Abstract

Background

Health behaviors play a significant role in chronic disease management. Rather than being independent of one another, health behaviors often co-occur, suggesting that targeting more than one health behavior in an intervention has the potential to be more effective in promoting better health outcomes.

Purpose

We aimed to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials of interventions that target more than one behavior to examine the effectiveness of multiple health behavior change interventions in patients with chronic conditions.

Methods

Five electronic databases (Web of Science, PubMed, CINAHL, EMBASE, and Cochrane) were systematically searched in November 2023, and studies included in previous reviews were also consulted. We included randomized trials of interventions aiming to change more than one health behavior in individuals with chronic conditions. Two independent reviewers screened and extracted data, and used Cochrane’s Risk of Bias 2 tool. Meta-analyses were conducted to estimate the effects of interventions on change in health behaviors. Results were presented as Cohen’s d for continuous data, and risk ratio for dichotomous data.

Results

Sixty-one studies were included spanning a range of chronic diseases: cardiovascular (k = 25), type 2 diabetes (k = 15), hypertension (k = 10), cancer (k = 7), one or more chronic conditions (k = 3), and multiple conditions (k = 1). Most interventions aimed to change more than one behavior simultaneously (rather than in sequence) and most targeted three particular behaviors at once: “physical activity, diet and smoking” (k = 20). Meta-analysis of 43 eligible studies showed for continuous data (k = 29) a small to substantial positive effect on behavior change for all health behaviors (d = 0.081–2.003) except for smoking (d = −0.019). For dichotomous data (k = 23) all analyses showed positive effects of targeting more than one behavior on all behaviors (RR = 1.026–2.247).

Conclusions

Targeting more than one behavior at a time is effective in chronic disease management and more research should be directed into developing the science of multiple behavior change.

Keywords: Noncommunicable diseases, Health behavior, Behavior change, Systematic review, Meta-analysis

Interventions aiming to change two or more behaviors in individuals with chronic conditions showed beneficial effects on diet, physical activity, medication adherence and alcohol consumption, but not smoking cessation

Introduction

Noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) account for 74% of all deaths [1]. Among NCDs, cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of mortality, followed by cancers, chronic respiratory diseases, and diabetes. With aging populations and an increase in the prevalence of long-term conditions, the number of people with multiple health conditions will continue to rise, resulting in multimorbidity [1]. Managing chronic health conditions is a complex and persistent challenge for people faced with them and the healthcare providers and systems serving them [2]. Health behaviors, such as physical activity, eating a healthy diet, and refraining from alcohol consumption and smoking, are not only key in preventing their development but also play a central part in their successful management [1, 3].

Behavior change interventions can play a role in preventing exacerbations of chronic conditions and minimizing their symptoms, by supporting individuals to reduce their behavioral risk factors (e.g., stop smoking), increase protective behaviors (e.g., increase physical activity), and/or follow behavioral advice (e.g., medication adherence [4]). Despite the multiple behaviors indicated for the management of chronic conditions, to date, most rigorously evaluated behavior change interventions have focused on promoting single behavior change [5–8] and related impact on clinical outcomes [6, 9]. Analyzing whether multiple health behavior change (MHBC) interventions lead to behavioral change is an important first step to understand which behaviors are driving the improvements in clinical outcomes. Also, as multiple health behaviors often co-occur or cluster together [10–12], engaging in multiple behaviors has the potential to support chronic disease management.

MHBC interventions aim to change more than one behavior, either sequentially or simultaneously [13]. Previous reviews of randomized trials assessing the effectiveness of MHBC interventions have reported small to moderate effects for diet-related outcomes and physical activity [14, 15], and null to small effects for smoking cessation [14, 16] across different populations. However, existing reviews have focused on (i) either the general population or specific populations (e.g., general population [14], primary prevention [11, 16], or specific chronic conditions [17, 18]), (ii) specific behavioral clusters (e.g., diet and physical activity [15, 17, 18], smoking cessation combined with two or more additional risk behaviors [19]), or (iii) specific modes of delivery (e.g., eHealth interventions only [15]). Also, most reviews have focused their meta-analyses on clinical rather than behavioral outcomes (e.g., [16, 17]), or have not conducted meta-analyses to assess the effectiveness of the interventions (e.g., [5, 11, 18, 19]).

Currently, to the best of our knowledge, there is no systematic review that comprehensively assesses the effectiveness of MHBC interventions in individuals with chronic health conditions with a focus on behavior change as the outcome of interest, without selecting based on chronic conditions and/or behavioral clusters targeted. Therefore, the main aim of this review with meta-analysis was to assess the effectiveness of interventions targeting more than one health behavior in the context of chronic disease management (including physical activity, diet, smoking cessation, alcohol consumption, and medication adherence).

Methods

The present review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA, see Supplementary Material 1 for PRISMA checklist) and has been pre-registered in PROSPERO (CRD42022327085) and Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/hr7u3).

Data Sources and Search Strategy

We searched Web of Science, PubMed, CINAHL, EMBASE, and Cochrane in November 2023 with no time constraints, to identify MHBC interventions targeting health-related behaviors of patients with chronic conditions.

Three sets of search terms were used, representing: (i) Population (“*patient*” OR “chronic condition” OR “chronic disease” OR “multiple morbidity” OR “comorbidity” OR “multimorbidity”); Intervention type (“MHBC” OR “multiple risk behav*” OR “multiple risk factors” OR “multiple health behav*” OR “multiple behav*” OR “goal-directed behav*”); and (iii) Study design (“randomized controlled trial” OR “RCT” OR “controlled trial” OR “controlled clinical trial” OR “random allocation” OR “random*” OR “intervention”). These terms were searched in the Title, Keyword, and Abstract sections (see https://osf.io/8hx5j/, for complete searches in each database).

Previous reviews of MHBC interventions in patients with chronic conditions were hand-searched, and their included studies were checked and assessed for inclusion.

Eligibility Criteria

For inclusion in this review, studies had to report MHBC interventions targeting individuals with chronic conditions, had to be published in peer-reviewed journals, and were written in English. Conference proceedings, protocols, and studies without available full texts were excluded. The following PICOS inclusion criteria were considered:

Population: Adults with at least one chronic condition, namely type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular conditions, cancer (including cancer survivors, cancer-free ≤5 years), and hypertension. Search terms used did not specify the type of chronic conditions, as these were selected after conducting the searches by analyzing if each condition that came up met our criteria to be considered a chronic condition (i.e., a disease with a long duration, that requires ongoing medical care and results in some form of functional impairment [20, 21]). For this review, we considered obesity as a risk factor for chronic disease.

Intervention: Aimed to change more than one health-related behavior (i.e., MHBC interventions). For the purpose of this review, we considered that for an intervention to be considered an MHBC intervention, it had to target two or more behavioral domains (e.g., diet and physical activity), as opposed to multiple aspects of one behavioral domain (e.g., fruit and vegetable consumption and energy intake).

Comparison: Any type of comparison group (e.g., usual care, minimal intervention). In order to evaluate interventions that were rigorously tested through randomized controlled trials (i.e., where both groups receive the same intervention except for the aspects being tested [22]), to be included in the meta-analysis we only considered studies with control groups receiving no intervention, receiving usual care only or minimal interventions.

Outcomes: Assessed at least one aspect of two or more health-related behavioral domains (e.g., fruit and vegetable consumption and physical activity minutes/week). This criterion was implemented due to the existence of various studies delivering “lifestyle interventions” that only provided data for one behavioral domain.

Study Design: Evaluated interventions within a randomized trial in a healthcare context (e.g., randomized controlled trials, cluster-randomized controlled trials, factorial designs), including digital modalities. To be included in the overall review, studies were included if they used randomization for group assignment, even if comparison groups were delivered different interventions. This allowed us to obtain a comprehensive overview of the types of MHBC interventions being conducted. However, for the meta-analysis, only randomized controlled trials were considered.

Study Selection

All identified articles were uploaded into RAYYAN [23], and duplicated records were removed. Two authors (CCS and MM) independently assessed the titles and abstracts of 20% of all studies. Similarly, included records at this stage were then screened based on full-text assessment. At both stages, discrepancies were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer (MMM). Inter-rater reliability was calculated at both screening stages using Cohen’s kappa, with values above 0.60 being considered moderate agreement, above 0.80 strong, and above 0.90 almost perfect [24].

Key reasons for exclusion were recorded at the full-text stage, these included: (i) not being a randomized trial, (ii) not being a behavioral intervention, (iii) behavioral intervention not targeting multiple behaviors, (iv) participants not having a physical chronic condition, (v) participants not being adults, (vi) not having more than one behavioral outcome of interest, (vii) study not being published in English, and (viii) not being able to obtain full-text.

Data Extraction

A standardized data extraction form was created in Microsoft Excel, and its development was informed by consulting existing ontologies and taxonomies to identify relevant information to be extracted, and by adding aspects of relevance to the context of multiple behavior changes (full data extraction table available at OSF: https://osf.io/hnvfu). However, this paper focuses exclusively on presenting data pertaining to study and sample details, intervention characteristics, and statistical outcomes, as follows:

- Study details: Authors, year of publication, study design, country, and dates of data collection.

- Sample details: Type of sample (i.e., condition, e.g., type 2 diabetes), mean age of participants, percentage of females, race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status.

- Intervention characteristics: Type of MHBC intervention (coded as sequential, simultaneous, or unclear), type of trial (coded as behavior change intervention only, part of a larger trial or unclear), intervention and control groups’ designations, duration, and behaviors targeted by the intervention.

- Statistical information: The following information was extracted regarding each behavioral outcome provided by authors: protocol available (coded as yes or no), primary/secondary outcome (coded as primary, secondary, or unclear), type of measurement (coded as objective or subjective), type of data (coded as dichotomous or continuous), intended direction of effect (coded as increase or decrease), the interval between the beginning of the intervention and last follow-up (coded as months), the interval between the end of the intervention and last follow-up (coded as months), the sample size of the intervention group and control group, type of statistics used to calculate the effect size, effect size provided by authors (when available), effect size calculated.

Data extraction was performed in full by one author (CCS), a second author independently extracted data for 20% of included studies (PS), and disparities were resolved through discussion.

Quality Assessment

Two authors independently assessed the methodological quality and risk of bias using the Cochrane Risk of Bias (RoB) 2 for randomized controlled trials and for cluster-randomized trials were used [25]. Disagreements were discussed with a third author. Inter-rater reliability was calculated using Cohen’s kappa.

For randomized controlled trials, the RoB tool has five domains: (i) bias arising from the randomization process, (ii) bias due to deviations from intended interventions, (iii) bias due to missing outcome data, (iv) bias in the measurement of the outcome, and (v) bias in the selection of the reported result. Whereas for cluster-randomized trials the RoB tool has an additional domain accounting for “identification/recruitment bias.” Each domain is comprised by signaling questions and the responses to these questions are fed into algorithms to score each domain either as “low risk,” “some concerns,” or “high risk.” The scores of each domain are further mapped into an overall risk of bias judgment.

Data Synthesis

A narrative and descriptive synthesis of the key aspects of included studies was provided for information on study and sample details, and intervention characteristics (in summary tables organized per condition).

For the meta-analyses, we only included studies that used what we established as a “true” control group (i.e., no intervention, usual care, delayed intervention, or minimal intervention), and that provided sufficient/adequate data to calculate effect sizes.

In this review, we included studies that focused on two or more behavioral domains, such as physical activity and diet. However, due to the considerable heterogeneity in the measurement of these domains, we established general and specific rules for the inclusion of outcomes: First, we categorized outcome data as continuous or dichotomous. Within each category, outcomes were further divided based on how they were measured, that is, objectively (e.g., pedometers) or subjectively (e.g., self-reported questionnaires). This resulted in four categories: “subjective and continuous,” “subjective and dichotomous,” “objective and continuous,” and “objective and dichotomous.” If the authors provided data for multiple categories (e.g., medication adherence measured both subjectively and objectively), we included them all in the separate analyses. However, if authors provided multiple measures within one category for a behavioral domain (e.g., “moderate aerobic exercise, minutes/week” and “mild aerobic exercise, minutes/week” measured subjectively and provided as continuous data), we selected the most frequently reported measure from the ones provided and used that one for the analysis.

We also established rules within each behavioral domain. For the diet domain, a substantial variety of aspects were identified. We selected the most frequently reported outcomes across studies to ensure we were able to capture at least one aspect of diet from most studies, which were “fruit and vegetable intake” (combined or separately) and “fat intake” (including outcomes such as total fat, saturated fat, unsaturated fat, high-fat foods).

For the physical activity domain, data was first separated based on whether they measured physical activity or sedentary behavior. Since multiple variables were frequently provided for this domain (e.g., “strenuous or moderate aerobic exercise, minutes/week,” “strenuous aerobic exercise, minutes/week,” “moderate aerobic exercise, minutes/week,” and “mild aerobic exercise, minutes/week”), we selected one outcome for each analyses based on its frequency (i.e., when multiple measurements were provided for the same behavioral domain, we chose the most frequently reported one from the included studies).

The same decision rules were applied for the remaining behavioral domains, that is, smoking cessation, alcohol consumption, and medication adherence. This systematic approach ensured greater comparability across studies.

After applying the decision rules, relationships between the behavioral variables were analyzed using meta-analytical techniques (effects) using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA [26]). Pooled intervention effect estimates were presented using a random-effects model using a 95% confidence interval. Meta-analyses were conducted to compare differences between outcomes of intervention and control participants for each of the following behaviors: physical activity, sedentary behavior, fruit and vegetable intake, fat intake, smoking cessation, alcohol consumption, and medication adherence. Analyses were separated according to the follow-up timepoint (at the end of the intervention and at the latest follow-up time provided), type of measurement (subjective and objective), and type of data provided (continuous and dichotomous). Possible estimated effect sizes were calculated using Cohen’s d for continuous outcomes and Risk Ratios (calculated assuming a higher value, i.e., >1, is a positive change) for dichotomous outcomes. The presence and extent of heterogeneity were explored using the I2 statistics.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted when possible if (i) studies obtained a high overall risk of bias according to the RoB 2 tool, (ii) the interventions lacked clarity regarding the behaviors being targeted (e.g., using terms such as “lifestyle”), and (iii) extremely long follow-ups were used (e.g., 60 months).

Subgroup analyses were planned for the type of chronic condition of participants (i.e., cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, cancer, and one or more chronic conditions). However, due to the limited number of studies available for each analysis, effects were provided for each of these conditions and behaviors for reference.

Results

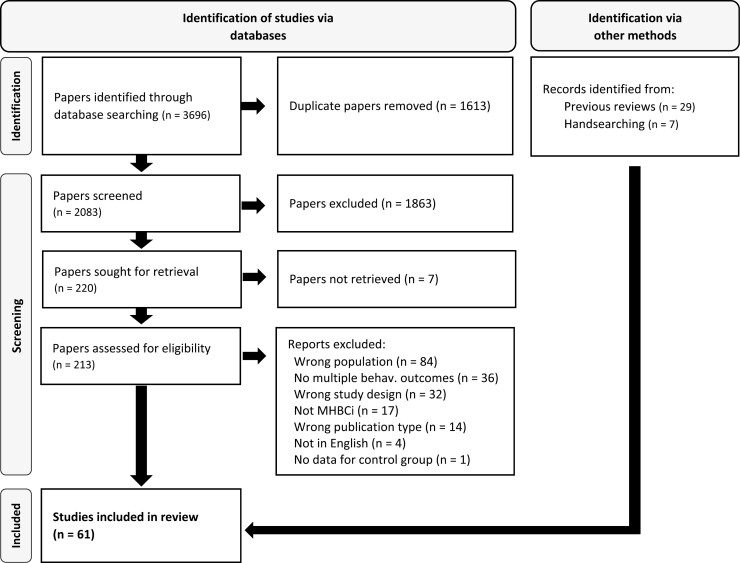

Electronic searches identified 3,696 records, 2,083 after removing duplicates. Of these, 213 were screened at the full-text level, and a total of 25 studies were included. Moderate inter-rater reliability was obtained for screening at the full-text stage (k = 0.709). In addition, 36 studies were identified by going through the included studies of previous reviews [15–19]. In total, 61 studies were included in the review (see Fig. 1 for the Flow chart and Supplementary Material 2 for a list of included studies).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow chart.

See Supplementary Table 1 for a complete list of reasons for excluded studies at the full-text screening stage.

Overview of Studies

Of the 61 included studies, 25 related to cardiovascular diseases (40.98%), 15 to type 2 diabetes (24.59%), 10 to hypertension (16.39%), 7 to cancer (11.48%), 3 to one or more chronic conditions (4.92%; which included one study with individuals with type 2 diabetes and/or hypertension, one with individuals with diabetes and/or coronary heart disease, and one with older adults with one or more chronic conditions), and 1 with individuals with self-reported arthritis and other health conditions (1.64%). The included studies were published between 1994 and 2023 and across 24 countries, the most frequent ones being USA (k = 21, 34.43%), UK (k = 8, 13.11%), and Australia (k = 5, 8.20%).

Overall, the average age of participants was 58.53 years, with a slightly lower average age observed in studies targeting individuals with hypertension (M = 56.80). The percentage of females in all studies was 48.45%. However, across all conditions, the average proportion of female participants was higher (ranging from 57.61% to 81.80%), except in studies targeting cardiovascular diseases (28.53%). See Supplementary Table 2 for study, sample, and setting information.

Intervention Characteristics

The number of behaviors targeted per intervention ranged between 2 and 5, with an average of 3. Physical activity and diet were the most frequent behaviors targeted (k = 60 and k = 56 respectively), followed by smoking cessation (k = 38), alcohol consumption (k = 14), and medication adherence (k = 13). Overall, a total of 10 behavioral clusters were targeted across interventions, with the most frequent ones being: “physical activity, diet and smoking” (k = 20, 32.79%), and “physical activity and diet” (k = 16, 26.32%). The most frequently targeted behavioral clusters for each condition were as follows: “diet, physical activity and smoking” for cardiovascular diseases (k = 12 of 25), “diet and physical activity” for type 2 diabetes (k = 7 of 15), and cancer (k = 5 out of 7), and “diet, physical activity, smoking and alcohol consumption” for hypertension (k = 3 out of 10). Most interventions were considered “behavior change interventions only” (k = 53), with the remaining being “part of a larger trial” (k = 7) or “unclear” (k = 1).

Some intervention groups aimed to change multiple behaviors simultaneously (k = 46), others sequentially (k = 8), and the remaining ones did not provide sufficient information to make this determination (k = 10). Those aiming to change behaviors sequentially were mostly found in the context of cardiovascular diseases (k = 3), and targeting two behaviors (k = 4), with the most frequent cluster being “physical activity and diet” (k = 3).

Most studies had one intervention group and one comparison group. Three studies had two intervention groups: (i) Glasgow et al. [27] had two intervention groups (“computer-assisted diabetes self-management (CASM)” and “CASM plus human support condition”) and a control (“enhanced usual care”), (ii) Hyman et al. [28] had two intervention groups (“simultaneous group” and “sequential group”) and a control (“usual care”), and (iii) Liu et al. [29] had two intervention groups (“expert-driven e-counselling” and “control driven e-counselling”) and a control. One study had one intervention group that matched our criteria (“multiple-goal group”) and two possible comparison groups (“single-goal group” and “attention control group” [30]).

Regarding the types of control groups used, most studies used usual care/routine care as controls (k = 29), others had no intervention, minimal interventions, or waiting groups (k = 23), and the remaining used different interventions as controls (k = 10).

A wide range of intervention duration was found, varying from one day only to 7.8 years. Most interventions lasted up to 6 months (54.10%), but on average intervention duration was close to 1 year (48.10 weeks). See Supplementary Table 3 for intervention characteristics. See Table 1 for a summary of the sample and study details of included interventions.

Table 1.

Summary of Sample and Study Details of Included Interventions

| Mean age of sample | % Females (%) | Type of MHBCi | Type of trial | Average overall duration | Average no. of behaviors targeted | Most frequently targeted behavioral cluster | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular diseases (k = 25) |

59.4a | 28.5a | 19 Simultaneous 3 Sequential 3 Unclear |

23 BCI 2 Part of larger trial |

39.4 weeks | 3.2 | Diet, PA and smoking (k = 12) |

| Type 2 diabetes (k = 15) |

57 | 60.6a | 13 Simultaneous 3 Unclear |

12 BCI 3 Part of larger trial |

73.6 weeks | 2.6 | Diet and PA (k = 7) |

| Hypertension (k = 10) |

56.8a | 57.6a | 8 Simultaneous 1 Sequential 1 Both 1 Unclear |

7 BCI 2 Part of larger trial 1 Unclear |

58.2 weeks | 3.4 | Diet, PA, smoking and alcohol (k = 3) |

| Cancer and cancer survivors (k = 7) |

57.8 | 69.5 | 4 Simultaneous 2 Sequential 1 Unclear |

7 BCI | 20 weeks | 2.4 | Diet and PA (k = 5) |

| One or more chronic conditions (k = 3) |

62.0 | 65.7 | 2 Unclear 1 Simultaneous |

3 BCI | 37.3 weeks | 2.7 | Diet and PA (k = 1) Diet, PA and smoking (k = 1) Diet, PA and medication adherence (k = 1) |

| Multiple conditions (k = 1) |

72.8 | 87.9 | 1 Sequential | 1 BCI | 10 weeks | 2 | PA and smoking (k = 1) |

BCI behavior change intervention only; MHBCi multiple health behavior change interventions; PA physical activity.

aData not available for all studies.

Quality Appraisal

The risk of bias assessment for RCTs is detailed in Supplementary Fig. 1, which referred to 53 studies (151 outcomes). Most studies presented some concerns regarding the overall risk of bias (49.7%), including some that were high risk (30.5%) and low risk (19.9%). The domain with the smallest percentage of studies with a low risk was “selection of the reported result” (36.4%), and this was mostly due to some studies not having a clear description of their outcomes, a pre-registered protocol, or having inconsistencies.

The risk of bias assessment for cluster RCTs is detailed in Supplementary Fig. 2, which referred to eight studies (19 outcomes). A low overall risk of bias was not identified for any study because all presented some level of concern on one (or more) domains. Most studies presented some concerns regarding the overall risk of bias (73.3%) and the remaining presented high risk (26.3%).

Inter-rater reliability was assessed for 20% of the studies, and a moderate agreement was obtained (k = 0.68).

Meta-analyses

Of the 61 studies, 43 were included in the meta-analyses. Those that were excluded were due to not using a “true” control group (k = 8) and due to not having sufficient/adequate data available to calculate effects (k = 10). See Supplementary Table 4 for reasons for exclusion from meta-analysis.

The behavioral outcomes included in this review were separated for analyses according to the following categories: (i) physical activity, (ii) sedentary behavior, (iii) fruit and vegetable intake, (iv) fat intake, (v) smoking cessation, (vi) alcohol consumption, and (vii) medication adherence. To ensure comparability across studies, analyses were also separated based on the type of measurement used (subjective or objective), the type of statistical data provided (continuous or dichotomous), and according to the timepoints provided (at the end of the intervention and at the latest follow-up available).

Overall Effectiveness of MHBC Interventions Across Health-related Behaviors

Sixteen analyses were conducted for studies that provided outcome data at the end of the intervention. All analyses showed small to large positive effects for the behaviors of interest (d = 0.081–2.003, RR = 1.026–2.001), except for smoking cessation for subjective and continuous data, which had a small negative effect (d = −0.019). See Table 2 for a summary of the effects.

Table 2.

Summary of Effects at the End of Intervention Timepoint

| Physical activity | Sedentary behavior | Fruit and veg intake | Fat intake | Smoking cessation | Alcohol consumption | Medication adherence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjective and continuous |

d = 0.177 CI = 0.091–0.263 I2 = 50.95% k = 20 nIG = 2,566 nCG = 2,535 8 targeted D, PA, and S 6 targeted D and PA 2 targeted D, PA, S, and A 2 targeted D, PA, S, A, and MA 1 targeted PA, S, and A 1 targeted D, PA, and MA |

d = 2.003 CI = N/A I2 = N/A k = 1 nIG = 93 nCG = 93 Targeted D, PA, and S |

d = 0.232 CI = 0.013–0.452 I2 = 86.04% k = 8 nIG = 1,279 nCG = 1,342 2 targeted D, PA, and S 4 targeted D and PA 1 targeted D, PA, S, and A 1 targeted D, PA, S, A, and MA |

d = 0.436 CI = 0.199–0.674 I2 = 85.47% k = 10 nIG = 1,181 nCG = 1,128 3 targeted D, PA, and S 6 targeted D and PA 1 targeted D, PA, S, and A |

d = −0.019 CI = −0.211 to 0.172 I2 = 19.41% k = 4 nIG = 288 nCG = 275 1 targeted D, PA, and S 1 targeted D, PA, S, and A 1 targeted D, PA, S, A, and MA 1 PA, S, and A |

d = 0.081 CI = −0.045 to 0.206 I2 = 15.35% k = 6 nIG = 650 nCG = 641 1 targeted D and PA 3 targeted D, PA, S, and A 1 targeted D, PA, S, A, and MA 1 PA, S, and A |

d = 0.373 CI = 0.185–0.560 I2 = 3.67% k = 4 nIG = 236 nCG = 229 1 targeted D, PA, S & A 1 targeted D, PA, S, and MA 1 targeted D, PA, S, A, and MA 1 PA, S, and A |

| Subjective and dichotomous | RR = 1.661 CI = 1.395–1.977 I2 = 85.66% k = 12 nIG = 2,209 nCG = 2,188 3 targeted D, PA, S, A, and MA 2 targeted D, PA, and S 2 targeted D and PA 2 targeted D, PA, S, and A 2 targeted D, PA, and MA 1 targeted D, PA, and A |

RR = 2.001 CI = N/A I2 = N/A k = 1 nIG = 338 nCG = 351 Targeted D, PA, and S |

RR = 1.326 CI = 1.043–1.686 I2 = 87.93% k = 7 nIG = 2,292 nCG = 1,042 2 targeted D, PA, and S 2 targeted D and PA 1 targeted D, PA, S, and A 2 targeted D, PA, S, A, and MA |

RR = 1.286 CI = 0.896–1.845 I2 = 64.56% k = 3 nIG = 371 nCG = 349 1 targeted D, PA & S 1 targeted D and PA 1 targeted D, PA, and A |

RR = 1.102 CI = 1.020–1.189 I2 = 77.63% k = 12 nIG = 1,712 nCG = 1,781 3 targeted D, PA, and S 1 targeted D, PA, and A 4 targeted D, PA, S, and A 1 targeted S and A Targeted D, PA, S 1 targeted D, PA, S, and MA 2 targeted D, PA, S, A, and MA |

RR = 1.026 CI = 0.936–1.125 I2 = 55.11% k = 5 nIG = 609 nCG = 491 2 targeted D, PA, S, and A 1 targeted D, PA, S, A, and MA 1 PA, S, and A 1 S and A |

RR = 1.047 CI = N/A I2 = N/A k = 2 nIG = 595 nCG = 595 1 targeted D, PA, and MA 1 targeted D, PA, S, A, and MA |

| Objective and continuous |

d = 0.358 CI = −0.074 to 0.790 I2 = 87.22% k = 3 nIG = 339 nCG = 337 1 targeted D, PA, and S 1 targeted D and PA |

N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Objective and dichotomous | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | RR = 1.252 CI = 1.019–1.538 I2 = 65.35% k = 4 nIG = 675 nCG = 699 4 targeted D, PA, and S |

N/A | N/A |

A alcohol consumption; CG control group; D diet; IG intervention group; MA medication adherence; PA physical activity; S smoking cessation.

For studies that provided outcome data at the latest follow-up time available, all analyses showed small to large positive effects for the behaviors of interest (d = 0.139–0.894, RR = 1.006–2.247). See Table 3 for a summary of effects.

Table 3.

Summary of Effects at the Latest Follow-up Timepoint Available

| Physical a ctivity | Sedentary behavior | Fruit and veg Intake | Fat intake | Smoking cessation | Alcohol consumption | Medication adherence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjective and continuous |

d = 0.231 CI = −0.055 to 0.516 I2 = 84.90% k = 7 nIG = 768 nCG = 743 3 targeted D and PA 1 targeted D, PA, and S 1 targeted D, PA, S, and A 1 targeted D, PA, S, A & MA 1 targeted D, PA, and MA |

N/A |

d = 0.139 CI = 0.015–0.263 I2 = 0% k = 3 nIG = 489 nCG = 512 2 targeted D and PA 1 targeted D, PA, S, and A |

d = 0.517 CI = 0.030–1.003 I2 = 93.08% k = 5 nIG = 604 nCG = 574 3 targeted D and PA 2 targeted D, PA, S, and A |

d = 0.228 CI = N/A I2 = N/A k = 1 nIG = 40 nCG = 40 targeted D, PA, S, A, and MA |

d = 0.320 CI = N/A I2 = N/A k = 2 nIG = 199 nCG = 203 1 targeted D, PA, S, and A 1 targeted D, PA, S, A, and MA |

d = 0.475 CI = N/A I2 = N/A k = 2 nIG = 123 nCG = 124 1 targeted D, PA, S, A, and MA 1 targeted D, PA, S, and MA |

| Subjective and dichotomous | RR = 1.860 CI = 1.227–2.819 I2 = 90.03% k = 4 nIG = 1,404 nCG = 672 3 targeted D, PA, and S 1 targeted D and PA |

RR = 2.247 CI = N/A I2 = N/A k = 1 nIG = 67 nCG = 69 Targeted D, PA, and S |

RR = 2.045 CI = N/A I2 = N/A k = 1 nIG = 944 nCG = 991 Targeted D, PA, and S |

RR = 1.367 CI = N/A I2 = N/A k = 1 nIG = 356 nCG = 417 Targeted D, PA, and S |

RR = 1.006 CI = 0.893–1.134 I2 = 51.14% k = 5 nIG = 2,043 nCG = 1,785 2 targeted D, PA, and S 1 targeted D, PA, S, and MA 1 D and PA 1 D, PA, S, and A |

RR = 1.194 CI = N/A I2 = N/A k = 1 nIG = 156 nCG = 173 1 targeted D and PA |

N/A |

| Objective and continuous |

d = 0.894 CI = 0.657–1.130 I2 = N/A k = 1 nIG = 151 nCG = 151 targeted D and PA |

N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Objective and dichotomous | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | RR = 1.226 CI = N/A I2 = N/A k = 2 nIG = 302 nCG = 396 2 targeted D, PA, and S |

N/A | N/A |

A alcohol consumption; CG control group; D diet; IG intervention group; MA medication adherence; PA physical activity; S smoking cessation.

Change in Physical Activity Levels

End of intervention timepoint: In trials reporting outcomes at the end of the intervention period, 20 studies with subjective and continuous data were analyzed to assess changes in physical activity. These showed small positive effects in changing physical activity (d = 0.177, CI = 0.091–0.263, I2 = 50.95%, k = 20). See Supplementary Fig. 3 for plot. For interventions providing subjective and dichotomous outcomes, the likelihood of an increase in physical activity levels was higher in the treatment group than in the control (RR = 1.661, CI = 1.395–1.977, I2 = 85.66%, k = 12). See Supplementary Fig. 4 for plot. As for interventions targeting physical activity that provided objective and continuous outcomes, these had moderate positive effects in changing physical activity (d = 0.358, CI = −0.074 to 0.790, I2 = 87.22%, k = 3). From the three interventions in the analysis, two were part of the same study that had two intervention groups and one control. See Supplementary Fig. 5 for plot.

Latest follow-up timepoint: Analysis of the six studies with subjective and continuous data showed positive effects in increasing physical activity (d = 0.231, CI = −0.055 to 0.516, I2 = 84.90%, k = 7). See Supplementary Fig. 6 for plot. For interventions providing subjective and dichotomous data, increases in physical activity levels were more likely in the treatment group than the control group (RR = 1.860, CI = 1.227–2.819, I2 = 90.03%, k = 4). See Supplementary Fig. 7 for plot. Only one intervention provided objective and continuous data for a physical activity outcome with a follow-up period after the end of the intervention, and it had a large positive effect (d = 0.894, CI = 0.657–1.130, k = 1).

Publication bias and sensitivity analyses: For physical activity, funnel plots indicated some asymmetry for subjective and continuous/dichotomous data at both timepoints (end of the intervention and latest follow-up). For these, the use of the trim and fill methods estimated one missing study for subjective and continuous data at the end of the intervention timepoint, which had no significant differences, and for dichotomous data at the end of the intervention timepoint, which led to a slight decrease in the interventions’ effects. See Supplementary Figs. 8–11 for plots. Sensitivity analyses showed decreases in the effects by removing studies with an overall high risk of bias for subjective and continuous data at the end of the intervention (d = 0.163, CI = 0.074–0.251, I2 = 43.67%, k = 13) and for subjective and dichotomous data at the latest follow-up (RR = 1.585, CI = 1.152–2.180, I2 = 64.97%, k = 3), and increases for subjective and continuous data at the latest follow-up (d = 0.296, CI = −0.057–0.649, I2 = 86.28%, k = 5). There were increases in the effects when removing studies without a clear indication of the behaviors being targeted by the intervention for subjective and continuous data at the end of the intervention (d = 0.206, CI = 0.117–0.295, I2 = 47.74%, k = 16), and when removing studies with extremely long follow-up timepoints for subjective and continuous data at the latest follow-up timepoint (d = 0.256, CI = −0.080 to 0.592, I2 = 86.42%, k = 5). Removal of studies with a high risk of bias for subjective and dichotomous data at the latest follow-up timepoint led to a decrease in effects (RR = 1.585, CI = 1.152–180, k = 3). See Supplementary Figs. 12–16 for plots.

Change in Sedentary Behavior

End of intervention timepoint: Only one intervention provided an outcome for sedentary behavior that was subjective and continuous, and it had a large positive effect (d = 2.003, CI = 1.651–2.355, k = 1). Similarly, only one intervention provided an outcome for sedentary behavior that was subjective and dichotomous, and it also had a large positive effect (RR = 2.001, CI = 1.680–2.385, k = 1).

Latest follow-up timepoint: Only one intervention provided an outcome for sedentary behavior that was subjective and dichotomous, and it had a large positive effect (RR = 2.247, CI = 1.542–3.274, k = 1).

Change in Fruit and Vegetable Intake

End of intervention timepoint: Interventions providing subjective and continuous data on fruit and vegetable consumption showed small positive effects in changing this behavior (d = 0.232, CI = 0.013–0.452, I2 = 86.04%, k = 8). See Supplementary Fig. 17 for plot. For those providing subjective and dichotomous data, increased fruit and vegetable intake was more likely in the treatment than the control group (RR = 1.326, CI = 1.043–1.686, I2 = 87.93%, k = 7). See Supplementary Fig. 18 for plot.

Latest follow-up timepoint: Interventions providing subjective and continuous data on fruit and vegetable consumption showed a small positive effect in changing this behavior (d = 0.139, CI = 0.015–0.263, I2 = 0%, k = 3). See Supplementary Fig. 19 for plot. For the one intervention providing an outcome that was subjective and dichotomous, the desired outcome was more likely in the treatment group (RR = 2.045, CI = 1.863–2.246, k = 1).

Publication bias and sensitivity analyses: For fruit and vegetable intake, funnel plots indicated some asymmetry at both timepoints (end of intervention and latest follow-up). The use of the trim and fill method estimated three missing studies for subjective and continuous data at the end of the intervention, which led to a decrease in the interventions’ effects. The use of the trim and fill method estimated zero missing studies for subjective and dichotomous data at the end of the intervention and subjective and continuous data at the latest follow-up. Sensitivity analysis by removing studies with a high overall risk of bias led to a decrease in the effects for subjective and continuous/dichotomous data at the end of intervention (d = 0.091, CI = −0.021 to 0.204, k = 7 and RR = 1.204, CI = 0.991–1.463, k = 6, respectively), and by removing studies without a clear indication of the targeted behaviors there was a slight increase in effects for subjective and continuous data at the end of the intervention (d = 0.269, CI = 0.017–0.521, k = 7). See Supplementary Figs. 20–25 for plots.

Change in Fat Intake

End of the intervention timepoint: Interventions providing subjective and continuous fat consumption showed moderated positive effects in reducing fat intake (d = 0.436, CI = 0.199–0.674, I2 = 85.47%, k = 10). See Supplementary Fig. 26 for plot. Similarly, for interventions providing outcomes that were subjective and dichotomous, a reduction in fat intake was more likely in the treatment than the control group (RR = 1.286, CI = 0.896–1.845, I2 = 64.56%, k = 3). See Supplementary Fig. 27 for plot.

Latest follow-up timepoint: Interventions providing subjective and continuous data for fat intake revealed moderated positive effects in changing this behavior (d = 0.517, CI = 0.030–1.003, I2 = 93.07%, k = 5). See Supplementary Fig. 28. For interventions providing outcomes that were subjective and dichotomous, only one study had the desired outcome (RR = 1.367, CI = 1.176–1.588, k = 1).

Publication bias and sensitivity analyses: For fat intake, funnel plots indicated some asymmetry. The use of the trim and fill method estimated one missing study for subjective and dichotomous data at the end of the intervention timepoint and for subjective and continuous data at the latest follow-up timepoint. See Supplementary Figs. 29–31 for plots. Sensitivity analysis conducted by removing studies with an overall high risk of bias led to increases in the effects for subjective and continuous data at the end of the intervention timepoint and latest follow-up timepoint (d = 0.512, CI = 0.206–0.819, I2 = 90.03%, k = 7 and d = 0.590, CI = 0.165–1.015, I2 = 86.23%, k = 4, respectively). When removing studies that did not have a clear indication of the behaviors being targeted, the analysis led to a slight increase in subjective and continuous data at the end of the intervention (d = 0.488, CI = 0.233–0.744, I2 = 85.46%, k = 9). See Supplementary Figs. 32–34 for plots.

Change in Smoking Cessation

End of the intervention timepoint: Four studies assessing smoking cessation were used for the analysis with subjective and continuous data, and these had small negative effects in changing this behavior (d = −0.019, CI = −0.211 to 0.172, I2 = 19.41%, k = 4). See Supplementary Fig. 35 for plot. For interventions providing subjective and dichotomous outcomes, the desired outcome was more likely in the treatment than the control group (RR = 1.102, CI = 1.020–1.189, I2 = 77.63%, k = 12). See Supplementary Fig. 36 for plot. Five studies provided objective and dichotomous data and the desired outcome was more likely in the treatment than the control group (RR = 1.252, CI = 1.019–1.538, I2 = 65.35%, k = 5). See Supplementary Fig. 37 for plot.

Latest follow-up timepoint: One study provided subjective and continuous data with positive effects regarding smoking cessation (d = 0.228, CI = −0.211 to 0.668, k = 1). For interventions providing outcomes that were subjective and dichotomous, smoking cessation was more likely in the treatment than in the control group (RR = 1.006, CI = 0.893–1.134, I2 = 51.14%, k = 5). See Supplementary Fig. 37 for plot. For objective and dichotomous only two studies provided data on smoking cessation, and this was more likely in the treatment group (RR = 1.226, CI = 1.103–1.364, k = 2).

Publication bias and sensitivity analyses: For smoking cessation, at the end of the intervention timepoint, inspection of funnel plots indicated some asymmetry, and use of the trim and fill method estimated missing studies, with slight decreases. See Supplementary Figs. 39–41 for plots. Removal of one study with a high risk of bias led to slightly higher effects in smoking cessation for subjective and dichotomous data (RR = 1.081, CI = 1.002–1.167, I2 = 76.14%, k = 11), and removal of one study with an unclear behavioral target led to slightly higher effects in smoking cessation for subjective and dichotomous data (RR = 1.105, CI = 1.021–1.195, I2 = 79.64%, k = 11). See Supplementary Figs. 42 and 43 for plots.

Change in Alcohol Consumption

End of intervention timepoint: Studies assessing alcohol consumption used for the analysis with subjective and continuous data showed small positive effects in reducing alcohol consumption (d = 0.081, CI = −0.045 to 0.206, I2 = 15.35%, k = 6). See Supplementary Fig. 44 for plot. For interventions providing subjective and dichotomous outcomes, the desired outcome was more likely in the treatment than the control group (RR = 1.026, CI = 0.936–1.125, I2 = 55.11%, k = 5). See Supplementary Fig. 45 for plot.

Latest follow-up timepoint: Two studies assessing alcohol consumption were used for the analysis with subjective and continuous data, and these had positive effects in changing this behavior (d = 0.320, CI = −0.262 to 0.901, k = 2). One study provided data for subjective and dichotomous data and showed positive effects in reducing alcohol consumption (RR = 1.194, CI = 0.773–1.945, k = 1).

Publication bias and sensitivity analyses: For alcohol consumption at the end of the intervention timepoints, funnel plots indicated asymmetry and the trim and fill method estimated no missing studies for subjective and continuous data, and one missing study for subjective and dichotomous data, which had a small impact on the findings. See Supplementary Figs. 46 and 47 for plots. In the sensitivity analysis, removal of studies with an overall high risk of bias resulted in an increased reduction in alcohol consumption in both analyses (d = 0.092, CI = −0.032 to 0.216, I2 = 0%, k = 3 and RR = 1.045, CI = 0.908–1.203, I2 = 66.33%, k = 4), as did removing studies with an unclear behavioral target (d = 0.150, CI = −0.022 to 0.321, I2 = 34.25%, k = 3 and RR = 1.058, CI = 0.950–1.179, I2 = 55.30%, k = 4). See Supplementary Figs. 48–51 for plots.

Changes in Medication Adherence

End of intervention timepoint: Four studies assessing medication adherence were used for the analysis with subjective and continuous data, and these had positive effects in changing this behavior (d = 0.373, CI = 0.185–0.560, I2 = 3.67%, k = 4). See Supplementary Fig. 52 for plot. For the two studies that provided subjective and dichotomous outcomes, medication adherence was more likely in the treatment than the control group (RR = 1.047, CI = 1.010–1.086, k = 2).

Latest follow-up timepoint: The two studies that provided subjective and continuous data at the follow-up timepoint showed positive effects in changing medication adherence (d = 0.475, CI = 0.145–0.805, k = 2).

Publication bias and sensitivity analyses: For medication adherence, funnel plots indicated no asymmetry and the use of the trim and fill method estimated no missing study for subjective and continuous data at the end of the intervention timepoint. Sensitivity analysis by removing studies with unclear behavioral targets showed a smaller increase in medication adherence. See Supplementary Figs. 53 and 54 for plots.

Effectiveness of MHBC Interventions per Chronic Condition

Due to the limited number of studies available for each analysis, we were unable to conduct subgroup analyses based on the type of condition (i.e., cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, cancer, and one or more chronic conditions). Instead, effects were provided for each of these conditions and behaviors for reference. Please refer to Supplementary Tables 5–12 for the effect sizes of all behaviors in each condition.

For cardiovascular diseases, most analyses showed small to large positive effects for all behaviors (d = 0.131–1.749, RR = 1.066–2.247). The exception was for smoking cessation, objective and dichotomous data, at the end of the intervention (RR = 0.970), and subjective and dichotomous at the latest follow-up timepoint (RR = 0.921). However, some of these analyses only included one or two studies. For type 2 diabetes, at the end of the intervention timepoint, analyses showed small to large positive effects for all behaviors (d = 0.030–0.766, RR = 1.653). At the latest follow-up timepoint, analyses showed negative effects (d = −0.053 to −0.277, RR = 0.847), except for objective and continuous data (d = 0.894). However, most of these analyses only included one study. For hypertension, analyses for subjective and continuous data for physical activity, fruit and vegetable intake, and smoking cessation had negative effects (d = −0.121, d = −0.083, d = −0.371, respectively). All other analyses resulted in positive effects for all behaviors. However, all of these analyses included between one and three studies. For cancer, analyses showed small positive effects for all behaviors (d = 0.043–0.273, RR = 1.026–1.834). However, most of these analyses included only one study. For studies with one or more chronic conditions, analyses showed positive effects for all behaviors (d = 0.261–2.003, RR = 1.250–1.303), except for smoking cessation (RR = 0.900). However, all analyses included only one or two studies.

Discussion

This systematic review identified 61 randomized trials evaluating interventions that aim to support individuals with chronic conditions (cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, cancer and cancer survivors, one or more chronic conditions, and multiple conditions) to change more than one health behavior.

Findings from the meta-analyses indicated that interventions targeting multiple behavior changes can be effective in promoting positive changes across different behavioral domains in the context of chronic disease management. Specifically, these interventions resulted in increased levels of physical activity, reduced sedentary behavior, improved dietary habits by increasing fruit and vegetable intake and decreasing fat intake, reduced alcohol consumption, and improved medication adherence. These positive effects were observed when compared to control conditions not only immediately after the intervention but also during follow-up periods, indicating their potential sustained impact. In relation to smoking cessation, the interventions showed positive effects at later follow-up timepoints, but immediate outcomes showed small negative effects for continuous data.

The findings on diet and physical activity are consistent with previous reviews that have demonstrated the effectiveness of MHBC interventions in improving these behaviors [14, 15, 31]. The two reviews found on MHBC interventions that conducted a meta-analysis for the behavioral domain “smoking cessation,” found no evidence of reductions in smoking behavior [16] and small positive effects [14]. As most reviews on MHBC interventions have not conducted meta-analyses with behavioral outcomes, further research is needed to gain a comprehensive understanding of the effectiveness of these interventions in changing behaviors such as smoking habits, alcohol consumption, and medication adherence.

A previous study synthesizing reviews and meta-analyses of interventions aiming to change diet and physical activity suggested that single behavior change approaches may be more effective in altering diet and physical activity [32]. Whereas a meta-analysis of research reports found that targeting a moderate number of behavioral recommendations (two to three) to be most effective [33]. Still, the absence of comparative studies of these approaches (i.e., MHBC interventions vs. single behavior change interventions) prevents any conclusive claims. Similarly, in our review, only one study had a comparison group characterized as a “single behavior change intervention” [30], limiting our ability to ascertain which approach is more effective and to determine whether there are any costs associated with focusing attention and efforts on multiple behavioral changes.

Among the interventions analyzed, “physical activity, diet and smoking” was the most frequently targeted behavioral cluster. Previous reviews have focused on specific behavioral clusters in terms of their scopes [15, 17–19], with “diet and physical activity” being the most common one [15, 17, 18]. However, understanding which behaviors tend to cluster together and how they correlate to each other can provide important data to inform the development of interventions tailored to specific populations and their behavioral “profile” [12, 34].

In terms of the type of MHBC intervention (i.e., simultaneous vs. sequential), limited research has examined this specific question. Still, the available evidence on randomized trials from a narrative review [11] and a systematic review and meta-analysis [35] suggests that there is no significant difference in the effectiveness between these two types of MHBC interventions. Among the interventions included in this review, most aimed to change behaviors simultaneously across all conditions, while only a smaller number adopted a sequential approach. Notably, a significant number of studies did not provide sufficient information to determine whether they employed a sequential or simultaneous approach. The poor reporting of included studies and the low utilization of sequential designs inhibit us from thoroughly assessing the impact of intervention design on efficacy.

Finally, it is interesting to note that the reported outcomes displayed slightly higher effects at the latest follow-up timepoints compared to those immediately after the intervention, with the exception of fruit and vegetable consumption. Caution is needed when interpreting these results, as there were fewer studies included in the latest follow-up analyses and due to the high heterogeneity in many of the analyses. Still, this raises the question of whether the more behavioral changes are targeted, the more enduring the effects may be. Interestingly, a systematic review of randomized controlled trials in adults with obesity revealed that focusing on a single behavior yielded greater long-term effects on behavior change, whereas targeting both diet and physical activity together resulted in greater long-term weight loss [36]. Further investigation is needed to provide a clearer understanding of the sustained impact of MHBC interventions across different behavioral clusters.

This review provides valuable insights into MHBC interventions targeting individuals with chronic conditions. Unlike previous reviews [11, 14–19], this study focused on multiple chronic conditions across various behavioral domains. This review focused on behavioral outcomes, rather than indirect measures of behavior change intervention effectiveness. This emphasis on behavioral outcomes is key, as without understanding whether the behaviors are actually being modified, we cannot determine if these changes are resulting in improved clinical outcomes. This review contributes to the advancement of this area by employing systematic decision rules for the selection and analysis of behavioral domains, addressing the absence of specific guidelines for conducting analyses in the field of MHBC interventions.

Some limitations should be noted. First, it is possible that our search may have missed relevant studies, as some studies were identified through previous reviews rather than solely through our search strategy. This may be attributed to the fact that intervention studies often do not explicitly use the term “multiple health behavior change,” instead referring to the specific behaviors they target (e.g., “diet and physical activity intervention”) or using broader terms such as “lifestyle interventions.” Also, when focusing our search on “chronic conditions”-related terms, and by not using specific conditions’ names (e.g., type 2 diabetes), we may have also missed studies of interest. This limitation highlights the need for the use of a shared language/nomenclature in this field to facilitate the dissemination of findings.

One of the challenges of this review was the selection of outcomes for each behavioral domain. The high heterogeneity observed in the aspects of the behavioral domains (in particular for diet and physical activity), along with the variety of measurement approaches, and presentation of statistical data, posed difficulties and limited the interpretation and comparability of results across studies. This emphasizes the need for the development and use of valid measures to capture multiple health behaviors comprehensively [10]. Additionally, the establishment of core outcome sets, which define a standardized set of outcomes to be reported in all studies within a specific research area [37], could enhance the comparability and synthesis of findings in future research. These limitations highlight the challenges, and ultimately the opportunities, for the development of a science of multiple behavior change and of how it is reported to build towards a more cumulative evidence base.

Similar to findings in other reviews (e.g., [15]), a majority of the included studies in this review did not provide protocol or trial registration information, which hampers the assessment of study design and potential biases. Additionally, important details such as primary outcomes were often unclear. This absence of a priori power analysis and inadequate reporting of study protocols can compromise the reliability and validity of the findings. Also, caution should be exercised when interpreting the results of this review, due to the high heterogeneity observed among the included studies and the limited number of studies available for certain analyses.

Conclusion

In the context of chronic disease management, change in more than one health behavior is often recommended to achieve better health outcomes. This systematic review and meta-analysis shed light on the landscape of MHBC interventions targeting individuals with chronic conditions and indicates that these interventions can improve health-related behaviors.

The findings emphasize the predominance of interventions that aim to change multiple behaviors simultaneously, with “diet, physical activity and smoking” being the most targeted cluster. Moving forward, it will be important to improve the quality of MHBC interventions by (i) providing detailed protocols and/or trial registrations with information on intervention components and primary and secondary outcomes, (ii) testing different types of MHBC interventions (simultaneous vs. sequential) and targeting different behavioral clusters tailored to the populations behavioral “profile,” (iii) developing and using standardized outcome measures, such as core outcome sets, to facilitate comparability and synthesis of results across studies, and (iv) conducting a more in-depth analysis into the components of these interventions (e.g., mode of delivery) to gain a better understanding of what works for whom, in which context, how, and why. Adopting these steps will contribute to advancing the effectiveness and scientific rigor of MHBC interventions in promoting behavior change among individuals with chronic conditions.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Carolina C Silva, Trinity Centre for Practice and Healthcare Innovation (TCPHI), School of Nursing and Midwifery, Trinity College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland.

Justin Presseau, Clinical Epidemiology Program, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, ON, Canada; School of Epidemiology and Public Health, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada; School of Psychology, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada.

Zack van Allen, Clinical Epidemiology Program, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, ON, Canada; School of Psychology, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada.

Paulina M Schenk, Centre for Behaviour Change, University College London, London, England, UK.

Maiara Moreto, ISPA - Instituto Universitário, Lisbon, Portugal.

John Dinsmore, Trinity Centre for Practice and Healthcare Innovation (TCPHI), School of Nursing and Midwifery, Trinity College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland.

Marta M Marques, NOVA National School of Public Health, Comprehensive Health Research Centre (CHRC), NOVA University of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal.

Funding

CCS is supported by FCT-Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (grant number SFRH/BD/146762/2019).

Role of the Funder

The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Authors’ Statement of Conflict of Interest and Adherence to Ethical Standards The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Authors’ Contributions Carolina C. Silva (Conceptualization [equal]; Data curation [lead]; Formal analysis [lead]; Investigation [lead]; Methodology [lead]; Project administration [lead]; Resources [lead]; Visualization [lead]; Writing – original draft [lead]; Writing – review & editing [equal]), Justin Presseau (Conceptualization [equal]; Methodology [supporting]; Supervision [equal]; Writing – original draft [supporting]; Writing – review & editing [equal]), Zack van Allen (Conceptualization [supporting]; Methodology [supporting]; Writing – original draft [supporting]; Writing – review & editing [equal]), Paulina Schenk (Investigation [supporting]; Writing – review & editing [equal]), Maiara Moreto (Investigation [supporting]; Writing – review & editing [supporting]), John Dinsmore (Conceptualization [equal]; Supervision [equal]; Writing – review & editing [equal]), and Marta M. Marques (Conceptualization [equal]; Investigation [supporting]; Methodology [supporting]; Supervision [equal]; Writing – original draft [supporting]; Writing – review & editing [equal])

Systematic Review Pre-registration PROSPERO (CRD42022327085) and Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/hr7u3).

Transparency Statements

Study registration: The study was pre-registered at PROSPERO (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=327085) and Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/hr7u3). Analytic plan pre-registration: The analysis plan was registered prior to beginning data collection at PROSPERO (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=327085)

Data Availability

Extracted data for this study are available in Supplementary Materials and Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/abe92/). Analytic code availability: There is no analytic code associated with this study. Materials availability: Some of the materials used to conduct the study are available at Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/abe92/).

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Noncommunicable diseases. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases. May 1, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hajat C, Stein E.. The global burden of multiple chronic conditions: A narrative review. Prev Med Rep. 2018; 12:284–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Budreviciute A, Damiati S, Sabir DK, et al. Management and prevention strategies for non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and their risk factors. Front Public Health. 2020; 8:574111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Michie S. Designing and implementing behaviour change interventions to improve population health. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2008; 13(3):64–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nigg CR, Long CR.. A systematic review of single health behavior change interventions vs. multiple health behavior change interventions among older adults. Transl. Behav. Med. 2012; 2(2):163–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Karam G, Agarwal A, Sadeghirad B, et al. Comparison of seven popular structured dietary programmes and risk of mortality and major cardiovascular events in patients at increased cardiovascular risk: Systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2023; 380:e072003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kettle VE, Madigan CD, Coombe A, et al. Effectiveness of physical activity interventions delivered or prompted by health professionals in primary care settings: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2022; 376:e068465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Smith P, Poole R, Mann M, Nelson A, Moore G, Brain K.. Systematic review of behavioural smoking cessation interventions for older smokers from deprived backgrounds. BMJ Open. 2019; 9(11):e032727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Madigan CD, Graham HE, Sturgiss E, et al. Effectiveness of weight management interventions for adults delivered in primary care: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2022; 377:e069719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Geller K, Lippke S, Nigg CR.. Future directions of multiple behavior change research. J Behav Med. 2017; 40(1):194–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Prochaska JJ, Prochaska JO.. A review of multiple health behavior change interventions for primary prevention. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2011; 5(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. van Allen Z, Bacon SL, Bernard P, et al. Clustering of Health Behaviors in Canadians: A multiple behavior analysis of data from the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging. Ann Behav Med. 2023; 57(8):662–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Prochaska JJ, Spring B, Nigg CR.. Multiple health behavior change research: An introduction and overview. Prev Med. 2008; 46(3):181–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Meader N, King K, Wright K, et al. Multiple risk behavior interventions: Meta-analyses of RCTs. Am J Prev Med. 2017; 53(1):e19–e30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Duan Y, Shang B, Liang W, Du G, Yang M, Rhodes RE.. Effects of eHealth-based multiple health behavior change interventions on physical activity, healthy diet, and weight in people with noncommunicable diseases: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2021; 23(2):e23786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Alageel S, Gulliford MC, McDermott L, Wright AJ.. Multiple health behaviour change interventions for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in primary care: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2017; 7(6):e015375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cradock KA, ÓLaighin G, Finucane FM, Gainforth HL, Quinlan LR, Ginis KAM.. Behaviour change techniques targeting both diet and physical activity in type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phy Act. 2017; 14(1):18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Spark LC, Reeves MM, Fjeldsoe BS, Eakin EG.. Physical activity and/or dietary interventions in breast cancer survivors: A systematic review of the maintenance of outcomes. J Cancer Surviv. 2013; 7(1):74–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Minian N, Corrin T, Lingam M, et al. Identifying contexts and mechanisms in multiple behavior change interventions affecting smoking cessation success: A rapid realist review. BMC Public Health. 2020; 20(1):918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bernell S, Howard SW.. Use your words carefully: What is a chronic disease? Front Public Health. 2016; 4:159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sutton A, Crew A, Wysong A.. Redefinition of skin cancer as a chronic disease. JAMA Dermatol. 2016; 152(3):255–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kendall JM. Designing a research project: Randomised controlled trials and their principles. Emerg Med J. 2003; 20(2):164–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A.. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016; 5(1):210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 2012; 22(3):276–282. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sterne JAC, Savovic J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019; 366:l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Brüggemann P, Rajguru K.. Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA) 3.0: A software review. J Market Anal. 2022; 10:425–429. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Glasgow RE, Kurz D, King D, et al. Twelve-month outcomes of an internet-based diabetes self-management support program. Patient Educ Couns. 2012; 87(1):81–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hyman DJ, Pavlik VN, Taylor WC, Goodrick GK, Moye L.. Simultaneous vs. sequential counseling for multiple behavior change. Arch Intern Med. 2007; 167(11):1152–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Liu S, Brooks D, Thomas SG, Eysenbach G, Nolan RP.. Effectiveness of user- and expert-driven web-based hypertension programs: An RCT. Am J Prev Med. 2018; 54(4):576–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Swoboda CM, Miller CK, Wills CE.. Setting single or multiple goals for diet and physical activity behaviors improves cardiovascular disease risk factors in adults with type 2 diabetes: A Pragmatic Pilot Randomized Trial. Diabetes Educ. 2016; 42(4):429–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nitschke E, Gottesman K, Hamlett P, et al. Impact of nutrition and physical activity interventions provided by nutrition and exercise practitioners for the adult general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2022; 14(9):1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sweet SN, Fortier MS.. Improving physical activity and dietary behaviours with single or multiple health behaviour interventions? A synthesis of meta-analyses and reviews. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2010; 7(4):1720–1743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wilson K, Senay I, Durantini M, et al. When it comes to lifestyle recommendations, more is sometimes less: A meta-analysis of theoretical assumptions underlying the effectiveness of interventions promoting multiple behavior domain change. Psychol Bull. 2015; 141(2):474–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shaw BA, Agahi N.. A prospective cohort study of health behavior profiles after age 50 and mortality risk. BMC Public Health. 2012; 12:803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. James E, Freund M, Booth A, et al. Comparative efficacy of simultaneous versus sequential multiple health behavior change interventions among adults: A systematic review of randomised trials. Prev Med. 2016; 89:211–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dombrowski SU, Avenell A, Sniehott FF.. Behavioural interventions for obese adults with additional risk factors for morbidity: Systematic review of effects on behaviour, weight and disease risk factors. Obes Facts. 2010; 3(6):377–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Williamson PR, Altman DG, Bagley H, et al. The COMET Handbook: Version 1.0. Trials. 2017; 18(Suppl 3):28C0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Extracted data for this study are available in Supplementary Materials and Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/abe92/). Analytic code availability: There is no analytic code associated with this study. Materials availability: Some of the materials used to conduct the study are available at Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/abe92/).