Abstract

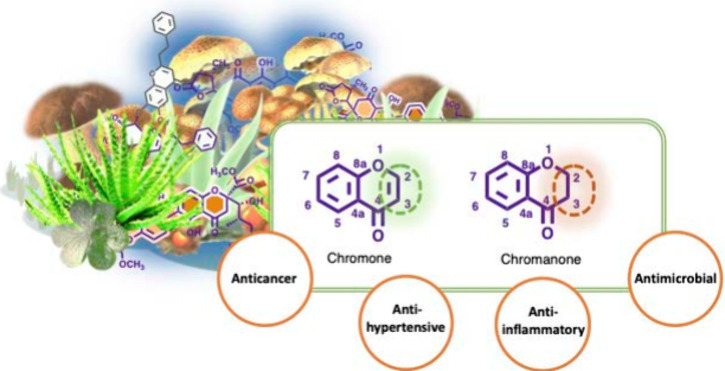

Emerging threats to human health require a concerted effort to search for new treatment therapies. One of the biggest challenges is finding medicines with few or no side effects. Natural products have historically contributed to major advances in the field of pharmacotherapy, as they offer special characteristics compared to conventional synthetic molecules. Interest in natural products is being revitalized, in a continuous search for lead structures that can be used as models for the development of new medicines by the pharmaceutical industry. Chromone and chromanones are recognized as privileged structures and useful templates for the design of diversified therapeutic molecules with potential pharmacological interest. Chromones and chromanones are widely distributed in plants and fungi, and significant biological activities, namely antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antiviral, etc., have been reported for these compounds, suggesting their potential as lead drug candidates. This review aims to update the literature published over the last 6 years (2018–2023) regarding the natural occurrence and biological activity of chromones and chromanones, highlighting the recent findings and the perspectives that they hold for future research and applications namely in health, cosmetic, and food industries.

1. Introduction

Nature has been a source of medicinal products for millennia and continues to be a rich pool of new chemical entities. Natural products continue to play a key role in the discovery of scaffolds with high structural diversity and varied bioactivities, boosting the finding of new structures that can lead to the development of effective agents for a variety of human diseases. Natural product-derived molecules are numbers 1 and 4 in the USA sales chart up through the end of 2017, with total sales in the USA from 1992 to 2017 of $163.77 billion.1

In addition to the discovery of new chemical entities for therapeutic application, natural products constitute an important basis for the selection of potential lead compounds for the development of new and more effective drugs through tailored structural modifications.1−3

Plants and fungi have provided or inspired the development of many pharmaceuticals for infection, cancer, pain, heart, and immunomodulation diseases.4 Plants and fungi are the source of some of the most important drugs presently used in clinic, including some so chemically complex that they may never have been discovered without natural product research.4 Thus, scientific evaluation of plants and fungi for their medicinal or other uses is fundamental to increase our armory against global health challenges.5−7

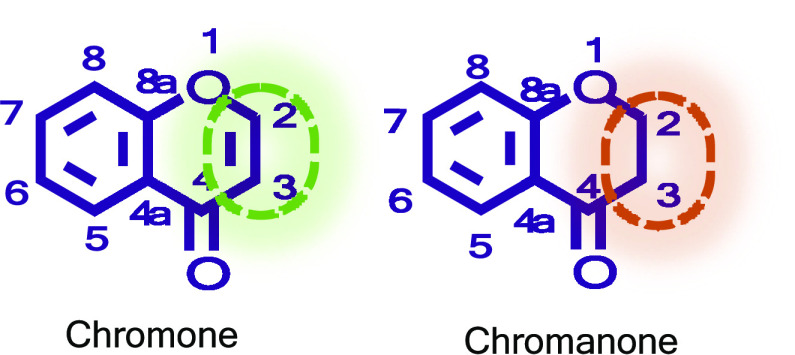

Chromones (4H-chromen-4-ones, 4H-1-benzopyran-4-ones, or benzo-γ-pyrones) and chromanones (4-chromanones, chroman-4-ones, or 2,3-dihydro-1-benzopyran-4-one) constitute an important class of oxygen-containing heterocyclic compounds that are ubiquitous in nature (Figure 1).8 Along with many other natural compounds, chromones and chromanones are active in various stages of plant life cycle namely growth regulation, control of respiration and photosynthesis, morphogenesis, and sex determination, ensuring pollination and plant reproduction as well as providing protection against fungal pathogens or ultraviolet radiation.9−11 Chromone and analogues exhibit a wide range of pharmacological activities, including antifungal, antimicrobial, anticancer, antiviral, antihypertensive, and anti-inflammatory activities and the ability to inhibit several enzymes.10,11 In addition to their various therapeutic uses, they have been found as important building blocks and intermediates in many organic reactions.12,13

Figure 1.

Chromone and chromanone’s chemical scaffold.

The importance of chromone scaffold in drug discovery and its potential therapeutic application has been reviewed in detail.14−16 This review provides the reader with an update to our previous articles titled “Chromone: A Valid Scaffold in Medicinal Chemistry” (Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 4960–4992) and “Chromone as a Privileged Scaffold in Drug Discovery: Recent Advances” (J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 7941–7957), and focuses primarily on chromones and chromanones isolated from natural products, given the relevance of this source for the discovery of new lead compounds in drug discovery research.8,14

Given the structural similarity between chromones and chromanones (Figure 1), it was considered useful to also include in this review the new chromanones isolated from natural products during this period. Although structurally related, the absence of a double bond in the chromanone between C-2 and C-3 can result in significant variations in their biological activity.

The literature survey was conducted using multiple electronic databases including SciFinder, PubMed, and Web of Science.

2. Chromones and Chromanones from Natural Sources

Chromones and chromanones are widely distributed in many plant genera and, to a lesser extent, in some fungal species and other natural sources.4

A large number of chromone-based compounds have been isolated from natural sources.4,17−19 However, throughout this review emphasis is given to the novel chromones and chromanones isolated for the first time from natural sources (Table 1). Chromones/chromanones previously synthesized or isolated from natural sources but reported for the first time from a newer natural source are also included in Table 1.

Table 1. Novel Chromones and Chromanones Isolated from Natural Sources.

| Compound | Natural source | Biological activity | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plants | |||

| Aquisinenone A (1) | Aquilaria sinensis | Inhibition of NO production | (24) |

| (−)-4′-Methoxyaquisinenone A (2) | |||

| Aquisinenone B (3) | |||

| (−)-6″-Hydroxyaquisinenone B (4) | |||

| (+)-6″-Hydroxy-4′,4‴-dimethoxyaquisinenone B (5) | |||

| Aquisinenone C (6) | |||

| (−)-Aquisinenone D (7) | |||

| 4′-Demethoxyaquisinenone D (8) | |||

| (+)-Aquisinenone E (9) | |||

| (−)-Aquisinenone F (10) | |||

| (−)-Aquisinenone G (11) | |||

| (+)-4′-Methoxyaquisinenone G (12) | |||

| (5R,6S,7S,8R)-2-[2-(3′-Hydroxy-4′-methoxyphenyl)ethyl]-5,6,7,8-tetrahydroxy-5,6,7,8-tetrahydrochromone (14) | Aquilaria sp. | PDE 3A inhibitory activity | (25) |

| (5R,6S,7S,8R)-2-[2-(4′-Methoxyphenyl)ethyl]-5,6,7,8-tetrahydroxy-5,6,7,8-tetrahydrochromone (15) | |||

| (5R,6S,7S,8R)-2-[2-(4′-Hydroxyl-3′-methoxyphenyl)ethyl]-5,6,7,8-tetrahydroxy-5,6,7,8-tetrahydrochromone (16) |

| Compound | Natural source | Biological activity | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plants | |||

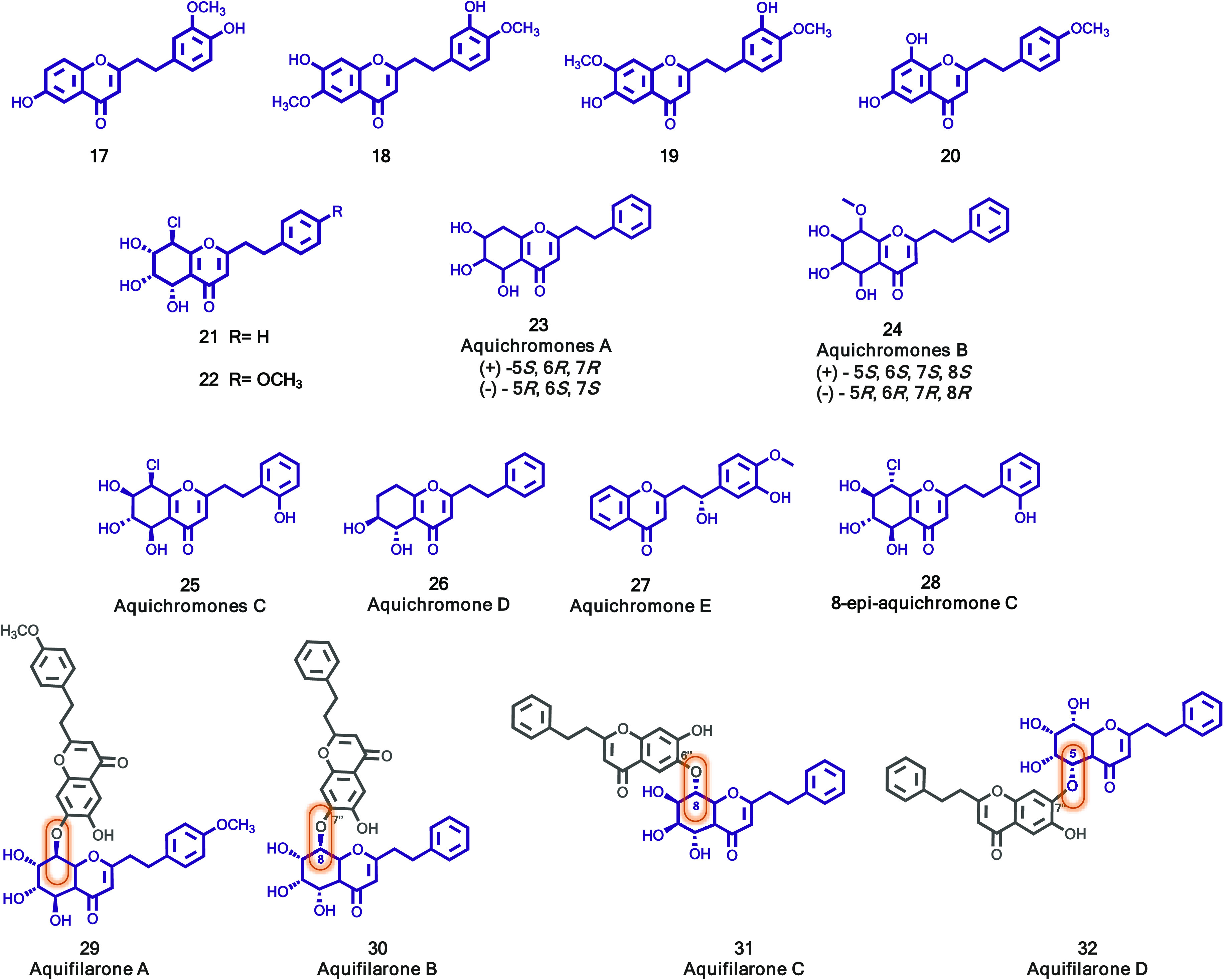

| 6-Hydroxy-2-[2-(3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenyl)ethyl]chromone (17) | Aquilaria sp. | Tyrosinase inhibitory activity | (26) |

| 6-Methoxy-7-hydroxy-2-[2-(3-hydroxy-4-methoxyphenyl)ethyl]chromone (18) | |||

| 6-Hydroxy-7-methoxy-2-[2-(3-hydroxy-4-methoxyphenyl)ethyl] chromone (19) | |||

| 6,8-Dihydroxy-2-[2-(4-methoxyphenyl)ethyl]chromone (20) | |||

| 8-Chloro-2-(2-phenylethyl)-5,6,7-trihydroxy-5,6,7,8-tetrahydrochromone (21) | |||

| 8-Chloro-2–(2-(4-methoxyphenyl)ethyl)-5,6,7-trihydroxy-5,6,7,8-tetrahydrochromone (22) | |||

| Aquichromone A (23) | Aquilaria sinensis | Inhibition of NO production | (27) |

| Aquichromone B (24) | |||

| Aquichromone C (25) | |||

| Aquichromone D (26) | |||

| Aquichromone E (27) | |||

| 8-Epi-aquichromone C (28) | |||

| Aquifilarone A (29) | Aquilaria filaria | Inhibition of NO production | (28) |

| Aquifilarone B (30) | |||

| Aquifilarone C (31) | |||

| Aquifilarone D (32) |

| Compound | Natural source | Biological activity | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plants | |||

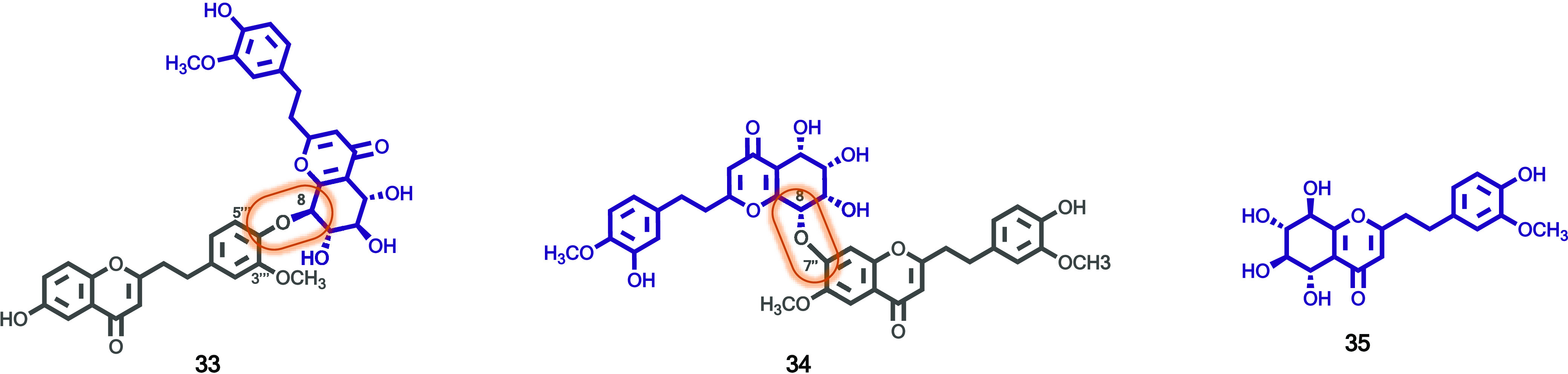

| Aquilasinenone L (33) | Aquilaria sinensis | —a | (29) |

| Aquilasinenone N (34) | |||

| 5S, 6R, 7S, 8R-Tetrahydroxy-[2-(3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenyl)ethyl]- 5,6,7,8-tetrahydrochromone (35) | |||

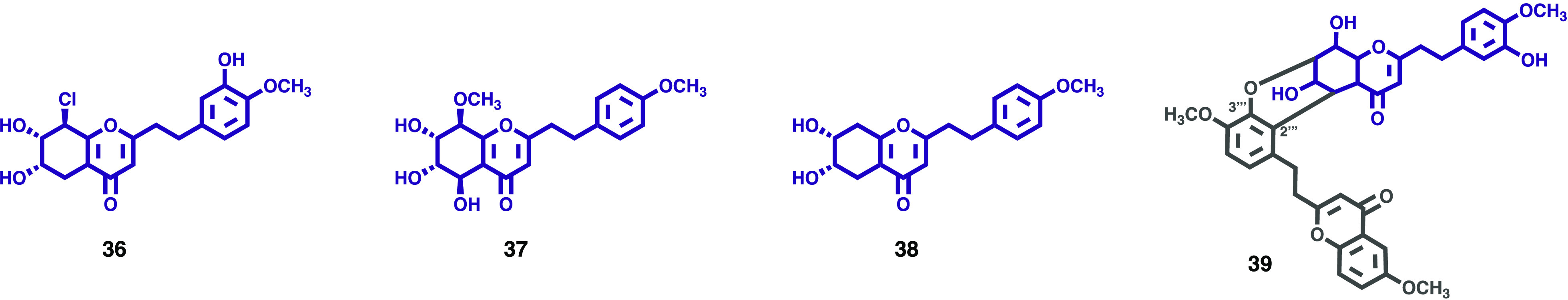

| (6S,7S,8R)-6,7-Dihydroxy-8-chloro-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-2-(2-(3-hydroxy-4-methoxyphenyl)ethyl)chromone (36) | Aquilaria crassna Pierre ex Lecomte | Weak cytotoxicity toward HeLa cell line | (30) |

| (5R,6S,7S,8R)-5,6,7-Trihydroxy-8-methoxy-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-2-(2-(4-methoxyphenyl)ethyl)chromone (37) | |||

| 6,7-cis-Dihydroxy-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-2-(2-(4-methoxyphenyl)ethyl)chromone (38) | |||

| 3′-Hydroxyaquisinenone D (39) | |||

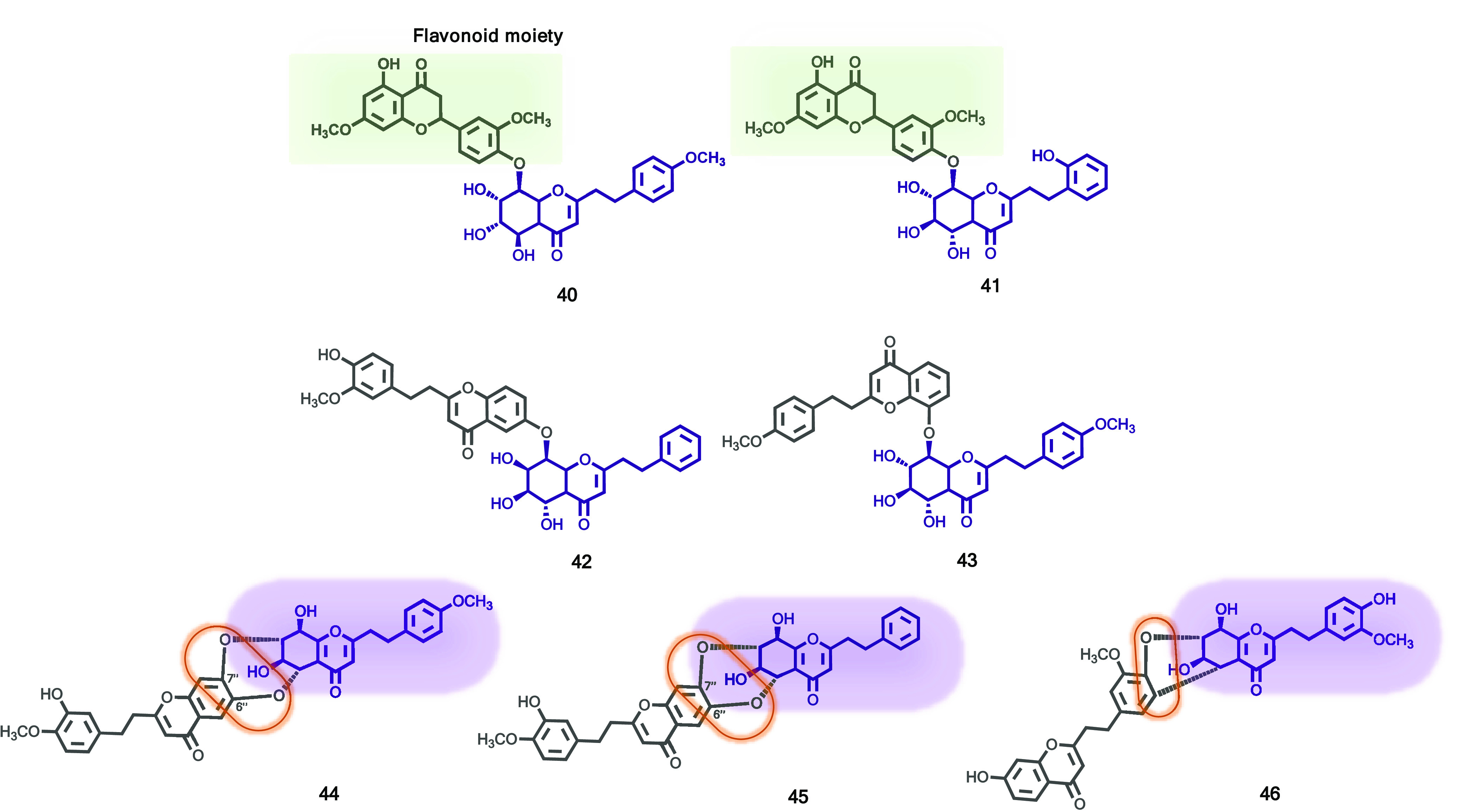

| Wallone B (40) | Aquilaria walla | Cytotoxicity against human cancer cell lines (K562, BEL-7402, SGC-7901, A549, HeLa) | (31) |

| Wallone C (41) | |||

| Wallone D (42) | |||

| 6″-Hydroxy-4′′′-methoxy-crassin B (43) | |||

| 3′′′-Hydroxy-crassin G (44) | |||

| 4′-Demethoxyl-3′′′-hydroxy-crassin G (45) | |||

| 3′-Methoxyl-4′,7″-dihydroxyl-6″-demethoxy-crassin H (46) | |||

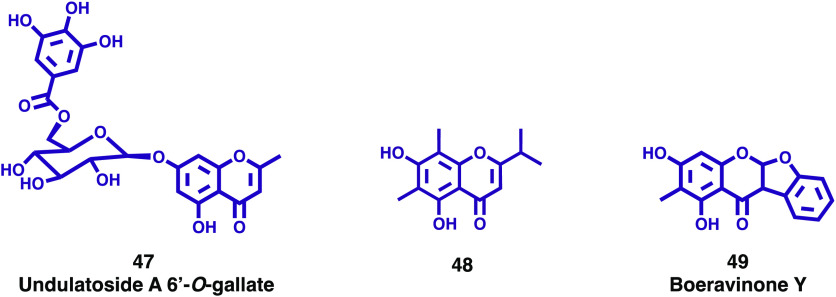

| Undulatoside A 6′-O-gallate (47) | Myrtus communis | —a | (33) |

| 5,7-Dihydroxy-2-isopropyl-6,8-dimethyl-4H-chromen-4-one (48) | Syzygium cerasiforme (Blume) Merr. and L.M. Perry | Inhibition of NO production | (35) |

| Compound | Natural source | Biological activity | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plants | |||

| 9,11-Dihydroxy-10-methylcoumarinochromone (boeravinone Y, 49) | Abronia nana | Inhibition of LPS release HMGB1; reduction of hyperpermeability, leukocyte adhesion and migration, and cell adhesion molecule expression; increase of the phagocytic activity of macrophages; and bacterial clearance effects | (36) |

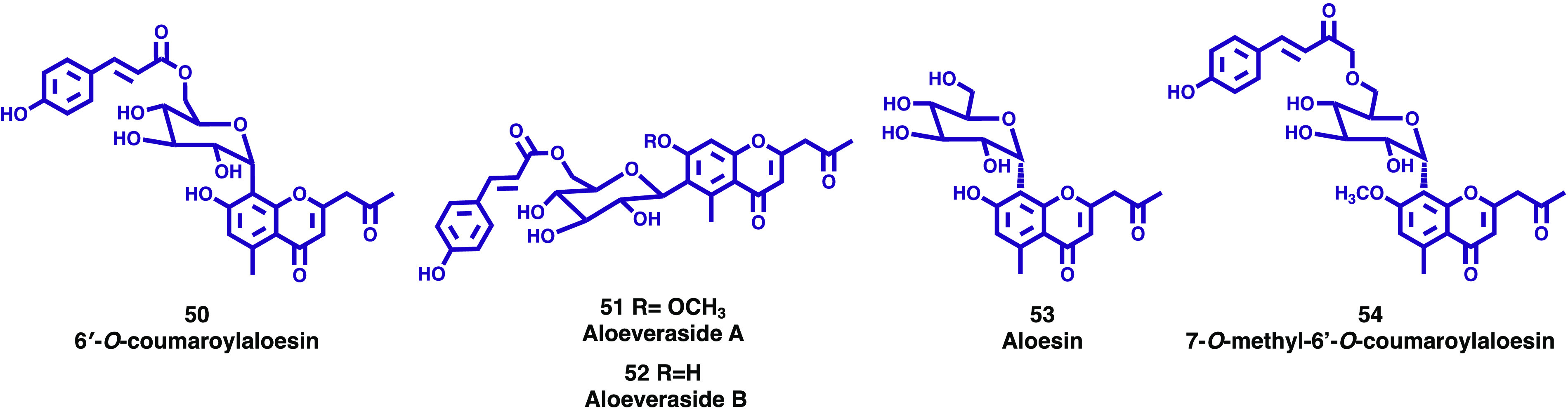

| 6′-O-Coumaroylaloesin (50) | Aloe vera | Anti-LPS activity | (38) |

| Aloeveraside A (51) | |||

| Aloeveraside B (52) | |||

| 7-O-Methyl-6′-O-coumaroylaloesin (54) | Aloe monticola Reynolds | Antibacterial and antifungal activity | (39) |

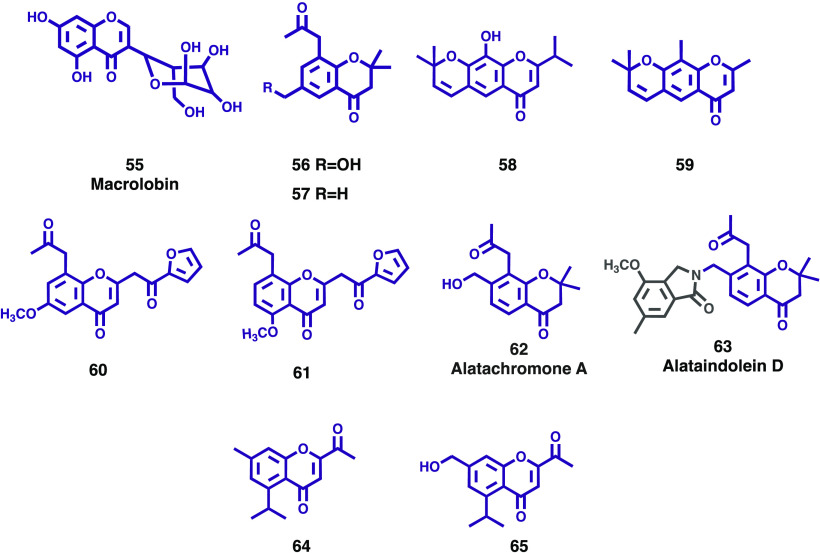

| 5,7-Dihydroxychromone-3α-D-C-glucoside (macrolobin, 55) | Macrolobium Latifolium Vogel | AChE inhibitory activity; antibacterial activity against P. aeruginosa and S. enterica | (42) |

| 6-(Hydroxymethyl)-2,2-dimethyl-8-(2-oxopropyl)chroman-4-one (56) | Cassia pumila | Anti-MRSA activity | (44) |

| 2,2,6-Trimethyl-8-(2-oxopropyl)chroman-4-one (57) | |||

| 6-(2,2-Dimethyl-2H-chromene)-2-isopropyl-8-hydroxy-4H-chromen-4-one (58) | Cassia auriculata | Anti-MRSA activity; anti-TMV activity; and antirotavirus activity | (45 and 46) |

| 6-(2,2-Dimethyl-2H-chromene)-2,8-dimethyl-4H-chromen-4-one (59) | |||

| 2-(2-(Furan-2-yl)-2-oxoethyl)-6-methoxy-8-(2-oxopropyl)-chromone (60) | |||

| 2-(2-(Furan-2-yl)-2-oxoethyl)-5-methoxy-8-(2-oxopropyl)-chromone (61) |

| Compound | Natural source | Biological activity | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plants | |||

| Alatachromone A (62) | Cassia alata | Anti-TMV activity; antirotavirus activity | (47) |

| Alataindolein D (63) | |||

| 2-Acetyl-5-isopropyl-7-methyl-4H-chromen-4-one (64) | cassia rotundifolia | Anti-MRSA activity | (48) |

| 2-Acetyl-7-(hydroxymethyl)-5-isopropyl-4H-chromen-4-one (65) | |||

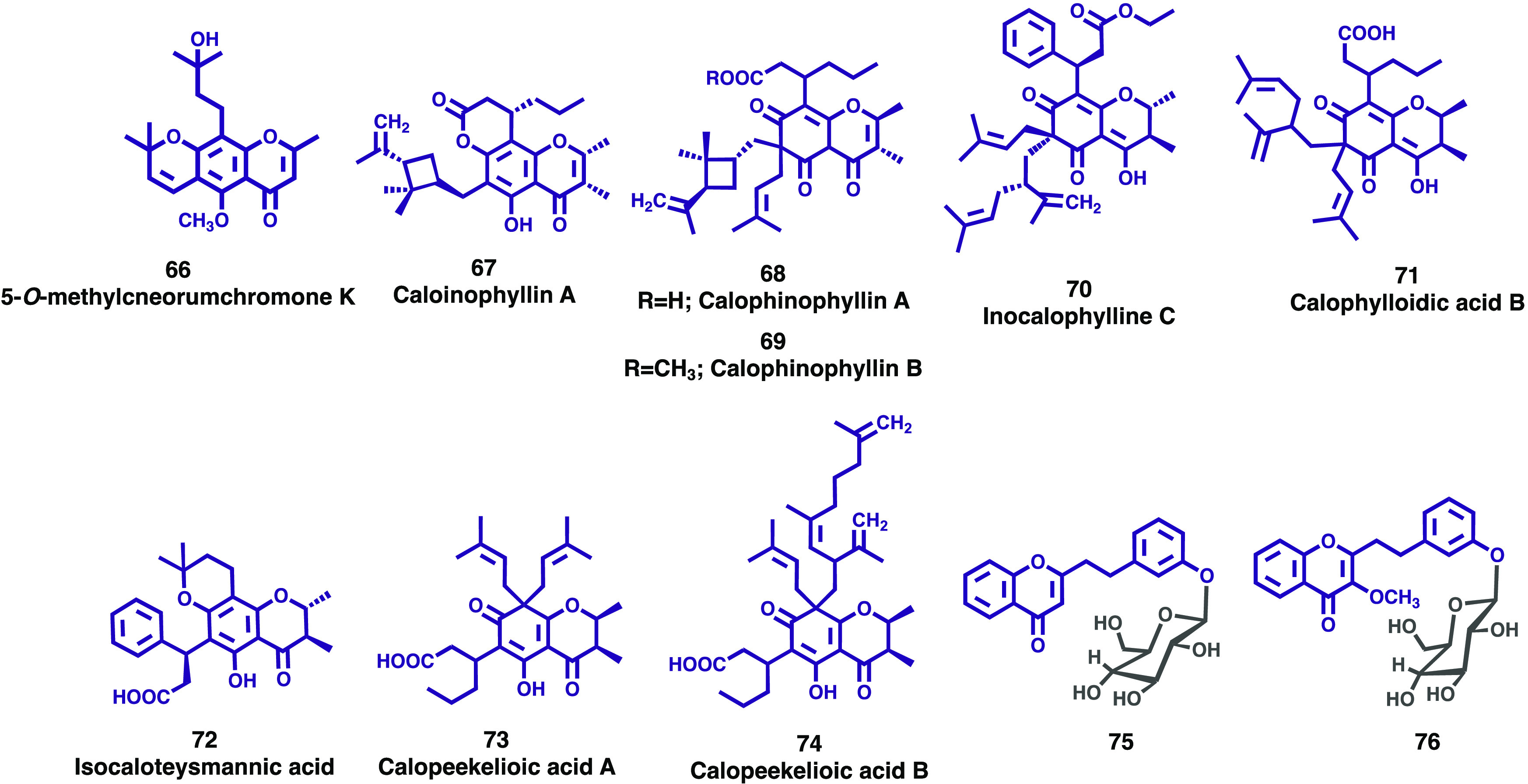

| Caloinophyllin A (67) | Calophyllum inophyllum | Antibacterial activity against S. aureus and E. coli | (52−55) |

| Calophinophyllin A (68) | |||

| Calophinophyllin B (69) | |||

| Inocalophylline C (70) | |||

| Calophylloidic acid B (71) | |||

| Isocaloteysmannic acid (72) | Calophyllum tacamahaca Willd | Moderate cytotoxicity against HepG2 and HT29 cell lines | (56) |

| Calopeekelioic acid A (73) | Calophyllum peekelii Lauterb | Antiplasmodial activity | (57) |

| Calopeekelioic acid B (74) | |||

| 2-{2-[(3′-O-β-d-Glucopyranosyl)phenyl]ethyl}chromone (75) | Limacia scandens | Senolytic activity | (58) |

| 3-Methoxy-2-{2-[(3′-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl)phenyl]ethyl}chromone (76) | |||

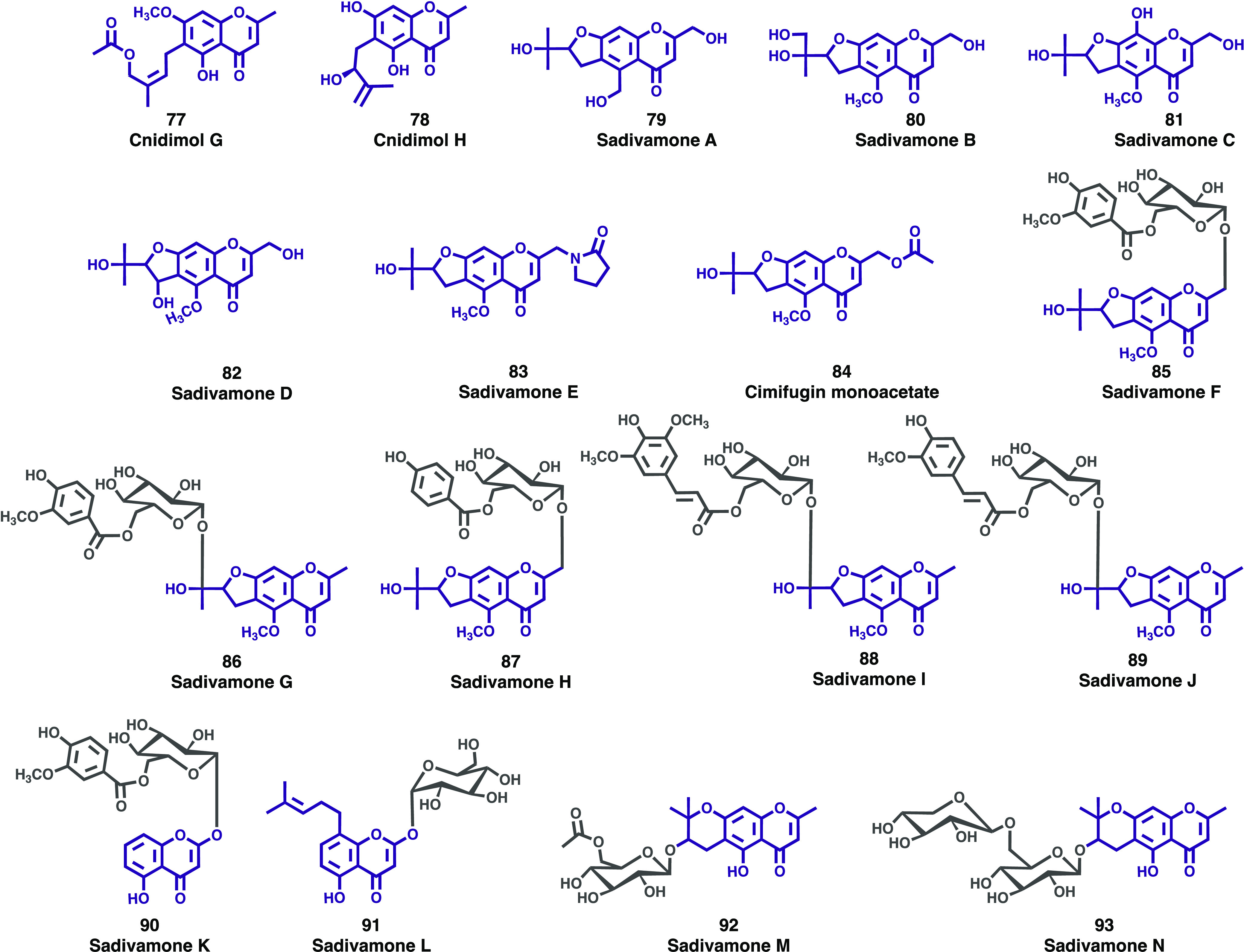

| Cnidimol G (77) | Cnidium monnieri (L.) Cusson | Inhibition of NO production | (60) |

| Cnidimol H (78) |

| Compound | Natural source | Biological activity | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plants | |||

| Sadivamone A (79) | Saposhnikovia divaricata | Inhibition of NO production; inhibition of phosphorylation of ERK and the activation of ERK and JNK signaling | (61) |

| Sadivamone B (80) | |||

| Sadivamone C (81) | |||

| Sadivamone D (82) | |||

| Sadivamone E (83) | |||

| Cimifugin monoacetate (84) | |||

| Sadivamone F (85) | |||

| Sadivamone G (86) | |||

| Sadivamone H (87) | |||

| Sadivamone I (88) | |||

| Sadivamone J (89) | |||

| Sadivamone K (90) | |||

| Sadivamone L (91) | |||

| Sadivamone M (92) | |||

| Sadivamone N (93) | |||

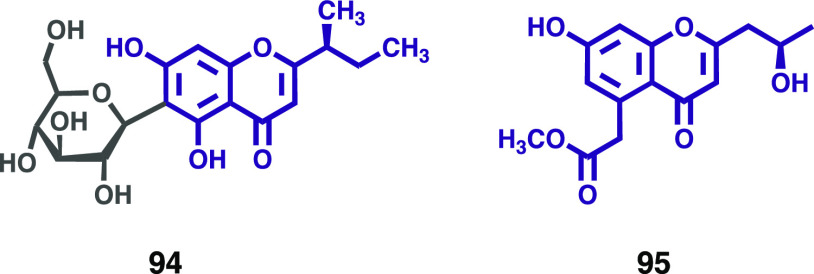

| (S)-(+)-5,7-Dihydroxy-2-(1-methylpropyl) chromone-6-β-d-glucoside (94) | Hypericum elodeoides | Moderate α-glycosidase inhibitory activity | (62) |

| (2′R)-7-Hydroxy-5-methyl acetate-2-(2′-hydroxypropyl) chromone (95) | Rumex dentatus | —a | (63) |

| Compound | Natural source | Biological activity | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fungi | |||

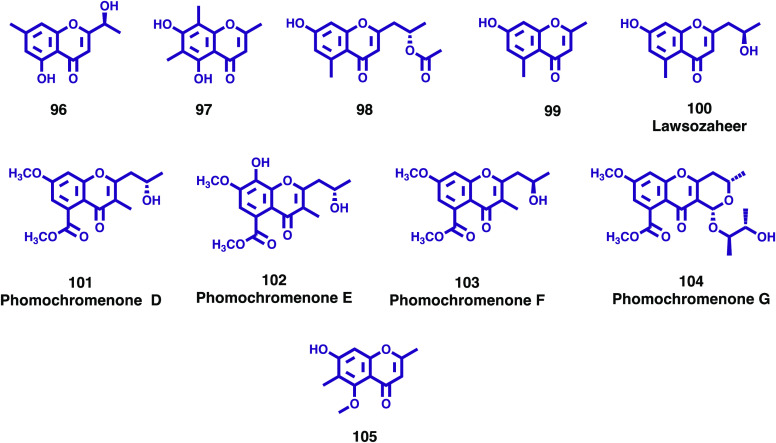

| (S)-5-Hydroxyl-2-(1-hydroxyethyl)-7-methylchromone (96) | Bipolaris eleusines | Weak antibacterial activity against S. aureus | (65) |

| (2′S)-2-(2-Acetoxypropyl)-7-hydroxy-5-methylchromone (98) | Alternaria brassicae (JS959) | Inhibition of cupric cation-induced LDL and HDL oxidation | (66) |

| 7-Hydroxy-2,5-dimethyl-4H-chromen-4-one (99) | |||

| 2-(2′R-Hydroxypropyl)-5-methyl-7-hydroxychromone (lawsozaheer, 100) | Paecilomyces variotii | Antibacterial activity against S. aureus | (67) |

| Phomochromenone D (101) | Phomopsis asparagi (DHS-48) | —a | (69) |

| Phomochromenone E (102) | |||

| Phomochromenone F (103) | |||

| Phomochromenone G (104) | |||

| 2,6-Dimethyl-5-methoxyl-7-hydroxylchromone (105) | Xylomelasma sp. (Samif07) | Antibacterial activity against E. carotovora | (70) |

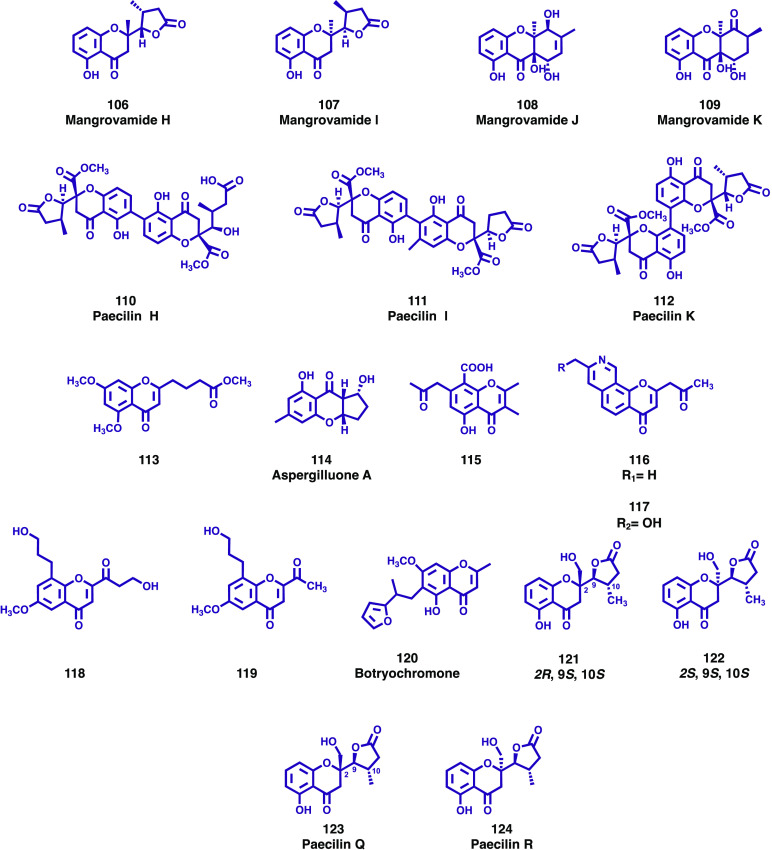

| Mangrovamide H (106) | Penicillium sp. (SCSIO041218) | —a | (71) |

| Mangrovamide I (107) | |||

| Mangrovamide J (108) | |||

| Mangrovamide K (109) | |||

| Paecilin F (110) | Penicillium oxalicum | —a | (72) |

| Paecilin G (111) | |||

| Paecilin H (112) | |||

| 4-(5,7-Dimethoxy-4-oxo-4H-chromen-2-yl)butanoic acid methyl ester (113) | Penicillium sclerotiorum | Antibacterial activity against carbapenems-resistant P. aeruginosa | (73) |

| Aspergilluone A (114) | Aspergillus sp. | Antibacterial activity | (74) |

| 5-Hydroxy-2,3-dimethyl-4-oxo-7-(2-oxopropyl)-4H-chromene-8-carboxylic acid (115) | Aspergillus sp. | Inhibition of NO production | (75) |

| Compound | Natural source | Biological activity | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fungi | |||

| 8-Methyl-2-(2-oxopropyl)-4H-pyrano[3,2-h]isoquinolin-4-one (116) | Aspergillus lentulus | Anti-TMV activity | (76) |

| 8-(Hydroxymethyl)-2-(2-oxopropyl)-4H-pyrano[3,2-h]isoquinolin-4-one (117) | |||

| 8-(3-Hydroxypropyl)-2-(3-hydroxy-1-oxopropyl)-6-methoxy-4H-chromen-4-one (118) | Aspergillus versicolor | Anti-TMV activity | (77) |

| 2-Acetyl-8-(3-hydroxypropyl)-6-methoxy-4H-chromen-4-one (119) | |||

| Botryochromone (120) | BCC 54265 | Weak cytotoxicity against KB and NCI-H187 cell-lines | (78) |

| Mycochromone A (121) | Mycosphaerella sp. | —a | (79) |

| Mycochromone B (122) | |||

| Paecilin Q (123) | Pseudofusicoccum stromaticum | Moderate antifungal activity against P. citricarpa | (80) |

| Paecilin R (124) | |||

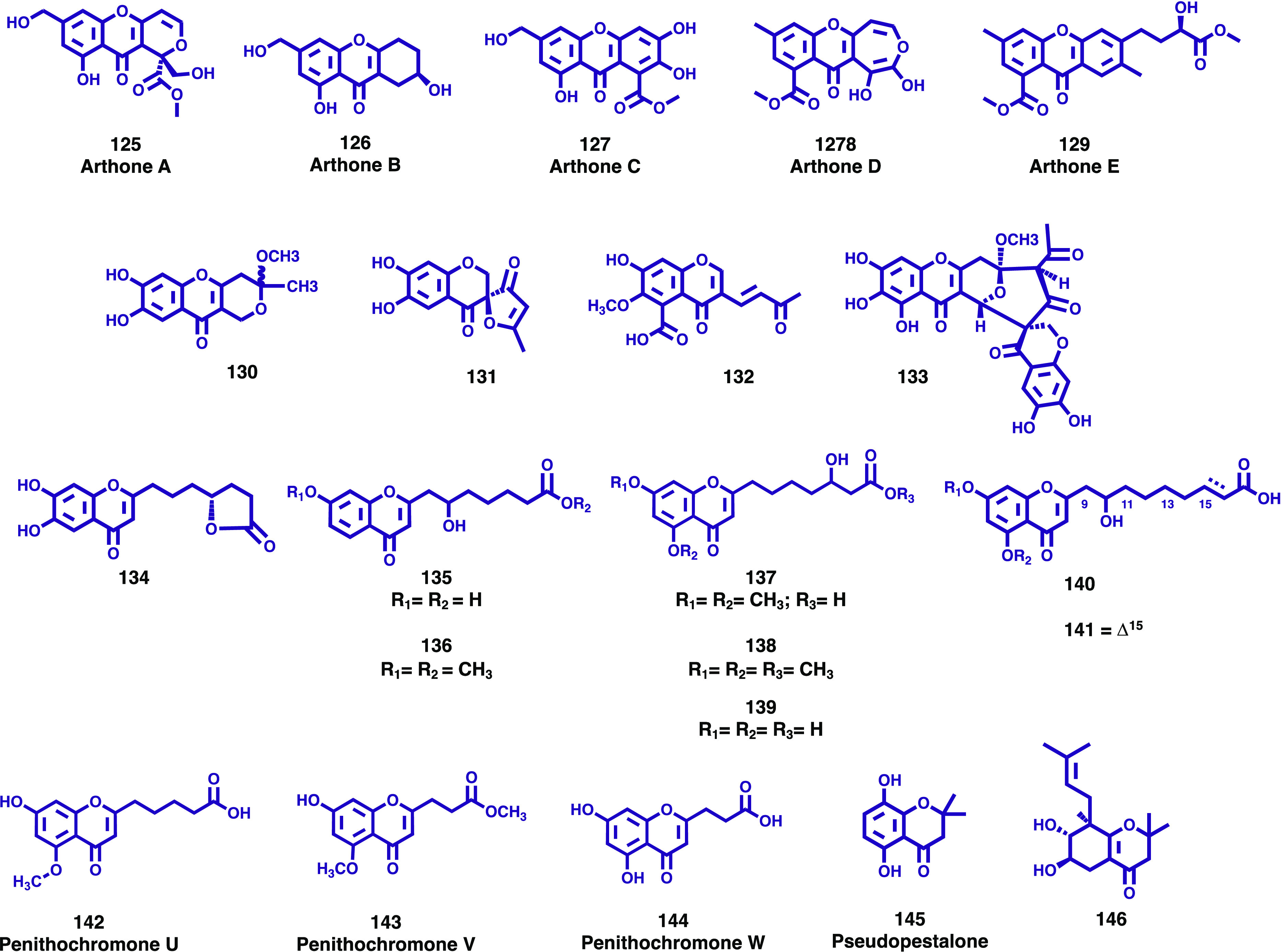

| Arthone A (125) | Arthrinium sp. | Antioxidant activity | (82) |

| Arthone B (126) | |||

| Arthone C (127) | |||

| Arthone D (128) | |||

| Arthone E (129) |

| Compound | Natural source | Biological activity | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fungi | |||

| Pyanochromone (130) | Penicillium erubescens | —a | (83) |

| Spirofuranochromone (131) | |||

| 7-Hydroxy-6-methoxy-4-oxo-3-[(1E)-3-oxobut-1-en-1-yl]-4H-chromene-5-carboxylic acid (132) | |||

| Erubescenschromone B (133) | |||

| Penithochromone M (134) | Penicillium thomii | α-glycosidase inhibition; weak antioxidant activity | (84) |

| Penithochromone N (135) | |||

| Penithochromone O (136) | |||

| Penithochromone P (137) | |||

| Penithochromone Q (138) | |||

| Penithochromone R (139) | |||

| Penithochromone S (140) | |||

| Penithochromone T (141) | |||

| Penithochromone U (142) | Penicillium thomii | —a | (85) |

| Penithochromone V (143) | |||

| Penithochromone W (144) | |||

| Pseudopestalone (145) | Pseudopestalotiopsis sp. | —a | (86) |

| 2,3-Dihydro-5,8-dihydroxy-2,2-dimethylchromen-4-one (146) |

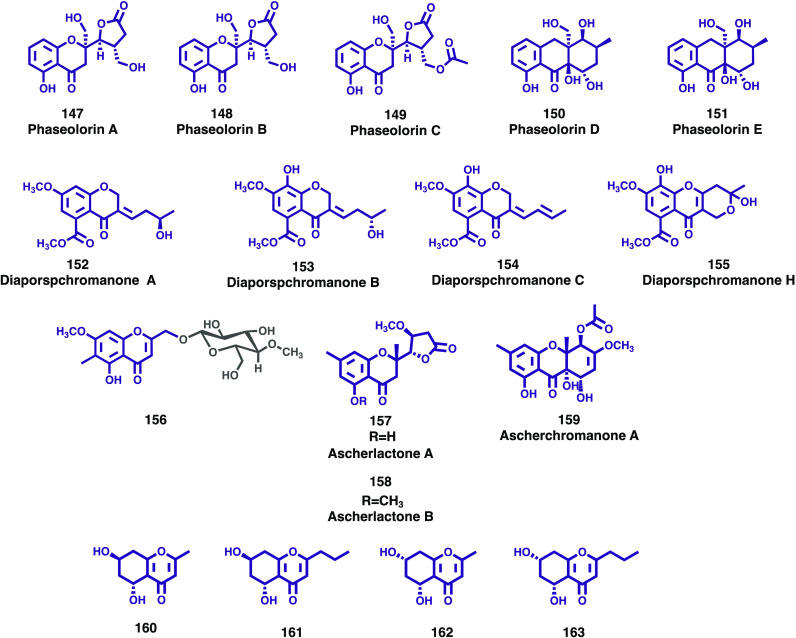

| Compound | Natural source | Biological activity | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fungi | |||

| Phaseolorin A (147) | Diaporthe phaseolorum | —a | (87) |

| Phaseolorin B (148) | |||

| Phaseolorin C (149) | |||

| Phaseolorin D (150) | |||

| Phaseolorin E (151) | |||

| Diaporspchromanone A (152) | Diaporthe sp. | Inhibition of NO production | (88) |

| Diaporspchromanone B (153) | |||

| Diaporspchromanone C (154) | |||

| Diaporspchromanone H (155) | |||

| 9-Hydroxyeugenetin 9-O-β-D-(4-O-methyl) glucopyranoside (156) | Akanthomyces sp | —a | (89) |

| Ascherlactone A (157) | Aschersonia confluens | —a | (90) |

| Ascherlactone B (158) | |||

| Ascherchromanone A (159) | |||

| (5R,7R)-5,7-Dihydroxy-2-methyl-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-4H-chromen-4-one (160) | Daldinia sp. | Anti-influenza A virus | (92) |

| (5R,7R)-5,7-Dihydroxy-2-propyl-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-4H-chromen-4-one (161) |

No biological activity reported.

Plants

Agarwood, a nontimber resinous wood obtained from the wounded tree of the Aquilaria and Gyrinops species of the Thymelaeceae family, is widely used in perfumes, incenses, and in traditional medicine for the treatment of inflammatory related diseases, as well as a stimulant, sedative, and cardioprotective agents.20,21 There are 31 species of Aquilaria found worldwide, among which 19 species can produce agarwood after being attacked by physical force, insects, or bacteria/fungi infection.22 Phytochemical studies on the agarwood revealed that 2-(2-phenylethyl)chromone derivatives are one of the two major components.23

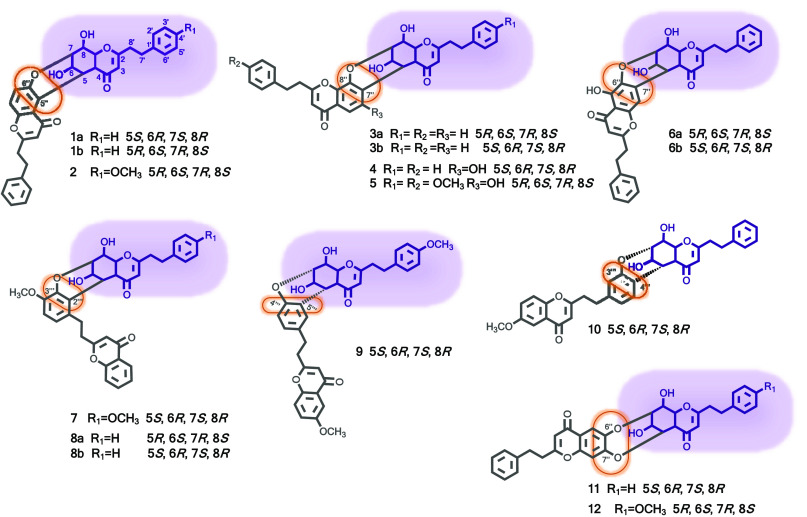

In a continuing search for anti-inflammatory agents from Aquilaria plants, Huo and colleagues isolated 16 new 2-(2-phenylethyl)chromone dimers, including four pairs of enantiomers along with eight optically pure analogues (1–12, Figure 2), from the resinous wood of Aquilaria sinensis.24 Their structures were determined by extensive spectroscopic analysis (1D and 2D NMR, UV, IR, and HRMS) and electronic circular dichroism (ECD) data. Compounds 1–10 are novel 2-(2-phenylethyl)chromone dimers featuring an unusual 3,4-dihydro-2H-pyran ring linkage connecting two 2-(2-phenylethyl)chromone monomeric units, while compounds 11 and 12 possess an unprecedented 6,7-dihydro-5H-1,4-dioxepine structural moiety in their structures. A putative biosynthetic pathway of the representative structures via a diepoxy derivative of a chromone with a nonoxygenated A-ring was proposed. Compounds 1a/1b, 2, 3a/3b, 5, 7, 8a/8b, and 10–12 were evaluated for their inhibitory effects on nitric oxide (NO) production in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated RAW264.7 cells. All these compounds showed inhibition against NO production with half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values in the range of 7.0–12.0 μM, using GYF-17, a 2-(2-phenethyl)chromone derivative, as a positive control (IC50 4.4 μM). None of the compounds showed cytotoxicity (up to 80 μM) with LPS treatment for 24 h.24

Figure 2.

2-(2-Phenylethyl)chromone derivatives (1–12) isolated from the resinous wood of Aquilaria sinensis.

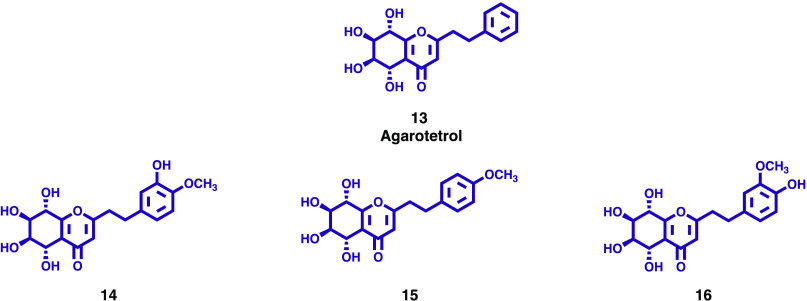

As a follow-up to a study carried out earlier, Sugiyama and co-workers investigated the methanol extract of agarwood. Further fractionation of the extract led to the isolation of three new 2-(2-phenylethyl)-5,6,7,8-tetrahydroxy-5,6,7,8-tetrahydrochromones (14–16, Figure 3) together with 18 known compounds. The new compounds have stereochemistry enantiomeric to agarotetrol (13, Figure 3). The assignment of the absolute configurations of the new compounds was determined by the exciton chirality method. All isolated compounds were tested for their phosphodiesterase (PDE) 3A inhibitory activity by a fluorescence polarization method. Out of the three chromones isolated for the first time, only 16 showed moderate PDE 3A inhibitory activity (IC50 40.1 μM).25

Figure 3.

2-(2-Phenylethyl)-5,6,7,8-tetrahydroxy-5,6,7,8-tetrahydrochromones (14–16) isolated from agarwood.

As part of a long-term project to characterize the chemical constituents from agarwood, Yang and colleagues performed a phytochemical investigation on the ethyl ether extract of the agarwood of an Aquilaria plant. Six known 2-(2-phenylethyl)chromones (17–22, Figure 4) were isolated together with new and four known sesquiterpenoids.26 Their structures were elucidated via detailed spectroscopic analysis, X-ray diffraction, and comparison with the published data. 2-(2-Phenylethyl)chromones were assayed to evaluate their inhibitory activity toward the tyrosinase. Compounds 6,8-dihydroxy-2-[2-(4-methoxyphenyl)ethyl]chromone (20) and 6-hydroxy-7-methoxy-2-[2-(3-hydroxy-4-methoxyphenyl)ethyl]chromone (19) displayed potent inhibitory activity with IC50 values of 51.5 ± 0.6 and 89.0 ± 1.7 mM, respectively (positive control kojic acid, 46.1 ± 1.3 mM). Compound 21 also exhibited a weak inhibition effect 34.8 ± 1.4% at 100 mM, whereas compounds 17, 18, and 22 were inactive up to a concentration of 100 mM (inhibition rate <30%). To further gain insight into the binding mechanism of 2-(2-phenylethyl)chromones with tyrosinase, molecular docking simulations were also performed. Compound 20, the most active compound, has an affinity for the allosteric site of tyrosinase and showed to be a mixed type inhibitor.26

Figure 4.

2-(2-Phenylethyl)chromones (17–32) isolated of Aquilaria plant’s agarwood.

The diverse biological properties demonstrated by substances isolated from the agarwood of A. sinensis, encouraged Yang and co-workers to further explore the discovery of new biologically active components of agarwood.27 This effort led to the isolation of eight new 2-(2-phenylethyl)chromone, aquichromones A–E (23–27, Figure 4), including two pairs of enantiomers [(±)-aquichromones A (23) and (±)-aquichromones B (24)], and 8-epi-aquichromone C (28, Figure 4). The structural identification and absolute stereochemistry of these natural products were elucidated by using spectroscopic and computational methods. The anti-inflammatory activity of the eight new 2-(2-phenylethyl)chromone derivatives was evaluated in an LPS-induced inflammatory model. The analysis of NO production revealed that compound 26 significantly inhibited LPS-induced nitrite oxide production. Western blot assay, performed to evaluate the anti-inflammatory activity of the compounds, showed that compounds 26 and 28 demonstrated significant anti-inflammatory activity, and their efficacy increased in a dose-dependent manner. The antirenal fibrosis activity of these compounds was also investigated by measuring the expression of several proteins including collagen I, fibronectin, and α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA). The results showed that none of the compounds exhibited antirenal fibrosis activity.

Following their continued research of bioactive constituents of agarwood, Yang et al. isolated four new 2-(2-phenethyl)chromone dimers, aquifilarones A–D (29–32, Figure 4), from ethyl acetate (EtOAc) extract of agarwood originating from Aquilaria filaria from the Philippines.28 The structures of the dimers were elucidated by spectroscopic analysis (1D and 2D NMR, and HR-ESI-MS). The compounds were screened in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells, and their effect on NO production was evaluated. Compounds 29–32 exhibited different levels of inhibition of NO production with IC50 values of 46.69 ± 3.43 μM, 45.36 ± 3.89 μM, 57.53 ± 6.55 μM, and 33.94 ± 3.99 μM, respectively. Quercetin was used as a positive control with the IC50 value of 12.46 μM. None of these compounds showed cytotoxicity at concentrations of IC50 values.

As part of an ongoing phytochemical study on the artificial holing agarwood originated from Aquilaria sinensis, Li and co-workers isolated two new 2-(2-phenylethyl)chromone dimers (33 and 34, Figure 5), and one new monomer (35, Figure 5), as well as two known analogues, which were first described from artificial agarwood.29 Compound structures were unambiguously elucidated based on 1D and 2D NMR spectroscopy, as well as by comparison with the literature data. The absolute configuration was determined by ECD calculation. According to the authors, compound 33 was the first structure found with C8–O–C4′′′ linkage among 2-(2-phenylethyl)chromone dimers. All compounds were evaluated for their acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitory activity; however, none of them presented inhibitory activity at 50 μg/mL.29

Figure 5.

2-(2-Phenylethyl)chromones (33–35) isolated from Aquilaria sinensis artificial holing agarwood.

As a follow-up to the phytochemical research carried out within the agarwood from Aquilaria crassna Pierre ex Lecomte, Zhao, and colleagues reported the isolation and identification of three new 5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-2-(2-phenylethyl)chromone derivatives (36–38, Figure 6) and one new dimeric 2-(2-phenylethyl)chromone (39, Figure 6).30 The structures were elucidated by spectroscopic methods. The configurations were determined via ROESY correlations, 3JH–H coupling constants analyses, comparisons of chemical shifts and specific rotations with known compounds, and ECD calculation in the case of 35. Compounds were evaluated for their cytotoxicity against five human cancer cell lines, including human myeloid leukemia cell line (K562), human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line (BEL-7402), human gastric cell line (SGC-7901), human lung cancer lines (A549), and human cervical carcinoma cell line (HeLa). Compounds 36 and 37 exhibited weak cytotoxicity toward HeLa cell line (IC50: 49.8 ± 1.2 μM) and K562 cell line (IC50: 42.66 ± 0.47 μM), respectively. Doxorubicin was used as positive control with IC50 values of 0.07–0.47 μM.

Figure 6.

2-(2-Phenylethyl)chromones (36–39) isolated from Aquilaria crassna agarwood.

Previous findings led Chen et al. to investigate the agarwood of Aquilaria walla. Two rare flavonoid-2-(2-phenylethyl)chromones (40 and 41, Figure 7) and five new dimeric 2-(2-phenylethyl)chromones (42–46, Figure 7) were isolated from ethanol extract by the LC–MS-guided fractionation procedure.31 Their structures were established based on extensive spectroscopic methods including HR-ESI-MS and 1D and 2D NMR. Compounds 40–42 were tested for cytotoxicity against five human cancer cell lines, K562, SGC-7901, HeLa, A-549, and BEL-7402. Only compound 40 exhibited cytotoxicity with IC50 values ranging from 13.40 to 28.96 μM, with cisplatin as the positive control. Compounds 41 and 42, at the same concentrations, did not show any cytotoxicity against the tested cell lines. From the results, the authors speculated that the configuration of the chiral centers at 2-(2-phenylethyl)chromone moiety has an important influence on cytotoxic activity.

Figure 7.

2-(2-Phenylethyl)chromones (40–46) from Aquilaria walla agarwood.

Myrtus communis, an evergreen sclerophyll shrub or small tree belonging to the Myrtaceae family, which comprises ca. 145 genera and over 5500 species, has been used since ancient times as a spice, as well as for medicinal and food preparation purposes.32 These plants have attracted the interest of researchers since they are recognized as a rich source of phloroglucinol derivatives with diverse chemical structures and intriguing biological activities.33

During the search for structurally unique phloroglucinol derivatives from plants, Tanaka and co-workers investigated the leaves of M. communis, leading to the isolation and structure elucidation of seven new phloroglucinol derivatives, and one new chromone glucoside, undulatoside A 6′-O-gallate (47, Figure 8), together with six known compounds.33 These compounds were evaluated for their antimicrobial activities against Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA and MSSA), and Bacillus subtilis strains. The isolated chromone glucoside, 47, did not exhibit antimicrobial activity against the strains tested.33

Figure 8.

New chromones isolated from the Myrtaceae (47 and 48) family and a new chromanone isolated from Nyctaginaceae (49) family.

The genus Syzygium belongs to the myrtle family, Myrtaceae, and comprises 1200–1800 species spread out over the world. Many species of the genus Syzygium are known for their traditional use for the treatment of various diseases.34 In continuation of the screening program to search for anti-inflammatory compounds from these plants, Ninh et al. isolated a new isopropyl chromone from the leaves of Syzygium cerasiforme (Blume) Merr. and L.M. Perry, a plant used in Vietnam in folk medicine.35 Its structure was elucidated as 5,7-dihydroxy-2-isopropyl-6,8-dimethyl-4H-chromen-4-one (48, Figure 8) by the analysis of HR-ESI-MS, NMR, and ECD spectral data. The anti-inflammatory activity of this new chromone was evaluated, and it was concluded that it inhibits NO production in LPS-activated RAW264.7 cells with an IC50 value of 12.28 ± 1.15 μM, compared to a positive control, NG-monomethyl-l-arginine acetate, which presents an IC50 value of 32.50 ± 1.00 μM.35

Abronia nana (Nyctaginaceae) is an ornamental plant that inhabits the desert area of North America whose pharmacological potential is not yet well-established. Following on from previous studies, carried out to find antisepsis lead compounds from natural sources, Lee and colleagues isolated a new C-methylcoumarinochromone from Abronia nana suspension cultures. Its structure was identified as 9,11-dihydroxy-10-methylcoumarinochromone (boeravinone Y, 49, Figure 8) by spectroscopic data analysis and verified by chemical synthesis.36 The potential inhibitory effect of 49 against high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1)-mediated septic responses was investigated. Results showed that 49 effectively inhibited lipopolysaccharide-induced release of HMGB1 and suppressed HMGB1-mediated septic responses, in terms of reduction of hyperpermeability, leukocyte adhesion and migration, and cell adhesion molecule expression. In addition, compound 49 increased the phagocytic activity of macrophages and exhibited bacterial clearance effects in the peritoneal fluid and blood of mice with cecal ligation and puncture-induced sepsis. On the basis of the results, the authors suggested that chromone 49 might be a potential therapeutic agent for the treatment of severe vascular inflammatory diseases, such as sepsis and septic shock.36

Aloe is a tropical or subtropical drought-resistant succulent plant widely known and used for centuries in folk medicine as a topical and oral therapeutic agent. So far, more than 350 aloe species have been identified, yet Aloe vera (Aloe barbadensis Mill./Aloe vera Linn.) is the most common variety.37 Aloe contains a huge amount of bioactive compounds, such as flavonoids, terpenoids, lectins, fatty acids, and anthraquinones. The high content of active substances has made this plant an important resource for the discovery of effective and safe natural additives for use in human welfare.

To evaluate and understand the antilipid peroxidation potential of fractions and pure metabolites from economically and ecologically important resinous medicinal plants of Oman, Rehman, and co-workers studied the resin of Aloe vera.38 The bioguided isolation of bioactive fractions from the resin afforded 17 chemical constituents, including three chromone derivatives identified as 6′-O-coumaroylaloesin (50, Figure 9), aloeveraside A (51, Figure 9), and aloeveraside B (52, Figure 9). Isolated fractions and compounds were screened to assess the antilipid peroxidation potential using a modified method of thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS). Compounds 50–52 showed promising antilipid peroxidation activity, still lower than that of butyl hydroxy toluene (BHT, positive control).38 According to the authors, the promising lipid peroxidation inhibitory activity exhibited by the compounds isolated from A. vera may substantiate its use in traditional medicine. Among the isolated chromone derivatives, compound 52 showed the highest activity, which was correlated with the presence of one extra −OH group attached to the benzene ring.38

Figure 9.

New chromones (50–54) isolated from the genus Aloe.

Aloe monticola Reynolds is one of the endemic species of the genus Aloe found in Ethiopia and is traditionally used for the treatment of infectious diseases. In their ongoing search for antimicrobial compounds, Hiruy and colleagues investigated the antimicrobial activities of the leaf latex of A. monticola and two isolated constituents, aloesin (53, Figure 9) and 7-O-methyl-6′-O-coumaroylaloesin (54, Figure 9), against 21 bacterial and 4 fungal strains.39 In accordance with the authors, this was the first report on the occurrence of 54 in plants. Both chromones displayed antibacterial and antifungal effects against most of the bacterial and fungal strains tested, but their action was more prominent against Salmonella typhi, Shigella dysentery, and Staphylococcus aureus with a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) value of 10 μg/mL. Acute toxicity tests on mice revealed that neither the latex nor the isolated compounds possess toxicity up to a dose of 2000 mg/kg. This study led the authors to conclude that the latex of A. monticola has genuine antimicrobial activity, attributed at least in part to the presence of the isolated chromones, 53 and 54, which confirms that a correlation exists between traditional usage and intrinsic antimicrobial activity.39

The Fabaceae or Leguminosae, commonly known as the legume, pea, or bean family, is a large, economically, and medicinally important family of flowering plants. There are almost 770 genera and more than 19,500 species in the family and a staggering amount of diversity therein.40 From a phytochemical point of view, these species produce secondary metabolites that can exert important effects on human health.41

Macrolobium latifolium Vogel (Leguminosae-Caesalpinioideae) is a deciduous tree of endemic occurrence in the Brazilian Atlantic forest. Although the genus Macrolobion Schreb. includes about 60 species of plants distributed exclusively in neotropical regions, there is not much data available on its chemical composition. Nascimento and co-workers reported the first phytochemical investigation of a Macrolobium species and its chemical composition and biological activity.42 Besides known compounds, a new unusual C-glycoside chromone (5,7-dihydroxychromone-3α-D-C-glucoside, named macrolobin, 55, Figure 10) was isolated from the EtOAc soluble fraction of leaves. Macrolobin (55) displayed antimicrobial activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Salmonella enterica (MIC values 0.73 and 0.44 μM, respectively) and exhibited significant AChE inhibitory activity (IC50 0.8 μM; positive control eserine 0.51 μM).42 In accordance with the authors, these findings indicate that M. latifolium can be looked as an interesting source to find new bioactive compounds.

Figure 10.

New chromones (55–65) isolated from the Leguminosae family.

Cassia, with approximately 500 species, is a large genus of the family Leguminosae.43 Scientific studies on Cassia species have suggested that these plants have enormous biological potential. They exhibit important pharmacological activities, namely anti-inflammatory, antitumor, and antimutagenic, and have also been used to treat skin wounds and infections, including eczema, scabies, and ringworm.43Cassia pumila Lam. is a diffuse terrestrial and stout annual herb widely distributed in southern China. Phytochemical investigations on this plant have shown the presence of diverse bioactive metabolites such as anthraquinones, chromones, flavones, and terpenes.43

Continuing their efforts to seek new bioactive metabolites from medicinal plants, Mi and colleagues isolated two new compounds (56 and 57, Figure 10), together with five known chromone derivatives, from the whole plant of Cassia pumila.44 Their structures were elucidated by spectroscopic methods, including extensive 1D and 2D NMR techniques. The new compounds were identified as 6-(hydroxymethyl)-2,2-dimethyl-8-(2-oxopropyl)chroman-4-one (56) and 2,2,6-trimethyl-8-(2-oxopropyl)chroman-4-one (57).44 By comparing the data obtained with the literature, it was possible to identify the other compounds as 5-methoxy-2,2-dimethyl-7-(2-oxopropyl)-2,3-dihydrochromen-4-one, 8-methyleugenitol, 7-hydroxy-2-methyl-5-(2-oxopropyl)-4H-chromen-4-one, 6-methoxy-3-methyl-8-(2-oxopropyl)benzo[b]oxepin-5(2H)-one, and fistulachromone A. The isolated compounds were evaluated for their antimethicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (anti-MRSA) activity using as a criterion the inhibition zone (mean diameter of inhibition in millimeters). The results revealed that the new compounds 56 and 57 show relevant antibacterial activity.44

Cassia auriculata Linn., a perennial subshrub-like herb plant of the Cassia genus, is extensively used in a variety of medicinal applications. Increasing evidence suggests that this plant species’ extracts and purified compounds can be used for the development of pharmaceuticals. A phytochemical reinvestigation on the C. auriculata was carried out by Jiang et al, leading to the isolation of two new chromone derivatives (58 and 59, Figure 10).45 Their structures were elucidated by spectroscopic methods, including extensive 1D and 2D NMR techniques and the systematic names given as 6-(2,2-dimethyl-2H-chromene)-2-isopropyl-8-hydroxy-4H-chromen-4-one and 6-(2,2-dimethyl-2H-chromene)-2,8-dimethyl-4H-chromen-4-one, respectively. The antimicrobial activity of compounds 58 and 59 was evaluated for their anti-MRSA activity using as criterion the diameter of the inhibition zone (IZD). In accordance with the authors, the results revealed that compounds 58 and 59 present good inhibition when compared to vancomycin, an antibiotic used as a positive control. In another study involving the same species, Liu and co-workers investigated the stem bark of C. auriculata and isolated two new chromones (60 and 61, Figure 10) along with four known ones.46 The new compounds were elucidated by means of spectroscopic methods, and their structure was established as 2-(2-(furan-2-yl)-2-oxoethyl)-6-methoxy-8-(2-oxopropyl)-chromone (60) and 2-(2-(furan-2-yl)-2-oxoethyl)-5-methoxy-8-(2-oxopropyl)-chromone (61). As the extract from C. auriculata, and certain chromones belonging to the genus Cassia exhibit potential antiviral activities, compounds 60 and 61 were evaluated for their antitobacco mosaic virus (TMV) and antirotavirus activities. The results showed that both compounds exhibited potential anti-TMV activity with inhibition rates of 28.2 and 30.5%, respectively, which are close to that of the positive control (ningnanmycin 32.4%). In addition, compounds 60 and 61 exhibited potential antirotavirus activity with therapeutic index (TI) values of 14.8 and 15.9, although they presented lower values than the positive control (TI ribavirin: 21.2).

As part of their ongoing research on biologically active secondary metabolites from the genus Cassia, Yang and colleagues reinvestigated the chemical constituents of the stem bark of C. alata. As a result, one new chromone, alatachromone A (62, Figure 10) and a new dimeric chromone-indole alkaloid, alataindolein D (63, Figure 10), were isolated and their structures were determined using HR-ESI-MS and extensive 1D and 2D NMR spectroscopic studies.47 Compounds 62 and 63 were tested for their anti-TMV and antirotavirus activities, and the results showed relevant anti-TMV activities with inhibition rates of 52.3%, and 31.8%, respectively (inhibition rate of the positive control ningnanmycin: 32.8%). Moreover, both compounds exhibited potential antirotavirus activities with TI values of 12.4 and 12.0 (positive control ribavirin: 21.2). More recently, these authors described the isolation of two new (64 and 65, Figure 10) and five already described chromones from the whole plants of C. rotundifolia. They were identified as 2-acetyl-5-isopropyl-7-methyl-4H-chromen-4-one (64) and 2-acetyl-7-(hydroxymethyl)-5-isopropyl-4H-chromen-4-one (65).48 In accordance with the authors, both compounds present good anti-MRSA activities (IZD of 13.2 ± 2.4 and 15.8 ± 2.6 mm, respectively) when compared to vancomycin, used as a positive control (IZD of 32 mm).

The Rutaceae is a highly diversified plant family comprising 150–162 genera and 1500–2096 species.49 Currently, only two subfamilies of Rutaceae are recognized, Rutoideae and Cneoroideae, the latter comprising only eight genera including Dictyoloma. The genus Dictyoloma contains only two species, D. peruvianum, which occurs in Peru and Bolivia, and D. vandellianum Adr. Juss., in Brazil. Phytochemical studies have already demonstrated the presence of quinolone alkaloids, limonoids, and pyranochromones in the leaves, roots, and bark of the Brazilian species. Given the pharmacological potential of the benzopyrone moiety, Opretzka and co-workers evaluated the potential anti-inflammatory activity of three chromones, 6-(3-methylbut-2-enyl) allopteroxylin methyl ether, 3,3-dimethylallylspatheliachromene methyl ether, and 5-O-methylcneorumchromone K, isolated from the root bark of Dictyoloma vandellianum.50 In accordance with the authors, 5-O-methylcneorumchromone K (66, Figure 11) exhibited relevant antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects, probably due to glucocorticoid receptor (GR) activation and inhibition of the nuclear transcription factor-κB (NF-κB) pathway. The gathered results demonstrated the pharmacological potential of natural chromones, highlighting 5-O-methylcneorumchromone K (66) as a possible lead candidate for the drug discovery process for the development of new anti-inflammatory drugs.50

Figure 11.

New chromones and chromanones (66–76) isolated from Rutaceae, Calophyllaceae, and Menispermaceae plant families.

Calophyllum spp. (Calophyllaceae) is a genus of tropical trees valued as an important source of biogenetically related compounds that have relevant pharmacological activities. It consists of nearly 187 species; 179 thrive in the Old World and are distributed mainly in the Indo-Malaysian region, and the most important one is C. inophyllum.51 Over the past few years, several research groups have been dedicated to the study of these species. Several chromanone derivatives were isolated from the root and resin of C. inophyllum. The structures of the isolated compounds (67–71, Figure 11) were elucidated by spectroscopic methods as caloinophyllin A (67),52 calophinophyllins A and B (68 and 69),53 inocalophylline C (70),54 and calophylloidic acid B (71).55 Among these new compounds, only the last one showed significant biological activity, exhibiting potent antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli with MIC values of 16 and 8 μg/mL, respectively. Gerometta et al. reported the isolation, structure characterization, and in vitro cytotoxic activity of a new chromanone, isocaloteysmannic acid (72, Figure 11), from the leaf extract of the medicinal species C. tacamahaca Willd.56 Compound 72 showed a moderate cytotoxicity against human liver cancer (HepG2) and human colon and colorectal adenocarcinoma (HT29) cell lines, with IC50 values of 19.65 and 25.68 μg/mL, respectively. Tjahjandarie and colleagues isolated and established the structures of two new chromanones, calopeekelioic acids A (73) and B (74), from the stem bark of C. peekelii Lauterb.57 These new compounds were evaluated for their antiplasmodial activity against the Plasmodium falciparum strain 3D7 and showed relevant activity with an IC50 value of 1.70 and 1.01 mg/mL, respectively (positive control chloroquine: 1.03 mg/mL).

Limacia scandens Lour. belongs to the family Menispermaceae and is distributed sporadically in lowland forests and swamps in many regions of Southeast Asia. Although the stems and roots of L. scandens are known for their therapeutic activity, there are not many studies on their chemical constituents. While screening senotherapeutics from natural products, Lee et al. isolated two undescribed chromone derivatives from the stems of L. scandens. The structures of compounds were elucidated through spectroscopic data analysis, including 1D and 2D NMR, HR-ESI-MS, and ECD data and were determined to be 2-{2-[(3′-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl)phenyl]ethyl}chromone (75, Figure 11) and 3-methoxy-2-{2-[(3′-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl)phenyl]ethyl}chromone (76, Figure 11).58 Both compounds were tested in replicative senescent human dermal fibroblasts (HDFs) to evaluate their potential as senotherapeutic agents to specifically target senescent cells. According to the authors, the two chromone derivatives have senolytic activity, and in particular, compound 75 showed the potential to inhibit senescence-associated β-galactosidase and expressing senescence-associated secretory phenotype factors.

Apiaceae Lindl. (=Umbelliferae Juss.) is one of the most numerous plant families and includes several vegetables and herbs of high economic and medicinal value.59 In addition to their popularity and high commercial relevance, umbelliferous crops are important sources of bioactive compounds.

Cnidium monnieri (L.) Cusson is an herb of the Umbelliferae species whose fruits are used as a traditional Chinese medicine for the treatment of a variety of diseases. Following previous research carried out with this species, Huang and co-workers isolated two new chromones, named cnidimol G (77, Figure 12 and cnidimol H (78, Figure 12), from the methanol extract of the fruit of Cnidium monnieri (L.) Cusson.60 The structures of compounds were elucidated using several spectroscopic techniques and the anti-inflammatory activity was tested in vitro. The results found showed that compound 76 inhibits NO production in LPS-activated RAW264.7 cells with an IC50 value of 198.7 μM (positive control indomethacin: IC50 = 130.8 μM).

Figure 12.

New chromones (77–93) isolated from Umbelliferae plant family.

Saposhnikovia divaricata (Turcz.) Schischk., a perennial herb belonging to the family Umbelliferae, is widely distributed in Northeast Asia. Its dried root is used as a Chinese herbal medicine. During their continuous research for finding chromones with interesting biological activities, and considering the medicinal potential of the Saposhnikovia divaricata, Sun and colleagues isolated 15 new chromones, sadivamones A–E (79–83), cimifugin monoacetate (84), sadivamones F–N (85–93) (Figure 12), from the EtOAc portions of 70% ethanol extract of S. divaricata (Turcz.) Schischk roots.61 The structures were determined using 1D/2D NMR data and ECD calculations. A LPS-induced RAW264.7 inflammatory cell model was used to determine the potential anti-inflammatory activity of all the isolated compounds. The results showed that compounds 80, 86, 90, and 91 significantly inhibited the production of LPS-induced NO in macrophages. To determine the signaling pathways involved in the suppression of NO production by compounds 85, 90, and 91, extracellular regulated (ERK) and c-Jun N-terminal (JNK) protein kinases expression was investigated by Western blot analysis. Compounds 90 and 91 inhibited the phosphorylation of ERK and the activation of ERK and JNK in RAW264.7 cells via mitogen activated protein kinases (MAPK) signaling pathways. In accordance with the authors, compounds 90 and 91 may be valuable drug candidates for the treatment of inflammatory diseases.

Hypericum elodeoides Choisy (Hypericaceae) is a perennial herbaceous plant used as a traditional Chinese medicine to address several health problems. During their studies to understand the main and active ingredients of H. elodeoides, Mu and colleagues isolated a new chromone C-glucoside and five known chromones.62 The structure was characterized by a comprehensive analysis of its spectroscopic data and was determined to be (S)-(+)-5,7-dihydroxy-2-(1-methylpropyl) chromone-6-β-d-glucoside (94, Figure 13). The new chromone showed moderate α-glycosidase inhibitory activity with an IC50 value of 456.26 ± 1.17 μM (positive control acarbose: 355.73 ± 1.19 μM).

Figure 13.

New chromones (94 and 95) isolated from Hypericaceae and Polygonaceae plant families.

Rumex L., a large genus of Polygonaceae, is comprising about 200 species distributing widely around the world. Rumex species have had a valued place in folk medicine, being used to treat a variety of diseases. As a part of their continuing study on bioactive components from Rumex plants, Li et al. have isolated a new chromone from the roots of R. dentatus. Its structure was determined using extensive spectroscopic analysis and was assigned as (2′R)-7-hydroxy-5-methyl acetate-2-(2′-hydroxypropyl) chromone (95, Figure 13).63 No antifungal activity against Epidermophyton floccosum was observed for the new chromone.

Fungi

The kingdom Fungi is an incredibly rich and unexploited source of bioactive natural products that could substantially contribute to obtain unique chemical compounds with relevant biological properties against several diseases. Fungi produce a vast variety of secondary metabolites such as terpenes, alkaloids, polyketides, and sugars which can play a very important role in drug discovery and development programs in the pharmaceutical industry.

Endophytic fungus is one of the most important fungal resources for obtaining high-value bioactive compounds with huge applications in diverse fields of biotechnology. They produce a range of metabolites of different chemical classes some of which possess interesting pharmacological activities, including antimicrobial, antioxidant, antidiabetic, antimalarial, and anticancer properties. The discovery of novel and structurally diverse active compounds provides a valuable resource for studying natural medical products from the microbiome.64

Following the ongoing study on the chemical constituents of the fermentation broth of an endophytic fungus, Bipolaris eleusines, isolated from potato, He at al. reported the isolation of one undescribed chromone, (S)-5-hydroxyl-2-(1-hydroxyethyl)-7-methylchromone (96, Figure 14), and one known analog identified as 5,7-dihydroxyl-2,6,8-trimethylchromone (97, Figure 14).65 Their structures were established based on extensive spectroscopic methods, and compounds were tested for their potential against two bacterial strains, Staphylococcus aureus subsp. aureus ATCC29213 and Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica ATCC14028. Compounds 96 and 97 showed weak inhibitory activities against S. aureus with inhibition rates of 56.3 ± 0.48 and 32 ± 1.27%, respectively, at the concentration of 128 μg/mL (positive control Penicillin G: 99.9 ± 0.013% at 5 μg/mL).65

Figure 14.

New chromones (96–105) isolated from endophytic fungi.

In continuation of the chemical investigation of the ethyl acetate extract of an endophytic fungus, Alternaria brassicae JS959 derived from a halophyte, Vitex rotundifolia, Kim and co-workers isolated a new chromone, (2′S)-2-(2-acetoxypropyl)-7-hydroxy-5-methylchromone (98; Figure 14), along with 16 known compounds including a chromone derivative (99; Figure 14), identified as 7-hydroxy-2,5-dimethyl-4H-chromen-4-one, reported for the first time from this endophytic fungus.66 The isolated chromones (98 and 99) were investigated for their inhibitory effects on cupric-ion-induced lipoprotein oxidation in human blood plasma. Both chromones significantly reduced the conjugated diene formation and increased the lag time on cupric cation-induced low density lipoprotein (LDL) and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) oxidation in human plasma. Compound 99 showed stronger inhibitory activity than the positive control, vitamin C. These results suggest that metabolites of endophytic microbes could provide an excellent basis for the discovery and development of new agents for heart disease.66

Abbas and colleagues reported the isolation of a new chromone, named as lawsozaheer (100; Figure 14), produced by an endophytic fungus Paecilomyces variotii isolated from Lawsonia Alba Lam., an ornamental hedge and dye plant used extensively by many civilizations and cultures for centuries.67 Structural elucidation identified the new compound as 2-(2′R-hydroxypropyl)-5-methyl-7-hydroxychromone (100). Antimicrobial activity of the broth extract and compound 100 was determined against 15 Gram-positive bacteria, including multidrug resistant strains, 12 Gram-negative bacteria, and 13 fungi.67 Compound 100 showed highly selective activity against Staphylococcus aureus (NCTC 6571) bacterium with 84.26% inhibition at 150 μg/mL, comparing well with the clinical drug ofloxacin (87.013% inhibition at 100 μg/mL). The IC90 determined using the microplate Alamar Blue assay was found to be 225 μg/mL. The activity of compound 100 against the other bacteria and fungi tested was marginal.

One fungal genus that has been especially productive regarding the presence of a diverse array of bioactive compounds is Phomopsis. Chemical investigation of this fungal genus has resulted in the discovery of a total of 246 bioactive compounds, over the period 2010–2019, for which diverse biological activities have been reported, such as cytotoxic, antifungal, antibacterial, antiviral, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, phytotoxic, antimalarial, antialgae, among others.68 As part of the ongoing investigation on bioactive metabolites from mangrove endophytic fungi, Wei et al. reported the isolation of Phomopsis asparagi DHS-48 from a fresh root of the mangrove plant Rhizophora mangle.69 Four new chromones, phomochromenones D–G (101–104; Figure 14), along with four known analogs were isolated from the EtOAc extract of P. asparagi, after fermentation on a solid rice medium containing sea salt, and their structures were elucidated based on a thorough spectroscopic analysis. The isolated compounds were evaluated in vitro for immunosuppressive activity against the proliferation of concanavalin A (ConA)-induced T and LPS-induced B murine splenic lymphocyte using CCK-8 method.69 Cyclosporine A was used as a positive control. Although an immunosuppressive activity screening indicated that the crude extract of P. asparagi DHS-48 exhibited strong inhibitory activity against splenic lymphocyte growth, with IC50 of 6 μg/mL, no evident inhibitory effect was found for the newly isolated chromones (101–104).

In the course of searching bioactive substances from endophytic fungi, Lai and co-workers have isolated five chromone derivatives from the culture of the endophytic fungus Xylomelasma sp. Samif07, derived from the medicinal plant Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge.70 Among them, compound 105 (Figure 14), 2,6-dimethyl-5-methoxyl-7-hydroxylchromone, was isolated from a natural system for the first time, although this molecule had been synthesized previously.70 All the other compounds were reported from the genus Xylomelasma for the first time, and were identified as 6-hydroxymethyleugenin, 6-methoxymethyleugenin, chaetoquadrin D, and isoeugenitol. The isolated compounds were tested for their antibacterial activities against seven human/plant pathogenic bacteria including Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus hemolyticus, Agrobacterium tumefaciens, Erwinia carotovora, Ralstonia solanacearum, and Xanthomonas vesicatoria. Compound 105 showed inhibition against only one bacterium, E. carotovora (MIC, 100 μg/mL).

The Penicillium genus, composed of over 200 species, is one of the largest groups of fungi and is well-known for its ability to produce secondary metabolites with a diverse array of biological effects. In their search for novel biologically active secondary metabolites, Yang and colleagues isolated four new chromone derivatives (106–109, Figure 15), mangrovamide H–K, from the mangrove sediment-derived fungus Penicillium sp. SCSIO041218.71 The structures of new compounds were determined by analysis of the spectroscopic data, and their antiallergic bioactivity was measured using IgE-mediated rat mast RBL-2H3 cells. No significant activity was found for the new chromones. Gu et al. isolated three new chromanone dimer derivatives, paecilins F–H (110–112, Figure 15) from the mutant strains of Penicillium oxalicum 114-2.72 The structures were elucidated by extensive analysis of spectroscopic data, and these compounds were evaluated for antiviral, cytotoxic, and antibacterial activities. The new chromanone dimer derivatives showed no significant bioactivity. As a part of an ongoing search for novel antibacterial active metabolites, Liao and co-workers isolated a new chromone analog, 4-(5,7-dimethoxy-4-oxo-4H-chromen-2-yl)butanoic acid methyl ester (113, Figure 15), from the fungus Penicillium sclerotiorum MPT-250, obtained from the stems of Taxus wallichiana var. chinensis (Pilger) Florin.73 The structural elucidation was performed by high-resolution mass spectrometry and NMR spectroscopy, and the antibacterial activity was evaluated against eight clinically drug-resistance bacteria. The new chromone analog (113) displayed significant antibacterial activity against carbapenems-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa with a MIC value of 3.13 μg/mL.

Figure 15.

New chromones and chromanones (106–124) isolated from endophytic fungi.

Aspergillus spp. are filamentous fungi found ubiquitously in the environment and are considered important because they produce a wide range of structurally diverse secondary metabolites of great interest to the pharmaceutical industry. In the course of their investigation for the secondary metabolite of marine-derived fungus Aspergillus sp. LS57, Liu and colleagues isolated one new chromone named aspergilluone A (114, Figure 15) containing a chromone skeleton fused with an unusual hydrogenation cyclopentanoid ring.74 The structure was elucidated by 1D and 2D NMR and mass spectrometric analyses and the antimicrobial activity of 114 was evaluated against five human pathogenic microbes. The results showed that the new chromone displayed anti-Mycobacterium tuberculosis activity with MIC value of 32 μg/mL (rifampin MIC = 0,01 μg/mL), moderate inhibitory activity against Staphylococcus aureus with MIC value = 64 μg/mL (chloramphenicol MIC = 8 μg/mL), and feeble activity against Gram-positive Bacillus subtilis and Gram-negative pathogen Escherichia coli with the same MIC value of 128 μg/mL (chloramphenicol MICs of 4 and 2 μg/mL, respectively). As part of their continuing effort to discover bioactive metabolites, Liu et al. isolated a new chromone (115, Figure 15) from strain Aspergillus sp. ZJ-68 obtained from the fresh stem of mangrove plant Kandelia candel.75 The structure was elucidated by a combination of HR-ESI-MS and NMR spectroscopic analyses, and the compound was tested for its inhibitory activity against LPS-activated NO production in RAW264.7 cells. Chromone 115 displayed strong inhibitory effects on NO production with an IC50 value of 4.094 ± 0.8 μM (indomethacin IC50 = 35.8 ± 0.5 μM). Wu and co-workers also isolated two new chromone alkaloids (116 and 117, Figure 15) from fungi Aspergillus lentulus obtained from the leaves of cigar tobacco.76 The structures of the compounds were established by spectroscopic analysis, and the new chromones were tested for their anti-TMV activities. Compound 117 showed higher anti-TMV activity than the positive control, with an inhibition rate of 44.2% (ningnanmycin inhibition rate of 34.8%), while compound 116 also exhibited anti-TMV activities with an inhibition rate of 31.8%. The same research group has also isolated other new chromones, 8-(3-hydroxypropyl)-2-(3-hydroxy-1-oxopropyl)-6-methoxy-4H-chromen-4-one (118, Figure 15) and 2-acetyl-8-(3-hydroxypropyl)-6-methoxy-4H-chromen-4-one (119, Figure 15) from fungus Aspergillus versicolor obtained from tobacco.77 The new compounds exhibited anti-TMV activities with inhibition rates of 35.3 and 30.6%, respectively, with rates that are close to that of positive control (ningnanmycin).

As part of their search for novel bioactive compounds obtained from fungal sources, Isaka and colleagues isolated a new chromone derivative, botryochromone (120, Figure 15), from cultures of the fungus BCC 54265 of the family Botryosphaeriaceae.78 The structure was elucidated based on NMR, HRMS, and CD data and its antiplasmodial (P. falciparum K1), antimycobacterial (Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Ra), and antibacterial (Bacillus cereus and Enterococcus faecium) activity and cytotoxicity to cancer cell-lines (KB, MCF-7 and NCI-H187) was assessed. Botryochromone (120) was inactive in the biological assays and showed weak cytotoxicity against KB and NCI-H187 cell-lines with IC50 values of 43 and 18 μg/mL, respectively.

In continuation of the research work carried out over the past two decades focused on the exploration of new bioactive metabolites, Tan et al. isolated two new chromone derivatives (121 and 122, Figure 15), from the mangrove endophytic fungus Mycosphaerella sp. L3A1.79 Their structures were elucidated through HR-ESI-MS analysis and spectroscopic data, and the cytotoxicity of the isolated compounds was evaluated against six human cancer cell lines (MDA-MB-435, MDA-MB-231, SNB19, HCT116, A549, and PC-3). Both compounds did not show significant cytotoxic activity against the cancer cell lines tested.

As part of their screening for natural products with antifungal potential, Iantas and co-workers have isolated two new chromanones, paecilins Q (123, Figure 15) and R (124, Figure 15) from the endophyte fungus Pseudofusicoccum stromaticum CMRP4328 obtained from the medicinal plant Stryphnodendron adstringens.80 The chemical structures of the new compounds were determined by HR-ESI-MS analysis and spectroscopic data, and their antifungal activity was assessed against an important citrus pathogen, Phyllosticta citricarpa, the causal agent of citrus black spot disease. At a concentration of 10 mg/mL, paecilin Q (123) had moderate antifungal activity inhibiting the mycelial growth of P. citricarpa by 48.6%. Compounds 123 and 124 decreased (50.5% and 35.5%, respectively) the pycnidia produced by P. citricarpa citrus in leaves, which is responsible for the disease dissemination in orchards. The cytotoxic activity of the new paecilins Q (123) and R (124) was evaluated using nonsmall cell lung (A549) and prostate (PC3) human cancer cell lines. Both compounds showed no cytotoxicity at concentrations up to 80 μM against these cell lines.

The marine environment hosts a wide variety of species which, due to their adaptation to this unique habitat, produce a wide variety of primary and secondary metabolites with significant biological activities. Among the marine microorganisms, fungi have gained an important role since they have proved to be a rich source of new biological natural products. Actually, over the last years, the chemical study of marine fungi has led to the discovery of numerous bioactive compounds, contributing prominently to enrich the natural products chemical library.81

The genus Arthrinium comprises an environmentally and biochemically diverse group of ascomycetous fungi reported as endophytes, plant pathogens, and saprobes and are commonly isolated from various terrestrial environments. Although several species have already been isolated from marine environments, with an interesting biological activity, marine Arthrinium species remain poorly understood. During their search for new antibiotics from marine resources, Bao et al. studied an Arthrinium sp. UJNMF0008 from deep-sea sediment because of its relevant inhibitory activity against Staphylococcus aureus.82 Investigation on this species led to the isolation and characterization of five new chromone derivatives, arthones A–E (125–129, Figure 16), together with eight known biogenetically related cometabolites.82 To evaluate their biological properties, the antioxidant activity was assayed by DPPH and ABTS radical scavenging methods using curcumin as the positive control (IC50 = 24.3 and 9.5 μM, respectively). Compound 126 exhibited significant antioxidant activity, with IC50 values of 16.9 μM and 18.7 μM for DPPH and ABTS assays, respectively, while the others showed no significant effect at 50.0 μM. The antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive bacterial strains Mycobacterium smegmatis ATCC 607 and Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923, Gram-negative Escherichia coli ATCC 8739, Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 9027, and fungus Candida albicans ATCC10231, as well as anti-inflammatory activity based on the inhibition effect of NO production in LPS-induced mouse macrophages RAW 264.7 cells were evaluated. However, none of the compounds displayed significant bioactivity in the antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory assays performed up to a 50.0 μM concentration.82

Figure 16.

New chromones and chromanones (125–146) isolated from endophytic marine fungi.

In their ongoing search for antibiotics from marine-derived fungi from the tropical sea, Kumla and colleagues investigated secondary metabolites from cultures of Penicillium erubescens KUFA 0220, which was isolated from the marine sponge Neopetrosia sp., collected from the coral reef at Samaesan Island, Chonburi province, in the Gulf of Thailand.83 Chromatographic fractionation and purification of the crude EtOAc extract of the cultures of P. erubescens KUFA 0220 provided four novel chromone derivatives, including a pyanochromone (130, Figure 16), a spirofuranochromone (131, Figure 16), 7-hydroxy-6-methoxy-4-oxo-3-[(1E)-3-oxobut-1-en-1-yl]-4H-chromene-5-carboxylic acid (132, Figure 16), and a pyranochromone dimer (133, Figure 16), in addition to several known compounds.83 Compound 131 was tested for its antibacterial activity against five reference bacterial strains (three Gram-positive and two Gram-negative bacteria), three multidrug-resistant isolates from the environment, and a clinical isolate (extended-spectrum β-lactamase producer, ESBL) E. coli SA/2. In the range of concentrations tested, the compound did not show any activity.

Han and co-workers screened out for bioactive molecules from deep-sea fungus, the fungal strain Penicillium thomii YPGA3, isolated from the sediments at a depth of 4500 m in the Yap Trench.84 The 1H NMR spectrum and HPLC-DAD fingerprint of the EtOAc extract of this strain suggested the presence of chromone derivatives, and as a result, eight new chromone derivatives, namely penithochromones M–T (134–141, Figure 16), along with two known analogs, were isolated. These compounds were evaluated as α-glucosidase inhibitors, and the results showed that compounds 139, 140, and 141 exhibited comparable effects as the positive control acarbose (1.33 mM) with IC50 values of 842, 917, and 1017 μM, respectively. Compounds 134–141 were also assessed for their antioxidant activity, at the initial concentration of 1 mM, using a DPPH radical assay. The data found revealed that all tested compounds exhibit very weak inhibition (less than 50%).84 More recently, additional research by this group on the same fungal strain led to the isolation of three new chromone analogs, named penithochromones U–W (142–144, Figure 16).85 These compounds were screened for their inhibitory effect toward the α-glucosidase at the initial concentration of 200 μM, and they were inactive with inhibition rate less than 30%.

Putra and colleagues have isolated several bioactive secondary metabolites including a new chromone, named pseudopestalone (145, Figure 16), from the fermentation broth of the marine-derived fungus Pseudopestalotiopsis sp. PSU-AMF45.86 Among the isolated compounds, a known chromone, 2,3-dihydro-5,8-dihydroxy-2,2-dimethylchromen-4-one (146, Figure 16), was also isolated as a natural product for the first time. Their structures were identified by spectroscopic data including 1D and 2D NMR. The isolated compounds, 145 and 146, were evaluated for antibacterial activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria as well as antifungal activity against Candida albicans and Cryptococcus neoformans. It was found that these compounds were inactive at the concentration of 200 μg/mL against all bacterial strains. Compounds 145 and 146 displayed no antifungal activity.86

Endophytic Diaporthe sp. is a widely distributed fungal genus that has aroused much interest within the scientific community due to its strong biosynthetic capability to produce bioactive metabolites.

During their search for biologically meaningful and structurally unique compounds, Guo at al isolated five new chromone-derived polyketides phaseolorins A–E (147–151, Figure 17), from the deep-sea derived fungus Diaporthe phaseolorum FS431.87 The structures of new compounds were determined by analysis of their spectroscopic data, and it was found that compound 148 represented the first example of a new family of chromone derivative possessing an unprecedented recombined five-member γ-lactone ring. The new compounds (149–151) were evaluated for in vitro cytotoxic activities against three human cancer cell lines: liver cancer (HepG-2), breast cancer (MCF-7), and human glioblastoma carcinoma (SF-268). None of the compounds showed significant cytotoxicity activity even at a concentration of 100 μM.

Figure 17.

New chromones and chromanones (147–163) isolated from fungi.

During their systematic chemical investigation of the marine-derived fungus Diaporthe sp. XW12-1, Xing and co-workers isolated four new chromone compounds, diaporspchromanones A–C (152–154, Figure 17) and diaporspchromanone H (155, Figure 17).88 The structures of the new compounds were elucidated by extensive spectroscopic analysis, and their anti-inflammatory activity was evaluated against LPS-activated NO production in RAW264.7 cells. Compounds 153 and 154 showed potent anti-inflammatory effects compared to the positive control (indomethacin, IC50, 70.33 ± 0.95 μM) with IC50 values of 19.06 ± 3.60 and 9.56 ± 0.18 μM, respectively. The results obtained also indicated that 155 showed no cytotoxicity toward RAW264.7 cells.

During their studies on cell cycle inhibitors obtained from natural sources, Honda and colleagues found that the extract of a fungus Akanthomyces sp., isolated from a green algae Trentepohlia sp., inhibits the cell cycle of cancer cells at the S/G2/M phase. Bioassay-guided fractionation of the extract afforded an undescribed chromone glycoside, 9-hydroxyeugenetin 9-O-β-D-(4-O-methyl) glucopyranoside (156, Figure 17).89 The structure of the compound was elucidated by spectroscopic analysis and evaluated for its cytotoxic activity against HeLa/Fucci2 cells. The results showed that compound 156 had no cytotoxic activity at 100 μM.

Entomopathogenic fungi are a special group of soil-dwelling microorganisms that infect and kill insects and other arthropods. They currently are used as biocontrol agents, playing a vital role for the effective and rational control of insect pests. Fungi belonging to the genus Aschersonia, cause severe epizootics on whiteflies and some other coccids in tropical and subtropical regions of the globe and are well-known for their specificity. This genus has been known as a rich source of structurally diverse secondary metabolites with a variety of biological activity outcomes. During their continuing search for new biologically active substances from fungi collected from various habitats in Thailand, Sadorn and colleagues reported the isolation of twenty-one compounds including three new chromone derivatives, ascherlactones A (157, Figure 17) and B (158, Figure 17), ascherchromanone A (159, Figure 17), and two known chromones, eugenin and 5-hydroxy-2,3-dimethyl-7-methoxychromone, from the entomopathogenic fungus Aschersonia confluens BCC53152.90 Compounds obtained in sufficient amounts were tested for antimalarial against P. falciparum (K1, multidrug-resistant strain), antitubercular against M. tuberculosis H37Ra, antifungal against C. albicans, and antibacterial activities against Gram-positive (B. cereus and E. faecium) and Gram-negative (A. baumannii, E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and P. aeruginosa) bacteria, as well as for cytotoxicity against cancerous (MCF-7, KB, and NCI-H187) and noncancerous (Vero) cells. Due to limited amount of substance, compounds 158 and 159 were not tested for biological activity. The data found showed that 5-hydroxy-2,3-dimethyl-7-methoxychromone possess cytotoxicity against Vero cells with an IC50 value of 194.90 μM, and 157 was inactive against all biological tests at the maximum tested concentration.90

Endolichenic fungi are diverse groups of predominantly filamentous fungi that reside asymptomatically in the interior of lichen thalli. In recent years, the isolation of natural products from cultures of endolichenic fungi has attracted increased attention related with the production of bioactive metabolites possessing new structures and representing different structural classes.91 The fungus Daldinia species is widely distributed around the world; however, only a limited number of secondary metabolites have been reported from endolichenic fungus Daldinia species found in lichen.92

Following their search for various bioactive secondary metabolites from this fungus, Zhang et al. reported the isolation of two new chromone derivatives, (5R,7R)-5,7-dihydroxy-2-methyl-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-4H-chromen-4-one (160, Figure 17) and (5R,7R)-5,7-dihydroxy-2-propyl-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-4H-chromen-4-one (161, Figure 17), together with two known chromone compounds, (5R,7S)-5,7-dihydroxy-2-methyl-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-4H-chromen-4-one (162, Figure 17) and (5R,7S)-5,7-dihydroxy-2-propyl-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-4H-chromen-4-one (163, Figure 17), from the endolichenic fungus Daldinia sp. CPCC 400770.92 The isolated compounds were evaluated for anti-influenza A virus (IAV), anti-Zika virus (ZIKV), and antibacterial (S. aureus ATCC 29213 and E. coli ATCC 25922) activities. Compounds 160 and 162 displayed significant anti-influenza A virus (IAV) activities, with IC50 values of 16.1 μM and 9.0 μM, respectively, which were stronger than the positive control, ribavirin (IC50 = 21.7 μM). Structure–activity relationship analysis for chromone analogues (160–162) indicated that the substitution group at C-2 plays an important role in anti-IAV activity, and the 7-OH substitution has little effect. The chromone derivatives showed no antibacterial activities at the concentration of 32 μg/mL. According to the authors, the results gathered suggests that the genus Daldinia might be an important source for antiviral natural products.

3. Conclusions

Nature has been and will always be an inexhaustible source of chemical biodiversity of relevant value to humanity. Nature is a supreme molecular architect giving us a free chemical library with innovative information that can be used to solve a diversity of problems. Natural products offer structural diversity, and potent and effective compounds, which can sometimes be used to obtain semisynthetic derivatives. However, some difficulties remain, particularly in terms of isolation and identification, as they are complex chemical mixtures, difficulty in obtaining suitable quantities for the envisaged application, and, in some cases, the associated toxicity.

In this review efforts have been done to demonstrate that Nature continues to provide interesting compounds that are relevant to the discovery and development of new drugs and for other added value industrial applications. In particular, marine environment, which covers approximately 72% of the Earth’s surface and it is the largest unexplored aqueous habitat of the planet, may possess a huge potential to provide more lead compounds that can be used for the development of novel drugs. In a highly competitive field such as pharmaceutical research, natural products can still provide unknown resources, allowing the discovery of new therapeutic weapons against diseases with an unmet need.

The development of pharmacologically active compounds based on natural scaffolds and the development of new and improved druglike libraries are fundamental to speed up the discovery of new drugs. As shown in this review some biological screenings are still in a very early phase. In the upcoming years, it is expected that chromones and chromanones, coming from diverse origins, can be tested toward other targets and provide natural-based leads that can act as multitarget ligands. This new paradigm must be applied to natural-based drug discovery programs in the near future, extending the value of natural-based compounds.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by FEDER funds through the Operational Programme Competitiveness Factors-COMPETE and national funds by FCT–Foundation for Science and Technology under research grants (DOI:10.54499/UIDB/00081/2020, LA/P/0056/2020 (IMS), EXPL/MED-QUI/1156/2021). A.G. gratefully acknowledges for the financial support through contract DL 57/2016/CP1454/CT0008 (DOI: 10.54499/DL57/2016/CP1454/CT0008).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Newman D. J.; Cragg G. M. Natural Products as Sources of New Drugs over the Nearly Four Decades from 01/1981 to 09/2019. J. Nat. Prod 2020, 83 (3), 770–803. 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.9b01285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesan A.An Uneasy Past but a Glorious Future. In Combinatorial synthesis of natural product-based libraries. In Combinatorial Synthesis of Natural Product-Based Libraries, 1st ed.; Boldi A.M.E., Ed.; CRC Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hong J. Role of natural product diversity in chemical biology. Curr. Opin Chem. Biol. 2011, 15 (3), 350–354. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amen Y. Naturally Occurring Chromone Glycosides: Sources, Bioactivities, and Spectroscopic Features. Molecules 2021, 26 (24), 7646. 10.3390/molecules26247646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey A. L.; Edrada-Ebel R.; Quinn R. J. The re-emergence of natural products for drug discovery in the genomics era. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2015, 14 (2), 111–129. 10.1038/nrd4510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howes M.-J. R.; et al. Molecules from nature: Reconciling biodiversity conservation and global healthcare imperatives for sustainable use of medicinal plants and fungi. PLANTS, PEOPLE, PLANET 2020, 2 (5), 463–481. 10.1002/ppp3.10138. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Atanasov A. G.; et al. Natural products in drug discovery: advances and opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2021, 20 (3), 200–216. 10.1038/s41573-020-00114-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaspar A.; et al. Chromone: a valid scaffold in medicinal chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114 (9), 4960–4992. 10.1021/cr400265z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]