Abstract

We summarize updated information about DNA microarray-based gene expression profiling by focusing on its application to estrogenic chemicals. First, estrogenic chemicals, including natural/industrial estrogens and phytoestrogens, and the methods for detection and evaluation of estrogenic chemicals were overviewed along with a comprehensive list of estrogenic chemicals of natural or industrial origin. Second, gene expression profiling of chemicals using a focused microarray containing estrogen-responsive genes is summarized. Third, silent estrogens, a new type of estrogenic chemicals characterized by their estrogenic gene expression profiles without growth stimulative or inhibitory effects, have been identified so far exclusively by DNA microarray assay. Lastly, the prospect of a microarray assay is discussed, including issues such as commercialization, future directions of applications and quality control methods.

Keywords: DNA microarray, Gene expression profiling, Estrogen, Phytoestrogen, Focused microarray, Signal transduction

Introduction

Expression profiling of estrogen-responsive genes

Almost 2 decades have passed since the first report of a miniaturized, high-throughput DNA microarray for gene expression profiling [1], and a number of DNA microarray-based applications, including for diagnostic use, have been developed [2–4]. A DNA microarray is a collection of DNA spots containing picomoles of DNA with specific sequences attached to a solid surface to measure the expression levels of a number of genes simultaneously (gene expression profiling) or to genotype multiple regions of a genome (genotyping). There are two major classes of applications of DNA microarrays for gene expression analyses: screening of a gene or a set of genes for further use, and profiling of phenomes, such as genetic phenotypes, diseases, responses to chemicals and clinical annotations, by means of gene expressions [5]. For the latter use, a focused microarray, a DNA microarray containing a limited set of genes for a specific purpose, would be desirable because statistical significance established by a set of reliable genes but not by their functional importance needs only a limited number of genes, generally about a hundred. Such sets of genes, collectively called a signature or a module, have been identified for various applications including cancer diagnosis and risk assessment of chemicals as they are the fields having a profound impact on people’s lives. For example, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved DNA microarrays as in vitro diagnostic devices for predicting breast cancer risks [6] and typing cancer of unknown origins [7]. Meanwhile, it has become an urgent issue to develop in vitro assay systems for the risk assessment of chemicals because of increased emphasis on the safety management of commercial chemicals and their products, such as manifested by REACH, a European Union Regulation, [8], and of intensive demands to replace animal tests for toxicity testing with pathway-based in vitro assays [9].

Xenoestrogens or exogenous estrogenic chemicals are considered as a major source of endocrine disruptors, a class of chemicals in the environment having the ability to disrupt human developmental and reproductive systems; therefore, they attracted extensive attention in the late 1990s. Since this timing coincided with the development of DNA microarrays, their application for screening and testing environmental chemicals became an immediate reality. Thus, while a high-throughput DNA microarray assay was not considered as a major method for detecting xenoestrogens in early 2004 [10], its promising future was discussed, especially as one of the key assays for the evaluation of xenoestrogens based on a mechanism and pathway-based system to connect transcriptomic information with genomic, proteomic and metabolomic information [11, 12].

Assays for detecting estrogenic activity

Several assays have been developed to detect estrogenic activity, and they are classified according to the molecular and cellular mechanisms of estrogen action: ligand-binding assay (ligand-receptor interaction), reporter-gene assay (receptor-DNA interaction), yeast two-hybrid assay (receptor-coactivator interaction), DNA microarray assay (comprehensive analysis of transcripts), enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; detection of gene products), proteomics analysis (comprehensive analysis of proteins), cell-growth assay and various animal tests including the life-cycle test and uterotrophic assay [11]. More recently, new techniques have been developed, such as those based on serial analysis of gene expression (SAGE) [13] and next-generation sequencing-based gene-expression profiling (RNA-Seq) [14], for comprehensive analysis of transcripts. These assays have advantages and disadvantages [10], and the most suitable assay should be selected by considering the time, cost, sensitivity, accuracy/reliability, safety/ethics and purpose. For example, while the ligand-binding assay is easy to perform, rapid and relatively cheap, it cannot give information about the accessibility of the ligand to its receptor within a cell; moreover, it is difficult to tell whether the ligand is an agonist or an antagonist. Importantly, although RNA-Seq gives mechanism-based information about transcripts within a cell, it is still too early to conclude that it can replace older technologies including DNA microarray-based gene expression profiling because, apart from its technical immaturity [15], no new pathways or markers applicable to diagnostics or toxicity testing have yet been found.

Estrogenic chemicals and phytoestrogens

A number of natural and synthetic chemicals are known to show weak to strong estrogenic activity [16]. Estrogenic activity includes anti-estrogenic activity or antagonistic activity against estrogen receptors (ERs) because of the presence of selective estrogen-receptor modulators (SERMs), a group of chemicals with agonistic or antagonistic activity depending on cell or tissue types [17], and because of the nature of the assay system; for example, the ligand binding assay cannot distinguish between agonists and antagonists but has been used to evaluate estrogenicity [11]. Phenolics and polyphenolics containing at least one phenol ring are abundantly present in the environment and food; thus, they are the sources of beneficial, toxicological and/or optionally endocrine-disrupting activities [18, 19]. Industrial phenolics, such as alkylphenols, bisphenols, chlorinated phenols, parabens, benzoylphenols and pharmaceutical phenolics (ethinylestradiol and diethylstilbestrol, for example), and natural phenolics, such as endogenous estrogens (estrone, estradiol and estriol), phytoestorgens and some mycotoxins (mycoestrogens), are known to show estrogenic activity [19–24] (summarized in Table 1). Phytoestrogens are plant-derived chemicals (phytochemicals) that can mimic estrogenic effects and thus are useful for hormone-replacement therapy [22], and they are characterized by their basic structure, such as a flavonoid, chalconoid, phenylpropanoid (stilbenes and lignans) or coumestan structure, which contains phenol rings. Mycoestrogens are a group of fungal metabolites with estrogenic activity and include zearalenone and α-zearalanol [25]. Hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives, such as caffeic acid and ferulic acid [26], and phenolic derivatives of terpenoids, such as glyceollin [27] and carnosol [28], also show estrogenic activity. On the other hand, some industrial chemicals having no phenolic/aromatic hydroxyl groups also show activity and include perfluorinated compounds [29]; pesticides and herbicides such as dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT), atrazine and endosulfan [23]; environmental pollutants such as dioxin, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and polybrominated biphenyls (PBBs) [23]; plasticizers such as phthalate esters [23]; pharmacological estrogens such as tamoxifen [17]; metalloestrogens, a class of inorganic xenoestrogens, such as metal/metalloid anions (arsenite, nitrite, selenite, and vanadate) and bivalent cationic metals (cadmium, calcium, cobalt, copper, nickel, chromium, lead, mercury and tin) [30]. Natural chemicals without a phenolic structure but with estrogenic activity include terpenoids, such as β-sitosterol [31], withaferin A [32] and ginsenoside Rg1 [33], and indoles, such as indole-3-carbinol [34] and melatonin [35]. Some of them may bind to ERs and/or other receptors, and others may show activity after modification or degradation within a cell, although most of the mechanisms have not been fully understood.

Table 1.

List of estrogenic chemicals

| Chemical | Reference | |

|---|---|---|

| Group | Example | |

| Phenolics with estrogenic activity | ||

| Industrial phenolics | ||

| Alkylphenols | Nonylphenol | Watanabe et al. [122] |

| Bisphenols | Bisphenol A | Koda et al. [123] |

| Chlorinated phenols | Pentachlorophenol | Terasaka et al. [53] |

| Parabens | Butylparaben | Routledge et al. [124] |

| Benzoylphenols | 2,4-DHBP, 2,2′,4,4′-THBP | Koda et al. [123] |

| Pharmaceutical phenolics | Ethinylestradiol | Koda et al. [123] |

| DES | Odum et al. [125] | |

| Natural phenolics | ||

| Endogenous estrogens | Estrone, estradiol, estriol | Hilf et al. [126] |

| Phytoestrogens and mycoestrogens | ||

| Flavonoids (flavonols/flavanones/flavones/isoflavones) | Genistein, daizein, biochanin A | Jefferson et al. [25] |

| Chalconoids (chalcones/dihydrochalcones) | Phloretin | Ise et al. [52] |

| Phenylpropanoids (stilbenes and lignans) | Resveratrol (a stilbene) | Ashby et al. [127] |

| Secoisolariciresinol (a lignan) | Saggar et al. [128] | |

| Coumestans | Coumestrol | Jefferson et al. [25] |

| Mycotoxins | Zearalenone, α-zearalanol | Jefferson et al. [25] |

| Other phytochemicals | ||

| Hydroxycinnamic acids (phenolic acids) | Caffeic acid, ferulic acid | Serafim et al. [26] |

| Phenolic terpenoids | Glyceollin | Ng et al. [27] |

| Carnosol | Johnson et al. [28] | |

| Estrogenic chemicals without a phenolic ring | ||

| Industrial chemicals | ||

| Perfluorinated compounds | PFOS, PFOA | Kjeldsen et al. [29] |

| Pesticides and herbicides | DDT | Bulger et al. [129] |

| Methoxychlor | Laws et al. [130] | |

| Environmental pollutants | TCDD | Hutz et al. [131] |

| PCBs | Salama et al. [132] | |

| Plasticizers (phthalate esters) | Dibutyl phthalate, butylbenzyl phthalate | Zacharewski et al. [133] |

| Pharmacological estrogens | Tamoxifen, toremifene | Carthew et al. [134] |

| Metalloestrogens (metal/metalloid anions and bivalent cationic metals) | Arsenite | Davey et al. [135] |

| Cadmium | Garcia-Morales et al. [136] | |

| Natural chemicals | ||

| Terpenoids | β-sitosterol (a sterol) | Orrego et at. [31] |

| Ginsenoside Rg1 (a saponin) | Shi et al. [33] | |

| Indoles | Indole-3-carbinol | Chen et al. [34] |

| Melatonin | Martínez-Campa et al. [35] | |

Only a few examples are shown for each chemical group. Note that not all chemicals in the groups listed have estrogenic activity. For more information including other examples of the above groups of chemicals, see [17, 19, 20, 22–24, 29, 30]

DDT dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, DES diethylstilbestrol; 2,4-DHBP 2,4-dihydroxybenzophenone, PCBs polychlorinated biphenyls, PFOA perfluorooctanoate, PFOS perfluorooctane sulfonate, TCDD 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin, 2,2′,4,4′-THBP 2,2′,4,4′-tetrahydroxybenzophenone

Gene expression profiling of estrogenic chemicals

Protocols for DNA microarray-based gene expression profiling

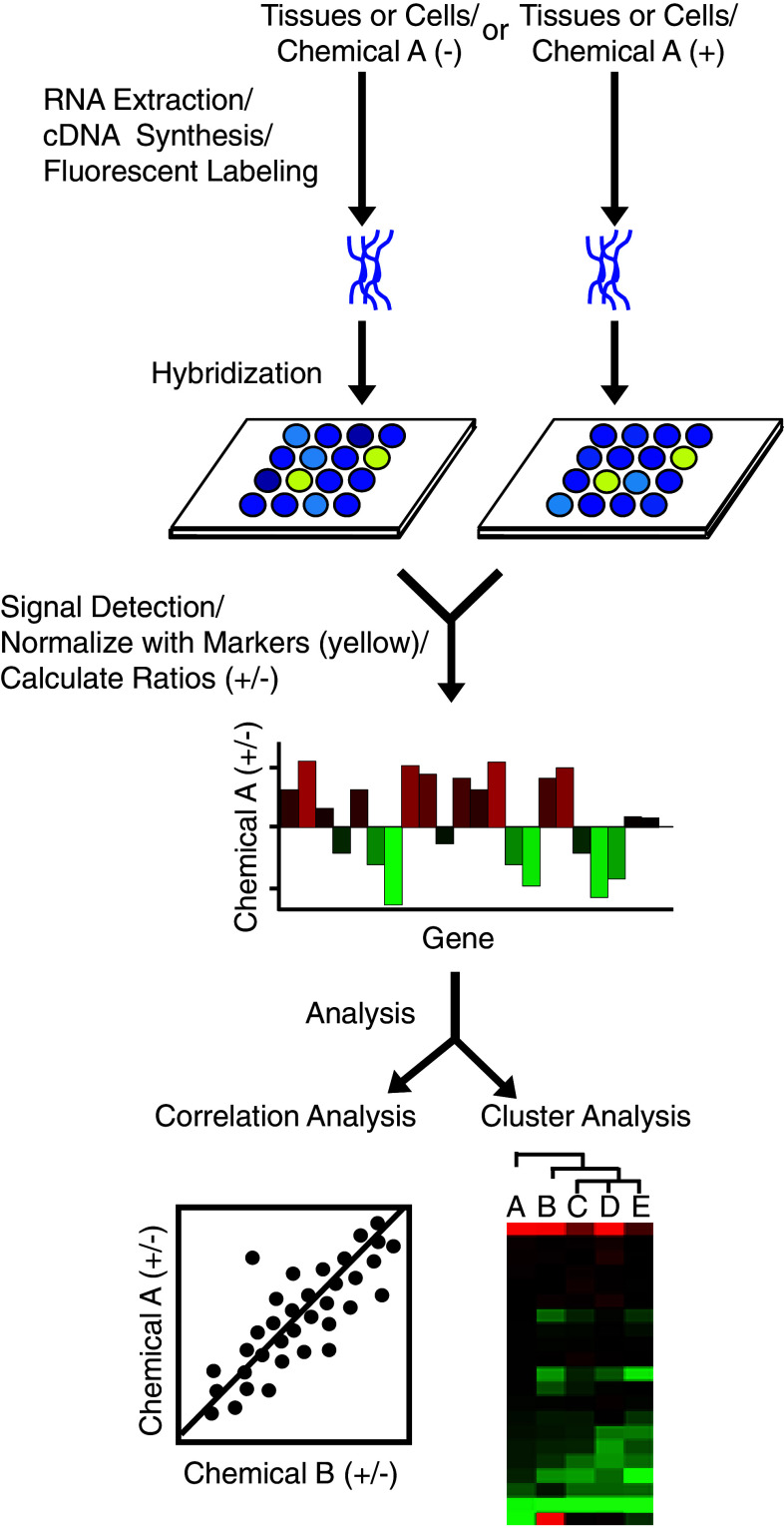

DNA microarray-based gene expression profiling for the evaluation of estrogenic chemicals has been reported by several groups [36–43]. However, only our group continued to develop a protocol for the profiling of estrogen-responsive gene expression by means of a focused microarray [44], and the protocol is run on two types of DNA microarray platforms: a cDNA microarray, named EstrArray, and an oligonucleotide-DNA (oligo-DNA) microarray, both containing a set of 172 estrogen-responsive genes and 31 markers [44, 45]. DNA microarray analysis was performed using a two-dye (for cDNA) or a single-dye (for oligo-DNA) approach. In the cDNA microarray assay, target cDNA was synthesized using mRNA extracted from the control or the test sample, labeled with different fluorescent dyes, and then two samples were mixed and hybridized with cDNA probes on a single microarray. In the oligo-DNA microarray assay, cDNA from the control and test samples was respectively labeled with the same fluorescent dye, such as Cy and Fluolid dyes [46], and used for hybridization with oligo-DNA probes on different DNA microarrays (summarized in Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Protocol of a single-dye DNA-microarray assay. For microarray assay, tissues or cells are treated with a chemical A or the vehicle (DMSO, control). Total RNA is isolated and used for cDNA synthesis. Target cDNA (control and test samples) is labeled with the same fluorescent dye and used for hybridization with the probes on the microarray. The signal intensity of each spot is detected and quantified by a fluorescent scanner. For data processing, the signal intensity is averaged among duplicated spots, and the ratio of the mean signal intensity for the test sample to that for the control is then calculated for each gene. The ratios of signal intensity for all genes are normalized against the mean ratio for the marker genes (yellow spots). Normalized values are used for correlation and/or cluster analyses

The signal intensity was averaged between duplicated spots and the ratio of the mean signal intensity for the test sample to that for the control sample was calculated for each gene. The ratios of the signal intensity for all genes were normalized against the mean ratio of the 28 calibration markers [44]. To analyze the relationship of gene expression between different chemicals, average-linkage hierarchical clustering was performed (cluster analysis) and/or correlation coefficients based on linear regression between the profiles was calculated (correlation analysis).

Genes used for monitoring estrogenic gene expression

It is crucial to use a set of appropriate genes to reliably monitor estrogenic gene expression attributable to a chemical. We screened a set of estrogen-responsive genes by profiling the gene expression in estrogen receptor-positive human MCF-7 breast cancer cells using two large-scale cDNA microarrays, a Human UniGEM v 2.0 microarray (IncyteGenomics) containing 9,128 genes and a GeneChip U95A (Affymetrix) containing 12,625 genes [42, 44]. After the reproducibility of the expression was confirmed by repeated cDNA microarray and/or RT-PCR assays, we constructed a customized DNA microarray, EstrArray, which contained 203 genes, including 108 upregulated and 64 downregulated genes, along with 28 calibration markers, which did not show any response to estrogen, and three functional markers [44]. Some have been reported to be estrogen inducible, such as TFF1 (or pS2; [47]), PDZK1 [48] and IGFBP4 [49]. However, many (119/172, 69 %) are not reported to have any relationship with estrogen, and, after our report about gene expression profiling [42], we and others further characterized estrogen-related functions for 65 genes (38 %), including EGR3 [50]; BSN and AREG [51]; and ATF3, TP53I11, SH3BP5 and TRIB3 [52].

Because genes with poor reliability may result in inaccurate profiling of the chemicals tested, it is important to select a set of highly reliable genes. Reducing the number of genes would result in less statistical stability to differentiate a variety of chemicals, especially when focusing on specific cellular functions. So, to select a set of genes with more statistical stability, ten sets of cDNA microarray data were statistically examined, and the correlation coefficients (R values) were compared between one assay and each of the other assays using sets of genes ranked by reproducibility or R values [53]. Among the sets of 203, 172, 150, 120, 90, 60 or 30 genes selected from the top of the rank, a set of 120 genes was adopted because it significantly improved the R value from the 150-gene set without losing much variability. The 120 genes selected were further classified into six tentative functional groups (enzyme, signaling, proliferation, transcription, transport and others), based on their annotations in the Entrez database [53]. The number in each functional group was 12–30, which was enough to maintain statistical stability. Likewise, a set of 150 genes was selected for the oligo-DNA microarray and was used to evaluate estrogen-like gene expression of the extract of Agaricus blazei (A. blazei), an edible mushroom originating from Brazil [45, 54], and C-heavy oil [55].

Gene expression profiling of estrogenic chemicals using estrogen-responsive genes

Using the focused microarray mentioned above, estrogenic gene-expression profiles of various chemicals, including natural/synthetic estrogens, industrial/environmental chemicals, phytochemicals and plant/fungus extracts, were examined (summarized in Table 2). The profiles obtained were compared with that of a natural estrogen, 17β-estradiol (E2), by examining the correlation coefficient (R value) between the profiles for each chemical and E2. Natural/synthetic estrogens, such as estrone, estriol and diethylstilbestrol, showed moderate to high levels of correlation. Phytoestrogens are a diverse group of plant-derived chemicals (phytochemicals) and, due to their structural similarities with E2, they have the ability to cause estrogenic and/or antiestrogenic effects. Among the examined phytoestrogens, such as isoflavones, flavonols and flavones, and mycotoxins, such as zearalenone, most showed moderate to high levels of correlation, except ipriflavone (R = 0.19) [52, 56]. In particular, genistein and five of a group of zearalenone and its analogs showed very high R values (R = 0.93–0.96), which were close to those of natural estrogens, such as estriol. Some were analyzed with a different type of breast cancer cell line, T-47D, and showed quite different gene expression profiles from those in MCF-7 [57], suggesting differences in signaling within cells.

Table 2.

Summary of the correlation of expression profiles between estrogen and chemicals revealed by DNA microarray assay

| Chemical | Cell line | R value | p value | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High correlation (R = 0.8–0.9) | ||||

| Zearalanone | MCF-7 | 0.96 | <0.01 | Parveen et al. [56] |

| Zearalenone | MCF-7 | 0.95 | <0.01 | Parveen et al. [56] |

| α-Zearalanol | MCF-7 | 0.95 | <0.01 | Parveen et al. [56] |

| β-Zearalanol | MCF-7 | 0.94 | <0.01 | Parveen et al. [56] |

| α-zearalenol | MCF-7 | 0.93 | <0.01 | Parveen et al. [56] |

| Bisphenol B | MCF-7 | 0.93 | <0.01 | Terasaka et al. [53] |

| Estriol | MCF-7 | 0.93 | Terasaka et al. [44] | |

| Genistein | MCF-7 | 0.93 | Ise et al. [52] | |

| p-Hydroxybenzophenone | MCF-7 | 0.92 | <0.01 | Terasaka et al. [53] |

| Genistein | MCF-7 | 0.91 | Terasaka et al. [44] | |

| Nonylphenol | MCF-7 | 0.90 | <0.01 | Terasaka et al. [53] |

| Bisphenol A | MCF-7 | 0.89 | <0.01 | Terasaka et al. [53] |

| C-heavy oil (TK09 W, 73d) | MCF-7 | 0.88 | Zhu et al. [55] | |

| Estrone | T-47D | 0.87 | <0.01 | Inoue et al. [57] |

| Diethylstilbestrol | T-47D | 0.87 | <0.01 | Inoue et al. [57] |

| Nonylphenol | MCF-7 | 0.86 | Terasaka et al. [44] | |

| Butylbenzyl phthalate | MCF-7 | 0.85 | <0.01 | Parveen et al. [58] |

| Estrone | MCF-7 | 0.85 | Terasaka et al. [44] | |

| Agaricus blazei extract | MCF-7 | 0.84 | <0.01 | Dong et al. [45] |

| Estriol | T-47D | 0.83 | <0.01 | Inoue et al. [57] |

| 4n-Heptylphenol | MCF-7 | 0.82 | <0.01 | Terasaka et al. [53] |

| β-Zearalenol | MCF-7 | 0.82 | <0.01 | Parveen et al. [56] |

| C-heavy oil (TK09 W, 101d) | MCF-7 | 0.82 | Zhu et al. [55] | |

| Medium correlation (R = 0.4–0.8) | ||||

| Biochanin A | MCF-7 | 0.79 | Ise et al. [52] | |

| Phloretin | MCF-7 | 0.78 | Ise et al. [52] | |

| 4-t-octylphenol | MCF-7 | 0.75 | <0.01 | Terasaka et al. [53] |

| Daidzein | MCF-7 | 0.74 | Ise et al. [52] | |

| Coumestrol | MCF-7 | 0.74 | Ise et al. [52] | |

| Propylparaben | MCF-7 | 0.74 | <0.01 | Terasaka et al. [53] |

| Bisphenol A | T-47D | 0.72 | <0.01 | Inoue et al. [57] |

| Naringenin | MCF-7 | 0.70 | Ise et al., 2005 [52] | |

| C-heavy oil (HP-7, 73d) | MCF-7 | 0.70 | Zhu et al. [55] | |

| Diethylstilbestrol | MCF-7 | 0.69 | Terasaka et al. [44] | |

| Kaempferol | MCF-7 | 0.68 | Ise et al. [52] | |

| Apigenin | MCF-7 | 0.67 | Ise et al. [52] | |

| Chrysin | MCF-7 | 0.66 | Ise et al. [52] | |

| Ginsenoside F1 | MCF-7 | 0.66 | <0.01 | Dong and Kiyama, 2009 [60] |

| Bisphenol A | MCF-7 | 0.65 | Terasaka et al. [44] | |

| Luteolin | MCF-7 | 0.64 | Ise et al. [52] | |

| Brefeldin A | MCF-7 | 0.61 | Dong et al. [54] | |

| Butylparaben | MCF-7 | 0.60 | <0.01 | Terasaka et al. [53] |

| Glycitein | MCF-7 | 0.59 | Ise et al. [52] | |

| C-heavy oil (TK09 W, 28d) | MCF-7 | 0.57 | Zhu et al. [55] | |

| Methoxychlor | MCF-7 | 0.56 | Terasaka et al. [44] | |

| Quercetin | MCF-7 | 0.53 | Ise et al. [52] | |

| Diethyl phthalate | MCF-7 | 0.52 | <0.01 | Parveen et al. [58] |

| Genistein | T-47D | 0.52 | <0.01 | Inoue et al. [57] |

| Diisopropyl phthalate | MCF-7 | 0.49 | <0.01 | Parveen et al. [58] |

| Nonylphenol | T-47D | 0.49 | <0.01 | Inoue et al. [57] |

| G. glabra root extract | MCF-7 | 0.47 | <0.01 | Dong et al. [59] |

| Low or no correlation (R < 0.4) | ||||

| 4-n-ethylphenol | MCF-7 | 0.39 | <0.01 | Terasaka et al. [53] |

| Ginsenoside Rb1 | MCF-7 | 0.38 | <0.01 | Dong and Kiyama [60] |

| Dibutyl phthalate | MCF-7 | 0.36 | <0.01 | Parveen et al. [58] |

| Pentachlorophenol | MCF-7 | 0.32 | <0.01 | Terasaka et al. [53] |

| 4-chloro-3,5-dimetylphenol | MCF-7 | 0.26 | <0.01 | Terasaka et al. [53] |

| Ginsenoside Rh1 | MCF-7 | 0.22 | 0.01–0.05 | Dong and Kiyama [60] |

| Ginsenoside Rg1 | MCF-7 | 0.21 | 0.01–0.05 | Dong and Kiyama [60] |

| Dioxin (TCDD) | MCF-7 | 0.21 | Terasaka et al. [44] | |

| C-heavy oil (control, 73d) | MCF-7 | 0.21 | Zhu et al. [55] | |

| Ipriflavone | MCF-7 | 0.19 | Ise et al. [52] | |

| Ethylparaben | MCF-7 | 0.19 | 0.01–0.05 | Terasaka et al. [53] |

| 4-chlorophenol | MCF-7 | 0.15 | >0.05 | Terasaka et al. [53] |

| p-cresol | MCF-7 | 0.12 | >0.05 | Terasaka et al. [53] |

| 2,4-dichlorophenol | MCF-7 | 0.03 | >0.05 | Terasaka et al. [53] |

| Methylparaben | MCF-7 | −0.21 | 0.01–0.05 | Terasaka et al. [53] |

| Glycyrrhizin | MCF-7 | No correlation | Dong et al. [59] | |

Data were reproduced from the references shown on the right. The gene expression profile of each chemical was obtained after either MCF-7 or T-47D cells had been treated with the chemical and compared with that of 17β-estradiol (E2) obtained from the same cell line. Coefficients of correlation (R values) between each chemical and E2 on the basis of linear regression and p values for the statistical significance of the correlation were calculated

A number of chemicals and their degradation products have structural similarities to natural estrogens, and thus, they could act as xenoestrogens such as endocrine disruptors. Some chemicals showed profiles similar to that of E2, such as nonylphenol (R = 0.86), bisphenol B (R = 0.93), p-hydroxybenzophenone (R = 0.92) and butylbenzyl phthalate (R = 0.85). On the other hand, the majority of the industrial chemicals examined showed only moderate (R = 0.4–0.8) or low (R < 0.4) correlations, such as 4-t-octylphenol (R = 0.75), methoxychlor (R = 0.56), diethyl phthalate (R = 0.52), dibutyl phthalate (R = 0.36), dioxin (R = 0.21) and p-cresol (R = 0.12) [44, 53, 58]. Furthermore, estrogenic gene-expression profiles were observed for bacterial-degradation products of C-heavy oil [55]. Oil samples, after they were cultured with complex microbes (TK07 W) or a single bacterial strain (HP-7) for a longer period of time (73 days), showed gene-expression profiles similar to that of E2 (R = 0.88 or 0.70, respectively), suggesting that components such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) could gain estrogenic activity during their degradation process.

We also examined estrogenic gene-expression profiles of several extracts/ingredients including two traditional Chinese medicinal herbs, licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra or G. glabra) [59] and ginseng [60]. While the profiles between E2 and the extract of G. glabra root showed moderate correlation (R = 0.47), one of the major components in the extract, glycyrrhizin, did not show any correlation with E2, suggesting the presence of other estrogenic components. Meanwhile, four components of ginseng had various degrees of estrogenic activity; ginsenosides F1 (R = 0.66), Rb1 (R = 0.38), Rg1 (R = 0.21) and Rh1 (R = 0.22) [60]. The extract of A. blazei was also examined, which showed a high estrogenic gene-expression profile (R = 0.84) [45]. A component of the activity was identified as brefeldin A (BFA) [54]. Since the correlation coefficient between the profiles of BFA and E2 (R = 0.61) was significant but apparently less than that for the extract of A. blazei, BFA would need additional components to stabilize and/or enhance the activity (see “Silent estrogens for medical use”). Many estrogenic phytochemicals show poor water solubility and thus need modifications, such as glycosidation, and/or interaction with appropriate carriers.

Global and focused microarrays

Microarray-based gene expression profiling can be categorized into two types of microarray systems, global (or genome wide) and focused microarrays. We previously discussed the characteristics of the analysis using focused microarrays [5]. Focused microarrays typically contain a set of tens to hundreds of genes as a molecular signature for characterizing a specific type of phenomes, and some have been developed for clinical use (see “Prospect of DNA microarray-based gene expression profiling”). The reliability or reproducibility of microarray data, especially those obtained with global microarrays, has been questioned by several groups including microarray developers (see Inoue et al. [5]) and statisticians/clinicians [61–63]. Ioannidis noted that microarray technology performs no better than flipping a coin or horoscopes [63]. Focused microarrays use limited numbers of genes selected and validated in advance for specific purposes, and the genes selected are mostly uncharacterized but are expected to be signal target genes and/or genes associated with signal cascades (see “Silent estrogens”). Focused microarrays may efficiently eliminate noise and identify the relationship between gene expression and the signaling status with less time and labor.

As described above (“Gene expression profiling of estrogenic chemicals using estrogen-responsive genes”), a focused microarray was applied for evaluation of estrogenic activity based on the expression profile of the genes responding to estrogen or estrogen-like chemicals. Among the chemicals tested, zearalenone and its analogs showed expression profiles identical to that of E2, while their structure was not particularly similar to that of E2 [56], suggesting that the microarray assay can be used for analyzing the structural basis of estrogenic activity. Even though some chemicals belong to a group based on their structure, they may show quite different expression profiles, such as phthalate esters and ginsenosides [58, 60], suggesting that structural characteristics other than a phenolic basis, such as the mass and hydrophobicity of side chains, are essential for estrogenic effects. Mixtures of compounds, such as those extracted from plants, the extract of G. glabra root for example, which showed moderate correlation with E2, can be analyzed, and the unique profile shown by a major component, glycyrrhizin, suggests that estrogen-responsive genes may respond differently from those of most estrogenic chemicals [59]. An important finding was that some chemicals showed differences between estrogenic cell proliferative effects and gene expression profiles: some chemicals have no positive effects on cell proliferation, but show estrogenic gene expression profiles (see “Silent estrogens”). Accordingly, focused microarrays could be an efficient method for evaluating various cellular activities and thus would be advantageous for analyzing natural or industrial chemicals and purifying chemicals from various extracts.

Silent estrogens

Signals for estrogen-induced cell proliferation

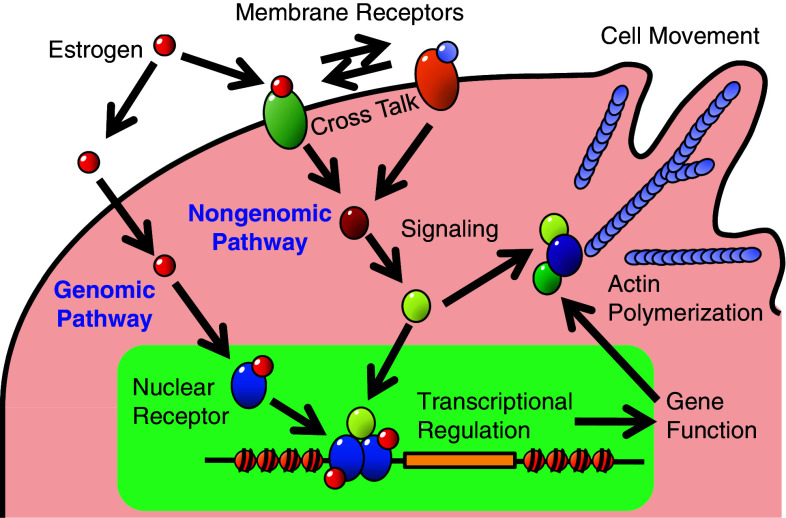

Cell proliferation is a state in which the number of cells is increased as a result of cell growth and cell division. Cell proliferation is stimulated by various chemicals such as mitogens, growth factors and survival factors [64], and specific receptors mediate the intracellular signals originating from these chemicals to regulate the timing and extent of protein synthesis, cell growth, cell division, cell movement and/or cell survival processes. Estrogen signals within a cell are initiated by specific receptors, estrogen receptors α or β (ERα or ERβ), or membrane receptors including a G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR), GPR30, and membrane-bound ERα/β, upon their binding to estrogen [65, 66]. ERα and ERβ show significant overall sequence homology, and both are composed of five domains, A/B, C, D, E and F [67]. Among them, the A/B and E domains are responsible for the activation functions, AF1 and AF2, respectively, to transactivate gene transcription in the absence (AF1) or presence (AF2) of bound ligands [68]. These domains regulate ER-mediated transactivation of target genes through the interaction with coactivators, and this process is collectively referred to as “the genomic pathway” (Fig. 2). A recent study suggested that AF1 of ERα is necessary and sufficient for estrogen-induced cell proliferation [69], although some beneficial estrogenic effects, such as atheroprotective effects, are attributable to AF2 but not AF1 [70].

Fig. 2.

Summary of the scheme of estrogenic response and cell signaling directing to cell functions. Actin polymerization and cell movement are representative

On the other hand, a class of specific signaling pathways, the so-called “nongenomic pathway” (Fig. 2), has been found in association with estrogen-induced cell proliferation, in which signals are mediated through protein modifications and protein–protein interactions, such as Src/JNK/MAPK [71], PI3 K/Akt [72, 73], MEK/ERK/RSK [74], Rac [75] and Wnt signaling [76]. As a result of the activation of these pathways, downstream targets, such as c-Myc, β-catenin, cyclins and Rho-family small GTPases, involved in cell proliferation, cell survival, cell movement and transcription, are activated [77, 78]. Note that such a non-genomic pathway can directly lead to gene expression without the interaction of ERs with gene promoters [79].

Activation of GPR30 and membrane-bound ERα by bound estrogen mediates rapid cell signaling to activate a variety of second messengers and signal mediators [65, 66]. Furthermore, crosstalk has been implicated in the ER pathway with the membrane receptor pathways for epidermal growth factor (EGF), insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) and transforming growth factor α (TGFα) [77, 80], or in the GRP30 pathway with those for EGF and TGFα, both of which bind to the EGF receptor (EGFR), by direct interaction between GPR30 and EGFR [81], eventually leading to biological responses such as gene expression and cell proliferation. While ERs and GPR30 are involved in the same estrogen actions on the cardiovascular system, including reduced vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation, GPR30 agonist G-1 showed different responses in endothelial cell proliferation from estrogen [82, 83], suggesting the ligand-dependent response of cell proliferation.

IGF-I and BRCA1 play key roles in estrogen-induced cell signaling. BRCA1 negatively regulates the transcription of IGF-I as part of the transcription machinery, and loss of function of BRCA1 results in constitutive activation of the IGF-I receptor (IGF1R) pathway, possibly causing breast cancer phenotypes [84]. Estrogen transactivates BRCA1 and IGF1R promoters, and BRCA1, but not mutant BRCA1, inhibits the estrogen-induced activation of ERα transcription.

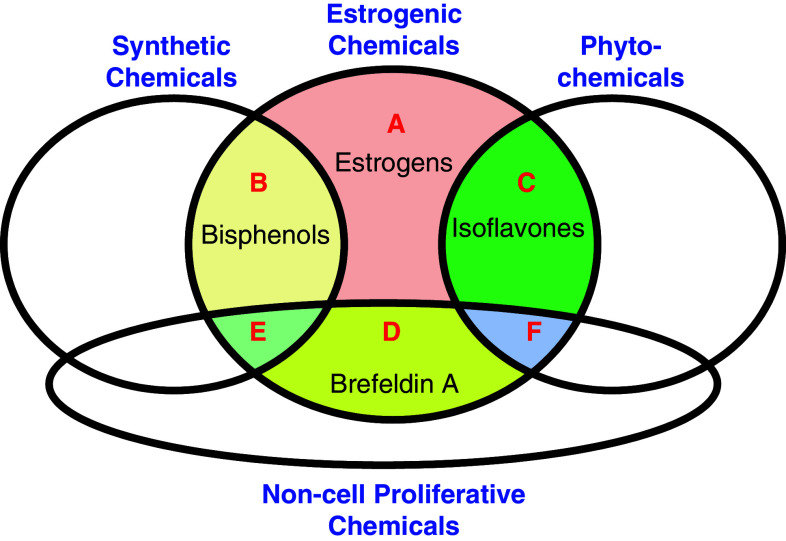

Silent estrogens: a new category of estrogenic chemicals

A series of extensive analyses of chemicals by means of DNA microarray assay of the estrogenic transcriptional response revealed that some chemicals show estrogenic gene expression profiles without showing positive effects on cell proliferation, and we termed them “silent estrogens” [54] (Fig. 3). The first of such chemicals was BFA, a lactone antibiotic originally found in a fungus, Eupenicillium brefeldianum, but currently well known for its inhibitory activity of intracellular protein transport from the endoplasmic reticulum to the Golgi apparatus. BFA showed a significant level of correlation (correlation coefficient R = 0.61) of the expression profile of estrogen-responsive genes in breast cancer MCF-7 cells with that of E2, while there was no positive effect on cell proliferation at any concentration [54]. Apart from the difference in the expression of some estrogen-responsive genes, TTF1, for example, there are significant differences between BFA and E2, in the effect of estrogen antagonist ICI 182,780, which suggests the involvement of discrete signaling pathways for BFA and may explain its absence of growth-stimulating activity. We found that BFA is not the only chemical that can be categorized as a silent estrogen (data not shown). Since the extract of A. blazei, from which estrogenic activity of BFA was found, showed an estrogenic gene expression profile together with growth-stimulating activity [45], similar approaches could be explored to separate these two activities and find silent estrogens from natural and artificial sources. Such activity was found in licorice extracts [59] and oil-degradation products [55], where cell proliferation-independent gene expression profiles were observed.

Fig. 3.

Groups of chemicals classified by estrogenicity and cell proliferation activity

The mechanism of silent estrogens has not been explored much. As mentioned above, there might be several ways of modulating estrogenic activity such as through (1) the alteration in activation functions of ERs, (2) the modulation of membrane receptor-mediated signaling pathways, (3) separate and independent pathways responsible for estrogenic expression profiles and the lack of cell proliferation or (4) as yet unidentified pathways, or (5) any combination of (1) to (4). Since BFA has quite a different structure from that of E2, although its molecular weight is similar, activation functions of ERs are modulated by altered interactions of BFA and the domains affecting AF2, such as that observed for SERMs [16]. Meanwhile, there is a possibility of alterations at the receptors. We observed a clear difference in the effect of ICI 182,780 between E2 and BFA. While BFA showed rapid activation of Erk1/2, Akt and P70S6 K, which was seen within 15–60 min after stimulation with E2 or BFA, the inhibitory effect of ICI 182,780 was observed only for E2 [54]. A similar effect was observed for another estrogenic chemical, bisphenol A, which mediates the rapid estrogenic signal through GPR30 [85], suggesting the involvement of membrane pathways. Note that bisphenol A has cell-proliferation activity, and therefore, it is not a silent estrogen.

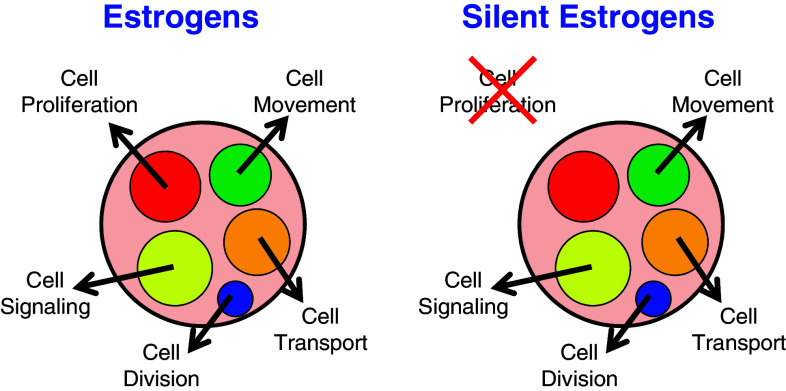

Cell proliferation induced by phytoestrogens

Phytoestrogens consist of four major groups of chemicals, isoflavones, stilbenes, coumestans and lignans [86], and attention has been increasing because of their benefits such as reducing cancer risk, preventing cancer growth, improving atherosclerotic symptoms and supplementing endogenous hormones [87–89]. However, their characteristics are diverse because there are so many types of chemicals with various degrees of estrogenic activity [90], along with various additional activities [87], and, more importantly, estrogenic activity itself is diverse. It is known that tamoxifen acts as an antagonist against breast cancer but an agonist to uterine cancer, and chemicals such as tamoxifen or SERMs are characterized by their selective inhibition or stimulation dependent upon tissues [17]. Phytoestrogens are considered as SERMs and their beneficial as well as harmful effects have been discussed [88, 89]. Furthermore, a number of phytoestrogens are characterized by their suppressive but not stimulative effects on cell proliferation, especially at higher concentrations, because they bind more to growth-suppressive ERβ than growth-stimulative ERα [86]. A class of chemicals specifically lacking some physiological effects can therefore be anticipated, such as cell proliferation discussed here. However, as cell proliferation is one of the major roles of estrogen, assays for phytoestrogens often include analysis of whether they have positive or negative effects on cell proliferation [91]. Expression profiles of estrogen-responsive genes have been used as a set of standardized markers representing overall estrogenic actions such as cell proliferation, cell movement, cell signaling, cell division and cell transport (Fig. 4), and cell proliferation alone was examined at the cellular level, but is not necessarily related with gene transcription. Therefore, it is not difficult to imagine that estrogenic gene expression profiles are maintained while signals specifically directing cell proliferation are abrogated.

Fig. 4.

Estrogenic responses of estrogens and silent estrogens. Estrogenic responses at the cellular level (outside the boundary) or the gene-expression level (inside the boundary) are illustrated

Silent estrogens for medical use

Information regarding medical potentiality is so far limited. While we observed an improvement of artificial atherosclerotic legions in rabbits fed a high-cholesterol diet after uptake of the extract of A. blazei containing BFA [45], such a clear improvement was not observed for BFA alone, probably because of its poor water solubility [54]. Such a problem occurs in many hydrophobic chemicals including estrogen, which is present as a bound form with carriers such as sex-hormone binding globulin (SHBP) due to its poor water solubility and its effective bioavailability [92]. Furthermore, an improvement of the level of oxidized low-density lipoprotein (LDL) in hyperlipidemic patients, the effect of reducing reactive oxygen species (ROS) and a positive effect on nitrogen-oxide (NO) production within the cell were observed for estrogen and the extract of A. blazei [45], while they have not been examined for BFA. However, activation of Erk1/2, Akt and P70R6 K was observed for both materials [54], suggesting that some cell functions could be attributable to BFA.

Silent estrogens are mostly what we expect from phytoestrogens. However, it is important to note that BFA has never been classified as an estrogenic chemical. Indeed, all the phytoestrogens that we examined for estrogenic gene-expression profiles, including isoflavones, flavones, flavanols, phloretin, coumestrol, naringenin [52], ginsenosides [60], and zearalenone and their derivatives [56], were reported to have growth-stimulating activity. Therefore, silent estrogens could be a new category of chemicals that have not been recognized for their estrogenic effects, and lacking growth-stimulating activity would be advantageous as controlling cell proliferation is critical for the prevention of cancer growth. In addition, BFA is known to have various effects, which are not necessarily estrogenic, such as its anti-viral and anti-tumor effects, and more importantly, binding to Sec7, a guanine-nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) of small GTPase Arf1, and inhibiting the Arf1-mediated formation of vesicles for protein transport by stabilizing an abortive complex between Arf1-GDP and the catalytic domain in Sec7 [93]. Since the concentrations exhibiting the inhibition of cell transport are at least 100 times higher than those used for gene-expression profiling and intracellular signaling, estrogenic effects, if any, would not be damaged.

Prospect of DNA microarray-based gene expression profiling

Industrial applications

Applications of DNA microarray-based gene expression profiling have been explored in several industrial fields, including pharmaceuticals and foods, diagnostic and prognostic tests, and environmental technology. First, gene expression profiling by means of microarrays was used to develop drugs for the treatment of inflammation [94], heart failure [95] and cancer [96]. Microarray technology would be beneficial in this field to reduce sample size and trial time, and to increase the number of marker genes used to predict their efficacy as well as toxicity. For example, expression profiling has been used to distinguish genotoxic from non-genotoxic effects and to provide information on the mechanism of action [97]. Second, the technology was used in the development of functional foods [98] and food safety assessment [99, 100]. Microarrays have been listed as one of the key strategies to detect alterations in the gene expression of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) for safety evaluation [101]. Third, an important field in its application is the technology of medical devices, such as diagnostic and prognostic tests. However, quite a number of researchers noted that many published reports need further lines of extensive statistical evaluation based on appropriate sets of parameters and algorithms [62, 102]. Fourth, another important field is toxicological studies (toxicogenomics) [103, 104] and environmental risk assessment [105, 106]. From a survey of toxicogenomic studies, Fent and Sumpter [107] summarized that microarray data can give a set of unbiased, comprehensive and sometimes novel information about the gene expression of toxicants or their mode of action, although there are some technical difficulties and problems of cost performance, quality of data, standardization of protocols and consistency with physiological data.

Microarray technology needs significant care of the samples taken during surgery (treatment of tissues and short-term storage), handling (transport and long-term storage), preparation (extraction, purification and storage) and quality evaluation step (pre-analysis step) even before the microarray assay or the analytical step. Since sample preparation affects the quality of gene expression data, significant attention has been paid to the usage of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples [108]. However, although collection and storage of FFPE samples are routinely practiced in pathology laboratories, the quality of RNA is often questionable, and it may not be suitable for microarray assay without appropriate quality control protocols with standard values. As was often argued about the reliability of microarray data, variations derived from biological, experimental and technical differences should be examined [109]. Performance such as false positive rates and predictability, and the strength for commercialization such as cost and automation, were examined for immunohistochemistry, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and microarray technology, and two commercial products, RT-PCR-based Oncotype DX and microarray-based MammaPrint, were cross-examined [110]. While there are various advantages as well as disadvantages of microarray technology, an important point distinguishing these technologies is the number of markers used; 21 genes in Oncotype DX and 70 genes in MammaPrint, for example. Generally, the number of markers is one to a few in immunohistochemistry and FISH, a few to tens in RT-PCR, and tens to hundreds or more in microarray technology [4, 110, 111]. Thus, none of these technologies are superior, but they may co-exist depending on the necessity and the situation.

Pathway-based technological applications

DNA microarray-based gene expression profiling has been used for pathway analysis because the recent progress in the study of specific signaling pathways needs comprehensive analysis of complex higher orders of networks consisting of various major or minor pathways, which were revealed by the analysis of ligand/receptor interaction, receptor crosstalk, bypassing cascades, inhibitor/stimulator activity and agonistic/antagonistic effects, and thus, we can see quite a number of higher orders of networks identified by microarray assays. For example, microarrays have been used for various signaling pathways/cascades, such as MAPK, angiogenesis, nuclear receptor, ErbB/HER, ubiquitin/proteasome signalings, various cellular functions, such as chromatin/epigenetic regulation, apoptosis, autophagy, cellular metabolism, translational control, cell cycle/DNA damage, and cytoskeletal regulation and adhesion, and various higher levels of functions, such as immunology and inflammation, neuroscience, and development and differentiation (detailed in Table 3).

Table 3.

Microarrays and signaling pathways

| Pathway/cascade/function | Key molecule(s) identifieda | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| MAPK signaling | ||

| GPCR/MAPK | Small GTPase/apoptosis signaling genes | MAPK Chang et al. [137] |

| NFκB/MAPK/ERK | PI3 K/Akt/mTOR | Mendes et al. [138] |

| MAPK/JNK | Mitochondrial function related genes | Cízková et al. [139] |

| Other signaling | ||

| Angiogenesis signaling | HIF-1α-dependent genes | Copple et al. [140] |

| Nuclear receptor signaling | PPARγ-associated genes | Lee et al. [141] |

| ErbB/HER signaling | Scaffolding adaptors | Nakaoka et al. 2007 [142] |

| Ubiquitin/proteasome signaling | NF-κB/IκB signaling genes | Granese et al. [143] |

| Chromatin/epigenetic regulation | ||

| Histone modification | Hdac1 (histone deacetylase) | Reichmann et al. [144] |

| Heterochromatin | HP1-regulated genes | Lee et al. [145] |

| DNA methylation | SCARA5 (scavenger receptor) | Khamas et al. [146] |

| Apoptosis | ||

| Infectious response | NF-κB/p53/RB/JUN/apoptosis genes | Faherty et al. [147] |

| Virus induced apoptosis | p53/caspase-1 | Nasirudeen and Liu [148] |

| Death receptor signaling | FAS-mediated apoptosis genes | Wang et al. [149] |

| Autophagy | ||

| Starvation stress | Autophagy-related genes | Burgess et al. [150] |

| PI3 K/Akt/FOXO/mTOR | Glutamine synthetase | van der Vos et al. [151] |

| Cellular metabolism | ||

| Insulin receptor signaling | Metabolic process-related genes | Bolukbasi et al. [152] |

| AMPK signaling | AMPK activators | Solskov et al. [153] |

| Translational control | ||

| eIF2 signaling | tRNA processing genes | Saikia et al. [154] |

| eIF4/p70S6 K signaling | eIF4 factors | Villas-Bôas et al. [155] |

| mTOR signaling | TGF-β/MNK1/SMAD2 | Grzmil et al. [156] |

| Cell cycle/DNA damage | ||

| G1/S checkpoint | EIF2 activator | Stockwell et al. [157] |

| G2/M DNA damage checkpoint | RB/E2F/ECT2 | Eguchi et al. [158] |

| Cytoskeletal regulation and adhesion | ||

| Actin dynamics | PKCδ/cofilin | Wada-Kiyama et al. [159] |

| Microtubule dynamics | Formin1 | Simon-Areces et al. [160] |

| Adherens junction dynamics | Diabetes-related genes | Caramori et al. [161] |

| Immunology and inflammation | ||

| Inflammatory response | miR-155/Jak/STAT | Kutty et al. [162] |

| Cytokine receptor signaling | TLR/IL-1R | Abend et al. [163] |

| T-cell activation | NF-κB/Rel | Chang et al. [164] |

| TLR-sinduced inflammation | TLR4-responsive genes | Yang et al. [165] |

| B-cell receptor signaling | Cytokines | Franke et al. [166] |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | T-cell receptors | Kim et al. [167] |

| Neuroscience | ||

| Alzheimer’s disease | Neurological disease-related genes | Walker et al. [168] |

| Parkinson’s disease | FOXO1 | Dumitriu et al. [169] |

| Development and differentiation | ||

| Wnt/β-catenin signaling | Wnt-associated genes | Nguyen et al. [170] |

| Notch signaling | RB family genes | Viatour et al. [171] |

| Hedgehog signaling | Eyeless/hedgehog-regulated genes | Nfonsam et al. [172] |

| TGF-β signaling | Corneal dystrophy-associated genes | Choi et al. [173] |

Classification of pathways/cascades/functions was based on that by Cell Signaling Technology (http://www.cellsignal.com/). A representative case is listed for each category

AMPK AMP-activated protein kinase, eIF eukaryotic initiation factor, FOXO forkhead box O, GPCR G-protein-coupled receptor, IGF-1 insulin-like growth factor-1, IL-1R interleukin-1 receptor, JNK c-Jun N-terminal kinase, MAPK mitogen-activated protein kinase, mTOR mammalian target of rapamycin, PI3 K phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, PPARγ peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ, RB retinoblastoma, TLR Toll-like receptor

aProteins and/or cellular factors identified by microarray assay and subsequent characterization, such as RT-PCR and Western blotting

On the other hand, specific signatures consisting of the genes representing pathways of signal mediators, hormones/growth factors and oncogenes/tumor suppressors are useful for some applications, such as breast cancer diagnosis [112]. However, this approach needs more pathway-based analysis of gene expression profiles to find the best signatures for the purpose and only a few have been commercialized so far. It should be noted that transcriptomics is not the sole technology used to understand the pathways related to applications, and other ‘omics’ technologies, such as proteomics and metabolomics, will be used in the future separately or in combination with the transcriptomic data. Likewise, utilization of epigenetic changes such as those observed by DNA methylation, histone modifications and non-coding RNAs has also become a reality [113].

Innovation, specification, generalization and standardization

Innovation is not always followed by immediate commercialization or success in the market. The difficulty between the technological development and successful commercialization is called the valley of death [114]. Such difficulty was successfully overcome by microarray technology in the late 1990s partly but significantly because of increased demands from various genome projects for high-throughput technologies for screening genes with specific functions and for analyzing newly identified expressed sequence tags (ESTs), or pieces of cDNA of unknown origin, to find their potential functions [115]. For such purposes, global microarrays were useful, and several companies, Affymetrix, Agilent Technologies and Illumina, for example, manufactured this type of microarray. However, the efforts of a number of researchers have been focused on finding specific sets of genes, or signatures, which can be used in respective applications. Specific signatures will gain more importance because of the trend toward personalized medicine, and information at the molecular level, such as that provided by various ‘omics’ technologies, will form a new healthcare paradigm. Such specification is an important step for technologies to cross the valley of death and to enter the next stage, generalization, which can be achieved by governmental approval of diagnostic devices or risk-assessing tools, for example, and public familiarity as a useful tool as well as stability and competitiveness in the market. Immunoassays such as ELISA and its variations have gone through this process [116].

An important step for a technology to gain stability in public or industrial acknowledgement is its standardization. Standardization is the process of developing and implementing technical standards to achieve commoditization (independence of single suppliers), compatibility, interoperability, safety, repeatability and/or quality. Standardization of DNA microarrays was started by the MicroArray Quality Control (MAQC) Consortium, a consortium of 51 academic, government and commercial institutions organized by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2006 [117] after criticism of the reliability of microarray data [62] and, through two periods of activity (MAQC-I and II), MAQC provided the international microarray community with quality control tools, guidelines for protocols, thresholds/limitations in assessing the performance and models for best practices in pharmacogenomics and toxicogenomics. The MAQC Consortium reported a framework for assessing microarray technologies as a reliable tool for clinical and regulatory purposes, such as a median coefficient of variation (CV) of 5–15 % and a concordance rate of 80–95 % among the platforms tested (MAQC-I [118]), and examples of genomic classifiers, gene signatures representing specific pathological conditions, by examining data preprocessing and normalization methods, and algorithms and protocols for discerning patterns and identifying signatures using clinical and toxicological data (MAQC-II [119]).

MAQC activity was immediately followed by other countries, including European countries and Japan, to further standardize the analytical and pre-analytical steps for the quality control of clinical samples in gene-based diagnostic tests. SPIDIA (Standardisation and improvement of generic pre-analytical tools and procedures for in vitro diagnostics) is a 4.5-year project, funded by the European Union, to standardize and improve pre-analytical procedures for in vitro diagnostics. SPIDIA’s activities are intended to create evidence-based guidelines and tools, and protocols for pre-analytical tests, and to develop biomarkers for quality control [120]. In a recent report, the pre-analytical phase of blood samples from 102 European laboratories was assessed by the stability and quality of RNA after extraction with different tubes under different conditions [121]. On the other hand, the Japanese government also provided companies, academic institutions and public agencies with guidelines and guidance for industrial development (http://www.meti.go.jp/policy/mono_info_service/service/iryou_fukushi/) and governmental drug-approval (http://www.pmda.go.jp/operations/shonin/info/iryokiki/iryokiki-list.html) purposes. Meanwhile, global standardization of DNA microarrays and other gene expression-based in vitro diagnostic devices has been pursued by Technical Committee 212 of the International Organization for Standardization (ISO/TC 212), which focuses on clinical laboratory testing and in vitro diagnostic test systems, and includes quality management, pre- and post-analytical procedures, analytical performance, laboratory safety, reference systems and quality assurance, or by the newly organized ISO/TC 276, which focuses on analytical methods based on ‘omics’ technologies.

During the standardization process, however, severe competition among industries occurs, and commercialization could stop because their products are not included in the tools or protocols subjected to standardization, not because their quality, performance, cost or even patent strength are inferior to others. In this sense, the roles of governments and regional consortia, such as those of MAQC and SPIDIA, will become greater than ever.

Acknowledgments

This research has been supported partly by a Special Coordination Fund for Promoting Science and Technology (Encouraging Development of Strategic Research Centers), a Knowledge Cluster Initiative program and a Grant-in-aid for Basic Areas from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan, and by the Guideline Program for Medical Device Development from the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry of Japan.

References

- 1.Schena M, Shalon D, Davis RW, Brown PO. Quantitative monitoring of gene expression patterns with a complementary DNA microarray. Science. 1995;270(5235):467–470. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5235.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Churchill GA. Fundamentals of experimental design for cDNA microarrays. Nat Genet. 2002;32(Suppl):490–495. doi: 10.1038/ng1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leung YF, Cavalieri D. Fundamentals of cDNA microarray data analysis. Trends Genet. 2003;19(11):649–659. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2003.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reis-Filho JS, Pusztai L. Gene expression profiling in breast cancer: classification, prognostication, and prediction. Lancet. 2011;378(9805):1812–1823. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61539-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Inoue A, Tanji M, Kiyama R. Focused microarray analysis: characterization of phenomes by gene expression profiling. Curr Pharmacogenomics. 2006;4:245–260. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glas AM, Floore A, Delahaye LJ, Witteveen AT, Pover RC, Bakx N, Lahti-Domenici JS, Bruinsma TJ, Warmoes MO, Bernards R, Wessels LF, Van’t Veer LJ. Converting a breast cancer microarray signature into a high-throughput diagnostic test. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:278. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Monzon FA, Dumur CI. Diagnosis of uncertain primary tumors with the Pathwork tissue-of-origin test. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2010;10(1):17–25. doi: 10.1586/erm.09.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.European Community. (2006) Regulation (EC) No. 1907/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 December 2006 concerning the Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH). EC Regulation, retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/environment/chemicals/reach/reach_intro.htm

- 9.National Research Council . Toxicity Testing in the 21st Century: A vision and a strategy. Washington: National Academies Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mueller SO. Xenoestrogens: mechanisms of action and detection methods. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2004;378(3):582–587. doi: 10.1007/s00216-003-2238-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tanji M, Kiyama R. Expression profiling of estrogen responsive genes using genomic and proteomic techniques for the evaluation of endocrine disruptors. Curr Pharmacogenomics. 2004;2:255–266. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moggs JG. Molecular responses to xenoestrogens: mechanistic insights from toxicogenomics. Toxicology. 2005;213(3):177–193. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2005.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagai MA, Brentani MM. Gene expression profiles in breast cancer to identify estrogen receptor target genes. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2008;8(5):448–454. doi: 10.2174/138955708784223503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hah N, Kraus WL. Hormone-regulated transcriptomes: lessons learned from estrogen signaling pathways in breast cancer cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2014;382(1):652–664. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2013.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roy NC, Altermann E, Park ZA, McNabb WC. A comparison of analog and Next-Generation transcriptomic tools for mammalian studies. Brief Funct Genomics. 2011;10(3):135–150. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/elr005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heldring N, Pike A, Andersson S, Matthews J, Cheng G, Hartman J, Tujague M, Ström A, Treuter E, Warner M, Gustafsson JA. Estrogen receptors: how do they signal and what are their targets. Physiol Rev. 2007;87(3):905–931. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00026.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ibrahim NK, Hortobagyi GN. The evolving role of specific estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) Surg Oncol. 1999;8(2):103–123. doi: 10.1016/s0960-7404(99)00047-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herrero M, Ibáñiez E, Cifuentes A. Analysis of natural antioxidants by capillary electromigration methods. J Sep Sci. 2005;28(9–10):883–897. doi: 10.1002/jssc.200400104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meulenberg EP. Phenolics: occurrence and immunochemical detection in environment and food. Molecules. 2009;14(1):439–473. doi: 10.3390/molecules14010439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gajecki M. Zearalenone—undesirable substances in feed. Pol J Vet Sci. 2002;5(2):117–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bennett JW, Klich M. Mycotoxins. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003;16(3):497–516. doi: 10.1128/CMR.16.3.497-516.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cornwell T, Cohick W, Raskin I. Dietary phytoestrogens and health. Phytochemistry. 2004;65(8):995–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chakraborty S, Chakraborty TR. Estrogen-like endocrine disrupting chemicals affecting puberty in humans–a review. Med Sci Monit. 2009;15(6):RA137–RA145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frye CA, Bo E, Calamandrei G, Calzà L, Dessì-Fulgheri F, Fernández M, Fusani L, Kah O, Kajta M, Le Page Y, Patisaul HB, Venerosi A, Wojtowicz AK, Panzica GC. Endocrine disrupters: a review of some sources, effects, and mechanisms of actions on behaviour and neuroendocrine systems. J Neuroendocrinol. 2012;24(1):144–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2011.02229.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jefferson WN, Padilla-Banks E, Clark G, Newbold RR. Assessing estrogenic activity of phytochemicals using transcriptional activation and immature mouse uterotrophic responses. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2002;777(1–2):179–189. doi: 10.1016/s1570-0232(02)00493-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Serafim TL, Carvalho FS, Marques MP, Calheiros R, Silva T, Garrido J, Milhazes N, Borges F, Roleira F, Silva ET, Holy J, Oliveira PJ. Lipophilic caffeic and ferulic acid derivatives presenting cytotoxicity against human breast cancer cells. Chem Res Toxicol. 2011;24(5):763–774. doi: 10.1021/tx200126r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ng TB, Ye XJ, Wong JH, Fang EF, Chan YS, Pan W, Ye XY, Sze SC, Zhang KY, Liu F, Wang HX. Glyceollin, a soybean phytoalexin with medicinal properties. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;90(1):59–68. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3169-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson JJ, Syed DN, Suh Y, Heren CR, Saleem M, Siddiqui IA, Mukhtar H. Disruption of androgen and estrogen receptor activity in prostate cancer by a novel dietary diterpene carnosol: implications for chemoprevention. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2010;3(9):1112–1123. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kjeldsen LS, Bonefeld-Jørgensen EC. Perfluorinated compounds affect the function of sex hormone receptors. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2013;20(11):8031–8044. doi: 10.1007/s11356-013-1753-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Byrne C, Divekar SD, Storchan GB, Parodi DA, Martin MB. Metals and breast cancer. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2013;18(1):63–73. doi: 10.1007/s10911-013-9273-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Orrego R, Guchardi J, Krause R, Holdway D. Estrogenic and anti-estrogenic effects of wood extractives present in pulp and paper mill effluents on rainbow trout. Aquat Toxicol. 2010;99(2):160–167. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2010.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang X, Mukerji R, Samadi AK, Cohen MS. Down-regulation of estrogen receptor-alpha and rearranged during transfection tyrosine kinase is associated with withaferin a-induced apoptosis in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2011;11:84. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-11-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shi C, Na N, Zhu X, Xu J. Estrogenic effect of ginsenoside Rg1 on APP processing in post-menopausal platelets. Platelets. 2013;24(1):51–62. doi: 10.3109/09537104.2012.654839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen D, Carter TH, Auborn KJ. Apoptosis in cervical cancer cells: implications for adjunct anti-estrogen therapy for cervical cancer. Anticancer Res. 2004;24(5A):2649–2656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martínez-Campa CM, Alonso-González C, Mediavilla MD, Cos S, González A, Sanchez-Barcelo EJ. Melatonin down-regulates hTERT expression induced by either natural estrogens (17beta-estradiol) or metalloestrogens (cadmium) in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2008;268(2):272–277. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen CC, Shieh B, Jin YT, Liau YE, Huang CH, Liou JT, Wu LW, Huang W, Young KC, Lai MD, Liu HS, Li C. Microarray profiling of gene expression patterns in bladder tumor cells treated with genistein. J Biomed Sci. 2001;8(2):214–222. doi: 10.1007/BF02256415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Watanabe H, Suzuki A, Mizutani T, Khono S, Lubahn DB, Handa H, Iguchi T. Genome-wide analysis of changes in early gene expression induced by oestrogen. Genes Cells. 2002;7(5):497–507. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2002.00535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Naciff JM, Jump ML, Torontali SM, Carr GJ, Tiesman JP, Overmann GJ, Daston GP. Gene expression profile induced by 17alpha-ethynyl estradiol, bisphenol A, and genistein in the developing female reproductive system of the rat. Toxicol Sci. 2002;68(1):184–199. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/68.1.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Levenson AS, Kliakhandler IL, Svoboda KM, Pease KM, Kaiser SA, Ward JE, 3rd, Jordan VC. Molecular classification of selective oestrogen receptor modulators on the basis of gene expression profiles of breast cancer cells expressing oestrogen receptor alpha. Br J Cancer. 2002;87(4):449–456. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adachi T, Komiyama M, Ono Y, Koh KB, Sakurai K, Shibayama T, Kato M, Yoshikawa T, Seki N, Iguchi T, Mori C. Toxicogenomic effects of neonatal exposure to diethylstilbestrol on mouse testicular gene expression in the long term: a study using cDNA microarray analysis. Mol Reprod Dev. 2002;63(1):17–23. doi: 10.1002/mrd.10178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tabuchi Y, Zhao QL, Kondo T. DNA microarray analysis of differentially expressed genes responsive to bisphenol A, an alkylphenol derivative, in an in vitro mouse Sertoli cell model. Jpn J Pharmacol. 2002;89(4):413–416. doi: 10.1254/jjp.89.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Inoue A, Yoshida N, Omoto Y, Oguchi S, Yamori T, Kiyama R, Hayashi S. Development of cDNA microarray for expression profiling of estrogen-responsive genes. J Mol Endocrinol. 2002;29(2):175–192. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0290175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li Y, Sarkar FH. Gene expression profiles of genistein-treated PC3 prostate cancer cells. J Nutr. 2002;132(12):3623–3631. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.12.3623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Terasaka S, Aita Y, Inoue A, Hayashi S, Nishigaki M, Aoyagi K, Sasaki H, Wada-Kiyama Y, Sakuma Y, Akaba S, Tanaka J, Sone H, Yonemoto J, Tanji M, Kiyama R. Using a customized DNA microarray for expression profiling of the estrogen-responsive genes to evaluate estrogen activity among natural estrogens and industrial chemicals. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112(7):773–781. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dong S, Furutani Y, Suto Y, Furutani M, Zhu Y, Yoneyama M, Kato T, Itabe H, Nishikawa T, Tomimatsu H, Tanaka T, Kasanuki H, Masaki T, Kiyama R, Matsuoka R. Estrogen-like activity and dual roles in cell signaling of an Agaricus blazei Murrill mycelia-dikaryon extract. Microbiol Res. 2012;167(4):231–237. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhu Y, Ogaeri T, Suzuki J, Dong S, Aoyagi T, Mizuki K, Takasugi M, Isobe S, Kiyama R. Application of Fluolid-Orange-labeled probes for DNA microarray and immunological assays. Biotechnol Lett. 2011;33(9):1759–1766. doi: 10.1007/s10529-011-0646-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brown AM, Jeltsch JM, Roberts M, Chambon P. Activation of pS2 gene transcription is a primary response to estrogen in the human breast cancer cell line MCF-7. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81(20):6344–6348. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.20.6344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ghosh MG, Thompson DA, Weigel RJ. PDZK1 and GREB1 are estrogen-regulated genes expressed in hormone-responsive breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2000;60(22):6367–6375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Qin C, Singh P, Safe S. Transcriptional activation of insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-4 by 17beta-estradiol in MCF-7 cells: role of estrogen receptor-Sp1 complexes. Endocrinology. 1999;140(6):2501–2508. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.6.6751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Inoue A, Omoto Y, Yamaguchi Y, Kiyama R, Hayashi SI. Transcription factor EGR3 is involved in the estrogen-signaling pathway in breast cancer cells. J Mol Endocrinol. 2004;32(3):649–661. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0320649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rho JY, Wada-Kiyama Y, Onishi Y, Kiyama R, Sakuma Y. Expressional regulation of neuronal and cancer-related genes by estrogen in adult female rats. Endocr Res. 2004;30(2):257–267. doi: 10.1081/erc-120039579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ise R, Han D, Takahashi Y, Terasaka S, Inoue A, Tanji M, Kiyama R. Expression profiling of the estrogen responsive genes in response to phytoestrogens using a customized DNA microarray. FEBS Lett. 2005;579(7):1732–1740. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Terasaka S, Inoue A, Tanji M, Kiyama R. Expression profiling of estrogen-responsive genes in breast cancer cells treated with alkylphenols, chlorinated phenols, parabens, or bis- and benzoylphenols for evaluation of estrogenic activity. Toxicol Lett. 2006;163(2):130–141. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dong S, Furutani Y, Kimura S, Zhu Y, Kawabata K, Furutani M, Nishikawa T, Tanaka T, Masaki T, Matsuoka R, Kiyama R. Brefeldin A is an estrogenic, Erk1/2-activating component in the extract of Agaricus blazei mycelia. J Agric Food Chem. 2013;61(1):128–136. doi: 10.1021/jf304546a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhu Y, Kitamura K, Maruyama A, Higashihara T, Kiyama R. Estrogenic activity of bio-degradation products of C-heavy oil revealed by gene-expression profiling using an oligo-DNA microarray system. Environ Pollut. 2012;168:10–14. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Parveen M, Zhu Y, Kiyama R. Expression profiling of the genes responding to zearalenone and its analogues using estrogen-responsive genes. FEBS Lett. 2009;583(14):2377–2384. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Inoue A, Seino Y, Terasaka S, Hayashi S, Yamori T, Tanji M, Kiyama R. Comparative profiling of the gene expression for estrogen responsiveness in cultured human cell lines. Toxicol In Vitro. 2007;21(4):741–752. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2007.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Parveen M, Inoue A, Ise R, Tanji M, Kiyama R. Evaluation of estrogenic activity of phthalate esters by gene expression profiling using a focused microarray (EstrArray) Environ Toxicol Chem. 2008;27(6):1416–1425. doi: 10.1897/07-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dong S, Inoue A, Zhu Y, Tanji M, Kiyama R. Activation of rapid signaling pathways and the subsequent transcriptional regulation for the proliferation of breast cancer MCF-7 cells by the treatment with an extract of Glycyrrhiza glabra root. Food Chem Toxicol. 2007;45(12):2470–2478. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2007.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dong S, Kiyama R. Characterisation of oestrogenic activity of ginsenosides in MCF-7 cells using a customised DNA microarray. Food Chem. 2009;113(2):672–678. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Klebanov L, Qiu X, Welle S, Yakovlev A. Statistical methods and microarray data. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25(1):25–26. doi: 10.1038/nbt0107-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Michiels S, Koscielny S, Hill C. Prediction of cancer outcome with microarrays: a multiple random validation strategy. Lancet. 2005;365(9458):488–492. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17866-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ioannidis JP. Microarrays and molecular research: noise discovery? Lancet. 2005;365(9458):454–455. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17878-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Walter P. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 5. New York: Garland Science; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Filardo EJ, Thomas P. GPR30: a seven-transmembrane-spanning estrogen receptor that triggers EGF release. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2005;16(8):362–367. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fu XD, Simoncini T. Extra-nuclear signaling of estrogen receptors. IUBMB Life. 2008;60(8):502–510. doi: 10.1002/iub.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nilsson S, Mäkelä S, Treuter E, Tujague M, Thomsen J, Andersson G, Enmark E, Pettersson K, Warner M, Gustafsson JA. Mechanisms of estrogen action. Physiol Rev. 2001;81(4):1535–1565. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.4.1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Green S, Chambon P. Nuclear receptors enhance our understanding of transcription regulation. Trends Genet. 1988;4(11):309–314. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(88)90108-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Abot A, Fontaine C, Raymond-Letron I, Flouriot G, Adlanmerini M, Buscato M, Otto C, Bergès H, Laurell H, Gourdy P, Lenfant F, Arnal JF. The AF-1 activation function of estrogen receptor α is necessary and sufficient for uterine epithelial cell proliferation in vivo. Endocrinology. 2013;154(6):2222–2233. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Billon-Galés A, Krust A, Fontaine C, Abot A, Flouriot G, Toutain C, Berges H, Gadeau AP, Lenfant F, Gourdy P, Chambon P, Arnal JF. Activation function 2 (AF2) of estrogen receptor-alpha is required for the atheroprotective action of estradiol but not to accelerate endothelial healing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(32):13311–13316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105632108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Feng W, Webb P, Nguyen P, Liu X, Li J, Karin M, Kushner PJ. Potentiation of estrogen receptor activation function 1 (AF-1) by Src/JNK through a serine 118-independent pathway. Mol Endocrinol. 2001;15(1):32–45. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.1.0590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cheskis BJ, Greger J, Cooch N, McNally C, Mclarney S, Lam HS, Rutledge S, Mekonnen B, Hauze D, Nagpal S, Freedman LP. MNAR plays an important role in ERa activation of Src/MAPK and PI3 K/Akt signaling pathways. Steroids. 2008;73(9–10):901–905. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2007.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Makker A, Goel MM, Das V, Agarwal A. PI3 K-Akt-mTOR and MAPK signaling pathways in polycystic ovarian syndrome, uterine leiomyomas and endometriosis: an update. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2012;28(3):175–181. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2011.583955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Eisinger-Mathason TS, Andrade J, Lannigan DA. RSK in tumorigenesis: connections to steroid signaling. Steroids. 2010;75(3):191–202. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2009.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wertheimer E, Gutierrez-Uzquiza A, Rosemblit C, Lopez-Haber C, Sosa MS, Kazanietz MG. Rac signaling in breast cancer: a tale of GEFs and GAPs. Cell Signal. 2012;24(2):353–362. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sonderegger S, Pollheimer J, Knöfler M. Wnt signalling in implantation, decidualisation and placental differentiation—review. Placenta. 2010;31(10):839–847. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Butt AJ, McNeil CM, Musgrove EA, Sutherland RL. Downstream targets of growth factor and oestrogen signalling and endocrine resistance: the potential roles of c-Myc, cyclin D1 and cyclin E. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2005;12(Suppl 1):S47–S59. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.00993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Levin ER. Integration of the extranuclear and nuclear actions of estrogen. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19(8):1951–1959. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kushner PJ, Agard DA, Greene GL, Scanlan TS, Shiau AK, Uht RM, Webb P. Estrogen receptor pathways to AP-1. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2000;74(5):311–317. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(00)00108-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Strobl JS, Wonderlin WF, Flynn DC. Mitogenic signal transduction in human breast cancer cells. Gen Pharmacol. 1995;26(8):1643–1649. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(95)00062-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Vivacqua A, Lappano R, De Marco P, Sisci D, Aquila S, De Amicis F, Fuqua SA, Andò S, Maggiolini M. G protein-coupled receptor 30 expression is up-regulated by EGF and TGF alpha in estrogen receptor alpha-positive cancer cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2009;23(11):1815–1826. doi: 10.1210/me.2009-0120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Holm A, Baldetorp B, Olde B, Leeb-Lundberg LM, Nilsson BO. The GPER1 agonist G-1 attenuates endothelial cell proliferation by inhibiting DNA synthesis and accumulating cells in the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle. J Vasc Res. 2011;48(4):327–335. doi: 10.1159/000322578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nilsson BO, Olde B, Leeb-Lundberg LM. G protein-coupled oestrogen receptor 1 (GPER1)/GPR30: a new player in cardiovascular and metabolic oestrogenic signalling. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;163(6):1131–1139. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01235.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Werner H, Bruchim I. IGF-1 and BRCA1 signalling pathways in familial cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(12):e537–e544. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70362-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Dong S, Terasaka S, Kiyama R. Bisphenol A induces a rapid activation of Erk1/2 through GPR30 in human breast cancer cells. Environ Pollut. 2011;159(1):212–218. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mense SM, Hei TK, Ganju RK, Bhat HK. Phytoestrogens and breast cancer prevention: possible mechanisms of action. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116(4):426–433. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Adlercreutz H. Phytoestrogens: epidemiology and a possible role in cancer protection. Environ Health Perspect. 1995;103(Suppl 7):103–112. doi: 10.1289/ehp.95103s7103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]