Abstract

Introduction

The ObserVational survey of the Epidemiology, tReatment and Care Of MigrainE (OVERCOME) European Union (EU) is part of an overarching population-based study program that also includes the United States and Japan. Here, we report data on the migraine/severe headache burden and the use of acute medication and healthcare resources in Spain and Germany.

Methods

OVERCOME (EU) was an online, non-interventional, cross-sectional survey conducted in adults in Spain and Germany between October 2020 and February 2021. A total migraine cohort was established based on health survey participants who reported headache/migraine in the last 12 months AND identified as having migraine based on modified International Classification of Headache Disorders, third edition criteria OR self-reported physician diagnosis. Data were analyzed for the total migraine cohort and the subcohort with moderate to severe headache attacks, with average pain severity ≥ 5 points, pain duration ≥ 4 h, and at least moderate disability due to migraine [Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) score ≥ 11] over the past 3 months.

Results

Pain of moderate or severe intensity was the most frequent symptom in the total migraine cohort (n = 19,103/20,756; 92.0%). Proportions of participants reporting severe disability (MIDAS Grade IV), poorer quality of life (QoL; Migraine-Specific QoL Questionnaire), and higher interictal burden (Migraine Interictal Burden Scale-4), generally increased with number of headache days (HDs)/month. Most participants (92.5%) reported current acute migraine/severe headache medication use, although only 39.0% were using triptans. In the moderate to severe attacks subcohort (n = 5547), 48.4% were using triptans, with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs the most common acute medication. The moderate to severe attacks subcohort also reported poorer QoL and greater pain and disability with increasing HDs/month, although severe interictal burden was reported for ~ 60% of participants regardless of HDs/month. Treatment satisfaction (six-item migraine Treatment Optimization Questionnaire) in those using triptans was generally poor in both total and subcohorts.

Conclusion

High migraine-related burden levels were reported, despite use of acute medication. Although triptans are recommended for moderate to severe migraine attacks in Spanish and German guidelines, less than half of participants were using triptans; treatment satisfaction in those using triptans was generally poor. New tailored treatment options may help address unmet needs in current acute treatment.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40122-024-00589-3.

Keywords: Migraine, Severe headache, Migraine symptoms, Burden of migraine, Acute treatment patterns, Treatment satisfaction

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Migraine is associated with disability, pain, lost productivity, healthcare utilization, and reduced quality of life. |

| As most published real-world migraine treatment and burden data are from observational or registry-based studies, which focus on healthcare settings, they will not capture the experiences of the many people with migraine who do not seek professional medical care. |

| What did the study ask?/What was the hypothesis of the study? |

| The population-based ObserVational survey of the Epidemiology, tReatment and Care Of MigrainE (OVERCOME) European Union (EU) survey aimed to further understand current treatment patterns, and the burden and unmet needs of people with migraine/severe headache in Spain and Germany; here, we report data regarding the use of acute medication and healthcare resources. |

| What was learned from the study? |

| Our study found high migraine-related burden levels, despite the use of acute medication; the proportions of participants reporting severe disability, poorer quality of life, and higher interictal burden generally increased with the number of headache days/month. |

| Although triptans are recommended for moderate to severe migraine attacks in Spanish and German guidelines, less than half of participants (39.0% in the overall total migraine cohort, 48.4% of a sub-cohort with moderate to severe attacks) were using triptans, and treatment satisfaction in those using triptans was generally poor. |

| New tailored treatment options may help address unmet needs in current acute treatment. |

Introduction

Migraine is a debilitating neurological condition with an overall prevalence of approximately 15% in Europe [1], and 1-year prevalences of 12.6% in Spain [2] and 16.6% in Germany [3]. Reported prevalence estimates vary between studies, possibly due to differences in study design and/or inclusion criteria [4, 5]. Migraine is more prevalent in females (17.6%) than males (8%) in Europe [1], and is most common between the ages of 15 and 49 years, with the highest prevalence (~ 30%) in females aged 35–39 years [6].

The World Health Organization ranks migraine as the second leading cause of disability overall (based on years lived with disability), and the leading cause of disability in women aged 15–49 years [7]. The pain, physical impairment, and nausea/vomiting associated with migraine attacks, along with the interictal burden and unpredictability of attacks, can result in significant disruption to daily life, missed school/work days, medication overuse, lower health-related quality of life (HRQoL), increased healthcare utilization, and stigma [8–14]. Lost productivity due to migraine in Europe has been estimated to cost ~ 110 billion euros per year [13].

Even though people with migraine may visit a range of healthcare providers (HCPs), many have never seen a physician and use over-the-counter (OTC) or even no medication [14–16]. Triptans are the recommended first-choice treatment for moderate to severe migraine attacks in both Spanish and German guidelines [17, 18], and are available on prescription or OTC in Germany but are prescription-only in Spain. Although the reported proportions of patients using triptans vary between countries, they are generally reported as low [19]. On a general migraine patient population basis, the Eurolight study reported triptan use rates between 3.4% (Lithuania) and 22.4% (Spain, workplace setting), with 11.0% reported for Germany [19]. However, higher rates have been reported for studies among members of lay headache organizations [19].

Most published data on real-world migraine treatment and burden are from observational or registry-based studies, which focus on healthcare settings. However, as many people do not seek professional medical care for migraine, their experiences will not be captured in these studies. New population-based studies are required to further understand current treatment patterns, and the burden and unmet needs of people with migraine in Europe and globally. The ObserVational survey of the Epidemiology, tReatment and Care Of MigrainE (OVERCOME) European Union (EU) is part of an overarching study program that also includes the United States and Japan [20–22]; OVERCOME (EU) reports data from Spain and Germany.

Here, we report the data on the burden of migraine/severe headache and the use of acute medication and healthcare resources in Spain and Germany. The use of preventive medication by participants in this study is reported elsewhere [23]. We also report findings of a subcohort analysis of participants with moderate to severe headache attacks to determine the burden in this population, and whether these people are using triptans in line with Spanish and German guidelines [17, 18].

Methods

Study Design

OVERCOME (EU) was an online, non-interventional, cross-sectional, observational survey conducted in adults (aged ≥ 18 years) in Spain and Germany between October 2020 and February 2021. Full details of the study design and methods, including the survey instrument used, are published elsewhere [23]. Briefly, participants registered in existing opt-in online survey panels [Kantar Profiles (Lightspeed) global panel and its partners] [24] were invited to participate in a health survey without knowledge of the specific health topic. This study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments. Ethical review board approval for the study was granted by the Marqués de Valdecilla University Hospital (Spain) and participants were required to provide informed consent prior to commencing the study by selecting “I agree to participate” on the online form. All survey respondents provided informed consent and all data were anonymized before analysis.

Three phases were used to establish the migraine cohort [23]. In phase I, a random sample was selected based on pre-specified demographics (e.g., age and sex) to ensure (to the extent possible) that the data collected were representative of the Spanish and German adult population. In phase II, respondents were assigned to two cohorts, a migraine cohort and a non-migraine control cohort. The migraine cohort included people with a reported headache/migraine (any type) in the last 12 months AND identified as having migraine based on the modified International Classification of Headache Disorders, third edition (ICHD-3) screening criteria [25] OR self-reported physician diagnosis of migraine (i.e., where a participant reported having received this diagnosis from a medical professional). In phase III, participants in the migraine cohort were invited to complete further questions to collect data on demographics, clinical features of migraine, patient-reported outcomes, and the use of medication.

Data were analyzed for the total migraine cohort and for the subcohort with moderate to severe headache attacks over the past 3 months (moderate to severe attacks subcohort). Moderate to severe headache attacks were defined as being of average pain severity ≥ 5 points [based on the Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) question on pain severity], pain duration ≥ 4 h, AND moderate or severe disability (MIDAS score ≥ 11) due to migraine.

Study Objectives and Analyses

The primary objectives of the OVERCOME (EU) study were to understand diagnosis, barriers to treatment, and treatment patterns of people with migraine in Spain and Germany. A summary of the main categories of survey questions has been published previously [23].

The analyses reported here are focused on symptoms, duration of migraine/severe headache, pain severity, migraine-related disability, and burden/quality of life (QoL), together with HCP visits, acute migraine medication treatment patterns (including the use of acute treatment in combination with preventive medication), and treatment satisfaction.

Migraine-Specific Assessments

Migraine-related data were assessed using patient-reported outcome measures or by asking specific questions to participants. Migraine-related disability was assessed using the MIDAS scale [26–28]. MIDAS is a brief, self-administered, questionnaire containing five questions that quantifies headache disability based on the number of days a person has missed or had reduced productivity at work, home, or social settings over the past 3 months. Two additional questions about the number of headaches and average associated pain level are not used in scoring but can help physicians in better understanding the clinical features of headache for each affected person [27]. Disability grades are then assigned based on these number of days, with higher scores indicating more severe disability: Grade I = little or no disability (MIDAS score 0–5); Grade II = mild (score 6–10); Grade III = moderate (score 11–20); and Grade IV = severe (score ≥ 21). The MIDAS instrument is considered reliable and valid and is correlated with clinical judgment regarding the need for medical care [29, 30]. Spanish and German versions of the MIDAS instrument have also been validated [31, 32]. Pain severity was assessed through the specific question of the MIDAS: “On a scale of 0 to 10 (where 0 = no pain at all and 10 = pain as bad as it can be), on average how painful are your migraine or severe headaches?”.

Headache duration was assessed through another specific survey question: “When you have a migraine or severe headache, how long does it usually last?”.

Satisfaction with migraine treatment was assessed using the six-item migraine Treatment Optimization Questionnaire (mTOQ-6) [33, 34]. The mTOQ-6 is a validated, self-administered questionnaire that assesses the efficacy of current acute migraine treatment, and asks questions about the medications the patient is currently using to treat headaches (recall period 3 months). The items assess the domains of quick return to function, 2-h pain free, sustained 24-h pain relief, tolerability, comfortable making plans, and perceived control. Response options utilize a Likert-type scale of “never” or “rarely” (scored as 0), “less than half the time” (scored as 1), or “half the time or more” (scored as 2). Treatment efficacy is categorized as “very poor” = 0, “poor” = 1–5, “moderate” = 6–7, and “maximum” = 8.

Health status (i.e., physical and emotional limitations of specific concern to individuals suffering from migraine headaches) was assessed using the Migraine-Specific QoL Questionnaire (MSQ) Version 2.1. This instrument consists of 14 items that address three domains: (1) Role Function-Restrictive; (2) Role Function-Preventive; and (3) Emotional Function [35]. Raw scores for each dimension are computed as a sum of item responses, the collective sum providing a total raw score that is converted to a 0–100 scale, with higher scores indicating a better HRQoL. The instrument was designed with a 4-week recall period, and is considered reliable, valid, and sensitive to change in migraine [35, 36].

The burden related to headache in the time between attacks was measured using the Migraine Interictal Burden Scale-4 (MIBS-4) instrument. The MIBS-4 consists of four items that address disruption at work and school, diminished family and social life, difficulty planning, and emotional difficulty. The questionnaire specifically asks about the effect of the disease over the past 4 weeks on days without a headache attack. Each response has an associated numerical score, with the sum across all four items resulting in a total score ranging from 0 to 12. The level of interictal burden is categorized into the following: 0 for none, 1–2 mild, 3–4 moderate, and ≥ 5 severe [12, 37].

Statistical Analyses

Data from the total migraine cohort, moderate to severe attacks subcohort, and specific subgroups [based on different frequencies of headache days per month (HDs/month)] were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Continuous variables are reported as means with standard deviations (SDs), or medians and ranges, as appropriate. Categorical variables are summarized as frequencies and percentages. SAS Version 9.4 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) was used to undertake all analyses.

Results

Total Migraine Cohort

Participants

A total of 20,756 participants were included in the total OVERCOME (EU) migraine cohort (Table 1). Respondents had a mean age of 40.4 years, a mean age at diagnosis of 24.2 years, and 60.3% were female. The proportion of participants with comorbidities, especially anxiety and depression, generally increased numerically with the number of HDs/month. Severe disability (MIDAS Grade IV) was more commonly reported in participants with a greater number of HDs/month.

Table 1.

Participant sociodemographic and migraine-related clinical characteristics (total migraine cohort)

| Total (N = 20,756) | HDs/month | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–3 (N = 13,759) | 4–7 (N = 4203) | 8–14 (N = 1730) | ≥ 15 (N = 1064) | ||

| Mean (SD) age, years | 40.4 (13.5) | 40.1 (13.5) | 40.7 (13.3) | 41.2 (13.5) | 42.2 (13.9) |

| Mean (SD) age at migraine diagnosis, years | 24.2 (10.8) | 24.0 (10.6) | 24.4 (11.0) | 25.1 (11.0) | 24.3 (11.6) |

| Female, n (%) | 12,512 (60.3) | 7,846 (57.0) | 2717 (64.6) | 1177 (68.0) | 772 (72.6) |

| ICHD-3 criteria met, n (%) | 18,987 (91.5) | 12,541 (91.1) | 3872 (92.1) | 1611 (93.1) | 963 (90.5) |

| Previously diagnosed with migraine by healthcare provider, n (%) | 11,948 (57.6) | 7269 (52.8) | 2805 (66.7) | 1169 (67.6) | 705 (66.3) |

| Most frequently reported health conditions (≥ 20% in total migraine cohort), n (%) | |||||

| Allergies/hay fever | 8043 (38.8) | 5161 (37.5) | 1724 (41.0) | 716 (41.4) | 442 (41.5) |

| Anxiety | 5430 (26.2) | 3257 (23.7) | 1204 (28.6) | 571 (33.0) | 398 (37.4) |

| High cholesterol/lipids | 5122 (24.7) | 3217 (23.4) | 1071 (25.5) | 502 (29.0) | 332 (31.2) |

| Depression | 4978 (24.0) | 2788 (20.3) | 1148 (27.3) | 592 (34.2) | 450 (42.3) |

| Hypertension | 4875 (23.5) | 3034 (22.1) | 1004 (23.9) | 496 (28.7) | 341 (32.0) |

| MIDAS gradea, total migraine cohort, n (%) | |||||

| I—little or no disability | 8177 (39.4) | 6689 (48.6) | 1043 (24.8) | 291 (16.8) | 154 (14.5) |

| II—mild disability | 3976 (19.2) | 2988 (21.7) | 728 (17.3) | 180 (10.4) | 80 (7.5) |

| III—moderate disability | 4004 (19.3) | 2438 (17.7) | 1036 (24.6) | 382 (22.1) | 148 (13.9) |

| IV—severe disability | 4599 (22.2) | 1644 (11.9) | 1396 (33.2) | 877 (50.7) | 682 (64.1) |

HDs headache days, ICHD-3 International Classification of Headache Disorders, third edition, MIDAS Migraine Disability Assessment, SD standard deviation

aHigher MIDAS scores indicate greater disability: Grade I = score 0–5; Grade II = score 6–10; Grade III = score 11–20; Grade IV = score ≥ 21

Symptoms, Duration, Pain Severity, and Burden of Migraine/Severe Headache

Pain of moderate or severe intensity was the most frequent migraine symptom, reported by 92.0% of participants in the total migraine cohort; other frequently reported symptoms are presented in Table 2. The proportion of participants reporting symptoms generally increased with the number of HDs/month. Most migraine/severe headache attacks were of 4–71 h duration, although around 1 in 10 participants in the ≥ 15 HDs/month group reported headache durations of ≥ 72 h (Table 3). The mean (SD) pain severity score in the total migraine cohort was 6.2 (1.9). Pain intensity increased numerically with a greater number of HDs/month.

Table 2.

Most frequently reported (≥ 70% in total migraine cohort) migraine symptoms (total migraine cohort)

| Total (N = 20,756) | HDs/month | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–3 (N = 13,759) | 4–7 (N = 4203) | 8–14 (N = 1730) | ≥ 15 (N = 1064) | ||

| Most frequently reported symptomsa (≥ 70% in total migraine cohort), n (%) | |||||

| Pain has moderate or severe intensity | 19,103 (92.0) | 12,445 (90.4) | 3976 (94.6) | 1660 (96.0) | 1022 (96.1) |

| Sound is bothersome | 17,366 (83.7) | 11,286 (82.0) | 3640 (86.6) | 1505 (87.0) | 935 (87.9) |

| Pain is pounding, pulsating or throbbing | 17,243 (83.1) | 11,146 (81.0) | 3679 (87.5) | 1505 (87.0) | 913 (85.8) |

| Light is bothersome | 16,896 (81.4) | 11,004 (80.0) | 3530 (84.0) | 1459 (84.3) | 903 (84.9) |

| Pain worse on just one side | 15,926 (76.7) | 10,125 (73.6) | 3430 (81.6) | 1457 (84.2) | 914 (85.9) |

| Pain is made worse by routine activities such as walking or climbing stairs | 15,040 (72.5) | 9686 (70.4) | 3218 (76.6) | 1319 (76.2) | 817 (76.8) |

HDs headache days

aSymptoms occurring with a Migraine Symptom Severity Score of ≥ 3 less than half of the time or more

Table 3.

Duration of migraine/severe headache (total migraine cohort)

| Total (N = 20,756) | HDs/month | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–3 (N = 13,759) | 4–7 (N = 4203) | 8–14 (N = 1730) | ≥ 15 (N = 1064) | ||

| When you have a migraine or severe headache, how long does it usually last? n (%) | |||||

| < 4 h | 7853 (37.8) | 5838 (42.4) | 1271 (30.2) | 511 (29.5) | 233 (21.9) |

| 4–71 h | 12,458 (60.0) | 7773 (56.5) | 2826 (67.2) | 1155 (66.8) | 704 (66.2) |

| ≥ 72 h | 445 (2.1) | 148 (1.1) | 106 (2.5) | 64 (3.7) | 127 (11.9) |

| Average pain severity (according to MIDAS) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 6.2 (1.9) | 5.9 (2.0) | 6.6 (1.6) | 6.9 (1.6) | 7.2 (1.6) |

HDs headache days, MIDAS Migraine Disability Assessment, SD standard deviation

Participants with a higher number of HDs/month also reported poorer QoL and higher interictal burden. Mean (SD) MSQ Role Function-Restrictive scores were 47.5 (21.5) in participants with ≥ 15 HDs/month, compared with 67.2 (21.3) in those with 0–3 HDs/month. The overall proportion of participants reporting moderate interictal burden (MIBS-4) was 12.6%, with little variation according to HDs/month [range 12.3% (8–14 HDs/month) to 13.8% (≥ 15 HDs/month)], whereas severe interictal burden increased with the number of HDs/month, from 41.2% of participants with 0–3 HDs/month to 57.8% of those with ≥ 15 HDs/month.

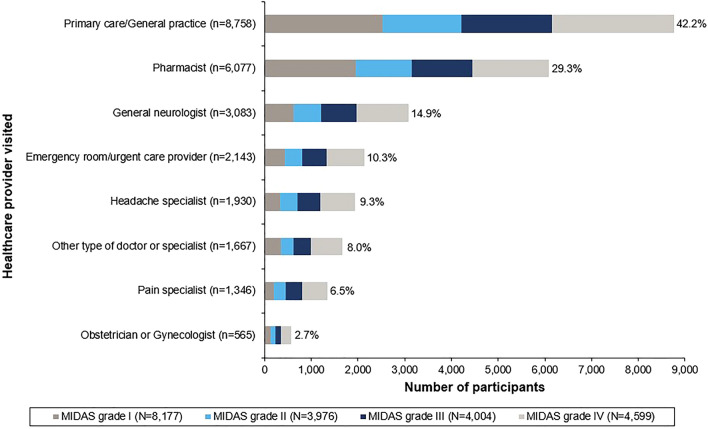

HCP Visits

Just over half of visits [mean proportion of total HCP visits per participant: 52.5% (SD: 37.9%)] to an HCP in the past 12 months were due to migraine/severe headache. Primary care/general practice was the service accessed by most participants (42.2%) for migraine/severe headache, followed by the pharmacist (29.3%; Fig. 1), although one in ten participants (10.3%) contacted an emergency service/urgent care provider. Participants with higher MIDAS grades were more likely to visit specialists or emergency care, whereas those with lower grades were more likely to visit a pharmacist or primary care/general practice.

Fig. 1.

Healthcare providers visited for migraine or severe headaches at least once in the prior 12 months (total migraine cohort; N = 20,756). Higher MIDAS scores indicate greater disability: I = score 0–5; II = score 6–10; III = score 11–20; IV = score ≥ 21. MIDAS Migraine Disability Assessment

Acute Migraine Treatment Patterns and Treatment Satisfaction

Most participants (92.5%; 19,207/20,756) reported that they were currently using acute migraine/severe headache medication, with a mean of 4.9 (SD: 4.0) current acute medications per participant in the total migraine cohort (Table 4). The most common categories of acute medication were OTC analgesics, followed by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) on prescription, and paracetamol. Fewer than half (39.0%) of participants currently using acute migraine medication were using triptans; the use of triptans was generally consistent across subgroups based on HDs/month but was slightly lower in people with 0–3 HDs/month (36.2%) compared with those with 4–7 (44.6%), 8–14 (45.1%), or ≥ 15 (41.4%) HDs/month.

Table 4.

Current acute migraine/severe headache medication use in participants using acute migraine/severe headache medications (total migraine cohort)

| Total (N = 19,207) | HDs/month | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–3 (N = 12,569) | 4–7 (N = 3989) | 8–14 (N = 1659) | ≥ 15 (N = 990) | ||

| Number of current acute medications per participant | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 4.9 (4.0) | 4.6 (3.7) | 5.3 (4.2) | 5.6 (4.5) | 5.6 (5.0) |

| Median (IQR) | 4.0 (2.0–6.0) | 4.0 (2.0–6.0) | 4.0 (2.0–7.0) | 4.0 (3.0–7.0) | 4.0 (2.0–7.0) |

| Number of participants using current acute medications per category, n (%) | |||||

| Triptansa | 7493 (39.0) | 4554 (36.2) | 1780 (44.6) | 749 (45.1) | 410 (41.4) |

| Ergot alkaloidsb | 412 (2.1) | 255 (2.0) | 88 (2.2) | 50 (3.0) | 19 (1.9) |

| NSAIDs (on prescription) | 10,647 (55.4) | 6655 (52.9) | 2349 (58.9) | 1033 (62.3) | 610 (61.6) |

| Paracetamol (prescription or OTC) | 10,237 (53.3) | 6657 (53.0) | 2165 (54.3) | 893 (53.8) | 522 (52.7) |

| OTC analgesicsc | 13,532 (70.5) | 8884 (70.7) | 2873 (72.0) | 1154 (69.6) | 621 (62.7) |

| Other prescription drugs | 7094 (36.9) | 4199 (33.4) | 1614 (40.5) | 764 (46.1) | 517 (52.2) |

| Other OTC drugs | 2921 (15.2) | 1695 (13.5) | 676 (16.9) | 340 (20.5) | 210 (21.2) |

| Suppositoriesd (prescription or OTC) | 6042 (31.5) | 4104 (32.7) | 1203 (30.2) | 488 (29.4) | 247 (24.9) |

| Number of participants using current preventive medication for migraine/severe headache, n (%) | |||||

| Current use | 4710 (22.7) | 2932 (21.3) | 1009 (24.0) | 449 (26.0) | 320 (30.1) |

| Combinations of current acute and preventive medications | |||||

| Number of participants using current preventive medication combined with: n (%)e | |||||

| Any current acute medication | 4598 | 2852 | 993 | 444 | 309 |

| Triptansa | 3611 (78.5) | 2260 (79.2) | 795 (80.1) | 346 (77.9) | 210 (68.0) |

| Ergot alkaloidsb | 280 (6.1) | 177 (6.2) | 60 (6.0) | 29 (6.5) | 14 (4.5) |

| NSAIDs (on prescription) | 3536 (76.9) | 2168 (76.0) | 777 (78.2) | 354 (79.7) | 237 (76.7) |

| Paracetamol (prescription or OTC) | 1954 (42.5) | 1101 (38.6) | 490 (49.3) | 229 (51.6) | 134 (43.4) |

| OTC analgesicsc | 3149 (68.5) | 1993 (69.9) | 692 (69.7) | 291 (65.5) | 173 (56.0) |

| Other prescription drugs | 2270 (49.4) | 1300 (45.6) | 526 (53.0) | 247 (55.6) | 197 (63.8) |

| Other OTC drugs | 561 (12.2) | 276 (9.7) | 143 (14.4) | 87 (19.6) | 55 (17.8) |

| Suppositoriesd (prescription or OTC) | 3383 (73.6) | 2314 (81.1) | 666 (67.1) | 260 (58.6) | 143 (46.3) |

HDs headache days, IQR interquartile range, NSAID nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, OTC over-the-counter, SD standard deviation

aTriptans are available on prescription or OTC in Germany but are prescription-only in Spain

bErgot alkaloids are only reimbursed in Germany

ce.g., aspirin and loxoprophen

dAny suppository used to treat or relieve migraine or severe headache (data were not analyzed according to the type of suppository used). Sumatriptan is available as a suppository in Germany but not in Spain

ePercentages are based on the number of participants taking each class of preventive medication combined with any current acute medication

Triptan use was more common in participants using preventive migraine medication, with 78.5% of those using current preventive medication using triptans (Table 4; Supplementary Table S1). NSAIDs on prescription, OTC analgesics, and suppositories were also commonly used in combination with preventive medication.

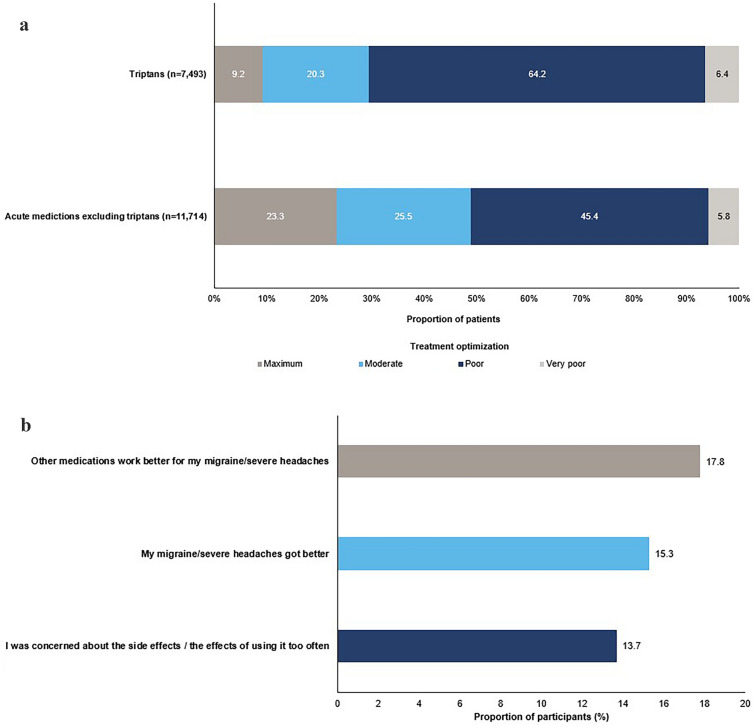

Responses to the mTOQ-6 indicated that total rates of poor and very poor treatment satisfaction were higher in people currently taking triptans compared with those using acute medications excluding triptans (Fig. 2a). Use of triptans and acute medications excluding triptans according to number of HDs/month and MIDAS grade is presented in Table 5. The proportions of patients using triptans and acute medications excluding triptans were both highest in patients with MIDAS Grade IV and ≥ 8 HDs/month. However, > 60% of patients with MIDAS Grade IV and either 8–14 (61.0%) or ≥ 15 (68.8%) HDs/month were using triptans, whereas the use of acute medications excluding triptans was 43.4% in those with 8–14 HDs/month and 60.9% in those with ≥ 15 HDs/month. Many participants (n = 5538) reported that they had stopped using triptans; the most common reason for stopping triptans being “other medications work better for my migraine/severe headaches” (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

a Migraine Treatment Optimization Questionnaire (mTOQ-6) responses in participants currently using triptans versus acute medications excluding triptans. b Most common reasons for discontinuing triptan use (total migraine cohort; n = 5538). Participants could be taking more than one acute medication, and could give more than one reason for no longer taking triptans

Table 5.

Current acute migraine/severe headache medication use according to MIDAS gradea (total migraine cohort)

| Total | HDs/month | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–3 | 4–7 | 8–14 | ≥ 15 | ||

| Participants currently using triptans | |||||

| n = 7493 | n = 4554 | n = 1780 | n = 749 | n = 410 | |

| MIDAS score, median (IQR) | 12.0 (6.0–25.0) | 10.0 (5.0–17.0) | 16.0 (9.0–30.0) | 27.0 (14.0–50.0) | 35.0 (16.0–78.0) |

| Numbers of participants in each MIDAS grade category, n (% of population using triptans) | |||||

| I—little or no disability | 1,670 (22.3) | 1,285 (28.2) | 279 (15.7) | 72 (9.6) | 34 (8.3) |

| II—mild disability | 1,564 (20.9) | 1,190 (26.1) | 275 (15.4) | 70 (9.3) | 29 (7.1) |

| III—moderate disability | 1,912 (25.5) | 1,190 (26.1) | 507 (28.5) | 150 (20.0) | 65 (15.9) |

| IV—severe disability | 2,347 (31.3) | 889 (19.5) | 719 (40.4) | 457 (61.0) | 282 (68.8) |

| Total | HDs/month | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–3 | 4–7 | 8–14 | ≥ 15 | ||

| Participants currently using acute medication excluding triptans | |||||

| n = 11,714 | n = 8015 | n = 2209 | n = 910 | n = 580 | |

| MIDAS score, median (IQR) | 6.0 (2.0–15.0) | 4.0 (1.0–10.0) | 10.0 (4.0–23.0) | 17.0 (8.0–38.0) | 33.0 (10.0–80.0) |

| Numbers of participants in each MIDAS grade category, n (% of population using acute medication excluding triptans) | |||||

| I—little or no disability | 5645 (48.2) | 4654 (58.1) | 692 (31.3) | 196 (21.5) | 103 (17.8) |

| II—mild disability | 2175 (18.6) | 1606 (20.0) | 417 (18.9) | 106 (11.6) | 46 (7.9) |

| III—moderate disability | 1875 (16.0) | 1100 (13.7) | 484 (21.9) | 213 (23.4) | 78 (13.4) |

| IV—severe disability | 2019 (17.2) | 655 (8.2) | 616 (27.9) | 395 (43.4) | 353 (60.9) |

aHigher MIDAS scores indicate greater disability: Grade I = score 0–5; Grade II = score 6–10; Grade III = score 11–20; Grade IV = score ≥ 21

HDs headache days, IQR interquartile range, MIDAS Migraine Disability Assessment

Analyses of Participants in the Moderate to Severe Attacks Subcohort

Participants and Acute Medication Usage

A total of 5547 of the 20,756 participants in the total migraine cohort (26.7%) experienced moderate to severe headache attacks [average pain severity ≥ 5 points (based on the MIDAS question on pain severity), pain duration ≥ 4 h, and at least moderate disability due to migraine (MIDAS score ≥ 11)] and were included in the moderate to severe attacks subcohort (Table 6).

Table 6.

Participant sociodemographic and characteristics and current acute medication usage (moderate to severe attacks subcohorta)

| Total (N = 5547) | HDs/month | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–3 (N = 2329) | 4–7 (N = 1697) | 8–14 (N = 884) | ≥ 15 (N = 637) | ||

| Mean (SD) age, years | 39.8 (12.8) | 38.5 (12.5) | 40.2 (12.6) | 40.5 (12.9) | 42.4 (13.4) |

| Female, n (%) | 3701 (66.7) | 1404 (60.3) | 1183 (69.7) | 631 (71.4) | 483 (75.8) |

| Current acute medication usage, n (%) | |||||

| Triptansb | 2687 (48.4) | 1149 (49.3) | 846 (49.9) | 429 (48.5) | 263 (41.3) |

| Ergot alkaloidsc,d | 618 (11.1) | 306 (13.1) | 166 (9.8) | 93 (10.5) | 53 (8.3) |

| NSAIDs | 4943 (89.1) | 2079 (89.3) | 1532 (90.3) | 792 (89.6) | 540 (84.8) |

| Paracetamol | 2940 (53.0) | 1229 (52.8) | 933 (55.0) | 470 (53.2) | 308 (48.4) |

| Combination analgesics | 1385 (25.0) | 548 (23.5) | 421 (24.8) | 232 (26.2) | 184 (28.9) |

| Combination of triptans/ergot alkaloids/NSAIDs/paracetamol | 4059 (73.2) | 1733 (74.4) | 1263 (74.4) | 640 (72.4) | 423 (66.4) |

aModerate to severe headache attacks were defined as being of average pain severity ≥ 5 points (based on the MIDAS question on pain severity), pain duration ≥ 4 h, and at least moderate disability due to migraine (MIDAS score ≥ 11)

HDs headache days, MIDAS Migraine Disability Assessment, NSAID nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, OTC over-the-counter, SD standard deviation

bTriptans are available on prescription or OTC in Germany but are prescription-only in Spain

cErgot alkaloids are only reimbursed in Germany

dData for ergot alkaloid use were missing for 1187 (21.4%) patients in the total moderate to severe attacks subcohort

Respondents in the moderate to severe attacks subcohort had a mean age of 39.8 years and 66.7% were female. Just under half of this subcohort (48.4%) were using triptans, and NSAIDs were the most commonly used acute treatment.

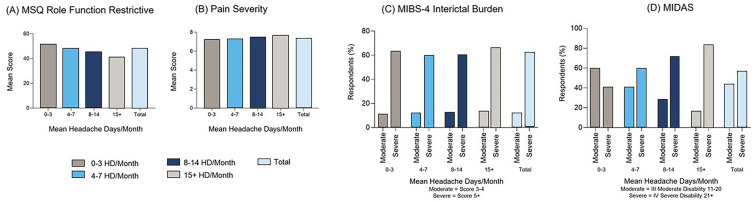

Migraine-Related Burden, QoL, Pain, and Disability

Participants in the moderate to severe attacks subcohort generally reported increased burden with increasing headache/migraine severity (Fig. 3). Patients with a higher number of HDs/month reported poorer QoL (MSQ), higher pain levels (MIDAS), and more severe migraine-related disability (MIDAS) than those with fewer HDs/month, although severe interictal burden (MIBS-4) was reported for ~ 60% of participants regardless of the number of HDs/month.

Fig. 3.

Migraine characteristics and burden in the moderate to severe attacks subcohorta. aModerate to severe headache attacks were defined as being of average pain severity ≥ 5 points (based on the MIDAS question on pain severity), pain duration ≥ 4 h, and at least moderate disability due to migraine (MIDAS score ≥ 11). Higher scores for MSQ indicate a better QoL; higher scores for MIBS-4 indicate greater burden; higher scores for MIDAS indicate greater disability. N numbers for MSQ and MIDAS pain severity survey question (A, B) = 0–3 HDs/month (n = 2224), 4–7 HDs/month (n = 1653), 8–14 HDs/month (n = 859), 15 + HDs/month (n = 601), total (N = 5337). N numbers for MIBS-4 and MIDAS (C, D) = 0–3 HDs/month (n = 2329), 4–7 HDs/month (n = 1697), 8–14 HDs/month (n = 884), 15 + HDs/month (n = 637), total (N = 5547). HDs headache days, MIBS-4 Migraine Interictal Burden Scale-4, MIDAS Migraine Disability Assessment, MSQ Migraine-Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire, QoL quality of life

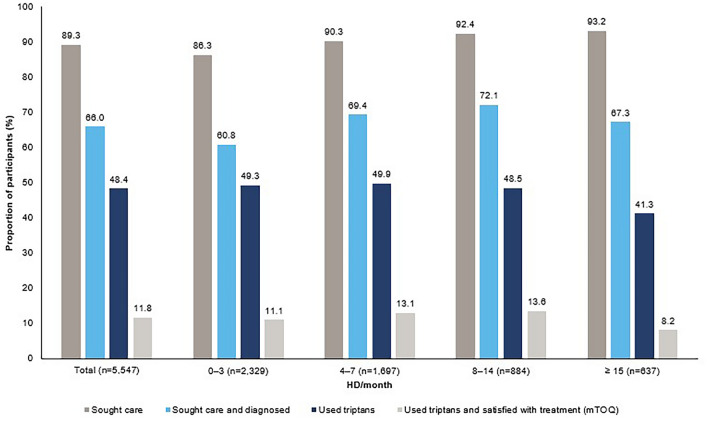

Triptan Use and Treatment Satisfaction in Participants Who Sought Care

Although > 80% of participants in the moderate to severe attacks subcohort sought medical care, less than half were diagnosed with migraine and/or used triptans (Fig. 4). Of those who did use triptans, treatment satisfaction was generally poor regardless of HDs/month.

Fig. 4.

Migraine characteristics and burden in the moderate to severe attacks subcohorta. aModerate to severe headache attacks were defined as being of average pain severity ≥ 5 points (based on the MIDAS question on pain severity), pain duration ≥ 4 h, and at least moderate disability due to migraine (MIDAS score ≥ 11). bTriptan treatment as per Spanish and German guidelines [17, 18]. Triptans are available on prescription or OTC in Germany but are prescription-only in Spain. HDs headache days, MIDAS Migraine Disability Assessment, mTOQ-6 six-item Migraine Treatment Optimization Questionnaire, OTC over-the-counter

Discussion

This study provides population data for real-world migraine burden and treatment patterns in Spain and Germany and illustrates the negative effects of migraine/severe headache on QoL, pain, disability, and healthcare resource use, despite the availability of current treatment options.

Pain of moderate or severe intensity was the most frequently reported migraine symptom (92.0% of participants in the total migraine cohort), and pain intensity and the proportion of participants reporting symptoms generally increased with the number of HDs/month. Participants with a higher number of HDs/month also reported poorer QoL (MSQ) and higher interictal burden (MIBS-4). Migraine/severe headache also accounted for just over half of visits to an HCP in the past 12 months; people with higher MIDAS grades were more likely to visit specialists or emergency care, whereas pharmacist or primary care/general practice visits were more likely for those with lower grades.

Our analysis of participants in the moderate to severe attacks subcohort [average pain severity ≥ 5 points (based on the MIDAS question on pain severity), pain duration ≥ 4 h, and at least moderate disability due to migraine (MIDAS score ≥ 11)] also found burden generally increased with increasing headache/migraine severity. Patients with a higher number of HDs/month reported poorer QoL, higher pain levels (MIDAS), and more severe migraine-related disability (MIDAS) than those with fewer HDs/month, although severe interictal burden was reported for ~ 60% of participants regardless of the number of HDs/month.

Despite the high levels of burden reported, the data also highlight a low use of triptans, even in people with moderate to severe headache attacks, and generally poor treatment satisfaction in those who use triptans. These findings are concerning, given that triptans are the recommended treatment for moderate to severe migraine attacks in both Spanish and German guidelines [17, 18], and illustrate an unmet need for new treatment options for patients with migraine or severe headache.

Most participants in the total migraine cohort reported that they were currently using acute migraine/severe headache medication, although less than half of these were using triptans; the most common categories of acute medication were OTC analgesics, NSAIDs on prescription, and paracetamol, with many people taking multiple acute medications. Very few people were using ergot alkaloids, although these are only reimbursed in Germany and are not reimbursed in Spain. Triptans are available on prescription or OTC in Germany but are prescription-only in Spain. Triptan use was more common in participants who were also using preventive medication, and NSAIDs on prescription, OTC analgesics, and suppositories were also commonly used in combination with preventive medication. It could be speculated that the use of preventive medication may be a sign of a more migraine-specific approach to treatment, or that patients using preventive medication had higher disability and were therefore more likely to use triptans than those using acute medication alone. However, our analysis of triptan use in people with moderate to severe headache attacks (defined as average pain severity ≥ 5 points, pain duration ≥ 4 h, and MIDAS score ≥ 11; n = 5547) also found that less than half (48.4%) of those with moderate to severe attacks were using triptans, despite both Spanish and German guidelines recommending their use in this population [17, 18]. This was observed even though > 80% of participants in this subcohort sought medical care, with NSAIDs being the most commonly used acute medication, reflecting an unmet need for people with migraine. Despite seeking care, symptoms may go unrecognized or be underestimated by HCPs, resulting in patients going undiagnosed and not receiving the recommended treatment. Although the proportions of participants using triptans in our study is higher than some other reports from European countries [19, 38], these other reports are based on the general migraine population and migraine severity is not reported in these studies. The Eurolight study also showed considerable variation in medication use according to the population sample, with higher usage reported for general practitioner-based samples and those from lay organizations compared with population-based samples [19]. Triptan use was estimated at < 6% for people with migraine in an Austrian study, but this was based on a general population sample and estimated migraine prevalence, and migraine severity was not reported [38].

A high proportion of participants using triptans reported poor treatment satisfaction, and many people reported that they had stopped using triptans. Treatment satisfaction (according to mTOQ-6) was generally poor regardless of migraine/headache severity, with poor satisfaction being reported by most triptan-using participants in both the total migraine cohort and the moderate to severe attacks subcohort. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that other factors related to migraine severity or the potential concomitant use of triptans and other migraine medications may have impacted the mTOQ-6 score, which is not medication specific. A global real-world study of people using triptans as their only acute migraine medication reported considerably higher rates of satisfaction than ours, even in those considered to be insufficient responders to triptans [59% of insufficient responders (i.e., freedom from headache pain within 2 h of treatment in ≤ 3/5 migraine attacks) reported being satisfied or extremely satisfied, compared with 92% of triptan responders (those with pain freedom within 2 h in ≥ 4/5 attacks)] [39]. However, that study did not use the mTOQ-6, and data for response based on headache freedom after using triptans were not collected in the OVERCOME (EU) study, so the results are not directly comparable.

In the current study, treatment satisfaction in the total migraine cohort was lower in participants currently taking triptans compared with those using acute medications excluding triptans. The most common reasons for discontinuing triptans [in the 5538 patients who had discontinued triptans (8686 patients reported ever having used triptans)] were that other medications were considered more effective, migraine/severe headaches improved, and concerns about side effects (although the incidence of actual adverse events was not reported) and frequent use. Other studies have reported that around 30–40% of people with migraine do not respond to triptans, although some people who do not respond to one triptan find they do respond to an alternative triptan [40, 41]. However, as data on the number of different triptans participants had used, or the sequence of treatments, were not collected in the OVERCOME (EU) study, we were unable to further evaluate any influence of this.

The lack of triptan use may partly be due to the high use of primary care and pharmacist services compared with specialist headache or pain services, even by people with higher MIDAS grades, which again may result from a lack of referrals due to under-recognition of symptoms. Migraine burden in the moderate to severe attacks subcohort generally increased with increasing headache/migraine severity, and interictal burden was high regardless of the number of HDs/month, indicating high levels of burden in patients using existing medications. The unmet treatment need for people with severe headache/migraine was previously highlighted in the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention study, which found no significant improvement in headache-related disability in people who switched from one triptan to another, an opioid, or a barbiturate, compared with those with consistent triptan use [42]. That study also found that switching from a triptan to an NSAID was associated with an increase in disability, especially among those with ≥ 10 HDs/month [42].

Strengths of the OVERCOME (EU) study include its provision of previously lacking real-world evidence from a population-based sample, allowing further insight into the unmet needs of people with migraine adding to previous data from other settings. The use of an internet-based survey also allowed for a large number of study participants, regardless of whether medical care was sought. These data are important as many people with migraine do not seek professional medical care so would not be represented in registry or observational studies.

However, surveys such as this are subject to limitations. As the survey data are self-reported, they are susceptible to recall, misinterpretation, and prioritization biases. It was also not possible to confirm if participant responses regarding migraine symptoms, severity, or duration were based on treated or untreated migraine attacks, and data regarding the sequence of treatments used were not collected. Although internet access is widely available in Germany and Spain, as with other online surveys the cohort is more likely to include people with greater technical abilities who were willing to be involved in computer surveys. In order to limit bias, the participants were invited and agreed to take part in the study without knowledge of which health topic was being researched. The health topic (migraine) was then disclosed at the screening stage. However, we acknowledge the potential for differences between survey respondents and the broader migraine population in attitudes and tolerance to pain and other symptoms to influence findings regarding treatment satisfaction.

Further analyses of data from the OVERCOME (EU) study will provide important information on essential topics required to improve care for people with migraine, for example the need for targeted care, and in the case of severely affected patients, specialized care.

Conclusions

These data provide important insights into the real-world experience of migraine treatment and burden. Less than half of participants in this study were using triptans, despite their recommendation in Spanish and German guidelines [17, 18], and treatment satisfaction in those who did use triptans was generally poor.

High levels of participant burden were experienced despite the use of a range of acute medications, including the use of multiple concurrent medications. It is important to understand the current status of migraine healthcare delivery and reasons why people with migraine do not seek professional help, even though medical advice and treatment is accessible in their country. This understanding, together with new tailored acute treatment options expected to enter the market, may help to address the current unmet needs of people with migraine.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participants of this study for their time and important contributions.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

Medical writing support was provided by Claire Lavin and Sue Williamson on behalf of Rx Communications, funded by Eli Lilly and Company.

Author Contributions

Stefan Evers was involved with the analysis and interpretation of data for the work, and in critical revision of the work. Grazia Dell’Agnello and Saygin Gonderten were involved with the design of the work, the interpretation of data for the work, and the drafting and the critical revision of the work. Diego Novick and Julio Pascual were involved with the interpretation of data for the work and the critical revision of the work. Tommaso Panni was involved with the design of the work and analysis of data for the work, the interpretation of data for the work, and in critical revision of the work. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, commented on previous versions of the manuscript, and have read and approved for the final manuscript for publication.

Funding

This study and Rapid service fee was funded by Eli Lilly and Company.

Data Availability

The data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the need for patient data protection.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Stefan Evers has received honoraria for lectures and consulting fees from Eli Lilly, Lundbeck, Novartis, Perfood, Rehaler, and Teva (in the last 3 years). Grazia Dell’Agnello, Diego Novick, Saygin Gonderten, and Tommaso Panni are employees and minor shareholders of Eli Lilly and Company. Julio Pascual has participated in Symposia and Advisory Boards of Allergan, Amgen-Novartis, Biohaven, Teva, and Lilly.

Ethical Approval

This study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments. Ethical review board approval for the study was granted by the Marqués de Valdecilla University Hospital (Spain) and participants were required to provide informed consent prior to commencing the study by selecting “I agree to participate” on the online form. All survey respondents provided informed consent and all data were anonymized before analysis.

References

- 1.Stovner LJ, Andree C. Prevalence of headache in Europe: a review for the Eurolight project. J Headache Pain. 2010;11(4):289–299. doi: 10.1007/s10194-010-0217-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matías-Guiu J, Porta-Etessam J, Mateos V, et al. One-year prevalence of migraine in Spain: a nationwide population-based survey. Cephalalgia. 2011;31(4):463–470. doi: 10.1177/0333102410382794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoon M-S, Katsarava Z, Obermann M, et al. Prevalence of primary headaches in Germany: results of the German Headache Consortium Study. J Headache Pain. 2012;13(3):215–223. doi: 10.1007/s10194-012-0425-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salazar A, Berrocal L, Failde I. Prevalence of migraine in general Spanish population; factors related and use of health resources. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(21):11145. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182111145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roessler T, Zschocke J, Roehrig A, Friedrichs M, Friedel H, Katsarava Z. Administrative prevalence and incidence, characteristics and prescription patterns of patients with migraine in Germany: a retrospective claims data analysis. J Headache Pain. 2020;21(1):85. doi: 10.1186/s10194-020-01154-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feigin VL, Nichols E, Alam T, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(5):459–480. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30499-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steiner TJ, Stovner LJ, Jensen R, Uluduz D, Katsarava Z, Lifting The Burden: the Global Campaign against Headache Migraine remains second among the world’s causes of disability, and first among young women: findings from GBD2019. J Headache Pain. 2020;21(1):137. doi: 10.1186/s10194-020-01208-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferracini GN, Dach F, Speciali JG. Quality of life and health-related disability in children with migraine. Headache. 2014;54(2):325–334. doi: 10.1111/head.12251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Insinga RP, Ng-Mak DS, Hanson ME. Costs associated with outpatient, emergency room and inpatient care for migraine in the USA. Cephalalgia. 2011;31(15):1570–1575. doi: 10.1177/0333102411425960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lipton RB, Buse DC, Saiers J, Serrano D, Reed ML. Healthcare resource utilization and direct costs associated with frequent nausea in episodic migraine: results from the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) Study. J Med Econ. 2013;16(4):490–499. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2013.770748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diener H-C, Holle D, Dresler T, Gaul C. Chronic headache due to overuse of analgesics and anti-migraine agents. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2018;115(22):365–370. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2018.0365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buse DC, Rupnow MFT, Lipton RB. Assessing and managing all aspects of migraine: migraine attacks, migraine-related functional impairment, common comorbidities, and quality of life. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84(5):422–435. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)60561-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Linde M, Gustavsson A, Stovner LJ, et al. The cost of headache disorders in Europe: the Eurolight project. Eur J Neurol. 2012;19(5):703–711. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2011.03612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parikh SK, Young WB. Migraine: stigma in society. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2019;23(1):8. doi: 10.1007/s11916-019-0743-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agosti R. Migraine burden of disease: from the patient’s experience to a socio-economic view. Headache. 2018;58:17–32. doi: 10.1111/head.13301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sokolovic E, Riederer F, Szucs T, Agosti R, Sándor PS. Self-reported headache among the employees of a Swiss university hospital: prevalence, disability, current treatment, and economic impact. J Headache Pain. 2013 doi: 10.1186/1129-2377-14-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lasaosa SS, Rosich PR, editors. Manual de práctica clínica en cefaleas: recomendaciones diagnóstico-terapéuticas de la Sociedad Española de Neurología en 2020. Madrid: Sociedad Española de Neurología. 2020. p. 1–476. http://cefaleas.sen.es/pdf/ManualCefaleas2020.pdf. Accessed 15 Nov 2023.

- 18.Diener H-C, Holle-Lee D, Nägel S, et al. Treatment of migraine attacks and prevention of migraine: guidelines by the German Migraine and Headache Society and the German Society of Neurology. Clin Transl Neurosci. 2019;3(1):1–40. doi: 10.1177/2514183X18823377. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katsavara Z, Mania M, Lampl C, Herberhold J, Steiner TJ. Poor medical care for people with migraine in Europe—evidence from the Eurolight study. J Headache Pain. 2018;19(1):10. doi: 10.1186/s10194-018-0839-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lipton RB, Nicholson RA, Reed ML, et al. Diagnosis, consultation, treatment, and impact of migraine in the US: results of the OVERCOME (US) study. Headache. 2022;62(2):122–140. doi: 10.1111/head.14259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsumori Y, Ueda K, Komori M, et al. Burden of migraine in Japan: results of the ObserVational Survey of the Epidemiology, tReatment, and Care Of MigrainE (OVERCOME [Japan]) Study. Neurol Ther. 2022;11(1):205–222. doi: 10.1007/s40120-021-00305-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hirata K, Ueda K, Komori M, et al. Comprehensive population-based survey of migraine in Japan: results of the ObserVational Survey of the Epidemiology, tReatment, and Care Of MigrainE (OVERCOME [Japan]) study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2021;37(11):1945–1955. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2021.1971179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pascual J, Panni T, Dell’Agnello G, Gonderten S, Novick D, Evers S. Preventive treatment patterns and treatment satisfaction in migraine: results from the OVERCOME (EU) study. J Headache Pain. 2023;24(1):88. doi: 10.1186/s10194-023-01623-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gupta S, Ryvlin P, Faught E, Tsong W, Kwan P. Understanding the burden of focal epilepsy as a function of seizure frequency in the United States, Europe, and Brazil. Epilepsia Open. 2017;2(2):199–213. doi: 10.1002/epi4.12050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018;38(1):1–211. 10.1177/0333102417738202. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Kolodner K, Liberman J, Sawyer J. Reliability of the Migraine Disability Assessment score in a population-based sample of headache sufferers. Cephalalgia. 1999;19(2):107–114. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1999.019002107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Kolodner KB, Sawyer J, Lee C, Liberman JN. Validity of the Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) score in comparison to a diary-based measure in a population sample of migraine sufferers. Pain. 2000;88(1):41–52. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00305-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Dowson AJ, Sawyer J. Development and testing of the Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) Questionnaire to assess headache-related disability. Neurology. 2001;56(6 Suppl 1):S20–S28. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.suppl_1.s20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lipton RB, Serrano D, Nicholson RA, Buse DC, Runken MC, Reed ML. Impact of NSAID and triptan use on developing chronic migraine: results from the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) Study. Headache. 2013;53(10):1548–1563. doi: 10.1111/head.12201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adams AM, Serrano D, Buse DC, et al. The impact of chronic migraine: the Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes (CaMEO) Study methods and baseline results. Cephalalgia. 2015;35(7):563–578. doi: 10.1177/0333102414552532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rodríguez-Almagro D, Achalandabaso A, Rus A, Obrero-Gaitán E, Zagalaz-Anula N, Lomas-Vega R. Validation of the Spanish version of the Migraine Disability Assessment Questionnaire (MIDAS) in university students with migraine. BMC Neurol. 2020;20(1):67. doi: 10.1186/s12883-020-01646-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benz T, Lehmann S, Gantenbein AR, et al. Translation, cross-cultural adaptation and reliability of the German version of the migraine disability assessment (MIDAS) questionnaire. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2018;16(1):42. doi: 10.1186/s12955-018-0871-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lipton RB, Fanning KM, Serrano D, Reed ML, Cady R, Buse DC. Ineffective acute treatment of episodic migraine is associated with new-onset chronic migraine. Neurology. 2015;84(7):688–695. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lipton RB, Kolodner K, Bigal ME, et al. Validity and reliability of the migraine-treatment optimization questionnaire. Cephalalgia. 2009;29(7):751–759. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2008.01786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jhingran P, Osterhaus JT, Miller DW, Lee JT, Kirchdoerfer L. Development and validation of the Migraine-Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire. Headache. 1998;38(4):295–302. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.1998.3804295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jhingran P, Davis SM, LaVange LM, Miller DW, Helms RW. MSQ: Migraine-Specific Quality-of-Life Questionnaire: further investigation of the factor structure. Pharmacoeconomics. 1998;13(6):707–717. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199813060-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buse D, Bigal MB, Rupnow M, Reed M, Serrano D, Lipton R. Development and validation of the Migraine Interictal Burden Scale (MIBS): a self-administered instrument for measuring the burden of migraine between attacks. Neurology. 2007;68:A89. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zebenholzer K, Gall W, Wöber C. Use and overuse of triptans in Austria—a survey based on nationwide healthcare claims data. J Headache Pain. 2018;19(1):34. doi: 10.1186/s10194-018-0864-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lombard L, Farrar M, Ye W, et al. A global real-world assessment of the impact on health-related quality of life and work productivity of migraine in patients with insufficient versus good response to triptan medication. J Headache Pain. 2020;21(1):41. doi: 10.1186/s10194-020-01110-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Viana M, Genazzani AA, Terrazzino S, Nappi G, Goadsby PJ. Triptan nonresponders: do they exist and who are they? Cephalalgia. 2013;33(11):891–896. doi: 10.1177/0333102413480756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leroux E, Buchanan A, Lombard L, et al. Evaluation of patients with insufficient efficacy and/or tolerability to triptans for the acute treatment of migraine: a systematic literature review. Adv Ther. 2020;37(12):4765–4796. doi: 10.1007/s12325-020-01494-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Buse DC, Serrano D, Kori S, et al. Consistency vs. switching triptan treatment and headache-related disability: results of the American migraine prevalence & prevention study. J Headache Pain. 2013;14(Suppl 1):P212. doi: 10.1186/1129-2377-1-S14-P212. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the need for patient data protection.