Abstract

The high toxicity of the seven serotypes of botulinum neurotoxins (BoNT/A to G), together with their specificity and reversibility, includes them in the list A of potential bioterrorism weapons and, at the same time, among the therapeutics of choice for a variety of human syndromes. They invade nerve terminals and cleave specifically the three proteins which form the heterotrimeric SNAP REceptors (SNARE) complex that mediates neurotransmitter release. The BoNT-induced cleavage of the SNARE proteins explains by itself the paralysing activity of the BoNTs because the truncated proteins cannot form the SNARE complex. However, in the case of BoNT/A, the most widely used toxin in therapy, additional factors come into play as it only removes a few residues from the synaptosomal associate protein of 25 kDa C-terminus and this results in a long duration of action. To explain these facts and other experimental data, we present here a model for the assembly of the neuroexocytosis apparatus in which Synaptotagmin and Complexin first assist the zippering of the SNARE complex, and then stabilize and clamp an octameric radial assembly of the SNARE complexes.

Keywords: Membrane fusion, SNARE complex, Clostridial neurotoxins, BoNT, Neuroexocytosis

Introduction

Several bacterial species of the genus Clostridium carry genes that encode for 1 or more of the 36 presently known botulinum neurotoxins isoforms; they are grouped into seven different serotypes (abbreviated BoNT/A to/G followed by an arabic number to distinguish isoforms) [1]. All the symptoms of botulism (diplopia, ptosis, difficult swallowing, autonomic dysfunctions, skeletal muscle paralysis, etc.) derive from the BoNT-induced blockade of release of acetyl choline from peripheral cholinergic nerve terminals [2]. Central effects of the BoNTs following their retroaxonal transport are emerging but they are masked by the predominant peripheral effects [3]; in any case, the pathological consequences of BoNTs intoxication are due to their almost incredible capability for entering inside nerve terminals, where they cleave specifically vesicle-associated membrane protein or synaptobrevin (VAMP), synaptosomal associate protein of 25 kDa (SNAP25) or Syntaxin [4]. VAMP is an integral membrane protein of the neurotransmitter-containing synaptic vesicles (SV), also termed Synaptobrevin, which is present in about 70 copies per SV [5]. SNAP25 and Syntaxin are present on the cytosolic face of the presynaptic membrane [6, 7]. The absolute neurospecificity and catalytic activity of the BoNTs makes them the most potent known poisons. From their toxicity [8], one can estimate that their concentrations in circulating fluids is in the femtomolar range. This is on the basis of the fact that they are included in the A list of substances of potential use in bioterrorism [9]. However, thanks to the pioneering work of Alan Scott supported by that of Alan Schantz [10], BoNT/A has become the therapeutics of choice for the treatment of human syndromes characterized by hyper function of peripheral cholinergic (autonomic or skeletal) nerve terminals. When used by medically trained personnel, BoNT/A is highly safe and its use has been extended to include treatment of pain and cosmetics [11–14].

All BoNTs consist of two polypeptide chains (L, light 50 kDa, and H, heavy 100 kDa) linked by an interchain disulphide bond. The available crystallographic structures of BoNT/A (PDB id: 3BTA), BoNT/B (PDB id: 1EPW) and /E (PDB id: 3FFZ; Fig. 1) [15–17] and the substantial sequence similarity [15] indicates that all BoNTs fold into four domains. Beginning from the N-terminus, these domains are termed: L chain or metalloprotease domain, HN membrane translocation domain (50 kDa), HC–N (25 kDa), and HC–C (25 kDa) which contains two binding sites for the two nerve terminal receptors: a polysialoganglioside and a protein receptor localized on the SV lumen [18].

Fig. 1.

Cartoon representation and domain composition of Botulinum Neurotoxins. Comparison between the crystallographic structures of BoNT/A (a) and BoNT/E (b). The L chain, translocation HN, binding HC–N, and HC–C domains are colored in blue, green, yellow, and red, respectively. The Zn2+ atom bound to the active site of the matalloprotease domain is shown in violet. Notice the different orientation of the HC domains of BoNT/E with respect to that of BoNT/A; the global architecture of BoNT/B (not shown) is nearly identical to that of BoNT/A

Such a structure is functionally correlated to the four steps of the mode of BoNTs intoxication of nerve terminals which are: (1) binding to nerve terminals mediated by HC–C, (2) internalization into small synaptic vesicles, (3) translocation of the L chain across the synaptic vesicle membrane mediated by HN, and (4) cleavage of SNAP REceptors (SNARE) proteins mediated by the L chain [19–21].

Both the structure and the first three steps of intoxication have recently been discussed in detail [18, 21–23]. Therefore, the present review will concentrate on the proteolytic activity of the BoNTs and on its consequences on the nanomachine, which mediate the release of neurotransmitter release (neuroexocytosis). The latter point will be expanded to include a model for the assembly of the neuroexocytosis nanomachine, which explains all the presently known aspects of the inhibition of neuroexocytosis by BoNTs.

Cleavage of the SNARE proteins by BoNTs and their use in cell biology and neurophysiology

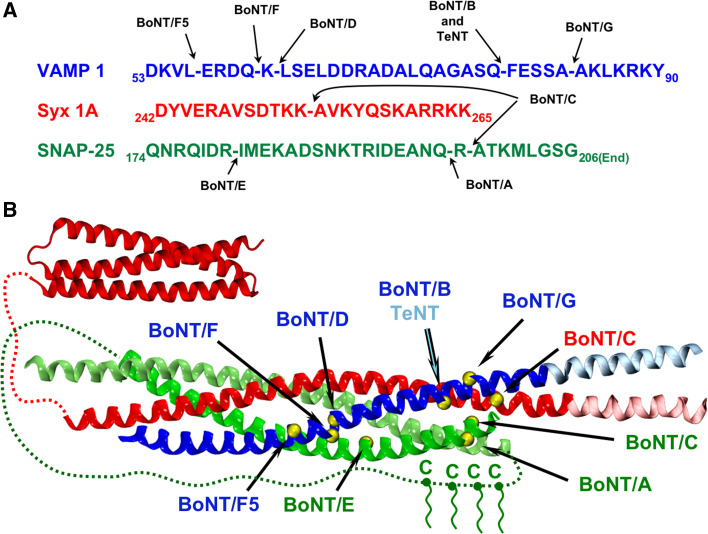

Within a short time from the initial discovery of the single site proteolysis of VAMP/Synaptobrevin by tetanus neurotoxin (TeNT) and BoNT/B [24, 25], all the substrates and their cleavage-sites by the other BoNT L chains were determined [4, 26, 27] (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The SNARE complex and the cleavage sites of BoNTs. a Primary sequences of the three SNARE proteins in the neighborhood of the cleavage site of the different BoNTs. Numbering and sequences here and along the manuscript correspond to mouse (Mus musculus) unless otherwise stated. Gaps in the sequences indicate the peptide bond cleaved by each serotype. b Cartoon representation of the SNARE complex. VAMP, Syntaxin, and SNAP25 are shown in blue, red, and green, respectively. Light colors in VAMP and Syntaxin indicate TM segments, which extend beyond the four-helix bundle of the SNARE complex according the PDB structure 3IPD. Red dashed lines indicate unstructured segments between the N-terminal three-helix bundle of Syntaxin (PDB id: 1EZ3) and the SNARE core domain. The green dashed line represents the long linker existing between the two helices of SNAP25, which contains four conserved palmitoylated cysteines. The yellow spheres correspond to the amino acid before the cleavage point of each serotype. This figure is intended only to provide a comprehensive view of the possible impact of each BoNT on the formation of the SNARE complex. Notice, however, that BoNTs do not cleave the SNAREs when they are engaged in the four-helix bundle

Very recently, BoNT/F isoform 5 was found to cleave VAMP at yet another, different site [28]. Overall, this was a remarkable achievement because it explained the molecular basis of tetanus and botulism, and provided at the same time the most important evidence for the central role of VAMP, SNAP25, and Syntaxin in neuroexocytosis. These proteins were collectively termed SNARE (SNAP REceptors) proteins because they were isolated as a receptor complex of the Soluble NSF Attachment Protein (SNAP) [29]. In addition, this information qualified TeNT and BoNTs as cheap knock-outs of SNARE proteins within the nerve terminal to determine their role in any given process of vesicle to target membrane fusion [4]. These neurophysiologic tools have been largely used and have not yet exhausted their potential (see below). The determination of the sites of cleavage of VAMP and Syntaxin, together with the definition of the assembly of the three SNARE proteins in one heterotrimeric complex (Fig. 2b) [29, 30], led to the understanding of how their proteolytic activity cause neuroparalysis.

Indeed, these cleavages remove such a large portions of VAMP, Syntaxin, and SNAP25 as to prevent the formation of stable SNARE complexes (Fig. 2b), which are essential for the fusion of SV with the nerve plasma membrane. However, this is not the case of BoNT/A that removes only nine residues from the SNAP25 C-terminus. None of the BoNT L chains can cleave the SNARE proteins when they are engaged in the SNARE complex [30, 31].

The cleavage-site selectivity of the L chains is so high that the peptide bonds cleaved by BoNT/F and /D (Fig. 2), and those cleaved by BoNT/A and /C differ by just one residue in VAMP and SNAP25 (Fig. 2), respectively. At the same time, BoNT/C can cleave two SNARE proteins: Syntaxin and SNAP25, at different peptide bonds [32, 33]. This evolutionary diversification of targets, which ensures the neurotoxigenic Clostridia a large array of vital host substrates with the same deadly consequence, can also be performed in the laboratory. As an example, an L chain mutant of BoNT/C which cleaves only Syntaxin and a mutant of the BoNT/A L chain that cleaves SNAP-23, which is a SNAP25 isoform frequently involved in exocytosis in GABAergic neurons [34] and in non-neuronal cells, and not cleaved by BoNT/A, were identified [35, 36].

In search of additional protein substrates of the BoNTs, an extensive yeast two-hybrid search on a nerve tissue library was repeatedly performed using as baits the L chains of BoNT/A and /B mutated at their active sites to make them inactive (Caccin, Rossetto, Rigoni, and Montecucco, unpublished findings), similar to what was done to identify the MAPKK proteins as the substrates of the anthrax lethal factor metalloprotease [37]. This approach did not reveal additional targets of BoNT/A and /B. However, such a negative type of observation does not exclude the remote possibility that the BoNTs may have other substrates.

The defined specificity of action of the BoNTs was rapidly exploited to test for the involvement of the three SNARE proteins not only in neuroexocytosis but also in exocytosis in general (in chromaffin, mast, exo- and endocrine pancreas, hypophysis, and other tissues) [4, 27, 38]. Their use in non neuronal cells is limited by the lack of appropriate receptors, but the L chains can be microinjected or transfected or the cell can be permeabilized [38]. The recent discoveries that TeNT and BoNT/C and /D can bind to a cell provided that it contains polysialogangliosides [39, 40], and that the L chain can be induced to enter from the plasma membrane [41], offers a way to make a non-neuronal cell sensitive to these neurotoxins. The use of BoNTs provided the major experimental contribution to reach the general conclusion that the three SNARE proteins, with one or other of their many isoforms, are always involved in the fusion of a cell vesicle or granule with the target membrane [42, 43]. Judging from the current literature, whilst the therapeutic and clinical experimental uses of BoNT have increased enormously, their employment in cell biology and neurophysiology has somehow diminished with time, though it retains a high potential. For example, recent experimental work has suggested that different events of SV trafficking at the synapse are mediated by different isoforms of VAMP [44–46]. In particular, VAMP-2, -4, and -7 and Vti1a were identified as possible markers of different SVs. From the alignment shown in Fig. 3a, it appears that mouse VAMP-2 is cleaved by TeNT and BoNT/B, /D, /F, /F5, and /G, whilst VAMP-4 is only cleavable by BoNT/D and /F5, but not by the others. VAMP-7 is cleavable by BoNT/D and /F5, and Vti1a is cleavable by BoNT/D and /F, but not by the others. These predictions are based on the nature of the respective scissile bonds, but should be experimentally tested because this is not the sole determinant of BoNT cleavability (see below).

Fig. 3.

Multiple sequence alignment of SNARE proteins. Primary sequences of the entire proteins were collected from the UniProt database (http://www.uniprot.org) and aligned using T-COFFEE at http://www.tcoffee.org/. Only relevant regions around the cleavage sites are shown. Positive, negative and polar amino acids are back shaded in blue, red and green, respectively. a The different variants of VAMP correspond to the following UniProt sequence codes: Q62442 (VAMP1 Mouse), P63044 (VAMP2 Mouse), P63024 (VAMP3 Mouse), O70480 (VAMP4 Mouse), P70280 (VAMP4 Mouse), O89116 (VTI1A Mouse); Q63666 (VAMP1 Rat), P63045 (VAMP2 Rat), P63025 (VAMP3 Rat), D4A560 (VAMP4 Rat); P23763 (VAMP1 Human), P63027 (VAMP2 Human), Q15836 (VAMP3 Human), O75379 (VAMP4 Human); F1NJC6 (VAMP1 Chicken), F1NTL8 (VAMP2 Chicken), F1P4I3 (VAMP3 Chicken) and F1NLG6 (VAMP1 Chicken). b The different variants of Syntaxin correspond to the following UniProt sequence codes: O35526 (Syx1A Mouse), P61264 (Syx1B Mouse), Q00262 (Syx2 Mouse), Q64704 (Syx3 Mouse), P70452 (Syx4 Mouse), Q8K1E0 (Syx5 Mouse); P32851 (Syx1A Rat), P61265 (Syx1B Rat), P50279 (Syx2 Rat), Q08849 (Syx3 Rat), Q08850 (Syx4 Rat), Q08851 (Syx5 Rat); Q16623 (Syx1A Human), P61266 (Syx1B Human), P32856 (Syx2 Human), Q13277 (Syx3 Human), Q12846 (Syx4 Human), Q13190 (Syx5 Human); F1N861 (Syx1A Chicken), O42340 (Syx1B Chicken), F1NW46 (Syx2 Chicken), H9KZA6 (Syx3 Chicken) and Q5ZL19 (Syx6 Chicken). c The variants of SNAP25 (SNAP23 and SNAP29) correspond to the following UniProt sequence codes: P60879 (SNAP25 Mouse), O09044 (SNAP23 Mouse), Q9ERB0 (SNAP29 Mouse); P60881 (SNAP25 Rat), O70377 (SNAP23 Rat), Q9Z2P6 (SNAP29 Rat); P60880 (SNAP25 Human), O00161 (SNAP23 Human), O95721 (SNAP29 Human); P60878 (SNAP25 Chicken), E1BRL4 (SNAP23 Chicken) and F1NYA3 (SNAP29 Chicken)

The same approach could be extended to the large family of Syntaxins (Fig. 3b) and to the variants of SNAP25 (Fig. 3c) using BoNT/A and the mutated BoNT/C mentioned above [35, 47]. The systematic differential use of the diverse BoNTs in conjunction with that of neurons from different portions of the nervous systems of different animal species can provide very reliable information with a simple experimental approach. In addition, it should be noted that variation of the sequence of the isoforms of SNARE proteins in different neurons and animal species can explain their resistance to tetanus or botulism [48] and that the BoNTs are inactive on insect neurons because they do not express the polysialoganglioside receptor.

The metalloprotease enzymatic activity of botulinum neurotoxins: substrate specificity, kinetics and mechanism of proteolysis

The differences in the sequences at and around the various scissile bonds (Fig. 3), together with the close similarity of the BoNT L chains, suggested that the cleaved sites were not the only determinant of the specific recognition of the SNARE proteins [49]. Indeed, the BoNTs were found to also recognize their three protein targets via conserved N-terminal SNARE recognition elements, also termed exosites, present at a distance from the cleavage site and characterized by the presence of three carboxylates on one face [49]. Later on, additional exosites on both sides of the scissile bond were identified [50–54]. These findings explained why the L chains require long sequences of their SNARE substrates for optimal cleavage [33, 50, 55–62]. Indeed, point mutations in these SNARE recognition elements, which are placed at a variable distance from the scissile bond in the three SNARE proteins, drastically affect the rate of cleavage by the various L chains [49, 50, 55–62].

The structural basis of such specificity was clarified by the description of the structure of all L chain serotypes [51–53, 63–69] and by the rather detailed description of the complex between the BoNT/A L chain and segment 147–204 of SNAP25 (Fig. 4a) obtained by the analysis of their co-crystals [51], and of those consisting of a large segment of VAMP (residue 22–58) with the L chain of BoNT/F (Fig. 4b) and of TeNT [68, 69], in addition to the biochemical and mutagenesis experiments quoted above [33, 49, 50, 52–62]. The SNAP25 segment 147–204 folds around the L chain domain with a α-helical motif (amino acids 147–167), which is a major determinant of the substrate recognition by fitting into a hydrophobic elongated cavity present on the L chain surface. This suggests that this is the initial enzyme-substrate recognition that then proceeds with the wrapping of SNAP25 segment 168–200 and the β-strand C-terminal segment 201–204 (Fig. 4a). Both the long N-terminal α-helix and the short C-terminal β-sheet are essential for efficient substrate binding and cleavage, and were termed α- and β-exosites [51]. Several residues of the L chain of BoNT/A are involved in the fine-tuning of the juxtaposition of residues 147–197 [70]. It appears that such an extended enzyme–substrate interaction serves to place the peptide bond to be cleaved exactly close to the Zn2+ ion and the water molecule of the active site (Fig. 4a), but this does not exclude an induced enzyme activation. Certainly, it accounts for the extreme specificity of the L chain of BoNT/A.

Fig. 4.

Interaction between BoNTs and SNARE proteins. a Cartoon representation of the X-ray structure of BoNT/A in complex with SNAP25 (green). The color in the structure of the enzyme varies from red (near the active site) to white (far from the active site). The Zn2+ atom and the catalytic water bound to the active site are shown as violet and yellow spheres, respectively. The metal coordinating residues His223, 227 and Asn224 (corresponding to Glu224, which is mutated in this structure) are shown in sticks. The second shell coordination residues Arg363 and Phe366 (corresponding to Tyr366, mutated in this structure) are also shown in sticks and indicated with black ovals. b Same as (a) for the complex between BoNT/F and VAMP (blue). The position of the catalytic water was not determined in this structure

In this respect, the analysis of the L chain of type C is particularly interesting as it cleaves two substrates: the peptide bonds Lys252-Ala253 in Syntaxin and Arg198-Ala199 in SNAP25, which is next to the one hydrolyzed by BoNT/A (Gln197-Arg198). The L chain of BoNT/C appears to recognize the same remote α-exosite bound by BoNT/A but with a lower stringency; however, what appears to be essential is the presence of a small pocket, near the active site, which only fits the Ala residue of the P1’ residue. Indeed, SNAP25 mutants with the Ala residue replaced by a bulkier one were cleaved at a much lower rate [52]. This pocket is larger in BoNT/A, thus allowing for the fitting of the bulky and charged lateral chain of arginine [71]. Segment 183–190 of SNAP25 complexed to the L chain type A is detached from the metalloprotease surface and could well adjust for the one-residue-shifted positioning of the substrate in the active sites of the L chains of serotype C (Fig. 2). Accordingly, insertion of three extra residues in this loop of SNAP25 had little effect on its rate of cleavage by the L chain type C [52].

This picture of the SNARE substrate making extended interactions with the enzyme appears to be of rather general value, given the overall similar results of the studies on the L chains of BoNT/C [52] and of TeNT and BoNT/B [69]. However, VAMP is positioned in BoNT/F differently from SNAP25 in BoNT/A (Fig. 4) [23, 68]. There are three major exosites in BoNT/F, which differ from those of BoNT/A, and docking of the first exosite is unique in BoNT/F. The loop corresponding to residues 171–180 of BoNT/F is smaller in BoNT/A, and probably causes variation in ligand recognition by exposing different residues to interact with its substrate. The unexpected loop conformation of residues 39–46 of VAMP and the helicity of residues just after it (residues 49–57) produce substantial variations in enzyme binding with respect to SNAP25 (Fig. 4b).

The comparison between the SNARE complex shown in Fig. 2b with the structures of the L chain of BoNT substrate-metalloproteases bound to VAMP or SNAP25, presented in Fig. 4, clearly indicates that these interactions are mutually exclusive. This reinforces the concept expressed above that the BoNT L chains only cleave isolated SNARE protein, i.e. the SNARE complex is poorly sensitive to the proteases when the SNARE domains are fully coil-coiled [30, 31].

The kinetic parameters of the various L chains are different and only a limited and heterogeneous set of data is available, derived from experiments that were performed: (1) in the test tube, (2) under a variety of experimental conditions, (3) using different substrates, and (4) L chains of different lengths, a factor which greatly influences kinetics; for a comparative reading, see Refs. [52, 62, 72–78]. Hence, a comprehensive and homogeneous picture of this aspect of BoNT action is not presently available. Even more important would be a quantitative evaluation of the time course of the SNARE cleavage by the various L chains in vivo, i.e. within the nerve terminal, as the following hints indicate that they may faster proteases in vivo than in vitro: (1) VAMP proteolysis by the L chains of TeNT and BoNT/B is more rapid in the presence of acidic liposomes which mimic the charge of the cytosolic face of SV [79]; (2) BoNT/A L chain binds to the cytosolic face of the nerve plasma membrane, thus greatly increasing the probability of encountering its substrate SNAP25 [80], (3) the L chain of BoNT/C only cleaves Syntaxin when inserted in the membrane [32, 81]; (4) it was estimated that only 4–10 molecules of the TeNT L chain are sufficient to cause a 50 % reduction in neurotransmitter release at the neuromuscular junction (NMJ) of Aplysia californica at room temperature (Bernard Poulain, personal communication; [24]); and (5) less than ten TeNT L chains were estimated to be sufficient to intoxicate chromaffin cells [82]. Similarly, about 10 molecules of BoNT/A are sufficient to cause the blockade of neurotransmitter releases at a frog NMJ [83]. It is also likely that the different toxins may display diverse rates of cleavage when acting on different neurons and in nerve terminals of different animal species. These possibilities, however, remain to be tested. In any case, given these limitations, one has to postpone the discussion on the kinetics of BoNT proteolysis in vivo until more experimental data become available.

The active sites of the BoNT L chains have an elongated shape centered on the Zn2+ atom and are located in a cavity deep inside the L domain; the substrate has to fit in this cavity to be hydrolyzed by the active site-bound water. The Zn2+ cation is coordinated by the two histidines of the strictly conserved HExxH motif, by a water molecule hydrogen-bonded to the E carboxylate of the motif, and by another glutamate further down in the sequence which completes the first shell of coordination (Fig. 4). Therefore, BoNTs belong to the large family of metalloproteases termed gluzincins, whose best-studied representative is thermolysin [84, 85]. A unique feature of the clostridial neurotoxins is the presence in the second shell of coordination of a conserved arginine and a conserved tyrosine (Arg362 and Tyr365 in BoNT/A) whose replacement leads to loss of catalytic activity [72, 86, 87]. This tyrosine residue points the OH group of its phenol ring toward the center of the active site (Fig. 4b) and is also conserved in the anthrax lethal factor metalloprotease [88].

The exact mechanism of hydrolysis of the peptide bond has not been determined for any of the BoNT L chains, but it is believed to be similar to that of thermolysin [53, 54, 72, 89–93]. The binding of the substrate brings the carbonyl oxygen in the P1 position of the scissile peptide bond in such a position to be able to interact with the positive zinc ion, thus polarizing the C–O group of the peptide bond to be cleaved and leaving the C atom more susceptible to a nucleophilic attack by the O atom of the catalytic water molecule. This water is hydrogen-bonded to the glutamate of the HExxH motif and highly polarized, thus becoming capable of attacking the carbonyl carbon of the scissile bond, whilst its hydrogen atom interacts with the nitrogen atom of the peptide bond. This favors its detachment with the consequent formation of an amino group. It is assumed that Arg362 and Tyr365 assists polarization of bonds in such a way as to assist the hydrolysis of the peptide bond, but the precise way in which they act is still to be established, and it is likely that they introduce important differences with respect to the thermolysin mode of action. The fact that Mn2+, in place of Zn2+, in the active site of the L chain of TeNT and anthrax lethal factor supports the proteolytic activity of both enzymes [88, 94, 95], whilst this is not the case for thermolysin [96], is in line with this possibility. Clearly, further experiments are required to fully characterize the enzymatic reaction catalyzed by this unique group of metalloproteases.

Duration of action of the botulinum neurotoxins

A remarkable feature of botulism is its reversibility [3]. If the patient respiration is mechanically supported, he/she recovers, in most cases, completely. In other words, the action of the BoNTs is fully reversible. However, the duration of action depends on BoNT serotypes, animal species (recovery is about three times faster in mice than in humans), and dose [3, 4]. In general, BoNT/A- and BoNT/C-induced paralysis lasts about three times longer than those caused by BoNT/B, /D, /F and /G, whilst BoNT/E causes the shortest paralysis [97–113]. Even considering the short acting L chain of BoNT/E, its lifetime is large as compared to those of most of the eukaryotic intracellular proteins whose life span is usually comprised between few seconds and few days. This long life may be due to the fact that they are bacterial proteins inside an eukaryotic cell as well as to an underlying evolutionary process selecting longer living toxins that ensure a higher chance of killing the intoxicated host. Nerve cell proteins are degraded by the ubiquitin–proteasome and by the lysosome–autophagy pathways [114]. The simplest explanation for the different duration of action of the BoNTs is that recovery from poisoning is related to the lifetime of their L chain inside nerve terminals. In other words, as long as the L chain is present within a nerve terminal, the newly synthesized SNARE protein will continue to be cleaved. Although no lifetimes of any of the BoNT L chain have been measured directly, this interpretation is supported by several experimental observations (for a recent and appropriate discussion, see [115]) and by the very recent report that mutations of the L chain that affect its degradation via the ubiquitin pathway also affect the duration of the blockade of neurotransmitter release [116]. Another important aspect is the subcellular localization of the L chain that may protect it from degradation [115]. On the other hand, experimental evidence indicates that other factors come into play, in addition to the L chain lifetime. These are: (1) the inhibition of autonomic peripheral cholinergic nerve terminals by BoNT/A lasts more than 1 year, and it is difficult to envisage such a long lifetime for the L chain inside a nerve terminal; (2) co-injection of BoNT/A and BoNT/E leads to a short, BoNT/E-type paralysis, rather than a long, BoNT/A-type effect, a finding that is not consistent with the L chain of BoNT/A remaining active for a long time inside the axon terminal of the human Extensor Digitorum Brevis [102, 108]. However, experiments performed in other NMJ of rodents have given different results [105, 110, 111], possibly because of the different experimental protocol and of the different nature of NMJ and glycosilation levels of the SV2 protein receptors for BoNT/A and /E in human and rodents which affects binding affinities; (3) BoNT/A-cleaved SNAP25(1–197), but not the shorter BoNT/E-truncated SNAP25, SNAP25(1–180), forms a stable SNARE complex with VAMP and Syntaxin [30, 31, 117–120]; (4) experiments performed at the frog NMJ showed inhibition of acetylcholine release with virtually no cleavage of SNAP25 by BoNT/A, as detected by immunofluorescence, whilst a relevant cleavage was observed in the case of BoNT/E [121–123]; (5) SNAP25(1–197) has been detected for more than 80 days in cultured mouse spinal cord neurons [111] and it remains within the poisoned NMJ much longer than SNAP25(1–180) [108]; (6) transfected SNAP25(1–197) alone is sufficient to inhibit exocytosis of insulin from insulinoma cells [124] and of glutamate from hippocampal neurons [34], and the release of cathecolamines is lowered in PC12 cell transfected with a SNAP25 mutated in its C-terminus [117]; (7) the rapid and large inhibitory effect on neurotransmitter release in perfused neurons of brainstem slices treated with BoNT/A can be similarly interpreted [125]; and (8) this is more evident in experiments where the dose/responses of the effect of BoNT/A and /E on SNAP25 cleavage and on neurotransmitter release were compared in mice spinal cord motoneurons [126, 127]. The two curves coincided for BoNT/E, whilst they were largely shifted in the case of BoNT/A. These findings were explained with a different time course of entry and action of the two neurotoxins [127]. An alternative physical–chemical interpretation of the BoNT/A finding is that SNAP25 takes part in neuroexocytosis as an oligomer whose number of monomer would be given by the ratio of the respective IC50 values for SNAP25 cleavage and for neurotransmitter release [128]. From references [126, 127], this can be estimated to be 10 ± 2. On the other hand, as SNAP25 does not take part in neuroexocytosis as such, but as a part of the SNARE complex, this result suggests that a set of SNARE complexes cooperates to form the neuroexocytosis nanomachine [128]. That several SNARE complexes may form a super-complex is also suggested by the direct isolation from brain of star-shaped SNARE complexes using a mAb anti-Syntaxin [129].

The core of the neuroexocytosis nanomachine consists of SNARE complexes, complexin and synaptotagmin

An exceptional effort of many laboratories employing a variety of experimental approaches has established that the fundamental components of the neuroexocytosis apparatus consists of multiple copies of the SNARE complex, of Synaptotagmin (or equivalent proteins that act as Ca2+-activated triggers of neuroexocytosis) and of Complexin (CPX), which acts as an organizer/stabilizer of the SNARE complex oligomer [6, 7, 130–132].

As shown in the SNARE complex of Fig. 2b, Syntaxin consists of several parts, an N-terminal three-helix bundle motif regulated by Munc18 [133], a central ~65-residues-long helical region, known as the SNARE domain [134–136], followed by a highly conserved and positively charged linker segment which continues in the C-terminal trans membrane (TM) domain, which anchors it to the plasma membrane, leaving a short, surface-exposed, C-terminus. SNAP25 is formed by two SNARE domains linked by a non-structured polypeptide segment. This linker contains four conserved cysteines, which mediate the attachment of the protein to the cytosolic face of the presynaptic membrane following palmitoylation. VAMP is formed by an unstructured N-terminus linked to the SNARE domain, followed by a highly conserved and positively charged linker segment which continues in a TM helix inserted in the SV membrane, ending with a short intravesicular C-terminus.

The neuronal isoforms of Synaptotagmin consist of several regions (Fig. 5a). It contains an N-terminal intravesicular flexible segment followed by a TM helix (residues 58–79) embedded in the SV membrane, which is linked by a highly conserved positively-charged segment to two homologous C2 domains (called C2A and C2B, spanning residues 143–244 and 274–377). The C2A and C2B domains constitute two independent folding modules linked by an unstructured peptide (residues 245–273), which confers to these two rather rigid objects a reciprocal flexibility [6, 7, 130, 137]. These domains can bind Syntaxin/SNAP25 dimers formed before VAMP attachment in a Ca2+-independent mode during SV docking to the plasma membrane [6, 7, 130, 138–140]. Upon a rise in the local Ca2+ concentration, both C2 motifs coordinate Ca2+ ions and bind to the plasma membrane, interacting with PIP2-enriched microdomains [6, 7, 141, 142]. A combination of X-ray crystallography with FRET studies indicates that interaction with SNAREs complex favors a compact state of both C2 domains. Addition of Ca2+ further strengthens this conformational trend [143]. However, a number of seemingly contradictory results were reported on the interaction between Synaptotagmin and the SNARE complex, suggesting that “Synaptotagmin and the SNAREs form a Complex that is Structurally Heterogeneous” [144–150]. These results may be reconciled by the recent proposal that Synaptotagmin interacts with different regions of the SNARE complex at different times during the neuroxocytosis process [151]. Nevertheless, it seems clear that the basic stretch comprised between residues 321 and 332 within the C2B domain (Fig. 5a) is determinant for the interaction with the SNARE complex, whilst the C2A domain plays only an accessory role [148].

Fig. 5.

Molecular representation of Synaptotagmin and CPX. a Cartoon representation of the Ca2+ bound state of Synaptotagmin based on the X-ray structure 3HN8. The unstructured and TM regions are drawn manually. C2A and C2B domains are shown in dark and light orange, respectively. Both domains are connected by a peptide linker shown in black. Calcium binding sites are indicated by green spheres partially embedded in the presynaptic plasma membrane. The position of Lys324 to 326, at the center of the basic stretch of C2B (see text), is shown as pale blue spheres. b Cartoon representation of CPX based on the X-ray structure 3RL0. Dotted lines indicate unstructured regions. The accessory and central helices are shown in dark and light yellow, respectively

Another component of this machinery is CPX, a small protein of 134 amino acids with a single helical domain flanked by unstructured N- and C-terminal segments (Fig. 5b). Within this domain, the region spanning amino acids 32–48 is known as the accessory helix and displays an inhibitory action on neuroexocytosis, whilst segment 49–70, known as the central helix, has a stimulatory action [152–157].

Syntaxin, SNAP25, and VAMP can spontaneously assemble to create a tight parallel four-helix bundle SNARE complex [136, 158]. In the absence of Synaptotagmin and CPX, helical coiling proceeds from the N-terminal, membrane distal, extremities of the SNARE motifs thus bringing the SV close to the target membrane [130]. This process is exergonic but most of the SNARE coiling energy is released before the two membranes come close enough to fuse. However, it is believed that part of this energy is stored and used in the subsequent membrane fusion step with formation of the fusion pore [6, 7, 130–132]. Membrane fusion is followed by the enlargement of the fusion pore with completion of SNARE zippering until the TM domains of VAMP and Syntaxin are intertwined [159]. Although pure energetic considerations would suggest a plausible mechanism for spontaneous membrane fusion upon random encounters of SNARE proteins [160], the physiological situation absolutely requires a tight control, ensuring that fusion takes place only if and when needed [161]. Indeed, neuroexocytosis involves several steps beginning with the priming and docking of SVs to the active zones, which are organized sites of the presynaptic membrane where neuroexocytosis occurs [161]. Priming and docking on the presynaptic membrane is mediated by several different proteins [6, 7, 133], but MUNC-13 and MUNC-18 appears to play a major role in preventing the formation of non-productive SNAP25/Syntaxin complexes [133]. Different lines of evidence suggest that zippering of the SNARE motif proceeds until nearly half of the four-helix bundle. At this point, CPX binds and brakes the nanomachine before SNARE coiling completes [162–166]. Accordingly, CPX deletion or suppression in Drosophila melanogaster and Caenorhabditis elegans results in a markedly increased rate of spontaneous exocytosis [156, 167, 168]. At the same time, CPX knock-out mice show a reduced rate of spontaneous fusion events [169]. The central helix of CPX binds to and stabilizes the fully assembled SNARE complexes in an antiparallel orientation [170]. Also, Synaptotagmin binds at an intermediate stage of assembly of the neuroexocytosis nanomachine, though its exact positioning is not known; it contributes to the stability of the apparatus which keeps the SV in a prefusion state with the two membranes hemifused, i.e. with the cis monolayer fused and the trans monolayer separated, as proposed for lipid bilayer fusion in general [171].

When an action potential arrives to the motoneuron axon terminal (the main site of action of BoNTs), it opens the voltage-gated Ca2+ channels located at the active zones [172]. Within hundreds of microseconds from Ca2+ entry [173, 174], Synaptotagmin binds calcium and triggers membrane fusion in a process which involves CPX [175]. This cascade of events results in the formation of a fusion pore, which enlarges to mediate a rapid release of neurotransmitter into the intersynaptic space [176–178]. Hundreds of microseconds elapse between localized Ca2+ entry and pore formation at the presynaptic membrane [174]. This very short time scale supports the proposal of the hemifused membranes because the Ca2+-induced fusion of negatively charged liposomes is not so rapid, indicating that a protein conformational change triggers the process of pore formation.

A model for the neuroexocytosis nanomachine that accounts for the actions of botulinum neurotoxins

The central role of the SNARE complex in the neuroexocytosis nanomachine accounts very well for the cytosolic action of BoNT/B, /C, /D, /E, /F, and /G. These neurotoxins remove large portions of the SNARE domain from one of the three SNARE proteins, thus preventing the formation of a stable, fully zippered SNARE complex. There is no evidence that the released VAMP or Syntaxin or SNAP25 fragments play any prolonged role in the blockade of neuroexocytosis, though some experiments employing very large amounts of such fragments have shown acute effects in some cases [115]. However, the nine-residue truncation of SNAP25 by itself does not explain the prolonged inhibition of neuroexocytosis exerted by BoNT/A. As discussed above, comparison between the inhibitory actions of BoNT/A and /E on neurotransmitter release in cultured neurons and at the NMJ suggest that several SNARE complexes participate in this event [121, 126–128] and that a key role in the assembly of the oligomer is played by the C-terminus of SNAP-25 [128].

Because of its general importance, the identification of the components of the nanomachine of neuroexocytosis and the definition of their structural/functional organization is at the focus of the attention of current forefront biomedical research, and has been recently and authoritatively reviewed [6, 7, 130–132, 179], and therefore will not be discussed here. The stoichiometry of SNARE complexes within the neuroexocytosis nanomachine has been investigated in many studies employing a variety of experimental approaches on different experimental systems ranging from model membranes to neurons cells in culture [180]. There is no agreement on the number of SNARE complexes involved in the Ca2+-triggered membrane fusion, which ranges from one to eight [179–187]. However, none of the experimental systems used in those studies included the NMJ. This is the most tightly controlled synapse where an ultrafast neurotransmitter release (hundreds of microseconds) takes place during the evoked synaptic vesicle release leading to muscle contraction [174]. This is the major physiological event blocked by the BoNTs at the NMJ, though they also affect asynchronous release and the miniature end-plate potentials [4, 174].

Considering all available data, we would like to propose a sequence of steps leading to the formation of a radial neuroexocytosis nanomachine, whose features provide an adequate explanation to BoNT/A inhibition. Owing to space limitations, we will consider here only the process of fast neuroexocytosis [174]. We can hypothesize that the initial situation is that of large clusters of complexes formed by Syntaxin and SNAP25 anchored to the cytosolic face of the presynaptic membrane via their TM region and palmitoylated cysteines, respectively. Although the presence of both proteins may result in non-functional 2:1 Syntaxin:SNAP25 complexes [188], recent evidence suggests a key role of the proteins Munc13 and Munc18 in the formation and preservation of the functional 1:1 Syntaxin:SNAP25 adduct [133]. This hetero-dimer serves as an acceptor site for VAMP binding to form the SNARE complex [189]. In this state, the basic residues present at the membrane proximal regions of Syntaxin interact via electrostatic interactions with the strongly anionic lipid phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) clustered around the active zones [190]. The priming of the SV is mediated by the recognition of the N-terminal segments of VAMP and Syntaxin:SNAP25 [191]. Owing to the very large number of Syntaxin:SNAP25 complexes present in the active zones [192], and to the presence of ~70 copies of VAMP in each SV [5], this recognition process may include several protein copies at the same time. An elegant combination of crystallographic and biophysical/biochemical studies has shown that, despite the highly exergonic nature of this process [160], binding of VAMP to the trans SNAREs is stopped at the level of the 60 aa position [164, 193], which coincides with the cleavage point of BoNT/F on VAMP (Fig. 2). Complete SNARE formation is putatively hampered by the presence of the central helix of CPX, which binds to the membrane proximal region of the SNARES [163]. Although the timing of this interaction is uncertain, the zippering of the long parallel four-helix bundle, by generating long parallel α-helical motifs, significantly increases the global dipole moment of the complex [194]. Stabilization of the helix macro dipole has been shown to impact on the folding architecture of coiled-coil helix bundles [195]. The dipole moment of the fully formed Syntaxin:SNAP25 complex is as large as 1,360 Debye (as compared, for instance, with nearly 3 Debye for a single helix turn or a water molecule). Binding of the N-terminal portion of the VAMP helix (residues 26–60, as observed in the structure 3RL0, Fig. 6a) on the Syntaxin:SNAP25 heterodimer further increases the dipole moment of the complex to 1,950 Debye.1Since CPX binds to the SNARE complex in an antiparallel sense, it contributes to reducing the high potential energy associated to the dipole of the complex. Indeed, including the central helix of Complexin (residues 47–70) into the complex results in a reduction of the dipole module to 1,460 Debye, i.e., very close to the value of the trans complex containing only Syntaxin:SNAP25 (Fig. 6a).

Fig. 6.

Model of the neuroexocytosis nanomachine. a Schematic representation of different steps along the construction of the SNARE complex in the presence of CPX, according to the X-ray structure 3RL0. Protein colors are identical to those used in Figs. 2 and 5. The dipole moments of the complex Syntaxin:SNAP25 (top), Syntaxin:SNAP25:VAMP (middle) and Syntaxin:SNAP25:VAMP:CPX (bottom) are indicated by arrows drawn on the same scale. b Top Model of two consecutive SNARE complexes bridged by Synaptotagmin and CPX seen from the side of the SV. The position of CPX is that reported in the X-ray structure 3RL0. The position of Synaptotagmin is uncertain (see main text). The semitransparent yellow helices at both sides of the SNARE complexes indicate binding sites for additional CPX, which may bridge additional SNARE petals. Bottom same model shown on the top panel seen from the membrane proximal (pore) side. c Supramolecular arrangement of the neuroexocytosis nanomachine that resembles a miniaturized radial airplane engine

A quantitative estimation of the inter-SNARE dipole–dipole interaction is difficult since it depends on the inverse of the dielectric permittivity [196], which is virtually impossible to determine in the highly confined, crowded and dynamic environment of the cytosolic face of the presynaptic membrane, close to the active zones. Nevertheless, calculations of the dielectric constant in simulation systems containing realistic membrane models [197], or two parallel membrane patches and only one single SNARE complex at physiological ionic strength, such as the one studied by molecular simulations in Ref. [198], give values of epsilon <40. This suggests that, under physiological conditions, these large dipole moments interact in a low dielectric medium giving rise to significant inter-SNARE interactions. Therefore, the corresponding increase in inter-SNARE dipole–dipole interaction may be detrimental to the concomitant formation of a set of neighboring SNARE complexes. This may favor the transient existence of a number of partially zippered SNARE complexes bound to the central helix of CPX, which may loosely tether a synaptic vesicle to the active zones. Furthermore, a strong dipole–dipole interaction strongly favors the formation of a radial arrangement of partially zippered SNAREs.

As VAMP is present in a large number of copies on the SV surface, a number of half-zippered SNARE complexes are expected to form with a rough radial symmetry in which each individual SNARE complex is blocked by the presence of CPX. Binding of CPX to the nascent SNARE complex is facilitated because of its abundance within nerve terminals [199], and because it is anchored to the SV by an amphipathic helix at its C-terminal domain [200, 201]. The high local concentration and anchoring of the four components to either the plasma membrane or the SV, allows for the spontaneous formation of truncated SNARE complexes.

A major component of the neuroexocytosis nanomachine is Synaptotagmin. This protein is also anchored to the SV by a TM helix linked by a conserved, positively charged, unstructured polypeptide to the two C2 domains (Fig. 5a). However, in contrast with the previously described proteins, Synaptotagmin is present on SV with a stoichiometry of ~1:5 in relation to VAMP, or less [5]. As discussed previously, there is no consensus on the SNARE-Synaptotagmin interactions. Nevertheless, the co-localization imposed by the anchoring to the SV necessarily results in SNARE–Synaptotagmin interactions, even in the absence of Ca2+. Owing to the higher number of SNARES and the relative sizes of the molecules, Synaptotagmin can interact with two SNARE complexes at the same time (Fig. 6b), acting as a ruler. In this conformation, the accessory helix of CPX can bridge the membrane proximal side of the two adjacent SNAREs, which are blocked in the incomplete zippered state by the central helix of CPX (Fig. 6b). This quaternary assembly, comprising one Synaptotagmin, two half-zippered SNAREs and one CPX, is similar to the zigzag arrangement obtained upon crystallization of the SNARE containing truncated VAMP and CPX [163]. However, in the arrangement proposed here, neighboring SNAREs would always present the same orientation, with the membrane proximal segment of Syntaxin and VAMP in contact with the plasma and SV membranes, respectively (Fig. 6c). This appears to be a stringent requirement as: (1) the palmitoylated cysteines in SNAP25 are only five residues away from the SNARE domain; (2) a fast and tight transmission of mechanical work between cytoplasmic and TM helices of VAMP is required to drive membrane fusion [202]; and (3) a salt bridge putatively forms between Arg198 of SNAP25 and Asp250 of Syntaxin in two consecutive SNARE complexes [203, 204]. The BoNT/A-truncated SNAP-25 forms a SNARE complex that may either not incorporate into the oligomer of SNARE complex because of appropriate protein–protein interactions, or it may incorporate because of the prevailing action of CPX and Synaptotagmin, thus generating a non-functional oligomer. It is worth noting that the quaternary arrangement presented in Fig. 6b not only holds together two partially zippered SNARE complexes, one Synaptotagmin and one CPX, but also creates binding sites for the accessory and central helices of additional CPX molecules (see semi-transparent molecules in Fig. 6b), which in turn may recruit additional SNARE complexes in a radial array. Although the numbers can vary in different NMJ, an octameric SNARE rosette results in a suitable geometry for the central/accessory helix of CPX to bridge two consecutive SNARE petals, for the formation of the above mentioned salt bridge between SNAP25 and Syntaxin and leaves room to accommodate Synaptotagmin. At this point, it may be convenient to recall that the distance between SV and plasma membrane in the docked state is in the order of 5 nm [205], limiting the diffusion to a nearly in-plane motion and increasing the probability of additional encountering events. Hence, once the assembly process is started with two consecutive SNAREs intercalated by Synaptotagmin and bridged by CPX, it may rapidly continue even in the absence of Synaptotagmin in the contiguous SNARE complex. Synaptotagmin would help to establish an initial ordering, which can be replicated and stabilized by protein–protein contacts between SNAP25 and Syntaxin (including the Arg–Asp ionic couple mentioned above) and by the central and accessory helices of CPX binding to two neighboring SNARE complexes. It is noteworthy that this explains the stoichiometry of Synaptotagmin/VAMP on the SV membrane [5]. Moreover, the presence of two copies of Synaptotagmin within the neuroexocytosis nanomachine is also in line with electrophysiology measurements, which suggest that 4/5 Ca2+ ions are sufficient to trigger vesicle fusion [206, 207].

The generation of an octameric lipid-SNARE complex would allow for the full coiling of VAMP since the dipole moment of the radial array is zero. Nevertheless, the presence of the CPX accessory helix would still prevent the formation of the fully zippered SNARE complex, acting as a brake. Hence, in the absence of external stimuli, this quaternary arrangement for the fusion machinery remains in a clamped state. The gross dimensions of the radial SNARE complex are in good agreement with experimental estimations of the pore size [174, 176, 177] and intermembrane distances [205]. The separation between opposite petals at the center of an octameric SNARE rosette is ~5 nm (Fig. 6c). Considering that the average area per lipid varies from nearly 0.5 nm2 for phosphatidylserine or phosphatidylethanolamine to 0.9 nm2 for PIP2, about 120 phospholipids plus cholesterol could find places in each monolayer within the center of the SNARE rosette. These lipids can stabilize the highly basic membrane proximal (linker) region of VAMP and Syntaxin and allow for the fusion of the cis monolayers of SV and presynaptic membrane that precedes the opening of the fusion pore [171].

Calcium channels are located close to docked vesicles [208, 209]. Upon stimulation, Ca2+ ions bind to the C2 domains of Synaptotagmin inducing both a change in their interaction with the plasma membrane and with neighboring SNARE complexes inducing a change/rotation on the entire SNARE radial engine with opening of the fusion pore. Such a conformational change/rotation is posited not to take place if the radial complex includes a BoNT/A-truncated SNARE complex because of the lack of the correct protein–protein interaction needed for the conformational change/rotation to take place. Unfortunately, presently available experimental information is insufficient to even speculate about a possible molecular mechanism; however, it makes sense that this conformational/rotational change detaches CPX from the neighboring SNARE petal, inducing the transition of CPX to the post-fusion state determined by X-rays diffraction [170], in which CPX is completely aligned with the four–helix bundle. During the transition to the post-fusion state, mechanical work is transmitted through the helices of Syntaxin and VAMP, while going to the fully zippered conformation [170]. CPX may also favor the extension of the SNAREs helices leading to a continuous topology of cytoplasmic and TM helices as shown by crystallographic studies (Fig. 2b) [159], with enlargement of the pore. In fact, during this transition, the SNARE petals must separate to avoid steric clashes between TM helices. This motion exposes the acidic residues at the C-terminal region of SNAP25, which can interact with Synaptotagmin [148], stabilizing the enlarged pore.

Concluding remarks

The model presented here for the neuroexocytosis nanomachine provides a consistent explanation for the effect of all clostridial toxins, in particular, the important case of BoNT/A which is the one almost always used in human therapy. In fact, the loss of the C-terminal segment of SNAP25 prevents functional protein–protein contacts among neighboring SNARE complexes, which are essential for the correct assembly/function of the neuroexocytosis nanomachine. This explains the negative dominant effect of BoNT/A and provides a figure for the number of SNARE complexes involved in one neuroexocytosis event at the NMJ, which is very close to that discussed above [127, 128, 130]. The present model also explains why overexpression of BoNT/A-resistant SNAP25 rescues the inhibition caused by BoNT/A [210], because a large number of intact SNAP25 molecules compete favorably for entry into the octameric SNARE super-complex with respect to the truncated SNAP25.

Moreover, this model for the neuroexocytosis nanomachine is in agreement with that recently proposed by Hernandez et al. [162], in which “(1) tightly docked liposomes are a result of partial zippering; (2) assembly beyond the +7 layer of the SNARE complex is essential for generating extended hemifusion and fusion; (3) in line with directional N- to C-terminal assembly, the tight bilayer arrangement with extended contact zones represents an intermediate state that was stalled on its way to fusion”. The only disagreement is on the suggestion that “complexes are arrested in trans and are probably distantly distributed”. While this assumption can be valid for the reconstituted liposomes, where CPX is absent, it is unlikely to hold in a physiological context in the light of the fact that replacing Arg198 (the first residue removed by BoNT/A and pointing out the SNARE complex) with an Ala residue is sufficient to cause a defined reduction of neuroexocytosis at the NMJ of Drosophila melanogaster larvae [204]. Arg198 is likely to form a salt bridge with Syntaxin Asp250 of a neighboring SNARE complex [203]. Mutation of these residues leads to a decreased release of neurotransmitters, thus providing initial evidence in support of the model discussed here.

Abbreviations

- BoNT

Botulinum neurotoxin

- NMJ

Neuromuscular junction

- PIP2

Phosphatidylinositol 4,5 diphosphate

- SNAP25

Synaptosomal associate protein of 25 kDa

- SNARE

SNAP REceptors

- SV

Synaptic vesicle

- TeNT

Tetanus neurotoxin

- TM

Trans membrane domain

- VAMP

Vesicle-associated membrane protein or synaptobrevin

Footnotes

The dipole moments were calculated from the PDB structure 3RL0 using the partial charge distribution of the AMBER99 force field. We considered residues 191–249 of Syntaxin and 8–79 to 139–200 in SNAP25 (corresponding the chains B, C, and D in the PDB structure, respectively). Chains A (VAMP) and g (Complexin) were subsequently included to estimate their contribution to the global dipole moment of the SNARE at different stages.

Contributor Information

Sergio Pantano, Email: spantano@pasteur.edu.uy.

Cesare Montecucco, Email: cesare.montecucco@unipd.it.

References

- 1.Hill KK, Smith TJ. Genetic diversity within Clostridium botulinum serotypes, botulinum neurotoxin gene clusters and toxin subtypes. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2013;364:1–20. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-33570-9_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson EA, Montecucco C. Botulism. Handb Clin Neurol. 2008;91:333–368. doi: 10.1016/S0072-9752(07)01511-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caleo M, Schiavo G. Central effects of tetanus and botulinum neurotoxins. Toxicon. 2009;54:593–599. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2008.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schiavo G, Matteoli M, Montecucco C. Neurotoxins affecting neuroexocytosis. Physiol Rev. 2000;80:717–766. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.2.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takamori S, Holt M, Stenius K, Lemke EA, Gronborg M, Riedel D, Urlaub H, Schenck S, Brugger B, Ringler P, Muller SA, Rammner B, Grater F, Hub JS, De Groot BL, Mieskes G, Moriyama Y, Klingauf J, Grubmuller H, Heuser J, Wieland F, Jahn R. Molecular anatomy of a trafficking organelle. Cell. 2006;127:831–846. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sudhof TC, Rizo J. Synaptic vesicle exocytosis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3:a005637. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a005637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jahn R, Fasshauer D. Molecular machines governing exocytosis of synaptic vesicles. Nature. 2012;490:201–207. doi: 10.1038/nature11320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gill DM. Bacterial toxins: a table of lethal amounts. Microbiol Rev. 1982;46:86–94. doi: 10.1128/mr.46.1.86-94.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Possession, use, and transfer of select agents and toxins. Fed Regist. 2012;77(194):61083–61115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson EA. Clostridial toxins as therapeutic agents: benefits of nature’s most toxic proteins. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1999;53:551–575. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.53.1.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Montecucco C, Molgo J. Botulinal neurotoxins: revival of an old killer. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2005;5:274–279. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davletov B, Bajohrs M, Binz T. Beyond BOTOX: advantages and limitations of individual botulinum neurotoxins. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:446–452. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhidayasiri R, Truong DD. Expanding use of botulinum toxin. J Neurol Sci. 2005;235:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2005.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dressler D. Clinical applications of botulinum toxin. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2012;15:325–336. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lacy DB, Stevens RC. Sequence homology and structural analysis of the clostridial neurotoxins. J Mol Biol. 1999;291:1091–1104. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swaminathan S, Eswaramoorthy S. Structural analysis of the catalytic and binding sites of Clostridium botulinum neurotoxin B. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:693–699. doi: 10.1038/78005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumaran D, Eswaramoorthy S, Furey W, Navaza J, Sax M, Swaminathan S. Domain organization in Clostridium botulinum neurotoxin type E is unique: its implication in faster translocation. J Mol Biol. 2009;386:233–245. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Binz T, Rummel A. Cell entry strategy of clostridial neurotoxins. J Neurochem. 2009;109:1584–1595. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Montecucco C, Papini E, Schiavo G. Bacterial protein toxins penetrate cells via a four-step mechanism. FEBS Lett. 1994;346:92–98. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00449-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Montecucco C, Schiavo G. Structure and function of tetanus and botulinum neurotoxins. Q Rev Biophys. 1995;28:423–472. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500003292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Montal M. Botulinum neurotoxin: a marvel of protein design. Annu Rev Biochem. 2010;79:591–617. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.051908.125345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Montal M. Translocation of botulinum neurotoxin light chain protease by the heavy chain protein-conducting channel. Toxicon. 2009;54:565–569. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2008.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Swaminathan S. Molecular structures and functional relationships in clostridial neurotoxins. FEBS J. 2011;278:4467–4485. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schiavo G, Poulain B, Rossetto O, Benfenati F, Tauc L, Montecucco C. Tetanus toxin is a zinc protein and its inhibition of neurotransmitter release and protease activity depend on zinc. EMBO J. 1992;11:3577–3583. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05441.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schiavo G, Benfenati F, Poulain B, Rossetto O, de Polverino LP, DasGupta BR, Montecucco C. Tetanus and botulinum-B neurotoxins block neurotransmitter release by proteolytic cleavage of synaptobrevin. Nature. 1992;359:832–835. doi: 10.1038/359832a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Niemann H, Blasi J, Jahn R. Clostridial neurotoxins: new tools for dissecting exocytosis. Trends Cell Biol. 1994;4:179–185. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(94)90203-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Humeau Y, Doussau F, Grant NJ, Poulain B. How botulinum and tetanus neurotoxins block neurotransmitter release. Biochimie. 2000;82:427–446. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(00)00216-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kalb SR, Baudys J, Webb RP, Wright P, Smith TJ, Smith LA, Fernandez R, Raphael BH, Maslanka SE, Pirkle JL, Barr JR. Discovery of a novel enzymatic cleavage site for botulinum neurotoxin F5. FEBS Lett. 2012;586:109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.11.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sollner T, Whiteheart SW, Brunner M, Erdjument-Bromage H, Geromanos S, Tempst P, Rothman JE. SNAP receptors implicated in vesicle targeting and fusion. Nature. 1993;362:318–324. doi: 10.1038/362318a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hayashi T, McMahon H, Yamasaki S, Binz T, Hata Y, Sudhof TC, Niemann H. Synaptic vesicle membrane fusion complex: action of clostridial neurotoxins on assembly. EMBO J. 1994;13:5051–5061. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06834.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pellegrini LL, O’Connor V, Betz H. Fusion complex formation protects synaptobrevin against proteolysis by tetanus toxin light chain. FEBS Lett. 1994;353:319–323. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)01070-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schiavo G, Shone CC, Bennett MK, Scheller RH, Montecucco C. Botulinum neurotoxin type C cleaves a single Lys-Ala bond within the carboxyl-terminal region of syntaxins. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:10566–10570. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.18.10566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vaidyanathan VV, Yoshino K, Jahnz M, Dorries C, Bade S, Nauenburg S, Niemann H, Binz T. Proteolysis of SNAP-25 isoforms by botulinum neurotoxin types A, C, and E: domains and amino acid residues controlling the formation of enzyme-substrate complexes and cleavage. J Neurochem. 1999;72:327–337. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0720327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Verderio C, Pozzi D, Pravettoni E, Inverardi F, Schenk U, Coco S, Proux-Gillardeaux V, Galli T, Rossetto O, Frassoni C, Matteoli M. SNAP-25 modulation of calcium dynamics underlies differences in GABAergic and glutamatergic responsiveness to depolarization. Neuron. 2004;41:599–610. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00077-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang D, Zhang Z, Dong M, Sun S, Chapman ER, Jackson MB. Syntaxin requirement for Ca2+ -triggered exocytosis in neurons and endocrine cells demonstrated with an engineered neurotoxin. Biochemistry. 2011;50:2711–2713. doi: 10.1021/bi200290p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen S, Barbieri JT. Engineering botulinum neurotoxin to extend therapeutic intervention. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:9180–9184. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903111106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vitale G, Pellizzari R, Recchi C, Napolitani G, Mock M, Montecucco C. Anthrax lethal factor cleaves the N-terminus of MAPKKs and induces tyrosine/threonine phosphorylation of MAPKs in cultured macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;248:706–711. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ahnert-Hilger G, Munster-Wandowski A, Holtje M. Synaptic vesicle proteins: targets and routes for botulinum neurotoxins. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2013;364:159–177. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-33570-9_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karalewitz AP, Kroken AR, Fu Z, Baldwin MR, Kim JJ, Barbieri JT. Identification of a unique ganglioside binding loop within botulinum neurotoxins C and D-SA. Biochemistry. 2010;49:8117–8126. doi: 10.1021/bi100865f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Strotmeier J, Gu S, Jutzi S, Mahrhold S, Zhou J, Pich A, Eichner T, Bigalke H, Rummel A, Jin R, Binz T. The biological activity of botulinum neurotoxin type C is dependent upon novel types of ganglioside binding sites. Mol Microbiol. 2011;81:143–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pirazzini M, Rossetto O, Bolognese P, Shone CC, Montecucco C. Double anchorage to the membrane and intact inter-chain disulfide bond are required for the low pH induced entry of tetanus and botulinum neurotoxins into neurons. Cell Microbiol. 2011;13:1731–1743. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2011.01654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hong W. SNAREs and traffic. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1744:120–144. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2005.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rossi V, Picco R, Vacca M, D’Esposito M, D’Urso M, Galli T, Filippini F. VAMP subfamilies identified by specific R-SNARE motifs. Biol Cell. 2004;96:251–256. doi: 10.1016/j.biolcel.2003.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hua Z, Leal-Ortiz S, Foss SM, Waites CL, Garner CC, Voglmaier SM, Edwards RH. v-SNARE composition distinguishes synaptic vesicle pools. Neuron. 2011;71:474–487. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ramirez DM, Khvotchev M, Trauterman B, Kavalali ET. Vti1a identifies a vesicle pool that preferentially recycles at rest and maintains spontaneous neurotransmission. Neuron. 2012;73:121–134. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.10.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Raingo J, Khvotchev M, Liu P, Darios F, Li YC, Ramirez DM, Adachi M, Lemieux P, Toth K, Davletov B, Kavalali ET. VAMP4 directs synaptic vesicles to a pool that selectively maintains asynchronous neurotransmission. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:738–745. doi: 10.1038/nn.3067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ramirez DM, Kavalali ET. The role of non-canonical SNAREs in synaptic vesicle recycling. Cell Logist. 2012;2:20–27. doi: 10.4161/cl.20114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Patarnello T, Bargelloni L, Rossetto O, Schiavo G, Montecucco C. Neurotransmission and secretion. Nature. 1993;364:581–582. doi: 10.1038/364581b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rossetto O, Schiavo G, Montecucco C, Poulain B, Deloye F, Lozzi L, Shone CC. SNARE motif and neurotoxins. Nature. 1994;372:415–416. doi: 10.1038/372415a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cornille F, Martin L, Lenoir C, Cussac D, Roques BP, Fournie-Zaluski MC. Cooperative exosite-dependent cleavage of synaptobrevin by tetanus toxin light chain. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:3459–3464. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.6.3459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Breidenbach MA, Brunger AT. Substrate recognition strategy for botulinum neurotoxin serotype A. Nature. 2004;432:925–929. doi: 10.1038/nature03123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jin R, Sikorra S, Stegmann CM, Pich A, Binz T, Brunger AT. Structural and biochemical studies of botulinum neurotoxin serotype C1 light chain protease: implications for dual substrate specificity. Biochemistry. 2007;46:10685–10693. doi: 10.1021/bi701162d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brunger AT, Rummel A. Receptor and substrate interactions of clostridial neurotoxins. Toxicon. 2009;54:550–560. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2008.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Binz T, Sikorra S, Mahrhold S. Clostridial neurotoxins: mechanism of SNARE cleavage and outlook on potential substrate specificity reengineering. Toxins (Basel) 2010;2:665–682. doi: 10.3390/toxins2040665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Foran P, Shone CC, Dolly JO. Differences in the protease activities of tetanus and botulinum B toxins revealed by the cleavage of vesicle-associated membrane protein and various sized fragments. Biochemistry. 1994;33:15365–15374. doi: 10.1021/bi00255a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schmidt JJ, Bostian KA. Proteolysis of synthetic peptides by type A botulinum neurotoxin. J Protein Chem. 1995;14:703–708. doi: 10.1007/BF01886909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pellizzari R, Rossetto O, Lozzi L, Giovedi’ S, Johnson E, Shone CC, Montecucco C. Structural determinants of the specificity for synaptic vesicle-associated membrane protein/synaptobrevin of tetanus and botulinum type B and G neurotoxins. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:20353–20358. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.34.20353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pellizzari R, Mason S, Shone CC, Montecucco C. The interaction of synaptic vesicle-associated membrane protein/synaptobrevin with botulinum neurotoxins D and F. FEBS Lett. 1997;409:339–342. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00482-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wictome M, Rossetto O, Montecucco C, Shone CC. Substrate residues N-terminal to the cleavage site of botulinum type B neurotoxin play a role in determining the specificity of its endopeptidase activity. FEBS Lett. 1996;386:133–136. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00431-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Washbourne P, Pellizzari R, Baldini G, Wilson MC, Montecucco C. Botulinum neurotoxin types A and E require the SNARE motif in SNAP-25 for proteolysis. FEBS Lett. 1997;418:1–5. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01328-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chen S, Barbieri JT. Unique substrate recognition by botulinum neurotoxins serotypes A and E. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:10906–10911. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513032200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sikorra S, Henke T, Galli T, Binz T. Substrate recognition mechanism of VAMP/synaptobrevin-cleaving clostridial neurotoxins. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:21145–21152. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800610200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Agarwal R, Binz T, Swaminathan S. Structural analysis of botulinum neurotoxin serotype F light chain: implications on substrate binding and inhibitor design. Biochemistry. 2005;44:11758–11765. doi: 10.1021/bi0510072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Breidenbach MA, Brunger AT. 2.3 A crystal structure of tetanus neurotoxin light chain. Biochemistry. 2005;44:7450–7457. doi: 10.1021/bi050262j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Arndt JW, Yu W, Bi F, Stevens RC. Crystal structure of botulinum neurotoxin type G light chain: serotype divergence in substrate recognition. Biochemistry. 2005;44:9574–9580. doi: 10.1021/bi0505924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Arndt JW, Chai Q, Christian T, Stevens RC. Structure of botulinum neurotoxin type D light chain at 1.65 A resolution: repercussions for VAMP-2 substrate specificity. Biochemistry. 2006;45:3255–3262. doi: 10.1021/bi052518r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Segelke B, Knapp M, Kadkhodayan S, Balhorn R, Rupp B. Crystal structure of Clostridium botulinum neurotoxin protease in a product-bound state: evidence for noncanonical zinc protease activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:6888–6893. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400584101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Agarwal R, Schmidt JJ, Stafford RG, Swaminathan S. Mode of VAMP substrate recognition and inhibition of Clostridium botulinum neurotoxin F. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:789–794. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rao KN, Kumaran D, Binz T, Swaminathan S. Structural analysis of the catalytic domain of tetanus neurotoxin. Toxicon. 2005;45:929–939. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2005.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fang H, Luo W, Henkel J, Barbieri J, Green N. A yeast assay probes the interaction between botulinum neurotoxin serotype B and its SNARE substrate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:6958–6963. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510816103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Silvaggi NR, Boldt GE, Hixon MS, Kennedy JP, Tzipori S, Janda KD, Allen KN. Structures of Clostridium botulinum Neurotoxin Serotype A Light Chain complexed with small-molecule inhibitors highlight active-site flexibility. Chem Biol. 2007;14:533–542. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Binz T, Bade S, Rummel A, Kollewe A, Alves J. Arg(362) and Tyr(365) of the botulinum neurotoxin type a light chain are involved in transition state stabilization. Biochemistry. 2002;41:1717–1723. doi: 10.1021/bi0157969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tonello F, Pellizzari R, Pasqualato S, Grandi G, Peggion E, Montecucco C. Recombinant and truncated tetanus neurotoxin light chain: cloning, expression, purification, and proteolytic activity. Protein Expr Purif. 1999;15:221–227. doi: 10.1006/prep.1998.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chen S, Karalewitz AP, Barbieri JT. Insights into the different catalytic activities of Clostridium neurotoxins. Biochemistry. 2012;51:3941–3947. doi: 10.1021/bi3000098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chen S, Barbieri JT. Multiple pocket recognition of SNAP25 by botulinum neurotoxin serotype E. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:25540–25547. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701922200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chen S, Hall C, Barbieri JT. Substrate recognition of VAMP-2 by botulinum neurotoxin B and tetanus neurotoxin. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:21153–21159. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800611200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Henkel JS, Jacobson M, Tepp W, Pier C, Johnson EA, Barbieri JT. Catalytic properties of botulinum neurotoxin subtypes A3 and A4. Biochemistry. 2009;48:2522–2528. doi: 10.1021/bi801686b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chen S, Wan HY. Molecular mechanisms of substrate recognition and specificity of botulinum neurotoxin serotype F. Biochem J. 2011;433:277–284. doi: 10.1042/BJ20101310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Caccin P, Rossetto O, Rigoni M, Johnson E, Schiavo G, Montecucco C. VAMP/synaptobrevin cleavage by tetanus and botulinum neurotoxins is strongly enhanced by acidic liposomes. FEBS Lett. 2003;542:132–136. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00365-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fernandez-Salas E, Steward LE, Ho H, Garay PE, Sun SW, Gilmore MA, Ordas JV, Wang J, Francis J, Aoki KR. Plasma membrane localization signals in the light chain of botulinum neurotoxin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:3208–3213. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400229101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Blasi J, Chapman ER, Yamasaki S, Binz T, Niemann H, Jahn R. Botulinum neurotoxin C1 blocks neurotransmitter release by means of cleaving HPC-1/syntaxin. EMBO J. 1993;12:4821–4828. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06171.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Erdal E, Bartels F, Binscheck T, Erdmann G, Frevert J, Kistner A, Weller U, Wever J, Bigalke H. Processing of tetanus and botulinum A neurotoxins in isolated chromaffin cells. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1995;351:67–78. doi: 10.1007/BF00169066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Boroff DA, CJ del, Evoy WH, Steinhardt RA. Observations on the action of type A botulinum toxin on frog neuromuscular junctions. J Physiol. 1974;240:227–253. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1974.sp010608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rawlings ND, Salvesen GS. Handbook of proteolytic enzymes. Oxford: Academic; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 85.http://merops.sanger.ac.uk

- 86.Rigoni M, Caccin P, Johnson EA, Montecucco C, Rossetto O. Site-directed mutagenesis identifies active-site residues of the light chain of botulinum neurotoxin type A. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;288:1231–1237. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rossetto O, Caccin P, Rigoni M, Tonello F, Bortoletto N, Stevens RC, Montecucco C. Active-site mutagenesis of tetanus neurotoxin implicates TYR-375 and GLU-271 in metalloproteolytic activity. Toxicon. 2001;39:1151–1159. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(00)00252-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tonello F, Montecucco C. The anthrax lethal factor and its MAPK kinase-specific metalloprotease activity. Mol Aspects Med. 2009;30:431–438. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Matthews BW. Structural basis of the action of thermolysin and related zinc peptidases. Acc Chem Res. 1988;21:333–340. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Li L, Binz T, Niemann H, Singh BR. Probing the mechanistic role of glutamate residue in the zinc-binding motif of type A botulinum neurotoxin light chain. Biochemistry. 2000;39:2399–2405. doi: 10.1021/bi992321x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Agarwal R, Eswaramoorthy S, Kumaran D, Binz T, Swaminathan S. Structural analysis of botulinum neurotoxin type E catalytic domain and its mutant Glu212–> Gln reveals the pivotal role of the Glu212 carboxylate in the catalytic pathway. Biochemistry. 2004;43:6637–6644. doi: 10.1021/bi036278w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Eswaramoorthy S, Kumaran D, Keller J, Swaminathan S. Role of metals in the biological activity of Clostridium botulinum neurotoxins. Biochemistry. 2004;43:2209–2216. doi: 10.1021/bi035844k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Silvaggi NR, Wilson D, Tzipori S, Allen KN. Catalytic features of the botulinum neurotoxin A light chain revealed by high resolution structure of an inhibitory peptide complex. Biochemistry. 2008;47:5736–5745. doi: 10.1021/bi8001067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tonello F, Schiavo G, Montecucco C. Metal substitution of tetanus neurotoxin. Biochem J. 1997;322(Pt 2):507–510. doi: 10.1042/bj3220507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]