Abstract

Since HIV/AIDS was first recognized in 1981, an urgent need has existed for the development of novel therapeutic strategies to treat the disease. Due to the current antiretroviral therapy not being curative, human stem cell-based therapeutic intervention has emerged as an approach for its treatment. Genetically modified hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) possess the potential to self-renew, reconstitute the immune system with HIV-resistant cells, and thus control, or even eliminate, viral replication. However, HSCs may be difficult to isolate in sufficient number from HIV-infected individuals for transplantation and/or re-infusion of autologous HSCs preparations would also include some contaminating HIV-infected cells. Furthermore, since genetic modification of HSCs is not completely efficient, the risk of providing unprotected immune cells to become new targets for HIV to infect could contribute to continued immune system failure. Therefore, induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) should be considered a new potential source of cells to be engineered for HIV resistance and subsequently differentiated into clonal anti-HIV HSCs or hematopoietic progeny for transplant. In this article, we provide an overview of the current possible cellular therapies for treating HIV/AIDS.

Keywords: HIV, CCR5, Zinc finger nucleases, Hematopoietic stem cells, Embryonic stem cells, Induced pluripotent stem cells, CD4+ T cells

HIV cellular entry and coreceptor C–C chemokine receptor type 5 (CCR5)

Since 1984, it has been evident that the HIV virus enters cells through a fusion process in which the HIV viral envelope glycoprotein gp120 binds to its primary receptor CD4 and a coreceptor on the target cell surface. At present, C–C chemokine receptor type 5 (CCR5) and C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR-4) are believed to be the only HIV coreceptors of physiological significance. Based on coreceptor usage, a viral strain is named a R5 virus when it uses CCR5 alone as a coreceptor or X4 to describe viruses that use CXCR 4 [1, 2]. In 1996, it was shown that some individuals who remain uninfected with HIV despite multiple high-risk sexual exposures had inherited a homozygous defect in the CCR5 gene consisting of a 32-nucleotide deletion [3]. This natural mutation, named CCR5-Δ32, is mostly limited to the Caucasian population and it is found at frequencies of 2–5 % throughout Europe, the Middle East, and India. Individuals who are heterozygous for CCR5-Δ32 express lower levels of the coreceptor and have a slower progression to HIV infection [4] while in the homozygous CCR5-Δ32 genotype, individuals are resistant to HIV infection. Surprisingly, this defect has no pronounced deleterious effects in the affected individuals, making CCR5 an attractive cellular target for the development of drugs and gene therapy of AIDS [5, 6]. Thus, in 2007 the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the use of an antagonist of the CCR5 receptor, called Maraviroc [7] and it has demonstrated that inhibition of this coreceptor effectively inhibits HIV replication in a safe and persistent manner and results in a reduction in viral load [8].

A Berlin patient and Boston patients: the proof of principle for CCR5 disruption

Before 1987, when the first antiretroviral medication was introduced, the mortality rate of HIV patients was astounding. Based on positive experiences within the field of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) transplantation in children with immunodeficiency, this potential treatment option was considered a possibility to benefit the clinical course of HIV infection [9]. Transplantation of a disease-free HSC graft obtained from suitable healthy donors represented an attractive cell target for HIV therapy because the HSCs would be capable of producing all the cells involved in the pathogenesis (e.g., CD4+ T-cells, monocytes/macrophages). However, results of such clinical trials for HIV using HSCs were modest and were not successful in improving the course of infection [10–12]. These studies also have indicated that HSC transplantation without conditioning regimens (chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy) and without engineering the HSCs to contain any anti-HIV genes fails to produce sustained stable chimerism, immunologic reconstitution, and prevention of progression of HIV. Importantly, the potential efficacy of a permanent CCR5 disruption for treatment of HIV was demonstrated in 2007, when the first allogeneic transplant of HSCs from a donor specially selected to be homozygous for the CCR5-Δ32 deletion (CCR5-Δ32/Δ32) was performed in a 42-year-old HIV-positive man living in Berlin suffering from acute myeloid leukemia [13, 14]. The treatment of the “Berlin patient” to cure his leukemia included high-dose chemotherapy and total body irradiation, to both enhance the chemotherapeutic regimen and to eradicate his own HSCs and immune system, facilitating engraftment of the allogeneic CCR5-Δ32/Δ32 HSCs. A successful reconstitution of CD4+ T cells in this patient at the systemic level similar to the normal levels of healthy patients was observed. Although highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) was discontinued, HIV load could not be detected as determined by RNA and proviral DNA PCR assays in tissues during a 3.5-year follow-up period [15]. Recently, two male HIV patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma have no longer shown signs of the HIV type 1 (HIV-1) virus after receiving allogeneic heterozygous CCR5Δ32 HSCs transplant. At 3.5 years after receipt, the two ‘Boston patients’—nicknamed for the Massachusetts city where they were treated—do not show signs of detectable HIV DNA and HIV RNA in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), CD4+ T cells, and plasma after stopping their HAART. The loss of detectable HIV RNA and DNA in PBMCs correlated with full donor chimerism, recovery of CD4+ T cell counts and decreases in HIV-specific antibody levels. However, the virus could still be present in other tissues such as the brain or in the digestive system. Tissue sampling and carefully monitored interruption of antiretroviral therapy will be necessary to understand the extent and clinical significance of HIV-1 reservoir reduction after allogeneic HSC transplantation [16]. These clinical results suggest that the donor CCR5-Δ32 HSCs, and the HIV-resistant T cells derived from them, in vivo, were ultimately able to suppress or prevent HIV replication.

Targeting the CCR5 coreceptor

Due to the difficulty of identifying CCR5-Δ32 donors with suitable HLA compatibility and that a sufficient number of transplanted HSCs is difficult to obtain from cord blood samples, this procedure is not practical, in general, for treatment of HIV patients. Nonetheless, the experiences with the Berlin patient and Boston patients have increased interest in the development of strategies that could be used to recreate this CCR5-Δ32 phenotype through the use of a variety of gene modification tools that permanently disrupt expression of the CCR5 gene. Studies of Baltimore and colleagues [17] demonstrated that use of a small interfering RNA (siRNA) against CCR5 conferred a partial but substantial protection against R5-tropic HIV-1 virus infection of human peripheral blood T lymphocytes in vitro. However, residual infection of transduced cells was observed, explained, in part, by an incomplete inhibition. Since effective, permanent inhibition of HIV-1 infection by siRNA- or short hairpin RNAs (shRNA)-based strategies to knock-down CCR5 would require consistent expression, efforts have been devoted to achieve permanent CCR5 disruption via genome editing at the level of the chromosomal DNA. Over the last few years, new approaches for a site-specific genome editing have emerged. These technologies, including zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs) and transcriptor activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs), are based on the use of synthetic modular proteins composed of two functional domains, an engineered sequence-specific DNA-binding domain and a double-stranded (ds) DNA cleavage domain. These synthetic nucleases efficiently edit the genome by inducing targeted DNA ds-breaks (DSBs) that stimulate the cellular mechanism employed by cells to repair them, including non-homologous end joining (NHEJ). NHEJ is highly error prone, and frequently disrupts ZFN and TALEN-targeted open reading frames [18]. In 2008, June and colleagues showed that human CD4+ T cells, targeted at the CCR5 gene with ZFNs, suppressed HIV-1 replication. Transient expression of engineered ZFNs generated disruption of CCR5 alleles and a truncated or nonfunctional gene product that would fail to be expressed on the cell surface, in a manner analogous to the naturally occurring CCR5-Δ32 mutant allele. This modification provided robust, stable, and heritable protection against HIV-1 infection in vitro and in vivo in an immunodeficient NOD/SCID/gamma (C) (null) mouse model infected with an R5-tropic strain of HIV-1. This approach of ex vivo expansion and transfer of CCR5 ZFN-modified autologous CD4+ T cells in HIV patients has advanced into current clinical trials (Table 1) [19].

Table 1.

Anti-HIV gene therapeutics in clinical trials

| Clinical trial number | Sponsor/company | Name of the product | Delivery of genes | Target gene | Target cell/tissue | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT00569985 | City of Hope Medical Center |

Tat/Rev shRNA TAR decoy CCR5 ribozyme |

Lentiviral vector |

Viral (tat/rev mRNA) Viral (tat protein) Host (CCR5 mRNA |

Autologous CD34+ HPSCs |

Phase I, No recruiting |

| NCT01153646 | City of Hope Medical Center |

Tat/Rev shRNA TAR decoy CCR5 ribozyme |

Lentiviral vector |

Viral (tat/rev mRNA) Viral (tat protein) Host (CCR5 mRNA |

Autologous CD4+ T cells | Terminated |

| NCT00842634 | Sangamo Biosciences | CCR5 ZFN, SB-728-T | Adenoviral vector | Host (CCR5 DNA) | Autologous CD4+ T cells | Completed |

| NCT01044654 | Sangamo Biosciences | CCR5 ZFN, SB-728-T | Adenoviral vector | Host (CCR5 DNA) | Autologous CD4+ T cells |

Phase I Recruiting |

| NCT01543152 | Sangamo Biosciences | CCR5 ZFN, SB-728-T | Adenoviral vector | Host (CCR5 DNA) | Autologous CD4+ T cells |

Phase I/II Recruiting |

| NCT01252641 | Sangamo Biosciences | CCR5 ZFN, SB-728-T | Adenoviral vector | Host (CCR5 DNA) | Autologous CD4+ T cells |

Phase I/II No recruiting |

Currently, some cellular therapies designed to provide long-term resistance to HIV-1 infection are under review by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (Table 2). Two studies (NCT00569985 and NCT01153646; City of Hope Medical Center) are based on Anderson et al.’s anti-HIV combination lentiviral vector [35]. In the NCT01153646 study will be determined the safety and feasibility of lentivirus-transduced T cell immunotherapy in patients who have failed highly active anti-retrovirus therapy (HAART). After harvest and before reinfusion, these cells were transduced ex vivo with lentivirus expressing three RNA-based anti-HIV genes, tat/rev short hairpin RNA, TAR decoy, and CCR5 ribozyme. In NCT00569985, four AIDS patients with lymphoma were transplanted with autologous gene-modified CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells. The lentivirus vector induces three forms of anti-HIV RNA. All patients have been maintained on HAART during the treatment. Modified cells were successfully engrafted. There was no short-term toxicity, and persistent vector expression in multiple cell lineages was observed at low levels for up to 24 months, as was expression of the introduced small interfering RNA and ribozyme. These results demonstrated stable vector expression in human blood cells after transplantation of autologous gene-modified hematopoietic progenitor cells, supporting the development of an RNA-based cell therapy for HIV [71]. Sangamo BioSciences of Richmond, California, and its clinical partner, the University of Pennsylvania, are carrying out a multi-cohort study to evaluate: (1) the efficacy of an adenoviral-delivered CCR5 ZFN, known as SB-728-T, in autologous CD4+ T cells, (2) the safety and tolerability of a single infusion of genetically modified CD4+ T cells, and (3) the optimal conditions required to improve the engraftment and expansion of protected cells. The therapy involved removing CD4+ T cells from patients’ blood, treating the cells with SB-728-T to knock out the CCR5 gene, expanding the cells in the laboratory and then transplanting the HIV-resistant genetically modified cells back into the body. One clinical trial was completed (NCT00842634), one is in Phase I (NCT01044654), and two are in Phase I/II (NCT01543152 and NCT01252641). In these trials, they are studying viremic HIV patients who have never received HAART, patients who have multidrug HAART resistance, aviremic HIV patients who remain on HAART, and patients who have volunteered for scheduled treatment interruptions. Subjects will be followed every 3 months for 4 years. One of the major questions for these ongoing trials is how long the modified autologous T cells will survive, expand, and dominate circulating T-cell populations in the body, and how often this therapy will need to be administered

Transplantation of autologous hematopoietic stem/progenitors cells (HSPCs) modified with CCR5-specific ZFNs may enable reconstituting the immune system with a permanent supply of HIV-resistant progeny that could replace cells killed by HIV. In 2010, Cannon and colleagues reported an efficient disruption of CCR5 in isolated human CD34+ HSPCs using transient ZFN treatment. In vivo studies showed that humanized NOD SCID mice that received CCR5-Δ CD34+ HSPCs and challenged with an R5-tropic virus, maintained a normal CD4/CD8 ratio in blood samples. This study also showed a strong selection for CCR5Δ progeny that rapidly replaced cells depleted by the virus during acute infection and generated an HIV-resistant multi-lineage progeny that ultimately preserved human immune cells in multiple tissues and control of viral replication [20]. In 2011, Cathomen and coworkers have characterized the cleavage parameters for efficient TALEN-mediated genome editing in 293 T cells. Moreover, they performed a side-by-side comparison between engineered TALENs and well-characterized ZFNs at two endogenous human loci, CCR5 and IL2RG. Similar levels of CCR5 gene editing (~45 %) using ZFN and TALEN were observed. However, the TALENs used in this study were generally less cytotoxic than their ZFN counterparts, suggesting better specificity [21].

The recent discovery of the type II prokaryotic CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) system, that works as a mechanism to defend against viruses and plasmids via RNA-guided DNA cleavage [22], has been shown to have enormous potential for gene editing in a variety of hosts including human cells. This technology uses a nuclease, CRISPR-associated (Cas9), that complexes with short RNAs as guides (gRNAs) to induce cleavage of foreign DNA in a sequence-specific manner. Kim and colleagues showed that complexes of the Cas9 nuclease-RNAs efficiently induced up to 18 % mutation at the CCR5 locus in human cells [23]. Further studies demonstrating efficacy in humanized mouse models of HIV infection are required to validate TALENs and CRISPR/Cas9 nucleases for clinical applications.

Targeting the CXCR4 coreceptor

Once HIV infection is established, it may evolve to make use of the CXCR4 coreceptor (instead of the CCR5 coreceptor) for entry, supporting the need for therapies also targeted at CXCR4 [24]. Approaches to also target CXCR4 have been considered in recent years but there have been concerns due to its important function and broad pattern of expression. Although systemic inhibition of CXCR4 by molecules could be problematic [25, 26], a selective disruption of CXCR4 in specific cell types may be tolerable. Recently, Torbett and colleagues showed that ZFN-mediated disruption of CXCR4 provided resistance and a selective advantage to CD4+ T cells during HIV-1 infection in vitro and in humanized NOD scid IL2 receptor gamma chain knockout (NSG) mice ZFN editing of CXCR4 in human CD4+ T cells provided robust protection, cell selection, and a reduced number of cells available for viral replication evidenced, in part, by a decrease in cellular viral load during HIV-1 infection in vitro. In vivo studies using the humanized NSG model demonstrated protection and enrichment of ZFN-disrupted CXCR4 CD4+ T cells over time and a substantive decrease in viral load, in contrast to mice engrafted with unmodified CD4+ T cells [27]. In 2011, Doms and colleagues [28] performed a similar pre-clinical evaluation; upon challenge with R4-tropic virus, there was an initial period of protection followed by a shift over time to a predominant R5-tropic viral variant resulting in loss of both protection and the CD4+ T cells.

Combination of anti-HIV gene targets

Due to the high mutation rate of HIV, its ability to generate escape variants and the various tropisms of the virus, targeting one particular stage of the HIV-1 replication cycle alone may not be sufficient to protect cells from infection in the long term. This concern is consistent with prior monotherapy using antiretroviral drugs, which eventually selected for viral escape mutants [29, 30]. Therefore, similar to combination approaches with drugs, multiple anti-HIV genes inserted into a single gene therapy vector could potentially confer stronger protection from HIV infection in the long term while also preventing the generation of escape mutants. For a maximal therapeutic benefit, a dual knock down or dual disruption of CCR5 and CXCR4 may be necessary. In 2005, Anderson and Akkina [31] showed that CD34+ cell-derived macrophages expressing both CXCR4 and CCR5 shRNAs from a lentiviral vector exhibited marked down-regulation of both coreceptors and were resistant to both X4 and R5-tropic strains of HIV-1.

Various stages of the HIV life cycle including pre-entry, preintegration, and postintegration may be targeted by gene therapy to block viral infection and replication in transduced cells. In 2009, Bauer and colleagues described a combination lentiviral vector that encodes three anti-HIV genes functioning at separate stages of the viral life cycle. They used a CCR5 shRNA and a human/rhesus macaque chimeric TRIM5α, which inhibit HIV-1 infection at the postentry/preintegration stage by disrupting the uncoating of the viral capsid upon entering the cytoplasm [32]; and a transactivation response element (TAR) decoy, which has been previously described to inhibit transactivation of proviral transcription [33] by mimicking the structure of the viral TAR. The TAR decoy is able to bind the viral Tat protein and sequester it away from its normal action of aiding efficient proviral HIV transcription. This combination anti-HIV lentiviral vector, when evaluated in vitro in HIV-1-susceptible cultured cells and primary CD34+ HSPC-derived macrophages, displayed stable and substantial viral protection from R5-, X4-, and dual-tropic strains, R5X4. After long-term repeated HIV challenge of combination vector-transduced cells, no rise in HIV replication could be detected; confirming a lack of HIV-1 replication, there was a lack of mutant escape virus formation and an efficient inhibition of HIV-1 integration and proviral formation [34]. Recently, Anderson and colleagues performed a preclinical evaluation of this combination anti-HIV lentiviral vector in human cord blood CD34+ HSCs injected into humanized NOD-RAG1−/−IL2−/− knockout mice. Even though the mice engrafted with anti-HIV vector-transduced cells did not display a decrease in HIV-1 plasma viremia over the course of infection, maintenance of normal levels of human CD4+ T cell, derived from anti-HIV gene-modified HSPCs, was observed in mice infected with either R5- or X4-tropic strains of HIV-1 [35]. This approach is currently in clinical trial (Table 1).

Human-induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSCs) as a potential source of HSCs

As mentioned, transplantation of either autologous or histocompatible HSCs, genetically modified for resistance to HIV, would, in principle, establish an HIV-resistant blood system. However, there are strong reasons to also consider other potential sources of HSCs. HSCs can be extracted from bone marrow, cytokine-mobilized peripheral blood, or umbilical cord blood; however, HSCs may be difficult to isolate in sufficient number from HIV-1-infected individuals for transplantation. HIV-infected patients, particularly at later stages of the disease, frequently exhibit bone marrow suppression with defective hematopoietic activity of their HSPCs [36, 37]; consequently, the autologous HSCs, once genetically modified and transplanted, may be inefficient in reconstitution. Additionally, since genetic modification of HSCs is not 100 % efficient, transplantation of treated HSCs will, in fact, reflect a mixture of HSCs, some of that are HIV resistant and others that are not. Therefore, it is possible that any hematopoietic progeny derived from unmodified HSCs would be susceptible to infection when challenged by residual HIV in vivo. Finally, although work by us [38] and others demonstrated an absence of HIV infection in CD34+ hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells isolated from HIV-infected individuals [38–40], it is possible that re-infusion of autologous CD34+-enriched cell preparations would also include some contaminating HIV-infected cells [41, 42]. Consequently, it has been proposed that human-induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived HSCs would offer an alternative source of abundant transplantable cells.

It is possible to induce pluripotency in human somatic cells through the ectopic expression of a small number of transcription factors; these cells, named “pluripotent cells”, can differentiate into all three cell germ layers. The initial landmark discovery in this area was reported by Takahashi and Yamanaka [43] in 2006 when they demonstrated that overexpression of the transcription factors OCT4, SOX2, KLF4 and C-MYC in mouse fibroblast cells resulted in the generation of embryonic stem cell (ESC)-like cells, termed iPSC. Subsequently, in 2007, Yamanaka and colleagues successfully applied the same technique they used in mice to obtain human iPSC from human dermal fibroblasts [44]. In the same year, Thomson and colleagues discovered a new combination of factors (OCT4, SOX2, NANOG and LIN28) sufficient for the generation of human iPSC [45]. Now it is evident that the combination of a small number of specific transcription factors can “reprogram” fully differentiated human somatic cells into human iPSCs. Like other pluripotent stem cells, iPSCs in vitro can be directed to terminally differentiated cell types by exposure to a combination of growth factors and cell culture conditions. These cells have the potential, in principle, to generate all tissues in the body including blood cells, stomach cells, liver cells, keratinocytes, melanocytes, pancreatic β cells, and neural progenitors [46–51]. Autologous iPSC-derived cells may eventually be used for therapeutic purposes due to there being no immunological incompatibility between patient and donor cells.

In 2007, Jaenisch and colleagues showed that a humanized knock-in mouse model of sickle cell can be rescued after transplantation with modified hematopoietic progenitors obtained in vitro from autologous mouse iPSC derived from tail-tip fibroblasts [52]. The general therapeutic strategy involved reprogramming of mutant donor fibroblasts into iPSCs, repair of the sickle hemoglobin allele by genome editing, in vitro differentiation of repaired iPSC into hematopoietic stem/progenitors (which involved transduction of Hoxb4), and finally transplanting a clonal population of these modified cells into affected donor mice after irradiation.

Human HSCs are presently defined functionally by sustained multilineage in vivo hematopoietic system reconstitution upon transplantation in immunodeficient mouse models. Despite significant effort, even though the directed differentiation of human ESC and iPSCs has yielded various blood cell types (e.g., including myeloid/erythroid progenitors, neutrophils, dendritic cells, natural killer (NK) cells [53], and T cells [54, 55] ), human ESC and iPSCs-derived HSCs have not yet been produced. In the majority of transplantation studies performed with hESC- or hiPSC-derived HSCs in vivo, no chimerism was detected; with hematologic reconstitution absent or only present at low frequencies for a short period of time after transplantation [56, 57]. These studies showed that hESC- or hiPSC-derived HSCs were either not generated or had limited proliferative, migratory capacity, and/or differentiation ability in vivo.

hiPSCs as a potential source of hematopoietic progeny

Although the generation of hESC/iPSC-derived HSCs remains a significant, outstanding challenge for therapeutic application, it has already been demonstrated that anti-HIV-modified hiPSCs can give rise to HIV-resistant hematopoietic progeny. Recently, Chen and colleagues showed the generation of CD34+ cells from hiPSCs and hESCs with the CCR5 gene disrupted using specific ZFN. These hiPSCs and hESCs-modified cells retained pluripotent characteristics after the gene editing and had the potential to be differentiated into both CD34+ cells and blood cell types in vitro [58]. In 2011, Anderson and colleagues generated HIV-1-resistant and functional macrophages from hematopoietic stem cell-derived iPSCs. Human cord blood CD34+ HSC were transduced with four reprogramming factors and a lentiviral vector containing a combination of anti-HIV genes including a CCR5 short hairpin RNA (shRNA) and a chimeric human/rhesus TRIM5α molecule. Anti-HIV iPSCs were successfully directly differentiated into functional CD133+ hematopoietic progenitors, which upon further differentiation were able to differentiate into phenotypically normal, functional macrophages. Anti-HIV iPSC-derived macrophages were resistant to infection by either R5-tropic or dual tropic strains of HIV-1 [59], thus showing the ability of modified iPSCs to develop into HIV-1-resistant immune cells and their potential for use as novel cellular therapeutics. Various reports have described the derivation of T-cells from human ESCs/iPSCs [54, 55, 60, 61]. Thus, it may be possible to generate patient-specific iPSCs from HIV-infected individuals, genetically modify them to render their progeny resistant to HIV infection (e.g., via CCR5 disruption), and subsequently derive T cells for transplantation back into the original patients. In another vein, patient-specific NK cells, with activity against HIV-infected cells, may be derived and used therapeutically [53].

Safety issues

It will be crucial for the future use of nucleases in clinical applications to identify the factors that determine target specificity and improve methods to detect off-target effects that could be deleterious [62]. A major off-target locus of the CCR5-specific ZFNs and TALEs has been identified in CCR2, which shares a high degree of sequence identity with the CCR5. June and colleagues showed that under conditions where CCR5 was modified at 36 % efficiency on CD4+ T cells after ZFN treatment, 5.39 % of CCR2 was modified [19]. Likewise, analysis of potential off-target sites in cultured human K562 cells revealed that the use of ZFN-224 induced mutagenesis in some loci, including CCR2 gene and in a promoter of the malignancy-associated BTBD10 gene [63, 64]. So far, Cathomen and colleagues showed that CCR5-specific TALEN induced mutations at 17 % of CCR5 alleles and at only 1 % of CCR2 alleles. In contrast, activity of the CCR5-specific ZFN was almost comparable at the two loci, with mutation frequencies of 14 % at CCR5 and 11 % at CCR [21]. Off-target effect of CCR5-specific CRISPR/Cas9 system has not been detected in CCR2 alleles [23]. However, further studies are required to validate these technologies. This is a potential advantage for iPSC-derived HSCs or T cells in that it will be possible to completely interrogate the whole exome or even the whole genome for any potential off-target effects induced by these endonucleases.

Even though reprogramming of human somatic cells into iPSC has been achieved, before the cells can be used in the clinic, a number of safety issues need to be considered. Traditional approaches to deriving hiPSCs require the use of conventional vectors, retrovirus and lentivirus, which integrate randomly throughout the host genome and can disrupt or perturb the transcription of host genes or can activate a proto-oncogene causing malignant transformation of a clonal cell population [65]. In addition, some of the reprogramming genes are known proto-oncogenes where incomplete silencing of these transgenes may result in unknown adverse effects. These challenges have been largely circumvented by the development of non-integrating viral techniques, excisional techniques, mRNA transfection, miRNAs, and recombinant membrane-crossing proteins developed for reprogramming [66]. Furthermore, genetic screening for analysis of genomic stability and integrity of hiPSCs should become a standard procedure to ensure hiPSC safety before clinical use. Genome analyses of hiPSC lines showed that hiPSCs may acquire genetic aberrations and copy number variations during the reprogramming phase and/or first passages of culture [67–69]. Also, the interest in induction and expansion of iPSCs under current good manufacturing practice (cGMP) conditions has accelerated the development of cGMP-compliant iPSC protocols, enabling many laboratories to produce iPSCs as part of a clinical manufacturing process [70]. In the future, iPSC-derived CD4+ T cells and/or iPSC-derived HSC transplantation may offer several advantages compared to the current available treatments (Fig. 1; Table 2).

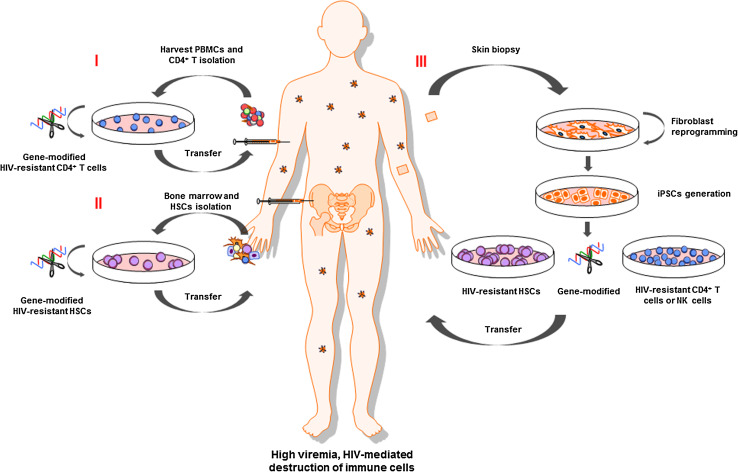

Fig. 1.

Reconstitution of HIV-resistant immune system in humans. I Isolated CD4+ T cells from blood or II isolated hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) from bone marrow are modified in vitro using nucleases to confer anti-HIV resistance (e.g., disruption of the CCR5 gene). Transplantation of modified HSCs may provide a permanent supply of HIV-resistant progeny. III Autologous iPSC-derived cells may eventually be used for therapeutic purposes due to immunological compatibility, the ability to edit the genome through the use of nucleases, and the opportunity to repeatedly differentiate iPSC into CD4+ T cells, NK cells, or HSCs for continued therapy

Table 2.

Comparison of potential strategies for anti-HIV cell transplantation

| CD4+ T cells | HSCsb | CD4+ T cells, NK cells, and HSCs derived from iPSCsd |

|---|---|---|

| Limited source | Limited source | Unlimited source of CD4+ T, NK cells, and HSCs |

| Contaminated with T cells (GVHDc) | Grafts devoid of T cell (no GVHD) | |

| Always HLAa-matched graft | HLA-matched grafts dependent on donor registries | Always HLA-matched graft |

| Autologous cells are not always available | Autologous cells are not always available | Autologous cells always available |

| Autologous cells could be HIV contaminated | Autologous cells could be contaminated with HIV-infected cells | Autologous cells are HIV free |

| Genetic modification by viral vector and/or nucleases | Genetic modification by viral vector and/or nucleases | Genetic modification by viral vector and/or nucleases |

| Not known how long the modified autologous T cells will survive | Transplantation is a risky procedure requiring irradiation and ablation of the immune system | Long-term repopulating iPSC-derived HSCs have not been generated |

| Will perhaps require frequent cell administration | Safety has not been demonstrated |

a HLA Human leukocyte antigen

b HSCs Hematopoietic stem cells

c GVHD Graft-versus-host disease

dInduced pluripotent stem cells

Concluding remarks and future perspectives

The progress in HIV therapy over the past years has been tremendous. However, under the current antiretroviral therapy, HIV infection is well suppressed, but not eradicated. The ability to generate escape variants and the tropisms of the virus explains why a therapeutic intervention is unlikely to be curative if based on the sole use of drugs that block viral replication. As HIV continues to be a global health problem, novel therapies have to be developed. The cases of successful allogeneic CCR5-Δ32 HSC transplantations in patients with HIV infection has initiated a run towards the development of new gene therapy strategies against this disease. Technologies are available not only to both knock down and knock out CCR5 expression alone, but also other genes involved in the different stages of the viral life cycle. The door is now open to attempt the reconstitution of the immune systems of HIV-infected individuals with virus-resistant cells. Advantages of HIV gene therapy using HSCs include the possibility of a one-time treatment, controlled or constitutive anti-HIV gene expression, and long-term viral inhibition upon HSC transplantation. If a pure population of anti-HIV gene-expressing HSCs could be transplanted into patients, a complete suppression of HIV replication could be accomplished. One promising method to achieve this goal is to use clonal anti-HIV HSCs or hematopoietic progeny generated from iPSCs. Each anti-HIV iPSCs line can be fully characterized for its safety and analysis of the integration site of the therapeutic transgenes. Although the current failure to derive HSCs from hiPSCs remains a significant barrier, it is possible that other iPSC-derived cell types may be useful therapeutically in HIV-infected individuals.

References

- 1.Dean M, et al. Genetic restriction of HIV-1 infection and progression to AIDS by a deletion allele of the CKR5 structural gene. Hemophilia Growth and Development Study, Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study, Multicenter Hemophilia Cohort Study, San Francisco City Cohort, ALIVE Study. Science. 1996;273(5283):1856–1862. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5283.1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berger EA, et al. A new classification for HIV-1. Nature. 1998;391(6664):240. doi: 10.1038/34571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu R, et al. Homozygous defect in HIV-1 coreceptor accounts for resistance of some multiply-exposed individuals to HIV-1 infection. Cell. 1996;86(3):367–377. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martinson JJ, et al. Global distribution of the CCR5 gene 32-basepair deletion. Nat Genet. 1997;16(1):100–103. doi: 10.1038/ng0597-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ji C, et al. Novel CCR5 monoclonal antibodies with potent and broad-spectrum anti-HIV activities. Antiviral Res. 2007;74(2):125–137. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olson WC, Jacobson JM. CCR5 monoclonal antibodies for HIV-1 therapy. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2009;4(2):104–111. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e3283224015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Westby M, van der Ryst E. CCR5 antagonists: host-targeted antiviral agents for the treatment of HIV infection, 4 years on. Antivir Chem Chemother. 2010;20(5):179–192. doi: 10.3851/IMP1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gilliam BL, Riedel DJ, Redfield RR. Clinical use of CCR5 inhibitors in HIV and beyond. J Transl Med. 2011;9(Suppl 1):S9. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-9-S1-S9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Masur H. The acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Dis Mon. 1983;30(1):1–48. doi: 10.1016/0011-5029(83)90005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bardini G, et al. HIV infection and bone-marrow transplantation. Lancet. 1991;337(8750):1163–1164. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)92831-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aboulafia DM, Mitsuyasu RT, Miles SA. Syngeneic bone-marrow transplantation and failure to eradicate HIV. Aids. 1991;5(3):344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giri N, Vowels MR, Ziegler JB. Failure of allogeneic bone marrow transplantation to benefit HIV infection. J Paediatr Child Health. 1992;28(4):331–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.1992.tb02681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hutter G, et al. Long-term control of HIV by CCR5 Delta32/Delta32 stem-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(7):692–698. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hutter G, Thiel E. Allogeneic transplantation of CCR5-deficient progenitor cells in a patient with HIV infection: an update after 3 years and the search for patient no. 2. Aids. 2011;25(2):273–274. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328340fe28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allers K, et al. Evidence for the cure of HIV infection by CCR5Delta32/Delta32 stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2011;117(10):2791–2799. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-09-309591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henrich TJ, et al. Long-term reduction in peripheral blood HIV type 1 reservoirs following reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic stem cell transplantation. J Infect Dis. 2013;207(11):1694–1702. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qin XF, et al. Inhibiting HIV-1 infection in human T cells by lentiviral-mediated delivery of small interfering RNA against CCR5. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(1):183–188. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232688199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gaj T, Gersbach CA, Barbas CF., 3rd ZFN, TALEN, and CRISPR/Cas-based methods for genome engineering. Trends Biotechnol. 2013;31(7):397–405. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perez EE, et al. Establishment of HIV-1 resistance in CD4 + T cells by genome editing using zinc-finger nucleases. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26(7):808–816. doi: 10.1038/nbt1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holt N, et al. Human hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells modified by zinc-finger nucleases targeted to CCR5 control HIV-1 in vivo. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28(8):839–847. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mussolino C, et al. A novel TALE nuclease scaffold enables high genome editing activity in combination with low toxicity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(21):9283–9293. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wiedenheft B, Sternberg SH, Doudna JA. RNA-guided genetic silencing systems in bacteria and archaea. Nature. 2012;482(7385):331–338. doi: 10.1038/nature10886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cho SW, et al. Targeted genome engineering in human cells with the Cas9 RNA-guided endonuclease. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31(3):230–232. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tilton JC, et al. A maraviroc-resistant HIV-1 with narrow cross-resistance to other CCR5 antagonists depends on both N-terminal and extracellular loop domains of drug-bound CCR5. J Virol. 2010;84(20):10863–10876. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01109-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hendrix CW, et al. Pharmacokinetics and safety of AMD-3100, a novel antagonist of the CXCR-4 chemokine receptor, in human volunteers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44(6):1667–1673. doi: 10.1128/AAC.44.6.1667-1673.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hendrix CW, et al. Safety, pharmacokinetics, and antiviral activity of AMD3100, a selective CXCR4 receptor inhibitor, in HIV-1 infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;37(2):1253–1262. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000137371.80695.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yuan J, et al. Zinc-finger nuclease editing of human cxcr4 promotes HIV-1 CD4(+) T cell resistance and enrichment. Mol Ther. 2012;20(4):849–859. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilen CB, et al. Engineering HIV-resistant human CD4 + T cells with CXCR4-specific zinc-finger nucleases. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7(4):e1002020. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martinez-Picado J, et al. Antiretroviral resistance during successful therapy of HIV type 1 infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(20):10948–10953. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.20.10948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blanco JL, et al. HIV-1 integrase inhibitor resistance and its clinical implications. J Infect Dis. 2011;203(9):1204–1214. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anderson J, Akkina R. CXCR4 and CCR5 shRNA transgenic CD34 + cell derived macrophages are functionally normal and resist HIV-1 infection. Retrovirology. 2005;2:53. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-2-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stremlau M, et al. The cytoplasmic body component TRIM5alpha restricts HIV-1 infection in Old World monkeys. Nature. 2004;427(6977):848–853. doi: 10.1038/nature02343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Michienzi A, et al. A nucleolar TAR decoy inhibitor of HIV-1 replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(22):14047–14052. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212229599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anderson JS, et al. Preintegration HIV-1 inhibition by a combination lentiviral vector containing a chimeric TRIM5 alpha protein, a CCR5 shRNA, and a TAR decoy. Mol Ther. 2009;17(12):2103–2114. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walker JE, et al. Generation of an HIV-1-resistant immune system with CD34(+) hematopoietic stem cells transduced with a triple-combination anti-HIV lentiviral vector. J Virol. 2012;86(10):5719–5729. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06300-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zauli G, et al. Impaired in vitro growth of purified (CD34+) hematopoietic progenitors in human immunodeficiency virus-1 seropositive thrombocytopenic individuals. Blood. 1992;79(10):2680–2687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cen D, et al. Effect of different human immunodeficiency virus type-1 (HIV-1) isolates on long-term bone marrow haemopoiesis. Br J Haematol. 1993;85(3):596–602. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1993.tb03353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davis BR, et al. Absent or rare human immunodeficiency virus infection of bone marrow stem/progenitor cells in vivo. J Virol. 1991;65(4):1985–1990. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.4.1985-1990.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Josefsson L, et al. Hematopoietic precursor cells isolated from patients on long-term suppressive HIV therapy did not contain HIV-1 DNA. J Infect Dis. 2012;206(1):28–34. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Durand CM, et al. HIV-1 DNA is detected in bone marrow populations containing CD4+ T cells but is not found in purified CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells in most patients on antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis. 2012;205(6):1014–1018. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stanley SK, et al. CD34+ bone marrow cells are infected with HIV in a subset of seropositive individuals. J Immunol. 1992;149(2):689–697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carter CC, et al. HIV-1 infects multipotent progenitor cells causing cell death and establishing latent cellular reservoirs. Nat Med. 2010;16(4):446–451. doi: 10.1038/nm.2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126(4):663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takahashi K, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131(5):861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu J, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;318(5858):1917–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Murry CE, Keller G. Differentiation of embryonic stem cells to clinically relevant populations: lessons from embryonic development. Cell. 2008;132(4):661–680. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Song Z, et al. Efficient generation of hepatocyte-like cells from human induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Res. 2009;19(11):1233–1242. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nizzardo M, et al. Human motor neuron generation from embryonic stem cells and induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010;67(22):3837–3847. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0463-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Green MD, et al. Generation of anterior foregut endoderm from human embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29(3):267–272. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Spence JR, et al. Directed differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells into intestinal tissue in vitro. Nature. 2011;470(7332):105–109. doi: 10.1038/nature09691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Swistowski A, et al. Efficient generation of functional dopaminergic neurons from human induced pluripotent stem cells under defined conditions. Stem Cells. 2010;28(10):1893–1904. doi: 10.1002/stem.499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hanna J, et al. Treatment of sickle cell anemia mouse model with iPS cells generated from autologous skin. Science. 2007;318(5858):1920–1923. doi: 10.1126/science.1152092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ni Z, et al. Human pluripotent stem cells produce natural killer cells that mediate anti-HIV-1 activity by utilizing diverse cellular mechanisms. J Virol. 2011;85(1):43–50. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01774-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Timmermans F, et al. Generation of T cells from human embryonic stem cell-derived hematopoietic zones. J Immunol. 2009;182(11):6879–6888. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kennedy M, et al. T lymphocyte potential marks the emergence of definitive hematopoietic progenitors in human pluripotent stem cell differentiation cultures. Cell Rep. 2012;2(6):1722–1735. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Risueno RM, et al. Inability of human induced pluripotent stem cell-hematopoietic derivatives to down regulate microRNAs in vivo reveals a block in xenograft hematopoietic regeneration. Stem Cells. 2012;30(2):131–139. doi: 10.1002/stem.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Doulatov S, et al. Hematopoiesis: a human perspective. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10(2):120–136. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yao Y, et al. Generation of CD34+ cells from CCR5-disrupted human embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells. Hum Gene Ther. 2012;23(2):238–242. doi: 10.1089/hum.2011.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kambal A, et al. Generation of HIV-1 resistant and functional macrophages from hematopoietic stem cell-derived induced pluripotent stem cells. Mol Ther. 2011;19(3):584–593. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vizcardo R, et al. Regeneration of human tumor antigen-specific T cells from iPSCs derived from mature CD8(+) T Cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12(1):31–36. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nishimura T, et al. Generation of rejuvenated antigen-specific T cells by reprogramming to pluripotency and redifferentiation. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12(1):114–126. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Szczepek M, et al. Structure-based redesign of the dimerization interface reduces the toxicity of zinc-finger nucleases. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25(7):786–793. doi: 10.1038/nbt1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pattanayak V, et al. Revealing off-target cleavage specificities of zinc-finger nucleases by in vitro selection. Nat Methods. 2011;8(9):765–770. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gabriel R, et al. An unbiased genome-wide analysis of zinc-finger nuclease specificity. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29(9):816–823. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Naldini L. Ex vivo gene transfer and correction for cell-based therapies. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12(5):301–315. doi: 10.1038/nrg2985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kiskinis E, Eggan K. Progress toward the clinical application of patient-specific pluripotent stem cells. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(1):51–59. doi: 10.1172/JCI40553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Laurent LC, et al. Dynamic changes in the copy number of pluripotency and cell proliferation genes in human ESCs and iPSCs during reprogramming and time in culture. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8(1):106–118. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hussein SM, et al. Copy number variation and selection during reprogramming to pluripotency. Nature. 2011;471(7336):58–62. doi: 10.1038/nature09871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gore A, et al. Somatic coding mutations in human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2011;471(7336):63–67. doi: 10.1038/nature09805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ausubel LJ, Lopez PM, Couture LA. GMP scale-up and banking of pluripotent stem cells for cellular therapy applications. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;767:147–159. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-201-4_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.DiGiusto DL, et al. RNA-based gene therapy for HIV with lentiviral vector-modified CD34(+) cells in patients undergoing transplantation for AIDS-related lymphoma. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2(36):36ra43. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]