Abstract

The lymphatic vasculature is essential for fluid homeostasis and transport of immune cells, inflammatory molecules, and dietary lipids. It is composed of a hierarchical network of blind-ended lymphatic capillaries and collecting lymphatic vessels, both lined by lymphatic endothelial cells (LECs). The low hydrostatic pressure in lymphatic capillaries, their loose intercellular junctions, and attachment to the surrounding extracellular matrix (ECM) permit passage of extravasated blood plasma from the interstitium into the lumen of the lymphatic capillaries. It is generally thought that interstitial fluid accumulation leads to a swelling of the ECM, to which the LECs of lymphatic capillaries adhere, for example via anchoring filaments. As a result, LECs are pulled away from the vascular lumen, the junctions open, and fluid enters the lymphatic vasculature. The collecting lymphatic vessels then gather the plasma fluid from the capillaries and carry it through the lymph nodes to the blood circulation. The collecting vessels contain intraluminal bicuspid valves that prevent fluid backflow, and are embraced by smooth muscle cells that contribute to fluid transport. Although the lymphatic vessels are regular subject to mechanical strain, our knowledge of its influence on lymphatic development and pathologies is scarce. Here, we discuss the mechanical forces and molecular mechanisms regulating lymphatic vascular growth and maturation in the developing mouse embryo. We also consider how the lymphatic vasculature might be affected by similar mechanomechanisms in two pathological processes, namely cancer cell dissemination and secondary lymphedema.

Keywords: Lymphatic vessel, Mechanotransduction, Stretch, Extracellular matrix (ECM), Lymphedema, Integrin, VEGFR3, Endothelial cell

Introduction

On average, the human body consists of ~60 % fluid of which two-thirds (~40 %) is stored intracellularly. The remaining one-third (~20 % of human body mass) is mostly found between cells of a tissue, i.e., within the interstitium, whereas only a small part of the extracellular fluid is transported in specialized conduits termed vessels [1]. Two main types of vessels exist in vertebrates: blood vessels, which include capillaries as well as small to large caliber arteries and veins, and lymphatic vessels [2]. The arterial vasculature provides tissues with the necessary oxygen and nutrients to support biochemical reactions, while the venous vasculature collects waste products, carbon dioxide, and water from the tissue [3]. In order to accomplish the exchange of solutes between blood and tissues, most arterial capillaries are permeable, and plasma fluid extravasates from their lumen towards the extracellular or interstitial spaces of a given tissue [4]. This leakage is because arterial capillaries have a higher hydrostatic than oncotic or colloid osmotic pressure, and the net fluid pressure inside arterial capillaries is higher than the net interstitial fluid pressure of the surrounding tissue [5]. On the contrary, venous capillaries mostly reabsorb the extravasated plasma or interstitial fluid from the tissue, since the oncotic pressure of these blood vessels exceeds the venous hydrostatic pressure, and the net interstitial fluid pressure is higher than the net pressure inside the venous capillaries [6]. However, these two opposite fluid flows do not fully balance each other out, so that a small amount of plasma fluid remains within the interstitium. In general, the hydrostatic pressure of lymphatic capillaries is very low when compared to the blood pressure, and thus it is the lymphatic vasculature that finally drains the remaining plasma fluid from the interstitium [5, 7–9]. The plasma fluid is subsequently transported via collecting lymphatic vessels, is filtered and gathered by numerous lymph nodes, and is ultimately brought back to the blood circulation at the left and right subclavian veins [2, 10]. Besides fluid drainage, the lymphatic vasculature also acts as a buffering system for sodium accumulation to counteract salt-induced hypertension [11].

Some vascular beds, such as the blood–brain and blood–retinal barriers, do not passively exchange fluid due to low vascular permeability, but tightly control transvascular fluid passage via aquaporins [12, 13]. Consistent with a requirement of fluid extravasation for lymphatic vascular growth (described below), brain and retina are largely characterized by the absence of lymphatic vessels [12, 13]. In contrast, although pancreatic islets are irrigated by a highly permeable fenestrated endothelium, lymphatic vessels are absent from the core of the islet [14, 15]. A possible explanation for this unexpected finding might be the numerous intercellular junctions between the endocrine pancreatic cells, the islet capsule composed of ECM and glial cells, and a network of small intercellular canaliculi between the endocrine cells that might drain plasma fluid and transport it to the islet margin where lymphatic vessels are located [16–18].

Under inflammatory conditions, leukocyte infiltration results in the release of a variety of cytokines that increase vascular permeability and thus lead to tissue swelling [19]. However, leukocytes also secrete lymphangiogenic factors to promote growth of the lymphatic vasculature that finally drains the tissue and resolves its swelling [20–22]. To date, the role of the amount of interstitial fluid in triggering lymphatic growth during inflammation remains elusive.

Drainage of plasma fluid from the interstitial spaces

Although all lymphatic vessels are lined by lymphatic endothelial cells (LECs), they morphologically differ depending on their role in either facilitating fluid drainage or in promoting long-distance trafficking of fluid [23, 24]. The lymphatic capillaries are specialized in the uptake of interstitial plasma fluid, inflammatory molecules, dietary lipids, and immune cells [25]. They are blind-ended, and their LECs present an oak leaf shape and discontinuous button-like junctions, which overlap at the cell edges [26]. They are covered by a discontinuous basement membrane and are tethered to the surrounding collagen and elastin fibers by anchoring filaments [27, 28]. The latter are composed of emilin-1 and fibrillin, and are thought to open lymphatic capillaries when the interstitial fluid pressure increases [29–31]. More specifically, anchoring filaments are thought to pull the LECs, thus opening their junctions, whenever the surrounding ECM swells in response to an increased fluid accumulation. As the intercellular junctions open up to several micrometers, the accumulated fluid enters the lymphatic capillary lumen through these openings [21, 29]. However, no lymphatic phenotype has been associated to fibrillin deficiency in mice [32]. In addition, although emilin-1-deficient mice show reduced lymph drainage, they are viable and only develop a mild lymphedema [31]. Therefore, a more basic mechanism of fluid uptake by lymphatic capillaries, involving ECM swelling and stiffening that stretch LECs and thus open their junctions, should alternatively be considered.

Transport of lymph

The plasma fluid absorbed by lymphatic capillaries (called lymph) is subsequently gathered in collecting lymphatic vessels that transport it to the two largest lymphatic vessels in the body: the thoracic duct (ductus thoracicus) and the right lymphatic trunk (ductus lymphaticus dexter) [2]. Lymph drained from the left part of the body, the abdomen, and both lower limbs is collected by the thoracic duct, whereas lymph drained from the right upper half of the body and head is transported to the right lymphatic trunk [2].

In contrast to lymphatic capillaries, the LECs of collecting lymphatic vessels exhibit features to prevent lymph from leaking out of their vascular lumens, including continuous zipper-like junctions and a continuous basement membrane surrounded by smooth muscle cells (SMCs) [23, 26]. In addition, collecting lymphatic vessels display intraluminal valves that prohibit backward fluid flow [33]. The SMC layer around collecting lymphatic vessels is regarded as intrinsically pumping to propulse the lymph [33].

Intrinsic lymphatic pump

Increases in lymph pressure leading to LEC stretching have been shown to activate the intrinsic lymphatic pump, but too large a lymphatic pressure can inhibit pumping, presumably due to a failure of the SMCs to contract [34, 35]. It has been proposed that shear stress caused by lymph flow is sensed by the LECs of the rat thoracic duct, which respond by releasing nitric oxide (NO) to induce vessel relaxation [36]. By measuring lymphocyte velocity, the average lymph flow and shear stress within rat mesenteric prenodal lymphatic vessels were estimated to be around 0.9 mm/s and 0.4–0.6 dyne/cm2, respectively [37]. Although the estimated values of lymph flow and shear stress in these vessels are considerably lower than those observed in the rat mesenteric blood microvasculature (blood flow: 2–8 mm/s for arterioles/arteries, 1–2 mm/s for venules/veins; shear stress: 100 dyne/cm2 for arterioles/arteries, 5 dyne/cm2 for venules/veins), similar relaxation mechanisms involving endothelial NO synthesis apply [38–40].

Extrinsic lymphatic pump

Besides the generation of contractile forces by the SMC layer enclosing the collecting lymphatic vessels, lymph is additionally propelled as a result of the contractility of the surrounding skeletal muscle, the pulsation of heart and arteries, peristaltic movements, respiratory motion, and skin compression. In a normal subject, daily activity (i.e., walking) increases lymph flow from the feet, while no tissue compression during sleeping time lowers it [41]. Similarly, lymph flow has been reported to increase during exercise, which is therefore recommended for the treatment of lymphedema [41, 42].

Lymph hearts

In mammals, intrinsic and extrinsic pumps for lymph flow have been reported [35]. In contrast, in fish, amphibians, reptiles, and birds, drained lymph is mostly transported via the contraction of lymph hearts [43]. They are composed of an LEC inner layer and an external muscle layer covered by fibroelastic tissue. The development of the lymphatic endothelium in mammals and lower vertebrates requires the expression of the same genes [43, 44]. Formation of the lymph heart musculature was recently shown to require the activation of genes different from those required for developing the lymphatic endothelium [45].

Mechanical forces in lymphatic vascular development

As described above, lymphatic vessels are subject to substantial mechanical forces, such as interstitial fluid pressure-induced LEC stretch and lymph flow-induced shear stress. Here, we discuss the contribution of mechanical stimuli to trigger growth and maturation of the lymphatic vasculature during development and disease.

Mechanotransduction during early lymphatic development

In mice, lymphatic vascular development starts at around embryonic day (E)9.5 with the upregulation of Sox18 and Prox1 in a subset of endothelial cells at the anterior cardinal vein [46, 47]. Both transcription factors are required for differentiation of LECs from venous ECs [46, 47]. Moreover, Prox1 and possibly the low amount of shear stress are involved in the maintenance of lymphatic vascular identity [48, 49].

Starting at E10.5, the LECs migrate towards the dorsolateral mesenchyme in a coordinated manner and form the first lymphatic vessels: the jugular lymph sacs or primordial thoracic ducts (JLS/pTD), which develop close to the cardinal veins, and the peripheral longitudinal lymphatic vessels (PLLVs), which eventually sprout and form the dermal lymphatic vasculature [50]. These steps are triggered by several different signals and include the vascular endothelial growth factor-C (VEGF-C), its receptor and co-receptor, VEGF receptor-3 (VEGFR3) and Neuropilin2, respectively, the secreted factor Ccbe1 (collagen- and calcium-binding EGF domains 1), and several others [25, 51–53].

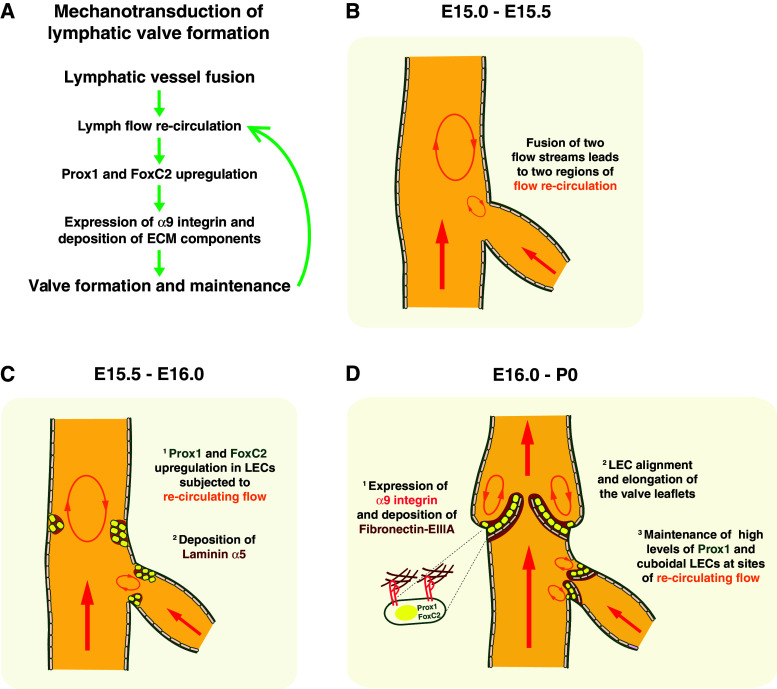

Correlation between interstitial fluid pressure and lymphatic vessel expansion

Coincident with the expansion of the initial lymphatic vessels, a peak in interstitial fluid pressure was detected in mouse embryos and shown to correlate with an enhanced tyrosine phosphorylation of VEGFR3 and an increase in LEC proliferation [54] (Fig. 1). The data therefore suggested that an increase in interstitial fluid pressure triggers a biological response in LECs that promotes lymphatic vascular growth. Consistent with this hypothesis, experimentally increasing or decreasing the amount of interstitial fluid in the embryonic tissue was shown to increase or decrease the growth of the lymphatic vasculature, respectively [54]. Furthermore, an increase in the total length and nuclear length of LECs was observed when the amount of interstitial fluid or interstitial fluid pressure was increased, indicating that LEC stretching might be an initial step during mechanotransduction and lymphatic vessel expansion.

Fig. 1.

Mechanoinduction of lymphatic vessel expansion. a Model to explain the expansion of lymphatic vessels, as shown for the jugular lymph sacs (JLS), also called primordial thoracic ducts (pTD), in early mouse embryos. b Mouse embryo at embryonic day (E)11.5, including a schematic representation of a jugular blood vessel and the first lymphatic vessels, namely JLS/pTD and peripheral longitudinal lymphatic vessels (PLLV). c Schematic diagram of fluid dynamics in mouse embryos at E11.5. Plasma fluid (shown as yellow areas and its flow as orange arrows) extravasates from blood vessels (1) and accumulates in the mesenchyme (2). d Schematic diagram of how the increased interstitial fluid pressure induces lymphatic vessel expansion in mouse embryos at E12.0. As plasma fluid extravasates (1) and continues to accumulate in the mesenchyme (2), the interstitial fluid pressure increases (3) and causes stretching of lymphatic endothelial cells (LECs) attached to the swollen extracellular matrix (ECM) (4). β1 integrin is subsequently activated in the stretched LECs and leads, possibly via activation of Src Family Kinases (SFK), to VEGFR3 tyrosine phosphorylation and signaling (4). Therefore, LECs start to proliferate to a significant extent (5), the lymphatic vessels enlarge (6) and more efficiently drain the accumulated interstitial fluid (7). e Temporal achievement of fluid balance at E12.5. Due to the expanded lymphatic vasculature, plasma leakage from the blood vessels (1) is encountered by an appropriate plasma fluid drainage (2). Please note that the embryonic days might differ by 0.5–1 day depending on the mouse strain used

β1 integrin- and VEGFR3-mediated mechanotransduction

Integrins are transmembrane ECM receptors that mediate mechanotransduction [55, 56]. The requirement of β1 integrins on LECs for translating the enhanced interstitial fluid pressure into VEGFR3 activation and LEC proliferation was demonstrated by genetically inactivating β1 integrins in endothelial cells [54]. Homozygous mice lacking β1 integrin showed a blunted proliferative response of LECs to an elevated interstitial fluid pressure. Furthermore, these mice harbored edema and a significantly reduced lymphatic vasculature, coinciding with reduced VEGFR3 tyrosine phosphorylation and decreased LEC proliferation [54].

In contrast to blood vascular endothelial cells (VECs) where VEGFR2 has been described to be part of a mechanosensory complex [57], in LECs no difference was observed in tyrosine phosphorylation of VEGFR2 when the amount of interstitial fluid was augmented [54]. The low expression level of VEGFR2 in LECs of the expanding lymphatic vasculature further indicates that VEGFR3 is the main mechano-induced VEGF receptor in LECs [54, 58]. Consistent with the hypothesis of a β1 integrin/VEGFR3 mechanosensory complex in LECs, VEGFR3 was shown to also be activated in a VEGF-C-independent [59, 60], but ECM-dependent manner in LECs and VECs [61].

The effects of β1 integrin- and VEGFR3-mediated mechanotransduction on VEGFR3 phosphorylation and LEC proliferation were additionally corroborated using two different in vitro assays, i.e., unidirectional stretching of LECs plated on fibronectin-coated silicon chambers, and growth of LECs on fibronectin-coated polyacrylamide gels of increasing stiffness (from 1 to 40 kPa, which correspond to the elasticity of brain and pre-calcified bones, respectively) [62]. In the presence of VEGF-C, both LEC stretching and stiff ECM substrates were able to significantly enhance VEGFR3 tyrosine phosphorylation and LEC proliferation in a β1 integrin- and VEGFR3-dependent manner [54]. This mechanotransduction mechanism for lymphatic vessel expansion in developing mouse embryos might also help to explain lymphatic hyperplasia in tumors and secondary lymphedema, as described later in this review.

Mechanotransduction of lymphatic valve formation

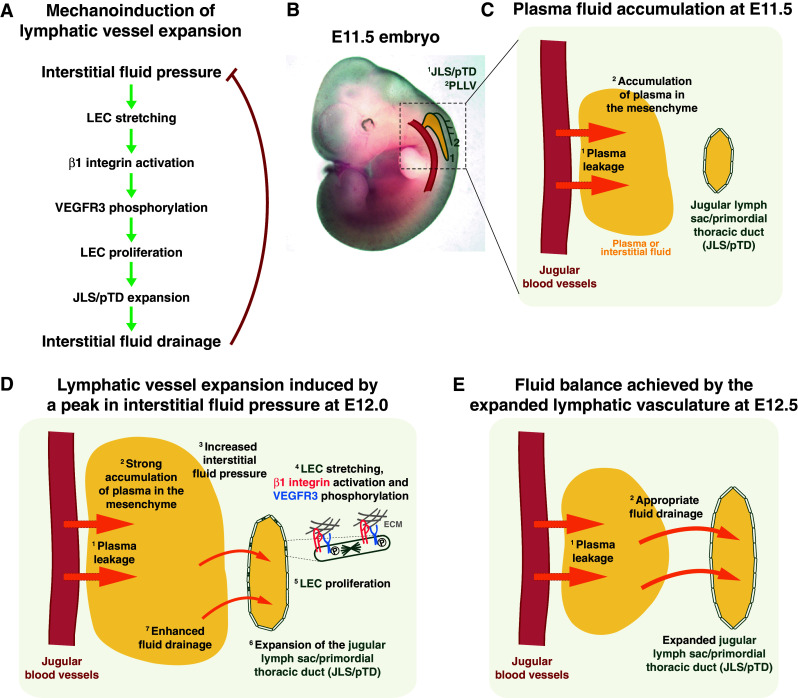

Lymph flow re-circulation at sites of lymphatic vessel fusion

The effect of lymph flow on valve morphogenesis was recently investigated [63]. Lymphatic valves are often found at sites of disturbed flow, like vessel bifurcations or branching points [64], suggesting a correlation between a non-laminar fluid flow and lymphatic valve formation. Since vessels are conduits that resemble fluid pipes, one could apply mathematical models of fluid motion through pipes to the fluid disturbances occurring at sites of vessel fusion [65]. More specifically, when a small lymphatic vessel fuses with a bigger one, the merge of their flow streams could generate two consecutive regions of disturbed flow: a first one next to the small vessel and a second one further downstream in the large vessel (Fig. 2). In the first region, re-circulating flow is caused by the incorporation of the flow stream from the small vessel into the stream of the large vessel. In the second region, re-circulating flow originates from the lateral push of the united flow streams towards the vessel wall (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Mechanotransduction of lymphatic valve formation. a Stepwise model of the development of lymphatic valves in collecting lymphatic vessels. b Schematic diagram of a small collecting lymphatic vessel draining into a larger one. When the two fluid streams merge, a small circular flow is created next to the small vessel branch and a larger area of flow re-circulation develops further downstream. c In the areas of flow re-circulation, the expression of the transcription factors Prox1 and FoxC2 become upregulated in LECs (1), and they adopt a cuboidal cell shape (1). The deposition of laminin α5 labels the future lymphatic valve territories (2). d Schematic diagram of valve formation at E16 and maturation in newborn mice. Prox1 initiates the expression of α9 integrin in LECs, which is required for the assembly of fibronectin-EIIIA (1). The LECs form clusters bulging into the vascular lumen and then align to form two valve flaps. During this process, the vessel is constricted (2). LECs on the downstream cell surface of the valve and on the valve sinuses maintain their cuboidal shape, since they are consistently subjected to re-circulating flow (3)

Cell-shape rearrangements at sites of lymph flow re-circulation

The LECs next to the areas of flow re-circulation within the collecting lymphatic vessels upregulate the expression of the transcription factors Prox1 and FoxC2 [63], suggesting that the LECs adjust their gene expression in response to re-circulating lymph flow. Supporting this hypothesis, the upregulation of FoxC2 was reproduced in cultured LECs by exposure to oscillatory shear stress (OSS) used to mimic re-circulating flow in vitro [63].

Cell-shape changes in LECs affected by re-circulating flow were observed concomitantly with the upregulation of Prox1 and FoxC2. In general, LECs adopt a cuboidal cell shape and present perinuclear F-actin stress fibers both in vivo at sites of flow re-circulation and in vitro under the conditions of OSS [63]. In vitro, silencing of Prox1 in LECs exposed to OSS prevented the development of cuboidal cell morphology [63], supporting a role of Prox1 in transducing mechanical signals. Cuboidal cell shapes have also been observed in developing human and mouse venous valves [66], in atrioventricular human heart valves [67], and in endocardial cells of zebrafish heart valves [68]. Thus, even though the contribution of re-circulating flow and shear stress might be different, comparable cell-shape rearrangements occur in these different valves [24].

In contrast to the LECs of the lymphatic valves, the LECs at the vessel wall not affected by re-circulating flow remain elongated and aligned in the flow direction [63]. A similar phenotype was observed when LECs were subjected to laminar shear stress [63]. To date, the molecular players that are upstream of Prox1 and FoxC2 and sense different kinds of flow and shear stress are still unknown.

Valve elongation and maintenance

The LEC clusters expressing high levels of Prox1 and FoxC2 move into the lymphatic vascular lumen to form the final shape of the valve leaflets. The mature valves are composed of two layers of LECs tethered to a laminin α5-rich basement membrane [24]. Whereas the upstream LEC layer contains elongated cells expressing low levels of Prox1, the downstream layer is composed of cuboidal LECs, with elevated Prox1 expression, coincident with the site of re-circulating lymph flow [63].

Recently, it was observed that the LEC clusters at the collecting lymphatic vessels that express high levels of Prox1 also upregulated α9 integrin at around E17.5, coincident with the alignment of clustered LECs to generate elongated valve leaflets [64]. Prox1 was previously shown in vitro to be involved in the upregulation of α9 integrin [69], which is necessary for the elongation of both lymphatic and venous valves [64, 66]. Furthermore, α9 integrins support the deposition of fibronectin and, in conjunction with the EIIIA domain of fibronectin, assist fibronectin fibrillogenesis [64].

Several other signaling cascades have also been shown to be responsible for lymphatic valve morphogenesis, but their roles in mechanotransduction have not yet been studied [70–74]. Therefore, further analyses are required to characterize how these molecular networks combine to respond to changes in flow direction and shear stress.

Mechanoinduction of lymphatic hyperplasia in tumors

The presence of tumor-associated lymphatic vessels correlates with poor prognosis in patients suffering from different types of cancer [75]. Two kinds of tumor-associated lymphatic vessels exist: peritumoral ones at the tumor periphery, and intratumoral ones found inside the tumor tissue. Peritumoral lymphatic vessels are commonly hyperplastic and dilated, and are used by cancer cells to gain access to lymph nodes [9, 75, 76]. In contrast, the function and contribution of intratumoral lymphatic vessels to cancer cell spreading is still debated [77–81].

Mechanoinduction of peritumoral lymphatic hyperplasia

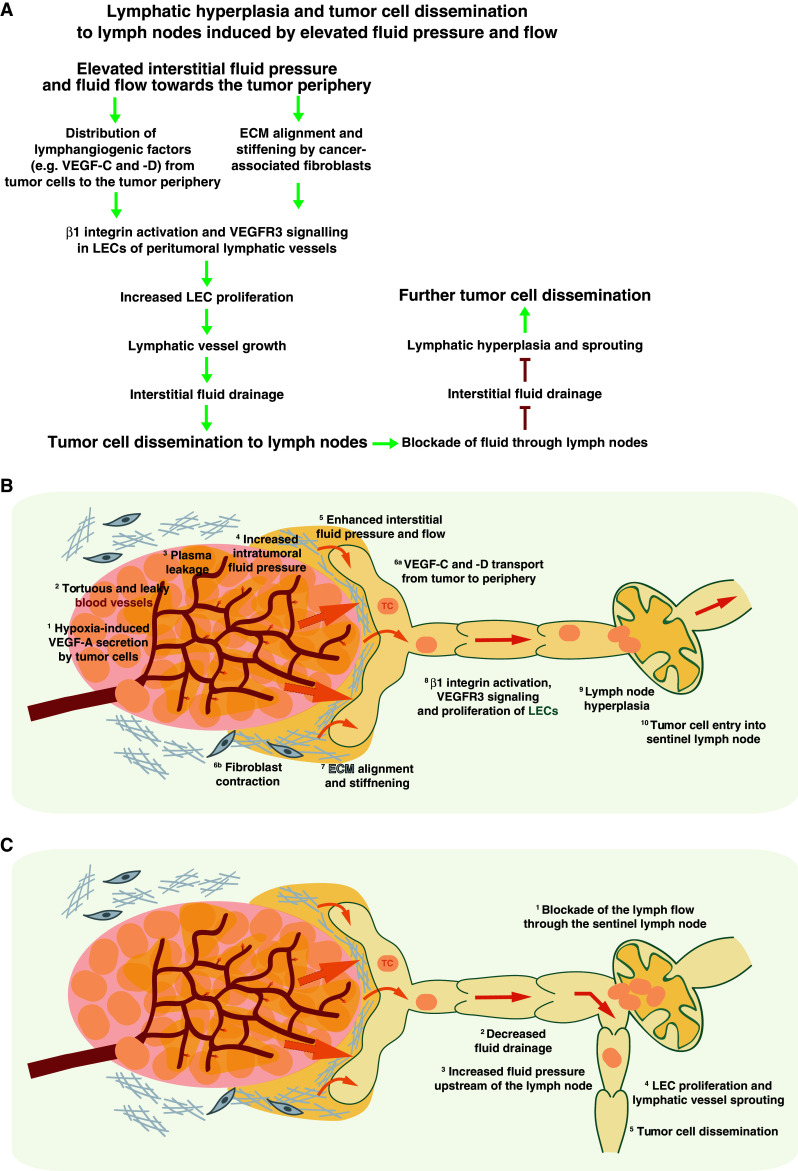

Tumor blood vessels are often not differentiated into arterioles and venules, contain few, abnormally adhering pericytes, and are leaky [82, 83]. The vascular hyperpermeability of tumors promotes plasma extravasation, plasma fluid accumulation in the tumor matrix, and a high intratumoral fluid pressure [84]. Interstitial fluid pressure in human mammary adenocarcinomas transplanted into rats is about 16.5 mmHg, and thus comparable to the hydrostatic pressure observed in venules [85]. Possibly as a result of this extremely high intratumoral interstitial fluid pressure, lymphatic vessels inside the tumor tend to collapse, and the non-absorbed fluid is pushed towards the tumor periphery [77, 84]. The resulting fluid flow likely contributes to the development of a hyperplastic and expanded lymphatic vasculature at the tumor margin [9, 80, 86, 87] (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Lymphatic hyperplasia and tumor cell dissemination by increased fluid pressure and flow. a Stepwise model of the formation of hyperplastic lymphatic vessels at the tumor periphery, as a consequence of increased fluid pressure and flow, promoting tumor cell dissemination. b Schematic diagram of the induction of lymphatic vessel hyperplasia and tumor cell dissemination by increased fluid pressure and flow. Since tumor cores are generally hypoxic and express VEGF-A (1), also known as vascular permeability factor (VPF), tortuous and highly permeable blood vessels (2) develop inside tumors. Exacerbated plasma leakage from blood vessels (3) raises the fluid pressure within the tumor (4) and drives plasma fluid towards the tumor periphery (5), thereby facilitating the distribution of tumor-derived VEGF-C and VEGF-D (6a). The increased interstitial fluid pressure (5) causes mechanical stress on the cancer-associated fibroblasts that subsequently contract (6b), and promote ECM alignment and stiffening (7). The distribution of lymphangiogenic factors and the mechanical stimulus induce β1 integrin- and VEGFR3 signaling to promote LEC proliferation (8), as described in detail in Fig. 1. Hyperplasia of the lymphatic vasculature and lymph nodes (9) and tumor cell dissemination (10) follow. c Tumor cells might block fluid flow through the sentinel lymph node at some point (1) and diminish fluid drainage (2). Fluid accumulation at the afferent side of the lymph node might enhance fluid pressure (3) and promote LEC proliferation and sprouting (4). The newly formed lymphatic vessel might develop into an additional route for tumor cells to infiltrate distant lymph nodes (5)

Flow-induced peritumoral ECM rearrangements

Using devices to manipulate interstitial fluid flow, it was shown that in fibroblasts fluid flow induces collagen deposition and alignment in an α1β1 integrin- and TGFβ1-dependent manner [88]. In this scenario, the fluid flow turns on TGFβ1 secretion in fibroblasts that subsequently differentiate into myofibroblasts that contract and stiffen the ECM [88]. Similar mechanisms are thought to play a role in cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) during tumor growth [9, 89].

Mechano-induced peritumoral lymphatic hyperplasia

Since β1 integrins on LECs are required to translate an increased interstitial fluid pressure as well as cell stretching or ECM stiffening into LEC proliferation [54], a role of β1 integrins in mechanoinduction of peritumoral lymphatic hyperplasia is to be considered. Consistent with this hypothetical scenario, strong expression of α4β1 integrins was observed in proliferating LECs in mammary and gastric tumors [90]. When Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) cells were transplanted subcutaneously or when pancreatic carcinoma cells were transplanted in the pancreas, tumoral lymphangiogenesis was significantly reduced in α4 integrin signaling-defective mice compared to controls [90], suggesting that α4β1 integrins on LECs are necessary for fully inducing lymphatic vascular growth in response to tumors.

Therefore, the elevated interstitial fluid pressure together with the increased lymph flow at the tumor margins might lead to ECM stiffening and LEC stretching, which activates β1 integrins (Fig. 3) [9, 54]. Subsequently, β1 integrin signaling could transactivate VEGFR3, thus leading to LEC proliferation and finally lymphatic hyperplasia. The whole process is strongly governed by VEGF-C and -D secreted by tumor cells and tumor-associated myeloid cells [91–97]. Since these growth factors trigger phosphorylation of tyrosines on VEGFR3, which are different from those phosphorylated via integrin signaling [61], both VEGF-C and -D and mechanical signals are likely involved in inducing full VEGFR3 signaling and thus the expansion of the peritumoral lymphatic vasculature (Fig. 3).

Putative consequences of mechano-induced peritumoral lymphatic hyperplasia

The expanded lymphatic vasculature has been hypothesized to facilitate the dissemination of tumor cells to sentinel lymph nodes [75]. Whether an increased fluid drainage promotes entry of tumor cells into lymphatic vessels is still unknown. However, ECM stiffening that can result from a high interstitial fluid pressure and flow might enhance the ability of tumor cells to gain access to the lymphatic vascular lumen, as recently indicated using an in vitro cell invasion assay [98]. Tumor cells circulating within the tumor-draining lymphatic vessels eventually reach sentinel lymph nodes, and might block fluid flow through these at some point [87]. Since circulating lymph contains antigen-presenting cells (APCs) derived from the tumor, this blockade of fluid flow through lymph nodes by tumor cells might reduce immune responses against the tumor [9]. A possible result of a reduced lymph flow through lymph nodes might be an increased interstitial fluid pressure at the afferent side of the lymph node. Once again, the interstitial fluid pressure might act as a mechanoinducer of LEC proliferation and sprouting, and could thereby create a new emerging route for tumor cells to metastasize to distant sites.

Mechanotransduction during secondary lymphedema

Dysfunction of lymphatic vessels results in progressive accumulation of plasma protein-rich fluid in the interstitium, ultimately leading to permanent tissue swelling or lymphedema [42]. Lymphedema is a debilitating and disfiguring disorder eventually causing adipose degeneration, impaired wound healing and a higher susceptibility to infections and to certain types of cancers, such as angiosarcoma [99]. Lymphedema can be classified depending on the underlying pathomechanism. While hereditary or primary lymphedema is a rare genetic condition, over 99 % of lymphedema are acquired after damage of lymphatic vessels and called secondary lymphedema [42, 100]. In general, lymphedema patients develop either a hypoplastic or a hyperplastic lymphatic vasculature depending on the underlying cause [22, 101].

Secondary lymphedema that is often described to be hyperplastic [102–104] occurs as a consequence of the surgical removal of lymph nodes that have been infiltrated by tumor cells, or following filarial infection [42, 100]. In all cases, an impaired lymph drainage and lymph flow is a probable cause for the accumulation of plasma fluid within the affected tissues. Breast cancer surgery constitutes the leading cause of secondary lymphedema in industrialized countries [100], and approximately 30 % of the patients develop lymphedema of an upper limb following an axillary lymph node dissection [42]. In contrast to the Western societies, the main cause of lymphedema worldwide is filariasis or elephantiasis, affecting over 120 million people, of whom 40 million are disfigured and incapacitated by the disease [105]. Three species of nematode worms (Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi, and Brugia timori) carried by mosquitoes transmit the disease [105]. Filarial infection triggers an inflammatory reaction that stimulates the production of lymphangiogenic factors, thus leading to persistent hyperplasia of the lymphatic vasculature. The most commonly affected areas include the limbs and genitals [101, 104].

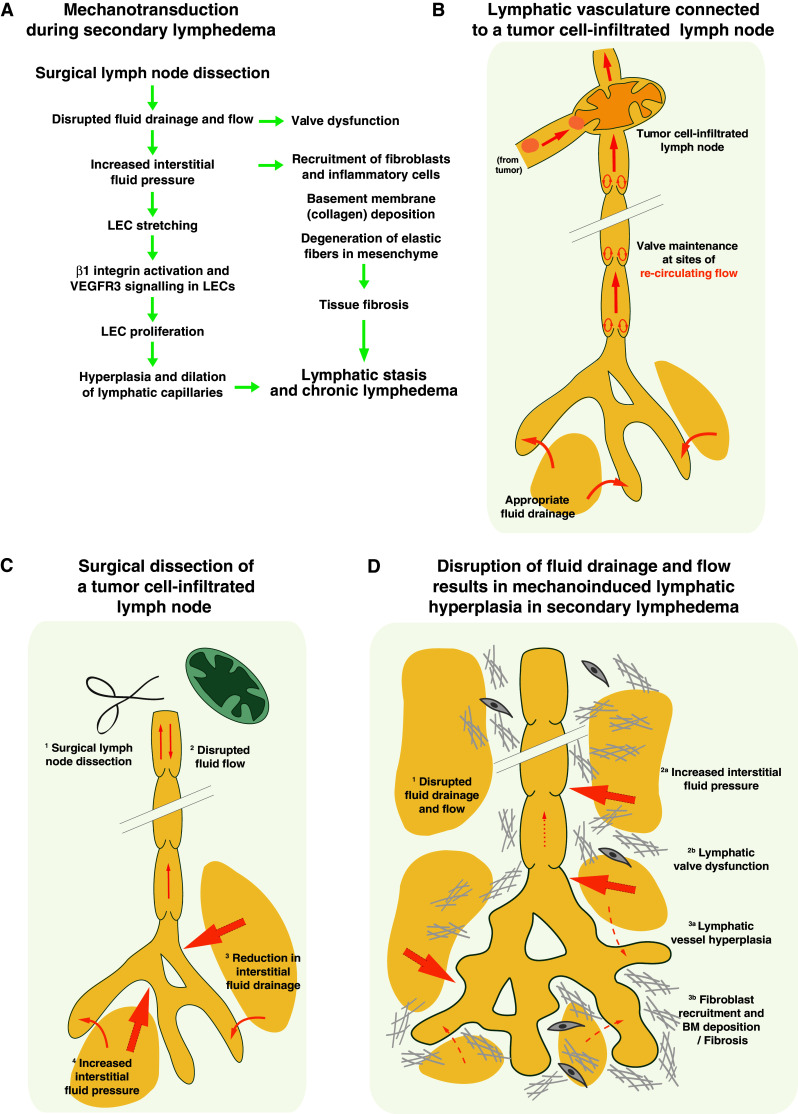

Mechanotransduction of lymphatic hyperplasia during secondary lymphedema

Surgical dissection of lymph nodes that have previously been infiltrated by tumor cells interrupts lymph transport between the lymphatic vessels upstream and downstream of the removed lymph nodes. Since the afferent lymph flow cannot be brought back to the blood circulation, we speculated that an accumulation of lymph within the lymphatic vessels might promote their expansion and slow down plasma fluid drainage by the initial lymphatic capillaries (Fig. 4). The subsequent accumulation of interstitial fluid might enhance interstitial fluid pressure and induce lymphatic hyperplasia (Fig. 4). In such a scenario, the LECs of the initial lymphatic capillaries that are attached to the swollen ECM might subsequently stretch and activate mechanosensory complexes that stimulate their proliferation, as described for early lymphangiogenesis [54]. In addition, the disrupted lymph flow through collecting lymphatic vessels might fail to maintain lymphatic valves, due to a lack of re-circulating flow (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Lymphatic hyperplasia induced by high interstitial fluid pressure in secondary lymphedema. a Stepwise model of the contribution of mechanotransduction to lymphatic hyperplasia in secondary lymphedema. Note the absence of a negative feedback loop, since the expanded lymphatic vessels cannot drain fluid. b Schematic diagram of a physiologic lymphatic vasculature that drains interstitial fluid into a tumor cell-infiltrated lymph node. c After surgical removal of the tumor cell-infiltrated lymph node (1), lymph flow within the lymphatic vasculature is extensively impaired (2), preventing the lymphatic capillaries from properly draining interstitial fluid (3). Consequently, the fluid pressure in the interstitium rises (4). d The impaired lymph drainage (1) increases the interstitial fluid pressure (2a), thus triggering lymphatic vessel hyperplasia (3a). The same mechanism involved in embryonic lymphatic vessel expansion (Fig. 1) might induce this abnormal growth of the lymphatic vasculature (2a, 3a). In addition, the absence of flow might fail to maintain high levels of Prox1 expression, thus leading to lymphatic valve regression and dysfunction (2b). As the disease advances, fibroblasts stiffen the ECM and recruitment of inflammatory cells contributes to tissue fibrosis (3b)

As the disease advances, both the increased interstitial fluid pressure and the release of growth factors might stimulate the recruitment of fibroblasts and inflammatory cells, which help to promote the degeneration of the affected tissues. Classical hallmarks of tissue degeneration include basement membrane deposition and deterioration of the elastic fibers that constitute the ECM, leading to tissue fibrosis [106]. A significantly reduced or absent movement of lymph, known as lymphatic stasis, as well as tissue fibrosis finally result in chronic lymphedema [106] (Fig. 4). Interestingly, studies in the mouse tail skin have implicated interstitial flow in facilitating the resolution of secondary lymphedema via lymphatic vessel regeneration, in cooperation with the expression of VEGF-C and specific matrix metalloproteinases [107], suggesting that enhancement of lymph flow as a mechanical stimulus might be a measure to counteract lymphedema formation.

Palliation of lymphedema based on massage and compression therapies

Although chronic lymphedema is a lifelong disabling condition, no curative treatment exists to date. Current palliative treatments are based on the use of compressive garments and lymphatic massage, which can decrease the limb volume of an affected person by 40–60 % [42]. However, a high variability exists in the response of each patient to such treatments [42]. Additional conservative approaches are recommended to reduce infections and limb volume, and include proper skin care and remedial exercises, respectively [106]. Since lymphedema patients also show abnormal fat deposition [42, 108], suction-assisted lipectomy is considered the most promising surgical procedure in patients that do not show a significant benefit after the conventional compressive therapy [109, 110].

Taken together, current treatments of lymphedema are based on generation of physical force. Further analyses on how precisely, in terms of time and space, external massage and compression need to be applied to improve function, and possibly regeneration of the lymphatic vessels, are required to optimize these mechanical forces for the most efficient treatment of secondary lymphedema. For example, massage directed towards the region lacking lymph nodes soon after surgery might be helpful to accurately localize lymphatic regeneration to the correct areas and limit pathological LEC proliferation at other sites.

Final remarks

Even though strong evidence has been provided for the existence of mechano-induced VEGFR3 phosphorylation and LEC proliferation both in vivo in the developing mouse embryo and in vitro in human LECs, to date, it is still not proven whether similar mechanisms apply to peritumoral hyperplasia or secondary lymphedema in adult mice and human patients. However, the therapeutic implications might be promising. For example, one could imagine combining anti-VEGFR3 treatments with an anti-integrin directed treatment in the future to efficiently reduce lymph node metastasis. Moreover, lymph massage directed to apply mechanical force selectively at the specific site where the lymphatic vasculature is to be regenerated could prove useful for the treatment of secondary lymphedema.

It is still too early to predict the outcome of such studies, but the discovery of the involvement of both VEGF-C-induced VEGFR3 signaling and mechano-induced integrin signaling in lymphatic vascular growth could open a new era in terms of therapeutic interventions.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sofia Neufeld and Dr. Daniel Eberhard in Düsseldorf for critical comments on this manuscript. The Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG LA1216/5-1) supported this work.

References

- 1.Aukland K, Reed RK. Interstitial-lymphatic mechanisms in the control of extracellular fluid volume. Physiol Rev. 1993;73(1):1–78. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1993.73.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jeltsch M, Tammela T, Alitalo K, Wilting J. Genesis and pathogenesis of lymphatic vessels. Cell Tissue Res. 2003;314(1):69–84. doi: 10.1007/s00441-003-0777-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adams RH, Alitalo K. Molecular regulation of angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8(6):464–478. doi: 10.1038/nrm2183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swartz MA, Boardman KC., Jr The role of interstitial stress in lymphatic function and lymphangiogenesis. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2002;979:197–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04880.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levick JR, Michel CC. Microvascular fluid exchange and the revised Starling principle. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;87(2):198–210. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor AE. Capillary fluid filtration. Starling forces and lymph flow. Circ Res. 1981;49(3):557–575. doi: 10.1161/01.res.49.3.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmid-Schonbein GW. Microlymphatics and lymph flow. Physiol Rev. 1990;70(4):987–1028. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1990.70.4.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Becker BF, Chappell D, Jacob M. Endothelial glycocalyx and coronary vascular permeability: the fringe benefit. Basic Res Cardiol. 2010;105(6):687–701. doi: 10.1007/s00395-010-0118-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swartz MA, Lund AW. Lymphatic and interstitial flow in the tumour microenvironment: linking mechanobiology with immunity. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12(3):210–219. doi: 10.1038/nrc3186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Girard JP, Moussion C, Forster R. HEVs, lymphatics and homeostatic immune cell trafficking in lymph nodes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12(11):762–773. doi: 10.1038/nri3298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Machnik A, Neuhofer W, Jantsch J, Dahlmann A, Tammela T, Machura K, Park JK, Beck FX, Muller DN, Derer W, Goss J, Ziomber A, Dietsch P, Wagner H, van Rooijen N, Kurtz A, Hilgers KF, Alitalo K, Eckardt KU, Luft FC, Kerjaschki D, Titze J. Macrophages regulate salt-dependent volume and blood pressure by a vascular endothelial growth factor-C-dependent buffering mechanism. Nat Med. 2009;15(5):545–552. doi: 10.1038/nm.1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abbott NJ, Ronnback L, Hansson E. Astrocyte-endothelial interactions at the blood–brain barrier. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7(1):41–53. doi: 10.1038/nrn1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Runkle EA, Antonetti DA. The blood–retinal barrier: structure and functional significance. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;686:133–148. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-938-3_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mandriota SJ, Jussila L, Jeltsch M, Compagni A, Baetens D, Prevo R, Banerji S, Huarte J, Montesano R, Jackson DG, Orci L, Alitalo K, Christofori G, Pepper MS. Vascular endothelial growth factor-C-mediated lymphangiogenesis promotes tumour metastasis. EMBO J. 2001;20(4):672–682. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.4.672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Partanen TA, Arola J, Saaristo A, Jussila L, Ora A, Miettinen M, Stacker SA, Achen MG, Alitalo K. VEGF-C and VEGF-D expression in neuroendocrine cells and their receptor, VEGFR-3, in fenestrated blood vessels in human tissues. FASEB J: Off Publ Federation Am Soc Exp Biol. 2000;14(13):2087–2096. doi: 10.1096/fj.99-1049com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Morchoe CC. Lymphatic system of the pancreas. Microsc Res Tech. 1997;37(5–6):456–477. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19970601)37:5/6<456::AID-JEMT9>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Konstantinova I, Nikolova G, Ohara-Imaizumi M, Meda P, Kucera T, Zarbalis K, Wurst W, Nagamatsu S, Lammert E. EphA-Ephrin-A-mediated beta cell communication regulates insulin secretion from pancreatic islets. Cell. 2007;129(2):359–370. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eberhard D, Kragl M, Lammert E. ‘Giving and taking’: endothelial and beta-cells in the islets of Langerhans. Trends Endocrinol Metab:TEM. 2010;21(8):457–463. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scallan J, Huxley VH, Korthuis RJ. Capillary fluid exchange: regulation, functions and pathology. San Rafael (CA): Morgan & Claypool Life Sciences; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilting J, Becker J, Buttler K, Weich HA. Lymphatics and inflammation. Curr Med Chem. 2009;16(34):4581–4592. doi: 10.2174/092986709789760751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maby-El Hajjami HPT. Developmental and pathological lymphangiogenesis: from models to human disease. Histochem Cell Biol. 2008;130(6):1063–1078. doi: 10.1007/s00418-008-0525-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tammela T, Alitalo K. Lymphangiogenesis: molecular mechanisms and future promise. Cell. 2010;140(4):460–476. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Makinen T, Norrmen C, Petrova TV. Molecular mechanisms of lymphatic vascular development. Cell Mol Life Sci:CMLS. 2007;64(15):1915–1929. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7040-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bazigou E, Makinen T. Flow control in our vessels: vascular valves make sure there is no way back. Cell Mol Life Sci: CMLS. 2013;70(6):1055–1066. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1110-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schulte-Merker S, Sabine A, Petrova TV. Lymphatic vascular morphogenesis in development, physiology, and disease. J Cell Biol. 2011;193(4):607–618. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201012094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baluk P, Fuxe J, Hashizume H, Romano T, Lashnits E, Butz S, Vestweber D, Corada M, Molendini C, Dejana E, McDonald DM. Functionally specialized junctions between endothelial cells of lymphatic vessels. J Exp Med. 2007;204(10):2349–2362. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leak LV, Burke JF. Fine structure of the lymphatic capillary and the adjoining connective tissue area. Am J Anat. 1966;118(3):785–809. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001180308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leak LV, Burke JF. Ultrastructural studies on the lymphatic anchoring filaments. J Cell Biol. 1968;36(1):129–149. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leak LV, Burke JF. Electron microscopic study of lymphatic capillaries in the removal of connective tissue fluids and particulate substances. Lymphology. 1968;1(2):39–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Skobe M, Detmar M (2000) Structure, function, and molecular control of the skin lymphatic system. The journal of investigative dermatology Symposium proceedings/the Society for Investigative Dermatology, Inc [and] European Society for Dermatological Research 5 (1):14–19. doi:10.1046/j.1087-0024.2000.00001.x [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Danussi C, Spessotto P, Petrucco A, Wassermann B, Sabatelli P, Montesi M, Doliana R, Bressan GM, Colombatti A. Emilin1 deficiency causes structural and functional defects of lymphatic vasculature. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28(12):4026–4039. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02062-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pereira L, Andrikopoulos K, Tian J, Lee SY, Keene DR, Ono R, Reinhardt DP, Sakai LY, Biery NJ, Bunton T, Dietz HC, Ramirez F. Targeting of the gene encoding fibrillin-1 recapitulates the vascular aspect of Marfan syndrome. Nat Genet. 1997;17(2):218–222. doi: 10.1038/ng1097-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Petrova TV, Karpanen T, Norrmen C, Mellor R, Tamakoshi T, Finegold D, Ferrell R, Kerjaschki D, Mortimer P, Yla-Herttuala S, Miura N, Alitalo K. Defective valves and abnormal mural cell recruitment underlie lymphatic vascular failure in lymphedema distichiasis. Nat Med. 2004;10(9):974–981. doi: 10.1038/nm1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hargens AR, Zweifach BW. Contractile stimuli in collecting lymph vessels. Am J Physiol. 1977;233(1):H57–H65. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1977.233.1.H57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gashev AA, Zawieja DC. Hydrodynamic regulation of lymphatic transport and the impact of aging. Pathophysiol: Off J Int Soc Pathophysiol/ISP. 2010;17(4):277–287. doi: 10.1016/j.pathophys.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bohlen HG, Wang W, Gashev A, Gasheva O, Zawieja D. Phasic contractions of rat mesenteric lymphatics increase basal and phasic nitric oxide generation in vivo. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297(4):H1319–H1328. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00039.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dixon JB, Greiner ST, Gashev AA, Cote GL, Moore JE, Zawieja DC. Lymph flow, shear stress, and lymphocyte velocity in rat mesenteric prenodal lymphatics. Microcirculation. 2006;13(7):597–610. doi: 10.1080/10739680600893909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pries AR, Secomb TW, Gaehtgens P. Design principles of vascular beds. Circ Res. 1995;77(5):1017–1023. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.5.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pyke KE, Tschakovsky ME. The relationship between shear stress and flow-mediated dilatation: implications for the assessment of endothelial function. J Physiol. 2005;568(Pt 2):357–369. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.089755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.le Noble F, Fleury V, Pries A, Corvol P, Eichmann A, Reneman RS. Control of arterial branching morphogenesis in embryogenesis: go with the flow. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;65(3):619–628. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Olszewski WEA, Jaeger PM, Sokolowski J, Theodorsen L. Flow and composition of leg lymph in normal men during venous stasis, muscular activity and local hyperthermia. Acta Physiol Scand. 1977;99(2):149–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1977.tb10365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Warren AG, Brorson H, Borud LJ, Slavin SA. Lymphedema: a comprehensive review. Ann Plast Surg. 2007;59(4):464–472. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000257149.42922.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ny A, Koch M, Schneider M, Neven E, Tong RT, Maity S, Fischer C, Plaisance S, Lambrechts D, Heligon C, Terclavers S, Ciesiolka M, Kalin R, Man WY, Senn I, Wyns S, Lupu F, Brandli A, Vleminckx K, Collen D, Dewerchin M, Conway EM, Moons L, Jain RK, Carmeliet P. A genetic Xenopus laevis tadpole model to study lymphangiogenesis. Nat Med. 2005;11(9):998–1004. doi: 10.1038/nm1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ny A, Koch M, Vandevelde W, Schneider M, Fischer C, Diez-Juan A, Neven E, Geudens I, Maity S, Moons L, Plaisance S, Lambrechts D, Carmeliet P, Dewerchin M. Role of VEGF-D and VEGFR-3 in developmental lymphangiogenesis, a chemicogenetic study in Xenopus tadpoles. Blood. 2008;112(5):1740–1749. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-106302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peyrot SM, Martin BL, Harland RM. Lymph heart musculature is under distinct developmental control from lymphatic endothelium. Dev Biol. 2010;339(2):429–438. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wigle JT, Oliver G. Prox1 function is required for the development of the murine lymphatic system. Cell. 1999;98(6):769–778. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81511-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Francois M, Caprini A, Hosking B, Orsenigo F, Wilhelm D, Browne C, Paavonen K, Karnezis T, Shayan R, Downes M, Davidson T, Tutt D, Cheah KS, Stacker SA, Muscat GE, Achen MG, Dejana E, Koopman P. Sox18 induces development of the lymphatic vasculature in mice. Nature. 2008;456(7222):643–647. doi: 10.1038/nature07391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Johnson NC, Dillard ME, Baluk P, McDonald DM, Harvey NL, Frase SL, Oliver G. Lymphatic endothelial cell identity is reversible and its maintenance requires Prox1 activity. Genes Dev. 2008;22(23):3282–3291. doi: 10.1101/gad.1727208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen CY, Bertozzi C, Zou Z, Yuan L, Lee JS, Lu M, Stachelek SJ, Srinivasan S, Guo L, Vicente A, Mericko P, Levy RJ, Makinen T, Oliver G, Kahn ML. Blood flow reprograms lymphatic vessels to blood vessels. J Clin Investig. 2012;122(6):2006–2017. doi: 10.1172/JCI57513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hagerling R, Pollmann C, Andreas M, Schmidt C, Nurmi H, Adams RH, Alitalo K, Andresen V, Schulte-Merker S, Kiefer F. A novel multistep mechanism for initial lymphangiogenesis in mouse embryos based on ultramicroscopy. EMBO J. 2013;32(5):629–644. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yuan L, Moyon D, Pardanaud L, Breant C, Karkkainen MJ, Alitalo K, Eichmann A. Abnormal lymphatic vessel development in neuropilin 2 mutant mice. Development. 2002;129(20):4797–4806. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.20.4797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Karkkainen MJ, Haiko P, Sainio K, Partanen J, Taipale J, Petrova TV, Jeltsch M, Jackson DG, Talikka M, Rauvala H, Betsholtz C, Alitalo K. Vascular endothelial growth factor C is required for sprouting of the first lymphatic vessels from embryonic veins. Nat Immunol. 2004;5(1):74–80. doi: 10.1038/ni1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bos FL, Caunt M, Peterson-Maduro J, Planas-Paz L, Kowalski J, Karpanen T, van Impel A, Tong R, Ernst JA, Korving J, van Es JH, Lammert E, Duckers HJ, Schulte-Merker S. CCBE1 is essential for mammalian lymphatic vascular development and enhances the lymphangiogenic effect of vascular endothelial growth factor-C in vivo. Circ Res. 2011;109(5):486–491. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.250738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Planas-Paz L, Strilic B, Goedecke A, Breier G, Fassler R, Lammert E. Mechanoinduction of lymph vessel expansion. EMBO J. 2012;31(4):788–804. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ingber DE. Cellular mechanotransduction: putting all the pieces together again. FASEB J: Off Pub Federation Am Soc Exp Biol. 2006;20(7):811–827. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5424rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schwartz MA. Integrins and extracellular matrix in mechanotransduction. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect Biol. 2010;2(12):a005066. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a005066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tzima E, Irani-Tehrani M, Kiosses WB, Dejana E, Schultz DA, Engelhardt B, Cao G, DeLisser H, Schwartz MA. A mechanosensory complex that mediates the endothelial cell response to fluid shear stress. Nature. 2005;437(7057):426–431. doi: 10.1038/nature03952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kaipainen A, Korhonen J, Mustonen T, van Hinsbergh VW, Fang GH, Dumont D, Breitman M, Alitalo K. Expression of the fms-like tyrosine kinase 4 gene becomes restricted to lymphatic endothelium during development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92(8):3566–3570. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Haiko P, Makinen T, Keskitalo S, Taipale J, Karkkainen MJ, Baldwin ME, Stacker SA, Achen MG, Alitalo K. Deletion of vascular endothelial growth factor C (VEGF-C) and VEGF-D is not equivalent to VEGF receptor 3 deletion in mouse embryos. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28(15):4843–4850. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02214-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang LZF, Han W, Shen B, Luo J, Shibuya M, He Y. VEGFR-3 ligand-binding and kinase activity are required for lymphangiogenesis but not for angiogenesis. Cell Res. 2010;20(12):1319–1331. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Galvagni F, Pennacchini S, Salameh A, Rocchigiani M, Neri F, Orlandini M, Petraglia F, Gotta S, Sardone GL, Matteucci G, Terstappen GC, Oliviero S. Endothelial cell adhesion to the extracellular matrix induces c-Src-dependent VEGFR-3 phosphorylation without the activation of the receptor intrinsic kinase activity. Circ Res. 2010;106(12):1839–1848. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.206326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tse JR, Engler AJ (2010) Preparation of hydrogel substrates with tunable mechanical properties. Current Protocols in Cell Biology/editorial board, Juan S Bonifacino [et al] Chapter 10:Unit 10 16. doi:10.1002/0471143030.cb1016s47 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 63.Sabine A, Agalarov Y, Maby-El Hajjami H, Jaquet M, Hagerling R, Pollmann C, Bebber D, Pfenniger A, Miura N, Dormond O, Calmes JM, Adams RH, Makinen T, Kiefer F, Kwak BR, Petrova TV. Mechanotransduction, PROX1, and FOXC2 cooperate to control connexin37 and calcineurin during lymphatic-valve formation. Dev Cell. 2012;22(2):430–445. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bazigou E, Xie S, Chen C, Weston A, Miura N, Sorokin L, Adams R, Muro AF, Sheppard D, Makinen T. Integrin-alpha9 is required for fibronectin matrix assembly during lymphatic valve morphogenesis. Dev Cell. 2009;17(2):175–186. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kilian S, Turek S. Virtual album of fluid motion. Springer. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bazigou E, Lyons OT, Smith A, Venn GE, Cope C, Brown NA, Makinen T. Genes regulating lymphangiogenesis control venous valve formation and maintenance in mice. J Clin Investig. 2011;121(8):2984–2992. doi: 10.1172/JCI58050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Maron BJ, Hutchins GM. The development of the semilunar valves in the human heart. Am J Pathol. 1974;74(2):331–344. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Beis D, Bartman T, Jin SW, Scott IC, D’Amico LA, Ober EA, Verkade H, Frantsve J, Field HA, Wehman A, Baier H, Tallafuss A, Bally-Cuif L, Chen JN, Stainier DY, Jungblut B. Genetic and cellular analyses of zebrafish atrioventricular cushion and valve development. Development. 2005;132(18):4193–4204. doi: 10.1242/dev.01970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mishima K, Watabe T, Saito A, Yoshimatsu Y, Imaizumi N, Masui S, Hirashima M, Morisada T, Oike Y, Araie M, Niwa H, Kubo H, Suda T, Miyazono K. Prox1 induces lymphatic endothelial differentiation via integrin alpha9 and other signaling cascades. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18(4):1421–1429. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-09-0780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Makinen T, Adams RH, Bailey J, Lu Q, Ziemiecki A, Alitalo K, Klein R, Wilkinson GA. PDZ interaction site in ephrinB2 is required for the remodeling of lymphatic vasculature. Genes Dev. 2005;19(3):397–410. doi: 10.1101/gad.330105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Norrmen C, Ivanov KI, Cheng J, Zangger N, Delorenzi M, Jaquet M, Miura N, Puolakkainen P, Horsley V, Hu J, Augustin HG, Yla-Herttuala S, Alitalo K, Petrova TV. FOXC2 controls formation and maturation of lymphatic collecting vessels through cooperation with NFATc1. J Cell Biol. 2009;185(3):439–457. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200901104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kanady JD, Dellinger MT, Munger SJ, Witte MH, Simon AM. Connexin37 and Connexin43 deficiencies in mice disrupt lymphatic valve development and result in lymphatic disorders including lymphedema and chylothorax. Dev Biol. 2011;354(2):253–266. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bouvree K, Brunet I, Del Toro R, Gordon E, Prahst C, Cristofaro B, Mathivet T, Xu Y, Soueid J, Fortuna V, Miura N, Aigrot MS, Maden CH, Ruhrberg C, Thomas JL, Eichmann A. Semaphorin3A, Neuropilin-1, and PlexinA1 are required for lymphatic valve formation. Circ Res. 2012;111(4):437–445. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.269316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Norrmen C, Vandevelde W, Ny A, Saharinen P, Gentile M, Haraldsen G, Puolakkainen P, Lukanidin E, Dewerchin M, Alitalo K, Petrova TV. Liprin (beta)1 is highly expressed in lymphatic vasculature and is important for lymphatic vessel integrity. Blood. 2010;115(4):906–909. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-212274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Alitalo A, Detmar M. Interaction of tumor cells and lymphatic vessels in cancer progression. Oncogene. 2012;31(42):4499–4508. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hayashi K, Jiang P, Yamauchi K, Yamamoto N, Tsuchiya H, Tomita K, Moossa AR, Bouvet M, Hoffman RM. Real-time imaging of tumor-cell shedding and trafficking in lymphatic channels. Cancer Res. 2007;67(17):8223–8228. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Padera TP, Kadambi A, di Tomaso E, Carreira CM, Brown EB, Boucher Y, Choi NC, Mathisen D, Wain J, Mark EJ, Munn LL, Jain RK. Lymphatic metastasis in the absence of functional intratumor lymphatics. Science. 2002;296(5574):1883–1886. doi: 10.1126/science.1071420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wang XL, Fang JP, Tang RY, Chen XM. Different significance between intratumoral and peritumoral lymphatic vessel density in gastric cancer: a retrospective study of 123 cases. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:299. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ji RC. Lymphatic endothelial cells, tumor lymphangiogenesis and metastasis: new insights into intratumoral and peritumoral lymphatics. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2006;25(4):677–694. doi: 10.1007/s10555-006-9026-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fukumura D, Jain RK. Tumor microenvironment abnormalities: causes, consequences, and strategies to normalize. J Cell Biochem. 2007;101(4):937–949. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kerjaschki D, Bago-Horvath Z, Rudas M, Sexl V, Schneckenleithner C, Wolbank S, Bartel G, Krieger S, Kalt R, Hantusch B, Keller T, Nagy-Bojarszky K, Huttary N, Raab I, Lackner K, Krautgasser K, Schachner H, Kaserer K, Rezar S, Madlener S, Vonach C, Davidovits A, Nosaka H, Hammerle M, Viola K, Dolznig H, Schreiber M, Nader A, Mikulits W, Gnant M, Hirakawa S, Detmar M, Alitalo K, Nijman S, Offner F, Maier TJ, Steinhilber D, Krupitza G. Lipoxygenase mediates invasion of intrametastatic lymphatic vessels and propagates lymph node metastasis of human mammary carcinoma xenografts in mouse. J Clin Investig. 2011;121(5):2000–2012. doi: 10.1172/JCI44751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Carmeliet P. VEGF as a key mediator of angiogenesis in cancer. Oncology. 2005;69(Suppl 3):4–10. doi: 10.1159/000088478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Greenberg JI, Cheresh DA. VEGF as an inhibitor of tumor vessel maturation: implications for cancer therapy. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2009;9(11):1347–1356. doi: 10.1517/14712590903208883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wu M, Frieboes HB, McDougall SR, Chaplain MA, Cristini V, Lowengrub J. The effect of interstitial pressure on tumor growth: coupling with the blood and lymphatic vascular systems. J Theor Biol. 2013;320:131–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2012.11.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Boucher Y, Jain RK. Microvascular pressure is the principal driving force for interstitial hypertension in solid tumors: implications for vascular collapse. Cancer Res. 1992;52(18):5110–5114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Isaka N, Padera TP, Hagendoorn J, Fukumura D, Jain RK. Peritumor lymphatics induced by vascular endothelial growth factor-C exhibit abnormal function. Cancer Res. 2004;64(13):4400–4404. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Proulx ST, Luciani P, Derzsi S, Rinderknecht M, Mumprecht V, Leroux JC, Detmar M. Quantitative imaging of lymphatic function with liposomal indocyanine green. Cancer Res. 2010;70(18):7053–7062. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ng CP, Hinz B, Swartz MA. Interstitial fluid flow induces myofibroblast differentiation and collagen alignment in vitro. J Cell Sci. 2005;118(Pt 20):4731–4739. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Provenzano PP, Inman DR, Eliceiri KW, Knittel JG, Yan L, Rueden CT, White JG, Keely PJ. Collagen density promotes mammary tumor initiation and progression. BMC Med. 2008;6:11. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-6-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Garmy-Susini B, Avraamides CJ, Schmid MC, Foubert P, Ellies LG, Barnes L, Feral C, Papayannopoulou T, Lowy A, Blair SL, Cheresh D, Ginsberg M, Varner JA. Integrin alpha4beta1 signaling is required for lymphangiogenesis and tumor metastasis. Cancer Res. 2010;70(8):3042–3051. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Stacker SA, Caesar C, Baldwin ME, Thornton GE, Williams RA, Prevo R, Jackson DG, Nishikawa S, Kubo H, Achen MG. VEGF-D promotes the metastatic spread of tumor cells via the lymphatics. Nat Med. 2001;7(2):186–191. doi: 10.1038/84635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.He Y, Rajantie I, Pajusola K, Jeltsch M, Holopainen T, Yla-Herttuala S, Harding T, Jooss K, Takahashi T, Alitalo K. Vascular endothelial cell growth factor receptor 3-mediated activation of lymphatic endothelium is crucial for tumor cell entry and spread via lymphatic vessels. Cancer Res. 2005;65(11):4739–4746. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Skobe M, Hawighorst T, Jackson DG, Prevo R, Janes L, Velasco P, Riccardi L, Alitalo K, Claffey K, Detmar M. Induction of tumor lymphangiogenesis by VEGF-C promotes breast cancer metastasis. Nat Med. 2001;7(2):192–198. doi: 10.1038/84643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Roberts N, Kloos B, Cassella M, Podgrabinska S, Persaud K, Wu Y, Pytowski B, Skobe M. Inhibition of VEGFR-3 activation with the antagonistic antibody more potently suppresses lymph node and distant metastases than inactivation of VEGFR-2. Cancer Res. 2006;66(5):2650–2657. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Laakkonen P, Waltari M, Holopainen T, Takahashi T, Pytowski B, Steiner P, Hicklin D, Persaud K, Tonra JR, Witte L, Alitalo K. Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3 is involved in tumor angiogenesis and growth. Cancer Res. 2007;67(2):593–599. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Norgall S, Papoutsi M, Rossler J, Schweigerer L, Wilting J, Weich HA. Elevated expression of VEGFR-3 in lymphatic endothelial cells from lymphangiomas. BMC Cancer. 2007;7:105. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Schoppmann SF, Birner P, Stockl J, Kalt R, Ullrich R, Caucig C, Kriehuber E, Nagy K, Alitalo K, Kerjaschki D. Tumor-associated macrophages express lymphatic endothelial growth factors and are related to peritumoral lymphangiogenesis. Am J Pathol. 2002;161(3):947–956. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64255-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Menon S, Beningo KA. Cancer cell invasion is enhanced by applied mechanical stimulation. PLoS One. 2011;6(2):e17277. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Witte MH, Bernas MJ, Martin CP, Witte CL. Lymphangiogenesis and lymphangiodysplasia: from molecular to clinical lymphology. Microsc Res Tech. 2001;55(2):122–145. doi: 10.1002/jemt.1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Radhakrishnan K, Rockson SG. The clinical spectrum of lymphatic disease. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2008;1131:155–184. doi: 10.1196/annals.1413.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Pfarr KM, Debrah AY, Specht S, Hoerauf A. Filariasis and lymphoedema. Parasit Immunol. 2009;31(11):664–672. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2009.01133.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Mellor RH, Stanton AW, Azarbod P, Sherman MD, Levick JR, Mortimer PS. Enhanced cutaneous lymphatic network in the forearms of women with postmastectomy oedema. J Vasc Res. 2000;37(6):501–512. doi: 10.1159/000054083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Loprinzi CL, Okuno S, Pisansky TM, Sterioff S, Gaffey TA, Morton RF. Postsurgical changes of the breast that mimic inflammatory breast carcinoma. Mayo Clinic Proc. 1996;71(6):552–555. doi: 10.4065/71.6.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Case T, Leis B, Witte M, Way D, Bernas M, Borgs P, Crandall C, Crandall R, Nagle R, Jamal S, et al. Vascular abnormalities in experimental and human lymphatic filariasis. Lymphology. 1991;24(4):174–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.WHO (2013) Lymphatic filariasis. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs102/en/. Accessed March 21 2013

- 106.Rockson SG. Lymphedema. Am J Med. 2001;110(4):288–295. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00727-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Goldman J, Conley KA, Raehl A, Bondy DM, Pytowski B, Swartz MA, Rutkowski JM, Jaroch DB, Ongstad EL. Regulation of lymphatic capillary regeneration by interstitial flow in skin. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292(5):H2176–H2183. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01011.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Harvey NL, Srinivasan RS, Dillard ME, Johnson NC, Witte MH, Boyd K, Sleeman MW, Oliver G. Lymphatic vascular defects promoted by Prox1 haploinsufficiency cause adult-onset obesity. Nat Genet. 2005;37(10):1072–1081. doi: 10.1038/ng1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Brorson H. From lymph to fat: liposuction as a treatment for complete reduction of lymphedema. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2012;11(1):10–19. doi: 10.1177/1534734612438550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Cormier JN, Rourke L, Crosby M, Chang D, Armer J. The surgical treatment of lymphedema: a systematic review of the contemporary literature (2004–2010) Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(2):642–651. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-2017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]