ABSTRACT

Microbes synthesize and secrete siderophores, that bind and solubilize precipitated or otherwise unavailable iron in their microenvironments. Gram (−) bacterial TonB-dependent outer membrane receptors capture the resulting ferric siderophores to begin the uptake process. From their similarity to fepA, the structural gene for the Escherichia coli ferric enterobactin (FeEnt) receptor, we identified four homologous genes in the human and animal ESKAPE pathogen Klebsiella pneumoniae (strain Kp52.145). One locus encodes IroN (locus 0027 on plasmid pII), and three other loci encode other FepA orthologs/paralogs (chromosomal loci 1658, 2380, and 4984). Based on the crystal structure of E. coli FepA (1FEP), we modeled the tertiary structures of the K. pneumoniae FepA homologs and genetically engineered individual Cys substitutions in their predicted surface loops. We subjected bacteria expressing the Cys mutant proteins to modification with extrinsic fluorescein maleimide (FM) and used the resulting fluorescently labeled cells to spectroscopically monitor the binding and transport of catecholate ferric siderophores by the four different receptors. The FM-modified FepA homologs were nanosensors that defined the ferric catecholate uptake pathways in pathogenic strains of K. pneumoniae. In Kp52.145, loci 1658 and 4984 encoded receptors that primarily recognized and transported FeEnt; locus 0027 produced a receptor that principally bound and transported FeEnt and glucosylated FeEnt (FeGEnt); locus 2380 encoded a protein that bound ferric catecholate compounds but did not detectably transport them. The sensors also characterized the uptake of iron complexes, including FeGEnt, by the hypervirulent, hypermucoviscous K. pneumoniae strain hvKp1.

IMPORTANCE

Both commensal and pathogenic bacteria produce small organic chelators, called siderophores, that avidly bind iron and increase its bioavailability. Klebsiella pneumoniae variably produces four siderophores that antagonize host iron sequestration: enterobactin, glucosylated enterobactin (also termed salmochelin), aerobactin, and yersiniabactin, which promote colonization of different host tissues. Abundant evidence links bacterial iron acquisition to virulence and infectious diseases. The data we report explain the recognition and transport of ferric catecholates and other siderophores, which are crucial to iron acquisition by K. pneumoniae.

KEYWORDS: siderophores, iron transport, TonB-dependent iron acquisition, fluorescent sensors, Klebsiella pneumoniae, ferric enterobactin, site-directed mutagenesis, siderophore antibiotic conjugates, ESKAPE pathogen

INTRODUCTION

Klebsiella pneumoniae is an encapsulated, non-motile Gram (−) bacillus that may inhabit the mammalian gastrointestinal tract as a commensal or a pathogen. Classical K. pneumoniae (cKP) infiltrates the urinary tract, bloodstream, lungs, and surgical wounds, leading to urinary tract infections, bacteremia, sepsis, pneumonia, and wound infections, primarily in healthcare settings. It is challenging to treat patients infected with cKp, because it tends to acquire multiple antibiotic resistances, including to carbapenems, cephalosporins, and monobactams, from the production of extended-spectrum β-lactamases and/or carbapenemases (1, 2). Another pathotype, hypervirulent K. pneumoniae (hvKP), is globally recognized for its association with hepatic abscesses, endophthalmitis, meningitis, osteomyelitis, and necrotizing fasciitis in otherwise healthy individuals (3, 4). Multiple virulence factors play essential roles in infections with K. pneumoniae, including capsule and fimbriae production, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), and elaboration of siderophores. Multi-drug-resistant (MDR) or extremely drug-resistant (XDR) strains of K. pneumoniae present challenges for healthcare providers worldwide. It is estimated that unless antibiotic resistance decreases or new therapies are developed, in 2050, ~ 10 million lives will yearly be lost to drug-resistant infections (5), with associated economic loss of $100 trillion per year. The ESKAPE bacteria (Enterococcus, Staphylococcus, Klebsiella, Acinetobacter, Pseudomonas, and Enterobacter) are prototypic in this category, from their propensity to acquire MDR and XDR properties (6).

Iron is an essential redox-active cofactor in many biochemical reactions and bioenergetic pathways of pro- and eukaryotes. However, Fe3+ precipitates in aqueous environments, and eukaryotes sequester it. Mammalian iron-binding and storage proteins [siderocalin (SCN), transferrin, lactoferrin, and ferritin] minimize the amount of free iron available to invading microorganisms (7). Consequently, both commensal and pathogenic bacteria produce small organic chelators, called siderophores, that avidly bind iron and increase its bioavailability. K. pneumoniae variably produces four siderophores that antagonize host iron sequestration: enterobactin (Ent), glucosylated enterobactin (GEnt; also termed salmochelin), aerobactin (Abn), and yersiniabactin (Ybt) (8). Ent production is ubiquitous in both classical and hypervirulent K. pneumoniae, in both the wild and host environments. The elaboration of multiple siderophores promotes colonization of different host tissues (1, 9) and creates iron uptake redundancy that may overcome host neutralization of any particular ferric siderophore. Finally, abundant evidence links bacterial iron acquisition to virulence and infectious disease (10). Gram (−) bacteria, including K. pneumoniae, initiate ferric siderophore acquisition by TonB- and proton-motive force-dependent iron uptake through high-affinity outer membrane (OM) receptor proteins (11). Consequently, antibiotics that target TonB-dependent pathways may reduce pathogenesis (10). The exploitation of these uptake mechanisms with antibiotics may suffer less from resistance, because bacteria with altered TonB, or completely lacking TonB, do not thrive in iron-deficient host environments (12, 13).

OM ferric siderophore receptors are TonB-dependent members of the porin superfamily. Hence, they are called TonB-dependent transporters (14) or ligand-gated porins [LGP (15)], in the latter case because ligand binding activates their TonB-dependent transport process. The fluorescent modification of LGP, or soluble siderophore binding proteins, allows spectroscopic measurements of their biochemical activities and functional properties. For example, modification of site-directed Cys substitutions in the Escherichia coli LGP Fiu, FepA, and Cir with fluorescein maleimide (FM) facilitated the measurement of their binding specificities, affinities for various ligands, and transport properties (16). In a TonB-deficient host, FM- labeled LGP constitutes fluorescent decoy (FD) sensors (17) that adsorb specific ligands but do not transport them. Analysis of quenching of a decoy sensor reveals the concentration of its target ligand in solution, which enables sensitive determinations of the same ligand’s uptake by other cells. This methodology facilitates measurements of FeEnt binding and transport by numerous bacterial species at even nanomolar concentrations. It is also compatible with microtiter fluorescence high-throughput screening, which discovered compounds that inhibit TonB action (18).

In this study, we identified, cloned, genetically engineered, and fluorescently labeled the FepA orthologs of K. pneumoniae. From a genome-wide search of K. pneumoniae strain Kp52.145 (19), we found four active structural genes that were >50% identical to E. coli fepA: the plasmid pII locus 0027 and the chromosomal loci 1658, 2380, and 4984. The first locus encodes a protein synonymous with IroN, which recognizes and transports FeGEnt. After engineering Cys residues at points of interest in these FepA orthologs/paralogs of K. pneumoniae (KpnFepAs), we characterized their binding specificities and transport capabilities for different catecholate ferric siderophores. The fluorescent sensors functioned in K. pneumoniae (i.e., as species-specific sensors) and in the TonB-deficient E. coli strain OKN1359, where they bound but did not transport ligands (i.e., functioned as decoy sensors) (17). These receptors bound catecholate ferric siderophores with a range of affinities (nanomolar to micromolar), and we used them to define and understand the iron transport activities of K. pneumoniae and other Gram (−) bacterial CRE/ESKAPE pathogens.

RESULTS

Identification of potential ferric catecholate siderophore receptors in Klebsiella pneumoniae and sensor strain construction

Based on sequence homology to E. coli FepA (EcoFepA), we identified four genes in the genome of K. pneumoniae strain Kp52.145 that potentially encoded and were annotated as TonB-dependent transporters of FeEnt. Relative to EcoFepA (PDB entry 1FEP), CLUSTALΩ alignments of proteins encoded by a single plasmid locus (0027) and three chromosomal loci (1658, 2380, 4984) revealed varying degrees of identity: 52%, 82.2%, 51.6%, and 70.9%, respectively. The most distant chromosomally encoded protein, KpnFepA_2380, is 65.9% identical to EcoIroN (17, 20), which is itself 92% identical to KpnIroN. The consensus Fur recognition sequence motif GATAAT (21, 22) was present in the promoter regions of all the structural genes for these proteins, implying their regulation by extracellular iron availability.

We cloned each orthologous structural gene in the low copy vector pITS23 (23), preceded by the EcofepA promoter and signal sequence regions, so that they were consistently expressed, iron-regulated, and assembled in the OM of E. coli host strains. We employed site-directed deletion derivatives (23) of E. coli strain BN1071 (24) as hosts for the plasmids: OKN3 (ΔentA, ΔfepA), OKN359 (ΔentA, ΔfepA, Δcir, and Δfiu) and OKN13 (ΔentA, ΔtonB, and ΔfepA). When expressing an LGP of interest, OKN3 and OKN359 (both tonB+) were capable of ferric catecholate binding and transport; OKN13 (ΔtonB), on the other hand, bound but could not transport iron complexes. For binding and transport experiments, we grew the bacteria in iron-deficient MOPS minimal medium to maximize the expression of the iron-regulated KpnFepA orthologs. Analysis of the OM fractions (Fig. S1) confirmed the overproduction of the different plasmid-encoded KpnFepAs in the E. coli host strains.

Generation, fluorescent labeling, and analysis of Cys mutant derivatives

Crystallographic structural data are not yet available for any of the KpnFepA proteins. However, each of them contains >50% identity to EcoFepA, ensuring a similar protein fold (25, 26). So, for the design of site-directed Cys substitution mutants, we employed EcoFepA (1FEP) as a prototype in the MODELLER algorithm (27) of CHIMERA [UCSF (28)]. After aligning the KpnFepA sequences with that of EcoFepA (1FEP) by CLUSTALΩ, MODELLER predicted their tertiary structures (Fig. 1 and 2; Fig. S2 and S3). Based on prior fluorescent modification of EcoFepA (29, 30), the crystal structure 1FEP (31), and the ensuing models of the KpnFepAs, we engineered individual Cys residues in predicted surface loops of the KpnFepA receptors as candidates for fluoresceination. We made the following site-directed Cys mutants (Fig. 1 and 2; Fig. S2 and S3):

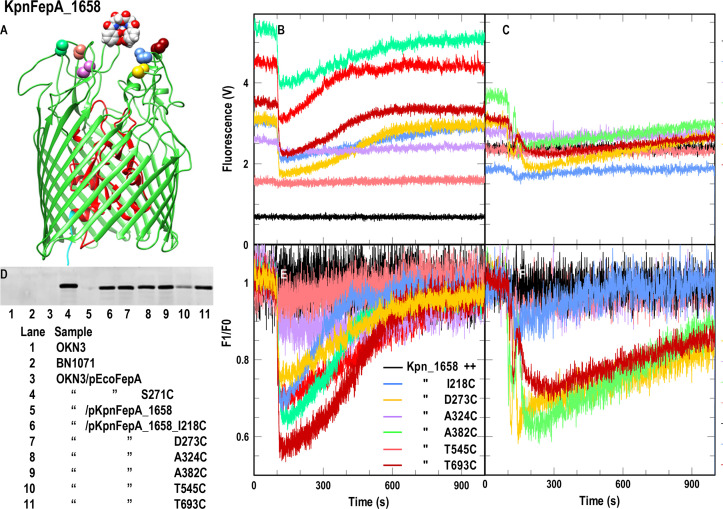

Fig 1.

FeEnt transport by KpnFepA_1658. (A and D) Site-directed fluorescence labeling of KpnFepA_1658 Cys mutants. (A) Location of engineered Cys residues in KpnFepA_1568 (see the legend in panel E for color-coding). (D) After growth of E. coli OKN3/pKpnFepA_1658 and its Cys mutants in iron-deficient MOPS media, we exposed the cells to FM and evaluated labeling by a fluorescence scan of their SDS-PAGE-resolved cell envelopes. All the mutant KpnFepAs were well labeled, T545C slightly less intensely than the others. (B and E) Spectroscopic observations of FeEnt uptake by E. coli OKN3/pKpnFepA_1658 Cys mutants. To 5 × 106 cells in a stirred 3-mL cuvette containing 2-mL of PBS + 0.4% glucose, we added FeEnt to 10 nM at 100 s and collected the raw data (B) for 1,000 s. FeEnt binding quenched the fluorescence of most mutant proteins, but fluorescence intensity recovered as the bacteria transported FeEnt and depleted it from the ambient solution, The plotted data represent the mean values from triplicate time courses of each of individual mutant. (E) We also normalized the data to the initial cellular fluorescence (F/F0). (C and F) Spectroscopic observations of FeEnt uptake by pKpnFepA_1658 Cys mutants in K. pneumoniae. We repeated the experiment for the same Cys mutants in K. pneumoniae strain KKN5, with similar results. Panels (B andAND C) depict the fluorescence quenching time courses as raw data: each of the fluorescently labeled Cys mutants had a different initial intensity and different extents of quenching in response to the binding/transport of FeEnt. In panels (E andAND F), the initial intensity of each of the fluoresceinated Cys mutants is normalized to an arbitrary value of 1.0, to better compare their responses to the subsequent binding and transport of FeEnt.

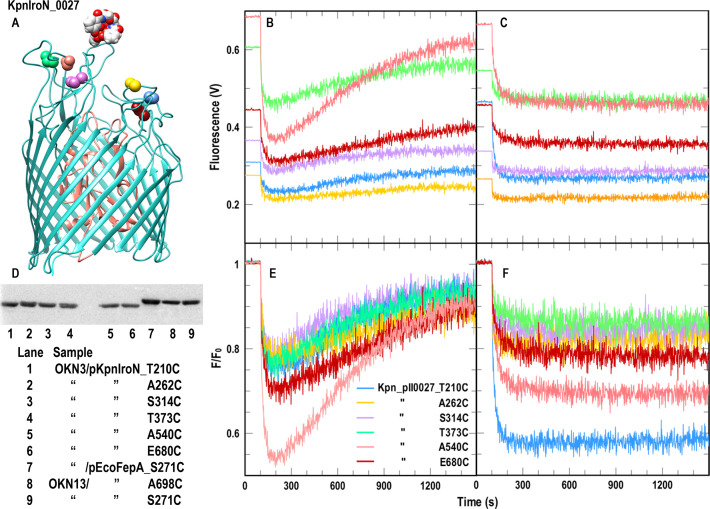

Fig 2.

FeEnt transport and FeGEnt binding by KpnIroN_0027. (A and D) Site-directed fluorescence labeling of KpnIroN Cys mutants. (AND) Location of engineered Cys residues in KpnIroN_0027 (see the legend in panel E for color-coding). (D) We repeated the protocol described in Fig. 1 with E. coli OKN3/pKpn_0027 and its Cys derivatives; all the mutants were well labeled. (B and E) Spectroscopic observations of FeEnt uptake by E. coli OKN3/pKpnIroN_0027. Following the protocol described in Fig. 1, FM-labeled KpnIroN Cys mutants efficiently transported FeEnt, even when expressed in E. coli: raw (B) and normalized (E) data. (C and F) Spectroscopic observations of FeGEnt binding, but not uptake, by E. coli OKN3/pKpnIroN_0027 and its Cys mutants. We repeated the experiment described in panels (B and E) with FeGEnt: raw (C) and normalized (F) data. FeGEnt binding rapidly quenched fluoresceinated KpnIroN Cys mutants, but the absence of lactone esterases IroD and IroE from the E. coli periplasm prevented its cellular uptake.

After sequencing their structural genes to validate their construction, we performed siderophore nutrition tests of the mutant receptors, expressed in OKN359 (Fig. S4). The experiments showed that the Cys substitutions did not compromise the FepA homologs’ ability to transport their respective ferric catecholate ligands. Wild-type KpnIroN_0027 and KpnFepA_1658 and their Cys mutant derivatives acquired FeEnt just like EcoFepA. KpnFepA_4984 and its Cys mutants, on the other hand, produced larger, more diffuse halos around discs of FeEnt than those from KpnFepA_1658, KpnIroN, or EcoFepA. Larger halos generally correlate with slower FeEnt uptake (32, 33). Finally, neither KpnFepA_2380 nor its Cys substitution mutants transported FeEnt (nor any other ferric catecholate that we tested) in siderophore nutrition tests, suggesting specificity for another, currently unidentified iron complex.

Native E. coli FepA contains two Cys residues in loop 7 (L7; C487 and C494), which form a disulfide bond that is indispensable to FeEnt uptake: elimination of either or both C487 and C494 abrogates FeEnt transport by EcoFepA (29, 30, 34). Furthermore, C487 and C494 are unreactive with extrinsic maleimide reagents (35) unless the native disulfide that they form in L7 is reduced (e.g., by β-mercaptoethanol or dithiothreitol). Consequently, unreduced EcoFepA containing single Cys substitutions in its surface loops is accessible to labeling by FM (17, 29). Similarly, mature KpnFepA_1658 contains homologous amino acids C482 and C489, separated by six residues in its projected L7, that presumably also form a disulfide bond. We transformed pKpnFepA_1658 and its Cys mutants into OKN3 and labeled the iron-deficient living bacteria with 5 µM fluorescein maleimide (FM) at pH 6.7 for 15′ at 37°C, resulting in nearly exclusive fluorescence labeling of the engineered Cys thiols (Fig. 1; Fig. S1). Like EcoFepA, in the absence of reduction, C482 and C489 were not modified by FM: FM did not label wild-type KpnFepA_1658, but it strongly and selectively labeled all the KpnFepA_1658 Cys mutants, to a level comparable to that of EcoFepA_A698C (Fig. 1; Fig. S1). We also evaluated FM labeling of these constructs in K. pneumoniae host KKN5 (entA, Δ0027, Δ1658, Δ2380, Δ4984). Three of the Cys derivatives (D273C, A382C, and T693C) were strongly labeled, whereas three others (I218C, A324C, and especially T545C) were less labeled than they were in E. coli (Fig. S1B). This differential level of covalent modification likely derives from the more extensive LPS core, O-antigen, and capsule in K. pneumoniae, which create a more hydrophilic surface than that of rough E. coli K-12 and may obscure access to certain loops of an OM protein (36). Like EcoFepA, all the KpnFepA homologs contain closely paired Cys residues in predicted L7 that presumably disulfide bonds: 0027 (C475, C484); 1658 (C482, C489); 2380 (C451, C460); 4984 (C490, C497). As with EcoFepA, the wild-type forms of these proteins were not alkylated when treated with FM (Fig. 1; Fig. S3). However, the Cys derivatives of KpnIroN, KpnFepA_1658, and KpnFepA_4984, expressed in iron-deficient E. coli OKN3 or K. pneumoniae KKN5, were well labeled by 5 µM FM in vivo (Fig. 1 and 2; Fig. S2 and S3). The extent of labeling of the Cys mutant derivatives of KpnFepA_2380 was less than that of the other KpnFepA Cys derivatives (Fig. S2). Nevertheless, together, the results showed that the Cys mutants of KpnIroN, KpnFepA_1658, and KpnFepA_4984 were susceptible to modification by FM, and their fluorescent derivatives all detected the transport of FeEnt.

Fluorescent spectroscopic assays of FeEnt transport by KpnFepAs

Fluorescently labeled LGP reflect the binding and uptake of their ligands (17, 37–39). We characterized the ability of the genetically engineered, fluorescently labeled KpnFepA Cys mutants to monitor FeEnt uptake, in E. coli and K. pneumoniae.

KpnFepA_1658

The Cys substitution mutants of KpnFepA_1658 illustrated the general trends of these experiments: when expressed in E. coli, they had different levels of fluoresceination and different extents of quenching by bound FeEnt, leading to different kinetics of fluorescence recovery as they utilized extracellular FeEnt and depleted it from the cuvette (Fig. 1B and E). Overall, quenching ranged from 5% to 45%, but FeEnt quenched D273C-FM, A382C-FM, and T693C-FM better than I218C-FM, A324C-FM, and T545C-FM. The former three mutant strains rapidly acquired extracellular FeEnt (within 10–15 min). We screened the same FM-labeled Cys mutants in K. pneumoniae KKN5 (Fig. 1C and F; Fig. S1): again, D273C, A382C, and T693C quenched to greater extents (up to 40%) by FeEnt and acquired FeEnt (leading to fluorescence recovery) within 15–20 min. Figure 1B and C depict the fluorescence quenching time courses as raw data: each of the different fluoresceinated Cys mutants has a different initial fluorescence intensity and different extents of quenching in response to the binding/transport of FeEnt. In Fig. 1E and F, we normalized the initial intensity of each of the fluoresceinated Cys mutants to 1.0, to better compare their quenching responses to the subsequent binding and transport of FeEnt.

KpnIroN

The Cys mutants of KpnIroN_0027) behaved nearly identically to those of KpnFepA_1658: we observed 10%–50% quenching by FeEnt and uptake of the ferric siderophore within 15–20 min (Fig. 2) by its fluoresceinated Cys mutants. Additionally, Cys derivatives of KpnIroN bound FeGEnt (Fig. 2) but did not transport it in E. coli because it lacks the periplasmic or components (IroD, IroE) that are needed for FeGEnt uptake. As in Fig. 1, Fig. Fig. 2B and C depict the fluorescence quenching time courses as raw data: each of the different fluoresceinated Cys mutants has a different initial fluorescence intensity and different extents of quenching in response to the binding/transport of FeEnt. In Fig. 2E and F, we normalized the initial intensity of each of the fluoresceinated Cys mutants to 1.0, to better compare their quenching responses to the subsequent binding and transport of FeEnt.

KpnFepA_2380

KpnFepA_2380 was not well expressed in the E. coli host strain, and its Cys mutants were only weakly labeled by FM. FeEnt binding to its fluorescently labeled mutants resulted in 5% (T316C-FM) to 20% (T255C-FM) quenching. However, the quenched fluorescence did not rebound, even after 90 min, in either E. coli or K. pneumoniae cells (Fig. S2), suggesting that FeEnt was not transported by this homolog.

KpnFepA_4984

A different fluorescence labeling pattern emerged for the Cys mutants of KpnFepA_4984. Except for A332C, FM modified all of its derivatives (S226C, T281C, A390C, T534C, and T703C), but to a lesser extent (Fig. S3) than observed for the Cys derivatives of EcoFepA_A698C, KpnFepA_1658, and KpnIroN. Nevertheless, the labeling efficiency was sufficient for the observation of FeEnt binding and transport. FeEnt binding was best observed in KpnFepA_4984 mutants T281C and A390C, which showed ~20% quenching upon adsorption of FeEnt (Fig. S3). It also took longer for the quenched fluorescence of T281C-FM and A390C-FM to rebound to original levels (~30 min), reiterating the slower FeEnt uptake through this receptor that we also observed in siderophore nutrition tests.

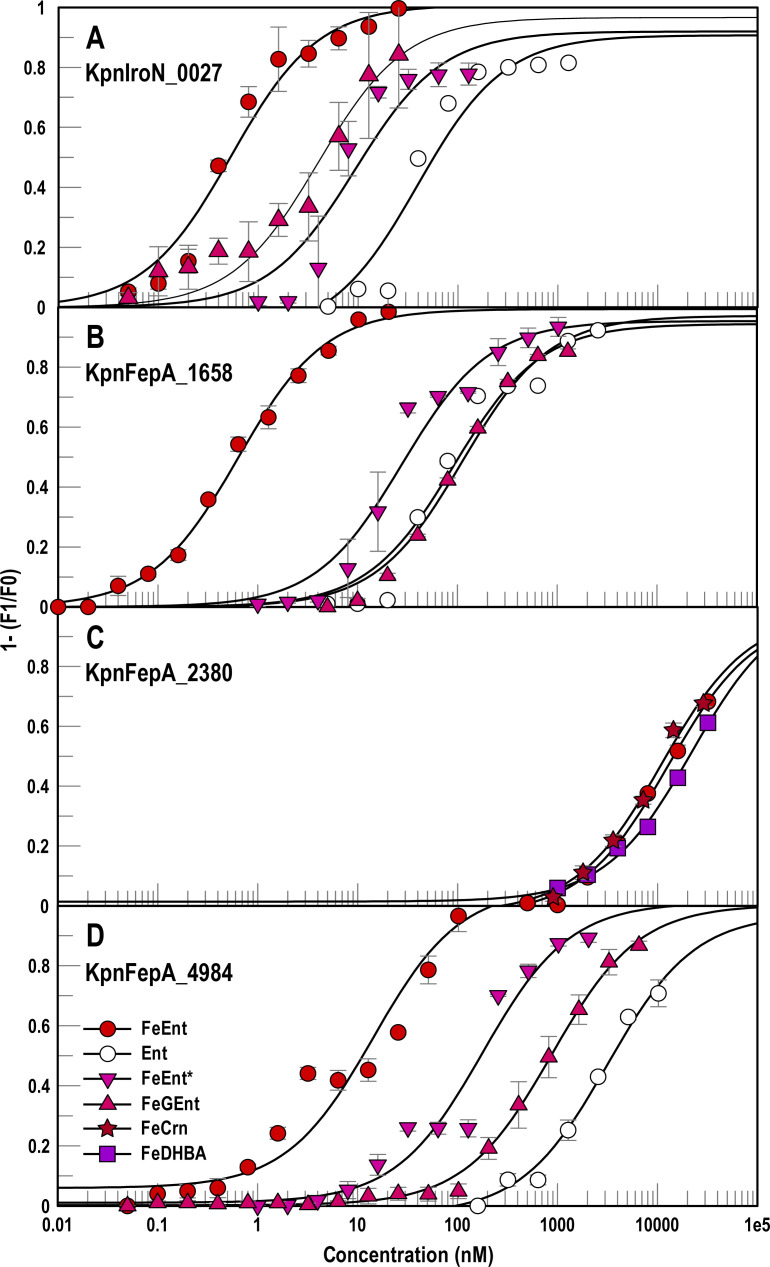

Selectivities of KpnFepAs for ferric catecholates

We transformed the expression vectors of the KpnFepA homologs into E. coli OKN13 [entA, ΔtonB, and ΔfepA (23)], which binds but does not transport ferric siderophores. This configuration creates “decoy sensors” (17), that optimally measure ligand binding without the added complication of concomitant ligand uptake (17, 38). Based on FM labeling efficiency, quantum yield, and extent of quenching, we chose constructs for binding determinations in OKN13: KpnFepA_1658_A382C; KpnIroN_T210C; KpnFepA_2380_T255C; KpnFepA_4984_A390C. The constructs depicted the binding of various ferric catecholates to the FepA homologs of K. pneumoniae, revealing their respective affinities (Fig. 3). Apart from binding their primary ligand, FeEnt, with high affinity, and its aposiderophore Ent with 100–200-fold lower affinity (38), KpnFepA_1658, KpnIroN, and KpnFepA_4984 showed different preferences for ferric catecholate complexes and siderophore antibiotics cefiderocol [FeFDC (40, 41)] and FeMB-1 (42, 43):

Fig 3.

Recognition of ferric catecholates by different KpnFepAs. We engineered Cys substitutions in the structural genes of KpnIroN_0027, KpnFepA_1658, KpnFepA_2380 and KpnFepA_4984, carried on pITS23 (see Results and Supplemental Materials). After labeling E. coli OKN13 cells expressing the Cys mutant proteins with FM, we assessed their fluorescence intensity and extent of quenching during ligand binding to find the best candidates for further study: KpnFepA_IroN_T210C-FM (panel A); KpnFepA_1658_A382-FM (B); KpnFepA_2380_T255C-FM (C); KpnFepA_4984_A390C-FM (D). With these constructs, we measured the adsorption of ferric catecholate siderophores: FeEnt, Ent, FeEnt*, FeGEnt, FeDHBA, FeCrn. Each data point represents the mean of triplicate repetitions, with associated standard deviations. For KpnIroN_0027 the KD values (nM) from the fitted curves are FeEnt 0.4 ± 0.1, FeGEnt 4 ± 1, FeEnt* 9.4 ± 3.5, Ent 39 ± 15. For KpnFepA_1658 the KD values (nM) from the fitted curves are FeEnt 0.6 ± 0.05, FeEnt* 27 ± 6, Ent 92 ± 21, FeGEnt 112 ± 15. For KpnFepA_2380, the KD values (μM) from the fitted curves are FeEnt 16 ± 3, FeCrn 13 ± 2.5, and FeDHBA 19 ± 2.8. For KpnFepA_4984, the KD values (nM) from the fitted curves are FeEnt 14 ± 4.5, FeEnt* 178 ± 51, FeGEnt 872 ± 64, Ent 3,171 ± 808.

KpnFepA decoy sensors of iron transport by ESKAPE pathogens

Like EcoFepA-FM, in a TonB-deficient, iron transport-defective bacterium, the fluoresceinated KpnFepA proteins act as passive sensors that bind but do not internalize iron complexes (17). Consequently, the extent of their quenching indirectly measures the concentration of their ferric catecholate ligand(s) in solution. In this way, FD sensors quantitatively depict the uptake of a particular ligand by other microorganisms. Hence, the fluorescence intensity of the construct E. coli OKN13/KpnFepA_1658_A382C-FM is inversely related to [FeEnt]extracellular, and if the sensor bacteria cohabitate with iron transport-competent bacteria, then their fluorescence emissions portray the time-resolved uptake of FeEnt by the other organism. We utilized OKN13/KpnFepA_1658_A382C-FM to monitor FeEnt uptake of wild isolates of the ESKAPE organisms K. pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Fig. 4A).

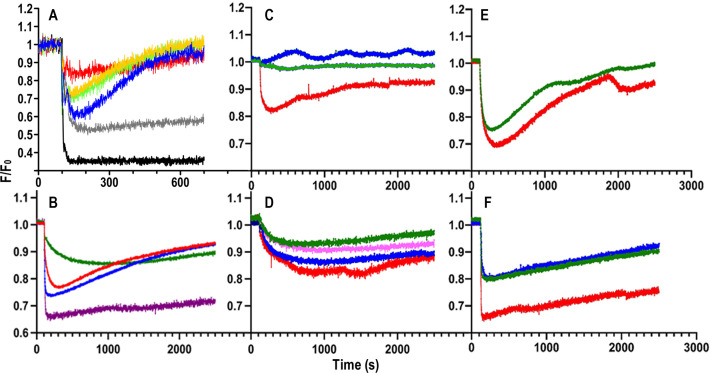

Fig 4.

FD sensor analysis of ferric siderophore uptake by Gram (−) ESKAPE bacteria. (A) Uptake of FeEnt. 107 cells of the decoy sensor strain E. coli OKN13/pKpnfepA_1658-FM were mixed with 107 cells of individual test bacteria in 2 mL of PBS + 0.4% glucose in a quartz cuvette. At t = 0 we began monitoring fluorescence emissions at 520 nm; at 100 s we added FeEnt to 5 nM and observed the ensuing changes in fluorescence intensity: black, sensor only; gray, K. pneumoniae KKN5; blue, E. coli OKN3/pKpnFepA_1658; red, K. pneumoniae 52.145; gold, A. baumannii; green, P. aeruginosa PA01. (B) Ferric siderophore uptake by hypermucoviscous K. pneumoniae. 107 cells of transport-defective E. coli OKN13, harboring plasmids expressing appropriate decoy sensors, were mixed with 107 cells of K. pneumoniae hvKp1 and monitored as described above in response to the addition of the following ferric siderophores at 100 s: blue, FeEnt; green, FeGEnt; red, FeAbn; purple, FeYbt. Panels (C–F) Effects of SCN on uptake of ferric siderophores by hvKp1. In each study 107 cells of E. coli OKN13, harboring plasmids expressing appropriate decoy sensors, were mixed with 107 cells of K. pneumoniae hvKp1, in the absence (red) or presence of human SCN (blue, 0.005 µM; magenta, 0.05; green, 0.5 µM). We monitored fluorescence emissions in response to the addition of 10 nM ferric siderophores at t = 100 s: (C) FeEnt; (D) FeGEnt; (E) FeAbn; (F) FeYbt.

FD sensor analysis of iron transport by pathogenic bacteria dramatically reduces the scope of laboratory manipulations with the infectious organism: it only requires propagation of the pathogen in iron-deficient conditions. We used this methodology to monitor iron acquisition by the hypervirulent, hypermucoviscous K. pneumoniae strain hvKp1 (44–46). Different FD sensors, expressed in E. coli OKN13 (38), showed the uptake of ferric siderophores by this heavily encapsulated natural isolate:

The uptake kinetics of the different ferric complexes by hvKp1 (Fig. 4A) were similar to those previously observed for E. coli (17, 38) and K. pneumoniae strain Kp52.145 (Fig. 1; Fig. S3), with the exception of FeGEnt. Rapid binding of FeEnt, FeAbn, and FeYbt (i.e., maximum quenching of their respective sensors within 100 s) was immediately followed by steady uptake by hvKp1, at different rates: FeYbt < FeAbn ≈ FeEnt. On the other hand, in the presence of hvKp1, FeGEnt adsorbed more slowly (i.e., maximum quenching of OKN13/pKpnIroN-T210C-FM at ~500 s) and transported at a much slower rate than FeEnt or FeAbn, roughly equivalent to that of FeYbt (Fig. 4B).

The sensors showed the effects of human SCN on the uptake of FeEnt, FeGEnt, FeAbn, and FeYbt by hvKpn1. Consistent with their binding affinities for the serum protein [FeGEnt, FeAbn, FeYbr << FeEnt (38)], SCN preferentially blocked the uptake of FeEnt, but not any of the other ferric siderophores (Fig. 4C through F). The inhibition resulted from the rapid binding of FeEnt by SCN, which competed with its binding to its FepA receptors (i.e., no quenching of EcoFepA_A698C-FM in the presence of SCN).

DISCUSSION

K. pneumoniae is distinguished by several of its virulence determinants, including its tendency to acquire antibiotic resistance, its encapsulation, and its ability to elaborate and transport numerous ferric siderophores. These traits make it a particularly dangerous member of the CRE/ESKAPE pathogen group. The inhibition of an essential biochemical pathway is a classical approach to antimicrobial therapy, and iron acquisition systems that associate with pathogenesis are potentially viable targets for antibiotic development. During the colonization in human and animal hosts, microbes must acquire iron for growth and proliferation (13), and it is noteworthy that K. pneumoniae produces several siderophores that promote invasiveness and pathogenesis: aerobactin, yersiniabactin, and the catecholate compound, glucosylated enterobactin. Hence, the understanding of the uptake pathways for FeEnt and FeGEnt and their degradation products has clinical importance related to their correlations with microbial virulence (47, 48).

Gram-negative bacteria acquire iron with TonB-dependent transport systems, whose OM LGP components select particular iron complexes among a plethora of ferric siderophores that may exist in the microenvironment. The specificities, affinities, and transport rates of each individual LGP determine their suitability for usage as FD sensors. The highest affinity sensors (e.g., EcoFepA) manifest sub-nanomolar affinities for their ligands (i.e., FeEnt: KD ≈ 0.5 nM), so their fluorescence response as sensors of ligand uptake spans 4 logs of FeEnt concentration, from 0.05 to 50 nM. TonB-dependent LGPs are slow transporters. The turnover number of EcoFepA is ~6 mol/min; a sample of 108 iron-deficient bacteria containing 105 FepA proteins/cell acquires 6 × 1013 (0.1 nMol) FeEnt/min, so over a period of 10–30 min EcoFepA-FM readily visualizes the uptake of 1–10 nMol FeEnt. Analogously, each fluorescent LGP effectively monitors a 3–4-log concentration range centered on its binding KD, but because less avid LGP sensors monitor a higher concentration range, it requires longer assay times for them to detect iron uptake. What this means in practice is that lower affinity LGPs (e.g., KpnFepA_4984) are less effective transport sensors.

Real-time live cell assays do not require purification or reconstitution of the numerous cell envelope components of TonB-dependent transport systems. Our findings broaden the scope of fluorescence spectroscopic assays by characterizing multiple ferric catecholate receptors in K. pneumoniae that recognize, bind, and transport FeEnt with different affinities. The selectivities of these receptors are relevant to the virulence mechanisms of Gram-negative bacterial ESKAPE pathogens. Virulent strains encode siderophore biosynthetic operons for the production of Ent, GEnt, Abn, and Ybt (1) and produce cognate receptor LGPs for their OM transport [(49); this report]. All these systems are Fur-regulated and activated upon iron deprivation in the host (50–52) or when grown under pathophysiological conditions (38). The elaboration and acquisition of the latter three siderophores are associated with the pathogenesis and hypervirulence of K. pneumoniae (1, 44, 53, 54). The spectroscopic sensor approaches we employed facilitated observations of the uptake of these ferric siderophores by K. pneumoniae. The assays revealed the unusual uptake kinetics of FeGEnt and the first quantitative description of FeGEnt transport by hypervirulent hypermucoviscous K. pneumoniae. Additionally, they confirmed the importance of aerobactin production and FeAbn uptake by hvKP1: it was transported at a rate similar to that of FeEnt, which was considerably faster than the rate of FeYbt transport. However, unlike FeEnt, FeAbn uptake was not inhibited by SCN, reinforcing its importance in the pathogenesis of hvKp1 (54).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids

Laboratory strains included E. coli MG1655 (55), K. pneumoniae Kp52.145 [Δwcz (19) (courtesy of Regis Tournebize and Barbara Corelli, Institut Pasteur)], P. aeruginosa PA01 (courtesy of Stephen Lory, Harvard University), and A. baumannii ATCC19798/ATCC 19606. E. coli laboratory strains descended from BN1071 [entA (24)]: OKN1 (ΔtonB), OKN3 (ΔfepA), OKN13 (ΔtonB, ΔfepA), and OKN359 (ΔfepA, Δfiu, Δcir). K. pneumoniae strain Kp52.145 was the source for four kpnfepA structural genes: plasmid II locus 0027 [kpniroN; GenBank locus CDO11656 (56, 57)] and chromosomal fepA loci 1658, 4984, and 2380. Kp52.145 harbors plasmid II, a 121.7-kB plasmid (57) that was only found in one other K. pneumoniae strain (B5055). The K. pneumoniae strain KKN5 (ΔentB, Δ0027, Δ1658, Δ2380, Δ4984) originated from Kp52.145 by sequential site-directed deletions. The resultant mutant strain did not synthesize Ent and GEnt nor transport ferric catecholates. It was an effective host for plasmids carrying fepA alleles. We used Luria broth (LB) (58) and iron-free MOPS (59) minimal medium reconstituted with micronutrients and amino acids, as required according to the need of the experiment. We prepared apo and ferric siderophores from a collection of purified isolates (60).

Prediction of protein structure and generation of Cys targets

None of the K. pneumoniae LGPs are crystallographically solved, so we used CLUSTALΩ to align the primary structures of the KpnFepAs and EcoFepA (1FEP). On that basis, we next predicted their tertiary structures using 1FEP as a template in the MODELLER function (27) of CHIMERA [UCSF; (28)]. In the resulting postulated structures of KpnIroN, KpnFepA_1658, KpnFepA_4984, and KpnFepA_2380, we selected sites in their surface loops that were analogous to sites that were successfully labeled in EcoFepA (29), substituting Cys for Ser, Thr, or Ala. For each KpnLGP, we selected five to six residues in loop regions and converted them to Cys using site-directed mutagenesis. After the generation of the Cys mutants, we experimentally determined their susceptibility to FM and from those data selected the best Cys mutant sensor for each protein.

Site-directed mutagenesis

For the site-directed Cys substitutions, we used the two-stage PCR-based QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis (Stratagene Cloning Systems, San Diego, CA) method. We started two separate PCR reactions with single primers (forward and reverse) for five reaction cycles, mixed these two reactions and ran another 18–20 reaction cycles for amplification. For mutagenesis PCR, we used PfuTurbo Cx HotStart DNA Polymerase (Agilent Technologies). We set two separate 50-µL reactions using 10× PfuTurbo Cx buffer, 0.1–0.2 µg DNA template, 0.2 mM dNTP mix, 100 ng/µL of primer (forward or reverse), and 0.5 µL DNA polymerase. We set thermal cycling at 95°C for 2 min, 94°C for 30 s, and 60°C for 1 min and extension at 68°C for 2 min/kb of template for five cycles. In the next step, we mixed a 25-µL mixture of two reactions in a separate PCR tube and added 1 µL of DNA polymerase to it and set this reaction in a thermal cycler for another 18–20 cycles using the same setup of denaturing, annealing, and extension conditions as before. We used 25 µL of this final product for further processing and added 1 µL of DpnI (New England Biolabs) in 25 µL PCR product and incubated it for 2 hours at 37°C. We directly used this final product for transformation and validated the construct by Sanger DNA sequencing.

Siderophore nutrition tests

This test is a qualitative microbiological assay to observe ferric siderophore transport (61) (e.g., FeEnt transport by KpnFepAs) in the presence of a non-utilizeable chelator in the media. E. coli does not transport apoferrichrome A so we used it as a non-specific chelator of Fe+3 in the media, to a final concentration of 100 µM. After growing the cells overnight in LB, we sub-cultured cells in nutrient broth for 5–6 hours at 37°C with appropriate antibiotics. We added the chelator, antibiotics and 100 µL of bacterial culture to 3 mL of molten NB top agar and plated the mixture in a six-well cell culture plate. After the agar solidified we placed a sterile disk in the middle of each well and added 5 µL of a 50 µM ferric siderophore solution to the disk. After overnight (9–10 hours) incubation at 37°C the results were seen as a halo of bacterial growth around the disk.

OM protein expression

We monitored the expression of KpnFepA transporters by SDS-PAGE analysis of OM fractions. We grew bacterial cells in LB at 37°C, sub-cultured (1:100) into 25 mL of MOPS media with appropriate antibiotics, and grew until the optical density at 600 nm (OD600 nm ) reached 1.0–1.5 (5–6 hours). We pelleted the bacteria at 5,000 × g for 10 min, resuspended the pellet in 2 mL of 50 mM Tris Cl, pH 7.5, containing trace amounts of DNAse and RNAse, and broke the cells by 3 passages through a French press at 14,000 psi. After centrifugation of the lysate at 3,000 × g for 10 min to remove cell debris, we centrifuged the supernatant at 14,000 × g in a microfuge for an hour to separate the cell envelope (pellet) and cytosol/periplasm (supernatant). We discarded the supernatant and resuspended the pellet in 500 µL of 50 mM tris Cl, pH 7.5, containing 1% sodium lauroyl sarcosinate (sarkosyl) and incubated this mixture for 30 min at room temperature with gentle shaking. After centrifugation at 14,000 × g in a microfuge for an hour we discarded the supernatant (inner membrane), respended the pellet (OM) in 200 µL of distilled water, and analyzed equal amounts of each OM fraction by SDS-PAGE, followed by Coomassie blue staining.

Fluorescent labeling of Cys mutants

For the fluoresceination of FepA proteins in E. coli or Klebsiella pneumoniae, we grew the bacteria in LB and sub-cultured (1:100) into MOPS media with appropriate antibiotics, until OD600 nm reached 1.0–1.5 (5–6 hours). We pelleted the bacteria at 7,000 × g for 10 min, resuspended them in labeling buffer (50 mM NaHPO4, pH 6.7), centrifuged again and resuspended the cells in labeling buffer. We added FM (E493 nm = 81,500 M−1 at pH 8.0) to 5 µM, incubated the cells for 15 min at 37°C with shaking and quenched the reaction with 130 mM 2-mercaptoethanol. We pelleted the FM-labeled bacteria at 7000 x g for 15 min, washed the pellet with PBS, and resuspended the pellet in PBS. We analyzed lysates of these cells by SDS-PAGE evaluated the fluorescence of the proteins in the resulting gels by fluorescent scans with a UVP imager.

Fluorescent spectroscopic assays of FeEnt transport

We observed FM-labeled E. coli or K. pneumoniae in an SLM AMINCO 8100 fluorescence spectrometer, upgraded with an OLIS operating system and operating system (OLIS SpectralWorks, OLIS Inc., Bogart, GA) that controlled its shutters, polarizers, and data collection. For FeEnt transport by individual KpnFepA mutants, we suspended 2 × 107 labeled cells in 2 mL of PBS in a quartz cuvette, with stirring at 37°C, added FeEnt at 100 s and monitored the fluorescence response to siderophore binding and transport. We performed these experiments in triplicate and plotted the average values of the resulting data using Grafit 6.0.12 (Erithacus Ltd., West Sussex, UK). For decoy sensor assays of iron transport, we incubated 2 × 107 sensor cells and 2 × 107 cells of test organisms (E. coli MG1655, K. pneumoniae Kp52.145, A. baumannii I7878/19606, P. aeruginosa PA01) together in 2 mL of PBS + 0.4% glucose at 37°C and incubated until fluorescence stabilized at 100 s. We then added FeEnt to 10 nM and monitored the time course of fluorescence emissions at 520 nm for 20–40 min, with stirring (17, 38).

Fluorescent spectroscopic binding assays

We used 2 × 107 cells in 2 mL of PBS in a 3 mL quartz cuvette for fluorescent spectroscopic binding assays. The temperature of the cuvette chamber was 25°C. For each KpnFepA protein we identified the most sensitive fluoresceinated Cys mutant construct by observing its initial fluorescence intensity and the extent of its quenching in response to the addition of FeEnt to 10 mM. For binding determinations we added sequentially increasing concentrations of a ferric siderophore to 2 × 107 cells in 2 mL of PBS, at 100-s intervals, until the fluorescence was maximally quenched and stabilized. We converted this fluorescence quenching pattern into a binding isotherm [concentration vs normalized fluorescence (F1/F0)] and fit the data to the “one site with background” equation of Grafit 6.0.12, that yielded KD values for each sensor with each ferric siderophore. For each data point, we performed the quenching determinations in triplicate and plotted the mean values with associated standard deviations.

Ferric siderophore uptake by hypervirulent K. pneumoniae strain hvKp1

We used four different sensors, each labeled with FM, to monitor the uptake of ferric siderophores, as previously described (17, 38). The test strains for ferric siderophore measurements were hvKp1 ΔentB for FeEnt and FeGent uptake, hvKp1 ΔiucA for FeAbn uptake, and hvKp1 Δirp2 for FeYbn uptake. For the uptake assay, we grew the test strains in iron-deficient MOPS media to OD600 nm of 1.8–2.0. After depositing 5 × 107 sensor cells in a sample cuvette containing PBS supplemented with 0.4% glucose, we added 107 cells of a test strain and monitored the fluorescence signal. We maintained the mixture at 37°C in the fluorimeter for 100 s, to allow the initial fluorescence to stabilize, then added the ferric siderophore of interest to 5 µM and monitored the ensuing fluorescence emissions for up to 3,000 s. For experiments in the presence of SCN, we supplemented the buffer with increasing concentrations of human SCN starting 0.005–0.5 µM and added ferric siderophores as described above.

Contributor Information

Phillip E. Klebba, Email: peklebba@ksu.edu.

Laurie E. Comstock, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, USA

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

The following material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.00024-24.

Figures S1 to S4.

ASM does not own the copyrights to Supplemental Material that may be linked to, or accessed through, an article. The authors have granted ASM a non-exclusive, world-wide license to publish the Supplemental Material files. Please contact the corresponding author directly for reuse.

REFERENCES

- 1. Holden VI, Bachman MA. 2015. Diverging roles of bacterial siderophores during infection. Metallomics 7:986–995. doi: 10.1039/C4MT00333K [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Palacios M, Broberg CA, Walker KA, Miller VL. 2017. A serendipitous mutation reveals the severe virulence defect of a Klebsiella pneumoniae fepB mutant. mSphere 2:e00341-17. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00341-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bailey DC, Drake EJ, Grant TD, Gulick AM. 2016. Structural and functional characterization of aerobactin synthetase Iuca from a hypervirulent pathotype of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Biochemistry 55:3559–35570. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Paczosa MK, Mecsas J. 2016. Klebsiella pneumoniae: going on the offense with a strong defense. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 80:629–661. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00078-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Navon-Venezia S, Kondratyeva K, Carattoli A. 2017. Klebsiella pneumoniae: a major worldwide source and shuttle for antibiotic resistance. FEMS Microbiol Rev 41:252–275. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fux013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Boucher HW, Talbot GH, Bradley JS, Edwards JE, Gilbert D, Rice LB, Scheld M, Spellberg B, Bartlett J. 2009. Bad bugs, no drugs: no ESKAPE! An update from the infectious diseases society of America. Clin Infect Dis 48:1–12. doi: 10.1086/595011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Weinberg ED. 1975. Nutritional immunity. host’s attempt to withold iron from microbial invaders. JAMA 231:39–41. doi: 10.1001/jama.231.1.39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Russo TA, Olson R, Fang C-T, Stoesser N, Miller M, MacDonald U, Hutson A, Barker JH, La Hoz RM, Johnson JR. 2018. Identification of biomarkers for differentiation of hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae from classical K. pneumoniae. J Clin Microbiol 56:e00776-18. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00776-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Miethke M, Marahiel MA. 2007. Siderophore-based iron acquisition and pathogen control. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 71:413–451. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00012-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Klebba PE, Newton SMC, Six DA, Kumar A, Yang T, Nairn BL, Munger C, Chakravorty S. 2021. Iron acquisition systems of Gram-negative bacterial pathogens define TonB-dependent pathways to novel antibiotics. Chem Rev 121:5193–5239. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c01005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Klebba PE. 2016. ROSET model of TonB action in Gram-negative bacterial iron acquisition. J Bacteriol 198:1013–1021. doi: 10.1128/JB.00823-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tsolis RM, Bäumler AJ, Heffron F, Stojiljkovic I. 1996. Contribution of TonB- and Feo-mediated iron uptake to growth of Salmonella typhimurium in the mouse. Infect Immun 64:4549–4556. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.11.4549-4556.1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pi H, Jones SA, Mercer LE, Meador JP, Caughron JE, Jordan L, Newton SM, Conway T, Klebba PE. 2012. Role of catecholate siderophores in Gram-negative bacterial colonization of the mouse gut. PLoS One 7:e50020. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schauer K, Rodionov DA, de Reuse H. 2008. New substrates for TonB-dependent transport: do we only see the 'tip of the iceberg'? Trends Biochem Sci 33:330–338. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rutz JM, Liu J, Lyons JA, Goranson J, Armstrong SK, McIntosh MA, Feix JB, Klebba PE. 1992. Formation of a gated channel by a ligand-specific transport protein in the bacterial outer membrane. Science 258:471–475. doi: 10.1126/science.1411544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yang T, Zou Y, Ng HL, Kumar A, Newton SM, Klebba PE. 2024. Specificity and mechanism of TonB-dependent ferric catecholate uptake by Fiu. Front Microbiol 15:1355253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chakravorty S, Shipelskiy Y, Kumar A, Majumdar A, Yang T, Nairn BL, Newton SM, Klebba PE. 2019. Universal fluorescent sensors of high-affinity iron transport, applied to ESKAPE pathogens. J Biol Chem 294:4682–4692. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.006921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nairn BL, Eliasson OS, Hyder DR, Long NJ, Majumdar A, Chakravorty S, McDonald P, Roy A, Newton SM, Klebba PE. 2017. Fluorescence high-throughput screening for inhibitors of TonB action. J Bacteriol 199:e00889-16. doi: 10.1128/JB.00889-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lery LMS, Frangeul L, Tomas A, Passet V, Almeida AS, Bialek-Davenet S, Barbe V, Bengoechea JA, Sansonetti P, Brisse S, Tournebize R. 2014. Comparative analysis of Klebsiella pneumoniae genomes identifies a phospholipase D family protein as a novel virulence factor. BMC Biol 12:41. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-12-41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Skyberg JA, Johnson TJ, Johnson JR, Clabots C, Logue CM, Nolan LK. 2006. Acquisition of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli plasmids by a commensal E. coli isolate enhances its abilities to kill chicken embryos, grow in human urine, and colonize the murine kidney. Infect Immun 74:6287–6292. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00363-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Baichoo N, Helmann JD. 2002. Recognition of DNA by Fur: a reinterpretation of the Fur box consensus sequence. J Bacteriol 184:5826–5832. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.21.5826-5832.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Baichoo N, Wang T, Ye R, Helmann JD. 2002. Global analysis of the Bacillus subtilis Fur regulon and the iron starvation stimulon. Mol Microbiol 45:1613–1629. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03113.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ma L, Kaserer W, Annamalai R, Scott DC, Jin B, Jiang X, Xiao Q, Maymani H, Massis LM, Ferreira LCS, Newton SMC, Klebba PE. 2007. Evidence of ball-and-chain transport of ferric enterobactin through FepA. J Biol Chem 282:397–406. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605333200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Klebba PE, McIntosh MA, Neilands JB. 1982. Kinetics of biosynthesis of iron-regulated membrane proteins in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 149:880–888. doi: 10.1128/jb.149.3.880-888.1982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ginalski K. 2006. Comparative modeling for protein structure prediction. Curr Opin Struct Biol 16:172–177. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stokes-Rees I, Sliz P. 2010. Protein structure determination by exhaustive search of protein data bank derived databases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107:21476–21481. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012095107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sali A, Blundell TL. 1993. Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J Mol Biol 234:779–815. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. 2004. UCSF Chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem 25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Smallwood CR, Jordan L, Trinh V, Schuerch DW, Gala A, Hanson M, Shipelskiy Y, Majumdar A, Newton SMC, Klebba PE. 2014. Concerted loop motion triggers induced fit of FepA to ferric enterobactin. J Gen Physiol 144:71–80. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201311159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Smallwood CR, Marco AG, Xiao Q, Trinh V, Newton SMC, Klebba PE. 2009. Fluoresceination of FepA during colicin B killing: effects of temperature, toxin and TonB. Mol Microbiol 72:1171–1180. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06715.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Buchanan SK, Smith BS, Venkatramani L, Xia D, Esser L, Palnitkar M, Chakraborty R, van der Helm D, Deisenhofer J. 1999. Crystal structure of the outer membrane active transporter FepA from Escherichia coli. Nat Struct Biol 6:56–63. doi: 10.1038/4931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Annamalai R, Jin B, Cao Z, Newton SMC, Klebba PE. 2004. Recognition of ferric catecholates by FepA. J Bacteriol 186:3578–3589. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.11.3578-3589.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cao Z, Qi Z, Sprencel C, Newton SM, Klebba PE. 2000. Aromatic components of two ferric enterobactin binding sites in Escherichia coli FepA. Mol Microbiol 37:1306–1317. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02093.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Majumdar A, Trinh V, Moore KJ, Smallwood CR, Kumar A, Yang T, Scott DC, Long NJ, Newton SM, Klebba PE. 2020. Conformational rearrangements in the N-domain of Escherichia coli FepA during ferric enterobactin transport. J Biol Chem 295:4974–4984. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA119.011850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Liu J, Rutz JM, Klebba PE, Feix JB. 1994. A site-directed spin-labeling study of ligand-induced conformational change in the ferric enterobactin receptor, FepA. Biochemistry 33:13274–13283. doi: 10.1021/bi00249a014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bentley AT, Klebba PE. 1988. Effect of lipopolysaccharide structure on reactivity of antiporin monoclonal antibodies with the bacterial cell surface. J Bacteriol 170:1063–1068. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.3.1063-1068.1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cao Z, Warfel P, Newton SMC, Klebba PE. 2003. Spectroscopic observations of ferric enterobactin transport. J Biol Chem 278:1022–1028. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210360200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kumar A, Yang T, Chakravorty S, Majumdar A, Nairn BL, Six DA, Marcondes Dos Santos N, Price SL, Lawrenz MB, Actis LA, Marques M, Russo TA, Newton SM, Klebba PE. 2022. Fluorescent sensors of siderophores produced by bacterial pathogens. J Biol Chem 298:101651. doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2022.101651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Newton SM, Trinh V, Pi H, Klebba PE. 2010. Direct measurements of the outer membrane stage of ferric enterobactin transport: postuptake binding. J Biol Chem 285:17488–17497. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.100206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ito A, Nishikawa T, Matsumoto S, Yoshizawa H, Sato T, Nakamura R, Tsuji M, Yamano Y. 2016. Siderophore cephalosporin cefiderocol utilizes ferric iron transporter systems for antibacterial activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:7396–7401. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01405-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wu JY, Srinivas P, Pogue JM. 2020. Cefiderocol: a novel agent for the management of multidrug-resistant Gram-negative organisms. Infect Dis Ther 9:17–40. doi: 10.1007/s40121-020-00286-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tomaras AP, Crandon JL, McPherson CJ, Banevicius MA, Finegan SM, Irvine RL, Brown MF, O’Donnell JP, Nicolau DP. 2013. Adaptation-based resistance to siderophore-conjugated antibacterial agents by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:4197–4207. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00629-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tomaras AP, Crandon JL, McPherson CJ, Nicolau DP. 2015. Potentiation of antibacterial activity of the MB-1 siderophore-monobactam conjugate using an efflux pump inhibitor. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:2439–2442. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04172-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Russo TA, Shon AS, Beanan JM, Olson R, MacDonald U, Pomakov AO, Visitacion MP. 2011. “Hypervirulent K. pneumoniae secretes more and more active iron-acquisition molecules than "classical" K. pneumoniae thereby enhancing its virulence”. PLoS One 6:e26734. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Shon AS, Bajwa RPS, Russo TA. 2013. Hypervirulent (hypermucoviscous) Klebsiella pneumoniae: a new and dangerous breed. Virulence 4:107–118. doi: 10.4161/viru.22718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Shon AS, Russo TA. 2012. Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae: the next superbug? Future Microbiol 7:669–671. doi: 10.2217/fmb.12.43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bullen JJ. 1981. The significance of iron in infection. Rev Infect Dis 3:1127–1138. doi: 10.1093/clinids/3.6.1127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bullen JJ, Rogers HJ, Spalding PB, Ward CG. 2005. Iron and infection: the heart of the matter. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 43:325–330. doi: 10.1016/j.femsim.2004.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Klebba PE, Newton SMC, Six DA, Kumar A, Yang T, Nairn BL, Munger C, Chakravorty S. 2021. Iron acquisition systems of Gram (-) bacterial pathogens define TonB-dependent pathways to novel antibiotics. Chem Rev 121:5193–5239. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c01005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Achenbach LA, Yang W. 1997. The Fur gene from Klebsiella pneumoniae: characterization, genomic organization and phylogenetic analysis. Gene 185:201–207. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(96)00642-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lin CT, Wu CC, Chen YS, Lai YC, Chi C, Lin JC, Chen Y, Peng HL. 2011. Fur regulation of the capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis and iron-acquisition systems in Klebsiella pneumoniae CG43. Microbiology (Reading) 157:419–429. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.044065-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Yuan L, Li X, Du L, Su K, Zhang J, Liu P, He Q, Zhang Z, Peng D, Shen L, Qiu J, Li Y. 2020. RcsAB and Fur coregulate the iron-acquisition system via entC in Klebsiella pneumoniae NTUH-K2044 in response to iron availability. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 10:282. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.00282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Holden VI, Wright MS, Houle S, Collingwood A, Dozois CM, Adams MD, Bachman MA. 2018. Iron acquisition and siderophore release by carbapenem-resistant sequence type 258 Klebsiella pneumoniae. mSphere 3:e00125-18. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00125-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Russo TA, Olson R, MacDonald U, Beanan J, Davidson BA. 2015. Aerobactin, but not yersiniabactin, salmochelin, or enterobactin, enables the growth/survival of hypervirulent (hypermucoviscous) Klebsiella pneumoniae ex vivo and in vivo. Infect Immun 83:3325–3333. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00430-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Blattner FR, Plunkett, 3rd G, Bloch CA, Perna NT, Burland V, Riley M, Collado-Vides J, Glasner JD, Rode CK, Mayhew GF, Gregor J, Davis NW, Kirkpatrick HA, Goeden MA, Rose DJ, Mau B, Shao Y. 1997. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science 277:1453–1462. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Chen YT, Chang HY, Lai YC, Pan CC, Tsai SF, Peng HL. 2004. Sequencing and analysis of the large virulence plasmid pLVPK of Klebsiella pneumoniae CG43. Gene 337:189–198. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bialek-Davenet S, Criscuolo A, Ailloud F, Passet V, Jones L, Delannoy-Vieillard AS, Garin B, Le Hello S, Arlet G, Nicolas-Chanoine MH, Decré D, Brisse S. 2014. Genomic definition of hypervirulent and multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae clonal groups. Emerg Infect Dis 20:1812–1820. doi: 10.3201/eid2011.140206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Groman NB. 1965. Factors in lysis and lysis inhibition by lambda bacteriophage. J Bacteriol 90:1563–1568. doi: 10.1128/jb.90.6.1563-1568.1965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Neidhardt FC, Bloch PL, Smith DF. 1974. Culture medium for enterobacteria. J Bacteriol 119:736–747. doi: 10.1128/jb.119.3.736-747.1974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Balhesteros H, Shipelskiy Y, Long NJ, Majumdar A, Katz BB, Santos NM, Leaden L, Newton SM, Marques MV, Klebba PE. 2017. TonB-dependent heme/hemoglobin utilization by Caulobacter crescentus HutA. J Bacteriol 199:e00723-16. doi: 10.1128/JB.00723-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Luckey M, Pollack JR, Wayne R, Ames BN, Neilands JB. 1972. Iron uptake in Salmonella typhimurium: utilization of exogenous siderochromes as iron carriers. J Bacteriol 111:731–738. doi: 10.1128/jb.111.3.731-738.1972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figures S1 to S4.