteristic for stable, immobile sediments. The MIG-osc treatment is analogous to the MIG-med treatment in Exp-I in terms of simulated light oscillation and migration velocity, meaning that microcosms rotated every 13 min for 29 s, resulting in a grain turnover frequency of 4.62 h−1 (Table 1). The oscillating light–dark shifts in MIG-osc and STA-osc treatments were comprised of returning cycles of 3.2 min light and 9.8 min dark during the day periods. STA-const microcosms were constantly exposed to light for 14 h (Table 1).

Dissolved nutrients

Water was collected from the River Spree during sampling, filtered (prewashed 0.45 µm cellulose acetate filters) and stored at –18°C for later analysis of dissolved organic carbon (DOC), nitrate–nitrogen (N-NOx), and soluble reactive phosphorous (SRP). Ammonium–nitrogen (N-NH4) was measured in filtered river water using a UV/VIS spectrometer (Perkin Elmer, Rodgau, Germany) within 24 h, according to DIN 38406‐E5. DOC was measured with a total organic carbon analyzer (Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan; Risse-Buhl et al. 2017). SRP and N-NOx were determined spectrophotometrically by a segmented flow injection analyzer (PERSTORP Analytical, Rodgau, Germany).

Microbial activity

Estimates of NCP, CR, and GPP followed the light–dark-bottle method (Gaarder and Gran 1927). We equipped microcosms with optode spots (PreSens GmbH, Regensburg, Germany) to record dissolved oxygen (DO) concentrations every 15 min using fiber optic oxygen meters (PreSens GmbH). Three additional microcosms containing only filtered river water served as controls to differentiate between water and sediment-associated metabolic activity. DO concentrations were corrected for current atmospheric pressure and temperature. We removed measurements during the initial 2 h of each light/dark cycle, and during 6 h following each water exchange. The slope of linear regressions of DO concentrations over time (µg O2 h−1) in each day (14 h) and night (10 h) period served as proxies for NCP and CR rates, respectively. GPP was then obtained by subtracting CR from NCP individually for each replicate (Gaarder and Gran 1927). Respiration rates were standardized to 20°C for comparability, using the temperature normalization by Winkler et al. (1996) with a Q10 factor of 2. In order to compare metabolic activity with structural parameters, we focus on initial (day 1) and final (day 8) rates only (each n = 5).

Autotrophic abundance and composition

We followed the protocol described in Mendoza-Lera et al. (2017) to detach autotrophs from sediment grains. We added 3 ml of deionized water to sediments (0.9–2.8 g DW), vortexed for 1 min at maximum velocity, and sonicated for 5 min at low intensity. A supernatant subsample (250–700 µl) was placed in an Utermöhl chamber (Hydrobios, Germany) and left settling overnight before counting diatom morphotypes. Morphotypes were identified to the lowest possible taxonomic level, mainly genus (Streble and Krauter 1988, Cox 1996, von Berg et al. 2012). Approximately 500 cells were observed at 400x magnification using an inverse light microscope (Ti-U Eclipse; Nikon, Tokio, Japan).

Bacterial amplicon sequencing

Sediment DNA was extracted from 0.1 g DW using Quick-DNA Fecal/Soil Microbe Miniprep Kit (Zymo Research, Freiburg, Germany). We amplified bacteria by targeting the 16SrRNAV3–V4 genomic region with primer pairs 341Fh and 806Rv2. For amplicon sequencing, we used 9 µl of extracted DNA solution of each sample and added 6 µl of GoTaq© Flexi Buffer (5x, Promega), 3 µl MgCl2 (25 mM), 0.24 µl of each primer, 0.6 µl dNTP (10 mM), 1.8 µl bovine serum albumin (10 mg ml−1), 8.82 µl of MilliQ water, and 0.3 µl Hot start Taq (5 U ml−1, Promega). PCR amplification steps were set to 2 min at 95°C. The following 36 amplification cycles included denaturation (94°C for 40 s), primer annealing (58°C for 40 s), elongation (72°C for 1 min), and a final elongation (72°C for 10 min) step. We later purified amplicons with DNA Clean & Concentrator-5 kit (Zymo, Freiburg, Germany) and sent them to Eurofins Genomics Europe Shared Services GmbH (Konstanz, Germany) for sequencing with Illumina MiSeq v3 platform (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

Bioinformatics

We used the DADA2 pipeline in R for processing the bacterial sequence reads (Callahan et al. 2016). We used the built-in filterAndTrim function to remove primers and truncate reads according to Schreckinger et al. (2021). Bacterial reverse and forward reads were truncated to 270 bp and to 220 bp, respectively. Function mergePairs was used to merge reads with a minimal overlap of 10 and allowed only one mismatch. Chimeras were removed using function removeBimeraDenovo. Taxonomy assignment of amplicon sequencing variants (ASVs) was implemented using IdTaxa from package DECIPHER (Murali et al. 2018) and querying 16S rRNA reads against the SILVA v. 138.1 database (Quast et al. 2013). We discovered 922 392 bacterial reads clustered into 4115 ASVs (Exp-I) and 1 034 404 bacterial reads clustered into 3552 ASVs (Exp-II), respectively. We removed ASVs that were not assigned to the bacteria domain or identified as chloroplast or mitochondria.

Bacterial gene abundance

For the quantification of bacterial 16S rRNA gene abundance we followed the procedures for SYBR Green-based real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) similar to Oprei et al. (2023). In short, the qPCR mixture contained 0.5 µl SYBR Green Master Mix, 4.6 µl ddH20, 0.2 µl of forward primer, 0.2 µl of reverse primer, and 1 µl 10-fold diluted DNA extract. Serial dilutions of purified PCR products from Escherichia coli K12 J53 16S rRNA were used as calibration standards. We ran qPCR using StepOnePlus real-time PCR detection system (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, United States) with a set-up of 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 10 min, and 60 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 58°C for 1 min. Standard curve DNA concentrations were measured via Qubit using Qubit dsDNA BR Assay Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States). The copy number (CN) was calculated as CN = (c × 6.022 × 1023)/660 × N, where c is the measured DNA concentration (µg µl−1) and N is the DNA fragment length (bp) and is presented per g DW.

Statistical analyses

We performed all statistical analyses in the R statistical environment (R Core Team 2022, version 4.2.2) with a threshold of significance of α = 0.05. We analyzed linear models (response ∼ treatment) of microbial activity (GPP and CR), abundance (16S rRNA copy number and diatom cell counts), and alpha diversity (α-diversity) indices for both experiments using one-way permutation tests of analysis of variance (pANOVA, 99 999 iterations) with the aovp function of the package lmPerm (Wheeler and Torchiano 2016). Additionally, pairwise comparisons were conducted by calculating estimated marginal means using emmeans function [package emmeans, (Lenth et al. 2018) and adjusted for Type I error rates using a multivariate t-distribution (“mvt”)]. The function eff_size (package emmeans, Lenth et al. 2018) was used to calculate Hedge’s g (in the following denoted as Hg), which is a standardized effect size not biased by small sample sizes (Hedges 1981). Effect sizes are a useful metric to estimate the magnitude of a treatment effect and provide quantitative information to complement to P-values resulting from qualitative hypothesis testing (Nakagawa and Cuthill 2007, Berben et al. 2012, Cohen 2012). We performed permutational multivariate analyses of variance (PERMANOVA) using dissimilarity matrices (adonis function in the package vegan, Oksanen et al. 2013, 99 999 interations) to analyze differences in microbial community structures with respect to experimental treatment. We tested the multivariate homoscedasticity using the PERMDISP2 procedure (Anderson 2006) with function betadisper (package vegan, Oksanen et al. 2013) and a following permutation test (permutest, 999 permutations, package vegan, Oksanen et al. 2013), which is a multivariate analogue of Levene’s test. We created a nonmetric multidimensional scaling diagram (nMDS) based on Kulczinsky’s (diatoms) or Bray–Curtis dissimilarity matrices (bacteria) at the morphotype and ASV level, respectively, to assess beta diversity (β-diversity) (metaMDS in package vegan, Oksanen et al. 2013). Ordinations summarized the observed differences in community structure relatively well, as the goodness-of-fit (GOF) of stressplots was high (GOF diatoms: 0.99; bacteria: 0.99) and stress-values were acceptable (stress diatoms: 0.11; bacteria: 0.07) (Kruskal and Wish 1978).

Results

Initial conditions

Sampled sediments from both experiments differed slightly in their initial constitution (Table 2). GPP from sediments of Exp-II (sampled in May) was 4.7x higher than that from sediments of Exp-I (sampled in July). CR behaved analogously and was 1.6x higher in Exp-II. Initial sediments from Exp-II were net autotrophic in contrast to net heterotrophic sediments from Exp-I. Whereas bacterial abundance was comparable among sediments from both sampling times, diatom abundance in Exp-I roughly doubled that of Exp-II. The microbial community in May (Exp-II) had a higher OM content and revealed a higher diatom and bacterial α-diversity, as represented by richness and Shannon index, than the community in July (Exp-I). DOC in the river water was comparable among sampling times. But river water in May contained 2.6x higher NOx-N, whereas SRP was only half of that in July.

Table 2.

Initial characterization of river water, sediment, and microbial community structure and activity.

| Parameter | Exp-I | Exp-II | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sampling time | July 2020 | May 2020 | |

| River water | |||

| Nutrients | DOC (mg l−1) | 4.38 ± 0.17 | 4.91 ± 0.13 |

| NH4-N (mg l−1) | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | |

| NO3-N (mg l−1) | 0.60 ± 0.46 | 1.56 ± 0.01 | |

| SRP (mg l−1) | 0.015 ± 0.011 | 0.007 ± 0.000 | |

| Sediment | |||

| Sieve analysis | d50 (µm) | 476.5 | 486.5 |

| OM (mgAFDW gDW−1) | 1.56 ± 0.24 | 2.25 ± 0.16 | |

| Microbial community | |||

| Metabolism | GPP (µgO2h−1gDW−1) | 0.35 ± 0.22 | 1.63 ± 1.28 |

| CR (µgO2h−1gDW−1) | 0.88 ± 0.15 | 1.44 ± 0.15 | |

| GPP:CR (−) | 0.31 ± 0.21 | 1.18 ± 0.98 | |

| Abundance | Diatoms (cells gDW−1) | 6.53 ± 1.70 × 1010 | 3.16 ± 2.55 × 1010 |

| Bacteria (copies gDW−1) | 7.89 ± 6.26 × 104 | 7.43 ± 2.70 × 104 | |

| Alpha diversity | Diatom richness (−) | 10.7 ± 0.6 | 12.7 ± 0.6 |

| Diatom Shannon index (−) | 1.7 ± 0.04 | 2.0 ± 0.06 | |

| Bacteria richness (−) | 320.7 ± 163.2 | 456.0 ± 72.0 | |

| Bacteria Shannon index (−) | 4.1 ± 0.6 | 5.0 ± 0.2 |

Experiment I: mechanical effects during ripple migration

Final microbial activity measured as GPP and CR was reduced compared to initial sediments (Fig. 1A and B), but was not influenced by migration velocity (pANOVA: GPP: P = .26; CR: P = .33), meaning that the frequency of acting mechanical forces had no effect under the conditions applied. The final community remained net heterotrophic (GPP: CR = 0.40 ± 0.09; n = 15). The microbial activity in MIG-low was 11.3% (CR) and 25.8% (GPP) lower compared to the other two treatments (Fig. 1A). Effect magnitude, here represented by effect size and Hedge’s g, was highest between MIG-low and MIG-med and lowest between MIG-med and MIG-high for both CR and GPP (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Microbial metabolism (n = 5) for Exp-I (A: CR; B: GPP) and Exp-II (C: CR; D: GPP). Diamonds mark the mean value (n = 5). Dotted lines mark initial values (n = 15). MIG-low: low migration velocity; MIG-med: medium migration velocity; MIG-high: high migration velocity; MIG-osc: migrating oscillating light; STA-osc: stationary oscillating light; and STA-const: stationary constant light.

Table 3.

Results of pairwise comparisons (emmeans) of Exp−I indicating effect size and Hedge’s g as proxies for effect magnitude, and P-values of pANOVA tests of linear models (response ∼ treatment). Bold numbers indicate significance.

| emmeans | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | Pairwise comparison | Parameter | Effect size | Hedge’s g | P-value |

| Metabolism | MIG-low vs MIG-med | CR | −0.96 | −0.87 | .32 |

| GPP | −1.04 | −0.94 | .27 | ||

| MIG-low vs MIG-high | CR | −0.52 | −0.47 | .69 | |

| GPP | −0.62 | −0.56 | .61 | ||

| MIG-med vs MIG-high | CR | 0.44 | 0.40 | .77 | |

| GPP | 0.42 | 0.38 | .79 | ||

| Abundance | MIG-low vs MIG-med | Diatoms | −1.28 | −1.03 | .33 |

| Bacteria | −1.42 | −1.13 | .27 | ||

| MIG-low vs MIG-high | Diatoms | −0.50 | −0.40 | .82 | |

| Bacteria | −0.99 | −0.79 | .49 | ||

| MIG-med vs MIG-high | Diatoms | 0.78 | 0.63 | .63 | |

| Bacteria | 0.43 | 0.34 | .86 | ||

| Observed richness (α−diversity) | MIG-low vs MIG-med | Diatoms | −0.46 | −0.37 | .84 |

| Bacteria | −3.15 | −2.52 | .02 | ||

| MIG-low vs MIG-high | Diatoms | <0.001 | <0.001 | 1 | |

| Bacteria | −2.72 | −2.18 | .04 | ||

| MIG-med vs MIG-high | Diatoms | 0.46 | 0.37 | .84 | |

| Bacteria | 0.43 | 0.34 | .86 | ||

| Shannon index (α−diversity) | MIG-low vs MIG-med | Diatoms | −0.03 | −0.02 | .99 |

| Bacteria | −2.83 | −2.26 | .03 | ||

| MIG-low vs MIG-high | Diatoms | 0.44 | 0.35 | .86 | |

| Bacteria | −2.50 | −2.00 | .05 | ||

| MIG-med vs MIG-high | Diatoms | 0.46 | 0.37 | .84 | |

| Bacteria | 0.33 | 0.27 | .91 | ||

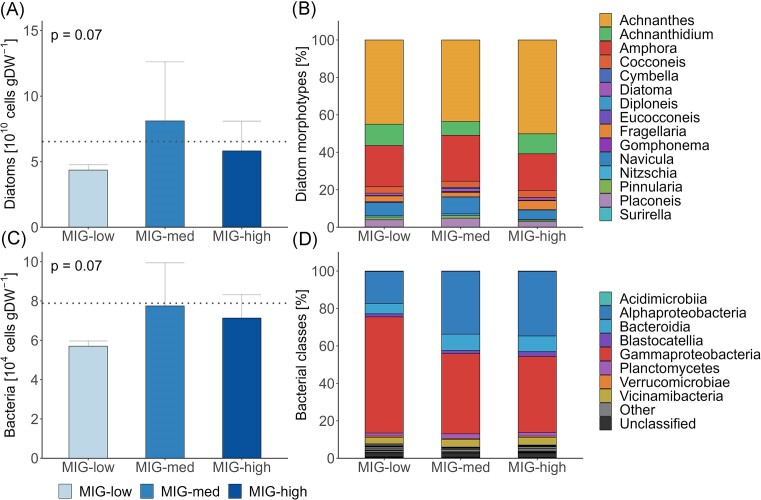

Both diatom abundance (pANOVA: P = .07) as well as bacterial copy number (P = .07) were marginally impacted by migration velocity (Fig. 2A and C). The slightly lower CR in MIG-low sediments was mirrored in a marginally lower diatom abundance (62.6%) and bacterial copy number (76.6%) compared to MIG-med and MIG-high and initial sediments (Fig. 2A and C).

Figure 2.

Absolute abundance (n = 3) of diatom morphotypes (A and B) and bacteria (C and D) of Exp−I. The left panel shows absolute counts of cells (A: diatoms) or 16S copies (C: bacteria), respectively. Dotted lines mark initial values (n = 3). The right panel indicates the relative abundance of diatom cells (B) and bacteria at the class level (D). MIG-low: low migration velocity; MIG-med: medium migration velocity; and MIG-high: high migration velocity.

The diatom communities were comparable among all treatments and were mainly composed of the genera Achnanthes (45.5 ± 8.1%), Amphora (22.7 ± 5.1%), and Achnanthidium (10.6 ± 4.0%; Fig. 2B). The bacterial communities were dominated by Proteobacteria independent of migration velocity (25.6 ± 21.8%; Fig. 2D). However, MIG-low sediments consisted of a larger proportion of Gammaproteobacteria (62.1 ± 7.9%) and a smaller proportion of Alphaproteobacteria (17.0 ± 5.0%) compared to MIG-low and MIG-high sediments (Gammaproteobacteria: 41.7 ± 4.1%; Alphaproteobacteria: 34.0 ± 2.4%; Fig. S3A).

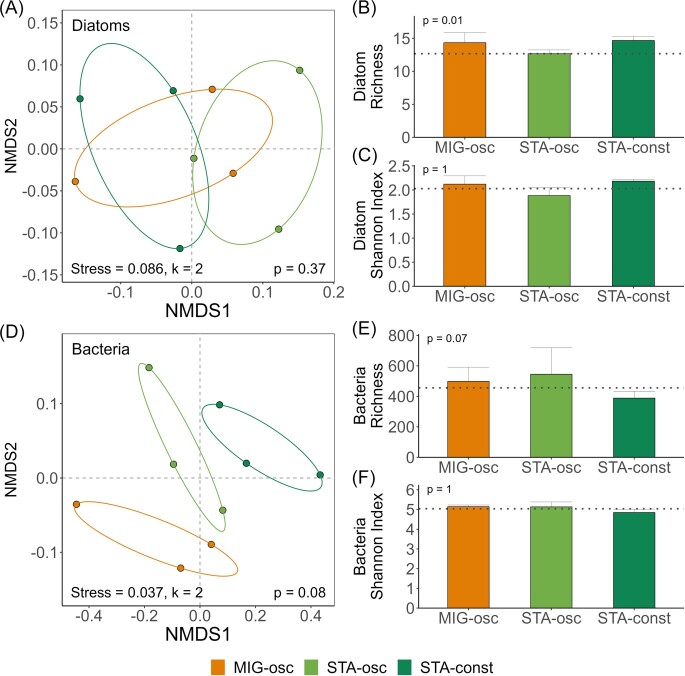

Different migration velocities showed no effect on the diatom β-diversity (PERMANOVA: P = .97; Fig. 3A). In contrast, migration velocity significantly affected the bacterial community structure (PERMANOVA: P = .01). The bacterial community structures of MIG-med and MIG-high were similar but differed from MIG-low as shown in the nMDS (Fig. 3D). Diatom α-diversity remained unaffected by migration velocity (pANOVA: richness: P = .57; Shannon index: P = 1; Fig. 3B and C), which is paralleled by a negligibly small effect magnitude between MIG-low and MIG-high (Table 3). In contrast, MIG-low sediments had a lower bacterial Richness (pANOVA: P < .001) and Shannon index (P = .04) than MIG-med and MIG-high treatments (Fig. 3E and F), as confirmed by the large effect sizes between MIG-low and the other two treatments (Table 3).

Figure 3.

Alpha and beta diversity for diatoms (A–C) and bacteria (D–F) of Exp−I. The left panel shows a nMDS (A: diatoms; D: bacteria). Richness (B: diatoms; E: bacteria) and the Shannon index (C: diatoms; F: bacteria) are presented. Dotted lines mark initial values (n = 3). MIG-low: low migration velocity; MIG-med: medium migration velocity; and MIG-high: high migration velocity.

Experiment II: disentangling light and mechanical effects during ripple migration

Final microbial activity, measured as GPP (pANOVA: P < .001) and CR (P < .001), was affected by treatment. Both oscillating light treatments (MIG-osc, STA-osc) had comparable CR, whereas GPP of MIG-osc was 56.4% lower than that of STA-osc (Fig. 1C and D). Compared to initial sediments, MIG-osc and STA-osc showed reduced microbial activity, whereas CR and GPP increased in STA-const (Fig. 1C and D). This was reflected in a net heterotrophic community in MIG-osc (GPP: CR: 0.72 ± 0.11) in contrast to a net autotrophic community in STA-osc (1.65 ± 0.20). On the contrary, CR and GPP of STA-const sediments were significantly higher (2.6-fold and 11.1-fold, respectively) compared to the two oscillating light treatments (MIG-osc, STA-osc) and the community was clearly net autotrophic (5.07 ± 0.58). The higher microbial activity in STA-const was mirrored in large effect magnitudes obtained from comparisons with oscillating light treatments (Table 4). On the other hand, effect magnitudes resulting from comparisons between MIG-osc and STA-osc were low for both CR and GPP (Table 4).

Table 4.

Results of pairwise comparisons (emmeans) of Exp−II indicating effect size and Hedge’s g as proxies of effect magnitudes and P-values of pANOVA tests of linear models (response ∼ treatment). As only two types of cyanobacteria were identified, neither alpha nor beta diversity for cyanobacteria were assessed. Bold numbers indicate significance.

| emmeans | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | Pairwise comparison | Effect size | Hedge’s g | P-value | |

| Metabolism | STA-const vs STA-osc | CR | 7.65 | 6.91 | < .001 |

| GPP | 10.66 | 9.63 | < .001 | ||

| STA-const vs MIG-osc | CR | 7.41 | 6.69 | < .001 | |

| GPP | 11.46 | 10.35 | < .001 | ||

| STA-osc vs MIG-osc | CR | −0.25 | −0.22 | .92 | |

| GPP | 0.80 | 0.73 | .44 | ||

| Abundance | STA-const vs STA-osc | Diatoms | 1.94 | 1.55 | .12 |

| Bacteria | −0.93 | −0.74 | .53 | ||

| STA-const vs MIG-osc | Diatoms | 1.97 | 1.58 | .11 | |

| Bacteria | −1.27 | −1.01 | .33 | ||

| STA-osc vs MIG-osc | Diatoms | 0.04 | 0.03 | .99 | |

| Bacteria | −0.34 | −0.27 | .91 | ||

| Observed richness (α-diversity) | STA-const vs STA-osc | Diatoms | 2.00 | 1.60 | .11 |

| Bacteria | −1.34 | −1.08 | .30 | ||

| STA-const vs MIG-osc | Diatoms | 0.33 | 0.27 | .91 | |

| Bacteria | −0.94 | −0.75 | .52 | ||

| STA-osc vs MIG-osc | Diatoms | −1.67 | −1.33 | .18 | |

| Bacteria | 0.40 | 0.32 | .88 | ||

| Shannon index (α-diversity) | STA-const vs STA-osc | Diatoms | 2.15 | 1.72 | .09 |

| Bacteria | −1.58 | −1.26 | .21 | ||

| STA-const vs MIG-osc | Diatoms | 0.44 | 0.35 | .86 | |

| Bacteria | −1.63 | −1.31 | .19 | ||

| STA-osc vs MIG-osc | Diatoms | −1.71 | −1.37 | .17 | |

| Bacteria | −0.06 | −0.05 | .99 | ||

The relative proportions of autotrophs under oscillating light (MIG-osc, STA-osc) barely changed until the end of our experiment (60.4 ± 18.0% diatoms, 39.6 ± 18.0% cyanobacteria; n = 6). In contrast, the final autotrophic community in sediments under constant light (STA-const) was largely dominated by diatoms (88.8 ± 18.7%; n = 3; Table 4) and contained only a small amount of cyanobacteria (10.9 ± 18.9%) and a negligible proportion of green algae (0.27 ± 0.31%). Therefore, we focused statistical analysis on treatment effects on diatoms. Diatom abundance was shaped by treatment (pANOVA: P < .001). This was mirrored in a 3.3-fold higher diatom abundance in STA-const compared to MIG-osc and STA-osc as well as initial sediments (Fig. 4A). Similar to microbial activity, the largest effect magnitude arose between treatments of oscillating light (MIG-osc, STA-osc) and the constant light treatment (STA-const, Table 4). The bacterial copy number was unaffected by sediment transport (pANOVA: P = .11). Stationary sediments in STA-const had a 33.3% lower bacterial copy number than in MIG-osc and STA-osc sediments (Fig. 4C). Similarly, effect magnitudes were higher when comparing oscillating light treatments and the constant light treatment as opposed to comparing migrating and stationary sediments (Table 4). The relative proportion of diatoms was comparable among all treatments with the genera Achnanthes (29.9 ± 12.8%), Fragilaria (14.9 ± 6.2%), and Navicula (14.1 ± 4.0%) being predominant (Fig. 4B). Independent of the treatment, all bacterial communities were dominated by Proteobacteria (23.7 ± 18.6%), with major proportions of Gammaproteobacteria (43.8 ± 4.4%) and Alphaproteobacteria (27.3 ± 3.4%; Fig. S3B).

Figure 4.

Absolute abundance (n = 3) of diatom morphotypes (A and B) and bacteria (C and D) of Exp−II. The left panel shows absolute counts of cells (A: diatoms) or 16S copies (C: bacteria), respectively. Dotted lines mark initial values (n = 3). The right panel indicates the relative abundance of diatom cells (B) and bacteria at the class level (D). MIG-osc: migrating oscillating light; STA-osc: stationary oscillating light; and STA-const: stationary constant light.

Beta diversity in diatom communities was comparable among all treatments as shown in the nMDS (PERMANOVA: P = .37; Fig. 5A). In contrast, bacteria showed very distinct but not significantly different community structures among treatments (PERMANOVA: P = .08; Fig. 5D). The richness of diatom communities was significantly altered (pANOVA: P = .01; Fig. 5B and C) whereas that of bacterial communities was not (P = .07; Fig. 5E and F). The highest diatom richness was found in STA-osc and bacterial richness was highest in STA-osc and lowest in STA-const.

Figure 5.

Alpha and beta diversity for diatoms (A–C) and bacteria (D–F) of Exp−II. The left panel shows a nMDS (A: diatoms; D: bacteria). Richness (B: diatoms; E: bacteria) and the Shannon index (C: diatoms; F: bacteria) are presented. Dotted lines mark initial values (n = 3). MIG-osc: migrating oscillating light; STA-osc: stationary oscillating light; and STA-const: stationary constant light.

Discussion

In a series of two microcosm experiments simulating two major environmental factors occurring in migrating ripples, we discovered that light oscillation had a stronger effect on the microbial community structure and activity than mechanical forces, supporting our second hypothesis. Contradicting our first hypothesis, the variation of migration velocities, translating into a gradient of different grain turnover frequencies, did not alter the effects of mechanical forces acting on the microbial community proportionately. Although mechanical forces visibly decreased microbial activity, fostering earlier studies on the detrimental effects of ripple migration (Zlatanović et al. 2017, Scheidweiler et al. 2021), the effect was small in comparison to the impact of light oscillation frequency. Stationary sediments under constant light (STA-const) possessed higher microbial activity and diatom abundance, than both stationary (STA-osc) and migrating (MIG-osc) sediments under oscillating light. Combining the results of both experiments, we postulate three major conclusions: (1) effects of mechanical forces may apply a nonlinear restricting effect remaining constant at higher migration velocities after passing a threshold, (2) phototrophic organisms successfully acclimatize to frequent light–dark oscillation in migrating ripples, and (3) light limitation due to frequent light–dark oscillation in simulated migrating ripples has a more pronounced effect on community structure and function, than mechanical forces.

Mechanical forces in migrating ripples act independently of turnover frequency

First, adverse effects of ripple migration may be threshold-driven and our chosen gradient of simulated migration velocities did presumably not enclose the theoretical threshold migration velocity at which degradation of community metabolism settles in. Even low turnover frequencies, such as in MIG-low in our first experiment, exert rare, yet abrupt mechanical forces on sand grains. Grain erosion on the ripple upstream side provokes saltation and collision of single sand grains regardless of the migration velocity, favoring abrasion and scour of adhered biofilms (Packman and Brooks 2001, Harvey et al. 2012, Schmidt et al. 2018). This may result in reduced abundance, as seen for both diatoms and bacteria in all treatments compared to the initial community. Generation times of freshwater bacteria range between a few hours to several weeks (Hendricks 1972), exceeding the slowest grain turnover in our experiment (every 92 min for MIG-low). Consequently, it is reasonable to assume that microbial communities of all treatments in Exp-I could not fully exploit their growth capacities, and the microbial community could likely not compensate for biomass loss independent of the simulated migration velocity.

The durations of moving–resting cycles in MIG-med (3.8 and 9.2 min) and MIG-high (1.8 and 3.2 min) were more similar to another, than compared to the unequally longer periods of moving and resting phases in MIG-low (19.3 and 72.7 min). This disproportionality may explain why MIG-med and MIG-high behaved similarly in many parameters, e.g. microbial activity, diatom and bacterial abundance, and bacterial community structure (α- and β-diversity). In MIG-med and MIG-high, sediment grains were moved roughly 7x and 18x more frequently than under low migration velocity (MIG-low), respectively, indicating a higher frequency of mechanical forces. However, the more frequently occurring mechanical forces did not translate into a stronger response of microbial activity and abundance. Therefore, we assume that the mechanical disruption of cells and abrasion of biofilm were triggered by a critical threshold, which was likely already met by the lowest turnover frequency of our experiment. Once having passed this threshold, more frequent mechanical forces (linked to high migration velocities) did not further impair microbial activity. In contrast to microbial activity and abundance, the bacterial community structure and alpha diversity differed between MIG-low on the one hand and MIG-med and MIG-high sediments on the other hand. We believe that the reason for this observation may be a rearrangement within the microbial community as a reaction to the environmental driver (here: increased migration speed), possibly disadvantaging formerly dominant species and enabling formerly latent species to compete successfully.

Daily light quantity but not light oscillation frequency drives phototrophic community

The second explanation for comparable microbial activity and abundance under different turnover frequencies may be attributed to light acclimation and metabolic flexibility of diatoms. Similar to bacteria, diatom communities are equally affected by sediment scour and subsequent biomass removal (Miller 1989, Francoeur and Biggs 2006). Therefore, ripple migration generally created a harmful environment for diatoms as evidenced by the reduction of GPP in all treatments of Exp-I compared to the initial community. Yet, the variation in migration velocity as manipulated in our first experiment did not modulate this effect, possibly due to the adaptive capacity of diatoms to changing light conditions: Benthic diatoms thrive under low light availability (Richardson et al. 1983, Bonnineau et al. 2012, Shi et al. 2016), acclimatize rapidly to fluctuating light conditions (Wagner et al. 2006, Lavaud and Goss 2014, Zhou et al. 2021), and dominate dark grown biofilms (Sekar et al. 2002, Barranguet et al. 2005, Izagirre et al. 2008). Another strategy of diatoms to survive under suboptimal light conditions is provided by their ability to switch to heterotrophic metabolism (Zhang et al. 2003, Kamp et al. 2011, Villanova et al. 2017, Marella et al. 2021). Along with increased photosynthetic efficiency (Richardson et al. 1983, Fietz and Nicklisch 2002, Consalvey et al. 2004), facultative heterotrophy may have aided the diatom community to compensate the limited light quantity during the resting phase. In turn, this may have resulted in increased competition between diatoms and bacteria for resources that are heterotrophically utilized such as labile organic compounds (Tuchman et al. 2006). This competition may explain the altered bacterial community structure and lower α-diversity in MIG-low, which had the longest dark period compared to MIG-med and MIG-high, whereas the diatom community structure and α-diversity remained unchanged. As diatoms favor heterotrophy only over autotrophy when environmental conditions make this necessary (Tuchman et al. 2006), for example during a long period of limited light availability, it is reasonable to assume that heterotrophic resource competition dissipated in MIG-med and MIG-high, where light–dark oscillation frequency was high enough for diatoms to ensure phototrophic metabolism.

Photon absorption, dictated by light quantum (Emerson 1958), governs growth and light harvesting efficiency in autotrophic communities. In our first experiment, all microbial communities received overall comparable photoperiods (4 ± 1 h during 14 h of light period), meaning that the accumulated daily light quantity was homogeneous across all three treatments. The diatom community composition in Exp-I remained unchanged and was characterized by comparable α- and β-diversity, mirroring the lacking effect of migration velocity on phototrophic activity (GPP). Thus, our results suggest that the oscillation frequency of light–dark cycles played a minor role for phototrophic activity as long as the overall light quantity still met the cellular requirements of diatoms. This also indicates that diatoms adapted rapidly to light–dark cycle alternation and were insensitive to how often photons were supplied, supporting results from a study of the pelagic zone in a lake by Guislain et al. (2019), where diatoms showed similar light utilization strategies under oscillating and constant light.

Limited light quantity in migrating ripples overrides mechanical forces

In our second experiment, despite reduced activity in migrating sediments (MIG-osc), stationary sediment communities under oscillating light (STA-osc) also experienced lower CR and GPP compared to those under constant light (STA-const) and initial sediments. This suggests that light limiting processes dominated the adverse effect of migrating ripples on the microbial community, while the contribution of mechanical forces seemed marginal and was mainly visible in phototrophic activity (GPP). This observation is backed by the larger effect magnitudes between treatments of oscillating light compared to the constant light treatment, which exceeded effect magnitudes between migrating and stationary sediments by factors of 13 (CR) and 30 (GPP), respectively.

The constant light quantity in STA-const sediments yielded a 3.3-times higher diatom abundance compared to sediments under oscillating light, which is a probable explanation for the increase in GPP. Whereas the relative proportions of diatoms (60%) and cyanobacteria (40%) remained fairly equal under oscillating light and were independent of the transport regime, diatoms (88%) outcompeted cyanobacteria (11%) in the constant light treatment. Yet, enhanced irradiance also entailed higher CR and, surprisingly, led to an altered bacterial, but not diatom community structure. Interactions between benthic diatoms and bacteria have been reviewed extensively (e.g. Bruckner et al. 2011, Amin et al. 2012, Koedooder et al. 2019). Although heterotrophic bacteria do not directly benefit from the increased light quantity, their metabolism, growth capacities and community composition are tightly coupled to the performance of coexisting photoautotrophs (Romaní and Sabater 2000, Ylla et al. 2009, Wagner et al. 2015). For example, diatoms exude EPS, a complex mixture of polysaccharides and glycoproteins (Sutherland 2001, Wotton 2004, Bahulikar and Kroth 2007), which serve as readily available organic carbon resource for bacteria (Bengtsson et al. 2018), fuelling heterotrophic activity as well as bacterial abundance (Danger et al. 2013, Kuehn et al. 2014). However, we believe that in our experiment the increase in CR was rather caused by the increasingly abundant diatoms, since the STA-const treatment exhibited a slight reduction in bacterial abundance and Richness compared to both treatments of oscillating light.

The initial microbial community, which was divided into the different light treatments after sampling, was composed of 83% formerly migrating ripple sediments and 17% formerly stationary sediments. We chose this approach of a homogeneous initial community to represent the relative distribution of migrating and stationary sediment patches in the field. However, this means that microbial colonization in sediments attributed to the stationary experimental treatments (STA-osc and STA-const) had probably been influenced by mechanical abrasion prior to sampling, similar to the simulated migrating ripple treatment (MIG-osc). In combination with our relatively short incubation time (8 days), this possibly explains the comparable community compositions of diatoms and bacteria in migrating and stationary sediments of both light treatments. Therefore, it is reasonable to believe that when choosing different initial microbial communities, i.e. not mixing formerly migrating and stationary sediments, community compositions may no longer be alike, and effects related to community structure likely stand out more clearly. However, the visible effect of light treatment (constant vs oscillating) on bacterial and diatom abundance, microbial activity as well as bacterial community structure in our experiment emphasizes that light quickly evolves as an environmental driver even when initial microbial communities are comparable.

Studying the effects of environmental factors on the activity and structural composition of benthic microbial communities is crucial for understanding biogeochemical processes of aquatic ecosystems. Although we focused on fine sand-streambeds in our study, migrating ripples are ubiquitous in aquatic ecosystems. For example, they are common bedforms in marine biotopes such as coastal sand flats (Friend et al. 2008, Lichtman et al. 2018, Baas et al. 2019, Chen et al. 2023). The two factors illuminated in our experiments, mechanical forces and light limitation, are also present in coastal flats in the form of tidal motion (exerting shear stress on the sole; Chen et al. 2019) shallow water (allowing for a significant supply of sunlight; Gattuso et al. 2006), respectively. Nevertheless, their effect along with other, biotope-specific environmental factors on the community structure and activity of grain-associated microorganisms remains yet to be understood and might stimulate future cross-disciplinary studies.

Our two laboratory experiments untangled two predominant environmental factors acting during bedform migration, light limitation and mechanical forces. Our results demonstrate that, while both factors affected metabolism and community structure of microorganisms residing in migrating bedforms, light limitation had a more restrictive effect on the community than mechanical forces. As we only focused on the photic zone of sediments, it is reasonable to expect that our experiments overall overestimated the phototrophic activity in migrating ripples.

The simulated grain turnover frequencies in this study were derived from field observations of migrating ripples. Other migrating bedforms, such as dunes, have lower grain turnover frequencies and, therefore, disproportionately longer resting times (in the range of several hours) compared to a similarly short moving phase (seconds) (Colombini and Stocchino 2011, Lichtman et al. 2018). Considering the resulting decrease of light to dark period ratio, it is reasonable to assume that the here observed dominance of light limitation over mechanical forces intensifies with increasing bedform size. Further, both environmental factors are considerably influenced by seasonal variations. Whereas hydrological parameters (discharge and flow velocity) drive the occurrence and migration velocity of ripples, light availability in streams depends on incoming light radiation and riparian shading, both varying seasonally. It is possible that the relationship between light limitation and mechanical forces is nonlinear and scales with seasonal changes of abiotic parameters.

We acknowledge that while microcosms are a valuable tool for addressing research questions like the ones proposed in this text, further efforts are required to analyze migrating ripple dynamics in the field. Besides, it is important to consider other factors that may also contribute to light limitation, such as water turbidity, vegetation cover, and water depth, for a more comprehensive understanding of riverbed sediment processes. In rivers with high turbidity, caused by silt- and clay-dominated sediments, the effect of migrating ripples on autotrophs will likely be overridden by the general low light availability for benthic algae. Driven by these limitations of our study, we propose that future research should focus on cross-seasonal observations that incorporate an ensemble of changing environmental conditions (light quantity and hydrologic regimes) as well as varying bedform morphology, to extend the findings from this study over more dynamic spatiotemporal scales.

Author contributions

Anna Oprei (Conceptualization [equal], Formal analysis [lead], Investigation [supporting], Methodology [equal], Visualization [lead], Writing – original draft [lead], Writing – review & editing [lead]), José Schreckinger (Conceptualization [equal], Formal analysis [supporting], Investigation [lead], Methodology [equal], Visualization [supporting], Writing – original draft [equal], Writing – review & editing [supporting]), Insa Franzmann (Investigation [equal], Methodology [equal], Writing – review & editing [supporting]), Hayoung Lee (Investigation [equal]), Michael Mutz (Conceptualization [equal], Funding acquisition [equal], Methodology [equal], Project administration [lead], Resources [equal], Supervision [lead], Writing – review & editing [supporting]), and Ute Risse-Buhl (Conceptualization [equal], Data curation [lead], Funding acquisition [equal], Methodology [equal], Project administration [equal], Resources [equal], Supervision, Writing – review & editing [supporting])

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Gudrun Lippert, Thomas Wolburg, and Mariia Kryvokhyzhyna at BTU Cottbus-Senftenberg for laboratory assistance and technical support, Anja Worrich and Maja Hinkel at UFZ Leipzig for quantification of bacteria copy numbers, Andrea Hoff and Ina Siebert at UFZ Magdeburg for supporting the analysis of dissolved carbon and nutrients, and Jacqueline Rücker for helpful discussion.

Contributor Information

Anna Oprei, Leibniz Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries (IGB), Department of Ecohydrology and Biogeochemistry, Justus-von-Liebig-Str. 7, 12489 Berlin, Germany; BTU Cottbus-Senftenberg, Chair of Aquatic Ecology, Seestr. 45, 15526 Bad Saarow, Germany.

José Schreckinger, BTU Cottbus-Senftenberg, Chair of Aquatic Ecology, Seestr. 45, 15526 Bad Saarow, Germany; RPTU Kaiserslautern-Landau, Institute of Environmental Sciences, Fortstr. 7, 76829 Landau, Germany.

Insa Franzmann, BTU Cottbus-Senftenberg, Chair of Aquatic Ecology, Seestr. 45, 15526 Bad Saarow, Germany.

Hayoung Lee, BTU Cottbus-Senftenberg, Chair of Aquatic Ecology, Seestr. 45, 15526 Bad Saarow, Germany.

Michael Mutz, BTU Cottbus-Senftenberg, Chair of Aquatic Ecology, Seestr. 45, 15526 Bad Saarow, Germany.

Ute Risse-Buhl, RPTU Kaiserslautern-Landau, Institute of Environmental Sciences, Fortstr. 7, 76829 Landau, Germany; RPTU Kaiserslautern-Landau, Ecology, Department of Biolology, Erwin-Schroedinger-Str. 14, 67663 Kaiserslautern, Germany; Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research (UFZ), Department of River Ecology, Brückstr. 3a, 39114 Magdeburg, Germany.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the German Research Foundation to M.M. (MU 1464/7-1) and U.R.B. (RI 2093/2-1) and by a grant from the Carl Zeiss Foundation to U.R.B. (P2021-00-004).

Data Availability

Raw sequences of bacterial communities were archived at NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra, PRJNA1007951).

References

- Ahmerkamp S, Winter C, Janssen F et al. The impact of bedform migration on benthic oxygen fluxes. JGR Biogeosci. 2015;120:2229–42. [Google Scholar]

- Amin SA, Parker MS, Armbrust EV. Interactions between diatoms and bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2012;76:667–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson MJ. Distance-based tests for homogeneity of multivariate dispersions. Biometrics. 2006;62:245–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson BL, Grace MR, Hart BT et al. Sediment instability affects the rate and location of primary production and respiration in a sand-bed stream. J North Am Benthol Soc. 2008;27:581–92. [Google Scholar]

- Baas JH, Baker ML, Malarkey J et al. Integrating field and laboratory approaches for ripple development in mixed sand–clay–EPS. Sedimentology. 2019;66:2749–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baas JH. An empirical model for the development and equilibrium morphology of current ripples in fine sand. Sedimentology. 1999;46:123–38. [Google Scholar]

- Baas JH. Ripple, Ripple Mark, Ripple Structure. In: Encyclopedia of Sediments and Sedimentary Rocks. Dordrecht: Springer, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Baattrup-Pedersen A, Graeber D, Kallestrup H et al. Effects of low flow and co-occurring stressors on structural and functional characteristics of the benthic biofilm in small streams. Sci Total Environ. 2020;733:139331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahulikar RA, Kroth PG. Localization of EPS components secreted by freshwater diatoms using differential staining with fluorophore-conjugated lectins and other fluorochromes. Eur J Phycol. 2007;42:199–208. [Google Scholar]

- Barranguet C, Veuger B, Van Beusekom SAM et al. Divergent composition of algal-bacterial biofilms developing under various external factors. Eur J Phycol. 2005;40:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Battin TJ, Besemer K, Bengtsson MM et al. The ecology and biogeochemistry of stream biofilms. Nat Rev Micro. 2016;14:251–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengtsson MM, Wagner K, Schwab C et al. Light availability impacts structure and function of phototrophic stream biofilms across domains and trophic levels. Mol Ecol. 2018;27:2913–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berben L, Sereika SM, Engberg S. Effect size estimation: methods and examples. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49:1039–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besemer K. Biodiversity, community structure and function of biofilms in stream ecosystems. Res Microbiol. 2015;166:774–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaszczak JR, Delesantro JM, Urban DL et al. Scoured or suffocated: urban stream ecosystems oscillate between hydrologic and dissolved oxygen extremes. Limnol Oceanogr. 2019;64:877–94. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnineau C, Sague IG, Urrea G et al. Light history modulates antioxidant and photosynthetic responses of biofilms to both natural (light) and chemical (herbicides) stressors. Ecotoxicology. 2012;21:1208–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridge JS. Rivers and Floodplains: Forms, Processes, and Sedimentary Record. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bruckner CG, Rehm C, Grossart HP et al. Growth and release of extracellular organic compounds by benthic diatoms depend on interactions with bacteria. Environ Microbiol. 2011;13:1052–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brussock PP, Brown AV, Dixon JC. Channel form and stream ecosystem models. J Am Water Resour Assoc. 1985;21:859–66. 10.1111/j.1752-1688.1985.tb00180.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burns A, Ryder DS. Potential for biofilms as biological indicators in Australian riverine systems. Eco Manag Restor. 2001;2:53–64. [Google Scholar]

- Callahan BJ, McMurdie PJ, Rosen MJ et al. DADA2: high-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat Methods. 2016;13:581–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charru F, Andreotti B, Claudin P. Sand ripples and dunes. Annu Rev Fluid Mech. 2013;45:469–93. [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Kang Y, Zhang Q et al. Biophysical contexture of coastal biofilm-sediments varies heterogeneously and seasonally at the centimeter scale across the bed-water interface. Front Mar Sci. 2023;10:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Zhang C, Paterson DM et al. The effect of cyclic variation of shear stress on non-cohesive sediment stabilization by microbial biofilms: the role of ‘biofilm precursors.’. Earth Surf Processes Landf. 2019;44:1471–81. [Google Scholar]

- Chen XD, Zhang CK, Zhou Z et al. Stabilizing effects of bacterial biofilms: EPS penetration and redistribution of bed stability down the sediment profile. JGR Biogeosci. 2017;122:3113–25. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Using effect size—or why the P value is not enough. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4:279–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombini M, Stocchino A. Ripple and dune formation in rivers. J Fluid Mech. 2011;673:121–31. [Google Scholar]

- Consalvey M, Paterson DM, Underwood GJC. The ups and downs of life in a benthic biofilm: migration of benthic diatoms. Diatom Res. 2004;19:181–202. [Google Scholar]

- Cox EJ. Identification of Freshwater Diatoms from Live Material. London: Chapman & Hall, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Danger M, Cornut J, Chauvet E et al. Benthic algae stimulate leaf litter decomposition in detritus-based headwater streams: a case of aquatic priming effect?. Ecology. 2013;94:1604–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodds WK, Hutson RE, Eichem AC et al. The relationship of floods, drying, flow and light to primary production and producer biomass in a prairie stream. Hydrobiologia. 1996;333:151–9. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson R. The quantum yield of photosynthesis. Annu Rev Plant Physiol. 1958;9:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Engelund F, Fredsoe J. Sediment ripples and dunes. Annu Rev Fluid Mech. 1982;14:13–37. [Google Scholar]

- Fietz S, Nicklisch A. Acclimation of the diatom Stephanodiscus neoastraea and the cyanobacterium Planktothrix agardhii to simulated natural light fluctuations. Photosynth Res. 2002;72:95–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer H, Pusch M. Comparison of bacterial production in sediments, epiphyton and the pelagic zone of a lowland river. Freshwater Biol. 2001;46:1335–48. [Google Scholar]

- Flemming HC, Wingender J. The biofilm matrix. Nat Rev Micro. 2010;8:623–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francoeur SN, Biggs BJF. Short-term effects of elevated velocity and sediment abrasion on benthic algal communities. Hydrobiologia. 2006;561:59–69. [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich H, Coleman S, Melville B et al. Development of discrete subaqueous bed forms. In: River Flow. London: Taylor & Francis, 2004, 761–8. [Google Scholar]

- Friend PL, Lucas CH, Holligan PM et al. Microalgal mediation of ripple mobility. Geobiology. 2008;6:70–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaarder T, Gran HH. Investigations of the production of plankton in the Oslo Fjord. Vol. 42. Cons Perm Int Pour L'Exploration La Mer Rapp Proces-Verbaux Des Reun. Copenhague: Høst en comm, 1927, 48. [Google Scholar]

- Gattuso JP, Gentili B, Duarte CM et al. Light availability in the coastal ocean: impact on the distribution of benthic photosynthetic organisms and their contribution to primary production. Biogeosciences. 2006;3:489–513. [Google Scholar]

- Gerbersdorf SU, Jancke T, Westrich B et al. Microbial stabilization of riverine sediments by extracellular polymeric substances. Geobiology. 2008;6:57–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerbersdorf SU, Koca K, deBeer D et al. Exploring flow-biofilm-sediment interactions: assessment of current status and future challenges. Water Res. 2020;185:116182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guislain A, Beisner BE, Köhler J. Variation in species light acquisition traits under fluctuating light regimes: implications for non-equilibrium coexistence. Oikos. 2019;128:716–28. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey JW, Drummond JD, Martin RL et al. Hydrogeomorphology of the hyporheic zone: stream solute and fine particle interactions with a dynamic streambed. J Geophys Res. 2012;117:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Hedges LV. Distribution theory for Glass's estimator of effect size and related estimators. J Educ Stat. 1981;6:107–28. [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks CW. Enteric bacterial growth rates in river water. Appl Microbiol. 1972;24:168–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill WR, Mulholland PJ, Marzolf ER. Stream Ecosystem Responses to Forest Leaf Emergence in Spring. Vol. 82. Hoboken: Wiley. https://www.jstor.org/stable/268023. 2001, 2306–19. [Google Scholar]

- Hill WR, Ryon MG, Schilling EM. Light limitation in a stream ecosystem: responses by primary producers and consumers. Ecology. 1995;76:1297–309. [Google Scholar]

- Izagirre O, Agirre U, Bermejo M et al. Environmental controls of whole-stream metabolism identified from continuous monitoring of Basque streams. J North Am Benthol Soc. 2008;27:252–68. [Google Scholar]

- Kamp A, De BD, Nitsch JL et al. Diatoms respire nitrate to survive dark and anoxic conditions. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011;2011:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi N, Madsen OS. Formation of ripples in erodible channels. J Geophys Res. 1985;90:7332–40. [Google Scholar]

- Koedooder C, Stock W, Willems A et al. Diatom-bacteria interactions modulate the composition and productivity of benthic diatom biofilms. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruskal JB, Wish M. Multidimensional scaling:. Sage University Papers: quantitative applications in the social sciences. Thousand Oaks: SAGE, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Kryvokhyzhyna M, Majdi N, Oprei A et al. Response of meiobenthos to migrating ripples in sandy lowland streams. Hydrobiologia. 2022;849:1905–21. [Google Scholar]

- Kuehn KA, Francoeur SN, Findlay RH et al. Priming in the microbial landscape: periphytic algal stimulation of litter-associated microbial decomposers. Ecology. 2014;95:749–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau YL, Liu D. Effect of flow rate on biofilm accumulation in open channels. Water Res. 1993;27:355–60. [Google Scholar]

- Lavaud J, Goss R. The peculiar features of non-photochemical fluorescence quenching in diatoms and brown algae. Advances in Photosynthesis and Respiration. Dordrecht: Springer, 2014, 421–43. [Google Scholar]

- Lear G, Anderson MJ, Smith JP et al. Spatial and temporal heterogeneity of the bacterial communities in stream epilithic biofilms. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2008;65:463–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leff L, Van Gray JB, Martí E et al. Aquatic biofilms and biogeochemical processes. In: Aquatic Biofilms: Ecology, Water Quality and Wastewater Treatment. Wymondham: Caister Academic Press, 2016, 89–108. [Google Scholar]

- Lenth R, Singmann H, Love J et al. Emmeans: estimated marginal means, aka least-squares means. Vol. 1. R Packag Version. CRAN, 2018, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtman ID, Baas JH, Amoudry LO et al. Bedform migration in a mixed sand and cohesive clay intertidal environment and implications for bed material transport predictions. Geomorphology. 2018;315:17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Marcarelli AM, Huckins CJ, Eggert SL. Sand aggradation alters biofilm standing crop and metabolism in a low-gradient Lake Superior tributary. J Great Lakes Res. 2015;41:1052–9. [Google Scholar]

- Marella TK, Bhattacharjya R, Tiwari A. Impact of organic carbon acquisition on growth and functional biomolecule production in diatoms. Microb Cell Fact. 2021;20:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean S. The stability of ripples and dunes. Earth Sci Rev. 1990;29:131–44. [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza-Lera C, Frossard A, Knie M et al. Importance of advective mass transfer and sediment surface area for streambed microbial communities. Freshwater Biol. 2017;62:133–45. [Google Scholar]

- Miller D. Abrasion effects on microbes in sandy sediments. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 1989;55:73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Moss AJ. Initiation and inhibition of the formation of asymmetrical sand ripples. J Geol Soc Aust. 1975;22:79–90. [Google Scholar]

- Murali A, Bhargava A, Wright ES. IDTAXA: a novel approach for accurate taxonomic classification of microbiome sequences. Microbiome. 2018;6:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutz M, Schlief J, Orendt C. Morphologische Referenzzustände für Bäche im Land Brandenburg. Vol. 3. Studien und Tagungsberichte Landesumweltamt Brand. Potsdam: Landesumweltamt Brandenburg, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa S, Cuthill IC. Effect size, confidence interval and statistical significance: a practical guide for biologists. Biol Rev. 2007;82:591–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JM, Logan BL, Kinzel PJ et al. Bedform response to flow variability. Earth Surf Process Landf. 2011;36:1938–47. [Google Scholar]

- Oksanen J, Blanchet FG, Kindt R et al. Community ecology package. R Packag version 2.6-4. CRAN, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Oprei A, Schreckinger J, Kholiavko T et al. Long-term functional recovery and associated microbial community structure after sediment drying and bedform migration. Front Ecol Evol. 2023;11:390. [Google Scholar]

- Packman AI, Brooks NH. Hyporheic exchange of solutes and colloids with moving bed forms. Water Resour Res. 2001;37:2591–605. [Google Scholar]

- Piqué G, Vericat D, Sabater S et al. Effects of biofilm on river-bed scour. Sci Total Environ. 2016;572:1033–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prieto DM, Devesa-Rey R, Rubinos DA et al. Biofilm formation on river sediments under different light intensities and nutrient inputs: a flume mesocosm study. Environ Eng Sci. 2016;33:250–60. [Google Scholar]

- Quast C, Pruesse E, Yilmaz P et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D590–6. 10.1093/nar/gks1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team . R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Found Stat Comput, Vienna, 2022.

- Rabení CF, Doisy KE, Zweig LD. Stream invertebrate community functional responses to deposited sediment. Aquat Sci. 2005;67:395–402. [Google Scholar]

- Raudkivi AJ. Ripples on stream bed. J Hydraul Eng. 1997;123:58–64. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson BYK, Beardall J, Raven JA. Adaptation of unicellular algae to irradiance : an analysis of strategies. In: The New Phytologist. Vol. 93. Hoboken: Wiley, 1983, 157–91. [Google Scholar]

- Rickard AH, McBain AJ, Stead AT et al. Shear rate moderates community diversity in freshwater biofilms. Appl Environ Microb. 2004;70:7426–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risse-Buhl U, Anlanger C, Kalla K et al. The role of hydrodynamics in shaping the composition and architecture of epilithic biofilms in fluvial ecosystems. Water Res. 2017;127:211–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risse-Buhl U, Arnon S, Bar-Zeev E et al. Streambed migration frequency drives ecology and biogeochemistry across spatial scales. WIREs Water. 2023;10. 10.1002/wat2.1632. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Risse-Buhl U, Felsmann K, Mutz M. Colonization dynamics of ciliate morphotypes modified by shifting sandy sediments. Eur J Protistol. 2014;50:345–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochex A, Godon JJ, Bernet N et al. Role of shear stress on composition, diversity and dynamics of biofilm bacterial communities. Water Res. 2008;42:4915–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roeselers G, Van Loosdrecht MCM, Muyzer G. Heterotrophic pioneers facilitate phototrophic biofilm development. Microb Ecol. 2007;54:578–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romaní AM, Amalfitano S, Artigas J et al. Microbial biofilm structure and organic matter use in Mediterranean streams. Hydrobiologia. 2013;719:43–58. [Google Scholar]

- Romaní AM, Guasch H, Balaguer MD. Aquatic Biofilms. Wymondham: Caister Academic Press Limited, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Romaní AM, Sabater S. Influence of algal biomass on extracellular enzyme activity in river biofilms. Microb Ecol. 2000;40:16–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheidweiler D, Mendoza-Lera C, Mutz M et al. Overlooked implication of sediment transport at low flow: migrating ripples modulate streambed phototrophic and heterotrophic microbial activity. Water Resour Res. 2021;57. 10.1029/2020WR027988. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt H, Thom M, Wieprecht S et al. The effect of light intensity and shear stress on microbial biostabilization and the community composition of natural biofilms. Res Rep Biol. 2018;9:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Schreckinger J, Mutz M, Mendoza-Lera C et al. Attributes of drying define the structure and functioning of microbial communities in temperate riverbed sediment. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwendel AC, Death RG, Fuller IC. The assessment of shear stress and bed stability in stream ecology. Freshwater Biol. 2010;55:261–81. [Google Scholar]

- Sekar R, Nair KVK, Rao VNR et al. Nutrient dynamics and successional changes in a lentic freshwater biofilm. Freshwater Biol. 2002;47:1893–907. [Google Scholar]

- Shi P, Shen H, Wang W et al. Habitat-specific differences in adaptation to light in freshwater diatoms. J Appl Phycol. 2016;28:227–39. [Google Scholar]

- Sigee DC. Freshwater Microbiology. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Streble H, Krauter D. Das Leben Im Wassertropfen: mikroflora Und Mikrofauna Des Süsswassers; Ein Bestimmungsbuch; Neu: biologische Gewässeranalyse. Stuttgart: Franckh-Kosmos, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland IW. Biofilm exopolysaccharides: a strong and sticky framework. Microbiology. 2001;147:3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teitelbaum Y, Shimony T, Saavedra Cifuentes E et al. A novel framework for simulating particle deposition with moving bedforms. Geophys Res Lett. 2022;49. 10.1029/2021GL097223. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thom M, Schmidt H, Gerbersdorf SU et al. Seasonal biostabilization and erosion behavior of fluvial biofilms under different hydrodynamic and light conditions. Int J Sediment Res. 2015;30:273–84. [Google Scholar]

- Tuchman NC, Schollett MA, Rier ST et al. Differential heterotrophic utilization of organic compounds by diatoms and bacteria under light and dark conditions. Hydrobiologia. 2006;561:167–77. [Google Scholar]

- Uehlinger U, Naegeli M, Fisher SG. A heterotrophic desert stream? The role of sediment stability. West North Am Nat. 2002;62:466–73. [Google Scholar]

- Valance A. Formation of ripples over a sand bed submitted to a turbulent shear flow. Eur Phys J B. 2005;45:433–42. [Google Scholar]

- Verdonschot PFM. Soft-bottomed lowland streams: a dynamic desert. SIL Proc. 2000;27:2577–81. [Google Scholar]

- Villanova V, Fortunato AE, Singh D et al. Investigating mixotrophic metabolism in the model diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2017;372:20160404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Berg K-HL, Hoef-Emden K, Birger M et al. Der Kosmos-Algenführer: süßwasseralgen Unter Dem Mikroskop: ein Bestimmungsbuch. Stuttgart: Kosmos, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wagenhoff A, Lange K, Townsend CR et al. Patterns of benthic algae and cyanobacteria along twin-stressor gradients of nutrients and fine sediment: a stream mesocosm experiment. Freshwater Biol. 2013;58:1849–63. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner H, Jakob T, Wilhelm C. Balancing the energy flow from captured light to biomass under fluctuating light conditions. New Phytol. 2006;169:95–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner K, Besemer K, Burns NR et al. Light availability affects stream biofilm bacterial community composition and function, but not diversity. Environ Microbiol. 2015;17:5036–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallbrink PJ. Quantifying the erosion processes and land-uses which dominate fine sediment supply to Moreton Bay, Southeast Queensland, Australia. J Environ Radioact. 2004;76:67–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wantzen KM, Blettler MCM, Marchese MR et al. Sandy rivers: a review on general ecohydrological patterns of benthic invertebrate assemblages across continents. Int J River Basin Manag. 2014;12:163–74. [Google Scholar]

- Wellnitz T, Rader RB. Mechanisms influencing community composition and succession in mountain stream periphyton: interactions between scouring history, grazing, and irradiance. J North Am Benthol Soc. 2003;22:528–41. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler B, Torchiano M. lmPerm: permutation Tests for Linear Models. R Packag Version 2.1.0. CRAN, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wimpenny J, Manz W, Szewzyk U. Heterogeneity in biofilms. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2000;24:661–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler JP, Cherry RS, Schlesinger WH. The Q10 relationship of microbial respiration in a temperate forest soil. Soil Biol Biochem. 1996;28:1067–72. [Google Scholar]

- Wolke P, Teitelbaum Y, Deng C et al. Impact of bed form celerity on oxygen dynamics in the hyporheic zone. Water. 2020;12:5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Wotton RS. The ubiquity and many roles of exopolymers (EPS) in aquatic systems. Sci Mar. 2004;68:13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ylla I, Borrego C, Romaní AM et al. Availability of glucose and light modulates the structure and function of a microbial biofilm: research article. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2009;69:27–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]