Abstract

A characteristic histological feature of striated muscle cells is the presence of deep invaginations of the plasma membrane (sarcolemma), most commonly referred to as T-tubules or the transverse-axial tubular system (TATS). TATS mediates the rapid spread of the electrical signal (action potential) to the cell core triggering Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum, ultimately inducing myofilament contraction (excitation–contraction coupling). T-tubules, first described in vertebrate skeletal muscle cells, have also been recognized for a long time in mammalian cardiac ventricular myocytes, with a structure and a function that in recent years have been shown to be far more complex and pivotal for cardiac function than initially thought. Renewed interest in T-tubule function stems from the loss and disorganization of T-tubules found in a number of pathological conditions including human heart failure (HF) and dilated and hypertrophic cardiomyopathies, as well as in animal models of HF, chronic ischemia and atrial fibrillation. Disease-related remodeling of the TATS leads to asynchronous and inhomogeneous Ca2+-release, due to the presence of orphan ryanodine receptors that have lost their coupling with the dihydropyridine receptors and are either not activated or activated with a delay. Here, we review the physiology of the TATS, focusing first on the relationship between function and structure, and then describing T-tubular remodeling and its reversal in disease settings and following effective therapeutic approaches.

Keywords: T-tubules, Calcium-induced calcium release, Action potential propagation, Cardiac diseases, T-tubular remodeling

Physiological properties of the TATS

T-tubules are transverse invaginations of the surface sarcolemma (SS) that occur in mammalian heart ventricles at each Z-line and branch within the cell to form a complex network with predominantly transverse elements but also longitudinal (axial) components running from one Z-line to the next (see Fig. 1a) [1]. This complex tubular structure is commonly referred as the T-system or, also highlighting the presence of the longitudinal components, the transverse-axial tubular system (TATS). TATS ensures rapid and homogeneous propagation of the action potential (AP) into the cell interior [2], eventually inducing myofilament contraction (excitation–contraction coupling, ECC) [3]. During the AP, Ca2+ enters the cell through depolarization-activated Ca2+ channels known as dihydropyridine receptors (DHPRs). Ca2+ entry triggers Ca2+ release (calcium-induced calcium release, CICR) from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), where a large amount of Ca2+ is stored [4]. The ryanodine receptor (RyR) is the main SR Ca2+ release channel [5]. The combination of external Ca2+ influx and release from the SR raises the free intracellular Ca2+ concentration allowing Ca2+ to bind to the myofilament protein troponin C, which then switches on the contractile machinery. Afterwards, the SR Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) and sarcolemmal Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX) lower the intracellular Ca2+ concentration [4] allowing muscle relaxation.

Fig. 1.

TATS in cardiac myocytes. a Three-dimensional reconstruction of TATS from confocal microscopy images in a rat ventricular cardiomyocyte. Modified from [108]. b Confocal images of myocytes labeled with membrane dyes and transverse line scans showing intracellular Ca2+. Loss of functional T-tubules (lower panels), obtained with formamide osmotic shock in isolated myocytes, determines an inhomogeneous Ca2+ release throughout the cell, with delayed Ca2+ transient rise in the cell core. Modified from [73]. c Two-photon image of a portion of sarcolemma labeled with di-4-ANEFFPTEA. The membrane is rapidly scanned using the RAMP system at the three sites marked and voltage variations are recorded while pacing the myocyte. Of note, SS, TT and AT do not show any differences in the shape of locally recorded APs. d Average amplitude of voltage variations at SS, TT and AT. Modified from [23]. The fluorescence TATS images are shown inverted with contrast and threshold modified from the original version to make the T-system uniform and comparable among different panels

Immunohistochemical studies have recently shown that many of the key sarcolemma proteins involved in ECC, including DHPRs and NCX, are predominantly located at the tubular network [6, 7]. DHPRs are in very close proximity to RyR clusters in the terminal cisternae of the SR whilst NCX co-localization with RyRs is still debated [8, 9]. This organization is crucial in ensuring a homogeneous Ca2+-release throughout the cell, providing synchronous myofilaments contraction. Technically, however, the resolution of confocal microscopy is not adequate for mapping the complex geometry of TATS, preventing a quantitative interpretation of immunofluorescence data. Additionally, immunohistochemistry is unable to report protein function, which depends not only on the presence of the protein, but also on membrane insertion, local environment, accessory proteins and protein regulation. A complementary approach to probe the channel distribution exploited the restricted diffusion space within the tubular lumen. When applying a rapid change of the bathing solution, some currents showed an initial fast change, attributable to the channels located in the SS, followed by a slower phase representing the contribution of channels in the TATS [10]. Such experiments suggest that 64 % of Na+ and Ca2+ currents (I Na and I Ca) are within the TATS. An alternative method to determine currents distribution is provided by detubulation, a technique recently described and validated in isolated ventricular myocytes to physically and functionally uncouple the TATS from the SS. This procedure has shown that acute uncoupling of TATS from SS alters the amplitude and timing of Ca2+-release (Fig. 1b) highlighting the crucial role of TATS in guaranteeing a synchronous and complete activation of all Ca2+-release units. Comparison of the loss of cell capacitance (a function of membrane area) with the loss of membrane currents following detubulation enables to calculate the fraction of the TATS membrane currents. This investigation points out that many membrane currents, including L-type Ca2+ channel (LTCC) and NCX, appear to occur predominantly in TATS [11, 12]. The electrochemical gradient for AP-relevant ions may also be different across TATS and SS because the tubular network represents a restricted diffusional space, thus ion concentration in the tubular lumen may vary with respect to bulk extracellular concentration [13, 14]. In line with these considerations, the AP of detubulated ventricular myocytes was shorter than that of intact myocytes [15], suggesting that the loss of tubules is associated with a reduction of inward currents, such as I Ca and inward I NCX.

TATS was modeled as a single compartment separated from the SS by the mean resistance of the tubular system (R st) [16]. The contribution of one tubule to R st was expressed as the resistance of a cylindrical conductor, whose length, radius, and specific resistivity corresponded to one-half of the tubular effective length (l/2), its average radius (r), and the specific resistivity of the extracellular solution (ρ), respectively. TATS represents a parallel combination of all (n) tubules in the model cell, the mean resistance of the tubular system can be calculated from the relationship:

| 1 |

Starting from this simple application of the second Ohm law, a biophysically realistic computer model of a cardiac cell was created [17], incorporating the TATS compartment and the current distributions determined using detubulation [18]. The model highlighted a negligible difference of AP amplitude and kinetics between SS and TATS. This model, however, exhibits some limitations due to the simplistic assumption that a tubule is a single isolated compartment and not a portion of a complex network, profoundly affected by events occurring elsewhere in the system itself. Such mathematical model does not address important issues. For instance, it is not possible to mimic how the AP is propagated when a tubule has a stricture or when it branches to form an axial component.

The experimental investigation of the electrical properties of different portions of the sarcolemma requires a direct measure of tubular AP. Although current optical techniques for probing membrane potential allow recording of voltage changes at subcellular level [19], most approaches lack the spatial–temporal resolution and signal-to-noise ratio needed for regional assessment of AP profile in multiple positions. Recently, a new imaging method (RAMP) [20, 21] has been developed to simultaneously record APs at multiple sarcolemmal sites with submillisecond temporal and submicrometer spatial resolution [22, 23]. The RAMP microscope was used to rapidly scan linear segments of different membrane domains and perform multiplexed measurements of the two-photon fluorescence (TPF) signal. Fig. 1c shows an example of real-time and simultaneous optical recording of ten elicited APs from three different membrane sites: surface sarcolemma (SS, red), T-tubule (TT, green), and axial tubule (AT, blue). Figure 1d shows that AP amplitude measured in the TATS is not statistically different from that on SS. Measurements at a high stimulation frequency were also performed to test possible effects of local AP alterations due to cumulative changes in TATS luminal ion concentration (e.g., Ca2+ depletion and K+ accumulation). The uniformity of AP in all sarcolemma domains is maintained even at high pacing rates, proving the tight electrical coupling between membrane domains assumed in theoretical modeling.

The structure of the TATS

The first observations of cardiac T-tubules date back to the 1950s [1]. Studies on mammalian ventricular myocytes confirmed that structure and function of cardiac T-tubules is similar to those of skeletal muscle. Some structural differences can, however, be highlighted. The cardiac T-tubules have a wide lumen, they contain a visible extension of the basal lamina, and have wide rather than restricted openings. The skeletal muscle T-tubules, at least in vertebrates, have a narrow lumen, particularly in the segments between triads, they have an apparently empty lumen, and they are connected to the SS mostly thorough narrow restricted passages [24].

An increasing body of observations has revealed a very high complexity of the cardiac tubules in terms of structural diversity and dynamics (both in physiological and pathological conditions). Firstly, cardiac tubules have a complicated topology. Electron microscopy (EM), in combination with the use of horseradish peroxidase to label the extracellular space [25], revealed that, in rat ventricular myocytes, tubules run not only transversally to the myofilaments’ direction but also longitudinally (Figs. 1a, 2a), with numerous branchings leading to the formation of a complex network of transverse and axial elements, the TATS. The topographical extension of cardiac tubules beyond the Z-line profiles potentially creates a large variability in the location and morphology of tubule-SR junctions. Figure 2b shows the ultrastructure of a typical T-SR junction. The relationship between SR and the tubular network will be discussed further below.

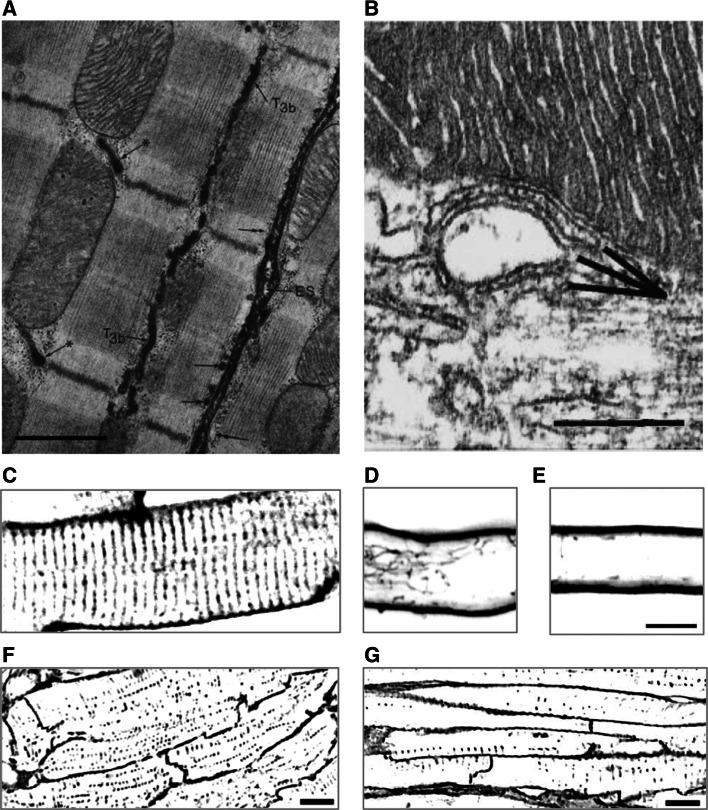

Fig. 2.

Cardiac tubule structure, junctions and network. a Electron micrograph of rat right ventricle, showing the extracellular space (ES), tubules running transversally (asterisk) and longitudinally (T3b). The arrows point at subsarcolemmal cisternae either labeled (double arrows) or unlabeled (single arrows) by the extracellular marker. Calibration bar 1.0 μm. Modified from [25]. b Electron micrograph of mouse left ventricle, showing an internal junction between SR and a T-tubule. Two SR elements (probably belonging to the same cisterna but separated in the image due to the sectioning plane) are apposed to a T-tubule. Calibration bar 0.25 μm. Modified from [109]. c–e Confocal images of rat myocytes, stained with di-8-ANEPPS and showing the dense tubular network in ventricular cells (c) and the low density or almost absence of tubules in atrial cells (d). In (d), a large longitudinal component can be noticed. Calibration bar 10 μm. Modified from [30]. f–g Confocal images of sheep myocytes, stained with FITC-conjugated wheat germ agglutinin and showing the presence of a developed tubular network (albeit with lower density than in rat) in the ventricle (f) and a less developed network in the atrium (g). Modified from [27]. The fluorescence images are shown inverted with contrast and threshold modified from the original version to make the tubular system uniform and comparable among different panels

Beyond the first EM observations, the investigation of the topology of the whole 3D tubular network in living myocytes has become accessible with the use of confocal or TPF microscopy, in combination with fluorescent membrane dyes (for example, 6-ANNEPS; see Fig. 1a). This method has allowed the systematic investigation of the TATS in different compartments of the heart and in different species, revealing, once again, a high degree of variability [26–32]. Figure 2c–g shows the variable density of tubules in ventricular myocytes across different species and the scarcity (or absence altogether) of tubules in atrial cells. The figure shows examples limited to two mammalian species, since all other phyla (amphibians, reptiles and birds) seem to lack tubules in both atrium and ventricle. Within mammals, the topology and ultrastructure of the tubular system have been extensively sampled and characterized, leading to a clear picture of TATS structure in small mammals (especially rodents). Larger mammals, on the other hand, present more anecdotic literature pointing anyway to a large spectrum of T-system structures and density in both ventricle and atrium, ranging from rare or absent tubules (for example, sheep atrium; see Fig. 2g, and pig ventricle [33]) to fairly dense and complex systems (most notably ventricles of dog [34] and sheep; see Fig. 2f), but never reaching the densities and structural complexity typical of rodent TATS.

Ventricular T-system density appears, by and large, correlated with the heart rate of each species. Functionally, it is reasonable to assume that those species with a higher heart rate require faster propagation of the cardiac AP from the sarcolemma into the cell interior, thus experiencing an evolutionary pressure for a higher T-tubules density. Indeed, the dynamics of Ca2+ propagation inside the myocyte depending on SS-tubular continuity (Fig. 1b) provide a clear demonstration of the effects of tubular density on the synchronicity and efficacy of myofilament contraction across the myocyte.

Image analysis on ventricular rat myocytes allowed the quantification of tubular size, as well as the relative cell volume occupied by tubules and of the relative abundance of tubules at the Z-lines and elsewhere [35]. The former was estimated at 3.6 %, somewhat higher than previous estimates derived from EM images; the latter ratio was estimated at around 60 % at the Z-line and 40 % elsewhere along the sarcomere. Cardiac tubule diameter could also be estimated at 100–300 nm, significantly larger than skeletal tubules (20–40 nm). The three-dimensional reconstruction obtained with two-photon microscopy also allowed mapping of the topography of tubular invagination from the SS, indicating large areas of SS characterized by a regular rectangular pattern of T-tubules mouths at about 1.8 μm distance from each other. This distribution of T-tubules mouths was first observed using the freeze-etch technique [36] and recently confirmed by scanning ion conductance microscopy [33].

Axial components have been described in both skeletal and cardiac muscle [24, 37]. Although in skeletal muscle axial tubules represent only 3 % of the T-system, in cardiac ventricles they have been estimated around 10–20 %, bridging between up to 4–5 consecutive Z-lines.

The principal function of tubules in cardiac ECC takes place at the junctions between the tubules themselves and the SR. Such junctions (dyads or couplons) are characterized by the apposition of the two membranes (with a typical distance of 12 nm), which brings in close proximity the sarcolemmal LTCCs with the SR RyRs (Fig. 2b). Immunostaining for RyRs [38] has shown that they are located primarily on the junctional SR, at the level of T-tubules and on the cell surface near the Z-lines, but some RyRs are on junctional SR adjacent to longitudinal tubules. Thus, the landscape of tubule-SR junctions mirrors the complexity of the topology of the TATS in cardiac myocytes, presenting contacts in three regions: in couplons on the surface, on T-tubules (both of which are near the Z-line), and in junctions on most of the longitudinal tubules–axial junctions. The axial junctions average 510 nm in length, sometimes spanning an entire sarcomere; in some studies, they were found to contain as much as 19 % of a cell’s RyRs [39]. In the same study, tomographic analysis confirmed the architecture of axial junctions as being indistinguishable from those on T-tubules or on the surface. Also, a complex tubule structure was observed, with a lumen of only 26 nm at its narrowest point. RyRs on axial junctions colocalize with CaV1.2, suggesting that it plays a role in ECC. In conclusion, longitudinal elements, although difficult to image properly, have been recently proved as an essential component of TATS, whose exact function still needs to be elucidated.

The complex structure–function relationship of cardiac T-tubules is highlighted by the dependence of the presence of tubules themselves on the cardiac performance: absent in the embryo, tubules develop at birth with the rising of left ventricular pressure and working volumes. The TATS formation occurs in parallel with the formation of other membrane structures, particularly the caveolae and the SR. The relationship between caveolae and T-tubules is similar to that seen in skeletal muscle [40, 41]. The relationship is strongly confirmed by the presence of caveolin-3, a specific marker of caveolae in T-tubules of developing skeletal and cardiac muscle [42] as well as in adult heart [43]. Typically, the initial development of T-tubules occurs at the cell edge in parallel to caveolae proliferation and to the caveolar multiple complexes formation to which T-tubules are clearly connected [44]. This suggests that caveolae formation is a necessary step in the invagination process of T-tubules, and that caveolin plays an essential role in this process by allowing curving of the membrane [42].

The formation of the TATS appears to derive from the generation of repetitive caveolae, which form “beaded tubules”. The penetration of T tubules into the cell has been envisaged as originating at the cell periphery and extending towards the center [40, 45–49], with a progressive increase in the number of connections between SR and growing T-tubules. Accordingly, DHPR foci, initially present only at the cell periphery, then also appear in the cell interior, where they co-localize with RyR clusters [45]. This would indicate that, during the T-tubule formation, the two proteins migrate independently through the SR and T-tubules and become associated when the two sets of membranes get close to each other and form the calcium release unit. However, observations in skeletal and in cardiac muscle suggest the possibility that distinct vesicles (expressing RyR or DHPR at their surface) associate in the cell interior due to RyR–DHPR interaction. Subsequently, each vesicle would be targeted to developing T-tubules or SR and fuse, contributing to their development. A combination of the two mechanisms is probably the most feasible [50].

The network organization reached at the end of tubular development is not static but rather responds to the cardiac functionality, with loss of tubules in pathological conditions and myocyte culture being the most evident examples. A number of proteins have been identified in the processes responsible for the formation and maintenance of the tubular network and of the tubule–SR molecular contacts.

Recent investigations found loss and disorganization of T-system in a number of pathological conditions including human chronic heart failure (HF) [33, 51], dilated and hypertrophic cardiomyopathies [33], and in animal models of chronic HF [52], chronic ischemia [26], atrial fibrillation [53], and mechanical unloading [54]. Additionally, the tubular network is gradually lost when myocytes are kept in culture, indicating a highly dynamic equilibrium involved in the maintenance of the intact network. To date, one of the most effective methods employed for the study of the role of the tubular network, as well as the consequences of its disruption, is the detubulation by osmotic shock [15, 55]. As described before, in this method, the osmotic volume changes induced by sequential addition and removal of formamide cause the physical detachment of the T-tubules from the SS. The effectiveness of the method is clearly demonstrated by staining myocytes before and after detubulation (Fig. 3); in the latter case, the loss of continuity between SS and tubular membrane, due to detubulation, prevents diffusion of the fluorescent dye in most of the tubular elements. Staining the tubules before detubulation, on the other hand, ensures uniform labeling of the tubular network, thus allowing AP measurements into the network after detubulation [23]. Figure 3a–c demonstrate that the loss of continuity between SS and the TTs abolishes the propagation of APs from the SS into the TATS. To investigate the behavior of the tubules that remain connected to the SS after detubulation, we stained cells after the osmotic shock so that only tubules still continuous with the surface were labeled. Figure 3e–f highlights a large variability in the responsiveness of different tubular elements to the propagation of AP. Even though the tubules are connected to the surface, AP propagation can fail. This indicates that connection of a single tubular element with the SS is not sufficient to ensure its electrical coupling to the surface.

Fig. 3.

TATS integrity and AP propagation. a Two-photon fluorescence (TPF) image of a myocyte with TATS stained before detubulation (S/D) by formamide-induced osmotic shock. Scale bar 5 μm. b Normalized fluorescence traces from the scanned lines indicated in (a): no electrical activity is detected in the scanned TATS regions (green and blue traces). Arrowheads point at the time of electrical stimulation. c Average of the ten sequential episodes shown in (b). d TPF image from a myocyte stained after detubulation (D/S): only a subpopulation of TTs is well labeled. Scale bar 5 μm. g Normalized fluorescence traces from the scanned lines indicated in (d): SS and TT 1 show regular APs, whereas TT 2 and TT 3 display non-regenerative electrical responses. Red asterisks in TT 3 highlight AP failures. f Average of ten episodes for SS, TT 1, and TT 2. Separate averaging of six APs and four subthreshold events in TT 3. Modified from [23]. The fluorescence images are shown inverted with contrast and threshold modified from the original version to make the T-system uniform and comparable among different panels

Structural and functional alterations of the TATS in cardiac diseases

Pathological alterations of the T-system were first identified in a limited number of EM studies performed on human ventricular tissue from patients with cardiac hypertrophy or HF [56–59]. Employing confocal microscopy and fluorescent membrane labeling, patchy T-tubular loss and disorganization have been described in a number of animal models of cardiac diseases, as illustrated in Fig. 4. Most of these results have been obtained from ventricular myocytes of HF models developed on small animals with high heart rates (such as mouse or rat) showing a rich and well-organized TATS before the pathological insults. In larger species with lower heart rates and a slower speed of contraction–relaxation, the requirement for such a highly developed T-tubular structure is not so clear. Although both pig and dog models of HF showed significant reduction in T-tubule density [52, 60], the most striking feature in these large animals was the wide number of areas devoid of T-tubules even in the normal hearts [61].

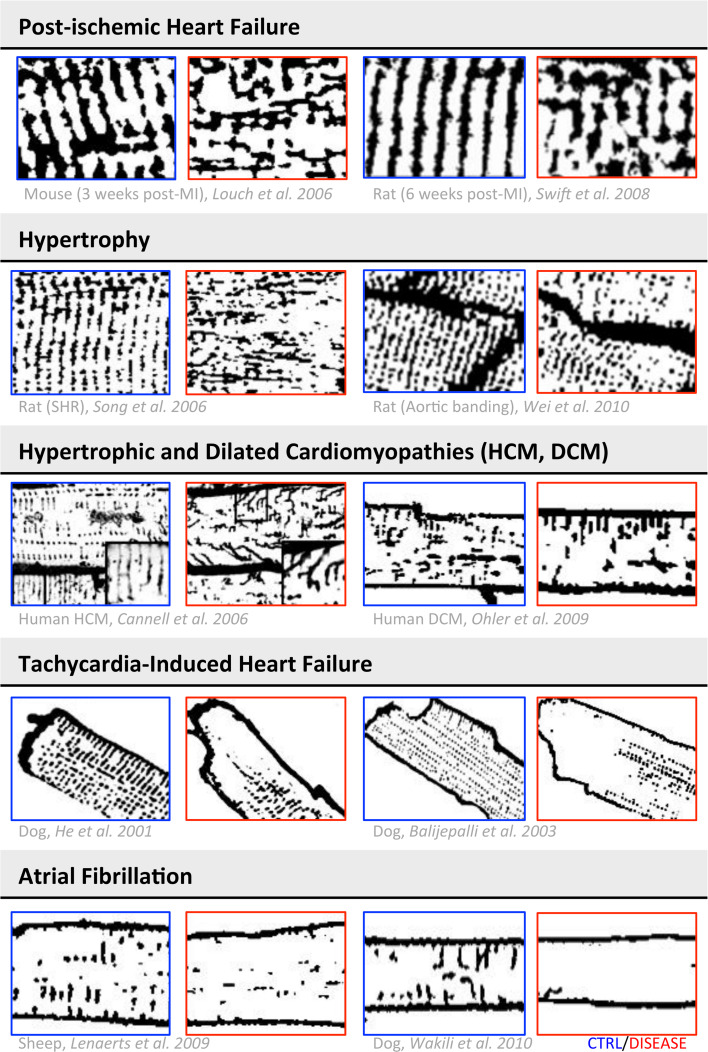

Fig. 4.

TATS remodeling in cardiac diseases. The table shows a collection of representative images obtained with membrane labeling and confocal microscopy from different animal and human models of cardiac disease. For each reference, representative images of diseased myocytes are in the red squares, while the respective controls are in the blue squares. Images modified from [34, 52, 53, 63, 64, 67, 68, 77, 110, 111]. The images are shown inverted with contrast and threshold modified from the original version to make the T-system uniform and comparable among different panels

In humans, early reports based on histological examinations in failing heart tissue sections showed T-tubular dilation with either increased [62] or decreased [58, 59] density of T-tubules, leaving the open question of whether low T-tubule density was failure-related or not. Recent studies in failing human hearts agree on the reduction of T-tubule density, which was two to three times lower in failing ventricular myocytes from HF patients with different aetiologies than in healthy donors [33, 63]. In a rat model of left ventricular pressure overload, the loss of T-tubules marks the transition from compensated hypertrophy to HF and thus detubulation appears likely as an “early event” in disease-related myocardial remodeling [64] (Fig. 5a). Consistently, in septal myocytes from myectomy samples of non-failing hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) patients with obstructive hypertrophy, we have recently observed that T-tubules are completely lost [65], indicating that T-tubule remodeling likely precedes the end-stage of the disease.

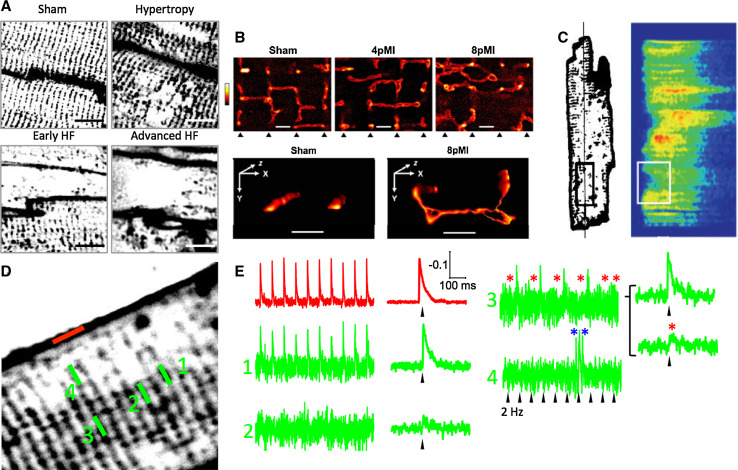

Fig. 5.

Abnormal TATS function in HF. a Representative T-tubule images (FM4–64 membrane staining) from the left ventricle of sham-operated, hypertrophic, early HF, and advanced HF rat hearts, showing the progression of TATS remodeling at different stages of the disease. Rats were subjected to pressure overload by thoracic aortic banding, leading first to left ventricular hypertrophy and then failure. Modified from [64]. b Live-cell STED images (di-8-ANEPPS membrane staining) showing TATS structures from sham, 4 weeks post-MI (4pMI), and 8 weeks post-MI (8pMI) cells (bottom triangles indicate position of striations); TATS appears enlarged, misaligned, and with increased longitudinal components in 4 weeks post-MI and, more pronouncedly, 8 weeks post-MI. Scale bar 1 μm. Modified from [69]. c Cell from a pig model of chronic ischemia, 6 weeks after inducing severe stenosis of the circumflex coronary artery. T-tubular (WGA-Alexa594) and corresponding line-scan Ca2+ (Fluo 3) images, showing that the regions of delayed Ca2+ release are related to areas of T-tubule rarefaction. Right horizontal scale bar 10 μm; vertical scale bar = 100 μm; left horizontal scale bar 50 ms. Modified from [26]. d Representative TPF image of a HF myocyte. e Normalized fluorescence traces from the scanned line indicated in (d): SS and TT 1 show that regular APs, TT 2, and TT 3 display non-regenerative electrical responses, and TT 4 highlights local arrhythmic events (blue asterisks). d, e Modified from [23]. The fluorescence TATS images in (a, c, and d) are shown inverted with contrast and threshold modified from the original version to make the T-system uniform and comparable among different panels

In addition to standard quantification of T-tubular loss with di-8-ANEPPS surface staining, detailed changes of cardiomyocyte surface topology were detected using a unique method (scanning ion conductance microscopy, SICM) to form topographic images of live myocytes [33, 66]. With this method, the loss of T-tubular openings in ventricular myocytes from failing human hearts was confirmed. In failing human cardiomyocytes, in addition to T-tubule loss, disruption of Z-groove structure has been observed [33].

Besides a reduction in the number of T-tubular openings and transverse components, disease-related T-system structural abnormalities include: (1) a greater proportion of tubules running in the longitudinal and oblique directions [67, 68], (2) increased mean T-tubular diameter and length [56, 59], and (3) tubular proliferation, with increased T-tubular tortuosity (i.e. number of constrictions and branches) [58]. These geometrical changes were recently characterized with nanometric resolution by using STED microscopy [69, 70] (Fig. 5b).

In HF, T-tubular remodeling goes hand-in-hand with spatial alterations of protein expression. Membrane fractionation studies were used to assess the redistribution of membrane-bound proteins among the different membrane sub-compartments in HF cells, showing reduction in LTCCs and β-adrenergic receptors, but increased levels of NCX protein, in both SS and residual T-tubular fractions [34].

In addition, SICM was used to assess the spatial localization of functional β2-ARs, which are concentrated in the TATS in normal cells. However, in heart failure, the spatial localization is lost, with a relative redistribution of β2-ARs to the cell surface [71]. The tight spatial localization of the β2-AR response depends on its co-localization with protein kinase A (PKA) and phosphodiesterases, which limit the spread of the cAMP response. The normally striated pattern of PKA, reflecting T-tubular periodicity, is lost in HF. This ‘globalization’ of the β2-AR response may partly mediate the loss of its cardioprotective effects and its role in driving the disease process in HF.

Asynchronous CICR and loss of Ca2+ release regulation

Since T-tubules are essential for fast coupling between the electrical activation of the membrane and the initiation of contraction, the consequences of a partial loss of T-tubules is expected to influence the amplitude and kinetics of Ca2+ fluxes and contraction parameters. The effects of T-tubule alterations on ECC were initially investigated by experimentally promoting T-tubule loss by either cell culture [60] or formamide-induced detubulation [72]. In both cases, T-tubule loss was associated with desynchronization of Ca2+ release across the cell. When cells were detubulated with formamide, wave-like propagation of the Ca2+ transient from the sarcolemma to the cell interior was observed [73], which resembled the pattern of Ca2+ release reported in cells with very low T-tubule density, such as atrial myocytes from rodents or Purkinje cells [74, 75]. With a less dramatic TATS reduction observed during cell culture, a fragmented Ca2+ release pattern was found [60]. This indicated that SR Ca2+ release was initially triggered at sites where T-tubules were present, followed by propagation into regions devoid of T-tubules. This situation is similar to that observed in normal myocytes characterized by a moderate T-tubular density, such as sheep atrial myocytes [28]. Spatially summating Ca2+ release in cells that had partially lost the T-system organization always resulted in an overall Ca2+ transient with slower kinetics and reduced magnitude.

Asynchronous Ca2+ release was first observed in myocytes from failing hearts by Litwin et al. [76]. Studies by Louch et al. [60] and Song et al. [77] highlighted a spatial link between such alterations of Ca2+ release and abnormalities of T-tubular structure. In both studies, by simultaneously visualizing the T-tubule network and intracellular [Ca2+] (Fig. 5c), small regions with delayed Ca2+ release were observed following T-tubule disorganization, occurring at irregular gaps among adjacent T-tubules. Song et al. [77, 78] observed, however, that the RyR distribution remained intact in failing myocytes, suggesting that T-tubule disorganization resulted in some orphaned RyRs, i.e. RyRs cluster that became physically separated from their DHPR partners. These orphaned RyRs might respond differently to local Ca2+ changes, with loss of normal local control. Importantly, a number of investigations [33, 51] have shown that reduced Ca2+ release synchrony in failing cells (as in case of experimental T-tubule loss [73]) promotes slowing and broadening of the overall Ca2+ transient, a hallmark of the failing condition [79]. In HF, prolongation of the AP and loss of an early repolarization notch in failing cells reduce the driving force for Ca2+ entry, resulting in decreased peak Ca2+ current [80]. In addition, the time course of Ca2+ entry is prolonged during the failing AP, which reduces efficiency for triggering Ca2+ release from the SR [81].

Whether and how alterations in RyR function in HF are related to T-tubular changes is still unclear. In cardiomyocytes that underwent acute formamide-induced detubulation, the frequency of spontaneous Ca2+ sparks was not increased, indicating that functional uncoupling of T-tubules from the surface does not affect RyR open probability [73]. Conversely, Meethal et al. [82] recently reported that, in failing cells, spontaneous Ca2+ sparks occur more frequently at the irregular gaps between T-tubules created by T-tubule loss. Resting Ca2+ levels were also higher at these locations. These last observations suggest that orphaned RyR could exhibit greater activity than those in intact dyads, and that this over-activity may contribute importantly to increased SR leak and arrhythmic potential in failing cells. If groups of orphaned RyRs are also functionally uncoupled and therefore unregulated, such alterations might theoretically exacerbate Ca2+ release asynchrony by slowing propagation of CICR into regions where T-tubules are absent. Similarly, SR leak and reduced SR content might also influence synchrony by affecting the speed of Ca2+ propagation into detubulated cell regions [73]. Moreover, in failing myocytes, the observed expansion of the dyadic cleft, resulting in a greater distance between Ca2+ channels and RyR [83], would contribute to the lower Ca2+ release amplitude and synchrony, further reducing ECC efficiency.

AP propagation in remodeled TATS: implications for arrhythmias

Ventricular cardiomyocytes in HF are characterized by loss and disorganization of the TATS [33], determining orphaned RyR clusters, which remain non-recruited or are activated with a significant delay [83]. We have previously observed that, within the diseased myocyte, many TATS elements fail to conduct AP despite being physically connected to the SS [23] (Fig. 5d, e). In dysfunctional TATS elements, no active responses are observed upon cell stimulation. TATS elements that do not conduct AP cannot activate Ca2+ current and Ca2+ release. Therefore, the presence of dysfunctional tubules represent an additional mechanism contributing to the reduced RyR recruitment and lower ECC efficiency in HF. Morphological analysis of TATS density may then overestimate the number of recruitable Ca2+ release units in HF.

How electrical conduction may fail in physically coupled TATS elements remains to be investigated. Mathematical modeling, as described above, may help clarify this issue. Local electrical uncoupling even in the presence of the membrane continuity may arise from the increased electrical resistance between the TATS element and the surrounding sarcolemma. The morphological correlate of this increased resistance in HF-related tubular remodeling, as in myocytes from rats with post-myocardial infarction systolic dysfunction, may rely on the changes of T-tubular architecture discussed above, in particular the increased average length and tortuosity of T-tubules. Interestingly, the model predicts that, when the number of T-tubules is reduced, slight variations of T-tubular length can cause failure of AP conduction.

Moreover, we have shown that, in cells from infarcted rats, T-tubules that do not display normal APs in response to stimuli sometimes show spontaneous electrical activity. We can speculate that these spontaneous depolarizations may be related to spontaneous Ca2+ releases from the SR. Local Ca2+ releases may give rise to activation of inward NCX current within the T-tubules. If the resistance R st (see Eq. 1) is very high, T-tubules are electrically disconnected from SS. The capacitance of electrically-uncoupled TATS elements is smaller than SS capacitance; therefore, even small Ca2+ releases from the SR can potentially generate large local NCX-driven inward currents and give rise to important variations of membrane voltage. Similar currents would be too small to affect global membrane potential. The high R st would keep these responses “local” and prevent their spread; however, their arrhythmogenic potential may be relevant. In fact, local spontaneous depolarizations may be capable of amplifying Ca2+ sparks via activation of the nearby RyR clusters, thereby turning local spontaneous Ca2+ release into generalized Ca2+ waves [84] spreading throughout the whole myocyte. In our view, two complementary mechanisms may cooperate in determining HF-related arrhythmogenicity: unregulated RyRs, increasing the rate of Ca2+ sparks, and uncoupled TATS elements, generating a positive feedback that turns local sparks into generalized Ca2+ waves, which are triggers for delayed after depolarizations (DADs) and arrhythmias. Besides the reduced TATS density, the presence of tubules with untimely electrical responses, by triggering local asynchronous Ca2+ release, may also contribute to non-uniform myofilament activation [84] and SR Ca2+ content depletion [83], promoting contractile dysfunction in HF. Besides spatial inhomogeneities, asynchronous activation of unregulated RyR may desynchronize their refractoriness leading to Ca2+ alternans, beat-to-beat variability, and, thus, arrhythmogenicity. This hypothesis, although rather speculative, deserves further investigation.

Reverse T-tubular remodeling and molecular determinants of TATS assembly/disorganization

Is the pathological loss of T-tubules a one-way course of events or can the T-system structure be recovered? What happens when the primary source of damage to the diseased myocardium is resolved? And what happens to the T-system when sinus rhythm is recovered after successful cardioversion of atrial fibrillation or when HF is efficaciously treated?

Reversal of pathological myocardial remodeling (reverse remodeling) has been extensively studied in a number of human models of HF. Mechanical unloading of the failing heart, obtained either by heterotopic heart transplantation or by virtue of left-ventricular assist devices (LVAD) [85], seems to reverse some of the HF-related changes in diseased cardiomyocytes. In patients with terminal HF, LVAD treatment leads to reduction in cell hypertrophy [86], shorter AP duration, increased LTCC current with faster inactivation [87], higher SR Ca2+ content related to increased SERCA protein [88], and augmented amplitude of Ca2+ release, ultimately determining improved contractility of cardiac muscle [89]. Similarly, in a rat model of ischemic HF, heterotopic transplantation led to beneficial effects on cell size, Ca2+ transient amplitude and kinetics, and developed force [90]. Interestingly, in that model, unloading counteracted the HF-related loss and disorganization of T-tubules: the density of T-tubules, the number of Z-grooves and T-tubule openings on the surface, and T-tubular dimensions were restored by unloading [91] (Fig. 6b). As a consequence of T-tubular recovery, the synchrony of CICR was also normalized. Although the effects of mechanical unloading on T-tubules remain to be studied on human failing cardiomyocytes, the reported beneficial effects on Ca2+ release kinetics [87] suggest that a partial recovery of T-system structure also occurs in human tissue. Furthermore, in a canine model of HF T-system restoration has been observed after 3 weeks of cardiac resynchronization therapy [92] (simultaneous pacing of the right and the left ventricles), largely used in HF patients [93].

Fig. 6.

Molecular complexes implicated in TATS turn-over and reverse remodeling. a Junctophilin-2 (JPH2) knockdown causes disorganization and loss of TATS: confocal images of di-8-ANEPPS stained cardiomyocytes. Modified from [101]. b HF myocytes show lower TATS density and T-tubular dilation, which are partially reversed by mechanical unloading (HF-unloading). Modified from [91]. c Retubulation of failing cardiomyocytes after rescue by AAV9SERCA2a gene therapy. Confocal images of di-8-ANNEPPS stained healthy, failing (HF) and failing AAV9SERCA2a-treated (HF + S) hearts. Modified from [97]. d Exercise training in HF (MI-TR) increases TATS density, compared to sedentary heart failure (MI-SED): confocal images of di-8-ANEPPS stained cardiomyocytes. Modified from [100]. The fluorescence images are shown inverted with contrast and threshold modified from the original version to make the T-system uniform and comparable among different panels

Overexpression of SERCA protein induced by targeted viral gene transfer of SERCA2a gene has been widely studied as a valuable therapy for HF [94]. Owing to the faster Ca2+ transient decay, the reduced diastolic Ca2+, and the higher SR Ca2+ content, SERCA overexpression leads to improved myocardial contraction [89]; in rat models of chronic pressure overload [95] and ischemic HF [96], SERCA2a gene transfer determined ameliorated cardiac function and reduced frequency of arrhythmias. Interestingly, in the rat HF model, functional improvement due to SERCA2a transfection was accompanied by a reversal of T-tubular remodeling [97]; the density of TATS was restored and the spatial heterogeneity of Ca2+ transient was reduced, resulting in larger amplitude and faster kinetics of Ca2+ release (Fig. 6c).

Pharmacological approaches have also been employed in disease model to reduce myocardial remodeling and TATS disorganization. In a rat model of pulmonary hypertension, treatment with phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor sildenafil reduced the hypertrophic remodeling of right ventricular cardiomyocytes and reversed the impairment of T-tubule integrity [98]. In a HF rat model, reduction of heart rate with ivabradine reduced T-tubular changes in combination with unloading [99]. In a rat model of HF, exercise training promotes TATS regeneration [100] (Fig. 6d).

In conclusion, T-tubular remodeling in cardiac diseases is a highly plastic phenomenon, which reverts upon effective treatments of the underlying cause of disease.

Despite the fact that loss of T-tubules occurs in most cardiac diseases, the molecular pathways determining TATS disorganization are still largely unknown. A recent advancement has been made by two seminal works highlighting the role of junctophilin [101] and telethonin [102] in the correct assembly of TATS-SR-Z disc connections. Junctophilin (JPH2) expression is reduced in human and animal models of hypertrophy and failure [103, 104] and inherited mutations of JPH2 and telethonin gene (Tcap) have been identified as responsible for hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathies [105, 106]. Of note, all these conditions involve loss of T-tubules. Interestingly, specific cardiac knockout of JPH2 or Tcap genes in transgenic mouse models leads to severe reduction of TATS density, orphaned and unregulated RyRs, and abnormal ECC leading to global cardiac dysfunction [101, 102] (Fig 6a).

Junctophilin-2 undergoes Ca2+-dependent proteolysis, and junctophilin-2 levels are reduced following cardiac ischaemia–reperfusion [107]. Junctophilin proteolysis, destabilizing the close apposition of the T-system and SR membranes, may disrupt communication between the dihydropyridine and RyR and thus contribute to cardiac dysfunction.

These observations suggest that JPH2 and Tcap play an important role in determining a correct T-tubular structure, and changes in the expression of these proteins might be a determinant of T-system remodeling in disease settings.

Acknowledgments

The research leading to these results received funding from the European Union Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007– 2013) under Grant Agreements 241577, 241526, 228334 and 284464. This work has been also supported by the Italian Ministry for Education, University and Research in the framework of the Flagship Project NANOMAX and by Telethon-Italy (GGP13162). This work has been carried out in the framework of the research activities of ICON foundation supported by “Ente Cassa di Risparmio di Firenze”. We thank Professor Giovanni Delfino for useful discussions.

References

- 1.Lindner E. Submicroscopic morphology of the cardiac muscle. Z Zellforsch Mikrosk Anat. 1957;45(6):702–746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tidball JG, Cederdahl JE, Bers DM. Quantitative analysis of regional variability in the distribution of transverse tubules in rabbit myocardium. Cell Tissue Res. 1991;264(2):293–298. doi: 10.1007/BF00313966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Franzini-Armstrong C, Venosa RA, Horowicz P. Morphology and accessibility of the ‘transverse’ tubular system in frog sartorius muscle after glycerol treatment. J Membr Biol. 1973;14(3):197–212. doi: 10.1007/BF01868078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bers DM. Cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. Nature. 2002;415(6868):198–205. doi: 10.1038/415198a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kushnir A, Marks AR. The ryanodine receptor in cardiac physiology and disease. Adv Pharmacol. 2010;59:1–30. doi: 10.1016/S1054-3589(10)59001-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pasek M, Brette F, Nelson A, Pearce C, Qaiser A, Christe G, Orchard CH. Quantification of t-tubule area and protein distribution in rat cardiac ventricular myocytes. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2008;96(1–3):244–257. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2007.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brette F, Orchard C. T-tubule function in mammalian cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 2003;92(11):1182–1192. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000074908.17214.FD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scriven DR, Dan P, Moore ED. Distribution of proteins implicated in excitation-contraction coupling in rat ventricular myocytes. Biophys J. 2000;79(5):2682–2691. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76506-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas MJ, Sjaastad I, Andersen K, Helm PJ, Wasserstrom JA, Sejersted OM, Ottersen OP. Localization and function of the Na+/Ca2+-exchanger in normal and detubulated rat cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2003;35(11):1325–1337. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2003.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shepherd N, McDonough HB. Ionic diffusion in transverse tubules of cardiac ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol. 1998;275(3 Pt 2):H852–H860. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.3.H852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang Z, Pascarel C, Steele DS, Komukai K, Brette F, Orchard CH. Na+-Ca2+ exchange activity is localized in the T-tubules of rat ventricular myocytes. Circ Res. 2002;91(4):315–322. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000030180.06028.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brette F, Salle L, Orchard CH. Differential modulation of L-type Ca2+ current by SR Ca2+ release at the T-tubules and surface membrane of rat ventricular myocytes. Circ Res. 2004;95(1):e1–e7. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000135547.53927.F6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yao A, Spitzer KW, Ito N, Zaniboni M, Lorell BH, Barry WH. The restriction of diffusion of cations at the external surface of cardiac myocytes varies between species. Cell Calcium. 1997;22(6):431–438. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(97)90070-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blatter LA, Niggli E. Confocal near-membrane detection of calcium in cardiac myocytes. Cell Calcium. 1998;23(5):269–279. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(98)90023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brette F, Komukai K, Orchard CH. Validation of formamide as a detubulation agent in isolated rat cardiac cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283(4):H1720–H1728. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00347.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pasek M, Simurda J, Orchard CH, Christe G. A model of the guinea-pig ventricular cardiac myocyte incorporating a transverse-axial tubular system. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2008;96(1–3):258–280. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2007.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pasek M, Christe G, Simurda J. A quantitative model of the cardiac ventricular cell incorporating the transverse-axial tubular system. Gen Physiol Biophys. 2003;22(3):355–368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Orchard CH, Pasek M, Brette F. The role of mammalian cardiac t-tubules in excitation-contraction coupling: experimental and computational approaches. Exp Physiol. 2009;94(5):509–519. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2008.043984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bu G, Adams H, Berbari EJ, Rubart M. Uniform action potential repolarization within the sarcolemma of in situ ventricular cardiomyocytes. Biophys J. 2009;96(6):2532–2546. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.12.3896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iyer V, Hoogland TM, Saggau P. Fast functional imaging of single neurons using random-access multiphoton (RAMP) microscopy. J Neurophysiol. 2006;95(1):535–545. doi: 10.1152/jn.00865.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sacconi L, Mapelli J, Gandolfi D, Lotti J, O’Connor RP, D’Angelo E, Pavone FS. Optical recording of electrical activity in intact neuronal networks with random access second-harmonic generation microscopy. Opt Express. 2008;16(19):14910–14921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yan P, Acker CD, Zhou WL, Lee P, Bollensdorff C, Negrean A, Lotti J, Sacconi L, Antic SD, Kohl P, Mansvelder HD, Pavone FS, Loew LM. Palette of fluorinated voltage-sensitive hemicyanine dyes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(50):20443–20448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1214850109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sacconi L, Ferrantini C, Lotti J, Coppini R, Yan P, Loew LM, Tesi C, Cerbai E, Poggesi C, Pavone FS. Action potential propagation in transverse-axial tubular system is impaired in heart failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(15):5815–5819. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120188109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Franzini-Armstrong C. Veratti and beyond: structural contributions to the study of muscle activation. Rendiconti Lincei. 2002;13(4):289–323. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Forssmann WG, Girardier L. A study of the T system in rat heart. J Cell Biol. 1970;44(1):1–19. doi: 10.1083/jcb.44.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heinzel FR, Bito V, Biesmans L, Wu M, Detre E, von Wegner F, Claus P, Dymarkowski S, Maes F, Bogaert J, Rademakers F, D’Hooge J, Sipido K. Remodeling of T-tubules and reduced synchrony of Ca2+ release in myocytes from chronically ischemic myocardium. Circ Res. 2008;102(3):338–346. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.160085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Richards MA, Clarke JD, Saravanan P, Voigt N, Dobrev D, Eisner DA, Trafford AW, Dibb KM. Transverse tubules are a common feature in large mammalian atrial myocytes including human. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301(5):H1996–H2005. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00284.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dibb KM, Clarke JD, Horn MA, Richards MA, Graham HK, Eisner DA, Trafford AW. Characterization of an extensive transverse tubular network in sheep atrial myocytes and its depletion in heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2009;2(5):482–489. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.852228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smyrnias I, Mair W, Harzheim D, Walker SA, Roderick HL, Bootman MD. Comparison of the T-tubule system in adult rat ventricular and atrial myocytes, and its role in excitation-contraction coupling and inotropic stimulation. Cell Calcium. 2010;47(3):210–223. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kirk MM, Izu LT, Chen-Izu Y, McCulle SL, Wier WG, Balke CW, Shorofsky SR. Role of the transverse-axial tubule system in generating calcium sparks and calcium transients in rat atrial myocytes. J Physiol. 2003;547(Pt 2):441–451. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.034355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Savio-Galimberti E, Frank J, Inoue M, Goldhaber JI, Cannell MB, Bridge JH, Sachse FB. Novel features of the rabbit transverse tubular system revealed by quantitative analysis of three-dimensional reconstructions from confocal images. Biophys J. 2008;95(4):2053–2062. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.130617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jayasinghe I, Crossman D, Soeller C, Cannell M. Comparison of the organization of T-tubules, sarcoplasmic reticulum and ryanodine receptors in rat and human ventricular myocardium. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2012;39(5):469–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2011.05578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lyon AR, MacLeod KT, Zhang Y, Garcia E, Kanda GK, Lab MJ, Korchev YE, Harding SE, Gorelik J. Loss of T-tubules and other changes to surface topography in ventricular myocytes from failing human and rat heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(16):6854–6859. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809777106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Balijepalli RC, Lokuta AJ, Maertz NA, Buck JM, Haworth RA, Valdivia HH, Kamp TJ. Depletion of T-tubules and specific subcellular changes in sarcolemmal proteins in tachycardia-induced heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;59(1):67–77. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(03)00325-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Soeller C, Cannell MB. Examination of the transverse tubular system in living cardiac rat myocytes by 2-photon microscopy and digital image-processing techniques. Circ Res. 1999;84(3):266–275. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.3.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rayns DG, Simpson FO, Bertaud WS. Surface features of striated muscle. I. Guinea-pig cardiac muscle. J Cell Sci. 1968;3(4):467–474. doi: 10.1242/jcs.3.4.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu Z, Holst MJ, Hayashi T, Bajaj CL, Ellisman MH, McCammon JA, Hoshijima M. Three-dimensional geometric modeling of membrane-bound organelles in ventricular myocytes: bridging the gap between microscopic imaging and mathematical simulation. J Struct Biol. 2008;164(3):304–313. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jayasinghe ID, Cannell MB, Soeller C. Organization of ryanodine receptors, transverse tubules, and sodium-calcium exchanger in rat myocytes. Biophys J. 2009;97(10):2664–2673. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.08.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Asghari P, Schulson M, Scriven DR, Martens G, Moore ED. Axial tubules of rat ventricular myocytes form multiple junctions with the sarcoplasmic reticulum. Biophys J. 2009;96(11):4651–4660. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.02.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Forbes MS, Hawkey LA, Sperelakis N. The transverse-axial tubular system (TATS) of mouse myocardium: its morphology in the developing and adult animal. Am J Anat. 1984;170(2):143–162. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001700203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leeson TS. The transverse tubular (T) system of rat cardiac muscle fibers as demonstrated by tannic acid mordanting. Can J Zool. 1978;56(9):1906–1916. doi: 10.1139/z78-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parton RG, Way M, Zorzi N, Stang E. Caveolin-3 associates with developing T-tubules during muscle differentiation. J Cell Biol. 1997;136(1):137–154. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.1.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Voldstedlund M, Vinten J, Tranum-Jensen J. cav-p60 expression in rat muscle tissues. Distribution of caveolar proteins. Cell Tissue Res. 2001;306(2):265–276. doi: 10.1007/s004410100439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ezerman EB, Ishikawa H. Differentiation of the sarcoplasmic reticulum and T system in developing chick skeletal muscle in vitro. J Cell Biol. 1967;35(2):405–420. doi: 10.1083/jcb.35.2.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sedarat F, Xu L, Moore ED, Tibbits GF. Colocalization of dihydropyridine and ryanodine receptors in neonate rabbit heart using confocal microscopy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;279(1):H202–H209. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.1.H202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ishikawa H. Formation of elaborate networks of T-system tubules in cultured skeletal muscle with special reference to the T-system formation. J Cell Biol. 1968;38(1):51–66. doi: 10.1083/jcb.38.1.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Flucher BE, Takekura H, Franzini-Armstrong C. Development of the excitation-contraction coupling apparatus in skeletal muscle: association of sarcoplasmic reticulum and transverse tubules with myofibrils. Dev Biol. 1993;160(1):135–147. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1993.1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takekura H, Yoshioka T. Differentiational profiles of skeletal muscle internal membrane systems directly related to excitation-contraction coupling. Nihon Seirigaku Zasshi J Physiol Soc Jpn. 1993;55(10):392–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Franzini-Armstrong C. Simultaneous maturation of transverse tubules and sarcoplasmic reticulum during muscle differentiation in the mouse. Dev Biol. 1991;146(2):353–363. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(91)90237-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Di Maio A, Karko K, Snopko RM, Mejia-Alvarez R, Franzini-Armstrong C. T-tubule formation in cardiacmyocytes: two possible mechanisms? J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2007;28(4–5):231–241. doi: 10.1007/s10974-007-9121-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Malaisse WJ, Zhang Y, Louchami K, Jijakli H. Stimulation by d-glucose of 36Cl- efflux from prelabeled rat pancreatic islets. Endocrine. 2004;25(1):23–25. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:25:1:23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.He J, Conklin MW, Foell JD, Wolff MR, Haworth RA, Coronado R, Kamp TJ. Reduction in density of transverse tubules and L-type Ca(2+) channels in canine tachycardia-induced heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 2001;49(2):298–307. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00256-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lenaerts I, Bito V, Heinzel FR, Driesen RB, Holemans P, D’Hooge J, Heidbuchel H, Sipido KR, Willems R. Ultrastructural and functional remodeling of the coupling between Ca2+ influx and sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release in right atrial myocytes from experimental persistent atrial fibrillation. Circ Res. 2009;105(9):876–885. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.206276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ibrahim M, Terracciano CM. Reversibility of t-tubule remodeling in heart failure: mechanical load as a dynamic regulator of the t-tubules. Cardiovasc Res. 2013 doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kawai M, Hussain M, Orchard CH. Excitation-contraction coupling in rat ventricular myocytes after formamide-induced detubulation. Am J Physiol. 1999;277(2 Pt 2):H603–H609. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.277.2.H603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Maron BJ, Ferrans VJ, Roberts WC. Ultrastructural features of degenerated cardiac muscle cells in patients with cardiac hypertrophy. Am J Pathol. 1975;79(3):387–434. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schaper J, Froede R, Hein S, Buck A, Hashizume H, Speiser B, Friedl A, Bleese N. Impairment of the myocardial ultrastructure and changes of the cytoskeleton in dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1991;83(2):504–514. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.83.2.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kostin S, Scholz D, Shimada T, Maeno Y, Mollnau H, Hein S, Schaper J. The internal and external protein scaffold of the T-tubular system in cardiomyocytes. Cell Tissue Res. 1998;294(3):449–460. doi: 10.1007/s004410051196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kaprielian RR, Stevenson S, Rothery SM, Cullen MJ, Severs NJ. Distinct patterns of dystrophin organization in myocyte sarcolemma and transverse tubules of normal and diseased human myocardium. Circulation. 2000;101(22):2586–2594. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.22.2586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Louch WE, Bito V, Heinzel FR, Macianskiene R, Vanhaecke J, Flameng W, Mubagwa K, Sipido KR. Reduced synchrony of Ca2+ release with loss of T-tubules-a comparison to Ca2+ release in human failing cardiomyocytes. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;62(1):63–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Heinzel FR, Bito V, Volders PG, Antoons G, Mubagwa K, Sipido KR. Spatial and temporal inhomogeneities during Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum in pig ventricular myocytes. Circ Res. 2002;91(11):1023–1030. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000045940.67060.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wong C, Soeller C, Burton L, Cannell M. Changes in transverse-tubular system architecture in myocytes from diseased human ventricles. Biophys J. 2001;80:588a. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cannell MB, Crossman DJ, Soeller C. Effect of changes in action potential spike configuration, junctional sarcoplasmic reticulum micro-architecture and altered t-tubule structure in human heart failure. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2006;27(5–7):297–306. doi: 10.1007/s10974-006-9089-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wei S, Guo A, Chen B, Kutschke W, Xie YP, Zimmerman K, Weiss RM, Anderson ME, Cheng H, Song LS. T-tubule remodeling during transition from hypertrophy to heart failure. Circ Res. 2010;107(4):520–531. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.212324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Coppini R, Ferrantini C, Yao L, Fan P, Del Lungo M, Stillitano F, Sartiani L, Tosi B, Suffredini S, Tesi C, Yacoub M, Olivotto I, Belardinelli L, Poggesi C, Cerbai E, Mugelli A. Late sodium current inhibition reverses electromechanical dysfunction in human hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2013;127(5):575–584. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.134932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Miragoli M, Moshkov A, Novak P, Shevchuk A, Nikolaev VO, El-Hamamsy I, Potter CM, Wright P, Kadir SH, Lyon AR, Mitchell JA, Chester AH, Klenerman D, Lab MJ, Korchev YE, Harding SE, Gorelik J. Scanning ion conductance microscopy: a convergent high-resolution technology for multi-parametric analysis of living cardiovascular cells. J R Soc Interface. 2011;8(60):913–925. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2010.0597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Swift F, Birkeland JA, Tovsrud N, Enger UH, Aronsen JM, Louch WE, Sjaastad I, Sejersted OM. Altered Na+/Ca2+-exchanger activity due to downregulation of Na+/K+-ATPase alpha2-isoform in heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;78(1):71–78. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Louch WE, Mork HK, Sexton J, Stromme TA, Laake P, Sjaastad I, Sejersted OM. T-tubule disorganization and reduced synchrony of Ca2+ release in murine cardiomyocytes following myocardial infarction. J Physiol. 2006;574(Pt 2):519–533. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.107227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wagner E, Lauterbach MA, Kohl T, Westphal V, Williams GS, Steinbrecher JH, Streich JH, Korff B, Tuan HT, Hagen B, Luther S, Hasenfuss G, Parlitz U, Jafri MS, Hell SW, Lederer WJ, Lehnart SE. Stimulated emission depletion live-cell super-resolution imaging shows proliferative remodeling of T-tubule membrane structures after myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2012;111(4):402–414. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.274530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kohl T, Westphal V, Hell SW, Lehnart SE. Superresolution microscopy in heart—cardiac nanoscopy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2013;58:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gorelik J, Wright PT, Lyon AR, Harding SE. Spatial control of the betaAR system in heart failure: the transverse tubule and beyond. Cardiovasc Res. 2013 doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Brette F, Rodriguez P, Komukai K, Colyer J, Orchard CH. Beta-adrenergic stimulation restores the Ca transient of ventricular myocytes lacking t-tubules. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2004;36(2):265–275. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Brette F, Despa S, Bers DM, Orchard CH. Spatiotemporal characteriztics of SR Ca(2+) uptake and release in detubulated rat ventricular myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005;39(5):804–812. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cordeiro JM, Spitzer KW, Giles WR, Ershler PE, Cannell MB, Bridge JH. Location of the initiation site of calcium transients and sparks in rabbit heart Purkinje cells. J Physiol. 2001;531(Pt 2):301–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0301i.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mackenzie L, Roderick HL, Berridge MJ, Conway SJ, Bootman MD. The spatial pattern of atrial cardiomyocyte calcium signalling modulates contraction. J Cell Sci. 2004;117(Pt 26):6327–6337. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Litwin SE, Zhang D, Bridge JH. Dyssynchronous Ca(2+) sparks in myocytes from infarcted hearts. Circ Res. 2000;87(11):1040–1047. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.11.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Song LS, Sobie EA, McCulle S, Lederer WJ, Balke CW, Cheng H. Orphaned ryanodine receptors in the failing heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(11):4305–4310. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509324103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gomez AM, Guatimosim S, Dilly KW, Vassort G, Lederer WJ. Heart failure after myocardial infarction: altered excitation-contraction coupling. Circulation. 2001;104(6):688–693. doi: 10.1161/hc3201.092285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sipido KR, Stankovicova T, Flameng W, Vanhaecke J, Verdonck F. Frequency dependence of Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum in human ventricular myocytes from end-stage heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 1998;37(2):478–488. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(97)00280-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Harris DM, Mills GD, Chen X, Kubo H, Berretta RM, Votaw VS, Santana LF, Houser SR. Alterations in early action potential repolarization causes localized failure of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release. Circ Res. 2005;96(5):543–550. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000158966.58380.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sah R, Ramirez RJ, Oudit GY, Gidrewicz D, Trivieri MG, Zobel C, Backx PH. Regulation of cardiac excitation-contraction coupling by action potential repolarization: role of the transient outward potassium current [I(to)] J Physiol. 2003;546(Pt 1):5–18. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.026468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Meethal SV, Potter KT, Redon D, Munoz-del-Rio A, Kamp TJ, Valdivia HH, Haworth RA. Structure-function relationships of Ca spark activity in normal and failing cardiac myocytes as revealed by flash photography. Cell Calcium. 2007;41(2):123–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gomez AM, Valdivia HH, Cheng H, Lederer MR, Santana LF, Cannell MB, McCune SA, Altschuld RA, Lederer WJ. Defective excitation-contraction coupling in experimental cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. Science. 1997;276(5313):800–806. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5313.800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ter Keurs HE, Boyden PA. Calcium and arrhythmogenesis. Physiol Rev. 2007;87(2):457–506. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00011.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ambardekar AV, Buttrick PM. Reverse remodeling with left ventricular assist devices: a review of clinical, cellular, and molecular effects. Circ Heart Fail. 2011;4(2):224–233. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.110.959684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zafeiridis A, Jeevanandam V, Houser SR, Margulies KB. Regression of cellular hypertrophy after left ventricular assist device support. Circulation. 1998;98(7):656–662. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.7.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Terracciano CM, Hardy J, Birks EJ, Khaghani A, Banner NR, Yacoub MH. Clinical recovery from end-stage heart failure using left-ventricular assist device and pharmacological therapy correlates with increased sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium content but not with regression of cellular hypertrophy. Circulation. 2004;109(19):2263–2265. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000129233.51320.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Heerdt PM, Holmes JW, Cai B, Barbone A, Madigan JD, Reiken S, Lee DL, Oz MC, Marks AR, Burkhoff D. Chronic unloading by left ventricular assist device reverses contractile dysfunction and alters gene expression in end-stage heart failure. Circulation. 2000;102(22):2713–2719. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.22.2713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hajjar RJ, Kang JX, Gwathmey JK, Rosenzweig A. Physiological effects of adenoviral gene transfer of sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase in isolated rat myocytes. Circulation. 1997;95(2):423–429. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.2.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Soppa GK, Lee J, Stagg MA, Felkin LE, Barton PJ, Siedlecka U, Youssef S, Yacoub MH, Terracciano CM. Role and possible mechanisms of clenbuterol in enhancing reverse remodeling during mechanical unloading in murine heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;77(4):695–706. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvm106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ibrahim M, Navaratnarajah M, Siedlecka U, Rao C, Dias P, Moshkov AV, Gorelik J, Yacoub MH, Terracciano CM. Mechanical unloading reverses transverse tubule remodeling and normalizes local Ca(2+)-induced Ca(2+)release in a rodent model of heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2012;14(6):571–580. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sachse FB, Torres NS, Savio-Galimberti E, Aiba T, Kass DA, Tomaselli GF, Bridge JH. Subcellular structures and function of myocytes impaired during heart failure are restored by cardiac resynchronization therapy. Circ Res. 2012;110(4):588–597. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.257428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Cleland JG, Daubert JC, Erdmann E, Freemantle N, Gras D, Kappenberger L, Tavazzi L, Cardiac Resynchronization-Heart Failure Study I The effect of cardiac resynchronization on morbidity and mortality in heart failure. N Eng J Med. 2005;352(15):1539–1549. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kho C, Lee A, Hajjar RJ. Altered sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium cycling-targets for heart failure therapy. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2012;9(12):717–733. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2012.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Miyamoto MI, del Monte F, Schmidt U, DiSalvo TS, Kang ZB, Matsui T, Guerrero JL, Gwathmey JK, Rosenzweig A, Hajjar RJ. Adenoviral gene transfer of SERCA2a improves left-ventricular function in aortic-banded rats in transition to heart failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(2):793–798. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lyon AR, Bannister ML, Collins T, Pearce E, Sepehripour AH, Dubb SS, Garcia E, O’Gara P, Liang L, Kohlbrenner E, Hajjar RJ, Peters NS, Poole-Wilson PA, Macleod KT, Harding SE. SERCA2a gene transfer decreases sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium leak and reduces ventricular arrhythmias in a model of chronic heart failure. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2011;4(3):362–372. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.110.961615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lyon AR, Nikolaev VO, Miragoli M, Sikkel MB, Paur H, Benard L, Hulot JS, Kohlbrenner E, Hajjar RJ, Peters NS, Korchev YE, Macleod KT, Harding SE, Gorelik J. Plasticity of surface structures and beta(2)-adrenergic receptor localization in failing ventricular cardiomyocytes during recovery from heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5(3):357–365. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.111.964692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Xie YP, Chen B, Sanders P, Guo A, Li Y, Zimmerman K, Wang LC, Weiss RM, Grumbach IM, Anderson ME, Song LS. Sildenafil prevents and reverses transverse-tubule remodeling and Ca(2+) handling dysfunction in right ventricle failure induced by pulmonary artery hypertension. Hypertension. 2012;59(2):355–362. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.180968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Navaratnarajah M, Ibrahim M, Siedlecka U, van Doorn C, Shah A, Gandhi A, Dias P, Sarathchandra P, Yacoub MH, Terracciano CM. Influence of ivabradine on reverse remodeling during mechanical unloading. Cardiovasc Res. 2012 doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kemi OJ, Hoydal MA, Macquaide N, Haram PM, Koch LG, Britton SL, Ellingsen O, Smith GL, Wisloff U. The effect of exercise training on transverse tubules in normal, remodeled, and reverse remodeled hearts. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226(9):2235–2243. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.van Oort RJ, Garbino A, Wang W, Dixit SS, Landstrom AP, Gaur N, De Almeida AC, Skapura DG, Rudy Y, Burns AR, Ackerman MJ, Wehrens XH. Disrupted junctional membrane complexes and hyperactive ryanodine receptors after acute junctophilin knockdown in mice. Circulation. 2011;123(9):979–988. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.006437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ibrahim M, Siedlecka U, Buyandelger B, Harada M, Rao C, Moshkov A, Bhargava A, Schneider M, Yacoub MH, Gorelik J, Knoll R, Terracciano CM. A critical role for Telethonin in regulating t-tubule structure and function in the mammalian heart. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22(2):372–383. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Minamisawa S, Oshikawa J, Takeshima H, Hoshijima M, Wang Y, Chien KR, Ishikawa Y, Matsuoka R. Junctophilin type 2 is associated with caveolin-3 and is down-regulated in the hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathies. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;325(3):852–856. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.10.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Xu M, Zhou P, Xu SM, Liu Y, Feng X, Bai SH, Bai Y, Hao XM, Han Q, Zhang Y, Wang SQ. Intermolecular failure of L-type Ca2+ channel and ryanodine receptor signaling in hypertrophy. PLoS Biol. 2007;5(2):e21. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Landstrom AP, Weisleder N, Batalden KB, Bos JM, Tester DJ, Ommen SR, Wehrens XH, Claycomb WC, Ko JK, Hwang M, Pan Z, Ma J, Ackerman MJ. Mutations in JPH2-encoded junctophilin-2 associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in humans. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;42(6):1026–1035. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Hayashi T, Arimura T, Itoh-Satoh M, Ueda K, Hohda S, Inagaki N, Takahashi M, Hori H, Yasunami M, Nishi H, Koga Y, Nakamura H, Matsuzaki M, Choi BY, Bae SW, You CW, Han KH, Park JE, Knoll R, Hoshijima M, Chien KR, Kimura A. Tcap gene mutations in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44(11):2192–2201. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.08.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Murphy RM, Dutka TL, Horvath D, Bell JR, Delbridge LM, Lamb GD. Ca2+-dependent proteolysis of junctophilin-1 and junctophilin-2 in skeletal and cardiac muscle. J Physiol. 2013;591(Pt 3):719–729. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.243279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Soeller C, Cannell MB. Examination of the transverse tubular system in living cardiac rat myocytes by 2-photon microscopy and digital image-processing techniques. Circ Res. 1999;84(3):266–275. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.3.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Franzini-Armstrong C, Protasi F, Ramesh V. Shape, size, and distribution of Ca(2+) release units and couplons in skeletal and cardiac muscles. Biophys J. 1999;77(3):1528–1539. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77000-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ohler A, Weisser-Thomas J, Piacentino V, Houser SR, Tomaselli GF, O’Rourke B. Two-photon laser scanning microscopy of the transverse-axial tubule system in ventricular cardiomyocytes from failing and non-failing human hearts. Cardiol Res Pract. 2009;2009:802373. doi: 10.4061/2009/802373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Wakili R, Yeh YH, YanQi X, Greiser M, Chartier D, Nishida K, Maguy A, Villeneuve LR, Boknik P, Voigt N, Krysiak J, Kaab S, Ravens U, Linke WA, Stienen GJ, Shi Y, Tardif JC, Schotten U, Dobrev D, Nattel S. Multiple potential molecular contributors to atrial hypocontractility caused by atrial tachycardia remodeling in dogs. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2010;3(5):530–541. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.109.933036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]