Abstract

Candida albicans represents one of the most prevalent species causing life-threatening fungal infections. Current treatments to defeat Candida albicans have become quite difficult, due to their toxic side effects and the emergence of resistant strains. Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) are fascinating molecules with a potential role as novel anti-infective agents. However, only a few studies have been performed on their efficacy towards the most virulent hyphal phenotype of this pathogen. The purpose of this work is to evaluate the anti-Candida activity of the N-terminal 1–18 fragment of the frog skin AMP esculentin-1b, Esc(1–18), under both in vitro and in vivo conditions using Caenorhabditis elegans as a simple host model for microbial infections. Our results demonstrate that Esc(1–18) caused a rapid reduction in the number of viable yeast cells and killing of the hyphal population. Esc(1–18) revealed a membrane perturbing effect which is likely the basis of its mode of action. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report showing the ability of a frog skin AMP-derived peptide (1) to kill both growing stages of Candida; (2) to promote survival of Candida-infected living organisms and (3) to inhibit transition of these fungal cells from the roundish yeast shape to the more dangerous hyphal form at sub-inhibitory concentrations.

Keywords: Antimicrobial peptide, Anti-Candida activity, Membrane permeabilization, Caenorhabditis elegans, Simple infection model

Introduction

Candida species are normally harmless commensals of the gastrointestinal and urinary tracts of human beings. However, under some circumstances, e.g., when the immune system is weakened or competing bacterial flora is eliminated following a broad-spectrum antibiotic treatment, Candida cells can invade host tissues and cause life-threatening infections. Invasive candidiasis is particularly common in intensive care units where mortality rates reach 45–49 % [1–4]. In North America, it is the fourth most common cause of hospital-acquired infections [5–7], with Candida albicans being the most prevalent species either in mucosal or systemic diseases [8, 9]. A striking feature of C. albicans biology is its ability to grow in different morphological forms that range from unicellular budding yeast, more suited for dissemination in the bloodstream [10–12], to the filamentous form (pseudo and true-hyphae) responsible for promoting tissue penetration and colonization [13–15]. The hyphal stage has often been considered essential for adhesion to mucosal surfaces and initiation of clinical infectious diseases [14, 16, 17]. Treatment of these infections with conventional antifungals, e.g., fluconazole and amphotericin B [18–21], is frequently ineffective. In addition, amphotericin B is toxic to the kidneys and hematopoietic and nervous systems [22, 23]. Therefore, the search for new anti-Candida compounds is critical [24], and naturally occurring antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) represent attractive candidates for the generation of new anti-mycotics. AMPs are produced by almost all unicellular and multicellular organisms and act as the first line of defense against noxious microorganisms [25–31]. The majority of these peptides are positively charged at neutral pH and with an amphiphatic character in a membrane-mimicking environment. These characteristics enhance selective binding and insertion of AMPs into microbial membranes, which are much richer in anionic phospholipids than mammalian cells [32, 33].

In view of the potential role of Candida dimorphism, the evaluation and understanding of the activity of new antifungal agents on the two morphological phenotypes of this pathogen can help in the development of better anti-Candida agents. To this aim, we performed an in-depth study on the activity and related molecular mechanism of the 1–18 fragment of the frog skin AMP esculentin-1b [Esc(1–18): GIFSKLAGKKLKNLLISG-NH2] [34], on the two forms of growth of C. albicans. Previous studies reported on the anti-Candida activity of the full 46-residue peptide esculentin-1 when tested in solid medium against the yeast form, and showed that it was only slightly higher than that of Esc(1–18) [35, 36]. Note that the 19–46 C-terminal tail of esculentin-1 has five basic residues that are neutralized by the four negatively charged amino acids located in this region. According to what was stated by Avrahami and Shai [37], this could assist in peptide assembly and partitioning into the fungal membrane. By contrast, no acidic residues are present in Esc(1–18), and its four positively charged amino acids are spread along the entire peptide sequence, presumably hampering the formation of peptide oligomers and their partition from the cell wall into the membrane. However, it is worth noting that the difference in the anti-Candida activity between Esc(1–18) and the full-length parental esculentin-1 is not very large [34, 35]. Furthermore, recent studies revealed a microbial membrane-perturbing activity of Esc(1–18) as one of the major mechanisms underlying its killing activity [38]. This should limit the induction of resistance to it, thus making the shorter-sized Esc(1–18) a more attractive candidate for further antifungal studies.

Importantly, experiments described in this work were carried out under both in vitro and in vivo conditions, using a simple model system, the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Historically, C. elegans has been of great value in many fields of biological research [39]. It is a differentiated multicellular organism with a nervous system, reproductive organs and digestive apparatus. Furthermore, it has a simple structure, a short life-cycle (< 3 days) and can be infected by different human pathogens (including Candida species) that can replace the regular Escherichia coli food source. Indeed, they can pass through the mouth, ultimately reaching the nematode’s gut [40]. Once the microbes start to proliferate, an infection process is initiated, which leads to the animal’s death. We have recently demonstrated that Esc(1–18) peptide is highly effective in promoting survival of C. elegans worms following infection by a multi-drug resistant strain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa [39]. Importantly, this peptide shows no toxicity towards mammalian cells, such as erythrocytes, lymphocytes [34, 38], macrophages and keratinocytes at microbicidal concentrations (Mangoni et al. unpublished data).

Results of the present study suggest that Esc(1–18) is an attractive membrane-perturbing anti-Candida AMP with the ability to block hyphal development, also in vivo.

Materials and methods

Materials

Synthetic all-l and all-d Esc(1–18) as well as the rhodamine-labelled form of the all-l peptide [rho-Esc(1–18)] were purchased from Selleck Chemicals (Houston, TX, USA). The purity of the peptides, their sequences and concentrations were determined as previously described [34]. Sytox Green was from molecular probes (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, U.S.A.); 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), and poly-l-lysine (150,000–300,000 mol wt) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). All other chemicals were reagent-grade.

Microorganisms and nematode strains

The following C. albicans strains were used: the reference ATCC 10231, ATCC 90028 and the clinical isolates C. albicans n. 1s and C. albicans n.1r. The wild-type C. elegans strain N2 was used in all experiments and propagated on nematode grow medium (NGM) plates containing E. coli OP50 as a food source [41]. C. albicans ATCC 10231 was used for all the experiments with C. elegans.

Anti-yeast activity

Susceptibility testing was performed by the microbroth dilution method, according to the procedures outlined by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (2001) using sterile 96-well plates according to [42]. Minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) was determined as the lowest peptide concentration at which 100 % inhibition of growth was observed after 18 h at 37 °C.

Peptide’s effect on the viability of yeast cells and hyphae

The peptide’s effect on the viability of both yeast and hyphal forms of C. albicans ATCC 10231 was determined by the MTT colorimetric method. In the first case, 100 μl of yeast cells suspension in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (NaPB), pH 7.4 (about 1 × 107 CFU/ml) were incubated at 37 °C with Esc(1–18) at different concentrations for 10, 20, 30 and 60 min. After incubation time with the peptide, samples were centrifuged and resuspended in 100 μl RPMI 1640 medium (Sigma) supplemented with 0.5 mg/ml MTT. After 2 h incubation at 37 °C, MTT formazan crystals were solubilized by adding 100 μl of 10 % sodium dodecyl sulphate. The absorbance at 590 nm of triplicate samples was measured spectrophotometrically with a microplate reader (Infinite M200; Tecan, Salzburg, Austria). Cell viability was expressed as percentage of survival with respect to the control (yeast cells not treated with the peptide) at the corresponding time intervals.

In the second case, RPMI supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine and 0.165 M morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (pH 7.0) was used as the hyphal growth-promoting (HP) medium [43, 44]. About 3 × 104 or 1 × 10 4 yeast-form cells in HP medium were transferred into wells of a 96-well flat-bottom poly-l-lysine-coated microplate and incubated for 3 h or a longer time (12 and 18 h) respectively, at 37 °C, as indicated in the Results section. The medium was then discarded and the adhesive Candida hyphae were treated with different concentrations of Esc(1–18) dissolved in NaPB, at 37 °C for different times. The peptide was then removed, 100 μl of MTT solution (0.5 mg/ml in HP medium) were added to each well and the plate was incubated at 37 °C for 4 h. Afterwards, formazan crystals were solubilized and their absorbance was measured as described above. The minimal fungicidal concentrations (MFC50 and MFC90) were defined as the minimal peptide concentrations causing a reduction in hyphae viability by 50 and 90 %, respectively, within 60 min, compared with the control.

Inhibition of hyphal development

Briefly, 100 μl of yeast suspension (1 × 106 CFU/ml) in Winge broth [45] were transferred into poly-l-lysine-coated wells of a 96-well plate and incubated at 37 °C for 3 h in the presence of different concentrations of Esc(1–18). The inhibition of hyphal development was visualized microscopically under an inverted microscope (Olympus CKX41) at ×40 magnification and photographed with a Color View II digital camera.

Membrane permeabilization

The ability of Esc(1–18) to alter the membrane permeability of fungal cells was assessed by the Sytox Green assay in microtiter plates, according to [46]. Briefly, 1 × 106 yeast cells or 3 h-grown hyphae obtained as described above were incubated in 95 μl of NaPB supplemented with 1 μM Sytox Green. After 20 min in the dark, 5 μl of peptide were added. The increase in fluorescence, owing to the binding of the dye to intracellular DNA, was measured at different times at 37 °C in the microplate reader (excitation and emission wavelengths were 485 and 535 nm, respectively).

Staining protocols: fluorescent probes for assessment of peptide’s distribution and fungal membrane integrity

To visualize, in a single preparation, the distribution of Esc(1–18) and to detect, at the same time, the membrane permeabilization induced by the peptide on yeast or hyphal forms of Candida, we used rho-Esc(1–18) and the two following fluorochromes: (1) the double-stranded DNA-binding dye DAPI, to stain the nuclei of all cells, and (2) the green fluorescent probe Sytox Green, to stain membrane perturbation. After exposure of yeast cells (1 × 107 CFU/ml in NaPB) to 16 μM rho-Esc(1–18) (100 μl as a final volume) for 30 min at 37 °C, the microbial suspension was centrifuged, washed with NaPB and incubated with 100 μl of 1 μM Sytox Green (in NaPB) for 15 min at room temperature. The sample was washed again and treated with 100 μl of DAPI solution (10 μg/ml in NaPB) for 15 min at room temperature [47]. Afterwards, yeast cells were resuspended in a drop of NaPB, poured onto a glass slide and examined by phase-contrast and fluorescence microscopy. Both phase-contrast and fluorescence images were recorded using the Olympus optical microscope equipped with an oil-immersion objective (×100).

In the case of hyphae, 96-well glass bottom microplates (MGB096-1-2-LG-L, Matrical Bioscience Spokane WA, USA) were used and coated with poly-l-lysine. About 3 × 104 yeast cells in HP medium were added to each single well and the plate was incubated at 37 °C for 3 h to permit hyphal development. Afterwards, treatment with rho-Esc(1–18) and staining with Sytox Green and DAPI solutions were performed as described above. Finally, 50 μl of NaPB were added to each well prior microscope observation. In all cases, controls were run in the absence of peptide.

C. elegans infection

Freshly grown Candida cells were inoculated into 2 ml of yeast extract-peptone-dextrose (YPD) broth and grown overnight with agitation at 28 °C. Fungal lawns used for C. elegans infection assays were prepared by spreading 100 μl of the overnight culture (diluted 1:100 in distilled water) on brain heart infusion (BHI) agar plates. The plates were then incubated for approximately 20 h at 28 °C before being seeded with adult hermaphrodite nematodes from a synchronized culture grown at 16 °C [41]. About 100–200 worms were washed with M9 buffer [41] and placed in the middle of C. albicans lawns. The infection was performed at 25 °C for 20 min.

Worm survival assay

The infected worms were washed with M9 buffer to remove C. albicans cells from their surface. Twenty worms were then transferred into plates (3-cm diameter) containing 2 ml of liquid medium (79 % M9, 20 % BHI, 10 μg/ml cholesterol and 90 μg/ml kanamycin) according to [48]. The peptide was either added to the plates, or omitted as indicated. The plates were incubated at 25 °C and examined for worm survival after 24 h. Worms were considered to be dead if they did not respond to being touched by a platinum wire pick. Living nematodes maintain a sinusoidal shape, whereas dead nematodes appear as straight, rigid rods as the corpses become filled with fungal cells [49].

Peptide’s effect on the number of yeast cells and their switch to the hyphal form, within the nematode intestine

Twenty infected nematodes in triplicate were treated (or not treated in case of controls) with the peptide at 25 °C for 24 h. Afterwards, for each replicate, worms were broken with 50 μl of M9 buffer-1 % TritonX-100. Appropriate dilutions of whole-worm lysates were plated on YPD agar plates for colony counts. In parallel, to evaluate the effect of Esc(1–18) on the morphology of fungal cells, peptide-treated and untreated infected worms were mounted onto pads of 3 % agarose in M9 buffer supplemented with 20 mM sodium azide to paralyze them. Animals were then observed under a Zeiss AXIOVERT25 microscope and photographed with a Zeiss AxioCam camera using Axiovision 4.6 (Zeiss) software.

In another set of experiments, infected nematodes were treated with 25 μM rho-Esc(1–18) for 3 h and observed by fluorescence microscopy as reported above.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SD, and the Student’s test (GraphPad Prism 4.0 software) was used to determine the statistical significance between experimental groups. The difference was considered significant if the p value was < 0.05.

Results

In vitro studies

MIC determination

The activity of Esc(1–18) in inhibiting the growth of C. albicans yeast cells was evaluated using a standard inoculum of 3.5 × 104 CFU/ml. Note that the MIC was 4 μM against all the strains tested with the exception of C. albicans n.1r (Table 1), and that the same MIC value was obtained when samples were incubated at 28 °C instead of 37 °C (data not shown). The conventional antifungal amphotericin B was also included for comparison (Table 1). In our experiments C. albicans ATCC 10231 was selected as a representative strain to perform further additional studies, since it is a well-characterized standard strain with the ability to grow under both yeast and hyphal forms under the experimental conditions [50]. As most of the experiments described below required a higher number of yeast cells, i.e., 1 × 106 and 1 × 107 CFU/ml, such cell densities were also used as an inoculum to determine the MICs against the ATCC 10231 strain. They were found to be directly related to cell number: 16 and 64 μM, respectively.

Table 1.

Antimicrobial activity of Esc(1–18) and amphotericin B on different C. albicans strains

| MICa (μM) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | C. albicans ATCC 10231 | C. albicans ATCC 90028 | C. albicans n.1s | C. albicans n.1r |

| Esc(1–18) | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| Amphotericin B | 0.5 | 0.5 | 2 | 2 |

aThe reported MIC values are those obtained from at least three readings out of four independent measurements

Time kill on both yeast and hyphal forms

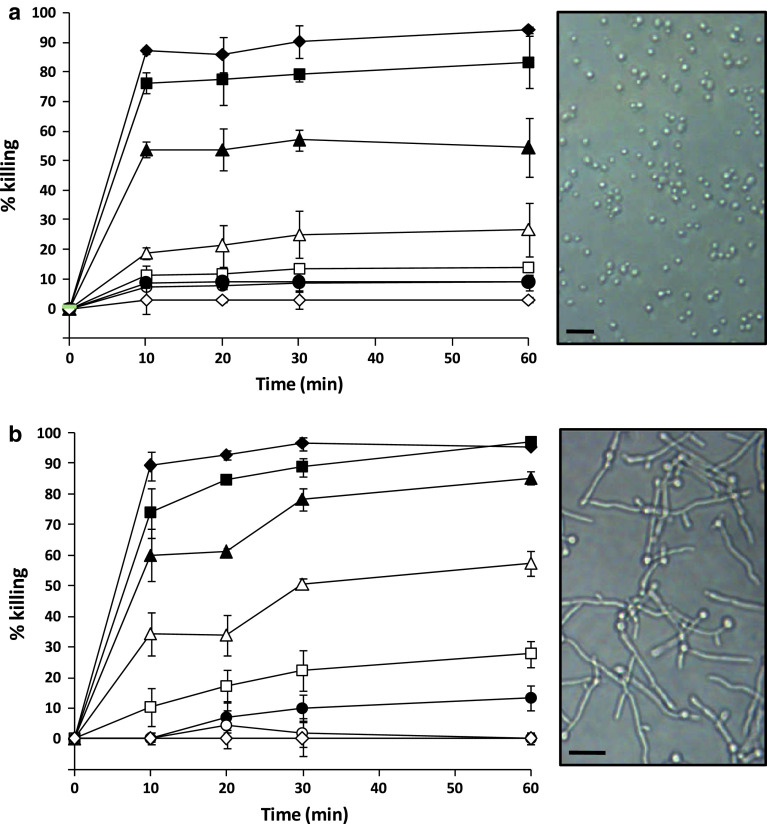

In order to confirm a fungicidal activity of Esc(1–18), a killing kinetics study with different peptide concentrations was first carried out on the yeast cells. A dose-dependent candidacidal activity was observed, with approximately 80 % reduction in cell survival within the first 20 min at 16 μM (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

Killing kinetic of Esc(1–18) on C. albicans ATCC 10231 yeast (panel a) and hyphal (panel b) cells in NaPB. Either yeast cells or 3 h-grown hyphae, were incubated at 37 °C with different peptide concentrations: 0.25 μM (unfilled diamond); 0.5 μM (unfilled circle); 1 μM (filled circle); 2 μM (unfilled square); 4 μM (unfilled triangle); 8 μM (filled triangle); 16 μM (filled square); 32 μM (filled diamond). Data points represent the mean of triplicate samples ± SD from a single experiment, representative of three independent experiments. The killing activity was determined with respect to the control at each time interval. Right insets show phase-contrast images of yeast and hyphal forms of Candida used for the experiments. Scale bars are 10 μm long

As found for the yeast cells, Esc(1–18) provoked about 80 % killing of 3 h-grown hyphae at 16 μM after 20 min from peptide addition (Fig. 1b), whereas approximately 90 % killing of hyphal population was recorded after a longer incubation time (60 min) at the same concentration of 16 μM (MFC90). Importantly, when hyphae were grown for 12 or 18 h instead of 3 h, a well-organized cellular community, named biofilm, was formed (Fig. 2 upper panels). Indeed, an inner layer containing microcolonies of yeast cells and an outer layer rich in pseudohyphae and hyphae were observed, according to the typical phenotype of Candida biofilm [51, 52]. Remarkably, the peptide’s efficacy was found to be only fourfold or eightfold lower, as indicated by the corresponding MFC50 and MFC90 on 12 or 18 h-grown biofilm, respectively, after 60 min of peptide treatment (Table 2). Phase-contrast images of Candida biofilm treated or not treated with the peptide at its MFC90, after MTT colorimetric assay, are reported in Fig. 2 (lower panels).

Fig. 2.

Phase-contrast images of Candida biofilm obtained after 12 and 18 h growth of yeast cells at 37 °C (upper panels). The peptide’s effect on the viability of 12 h-grown biofilm is shown after the MTT colorimetric assay (lower panels). The black color in the peptide-untreated (control) sample indicates viable cells, whereas the transparency in the peptide-treated sample indicates the presence of dead yeast and hyphal cells. Scale bar is 20 μm long

Table 2.

Fungicidal activity of Esc(1–18) on the biofilm form of C. albicans ATCC 10231

| Minimal fungicidal concentration (MFC, μM)a on C. albicans hyphae | ||

|---|---|---|

| 12 h growth | 18 h growth | |

| MFC50 | 16 | 32 |

| MFC90 | 64 | > 64 |

aThe reported MFC values are those obtained from at least three readings out of four independent measurements. MFC50 and MFC90 are defined as the minimal peptide concentrations causing 50 and 90 % fungal killing, respectively, within 60 min. Note that MFC50 and MFC90 on 3 h-grown hyphae are equal to 4 and 16 μM, respectively (see Fig. 1b)

Effect on membrane perturbation

The ability of Esc(1–18) to alter the membrane permeability of Candida cells was monitored by the intracellular influx of Sytox Green upon addition of the peptide to the cells. Esc(1–18) caused dose-dependent membrane damage, as supported by increased fluorescence signal at increasing peptide concentrations (Fig. 3a), with kinetics overlapping that of yeasts killing (Fig. 1a). Note that only a modest increase in fluorescence intensity was generated within the first 20 min after the addition of amphotericin B, even when used at a concentration up to 64-fold the MIC (data not shown). However, it gradually increased with time, reaching its maximum value, which was found to be identical to that obtained with 16 μM Esc(1–18), within 3 h. This finding is in agreement with the slower fungicidal activity (higher than 2–3 h, depending on the strain [53]) of this membrane-perturbing antifungal drug [54, 55] with respect to that of Esc(1–18). In line with what was obtained for the unicellular budding cells, Esc(1–18) disturbed the structural organization of the membrane of the filamentous form of Candida in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 3b) that directly correlates with its killing activity (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 3.

Peptide-induced membrane permeabilization of yeast cells (panel a) and 3 h-grown hyphae (panel b). Samples were incubated with 1 μM Sytox Green in NaPB. Once basal fluorescence reached a constant value, the peptide was added (arrow, t = 0) and changes in fluorescence were monitored. Peptide concentrations used are the following: 0.25 μM (unfilled diamond); 0.5 μM (unfilled circle); 1 μM (filled circle); 2 μM (unfilled square); 4 μM (unfilled triangle); 8 μM (filled triangle); 16 μM (filled square); 32 μM (filled diamond). Control (asterisk) is given by bacteria without peptide. Data points represent the mean of triplicate samples from a single experiment, representative of three independent experiments

Furthermore, to find out whether the peptide-induced membrane-perturbation was mediated by interaction with chiral components of the lipid membrane and/or recognition of specific targets, we also investigated the influx of Sytox Green into yeast and hyphal cells, upon their treatment with the all-d enantiomer of Esc(1–18), which was found to display the same MIC (4 μM) of the all-l isoform.

Interestingly, the all-D peptide showed similar ability to kill yeast and hyphal forms and to permeabilize their cell membrane as the L form (data not shown).

Fluorescence studies

To visualize the distribution of Esc(1–18) and its induced alteration of the cell membrane integrity, either yeast or hyphal forms were treated with 16 μM of rho-Esc(1–18), followed by DAPI and Sytox Green staining. We noted that rhodamine did not affect the anti-Candida activity of Esc(1–18), since the MIC value of rho-Esc(1–18) was equal to that of the unlabelled peptide (data not shown). As reported in Fig. 4, rho-Esc(1–18) appeared to be distributed evenly over the yeast cells and hyphae, and the membrane perturbation (as detected by the green fluorescence of Sytox Green) occurred in a similar manner along the entire cell structure.

Fig. 4.

Detection of peptide distribution and membrane perturbation in both yeast cells (upper panels) and hyphae (lower panels). Samples were treated with 16 μM of rho-Esc(1–18) and then stained with DAPI and Sytox Green. Afterwards, they were examined by light (a) and fluorescence microscopy (b–d). Blue (b); red (c) and green (d) fluorescence indicate the distribution of DAPI, the labelled-Esc(1–18) and Sytox-Green, respectively. Scale bars are 5 μm long and apply to all images

Inhibition of hyphae formation

It is largely known that the ability of a drug to prevent the morphological change of fungal cells from their budding shape into the filamentous form would be extremely advantageous. We therefore studied the capability of Esc(1–18) to block hyphal formation and found out that this effect was more pronounced when 1 × 106 CFU/ml were used. Indeed, a clear inhibition of germ tubes was detected after a 3 h treatment of yeast cells with sub-inhibitory concentrations of Esc(1–18) (Fig. 5). More precisely, the minimal peptide concentration causing such inhibition was found to be 4 μM, corresponding to 1/4 the MIC (16 μM with 1 × 106 CFU/ml). Importantly, this effect was maintained up to 24 h, despite the achieved high cell density, due to cell proliferation (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

Effect of Esc(1–18) on the development of the hyphal form of C. albicans after 3 h from peptide addition at different sub-MIC concentrations to yeast cells. Scale bar is 20 μm long and applies to all images

In vivo studies

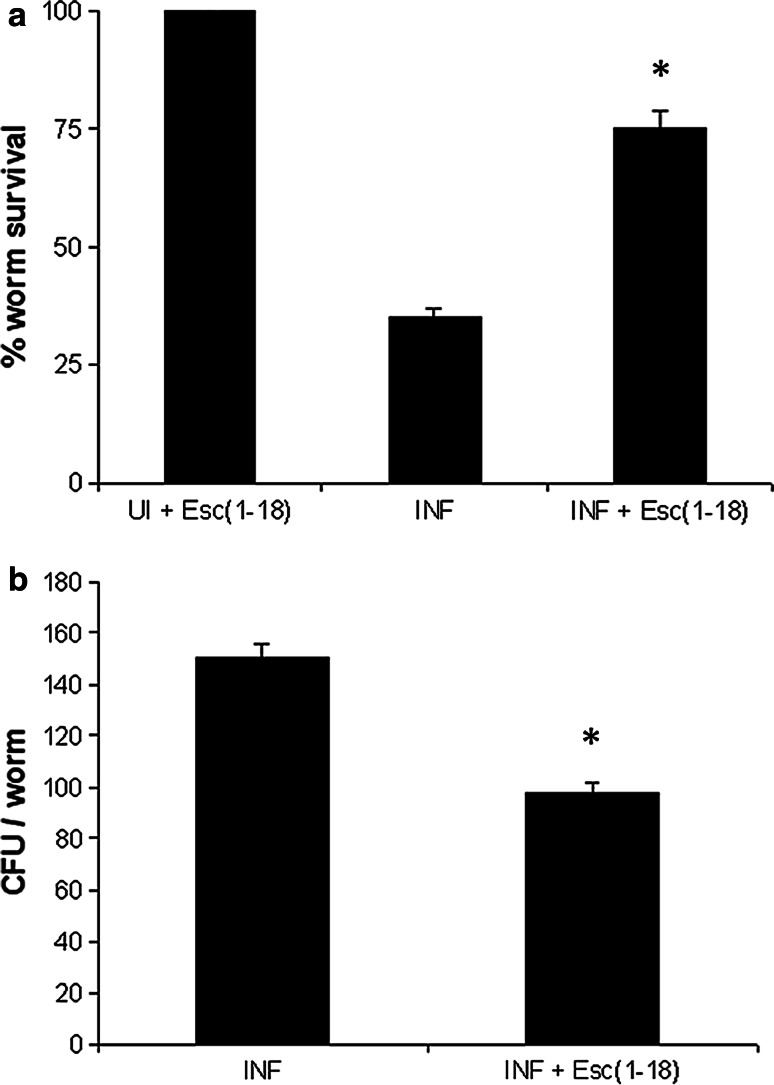

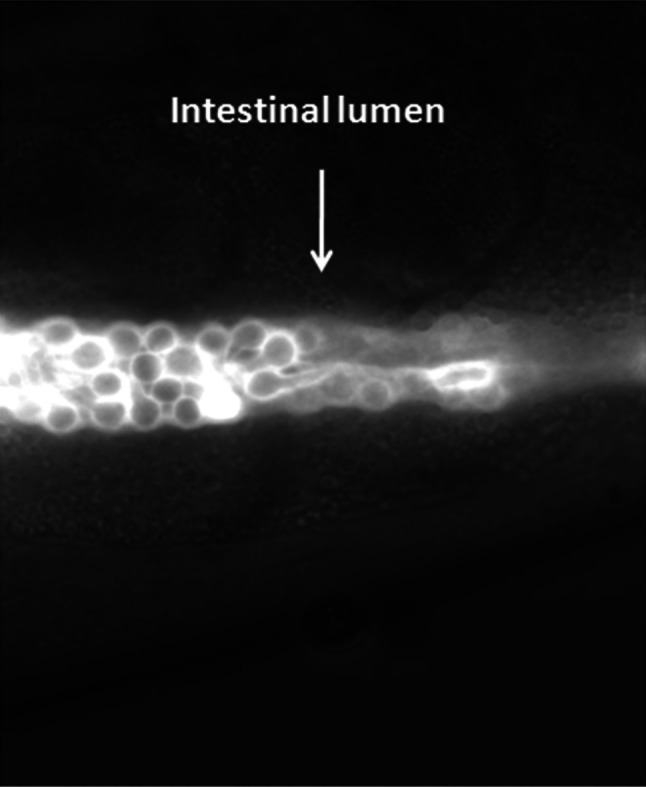

When infected wild-type nematodes were transferred to liquid medium (see experimental section), yeast cells underwent hyphal development, likely induced by environmental factors of the animal’s intestine. This usually results in a very aggressive infection leading to worm lethality in about 40 h. Indeed, hyphae penetrate and destroy the cuticle to finally pierce through the body. In our case, Esc(1–18) was added to the worms, at 50 μM, after 20 min of their exposure to Candida. Interestingly, the peptide increased C. elegans survival by more than 50 % within 24 h (Fig. 6a), causing approximately 40 % reduction in the number of CFU within the nematode’s intestine (Fig. 6b). In addition, in line with our in vitro results, Esc(1–18) dramatically hampered hyphae formation within the worm’s gut in 3 h (Fig. 7). In order to accurately assess the in vivo distribution of the peptide, the rho-Esc(1–18) analog was used. As illustrated in Fig. 8, the peptide was homogeneously confined to the worm’s intestinal lumen and uniformly associated with the cell perimeter of Candida cells.

Fig. 6.

Effect of Esc(1–18) on both the survival (panel a) and the number of live Candida cells within the gut (panel b) of infected nematodes after 24 h of peptide treatment [INF + Esc(1–18)] in comparison with untreated infected nematodes (INF). Control uninfected worms treated with the peptide [UI + Esc(1–18)] exhibited 100 % viability. Values represent the means of at least three independent experiments; the error bars indicate SD. *Indicates p < 0.05 compared to values from INF

Fig. 7.

Morphology of Candida cells within the gut of a representative infected animal, after 3 h of peptide treatment (T). A representative infected nematode not treated with the peptide (UT) is included for comparison. Arrows and corresponding insets at higher magnification indicate germ tube formation or yeast budding cells in the untreated or peptide-treated sample, respectively. Scale bar is 8 μm long

Fig. 8.

Fluorescence photomicrograph of a representative infected worm, 3 h after the addition of rho-Esc(1–18) at 25 °C. The red fluorescence (white in the photo) indicates the in vivo distribution of the labelled peptide

Discussion

C. albicans is a versatile microorganism that can become an important pathogen in superficial (e.g., oral and vaginitis) and systemic fungal infections [56]. Currently available antifungals are limited in both number and level of effectiveness, mainly due to their undesirable side effects and to the emergence of resistant strains [2, 57, 58]. For these reasons, novel anti-infective agents are of great interest to the medical community [59]. In this context, we have studied the anti-Candida properties of Esc(1–18) along with the underlying molecular mechanism.

Although a considerable amount of effort has been devoted to the study of the effect(s) of native and de novo designed AMPs on C. albicans (e.g. the human cathelicidins [60], piscidin [61], lactoferrin, istatins [62], lipopeptides [63], Leu/Lys-rich peptides [64], plant defensins [65, 66] temporins [42], pleurocidin [67] and synthetic dodecapeptides [68]), very little is known regarding their efficacy against the hyphal and biofilm forms of this microorganism [69], as well as the subtending mechanism of action. Remarkably, Candida biofilms are highly resistant to the action of conventional antifungal agents and very difficult to eradicate either from biological surfaces or implant devices [70]. Here, we have shown that Esc(1–18) displays a fast fungicidal activity (within 20 min), causing approximately 80 % reduction in the number of viable yeast/hyphal cells at 16 μM. Furthermore, a quite good fungicidal activity is exerted by the peptide on an intermediate developmental phase of C. albicans biofilm, produced after 12 and 18 h of cell growth. In addition, according to the results of the Sytox Green assay (Fig. 3), this peptide has a membrane-perturbing activity against both stages of Candida, despite their different membrane lipid composition [71, 72]. Overall, we can conclude that a direct peptide interaction with membrane lipids followed by membrane permeabilization is likely the primary cause of antifungal activity of Esc(1–18) and one that is probable to limit the emergence of fungal resistance. This conclusion is supported by the following findings: (1) a fast membrane perturbation process that is concomitant with the killing activity on the two morphological phenotypes; (2) a direct correlation between the extent of membrane damage and the percentage of microbial death; (3) the ability to cause release of fluorescent dyes entrapped in artificial phospholipid vesicles [38], which does not occur for those antifungal AMPs, e.g., plant defensins, provoking membrane perturbation in Candida as a final result of a mechanism of specific peptide-induced intracellular signaling pathways (e.g., involving the generation of reactive oxygen species, ROS) [65, 66, 73]; and (4) a non-significant production of ROS from Esc(1–18)-treated yeast and hyphal forms (data not shown), in contrast with plant defensins and what has recently been found for de novo designed low molecular weight cationic peptides [68]. Importantly, we can also exclude that the membrane perturbation is the consequence of a binding-site mediated insertion of Esc(1–18) into the fungal membrane, as in the case of the plant defensin RsAFP2 [74]. Indeed, such a stereospecific mechanism would likely not allow the all-l and all-d enantiomers of Esc(1–18) to achieve the same results, in terms of MIC, fungicidal activity and membrane perturbation.

As evidenced by fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 4), the membrane alteration appears to be distributed over the cell structure, ruling out a local peptide-induced membrane disruption. Moreover, the even distribution of the rho-Esc(1–18) along the hyphae excludes intracellular organelles (i.e., the nucleus and mitochondria) as its potential targets. Such an outcome is in contrast with what is manifested by other membrane-active AMPs, e.g., the fragment LL13–37 of the human cathelicidin LL-37, which was found to affect the membrane permeability of only some of the hyphae [75]. Interestingly, when tested on infected C. elegans, the frog skin Esc(1–18) is able to prolong worm survival by twofold within 24 h and to hinder hyphal development from the yeast form. Presumably, these findings are due to a direct effect of Esc(1–18) on Candida cells, reducing their number (Fig. 6b) and avoiding their shift to the more virulent and toxic phenotype (Fig. 7). This is consistent with the results obtained with the labelled peptide, showing: (1) the presence of Esc(1–18) exclusively along the worm’s gut, without diffusing to other tissues; and (2) its adhesion around the fungal cells, which mainly appear in their yeast budding form (Figs. 7b and 8). However, further experiments are required to better elucidate the in vivo mode(s) of action of Esc(1–18). In fact, we cannot leave out the possibility that additional processes, mediated by an enhanced host’s immune reaction, can contribute to increase survival of Candida-infected worms after peptide treatment. Crucial pathways controlling immune responses have been highly conserved throughout evolution, from nematodes to mammals [76], and the genome of C. elegans has been fully sequenced and annotated. Even if this mini-host model cannot substitute for mammalian models, it offers a number of advantages over vertebrates, including the study of strain collections without the ethical considerations associated with studies in mammals [40]. Note that Candida infection in C. elegans occurs through the gastrointestinal tract upon cell ingestion by the nematode [77], which is an accurate representation of what physiologically takes place in susceptible human hosts, where fungal cells in the intestinal mucosa can disseminate to other organs [78]. Conversely, in other simple invertebrate animal models, such as Drosophila, infection by Candida requires the injection of the yeast into the thorax. Another important benefit in using C. elegans is linked to the transparency of its body. Indeed, this makes it possible for researchers to directly examine and visualize in real time, under a dissecting microscope, yeast cell distribution within the host together with their change into hyphae, at all stages of infection. Overall, C. elegans can certainly provide an advanced step for a rapid and cost-effective high-throughput screening of in vivo anti-infective agents [79], as well as for identifying their location and their effect(s) on the outcome of the infection (e.g., amount of microbial cells and their form of growth). To the best of our knowledge, this report is the first to demonstrate: (1) the fungicidal activity and plausible mode of action of a frog skin AMP on the two cell shapes of C. albicans; (2) its ability to prolong survival of Candida-infected living multicellular organisms; and (3) its capability to inhibit transition from the roundish yeast cell to the more dangerous hyphal form at sub-MIC dosages, which is a very important finding for a rational design of new antifungal agents with more favorable properties. It is worthwhile underlining that transition of yeast cells to their filamentous form is a pivotal biological process required for biofilm formation in C. albicans. Finally, this paper highlights C. elegans as a convenient infection model to select anti-Candida compounds to be further investigated in more complex animal models for a future application in the treatment of candidiasis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from Sapienza Università di Roma. The authors thank Prof. Donatella Barra (University of Rome La Sapienza) and Dr. John P. Mayer (Indiana University, USA) for critical reading of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- AMP

Antimicrobial peptide

- CFU

Colony-forming units

- Esc(1–18)

Esculentin-1b(1–18)

- HP

Hyphal growth-promoting medium

- MH

Mueller-Hinton

- MFC

Minimal fungicidal concentration

- MIC

Minimal inhibitory concentration

- MTT

3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- NaPB

Sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4

- NGM

Nematode growth medium

- rho-Esc(1–18)

Rhodamine-labelled Esc(1–18)

Footnotes

V. Luca and M. Olivi equally contributed to the work.

Part of this work will be submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of a Ph.D degree at Sapienza University of Rome (by V.L.).

References

- 1.Leleu G, Aegerter P, Guidet B. Systemic candidiasis in intensive care units: a multicenter, matched-cohort study. J Crit Care. 2002;17:168–175. doi: 10.1053/jcrc.2002.35815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leroy O, Gangneux JP, Montravers P, Mira JP, Gouin F, Sollet JP, Carlet J, Reynes J, Rosenheim M, Regnier B, Lortholary O. Epidemiology, management, and risk factors for death of invasive Candida infections in critical care: a multicenter, prospective, observational study in France (2005–2006) Crit Care Med. 2009;37:1612–1618. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819efac0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alangaden GJ. Nosocomial fungal infections: epidemiology, infection control, and prevention. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2011;25:201–225. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bajwa S, Kulshrestha A. Fungal infections in intensive care unit: challenges in diagnosis and management. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2013;3:238–244. doi: 10.4103/2141-9248.113669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kao AS, Brandt ME, Pruitt WR, Conn LA, Perkins BA, Stephens DS, Baughman WS, Reingold AL, Rothrock GA, Pfaller MA, Pinner RW, Hajjeh RA. The epidemiology of candidemia in two United States cities: results of a population-based active surveillance. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:1164–1170. doi: 10.1086/313450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klotz SA, Chasin BS, Powell B, Gaur NK, Lipke PN. Polymicrobial bloodstream infections involving Candida species: analysis of patients and review of the literature. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;59:401–406. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lockhart SR, Iqbal N, Cleveland AA, Farley MM, Harrison LH, Bolden CB, Baughman W, Stein B, Hollick R, Park BJ, Chiller T. Species identification and antifungal susceptibility testing of Candida bloodstream isolates from population-based surveillance studies in two US cities from 2008 to 2011. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:3435–3442. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01283-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sudbery P, Gow N, Berman J. The distinct morphogenic states of Candida albicans . Trends Microbiol. 2004;12:317–324. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maganti H, Yamamura D, Xu J. Prevalent nosocomial clusters among causative agents for candidemia in Hamilton, Canada. Med Mycol. 2011;49:530–538. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2010.547880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gow NA, Brown AJ, Odds FC. Fungal morphogenesis and host invasion. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2002;5:366–371. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5274(02)00338-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saville SP, Lazzell AL, Monteagudo C, Lopez-Ribot JL. Engineered control of cell morphology in vivo reveals distinct roles for yeast and filamentous forms of Candida albicans during infection. Eukaryot Cell. 2003;2:1053–1060. doi: 10.1128/EC.2.5.1053-1060.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang G. Regulation of phenotypic transitions in the fungal pathogen Candida albicans . Virulence. 2012;3:251–261. doi: 10.4161/viru.20010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumamoto CA, Vinces MD. Contributions of hyphae and hypha-co-regulated genes to Candida albicans virulence. Cell Microbiol. 2005;7:1546–1554. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berman J. Morphogenesis and cell cycle progression in Candida albicans . Curr Opin Microbiol. 2006;9:595–601. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sudbery PE. Growth of Candida albicans hyphae. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9:737–748. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Odds FC. Candida infections: an overview. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1987;15:1–5. doi: 10.3109/10408418709104444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berman J, Sudbery PE. Candida albicans: a molecular revolution built on lessons from budding yeast. Nat Rev Genet. 2002;3:918–930. doi: 10.1038/nrg948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.White TC, Marr KA, Bowden RA. Clinical, cellular, and molecular factors that contribute to antifungal drug resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:382–402. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.2.382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prasad R, Kapoor K. Multidrug resistance in yeast Candida . Int Rev Cytol. 2005;242:215–248. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(04)42005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cannon RD, Lamping E, Holmes AR, Niimi K, Tanabe K, Niimi M, Monk BC. Candida albicans drug resistance another way to cope with stress. Microbiology. 2007;153:3211–3217. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/010405-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramirez E, Garcia-Rodriguez J, Borobia AM, Ortega JM, Lei S, Barrios-Fernandez A, Sanchez M, Carcas AJ, Herrero A, de la Puente JM, Frias J. Use of antifungal agents in pediatric and adult high-risk areas. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;31:337–347. doi: 10.1007/s10096-011-1315-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kinsky SC. Antibiotic interaction with model membranes. Annu Rev Pharmacol. 1970;10:119–142. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.10.040170.001003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lanternier F, Lortholary O. Liposomal amphotericin B: what is its role in 2008? Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008;14:71–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.01984.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Georgopapadakou NH, Walsh TJ. Human mycoses: drugs and targets for emerging pathogens. Science. 1994;264:371–373. doi: 10.1126/science.8153622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hancock RE. Cationic peptides: effectors in innate immunity and novel antimicrobials. Lancet Infect Dis. 2001;1:156–164. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(01)00092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boman HG. Antibacterial peptides: basic facts and emerging concepts. J Intern Med. 2003;254:197–215. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2003.01228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beisswenger C, Bals R. Functions of antimicrobial peptides in host defense and immunity. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2005;6:255–264. doi: 10.2174/1389203054065428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mangoni ML, Saugar JM, Dellisanti M, Barra D, Simmaco M, Rivas L. Temporins, small antimicrobial peptides with leishmanicidal activity. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:984–990. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410795200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mookherjee N, Rehaume LM, Hancock RE. Cathelicidins and functional analogues as antisepsis molecules. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2007;11:993–1004. doi: 10.1517/14728222.11.8.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mookherjee N, Hancock RE. Cationic host defence peptides: innate immune regulatory peptides as a novel approach for treating infections. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:922–933. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-6475-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yeung AT, Gellatly SL, Hancock RE. Multifunctional cationic host defence peptides and their clinical applications. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68:2161–2176. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0710-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shai Y. Mode of action of membrane active antimicrobial peptides. Biopolymers. 2002;66:236–248. doi: 10.1002/bip.10260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mangoni ML. Host-defense peptides: from biology to therapeutic strategies. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68:2157–2159. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0709-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mangoni ML, Fiocco D, Mignogna G, Barra D, Simmaco M. Functional characterisation of the 1–18 fragment of esculentin-1b, an antimicrobial peptide from Rana esculenta . Peptides. 2003;24:1771–1777. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2003.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simmaco M, Mignogna G, Barra D, Bossa F. Antimicrobial peptides from skin secretions of Rana esculenta. Molecular cloning of cDNAs encoding esculentin and brevinins and isolation of new active peptides. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:11956–11961. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ponti D, Mignogna G, Mangoni ML, De Biase D, Simmaco M, Barra D. Expression and activity of cyclic and linear analogues of esculentin-1, an anti-microbial peptide from amphibian skin. Eur J Biochem. 1999;263:921–927. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Avrahami D, Shai Y. A new group of antifungal and antibacterial lipopeptides derived from non-membrane active peptides conjugated to palmitic acid. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:12277–12285. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312260200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marcellini L, Borro M, Gentile G, Rinaldi AC, Stella L, Aimola P, Barra D, Mangoni ML. Esculentin-1b(1–18)–a membrane-active antimicrobial peptide that synergizes with antibiotics and modifies the expression level of a limited number of proteins in Escherichia coli . FEBS J. 2009;276:5647–5664. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Uccelletti D, Zanni E, Marcellini L, Palleschi C, Barra D, Mangoni ML. Anti-Pseudomonas activity of frog skin antimicrobial peptides in a Caenorhabditis elegans infection model: a plausible mode of action in vitro and in vivo. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:3853–3860. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00154-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marsh EK, May RC. Caenorhabditis elegans, a model organism for investigating immunity. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:2075–2081. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07486-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stiernagel T (2006) Maintenance of C. elegans, Wormbook, ed. The C. elegans Research Community, Wormbook. doi:10.895/wormbook.1.101.1. http://www.wormbook.org 11 Feb 2006

- 42.Grieco P, Carotenuto A, Auriemma L, Saviello MR, Campiglia P, Gomez-Monterrey IM, Marcellini L, Luca V, Barra D, Novellino E, Mangoni ML. The effect of d-amino acid substitution on the selectivity of temporin L towards target cells: identification of a potent anti-Candida peptide. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1828:652–660. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2012.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hawser S, Francolini M, Islam K. The effects of antifungal agents on the morphogenetic transformation by Candida albicans in vitro. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996;38:579–587. doi: 10.1093/jac/38.4.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cleary IA, Reinhard SM, Miller CL, Murdoch C, Thornhill MH, Lazzell AL, Monteagudo C, Thomas DP, Saville SP. Candida albicans adhesin Als3p is dispensable for virulence in the mouse model of disseminated candidiasis. Microbiology. 2011;157:1806–1815. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.046326-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Valenti P, Visca P, Antonini G, Orsi N. Antifungal activity of ovotransferrin towards genus Candida . Mycopathologia. 1985;89:169–175. doi: 10.1007/BF00447027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Luca V, Stringaro A, Colone M, Pini A, Mangoni ML. Esculentin(1–21), an amphibian skin membrane-active peptide with potent activity on both planktonic and biofilm cells of the bacterial pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa . Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70:2773–2786. doi: 10.1007/s00018-013-1291-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mangoni ML, Papo N, Barra D, Simmaco M, Bozzi A, Di Giulio A, Rinaldi AC. Effects of the antimicrobial peptide temporin L on cell morphology, membrane permeability and viability of Escherichia coli . Biochem J. 2004;380:859–865. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Breger J, Fuchs BB, Aperis G, Moy TI, Ausubel FM, Mylonakis E. Antifungal chemical compounds identified using a C. elegans pathogenicity assay. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e18. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moy TI, Ball AR, Anklesaria Z, Casadei G, Lewis K, Ausubel FM. Identification of novel antimicrobials using a live-animal infection model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:10414–10419. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604055103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chevalier M, Medioni E, Precheur I. Inhibition of Candida albicans yeast-hyphal transition and biofilm formation by Solidago virgaurea water extracts. J Med Microbiol. 2012;61:1016–1022. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.041699-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Douglas LJ. Candida biofilms and their role in infection. Trends Microbiol. 2003;11:30–36. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(02)00002-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jabra-Rizk MA, Falkler WA, Meiller TF. Fungal biofilms and drug resistance. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:14–19. doi: 10.3201/eid1001.030119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Canton E, Peman J, Gobernado M, Viudes A, Espinel-Ingroff A. Patterns of amphotericin B killing kinetics against seven Candida species. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:2477–2482. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.7.2477-2482.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hong SY, Oh JE, Lee KH. In vitro antifungal activity and cytotoxicity of a novel membrane-active peptide. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1704–1707. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.7.1704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Younsi M, Ramanandraibe E, Bonaly R, Donner M, Coulon J. Amphotericin B resistance and membrane fluidity in Kluyveromyces lactis strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:1911–1916. doi: 10.1128/AAC.44.7.1911-1916.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mayer FL, Wilson D, Hube B. Candida albicans pathogenicity mechanisms. Virulence. 2013;4:119–128. doi: 10.4161/viru.22913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kuriyama T, Williams DW, Bagg J, Coulter WA, Ready D, Lewis MA. In vitro susceptibility of oral Candida to seven antifungal agents. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2005;20:349–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302X.2005.00236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pfaller MA, Boyken L, Hollis RJ, Messer SA, Tendolkar S, Diekema DJ. In vitro activities of anidulafungin against more than 2,500 clinical isolates of Candida spp., including 315 isolates resistant to fluconazole. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:5425–5427. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.11.5425-5427.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kontoyiannis DP, Lewis RE. Antifungal drug resistance of pathogenic fungi. Lancet. 2002;359:1135–1144. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08162-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Benincasa M, Scocchi M, Pacor S, Tossi A, Nobili D, Basaglia G, Busetti M, Gennaro R. Fungicidal activity of five cathelicidin peptides against clinically isolated yeasts. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006;58:950–959. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sung WS, Lee J, Lee DG. Fungicidal effect and the mode of action of piscidin 2 derived from hybrid striped bass. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;371:551–555. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.04.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.den Hertog AL, van Marle J, van Veen HA, Van’t Hof W, Bolscher JG, Veerman EC, Nieuw Amerongen AV. Candidacidal effects of two antimicrobial peptides: histatin 5 causes small membrane defects, but LL-37 causes massive disruption of the cell membrane. Biochem J. 2005;388:689–695. doi: 10.1042/BJ20042099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Makovitzki A, Avrahami D, Shai Y. Ultrashort antibacterial and antifungal lipopeptides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:15997–16002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606129103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang P, Nan YH, Shin SY. Candidacidal mechanism of a Leu/Lys-rich alpha-helical amphipathic model antimicrobial peptide and its diastereomer composed of d, l-amino acids. J Pept Sci. 2010;16:601–606. doi: 10.1002/psc.1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Aerts AM, Francois IE, Meert EM, Li QT, Cammue BP, Thevissen K. The antifungal activity of RsAFP2, a plant defensin from raphanus sativus, involves the induction of reactive oxygen species in Candida albicans . J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;13:243–247. doi: 10.1159/000104753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Thevissen K, de Mello Tavares P, Xu D, Blankenship J, Vandenbosch D, Idkowiak-Baldys J, Govaert G, Bink A, Rozental S, de Groot PW, Davis TR, Kumamoto CA, Vargas G, Nimrichter L, Coenye T, Mitchell A, Roemer T, Hannun YA, Cammue BP. The plant defensin RsAFP2 induces cell wall stress, septin mislocalization and accumulation of ceramides in Candida albicans . Mol Microbiol. 2012;84:166–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08017.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Choi H, Lee DG (2013) The influence of the N-terminal region of antimicrobial peptide pleurocidin on fungal apoptosis. J Microbiol Biotechnol [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 68.Maurya IK, Thota CK, Sharma J, Tupe SG, Chaudhary P, Singh MK, Thakur IS, Deshpande M, Prasad R, Chauhan VS. Mechanism of action of novel synthetic dodecapeptides against Candida albicans . Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1830:5193–5203. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gow NA, van de Veerdonk FL, Brown AJ, Netea MG. Candida albicans morphogenesis and host defence: discriminating invasion from colonization. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;10:112–122. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Baillie GS, Douglas LJ. Matrix polymers of Candida biofilms and their possible role in biofilm resistance to antifungal agents. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2000;46:397–403. doi: 10.1093/jac/46.3.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ghannoum MA, Janini G, Khamis L, Radwan SS. Dimorphism-associated variations in the lipid composition of Candida albicans . J Gen Microbiol. 1986;132:2367–2375. doi: 10.1099/00221287-132-8-2367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hitchcock CA, Barrett-Bee KJ, Russell NJ. The lipid composition and permeability to the triazole antifungal antibiotic ICI 153066 of serum-grown mycelial cultures of Candida albicans . J Gen Microbiol. 1989;135:1949–1955. doi: 10.1099/00221287-135-7-1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Thevissen K, Osborn RW, Acland DP, Broekaert WF. Specific, high affinity binding sites for an antifungal plant defensin on Neurospora crassa hyphae and microsomal membranes. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:32176–32181. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.51.32176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Thevissen K, Terras FR, Broekaert WF. Permeabilization of fungal membranes by plant defensins inhibits fungal growth. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:5451–5458. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.12.5451-5458.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wong JH, Ng TB, Legowska A, Rolka K, Hui M, Cho CH. Antifungal action of human cathelicidin fragment (LL13–37) on Candida albicans . Peptides. 2011;32:1996–2002. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2011.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ewbank JJ, Zugasti O. C. elegans: model host and tool for antimicrobial drug discovery. Dis Model Mech. 2011;4:300–304. doi: 10.1242/dmm.006684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pukkila-Worley R, Peleg AY, Tampakakis E, Mylonakis E. Candida albicans hyphal formation and virulence assessed using a Caenorhabditis elegans infection model. Eukaryot Cell. 2009;8:1750–1758. doi: 10.1128/EC.00163-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pukkila-Worley R, Ausubel FM, Mylonakis E. Candida albicans infection of Caenorhabditis elegans induces antifungal immune defenses. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002074. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Coleman JJ, Ghosh S, Okoli I, Mylonakis E. Antifungal activity of microbial secondary metabolites. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25321. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]