Abstract

Through a COVID-19 public health intervention implemented across sequenced research trials, we present a community engagement phased framework that embeds intervention implementation: (1) consultation and preparation, (2) collaboration and implementation, and (3) partnership and sustainment. Intervention effects included mitigation of psychological distress and a 0.28 increase in the Latinx population tested for SARS-CoV-2. We summarize community engagement activities and implementation strategies that took place across the trials to illustrate the value of the framework for public health practice and research. (Am J Public Health. 2024;114(S5):S396–S401. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2024.307669 )

INTERVENTION AND IMPLEMENTATION

We illustrate the application of a Community Engagement (CE) framework with a COVID-19 public health intervention implemented in 2-sequenced trials funded by the National Institutes of Health’s Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics–Underserved Populations (RADx-UP).1 The overarching goal of the NIH-funded intervention trials was to contribute to the scientific literature on public health interventions aiming to mitigate health disparities experienced by the Latinx population, with a focus on increasing SARS-CoV-2 testing. Latinxs are individuals with common heritage from Latin American countries.2,3 Community-engaged public health interventions were vital to reach all segments of the population, inclusive of racial and ethnic minorities, who fared worse than non-Latinx White individuals in COVID-19 infections and their health consequences in the United States and in Oregon.4,5

We use a translational case study approach6 to examine the evolution of an intervention aimed to increase SARS-CoV-2 testing and COVID-19 preventive behaviors among Latinx populations in Oregon, from its development, implementation in the community, and revision across research trials. The proposed CE framework is operative alongside existing CE theories,7 evaluation models, and empirical work to operationalize CE activities.8 Although the scientific literature on CE and intervention implementation has grown, and intersections between them exist, to our knowledge, there is no published framework that integrates implementation across the entire spectrum of CE. We address this gap with an introductory illustration of how CE can be integrated with intervention implementation phases9 and discrete implementation strategies10 that are empirically linked with implementation success.

PLACE, TIME, AND PERSONS

The foci of the public health intervention delivered in trials 1 and 2 were: (1) on-site SARS-CoV-2 testing, and (2) a health promotion intervention, Promotores de Salud (“health promoters”) that comprised culturally and trauma-informed community outreach prior to testing events, as well as COVID-19 health education promoting social distancing, mask wearing, hand washing, repeated testing, and vaccination during testing events. Promotores drawn from local communities conducted outreach—building relationships and advertising events—and delivered the intervention.11

Trial 1 included the development, implementation, and cluster randomized trial evaluation of the intervention offered in 36 testing sites that were geographically dispersed across the state, encompassing urban, rural, and frontier areas. Sites were geolocated to be in high-density Latinx population regions12 and randomized to intervention versus comparator study arms prior to trial 1 enrollment, which began in February 2021 and continued through August 2022. Trial 2 evaluated the comparative effectiveness on engagement in SARS-CoV-2 testing between 2 types of intervention site-events: (1) trial 1 geolocated sites, versus (2) site-events identified by community or governmental organizations (e.g., Mexican Consulate, Oregon Health Authority). Trial 2 commenced in September 2021 and completed enrollment in April 2023. Importantly, the public health guidance was updated to prioritize vaccination as a leading COVID-19 prevention strategy because vaccinations were already available.

PURPOSE

To advance public health intervention research to mitigate health disparities, such as the disproportionate COVID-19 cases among the Latinx population, this article highlights the value of integrating Implementation Science phased-frameworks and strategies in community-engaged public health practice and research with a translational perspective.

EVALUATION AND ADVERSE EFFECTS

Across trials 1 and 2, 6,106 individuals were tested and 974 individuals received the intervention. Results of trial 1 attest to the effectiveness of outreach to the Latinx population. Relative to comparator sites, 3.8 times more Latinx individuals attended testing events at intervention sites, representing a 0.28 increase in the proportion of the Latinx population tested.13 The Promotores de Salud intervention did not significantly increase COVID-19 preventive behaviors. However, accounting for baseline distress, participants who received the intervention reported lower psychological distress at follow-up than individuals who did not (d = 0.15).14 This is notable because psychological distress was heightened during the pandemic and contributed to worse COVID-19 prognoses. Evaluation of trial 2 (under review) suggested that geolocated sites had more tests collected in the context of longer drive times (d = .23) and had more tests in communities with higher density Latinx population (d = 0.29) than partner-located sites. To date there have been no adverse events.

Community Engagement and Implementation Phased-Framework

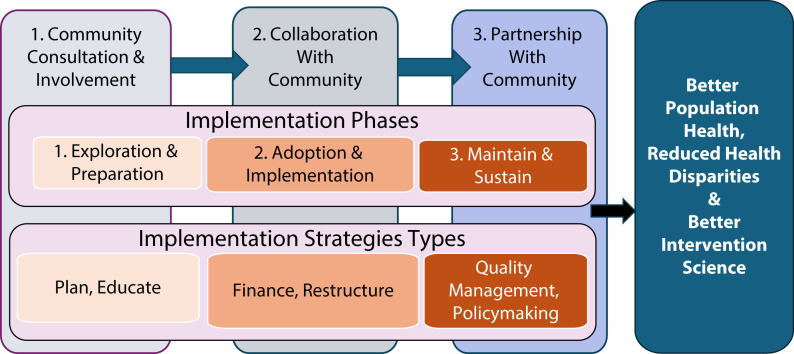

Drawing on the Clinical and Translational Clinical Science Awards’ CE continuum,15 we present a framework to examine the trials within three sequenced phases: (1) community consultation and involvement, (2) collaboration with community, and (3) partnership with community (see Figure 1). CE is defined as “the process of working collaboratively with groups of people who are affiliated by geographic proximity, special interest, or similar situations with respect to issues affecting their well-being”.15 The roles and relationships of community groups with implementation research teams progress from limited consultations as a starting point in a continuum (phase 1), to partnerships with shared leadership and decision making as a goal (phase 3); collaborative relationships with two-way communication and mutual benefits are a pivotal link between them (phase 2).

FIGURE 1—

Three-phase Community Engagement Framework Integrating Intervention Implementation

The framework postulates that each CE phase can align closely with both intervention implementation phases9 and corresponding implementation strategies.10 Moreover, each subsequent phase signifies progress in both CE and intervention implementation relative to the prior phase (see Figure 1). Illustratively, initial consultation with community groups corresponds to initial exploration and preparation for intervention development, with implementation strategies such as planning and information sharing (phase 1). Community consultation evolves into collaborations, as intervention progresses to initial adoption (implementation) with implementation strategies such as restructuring of workflows (phase 2). In collaborations or partnerships with community, interventions are more likely to enter maintenance and long-term sustainment (phase 3) with implementation strategies such as adjustment of the financing of the intervention, quality management, and attending to policy contexts.10

Community Engagement and Implementation

Consistent with phase 1, during trial 1, preparation included the formation of teams specializing in community engagement and implementation science. A multidisciplinary environment representing biological, behavioral, public health, and data sciences energized scientific investigators and staff. Initial consultation and involvement with community across state, regional and local levels was expedited by the COVID-19 health crisis; working groups including researchers, community groups, and stakeholders, quickly coalesced. Community advisories were also formed. Notably, there was robust representation of individuals who belong to - and with expertise of - Latinx populations. Hence, it was possible to expedite input from community members to make research and intervention materials, inclusive of promotores de salud, culturally and linguistically appropriate, as well as to optimize community sites to reach Latinx populations following initial geolocation. With accelerated funding, implementation timetables for intervention development and initial implementation were expedited, thus exploration and preparation implementation phases were abbreviated. (See Box 1 for illustrative CE activities, implementation strategies, and challenges).

BOX 1—

Illustrative Examples of Community Engagement Activities and of Implementation Strategies in Research Trials 1 and 2 That Correspond to Phases 1 and 2 of the Community Engagement and Intervention Implementation Phased Framework

| Phase 1: Community Consultation and Involvement (Exploration & Preparation; Research Trial 1) | Phase 2: Collaboration With Community (Initial Adoption-Implementation; Research Trials 1 and 2) |

| Illustrative Community Engagement Activities | |

|

|

| Illustrative Discrete Implementation Strategies | |

Planning:

|

|

| Illustrative Challenges | |

|

|

Note. SARS-CoV-2 = severe-acute-respiratory-syndrome-related coronavirus 2.

Consistent with transitioning to phase 2, ongoing communication and coordination of the SARS-CoV-2 testing events at local community sites took place among research implementers, state and regional health departments, community groups, and stakeholders. The implementation team and the Oregon Health Authority procured contracts to offer testing, vaccination, and COVID-19 health promotion to specific populations in the state, outside of these research trials. Collaboration shaped trial 2’s comparative effectiveness design. Ongoing consultation with the community advisory, state health officials, and community-based organizations resulted in the production of the most current and appropriate health guidance during each stage of the pandemic, inclusive of prioritization of vaccinations when they became available. Updating recommendations also facilitated ongoing cultural and linguistic responsiveness in health promotion messaging. Notably, Latinx staff and Latinx subject matter expertise were maintained despite overall workflow changes and staff turnover.

SCALABILITY

The sustainment of an intervention delivered across multiple state region sites focused on increasing SARS-CoV-2 testing and mitigating its spread through preventive behaviors is no longer an optimal public health goal because the end of the public health emergency shifted COVID-19 priorities. However, the intervention was sustained beyond the time and goals of trial 1 so that it would promote vaccination and evaluate community versus geolocated sites in trial 2. A third research trial was funded to promote self-administered SARS-CoV-2 testing and to address the high level of psychological distress in Latinx community observed in the prior trials. Trial 3 commenced in November 2022 and is in progress.

PUBLIC HEALTH SIGNIFICANCE

The success of the intervention developed and maintained across sequenced NIH-research trials is evidenced in the significant and notable increase in SARS-CoV-2 testing and in the amelioration of psychological distress among Latinxs across multiple state regions and sites. These findings are consistent with mounting evidence of the effectiveness of CE in reducing health disparities.7 We introduce a phase-based framework that aligns both community engagement and intervention implementation progress in spectrums culminating in partnerships with, and sustainable interventions in, the community; we illustrate its application with a translational case study of the research trials. The two-pronged focus on community engagement and intervention implementation is a promising approach to embed community feedback and to collaborate and partner with the community to develop, implement, and sustain effective, feasible, and scalable public health interventions in community settings with high population reach, inclusive of populations with disproportionately adverse health outcomes such as Latinxs in the COVID-19 pandemic.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Research reported in this publication, and manuscript preparation, were supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Numbers P50 DA048756-04S2 (MPIs: LD Leve, WA Cresko, DS DeGarmo) and P50DA048756-03S3 (MPIs: LD Leve, WA Cresko, DS DeGarmo), and by National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparitiesof NIH under Award Number U01MD018311 (PI:DeGarmo).

We thank all the community-based organizations (CBOs) and local and state health departments that closely collaborated and contributed to the success of the Oregon Saludable Juntos Podemos (OSJP) project. CBO promotores and administrators, specifically, were vital intervention agents. We also thank the entire OSJP research team, particularly Kelsey Van Brocklin, Ashley Nash, Sven Halvorson, and Llewellyn Fernandes, as well as project co-principal investigator William A. Cresko. Lastly, we extend special thanks to the OSJP Community Scientific Advisory Board (CSAB) for their crucial guidance throughout the project. CSAB members include Jorge Ramírez García (Chair), Lisandra Guzman, Juan Diego Ramos, Kristin Yarris, Maria Castro, Jacqueline McCall, Abe Vega, and Oscar Becerra.

This article is based on a conference presentation: Ramírez García JI, Cioffi CC, De Anda S, et al. Embedding community engagement in the implementation of a public health intervention trial to mitigate COVID-19 disparities among Latinxs in 38 community sites in Oregon. Presented at: 15th Annual Conference on the Science of Dissemination and Implementation in Health; December 2022; Washington, D.C.

Note. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The funding body had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data or in writing the manuscript.

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifiers: NCT04793464; NCT05082935; NCT05910879

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

All study activities were approved by the University of Oregon institutional review board. All study participants provided written or digital informed consent.

REFERENCES

- 1.TrombergBJ , SchwetzTA , Pérez-StableEJ , et al. Rapid scaling up of COVID-19 diagnostic testing in the United States—The NIH RADx initiative. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(11):1071–1077. 10.1056/NEJMsr2022263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramírez GarcíaJI. Integrating Latina/o ethnic determinants of health in research to promote population health and reduce health disparities. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2019;25(1): 21–31. 10.1037/cdp0000265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D’AgostinoEM , Ramírez García JI, BakkenSR , et al. Examining COVID-19 testing and vaccination behaviors by heritage and linguistic preferences among Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish RADx-UP participants. Prev Med Rep. 2023;35:102359. 10.1016/j.pmedr.2023.102359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MackeyK , AyersCK , KondoKK , et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in COVID-19–related infections, hospitalizations, and deaths. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(3):362–373. 10.7326/M20-6306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oregon Health Authority. Oregon COVID-19 Case Demographics and Disease Severity Statewide. Tableau Public. Available at: https://bit.ly/3xVp5pv . Accessed August 31, 2023.

- 6.DodsonSE , KukicI , SchollL , PelfreyCM , TrochimWM. A protocol for retrospective translational science case studies of health interventions. J Clin Transl Sci. 2020;5(1):e22. 10.1017/cts.2020.514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.WallersteinN , DuranB. Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: the intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(S1):S40–S46. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.184036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DuranB , OetzelJ , MagaratiM , et al. Toward health equity: a national study of promising practices in community-based participatory research. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2019;13(4): 337–352. 10.1353/cpr.2019.0067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MoullinJC , DicksonKS , StadnickNA , RabinB , AaronsGA. Systematic review of the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment (EPIS) framework. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):1-16. 10.1186/s13012-018-0842-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.PowellBJ , WaltzTJ , ChinmanMJ , et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci. 2015; 10(1):1-14. 10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.BuddEL , McWhirterEH , De AndaS , et al. Development and design of a culturally tailored intervention to address COVID-19 disparities among Oregon’s Latinx communities: a community case study. Front Public Health. 2022;10:962862. Doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.962862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.SearcyJA , CioffiCC , TavalireHF , et al. Reaching Latinx communities with algorithmic optimization for SARS-CoV-2 testing locations. Prev Sci. 2023;24(6):1249–1260. Doi.org/10.1007/s11121-022-01478-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeGarmoDS , De AndaS , CioffiCC , et al. Effectiveness of a COVID-19 testing outreach intervention for Latinx communities: a cluster randomized trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(6): e2216796. Doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.16796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De AndaS , BuddEL , HalvorsonS , et al. Effects of a health education intervention for COVID-19 prevention in Latinx communities: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Am J Public Health. 2022;112(S9):S923–S927. Doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2022.307129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCloskeyDJ , Aguilar-GaxiolaS , MichenerJL , et al. , Principles of Community Engagement, 2nd ed. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. National Institutes of Health; 2011. Accessed August 31, 2021. Available at: https://atsdr.cdc.gov/communityengagement/pdf/PCE_Report_508_FINAL.pdf . [Google Scholar]